Abstract

The increasing demand for palm oil has drastic effects on the ecosystem, as its production is not sustainable. To that end, developing a sustainable alternative to fatty acids and oils is urgent and of utmost interest. Oils produced by oleaginous yeasts present a promising solution, particularly because the fatty acid profile of the oil produced by these yeasts is comparable to that of plant-based oils and fats. The fatty acid composition of the oil determines its physiological properties, thereby determining its potential applications. Accordingly, the production of microbial oil with an optimal composition profile for a specific application is of great importance. In this study, we evaluated the variation that occurred in fatty acid composition due to different cultivation parameters (temperature, C/N ratio, carbon, and nitrogen sources) and applied genetic modifications to improve the lipid accumulation of Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus and Yarrowia lipolytica. We showed that specific fatty acid profiles associated with a particular application can be obtained by carefully selecting the microorganism and cultivation conditions.

1. Introduction

The oils obtained from crops, especially palm oil, have been used as an inexpensive source for many useful components (like replacement of animal fats). It functions as a natural preservative in processed foods, is used as the foaming agent in shampoos and soaps, and is used as a raw material for biofuels [1]. In the last two decades, the production of palm oil went up 241% and represented 37% of the global vegetable oil production in 2020 [2]. However, using these feedstocks is not ideal in the long term, as their production has severe consequences for biodiversity and competes with other crops for land availability.

This impacts the food supply, and hence, its sustainability is a major challenge due to the food crisis worldwide [3]. Furthermore, palm tree plantations are rapidly replacing the original tropical forests and other original and traditional vegetation across numerous countries in Asia, South America, and Africa [4]. This is having a detrimental impact on the local ecosystem, as deforestation and climate change [5,6].

Despite the implementation of various responsible actions, including the opposition to deforestation driven by the RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil), the utilization of palm oil remains a topic of considerable contention [7]. The use of palm oil (and other tropical oils) is growing annually by 4%, which cannot be provided by RSPO (without deforestation). Based on the Impact Report 2024 published by RSPO, only 8.1% of palm oil production has been RSPO-Certified [8]. To that end, implementing a sustainable alternative to fatty acids and oils derived from plant-based oils is urgent and of utmost interest. Oleaginous yeasts have strong potential to produce sustainable alternatives to oils derived from plants due to their fast growth, high lipid content, and volumetric productivity [9]. Microbial oils produced by these oleaginous yeasts have been gaining significant attention as third-generation biodiesel feedstocks [10]. The first-generation biodiesel is produced from edible vegetable oils, such as soybean oil, rapeseed oil, and sunflower oil. The dilemma over the food vs. fuel and increasing price of edible oils has encouraged the development of second-generation biodiesel from non-edible plant oils such as jatropha, jojoba, and waste oils (cooking grease and animal fats) [11,12]. Microbial oils present a promising third-generation route as they can be produced by utilizing inexpensive side streams, such as whey permeate, crude glycerol from bioethanol production [13,14,15].

Additionally, microbial oil is a source for healthy oils/fatty acids such as PUFAs (polyunsaturated fatty acids). These yeasts can store lipids (primarily as TAGs) ranging from 20% to 80% of their cell mass under carefully selected culture conditions [16]. Under nitrogen limitation, fatty acid composition comprises myristic (C14:0, 0.3–34%), palmitic (C16:0, 3–37%), palmitoleic (C16:1, 0.4–9%), stearic (C18:0, 2–66%), oleic (C18:1, 36–57%), linoleic (C18:2, 2.1–24%), and linolenic (C18:3, 1–3%) acids [17]. Their versatile composition facilitates the use of oils in animal feed, food additives and ingredients, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and the production of biofuels, as they have a composition comparable to that of vegetable oils [18,19,20].

Over the last decade, research on yeast lipid technology has accelerated with a major interest in oleaginous yeast species, Yarrowia lipolytica, and Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus, as well as cultivation parameters to boost lipid accumulation, low-cost substrates, fatty acid composition, and cultivation modes to accelerate the industrial implementation of microbial oils [1,21].

Y. lipolytica is considered as a model organism for lipid production [22]. It is non-pathogenic and is regarded as food-grade yeast; thus, its oil can also be used for food-related applications [23,24]. Y. lipolytica strains present tolerance to low (19–25 °C) and high temperatures (33–35 °C) [25,26]. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, it produces lipids consisting of 15% C16:0, 13% C18:0, 51% C18:1, and 21% C18:2, which is comparable to the composition of plant-based oils [27]. Y. lipolytica can grow and produce lipids on hydrophilic (glucose, glycerol, crude glycerol) and hydrophobic substrates (waste oils, fatty acids, alkanes) [28,29,30,31]. It can produce significant quantities of SCO (up to ~70% w/w) through the ex novo conversion pathway using hydrophobic carbon sources such as fatty acids and alkane [32,33]. While some researchers can access larger yeast collections, which allow screening of many wild strains, only a limited number of wild-type strains have been observed to accumulate over 20% (w/w) lipids through the de novo pathway when cultured on glucose or similar carbon sources [34]. Generally, de novo production of lipids with Y. lipolytica does not compare favorably with the other key strains, despite some exceptions being reported. Nevertheless, its genetic accessibility renders Y. lipolytica an industrially relevant microorganism that can produce a variety of valuable metabolites not limited to fatty acids but also including fatty alcohols [35], unusual fatty acids such as long-chain PUFAs [35], citric acid [36], β-carotene [37], and erythritol [38].

C. oleaginosus (also known as Apiotrichum curvatum, Cryptococcus curvatus, Trichosporon cutaneum, Trichosporon oleaginosus, and Cutaneotrichosporon curvatum) is characterized for its high lipid accumulation. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, the produced fatty acid composition has been reported to be 25% C16:0, 10% C18:0, 57% C18:1, and 7% C18:2 by C. oleaginosus, which represents a similar composition to palm oil [39]. C. oleaginosus is able to grow and accumulate significant amounts of lipids on a wide range of carbon sources, such as xylose, glucose, galactose, glycerol, maltose, and lactose, as well as volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and fatty acids [40,41,42]. Therefore, in this work, we have focused on the aspects that affect the lipid profile of Y. lipolytica and C. oleaginosus.

In addition to the adjustment of cultivation parameters, metabolic engineering has been applied to boost lipid accumulation both for Y. lipolytica and C. oleaginosus [43,44,45,46,47]. While the overexpression of ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) and acetyl-coA carboxylase (ACC) improved lipid accumulation in C. oleaginous by up to 37%, a limited increase in lipid content (by up to 16%) was observed in Y. lipolytica (Table 1) [43,44]. When ACL, ACC, and threonine synthase (TS) were overexpressed simultaneously in C. oleaginosus, and a two-stage fermentation approach was applied, almost the theoretical maximum lipid yield on glycerol (~0.30 g/g) was achieved [48]. On the other hand, for Y. lipolytica, the most effective genetic engineering strategy among the tested targets was the overexpression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 (DGA1). These transformants represented an increase in lipid content by up to 200% (Table 1). Bracharz et al. (2017) reported that DGA overexpression did not increase the lipid content in C. oleaginosus, in contrast to Y. lipolytica [47]. These findings show that reactions catalyzing the late stage of TAG formation in Y. lipolytica, pulling free fatty acids into lipid bodies, are probably the rate-limiting steps of lipid accumulation, while the initial steps of fatty acid synthesis are limited to achieving a higher content of lipid accumulation with C. oleaginosus. In addition to the rate-limiting steps in the lipid biosynthesis pathway, the bottlenecks hinder the intermediate metabolite availability due to citrate secretion to the extracellular environment, and the β-oxidation pathways degrading fatty acids for Y. lipolyica were considered [43]. Blocking citrate exporters appears as a commentary strategy to disrupt the β-oxidation pathway (Table 1).

Table 1.

The lipid content and biomass concentration obtained by wild-type and mutant C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica strains. The C/N ratio represents the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of the medium. All experiments were performed by using glycerol as the carbon source and urea as the nitrogen source. ACL: ATP-citrate lyase, ACC: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, TS: Threonine synthase, HMGS: hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, MFE1: multifunctional enzyme in β-oxidation pathway, CEX1: citrate exporter protein.

The fatty acid composition defines the physiological properties of the oil, thereby determining its potential applications. For instance, a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids contributes to the oxidative stability of the oil, the ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids affects the melting point, and a higher content of MUFAs improves the thermal stability of the oil [17,50,51]. The microbial lipids produced by C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica predominantly comprise C16 to C18 fatty acids. These fatty acids, particularly oleic acid (C18:1), render this an appealing raw material to produce biodiesel [50,52]. Furthermore, oleic acid (C18:1) rich oils have been identified as superior feedstocks for chemical modification, facilitating the production of surfactants, plasticizers, and asphalt additives [51]. Saturated fatty acids such as C18:0 and C16:0-rich oils have been used in cleaning and personal care products [53,54]. For this reason, the production of microbial oil with an optimal compositional profile for a specific application is a critical aspect for ensuring its effective utilization.

In this study, we systematically investigated the variation in the fatty acid composition of the produced oil by C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica mutants at different cultivation parameters. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Covariance Simultaneous Component Analysis (COVSCA) were used to illustrate and interpret how correlation patterns vary across conditions (cultivation temperature, genetic interventions) and yeast species [55,56]. Following a thorough evaluation of the outcomes, the conditions were reported to obtain a specific fatty acid composition of the oil produced by C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Experimental Conditions in the Literature

Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus ATCC 20509 isolated from a dairy plant, Yarrowia lipolytica CBS 8108 isolated from jet fuel, and transformants listed in Table 2 were used for cultivation. Wild-type and built C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica transformants were cultivated in minimal media consisting of glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No. G7757) as the carbon source, and urea (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No. G5378) as the nitrogen source. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N, g/g) of the medium was set to 30, 120, 140, 175, 200, 240, or 300 by increasing the concentration of the carbon source [42,43,44,49]. The reported C/N values represent the mass ratio of carbon to nitrogen in the cultivation medium, calculated as grams of carbon in glycerol added divided by grams of nitrogen in urea added to the medium. Five-hundred-milliliter Erlenmeyer flasks were used with a one-hundred-milliliter working volume. Cultures were incubated at 15 °C, 30 °C, or 35 °C at 250 rpm for 96 h (C. oleaginosus strains) and 15 °C, 30 °C, or 35 °C, at 250 rpm for 120 h (Y. lipolytica strains) in a shaking incubator (New Brunswick Scientific Co., Inc., Edison, NJ, USA, I2500). Cells were harvested at the end of incubation and centrifuged at 1780× g, 4 °C for 15 min. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Table 2.

List of oleaginous yeast strains used in cultivation experiments. ACL: ATP-citrate lyase, ACC: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, TS: Threonine synthase, HMGS: hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, MFE1: multifunctional enzyme in β-oxidation pathway, CEX1: citrate exporter protein.

2.2. Fatty Acid Composition Data

The fatty acid composition of yeast microbial oil data was determined and acquired in the previous studies [42,43,44,49]. The total fatty acids were determined quantitatively with a gas chromatograph (GC), 7830B GC systems (Aligent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a Supelco NukolTM 25,357 column (30 m × 530 µm × 1.0 µm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), with hydrogen as a carrier gas. Samples were initially prepared as described by Duman-Özdamar et al., 2022 [42]. Chloroform was evaporated under nitrogen gas, and lipids in the tubes were dissolved in hexane before GC analysis.

2.3. Statistical Methods

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [57,58] was carried out on the fatty acid profiles.

Covariance Simultaneous Component Analysis (COVSCA) [55] was performed to investigate the differences between the matrices of correlations obtained from the data matrix of C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica. For each microorganism, the full sets of strains were considered, 9 and 12 for C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica, respectively. For each strain, matrices with the correlations between fatty acid types (9 variables) were built, and differences were explored by fitting a COVSCA model considering 3 prototype matrices (rank 2).

2.4. Software and Data

The statistics function was prcomp within R version 4.0.2 [59,60]. The correlation biplots of the principal component scores, the loading vectors, and heatmaps were plotted through the R ggplot2 package [61].

Data used for PCA and COVSCA is available in ZENODO (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13958333, accessed on 17 December 2025), methods and code for COVSCA are available in GitLab (https://github.com/esaccenti/covsca, accessed on 17 December 2025).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fatty Acid Profile of Oleaginous Yeasts

The fatty acid composition of the microbial oils produced by C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica WT and mutants grown in minimal media with various C/N ratios at 30 °C was retrieved from our previous studies [42,43,44,49].

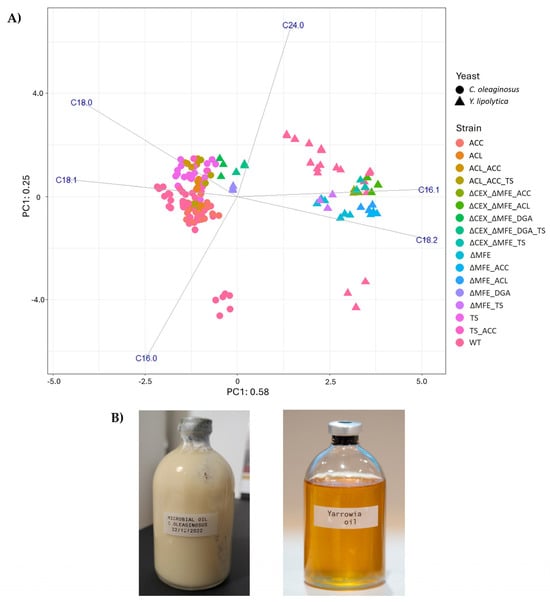

Oil from both oleaginous yeasts contained similar types of fatty acids, including >1% C16:0, C16:1, C18:0, C18:1, C18:2, and C24:0; however, they also exhibited differences in the ratio of fatty acids (Figure 1A). Microbial oil produced by C. oleaginosus contains a higher content of saturated fatty acids (35–44%, w/w) compared to the oil produced by Y. lipolytica (23–34%, w/w) when grown at 30 °C (Figure 1A, ZENODO). The wild-type Y. lipolytica produced a higher content of PUFAs, with 20% (w/w) linoleic acid (C18:2), compared to the C. oleaginosus oil, which contains approximately 8% (w/w) C18:2 (ZENODO). On the other hand, the C. oleaginosus oil contains a higher content of MUFAs, including 50% (w/w) oleic acid (C18:1) and 1% (w/w) palmitoleic acid (C16:1), whereas the Y. lipolytica oil comprises 36% (w/w) C18:1 and 9% (w/w) C16:1. Among the tested Y. lipolytica mutants, we observed that ΔMFE_ΔCEX_DGA and ΔMFE_ΔCEX_DGA_TS presented a similar fatty acid composition to the oil produced by TS_ACC mutant of C. oleaginosus.

Figure 1.

(A) PCA on the fatty acid profile of the oil obtained from C. oleaginous and Y. lipolytica. In addition to the WT, different strains were included in the analysis. Variance explained by each component is given in the labels. (B) Microbial oil obtained from C. oleaginosus (semi-solid fat at room temperature) and Y. lipolytica (liquid oil at room temperature).

The observed variation in the ratio of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids resulted in oil with different melting points at room temperature. The extracted oil from C. oleaginosus was semi-solid at room temperature (fat), like palm oil (Figure 1B) [1]. Conversely, Y. lipolytica produced lipids that were liquid at room temperature (oil) (Figure 1B). The Y. lipolytica oil was obtained from the ΔMFE_ΔCEX_DGA_TS strain, and the C. oleaginosus oil from the wild-type strain. In both cases, lipids were recovered from oven-dried biomass (≥50%, w/w intracellular oil) by mechanical cell disruption. This extraction procedure is consistently applied at Wageningen Food & Biobased Research and ensures comparable recovery across samples (unpublished internal protocol, 2025).

3.2. (Dis)similarities of the Fatty Acid Composition Produced by Different Strains

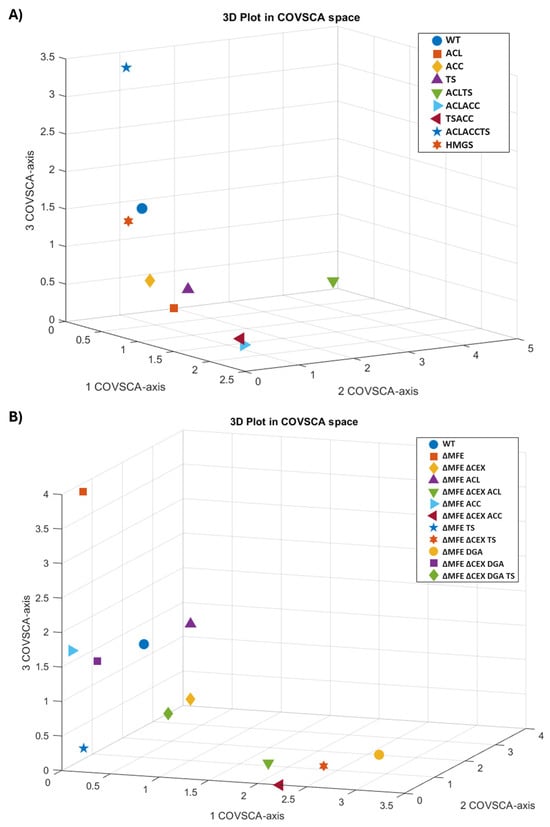

In addition to the oleaginous yeast-specific differences in the fatty acid profile, some of the applied genetic interventions and manipulated environmental factors steered the fatty acid composition. To further investigate the variation in fatty acid profiles among strains of oleaginous yeasts and to facilitate the appropriate strain selection, Covariance Simultaneous Component Analysis (COVSCA) was used to model the correlation matrices obtained for the lipid data of C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica were investigated.

The 3D plot in the COVSCA space (Figure 2) depicts the first three components of the model. Each point represents a strain. The axes (component space) show the dimensions where covariance is maximized, indicating that the closer the two points are, the more similar they are in terms of their correlation structure. For C. oleaginosus, wild-type and HMGS are clustered together, indicating the similarity in the fatty acid composition of the oil produced by these strains (Figure 2A). Although the fatty acid profiles of ACL, ACC, and TS were similar, the double and triple mutants ACL_TS and ACL_ACC_TS strains exhibited distinct fatty acid compositions compared to other strains. On the other hand, the fatty acid composition of Y. lipolytica strains exhibited greater divergence except for ΔMFE_ΔCEX_ACL, ΔMFE_ΔCEX_ACC, and ΔMFE_ΔCEX_TS, which represented similarities (Figure 2B). Furthermore, ΔMFE_ΔCEX_DGA_TS showed strong variation along all axes, indicating that combining multiple genetic modifications resulted in a significant alteration in the fatty acid profile. In all, COVSCA models and plots demonstrate the possibility of creating a pallet of strains expressing a wide range of fatty acid profiles.

Figure 2.

Plots in COVSCA space representing the (dis)similarities of the fatty acid composition obtained by incubating various strains of (A) C. oleaginosus and (B) Y. lipolytica at different temperatures and C/N ratio medium. COVSCA models of C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica strains had 75.10% and 57.36% goodness of fit, respectively.

3.3. Altered Cultivation Parameters and Genetic Modifications Steered Fatty Acid Composition

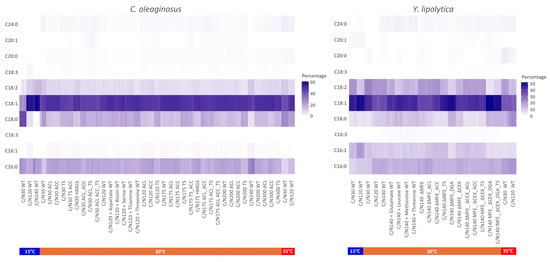

A comprehensive comparison of all tested conditions (temperature, C/N ratio, and medium supplements) and applied genetic modifications was conducted for each fatty acid component (Figure 3). We observed that varying the cultivation temperature steered the fatty acid composition (Figure 3). For both oleaginous yeasts, when the growth temperature was increased to 35 °C, they produced a higher content of saturated fatty acids (C18:0, C20:0, C24:0). Temperature has been reported as a critical cultivation parameter for growth, lipid synthesis, and fatty composition and degree of saturation of the accumulated triacyglycerides [62,63]. For oleaginous yeasts, Rhodosporidium toruloides [64], Candida lipolytica [65], and Rhodotorula glutinis [66], previous works reported that temperature affects the activity of fatty acid desaturase enzymes; therefore, the fatty acid composition of the produced microbial oil is altered. Ferrante et al. demonstrated that the activity of Δ12-desaturase in C. lipolytica, which is the enzyme catalyzing the transformation of oleoyl-CoA to linoleoyl-CoA, increased at 10 °C compared to 25 °C [65]. The decreased temperature led to an increased level of C18:2 fatty acid.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of the fatty acid profile of C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica. For each experimental condition, triplicates were used in the plots. The temperatures are included as bars below the sample names represented by colors.

Moreover, an increased C18:0 fraction in total fatty acid was observed when TS was overexpressed in C. oleaginosus (TS, ACL_TS, ACC_TS, ACL_ACC_TS) compared to other strains (Figure 3). On the other hand, overexpression of TS in Y. lipolytica led to a reduction in the C18:0 fraction. Enzyme inhibitors such as specific fatty acids can be added to the broth to alter the lipid fatty acid profile [34,67]. This strategy was considered when attempting to increase the stearic acid (C18:0) content for the production of a cocoa butter equivalent (CBE) with C. oleaginosus, but enzyme inhibitors increase the process costs, and some are toxic [68,69]. To counter the increased cocoa butter prices, in addition to CBE, cocoa butter replacers (CBR) are developed as alternatives. CBRs are produced by hardening the oils derived from sunflower or rapeseed via partial hydrogenation and therefore comprise a high amount of trans-fat [70]. In this regard, by altering the temperature and selecting the appropriate strain, the oil replacement for tropical (hard) fats, such as cocoa butter, palm, and coconut fat, can be obtained via C. oleaginosus.

Decreasing the temperature to 15 °C led to the production of a higher content of unsaturated fatty acids (C18:1, C18:2). Gao et al. (2020) tested 28 °C and 38 °C for Y. lipolytica and reported a similar shift in the fatty acid composition of the produced oil [15]. Among all tested strains and cultivation conditions, the highest C18:1 composition (~60%, w/w) was obtained with wild-type C. oleaginosus incubated at 15 °C in C/N 120 medium (ZENODO). For Y. lipolytica, C18:1 composition reached ~50% (w/w) when ΔMFE_DGA, ΔMFE_ΔCEX_DGA, and ΔMFE_ΔCEX_DGA_TS were cultivated at 30 °C in C/N140 medium, and the wild-type was incubated at 15 °C (ZENODO). High relative oleic acid concentrations (~50% (w/w)) were observed with oleaginous yeasts that accumulate more than 50% lipid content. Tai et al. (2013) reported higher C18:1 composition when DGA1 was overexpressed and related this situation to rapid lipid production in that strain [71].

Furthermore, the supplementation of amino acids to the medium with wild-type strains did not result in a change in the ratio of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. However, this led to a shift in the profile of PUFAs towards MUFAs, with a notable increase in the fraction of C18:1 (Figure 3). Tsakraklides et al. (2018) obtained lipid accumulation with a C18:1 content exceeding 90% in Y. lipolytica by replacing the native ∆9 fatty acid desaturase and glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase with heterologous versions [72,73]. Additionally, the Δ12 fatty acid desaturase was deleted, and a fatty acid elongase was expressed. The combination of these approaches can be beneficial in increasing the content of oleic acid in both oleaginous yeasts. Furthermore, by decreasing the temperature, the ratio of unsaturated fatty acids can be increased in C. oleaginosus, thereby potentially enabling the production of oil with a similar composition to that of Y. lipolytica. However, it should be noted that reduced temperature may have an impact on the overall yield of microbial oil production [42].

In this work, we investigated the fatty acid composition of microbial oil by using glycerol as a carbon source and urea as a nitrogen source. Awad et al. (2019) reported that using different carbon and nitrogen sources influenced the saturation level of the fatty acids produced by C. oleaginosus [41]. The supplementation of ammonia in the media resulted in a notable shift in the fatty acid profile of the produced oil compared to the profiles resulting from the supplementation of urea, yeast extract, and peptone (organic nitrogen sources). Using ammonia increased the proportion of C18:2 and decreased the proportion of C16:0 and C18:0. Additionally, Awad et al. (2019) observed comparable fatty acid profiles when glucose, mannose, maltose, and lactose were utilized as carbon sources, similar to the findings observed with glycerol [41]. Conversely, sorbitol and arabinose were reduced to C18:0 and C18:1, with an increase in C18:2. For Y. lipolytica, dextrose was found to enhance the content of saturated fatty acids (C16:0 and C18:0) [74]. This represents that specific fatty acid profiles associated with the desired product applications can be boosted by carefully selecting media components.

3.4. Potential Applications of Yeast Oil

In earlier sections, it was demonstrated that the fatty acid composition and degree of saturation of these fatty acids in microbial oil are altered by the type of oleaginous yeast, applied genetic modifications, cultivation temperature, and medium components or supplements. This variation enables the utilization of the produced microbial oil in a variety of applications, such as in confectionery and personal care products and as a feedstock for biodiesel production.

Oils containing high percentages of saturated fatty acids (C16:0 and C18:0) have higher melting points [75]. For instance, C. oleaginosus oil from the wild type incubated at 35 °C contained more than 45% of saturated fatty acids, and it was identified as semi-solid at room temperature, whereas oil from wild-type Y. lipolytica incubated at 30 °C contained 31% of saturated fatty acids and it was liquid at room temperature (Figure 2B). Moreover, the increased ratio of saturated fatty acids improves oxidative stability compared with oils dominated by MUFAs or PUFAs [75]. These properties make yeast oil suitable for confectionery fats used in bars, fillings, and toffees. In the case of biscuit production, the solid fat content of the utilized oil significantly influences the handling properties of the dough, resulting in a firmer or harder dough consistency [76]. Additionally, it affects the textural characteristics of the final product, including the biscuit’s breaking force. As Manley (2011) has demonstrated, dough composed of semi-solid fat yields superior structures during the baking process when compared with dough made of liquid oil [77]. In our dataset, the fatty-acid composition produced by C. oleaginosus strains, cultivated under elevated temperatures (30–35 °C) and in TS-overexpressing mutants, showed the highest saturated fractions and therefore represented the most promising alternatives for confectionery products.

Oils and fats used in personal care formulations such as balms and moisturizers function as emollients, structuring agents, and sensory modifiers [78,79]. Saturated-fatty-acid-rich lipids provide firmness and controlled melting behavior for sticks and balms. On the other hand, MUFA-rich oils enhance spreadability and give a non-greasy sensory profile in lotions [79,80]. The wild-type C. oleaginosus cultivated at 15 °C produced oil containing approximately 60% oleic acid (C18:1), while DGA-overexpressing Y. lipolytica transformants yielded oil with about 50% C18:1, both would be suitable for the formulation of light, fast-absorbing emulsions. Besides sensory characteristics, the ratio of linoleic to oleic acid (C18:2:C18:1) is a key determinant in tailoring formulations for different skin types. A ratio of C18:2:C18:1 approximately 1:1.8 is associated with normal, healthy skin, whereas a higher oleic proportion (~1:4.7) has been recommended for dry skin [80]. Accordingly, the oil produced by Y. lipolytica transformants overexpressing ACL could be suitable for formulations targeting normal skin, while the triple mutant of C. oleaginosus could provide oil compositions more appropriate for products designed for dry skin.

The suitable oil composition for biodiesel production was defined as MUFA-rich (dominant in C18:1) and low in PUFAs that balance fluidity and provide good oxidative stability and cold-weather performance [12]. Microbial oil produced by C. oleaginosus, C. gracilis (microalgae), and R. opacus (bacteria) is presented as an effective fuel to replace both petroleum diesel and biodiesel produced from plant oils [81,82]. A high C18:1 fraction was observed for the DGA-overexpressing strain of Y. lipolytica and wild-type C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica when they were cultivated at a lower temperature (15 °C).

Emerging technologies are highlighting the potential of microbial oils produced by genetically modified (GMO) yeasts as high-value ingredients for cosmetics, food, and feed applications, as well as biodiesel production [83,84,85]. As described in this work, engineered oleaginous yeasts achieved advanced oil titer and delivered specialty oils through the targeted alteration of the fatty acid profile. Even though this is currently a rapidly evolving field, regulatory frameworks governing GMO-derived compounds remain a major determinant of their industrial implementation. The approval process is strictly regulated in Europe with Regulation (EC) No. 1829/2003 on genetically modified food and feed compounds. After going through a strict evaluation, it is mandatory to label food products containing ingredients derived from GMOs. However, these products can still be used in non-food applications, including in cleaning products and personal care items, and as a feedstock for biodiesel production.

Microbial oils derived from wild-type microorganisms are considered as a novel food in Europe, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada [86]. In 2022, the European Commission granted authorization for the use of oil derived from Schizochytrium sp. as a novel functional food ingredient. In 2023, Y. lipolytica was approved by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) for use as a novel food ingredient for human consumption under the EU novel food regulation [87]. In addition to regulatory requirements, consumer perception also plays a pivotal role in determining market uptake. According to the report of the Eurobarometer, in 2005, approximately 73% of Europeans did not consider GMO-derived food ingredients to be safe for consumption. On the other hand, this ratio declined considerably to 59% in 2010, indicating a trend toward increasing acceptance.

4. Conclusions

The systematic evaluation of all tested conditions (temperature, C/N ratio, and medium supplements) and applied genetic modifications to improve the lipid accumulation of C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica revealed the variation that occurred in fatty acid composition. These findings suggest that combining optimized media composition and cultivation conditions with genetically engineered strains enables achieving unique combinations of both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids in significant quantities. The compositional variation in fatty acids corresponds with the requirements of diverse applications. Saturated-rich oils from C. oleaginosus are well suited to confectionery fats and solid personal-care formulations. MUFA-rich oils from C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica mutants grown at lower temperatures are attractive as feedstock for biodiesel production. PUFA-enriched Y. lipolytica oil is suitable for barrier-supporting formulations in personal care products. Overall, the ability to steer the fatty acid composition facilitates the utilization of microbial oil from C. oleaginosus and Y. lipolytica as a substitute ffor plant-based oils and fats for versatile industrial applications while still maintaining a high lipid content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.E.D.-Ö., J.H., V.A.P.M.d.S. and M.S.-D.; methodology, Z.E.D.-Ö., E.S. and M.S.-D.; formal analysis, Z.E.D.-Ö., E.S. and M.S.-D.; investigation, Z.E.D.-Ö., J.H. and M.S.-D.; data curation, Z.E.D.-Ö., E.S. and M.S.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.E.D.-Ö.; writing—review and editing, Z.E.D.-Ö., E.S., R.v.d.G., V.A.P.M.d.S., J.H. and M.S.-D.; visualization, Z.E.D.-Ö., E.S. and M.S.-D.; supervision, V.A.P.M.d.S., J.H. and M.S.-D.; project administration, V.A.P.M.d.S. and J.H.; funding acquisition, V.A.P.M.d.S., J.H. and M.S.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture through the “TKI-toeslag” project LWV19221 “Tailor-made microbial oils and fatty acids”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in ZENODO at https://zenodo.org/records/13958334 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Rosan van der Glas and Jeroen Hugenholtz were employed by the company NoPalm Ingredients BV. Author Vitor A. P. Martins dos Santos was employed by the company LifeGlimmer GmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| C/N | Carbon to nitrogen |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| COVSCA | Covariance Simultaneous Component Analysis |

References

- Han, K.; Willams, K.J.; Goldberg, A.C. Plant-Based Oils. In Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: Nutritional and Dietary Approaches; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; ISBN 978-92-5-138262-2.

- Shi, S.; Valle-Rodríguez, J.O.; Siewers, V.; Nielsen, J. Prospects for Microbial Biodiesel Production. Biotechnol. J. 2011, 6, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayompe, L.M.; Schaafsma, M.; Egoh, B.N. Towards Sustainable Palm Oil Production: The Positive and Negative Impacts on Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Ishak, M.Y.; Makmom, A.A. Impacts of and Adaptation to Climate Change on the Oil Palm in Malaysia: A Systematic Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54339–54361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snashall, G.B.; Poulos, H.M. Oreos versus Orangutans: The Need for Sustainability Transformations and Nonhierarchical Polycentric Governance in the Global Palm Oil Industry. Forests 2021, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzolla Gatti, R.; Liang, J.; Velichevskaya, A.; Zhou, M. Sustainable Palm Oil May Not Be so Sustainable. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil). Impact Report 2024; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Poontawee, R.; Lorliam, W.; Polburee, P.; Limtong, S. Oleaginous Yeasts: Biodiversity and Cultivation. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2023, 44, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y. Biodiesels from Microbial Oils: Opportunity and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soccol, C.R.; Dalmas Neto, C.J.; Soccol, V.T.; Sydney, E.B.; da Costa, E.S.F.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Vandenberghe, L.P.d.S. Pilot Scale Biodiesel Production from Microbial Oil of Rhodosporidium toruloides DEBB 5533 Using Sugarcane Juice: Performance in Diesel Engine and Preliminary Economic Study. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 223, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzi, S.; Garcia, I.L.; Lopez-Gimenez, F.J.; Luque de Castro, M.D.; Dorado, G.; Dorado, M.P. The Ideal Vegetable Oil-Based Biodiesel Composition: A Review of Social, Economical and Technical Implications. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 2325–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ykema, A.; Verbree, E.C.; Kater, M.M.; Smit, H. Optimization of Lipid Production in the Oleaginous Yeast Apiotrichum curvatum in Wheypermeate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1988, 29, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Trushenski, J.; Blackburn, J.W. Converting Crude Glycerol Derived from Yellow Grease to Lipids through Yeast Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7581–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Bao, W.; Cheng, S.; Zheng, L. Enhanced Lipid Production by Yarrowia lipolytica Cultured with Synthetic and Waste-Derived High-Content Volatile Fatty Acids under Alkaline Conditions. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, D.; van Biezen, N.; Martens, D.; Peters, L.; van de Zilver, E.; Jacobs-van Dreumel, N.; Wijffels, R.H.; Lokman, C. Selection of Oleaginous Yeasts for Fatty Acid Production. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharathiraja, B.; Sridharan, S.; Sowmya, V.; Yuvaraj, D.; Praveenkumar, R. Microbial Oil—A Plausible Alternate Resource for Food and Fuel Application. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 233, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, R.A.; Patel, D. Improvement in Shelf-Life and Safety of Perishable Foods by Plant Essential Oils and Smoke Antimicrobials. Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbois, A.P. Potential Applications of Antimicrobial Fatty Acids in Medicine, Agriculture and Other Industries. Recent Pat. Anti-Infect. Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustan, A.C.; Drevon, C.A. Fatty Acids: Structures and Properties. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, S.; He, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Z.; Li, Z. A Review of Lipid Accumulation by Oleaginous Yeasts: Culture Mode. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, S.; Zheng, L. Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica Culture with Synthetic and Food Waste-Derived Volatile Fatty Acids for Lipid Production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinjarde, S.S. Food-Related Applications of Yarrowia lipolytica. Food Chem 2014, 152, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Ju, Y.H.; Tsai, S.L. Enhanced Lipid Production in Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g by Over-Expressing Lro1 Gene under Two Different Promoters. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, L.T.; Alper, H.S. Production of α-Linolenic Acid in Yarrowia lipolytica Using Low-Temperature Fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 8809–8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Chevalot, I.; Komaitis, M.; Marc, I.; Aggelis, G. Single Cell Oil Production by Yarrowia lipolytica Growing on an Industrial Derivative of Animal Fat in Batch Cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 58, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Lipid Production by Yarrowia lipolytica Growing on Industrial Glycerol in a Single-Stage Continuous Culture. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 82, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Modeling Lipid Accumulation and Degradation in Yarrowia lipolytica Cultivated on Industrial Fats. Curr. Microbiol. 2003, 46, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, M.; Brar, S.K.; Blais, J.F. Lipid Production by Yarrowia lipolytica Grown on Biodiesel-Derived Crude Glycerol: Optimization of Growth Parameters and Their Effects on the Fermentation Efficiency. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 90547–90558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rywińska, A.; Juszczyk, P.; Wojtatowicz, M.; Robak, M.; Lazar, Z.; Tomaszewska, L.; Rymowicz, W. Glycerol as a Promising Substrate for Yarrowia lipolytica Biotechnological Applications. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 48, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporusso, A.; Capece, A.; De Bari, I. Oleaginous Yeasts as Cell Factories for the Sustainable Production of Microbial Lipids by the Valorization of Agri-Food Wastes. Fermentation 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.-F.; Teleky, B.-E.; Szabo, K.; Martău, A.-G.; Ştefănescu, B.-E.; Dulf, F.-V.; Vodnar, D.-C. Waste Cooking Oil and Crude Glycerol as Efficient Renewable Biomass for the Production of Platform Organic Chemicals through Oleophilic Yeast Strain of Yarrowia lipolytica. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Liu, N.; Eser, B.E.; Guo, Z.; Jensen, P.R.; Stephanopoulos, G. Synthesis of High-Titer Alka(e)Nes in Yarrowia lipolytica Is Enabled by a Discovered Mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeln, F.; Chuck, C.J. The History, State of the Art and Future Prospects for Oleaginous Yeast Research. Microb. Cell Fact. 2021, 20, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xiong, X.; Ghogare, R.; Wang, P.; Meng, Y.; Chen, S. Exploring Fatty Alcohol-Producing Capability of Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, L.; Grünberg, M.; Zehnsdorf, A.; Aurich, A.; Bley, T.; Strehlitz, B. Repeated Fed-Batch Fermentation Using Biosensor Online Control for Citric Acid Production by Yarrowia lipolytica. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 153, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, M.; Xin, F.; Zhang, W. Enhanced β-Carotene Production in Yarrowia lipolytica through the Metabolic and Fermentation Engineering. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 50, kuad009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirończuk, A.M.; Furgała, J.; Rakicka, M.; Rymowicz, W. Enhanced Production of Erythritol by Yarrowia lipolytica on Glycerol in Repeated Batch Cultures. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 41, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, N.; Reijnders, M.; Suarez-Diez, M.; Nijsse, B.; Springer, J.; Eggink, G.; Schaap, P.J. Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling Underscores the Potential of Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus ATCC 20509 as a Cell Factory for Biofuel Production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesters, P.A.E.P.; Huijberts, G.N.M.; Eggink, G. High-Cell-Density Cultivation of the Lipid Accumulating Yeast Cryptococcus curvatus Using Glycerol as a Carbon Source. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 45, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, D.; Bohnen, F.; Mehlmer, N.; Brueck, T. Multi-Factorial-Guided Media Optimization for Enhanced Biomass and Lipid Formation by the Oleaginous Yeast Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman-Özdamar, Z.E.; Martins dos Santos, V.A.P.; Hugenholtz, J.; Suarez-Diez, M. Tailoring and Optimizing Fatty Acid Production by Oleaginous Yeasts through the Systematic Exploration of Their Physiological Fitness. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman-Özdamar, Z.E.; Julsing, M.K.; Martins dos Santos, V.A.P.; Hugenholtz, J.; Suarez-Diez, M. Model-Driven Engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for Improved Microbial Oil Production. Microb. Biotechnol. 2025, 18, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman-Özdamar, Z.E.; Julsing, M.K.; Verbokkem, J.A.C.; Wolbert, E.; Martins dos Santos, V.A.P.; Hugenholtz, J.; Suarez-Diez, M. Model-Driven Engineering of Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus ATCC 20509 for Improved Microbial Oil Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 421, 132142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazeck, J.; Hill, A.; Liu, L.; Knight, R.; Miller, J.; Pan, A.; Otoupal, P.; Alper, H.S. Harnessing Yarrowia lipolytica Lipogenesis to Create a Platform for Lipid and Biofuel Production. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellner, N.I.; Rerop, Z.S.; Mehlmer, N.; Masri, M.; Ringel, M.; Brück, T.B. Expanding the Genetic Toolbox for Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus Employing Newly Identified Promoters and a Novel Antibiotic Resistance Marker. BMC Biotechnol. 2023, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracharz, F.; Beukhout, T.; Mehlmer, N.; Brück, T. Opportunities and Challenges in the Development of Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus ATCC 20509 as a New Cell Factory for Custom Tailored Microbial Oils. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Lipids of Oleaginous Yeasts. Part I: Biochemistry of Single Cell Oil Production. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman-Özdamar, Z.E.; Veloo, R.M.; Tsepani, E.; Julsing, M.K.; Martins dos Santos, V.A.P.; Hugenholtz, J.; Suarez-Diez, M. Combining Metabolic Engineering and Fermentation Optimization to Achieve Cost-Effective Oil Production by Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitepu, I.R.; Garay, L.A.; Sestric, R.; Levin, D.; Block, D.E.; German, J.B.; Boundy-Mills, K.L. Oleaginous Yeasts for Biodiesel: Current and Future Trends in Biology and Production. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1336–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggs, R. Industrial Uses of High-Oleic Oils. In High Oleic Oils; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.U.; Park, J.M. Biodiesel Production by Various Oleaginous Microorganisms from Organic Wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 256, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Maiti, M.K. Lipid Production by Oleaginous Yeasts. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cerone, M.; Smith, T.K. A Brief Journey into the History of and Future Sources and Uses of Fatty Acids. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 570401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilde, A.K.; Timmerman, M.E.; Saccenti, E.; Jansen, J.J.; Hoefsloot, H.C.J. Covariances Simultaneous Component Analysis: A New Method within a Framework for Modeling Covariances. J. Chemom. 2015, 29, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccenti, E.; Camacho, J. Multivariate Exploratory Data Analysis Using Component Models. In Comprehensive Foodomics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 241–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a Complex of Statistical Variables into Principal Components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. LIII. On Lines and Planes of Closest Fit to Systems of Points in Space. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R Software, Version 4.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020.

- Martins, T.G. Computing and Visualizing PCA in R. R-bloggers. 2013. Available online: https://www.r-bloggers.com/2013/11/computing-and-visualizing-pca-in-r/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donot, F.; Fontana, A.; Baccou, J.C.; Strub, C.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Single Cell Oils (SCOs) from Oleaginous Yeasts and Moulds: Production and Genetics. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 68, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, S.; Triantaphyllidou, I.-E.; Aggeli, D.; Elazzazy, A.M.; Baeshen, M.N.; Aggelis, G. Microbial Oils as Food Additives: Recent Approaches for Improving Microbial Oil Production and Its Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Content. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 37, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Du, W.; Liu, D. Microbial Conversion of Biodiesel Byproduct Glycerol to Triacylglycerols by Oleaginous Yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides and the Individual Effect of Some Impurities on Lipid Production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 65, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, G.; Ohno, Y.; Kates, M. Influence of Temperature and Growth Phase on Desaturase Activity of the Mesophilic Yeast Candida lipolytica. Can. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1983, 61, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, L.-M.; Perlot, P.; Goma, G.; Pareilleux, A. Kinetics of Growth and Fatty Acid Production of Rhodotorula glutinis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1992, 37, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreton, R.S. Modification of Fatty Acid Composition of Lipid Accumulating Yeasts with Cyclopropene Fatty Acid Desaturase Inhibitors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1985, 22, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratledge, C. Single Cell Oils for the 21st Century. In Single Cell Oils; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, D.J.; Ratledge, C. Industrial Applications of Single Cell Oils; American Oil Chemists’ Society: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 093531539X. [Google Scholar]

- Hassim, N.A.M. Usage of palm oil, palm kernel oil and their fractions as confectionery fats. J. Oil Palm Res. 2017, 29, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, M.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering the Push and Pull of Lipid Biosynthesis in Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for Biofuel Production. Metab. Eng. 2013, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakraklides, V.; Brevnova, E.E.; Friedlander, J.; Kamineni, A.; Shaw, A.J. Oleic Acid Production in Yeast. U.S. Patent Application No. 15/534,818, 28 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakraklides, V.; Kamineni, A.; Consiglio, A.L.; MacEwen, K.; Friedlander, J.; Blitzblau, H.G.; Hamilton, M.A.; Crabtree, D.V.; Su, A.; Afshar, J.; et al. High-Oleate Yeast Oil without Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, R.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, S.; Men, Y.; Zheng, L. Approaches to Improve the Lipid Synthesis of Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoh, C.C.; Min, D.B. Food Lipids: Chemistry, Nutrition, Biotechnology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780203908815. [Google Scholar]

- Mamat, H.; Hill, S.E. Effect of Fat Types on the Structural and Textural Properties of Dough and Semi-Sweet Biscuit. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, D.; Vir, S. Manley’s Technology of Biscuits, Crackers and Cookies; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2011; ISBN 9780857093646. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rivero, C.; López-Gómez, J.P. Unlocking the Potential of Fermentation in Cosmetics: A Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.; Siamidi, A.; Varvaresou, A.; Vlachou, M. Skin Care Formulations and Lipid Carriers as Skin Moisturizing Agents. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mank, V.; Polonska, T. Use of Natural Oils as Bioactive Ingredients of Cosmetic Products. Ukr. Food J. 2016, 5, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiru, M.; Sankh, S.; Rangaswamy, V. Process for Biodiesel Production from Cryptococcus curvatus. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 10436–10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlen, B.D.; Morgan, M.R.; McCurdy, A.T.; Willis, R.M.; Morgan, M.D.; Dye, D.J.; Bugbee, B.; Wood, B.D.; Seefeldt, L.C. Biodiesel from Microalgae, Yeast, and Bacteria: Engine Performance and Exhaust Emissions. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Bautista-Hérnandez, I.; Gomez-García, R.; Costa, E.M.; Machado, M. Precision Fermentation as a Tool for Sustainable Cosmetic Ingredient Production. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes da Silva, T.; Fontes, A.; Reis, A.; Siva, C.; Gírio, F. Oleaginous Yeast Biorefinery: Feedstocks, Processes, Techniques, Bioproducts. Fermentation 2023, 9, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Nguyen, T.-V.-L.; Tran, T.T.V.; Khatri, Y.; Chandrapala, J.; Truong, T. Single Cell Oils from Oleaginous Yeasts and Metabolic Engineering for Potent Cultivated Lipids: A Review with Food Application Perspectives. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazani, S.M.; Marangoni, A.G. Microbial Lipids for Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; Pentieva, K.; et al. Safety of an Extension of Use of Yarrowia lipolytica Yeast Biomass as a Novel Food Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e8416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.