Abstract

Lactic acid bacteria can colonize the gut, thereby regulating the gut microbiota and improving intestinal health. The study aimed to screen the suitable strains for Suanzhou fermentation and investigate their roles in the chicken gut in vivo. A total of 70 strains of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Suanzhou were characterized to determine their biofilm formation abilities. The strains with high-yielding biofilms were further characterized for their optimum growth temperature and pH, as well as antibacterial effects. Based on the results of biofilm formation, temperature and pH tolerance, and antibacterial effect experiments, two strains of h8-c and p15-c (Lactiplantibacillus pentosus) with high-yielding biofilms and better antibacterial effects were selected. By establishing a chick Lactobacillus feeding model and using high-throughput techniques to analyze the structure and diversity of the gut microbiota, we investigated changes in the diversity of gut bacteria, fungi, and archaea during and for three weeks after feeding with h8-c and p15-c. The results indicate that h8-c and p15-c may promote the intestinal colonization of lactobacilli, thereby balancing the gut microbiota and enhancing intestinal health in chicks. Furthermore, these strains provide excellent candidates for the industrial fermentation of Suanzhou.

1. Introduction

Grain fermented food is a type of food fermented by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), yeast and other beneficial microorganisms using raw food crops including cereal crops (rice, wheat), legume crops (beans), and potato crops (potatoes), thereby changing the nutritional composition and producing unique flavor [1]. Compared to foods cooked directly from raw food crops, fermented grain foods not only increase the shelf life of food, but are generally more palatable, easier to digest, and rich in a variety of nutrients, such as vitamins, organic acids, and free amino acids [2]. Grain Fermented foods are consumed as a rich source of probiotic microbes, and can inhibit the growth of most pathogens [3].

Suanzhou is a traditional organic acid fermented food in northwest China, naturally fermented from proso millet (Panicum miliaceum, a specific drought-tolerant cereal with small, oval grains) and millet (a broad term encompassing other cereal species such as foxtail millet Setaria italica, characterized by slender, cylindrical grains, commonly used in Chinese traditional food). It has a pleasant sour and refreshing taste and great market development potential. Our previous study collected 59 samples of homemade Suanzhou, determined the contents of lactic acid, acetic acid and free amino acid in Suanzhou, and systematically analyzed the diversity of microbial community in Suanzhou using the combination of microbial isolation methods and microbial diversity composition spectrum sequencing. It was clear that Suanzhou is a nutritious food rich in free amino acids and organic acids, and LAB are the main bacterial species involved in Suanzhou fermentation [4].

LAB, as the initial culture, not only enhance the flavor of fermented products but can also be better preserved in fermented food due to their widespread antibacterial activity [5]. The metabolites secreted by LAB during the fermentation process, including lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins, contribute to inhibiting or killing three categories of harmful microbes: (1) spoilage-causing bacteria (e.g., Clostridium spp. and Pseudomonas spp.), (2) pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Salmonella spp. and Listeria spp.), and (3) toxin-producing bacteria (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, and Clostridium botulinum), which cause foodborne illness primarily through their production of toxic metabolites [6,7]. Using the method of artificially adding LAB during the fermentation process of Suzhou can inhibit the production of pathogenic microorganisms.

In addition, bacteria have developed various mechanisms to resist environmental stresses in nature, including extreme temperature, pH, osmotic pressure, and nutrient loss [8]; and the formation of biofilms is one of the mechanisms for survival. Bacteria that form biofilms can be protected from immune or drug clearance, thereby enhancing antimicrobial activity [9,10]. A previous study showed that Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Lactiplantibacillus fermentum could form biofilms on non-biological surfaces, and the density and ability to form biofilms varied between the strains; as well as the biofilm lifestyle is related to beneficial probiotic properties of Lactobacillus in a strain dependent manner [10]. Generally, microorganisms with good intestinal colonization ability tend to have strong biofilm-forming capacity—this is supported by literature showing that biofilms protect bacteria from gut environmental stresses (e.g., acidic pH, immune clearance) to enhance survival [11,12]. In our study, biofilm formation ability was quantified via crystal violet staining, where the optical density at 595 nm (OD595) directly reflected biofilm biomass [10,13].

Gut microbiome, the trillions of bacteria that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, has been found to be not only an essential component of immune and metabolic health, but also appears to influence the occurrence and development of gut and central nervous system diseases [14]. It is well known that probiotics such as LAB colonize in the gut, thereby regulating the gut microbiota and preventing diseases [15]. Mu et al. showed that Lactiplantibacillus reuteri could generate antibacterial molecules, and have the ability to strengthen the intestinal barrier, and its colonization could reduce microbial translocation from the intestinal lumen to tissues, thus improving inflammatory bowel diseases by increasing colonization of L. reuteri [16]. Another research analyzed the gut microbial structure and diversity of the mice treated with Lactiplantibacillus casei by gavage once (short-term) and 27 times (long-term) using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and found that long-term gavage of L. casei sy13 isolated from fermented dairy products could enhance the ability of colonization in the intestinal tract, but a single oral administration of L. casei sy13 had a greater impact on the gut microbiota structure at the phylum and genus levels than long-term treatment [15]. These indicated that LAB and the bioactive ingredients secreted by them proved to be beneficial to intestinal health by inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria and affecting microbial diversity.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAK) is a zoonotic pathogen. PAK infection in chicks leads to sepsis, respiratory and intestinal infections, and high mortality, whereas infection in humans results in severe lung damage, especially in immunocompromised patients [17]. Due to the development of antibiotic resistance, PAK infections are extremely difficult to treat, and the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from poultry products to humans also creates additional public health concerns [18]. Therefore, in this study, diverse LAB strains isolated from Suanzhou were characterized for their biofilm-forming ability, optimal growth temperature, pH preferences, and antimicrobial activity, to identify potential starter strains suitable for Suanzhou fermentation processes. Subsequently, two selected LAB strains were administered to Specific Pathogen-Free (SPF) chicks. Fecal samples were collected during and after the LAB supplementation period. The structure and diversity of the bacterial and fungal communities in the chick intestinal microbiota were analyzed by 16S rRNA V3–V4 region sequencing for bacteria, 16S rRNA V4–V5 region sequencing for archaea, and internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) sequencing for fungi, to elucidate the in vivo intestinal colonization of the LAB and their associated gut-protective mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Strains

In this study, a total of 70 LAB strains were isolated from Suanzhou, which were identified and preserved by the Center for Agricultural Genetic Resources Research, Shanxi Agricultural University (Taiyuan, China). Detailed protocols for their isolation and identification have been reported previously [4]. Briefly, LAB were selectively isolated using DeMan-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) agar, and their species identities were confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing (≥97% sequence similarity to reference strains in the NCBI GenBank database) (Table S1).

Additionally, the strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAK), Escherichia coli and Plesiomonas shigelloides, used as indicator bacteria, were kindly provided by Hongjiang Yang, professor of Tianjin University of Science and Technology (Tianjin, China). The characteristics of these indicator strains and their relevance to chick health or food safety are as follows: (1) S. aureus: A facultative pathogenic bacterium, not an indigenous chick gut colonizer. It contaminates the gut via feed, water, or environment and causes infections (e.g., dermatitis, septicemia) in young chicks. (2) B. subtilis (specific strain used here): A Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium. Unlike probiotic B. subtilis strains, this strain was selected as an indicator for its ability to form biofilms, enabling evaluation of LAB activity against spore-forming microbes relevant to poultry gut health. (3) PAK: An opportunistic pathogen that contaminates chick guts via contaminated water systems (e.g., water lines). It is not a normal gut resident but causes systemic infections in chicks, with its detection indicating poor water hygiene. (4) E. coli (pathogenic strain): A variant related to avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC). While non-pathogenic E. coli is part of the normal chick gut microbiota, this strain causes colibacillosis, a major disease leading to diarrhea and mortality in chicks. (5) P. shigelloides: A zoonotic pathogen with low pathogenicity to healthy chicks but potential to induce diarrhea in immunocompromised individuals. It poses a food safety risk, as it can transmit to humans via contaminated poultry products and cause gastrointestinal illness.

2.2. Screening of the Optimum Medium and Determination of Biofilm Production Capacity of LAB

Nine LAB strains were selected to screen for the optimum medium and determine biofilm production capacity, including h9-c (Lactiplantibacillus coryniformis), h12-c1 (Lactiplantibacillus parafarraginis), h24-c (Lactiplantibacillus pentosus), h27-c1 (Lactiplantibacillus rossiae), h28-c1 (L. casei), h29-c2 (Lactiplantibacillus harbinensis), p1-c2 (Limosilactobacillus brevis), p2-c1 (L. reuteri), and p30-c (L. fermentum). The strains were first inoculated into 5 mL of DeMan-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) liquid medium (Beijing Luqiao Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and cultured at 30 °C for 48 h. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 5 min, the pallets were resuspended with 1 mL sterile water, and the concentrations of the strains were adjusted so that the initial culture concentrations were consistent. Then, 80 μL of bacterial suspension was added to 7.92 mL MRS liquid medium, and mixed by vortex shaking. After that, 200 μL bacterial suspension was inoculated to each well of a 96-well plate in triplicate for each strain and cultured at 30 °C for 72 h. The same amount of medium was used as a blank control. Similarly, the bacterial solution was inoculated to Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) medium (Qingdao Hopebio, Qingdao, China) and Pantothenate Assay (Lactobacilli Broth, AOAC) medium (ELITE-MEDIA, Shanghai Sanshu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) using the same procedure. After being cultured at 30 °C for 72 h, crystal violet staining was used to measure the biofilm formation ability of different LAB strains by measuring the optical density (OD) of 595 nm [19].

Subsequently, all strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were inoculated into 5 mL of BHI liquid medium (Brain Heart Infusion medium). Then, 80 μL of bacterial suspension was transferred to 7.92 mL of the optimized medium. Afterwards, 200 μL of bacterial suspension was added to each well of a 96-well plate, with an equal volume of BHI medium serving as a blank control. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. Finally, the biofilm formation ability of all strains was assessed using crystal violet staining and then determining the OD595nm.

2.3. Determination of the Optimum Growth Temperature and pH of LAB

All 70 LAB strains were included for determining the optimum growth temperature and pH. The strains were firstly inoculated into the MRS liquid medium, and cultured at 30 °C for 18 h. After the concentrations of LAB were adjusted to be consistent (OD600nm = 0.4~0.5), the bacterial suspension was inoculated into fresh MRS liquid medium at a 1% inoculating rate, and cultured for 24 h under different temperature conditions (30 °C, 35 °C, 40 °C, 45 °C, 50 °C, and 55 °C) or different pH conditions (1.5, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, and 5.5). After culturing for 24 h, the OD values at 600 nm were measured using a microplate reader.

2.4. Antibacterial Effects of Different LAB Strains Using Agar Diffusion

The 70 LAB strains were first streaked on MRS agar plates and cultured at 30 °C for 48 h to obtain pure colonies. Single colonies from each strain were then inoculated into 3 mL of liquid MRS medium, cultured at 30 °C for 18 h, and subsequently transferred to 20 mL of fresh liquid MRS medium at a 2% inoculation rate for an additional 24 h of culture. For the antibacterial assay, a double-layer agar system was used: the lower layer was MRS agar medium, and the upper layer was vegan agar medium (to support indicator bacteria growth). The LAB bacterial suspension (containing LAB metabolites such as lactic acid, bacteriocins, and hydrogen peroxide) was directly used for the subsequent antibacterial test, without centrifugation or filtration steps, to ensure the integrity of the bacterial cells and their metabolites involved in antimicrobial activity. The indicator bacteria S. aureus, PAK, B. subtilis, P. Shigelomonas and E. coli were inoculated into 3 mL of Luria–Bertani (LB) medium, and cultured overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 180 r/min. Then, the bacterial suspension was inoculated into a 20 mL of fresh LB medium at a 1% inoculation rate.

The antibacterial effect was evaluated using the agar diffusion method with the Oxford cup technique [20]. Briefly, 20 mL of nutrient agar medium was poured into the plate. After solidification, the Oxford cup was gently pressed into the agar layer. Then, the indicator bacterial suspension was spread onto the plate. After solidification, the Oxford cup was removed, and 150 μL of LAB metabolites were added into each well, with a medium of the same pH value used as a control. To exclude potential pH-related effects on antimicrobial activity, the control group used MRS medium (the same medium for LAB culture) whose pH was adjusted to match that of the LAB bacterial suspension using lactic acid. Following diffusion at 4 °C for 1 h, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 14 h. The diameter of the inhibition zone was measured using a vernier caliper. The antibacterial ability of the LAB strains was determined by subtracting the inhibition zone diameter of the pH-adjusted MRS control from that of the LAB bacterial suspension, confirming that the activity was derived from soluble components in the bacterial suspension.

2.5. Animal Experiment and Sample Collection

A total of 50 one-day-old SPF chicks were purchased from Beijing Boehringer Ingelheim Vetec Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), and were maintained at a room temperature of 25 °C and a humidity of 50–70%, with a 12 h light/dark cycle. During the experiment, all chickens had free access to feed and water, and both feed and water were sterilized [21]. After a 7-day adaptation period, the chicks were randomly divided into two groups (n = 25 per group). Two isolated LAB strains (h8-c and p15-c, L. pentosus) were selected for incorporation into the feed, based on their comprehensive superior traits: (1) high biofilm-producing capacity (OD595nm values in BHI medium), (2) strong antibacterial activity against five indicator pathogens (largest inhibition zones), and (3) excellent stress tolerance (robust growth at pH 3.5 and 30–45 °C). During the subsequent 3-day administration period, the chicks in the two groups were fed daily with 20 mL of LAB suspensions at a concentration of 108 CFU/mL each. The process of administering lactic acid bacteria involved students preparing the bacterial suspension and adding it to the feed. The caretakers treated the two experimental groups as parallel trials and were not informed of the differences between the groups. After the 3-day administration period, a recovery phase began, during which all chicks received normal feeding for an additional three weeks. Fecal samples were collected from each group at five time points: D0 (day before the administration period), D3 (day 3 of the administration period), R7 (day 7 of the recovery period), R14 (day 14 of the recovery period), and R21 (day 21 of the recovery period). After the experiment was completed, the chicks were given to local farmers to continue raising them.

Our experimental design focused on two key comparisons to evaluate LAB-induced gut microbiota changes: (1) Intra-group temporal comparison (primary focus): For each group, fecal samples were collected at five time points (D0: pre-administration baseline; D3: end of administration; R7/R14/R21: 7/14/21 days post-administration) to compare the abundance and diversity of gut Lactobacillus (and overall microbiota) before, during, and after LAB supplementation. This directly assessed whether LAB addition altered the gut microbiota relative to the group’s own baseline. (2) Inter-group reference: The two strains served as mutual references to compare differences in their effects on gut microbiota structure (e.g., Lactobacillus colonization efficiency, fiber-degrading bacterial enrichment). No external commercial probiotic strain was used as a control, as our core goal was to validate the gut-modulating potential of these Suanzhou-isolated strains rather than compare them to commercial probiotics.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Medical Advisory Committee guidelines using approved procedures of the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee at Tianjin University of Science and Technology.

2.6. Microbial Diversity Composition Profile Analysis

The fecal samples were sent to Personalbio Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for 16S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS sequencing. Briefly, total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from each fecal sample using the QIAamp DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, One part of the DNA samples was used to amplify the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene with the barcoded primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′); another part of the DNA samples were used to amplify the V4-V5 region of the archaeal 16S rRNA gene with the barcoded primers 524F (5′-TGYCAGCCGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 958R (5′-YCCGGCGTTGAVTCCAATT-3′); and the final part of the DNA samples was used to amplify the V1 region of ITS with the barcoded primers 5F (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) and ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). PCR amplification products were separated by 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis, then extracted and purified using the AXYGEN gel recovery kit(Axygen, Union City, CA, USA). The purified products were quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Molecular Probes by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR, USA), and pooled into equal concentrations. An equal amount of DNA from the pool was used to prepare the sequencing libraries with the TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The quality of sequencing libraries was assessed using an Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and quantified with the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) on the Promega QuantiFluor system following the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, an illumina MiSeq sequencer with the MiSeq Reagent Kit V3 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) (600 cycles) was used for 16S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS sequencing.

2.7. Sequencing Data Analysis

The QIIME software (version 1.8.0) was used to analyze the raw sequencing data. Quality filtering, sequence assembly, and removal of chimeric sequences were performed using the USEARCH method (v5.2.236) to generate operational taxonomic unit (OTU) information for each sample at a 97% similarity threshold, followed by taxonomic classification. Subsequently, the Greengenes reference database (release 13.8) and the UNITE reference database (release 8.0) were employed to annotate OTUs obtained from 16S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS sequencing, respectively. Alpha and beta diversity analyses were then conducted using QIIME.

Species composition and abundance distribution tables at the phylum and genus levels were generated for each sample using QIIME, and the results were visualized as bar plots with R software (version 3.3.1). Cluster analysis was performed on the top 50 most abundant genera using the pheatmap package in R (version 3.3.1), and a heatmap was generated. UPGMA clustering analysis was applied to the Weighted UniFrac distance matrix using QIIME, and the results were visualized with R software. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (Spearman’s rho) among the top 50 most abundant dominant genera (across bacteria, fungi, and archaea) were calculated using Mothur (v1.39.5). Correlation networks were constructed based on two strict criteria: (1) Spearman’s rho > 0.6 (indicating a strong association) and (2) a p-value < 0.01 (ensuring statistical significance). The filtered networks were imported into Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/, accessed on 15 April 2025) for visualization.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated three times, and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The Excel software was used to draw the figures and to perform statistical analysis. Heatmap_barplot analysis was performed using the OmicStudio tools at https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool, accessed on 25 August 2025.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Biofilm Production of the LAB Strains

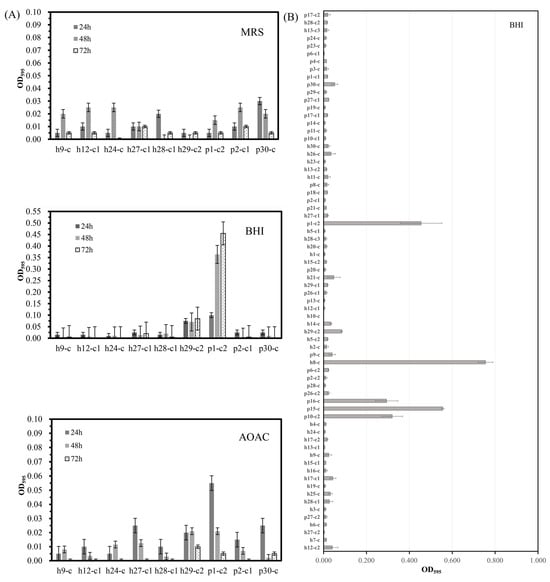

First, the optimum medium for biofilm production was screened in the preliminary experiment. Nine strains of LAB were cultured in MRS, BHI, and AOAC medium for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, and it was found that the OD595nm values of h29-c2 (L. harbinensis) and p1-c2 (L. brevis) in the BHI medium were higher, suggesting that the two strains might have better biofilm formation ability in the BHI medium (Figure 1A). We also found that h29-c2 and p1-c2 had the best biofilm formation ability in the BHI medium after being cultured for 72 h (Figure 1A), but for screening strains with strong biofilm production ability, differences among strains could be distinguished after 48 h of culture. These results indicated that the BHI medium was selected as the optimum medium for the determination of LAB biofilm, and the culture time was set at 48 h.

Figure 1.

Biofilm production capacity of the LAB strains cultured in the media. (A) Biofilm production (OD595nm) of 9 LAB strains cultured in DeMan-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) medium, Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) medium, and Pantothenate Assay (AOAC) medium for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. (B) Biofilm production (OD595nm) of all the isolated LAB strains after incubation in BHI medium for 48 h using crystal violet staining.

All 70 strains of LAB were used to determine their biofilm formation ability. As shown in Figure 1B, the average OD595nm values of h8-c (L. pentosus), p15-c (L. pentosus), p10-c2 (L. pentosus), p16-c (L. pentosus), and p1-c2 (L. brevis) were 0.747, 0.556, 0.320, 0.294, and 0.455, respectively, which were higher than those of other strains. These findings suggested that h8-c, p15-c, p10-c2, p16-c, and p1-c2 had higher biofilm formation ability, aligning with this colonization-biofilm association, and could be used for further experiments.

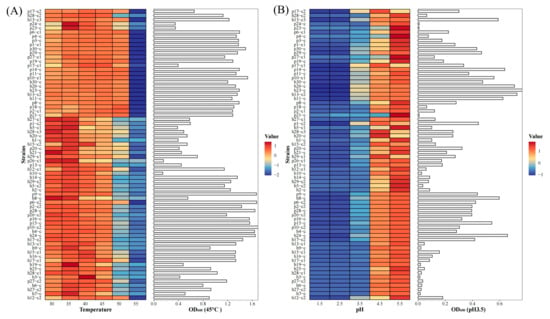

3.2. Determination of the Optimum Growth Temperature and pH for LAB

Further, the optimum temperature and pH for the growth of all the 70 strains of LAB were analyzed. These strains exhibited robust thermotolerant characteristics, with the majority demonstrating excellent temperature adaptability within the range of 30–45 °C. Notably, among the five strains with strong biofilm-forming capacity (h8-c, p15-c, p10-c2, p16-c, and p1-c2), four strains (p15-c, p10-c2, p16-c, and p1-c2) displayed pronounced thermal adaptability at 30–45 °C, whereas h8-c showed relatively reduced tolerance. At 50 °C, the OD600nm values of all strains decreased significantly, and no growth was observed at 55 °C (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Determining the optimum growth temperature and pH levels of the LAB strains. (A) OD600nm values of the isolated LAB after 24 h growth at different temperatures. Left panel: the heatmap of OD600nm values of the isolated LAB at different temperatures. Right panel: the actual OD600nm values at 45 °C. (B) OD600nm values of the isolated LAB after 24 h growth under different pH conditions. Left panel: the heatmap of OD600nm values of the LAB at different pH. Right panel: the actual OD600nm values at pH3.5. The color scale represents the OD600nm value.

Regarding pH tolerance, bacterial growth diminished progressively with decreasing pH. Most strains grew normally at pH 4.5 and 5.5. However, when the pH was reduced to 3.5, strain-specific acid tolerance variability became evident: 14 strains maintained OD600nm values above 0.4, while the remaining strains exhibited marked growth inhibition. The five high-biofilm-producing strains (h8-c, p15-c, p10-c2, p16-c, and p1-c2) demonstrated notable acid resistance at pH 3.5, with OD600nm values of 0.632, 0.579, 0.341, 0.343, and 0.478, respectively. All strains failed to grow at pH 1.5 and 2.5 but thrived at pH 5.5 (Figure 2B).

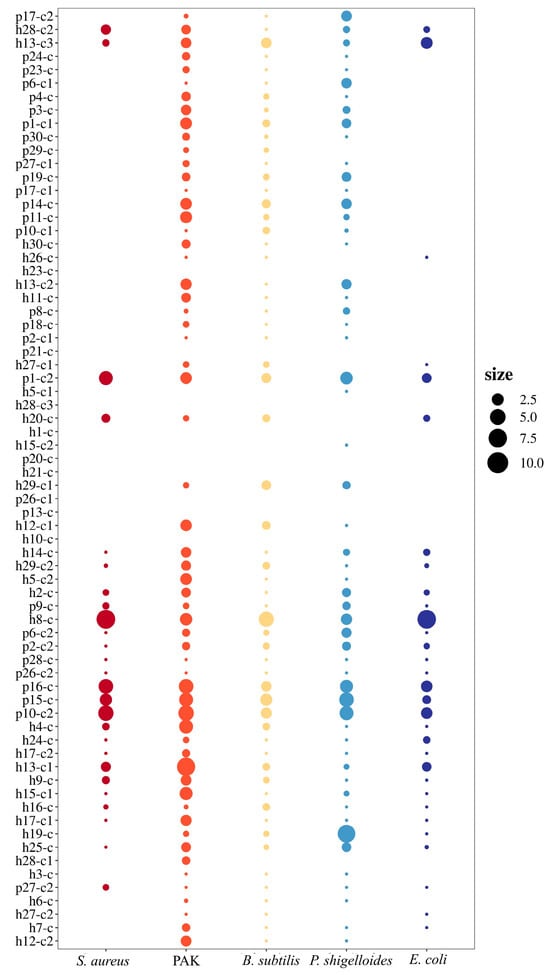

3.3. The Antibacterial Effects of the LAB

Lactic acid at the same pH was used as the control, and the antibacterial zones formed by LAB on the dual-culture medium was larger than those formed by the controls, indicating antibacterial activity against the indicator bacteria. Among the 70 LAB strains, they showed substantial variability in their inhibitory effects against five indicator strains: S. aureus, B. subtilis, PAK, P. shigelloides, and E. coli. Focusing on the five high-biofilm-producing strains (h8-c, p10-c2, p15-c, p16-c, and p1-c2), their suspension all exhibited broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against the tested pathogens (Figure 3), confirming that the antibacterial effect was mediated by soluble metabolites in the supernatant. The size of the bubbles in Figure 3 represents the ratio of inhibition zone diameters formed by the LAB supernatant to that formed by the pH-adjusted MRS control (matched to the LAB supernatant’s pH to exclude pH-driven effects). The larger bubbles indicate stronger specific antibacterial activity, while ratios close to 1 indicate minimal specific activity. Based on inhibition zone measurements, h8-c and p15-c demonstrated the strongest antimicrobial efficacy against all five indicator strains. Due to their superior antimicrobial performance and high biofilm-forming capacity, strains h8-c and p15-c were selected for subsequent animal experiments.

Figure 3.

Bubble chart of the antibacterial effects of 70 LAB strains against the indicator strains. Different colors mean different indicator bacterial stains. The size of the bubbles represents the ratio of inhibition zone diameters formed by the LAB supernatant to that formed by the pH-adjusted MRS control (matched to the LAB supernatant’s pH to exclude pH-driven effects). The larger bubbles indicate stronger specific anti-bacterial activity, while ratios close to 1 indicate minimal specific activity.

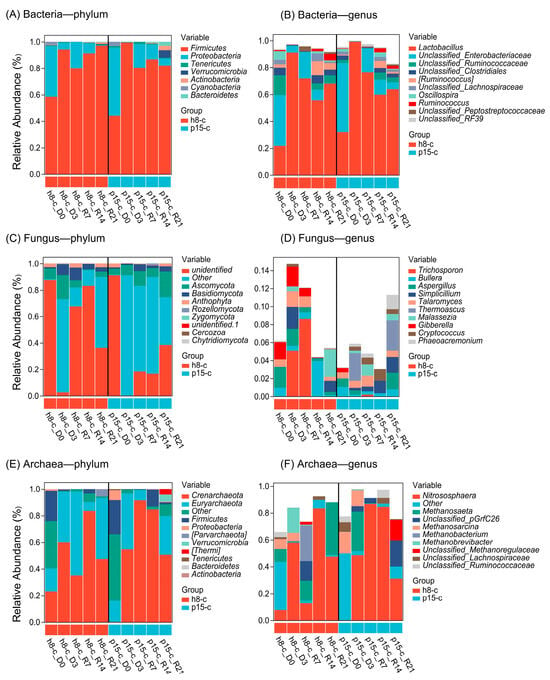

3.4. Species Composition of the Bacterial, Fungal, and Archaeal Communities in the Gut Microbiota

A chick Lactobacillus feeding model was established (Figure S1), in which chicks were administered the screened L. pentosus strains h8-c and p15-c, respectively. Fecal samples were collected during both the administration and recovery period, and amplicon-based diversity analysis was performed to assess the microbial diversity of gut bacteria, fungi, and archaea. As indicated by the Chao1, observed species, and Shannon curves (Figure S2), the curves reached plateaus, demonstrating that the sequencing depth was sufficient for reliable data analysis. The average read lengths for the bacterial 16S rRNA V3–V4, fungal ITS 1, and archaeal 16S rRNA V4–V5 regions were 425 bp, 287 bp, and 411 bp, respectively (Table S2).

Figure 4 illustrates the differences in community structure between the h8-c and p15-c groups across the three domains of Bacteria, Fungi, and Archaea. For Bacteria (panels A, B), at the phylum level, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria dominated both groups, together accounting for 80–99% of all sequences. At the genus level, Lactobacillus was the dominant taxon in both groups. On day 3 after probiotic administration, Lactobacillus sharply increased to 91% (h8-c) and 99% (p15-c). During the subsequent recovery period (sampling every 7 days after cessation of supplementation), Lactobacillus gradually declined but remained significantly elevated at 68% (h8-c) and 63% (p15-c) on day 21 (R21) compared with the baseline (D0), indicating robust colonization in the chick intestine. The decline of Lactobacillus during recovery was accompanied by a concomitant rise in unclassified-Enterobacteriaceae. Between the two groups, p15-c exhibited higher relative abundances of fibre-degrading genera such as unclassified-Ruminococcaceae, unclassified-Clostridiales, and Oscillospira than h8-c. For Fungi (panels C, D), at the phylum level, >80% of sequences were assigned to “unidentified” or “others”; Basidiomycota and Ascomycota together comprised <20%. At the genus level, “unidentified” taxa remained predominant in both groups. Following probiotic administration, h8-c showed a marked decrease in Trichosporon and Cryptococcus, whereas Thermoascus increased notably during recovery (R14 and R21). In p15-c, Gibberella was significantly enriched on day 3 post-administration. For Archaea (panels E, F), Euryarchaeota was the dominant phylum in both groups and increased significantly after probiotic feeding. At the genus level, Nitrososphaera increased following supplementation and maintained high abundance throughout the recovery period in both groups.

Figure 4.

Relative abundance of bacteria, fungi, and archaea in the gut microbiota. (A) bacterial community composition at the phylum level; (B) bacterial community composition at the genus level; (C) fungal community composition at the phylum level; (D) fungal community composition at the genus level; (E) archaeal community composition at the phylum level; (F) archaeal community composition at the genus level. Five time points: D0, day before the administration period; D3, day 3 of the administration period; R7, day 7 of the recovery period; R14, day 14 of the recovery period; R21, day 21 of the recovery period.

In summary, p15-c displayed concurrent enrichment of fiber-degrading bacteria, acetoclastic methanogenic archaea, and potentially opportunistic fungi, suggesting a shift toward a “high-fiber fermentation–acetoclastic methanogenesis” microbiome. In contrast, h8-c maintained a stable community dominated by Lactobacillus and hydrogenotrophic methanogens.

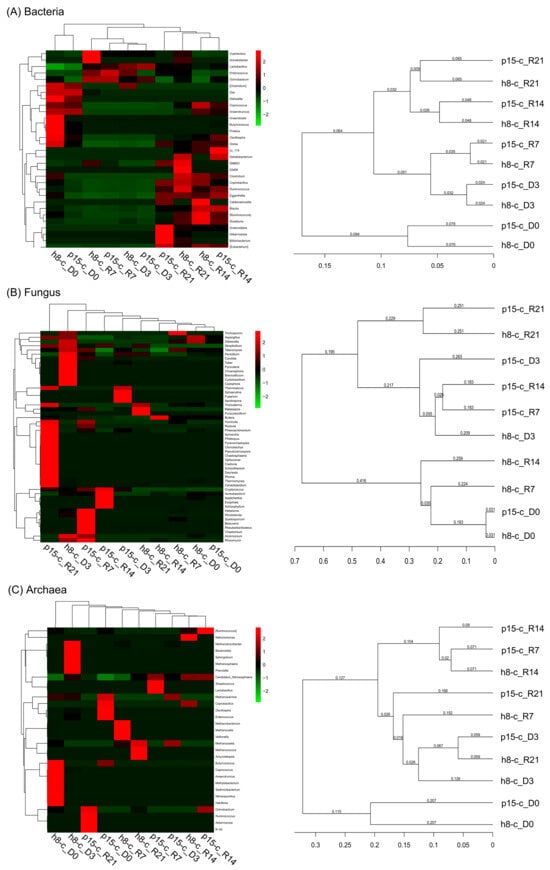

3.5. Beta Diversity of the Bacterial, Archaeal, and Fungal Communities in the Gut Microbiota

Based on the abundance of the top 50 genera, cluster analysis revealed distinct microbial profiles, visualized in a heatmap; additionally, UPGMA clustering of Weighted UniFrac distances illustrated the phylogenetic relationships among samples. As shown in Figure 5, Lactobacillus supplementation induced distinct temporal trajectories in bacterial, fungal, and archaeal communities. In the bacterial heatmap (panel A), the two groups exhibited high similarity at the baseline (D0); immediately after probiotic administration (D3 and R7) their profiles remained closely related, whereas the late recovery phase (R14 and R21) again formed coherent clusters. The corresponding dendrogram mirrored this pattern, indicating that probiotic feeding substantially reshaped the cecal bacterial assemblage, with D0 samples being the most dissimilar to all subsequent time points. Fungal similarities (panel B) were markedly lower, high values (>0.90) were restricted to consecutive sampling intervals within the same treatment. Notably, p15-c_D3 clustered tightly with all subsequent recovery samples (R7, R14, R21), whereas h8-c_D3 displayed a more variable relationship with its own recovery series, implying that the p15-c mycobiota stabilised rapidly post-intervention, whereas the h8-c fungal community remained more dynamic. Archaeal profiles (panel C) followed a clear “treatment-by-time” structure: all p15-c recovery specimens first coalesced with p15-c_D3 and only then joined the p15-c_D0 branch; h8-c samples likewise grouped chronologically, while the inter-treatment boundary was sharply defined, underscoring the high specificity and temporal continuity of archaeal responses to Lactobacillus administration. Collectively, the hierarchical clustering demonstrates that bacteria are most responsive to treatment grouping, fungi exhibit the greatest variability, and archaea display pronounced temporal persistence coupled with treatment-specific divergence.

Figure 5.

The 50 most abundant genera heatmap and weighted UniFrac distance matrix. (A) Bacterial community; (B) fungal community; (C) archaeal community. Left panel: heatmap of the 50 most abundant genera. The color gradient from green to red indicates the similarity coefficient ranging from low to high. Right panel: the weighted UniFrac distance matrix. The scale represents phylogenetic distance. Five time points: D0, day before the administration period; D3, day 3 of the administration period; R7, day 7 of the recovery period; R14, day 14 of the recovery period; R21, day 21 of the recovery period.

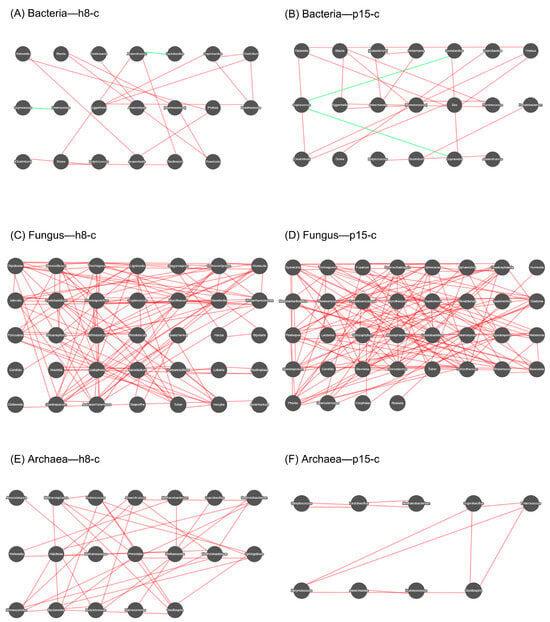

3.6. Network of the Bacterial, Archaeal, and Fungal Communities in the Gut Microbiota

Spearman’s rho was calculated among the top 50 dominant genera based on abundance, and correlation networks were constructed for those filtered dominant genera with rho > 0.6 and a p-value < 0.01. Figure 6 displays the microbial co-occurrence networks constructed based on 16S/ITS sequencing data, which illustrate the interrelationships among microbial members across bacterial, fungal, and archaeal communities in the h8-c and p15-c groups, respectively. In the networks, OTUs (97% similarity) represent nodes, with red edges representing positive correlations and green edges representing negative correlations.

Figure 6.

Correlation network diagrams of dominant bacterial, fungal, and archaeal genera. Nodes represent the dominant genera. Connections between nodes indicate correlations between two genera, with red lines representing positive correlations and green lines representing negative correlations. The more connections a node has, the more interactions the genus exhibits with other members of the microbial community.

In the bacterial network, the h8-c network (A) comprised core nodes formed by Lactobacillus and Lachnospiraceae, constituting a tightly knit positive correlation cluster. The p15-c network (B) exhibited an additional fiber-degrading module centered around unclassified Ruminococcaceae, Oscillospira, and Clostridiales, showing significant positive correlations with butyrate-producing bacteria. Negative correlations were primarily observed between Escherichia-Shigella and dominant symbiotic bacteria, suggesting potential competition. The fungal network was larger in scale, with relatively close and stable associations. The h8-c network (C) featured Cryptococcus and Talaromyces as key nodes, while the p15-c network (D) formed a highly interconnected module centered around Gibberella with Trichosporon and Aspergillus, indicating synergistic enrichment of opportunistic pathogens. The archaeal network exhibited a small but compact structure. The h8-c network (E) featured Methanobrevibacter as the largest node, while the p15-c network (F) showed strong positive correlations with unclassified Ruminococcaceae, supporting a functional coupling between fiber fermentation and acetoclastic methanogenesis.

In summary, the p15-c group demonstrated greater complexity in co-occurrence networks across all three domains: an enhanced fiber-degrading module at the bacterial level, synergistic emergence of opportunistic pathogens at the fungal level, and increased centrality of acetoclastic methanogenesis nodes at the archaeal level. In contrast, the h8-c group exhibited greater stability in maintaining the balance among intestinal bacteria, fungi, and archaea.

4. Discussion

Lactic acid bacteria, a group of Gram-positive microorganisms naturally present in fermented foods and used as probiotics, have been of interest to researchers for many years as an effective source of bioactive compounds with a variety of functions and activities [22]. Suanzhou is a homemade dish naturally fermented by grains, and our previous study found that lactic acid bacteria are the primary strains in Suanzhou fermentation [4]. Our study identified the strains of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Suanzhou, as well as observed that h8-c (L. pentosus), p15-c (L. pentosus), p10-c2 (L. pentosus), p16-c (L. pentosus), and p1-c2 (L. brevis) had higher biofilm formation ability, and that the suspension of h8-c and p15-c (L. pentosus) with high-yielding biofilms exhibited better inhibitory properties against all the indicator pathogens (S. aureus, B. subtilis, PAK, E. coli and Shigelomonas). This aligns with previous findings that LAB-derived metabolites (secreted into the supernatant) are key mediators of antimicrobial activity against spoilage and pathogenic bacteria [23,24]. Subsequently, the intestinal colonization and related intestinal protective mechanisms of h8-c and p15-c were investigated in the intestinal tract of SPF chicks using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS sequencing, which represents a novel and innovative aspect of this study.

Biofilms are communities of microorganisms that adhere to the surface, and exist within a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric material [17]. Biofilms provide a higher survival advantage for bacteria, allowing them to persist and resist host immunity and antimicrobial therapy [25]. A previous study of Stivala et al. [26] demonstrated that L. rhamnosus AD3 had stronger biofilm formation ability, resistance to low pH and bile salts (before and after exposure), and higher adhesion and auto-aggregation, suggesting its potential as a promising probiotic to promote vaginal health in women. Based on our results, h8-c and p15-c, which belong to L. pentosus, had stronger biofilm formation ability and inhibitory effects against the pathogens, as well as good tolerance to low pH values, and the optimal growth temperature and pH for the h8-c and p15-c strains were 30 °C and 5.5, respectively. L. pentosus, a species of lactic acid bacteria, was reported to consume xylose more efficiently and to hydrolyze sugarcane bagasse to produce lactic acid, thus improving the economic feasibility of lactic acid production through low-cost substrate fermentation [27]. Another study used chestnut residue as the fermentation substrate, and discovered that the yield of lactic acid fermented by L. pentosus was higher compared with the other two strans, L. plantarum and Lactococcus lactis [28]. Taken together, h8-c and p15-c (L. pentosus) with better inhibitory effects against pathogens in vitro and high-yielding biofilm ability could be selected for further in vivo experiments, and may be suitable candidates for Suanzhou fermentation.

The robust in vitro characteristics of h8-c and p15-c provide a plausible mechanistic basis for their in vivo performance. First, the strains’ high biofilm-forming capacity (OD595 = 0.747 for h8-c, 0.556 for p15-c) and robust acid tolerance (OD600 > 0.5 at pH 3.5) directly facilitated their persistent intestinal colonization. At R21 (21 days post-supplementation), Lactobacillus abundance remained 68% (h8-c) and 63% (p15-c), significantly higher than baseline (D0), a outcome likely enabled by biofilms protecting the strains from the acidic chick gut environment and immune clearance [29,30]. Their adaptability to 30–45 °C (Figure 2A) further aligned with the chick gut’s physiological temperature (~40 °C), ensuring metabolic activity and competitive exclusion of pathogens. To further investigate the effects of the strains h8-c and p15-c (L. pentosus) on intestinal colonization and health in vivo, SPF chicks were administered with h8-c and p15-c separately. At the phylum level, both the h8-c and p15-c groups were dominated by Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, which collectively accounted for 80% to 99% of the total sequences in each group. At the genus level, Lactobacillus was the predominant genus in both groups. On day 3 after administration of Lactobacillus strains h8-c or p15-c, the relative abundance of Lactobacillus significantly increased to 91% and 99%, respectively. Even after discontinuation of Lactobacillus supplementation, by day 21 of the recovery period, the abundance of Lactobacillus remained high at 68% and 63%, values significantly elevated compared to those before administration (D0). This indicates that both h8-c and p15-c exhibited strong colonization capacity in the chick intestine. The decrease in Lactobacillus abundance during the recovery period was accompanied by an increase in Unclassified_Enterobacteriaceae, which is consistent with the antagonistic interaction between these two taxa observed in the network analysis. Lactobacillus, which belongs to Firmicutes, is one of the most important probiotics in the gut microbiome. These intestinal resident Lactobacillus species not only communicate with each other, but also with the intestinal epithelial cells to help maintain intestinal barrier integrity, enhance mucosal barrier defense and improve host immune response [31]. A growing body of evidence supports the important roles of Lactobacillus and their components (such as metabolites, peptidoglycan, and/or surface proteins) in the regulation of immune responses, primarily through the exchange of immune signals between the gastrointestinal tract and distant organs [31,32]. Prevotella, commonly distributed in the gut microbiome, has been reported to increase in abundance in association with Th17-mediated immune responses in many inflammatory diseases [33]. Rahayu et al. [34] demonstrated that L. plantarum Dad-13 could survive and colonize in the human gastrointestinal tract, and that consumption of its powdered form could result in a decrease in Firmicutes abundance and an increase in Bacteroides abundance (especially Prevotella), thereby reducing body weight and BMI in obese people. Another study illustrated that L. plantarum DP189 could alleviate neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease (PD) mice by reducing the abundance of pathogenic bacteria (Actinomycetes and Proteobacteria) and increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria (Lactobacillus and Prevotella), thereby reshaping the intestinal microbiome of PD mice [35]. Combined with our results, we speculate that h8-c and p15-c (L. pentosus) may promote the intestinal colonization of Lactobacillus, thereby balancing the intestinal flora of chicks and promoting intestinal health.

This colonization drove distinct, beneficial shifts across all three microbial domains. For bacteria, h8-c maintained a stable Lactobacillus-dominant community, which suppressed the proliferation of opportunistic Enterobacteriaceae (a common source of chick gut dysbiosis) and reinforced intestinal barrier integrity via Lactobacillus-derived metabolites (e.g., bacteriocins) [36]. In contrast, p15-c enriched fiber-degrading taxa (unclassified-Ruminococcaceae, Oscillospira), which enhance carbohydrate fermentation and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, key for nutrient absorption and gut epithelial health [37,38]. For fungi, h8-c reduced the abundance of potentially pathogenic genera (Trichosporon, Cryptococcus), while p15-c transiently enriched Gibberella (a genus linked to plant fiber degradation) during supplementation, reflecting strain-specific fungal modulation. For archaea, both strains elevated Euryarchaeota (the dominant archaeal phylum), but h8-c favored Methanobrevibacter (hydrogenotrophic methanogens, supporting efficient hydrogen scavenging), whereas p15-c enriched Nitrososphaera (acetoclastic methanogens, aligning with its fiber-degrading bacterial profile) [29]. These archaeal shifts indicate improved gut fermentation balance, a often-overlooked marker of gut health [39]. Collectively, these data demonstrate that h8-c and p15-c may exert strain-specific, multifaceted benefits: h8-c prioritizes stable Lactobacillus colonization to strengthen barrier function, while p15-c enhances metabolic diversity via fiber-degrading microbes, both supported by their in vitro biofilm and stress tolerance traits. This integration confirms the strains’ suitability as Suanzhou fermentation starters and probiotics for chick gut health.

However, it should be noted that this study has certain limitations. The animal experiments were conducted under SPF conditions with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the results to commercial poultry farming environments. Additionally, while 16S rRNA and ITS sequencing provided insights into microbial community changes, metagenomic or metabolomic analyses would be necessary to fully elucidate the functional mechanisms underlying the observed effects. Future studies should consider larger-scale trials under practical farming conditions and incorporate multi-omics approaches to validate these preliminary findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, L. pentosus h8-c and p15-c exhibited better inhibitory effects against pathogens and high-yielding biofilm ability, making them appropriate candidates for Suanzhou fermentation. Additionally, administration of L. pentosus h8-c and p15-c promoted intestinal colonization of Lactobacillus, and helped maintain the balance of the gut microbiota, thereby promoting intestinal health. Our findings provide novel insights into the regulation of gut microbiota disturbance and the restoration of the interaction between host and gut microbiota by L. pentosus h8-c and p15-c, as well as lay a foundation for their use as potential starter cultures for Suanzhou fermentation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010006/s1, Table S1: Lactic acid bacterial strains used in the article; Table S2: Sequencing statistics table per sample based on the Bacteria 16S rRNA V3–V4, Fungi ITS1 and Archaea 16S rRNA V4–V5; Table S3: OTUs based on the Bacteria 16S rRNA V3–V4; Table S4: OTUs based on the Fungi ITS1; Table S5: OTUs based on the Archaea 16S rRNA V4–V5; Table S6-1: Phylum-level classification table (top 10 taxa by relative abundance) based on bacteria 16S rRNA V3–V4 sequencing; Table S6-2: Genus-level classification table (top 10 taxa by relative abundance) based on bacteria 16S rRNA V3–V4 sequencing; Table S7-1: Phylum-level classification table (top 10 taxa by relative abundance) based on Fungus ITS1 sequencing; Table S7-2: Genus-level classification table (top 10 taxa by relative abundance) based on Fungus ITS1 sequencing; Table S8-1: Phylum-level classification table (top 10 taxa by relative abundance) based on Archaea 16S rRNA V4–V5 sequencing; Table S8-2: Genus-level classification table (top 10 taxa by relative abundance) based on Archaea 16S rRNA V4–V5 sequencing; Figure S1: Schematic diagram of the Lactobacillus feeding model; Figure S2: chao1, observed species and Shannon curve.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Q. and Z.M.; methodology, H.L., Z.H., Z.Z. and H.W.; data curation, H.L., Z.H., Z.Z. and H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Q.; writing—reviewing and editing, Z.Q., H.Y. and Z.M.; visualization and software, X.C., M.L. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province, grant number 202103021224158, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 31601457, the earmarked fund for CARS, grant number CARS-06-14.5-A16.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the experiments posed minimal impact on the chicks’ lives.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited (PRJCA046027) in the Genome Sequence Archive in the BIG Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, under accession codes subPRO067582 for bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 regions, fungal ITS1 regions and archaea 16S rRNA V4–V5 sequencingsequencing data, publicly accessible at http://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa (accessed on 10 September 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The author Zhiwei Huang is an employee of MDPI; however, they do not work for the journal Fermentation at the time of submission and publication.

References

- Salmeron, I. Fermented cereal beverages: From probiotic, prebiotic and synbiotic towards Nanoscience designed healthy drinks. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 65, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Warner, R.D.; Shen, S.; Fang, Z. Cereal grain-based functional beverages: From cereal grain bioactive phytochemicals to beverage processing technologies, health benefits and product features. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2404–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Burgos, M.; Moreno-Fernández, J.; Alférez, M.J.M.; Díaz-Castro, J.; López-Aliaga, I. New perspectives in fermented dairy products and their health relevance. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Sun, Q.; Pan, X.; Qiao, Z.; Yang, H. Microbial Diversity and Biochemical Analysis of Suanzhou: A Traditional Chinese Fermented Cereal Gruel. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.R.; Dobson, R.C.J.; Morris, V.K.; Moggré, G.J. Fermentation of plant-based dairy alternatives by lactic acid bacteria. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 1404–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özogul, F.; Hamed, I. The importance of lactic acid bacteria for the prevention of bacterial growth and their biogenic amines formation: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1660–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Functional role of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in cocoa fermentation processes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, N.; Li, J.; Shin, H.-D.; Du, G.; Chen, J.; Liu, L. Microbial response to environmental stresses: From fundamental mechanisms to practical applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 3991–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Hao, L.; Zhou, R.; Jin, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, C. Multispecies biofilms in fermentation: Biofilm formation, microbial interactions, and communication. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3346–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoudia, N.; Rieu, A.; Briandet, R.; Deschamps, J.; Chluba, J.; Jego, G.; Garrido, C.; Guzzo, J. Biofilms of Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus fermentum: Effect on stress responses, antagonistic effects on pathogen growth and immunomodulatory properties. Food Microbiol. 2016, 53, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Gupta, J.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A. Gut biofilm forming bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 112, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, J.P.; Wallace, J.L.; Buret, A.G.; Deraison, C.; Vergnolle, N. Gastrointestinal biofilms in health and disease. Nature reviews. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, W.; Su, J.; Liu, J. The Association of Biofilm Formation with Antibiotic Resistance in Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fermented Foods. J. Food Saf. 2013, 33, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, B.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Nassar, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Pang, X.; et al. Stable Colonization of Orally Administered Lactobacillus casei SY13 Alters the Gut Microbiota. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5281639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Q.; Tavella, V.J.; Luo, X.M. Role of Lactobacillus reuteri in Human Health and Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gu, N.; Huang, T.Y.; Zhong, F.; Peng, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A typical biofilm forming pathogen and an emerging but underestimated pathogen in food processing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1114199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghany, W.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of avian origin: Zoonosis and one health implications. Vet. World 2021, 14, 2155–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.A. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2011, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Brienza, C.; Moles, M.; Ricciardi, A. A comparison of methods for the measurement of bacteriocin activity. J. Microbiol. Methods 1995, 22, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Urban-Chmiel, R.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wernicki, A. Probiotic potential of Lactobacillus isolates of chicken origin with anti-Campylobacter activity. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 80, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, K. Anticancer activity of lactic acid bacteria. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamalifar, H.; Rahimi, H.; Samadi, N.; Shahverdi, A.; Sharifian, Z.; Hosseini, F.; Eslahi, H.; Fazeli, M. Antimicrobial activity of different Lactobacillus species against multi- drug resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2011, 3, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Bai, H.; Mo, W.; Zheng, X.; Chen, H.; Yin, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zuo, Z.; et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Bacteriocins: Safe and Effective Antimicrobial Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leska, A.; Nowak, A.; Czarnecka-Chrebelska, K.H. Adhesion and Anti-Adhesion Abilities of Potentially Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria and Biofilm Eradication of Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Pathogens. Molecules 2022, 27, 8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivala, A.; Carota, G.; Fuochi, V.; Furneri, P.M. Lactobacillus rhamnosus AD3 as a Promising Alternative for Probiotic Products. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischral, D.; Arias, J.M.; Modesto, L.F.; de França Passos, D.; Pereira, N., Jr. Lactic acid production from sugarcane bagasse hydrolysates by Lactobacillus pentosus: Integrating xylose and glucose fermentation. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019, 35, e2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Trigo, I.; Otero-Penedo, P.; Outeirino, D.; Paz, A.; Dominguez, J.M. Valorization of chestnut (Castanea sativa) residues: Characterization of different materials and optimization of the acid-hydrolysis of chestnut burrs for the elaboration of culture broths. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Nakatsu, C.H.; Bhunia, A.K. Bacterial Biofilms and Their Implications in Pathogenesis and Food Safety. Foods 2021, 10, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yao, H.; Zhao, X.; Ge, C. Biofilm Formation and Control of Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.; Singh, A. Gut microbiome and human health: Exploring how the probiotic genus Lactobacillus modulate immune responses. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeney, D.D.; Gareau, M.G.; Marco, M.L. Intestinal Lactobacillus in health and disease, a driver or just along for the ride? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tang, J.; Cai, Z.; Zhou, K.; Chang, L.; Bai, Y.; Ma, Y. Prevotella Induces the Production of Th17 Cells in the Colon of Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 9607328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Mariyatun, M.; Manurung, N.E.P.; Hasan, P.N.; Therdtatha, P.; Mishima, R.; Komalasari, H.; Mahfuzah, N.A.; Pamungkaningtyas, F.H.; Yoga, W.K.; et al. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Dad-13 powder consumption on the gut microbiota and intestinal health of overweight adults. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, C.; Gao, L.; Niu, C.; Li, S. Lactobacillus plantarum DP189 Reduces α-SYN Aggravation in MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Mice via Regulating Oxidative Damage, Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota Disorder. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeney, D.D.; Zhai, Z.; Bendiks, Z.; Barouei, J.; Martinic, A.; Slupsky, C.; Marco, M.L. Lactobacillus plantarum bacteriocin is associated with intestinal and systemic improvements in diet-induced obese mice and maintains epithelial barrier integrity in vitro. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogal, A.; Valdes, A.M.; Menni, C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between gut microbiota and diet in cardio-metabolic health. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1897212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblut, N.D.; Reischer, G.H.; Dauser, S.; Maisch, S.; Walzer, C.; Stalder, G.; Farnleitner, A.H.; Ley, R.E. Vertebrate host phylogeny influences gut archaeal diversity. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.