Abstract

The presented article is focused on the study of amino acid metabolism and the related production of fusel alcohols and their esters in the secondary fermentation of sparkling wines. The production of fusel alcohols and their esters as a by-product of the metabolism of individual amino acids during secondary fermentation and the influence of secondary fermentation with the use of individual amino acids as the only source of nitrogen was analyzed. Ten different amino acids were used. We used a control variant with the addition of ammonium hydrogen phosphate as an inorganic source of nitrogen and a control variant with an organic source of nitrogen in the form of an inactivated yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which contained all 20 amino acids in their natural ratio. The higher alcohols investigated were isoamyl alcohol, isobutanol, 2-phenylethanol, 1-propanol, 1-hexanol, and 1-butanol. The following esters of the higher alcohols were subsequently used: isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, phenethyl acetate, and isobutyl acetate. The individual fusel alcohols and esters were analyzed using GC-MS gas chromatography. The results pointed to different amino acid metabolisms in relation to the amount and production of fusel alcohols within the secondary fermentation and thus the sensory profile of sparkling wine.

1. Introduction

In grapes, and therefore must, nitrogen is present in both organic (proteins and amino acids) and inorganic forms (ammonium and ammonium salts). With the exception of proline and hydroxyproline, all amino acids can be metabolized by yeasts under normal winemaking conditions [1].

In addition to their role as amino acids, they play a central role in the overall metabolism. A significant achievement made in research into yeast was the determination of complete metabolic pathways for the use of amino acids as sources of carbon and nitrogen, the biosynthesis of amino acids and the conversion of amino acids to other metabolites including nucleotides. In cells, the catabolic use of sources of nitrogen and the anabolic biosynthetic pathways of amino acids and nucleotides work in parallel. These competing processes must be coordinated so that the cells are able to produce the correct response to nutrient availability [2]. A prerequisite for metabolic coordination is the ability to monitor nutrient concentrations in both the extracellular and intracellular environments [3,4].

In a natural environment, yeast has the ability to use a wide range of nitrogen-containing compounds as the sole source of nitrogen, but not all of them are suitable for the promotion of optimal yeast growth and fermentation activity. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is able to selectively use either organic sources such as amino acids or inorganic sources such as ammonium of nitrogen [5]. This selectivity is achieved through a mechanism of repression of nitrogen catabolites, which is a specific inhibition of the transcription of genes needed for the uptake and degradation of non-preferred nitrogen sources, provided that cells have preferred nitrogen sources available [6,7].

The production of sparkling wines following the traditional method involves a secondary alcoholic fermentation that takes place within the bottle. This is crucial in the production of carbon dioxide and to shape the sensory profile of the wine. This fermentation is initiated by the preparation of the so-called Pied de Cuve, which consists of yeast, most commonly Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sugar as a source of energy, and nutrients containing nitrogen. This step is absolutely essential in the preparation for secondary fermentation, which subsequently takes place in hermetically sealed bottles. An integral part of this is the preparation of the yeast cells for very demanding conditions. Secondary fermentation takes place at a very high pressure, up to 0.8 MPa, at 20 °C, a low temperature, in the presence of ethanol, and in most cases at a low pH. All these affects the production of aromatic metabolites, especially the higher alcohols, esters and volatile acids [8]. An important role in the preparation of Pied de Cuve is played by the nutrients contained in the medium, especially the additives, which help prepare the cell for demanding conditions and at the same time affect the secondary metabolic pathways of alcoholic fermentation. Autolysis of yeast after fermentation also plays an important role, enriching the wine with mannoproteins, amino acids and precursors of taste and aroma [9]. A high pressure (up to 0.8 MPa) in the bottle, ethanol, lower temperature and pH, and low nutrient content create a stressful environment that affects the expression of metabolic and transport genes. During this fermentation, secondary catabolism of amino acids also occurs through the Ehrlich pathway, which leads to the formation of higher alcohols [10] and can also influence the foaming, stability and purity of the final product. Secondary fermentation takes approximately 3–6 weeks with the subsequent maturation typically taking several months to years [11]. Higher alcohols, also known as fusel alcohols, are compounds with more than two carbon atoms. These alcohols are formed by the metabolism of yeast amino acids through the Ehrlich route. Amino acids assimilated through the Ehrlich route include aliphatic or branched-chain amino acids (leucine, valine, and isoleucine) and aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan), along with the amino acid methionine which also contains sulfur. The Ehrlich pathway follows three steps: the initial transamination of an amino acid to its corresponding α-keto acid analog, decarboxylation to aldehyde, and a reduction to the corresponding higher alcohol by alcohol dehydrogenase [12].

Esters are present in wine in the form of both acetate and ethyl esters. They are mainly formed through the metabolism of fatty acid acyl- and acetyl-Coenzyme A (CoA) pathways. Ethyl esters are formed through the esterification of ethanol and acyl-CoA intermediates due to the activity of esterase and transferase enzymes. The second group, acetate esters, are the result of condensation reactions between acetyl-CoA and the higher l alcohols produced by the yeast through amino acid metabolism. Both acetate and ethyl ester esters give different fruit perceptions in wine [13,14].

The anabolic metabolism of amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is essential for cell growth, enzymatic function, and the biosynthesis of structural proteins and regulatory molecules. During alcoholic fermentation, the yeast must either transport amino acids from the external environment or assimilate them de novo using inorganic nitrogen sources or through the deamination of its own available amino acid. The capacity for amino acid biosynthesis depends on the genetic makeup of the yeast, the nitrogen availability, and metabolic status [15,16]. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is able to synthesize all 20 standard amino acids through well-characterized metabolic pathways [17]. These pathways start with the central carbon metabolites from glycolysis and the intermediates of the citrate and pentose pathways such as pyruvate, oxaloacetate and α-ketoglutarate, which act as precursors for various specific amino acids [18]. Enzymatic reactions convert them to amino acids through transamination, carboxylation, hydroxylation and other reactions. The input is typically a carbonaceous skeleton and the nitrogen source is predominantly an ammonium ion (NH4+) from the fermentation medium or from the deamination of another available amino acid [10].

In the synthesis of amino acids such as glutamate and glutamine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, glutamate can be synthesized from the citrate cycle intermediate molecule α-ketoglutarate, and the ammonium ion by the action of NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenases Gdh1 and Gdh3. Gdh1 and Gdh3 are evolutionarily adapted isoforms and cover the anabolic role of the GDH (glutamate dehydrogenase) pathway [19,20].

Previous research has focused primarily on the role of overall nitrogen availability and its utilization during alcoholic fermentation in wine in general, rather than during the secondary fermentation required for traditional-method sparkling wine production. However, only limited data exist on how individual amino acids and different forms of nitrogen influence yeast metabolism during pied de cuve preparation and during the secondary fermentation carried out under the stressful conditions of the traditional method. In particular, there is a lack of studies assessing how distinct nitrogen sources shape the formation of higher alcohols and their esters, which are key precursors contributing to the aromatic complexity of sparkling wines.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of ten individual amino acids, each used as the sole nitrogen source, on the production of higher alcohols and their corresponding esters during secondary fermentation in sparkling wine production and to compare their influence with that of a complex organic nitrogen source (inactivated yeast) and an inorganic source (diammonium phosphate). The novelty of this work lies in the first systematic comparison of individual amino acids under real secondary-fermentation conditions in sparkling wine, enabling a detailed description of the relationship between the availability of specific precursors, yeast metabolism under stress, and the resulting aromatic profile.

2. Materials and Methods

The main objective was a comparison of the effects of individual amino acids on secondary fermentation. For the experiment, 10 amino acids were selected. Each was added individually to a Pied de Cuve giving 10 variants. Secondary fermentation was carried out, during which the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae had a single amino acid as the only source of nitrogen.

2.1. Biological Material

For the experiment, a base wine, a Welschriesling variety, 2022 vintage, was chosen. The harvested grapes came from a vineyard in Mutěnice in South Moravia, the Czech Republic. The area is characterized as warm, dry, mostly with sandy soil. The wine was produced using standard sparkling wine technology; pressing the whole grapes, basic alcoholic fermentation using Saccharomyces cerevisiae, malolactic fermentation, bentonite treatment, stabilization of tartar by freezing and sterile filtration of 0.3 μm.

2.2. Design of the Experiment

The following amino acids were selected: (1) phenylalanine, (2) valine, (3) alanine, (4) serine, (5) glutamic acid, (6) arginine, (7) aspartic acid, (8) leucine, (9) isoleucine, (10) threonine. 10 variants and 2 control samples of Pied de Cuve were prepared as follows:

The IOC 18-2007 (IOC, Épernay, France) yeast strain, that originates from Champagne, was rehydrated for 20 min in water at a temperature of 36 °C and a dose rate of 1 kg of ASVK per 20 L of water. Subsequently, the base wine was added in a 1:1 ratio to the yeast solution and rectified grape must. This increased the glc/fru sugar content to 170 g·L−1, the solution was left for multiplication for 24 h. Subsequently, the base wine was added in a 6.5:1 ratio of wine to the solution from the previous step, plus 10% water, and a single amino acid for each Pied de Cuve. The amount of amino acid was calculated as the molar mass required to increase the pure nitrogen content (YAN) by 181.175 mg·hl−1. In this way, 10 Pied de Cuves that contained a single amino acid were prepared. The first control was prepared with a dose of 3000 mg·hl−1 of hydrogen ammonium phosphate added and the second control had organic nutrient IOC Activit NAT, that contains inactivated yeast, added at a dose rate of 5 g·hl−1 to increase the content of pure nitrogen by 181.175 mg·hl−1, calculated using the molar mass of all the amino acids included.

The doses of the individual amino acids for the Pied de Cuve variants were as follows:

The doses of individual amino acids (mg·hl−1 ) are summarized in Table 1.The base wine was treated to achieve a residual sugar content of 25.4 g·L−1 glc/fru using rectified grape must and a shaking product was added.

Table 1.

Doses of individual amino acids in mg·hl−1.

Each variant of Pied de Cuve, containing only one amino acid, was separately bottled with the base wine in 0.75 L bottles, where secondary fermentation took place as per the traditional bottle fermentation method, at a temperature of 13 °C. Along with this, controls containing an inorganic source of nitrogen and an organic source of nitrogen were also bottled.

Samples for analysis were taken after 3 days, 7 days, 14 days and 50 days of secondary fermentation, always as three repeating variants. Secondary fermentation was complete after 50 days in all samples; all fermentable sugars had been metabolized

Subsequently, the content of the following individual higher alcohols was measured: isoamyl alcohol, isobutanol, 2-phenylethanol, 1-propanol, 1-hexanol, 1-butanol, and their esters isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, phenethyl acetate, isobutyl acetate by GC-MS gas chromatography.

2.3. Determination of Esters and Fusel Alcohol by GC-MS

Esters and fusel alcohol were analyzed using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) after liquid–liquid extraction using methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) containing 10% hexane. Internal standard 2-nonanol (400 mg·L−1) was added to 20 mL of the wine/must sample, along with 5 mL of saturated ammonium sulfate solution. After mixing and phase separation, the extract was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate and analyzed. Separation was performed on a DB-WAX column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm), with a polyethylene glycol stationary phase. Helium was used as the carrier gas at 1 mL·min−1. The temperature program started at 45 °C and increased linearly to 250 °C, where it was held for 6.5 min. Detection took place in SCAN mode (14–264 m/z), with a 0.25 s data collection interval. Compounds were identified by comparing spectra and retention times with the NIST 107 database. Analysis was performed using a Shimadzu GC-17A chromatography system with an AOC-5000 autosampler and QP-5050A quadrupole detector, and the data were processed using GCsolution software (version 1.20).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using three biological replicates for each treatment. For each replicate, an independent bottle undergoing secondary fermentation was sampled and analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed in Statistica 14. Normality and homoscedasticity were verified prior to ANOVA using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. Differences between treatments were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test at a significance level of α = 0.05.

3. Results

The results of the chemical analysis performed by GC-MS gas chromatography are divided into 4 graphs. In the graphs, the individual variants of the amino acids are always divided into vertical bars showing the profile of the analyzed parameters. Each amino acid was analyzed after 3, 7, 14 and 50 days, which is indicated in the graph by the development curve for each amino acid. The bottom axis shows the day of collection. On the horizontal axis the amount of the substance under investigation is shown, along with the development over time and the measured concentration.

Comparison of the Content of Higher Alcohols

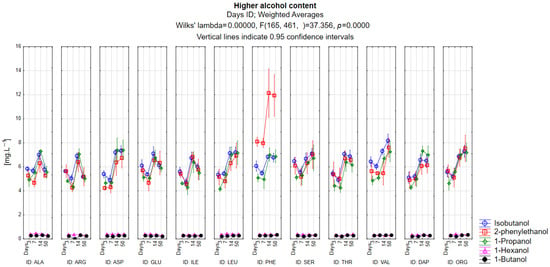

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the higher alcohol contents for isobutanol, 2-phenylethanol, 1-propanol, 1-hexanol, and 1-butanol in the secondary fermentation of sparkling wine. Isoamyl alcohol is not listed as it was found in concentrations of around 100–150 mg·L−1 in the wine. It is clear from the graph that higher alcohols such as 1-hexanol and 1-butanol found in wine were at very low concentration levels up to a maximum of 0.5 mg·L−1. Their development is therefore negligible in terms of a source of nitrogen for fermentation. The highest level of production of isobutanol was shown in the variant containing the amino acid valine, at a concentration of 8.43 mg·L−1. Valine is a direct precursor to isobutanol. This increase was statistically significant when compared with all other amino acid treatments and both nitrogen controls (p < 0.05). Of interest is the greatly increased concentration of 2-phenylethanol in the variant with the amino acid phenylalanine. Phenylalanine is a direct precursor to 2-phenylethanol, but the concentration of 2-phenylethanol is almost double that of other higher alcohols, even when other amino acids are used as a source of precursors. The phenylalanine treatment differed significantly from all other variants (p < 0.05), confirming its strong precursor-driven effect. The precursor for the higher alcohol 1-propanol is the amino acid threonine, but this variant does not show an increased concentration of the higher alcohol 1-propanol. On the contrary, it was most abundant in the variants with aspartic acid, leucine, serine, and controls that contained all the amino acids. However, the LSD test shows that only a few pairs (e.g., asparagin–valin or leucin–ogranic nutrition) did not differ significantly, while most other combinations were statistically different (p < 0.05), indicating that 1-propanol formation responded variably to different nitrogen sources. Overall, a higher proportion of higher alcohols were found in the variants that used organic sources of nutrition, valine and leucine, while the lowest levels were found in the variants with alanine and arginine.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the higher alcohol content.

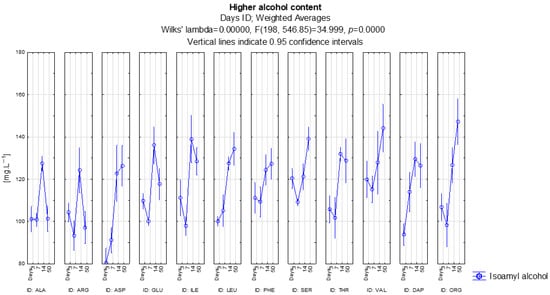

Figure 2 shows the development of isoamyl alcohol content in the individual variants. The direct precursor for this higher alcohol is the amino acid leucine, yet there is a de novo pathway from pyruvate to α-ketoisocapronate and then as per the leucine pathway. However, the highest concentration was not only measured with the use of leucine, but also in the variant with organic nutrition from all the amino acids, with a concentration of 147 mg·L−1. This is logical, because yeast metabolism is complex and only leucine as a sole nitrogen source will inhibit other metabolic processes. According to the LSD test, the organic nitrogen variant produced significantly higher isoamyl alcohol than leucine (p = 0.00014), meaning the two variants do not form a statistically comparable group. Only leucine as a nitrogen source has an increasing tendency for the formation of isoamyl alcohol with the development of alcoholic fermentation. Leucine showed significantly higher isoamyl alcohol levels than alanine, arginine, glutamic acid, serine and threonine (all p < 0.05), confirming its strong precursor-driven effect. The second highest concentration was found in the valine variant, at 144 mg·L−1. Valine did not differ significantly from the organic nitrogen source (p = 0.28070), but was significantly higher than most other amino acid treatments, including arginine, alanine and threonine (all p < 0.05). On the other hand, the lowest concentration was found in the arginine variant at 97 mg·L−1. Arginine showed significantly lower isoamyl alcohol production than all other treatments except alanine (p = 0.15746), confirming it as the weakest nitrogen source for isoamyl alcohol synthesis. The development of isoamyl alcohol in the alanine, arginine and glutamic acid variants is interesting, the concentration in the sample increased after 14 days and then on the 50th day, when the alcoholic fermentation was complete, it dropped to almost the same level as at the beginning. These temporal changes were not statistically significant (all p ≥ 0.05), suggesting that the fluctuations reflect natural variability rather than consistent treatment effects.

Figure 2.

Isoamyl alcohol content for individual variants.

Higher alcohols are initially produced through yeast catabolism of amino acids via the Ehrlich pathway, together with the anabolic formation from pyruvate during the early stages of secondary fermentation. Their concentrations therefore rise as long as precursors are available and yeast metabolism remains active. The slight decrease in some higher fusel alcohols at the end of secondary fermentation can be primarily due to their adsorption onto yeast lees during autolysis and to their conversion into acetate esters, rather than any metabolic re-utilization. Since the Ehrlich pathway is irreversible, these physical and biochemical interactions best explain the observed decline.

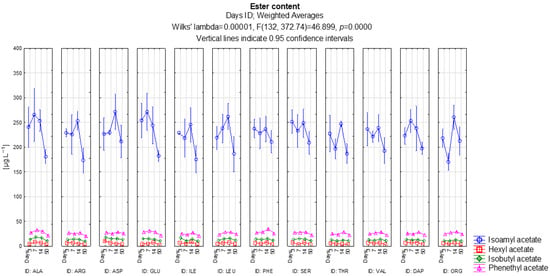

Figure 3 shows how the ester content of the higher alcohols such as isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, isobutyl acetate, and phenethyl acetate develops. On this graph we will focus on the production of isoamyl acetate as its concentration is several times higher than the other esters of higher alcohols. The highest concentrations were measured in the variants with aspartic acid, phenylalanine, serine and organic nutrients containing all amino acids. According to the LSD test, these four treatments displayed significantly higher isoamyl acetate levels than alanine, arginine, glutamic acid, isoleucine, leucine and valine (all p < 0.05). The lowest concentrations were found in the alanine, arginine, glutamic acid, isoleucine, and leucine variants. These variants formed a statistically homogeneous group, as none of the pairwise comparisons within this set were significant (p ≥ 0.05). Overall, it is clear from the graph that isoamyl acetate production reached a peak after 14 days of alcoholic fermentation and subsequently declined. This temporal pattern was consistent across all treatments and did not result in statistically significant differences between time points within individual variants (p ≥ 0.05). An association with the isoamyl alcohol content, from which this ester is formed, has not been confirmed. The highest isoamyl alcohol content was found in the variant with organic nutrients and all amino acids and the valine variant. However, both treatments showed only moderate isoamyl acetate concentrations, and neither differed significantly from the median-performing variants in isoamyl acetate formation (p ≥ 0.05). Valine, however, exhibited an average isoamyl acetate content. This indicates that isoamyl acetate formation is not directly proportional to isoamyl alcohol levels and is more strongly influenced by the activity of alcohol acetyltransferases rather than precursor abundance.

Figure 3.

Development of ester content of the analyzed higher alcohols.

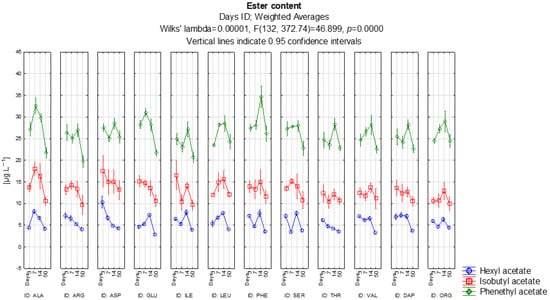

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the ester content of the higher alcohols, excluding isoamyl acetate. We will focus on the production of hexyl acetate, isobutyl acetate, phenethyl acetate. The highest content found was for phenethyl acetate, an ester of the higher l alcohol 2-phenylethanol and acetic acid. In the wine, it manifests as a flowery aroma. The highest concentrations were measured in the variants with aspartic acid and phenylalanine. According to the LSD test, both the aspartic acid and phenylalanine treatments produced significantly higher phenethyl acetate levels than alanine, arginine, glutamic acid, isoleucine, leucine, threonine, valine and DAP (all p < 0.05). The variant with the highest content of 2-phenylethanol came from the addition of the amino acid phenylalanine, and this treatment also showed significantly elevated phenethyl acetate compared with nearly all other nitrogen sources (p < 0.05), except organic nitrogen where the difference was not significant (p = 0.653). After 14 days of alcoholic fermentation the highest concentration of the ester found in all variants was 34.6 μg L−1. The lowest concentration was found in the arginine variant. Arginine displayed significantly lower phenethyl acetate levels than every other treatment except alanine (p ≥ 0.05), forming the lowest-producing group. The level of isobutyl acetate was highest in the aspartic acid variant and lowest in the arginine variant. The LSD test confirmed that aspartic acid produced significantly higher isobutyl acetate than alanine, arginine, glutamic acid, threonine, valine and DAP (all p < 0.05). Arginine showed the lowest levels and differed significantly from most other treatments (p < 0.05), again confirming its weak ester-forming capacity. Hexyl acetate showed very similar levels in all variants, with the exception of aspartic acid, where the highest concentration was on the 3rd day of fermentation. Statistically, the aspartic acid treatment produced significantly more hexyl acetate than alanine, arginine, isoleucine, leucine, serine, threonine, valine, DAP and organic nitrogen (all p < 0.05). In contrast, hexyl acetate levels among alanine, arginine, isoleucine, leucine, serine, threonine and valine did not differ significantly from each other (p ≥ 0.05), forming a homogeneous low-production group. The concentration of all esters of higher alcohols tend to decrease over the course of alcoholic fermentation, measured after 50 days. These declines were not statistically significant within individual variants (p ≥ 0.05), indicating natural degradation processes rather than treatment-specific effects.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the ester content of the analyzed higher alcohols.

The concentration of esters in the wine is unstable over time and they often break down, in sparkling wine they are more intense due to the ongoing autolysis of the yeast in the bottle. Volatile esters may decrease during maturation on lees, primarily due to instability, chemical hydrolysis, or yeast lees absorbing esters [8].

The following tables show the output from Statistica, specifically from an LSD (Least Significant Difference) test. The tables show the p-values between the groups. If the p-value is <0.05, the difference between the groups is statistically significant and is shown in red in the table. PC (Mean Square) is an error estimate from ANOVA (Mean Square Error), which is used to calculate differences between groups, and SV (degrees of freedom). In the LSD test, these values are used to assess whether the difference between the averages of the groups is statistically significant.

In the case of isoamyl alcohol, as we can see in Table 2, it is clear that most amino acids have a significantly different effect on its production, as the majority of the comparisons shows very low p-values. However, some combinations behave similarly, for example, PHE50 and ILE50 or SER50 and DAP50, where the differences were not statistically significant. The most markedly different profiles can be observed with ASP50 or GLU50, which are different from almost all the others. Overall, isoamyl-alcohol shows strong diversity in the effects of individual amino acids, with a few exceptions where the effects overlap.

Table 2.

LSD test for Isoamyl alcohol.

Table 3 shows which variants produce a statistically significant difference in isobutanol production. Most of the differences are highly significant. Only a few combinations (e.g., ASP50 vs. {8}, LEU50 vs. {8}, ORG50 vs. some groups) are not conclusive. This suggests that amino acid supplements (ALA, ARG, GLU, etc.) result in variations in isobutanol production, but some of them behave similarly. In ALA50 ({1}) in comparison to most other variables, the p-values are extremely low (0.000000, 0.000027, etc.); thus, ALA50 significantly differs from almost all groups. The situation is similar with ARG50 ({2}, almost all pairs produce significant differences. On the other hand, for some combinations (e.g., LEU50 vs. {8}, p = 0.508754) the difference is not significant. Some amino acids fundamentally alter the production of isobutanol (ALA, ARG, VAL), while others behave in a similar way and the differences between them are not significant (ASP, LEU, PHE, ORG, partially SER/THR).

Table 3.

LSD test for Isobutanol.

The results in Table 4 for the LSD test for 2-phenylethanol show that some amino acids clearly have a different effect on its production, especially PHE50 and VAL50, which are statistically significantly different from all other variants. Similarly, they form a separate pair with ALA50 and ARG50, where no differences between them are found, but they differ from the rest of the group. Most other amino acids (ASP, GLU, ILE, LEU, SER, THR, ORG and DAP) are grouped into a wide cluster where they do not demonstrate any significant differences between them, while closer similarity is evident, for example, in the ORG–DAP pair and the ASP–LEU–SER–THR group. Overall, the analysis indicates the existence of three main groups of amino acids that have different effects on the formation of 2-phenylethanol.

Table 4.

LSD test for 2-phenylethanol.

Table 5 shows the results of the LSD test for 1-propanol. We can see that most amino acids cause statistically significantly differences in production, as the p-values are very low in most cases. However, several variants behave in a similar way, for example, ILE50 and GLU50 show no differences (p ≈ 0.089), along with LEU50 and ORG50 (p ≈ 0.91). Similarities can also be observed between some pairs within a larger group, but otherwise most of the amino acids are clearly distinguished. Overall, the analysis suggests that for 1-propanol, the differences between variants are significant, with only a few combinations (ILE-GLU, LEU-ORG) being exceptions.

Table 5.

LSD test for 1-propanol.

Table 6 shows the results of the LSD test for 1-hexanol where we can see that almost all the amino acids significantly differ from each other, since most of the p-values are well below 0.05. Only a few pairs show no differences, for example, ALA50 and SER50 (p ≈ 0.98) or GLU50 and ILE50 (p ≈ 0.28), suggesting a similar effect. Similarities also appear between some other combinations (e.g., LEU50–THR50, SER50–ORG50), but overall significant differences prevail. Thus, with 1-hexanol, most amino acids have a different effect, with only a limited number of pairs forming identical or close groups.

Table 6.

LSD test for 1-hexanol.

Table 7 shows the results of the LSD test for 1-butanol. We can see that most amino acids differ significantly from each other, since most of the p-values are statistically significant. However, some variants are similar, for example, ALA50 and ARG50 (p ≈ 0.72) or LEU50 and ASP50 (p ≈ 0.89) which show no differences. The ILE50 and LEU50 (p ≈ 0.29) pair also show a similarity, while variants such as GLU50, PHE50 or VAL50 differ from almost all others. Overall, most amino acids have a different effect on the formation of 1-butanol, with only a few pairs being similar.

Table 7.

LSD test for 1-butanol.

Table 8 shows the results of the LSD test for isoamyl acetate where we can see that there are significant differences between many amino acids, but at the same time there are groups with similar effects. For example, PHE50 and ARG50 (p ≈ 0.97) or LEU50 and THR50 (p ≈ 0.98) are very similar, suggesting that these amino acids affect the formation of isoamyl acetate in a similar way. On the other hand, combinations such as ALA50, ASP50 or GLU50 significantly differ from almost all other variants. Overall, the results show the existence of both clearly defined groups and several narrow pairs of amino acids with comparable effects.

Table 8.

LSD test for isoamyl acetate.

The results of the LSD test for hexyl acetate, shown in Table 9 demonstrate that there are statistically significant differences between most of the amino acids, which indicates that they have different effects on the production of this ester. However, several combinations are similar, for example, ARG50 and LEU50 (p ≈ 0.65) or PHE50 and THR50 (p ≈ 0.94), which do not differ from each other. In particular, the variants of GLU50, SER50 and ORG50 are significantly different and are different from almost all other groups. Overall, the results suggest that while most amino acids have different effects on the formation of hexyl acetate, there are also a few narrow pairs that have similar effects.

Table 9.

LSD test for hexyl acetate.

Table 10 shows the results for phenethyl acetate which suggests that the differences between most of the amino acids are highly pronounced, indicating that they have specific effects on the production of this ester. However, several combinations produced no significant differences, typically ALA50 and GLU50 (p ≈ 0.98) or LEU50 and ORG50 (p ≈ 0.65), which can be considered to be similar. On the other hand, variants such as ASP50, ARG50 or SER50, which differ statistically significantly from most of the other groups, demonstrated significant differences. Overall, the results show that phenethyl acetate is strongly differentiated according to the amino acid present, with only a small number of pairs exhibiting similar behavior.

Table 10.

LSD test for phenethyl acetate.

In the case of isobutyl acetate, as shown in Table 11 it is evident that the differences between the individual amino acids are not as clear as those found with other substances, statistically insignificant values appear for a number of combinations. For example, ALA50 and GLU50 or ARG50 and ILE50 behave in a similar way, where the differences were not confirmed statistically. On the contrary, variants such as ASP50, PHE50 and SER50 are clearly different from most other variants and demonstrate a specific effect on the production of this ester. Overall, the test shows that while some amino acids have a very similar effect, others significantly stand out and form separate profiles.

Table 11.

LSD test for isobutyl acetate.

The following Table 12 shows the final concentrations of higher alcohols at the end of secondary fermentation for the sampling variant on day 50. The results indicate that the composition of the nitrogen source significantly affected the concentrations of all monitored higher alcohols. The highest levels of most higher alcohols were observed in variants VAL50, ORG50 and SER50, whereas variant ARG50 generally exhibited the lowest concentrations. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Differences in the concentrations of individual higher alcohols between variants (ID) were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an LSD post hoc test. Different letters within a column indicate statistically significant differences at p < 0.05.

Table 12.

ANOVA followed by an LSD post hoc test for higher alcohol in mg·L−1. Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differences among samples.

The Table 13 shows the final concentrations of acetate esters at the end of secondary fermentation for the sampling variant on day 50. The results indicate that the composition of the nitrogen source markedly affected the levels of all monitored esters: isoamyl acetate reached the highest values in variants ASP50, PHE50 and ORG50, while hexyl acetate was most abundant in ORG50, ASP50 and ALA50 and lowest in GLU50 and VAL50. Phenethyl acetate was particularly enhanced in PHE50, ORG50 and LEU50, whereas variants ARG50 and ILE50 generally exhibited the lowest concentrations of the measured esters. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Differences in the concentrations of individual esters between variants (ID) were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an LSD post hoc test. Different letters within a column indicate statistically significant differences at p < 0.05.

Table 13.

ANOVA followed by an LSD post hoc test for esters in μg L−1. Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differences among samples.

4. Discussion

The synthesis of higher alcohols generally takes place through the metabolism of amino acids via the Ehrlich pathway in the mitochondria and cytoplasm or through the anabolic pathway from glucose via pyruvate. Both synthetic pathways converge to form α-keto acid, which can be decarboxylated and reduced to form a higher alcohol. The Ehrlich pathway directly includes the amino acids leucine, valine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan. The formation of these alcohols therefore depends on the concentration of nitrogen and amino acids. The metabolic network involved in the production of these compounds during still wine fermentation has been well studied, but less so during secondary fermentation in sealed bottles for sparkling wine production [21].

Cordente et al. [12] analyzed the levels of higher alcohols and their effect on wine of the Chardonnay variety. They state that the higher alcohols, 2-phenylethanol, tryptophol, and tyrosol, affect the aroma and taste of fermented beverages Zhu et al. [22]. The content of 2-phenylethanol in our experiment was significantly higher when the amino acid phenylalanine was used as its precursor. Among other things, this higher alcohol has a flowery aroma, as stated by Qu et al. [23] and Tsai et al. [24] They even state that higher alce 2-phenylethanol, which is derived from phenylalanine, is associated with a rose-like scent. 2-phenylethanol is naturally present in grapes in undetectable concentration; however, some strains of yeast can increase the production of 2-phenylethanol by increasing the production of its precursor, phenylalanine. We can confirm this hypothesis. Blanco et al. [25] examined the effect of higher alcohols on the aroma of red wine. They state that the influence of isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol confirms their sensory importance in the perception of the aroma of wine, with methionol and 2-phenylethanol having a negligible effect.

In the results of the work by Vidal et al. [26] it is demonstrated that the production of isoamyl alcohol is mainly dependent on the availability of oxygen in the medium, and mainly depends on the amount of leucine and α-keto-acids. These conclusions, however, were obtained under conditions of primary fermentation with greater oxygen accessibility and without CO2. We cannot confirm this hypothesis, as the highest level of isoamyl alcohol was found in the variants with all amino acids and with valine. This indicates that, under the highly reductive and pressurized-stressful conditions of secondary fermentation, other metabolic factors override the simple precursor–product relationship described for primary fermentation. It also mentions the unclaimed accumulation of isobutanol, active amyl alcohol and 2-phenylethanol. However, it is also reported for carbon depletion of metabolizing isoamyl alcohol, isobutanol, and active amyl alcohol, for cell maintenance. This may be the reason behind the reduction in the levels of some higher alcohols during our experiment, especially in the ammonium variant as a source of nitrogen or arginine.

González-Jiménez et al. [27] investigated the effect of ester metabolism and CO2 overpressure on the organoleptic properties of sparkling wines. They state that the pressure did not have a significant effect on the production of the investigated esters such as ethyl propanoate, ethyl isobutanoate, isobutyl acetate, ethyl 2-methyl butanoate, ethyl 3-methyl butanoate, isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, ethyl heptanoate, phenylethyl acetate, ethyl octanoate, ethyl 2-methyl octanoate, and ethyl decanoate. Therefore, we can assume that the resulting CO2 overpressure in sparkling wine does not affect the aromatic properties of sparkling wine in terms of the production of higher alcohols and esters.

Nascimento et al. [28] investigated the profile of volatile aromatic compounds such as butane-1,3-diol, 2,3-butanediol, 2-phenylethyl acetate, isoamyl acetate, and hexyl acetate in sparkling wines made from the Chenin blanc and Syrah varieties. Both Chenin blanc and Syrah showed significant aromatic descriptors. Since both varieties contain different concentrations of individual amino acids in the must, we can assume that the composition and ratios of amino acids affect the production of higher alcohols and esters, as has been shown in our case. Their work illustrates that even relatively small differences in the amino-acid composition of the must can lead to distinct aromatic outcomes during alcohol fermentation. This observation is directly relevant to our results, as it supports the notion that yeast metabolism during sparkling-wine production is highly sensitive to the specific amino-acid environment. While Nascimento et al. [28] studied natural differences between grape varieties, our experiment extends this concept by isolating the effect of individual amino acids used as the sole nitrogen source, thus confirming that the precursor profile fundamentally shapes the production of higher alcohols and their esters.

Cotea et al. [29] focused on the production of volatile aromatic compounds in sparkling wine from the point of view of the yeast strain. They found significant levels of esters such as ethyl octanoate and ethyl decanoate. However, esters such as isoamyl acetate, ethyl palmitate, 4-acetanol and 1-heptanol did not make a great a contribution to the aromatic profile of the individual variants in their experiment. In our experiments, the ester content of higher alcohols differed from variant to variant, yet their levels decreased as the wine matured on the lees. Ubeda et al. [30] came to the same conclusion, they state that during secondary fermentation and subsequent maturation, there is a significant loss of esters, which is related to a reduction in the proportion of fragrances related to fruit aromas. This loss can be caused as they are adsorbed into the sludge, but also through chemical hydrolysis due to their thermodynamic instability. The agreement between our results and these studies suggests that ester degradation during maturation is a dominant process irrespective of the initial precursor availability, while the differences observed between our nitrogen variants likely arise from the distinct metabolic pathways activated during the early stages of secondary fermentation.

Overall, the results show a variability in the levels of higher alcohols and their esters during alcoholic fermentation and secondary alcoholic fermentation. According to the available sources, their content is influenced by, among other things, the variety, fermentation conditions, and the total content and source of nitrogen. Individual higher alcohols have a positive or negative effect on the resulting aroma of the wine, depending on their concentration. Their production may also indirectly depend on the ester content of higher alcohols, although our study did not confirm this hypothesis. However, statistically significant differences in the content of individual substances analyzed can be found in variants that contain different amino acids as a source of carbon. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that yeast metabolism during secondary fermentation is highly dynamic and strongly shaped by the specific nitrogen source provided. While previous studies have shown that varietal composition, fermentation environment and total YAN affect the formation of higher alcohols and esters, our results extend this understanding by revealing that individual amino acids used as the sole nitrogen source lead to distinct and statistically significant metabolic profiles. This confirms that precursor availability at the level of single amino acids represents a key regulatory factor influencing both alcohol and ester biosynthesis under the restrictive conditions of secondary fermentation. The absence of a direct correlation between higher alcohols and their corresponding esters in our experiment further suggests that ester formation is modulated not only by precursor concentration but also by enzymatic activity and subsequent degradation during lees aging.

It is important to note that the studies referenced in this discussion address only related aspects of nitrogen metabolism, as no research to date has examined the behavior of yeast supplied with individual amino acids as the sole nitrogen source during secondary fermentation under CO2 overpressure. For this reason, the available literature cannot be directly confronted with our findings; instead, it provides a mechanistic framework derived mainly from primary fermentations or experiments using complex nitrogen sources. The patterns observed in our results therefore extend existing knowledge into a technological context that has not previously been experimentally explored.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that individual amino acids used as the sole nitrogen source during secondary fermentation markedly influence yeast metabolism and the formation of higher alcohols and their corresponding esters. Each amino acid generated a distinct aromatic profile, with statistically significant differences observed across most of the analyzed compounds. The organic complex nitrogen source yielded the highest isoamyl alcohol concentration, while phenylalanine resulted in the greatest production of 2-phenylethanol and its acetate ester.

The results further showed that the formation of higher-alcohol esters cannot be directly inferred from the concentration of the corresponding alcohol, as ester composition is additionally shaped by enzymatic activity and by degradation processes occurring during lees aging. This highlights the complexity of yeast metabolism under the reductive and pressurized conditions of the traditional method, which differs fundamentally from primary fermentation.

The novelty of this work lies in being the first study to experimentally assess individual amino acids as exclusive nitrogen sources during secondary fermentation under CO2 overpressure and stress. No published research has previously addressed this question, and existing literature therefore serves only as a mechanistic reference rather than a basis for direct comparison. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how specific nitrogen precursors regulate the formation and transformation of aroma-active compounds in sparkling wines and offer a potential tool for targeted modulation of sensory profiles in traditional-method production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Š.T. and M.B.; methodology, Š.T., M.B. and K.P.; validation, K.P.; formal analysis, D.M.; resources, M.B.; data curation, Š.T. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Š.T.; writing—review and editing, Š.T. and D.M.; visualization, Š.T. and D.M.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, Š.T.; funding acquisition, Š.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Optimization of secondary fermentation in sparkling wine production from the perspective of yeast nutrition management”, IGA-ZF/2025-SI1-008, financed by Mendel University in Brno.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vilanova, M.; Rodríguez, I.; Canosa, P.; Otero, I.; Gamero, E.; Moreno, D.; Valdés, E. Variability in chemical composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Mencía from different geographic areas and vintages in Ribeira Sacra (NW Spain). Food Chem. 2015, 169, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungdahl, P.O.; Daignan-Fornier, B. Regulation of amino acid, nucleotide, and phosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012, 190, 885–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, D.B.; Stoklosa, R.J. Amino acid uptake by Saccharomyces cerevisiae during ethanol production. Cereal Chem. 2024, 101, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Lippman, S.I.; Zhao, X.; Broach, J.R. How Saccharomyces responds to nutrients. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 27–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, S.J.; van’t Klooster, J.S.; Bianchi, F.; Poolman, B. Growth inhibition by amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.; Mendes-Faia, A.; Mendes-Ferreira, A. The nitrogen source impacts major volatile compounds released by Saccharomyces cerevisiae during alcoholic fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 160, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, R.; Matsushita, T.; Nishimura, A.; Takagi, H. Downregulation of the broad-specificity amino acid permease Agp1 mediated by the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 and the arrestin-like protein Bul1 in yeast. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.S.; Campos, F.; Cabrita, M.J.; da Silva, M.G. Exploring the aroma profile of traditional sparkling wines: A review on yeast selection in second fermentation, aging, closures, and analytical strategies. Molecules 2025, 30, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigentini, I.; Cardenas, S.; Valdetara, F.; Faccincani, M.; Panont, C.; Picozzi, C.; Foschino, R. Use of native yeast strains for in-bottle fermentation to face the uniformity in sparkling wine production. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; van’t Klooster, J.S.; Ruiz, S.J.; Poolman, B. Regulation of amino acid transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, e00024-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, M.; Seeley, P.; Barocci, E.; Milanowski, T.; Mayr-Marangon, C.; Ricci, A.; Parpinello, G.P. Effect of interspecific yeast hybrids for secondary in-bottle alcoholic fermentation of English sparkling wines. Foods 2023, 12, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordente, A.G.; Espinasse-Nandorfy, D.; Solomon, M.; Schulkin, A.; Kolouchova, R.; Francis, I.L.; Schmidt, S.A. Aromatic higher alcohols in wine: Implication on aroma and palate attributes during Chardonnay aging. Molecules 2021, 26, 4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Průšová, B.; Humaj, J.; Sochor, J.; Baron, M. Formation, losses, preservation and recovery of aroma compounds in the winemaking process. Fermentation 2022, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, D.; Wacker, M.; Schmarr, H.-G.; Fischer, U. Understanding the contribution of co-fermenting non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces yeasts to aroma precursor degradation and formation of sensory profiles in wine using a model system. Fermentation 2023, 9, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnebusch, A.G. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 59, 407–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, D.; Jaehde, I.; Guillamón, J.M.; Heras, J.M.; Querol, A. Screening of Saccharomyces strains for the capacity to produce desirable fermentative compounds under the influence of different nitrogen sources in synthetic wine fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2021, 97, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, H.; Shao, J.; Zeng, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. A comprehensive review and comparison of L-tryptophan biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1261832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hoppe, T. Role of amino acid metabolism in mitochondrial homeostasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, P.; Fragiadakis, G.; Gkountromichos, F.; Alexandraki, D. The pleiotropic effects of the glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Factories 2018, 17, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.J.; Marsikova, J.; Vachova, L.; Palkova, Z.; Cooper, T.G. Effects of abolishing Whi2 on the proteome and nitrogen catabolite repression-sensitive protein production. G3 2022, 12, jkab432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Jiménez, M.C.; Mauricio, J.C.; Moreno-García, J.; Puig-Pujol, A.; Moreno, J.; García-Martínez, T. Endogenous CO2 overpressure effect on higher alcohols metabolism during sparkling wine production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Bai, X.; Xiong, S.; Guan, X.; Li, A.; Tao, Y. Predictive modeling of wine fruity ester production based on nitrogen profiles of initial juice. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; He, S.; Tao, Y.; Jin, G. Esters and higher alcohols regulation to enhance wine fruity aroma based on oxidation–reduction potential. LWT 2024, 200, 116165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-C.; Araujo, L.D.; Tian, B. Varietal aromas of Sauvignon blanc: Impact of oxidation and antioxidants used in winemaking. Fermentation 2022, 8, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Fuente-Blanco, A.; Sáenz-Navajas, M.-P.; Ferreira, V. On the effects of higher alcohols on red wine aroma. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa Vidal, E.; de Morais Jr, M.A.; François, J.M.; de Billerbeck, G.M. Biosynthesis of higher alcohol flavour compounds by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Impact of oxygen availability and responses to glucose pulse in minimal growth medium with leucine as sole nitrogen source. Yeast 2015, 32, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Jiménez, M.C.; Moreno-García, J.; García-Martínez, T.; Moreno, J.J.; Puig-Pujol, A.; Capdevilla, F.; Mauricio, J.C. Differential analysis of proteins involved in ester metabolism in two Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains during the second fermentation in sparkling wine elaboration. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Nascimento, A.; de Souza, J.; dos Santos Lima, M.; Pereira, G. Volatile profiles of sparkling wines produced by the traditional method from a semi-arid region. Beverages 2018, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotea, V.V.; Focea, M.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Colibaba, L.C.; Scutarașu, E.C.; Marius, N.; Popîrdă, A. Influence of different commercial yeasts on volatile fraction of sparkling wines. Foods 2021, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubeda, C.; Kania-Zelada, I.; del Barrio-Galán, R.; Medel-Marabolí, M.; Gil, M.; Peña-Neira, Á. Study of the changes in volatile compounds, aroma and sensory attributes during the production process of sparkling wine by traditional method. Food Research International 2019, 119, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.