Abstract

Sustainable production of high-quality chitosan from agro-industrial by-products remains a challenge in biotechnology. This study aimed to improve chitosan production from fermented rice bran and rice husk using Rhizopus oryzae in solid-state fermentation (SSF), and evaluated the physicochemical and biological properties of the resulting biopolymer. A full factorial design (23) was applied to assess key fermentation parameters, including moisture content, substrate composition, and nitrogen supplementation. Among the tested conditions, the highest chitosan yield was at 55% moisture, 50% rice husk, and 1.8 g/L urea. The obtained chitosan was characterized for degree of deacetylation (DD) using FTIR and NMR, and molecular weight (MW) by viscometry. Antimicrobial activity was tested against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and antioxidant capacity was measured via DPPH and ABTS assays. The chitosan exhibited a high DD (86.4 ± 0.6%) and a MW of 59.65 kDa, values comparable to commercial standards. It showed strong antimicrobial activity, particularly against Gram-negative strains. Antioxidant assays confirmed concentration-dependent activity, reaching 94% DPPH inhibition at 5.00 mg mL−1. Overall, the results demonstrate that agro-industrial residues can be effectively transformed into high-quality, bioactive chitosan, offering a sustainable and circular alternative to conventional production routes.

1. Introduction

Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature, occurring in the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects and in the cell walls of many filamentous fungi [1]. Its derivative, chitosan, obtained through partial deacetylation, is a reactive, polycationic biopolymer with recognized antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitumor, and antidiabetic activities [2,3,4]. Owing to these functional properties, chitosan has broad applications in biomedical, pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic sectors.

Commercial chitosan is traditionally produced by chemically deacetylating chitin isolated from crustacean shells. Although effective, this process is environmentally intensive, generating large volumes of alkaline effluents, consuming substantial freshwater, and often producing chitosan with inconsistent molecular weight and degree of deacetylation (DD) [5]. These drawbacks highlight the need for alternative, sustainable, and more controlled production strategies.

Biotechnological approaches have gained increasing attention as a means to overcome these limitations [6]. While insects and other organisms have been proposed as alternative chitin sources, their processing generally relies on thermochemical steps that reproduce similar environmental impacts [7]. Therefore, the development of environmentally friendly bioprocesses aligned with circular economy principles remains a priority.

Solid-state fermentation (SSF) is a promising approach for valorizing agro-industrial residues while reducing wastewater generation [2,8]. SSF efficiency depends on factors such as fungal strain, substrate composition, and moisture content, which directly influence product yield and quality [9]. Mucorales fungi are particularly attractive for chitosan production because chitosan is an intrinsic component of their cell walls. Consequently, extraction requires fewer processing steps than conventional chitin deacetylation [10]. Within this group, Rhizopus oryzae, a GRAS-certified species, is industrially relevant due to its metabolic versatility and capacity to utilize diverse carbon sources [11].

In addition to maximizing yield, rigorous physicochemical characterization is essential to establish the functional quality of chitosan. The degree of deacetylation strongly influences solubility, charge density, and biological activity, directly affecting antimicrobial interactions and free radical scavenging capacity [2,3]. Thus, linking fermentation parameters to the resulting DD and bioactivity is critical for validating novel production routes.

Studies have investigated solid-state fermentation (SSF) conditions for chitosan production by Rhizopus species using agro-industrial substrates [12,13]. In parallel, the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of fungal chitosan obtained from different sources and cultivation systems have been reported [14,15]. However, studies combining SSF using rice-based residues with a comprehensive characterization of chitosan bioactivity remain scarce.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate chitosan production by SSF of rice bran and rice husk using Rhizopus oryzae. A full factorial design (23) with replicated central points was applied to evaluate the combined effects of moisture content, substrate proportion, and urea supplementation on chitosan yield. Instead of response surface optimization, the design was used as a screening approach to identify the conditions that resulted in the highest chitosan yield. The recovered biopolymer was further characterized in terms of its structural, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, highlighting the potential of agro-residue-based SSF as a sustainable strategy for producing high-value functional biopolymers within a circular bioeconomy framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Substrate Preparation

Rhizopus oryzae was obtained from the microbial collection of Fundação André Tosello and maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Kasvi, Pinhais, Brazil) at 30 °C, with monthly subculturing. Rice bran and rice husk were collected from local mills and milled (Solab, Piracicaba, Brazil) to a particle size of 0.5 mm.

2.2. Solid-State Fermentation (SSF)

SSF was carried out in tray-type bioreactors (measuring 4 cm in height, 7.5 cm in width, and 12.8 cm in length), that were conditioned in a bacteriological culture oven (Quimis, Diadema, Brazil) to control the temperature and the moisture (by the addition of sterile water into Petri dishes). Substrate (rice bran and husk) was sterilized in an autoclave (Labcomm, Piracicaba, Brazil) at 121 °C for 15 min, cooled to room temperature, supplemented with nutrient solution (2 g L−1 KH2PO4; 1 g L−1 MgSO4 and NH2CONH2), homogenized in distilled water, and inoculated with R. oryzae at 4 × 106 spores g−1. The substrate layer had a thickness of 2 cm and it was incubated at 30 °C for 48 h [16,17].

A full factorial design (23) with three replicates at the central point was used to evaluate the effect of moisture content, rice husk proportion, and urea concentration (Table 1). After fermentation, samples were stored at −18 °C. Chitosan yield (Equation (1)) was used as the response variable.

2.3. Chitosan Extraction and Purification

Chitosan was extracted by autoclaving the fermented biomass at 121 °C for 15 min in 1 mol L−1 sodium hydroxide at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:40 (w/v). The alkali-insoluble fraction was thoroughly washed with distilled water and refluxed with 100 volumes of 2% (v/v) acetic acid at 95 °C for 24 h. The resulting suspension was centrifuged (Cientec, São Paulo, Brazil), and the supernatant was adjusted to pH 10 using NaOH to precipitate chitosan. The extracted chitosan was then purified by successive washing with chilled water, ethanol, and acetone, and dried in a forced-air oven (Tecnal, Piracicaba, Brazil) at 50 °C until reaching commercial moisture content, according to [18].

2.4. Chitosan Characterization

Polymer identification and determination of the degree of deacetylation (%DD) were performed by hydrogen (H1) Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, in partnership with the Integrated Analysis Center (CIA-FURG), according to Lavertu et al. [19]. FTIR analysis was performed using chitosan/KBr pellets (1:20, w/w) on an IR Prestige-21 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan), with spectra acquired from 4000 to 800 cm−1 at 4 cm−1 resolution (40 scans). The protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl method for nitrogen determination [20].

The intrinsic viscosity (η) of chitosan was obtained using a Cannon–Fenske capillary viscometer (GMBH—D65719, Hofheim am Taunus, Germany), according to the method described by Zhang and Neau [21]. Subsequently, the average molar mass was determined using the classical Mark–Houwink equation (Equation (2)), where η is the intrinsic viscosity (mL g−1), MM is the molar mass (Da), K = 1.81 × 10−3 mL g−1 and a = 0.93, constants determined for the polymer–solvent system (0.1 M acetic acid and 0.2 M sodium chloride)

[η] = K × (MM)a

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidant activity was tested using two different methods as DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radical-scavenging and ABTS: 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethyl-benzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid). The DPPH radical scavenging activity (RSA) of chitosan was measured using the method described by Younes et al. [22] with modifications. An aliquot of 2000 µL of chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk at different concentrations (0.50 to 5.00 mg mL−1) in 0.1 mol/L acetic acid was mixed with 1500 µL of ethanol (99.5%). Then, 500 µL of 0.02% DPPH in 99.5% ethanol was added. The mixtures were then incubated for 60 min in the dark at room temperature and the reduction in DPPH radical was measured at 517 nm (Biospectro, SP-22, Curitiba, Brazil). Blank control was conducted by replacing the chitosan with an equal volume of distilled water following the same procedure. The DPPH radical-scavenging activity was tested in triplicates, and the results were represented as the percentage of radical scavenging activity (RSA%).

The ABTS radical scavenging activity of chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk was measured following the method shown in previous work of Re et al. [23] with some modifications. The ABTS radical was prepared by mixing the aqueous solutions with 7 mM ABTS and 140 mM potassium persulfate and incubated for 16 h at room temperature in the dark. After the initial incubation, the work solution was prepared by diluting in ethanol (99.5%) to obtain an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.020 at 734 nm. Subsequently, 2000 µL of chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk at different concentrations (0.50 to 5.00 mg mL−1) in 0.1 mol L−1 acetic acid was combined with 2000 µL of the ABTS• working solution at room temperature and kept away from light. After 6 min the decrease in absorbance was measured at 734 nm. Blank control was conducted by replacing the chitosan with an equal volume of 0.1 mol L−1 acetic acid. The antioxidant activity was tested in triplicates, and the results were represented as percentage (%) inhibition of the ABTS• radical.

2.6. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk was evaluated according to Gómez-Guillén et al. [24], with slight modifications. Bacterial inoculum was prepared according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) using disk diffusion method [25] against Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and Gram-negative bacteria Citrobacter freundii (ATCC 1953), Escherichia coli (ATCC 29214), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145) and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Choleraesuis (ATCC 13312). The strains were grown in brain heart infusion broth (BHI) (Kasvi, Pinhais, Brazil) were incubated at 37 °C overnight (Solab, SL-01, Piracicaba, Brazil). The antimicrobial activity was measured on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) (Kasvi, Pinhais, Brazil) plates inoculated with 100 µL of each bacterial strain (1–2 × 108 CFU/mL equivalent to the 0.5 McFarland standard) and spread with a Digralsky handle. Then, sterile filter paper disks (5 mm diameter) soaked with 40 µL of chitosan samples (5.00, 2.50, 1.25 and 0.50 mg mL−1) prepared in acetic acid (0.1 mol L−1) were laid onto the inoculated plate surface. The control was prepared using 40 µL of acetic acid (0.1 mol L−1) for each bacterial strain. After incubation aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h, the diameter of the zones of inhibition was quantified using a ruler with mm precision (excluding disk diameter of 5 mm). Measurements were taken from edge to edge across the center of the zone. Each control was subtracted from the bacteria corresponding value.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Student’s t-test was applied to compare means between two independent groups (p < 0.05). For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used. Model significance and R2 values were obtained via ANOVA. Analyses were performed using Statistica® version 5.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chitosan Production

Commercially, chitosan, of marine origin, is found in various degrees of purity with different degrees of deacetylation, depending on the application [26]. For pharmaceutical and food applications, it is necessary to determine parameters such as residual inorganic compounds and protein content in order to guarantee the safety and quality of the polymer [27]. For this reason, obtaining chitosan from fungi of the order Mucorales stands out as an alternative to overcome the limitations of the industrially used method, since there is no mandatory need for a deacetylation step (the polymer is naturally deacetylated) and it does not present residues of allergenic proteins, such as tropomyosin present in crustacean by-products [13].

Fungi of the genus Rhizopus, are particularly suitable for solid-state fungi (SSF) and do not produce any toxic substances [28]. These fungi contain proteins, polyphosphates, polyglucuronic acid, chitin, and native chitosan in their cell walls. For this reason, they stand out as producers of chitosan [13].

The utilization of rice bran and rice husk (Table 1) as alternative substrates for chitosan production through solid-state fermentation with Rhizopus oryzae represents a strategic approach to circular bioeconomy. These agro-industrial residues, generated at rates of 0.05–0.1 kg and 0.28 kg per kilogram of milled rice, respectively, constitute significant underutilized by-products whose conversion into chitosan addresses both environmental challenges of rice residue disposal and the economic demand for sustainable biopolymer production. The valorization of these substrates aligns with circular bioeconomy principles, as they possess favorable nutritional composition—including starch (35.3–47.5%), proteins (15–18%), and fibers—that support microbial growth and chitosan biosynthesis while reducing dependence on crustacean-derived chitin sources and generating economically and environmentally favorable biotechnological processes [12,29,30,31,32].

Table 1.

Variables and levels used in full factorial design and the chitosan yield in the solid-state fermentation of rice by-products by Rhizopus oryzae.

Table 1.

Variables and levels used in full factorial design and the chitosan yield in the solid-state fermentation of rice by-products by Rhizopus oryzae.

| Experiment | Coded Variables | Uncoded Variables | Chitosan Yield (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | Rice Husk | Urea | Moisture (%) | Rice Husk (%) | Urea (g L−1) | ||

| 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.76 |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 70.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.32 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 40.00 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.39 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 70.00 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.37 |

| 5 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 40.00 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 7.02 |

| 6 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 70.00 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 0.71 |

| 7 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 40.00 | 100.0 | 3.6 | 0.25 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 70.00 | 100.0 | 3.6 | 0.27 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55.00 | 50.00 | 1.80 | 31.4 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55.00 | 50.00 | 1.80 | 31.3 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55.00 | 50.00 | 1.80 | 31.5 |

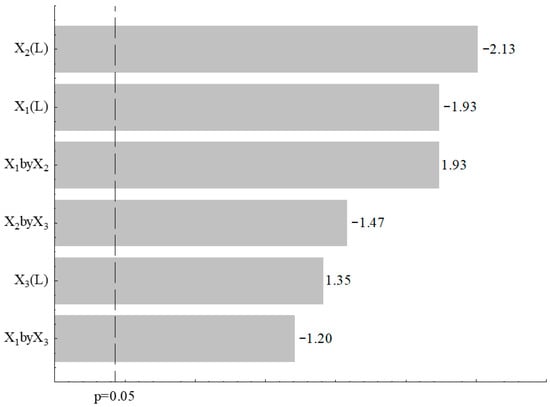

The yield of chitosan ranged from 0.32 to 31.5% (Table 1), with the highest values observed in the central point (55% moisture, 50% rice husk and urea 1.8 g/L). Figure 1 shows the effects of variables on chitosan yield through a Pareto chart, which identifies the relative importance of each factor and their interactions on the fermentation process.

Figure 1.

Pareto chart of process variables (moisture (%)-X1, rice husk (%)-X2, and urea (g L−1)-X3) on chitosan yield.

The Pareto analysis revealed that moisture content (X1) emerged as the most significant factor affecting chitosan production, with a negative effect of −2.13. This result is consistent with solid-state fermentation (SSF) dynamics, which requires a delicate moisture balance: sufficient water content to support microbial growth, but not excessive levels that would compromise substrate porosity and limit oxygen diffusion necessary for the aerobic metabolism of Rhizopus oryzae [8,33]. The optimal moisture level of 55% identified at the central point reflects this equilibrium, as lower moisture restricts fungal colonization while higher moisture impairs aeration, a critical parameter previously established in SSF optimization studies [34,35].

The percentage of rice husk as substrate (X2) was the second most influential variable, with a negative effect of −1.93, indicating that increased rice husk concentration above optimal levels reduces chitosan production. This can be attributed to potential nutritional imbalances at higher substrate concentrations, as rice husk, despite its favorable composition, may become limiting in readily available nitrogen sources, or create a physical structure that hinders uniform fungal growth across the fermentation matrix [2,36]. The optimal concentration of 50% rice husk suggests an adequate balance between structural support and nutrient availability, consistent with findings on substrate composition optimization in fungal fermentation systems [37].

Conversely, urea concentration (X3) demonstrated a positive effect of 1.93, indicating that increased urea supplementation enhances chitosan production. As a readily assimilable nitrogen source, urea is essential for fungal protein synthesis, biomass accumulation, and consequently, chitosan biosynthesis [6]. This finding emphasizes the importance of nitrogen availability for optimizing Rhizopus oryzae fermentation, aligning with established knowledge that nitrogen is a critical nutrient for polysaccharide production in fungal systems [38,39].

Secondary interactions were also observed: the interaction between moisture and rice husk (X1 × X2) showed a negative effect of −1.47, suggesting that the detrimental effects are amplified when both factors are simultaneously elevated. In contrast, the positive interaction between moisture and urea (X1 × X3) of 1.35 indicates that improved nutrient status through urea supplementation can partially mitigate the negative effects of suboptimal moisture levels. The interaction between rice husk and urea (X2 × X3) was minimal (−1.20), suggesting limited antagonistic effects at elevated concentrations of both factors, consistent with the hierarchical importance of primary factors over their interactions in SSF optimization [7].

The ANOVA results indicated that the fitted model was not statistically significant (F_calculated < F_tabulated); therefore, the factorial design did not support predictive modeling or optimization claims. Accordingly, no regression equation or response surface analysis was generated. Nevertheless, the factorial design provided useful qualitative insights into the influence of the tested variables on chitosan production.

The Pareto chart was interpreted strictly as a descriptive tool, indicating that excessive moisture content and a high proportion of rice husk tended to reduce chitosan production, whereas urea supplementation generally increased the response. Although these effects could not be quantified or modeled due to the lack of statistical significance, they help contextualize the experimental trends observed.

Among all experimental conditions evaluated, the highest chitosan yield (31.4%) was obtained at the central point (55% moisture, 50% rice husk, 1.8 g L−1 urea). This value is presented as the best observed condition rather than an optimized or predicted value. The observed yield is consistent with the combined effects of moderate moisture content, balanced substrate structure, and adequate nitrogen availability, which collectively support fungal growth under SSF conditions.

Several studies have described chitosan production by Rhizopus oryzae under submerged and solid-state fermentation using different substrates and extraction strategies, with yields varying widely depending on culture conditions and the basis of calculation.

Chitosan isolated from R. oryzae cultivated in media supplemented with collagen and protein hydrolysates derived from tannery waste showed yields of approximately 14.7–15% relative to total fungal biomass, with chitosan concentrations ranging from 0.479 to 0.733 g L−1, depending on the composition of the yeast–hydrolysate–glucose medium [40]. Under submerged fermentation conditions, Erdoğmuş et al. [41] demonstrated that R. oryzae NRRL 1526 achieved a biomass concentration of 8.1 g L−1 after six days of incubation, from which chitosan was recovered at a yield of 18.6% (w/w, biomass basis). Under identical conditions, Aspergillus niger showed a lower chitosan content (12.5%), reinforcing the species-dependent nature of fungal chitosan biosynthesis. In solid-state fermentation systems, Khalaf [42] observed chitosan production by R. oryzae grown on rice husk at 5.63 g kg−1 dry substrate, which was comparable to values obtained for A. niger and Penicillium citrinum under similar conditions. Cardoso et al. [12] reported chitosan yields of 0.7–2.9% when utilizing agro-industrial substrates (corn steep liquor and honey) as substrates with Rhizopus arrhizus, substantially lower than the results obtained in the present work. Almeida et al. [13] achieved yield of only 3.9% using Rhizopus stolonifer on PDA medium, reinforcing the importance of substrate on chitosan yield.

The chitosan yield of 31.4% obtained in this study represents a substantial improvement compared to values previously described for Rhizopus-mediated fermentation. The relatively high yield observed can be attributed to the characteristics of the substrate matrix (rice bran and rice husk), which provides both structural porosity and nutrient availability, as well as to the moisture content and nitrogen levels applied. Importantly, these interpretations are based on the experimental outcomes of the factorial design rather than on statistical optimization.

An additional factor that may have contributed to the elevated yield is the ecological origin of the fungal strain. Rhizopus oryzae used in this study was isolated from rice husk [17], an environment naturally enriched in lignocellulosic residues similar to those present in the rice bran–rice husk mixture. Fungal strains adapted to such ecological niches often exhibit enhanced enzymatic potential and physiological compatibility with rice-based substrates, which can improve colonization, substrate degradation, and biomass accumulation under SSF conditions. This ecological alignment may have favored substrate utilization efficiency, thereby supporting the high chitosan yield observed under the best experimental condition.

Overall, these results demonstrate that chitosan production by SSF using R. oryzae is strongly influenced by the selected fermentation conditions. Although the factorial model did not reach statistical significance, the experimental evidence highlights moisture control, substrate balance, and nitrogen supplementation as key variables affecting chitosan formation from rice residues.

From an industrial perspective, scaling up solid-state fermentation remains challenging, mainly due to limitations in heat dissipation, oxygen transfer, and moisture uniformity. Nevertheless, the use of low-cost agro-industrial residues such as rice bran and rice husk offers advantages in terms of substrate availability, porosity, and aeration. The balanced substrate composition evaluated in this study may facilitate airflow and reduce compaction, which are critical factors in large-scale SSF reactors. Nevertheless, further studies focusing on reactor design, bed depth, and process control will be required to validate the scalability of the proposed process [43,44].

3.2. Chitosan Characterization

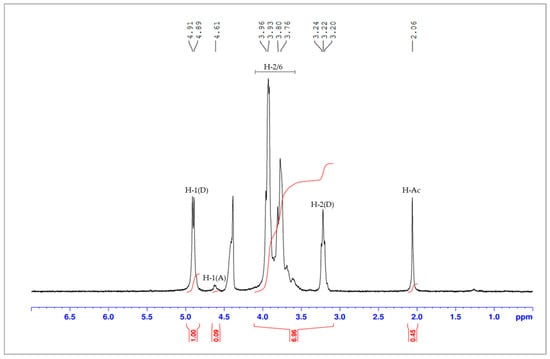

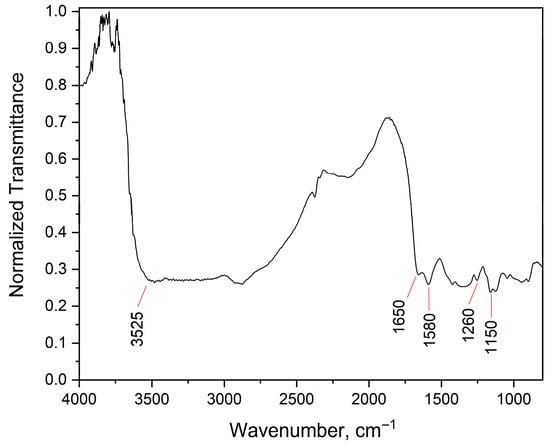

The degree of deacetylation (DD) was determined by two complementary methods. FTIR spectroscopy yielded a DD of 85.8%, while NMR spectroscopy provided a DD of 87.0%. The DD was calculated using the integrals of the peak of the deacetylated monomer (H1-D, first hydrogen of the glycosidic ring) and the peak of the three protons of the acetyl group (H-Ac), as shown in Figure 2. The FTIR spectrum obtained in this study is consistent with previous reports in the literature [45], showing characteristic peaks around 3525 cm−1 (O–H stretching), 1650 cm−1 (C=O stretching), 1570 cm−1 (–NH2 bending), 1260 cm−1 (C–N stretching), and 1150 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching). The degree of deacetylation (DD) of the chitosan was quantitatively estimated from the FTIR spectra (Figure 3) using the baseline method, based on the absorbance ratio of the amide I band (at 1655 cm−1) and the hydroxyl group band (at 3450 cm−1), as described by Yusharani et al. [45]. The slight difference between the FTIR (85.8%) and 1H NMR (87.0%) results can be attributed to the inherent differences in the principles of these analytical techniques. While 1H NMR provides a more direct and quantitative measure of the acetyl content by integrating specific proton signals, FTIR relies on absorbance ratios, which can be influenced by factors such as baseline selection, band overlap, and sample preparation. Nevertheless, the strong correlation between the two methods confirms the high degree of deacetylation achieved in the chitosan produced from fermented rice bran and husk, reinforcing the quality and potential bioactivity of the biopolymer. The average DD, considering both techniques, was determined to be 86.4 ± 0.6%, remarkably close to the value of commercial chitosan used as a reference standard (90%) [46].

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum for chitosan extracted from rice bran and husk fermented with Rhizopus oryzae. H-1(D)-proton H1 of deacetylated monomer; (H-Ac)-protons of acetyl group; H(2/6)-protons H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H6′; H-1(A)-proton H1 of acetylated monomer. H-2(D)-proton H2 of deacetylated monomer.

Figure 3.

FTIR Spectrum of chitosan produced by solid-state fermentation of rice bran and rice husk using Rhizopus oryzae.

The high degree of deacetylation achieved (86.4 ± 0.6%) is a particularly satisfactory result since this parameter is directly related to the reactivity, physicochemical and biological properties of the polymer [47]. As discussed in the introduction, higher DD values are associated with increased positive charge density, which directly enhances antimicrobial efficacy through enhanced disruption of bacterial cell membranes [48]. This result demonstrates that chitosan produced through Rhizopus oryzae fermentation on agro-industrial substrates can achieve DD values comparable to commercial chitosan, validating the biotechnological approach as a viable alternative to chemical extraction from crustacean sources.

Chatterjee, Guha, and Chatterjee [49] evaluated chitosan production by Rhizopus oryzae in solid-state fermentation using culture media containing whey (at lactose concentration of 4.5%) or cane molasses as carbon source replacements. The authors observed that chitosan obtained by fermentation with agro-industrial substrates showed degrees of deacetylation of 81.9% and 87.3%, respectively—results comparable to those of the present study (86.4 ± 0.6%). This consistency across different agro-industrial substrates and fermentation conditions suggests that Rhizopus oryzae inherently produces highly deacetylated chitosan, a significant advantage over chemical deacetylation methods that require strict control of reaction parameters to achieve similar DD values.

Chitosan is a natural cationic polysaccharide with a wide molecular weight range. The molecular weight (MW) of chitosan significantly influences its functional properties, including antibacterial activity, permeation resistance, drug loading and release rates, drug delivery efficiency, and pollutant removal capacity [50,51,52,53,54]. Therefore, determination of chitosan molecular weight is of critical importance for predicting its functional performance. The molecular weight of chitosan extracted from fermented rice bran and husk was determined to be 59.65 kDa through viscosimetry, a value typical for biopolymers generated through fungal fermentation and within the range (20–100 kDa) commonly employed for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. This MW value, combined with the high DD (86.4 ± 0.6%), positions the produced chitosan as a high-quality biopolymer suitable for multiple industrial applications.

The protein value obtained from fermented biomass (7.9 ± 0.2%) was higher than the reported by chitosan obtained from mealworm’s cuticles (5.4 ± 0.2%) [46]. A higher nitrogen content suggests a higher degree of deacetylation (DDA), which is a critical factor influencing its bioactivity [55].

Thus, the nitrogen content of chitin and chitosan ranges from 5 to 8%, and the presence of amino groups gives these glycans distinctive biological functions and susceptibility. Furthermore, the degree of deacetylation determined using two independent methods showed good agreement, indicating the structural homogeneity of the extracted chitosan and supporting its chemical identity.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk was evaluated using ABTS and DPPH assays, as presented in Table 2. In general, chitosan exhibited significant (p < 0.05) antioxidant activity in a concentration-dependent manner. By the DPPH method, chitosan reached inhibition percentages ranging from 84.9% to 94.0% at concentrations between 0.5 and 5.00 mg mL−1. Similarly, ABTS scavenging activity showed a concentration-dependent pattern, ranging from 12.2% to 32.9% across the same concentration range. These differential results suggest that the functional groups of chitosan were substantially more effective at scavenging the DPPH radical compared to the ABTS radical. This difference can be attributed to the distinct chemical properties of these two radicals: ABTS generates cationic radicals, while DPPH is a neutral free radical [56]. Chitosan possesses amino groups (–NH2) and hydroxyl groups (–OH), which can directly react with free radicals. Furthermore, chitosan has the ability to donate hydrogen atoms and effectively neutralize free radicals through electron transfer mechanisms [57].

Table 2.

Antioxidant activities of chitosan at different concentrations.

At concentrations of 5.00 and 2.50 mg mL−1, the chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk exhibited the highest DPPH scavenging capacity (p < 0.05) of 94.0% and 93.4%, respectively. Schreiber et al. [58] reported that native chitosan with molecular weight of 307 kDa and degree of deacetylation (DD) of 80% demonstrated insignificant DPPH scavenging ability (9.4%), substantially lower than the results obtained in the present study. In contrast, chitosan extracted from the cuttlefish bone of Sepia pharaonis with a DD of 87.2% exhibited 73.2% DPPH radical inhibition [57]. The superior antioxidant activity observed in the present study (94.0% DPPH inhibition) can be attributed to the high degree of deacetylation (DD = 86.4 ± 0.6%), which increases the density of reactive amino groups available for radical scavenging, and the relatively low molecular weight (MW = 59.65 kDa), which facilitates greater accessibility of functional groups to reactive oxygen species (ROS). High DD values have been shown to promote antioxidant activity, while lower MW values demonstrate superior activity, a phenomenon explained by the shorter polymer chain length and reduced intramolecular hydrogen bonding, which releases reactive groups from intramolecular interactions, allowing them to freely engage in ROS quenching [59].

Molecular weight plays a critical role in chitosan antioxidant efficacy. Youn et al. [60] evaluated chitosan samples with molecular weights of 30, 90, and 120 kDa, finding that antioxidant activity was superior at lower molecular weights. This observation is further supported by Sun et al. [61], who demonstrated that chitosan antioxidant activity is strongly correlated with MW, with activity increasing as MW decreases. The mechanistic basis for this relationship involves the propensity of shorter chitosan chains to form fewer intramolecular hydroxyl and amino group interactions. Conversely, at lower MW, reduced intramolecular bonding results in more activated and accessible hydroxyl and amino groups, thereby enhancing radical scavenging capacity. These findings substantiate the superior antioxidant performance (94.0% DPPH inhibition at 5.00 mg mL−1) of the chitosan produced in this study, which combines both favorable characteristics: high DD (86.4 ± 0.6%) and low MW (59.65 kDa). This combination validates the biotechnological production approach as an effective strategy for generating high-quality chitosan with enhanced antioxidant properties suitable for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and food preservation applications.

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of chitosan from fermented rice bran and husk with Rhizopus oryzae was evaluated against microbial species of pathogens important in foodborne diseases and/or human pathogenic bacteria, specifically Citrobacter freundii (C. freundii), Escherichia coli (E. coli), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Choleraesuis (S. choleraesuis). These organisms were selected because they represent both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with significant relevance to food safety and clinical infections [62,63].

The results presented in Table 3 demonstrate that chitosan produced from fermented rice bran and husk exhibits antimicrobial activity against all bacterial strains tested. Omogbai and Ikenebomeh [64] investigated chitosan production using a laboratory-scale solid-state fermentation (SSF) process with four fungal specie (Penicillium expansum, Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus oryzae, and Fusarium moniliforme) using corn straw as the substrate. These authors observed that the extracted chitosan exhibited inhibitory activity against some food-borne bacterial pathogens as E. coli, Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus subtilis, at a chitosan concentration of 50 mg L−1. In this study, chitosan concentration played an important role in its antimicrobial capacity, as observed in the present study: the greatest antimicrobial effect was observed at the highest concentration tested (5.00 mg mL−1), with activity decreasing at lower concentrations (2.50–0.00 mg mL−1) for most microbial species (p < 0.05). This concentration-dependent antimicrobial activity has been previously observed in other studies with chitosan and reflects the dose–response relationship inherent to antimicrobial agents [65].

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of chitosan.

According to Robinson et al. [66], weak organic acids, such as acetic acid, penetrate bacterial cells in their non-dissociated form, thereby disrupting internal pH homeostasis. The alteration in intracellular pH, results in multiple effects, including damage to the cell membrane, DNA, and proteins, as well as increased energy expenditure associated with proton efflux mechanisms. However, in the present study, the control (acetic acid at 0.1 mol L−1) did not show inhibitory activity against most of the microorganisms tested, except for E. coli. The control concentration used (0.1 mol L−1 approximately 0.59%; v/v) may be below the inhibitory threshold required for most microorganisms evaluated. Robinson et al. [66] also demonstrated that inhibitory effects at different pH level vary substantially among microbial species, which may explain the observed sensitivity of E. coli and the lack of response in the other microorganisms tested.

Against S. choleraesuis, no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed among the four chitosan concentrations tested. In contrast, statistical analysis revealed that chitosan exhibited significantly higher antimicrobial activity than control (acetic acid at concentration of 0.1 mol L−1) (p < 0.05). The highest inhibition zone of S. choleraesuis ranging to 27.50 mm, 26.00 mm, 25.50 mm and 27.25 mm from 5.00 to 0.50 mg mL−1, respectively. Its behavior may indicate that chitosan has a saturation point at low concentrations, such that at higher concentrations no further advantage is achieved in terms of diffusion or antibacterial activity for S. choleraesuis [63].

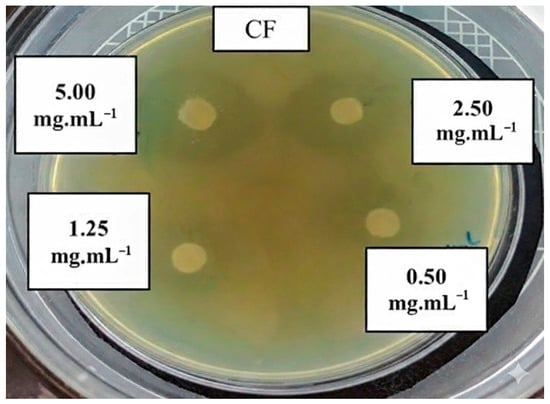

According to the categorization proposed by Fachriyah, Wibawa, and Awaliyah [67], microbial growth inhibition is classified as: very strong (>21 mm), strong (11–20 mm), moderate (6–10 mm), and weak (<5 mm). Based on Table 3, the antibacterial effects against C. freundii (Figure 4) and P. aeruginosa at 5.00 50 mg mL−1 (20.13 ± 0.13 mm and 19.25 ± 2.25 mm, respectively) fall within the strong inhibition category. In contrast, E. coli and S. aureus demonstrated moderate inhibition at the same concentration (6.75 ± 0.13 mm and 9.75 ± 1.75 mm, respectively), while S. choleraesuis exhibited very strong inhibition (27.50 ± 2.50 mm). These results correlate directly with the high degree of deacetylation (DD = 88.2%) of the chitosan produced in this study. According to Ke et al. [68], high DD values enhance electrostatic interactions with microbial cell surfaces, resulting in superior antimicrobial activity. The DD achieved in this work (86.4 ± 0.6%) is within the typical range for commercial chitosan (72–90%), as verified by Remesh et al. [69], confirming the high quality of the produced biopolymer. Chitosan with low MW showed antimicrobial activity by intracellular antimicrobial activity, thereby affecting RNA, protein synthesis, and mitochondrial function [68].

Figure 4.

Antibacterial activity of chitosan on Citrobacter freundii at different concentrations (0.50 to 5.00 mg mL−1).

In general, Gram-negative bacteria (C. freundii, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. choleraesuis) exhibited greater susceptibility to chitosan than Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus), a finding consistent with previous studies [22,63]. This differential susceptibility can be attributed to structural differences in bacterial cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria possess thicker peptidoglycan layers, which may impede direct binding of chitosan to the cell membrane and result in greater resistance to chitosan treatment [70]. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer, facilitating more efficient chitosan penetration. Additionally, Gram-negative bacteria possess an outer membrane composed of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) with substantial negative charge density, whereas Gram-positive bacteria lack this structural feature [68,70]. The strong electrostatic interactions between the cationic amino groups of chitosan (resulting from its high DD) and the negatively charged LPS and cell wall surfaces of Gram-negative bacteria result in substantial disruption of cell membrane integrity and bacterial cell death [65,71]. These mechanistic insights validate the relationship between DD and antimicrobial efficacy, demonstrating that the chitosan produced in this study possesses both the chemical properties (high DD) and biological activities required for practical antimicrobial applications.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes an efficient solid-state fermentation process using Rhizopus oryzae for the production of high-quality chitosan from fermented rice bran and rice husk. Under optimized conditions (55% moisture, 50% rice husk, 1.8 g/L urea), the process achieved a chitosan yield of 31.4%, exceeding commonly reported values for fungal or chemically derived chitosan. The biopolymer presented a high degree of deacetylation (86.4 ± 0.6%) and a molecular weight of 59.65 kDa, consistent with commercial specifications.

The produced chitosan exhibited pronounced antioxidant activity (94.0% DPPH inhibition) and broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects, with functional properties directly associated with its elevated deacetylation degree. These results confirm that SSF using agro-industrial residues can generate bioactive chitosan suitable for value-added applications.

From a bioprocessing perspective, this approach offers a sustainable alternative to chemical deacetylation, enabling waste valorization and reducing reliance on marine-derived chitin sources. Future work should address process scale-up, long-term material stability, regulatory requirements for advanced applications, and techno-economic analysis to support industrial implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L.G., L.K., S.C.B. and E.G.P.; methodology, H.L.G., L.K., M.d.R. and E.Q.O.; validation, H.L.G., L.K. and S.C.B.; formal analysis, H.L.G., L.K., M.d.R. and E.Q.O.; investigation, H.L.G., L.K., M.d.R. and E.Q.O.; resources, S.C.B., L.K. and E.G.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.G., L.K., M.d.R. and E.Q.O.; writing—review and editing, L.K., S.C.B. and E.G.P.; visualization, H.L.G., L.K., M.d.R., E.Q.O., S.C.B. and E.G.P.; supervision, L.K., S.C.B. and E.G.P.; project administration, L.K. and E.G.P.; funding acquisition, L.K. and E.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Brazilian agencies FAPERGS (21/2551-0000684-6) and CNPq. Part of this study was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. Ednei G. Primel received a productivity research fellowship from the Brazilian Agency CNPq (DT 305065/2025-4) and Larine Kupski received a productivity research fellowship from the Brazilian Agency CNPq (PQ 306194/2025-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the Centro Integrado de Análises—CIA-FURG (funded by Finep-CT-INFRA, CAPES-Pró-Equipamentos, and MCTI-CNPq-SisNano2.0) for NMR analysis performed, especially to Diego Cabrera.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| DD | Degree of Deacetylation |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SSF | Solid State Fermentation |

References

- Tsurkan, M.V.; Voronkina, A.; Khrynyk, Y.; Wysokowski, M.; Petrenko, I.; Ehrlich, H. Progress in chitin analytics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddam, P.; Gaur, V.K.; Sihori, R.; Varjani, S.; Kim, S.H.; Wong, J.W.C. Sustainable processing of food waste for production of bio-based products for circular bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 325, 124684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudatta, B.P.; Sugumar, V.; Varma, R.; Nigariga, P. Extraction, characterization and antimicrobial activity of chitosan from pen shell, Pinna bicolor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Nafchi, A.M.; Ariffin, F.; Wijekoon, M.J.O.; Al-Hassan, A.A.; Dheyab, M.A.; Ghasemlou, M. Recent advances in extraction, modification, and application of chitosan in packaging industry. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xue, C.; Mao, X.J. Chitosan: Structural modification, biological activity and application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4532–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, L.R.R.; de Araújo, M.B.; da Costa, D.P.; de Lima, M.A.B.; de Almeida, J.W.L.; de Medeiros, E.V. Agroindustrial waste as ecofriendly and low-cost alternative to production of chitosan from Mucorales fungi and antagonist effect against Fusarium solani (Mart.) Sacco and Scytalidium lignicola Pesante. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghormade, V.; Pathan, E.K.; Deshpande, M.V. Can fungi compete with marine sources for chitosan production? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ahluwalia, V.; Saran, S.; Kumar, J.; Patel, A.K.; Singhania, R.R. Recent developments on solid-state fermentation for production of microbial secondary metabolites: Challenges and solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahzadeh, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Lennartsson, P.R. 2—Fungal biotechnology. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Taherzadeh, M.J., Ferreira, J.A., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 31–66. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, A.C.L.; Melo, T.B.L.; Paiva, W.S.; Souza, F.S.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. Economic microbiological conversion of agroindustrial wastes to fungi chitosan. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2020, 92, e20180885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Hernández, L.; Ramírez-Toro, C.; Ruiz, H.A.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar-Gonzalez, M.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Rhizopus oryzae—Ancient microbial resource with importance in modern food industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 257, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Lins, C.I.M.; Santos, E.R.; Silva, M.C.F.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. Microbial enhance of chitosan production by Rhizopus arrhizus using agroindustrial substrates. Molecules 2012, 17, 4904–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.R.; Pinto, N.A.; Soares, I.C.; Ferreira, L.B.C.; Lima, L.L.; Leitão, A.A.; Guimarães, L.G.L. Production and physicochemical properties of fungal chitosans with efficacy to inhibit mycelial growth activity of pathogenic fungi. Carbohydr. Res. 2023, 525, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdini, F.; Amini, M.A.; Nafissi-Varcheh, N.; Faramarzi, M.A. Production, physiochemical and antimicrobial properties of fungal chitosan from Rhizomucor miehei and Mucor racemosus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2010, 47, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.R.R.; Stamford, T.C.M.; de Oliveira, K.Á.R.; Pessoa, A.d.M.P.; de Lima, M.A.B.; Pintado, M.M.E.; Câmara, M.P.S.; Franco, L.d.O.; Magnani, M.; de Souza, E.L. Chitosan produced from Mucorales fungi using agroindustrial by-products and its efficacy to inhibit Colletotrichum species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.C.; Kupski, L.; de Souza, S.B.D.S.; Barros, B.C.B. Influence of fermentation conditions by Rhizopus oryzae on the release of phenolic compounds, composition, and properties of brewer’s spent grain. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupski, L.; Pagnussatt, F.A.; Buffon, J.G.; Furlong, E.B. Endoglucanase and total cellulase from newly isolated Rhizopus oryzae and Trichoderma reesei: Production, characterization, and thermal stability. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 172, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, C.; Li, S.; Xu, Q.; Ying, H.; Huang, H.; Ouyang, P. Chitosan production from hemicellulose hydrolysate of corn straw: Impact of degradation products on Rhizopus oryzae growth and chitosan fermentation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 51, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavertu, M.; Xia, Z.; Serreqi, A.N.; Berrada, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Wang, D.; Buschmann, M.D.; Gupta, A. A validated 1H NMR method for the determination of the degree of deacetylation of chitosan. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2003, 32, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Neau, S.H. In vitro degradation of chitosan by a commercial enzyme preparation: Effect of molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, I.; Hajji, S.; Frachet, V.; Rinaudo, M.; Jellouli, K.; Nasri, M. Chitin extraction from shrimp shell using enzymatic treatment. Antitumor, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 69, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Alemán, A.; Giménez, B.; López de Lacey, A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial peptide fractions from squid and tuna skin gelatin. In Sea by-Products as Real Material: New Ways of Application; Le Bihan, E., Koueta, N., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Kerala, India, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Fourth Informational Supplement in CLSI Document M100-S24; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, H.; Aghbashlo, M.; Sharma, M.; Gaffey, J.; Manning, L.; Basri, S.M.M.; Kennedy, J.F.; Gupta, V.K.; Tabatabaei, M. Chitin and chitosan derived from crustacean waste valorization streams can support food systems and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymánska, E.; Winnicka, K. Stability of chitosan—A challenge for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1819–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.d.S.; Feddern, V.; Kupski, L.; Cipolatti, E.P.; Badiale-Furlong, E.; de Souza-Soares, L.A. Physico-chemical characterization of fermented rice bran biomass Caracterización fisico-química de la biomasa del salvado de arroz fermentado. CyTA J. Food 2010, 8, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukma, A.; Oktavianty, H.; Sumardiono, S. Optimization of solid-state fermentation condition for crude protein enrichment of rice bran using Rhizopus oryzae in tray bioreactor. Indones. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 26, 57561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarska, K.; Sikora, M.; Owczarek, M.; Jóźwik-Pruska, J.; Wiśniewska-Wrona, M. Chitin and chitosan as polymers of the future—Obtaining, modification, life cycle assessment and main directions of application. Polymers 2023, 15, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Chawade, A.; Vivekanand, V.; Pareek, N. Insights into the production and versatile agricultural applications of nanochitin for sustainable circularity: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 12, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, K.; Qazanfarzadeh, Z.; Jiménez-Quero, A. Fungal fermentation: The blueprint for transforming industrial side streams and residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2026, 440, 133426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Sakinah, A.M.M.; Zularisam, A.W.; Sirohi, R.; Khilji, I.A.; Ahmad, N.; Pandey, A. Advances in solid-state fermentation for bioconversion of agricultural wastes to value-added products: Opportunities and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. Solid-state fermentation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2003, 13, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Demain, A.L. Metabolic regulation and overproduction of primary metabolites. Microb. Biotechnol. 2008, 1, 283–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Hernández-Almanza, A.; Martínez-Medina, G.A.; Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Londoño-Hernández, L.; Aguilar, C. Recent advances on the microbiological and enzymatic processing for conversion of food wastes to valuable bioproducts. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 38, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, G.M.; Puthiyamadam, A.; Sasikumar, K.; Ashoor, S.; Sukumaran, R.K. Biological treatment of prawn shell wastes for valorization and waste management. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 15, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sarsaiya, S.; Chen, H.; Singh, E.; Kumar, A.; Ravindran, B.; Awasthi, S.K.; Liu, T.; Duan, Y.; et al. Resource recovery and circular economy from organic solid waste using aerobic and anaerobic digestion technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.J.; Mao, H.H.; Fang, W.; Li, Z.Q.; Shi, D.; Li, Z.W.; Zhou, T.; Luo, X.C. Enzymatic conversion and recovery of protein, chitin, and astaxanthin from shrimp shell waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Das, A.; Paul, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Choudhury, P. Utilization of fleshing waste of leather processing for the growth of zygomycetes: A new substrate for economical production of bio-polymer chitosan. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 343, 118141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğmuş, S.F.; Altıntaş, Ö.E.; Çelik, S. Production of fungal chitosan and fabrication of fungal chitosan/polycaprolactone electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2023, 86, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalaf, S.A. Production and characterization of fungal chitosan under solid-state fermentation conditions. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2004, 6, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, M.K.; Vs, B.S.; B, S.; Avanthi, A. Chapter 16—Scale-up strategies for solid-state fermentation. In Biotechnology Engineering; Shet, V.B., Kanthakere, S., Mubarak, N.M., Karri, R.R., Hadi Dehghani, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 345–374. [Google Scholar]

- Crognale, S.; Russo, C.; Petruccioli, M.; D’Annibale, A. Chitosan Production by Fungi: Current State of Knowledge, Future Opportunities and Constraints. Fermentation 2022, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusharani, M.S.; Ulfin, I.; Ni’mah, Y.L. Synthesis of water-soluble chitosan from squid pens waste as raw material for capsule shell: Temperature deacetylation and reaction time. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 509, 012070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.J.d.S.; Oreste, E.Q.; Costa, H.L.G.; López, H.M.; Saad, C.D.M.; Prentice, C. Extraction, physicochemical characterization, and morphological properties of chitin and chitosan from cuticles of edible insects. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitosan: Structure, properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raafat, D.; Sahl, H.G. Chitosan and its antimicrobial potential—A critical literature survey. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Guha, A.K.; Chatterjee, B.P. Evaluation of quantity and quality of chitosan produced from Rhizopus oryzae by utilizing food product processing waste whey and molasses. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huei, C.R.; Hwa, H.D. Effect of molecular weight of chitosan with the same degree of deacetylation on the thermal, mechanical, and permeability properties of the prepared membrane. Carbohydr. Polym. 1996, 29, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.G.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Lee, C.Y.; Park, H.J. Molecular affinity and permeability of different molecular weight chitosan membranes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5915–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genta, I.; Perugini, P.; Pavanetto, F. Different molecular weight chitosan microspheres: Influence on drug loading and drug release. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1998, 24, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köping-Höggård, M.; Mel’nikova, Y.S.; Vårum, K.M.; Lindman, B.; Artursson, P. Relationship between the physical shape and the efficiency of oligomeric chitosan as a gene delivery system in vitro and in vivo. J. Gene Med. 2003, 5, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.C.; Li, Y.H.; Chen, C.C. Pollutant removal from aquaculture wastewater using the biopolymer chitosan at different molecular weights. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2005, 40, 1775–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiriphun, S.; Jirarattanarangsri, W.; Laokuldilok, T. Valorization of shrimp waste: Chitosan extraction, formulation, and antimicrobial assessment of a novel antiseptic mouth spray. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 9, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.C.; Nam, K.D.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, B.O.; Park, Y.I.; Park, J.K. Chitosan isolated from black soldier flies Hermetia illucens: Structure and enzymatic hydrolysis. Process Biochem. 2022, 118, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkaria, A.M.; Pitchai, A.; Ramasamy, P. Biocompatible chitosan from cuttlefish Sepia pharaonis: Extraction, characterization, and antioxidant properties. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.B.; Bozell, J.J.; Hayes, D.G.; Zivanovic, S. Introduction of primary antioxidant activity to chitosan for application as a multifunctional food packaging material. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 33, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Competitive biological activities of chitosan and its derivatives: Antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 2018, 1708172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Ahn, D.H. Studies on substitution effect of chitosan against sodium nitrite in pork sausage. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 33, 551–559. Available online: https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO200103042136015.page (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Sun, T.; Zhou, D.; Mao, F.; Zhu, Y. Preparation of low-molecular-weight carboxymethyl chitosan and their superoxide anion scavenging activity. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hianik, T.; Davoudian, K.; Spagnolo, S.; Subjaková, V.; Tatarko, M.; Thompson, M. Biosensors based on DNA aptamers for detection of bacterial pathogens in food. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; Volume 116, pp. 295–358. [Google Scholar]

- Pouri, S.; Fraile-Gutiérrez, I.; Gil-Gonzalo, R.; Acosta, N.; Navarro-García, F.; Aranaz, I. One-pot synthesis of silver-based chitosan macromolecular hydrogels and its antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 332, 148655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omogbai, B.; Ikenebomeh, M. Solid-state fermentative production and bioactivity of fungal chitosan. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2013, 3, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan, T.L.; Pitchai, A.; Ramasamy, P. Antimicrobial activity of chitosan phosphate derived from cuttlebone of Sepia brevimana against dental pathogens. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Clark, C.; Moakes, R.J.A.; Schofield, Z.; Moiemen, N.; Geoghegan, J.A.; Grover, L.M. Simultaneous viscoelasticity and sprayability in antimicrobial acetic acid-alginate fluid gels. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 166, 214051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachriyah, E.; Wibawa, P.J.; Awaliyah, A. Antibacterial activity of basil oil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and basil oil nanoemulsion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1524, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.L.; Deng, F.S.; Chuang, C.Y.; Lin, C.H. Antimicrobial actions and applications of chitosan. Polymers 2021, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remesh, S.D.; Sandrasaigaran, P.; Remesh, S.; Perumal, V.; Vun, J.Y.L.; Gandhi, S.; Hasan, H. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity of crustacean-derived chitosan against Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquina-Lemonche, L.; Burns, J.; Turner, R.D.; Kumar, S.; Tank, R.; Mullin, N.; Wilson, J.S.; Chakrabarti, B.; Bullough, P.A.; Foster, S.J. The architecture of the gram-positive bacterial cell wall. Nature 2020, 582, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, P.; Pitchai, A.; Ramasamy, P. Phosphorylated chitosan from the internal bone of Sepia kobiensis (Hoyle, 1885) and their inhibition against oral pathogens. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 550, 109413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.