Abstract

The optimization and control of the food fermentation process, which are vital for consistent product quality, are often hindered by the limitations of conventional analytical methods. Conventional wet-chemistry methods for food fermentation process analysis are slow, expensive, and require significant reagents and skilled personnel. Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is a powerful tool for non-destructive analysis of fermentation processes, with key advantages of speed, cost-effectiveness, minimal sample preparation, and reagent-free operation. This review provides an overview of the fundamental principles of NIR, the importance of chemometrics for building robust calibration models, and its application in the food fermentation process. Furthermore, this review also critically evaluates the challenges and opportunities of using NIR spectroscopy for fermentation process analysis and control. This review aims to provide novel insights into the application of NIR spectroscopy in the food fermentation industry, improving the process control and quality assurance for the intelligent transformation (from empirical control to AI-based control) of fermented foods.

1. Introduction

As an ancient biological processing method, fermentation has an irreplaceable role in leveraging microorganism-mediated processes in the food industry [1]. It is not merely a food preservation technique but also a key driver in shaping the diversity of global dietary cultures, as well as enhancing the nutritional value and sensory properties of food [2,3,4]. From bread and cheese to soy sauce and vinegar [5,6,7,8], fermented foods have been threaded throughout the history of human civilization, underpinned by the complex yet orderly transformation of substances driven by microbial metabolic activities. However, fermentation is a dynamic and nonlinear complex choreography [9]. Within this system, microbial cells function like miniature, highly sophisticated factories. The growth, metabolism, and product synthesis of microbes are not simple linear processes, but rather emerge from a complex choreography of interconnected and often competing biochemical networks. This is perfectly illustrated in traditional food fermentations, such as those used to make Baijiu, vinegar, and traditional fermented dairy products [10,11,12]. These networks are highly sensitive to changes in environmental factors such as temperature, acidity, oxygen, and substrate concentration. Changes in these factors affect the quality of fermented foods.

Process monitoring in the traditional fermented food industry has historically been characterized by a reliance on manual experience and offline sampling analysis, an approach with considerable drawbacks [13]. This process is labor-intensive and time-consuming [14,15]. Moreover, the substantial delay in obtaining analytical results (ranging from several hours to days) means that dynamic changes during fermentation cannot be captured in real time [16]. As a result, process control largely depends on delayed data and empirical judgment, making precise intervention difficult. These limitations have long posed challenges to quality control in traditional fermented food production, including inconsistent product quality, batch-to-batch variability, and difficulties in scaling up production. To address these bottlenecks, the introduction of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) has brought transformative potential to the field [17].

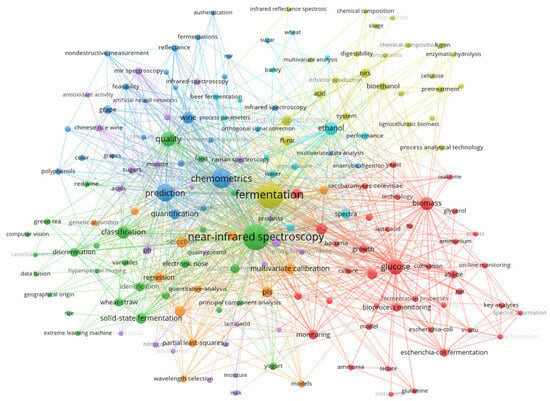

Within this framework, modern optical analytical techniques such as NIR have emerged as key tools for achieving PAT objectives [17,18]. As shown in Figure 1, a bibliometric analysis of the literature used the keywords “fermentation” and “NIR”. Among extracted keywords, “glucose”, “prediction”, and “chemometrics” appeared with high frequency. The NIR tool directly addresses this need by enabling the non-destructive and rapid acquisition of spectral data related to such critical parameters (such as sugar content, acidity, and ethanol) in the fermentation system. Combined with chemometric models, they facilitate simultaneous quantitative analysis of multiple components [19,20,21]. This “process transparency” empowers producers to gain real-time insights into microbial metabolic activity and changes in key parameters, thereby enabling precise tracking and control of fermentation profiles. It not only aids in optimizing process parameters and enhancing product consistency and yield but also opens new avenues for deciphering traditional fermentation mechanisms and achieving targeted precision control. This evolution is steadily advancing the industry toward digitalization and intelligent manufacturing.

Figure 1.

The bibliometric analysis of “fermentation” and “NIR” as keywords.

This review aims to critically assess the application of NIR spectroscopic techniques in fermentation monitoring, leveraging their considerable potential for process optimization. We begin by outlining the principles and strengths of NIR spectroscopy. Its role in the real-time online monitoring of critical parameters is then discussed. The focus subsequently shifts to how spectroscopic monitoring transcends observation to become the core of PAT from real-time feedback to predictive control. Finally, we will outline future research directions and existing challenges, intending to provide a solid theoretical and practical foundation for the intelligent control of fermentation processes.

2. Fundamentals and Principles of the NIR Spectroscopic Technique

2.1. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

NIR spectroscopy is primarily based on the overtone and combination absorption vibrations of hydrogen-containing groups in molecules. The wavelength range of NIR spectroscopy typically spans from 780 to 2500 nm [22]. When a substance is exposed to NIR light, the photon energy is insufficient to cause electronic transitions but can excite chemical bonds such as C-H, O-H, and N-H from their ground state to higher vibrational energy levels [23]. These absorptions mainly correspond to overtones and combinations of fundamental molecular vibrations, which contain rich information about molecular structure and composition [24]. NIR spectroscopy produces weak and highly overlapping signals stemming from overtone and combination absorptions, leading to broad and complex spectra that are challenging to interpret directly [25]. It offers deep penetration capabilities and enables non-destructive analysis [26], as NIR light can traverse materials like glass or plastic, making it well-suited for non-invasive, real-time monitoring of fermentation processes. Its accuracy depends substantially on robust chemometric calibration models that relate complex spectral data to reference analytical measurements for reliable quantitative or qualitative assessment [25].

2.2. NIR Instrumentation

NIR spectrometers can be classified in several ways based on different criteria. Based on the type of physical contact between the probe and the fermentation medium, it can be primarily divided into two categories: non-insertion type and insertion type. Non-insertive type, also known as bypass analysis or transmissive detection, is characterized by the measurement components not making direct contact with the fermentation material. Typical methods involve diverting the fermentation broth through a circulation loop to an external flow-through cell, or directly measuring through a viewing window on the fermentation tank. The spectrometer and detector are positioned on opposite sides of the sample or window. Light passes through the sample or window to achieve a transmissive measurement of the material inside the tank.

For large-scale fermentation tanks, a diffuse reflection method can also be employed, where a probe is fixed on the tank’s viewing window to emit light and receive the diffuse reflected light returned from the material inside the fermenter. The NIR of insertive type is currently widely adopted in fermentation processes. Its core principle involves using a sturdy, immersible fiber optic probe that is inserted directly into the fermentation vessel, making direct contact with the fermentation material (such as mash or bacterial broth) for measurement. The main spectrometer unit transmits excitation light to the probe via a fiber optic cable. The tip of the probe is typically sealed with a sapphire window, which offers high optical transparency. After the light interacts with the sample, the signal light carrying information is returned through the optical fiber to the detector within the spectrometer. This method is primarily based on the principle of diffuse reflection, making it highly suitable for turbid fermentation systems. Non-insertive technology avoids direct contact with the sample, offering distinct advantages like high reliability and ease of maintenance. Its drawbacks, however, include potential measurement interference from viewing window cleanliness and, when using a bypass measurement setup, certain limitations like signal lag and reduced representativeness of the sample. In contrast, insertive NIR technology, which utilizes a fiber optic probe penetrating into the core of the fermentation reaction, enables highly representative, in situ and real-time monitoring. However, the probe faces challenges such as susceptibility to contamination and abrasion, as well as the need to withstand harsh sterilization conditions.

2.3. Chemometrics in NIR Spectroscopy

NIR spectroscopic data provides rich molecular physical and chemical information, alongside potential noise, irrelevant variables, nonlinearities, and latent features [22], and therefore the application of chemometrics is of vital importance. In general, chemometrics leverages multivariate analysis techniques to decipher complex spectral datasets [26]. In multivariate calibration, a calibration model is developed using a set of representative samples and is subsequently evaluated on an independent, unseen dataset to test its predictive ability. Therefore, the appropriate selection of samples for modeling is of paramount importance for building robust and accurate NIR calibration models.

For this reason, the performance of an NIR model is significantly enhanced by incorporating diverse samples that cover a wider quality range. In food fermentation applications, enhancing model performance entails selecting samples that represent variations in crucial factors such as raw material composition, microbial metabolic activity, fermentation stage, and end-product characteristics. These variations are best captured by a sample set that encompasses different raw material batches, fermentation time points, process parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen), and manufacturing lots. The resulting diversity within the sample set substantially strengthens the model’s reliability and applicability across varying fermentation conditions and production scales. The calibration set must encompass the entire expected range of the target indicators (e.g., substrate concentration, cell density, metabolite content). Its broad representativeness forms the foundation for the model’s robust generalization capability. In contrast, the validation set should consist of samples entirely independent of the calibration set, with the best practice being to collect them from different manufacturing lots or time points. This setup ensures the validation set effectively simulates the variability encountered in real-world applications, thereby providing an objective and unbiased assessment of the model’s predictive performance [22]. Many studies recommend that the calibration set should include at least 150–200 samples to ensure adequate model robustness and generalization [27,28,29]. Additionally, it is common practice to allocate approximately 20–30% of the total dataset to the validation set to ensure a reliable assessment of model performance [30,31]. The multivariate chemometric analysis of spectroscopic data involves several essential steps, ranging from spectral pretreatment and dimensionality reduction to feature selection, calibration model development, and validation [22], the flowchart is illustrated in Figure 2 This flow represents the fundamental workflow for building an NIR spectroscopic prediction model.

Figure 2.

Steps involved in constructing the NIR detection model.

2.4. Practical Implementation Challenges

In practical NIR spectroscopy applications, instrument drift, temperature effects, and probe-window fouling are critical factors that can significantly compromise spectral stability and model prediction performance, necessitating careful consideration during both modeling and deployment. Instrument drift, often caused by light-source aging, detector degradation, or optical component variations, introduces systematic shifts in baseline or intensity over time, which can gradually undermine quantitative accuracy. Regular calibration with reference standards and periodic model updates are essential to mitigate this issue. Temperature variations affect molecular vibrations and hydrogen bonding, leading to changes in absorption band positions and intensities. It is a particular challenge for in-line or field applications. To address this, robust calibration models should incorporate samples measured across a range of temperatures or employ algorithmic temperature correction techniques. Furthermore, probe-window fouling due to dust, moisture, or sample residue adds unwanted scattering and absorption artifacts, reduces signal-to-noise ratio, and can cause significant prediction errors. Routine cleaning and maintenance are therefore necessary, supplemented by real-time spectral monitoring methods to detect and flag anomalous measurements caused by contamination. In summary, proactively assessing and controlling these factors is essential for ensuring reliable NIR analytical results and facilitating the transition from laboratory research to robust industrial implementation.

3. Application of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Fermentation Process Monitoring

3.1. Sugar

Sugar content is a critical parameter in the food fermentation process. It is the main substrate for microorganisms’ growth and metabolism [32]. The concentration and consumption rate of sugars (e.g., glucose, fructose, sucrose, maltose) directly influence the growth kinetics of microorganisms, the production rate of target metabolites (e.g., ethanol, lactic acid, organic acids), and ultimately determine the fermentation efficiency and product quality. Therefore, real-time and accurate monitoring of sugar content is essential for precise process control and optimization.

NIR spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for monitoring sugar dynamics during fermentation due to its rapid, non-destructive, and multi-parameter analysis capabilities. The fundamental principle relies on the absorption of NIR light by C-H and O-H bonds present in sugar molecules. Therefore, NIR spectroscopy enables the rapid detection of sugar content during the fermentation process. Wang et al. utilized a spectral range of 12,000 to 4000 cm−1 to develop a PLSR model for sugar measurement in Kiwi wine Fermentation. After collecting 112 samples from the Kiwi wine fermentation process, the samples were scanned with Fourier transform-near-infrared mode in 12,000 to 4000 cm−1 nm, and the PLSR model was developed using pre-processed spectra. The coefficient of determination of prediction (R2p) was 0.975, and the root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) of 3.98 indicated that the developed prediction model is suitable for accurate sugar content prediction [33]. Additionally, Zhao et al. employed NIR spectroscopy for the online monitoring of total sugar content during kombucha fermentation. After evaluating both linear and non-linear multivariate calibration methods, their study demonstrated that a hybrid model combining Genetic Algorithm-based Partial Least Squares (GA-PLS) and Back-Propagation Artificial Neural Network (BPANN) yielded optimal predictive performance, achieving an R2p of 0.9437 and a root mean square error of RMSEP of 0.86 g/L [34]. This study is noteworthy for comparing linear and nonlinear methods and ultimately adopting a hybrid model. This suggests that in fermentation systems such as kombucha, which may involve diverse microbial composition and complex metabolic profiles, the relationship between sugar content changes and spectral responses may exhibit nonlinear characteristics. Therefore, incorporating nonlinear modeling approaches (e.g., BPANN) can help improve predictive performance. The hybrid strategy combining GA-PLS and BPANN essentially integrates the advantages of feature selection optimization and nonlinear fitting, providing an effective approach for handling complex fermentation systems. Similarly, Zhao et al. developed a model for reducing sugar content prediction of the solid-state fermentation process in the 950–1700 nm range [35]. They successfully developed a NIR spectroscopy prediction model based on Genetic Algorithm-based Adaptive Boosting (GA-AdaBoost). By employing a series of optimizations including outlier removal using the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) algorithm, spectral preprocessing via Standard Normal Variate transformation, and feature selection with a Genetic Algorithm (GA), the model achieved accurate prediction of reducing sugar content, with R2p of 0.978 and a RMSEP of 0.640 g/L [35]. These results indicated that the integration of multiple machine learning models offers greater robustness in characterizing the complex relationship between spectra and sugar content compared to dependence on a single model. Furthermore, the selection of model parameters, including the modeling spectral range and preprocessing techniques, is critical for balancing prediction accuracy with model robustness. Furthermore, a thorough understanding of how these factors influence model performance is imperative for selecting and optimizing the most suitable calibration model for predicting sugar content in diverse sample types. Recent studies on predicting sugar content using NIR spectroscopy are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Application of NIR spectroscopy for sugar content analysis.

3.2. Ethanol

Ethanol represents one of the most critical products and indicators in many fermentation processes, such as in the production of alcoholic beverages [43]. The concentration of ethanol directly determines the alcoholic strength of the final product, influences the extraction of compounds during maceration, and serves as a key indicator of the fermentation process. In the acetic acid fermentation process, as the main substrate [44], ethanol affects the final product’s acidity and the efficiency of the process. NIR spectroscopy is exceptionally well-suited for monitoring alcohols due to the strong absorption features of the O-H and C-H bonds within their molecular structure. These bonds produce characteristic overtone and combination bands in the NIR region, enabling quantitative analysis. Rapid determination technology enables real-time monitoring and control of ethanol content, which is essential for optimizing the fermentation processes of alcoholic beverages, Jiulao (The products of the alcoholic fermentation stage of cereal vinegar), and vinegar. It helps ensure that guaranteeing the quality, yield, and stability of the final product.

In recent years, in order to establish an ethanol quantification method during the alcohol fermentation process, Chen et al. collected 62 samples of the alcohol fermentation process with a concentration range of 1.40–8.00% (v/v). The raw spectral data, identified as optimal after comparing preprocessing techniques, were used with the random frog algorithm for wavelength selection to build a PLSR model. The model achieved an R2c of 0.9828 and an RMSEC of 0.25%. Its predictive stability was confirmed on 21 unknown samples, yielding an R2p of 0.9775 and an RMSEP of 0.27% [36]. This study achieved high predictive accuracy (R2p > 0.97). The close agreement between the performance metrics for the calibration and prediction sets (R2c and R2p, RMSEC and RMSEP) strongly indicates excellent model robustness and generalization capability, with no overfitting observed. This success can be largely attributed to the effective screening of feature wavelengths by the random frog algorithm. It demonstrates that building a stable predictive model through the screening of feature wavelengths to remove irrelevant information and noise is more effective than relying solely on complex nonlinear models. Additionally, Kasemsumran et al. also reported similar accuracy for ethanol prediction of pineapple vinegar production process with R2 of 0.978 and RMSE of 0.178 [45], they significantly improved the accuracy of the model by combining the SCARS model with the PLS model. Menozzi et al. employed a combination of spectral preprocessing techniques, including smoothing, the Standard Normal Variate transformation, and mean centering, to mitigate noise and scattering. By utilizing PLSR, they achieved rapid detection of ethanol content during red grape must fermentation. The established model demonstrated excellent performance, with an R2c of 0.989 and an RMSEC of 0.427. For the prediction set, the model achieved an R2p of 0.987 and RMSEP of 0.463 [46]. Furthermore, in order to enhance model performance and robustness, vector normalization was applied for spectral preprocessing. Subsequently, the wavelength intervals of 8454.9–7498.3 cm−1 and 4605.4–4242.9 cm−1 were identified as feature variables for the ethanol prediction model. The developed model demonstrated excellent performance: the predictive accuracy (R2p = 0.94) was slightly superior to the calibration accuracy (R2c = 0.92). Furthermore, the low error values (RMSEC = 3.15, RMSEP = 2.73) indicate that the model fully meets the requirements for practical detection [47]. The aforementioned studies have essentially established the fundamental capabilities for rapid ethanol detection during fermentation processes. The aforementioned studies, despite focusing on different fermentation systems (e.g., alcoholic beverages, vinegar, grape juice) and employing distinct technical emphases (such as wavelength selection, spectral preprocessing, and characteristic interval identification), have all achieved excellent predictive performance based on PLSR or optimized PLSR models. This collectively demonstrates the universality and technical maturity of NIR spectroscopy for the quantitative monitoring of ethanol during fermentation processes. The core challenge now is no longer whether detection is feasible, but rather how to maintain long-term, stable, and high model accuracy in more complex industrial field environments. Such as those involving temperature and humidity fluctuations, particulate interference, and batch-to-batch variations. Furthermore, the integration of NIR spectroscopy with complementary techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy, to construct a multimodal data analytics framework holds significant promise for substantially enhancing the prediction accuracy and reliability of ethanol levels in complex matrices. The table below summarizes select recent applications of NIR spectroscopy for monitoring ethanol in various fermentation processes, detailing different fermentation systems, modeling strategies, and key performance metrics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Application of NIR spectroscopy for ethanol content analysis.

3.3. Acids

Acids, such as lactic acid and acetic acid, are a key class of metabolites in food fermentation processes [8,44]. Their variety and concentration not only directly influence the flavor, texture, and stability of fermented foods but also serve as important indicators of microbial metabolic activity and fermentation progress. For instance, in acetic acid fermentation for cereal vinegar, the accumulation of lactic acid significantly affects its flavor and quality [8]. In contrast, acetic acid is the target product generated from the oxidation of ethanol, which affects the production efficiency [8]. In vegetable fermentation, lactic acid produced by lactic acid bacteria provides the characteristic sour flavor of fermented vegetables [51]. The acidic environment it creates inhibits spoilage and pathogenic bacteria [52], and also helps preserve the vegetable’s crispness. Furthermore, the total titratable acid is also a key indicator in the fermentation process, as it provides a more comprehensive measure of the microbial activity and acid production, reflecting the cumulative effect of all organic acids present. Therefore, real-time monitoring of acid content during the fermentation process is crucial for controlling the fermentation process and ensuring product consistency.

NIR spectroscopy can detect the specific overtone and combination absorptions of chemical bonds in organic acids. Despite weak and complex signals caused by peak overlap, quantitative data like sugars, ethanol, and water, quantitative data can be reliably obtained using advanced chemometrics. Kim et al. collected a total of 132 samples from Korean traditional rice wine, of which 105 were assigned to the calibration set and 27 to the prediction set for constructing the titratable acid contents model [42]. A systematic comparison of various spectral preprocessing methods was first conducted, which identified mean normalization as the optimal preprocessing technique for predicting titratable acid contents. Ultimately, a model for titratable acidity was established using PLSR. The model demonstrated excellent performance, achieving an R2c of 0.914 with a SEC of 0.036%, an R2v of 0.905 with a SEV of 0.038%, and an R2p of 0.882 with a SEP of 0.045% [42]. In another study, Affane et al. developed and validated a rapid, non-destructive quantitative detection method for DL-lactic acid and acetic acid content in kefir milk utilizing NIR spectroscopy [53]. In order to construct the NIR quantitative models, the authors employed enzymatic analysis as the reference method for determining DL-lactic acid content and gas chromatography as the reference standard for acetic acid quantification in kefir. Based on this reference data, a robust NIR prediction model for DL-lactic acid was successfully developed, which demonstrated excellent performance in cross-validation (R2 = 0.90). This indicates the model’s high accuracy and reliability, making it suitable for rapid screening in practical applications. In contrast, the NIR model for acetic acid performed poorly, achieving an external validation R2 of only 0.44, which fails to meet the requirements for quantitative analysis. This discrepancy may be attributed to factors such as the quantitative accuracy of the gas chromatography method, insufficient sample diversity, or the selection of spectral preprocessing techniques. In another study utilizing NIR spectroscopy to monitor the fermentation process of kefir, the prediction model for total acidity demonstrated good performance, with R2 values of 0.92 and 0.79 for the calibration set and validation set, respectively [54]. Furthermore, NIR Spectroscopy was employed for the rapid characterization and differentiation of goat milk kefir samples subjected to different heat treatments (raw vs. pasteurized milk) and fermentation times (0–48 h), demonstrating 90% accuracy in fermentation time classification, which highlights its potential as a fast and low-cost quality control tool [55].

Ye et al.conducted a systematic study demonstrating the considerable potential of FT-NIR spectroscopy combined with chemometrics for the simultaneous and rapid determination of multiple key quality parameters [48]. To develop a quantitative model for total acidity, the researchers collected NIR spectra from 380 apple wine samples representing diverse raw materials, nutritional conditions, and fermentation processes, thereby constructing a highly representative sample set. They employed PLSR and systematically optimized spectral preprocessing methods and feature wavelength selection. Ultimately, the resulting quantitative model for total acidity exhibited outstanding performance, achieving a coefficient of determination for R2p of 0.98 and an RMSEP as low as 0.02 [48]. This study serves as a successful example of applying NIR spectroscopy to monitor complex fermentation processes, demonstrating that through rigorous chemometric optimization, FT-NIR can effectively replace traditional time-consuming methods and become a powerful tool for online, real-time quality control in the modern brewing industry. Similar, in a pineapple vinegar production process, Kasemsumran et al. also reported acetic acid and caffeic acid prediction of fermentation process with R2 of 0.874 and 938 and RMSE of 0.137 and 0.637, respectively [45]. The following table (Table 3) provides a summary of selected recent applications of NIR spectroscopy in monitoring acid content across a range of fermentation processes, including specifics on the sample analyzed, the modeling strategies employed, and the corresponding key performance metrics. Furthermore, in a solid-state fermentation system, the total acid and non-volatile acid were also detected by NIR spectroscopy. The PLSR model for total acid content achieved an RMSEP of 0.0402 and an R2p of 0.9902; meanwhile, the model for non-volatile acid content yielded an RMSEP of 0.0286 and an R2p of 0.9556 [56]. The successful development of the acidity model in solid-state fermentation systems is particularly encouraging. Due to the widespread spatial heterogeneity of solid-state fermentation, parameters at the fermentation edges often fail to represent conditions inside the fermentation fermenter, which has traditionally been considered a greater challenge for spectroscopic analysis. The detection method based on homogenized samples by turning over the fermented material provides an effective approach to overcoming the inhomogeneity issues inherent in such systems. In summary, NIR spectroscopy has established itself as an effective tool for monitoring the dynamic changes in organic acids during fermentation. Future research will place greater emphasis on mitigating signal interference within complex matrices, such as through the development of more robust variable selection algorithms and deep learning models, to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness.

Table 3.

Application of spectroscopy technology for acid analysis.

3.4. Other Metabolites

In recent years, the functional compounds (such as polysaccharides, polyphenols, and polypeptides) in fermented food have attracted researchers. These compounds are essential functional constituents in fermented food, contributing to various health benefits such as enhanced immune function, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [61,62,63,64], and better nutrient absorption. The dynamic changes in the concentration of these bioactive compounds are closely tied to microbial metabolic activities and enzymatic reactions during fermentation, ultimately determining the health-promoting value of the final product [65,66]. Therefore, monitoring their levels is crucial for improving the quality of fermented foods.

Traditionally, the quantification of these functional compounds relies on complex, time-consuming chromatographic or spectrophotometric methods. NIR spectroscopy exhibits characteristic absorption peaks for the N-H, O-H, and C-H bonds of these components, enabling their quantitative detection using chemometric methods. Therefore, NIR spectroscopy offers a promising alternative due to its rapid and non-destructive nature. For instance, Ma et al. developed an online NIR spectroscopy method for rapid quantification of polysaccharides in Ganoderma spp. mycelia. By combining moving window partial least squares and interval partial least squares to optimize the spectral region (5268.8–4000 cm−1) and applying constant offset elimination for spectral preprocessing, they established a high-accuracy quantitative model with an R2 of 0.9779, facilitating non-destructive and efficient assessment during industrial fermentation [67]. Similarly, Guo et al. constructed a rapid quantitative approach for polysaccharides in Cordyceps militaris mycelia using NIR spectroscopy. Their method integrated Monte Carlo partial least squares (MCPLS) with moving window partial least squares to reliably identify outliers, select feature wavelengths, and build a robust quantitative model, providing an effective strategy for online and non-destructive polysaccharide monitoring in industrial settings [68]. In another study, Teng et al. established a high-precision NIR quantitative model for polysaccharide content in Paecilomyces hepiali mycelium. They employed MCPLS for outlier removal and calibration set selection, followed by feature wavelength optimization via a moving window radial basis function neural network, ultimately constructing a radial basis function neural network model that achieved a remarkable R2p value of 0.9850 [69]. Despite these advances, research on the rapid detection of polysaccharides during fermentation remains limited, with most existing studies confined to conventional fermentation systems such as Lentinula edodes and Glycyrrhiza [70,71]. This scarcity can be largely attributed to the inherent complexity of fermentation systems, which include microorganisms, substrates, metabolites, and dynamically shifting physicochemical conditions, posing significant challenges to the robustness, real-time capability, and in situ applicability of analytical techniques such as NIR spectroscopy.

In recent years, rapid detection of polyphenols and flavonoids by NIR spectroscopy has also been applied to food fermentation processes (Table 4). For example, tea, cocoa, wine, vinegar, etc. Liu et al. developed a rapid NIR spectroscopy-based method for polyphenols detection in Pu-erh tea fermentation [72]. By employing standard normal variate (SNV) preprocessing coupled with the competitive adaptive reweighted sampling (CARS) algorithm, they established an SNV-CARS-PLSR model that enables non-destructive, real-time prediction of total phenol content, demonstrating excellent performance [72]. In another mulberry vinegar study, Sedjoah et al. evaluated a miniaturized MEMS-NIR spectrometer against a conventional optical fiber instrument for total phenolic monitoring, finding that despite a lower cost, the MEMS-based system coupled with SNV-CARS-PLS yielded a comparable and robust prediction, highlighting its potential for affordable at-line fermentation monitoring [59]. In their evaluation of fair-trade cocoa beans from diverse geographical origins, Forte et al. reported that the prediction of total polyphenol content using portable and benchtop NIRS instruments was unsatisfactory (R2cv = 0.56, RP = 1.51), which was attributed to the limited variability in fermentation degrees among commercial samples and potential interference from high lipid content [73]. Moreover, Littarru et al. employed NIR spectroscopy combined with Principal Component Regression (PCR) to monitor phenolic compounds during wine fermentation. Their research demonstrated that while the model could achieve quantitative prediction of total polyphenols (with a maximum R2cv of 0.67) and specific individual phenolics in must, its overall predictive performance remained suboptimal [74]. Similarly, Alfieri et al. employed visible spectroscopy on fermenting musts combined with PCR to establish quantitative models for monitoring the total polyphenol index, tannins, and anthocyanin content; however, the predictive accuracy of the models was relatively low [75].

Table 4.

Application of spectroscopy technology for functional compounds analysis.

In another monitoring study focused on the theaflavin-to-thearubigin (TF/TR) ratio during the fermentation process of Congou black tea, researchers developed a rapid and non-linear predictive method based on NIR spectroscopy. The approach initially employed a combination of the Synergy Interval Partial Least-Squares (SI-PLS) and Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS) algorithms to efficiently screen 11 key wavelength variables critically associated with tea pigments from the full spectrum Utilizing these selected feature variables, the study constructed a novel non-linear prediction model integrating an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) with an Adaptive Boosting (ADABOOST) algorithm. The predictive performance of this model significantly surpassed that of traditional linear models and other non-linear models, achieving an R2p of 0.893 for the prediction set [76]. Data fusion could also be a method to improve model accuracy. For example, Wang et al. leveraged a data fusion strategy to integrate NIR spectroscopy and computer vision, effectively overcoming the inherent limitations in predictive accuracy of single sensors (R2P = 0.98, RMSEP = 0.76) and providing a viable solution for in situ, rapid, and high-precision monitoring of polyphenols in black tea processing [77]. Therefore, exploring more advanced machine-learning algorithms to enhance feature extraction and predictive accuracy and data fusion methods is crucial for driving breakthroughs in rapid detection technology. Furthermore, NIR spectroscopy is also used to monitor polypeptide content during fermentation processes. Xing et al. established a quantitative monitoring method for polypeptide content during the solid-state fermentation of rapeseed meal by employing FT-NIR spectroscopy combined with the iPLS chemometric algorithm, which demonstrated high predictive accuracy [78]. In summary, NIR spectroscopy has been successfully applied to monitor key parameters in a variety of fermentation systems, including vinegar, alcoholic beverages, and tea, etc. It demonstrates significant potential for replacing traditional, tedious chemical analyses due to its unique advantages of rapidity, non-destructiveness, and environmental friendliness. This capability extends from measuring basic components like sugars, ethanol, and organic acids to more complex functional constituents such as polysaccharides, polyphenols, and peptides. By employing appropriate spectral preprocessing and variable selection algorithms, researchers can establish robust linear or nonlinear calibration models. This enables the accurate quantitative determination of multiple components within complex fermentation matrices, thereby providing powerful technical support for precise control of fermentation processes and real-time quality assessment.

4. Toward Spectroscopy-Based Control: Advanced Fermentation Strategies

NIR spectroscopy holds unique advantages in the field of fermentation, including reagent-free analysis, high detection accuracy, notable cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness. Its non-destructive nature is particularly suitable for monitoring dynamic changes during fermentation processes, such as continuous observation of substrate conversion and metabolite generation within the fermentation system. With real-time feedback provided by NIR spectroscopy, it is possible to optimize fermentation process control, improve production efficiency, and promote the development of more efficient and sustainable food fermentation processes.

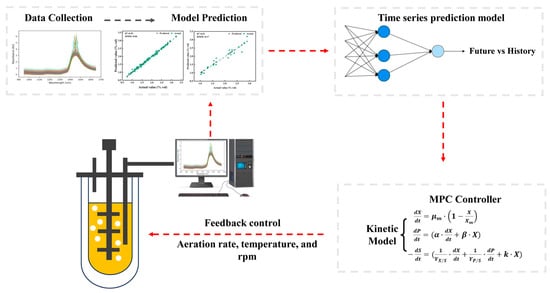

Food Fermentation processes exhibit significant nonlinear and time-delay characteristics. This means that the full impact of current manipulated variables, such as temperature and aeration rate, on key quality parameters like final product concentration will only manifest after a certain time delay. As such, relying solely on real-time feedback control is often insufficient for effective operation. In contrast, Model Predictive Control (MPC), as an advanced control strategy, is well-suited to address this challenge [79]. A soft sensor model can be developed based on NIR spectroscopy to estimate key quality variables in fermentation processes. This model utilizes easily accessible, real-time spectral data to infer or predict critical parameters that are difficult to measure online directly. The MPC controller leverages this process model together with the real-time predictions from the soft sensor. It not only considers the current system state but also anticipates process dynamics over a future horizon. Subsequently, an optimization algorithm computes a sequence of optimal adjustments to the manipulated variables, aiming to drive the predicted outputs as close as possible to the desired trajectory while satisfying all operational constraints (Figure 3). Schenk et al. investigated the application of economic nonlinear model predictive control in wine fermentation to optimize cooling energy consumption [80]. By employing an improved fermentation kinetic model integrated with parameter and state estimation, the strategy enabled real-time adjustment of the temperature control policy. Experiments conducted at Dienstleistungszentrum LandlicherRaum Mosel compared the traditional industrial controller with the MPC strategy. Results demonstrated that the MPC approach reduced energy consumption by approximately 52% without compromising wine quality and even achieved a superior flavor profile. This case confirms the effectiveness and economic benefits of MPC in nonlinear bioprocesses. Although the cited study did not explicitly employ NIR spectroscopy for monitoring sugar and ethanol levels, NIR spectroscopy is already capable of enabling in situ, real-time monitoring and prediction of these critical parameters [33,34]. This provides high-frequency, highly reliable feedback data for MPC, significantly improving the timeliness and accuracy of state and parameter estimation. Furthermore, emerging spectroscopic techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy, have considerable potential for non-destructive, dynamic tracking of microbial biomass and metabolic activity [81]. By integrating NIR or Raman or other spectroscopy information, it becomes feasible to construct a comprehensive process perception system that encompasses substrate consumption, product formation, and microbial status. Such integration would establish a robust data foundation and expanded optimization space, enabling more precise and highly adaptive MPC strategies for food fermentation processes. The effectiveness of MPC strategies is highly dependent on the accuracy of the process model and the timeliness of state estimation. Traditional mechanistic or linear statistical models often face limitations in predictive capability when dealing with the strong nonlinearity and batch-to-batch variations inherent in fermentation processes. This is precisely where artificial intelligence technologies can play a crucial role. Data-driven AI models, represented by deep learning, can directly learn and characterize complex nonlinear dynamic relationships from vast amounts of historical NIR spectral data and process parameters, thereby constructing more accurate prediction models than traditional methods. Such a fused “NIR-AI” soft sensor model can serve as a superior process model within MPC, significantly enhancing its ability to predict future states and making control decisions more proactive and precise. Furthermore, artificial intelligence can be applied to optimize the core components of MPC itself. For example, reinforcement learning algorithms can interactively learn with a process model (or a digital twin) to autonomously explore and discover optimal control strategies. They can even adapt to complex objectives that are difficult to describe with precise mathematical models, such as achieving the “optimal flavor profile.” This marks an evolution of control strategies from model-based optimization toward AI-enabled autonomous learning.

Figure 3.

The flowchart of MPC control for the fermentation process.

Prospectively, the fusion of NIR spectroscopy (as a source of real-time data) with digital twin and artificial intelligence technologies is set to propel the fermentation industry into the dawn of a fully intelligent age. A digital twin is a dynamically updated virtual mirror of a physical fermentation process constructed within the information space. It is not a static model but rather an integrated complex system that incorporates mechanistic models, data-driven models, and real-time data [82]. Recently, Zhao et al. developed a digital twin prediction and control system for kombucha fermentation. The system collects real-time multi-parameter data (such as bacterial concentration, carbon source levels, and pH) via IoT sensors, and employs multi-scale convolutional filters for feature extraction and fusion. A PLS prediction model was established to achieve high-precision forecasting of carbon source and bacterial concentration. Furthermore, genetic algorithm was integrated to enable multi-parameter optimization control of pH and dissolved oxygen. Experimental results demonstrated that this system significantly improves fermentation efficiency and process robustness, providing a feasible example for the digital and intelligent control of food fermentation processes [83]. Within this framework, NIR spectroscopy serves as the core data conduit, continuously feeding the digital twin with high-frequency, verifiable data on biochemical changes. This ensures the virtual model evolves in sync with the physical process, enabling real-time synchronization, high-fidelity simulation, and proactive prediction. Consequently, operators can conduct virtual experiments on the digital twin to test control strategies (e.g., temperature profiles, aeration profiles) and optimize parameters without risk or cost. Furthermore, the integration of NIR spectroscopy with process parameters (temperature, agitation rate, aeration rate) and even computer vision-based image information enables the construction of soft sensors that far exceed the capabilities of any single data source. These advanced sensors can accurately infer key variables that are difficult to measure online directly, such as cell viability and specific enzyme activity, thereby providing a more comprehensive basis for decision-making in process control. Furthermore, combining reinforcement learning and other algorithms, an AI system can autonomously learn and evolve optimal control strategies through interaction with the digital twin. Based on real-time NIR data and process states, the system can dynamically adjust setpoints to steer the fermentation process consistently toward predefined optimal targets (such as maximum yield or an ideal flavor profile). This approach ultimately leads to the achievement of a highly autonomous “Smart Fermentation Plant”. However, the widespread adoption and deeper integration of this technology in practical industrial settings still face several challenges:

(1) Model Universality and Transferability: Calibration models developed for a specific production line or reactor may experience performance degradation when raw material batches are changed, equipment is replaced, or production is scaled up. Developing effective strategies for model transfer and updating is a crucial direction for future research.

(2) Accurate Detection in Complex Matrices: In solid-state fermentation or viscous fermentation systems containing a high concentration of suspended particles and cells, severe light scattering effects, low target analyte concentrations, and significant background interference pose greater demands on the prediction accuracy and robustness of the models.

(3) Hardware Costs and System Integration: The initial investment for high-performance online NIR spectrometers and their associated sampling systems (such as durable immersion probes) is relatively high. Furthermore, their seamless integration with existing fermentation equipment requires specialized engineering expertise.

(4) Dependence on Specialized Expertise: Establishing and maintaining high-performance NIR models requires interdisciplinary talent proficient in spectroscopy, chemometrics, and fermentation process knowledge. This reliance on specialized skills somewhat limits the technology’s widespread application.

5. Conclusions

NIR spectroscopy has become an indispensable and powerful tool in modern food fermentation process analysis and control, owing to its unique advantages of rapid, non-destructive, multi-component simultaneous analysis, and suitability for online monitoring. This review systematically elaborates on its fundamental principles, instrument configuration, and key chemometric methodologies while providing a detailed retrospective of its successful applications in monitoring sugars, ethanol, acids, and other functionally active compounds. More importantly, we emphasize the critical role of NIR spectroscopy as a core enabling component within advanced fermentation strategies, such as real-time feedback control and model predictive control. Ultimately, this review paves a solid technical pathway toward precise control and intelligent transformation of fermentation processes. In the future, integrating a recommended flux for implementing NIR in the fermentation process serve as a theoretical foundation for integrating NIR with predictive control. However, the application of NIR spectroscopy in the fermentation industry often results in instability due to batch-to-batch variations. Therefore, the mutual calibration between offline testing and online monitoring is also of significant importance for fermentation process control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. (Chao Yu) and X.Y.; methodology, M.Y.; software, C.Y. (Chenyu Yang); validation, B.G. and M.Y.; formal analysis, C.Y. (Chenyu Yang); investigation, C.Y. (Chao Yu); resources, Y.Z. and J.X.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.S.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, M.W.; project administration, J.S.; funding acquisition, J.S. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2025YFF1107305), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472321), Innovative Research Team of Shanxi Province, Key Technology Research Project of Taiyuan (2024TYJB0146), Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (25JJJJC0021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singh, A.; Kumar, S. Exploring the Functionality of Microbes in Fermented Foods: Technological Advancements and Future Directions. Fermentation 2025, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplice, E.; Fitzgerald, G.F. Food fermentations: Role of microorganisms in food production and preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999, 50, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhikh, S.; Kalashnikova, O.; Ivanova, S.; Prosekov, A.; Krol, O.; Kriger, O.; Fedovskikh, N.; Babich, O. Evaluating the Influence of Microbial Fermentation on the Nutritional Value of Soybean Meal. Fermentation 2022, 8, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.A.L.; de Alencar, E.R.; Chiarello, M.D.; de Oliveira, L.D. Unraveling the impact of coffee fermentation: Inter-actions among processing variables and their effects on sensory quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Han, P.C.; Zhang, P.P.; Li, Y.K. Influence of yeast concentrations and fermentation durations on the physical properties of white bread. LWT 2024, 198, 116063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.F.; Wang, J.C.; Shen, J.; Kang, N.; Chai, Y.W.; Gao, Y.; Fan, Z.X.; Fang, Z.F.; Li, B.K.; Yang, B. Effect of mixed fermentation with L. paracasei SMN-LBK and L. reuteri LBK on the taste formation of Kazak cheese based on metabolomics. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, S.J.; Liu, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, D.H. Effect of salt concentration on Chinese soy sauce fermentation and characteristics. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, W.Q.; Guo, X.R.; Wang, J.; Liang, K.; Zhou, Y.A.; Lang, F.F.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, M. Sequential bio-augmentation of the dominant microorganisms to improve the fermentation and flavor of cereal vinegar. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, F.Y.; Ye, J.X.; Wang, J.C. A bilevel approach to biobjective inverse optimal control of nonlinear fermentation system with uncertainties. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 146, 108780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.B.; Li, H.D.; Dong, S.M.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.K.; Huang, R.N.; Han, S.N.; Hou, J.G.; Pan, C.M. Dynamic changes and correlations of microbial communities, physicochemical properties, and volatile metabolites during Daqu fermentation of Taorong-type Baijiu. LWT 2023, 173, 114290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Lu, Z.M.; Zhang, X.J.; Wang, Z.M.; Yu, Y.J.; Shi, J.S.; Xu, Z.H. Metagenomics reveals flavour metabolic network of cereal vinegar microbiota. Food Microbiol. 2017, 62, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasche, S.; Kim, Y.; Mars, R.A.T.; Machado, D.; Maansson, M.; Kafkia, E.; Milanese, A.; Zeller, G.; Teusink, B.; Nielsen, J. Metabolic cooperation and spatiotemporal niche partitioning in a kefir microbial community. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.L.; Li, Y.B.; Zhao, H.Y.; Liu, X.G.; Ding, H.L.; Ding, Q.S.; Ma, D.N.; Liu, S.P.; Mao, J. Application of computer vision techniques to fermented foods: An overview. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 160, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, K.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Jayaraman, G.; Bhatt, N. Model maintenance, monitoring, and control framework using In-Situ NIR spectroscopy and offline process data for Lactococcus lactis fermentation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende-Prieto, C.; Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P.; Martínez, B.; Rodríguez, A.; García, P.; Fernández, L. Qualitative analysis of yogurt using VIS-NIR spectroscopy simultaneously allows prediction of the animal origin of milk as well as monitoring of pH and viscosity during yogurt production. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 144, 107689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, Z.H.; Huang, X.W.; Shi, J.Y.; Zou, X.B.; Zhang, S.Y.; Shen, C.H.; Wang, S.T.; Hu, Y.X.; Wang, Q. NIR-based chemometric modeling for fermentation round classification and physicochemical indicator prediction during stacking fer-mentation of sauce-flavor Baijiu. Food Biosci. 2025, 73, 107680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoche, S.; Krause, D.; Hussein, M.A.; Becker, T. Ultrasound-based, in-line monitoring of anaerobe yeast fermentation: Model, sensor design and process application. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.Y.; O’Donnell, C.; Tobin, J.T.; O’Shea, N. Review of near-infrared spectroscopy as a process analytical technology for real-time product monitoring in dairy processing. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 103, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, L.Q.; Shen, S.S.; Deng, W.W.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Ning, J.M. Intelligent evaluation of black tea fermentation degree by FT-NIR and computer vision based on data fusion strategy. LWT 2020, 125, 109216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Alamprese, C.; Bono, V.; Picozzi, C.; Foschino, R.; Casiraghi, E. Monitoring of lactic acid fermentation process using Fourier transform near infrared spectroscopy. J. Near Infrared Spec. 2013, 21, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Z.; Long, J.; Xu, E.; Wu, C.S.; Wang, F.; Xu, X.M.; Jin, Z.Y.; Jiao, A.Q. Application of FT-NIR spectroscopy and FT-IR spectroscopy to Chinese rice wine for rapid determination of fermentation process parameters. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 2726–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.W.; Singh, V.; Kamruzzaman, M. Near-infrared spectroscopy as a green analytical tool for sustainable biomass characterization for biofuels and bioproducts: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 433, 132722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Kulieva, V.; Quijano-Jara, C.; Avila-George, H.; Castro, W. Predicting the evolution of pH and total soluble solids during coffee fermentation using near-infrared spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepper-Davidsen, J.; Magnusson, M.; Lawton, R.J.; Fletcher, D.; Holmes, G.; Glasson, C.R.K. Chemometric models for high-throughput biomass grading of the kelp Ecklonia radiata, using mid-infrared (MIR) and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy. Algal Res. 2024, 77, 103352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciza, P.H.; Sacre, P.Y.; Waffo, C.; Kimbeni, T.M.; Masereel, B.; Hubert, P.; Ziemons, E.; Marini, R.D. Comparison of several strategies for the deployment of a multivariate regression model on several handheld NIR instruments. Application to the quality control of medicines. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 215, 114755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabood, F.; Jabeen, F.; Ahmed, M.; Hussain, J.; Al Mashaykhi, S.A.A.; Al Rubaiey, Z.M.A.; Farooq, S.; Boqué, R.; Ali, L.; Hussain, Z.; et al. Development of new NIR-spectroscopy method combined with multivariate analysis for detection of adulteration in camel milk with goat milk. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awhangbo, L.; Severac, M.; Charnier, C.; Latrille, E.; Steyer, J. Rapid characterization of sulfur and phosphorus in organic waste by near infrared spectroscopy. Waste Manag. 2024, 176, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goñi, A.M.; Fernández, J.A.; Demarco, P.A.; Secchi, M.A.; Carcedo, A.J.P.; Ciampitti, I.A. Determination of water-soluble carbohydrates by near-infrared spectroscopy for canola, maize, and sorghum stem fractions. Spectrochim. Acta A 2024, 304, 123320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malai, C.; Maraphum, K.; Saengprachatanarug, K.; Wongpichet, S.; Phuphaphud, A.; Posom, J. Effective measurement of starch and dry matter content in fresh cassava tubers using interactance Vis/NIR spectra. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 125, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Li, J.H.; Guo, G.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, S.Z.; Xie, G.H. How to divide diverse biomass samples to build near-infrared spectroscopy models for gross calorific value. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2024, 14, 17941–17953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Posom, J.; Sirisomboon, P.; Shrestha, B.P. Comprehensive Assessment of Biomass Properties for Energy Usage Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Spectral Multi-Preprocessing Techniques. Energy 2023, 16, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viesser, J.A.; Pereira, G.V.D.; Neto, D.P.D.; Rogez, H.; Góes-Neto, A.; Azevedo, V.; Brenig, B.; Aburjaile, F.; Soccol, C.R. Co-culturing fructophilic lactic acid bacteria and yeast enhanced sugar metabolism and aroma formation during cocoa beans fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 339, 109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.Q.; Peng, B.Z. A Feasibility Study on Monitoring Residual Sugar and Alcohol Strength in Kiwi Wine Fermentation Using a Fiber-Optic FT-NIR Spectrometry and PLS Regression. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.G.; Adade, S.Y.S.S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.Z.; Jiao, T.H.; Li, H.H.; Chen, Q.S. On-line monitoring of total sugar during kombucha fermentation process by near-infrared spectroscopy: Comparison of linear and non-linear multiple calibration methods. Food Chem. 2023, 423, 136208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Sun, A.; He, S.Y.; Yu, L.S.; Wang, R.X.; Fu, W.J.; Mu, Y. Quantitative analysis of reducing sugars in solid-state fermentation based on NIR combined with GA-AdaBoost. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 2262–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Zhu, S.H.; Cui, P.J.; Lei, H.; Yan, H. Detection of the alcohol fermentation process in vinegar production with a digital micro-mirror based NIR spectra set-up and chemometrics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaglia, J.; Giussani, B.; Mestres, M.; Puxeu, M.; Busto, O.; Ferré, J.; Boqué, R. Early detection of undesirable deviations in must fermentation using a portable FTIR-ATR instrument and multivariate analysis. J. Chemom. 2019, 33, e3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Wu, Q.F.; Wei, Y.Q.; Liu, X.; Tang, P.A. Evaluation of near-infrared and mid-infrared spectroscopy for the de-termination of routine parameters in Chinese rice wine. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Zhao, J.W.; Pan, W.X.; Chen, Q.S. Real-time monitoring of process parameters in rice wine fermentation by a portable spectral analytical system combined with multivariate analysis. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Amigo, J.M.; Lyndgaard, C.B.; Foschino, R.; Casiraghi, E. Beer fermentation: Monitoring of process parameters by FT-NIR and multivariate data analysis. Food Chem. 2014, 155, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Novales, J.; López, M.I.; Sánchez, M.T.; García, J.A.; Morales, J. A feasibility study on the use of a miniature fiber optic NIR spectrometer for the prediction of volumic mass and reducing sugars in white wine fermentations. J. Food Eng. 2008, 89, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Cho, B.K. Rapid monitoring of the fermentation process for Korean traditional rice wine ‘Makgeolli’ using FT-NIR spectroscopy. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2015, 73, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Galli, E.; Agarbati, A.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Starmerella bombicola and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Wine Se-quential Fermentation in Aeration Condition: Evaluation of Ethanol Reduction and Analytical Profile. Foods 2021, 10, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.A.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.Y.; Liang, K.; Lang, F.F.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, M. Impact of spatial het-erogeneity on fermentation characteristics of cereal vinegar: A comparison of manual and mechanical methods. LWT 2025, 217, 117415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsumran, S.; Boondaeng, A.; Jungtheerapanich, S.; Ngowsuwan, K.; Apiwatanapiwat, W.; Janchai, P.; Vaithanomsat, P. Assessing Fermentation Broth Quality of Pineapple Vinegar Production with a Near-Infrared Fiber-Optic Probe Coupled with Stability Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling. Molecules 2023, 28, 6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menozzi, C.; Foca, G.; Calvini, R.; Catellani, L.; Bezzecchi, A.; Ulrici, A. Comparison of Different Spectral Ranges to Monitor Alcoholic and Acetic Fermentation of Red Grape Must Using FT-NIR Spectroscopy and PLS Regression. Food Anal. Methods 2024, 17, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanomsophon, T.; Sirisomboon, P.; Lapcharoensuk, R.; Shrestha, B.; Krusong, W. Evaluation of acetic acid and ethanol concentration in a rice vinegar internal venturi injector bioreactor using Fourier transform near infrared spectroscopy. J. Near Infrared Spec. 2019, 27, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.Q.; Yue, T.L.; Yuan, Y.H.; Li, Z. Application of FT-NIR Spectroscopy to Apple Wine for Rapid Simultaneous De-termination of Soluble Solids Content, pH, Total Acidity, and Total Ester Content. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2014, 7, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.Z.; Ge, N.; Cui, L.; Zhao, H. Monitoring of alcohol strength and titratable acidity of apple wine during fermentation using near-infrared spectroscopy. LWT 2016, 66, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Egidio, V.; Sinelli, N.; Giovanelli, G.; Moles, A.; Casiraghi, E. NIR and MIR spectroscopy as rapid methods to monitor red wine fermentation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 230, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; He, Z.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhao, M.W.; Cao, X.Y.; Lin, X.P.; Ji, C.F.; Zhang, S.F.; Liang, H.P. Improving the quality of Suancai by inoculating with Lactobacillus plantarum and Pediococcus pentosaceus. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.Z.; Yang, Y.T.; Xiao, L.L.; Qu, L.B.; Zhang, X.L.; Wei, Y.J. Advancing Insights into Probiotics during Vegetable Fermentation. Foods 2023, 12, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affane, A.L.N.; Fox, G.P.; Sigge, G.O.; Manley, M.; Britz, T.J. Quantitative analysis of DL-lactic acid and acetic acid in Kefir using near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. J. Near Infrared Spec. 2009, 17, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affane, A.L.N.; Fox, G.P.; Sigge, G.O.; Manley, M.; Britz, T.J. Simultaneous prediction of acidity parameters (pH and titratable acidity) in Kefir using near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, R.; Terriente-Palacios, C.; García-Olmo, J.; Osorio, S.; Rodríguez-Ortega, M.J. Combined Metabolomic and NIRS Analyses Reveal Biochemical and Metabolite Changes in Goat Milk Kefir under Different Heat Treatments and Fermentation Times. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.W.; Pan, T.H.; Li, G.Q. Evaluation of the physicochemical content and solid-state fermentation stage of Zhenjiang aromatic vinegar using near-infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Food Eng. 2020, 16, 20200127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Z.; Xu, E.B.; Wang, F.; Long, J.; Xu, X.M.; Jiao, A.Q.; Jin, Z.Y. Rapid Determination of Process Variables of Chinese Rice Wine Using FT-NIR Spectroscopy and Efficient Wavelengths Selection Methods. Food Anal. Methods 2015, 8, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.B.; Ding, W.W.; Jia, P.F.; Che, Z.M.; Liu, P. Fermentation process monitoring of broad bean paste quality by NIR combined with chemometrics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 16, 2929–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedjoah, R.C.A.A.; Ma, Y.; Xiong, M.; Yan, H. Fast monitoring total acids and total polyphenol contents in fermentation broth of mulberry vinegar using MEMS and optical fiber near-infrared spectrometers. Spectrochim. Acta A 2010, 30, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krähmer, A.; Engel, A.; Kadow, D.; Ali, N.; Umaharan, P.; Kroh, L.W.; Schulz, H. Fast and neat—Determination of bio-chemical quality parameters in cocoa using near infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2015, 181, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, K.M.; Zannini, E.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K. Lactic Acid Bacteria Exopolysaccharides in Foods and Beverages: Isola-tion, Properties, Characterization, and Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. T 2018, 9, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.R.; Sui, Y.; Li, S.Y.; Shi, J.B.; Cai, S.; Xiong, T.; Cai, F.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, S.N.; Mei, X. Phenolic Profile and Bioactivity Changes of Lotus Seedpod and Litchi Pericarp Procyanidins: Effect of Probiotic Bacteria Biotransformation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwole, O.; Fernando, W.M.A.D.B.; Lumanlan, J.; Ademuyiwa, O.; Jayasena, V. Role of phenolic acid, tannins, stilbenes, lignans and flavonoids in human health—A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 6326–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.F.; Li, Y.W.; Ye, Z.H.; Lin, H.B.; Yang, K. Overview of the preparation method, structure and function, and application of natural peptides and polypeptides. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meini, M.R.; Cabezudo, I.; Galetto, C.S.; Romanini, D. Production of grape pomace extracts with enhanced antioxidant and prebiotic activities through solid-state fermentation by Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus oryzae. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartik, M.; Liu, J.; Mohedano, M.T.; Mao, J.W.; Chen, Y. Optimizing yeast for high-level production of kaempferol and quercetin. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.H.; He, H.Q.; Wu, J.Z.; Wang, C.Y.; Chao, K.L.; Huang, Q. Assessment of Polysaccharides from Mycelia of genus Ganoderma by Mid-Infrared and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Lu, J.H.; Song, J.; Wang, D.; Teng, L.R. Application of Near Infrared Spectroscopy in Screening Cordyceps Militaris Mutation Strains and Optimizing Their Fermentation Process. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2010, 30, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, W.Z.; Song, J.; Meng, F.X.; Meng, Q.F.; Lu, J.H.; Hu, S.; Teng, L.R.; Wang, D.; Xie, J. Study on the Detection of Active Ingredient Contents of Paecilomyces hepiali Mycelium via Near Infrared Spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2014, 34, 2645–2651. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.H.; Yun, Y.H.; Fan, W.; Liang, Y.Z.; Yu, Y.; Tang, W.X. Rapid analysis of polysaccharides contents in Glycyrrhiza by near infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Gao, X.K.; Wang, R.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.Y.; Huang, Q. Evaluation of Polysaccharide Content in Shiitake Culi-nary-Medicinal Mushroom, Lentinula edodes (Agaricomycetes), via Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Integrated with Deep Learning. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2023, 25, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, R.X.; Shi, D.L.; Cao, R.Y. Non-destructive prediction of tea polyphenols during Pu-erh tea fermentation using NIR coupled with chemometrics methods. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 131, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, M.; Currò, S.; Van de Walle, D.; Dewettinck, K.; Mirisola, M.; Fasolato, L.; Carletti, P. Quality Evaluation of Fair-Trade Cocoa Beans from Different Origins Using Portable Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS). Foods 2023, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littarru, E.; Modesti, M.; Alfieri, G.; Pettinelli, S.; Floridia, G.; Bellincontro, A.; Sanmartin, C.; Brizzolara, S. Optimizing the winemaking process: NIR spectroscopy and e-nose analysis for the online monitoring of fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, G.; Modesti, M.; Bellincontro, A.; Renzi, F.; Aleixandre-Tudo, J.L. Feasibility assessment of a low-cost visible spec-troscopy-based prototype for monitoring polyphenol extraction in fermenting musts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.W.; Li, J.; Wang, J.J.; Liang, G.Z.; Jiang, Y.W.; Yuan, H.B.; Yang, Y.Q.; Meng, H.W. Rapid determination by near infrared spectroscopy of theaflavins-to-thearubigins ratio during Congou black tea fermentation process. Spectrochim. Acta A 2018, 205, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.J.; Li, L.Q.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Q.Q.; Ning, J.M.; Zhang, Z.Z. Enhanced quality monitoring during black tea processing by the fusion of NIRS and computer vision. J. Food Eng. 2021, 304, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Hou, X.S.; Tang, Y.X.; He, R.H.; Mintah, B.K.; Dabbour, M.; Ma, H.L. Monitoring of polypeptide content in the solid-state fermentation process of rapeseed meal using NIRS and chemometrics. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, e12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shahzad, M.; Zhu, X.L.; Rehman, K.U.; Uddin, S. A Non-linear Model Predictive Control Based on Grey-Wolf Optimization Using Least-Square Support Vector Machine for Product Concentration Control in l-Lysine Fermentation. Sensors 2020, 20, 3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, C.; Schulz, V.; Rosch, A.; von Wallbrunn, C. Less cooling energy in wine fermentation—A case study in mathematical modeling, simulation and optimization. Food Bioprod. Process 2017, 103, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzurendova, S.; Olsen, P.M.; Byrtusova, D.; Tafintseva, V.; Shapaval, V.; Horn, S.J.; Kohler, A.; Szotkowski, M.; Marova, I.; Zimmermann, B. Raman spectroscopy online monitoring of biomass production, intracellular metabolites and carbon substrates during submerged fermentation of oleaginous and carotenogenic microorganisms. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dazzarola, C.; Tighe, R.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Saa, P.A. Toward a digital twin for beer quality control: Development of a digital model integrating industrial process data and model-based fermentation descriptors. J. Food Eng. 2026, 403, 112726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.G.; Jiao, T.H.; Adade, S.Y.S.S.; Zhen, W.; Qin, O.Y.; Chen, Q.S. Digital twin for predicting and controlling food fermentation: A case study of kombucha fermentation. J. Food Eng. 2025, 393, 112467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.