Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of different bentonite levels on the fermentation profile, losses, microbial populations, aerobic stability, and chemical composition of corn silage. A 5 × 3 factorial completely randomized design was used, with five bentonite inclusion levels (0, 20, 40, 60, and 80 g/kg) and three storage times (30, 90, and 180 days), with four repetitions. Significant additive × storage time interactions were detected for key parameters. After 180 days, pH increased to 4.20 at 80 g/kg bentonite, while lactic acid peaked at 54.02 g/kg DM with 60 g/kg at 90 days. Acetic acid reached 22.36 g/kg DM at 180 days, and lactic acid bacteria ranged from 3.42 to 7.43 log CFU/g. Yeast counts were lowest (≤0.57 log CFU/g) at 180 days with 20–60 g/kg bentonite. Dry matter rose to 311 g/kg with 60 g/kg bentonite, whereas soluble carbohydrates decreased from 123.9 to 68.2 g/kg DM. Aerobic stability markedly improved, reaching 142.06 h with 40 g/kg bentonite at 180 days, almost three times higher than the control. The inclusion of bentonite in corn silage at levels of 20–60 g/kg of fresh matter effectively enhances silage quality during 180 days of storage by improving fermentation characteristics, microbial stability, and aerobic stability.

1. Introduction

Corn (Zea mays L.) is one of the most important forage crops used in ruminant production systems due to its high dry matter (DM) yield, energy density, and digestibility, which directly contribute to animal performance and production efficiency. Ensiling corn is a widespread conservation strategy that allows the preservation of its nutritive value during periods of forage shortage, ensuring a stable and continuous energy supply throughout the year. Corn should ideally be harvested at 300–350 g/kg DM to achieve optimal fermentation and minimize nutrient losses [1,2]. At this stage, the balance between soluble carbohydrates and moisture supports rapid fermentation dominated by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), leading to stable silage with low pH and reduced spoilage.

However, even under recommended DM levels, excessive effluent and undesirable fermentations can occur under specific conditions. Immature harvests, high rainfall at harvest, compacted or poorly drained soils, or delayed field operations can lead to excess plant moisture [3]. This results in the leaching of soluble nutrients, increased effluent losses, and a higher risk of clostridial fermentation. Furthermore, the high concentration of readily fermentable carbohydrates in corn silage, while beneficial for lactic fermentation, also favors the growth of undesirable microorganisms such as yeasts and molds. These organisms consume residual sugars and organic acids, increasing pH and reducing aerobic stability during feed-out [4,5]. The resulting deterioration compromises palatability, nutritive value, and intake, leading to economic and productive losses.

In this context, the use of additives has become a fundamental strategy to optimize fermentation, improve stability, and preserve silage quality. Additives may act through various mechanisms, including moisture regulation, microbial modulation, or the enhancement of fermentation end products. Among the alternatives available, bentonite has recently gained attention as a natural, low-cost, and environmentally safe additive. Bentonite is a clay mineral derived from volcanic ash, primarily composed of montmorillonite, belonging to the smectite group [6]. Its layered crystalline structure, large surface area, and high cation exchange capacity (CEC) confer it remarkable absorptive and adsorptive properties. Depending on its predominant exchangeable cation, bentonite is classified as sodium or calcium type, each exhibiting distinct swelling and moisture-binding characteristics [7,8].

These physicochemical features make bentonite particularly interesting for silage applications. Its high water-holding capacity helps to absorb excess moisture and reduce effluent losses in wet silages. Additionally, its buffering capacity can moderate the rate of acidification, maintaining pH levels that favor the proliferation of beneficial LAB while suppressing the growth of spoilage organisms such as yeasts, enterobacteria, and filamentous fungi [9]. The mineral matrix of bentonite may also adsorb microbial toxins, organic acids, and oxygen, contributing to a more stable anaerobic environment. Such effects can slow down the onset of aerobic deterioration once the silo is opened, thereby extending the aerobic stability of the silage [10].

From a microbiological standpoint, bentonite can indirectly modulate the fermentation microbiota. By creating a less favorable environment for spoilage microorganisms and stabilizing fermentation pH, bentonite promotes the dominance of lactic acid-producing bacteria over competing species. This balance contributes to greater production of lactic and acetic acids, improved preservation of dry matter, and enhanced resistance to aerobic spoilage [11]. These effects are particularly valuable in tropical and subtropical climates, where silages are frequently exposed to higher temperatures that accelerate microbial degradation and shorten aerobic stability.

In addition to its functional role in silage, bentonite presents several practical advantages. It is widely available, inexpensive, non-corrosive, and easy to apply. Unlike many synthetic additives, it poses no risks to animal or human health and aligns with sustainable livestock management practices [12]. The use of bentonite also reduces dependence on imported or high-cost chemical preservatives, making it a cost-effective alternative for farmers in developing regions.

Previous studies have reported promising outcomes from bentonite inclusion in silages of varying moisture content. Khorvash et al. [13] observed that 1% bentonite reduced effluent losses in low-DM corn silages. Everson et al. [14] found that bentonite inclusion affected fermentation dynamics by increasing lactic acid concentrations and stabilizing pH, while Fransen and Strubi [15] reported reduced effluent losses in grass silages treated with bentonite. Although these studies indicate that bentonite improves moisture control and fermentation balance, little is known about its effects on microbial populations, fermentation products, and aerobic stability in corn silage stored over extended periods under conventional DM levels.

Therefore, the central hypothesis of this study is that the inclusion of bentonite in corn silage can beneficially modulate the fermentation process over the storage period, regulating pH, adsorbing excess moisture and microbial metabolites, suppressing spoilage microorganisms, and improving aerobic stability, even when the silage is produced within the recommended dry matter range.

Accordingly, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of different bentonite inclusion levels and storage times on the fermentation profile, microbial populations, ensiling losses, chemical composition, organic acid concentrations, and aerobic stability of corn silage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location and Climate

The field experiment was conducted in the municipality of São José dos Cordeiros, Paraíba, Brazil (07°23′00″ S, 36°48′00″ W; altitude 529 m), at João Marcos Farm, during the rainy season of 2022. The region is classified as BSh (hot semiarid) according to Köppen and Geiger, characterized by irregular rainfall concentrated between February and June and a prolonged dry period from July to January. The mean annual precipitation is approximately 551.7 mm, and the mean air temperature is 23 °C [16].

After harvesting, the forage was transported to the Forage Sector of the Department of Animal Science, Center for Agricultural Sciences, Federal University of Paraíba (CCA–UFPB), located in Areia, Paraíba (06°58′00″ S, 35°42′00″ W; altitude 619 m), where the processing, ensiling, and laboratory analyses were performed.

2.2. Soil Analysis and Crop Management

Before planting, composite soil samples (0–20 cm layer) were collected from the experimental field for chemical and physical characterization. Analyses were performed at the Soil Laboratory of CCA–UFPB, following the methodologies described by Donagema [17]. The results were as follows: pH (H2O): 7.7; Organic matter: 21.2 g/kg; P (Mehlich-1): 81.5 mg/dm3; K+: 647.99 mg/dm3; Ca2+: 5.80 cmolc/dm3; Mg2+: 3.00 cmolc/dm3; Al3+: 0.05 cmolc/dm3; H+ + Al3+: 0.00 cmolc/dm3; CEC (cation exchange capacity): 8.85 cmolc/dm3; Base saturation (V%): 100%; Soil texture: sandy loam (71% sand, 18% silt, 11% clay).

The results indicate a high base saturation and low acidity, typical of soils under semiarid conditions. Based on soil analysis and technical recommendations for corn fertilization under semiarid conditions, no liming was required. Fertilization followed the guidelines proposed by Donagema [17] for corn grown in Northeast Brazil, applying 80 kg N, 60 kg P2O5, and 40 kg K2O per hectare. Nitrogen was supplied as urea (45% N) in two equal applications: half at planting and half at 30 days after emergence. Phosphorus and potassium were supplied as single superphosphate and potassium chloride, respectively, incorporated into the planting furrow.

Manual weeding was performed twice, and no irrigation or pest control was required during crop development, as rainfall during the growing period was sufficient to ensure normal plant growth.

After harvest, representative samples of the chopped forage were collected for determination of dry matter and chemical composition, prior to the ensiling process.

2.3. Experimental Design

The experiment followed a completely randomized 5 × 3 factorial design, consisting of five bentonite inclusion levels (0, 20, 40, 60, and 80 g/kg of fresh matter- FM) and three storage times (30, 90, and 180 days), with four replications per treatment, totaling 60 experimental units. Considering the average dry matter (DM) content of the fresh corn forage (approximately 320 g/kg FM), the corresponding bentonite doses on a dry matter basis were 0, 62.5, 125, 187.5, and 250 g/kg DM, respectively.

Creole corn (Zea mays L.) was manually sown in March 2022 in furrows 5 cm deep, using a spacing of 0.8 m between rows and 0.5 m between plants, resulting in an approximate population density of 25,000 plants/ha. The experimental area covered 3 hectares. Harvesting was performed manually 70 days after planting, at the milky to early dough stage, cutting plants about 20 cm above the soil surface.

The whole plants (stalks, leaves, and ears) were chopped using a stationary forage machine (TRF 80, Trapp®, Jaraguá do Sul, SC, Brazil) adjusted for an average particle size of 20 mm. The chopped material was homogeneously mixed with bentonite (donated by Pepgmatech®, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil) for each treatment, then immediately ensiled in 3.5 L high-density polyethylene (HDPE) buckets (Groupack®, Barueri, SP, Brazil). The silos were sealed with adhesive tape and equipped with one-way Bunsen-type valves (Ø 8 mm) to allow gas release while preventing air entry. At the bottom of each silo, 500 g of sand covered with non-woven fabric (TNT) was placed to collect effluent. The material was compacted manually with wooden rods until reaching a target density of 600 kg/m3 of fresh matter (FM). Silos were stored at room temperature (25–30 °C) for 30, 90, or 180 days.

2.4. Quantification of Microbial Populations

Then, successive serial dilutions were prepared in sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl) to obtain dilutions ranging from 10−1 to 10−6. From each dilution, 0.1 mL aliquots were plated, in duplicate, on the respective selective culture media. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were quantified using de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe agar (MRS; Kasvi®, São José dos Pinhais, PR, Brazil), incubated in a BOD incubator (SP-500, SPLABOR®, Presidente Prudente, SP, Brazil) at 30 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions. Yeasts and filamentous fungi were quantified using potato dextrose agar (PDA; Kasvi®, São José dos Pinhais, PR, Brazil) acidified with 1% tartaric acid to inhibit bacterial growth, and incubated at 28 °C for 72 h under aerobic conditions [18].

After incubation, only plates presenting 30 to 300 colonies were considered for quantification. Colony-forming units (log CFU) were calculated according to the formula: logCFU/g = (Σ colonies × dilution factor)/sample weight (g), and results were expressed as log10 CFU/g of fresh matter. Yeasts were differentiated from filamentous fungi based on colony morphology yeast colonies appearing as creamy, convex, and smooth, whereas filamentous fungi presented aerial mycelium and pigmented hyphae spreading on the agar surface [18]. The results of these initial counts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition and microbial counts of corn plants at the time of ensiling, after the inclusion of bentonite at the respective experimental levels.

2.5. Fermentation Profile of Silages

In samples before ensiling (plant) and the silages, pH was measured using a digital potentiometer (220 V, KASVI®, São José dos Pinhais, PR, Brazil), in 25 g of the sample homogenized with 100 mL distilled water, following rest for 1 h [19]. The determination of ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) in the samples followed the methodology of Bolsen et al. [19]. For soluble carbohydrate analysis, the methodology of Dubois et al. [20] was followed. Buffering capacity (BC) was determined according to the method of Playne and McDonald [21], adapted by Mizubuti et al. [22]. In this procedure, 25 mL of distilled water was added to 5 g of fresh silage sample, and the suspension was homogenized and filtered. The filtrate (10 mL) was titrated with 0.1 N HCl to pH 4.0 and subsequently with 0.1 N NaOH to pH 7.0. Buffering capacity was expressed in milliequivalents (mEq) of NaOH per 100 g of dry matter.

The quantification of organic acids —lactic acid (LA), acetic acid (AA), propionic acid (PA), and butyric acid (BA)—followed the methodology described by Kung and Ranjit [23], using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The analyses were performed on an HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a UV detector set to 210 nm, using an Aminex HPX-87H column (300 × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) maintained at 45 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.005 M H2SO4, with a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1. The detection limits were 0.1 g L−1 for lactic acid and 0.05 g L−1 for the other organic acids.

2.6. Chemical Composition and Calculations

The samples were analyzed for DM, Ash, and ether extract (EE) according to AOAC methods 925.10, 942.05, and 920.39 [24], respectively. Crude protein (CP) content in dry matter was determined by the micro-Kjeldahl method (method 984.13) [24]; neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) concentrations were determined according to the procedures, based on the Van Soest method [25]. NDF analysis was performed using sodium sulfite and thermostable α-amylase to remove starch and protein residues. When necessary, analyses were conducted using the ANKOM fiber analyzer (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY, USA) with F57 filter bags (25 µm porosity). Results were expressed on a dry matter basis. Samples were collected at the time of ensiling to determine the chemical composition, as well as pH, soluble carbohydrates, and buffering capacity (Table 1).

2.7. Quantification of Ensiling Losses

Dry matter losses during the fermentation process, in the form of gases and effluents, as well as dry matter recovery, were quantified by weight difference according to the equations described by Zanine et al. [26]:

where

GL = (PSF − PSA)/(MFf × DMf) × 1000

- GL = gas losses (% DM);

- PSF = silo weight at sealing (kg);

- PSA = silo weight at opening (kg);

- MFf = forage mass at ensiling (kg);

- DMf = dry matter content of the forage at ensiling (%).

EL = (SAf − S) − (SAa − S)/MFf × 100

- EL = effluent losses (%);

- SAf = weight of the empty silo plus sand at opening (kg);

- SAa = weight of the empty silo plus sand at ensiling (kg);

- S = weight of the empty silo (kg);

- MFf = forage mass at ensiling (kg).

DMR = (MFa × DMa)/(MFf × DMf) × 100

- DMR = dry matter recovery (%);

- MFa = forage mass at opening (kg);

- DMa = dry matter content at opening (%);

- MFf = forage mass at ensiling (kg);

- DMf = dry matter content at ensiling (%).

All variables were corrected for dry matter content to eliminate the effect of moisture on the calculation of losses and recovery.

2.8. Aerobic Stability of Silages

Aerobic stability was determined using approximately 1 kg of representative silage samples obtained from the geometric center and both upper and lower thirds of each silo.

These subsamples were homogenized, and a composite sample was prepared for evaluation. The material was then intentionally placed back into uncompacted and unsealed plastic buckets to simulate continuous exposure to air, a necessary condition for evaluating aerobic stability. The buckets remained open throughout the monitoring period, allowing oxygen to interact with the silage, as recommended in aerobic evaluation protocols. Two digital immersion thermometers were inserted into the geometric center of each forage mass, and the temperature was recorded every 30 min. The test was conducted in an air-conditioned room maintained at 25 ± 2 °C, and ambient temperature was continuously monitored using a digital thermometer positioned near the silos. Aerobic stability was defined as the time required for the silage temperature to rise more than 2 °C above ambient temperature, as proposed by Taylor and Kung [27].

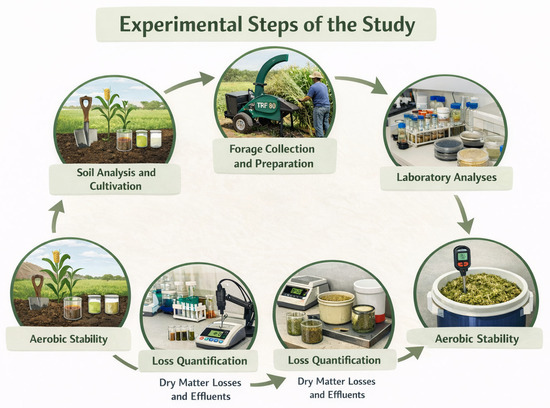

A schematic overview of the experimental design and methodological steps adopted in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the experimental steps adopted in the study, from soil analysis and forage preparation to ensiling, laboratory analyses, and evaluation of aerobic stability.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in a 5 × 3 factorial arrangement, with five bentonite levels and three silage storage times (30, 90, and 180 days). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance using the mixed model procedure (PROC MIXED) of the SAS® statistical package (version 9.2), considering bentonite levels and storage times as fixed effects and experimental repetitions as random effects. The mathematical model used was:

where Yijk = observed value for the variable under study; μ = overall mean of the response variable; αi = effect of the bentonite level; βj = effect of the storage time; (αβ)ij = interaction effect between bentonite level and storage time; and εijk = random experimental error.

Yijk = μ + αi + βj + (αβ)ij + εijk,

When a significant effect was detected (p < 0.05), means were compared using Tukey’s test. The effect of bentonite levels was evaluated by polynomial regression analysis (linear and quadratic models), and the best-fitting model was selected based on the significance of regression coefficients and the highest coefficient of determination (R2). The effect of fermentation time was assessed by Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level. When significant interactions occurred, simple effects were unfolded using the same statistical package (SAS®, version 9.2) [28].

3. Results

3.1. Fermentation Profile of Silages

There was an additive × storage time interaction effect on pH (p = 0.0330) (Table 2). The highest value was observed when bentonite was included at 80 g/kg FM in the 180-day storage time (pH 4.20), and the lowest values were found in the 30-day storage time. Furthermore, there was no significant effect (p > 0.005) from storage times.

Table 2.

Fermentation profile of corn silages added with different bentonite levels and stored for 30, 90 and 180 days.

No significant effect of the additive × storage time was detected on buffering capacity (BC) (p = 0.8110), with a main effect only from the storage time (p < 0.001). Higher values were recorded during the 90- and 180-day storage times for all bentonite levels. The lowest values were observed in the 30-day storage time.

Similarly, there was no additive × storage time interaction effect on ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) (p = 0.8110), a main effect was only observed from the storage time (p < 0.001). Higher values were found during the 90 and 180-day storage times for all bentonite levels. The lowest values were recorded in the 30-day storage time.

Regarding the water-soluble carbohydrate (WSC) content, an interaction between the additive and storage time was observed (p = 0.025). The highest values occurred at 30 days at all bentonite levels, while the lowest values were recorded at 90 and 180 days. The response of WSC to bentonite levels showed a quadratic behavior at both 30 days (p < 0.005), with an estimated maximum point of 123.9 g/kg DM, and at 90 days (p < 0.005), with an estimated maximum point of 68.2 g/kg DM, demonstrating that the variable showed a non-linear trend in both periods. At 180 days, although the linear term was significant (p = 0.017), the absence of a quadratic effect indicates that, at this storage time, WSC responded in a linearly restricted manner to increasing levels of bentonite.

3.2. Microbial Population of Silages

There was an additive × storage time interaction effect on the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) population (p < 0.001), which ranged from 3.42 to 7.43 log CFU/g silage (Table 3). Higher values were observed during the 30-day storage time for all bentonite levels. The lowest value was found in the 180-day time in the control treatment, with a population of 3.42 log CFU/g silage. Further, an increasing linear effect (p < 0.005) was observed during the 90- and 180-day storage times.

Table 3.

Microbial counts of corn silages added with different bentonite levels and stored for 30, 90, and 180 days.

As for the filamentous fungi population, there was an additive × storage time interaction effect (p < 0.001), with values from 2.32 to 4.21 log CFU/g silage. The highest value for this variable was verified in the 30-day time when 20 g/kg FM of the additive was included (4.21 log CFU/g silage). The lowest values, on the other hand, were 2.32 and 2.64 log CFU/g silage, observed in the 90-day time after ensiling. In addition, an increasing linear effect (p < 0.005) was found at 180 days of storage.

For yeasts, there was an additive × storage time interaction effect (p < 0.001), with values from 0 to 5.28 log CFU/g silage. Lower yeast counts were recorded in the 180-day storage time, at bentonite levels of 0, 20, and 60 g/kg FM, with values of 0, 0.50, and 0.57 log CFU/g silage, respectively. The highest yeast counts were observed in the 30-day storage time, compared to the 90- and 180-day times. A decreasing linear effect (p = 0.0139) was found after 30 days of storage; a quadratic effect (p = 0.0010) in the 90-day time, with a maximum point reaching 3.8 log CFU/g silage at a level of 20 g/kg FM, and an increasing linear effect (p = 0.002) after 180 days of storage.

3.3. Organic Acids of Silages

There was an additive × storage time interaction effect on the lactic acid content (p < 0.001) (Table 4). When comparing the five different levels of bentonite in the silage, the level of 60 g/kg FM resulted in a higher lactic acid content (54.02 g/kg DM) for the 90-day storage time. In contrast, for the 30-day storage time, the same bentonite level resulted in a significantly lower lactic acid value (32.04 g/kg DM). A quadratic effect (p = 0.0010) was observed during the 90-day storage time, reaching a maximum point of 53.39 g/kg DM.

Table 4.

Mean organic acid contents of corn silages added with different bentonite levels and stored for 30, 90 and 180 days.

An additive × storage time interaction effect was observed for the acetic acid content (p < 0.001), with values ranging from 10.52 to 22.36 g/kg DM. During the 180-day storage time, at levels 0 and 40 g/kg FM of the additive, higher acetic acid concentrations were recorded, with values of 22.11 and 22.36 g/kg DM, compared to the 30- and 90-day times. The lowest values were registered in the 30-day storage time, with 10.52 g/kg DM. There was a decreasing linear effect (p < 0.05) for the 90- and 180-day storage times.

Also, the interaction effect of additive × storage time was found on the propionic acid content (p < 0.001). When comparing the five different levels of bentonite in the silage, 80 g/kg FM resulted in a higher content (10.37 g/kg DM) in the 180-day storage time. In turn, in the 30-day storage time, the inclusion of 60 g/kg FM resulted in significantly lower values of propionic acid (3.29 and 3.94 g/kg DM). There was an increasing linear effect (p < 0.05) in the 90- and 180-day storage times and a quadratic effect at 180 days (p = 0.0002).

There was an additive × storage time interaction effect on the butyric acid content (p < 0.001). Comparing the five different bentonite levels, the 30-day storage time resulted in lower butyric acid values (0.52 and 0.53 g/kg DM) when the additive was included at 0 and 60 g/kg FM. The highest values were found in the 180-day storage time when bentonite levels of 20, 40, and 80 g/kg FM were added to the silages (1.25; 1.35, and 1.24 g/kg DM). No significant effect was detected on butyric acid (p > 0.05) from any of the storage times.

As for the lactic acid/acetic acid ratio, there was an additive × storage time interaction (p = 0.0472), with the highest value in the 30-day storage time. On the other hand, after 180 days of ensiling, the lowest values (2.02 and 2.15 g/kg DM), were observed. There was an increasing linear effect (p = 0.0013) in the 30-day storage time.

There was an additive × storage time interaction effect on total acid contents (p = 0.0002), with the highest value recorded during the 30-day storage time, and the lowest values observed in the 180-day storage. There was an increasing linear effect (p < 0.0014) in the 30-day storage time and a decreasing linear effect (p = 0.0277) in the 90-day storage time.

3.4. Chemical Composition of Silages

Regarding dry matter content, there was an additive × storage time interaction effect (DM) (p = 0.0467) (Table 5). When comparing the five different bentonite levels, in the 30-day storage time, higher DM contents (310.8 and 311.0 g/kg DM) were found when 0 and 60 g/kg FM bentonite were added to the silage. In addition, an increasing linear effect (p < 0.05) was detected in the 90- and 180-day storage times and a quadratic effect at 90 days (p = 0.0073).

Table 5.

Chemical composition of corn silages added with different bentonite levels and stored for 30, 90, and 180 days.

No significant interaction effect of additive × storage time was observed on the ash (p = 0.1232), with a main effect only from the storage time (p = 0.0027). When 80 g/kg FM bentonite was added to the silages, there was an increase in MM values 96.0, 110.2, and 104.5 g/kg DM. The lowest ash values were observed when no level of the additive was added (0 g/kg FM), obtaining values of 53.6, 56.0, and 58.4 g/kg DM in all storage times. In addition, an increasing linear effect (p < 0.05) was noted during the storage times of 30, 90, and 180 days.

There was no additive × storage period interaction effect on crude protein (CP) (p = 0.2539). Furthermore, there was no significant effect (p > 0.05) from any storage time.

As for ether extract (EE), there was a significant interaction effect of additive × storage time (p < 0.001). A decrease in EE content was found when 80 g/kg FM of the additive was included in silages in the three storage times. The highest value was recorded in the 180-day storage time, with no additive added to the silage (0 g/kg FM), reaching 63.3 g/kg DM. Furthermore, a quadratic effect (p < 0.05) was noted for the storage times of 30 days with a maximum point reaching 41.1 g/kg at the level of 20 g/kg FM, and 180 days with a maximum point reaching 63.3 g/kg at the level of 0 g/kg FM.

An interaction effect of additive × storage time on NDF content was observed (p = 0.0057). Lower values were verified with 0 g/kg FM of the additive in the three storage times. The highest values were observed in the storage times of 90 and 180 days when 20 and 80 g/kg FM bentonite was added to the silages (772.8 and 771.8 g/kg DM). Furthermore, an increasing linear effect (p < 0.0024) was found during the 180-day storage time.

3.5. Quantification of Ensiling Losses

There was no additive × storage time interaction effect on dry matter recovery (DMR) (p = 0.5124), with a main effect only from storage time (p = 0.0004) (Table 6). Moreover, a decreasing linear effect was observed (p = 0.0024) for the 180-day storage time, with the highest value at the level of 0 g/kg FM additive (983.4 g/kg DM), and the lowest value when adding 80 g/kg MN bentonite, with a mean value of 874.0 g/kg DM.

Table 6.

Dry matter recovery and losses in corn silages included with different bentonite levels and stored for 30, 90, and 180 days.

About gas losses (GL), only the storage time had a significant effect (p = 0.4065). The highest values were recorded in the 180-day storage time, and the lowest values were observed in the 30-day storage time. In addition, an increasing linear effect (p = 0.0139) was observed in the 30-day storage time.

Regarding effluent losses (EL), there was no additive × storage time interaction effect (p = 0.4306), with a main effect only from the storage time (p < 0.0006). An increasing linear effect (p = 0.001) was found in the 90-day storage time, with the lowest value at dose 0 of the bentonite (1.27 kg t−1), and the highest value when the inclusion of bentonite was 80 g/kg FM, with a mean value of 10.33 kg t−1.

3.6. Aerobic Stability of Silages

There was an additive × storage time interaction effect on aerobic stability (AS) (p = 0.0077), with values ranging from 50.83 to 142.06 h (Table 7). At 180 days of storage, the highest stability was recorded, reaching 142.06 h, when the silage was included with 40 g/kg FM of the additive. An increasing linear effect (p < 0.05) was observed during the storage times of 90 and 180 days.

Table 7.

Aerobic stability and maximum temperature in corn silages added with different bentonite levels and stored for 30, 90 and 180 days.

The maximum temperature was not influenced by the interaction additive × storage time (p = 0.3487), only by storage time (p < 0.001). The results indicate that the silages stored for 30 days without bentonite (0 g/kg MN) reached the highest maximum temperature, 33.76 °C. On the other hand, the lowest temperatures were found in silages stored for 180 days, when the bentonite inclusion was 80 g/kg FM, with a mean value of 26.90 °C. Furthermore, a decreasing linear effect (p < 0.05) was verified in the storage times of 30 and 180 days and a quadratic effect at 30 days (p = 0.0072).

4. Discussion

4.1. Fermentation Profile

Silages stored for 90 and 180 days showed a higher pH compared to the 30-day period, but still within the acceptable range for corn silages with dry matter content between 30 and 35%. According to McDonald, Henderson and Heron [29] and Ojeda et al. [30] silages with this level of DM have a target pH between 3.7 and 4.2, which are expected values for a process. The higher value observed is probably associated with a less intense fermentation or a slower fermentation after 90 days of storage, as well as with the use of lactic acid by heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria, as indicated by Taylor and Kung [27]. Everson et al. [14] evaluated the effect of bentonite and nitrogen on the redistribution of nitrogen in corn silage. The authors observed that pH values ranged from 3.89 to 4.08, depending on the level of bentonite added. The inclusion of bentonite in corn silage possibly helps to neutralize the organic acids formed during fermentation due to its adsorbent ability, raising the pH and creating a more stable environment for silage preservation [31].

Silages stored for 30 days showed significantly lower buffering capacity values than silages stored for 90 or 180 days (Table 5). Bentonite clay has a high BC due to its colloidal structure and the presence of exchangeable ions on its surface. The BC of bentonite clay depends on the pH of the solution. In acidic solutions, the BC is higher than in alkaline solutions, which may be associated with the pH that was also higher at 90 and 180 days. The addition of bentonite to corn silage seems to contribute to increased buffering capacity over storage time, perhaps due to its ability to stabilize the pH. Furthermore, the BC of bentonite clay increases with increasing clay levels in the solution [32]. Costa et al. [33] highlight that bentonite clay has a high cation exchange capacity (CEC), i.e., it can exchange ions with other compounds in the solution.

In this study, silages stored for 30 days showed the lowest NH3-N contents, while silages stored for 90 and 180 days showed the highest values. This suggests that bentonite may play a role in inhibiting the microbial activity responsible for ammonia production during this initial storage time (Table 5). According to Muck [34], proteolytic bacteria are inhibited in silages with low pH, which reduces proteolysis and, consequently, the production of NH3-N. This corroborates our results, which show a decline in NH3-N contents in the silages analyzed. Khorvash et al. [13] assessed the addition of bentonite to corn silage opened at 92 days and found an ammonia content of 5.71% DM, resulting in proteolysis; a finding that corroborates those of the present study when extending the storage time increased the NH3-N content.

The reduction in soluble carbohydrates observed after 180 days of storage occurred mainly due to the natural progression of the fermentation process, since lactic acid bacteria use sugars as the main substrate for the production of organic acids. However, when comparing storage times within each supplementation level, only the silage supplemented with bentonite at 20 g/kg of fresh matter showed a significant difference between periods, evidenced by distinct superscripts, while the other supplementation levels did not differ from each other throughout storage. Thus, the effect of ensiling time is predominantly manifested by the depletion of soluble carbohydrates, while the role of bentonite is more indirect. In the present study, supplementation with bentonite at 20 g/kg of fresh matter may have modulated the fermentation environment, decreasing the intensity of the acidifying action of the acids produced, especially in the first 30 days of fermentation. This modulation may occur through different chemical mechanisms: adsorption of organic acids presents in the ensiled mass, providing their immediate availability in the medium; cation exchange capacity, which can partially neutralize H+ ions, decreasing the pH drop; and buffering effect, which smooths rapid acidity variations. These mechanisms could decrease the inhibitory action of acids on plant and microbial proteolytic enzymes, contributing to greater initial proteolysis when bentonite is present. Results from Silva et al. [35] and Fransen and Strubi [15] corroborate that additives with adsorption or buffering effect can reduce soluble carbohydrate levels in silages, reinforcing that bentonite acts more on the chemical environment of the silo than directly on fermentable sugars.

4.2. Microbial Population

Lower LAB counts were observed at 90 and 180 days for all bentonite levels. The minerals present in bentonite can possibly have antimicrobial properties, inhibiting the growth of bacteria, including lactic acid bacteria [31,36]. Bentonite is a type of absorbent clay with properties of adsorption of moisture and organic compounds [37,38]. When applying bentonite to corn silage, its ability to adsorb moisture can help minimize conditions favorable to the growth of filamentous fungi. Excessive moisture contributes to the development of these spoilage microorganisms, and bentonite can act as a physical barrier to moisture, creating an environment less conducive to their proliferation. In addition to favoring the growth of fungi, high moisture content also promotes the development of Clostridium spp., anaerobic bacteria that convert lactic acid and residual sugars into butyric acid, ammonia, and biogenic amines. The activity of these microorganisms leads to strong and unpleasant odors, higher dry matter losses, and a marked reduction in the nutritional quality and palatability of the silage. By reducing the counts of yeasts, filamentous fungi, and potentially limiting the activity of Clostridium spp. through moisture adsorption, bentonite can contribute to improved aerobic stability and overall silage quality [39].

Pitt [40] reported that aerobic spoilage of silages can occur when yeast counts exceed 9 log CFU/g silage and fungal counts exceed 8 log CFU/g silage. In the present study, the values found at the three storage times were below these thresholds, indicating that yeast and fungal counts did not reach levels that compromised silage quality. This suggests that the inclusion levels of bentonite were effective in controlling the growth of undesirable microorganisms during storage. Since bentonite can absorb moisture and reduce water availability, it limits the ideal conditions for microbial development, which is crucial to prevent both aerobic and anaerobic deterioration processes in silage. The inclusion of bentonite as a chemical additive in corn silage may therefore have a beneficial effect on reducing the growth of filamentous fungi and clostridia, with positive implications for the nutritional quality and stability of silages used as animal feed.

4.3. Organic Acids

Lactic acid concentrations were higher at 90 days of ensiling, especially in silages supplemented with 0, 20, 60, and 80 g/kg of fresh matter (FM) of bentonite, compared to the 30- and 180-day periods (Table 4). This result indicates that, at 90 days, the fermentation process reached a stage of greater activity and stabilization, characterized by the predominance of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and the efficient use of available soluble carbohydrates. Supplementation with bentonite at these levels may have favored this process by modulating the fermentation environment, since its high cation exchange capacity contributes to pH stabilization and the availability of cations essential to LAB metabolism, such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ [41].

The quadratic trend observed at 90 days with increasing bentonite levels indicates that generous doses promoted greater lactic acid production, while higher levels partially reduced this effect. This behavior suggests that the excessive increase in the buffering capacity of the medium may have limited the rate of pH decline, reducing the predominance of homofermentative LAB and, consequently, the accumulation of lactic acid. Thus, the effect of bentonite on lactic acid production proved to be dependent on the dose and storage time.

The increase in propionic acid at higher bentonite levels (particularly 80 g/kg FM) and extended storage time (180 days) may indicate the activity of Propionibacterium spp., which thrive under mildly acidic, anaerobic conditions. Propionic acid concentrations above 5 g/kg DM are typically associated with improved resistance to aerobic spoilage [34], consistent with the higher stability recorded in this study.

Moderately low butyric acid concentrations (≤1.34 g/kg DM) are indicative of well-integrated values and are well below the 5 g/kg DM limit associated with clostridial activity [42]. This suggests that, regardless of the dose used, the ensiling conditions especially the adequate pH drop and reduced water availability were sufficient to inhibit Clostridium spp. The apparent absence of butyric fermentation does not occur directly from the bentonite, but from the chemical environment established in the silo. Bentonite may have contributed indirectly by modifying the ensiled matrix through mechanisms such as partial water adsorption, cation exchange capacity, and interactions with H+ ions, which can influence the acidification dynamics, but do not decisively alter the course of clostridial intervention. Thus, the low butyric acid levels mainly reflect the predominance of lactic fermentation and the rapid establishment of conditions hostile to Clostridium activity, and not a direct effect of the additive.

Overall, bentonite modified the fermentation pattern by promoting a balanced acid profile initially favoring lactic acid production and later enhancing acetic and propionic acid accumulation without inducing butyric fermentation. These effects likely stem from bentonite’s moisture-adsorbing capacity, its buffering properties, and its influence on microbial ecology during storage.

4.4. Chemical Composition

The additive increased the DM content (311.0 g/kg DM) of the silages during the 30-day storage time, especially when included at a level of 60 g/kg FM, demonstrating its efficiency as an adsorbent additive as bentonite can help absorb excess moisture, which can result in silage with a higher dry matter content (Table 5). When evaluating the addition of bentonite to corn silage, Khorvash et al. [13] found a DM content of 224 g/kg, lower than that of the present study, probably due to the corn harvest stage and the level of bentonite added.

The MM contents showed higher values for the three storage times when 80 g/kg FM additive was included, with values of 96; 110.2; and 104.5 g/kg DM (Table 5). Neumann [43] describes that the ideal MM value in corn silage is from 30 to 80 g/kg DM. Very high levels can impair silage fermentation and digestibility, while very low levels can result in a lack of stability and deterioration during storage. Thus, silages added with up to 40 g/kg FM bentonite are within the standard range described by the author. Bentonite is a clay composed mainly of minerals such as montmorillonite, quartz, feldspar, calcite, among others [36,37], and these minerals contribute to the ash content in the silage, and when the level is increased, the ash content in these silages consequently increases.

The addition of bentonite to silage increased the CP content during the 90-day storage time when 20 g/kg of the additive was added (Table 5). The CP contents in the silages are close to the minimum recommended by Van Soest [44], which is 70 g/kg. The observed values ranged from 75.3 to 84.2 g/kg DM (Table 6), indicating that the silages are within an acceptable range regarding CP content. Bentonite can reduce the activity of proteolytic microorganisms, which are responsible for protein degradation during ensiling. This can preserve protein quality and prevent ammonia nitrogen losses.

Regarding the EE content in corn silages with the inclusion of bentonite, a variation of up to 63.3 g/kg DM was observed (Table 5). The values found are within the range considered adequate, which is up to 80 g/kg [45].

NDF content ranged from 683.9 to 771.8 g/kg DM. Notably, in the three storage times without bentonite addition, NDF contents were lower compared to the other silages (Table 5). This difference can be attributed to the consumption of soluble carbohydrates during fermentation, probably responsible for the increase in NDF contents in silages added with bentonite. Increases in fiber contents can be associated with the reduction of non-structural carbohydrates, resulting in a proportional increase in the other DM components [46]. On the other hand, the decrease in NDF can be related to acid hydrolysis inhemicellulose, as indicated by McDonald [29]. Khorvash et al. [13] evaluated the addition of bentonite to corn silage and found CP and NDF levels of 75 and 587 g/kg DM, respectively; the CP level is similar to that of the present study but the NDF level is lower than in the present study, probably due to the difference in level tested. Here, bentonite had a greater capacity to express its potential since it was evaluated at different levels.

4.5. Ensiling Losses

Values of GL and EL were lower in silages with g/kg bentonite stored for 30 and 90 days (Table 6). Corn silages added with bentonite presented different levels of effluent losses according to the storage time and the level of additive. Losses ranged from 1.27 to 17.90 kg per ton of silage, with the lowest losses found after 90 days of storage. Khorvash et al. [13] concluded that the inclusion of 1% bentonite in corn silage did not significantly improve its quality. Over a 3-year period, EL ranged from 84 to 147 mL kg−1 with the addition of bentonite and was 180 mL kg−1 in the control silage. This result can be associated with the DM content, which was lower for silages containing 20 g/kg of the additive (Table 6); therefore, a lower DM content can consequently promote greater effluent losses since it has a higher moisture content.

Mean values of DMR of corn silages added with bentonite in this study are close to those obtained by Vieira et al. [47], who evaluated the effect of different levels of urea on corn silage. These authors reported mean values of 888.5; 946.8; 933.2 and 972.5 g/kg DMR for silages included with 5; 10; 15 and 20 g/kg of urea (on fresh matter basis), respectively. These results suggest that bentonite may have a similar effect to urea in preserving dry matter in corn silage, possibly by forming complexes with organic acids produced during fermentation, which reduce losses. Similar results were presented by Silva et al. [35] when evaluating the effect of an additive containing sodium benzoate, potassium sorbate, and sodium nitrite, finding a DMR of 95.31% DM. Overall, bentonite provided better dry matter recovery, probably due to the moisture absorption effect that can help reduce the losses of soluble nutrients that occur during fermentation; less moisture means less leaching of soluble nutrients, resulting in higher dry matter recovery.

4.6. Aerobic Stability

Corn silages with different levels of bentonite showed higher AE in the 180-day storage time, with values between 103.16 and 142.06 h. This can be explained by the lower fermentation activity of these silages at this time, which favored the preservation of the ensiled material (Table 7). The addition of bentonite may be beneficial to improve aerobic stability, since our findings indicated moderate increases in the levels of acetic and propionic acid at 180 days, thus being fully related to greater aerobic stability in this same fermentation period (Table 3), which has the potential to inhibit yeasts, playing a crucial role upon aerobic exposure. The storage time of the silage affects its temperature, as the results evidence. The silages stored for 30 and 180 days showed the lowest temperatures, ranging from 26.90 to 31.10 °C. Silages without the additive presented the highest temperatures (33.76 °C). Bentonite has antimicrobial properties [31,36] that can help inhibit the growth of certain microorganisms, including those responsible for aerobic spoilage of silage. Although it is not a primary antimicrobial preservative, bentonite can have secondary effects in reducing aerobic microbial activity due to its physical and chemical properties.

Evaluating our results, the silages included with 20 g/kg bentonite had lower gas and effluent production at 30 and 90 days, reducing their losses, and increasing DMR at 90 days. This level also resulted in a higher LAB population and lower NH3-N levels at 30 days, in addition to higher NDF content at 90 days and a lower yeast population at 180 days. The level of 60 g/kg controlled the growth of filamentous fungi at 90 days and increased lactic acid in the same period, butyric acid reduced and DM increased at 30 days. The level of 40 g/kg favored the production of acetic acid, aerobic stability, and silage temperature but decreased soluble carbohydrates at 180 days of storage, thus extending its usage time compared to corn silages without bentonite. The level of 80 g/kg increased lactic acid/acetic acid at 30 days, propionic acid and NDF at 180 days, and reduced EE at 30 and 180 days. Thus, including the bentonite additive promoted changes in the chemical composition, microbial populations, fermentation profile, ensiling losses, and aerobic stability of the silages.

5. Conclusions

The inclusion of bentonite in corn silage at levels of 20 to 60 g per kilogram of fresh matter effectively enhances silage quality during storage for 180 days. This range improves aerobic stability by reducing yeast and fungal proliferation and helps preserve key fermentation characteristics, such as pH and organic acid balance, thereby contributing to better nutrient retention and overall feed value. Higher doses slightly reduced dry matter recovery and increased fiber content, indicating that excessive inclusion may be detrimental. Bentonite thus represents a practical and economical additive to enhance silage preservation, though further studies should evaluate its effects on intake, digestibility, and cost-effectiveness compared to other additives.

Author Contributions

B.d.S.S.: Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation. J.S.d.O.: Supervision. J.P.d.F.R.: Supervision. L.M.P.R.: Visualization and Research. E.M.S.: Supervision. A.J.d.S.M.: Visualization and Research. L.P.S.: Writing—Proofreading and editing. P.G.B.G.: Visualization and Research. A.L.P.: Visualization and Research. E.d.S.d.S.: Visualization and Research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DM | Dry matter |

| NDF | Neutral detergent fiber |

| WSC | Water-soluble carbohydrates |

| ADL | Acid detergent lignin |

| CP | Crude protein |

| EE | Ether extract |

| OM | Organic matter |

| N-NH3 | Ammonia nitrogen |

References

- Guan, H.; Shuai, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ran, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, X. Microbial community and fermentation dynamics of corn silage prepared with heat-resistant lactic acid bacteria in a hot environment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendia, L.C.R.; Oliveira, J.G.d.; Azevedo, F.H.V.; Nogueira, M.A.d.R.; Silva, L.V.d.; Aniceto, E.S.; Sant’Anna, D.F.D.; Crevelari, J.A.; Pereira, M.G.; Vieira, R.A.M. A two-location trial for selecting corn silage hybrids for the humid tropic: Forage and grain yields and in vitro fermentation characteristics. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2021, 50, e20200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.B.; Machado, D.S.; Alves Filho, D.C.; Brondani, I.L.; da Silva, V.S.; Argenta, F.M.; de Moura, A.F.; Borchate, D. Características agronômicas da planta e produtividade da silagem de milho submetido a diferentes arranjos populacionais. Magistra 2017, 29, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, F.C.; Lara, E.C.; Assis, F.B.D.; Rabelo, C.H.S.; Morelli, M.; Reis, R.A. Características da fermentação e estabilidade aeróbia de silagens de milho inoculadas com Bacillus subtilis. Rev. Bras. Saúde Produção Anim. 2012, 13, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L. Silage fermentation and additives. Arch. Latinoam. Prod. Anim. 2018, 26, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Muck, R.E.; Nadeau, E.M.G.; McAllister, T.A.; Contreras-Govea, F.E.; Santos, M.C.; Kung, L. Silage Review: Recent Advances and Future Uses of Silage Additives. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3980–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, N. Effect of the adsorption of surfactants on the rheology of Na-bentonite slurries. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 75, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, F. A white bentonite from San Juan Province, Argentina—Geology and potential industrial applications. Appl. Clay Sci. 2000, 16, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, H.S.; Campos, L.F.A.; Menezes, R.R.; Cartaxo, J.M.; Santana, L.N.L.; Neves, G.A.; Ferreira, H.C. Influência das variáveis de processo na obtenção de argilas organofílicas. Cerâmica 2013, 59, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodgorov, N.G.; Saydullaevich, A.O.; Rajabovna, T.H. The Influence of the Bentonite Clay Coated Winter Wheat Seeds on Laboratory Germination. Tex. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2022, 2, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yarmots, G.A.; Lyudmila, P.Y. Natural Sorbents in Agriculture. In Proceedings of the International Scientific and Practical Conference ‘AgroSMART—Smart Solutions for Agriculture’ (AgroSMART 2018), Tyumen, Russia, 16–20 July 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, E.E.; Davidovich, A.D.; Barr, G.W.; Griffel, G.W.; Dayton, A.D.; Deyoe, C.W.; Bechtle, R.M. Ammonia Toxicity in Cattle. I. Rumen and Blood Changes Associated with Toxicity and Treatment Methods. J. Anim. Sci. 1976, 43, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorvash, M.; Colombatto, D.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Ghorbani, G.R.; Samei, A. Use of absorbants and inoculants to enhance the quality of corn silage. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 86, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Everson, R.A.; Jorgensen, N.A.; Barrington, G.P. Effect of Bentonite, Nitrogen Source and Stage of Maturity on Nitrogen Redistribution in Corn Silage. J. Dairy Sci. 1971, 54, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, S.C.; Strubi, F.J. Relationships Among Absorbents on the Reduction of Grass Silage Effluent and Silage Quality. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 2633–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.D.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s Climate Classification Map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donagema, G.K.; Campos, D.V.B.; Calderano, S.B.; Teixeira, W.G.; Viana, J.H.M. Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solos; Embrapa Solos: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011; 230p. [Google Scholar]

- Jobim, C.C.; Nussio, L.G.; Reis, R.A.; Schmidt, P. Avanços Metodológicos na Avaliação da Qualidade da Forragem Conservada. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2007, 36, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, K.K.; Lin, C.; Brent, B.E.; Feyerherm, A.M.; Urban, J.E.; Aimutis, W.R. Effect of Silage Additives on the Microbial Succession and Fermentation Process of Alfalfa and Corn Silages. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 3066–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.T.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playne, M.J.; McDonald, P. The buffering constituents of herbage and of silage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1966, 17, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizubuti, I.Y.; Pinto, A.P.; Pereira, E.S.; Ramos, B.M.O. Métodos Laboratoriais de Avaliação de Alimentos para Animais; EDUEL: Londrina, Brazil, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kung, L., Jr.; Ranjit, N.K. O efeito do Lactobacillus buchneri e outros aditivos na fermentação e estabilidade aeróbica da silagem de cevada. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanine, A.d.M.; Santos, E.M.; Dórea, J.R.R.; Dantas, P.A.d.S.; Silva, T.C.; da Pereira, O.G. Evaluation of elephant grass silage with the addition of cassava scrapings. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2010, 39, 2611–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.C.; Kung, L. The Effect of Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 on the Fermentation and Aerobic Stability of High Moisture Corn in Laboratory Silos. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS. SAS 9.0 User’s Guide, version 4; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2004.

- McDonald, P.; Henderson, A.R.; Heron, S.J.E. The Biochemistry of Silage, 2nd ed.; Chalcombe Publications: Marlow, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda, F.; Cáceres, O.; Esperance, M. Sistema de evaluación para ensilajes tropicales. In Conservación de Forrajes; López Tapanes, R.V., Pereira Pérez, N., Loidi Ramos, R., Pérez Navarrete, A., Eds.; Pueblo y Educación: Ciudad de La Habana, Cuba, 1991; pp. 15–65. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, F.; Nüesch, R. Characteristics and sealing effect of bentonites. In Geosynthetic Clay Liners; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, E.F.d.S.; Aguiar, E.S.; Lima, É.K.A.d.; Alves, K.E.d.S.; Farias, J.R.d.S.; Almeida, Y.B.A.d.; Alves, M.E.R.; Silva, H.d.J.B.d.; Braga, A.d.N.S.; Santos, V.B.d. Argila bentonita: Uma breve revisão das propriedades e aplicações. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e7912239917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, W.R.P.; de Oliveira, L.R.C.; Nóbrega, K.C.; Costa, A.C.A.; Gonçalves, R.L.D.N.; Lima, M.C.d.S.; Nascimento, R.C.A.d.M.; de Souza, E.A.; de Oliveira, T.A.; Barros, M.; et al. Evaluation of Saline Solutions and Organic Compounds as Displacement Fluids of Bentonite Pellets for Application in Abandonment of Offshore Wells. Processes 2023, 11, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, R.E. A Lactic Acid Bacteria Strain to Improve Aerobic Stability of Silages; U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, É.B.; Savage, R.M.; Biddle, A.S.; Polukis, S.A.; Smith, M.L.; Kung, L., Jr. Effects of a chemical additive on the fermentation, microbial communities, and aerobic stability of corn silage with or without air stress during storage. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagaly, G. Bentonites: Adsorbents of Toxic Substances. In Surfactants and Colloids in the Environment; Steinkopff: Dresden, Germany, 1994; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Permien, T.; Lagaly, G. The rheological and colloidal properties of bentonite dispersions in the presence of organic compounds: I. Flow behaviour of sodium-bentonite in water-alcohol. Clay Miner. 1994, 29, 751–760. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M.C.P.; Langbehn, J.T.; Oliveira, C.M.; Elyseu, F.; Cargnin, M.; Noni, A.D., Jr.; Frizon, T.E.A.; Peterson, M. Estudo do comportamento e caracterização de argilas bentoníticas após processo de liofilização. Cerâmica 2018, 64, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreani, G.; Tabacco, E.; Schmidt, R.J.; Holmes, B.J.; Muck, R.E. Silage review: Factors affecting dry matter and quality losses in silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3952–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, R.E. Dry matter losses due to oxygen infiltration in silos. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1986, 35, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadziakiewicza, M.; Kehoe, S.; Micek, P. Physico-Chemical Properties of Clay Minerals and Their Use as a Health Promoting Feed Additive. Animals 2019, 9, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P. Silage fermentation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1982, 7, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Leão, G.F.M.; Coelho, M.G.; Figueira, D.N.; Spada, C.A.; Perussolo, L.F. Aspectos produtivos, nutricionais e bioeconômicos de híbridos de milho para produção de silagem. Arch. Zootec. 2017, 66, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant, 2nd ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neiva Júnior, A.P.; Silva Filho, J.C.d.; Von Tiesenhausen, I.M.E.V.; Rocha, G.P.; Cappelle, E.R.; Couto Filho, C.C.d.C. Efeito de diferentes aditivos sobre os teores de proteína bruta, extrato etéreo e digestibilidade da silagem de maracujá. Ciênc. Agrotecnol. 2007, 31, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, T.F.; Reis, R.A.; Amaral, R.C.d.; Siqueira, G.R.; Roth, A.P.d.T.P.; Roth, M.d.T.P.; Berchielli, T.T. Perfil fermentativo, estabilidade aeróbia e valor nutritivo de silagens de capim-marandu ensilado com aditivos. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2008, 37, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.A.; Cezário, A.S.; Valente, T.N.P.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Santos, W.B.R.d.; Ferreira, P.R.N. Evaluation of the Addition of Urea or Calcium Oxide (CaO) on the Recovery of Dry Matter of the By-Product of Sweet Corn Silage. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.