Abstract

The extremophile yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa can grow in extremely poor environments. Glutamine (Gln) is an important anaplerotic substrate for gluconeogenesis and pentose synthesis. Glutaminase (Glnase) produces glutamate which in turn undergoes transamination to produce the Krebs cycle intermediate α-keto-glutarate. The yeast enzyme has low similarity with human GLS1, although the active site is partially conserved. Also, antibodies against GLS1 cross react with the yeast enzyme. Glnase is a therapeutic mark in tumor treatments, where endogenous Glnase is inhibited with different pharmaceutical agents. Another proposed approach is to add exogenous fungal Glnase to deplete Gln pools, thus starving the tumor. Using Gln as the sole carbon source, R. mucilaginosa grew better than Debaryomyces hansenii, while Saccharomyces cerevisiae did not grow. In addition, the Gln-dependent growth of R. mucilaginosa was inhibited by two different Gln metabolism inhibitors used in cancer therapy, namely 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) and Telaglenastat (CB-839). In cell homogenates from R. mucilaginosa DON inhibited Gln metabolism at similar concentrations as those used in mammals. The ability of R. mucilaginosa to grow on Gln as the sole carbon source is exceptional and it may be used as a suitable tool to evaluate agents targeting tumoral Gln metabolism. It is proposed that R. mucilaginosa may be a valuable source of exogenous Glnase.

1. Introduction

Extremophiles are exceptionally resilient organisms that grow in the most adverse conditions [1,2]. Among these, some may be regarded as polyextremophiles as they thrive in widely different extreme conditions [3]. The yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa survives in Antarctic ice, in high heavy metal concentrations, and in hypoxic environments [4]. R. mucilaginosa can also grow in environments where carbon or nitrogen are scarce. Industrially, R. mucilaginosa is mostly used in bioremediation and in the production of carotenoids for cosmetic purposes [5].

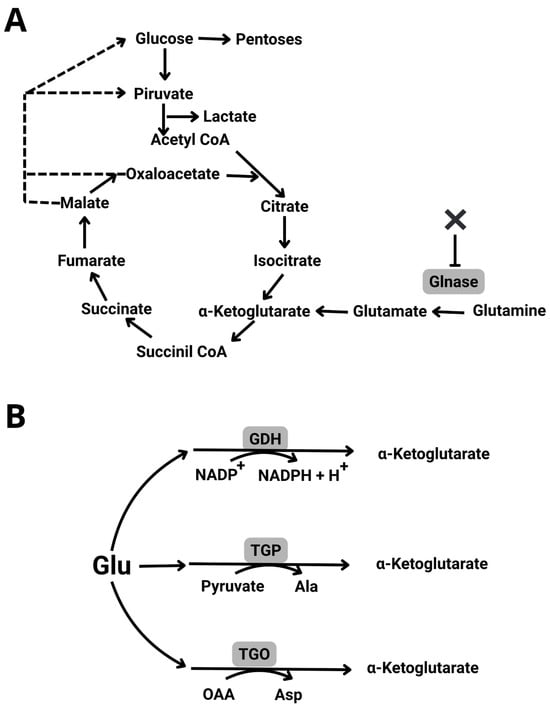

To funnel α-amino acids into carbon metabolism, anaplerotic reactions strip nitrogen, and thus produce α-keto-acids [6]. Perhaps the most important anaplerotic reaction is catalyzed by glutaminase (Glnase). This enzyme deaminates glutamine (Gln) to glutamate (Glu), which in turn is transaminated to α-keto-glutarate (α-KG) (Figure 1A). Then, the Krebs cycle intermediate α-KG may feed gluconeogenesis and the pentose cycle (Figure 1B) [6]. At the same time N from Gln is used in the synthesis nitrogenous bases and nucleotides, which in turn is exceedingly important in cancer metabolism [7].

Figure 1.

Glutamine metabolism. When used as a sole nutrient, Gln supplies carbon, nitrogen and reducing power to the cell. (A) Gln is an anaplerotic reagent, entering the Krebs cycle by deamination to yield Glutamate which in turn produces a-ketoglutarate. Glutaminase, which is critical for its entrance, may be inhibited by different molecules (X). (B) Glutamate may undergo different trans-aminations producing other amino acids and may also reduce NADP+ to NADPH + H+.

It is known that tumor cells grow in hypoxic, acidic environments and survive without glucose uptake, consuming fats and amino acids, including Gln [8]. Gln is an abundant amino acid that readily provides the cell with nitrogen and with Krebs cycle intermediates; to do so, it deaminates to Glutamate (Glu), which in turn produces α-ketoglutarate [9,10,11]. In fact, when both glucose and oxygen supply decrease in tumor cells due to defective blood vessel architecture, tumors use amino acids from neighboring, dying cells [8]. Thus, two strategies to block the use of Gln by tumors have been designed, in addition to ketogenic dieting and chemotherapy. The first involves the inhibition of endogenous Glnase, using different chemically synthesized enzyme-inhibitors [11,12,13]. A second approach proposes the use of exogenous fungal Glnase, e.g., from Aspergillus versicolor, to deplete the extracellular Gln pool inhibiting the growth of different cell lines [14].

To further evaluate the extraordinary resilience of R. mucilaginosa and to determine whether it can survive in extremely poor environments, it was tested to determine if it can grow using Gln as the sole carbon source. In addition, the effect of two well characterized inhibitors of Gln metabolism in tumors was tested. R. mucilaginosa grew on Gln and growth was inhibited by the covalent Gln metabolism inhibitor DON and by the reversible Glnase non-competitive inhibitor Telaglenastat (CB-839) [15]. Inhibition of R. mucilaginosa Gln metabolism by inhibitors designed for mammalian enzymes may be due to the close similarities in the active sites observed. It is proposed that R. mucilaginosa may be used as a reliable, efficient tool to screen possible tumor-Gln metabolism inhibitors. In fact, future research may lead to the use of Glnase from R. mucilaginosa exogenously to deplete extra-cellular Gln in tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

All reagents were analytical grade. Deoxycholic acid, trichloroacetic acid, hydroxylamine chorohydrate, phenylmethanesulfonyl, glucose, L-arginine, L-glutamine, L-histidine, and sorbitol were from Merck/Sigma-Aldrich (Livonia, MI, USA). Peptone and yeast extract were sourced from MCD Lab (Mexico City, Mexico). Nitrogenated base (D9515 Drop-out Mix Complete w/o Yeast Nitrogen Base (DO, Dropout, Powder)) and amino acid mix (M3854 MEM Non-Essential Amino Acid Mix 100X (Powder)) were from US Biological (Salem, MA, USA); ferric chloride from Baker Analyzed (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA); malic acid from Sigma (Livonia, MI, USA), and Tris from Roche (Basilea, Switzerland). Bovine serum albumin was acquired from GoldBio (St. Louis, MO, USA), Nessler reagent from Hycel Reactivos (Estado de Mexico, Mexico). Glnase inhibitors, DON (6-diazo-5-oxo-L-nor-Leucine, purity ≥ 95%) and Telaglenastat (CB-839) (trifluoromethoxy)phenyl-acetyl-amino-3-pyridazinyl-butyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl-2-pyridineacetamide) were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

2.2. Biological and Growth Media

Different yeast species were tested for their ability to grow on Gln. R. mucilaginosa ATCC 66034; Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303 1Aand Debaryomyces hansenii Y7426. Yeast was kept at room temperature in Petri dishes containing YPD agar (10 g yeast extract, 20 g peptone, 20 g glucose, and 20 g agar). Cells were used within three weeks.

As indicated, the three-culture media used were:

- •

- MS: Synthetic Glycolytic medium (nitrogen base 6.7 g/L, dextrose 20 g/L and amino acid mixture 1.85 g/L, pH 7.0).

- •

- NB: Nitrogenated base medium (nitrogen base 6.7 g/L, pH 7.0).

- •

- Gln-NB, NB plus Gln (68 mM Gln, nitrogen base 6.7 g/L, pH 7.0).

2.3. Growth Curves

Cultures in 50 mL of the indicated medium were initiated by single colonies. After 24 h of incubation, cell growth was assessed by inoculating 100 mL of the corresponding medium into 250 mL nephelometric flasks, following a previously described protocol [16]. Briefly, the initial absorbance at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.05 OD. Growth was monitored using a Klett-Summerson Model 800 colorimeter (green filter; Klett Manufacturing Co., New York, Brooklyn, NY, USA). Cultures were stirred at 250 rpm in a G10 Gyratory Shaker (New Brunswick Scientific, Enfield, CT, USA) at 30 °C. Klett units were converted to OD by multiplying by a factor of 0.002 [17]. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

To evaluate the effect of increasing concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 mM) of either the glutamine analog DON or the Glnase non-competitive inhibitor CB-839 on the growth of R. mucilaginosa, precultures were initiated from single colonies in 50 mL of MS or Gln-NB medium and incubated for 24 h at 30 °C. Cultures were then diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05 and transferred to 100-well honeycomb plates and optical density was recorded hourly using a Bioscreen C automated plate reader (Oy Growth Curve Ab Ltd., Helsinki, Finland). The DON vehicle, DMSO, was added at a final concentration of 2% v/v in all samples, including controls. Growth curves were recorded at regular intervals, and all measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4. Glutamine Metabolism Activity

A hydroxyl-aminolysis assay was used to evaluate Gln metabolism activity [18]. Cells were grown in MS for 24 h and harvested by centrifugation. The resulting pellets were homogenized by vortexing in three 1 min cycles, each period alternated by 1 min resting on ice, in the presence of 0.3 mm glass beads (50% v/v). Homogenates were centrifuged, then resuspending 1 mg wet weight/mL in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0.

Each sample was incubated for 2 h at 30 °C under agitation (70 rpm) in the presence of increasing concentration of DON (0 to 0.5 mM). Then, 1/10 v/v of a solution of 0.1 M Gln and 1.0 M hydroxylamine pH 7.0 was added, and incubation continued for an additional hour. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.25 mL of a mixture containing 50 g/L trichloroacetic and 100 g/L ferric chloride in 0.66 M HCl. A blank sample without Gln, in which TCA was added at time 0, was included as the control.

Samples were centrifuged at 3400× g for 5 min, and supernatants were transferred to a microplate reader (POLARstar Omega, BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany) and read at 500 nm. A blank sample without Gln, in which TCA was added at time 0, was included as the control. The product, γ-glutamyl-hydroxamic acid, was estimated by calculating an absorbance A = 0.640 for 2 µmols at 500 nm [19].

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

Rhodotorula sp. glutaminases were analyzed for their phylogenetic relationships, among themselves and against human Glnases. Complete protein sequences were used. A total of 7 different Glnase-encoding sequences were retrieved from the GenBank database and were included in the analysis. A Clustal Ω algorithm multiple alignment analysis was performed [20]. Key active site residues [21] are colored as indicated in the legend to the figure.

2.6. Western Blot Electrophoresis

Yeast samples were washed twice in water by centrifugation at 6000× g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in RIPA Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitors 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), disrupted using 3 mm glass beads and vortexed for 5 min (Vortex V-32; Biosan, Riga, Latvia) using a Sonics VibraCell sonicator (Sonics & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT, USA) at 75% amplitude for 25 s. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min. The supernatant was recovered, and protein concentration was measured by Bradford in a PolarStar Omega (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) [22]. Samples were diluted in a 5X buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 50 % glycerol, 5% SDS, 5% β-mercapto-ethanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and boiled for 5 min. SDS/PAGE was performed in 10% polyacrylamide gels and electro transferred to poly (vinylidene difluoride) membranes as reported elsewhere [23]. Membranes were blocked with 0.5% albumin in TBS-T (20 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl, 7.6, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the α-Glutaminase primary antibody (Sc-100533, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with a secondary antibody. Membranes were washed again, and the bands were developed by chemiluminescence using an Immobilon Western HRP Substrate (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) standard X-ray film [24]. HeLa cells extract was used such as control.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance among multiple groups was associated with a one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey or Dunnett’s test, as appropriate. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism for Windows, version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. R. mucilaginosa Growth Using Glutamine as the Sole Carbon Source

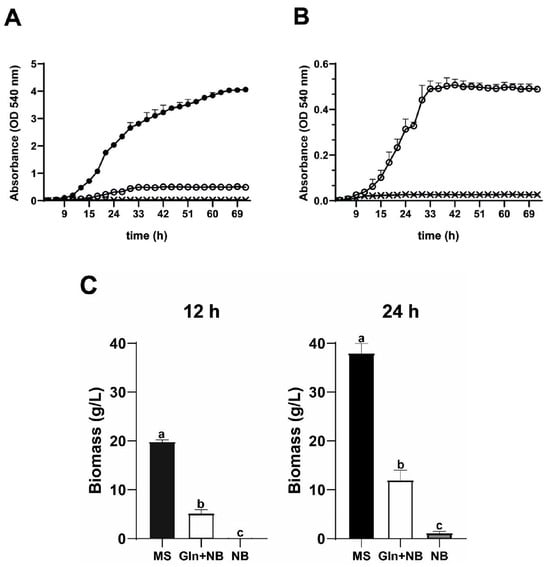

Growth of R. mucilaginosa in a synthetic glycolytic medium (MS) was compared to growth in a nitrogen base medium without carbon source (NB) or with Gln (Gln-NB) (Figure 2A). In MS, R. mucilaginosa grew to 4.0 OD, which is comparable to other species of yeasts, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Debaryomyces hansenii. In NB, no growth was detected. When Gln was added to the NB medium (Gln-NB) R. mucilaginosa, grew to 0.4 OD (Replotted in Figure 2B) or about one tenth as in MS, but still remarkable considering that Gln was the only carbon source (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Growth curves of R. mucilaginosa in different media. (A) Growth was evaluated using three different culture media: a rich synthetic medium with dextrose and amino acids MS (•), nitrogen base medium alone NB (x), and NB plus Gln (68 mM), Gln-NB (O). Growth was measured in a Klett-Summerson spectrometer equipped with a green filter. Initial concentrations were adjusted to 0.05 OD. (B) Replot of data in A using a different scale; except MS data were omitted bars are media ± SD; (C) Biomass yield in g (ww)/L at 12 and 24 h. Letters a, b, and c indicate significant differences. All cases n = 3.

As expected from the absorbance data, biomass yields were dependent on nutrient availability (Figure 2C). In MS and at 12 h, biomass was 20 g, while at 24 h it was 40 g ww/L. In Gln-NB, yields were lower: 5 g/L (ww) at 12 h and 15 g/L (ww) at 24 h. In NB alone, no biomass was detected at 12 nor at 24 h (Figure 2C). Thus, it was concluded that R. mucilaginosa can grow on Gln as the sole carbon source.

3.2. Growth on Gln-NB Was Minimal in Debaryomyces hansenii and Absent in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

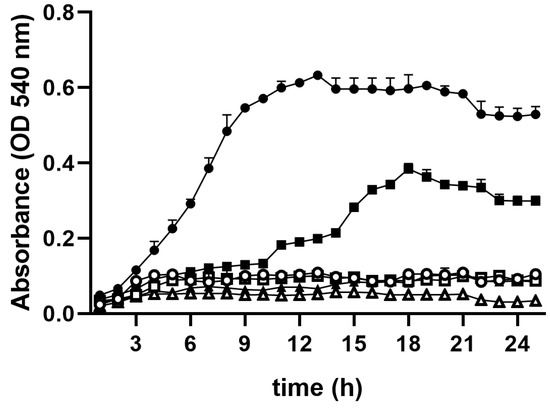

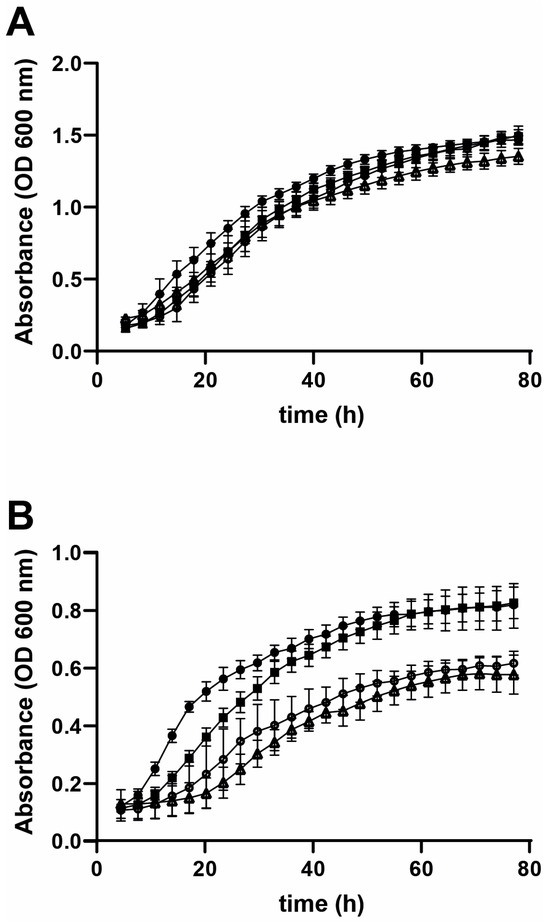

Once it was determined that R. mucilaginosa grew using Gln as the sole carbon source, it was decided to compare its growth against other yeast species, namely: D. hansenii, which is highly resistant to different types of stress and may even grow in sea water, where NaCl is 0.6 M [25,26], and S. cerevisiae [27], which is widely used in biochemical and molecular biology studies. All three species were grown either in minimal medium, alone (NB) or in the presence of Gln (Gln-NB) (Figure 3). In all cases, growth in NB was negligible. In Gln-NB, S. cerevisiae still did not grow, while D. hansenii exhibited a large lag phase of approximately 40 h and then grew to an OD of 0.36 at 18 h. For R. mucilaginosa the Lag phase was about 3 h, and it reached the stationary phase after 12 h with an OD of 0.6 (Figure 3). Thus, in Gln-NB, R. mucilaginosa grew better than the two other species tested: S. cerevisiae did not grow at all, while D. hansenii took a long time to exit the lag phase and reached an OD of 0.3 to 0.35 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Growth curves in NB (empty symbols) or in Gln-NB (full symbols) for three yeast species. R. mucilaginosa: Circular signs: Gln-NB Full, NB empty; D. hansenii: Square signs: NB Empty, Gln-NB Full; S. cerevisiae: Triangular signs: NB Empty, Gln-NB Full. Cells were pre-cultured in MS and added to an initial concentration of OD 0.05. Experimental conditions as in Figure 1.

3.3. R. mucilaginosa Growth Decreases in the Presence of Mammalian Gln Metabolism-Inhibitors 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) and Telaglenastat (CB-839)

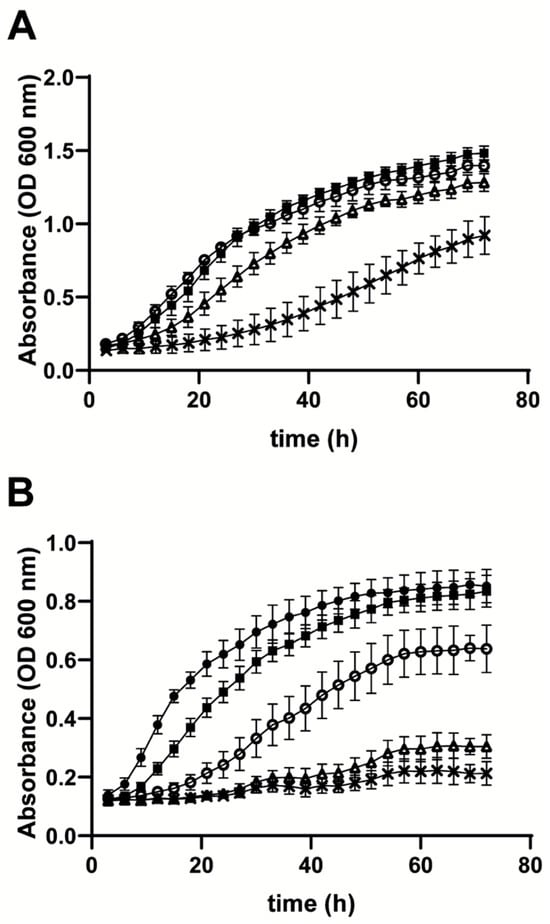

In Gln-NB, R. mucilaginosa grew better than D. hansenii, while S. cerevisiae did not grow at all (Figure 3). To further evaluate the importance of Gln as a carbon source in R. mucilaginosa, it was grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of two Gln metabolism inhibitors used in cancer treatment [15,28], namely DON (Figure 4) and CB-839 (Figure 5). DON is a Gln-like molecule that is used in cancer treatment as it binds covalently to the active site of Glnase and other molecules thus inhibiting their activity [13,28]. The non-competitive Glnase inhibitor CB-839 is also used to treat tumors such as colorectal cancer [29] and melanomas [30]. Experiments were conducted in either a rich MS medium (Figure 4A and Figure 5A) or in Gln-NB (Figure 4B and Figure 5B).

Figure 4.

Effect of different DON concentrations on the growth rate of R. mucilaginosa cultured in (A) MS or (B) Gln-NB. Experimental conditions, as in Figure 3, except that increasing concentrations of DON were added to the growth medium. R. mucilaginosa growth in (A) MS. (B) Gln-NB. No additions (•); DMSO alone (■); 0.05 mM DON (O); 0.3 mM DON (Δ); 0.5 mM DON (x).

Figure 5.

Effect of different CB-839 concentrations on the growth rate of R. mucilaginosa cultured in (A) MS or (B) Gln-NB. Experimental conditions, same as in Figure 3, except that increasing concentrations of CB-839 were added to the growth medium. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa growth in (A) MS or (B) Gln-NB. No additions (•); DMSO alone (■); 0.05 mM cb-839 (O); 0.3 mM CB-839 (Δ).

At different concentrations DON inhibited growth of R. mucilaginosa. In MS (Figure 4A), and after 24 h, 0.3 mM DON inhibited growth by 50%. In Gln-NB, where growth was fully dependent on Gln, 50% growth inhibition at 24 h was reached by adding 0.05 mM DON, which is comparable to the IC50 reported in mammalian cells [31]. In Gln-NB, but not in MS, 0.50 mM DON inhibited growth completely (Figure 4B), suggesting that in Gln-NB, Gln, which is essential for growth was fully inhibited by DON (Figure 4).

When the non-competitive Glnase inhibitor CB-839 was tested, the growth of R. mucilaginosa was not inhibited in MS (Figure 5A). In contrast, in Gln-NB inhibition by CB-839 was observed both, at 0.05 and 0.3 mM (Figure 5B). Thus, CB-839 does inhibit Gln metabolism in R. mucilaginosa; however, inhibition seemed to disappear as incubation progressed. This was possibly due to the reversible nature of inhibition or the increase in enzyme concentration when cells multiply. Still. CB-839 inhibition of growth was evident, more so during early incubation.

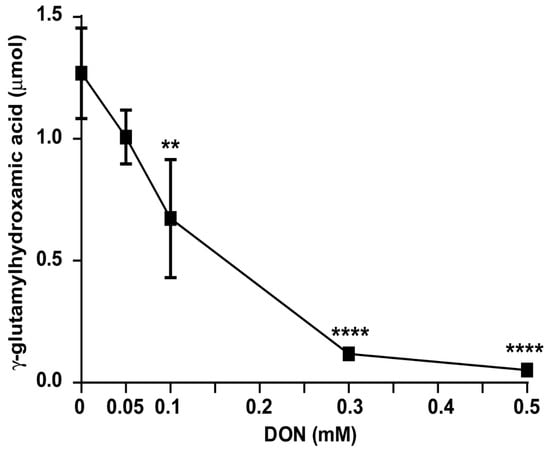

3.4. DON Inhibited Glnase activity in R. mucilaginosa

To confirm that Gln metabolism in R. mucilaginosa was sensitive to DON, it was decided to measure Gln metabolism in cell homogenates in the absence and in the presence of different concentrations of this covalent inhibitor (Figure 6). R. mucilaginosa Gln metabolism was inhibited by the same DON concentrations that inhibited Gln-dependent growth (Figure 4B). The DON concentration required to inhibit half the Gln production activity was 0.1 mM, while at 0.5 mM DON, Glnase was completely inhibited.

Figure 6.

Effect of DON on the R. mucilaginosa glutaminase activity. Cells were grown 24 h and harvested as indicated in the methods. Cell homogenates were prepared and incubated with increasing concentrations of DON in DMSO. The solvent was always adjusted to 20 µL DMSO/Tris mL; additionally, DMSO was also included in the control. n = 3. Significant difference against the control p-value: ** 0.60; **** 1.15.

The effects of DON on Gln metabolism are observed in the same range as those observed in different mammalian tumor studies (Table 1). This suggests that R. mucilaginosa may be an adequate model to study tumor metabolism. Units are those reported in each study, these are rather similar in all cases.

Table 1.

DON concentrations required to inhibit Gln metabolism in different organisms.

3.5. Protein Sequence Identity Between Rhodotorula Species and Human Glutaminase Isoforms

To further compare Glnases in humans and in R. mucilaginosa, it was decided to compare protein sequences from different Rhodotorula species against human GLS1 and GLS2. The Glnase amino acid primary sequences from various Rhodotorula species show low identity with either GLS1 or GLS2 (Supplementary Figure S1). Specifically, the R. toruloides (KAJ8294719.1) protein sequence shares 17.86% identity with the human kidney GLnase isoform GLS1 (O94925) and 17% identity with the human liver Glnase isoform GLS2 (Q9UI32); R. diobovata (TNY20467.1) shares 18.03% sequence identity with GLS1 and 16.86% with GLS2.; R. babjevae (GAA5855548.1) shares 18.74% sequence identity with GLS1 and 18% with GLS2; R. graminis (GAA5925950.1) 17.72% with GLS1 and 17.22 % with GLS2; R. glutinis (GAA5905991.1) shares 19.28% and 17.61%, respectively. Further data show that among Rhodotorula species, Glnase sequence identities are high, e.g., the Glnase from R. graminis shares 70.49%, 81.53%, 90.29%, and 90.81% identity with R. toruloides, R. diobovata, R. babjeva, and R. glutinis, respectively. Still, when the active sites from these enzymes were compared, it was observed that the key residues were partially conserved. In the glutamate-binding pocket of human GLS1, it has been reported that residues Asn335 and Tyr414 form hydrogen bonds with the α-carboxylate group of glutamate, while Glu381 and Tyr249 interact with the α-amino group [21]. When compared to the Rhodotorula Glnases, it was observed that: Tyr residues Tyr 414 and Tyr 249 were conserved in all cases (yellow) and Asn 335 was semiconserved, as in yeast it was replaced by Asp (green). In contrast, Glu 381 was substituted by Tyr (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, similarities in the active site probably account for the observed sensitivity to human enzyme inhibitors observed in R. mucilaginosa.

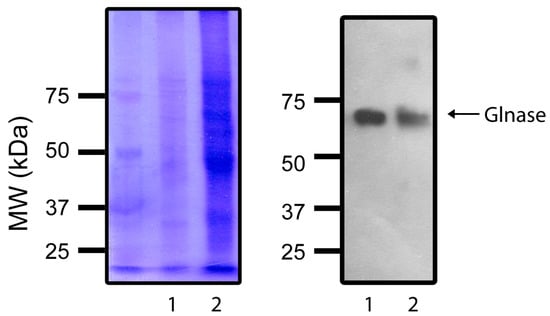

3.6. The Glnase from R. mucilaginosa Cross-Reacts with a Mammalian Glnase Antibody

The sequence similarities between R. mucilaginosa and human GLS1 was low (Supplementary Figure S1), casting doubts on whether these enzymes might have enough common characteristics to be used as models for the same inhibitors. Thus, it was decided to evaluate whether they were detected by the same antibody. The result indicates that the antibody used reacted against both enzymes (Figure 7). In fact, as expected from their similar MW, both enzymes migrated the same distance in the gel.

Figure 7.

PAGE: Coomassie stain (Left) and Western blot (Right) of (1) human Glnase 1 and R. mucilaginosa Glnase (2). Experimental conditions as described in methods. Left gel shows a Coomassie stain showing a MW ladder plus Lane (1) with proteins from a HeLa cell GLS1 sample and Lane (2) With proteins from R. mucilaginosa. Right gel: The same gel was transferred to a poly(vinylidene-difluoride) membrane, and a Western blot assay was performed. The antibody was: α-Glutaminase primary antibody (Sc-100533), from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

4. Discussion

Unicellular and pluricellular eukaryotes share most metabolic pathways, even if differences in some isoenzymes exist [36]. Thus, yeasts have been used as models for diverse biochemical studies, where short duplication times, high yields, non-pathogenicity in most, and their efficient genome manipulation provide many advantages [37]. Among yeasts, Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been the most studied organism. However, other species have been useful for studies such as Yarrowia lipolytica, that has been an important tool to define the structure of Complex I as it contains the same number of subunits as the mammalian enzymes with the advantage of expressing an alternative NADH dehydrogenase type 2, which opens the possibility of dissecting and/or inactivating complex I without killing the cell [38] or the composition of mitochondrial respiratory super complexes, which vary depending on the growth phase [39]. Debaryomyces hansenii has been used to define its mitochondrial respiratory chain composition and it has been observed that in contrast with most other organisms, this halophilic yeast increases its coupling efficiency at high NaCl concentrations [40]. R. mucilaginosa has allowed us to study alternative dehydrogenases plus the protective effect of its carotenoids against reactive oxygen species [41,42]. Association of cytoplasmic enzymes with mitochondria was first described in yeast, where GAPDH or hexokinase may be associated with VDAC [43]. Also, the Warburg effect is common to both tumors and yeasts, and it has been shown that fructose-1,6-bisphosphate is an important factor to control metabolism in all Crabtree-positive species [44,45].

Gln is an exceedingly important nutrient for the survival of tumors in their acidic, hypoxic environment [46,47]. The rapid, disorganized cell growth in tumors results in deformed, inefficient blood vessels that fail to provide both oxygen and nutrients [8]. With a high metabolic rate and low glucose availability, they turn to anaplerotic reactions [9,10]. Amino acid deamination is needed to incorporate carbon skeletons into the Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis [6]. The main anaplerotic entrance to the Krebs cycle is glutaminase, which eliminates the amido nitrogen in the lateral chain, yielding glutamate, which is then transaminated to become α-ketoglutarate [6]. Thus, in chemotherapy, Glnase inhibition is an obvious therapeutic target. Searching for ideal Glnase inhibitors and modeling the metabolic modifications calls for a simple, easy-to-use, non-pathogenic model. With this in mind, we decided to search for a yeast capable of growing on Gln as the sole carbon source, which is a trait exhibited by tumor cells [48,49,50]. Sensitivity to two Gln metabolism inhibitors was detected, suggesting that R. mucilaginosa might be an adequate model to study mammalian tumor-like metabolism. In addition to the results on R. mucilaginosa reported here, the opportunistic yeast Candida albicans has been reported to grow on Gln alone [51].

R. mucilaginosa may be considered a polyextremophile [3] as it can survive in hypoxia [41], at high concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [16]. Also, the Rhodotorula spp. surround themselves with an exopolysaccharride that chelates heavy metals found in industrially contaminated waters [52]. Here, R. mucilaginosa grew using Gln as its sole carbon source, thus resembling the highly resistant mammalian cells found in tumors. In addition, its growth was inhibited by two drugs used to inhibit Gln metabolism in tumors opening the possibility of using this yeast to screen for other possible chemical agents targeting Gln metabolism. Additionally, even though the similarities in primary sequence were not high, the active site residues were partially conserved in both humans and yeast. The similarity in Glnases from mammalians and R. mucilaginosa was also evidenced by the cross reactivity against a mammalian antibody shown by Western blotting. Lastly, in agreement with the suggestion that Glnases in these species are similar, the yeast Glnase was inhibited by DON, a widely used tumor inhibitor of Gln metabolism [28], and by CB-839, a non-competitive inhibitor of mammalian Glnase. All these data suggest that Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is an adequate tool to evaluate mammalian-Glnase inhibitors.

In addition to its proposed role to detect possible tumor metabolism inhibitors, the role of Gln metabolism in tumor treatment seems to hold great potential. In this regard, the Glnase from R. mucilaginosa should be analyzed further because it may hold promise in tumor treatment. It might be possible to purify this Glnase and use it to deplete extracellular Gln in tumors. This approach has been applied using both fungal and bacterial exoenzymes. Among these, the Glnase from Aspergillus versicolor has been especially successful [14].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010036/s1, Supplementary Figure S1. Glutaminase multiple protein alignment. Residues marked with (*) identical residues; (:) conservative substitutions; and (.) semiconservative substitutions. Residues for glutamate binding pocket are show in yellow. Semiconserved: Green and non-conserved in gray.

Author Contributions

P.I.A.-V.: original draft, visualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, conceptualization. O.M.-R.: writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, supervision, project administration, investigation, funding acquisition, formal analysis, conceptualization C.R.-G.: writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, visualization, validation, methodology, conceptualization. N.C.-F.: writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, visualization, investigation, data curation. S.U.C.: visualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, project administration, investigation, funding acquisition, formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declared that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was partially funded by research grants to SUC: from SECIHTI CF2023-I-199 and from UNAM/DGAPA/PAPIIT IN211224. PAV has a Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) research-assistant fellowship CVU 1291695. CRG is a PhD SECIHTI fellow, CVU 966402 enrolled in the Ciencias Bioquímicas Program at UNAM and OMR has a Postdoctoral fellowship from SECIHTI CVU 639365.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical assistance of Juán Barbosa and Ivet Rosas in the computer department.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Glnase | Glutaminase |

| DON | 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine |

| Gln | Glutamine |

| MS | Synthetic Glycolytic medium |

| NB | Nitrogen-based medium |

| Gln-NB | Nitrogen-based medium with Gln |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| VDAC | Voltage-dependent anion channel |

References

- Pikuta, E.V.; Hoover, R.B.; Tang, J. Microbial extremophiles at the limits of life. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 33, 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal-Kischinevzky, C.; Romero-Aguilar, L.; Alcaraz, L.D.; López-Ortiz, G.; Martínez-Castillo, B.; Torres-Ramírez, N.; Sandoval, G.; González, J. Yeasts inhabiting extreme environments and their biotechnological applications. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, T.M.; Toksoy Öner, E. Microbial exopolysaccharide production by polyextremophiles in the adaptation to multiple extremes. FEBS Lett. 2025, 599, 3417–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baidouri, F.; Zalar, P.; James, T.Y.; Gladfelter, A.S.; Amend, A.S. Evolution and physiology of amphibious yeasts. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 75, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, C.; Cheng, P.; Yu, G. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa-alternative sources of natural carotenoids, lipids, and enzymes for industrial use. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ko, B.; Hensley, C.T.; Jiang, L.; Wasti, A.T.; Kim, J.; Sudderth, J.; Calvaruso, M.A.; Lumata, L.; Mitsche, M.; et al. Glutamine oxidation maintains the TCA cycle and cell survival during impaired mitochondrial pyruvate transport. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluntun, A.A.; Lukey, M.J.; Cerione, R.A.; Locasale, J.W. Glutamine metabolism in cancer: Understanding the heterogeneity. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrado-Castellarnau, M.; de Atauri, P.; Cascante, M. Oncogenic regulation of tumor metabolic reprogramming. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 62726–62753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O. The metabolism of carcinoma cells. J. Cancer. Res. 1925, 9, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, T.N.; Shelton, L.M. Cancer as a metabolic disease. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, H.W.; Fusari, S.A.; Jakubowski, Z.L.; Zora, J.G.; Bartz, Q.R. 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine, a new tumor-inhibitory substance. II. Isolation and characterization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 3075–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotná, K.; Tenora, L.; Slusher, B.S.; Rais, R. Therapeutic resurgence of 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) through tissue-targeted prodrugs. Adv. Pharmacol. 2024, 100, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.F.; El-Shenawy, F.S.; El-Gendy, M.M.A.; El-Bondkly, E.A.M. Purification, characterization, and anticancer and antioxidant activities of l-glutaminase from Aspergillus versicolor Faesay4. Int. Microbiol. 2021, 24, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, L.; Gao, J.; Lin, C.; Wu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Targeting glutaminase 1 (GLS1) by small molecules for anticancer therapeutics. Eur. J. Medic. Chem. 2023, 252, 115306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda-Martínez, E.; Chiquete-Félix, N.; Castañeda-Tamez, P.; Ricardez-García, C.; Gutiérrez-Aguilar, M.; Uribe-Carvajal, S.; Mendez-Romero, O. In Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, active oxidative metabolism increases carotenoids to inactivate excess reactive oxygen species. Front. Fungal Biol. 2024, 5, 1378590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, N.S.; Calahorra, M.; González, J.; Defosse, T.; Papon, N.; Peña, A.; Coria, R. Contribution of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1 to the halotolerance of the marine yeast Debaryomyces hansenii. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Moguel, I.; Costa-Silva, T.A.; Pillaca-Pullo, O.S.; Flores-Santos, J.C.; Freire, R.K.B.; Carretero, G.; da Luz Bueno, J.; Camacho-Córdova, D.I.; Santos, J.H.P.M.; Sette, L.D.; et al. Antarctic yeasts as a source of L-asparaginase: Characterization of a glutaminase-activity free L-asparaginase from psychrotolerant yeast Leucosporidium scottii L115. Process Biochem. 2023, 129, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfeld, E.; Marble, S.J.; Meister, A. Enzymatic synthesis of γ-glutamylhydroxamic acid from glutamic acid and hydroxylamine. J. Biol. Chem. 1963, 238, 3711–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Higgins, D.G. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLaBarre, B.; Gross, S.; Fang, C.; Gao, Y.; Jha, A.; Jiang, F.; Song, J.J.; Wei, W.; Hurov, J.B. Full-length human glutaminase in complex with an allosteric inhibitor. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 10764–10770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Vet. Parasitol. 1976, 98, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araiza-Olivera, D.; Chiquete-Felix, N.; Rosas-Lemus, M.; Sampedro, J.G.; Peña, A.; Mujica, A.; Uribe-Carvajal, S. A glycolytic metabolon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is stabilized by F-actin. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 3887–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Orefice, A.; Guerrero-Castillo, S.; Luévano-Martínez, L.A.; Peña, A.; Uribe-Carvajal, S. Mitochondria from the salt-tolerant yeast Debaryomyces hansenii (halophilic organelles?). J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2010, 42, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Orefice, A.; Guerrero-Castillo, S.; Díaz-Ruíz, R.; Uribe-Carvajal, S. Oxidative phosphorylation in Debaryomyces hansenii: Physiological uncoupling at different growth phases. Biochimie 2014, 102, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderwaeren, L.; Dok, R.; Voordeckers, K.; Nuyts, S.; Verstrepen, K.J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model system for eukaryotic cell biology, from cell cycle control to DNA damage response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberg, K.M.; Vornov, J.J.; Rais, R.; Slusher, B.S. We’re Not “DON” Yet: Optimal dosing and prodrug delivery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, M.; Piras, C.; Leoni, V.P.; Casula, M.; Simbula, G.; Noto, A.; Lilliu, K.; Kopeć, K.K.; Serreli, G.; Murgia, F.; et al. Glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 causes metabolic adjustments in colorectal cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.; Pramanik, S.; Williams, L.J.; Hodges, H.R.; Hudgens, C.W.; Fischer, G.M.; Luo, C.K.; Knighton, B.; Tan, L.; Lorenzi, P.L.; et al. The Glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 (Telaglenastat) enhances the antimelanoma activity of T-cell–mediated immunotherapies. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durá, M.A.; Flores, M.; Toldrá, F. Purification and characterization of a glutaminase from Debaryomyces spp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 76, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, R.C.; Edwin Seegmiller, J. The inhibition by 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine of glutamine catabolism of the cultured human lymphoblast. J. Cell. Physiol. 1977, 93, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rais, R.; Jančařík, A.; Tenora, L.; Nedelcovych, M.; Alt, J.; Englert, J.; Rojas, C.; Le, A.; Elgogary, A.; Tan, J.; et al. Discovery of 6-Diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) prodrugs with enhanced CSF delivery in monkeys: A potential treatment for glioblastoma. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 8621–8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, C.-W.; Kang, J.; Sadra, A.; Huh, S.-O. Glutamine increases stability of TPH1 mRNA via p38 mitogen-activated kinase in mouse mastocytoma cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Niu, X.; Su, Y.; Ye, X.; Li, W.; Zeng, W.; Zhao, X.; He, Z.; Dong, Q.; Zhou, X.; et al. DON-loaded nanodrug-T cell conjugates with PD-L1 blockade for solid tumor therapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2501815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Mentel, M.; van Hellemond, J.J.; Henze, K.; Woehle, C.; Gould, S.B.; Yu, R.Y.; van der Giezen, M.; Tielens, A.G.; Martin, W.F. Biochemistry and evolution of anaerobic energy metabolism in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 444–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002, 350, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerscher, S.; Dröse, S.; Zwicker, K.; Zickermann, V.; Brandt, U. Yarrowia lipolytica, a yeast genetic system to study mitochondrial complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2002, 1555, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Cruz, G.; Esparza-Perusquía, M.; Cruz-Cárdenas, A.; Cruz-Vilchis, D.; Flores-Herrera, O. Kinetic characterization of respirasomes and free complex I from Yarrowia lipolytica. Mitochondrion 2025, 83, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xelhuantzi, M.S.C.; Ghete, D.; Milburn, A.; Ioannou, S.; Mudd, P.; Calder, G.; Ramos, J.; O’Toole, P.J.; Genever, P.G.; MacDonald, C. High-resolution live cell imaging to define ultrastructural and dynamic features of the halotolerant yeast Debaryomyces hansenii. Biol. Open 2024, 13, bio060519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Tamez, P.; Chiquete-Félix, N.; Uribe-Carvajal, S.; Cabrera-Orefice, A. The mitochondrial respiratory chain from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, an extremophile yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2024, 1865, 149035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rosario, D.; Pardo, J.P.; Guerra-Sánchez, G.; Vázquez-Meza, H.; López-Hernández, G.; Matus-Ortega, G.; González, J.; Baeza, M.; Romero-Aguilar, L. Analysis of the respiratory activity in the Antarctic yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa M94C9 reveals the presence of respiratory supercomplexes and alternative elements. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Saavedra, C.; Morgado-Martínez, L.E.; Burgos-Palacios, A.; King-Díaz, B.; López-Coria, M.; Sánchez-Nieto, S. Moonlighting proteins: The case of the hexokinases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 701975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Ruiz, R.; Uribe-Carvajal, S.; Devin, A.; Rigoulet, M. Tumor cell energy metabolism and its common features with yeast metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2009, 1796, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, N.; Rosas-Lemus, M.; Uribe-Carvajal, S.; Rigoulet, M.; Devin, A. The Crabtree and Warburg effects: Do metabolite-induced regulations participate in their induction? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2016, 1857, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Schafer, X.L.; Ambeskovic, A.; Spencer, C.M.; Land, H.; Munger, J. Addiction to coupling of the Warburg Effect with glutamine catabolism in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, M.; Yao, D.; Wu, L.; Luo, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. Targeting the Warburg effect: A revisited perspective from molecular mechanisms to traditional and innovative therapeutic strategies in cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 953–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, L.M.; Huysentruyt, L.C.; Seyfried, T.N. Glutamine targeting inhibits systemic metastasis in the VM-M3 murine tumor model. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 2478–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.; Augur, Z.M.; Li, M.; Hill, C.; Greenwood, B.; Domin, M.A.; Kondakci, G.; Narain, N.R.; Kiebish, M.A.; Bronson, R.T.; et al. Therapeutic benefit of combining calorie-restricted ketogenic diet and glutamine targeting in late-stage experimental glioblastoma. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranaka, H.; Akinsola, R.; Billet, S.; Pandol, S.J.; Hendifar, A.E.; Bhowmick, N.A.; Gong, J. Glutamine supplementation as an anticancer strategy: A potential therapeutic alternative to the convention. Cancers 2024, 16, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.R.; Collings, A.; Farnden, K.J.F.; Shepherd, M.G. Ammonium assimilation by Candida albicans and other yeasts: Evidence for activity of glutamate synthase. Microbiology 1989, 135, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Garza, M.T.; Perez, D.B.; Rodriguez, A.V.; Garcia-Gutierrez, D.I.; Zarate, X.; Cantú Cardenas, M.E.; Urraca-Botello, L.I.; Lopez-Chuken, U.J.; Trevino-Torres, A.L.; Cerino-Córdoba, J.; et al. Metal-induced production of a novel bioadsorbent exopolysaccharide in a native Rhodotorula mucilaginosa from the mexican northeastern region. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.