The Effects of Trichilia claussenii Extract on the Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi Produced by Submerged Fermentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Entomopathogenic Fungi and Isolation

2.2. Submerged Fermentation (FS)

2.3. Characterization of Fungal Isolates

2.3.1. Spore Count

2.3.2. Colony-Forming Units

2.3.3. Analytical Procedures: Specific Density

2.4. Kinetics

2.5. Enzymatic Activities

2.5.1. Chitinase Enzymatic Analysis

2.5.2. β-1,3-Glucanase Enzymatic Analysis

2.6. Analyses of Trichoderma asperelloides

2.6.1. Molecular Identification of Trichoderma asperelloides

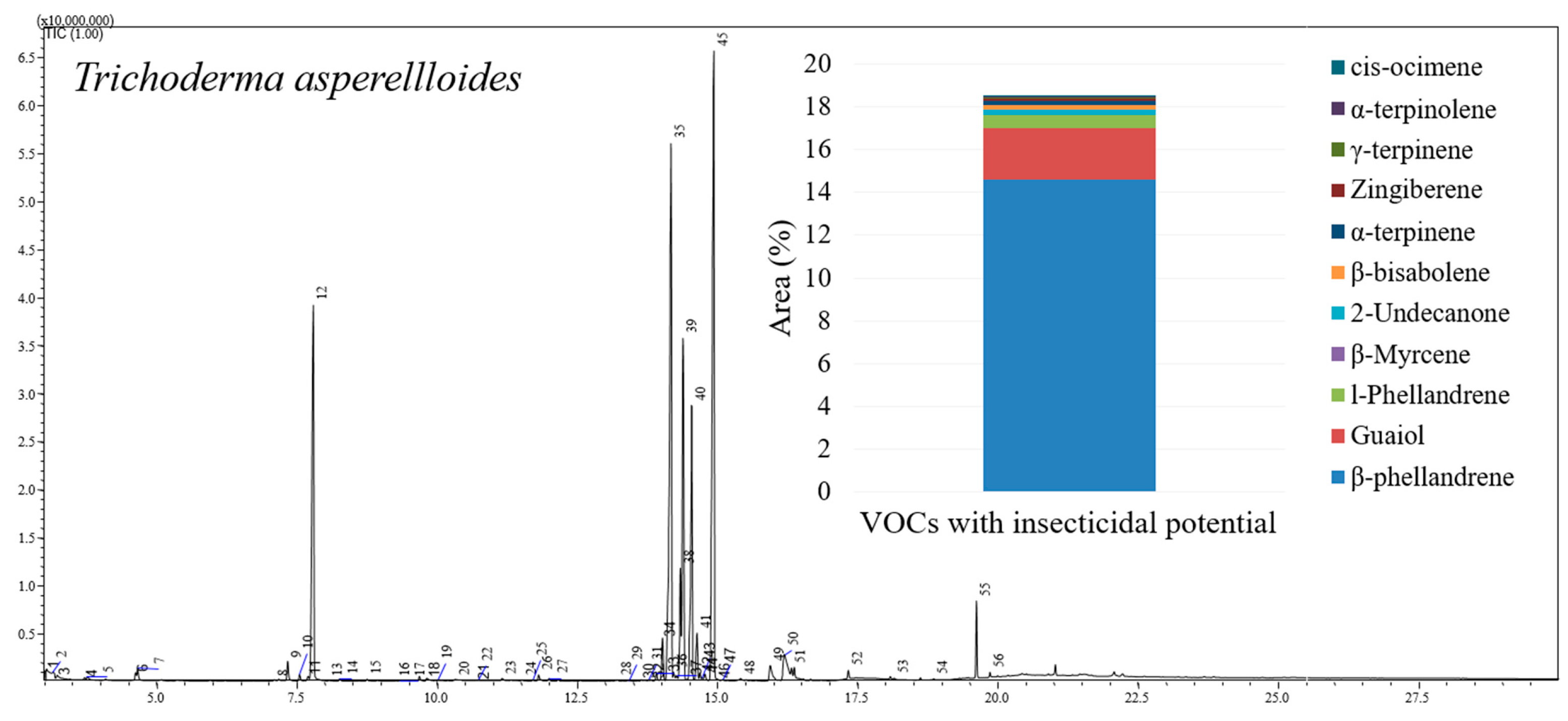

2.6.2. Chromatographic Analysis of Trichoderma asperelloides

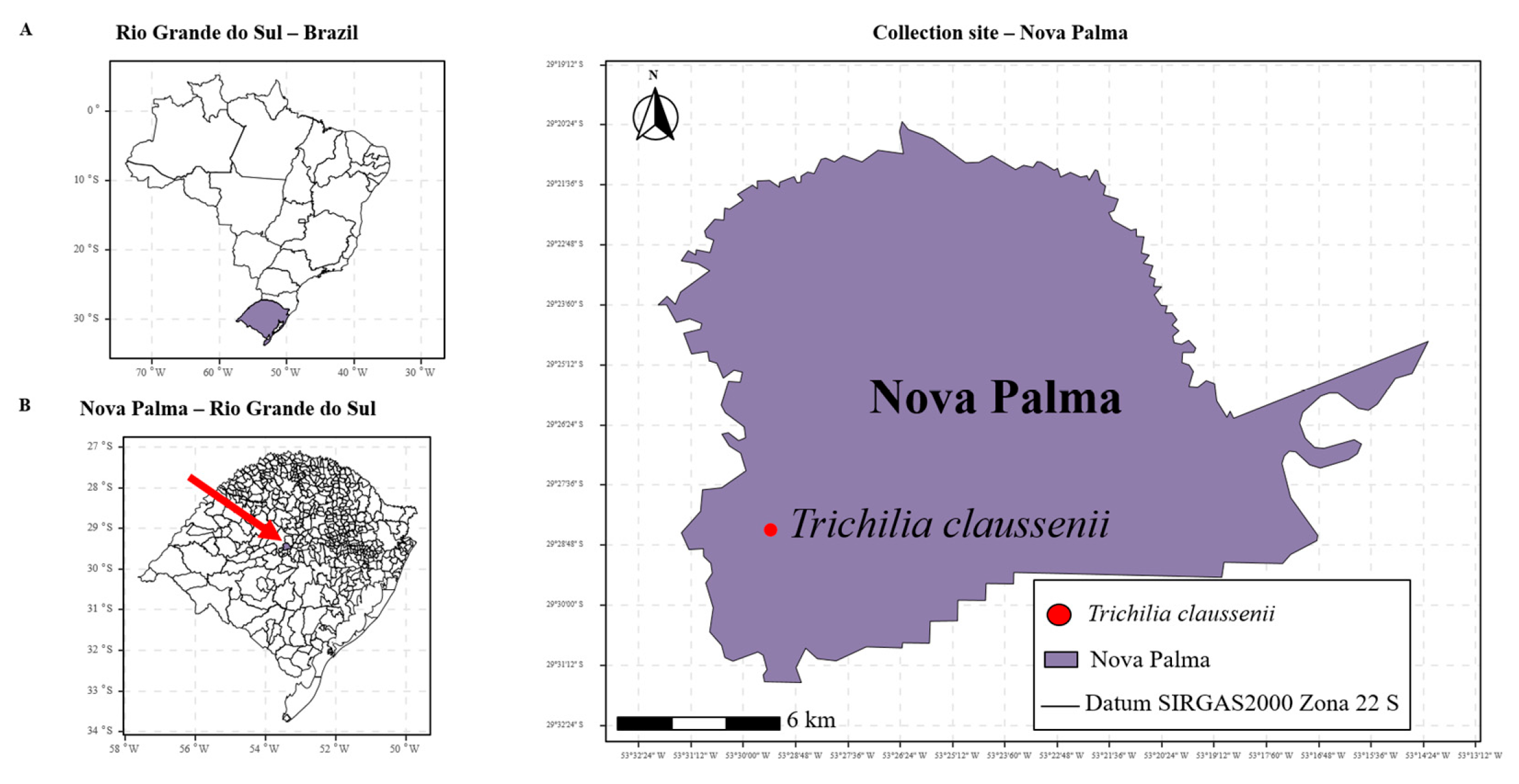

2.7. Trichilia claussenii: Collection Site and Sample Preparation

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

2.8. Bioassays

2.8.1. Rearing of Pest Insects

2.8.2. In Vitro Bioassay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chromatographic Analysis of Trichoderma asperelloides

3.2. Characterization of Isolates

3.3. Kinetics

3.4. Bioassays

3.4.1. Euschistus heros

3.4.2. Spodoptera frugiperda

4. Discussion

4.1. Chromatographic Analysis of Trichoderma Asperelloides

4.2. Characterization of Isolates

4.3. Kinetics

4.4. Bioassays

4.4.1. Euschistus heros

4.4.2. Spodoptera frugiperda

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maurya, R.P.; Koranga, R.; Smal, I.; Chaudhary, D.; Paschapur, A.U.; Sreedhar, M.; Manimala, R.N. Biological control: A global perspective. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 3203–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.; Szczepaniec, A. Endophytic entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents of insect pests. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 6033–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihal, R.; Al-Khayri, J.M.; Banu, A.N.; Kudesia, N.; Ahmed, F.K.; Sarkar, R.; Arora, A.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Entomopathogenic Fungi: An Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Sustainable Nanoparticles and Their Nanopesticide Properties. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamisile, B.S.; Akutse, K.S.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Xu, Y. Model application of entomopathogenic fungi as alternatives to chemical pesticides: Prospects, challenges, and insights for next-generation sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 741804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Luo, J.; Li, C.; Eleftherianos, I.; Zhang, W.; Xu, L. A life-and-death struggle: Interaction of insects with entomopathogenic fungi across various infection stages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1329843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Golo, P.S.; Ribeiro-Silva, C.S.; Muniz, E.R.; Franco, A.O.; Kobori, N.N.; Fernandes, E.K. Advances in submerged liquid fermentation and formulation of entomopathogenic fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngegba, P.M.; Cui, G.; Khalid, M.Z.; Zhong, G. Use of Botanical Pesticides in Agriculture as an Alternative to Synthetic Pesticides. Agriculture 2022, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ody, L.P.; Ferraz, A.d.B.F.; de Mello, E.; Ugalde, G.; Mazutti, M.A.; Tres, M.V.; Zabot, G.L. Trichilia claussenii (Meliaceae): A Review of Its Biological and Phytochemical Activities and a Case Study of Composition. Processes 2025, 13, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, M.S.; Nogueira, T.S.; Azevedo, O.A.; Curcino, M.G.; Terra, W.S.; Braz-Filho, R.; Vieira, I.J. Limonoids from the genus Trichilia and biological activities: Review. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 20, 1055–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, L. Insecticidal Triterpenes in Meliaceae III: Plant Species, Molecules, and Activities in Munronia–Xylocarpus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaid, K.; Furze, J. Botanical-microbial synergy—Fundaments of untapped potential of sustainable agriculture. J. Crop Health 2024, 76, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Nora, D.; Piovesan, B.C.; Bellé, C.; Stacke, R.S.; Balardin, R.R.; Guedes, J.V. Isolation and evaluation of entomopathogenic fungi against the neotropical brown stink bug Euschistus heros (F.) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) under laboratory conditions. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, E.M.; Filho, H.P. Manual Básico de Técnicas Fitopatológicas; Embrapa Mandioca E Frutic: Cruz das Almas, Brazil, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 1–109. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Vermelho, A.B.; Pereira, A.F.; Coelho, R.R.; Souto-Padrón, T.C. Práticas de Microbiologia, 2nd ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 1–225. Available online: https://minhabiblioteca.com.br/catalogo/livro/79199/pr-ticas-de-microbiologia (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Mahgoub, S.A.; Kedra, E.G.A.; Abdelfattah, H.I.; Abdelbasit, H.M.; Alamoudi, S.A.; Al-Quwaie, D.A.; Selim, S.; Alsharari, S.S.; Saber, W.I.A.; El-Mekkawy, R.M. Bioconversion of Some Agro-Residues into Organic Acids by Cellulolytic Rock-Phosphate-Solubilizing Aspergillus japonicus. Fermentation 2022, 8, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Yang, Y.; Kim, J. Purification and characterization of chitinase from Streptomyces sp. M-2. BMB Rep. 2003, 36, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, K.; Iwata, J.; Yamazaki, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Tomai, Y. Purification and characterization of a yeast lytic β-1,3-glucanase from Oerskovia xanthineolytica TK-1. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1994, 78, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, B.; Zeilinger, S.; Wiesenberger, G.; Schofbeck, D.; Schuhmacher, R. Detection and Identification of Fungal Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds by HS-SPME-GC–MS. In Laboratory Protocols in Fungal Biology: Current Methods in Fungal Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, G.L.; Leppla, N.C.; Dickerson, W.A. Velvetbean caterpillar: A rearing procedure and artificial medium. J. Econ. Entomol. 1976, 69, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1925, 3, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, C.F.; Maldonado, Y.E.; Cumbicus, N.; Gilardoni, G. The Essential Oil from Cupules of Aiouea montana (Sw.) R. Rohde: Chemical and Enantioselective Analyses of an Important Source of (–)-α-Copaene. Plants 2025, 14, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.; Melo, N.C.; Ruiz, A.L.; Floglio, M.A. Antiproliferative activity from five Myrtaceae essential oils. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e14612340536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteggiano, A.; Occhipinti, A.; Capuzzo, A.; Mecarelli, E.; Aigotti, R.; Medana, C. Quali–Quantitative Characterization of Volatile and Non-Volatile Compounds in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand Resin by GC–MS Validated Method, GC–FID and HPLC–HRMS2. Molecules 2021, 26, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, L.A.; Oguntoye, O.S.; Ismaeel, R.O. Phytochemical profile, antioxidant anda antidiabetic potential of essential oil from fresh and dried leaves of Eucalyptus globulis. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2022, 67, 5453–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slougui, N.; Rabhi, N.; Achouri, R.; Bensouici, C. Evaluation of the antioxidant, antifungal and anticholinesterase activity of the extracts of Ruta montana L., Harvested from Souk-Ahras (North-East of Algeria) and composition of its extracts by GC-MS. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 7, 3452–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Ali, Z.; Hawwal, M.F.; Khan, I.A. Chemical Characterization and Quality Assessment of Copaiba Oil-Resin Using GC/MS and SFC/MS. Plants 2023, 12, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, B.d.A.; Silva, R.C.; Andrade, E.H.d.A.; Setzer, W.N.; da Silva, J.K.; Figueiredo, P.L.B. Seasonality, Composition, and Antioxidant Capacity of Limonene/δ-3-Carene/(E)-Caryophyllene Schinus terebinthifolia Essential Oil Chemotype from the Brazilian Amazon: A Chemometric Approach. Plants 2023, 12, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrini, A.; Tacchini, M.; Chiocchio, I.; Grandini, A.; Radice, M.; Maresca, I.; Paganetto, G.; Sacchetti, G. A Comparative Study on Chemical Compositions and Biological Activities of Four Amazonian Ecuador Essential Oils: Curcuma longa L. (Zingiberaceae), Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf, (Poaceae), Ocimum campechianum Mill. (Lamiaceae), and Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae). Antibiotics 2023, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.Y.; Zhang, M.X.; Sun, M.; Wan, L.S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.S. Discovering potential fumigants against Tribolium castaneum from essential oils using GC-MS and chemometric approaches. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 110, 102485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, M.H.; Lopes, L.R.; Ferreira, M.J.; Spadari, C.C.; Ishida, K.; Tangerina, M.M.; Núnez, E.G.; Sannomiya, M. Antifungal profiling of Brazilian essential oils: Chemotype classification and correlation with bioactivity. Acta Sci. Technol. 2025, 47, e71290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, K.B.; Carocho, M.; Finimundy, T.; Resende, O.; Célia, J.A.; Gomes, F.P.; Quequeto, W.D.; Bastos, J.C.; Barros, L. Analysis of volatiles of rose pepper fruits by GC/MS: Drying kinetics, essential oil yield, and external color analysis. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 1963261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagáň, Ľ.; Apacsová Fusková, M.; Hlávková, D.; Skoková Habuštová, O. Essential Oils: Useful Tools in Storage-Pest Management. Plants 2022, 11, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, H.; Mei, L.; Wang, Y. Trichoderma atroviride LZ42 releases volatile organic compounds promoting plant growth and suppressing Fusarium wilt disease in tomato seedlings. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka, J.; Szymczak, K.; Skwarek-Fadecka, M.; Małolepsza, U. Toward the Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds from Tomato Plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Treated with Trichoderma virens or/and Botrytis cinerea. Cells 2023, 12, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Xu, L.; Lin, K. Multitrophic and Multilevel Interactions Mediated by Volatile Organic Compounds. Insects 2024, 15, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazazzara, V.; Vicelli, B.; Bueschl, C.; Parich, A.; Pertot, I.; Schuhmacher, R.; Perazzolli, M. Trichoderma spp. volatile organic compounds protect grapevine plants by activating defense-related processes against downy mildew. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1950–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochmann, F.; Flatschacher, D.; Speckbacher, V.; Zeilinger, S.; Heuschneider, V.; Bereiter, S.; Schiller, A.; Ruzsanyi, V. Demonstrating the applicability of proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry to quantify volatiles emitted by the mycoparasitic fungus Trichoderma atroviride in real time: Monitoring of Trichoderma-based biopesticides. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 35, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslahi, N.; Kowsari, M.; Zamani, M.; Motallebi, M. The profile change of defense pathways in phaseouls vulgaris L. by biochemical and molecular interactions of Trichoderma harzianum transformants overexpressing a chimeric chitinase. Biol. Control 2021, 152, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekanandhan, P.; Swathy, K.; Lucy, A.; Sarayut, P.; Patcharin, K. Entomopathogenic fungi based microbial insecticides and their physiological and biochemical effects on Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith). Front. Cell. Microbiol. 2023, 11, 1254475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, S.; He, L.; Lin, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, R.; Wang, K. Biochemical analyses of a new GH18 chitinase from Beauveria bassiana KW1 and its synergy with a commercial protease on silkworm exuviae hydrolysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0128525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuna, H.B.; Lim, H.-I.; Moon, J.-H.; Won, S.-J.; Choub, V.; Choi, S.-I.; Yun, J.-Y.; Ahn, Y.S. The Prospect of Hydrolytic Enzymes from Bacillus Species in the Biological Control of Pests and Diseases in Forest and Fruit Tree Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umaru, F.F.; Simarani, K. Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungal Formulations against Elasmolomus pallens (Dallas) (Hemiptera: Rhyparochromidae) and Their Extracellular Enzymatic Activities. Toxins 2022, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, C.; Bautista, E.; García, L.; Murcia, J.C.; Barrera, G. Assessment of fungal lytic enzymatic extracts produced under submerged fermentation as enhancers of entomopathogens Biological Activity. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Y.; Alarcón, K.A.; Ortiz, C.; Santos-Holguín, J.; García-Riaño, J.; Mejía, C.; Amaya, C.; Uribe-Gutiérrez, L. Isolation and characterization of a native strain of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana for the control of the palm weevil Dynamis borassi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in the neotropics. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirapara, K.M.; Bhatt, S.B.; Umaretiya, V.R.; Parakhia, M. Exploring agricultural soils of the Saurashtra region for entomopathogenic bacteria and fungi: Isolation, characterization and phylogenetic analysis. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, J.G.; Palacios, S.A.; Pastor, N.; Giordano, F.D.; Rovera, M.; Reynoso, M.M.; Venisse, J.S.; Torres, A.M. Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma harzianum ITEM 3636 against peanut brown root rot caused by Fusarium solani RC 386. Biol. Control 2021, 164, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, C.L.; Boscolo, M.; da Silva, R.; Gomes, E.; da Silva, R. Fungal endo and exochitinase production, characterization, and application for Candida biofilm removal. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 2267–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.C.; Miranda, R.F.; Costa, F.A.; Ulhoa, C. Potential of Trichoderma piluliferum as a biocontrol agent of Colletotrichum musae in banana fruits. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 34, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F.; Chen, D.; Ren, S.; Manman, Z.; Hou, J.; Liu, T. Screening and identification of Trichoderma strains isolated from natural habitats in China with potential agricultural applications. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 7913950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelizza, S.A.; Ferreri, N.A.; Elíades, L.A.; Galarza, B.; Cabello, M.N.; Russo, M.L.; Vianna, F.; Scorsetti, A.C.; Lange, C.E. Enzymatic activity and virulence of Cordyceps locustiphila (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) on the South American locust Schistocerca cancellata (Orthoptera: Acrididae). J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2021, 33, 101411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.G.; Castellanos, L.N.; Ortiz, N.A.; González, A.G. Control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) using Trichoderma asperellum and Metarhizium anisopliae in different pepper types. BioControl 2019, 64, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazhnikova, Y.; Belimov, A.; Ignatova, L.; Mukasheva, T.; Karpenyuk, T.; Goncharova, A. The Antagonistic Activity of Beneficial Fungi and Mechanisms Underlying Their Protective Effects on Plants Against Phytopathogens. Sustainability 2025, 17, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Santana, M.F.; Alves, L.F.; Ferreira, T.T.; Bonini, A.K. Selection and characterisation of Beauveria bassiana fungus and their potential to control the brown stink bug. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, T.D.; Sanches, A.C.; Cruz, M.A.; Prado, T.J.; Savi, P.J.; Polanczyk, R.A. Mortality of Diatraea saccharalis is affected by the pH values of the spore suspension of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae. Rev. Ceres 2022, 69, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, N.; Pironti, A.; Manganiello, G.; Marra, R.; Vinale, F.; Vitalee, S.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S.L. Trichoderma species problematic to the commercial production of Pleurotus in Italy: Characterization, identification, and methods of control. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 1301–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antara, N.H.; Stephan, D. Chitin-amended media: Improving efficacy of Cordyceps fumosorosea as a control agent of Cydia pomonella. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2025, 210, 108296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, I.; Jamian, S.; Saad, N.; Abdullag, S.; Hata, E.M.; Jalinas, J.; Ismail, S.I. Identification and virulence of entomopathogenic fungi, Isaria javanica and Purpureocillium lilacinum isolated from the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Malaysia. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2023, 33, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.M.; Quintela, E.D.; Boaventura, H.A.; Silva, J.F.; Tripode, B.M.; Miranda, J.E. Selection of entomopathogenic fungi to control stink bugs and cotton boll weevil. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 2023, 53, e76316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.C.; Portela, V.O.; Lima, J.C.; Gisloti, L.J.; Botelho, A.S.; Amarante, C.B. Atividade inseticida de Montrichardia linifera contra Euschistus heros (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Rev. Interdiscip. Univ. Fed. Tocantins 2025, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, I.O.; Araíjo, S.H.; Toledo, P.F.; Lima, G.; Salustiano, I.V.; Alves, J.R.; Mantilla-Afanador, J.G.; Kohlhoff, M.; Oliveora, E.; Leite, J.P. Potential of Ficus carica extracts against Euschistus heros: Toxicity of major active compounds and selectivity against beneficial insects. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4638–4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, A.Y.; Ventura, M.U.; Andrei, C.C. Brown stink bug mortality by seed extracts of tephrosia vogelii containing deguelin and tephrosin. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2018, 61, e18180028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, A.; Afzal, A.; Qadir, Z.A.; Li, J. Bioassays of Beauveria bassiana Isolates against the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, F.; Zandi-Sohani, N.; Parizipour, M.H.; Ebadollahi, A. Synergic effects of some plant-derived essential oils and Iranian isolates of entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae Sorokin to control Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1075761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelly, N.; Reflinaldon; Meriqorina, S.R. Effective concentration of entomopathogens Beauveria bassiana (Bals) vuil as biological control agents for Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1160, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalte, O.P.; Panchbhai, P.R.; Pillai, T.; Lavhe, N.V. Bio-efficacy Evaluation of Beauveria bassiana against Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith). Hexapoda 2024, 6, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Y.; Pineda-Guillermo, S.; Tamez-Guerra, P.; Orozco-Flores, A.A.; de la Rosa, J.I.F.; Ramos-Ortiz, S.; Chavarrieta-Yáñez, J.M.; Martínez-Castillo, A.M. Natural Prevalence, Molecular Characteristics, and Biological Activity of Metarhizium rileyi (Farlow) Isolated from Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) Larvae in Mexico. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, V.; Kannan, S.; Alford, L.; Pittarate, S.; Krutmuang, P. Study on the virulence of Metarhizium anisopliae against Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith, 1797). J. Basic Microbiol. 2024, 64, 2300599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afandhi, A.; Fernando, I.; Widjayanti, T.; Maulidi, A.K.; Radifan, H.I.; Setiawan, Y. Impact of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), invasion on maize and the native Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) in East Java, Indonesia, and evaluation of the virulence of some indigenous entomopathogenic fungus isolates for controlling the pest. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Abd-Elgalil, D.M.; Barry, M.M.; Mohamed, G.S. Evaluation of the potential toxicity of plant extracts, pathogenic fungi, and chemical pesticides for the management of Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorres-Acosta, R.; Felipe-Victoriano, M.; Garay-Martínez, J.; Torres, R. Biological control of Spodoptera frugiperda J. E. Smith and Schistocerca piceifrons piceifrons Walker using entomopathogenic fungi. Agro Prod. 2023, 16, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xie, W.; Ye, J.; Zhabg, T.; Li, D.; Zhi, J. New potential strains for controlling Spodoptera frugiperda in China: Cordyceps cateniannulata and Metarhizium rileyi. BioControl 2020, 65, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, B.; Duarte, V.; Silva, D.M.; Mascarin, G.M.; Júnior, I.D. Comparative analysis of blastospore production and virulence of Beauveria bassiana and Cordyceps fumosorosea against soybean pest. BioControl 2020, 65, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugti, G.A.; Chen, H.; Bin, W.; Rehman, A.; Rehman Ali, F. Pathogenic effects of entomopathogenic fungal strains on fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) larvae. Int. J. Vet. Res. Allied Sci. 2024, 4, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjare, J.; Tambo, T.R. Evaluation of the insecticidal activity of the extracts of Trichilia emetica, Trichilia capitata, and Azadirachta indica against the Spodoptera frugiperda (Fall Armyworm) on maize crop. Alger. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 9, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Anzúres, J.; Aragón-García, A.; Pérez-Torres, B.C.; López-Olguín, J.F. Actividad biológica de un extracto de Semillas de Trichilia havanensis Jacq.1 sobre larvas de Spodoptera exigua (Hübner). Southwest. Entomol. 2017, 42, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Majeed, M.Z.; Sayed, S.; Albogami, B.Z.; Al-Shuraym, L.; Safdar, H.; Haq, I.; Raza, A.B. Synergized toxicity exhibited by indigenous entomopathogenic fungal strains, plant extracts and synthetic insecticides against fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) under laboratory and semi-field conditions. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2023, 130, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, M.; Lozano, L. Synergistic larvicidal activity of Metarhizium anisopliae and Azadirachta indica extract against the malaria vector Anopheles albimanus. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2023, 43, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Victoriano, M.; Villegas-Luján, R.; Treviño-Cueto, D.; Sánchez-Peña, S.R. Combined activity of natural products and the fungal entomopathogen Cordyceps farinosa against Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Fla. Entomol. 2023, 106, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, C.; Du, G.; Wang, G.; Tu, X.; Zhang, Z. Synergy in efficacy of Artemisia sieversiana crude extract and Metarhizium anisopliae on resistant Oedaleus asiaticus. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 642893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspitarini, R.D.; Fernando, I.; Widjayanti, T.; Ihsan, M. Compatibility of the aqueous leaf extract of Mimosa pudica and the entomo-acaropathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana in controlling the broad mite Polyphagotarsonemus latus (Acari: Tarsonemidae). Persian J. Acarol. 2022, 11, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, S.; Elarnaouty, S.A.; Ali, E. Suitability of five plant species extracts for their compatibility with indigenous Beauveria bassiana against Aphis gossypii Glov. (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2021, 31, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogorni, P.; Vendramim, J. Efeito subletal de extratos aquosos de Trichilia spp. sobre o desenvolvimento de Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) em Milho. Neotrop. Entomol. 2003, 34, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, Y.A.; Verawaty, M.; Herlinda, S. Development of Spodoptera frugiperda fed on young maize plant’s fresh leaves inoculated with endophytic fungi from South Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2022, 23, 5056–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayiragije, J.C.; Özek, T.; Karaca, I. Effects of spores and raw entomotoxins from Beauveria bassiana BMAUM-M6004 on Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2023, 43, 1783–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, W.H.; Ghaly, M.F.; Tantawy, W.G.; El-Shafeiy, S.N. Detection of some secondary metabolites of Beauveria bassiana and the potential effects on Spodoptera littoralis. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.R. Comparing the efficiency of fungal spores and their metabolites in some entomopathogenic fungi against cotton leaf worm, Spodoptera littoralis. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2023, 11, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evren, G.; Korlom, Y.; Saboori, A.; Cakmak, I. Exploring the potential of Trichoderma secondary metabolites against Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Invert. Pathol. 2025, 211, 108299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, B.; Verma, S. Unveiling the biocontrol potential of Trichoderma. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 167, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, B.; Xu, J.; Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Ali, S. Characterization and Toxicity of Crude Toxins Produced by Cordyceps fumosorosea against Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) and Aphis craccivora (Koch). Toxins 2021, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.F.; dos Santos, M.S.N.; Araújo, B.A.; Kerber, B.D.; Oliveira, H.A.P.; Guedes, J.V.C.; Mazutti, M.A.; Tres, M.V.; Zabot, G.L. Co-Cultivations of Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Trichoderma harzianum to Produce Bioactive Compounds for Application in Agriculture. Fermentation 2025, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fungal Isolate | Strain/Origin |

|---|---|

| Beauveria bassiana | IBCB 66/Biological Institute (São Paulo, Brazil) |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | IBCB 425/Biological Institute (São Paulo, Brazil) |

| Trichoderma asperelloides | Organic Soil/Guandu Agroecological Group (Santa Maria, Brazil) |

| Isaria javanica | URM 7662/Celtic Bioinsecticide-Ballagro (Bom Jesus dos Perdões, Brazil) |

| Cordyceps fumosorosea | ESALQ-1296/ESALQ-USP (São Paulo, Brazil) |

| Isolated | Matrix Quantity (g L−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Sucrose | Polypeptide | NaNO3 | (NH4)2SO4 | Additive a | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 20.0 | 0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 14.0 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Trichoderma asperelloides | 5.0 | 0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Isaria javanica | 5.0 | 0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Cordyceps fumosorosea | 5.0 | 0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Compound | Area (%) | Retention Time (min) | LRICalc a | LRILit b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-phellandrene | 14.604 | 7.785 | 1033 | 1025 | [22] |

| Guaiol | 2.402 | 16.190 | 1642 | 1600 | [23] |

| l-phellandrene | 0.600 | 7.330 | 1005 | 1002 | [24] |

| β-Myrcene | 0.268 | 7.090 | 991 | 990 | [25] |

| 2-Undecanone | 0.227 | 11.805 | 1293 | 1255 | [26] |

| β-bisabolene | 0.219 | 14.685 | 1514 | 1505 | [27] |

| α-terpinene | 0.208 | 7.540 | 1018 | 1014 | [28] |

| Zingiberene | 0.086 | 14.725 | 1517 | 1493 | [29] |

| γ-terpinene | 0.072 | 8.260 | 1062 | 1060 | [30] |

| α-terpinolene | 0.049 | 8.745 | 1091 | 1088 | [31] |

| cis-ocimene | 0.022 | 8.065 | 1050 | 1032 | [32] |

| Fungi | Spore Concentration (Spores mL−1) | CFU (mL−1) * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | Isolate + T. claussenii | ||

| Beauveria bassiana | (8.33 ± 0.28) × 108 | (1.23 ± 0.03) × 108 b | (1.55 ± 0.05) × 108 a |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | (1.33 ± 0.03) × 108 | (4.07 ± 0.06) × 107 b | (7.40 ± 0.72) × 107 a |

| Trichoderma asperelloides | (9.42 ± 0.62) × 107 | (1.95 ± 0.05) × 107 b | (3.12 ± 0.03) × 107 a |

| Isaria javanica | (3.61 ± 0.10) × 108 | (3.13 ± 0.23) × 106 a | (2.43 ± 0.05) × 106 b |

| Cordyceps fumosorosea | (3.54 ± 0.07) × 108 | (1.57 ± 0.12) × 107 a | (1.30 ± 0.10) × 107 b |

| Fungi | Specific Density of the Broth (g cm−3) | Enzymatic Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | Isolate + T. claussenii | Chitinase (U mL−1) | β-1,3-Glucanase (U mL−1) | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 1.003239 | 1.002296 | 0.82 ± 0.48 | 0.42 ± 0.01 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 1.006147 | 1.004663 | 1.07 ± 0.70 | 2.40 ± 0.09 |

| Trichoderma asperelloides | 1.003151 | 0.984247 | 1.18 ± 0.32 | 1.30 ± 0.06 |

| Isaria javanica | 1.003875 | 1.001002 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

| Cordyceps fumosorosea | 1.003805 | 1.002017 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ody, L.P.; Gomes, L.R.d.M.; Ugalde, G.; Soares, F.d.S.; Guedes, J.V.C.; Tonato, D.; Mazutti, M.A.; Tres, M.V.; Zabot, G.L. The Effects of Trichilia claussenii Extract on the Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi Produced by Submerged Fermentation. Fermentation 2026, 12, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010038

Ody LP, Gomes LRdM, Ugalde G, Soares FdS, Guedes JVC, Tonato D, Mazutti MA, Tres MV, Zabot GL. The Effects of Trichilia claussenii Extract on the Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi Produced by Submerged Fermentation. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleOdy, Lissara Polano, Leonardo Ramon de Mesquita Gomes, Gustavo Ugalde, Franciéle dos Santos Soares, Jerson Vanderlei Carús Guedes, Denise Tonato, Marcio Antonio Mazutti, Marcus Vinícius Tres, and Giovani Leone Zabot. 2026. "The Effects of Trichilia claussenii Extract on the Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi Produced by Submerged Fermentation" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010038

APA StyleOdy, L. P., Gomes, L. R. d. M., Ugalde, G., Soares, F. d. S., Guedes, J. V. C., Tonato, D., Mazutti, M. A., Tres, M. V., & Zabot, G. L. (2026). The Effects of Trichilia claussenii Extract on the Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi Produced by Submerged Fermentation. Fermentation, 12(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010038