Abstract

The industrial transition to advanced biofuels is currently limited by the metabolic constraints and low inhibitor tolerance of wild-type microbial hosts. This review justifies the necessity of Precision Fermentation (PF) as the pivotal technological framework to overcome these barriers, providing a systematic synthesis of high-resolution genetic tools and intelligent bioprocess architectures. We analyze how the integration of CRISPR-Cas9, retron-mediated recombineering, and synthetic regulatory circuits enables the development of specialized microbial “chassis” capable of achieving 10- to 100-fold higher yields compared to native organisms, with industrial titers reaching 50 g/L for isobutanol and 25 g/L for farnesene. A major novelty of this work is the critical evaluation of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Soft Sensing, and Digital Twins in orchestrating real-time metabolic control and mitigating the toxic effects of advanced alcohols and drop-in hydrocarbons (C15–C20). Furthermore, the study concludes that the “scale-out” modular strategy, when integrated into hybrid thermochemical-biochemical biorefineries, allows for the full valorization of C5/C6 sugars and lignin, achieving a Minimum Selling Price (MSP) competitive with fossil fuels. By mapping the synergy between advanced metabolic engineering and data-driven process optimization, this review establishes PF as an indispensable driver for achieving carbon-neutral and carbon-negative energy systems in the circular bioeconomy.

1. Introduction

The environmental and health consequences of reliance on nonrenewable energy sources are evident in the heightened frequency and severity of extreme climatic events. The primary cause of this phenomenon is the combustion of fossil fuels, intensified by climate change and the release of harmful atmospheric pollutants in recent decades [1]. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) states that the climate crisis has exacerbated droughts, floods, and heatwaves, emphasizing the imminent threat these events pose to lives and livelihoods and highlighting the need for urgent measures to mitigate the damage [2].

In response to the unsustainability of fossil-based energy sources and the need to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with targets of a 45% reduction by 2030 and the achievement of global net-zero emissions by 2050, the search for renewable alternatives, such as biofuels, has gained prominence [3,4]. This option is considered promising for the transition toward a cleaner and more sustainable energy matrix, particularly considering the growing contribution of renewables, which accounted for approximately 11.2% of global final energy consumption in 2019 and about 29% of worldwide electricity generation in 2020 [3,5]. The large-scale utilization of biofuels is not merely an ambition but a consolidated industrial reality, as evidenced by current production volumes. In 2024, the United States led the global market with a production output of 1.917 petajoules, followed by Brazil and Indonesia, which produced 1.143 and 459 petajoules, respectively. Within the European context, Germany emerged as the leading producer, ranking among the top five global producers with an output of 149 petajoules [6].

Within this context, biofuels emerge as a strategic component of the renewable energy portfolio, as they are derived from renewable resources and generally exhibit a lower environmental impact, contributing to the reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, by up to 86% [7,8,9]. Among biofuels, bioethanol remains the dominant liquid biofuel worldwide, accounting for approximately 65% of global production; however, first-generation (1G) routes based on food crops face sustainability constraints related to land use, food security, and environmental degradation [10]. Consequently, increasing attention has been directed toward next-generation biofuels produced from lignocellulosic biomass, an abundant and low-cost resource that does not compete with food supply, although its complex structure still imposes significant techno-economic challenges due to the energy-intensive steps required for pretreatment, hydrolysis, and fermentation [11,12].

Despite biofuels being a more environmentally friendly alternative to fossil fuels, they still face significant challenges related to sustainability and large-scale economic viability. Microbial bioconversion processes are crucial for producing low-cost biofuels but require significant capital and operational investments, which significantly increase the overall process cost. Numerous microbial species can transform lignocellulosic substrates into various biofuels; however, the efficiency of this conversion is directly contingent upon the inherent metabolic traits of each microorganism [13].

Precision fermentation (PF) and metabolic engineering emerge as promising strategies to accelerate the development of bioenergy, expanding microbial bioconversion beyond advanced alcohols to include syngas-derived fuels and biohydrogen as strategic energy carriers [14,15,16,17]. In this scenario, wild microorganisms, naturally limited by low productivity and inefficient regulation, can be enhanced through the insertion of specific genes, enabling the simultaneous utilization of C5 and C6 sugars, increasing tolerance to inhibitory compounds, and improved titer, rate, and yield (TRY) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Simultaneously, synthetic biology expands the potential of these strategies by enabling the design and construction of artificial genetic circuits using modern tools such as CRISPR–Cas9, MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering), and comprehensive “omics” platforms (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics). This integration has facilitated the development of highly efficient microorganisms capable of converting renewable feedstocks into biofuels in a more economical, scalable, and environmentally sustainable manner [18,26].

Although several reviews have addressed individual aspects of microbial biofuel production, most focus on specific fuel classes, organisms, or genetic tools in isolation. Given this panorama, the present review article provides a comprehensive and integrative analysis of recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives in biofuel production, positioning precision fermentation as a technological frontier in the transition toward a low-carbon and potentially carbon-neutral energy matrix. Specifically, this review addresses the fundamental principles of precision fermentation, the main strategies of microbial engineering, and the application of modern molecular and digital tools, while systematically integrating these advances across multiple biofuel production pathways and their incorporation into biorefinery systems.

2. Fundamentals of Precision Fermentation

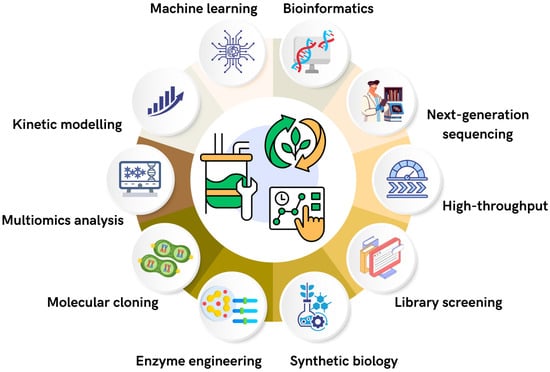

Precision Fermentation (PF) comprises strategies designed to optimize the production of high-value compounds such as food ingredients, enzymes, bioactive metabolites, pigments, and biofuels, while ensuring high yields, purity, and traceability. This approach is intricately connected to metabolic engineering and incorporates various disciplines and tools (Figure 1), including bioinformatics, molecular analyses, omics studies, kinetic modeling, bioprocess development, genetic engineering, and, more recently, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) [27].

Figure 1.

Key technological pillars supporting precision fermentation: integration of computational, molecular, and bioprocess tools for high-value bioproduct synthesis.

In the realm of biofuels, PF has focused on increasing production efficiency and yield by refining industrial processes through enhanced cellular stress tolerance, improved conversion of fermentable sugars, and metabolic optimization of biosynthetic pathways [28]. Another important aspect involves the development of bioengineered enzymes (e.g., xylanases, cellulases, pectinases, and amylases) to enhance stability, specificity, and catalytic efficiency in the transformation of lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars [29].

This approach supports productive value chains by enabling the use of agricultural byproducts and other organic residues, in which microorganisms are genetically modified (GM) to grow and produce target metabolites under critical conditions, thereby reducing bottlenecks and enhancing the utilization of natural resources [30]. Thus, PF aligns with the global demand for eco-efficient and sustainable processes capable of delivering clean, traceable, and environmentally responsible production [31].

2.1. Microbial Engineering: Common Platforms (Yeasts, Bacteria, Algae, Synthetic Consortia)

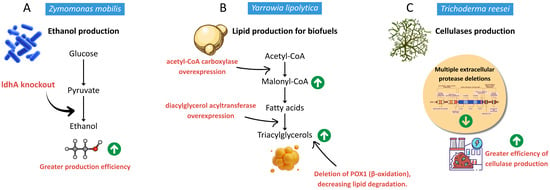

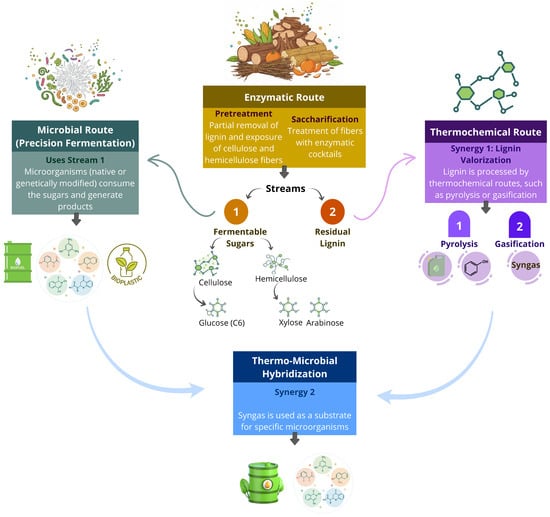

PF integrates multiple engineering steps (Figure 2), which typically begin with the selection of a microbial platform capable of hosting and expressing the genes responsible for producing the target compound, commonly referred to as the “chassis”. Microorganisms classified as GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) are preferentially employed due to their well-established history of industrial use, including bacteria, yeasts, and filamentous fungi [32]. The continuous advancement of the field has driven the exploration of new chassis and the development of more efficient biotechnological processes [33]. The choice of a chassis depends on factors such as ease of genetic manipulation, the presence of native biosynthetic pathways, safety, and adaptability to fermentation conditions [34]. Table 1 lists examples of metabolic engineering strategies in different species.

Figure 2.

Representative metabolic engineering strategies in precision fermentation. (A) Ethanol pathway optimization in Zymomonas mobilis through deletion of ldh, reducing lactate formation and redirecting carbon flux to ethanol [35]. (B) Lipid overproduction in Yarrowia lipolytica via ACC1 and DGA1 overexpression combined with POX1 deletion, enhancing triacylglycerol accumulation [36]. (C) Improved cellulase secretion in Trichoderma reesei through deletion of protease-encoding genes and promoter strengthening of cbh1 [37].

2.1.1. Yeast Chassis: Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Emerging Species

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is recognized as a model yeast due to its ease of cultivation, robust stress tolerance, well-characterized metabolism, and rapid growth. The Brazilian strain UFMG-CM-Y257 has been reported to exhibit a high specific growth rate on sucrose (0.57 ± 0.02 h−1) together with a high ethanol yield (1.65 ± 0.02 mol ethanol per mol of hexose equivalent) [38,39]. A study comparing ethanol production across Candida stellata, Hanseniaspora uvarum, Kloeckera apiculata, Saccharomycodes ludwigii, Torulaspora delbrueckii and S. cerevisiae reported values of 5.50, 4.60, 4.82, 6.50, 6.38 and 6.42 percent v/v, respectively. S. cerevisiae also showed the highest specific growth rate, reinforcing its broader advantage in fermentation processes [40].

Besides S. cerevisiae, several emerging yeast species have demonstrated strong potential as microbial chassis for PF. Yarrowia lipolytica can accumulate lipids and metabolize lignocellulosic waste streams, such as fatty acids, glycerol, and acetate, which are key substrates for the production of biofuels and oleochemicals. Kluyveromyces marxianus is thermotolerant and grows rapidly on different substrates, including agricultural residues and dairy byproducts, showing potential for bioethanol production [41]. Yeasts of the genus Rhodotorula stand out for performing high-cell-density fermentations, converting substrates such as lignocellulose and glycerol, and enhancing the synthesis of fatty acids and alcohols when GM [42].

2.1.2. Bacterial Chassis: Escherichia coli and Solventogenic Strains

Bacterial chassis offers broad metabolic diversity and remains an essential platform in precision fermentation. Escherichia coli is still the most widely used platform due to its rapid growth and low nutritional cost and is capable of producing both alcohols and intermediates for fuels. Studies consistently show that this bacterium grows considerably faster than native solvent-producing species, reaching maximal specific growth rates of approximately 0.7 to 0.8 h−1 on glucose, whereas organisms such as Clostridium acetobutylicum typically achieve only 0.2 to 0.3 h−1. This disparity results in increased carbon flux and superior biofuel production performance in engineered E. coli strains. Other notable bacterial chassis include Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas putida, Clostridium acetobutylicum, and Corynebacterium glutamicum [43,44,45].

2.1.3. Phototrophic Systems and Filamentous Fungi

Microalgae differ from other platforms due to their photosynthetic capacity and high potential for lipid and biofuel production. Although they still face challenges related to industrial-scale cultivation, advances in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering have begun to address these limitations [46]. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is the primary model organism owing to its robust set of molecular tools and well-annotated genome, and it is widely used in studies of lipid metabolism. Expanding beyond this model, the current status of other promising platforms high-lights the impact of precision engineering: Nannochloropsis oceanica leverages RNA Pol I-based systems to achieve eightfold higher transgene expression for tailored fatty acid production; Synechocystis sp. has reached titers of 230 mg·L−1 of 1-alkenes through CRISPR-mediated strategies; Chlorella sorokiniana is capable of accumulating 13% lutein; and Monoraphidium neglectum offers the unique advantage of sustained growth during nitrogen-limited lipid accumulation. These advancements overcome previous production challenges, positioning these species as effective industrial hosts for a wide range of bioproducts [46].

Although filamentous fungi do not directly produce biofuels, they supply key enzymatic systems used in both 1G (corn-based) ethanol and second-generation (2G) lignocellulosic ethanol production, facilitating polysaccharide hydrolysis and increasing sugar availability for fermentative microorganisms. Among filamentous fungi, Trichoderma reesei and Aspergillus niger stand out for their high secretory potential and enzymatic synthesis capacity, with strains already engineered to produce xylanases, cellulases, and α-L-arabinofuranosidases [27,47]. Thus, their use in microbial consortia can enhance biomass pretreatment and the release of fermentable sugars. This strategy can significantly impact production, as synthetic consortia based on metabolic engineering enable more robust and cooperative processes in which the complementary activities of different species improve the overall performance of fermentation [48].

The enhancement of microorganisms, combined with computational tools, further optimizes bioprocessing performance. Research shows that machine learning techniques such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) and support vector machines (SVMs) can accurately predict (R2 > 0.93) growth, biomass formation, and lipid accumulation during fermentation. This integration of genetic algorithms and SVMs reveals competitive relationships between lipid maximization and biomass production, suggesting important trade-offs in industrial processes [49].

Table 1.

Metabolic engineering strategies of microorganisms for the biosynthesis of alcohol-based biofuels.

Table 1.

Metabolic engineering strategies of microorganisms for the biosynthesis of alcohol-based biofuels.

| Microorganism | Type of Biofuel | Metabolic Engineering Strategy | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Ethanol | Co-culture of two modified strains: one uses only glucose (xylR deletion) and the other only xylose (xylR mutation + deletions in ptsI, ptsG, galP, glk) | Production of 0.49 g/L/h and 46 g/L ethanol | [50] |

| Two-phase, two-temperature strategy with temperature-inducible promoters controlling glucose pathways; insertion of pdc and adhB from Zymomonas mobilis | Production of 127 g of ethanol from 260.9 g of sugars; productivity 4.06 g/L | [51] | ||

| Isoprenoid alcohols | The strategies included overexpression of the nudB and IspA genes via a heterologous MVA pathway; increased production through AphA phosphatase overexpression and idi modulation; use of an IspA mutant to redirect C10 alcohols synthesis | Production of 2027 mg/L of isoprenoid alcohols (C5–C15) and derivatives, with composition modulation by idi expression | [52] | |

| Isobutanol | Use of Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway to balance redox, inactivation of acid byproduct genes, expression to tuning to increase isobutanol flux | Production of 15.0 g/L of isobutanol, yield of 0.37 g isobutanol/g glucose | [53] | |

| Modified E. coli W (ldhA, adhE, pta, frdA deletions) + constitutive promoter library for isobutanol pathway | Production of up to 20 g/L of isobutanol using cheese whey as substrate | [54] | ||

| S. cerevisiae | Isobutanol | Overexpression of ZNF1, and deletion/reduction in BUD21, insertion of genes for isobutanol pathway + xylose metabolism (XR-XDH, xylose transporter, xylulokinase) | Production of 14.8 g/L of isobutanol, equivalent to 155.9 mg/g of xylose consumed (264.75% increase vs. control) | [55] |

| Elimination of competing pathways (LPD1 deletion) + overexpression of pyruvate carboxylase, malate dehydrogenase, and malic enzyme, activating an alternative transhydrogenase-like pathway | Production of 1.62 g/L of isobutanol from 100 g/L of glucose, with a yield of 0.016 g/g of glucose consumed in 24 h | [56] | ||

| Ethanol | Sequential gene deletion (GPD1, ALD6, NDE1/NDE2) + heterologous SeEutE expression for acetic acid tolerance and hypoxic fermentation | E5 strain showed a 200% increase in fermentation rate, consuming 25% of acetic acid | [57] | |

| Heterologous xylA expression from Burkholderia cenocepacia + adaptive evolutionary engineering via sequential batch culture with xylose | Ethanol yield and productivity 13% (0.51 × 0.45 g/g) and 120% (0.42 × 0.19 g/g cells·h) higher than the non-evolved strain, in addition to eliminating xylitol accumulation | [58] | ||

| Isoprenol | Insertion of mevalonate pathway for isoprenol biosynthesis; IPP (isopentenyl diphosphate) bypass construction; deletion of promiscuous kinase that diverted metabolic flux; bottlenecks identification via metabolomics + overexpression of promiscuous alkaline phosphatase | Production of 383.1 mg/L of isoprenol | [59] | |

| Octanol | Chain-length engineered FAS1 (Fas1R1834K/Fas2) → octanoyl-CoA → hydrolysis to octanoic acid → heterologous CAR expression (Mycobacterium marinum) + Sfp (B. subtilis) → reduction to 1-octanol → Ahr (Escherichia coli) overexpression | Achieved 26.0 ± 3.6 mg/L 1-octanol after 72 h; Ahr over-expression reached 49.5 ± 0.8 mg/L; also accumulated ~90 mg/L octanoic acid, identified growth toxicity of even ~50 mg/L 1-octanol for yeast | [19] | |

| Propanol | Artificial pathway: pyruvate → citramalate (cimA) → 2 KB; tdcB overexpression; enhanced thrA/B/C; GLY1 deletion | High density anaerobic fermentation produced 180 mg/L 1-propanol from glucose in the engineered strain | [20] | |

| Clostridium sp. | Butanol | Deletion of six histidine kinase (HK) genes via CRISPR-Cas9. | Butanol production increased by 40.8% (13.8 g/L) and 17.3% (11.5 g/L) compared to the wild strain; productivity increased by 40% and 20%, respectively | [21] |

| Push-pull engineering: ter overexpression to direct the flow of acetyl-CoA → butyryl-CoA; acid reassimilation pathway decoupled from acetone production to redirect carbon from butyrate and acetate to butyryl-CoA; deletion of xylR and araR + overexpression of xylT | The modified strain produced 4.96 g/L of n-butanol from corn cob, demonstrating a 235-fold increase compared to the wild strain | [22] | ||

| Overexpression of adhE2 and Ck hbd, coupling NADP+/NADPH metabolism to butanol biosynthesis to increase acetyl-CoA flux and the supply of reducing equivalents | A 50–60% increase in butanol production (0.24–0.28 vs. 0.15–0.18 g/g) and up to 4.5 times the butanol/ethanol and alcohol/acid ratios | [23] | ||

| Ethanol | Inactivation of adhE and deletion of aor1 and aor2, via ClosTron and allelic exchange mutagenesis, redirecting the metabolic flow of the acetogenic pathway towards ethanol formation | The inactivation of adhE led to an increase of up to 180% in autotrophic ethanol production | [24] | |

| Hexanol e Butanol | Insertion of gene clusters from C. kluyveri, C. acetobutylicum and Clostridium carboxidivorans via CRISPR-Cas9, expanding the biosynthesis pathway of hexanol and butanol alcohols | Production of 1075 mg/L of butanol and 133 mg/L of hexanol from fructose; 174 mg/L of butanol and 15 mg/L of hexanol from gas (CO2/H2); after further integration, 158 mg/L of butanol and 251 mg/L of hexanol | [25] |

Metabolic engineering strategies of microorganisms for the biosynthesis of alcohol-based biofuels. Summary of studies employing genetic and metabolic modifications in bacteria and yeasts to enhance alcohol production (ethanol, isobutanol, propanol, octanol, among others). Gene names are italicized to distinguish them from protein names.

2.2. Engineering Strategies for Microbial Chassis in PF

Innovation in PF is fundamentally driven by the rational engineering of microbial chassis, supported by advanced metabolic engineering and synthetic biology tools designed to reprogram metabolic pathways for the efficient production of target compounds. Genome editing strategies, including targeted mutagenesis and CRISPR-Cas systems, have been widely applied to optimize microbial performance by increasing the yields of both native metabolites and recombinant products. Synthetic biology and pathway engineering extend these approaches by enabling the construction and refinement of heterologous pathways, improving substrate utilization efficiency and allowing the use of low-cost and renewable feedstocks [33].

2.2.1. Genome Editing Technologies

CRISPR-Cas (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats associated with Cas proteins) is a system derived from the adaptive immune machinery of bacteria and archaea that has been repurposed as a highly precise and programmable genome editing tool. It introduces double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci guided by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), which recognizes the target DNA sequence in conjunction with a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), typically 5′-NGG-3′ in the case of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9). The Cas9 nuclease is composed of two catalytic domains, the histidine–asparagine–histidine (HNH) and RuvC-like (RuvC) endonuclease domains, organized into a recognition (REC) lobe and a nuclease (NUC) lobe, which together cleave both DNA strands several nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [60].

Following DNA cleavage, the resulting double-strand breaks are repaired by microbial cells through either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), enabling controlled deletions, insertions, or nucleotide substitutions. These repair outcomes provide a mechanistic foundation for the application of CRISPR–Cas9 in metabolic engineering, where precise genome modifications are required to redirect metabolic fluxes, enhance product yields, and improve cellular robustness. Accordingly, in fermentation biotechnology, CRISPR–Cas9 has become the platform of choice for microbial engineering, in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic, due to its high specificity, efficiency, and multiplexing capability, facilitating the redesign of metabolic pathways and the development of high-performance industrial microorganisms, including chassis such as Escherichia coli and Clostridium spp. [60,61].

Bibliometric analyses indicate that CRISPR-Cas9 has played a pivotal role in accelerating the development of fourth-generation (4G) biofuels. The precise engineering of microorganisms has enabled enhanced lipid accumulation, optimization of biomass-to-fuel conversion pathways, and improved tolerance to environmental stresses, inhibitory compounds, and the biofuels themselves. By integrating genome editing with metabolic engineering, this approach helps overcome the classical cost and yield limitations associated with earlier biofuel generations, enabling the use of residual feedstocks and crops cultivated on marginal soils. Moreover, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated modification of lignin composition in agricultural residues simplifies biomass pretreatment and reduces processing costs in bioethanol production, positioning advanced biofuels as a strategy aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals related to clean energy and climate action, while opening new avenues for synthetic biology-driven pathway redesign and systems-level metabolic reengineering [62].

More recently, retron-mediated recombineering has emerged as a powerful genome editing strategy that exploits single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors generated in vivo by bacterial retrons during DNA replication, enabling the continuous and homology-dependent introduction of precise genetic modifications. In this system, a retron cassette is programmed to produce a multicopy ssDNA molecule carrying the desired mutation, flanked by sequences homologous to the upstream and downstream regions of the target locus. This ssDNA is synthesized by the retron-encoded reverse transcriptase from a non-coding msr/msd RNA (multicopy single-stranded RNA/multicopy single-stranded DNA), a retron-specific RNA structure in which the msr region acts as the RNA scaffold for reverse transcription, while the msd region encodes the single-stranded DNA donor. Incorporation occurs preferentially at the replication fork, particularly on the lagging strand, with the assistance of a single-stranded DNA annealing protein (SSAP), which promotes homologous pairing and homology-directed repair. As a result, the engineered mutation is progressively fixed in daughter strands over successive cell generations, enabling scalable and multiplexed genome editing [63].

This method has stood out due to its higher editing efficiency and the removal of the necessity for multiple cycles of external oligonucleotide introduction. The characteristics of this methodology enable editing in various phylogenetically distant bacterial species, including those where CRISPR is inefficient or unfeasible, making it a valuable alternative for industrial and environmental chassis that are underexplored in PF. Its effectiveness has already been demonstrated in bacterial chassis, including E. coli, Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Vibrio natriegens, Aeromonas hydrophila, Shewanella oneidensis, Erwinia amylovora, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. putida, Pseudomonas syringae, Acinetobacter baylyi, Limosilactobacillus reuteri, Streptococcus suis, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and Cutibacterium acnes [64].

2.2.2. Synthetic Biology and Pathway Engineering

Synthetic biology is broadly defined as the systematic application of engineering principles to design new biological systems or to redesign existing ones by controlling genetic and metabolic components to perform specific functions, such as increasing efficiency, productivity, or enabling novel functionalities in microorganisms, including the production of next-generation biofuels. In this context, pathway engineering refers to the deliberate design and modification of metabolic routes within host organisms through strategies such as the construction of synthetic pathways, overexpression of rate-limiting enzymes, and deletion of competing pathways. These approaches aim to redirect metabolic fluxes toward the biosynthesis of advanced biofuels and are often implemented through the integrated use of genome editing tools and metabolic engineering frameworks [65].

Within the framework of advanced biofuel production, synthetic biology plays a central role by enabling the design of novel metabolic pathways and the construction of platform microorganisms capable of synthesizing molecules beyond ethanol and biodiesel, such as terpenoids and fusel alcohols, which can be further upgraded into fuels with higher energy density. In this context, microbial chassis such as P. putida, extensively engineered to valorize lignin-derived compounds into high-value intermediates, and Clostridium species modified to redirect acetyl-CoA from the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (WLP) toward the production of longer-chain alcohols, including hexanol, exemplify how synthetic biology and metabolic engineering strategies are broadening the portfolio and improving the yields of advanced biofuels [66].

Pathway engineering is a core strategy for constructing platform microorganisms capable of producing biofuels and biochemicals at near-industrial levels by fine-tuning metabolic fluxes and mitigating the accumulation of toxic intermediates. Multilevel modulation strategies, including gene copy number, promoter and ribosome-binding site strength, enzyme scaffolding, and pathway compartmentalization, enable precise control over enzyme expression and localization, thereby maximizing TRY of key precursors such as fatty acids, alcohols, and terpenoids. Notably, the integration of dynamic sensing and regulatory elements has emerged as a critical advance, allowing real-time adjustment of source and sink pathways in response to intracellular metabolite levels. These developments underscore the transition from static pathway optimization toward dynamic metabolic control, which forms the foundation of regulatory circuit engineering [67].

2.2.3. Regulatory Circuits and Dynamic Metabolic Control

Gene regulatory circuits are defined as network-based representations of the interactions among the components of a gene regulation system, such as transcription factors, genes, and proteins, as well as the underlying regulatory logic that governs how information is processed and propagated through these interactions. This flow of regulatory information gives rise to dynamic system-level behaviors, including adaptive responses, oscillations, and multiple stable states, which can be exploited in biotechnological applications, such as the dynamic optimization of metabolic pathways for biofuel production [68].

In yeast systems, these regulatory principles can be implemented through the modular combination of cis-regulatory elements, such as hybrid promoters containing specific binding sites, and trans-acting activation or repression modules coupled to external signal sensors, enabling tight ON/OFF control of gene expression throughout the fermentation process. In S. cerevisiae, this approach includes the use of GAL-based promoters and orthogonal regulatory systems, such as Tet-ON/Tet-OFF circuits or temperature-responsive transcription factors, to activate or repress metabolic pathways in response to defined environmental or chemical cues. Such designs allow controlled transitions between growth phases with low metabolic burden and production phases characterized by high expression of target pathways. Overall, these synthetic regulatory architectures demonstrate how gene regulatory circuits can be rationally engineered to minimize cellular burden, enhance expression robustness across diverse cultivation conditions, and enable the dynamic modulation of complex metabolic routes, including those directed toward biofuel production [69].

Dynamic metabolic control in biofuel bioprocesses relies on synthetic regulatory circuits that adjust, in real time, the expression of pathway enzymes in response to intracellular or population-level signals, such as metabolite concentrations, cell density, or growth state, rather than maintaining static overexpression throughout fermentation. This strategy enables temporal redirection of metabolic fluxes, for instance by channeling acetyl-CoA from the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) cycle toward isopropanol production once a threshold cell density is reached through quorum-sensing systems that repress growth-associated genes while activating product-forming pathways. In parallel, metabolite-responsive regulators sensing toxic intermediates, such as acyl-CoA or farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), can dynamically repress upstream modules, including the mevalonate pathway, while activating downstream product synthesis, such as amorphadiene or biodiesel-like esters, thereby mitigating toxicity and improving yields. Additionally, circuits coupled to glycolytic flux or metabolites like acetyl phosphate have been used to trigger rate-limiting steps of production pathways only during stationary phase, reducing metabolic burden during growth and reallocating cellular resources toward high productivities in the production phase, a critical requirement for large-scale biofuel bioreactors [70].

In practical biofuel bioprocesses, these concepts have been implemented primarily in model and industrial microorganisms such as E. coli and yeasts, in which biosensor-regulator circuits dynamically adjust the expression of fuel-producing pathways in response to cues. For instance, in biodiesel and fatty acid-producing E. coli, feedback control systems have been engineered to sense the accumulation of toxic intermediates such as malonyl-CoA or acyl-CoA and accordingly up- or downregulate pathway genes, maintaining precursor levels within safe ranges while improving genetic stability and product titers. Another reported strategy involves oxygen-responsive promoters in aerobic systems, where oxygen limitation in large-scale bioreactors triggers the modulation of glucose transporter expression, reducing substrate uptake, preventing excessive acetate formation, and alleviating energetic stress during the production of advanced biofuels [71].

Modular regulatory platforms capable of sensing multiple classes of signals enable adaptive reprogramming of microbial chassis metabolism, allowing optimized responses to fluctuating bioreactor conditions and coordinated transitions between distinct fermentation stages [72]. Collectively, these advances underpin the emergence of highly customizable, intelligent, and increasingly automated fermentation processes, substantially enhancing operational flexibility, process robustness, and industrial applicability [73].

2.3. Process Monitoring and Control (Omics, Sensors, Artificial Intelligence)

PF requires rigorous monitoring and control that extends beyond the core fermentation stage. This phase is crucial for ensuring reproducibility and maintaining optimal bioprocess conditions, as optimized workflows generate large volumes of multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic), which are essential for assessing reproducibility and supporting the optimized conditions fundamental to PF [74]. To enable such intensive data collection, it becomes imperative to transition from conventional bioprocessing to smart biomanufacturing, which employs sensors for continuous data monitoring and integrates analytical algorithms, including AI-based methods capable of extracting information from massive and multidimensional datasets [75].

The integration of AI in PF has evolved from simple statistical correlations to a transversal tool for yield prediction and real-time kinetic control. ANNs, particularly Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP), have become the predominant architecture, utilized in approximately 90% of studies concerning lignocellulosic ethanol due to their superior ability to map the non-linearities of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation. Comparative studies indicate that MLP models consistently outperform Response Surface Methodology (RSM), achieving predictive accuracies of R2 ≈ 0.997 in glucose-to-ethanol conversions [76,77,78,79].

Beyond standard ANNs, a diverse array of algorithms has demonstrated exceptional robustness in complex substrates:

- Ensemble Learning: Methods such as Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and CatBoost utilize variables like Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) and volatile acid profiles to identify critical operational triggers via SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis [80,81,82].

- Deep Learning: Architectures including Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), and Transformers are increasingly applied to process temporal bioprocess data [83,84].

- Hybrid Systems: Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) provide a balance between the predictive power of neural networks and the interpretability of fuzzy logic, enabling early fault detection and process stabilization [85].

Traditionally, bioprocess monitoring relies on hardware-based sensors; however, these devices present limitations such as high cost, measurement delays, and the need for frequent maintenance, which can hinder operation under certain environmental conditions. In this context, soft sensors, also referred to as virtual or inferential sensors, integrate data-driven mathematical models with physical principles to estimate quality parameters that are difficult to measure directly. There are developed through three distinct approaches: (I) model-driven, which uses first-principles or physicochemical models; (II) data-driven, which uses statistical modeling or AI/machine learning; and (III) hybrid (gray-box), which combines data-driven and first-principles modeling. AI algorithms such as ANNs, deep neural networks (including recurrent neural networks, RNNs; long short-term memory networks, LSTMs; gated recurrent units, GRUs; and Transformers), fuzzy systems, support vector regression (SVR), principal component analysis (PCA), and evolutionary algorithms have been widely applied to soft sensin [86].

The frontier of PF lies in the deployment of Digital Twins—virtual replicas that synchronize mechanistic kinetic models with real-time data streams. A pivotal advancement is the use of Soft Sensors integrated with Raman or Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy. For instance, the application of Spatio-Temporal Convolutional Neural Networks (STC-CNN) to sequential Raman spectra has enabled the automated control of glucose feeding in fed-batch systems, reducing glycerol byproduct formation by 6.7% and increasing maximum ethanol concentrations [87,88,89].

AI has also revolutionized microbial strain design and biosynthetic pathways. AutoCRISPR speeds up development cycles by using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to guess what will happen when editing goes wrong. This cuts the time it takes from months to weeks [90]. Furthermore, the synergy between Machine Learning and Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) allows for high-level optimization; utilizing XGBoost to optimize promoter combinations has achieved yield increases of 7.4% at elevated temperatures (40 °C) in S. cerevisiae [91].

These computational architectures, coupled with evolutionary algorithms like Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), have led to typical productivity gains of 5–20%, positioning AI as an indispensable driver for the economic viability of advanced biofuels [78,92]. However, as a relatively new and rapidly evolving field, existing challenges include the lack of data standardization, the limited interpretability of AI models (essential in regulatory contexts), and the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure robust, safe, and sustainable applications [93].

3. Application in Biofuel Production

3.1. Bioethanol and Advanced Alcohols

Global bioethanol and biodiesel production between 2005 and 2018 surged from 49.9 billion to 167.9 billion liters. Bioethanol accounted for approximately 65% of this total, while biodiesel constituted around 35%. The countries with the highest bioethanol production (>80%) are the United States and Brazil, whereas the European Union leads biodiesel production. In 2022, global biofuel production was estimated at approximately 1.914 million barrels of oil equivalent per day, with a projected growth of 38 billion liters between 2023 and 2028. The primary feedstocks utilized in this process are predominantly corn grain (16.1%), followed by vegetable oil (13.5%), other feed grains (3.3%), and wheat grain (1.7%) [94,95].

Liquid biofuel production is largely dominated by alcohols, with bioethanol being the primary product, accounting for approximately 65% of global output, supported by its cleaner combustion and higher thermal efficiency [96]. Bioethanol is classified into four generations, highlighting the need to transition from 1G production (based on food crops and associated with sustainability concerns) to 2G and subsequent pathways [10,97]. Lignocellulosic biomass (2G) emerged as an abundant but uncompetitive raw material due to its inedible nature (unlike 1G materials) and recalcitrant structural matrix, which requires expensive pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis steps before fermentation. While 1G biofuels rely on readily available sugars or starches, 2G platforms utilize the carbon retained in cellulose and hemicellulose polymers from agricultural and forestry residues [11,98].

Beyond these feedstock challenges, industrial efficiency in ethanol production is invariably lower than the theoretical yield of 51% (w/w), meaning 1 g of glucose can yield a maximum of 0.51 g of ethanol due to process losses and limitations [99]. The standard industrial host, S. cerevisiae, is highly tolerant of ethanol but unable to metabolize xylose (C5), the second most abundant sugar in lignocellulose. Other microorganisms, such as Z. mobilis, also fail to metabolize C5 sugars and exhibit sensitivity to bioprocess stresses [9]. These values fluctuate depending on the feedstock, technology, generation, and operational conditions. Furthermore, conventional microbial fermentation is limited by the inefficiency of wild-type microorganisms.

To provide a more holistic overview of the current bioenergy landscape, this study expands the comparative analysis beyond traditional 1G and 2G technologies by incorporating third-generation (3G) and 4G biofuels. While 3G biofuels utilize algal biomass to overcome land use competition, 4G technologies represent the frontier of the field, employing genetically engineered microorganisms and carbon capture strategies to directly convert CO2 into drop-in fuels. This comprehensive classification, summarized in Table 2, evaluates each generation not only by their feedstock and metabolic pathways but also through standardized metrics of industrial yield (g/g) and final product titer (g/L), highlighting the technical bottlenecks that remain for the large-scale deployment of advanced generations.

Table 2.

Comparison of 1G to 4G ethanol industrial yields versus theoretical.

To overcome these limitations in yield and purity, PF and metabolic engineering are essential. Current strategies focus on cultivating strains that can (1) simultaneously con-vert C5 and C6 sugars [110]; (2) increase tolerance to inhibitors and to ethanol [111]; and (3) improve carbon flux toward the target product via genetic modifications, including gene insertion, deletion, or regulation [112]. The main strategies are provided in detail in Table 1, listed in Section 2.1.

In this context, the yeast S. cerevisiae is the principal industrial chassis for 2nd generation (2G) ethanol production. However, it lacks the native capability to consume pentoses from lignocellulosic hydrolysates, necessitating genetic/metabolic modifications. Optimization initiates with the co-fermentation of hexoses and pentoses, enabled by the insertion of heterologous pathways (such as genes from Pichia stipitis). Subsequent modifications include the modulation of stress response gene expression (e.g., TPS1) to increase tolerance to multiple inhibitors, enhancement of thermotolerance, and process intensification strategies like cell recycling and in situ ethanol removal [113,114].

More advanced strategies involve systems-level approaches, such as combinatorial promoter optimization to modulate key genes in the fermentative pathway (e.g., PDC1, ADH1). In addition to engineered S. cerevisiae, non-conventional yeasts are also utilized as alternative platforms. These include Scheffersomyces stipitis and Spathaspora passalidarum (which are naturally pentose-fermenting) and K. marxianus and Ogataea polymorpha (which are thermo-tolerant) [91,113,114].

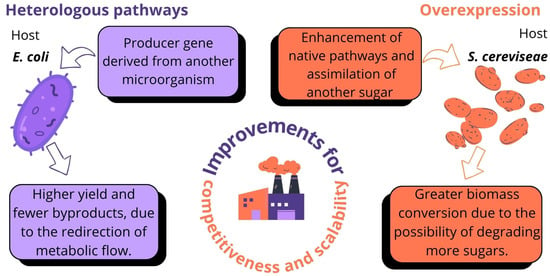

The term “advanced alcohols” (2G, 3G, and 4G) refers to alcohols produced via technological routes, from feedstocks, and possessing chemical properties that differ from, and are more sustainable than, conventional (1G) ethanol. PF is equally crucial for the biosynthesis of advanced alcohols (isobutanol, propanol, pentanol, and octanol), representing a high-performance alternative to ethanol due to its lower corrosiveness, higher calorific value, and lower hygroscopicity [115,116]. Although isobutanol production is predominantly fossil-based, metabolic engineering in hosts such as S. cerevisiae and E. coli has been applied to optimize synthesis (Figure 3) by introducing heterologous pathways (bacteria) or enhancing native pathways and coupling with xylose assimilation (yeasts) [117,118].

Figure 3.

Metabolic engineering for the production of advanced alcohols.

The integration of PF is, therefore, the way to optimize the conversion of lignocellulosic substrates into advanced bioalcohols, enabling competitiveness and industrial scaling. A comparison between unmodified (wild-type) and GM microorganisms reveals that GM strains exhibit 10- to 100-fold higher yields, reduced fermentation times, and enhanced conversion efficiency of lignocellulosic sugars in the production of advanced alcohols, as listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Yields of wild-type and genetically modified microorganisms in the production of ethanol, isobutanol, and n-butanol.

3.2. Drop-In Hydrocarbons and Lipid-Based Biofuels

Despite the advances in studies involving the production of biofuels, most are not fully compatible with current fossil fuel-based engines and supply systems, requiring blends with nonrenewable fuel sources, such as gasoline, or even adaptations in the engines [119,120]. Given this issue, various studies aim to produce fuels with properties similar to those currently used, such as gasoline, diesel, and aviation kerosene [121,122,123].

These fuels, known as “drop-in” hydrocarbons, are derived from renewable sources like plant biomass and possess identical physical and chemical properties to petroleum derivatives, enabling them to directly substitute conventional fuels without necessitating modifications to engines or refueling infrastructure. The biomass utilized for fuel production can be transformed via thermochemical methods (gasification, pyrolysis, hydrothermal liquefaction) or biochemical processes, wherein microorganisms ferment sugars and lipids to generate compounds that replace fossil fuels [124]. Among these microorganisms, those that produce enzymes like acyl-ACP reductase (AAR) and aldehyde-deformylating oxygenase (ADO) are notable for their ability to transform fatty acids into alkanes and alkenes [125,126].

The metabolic pathways for generating drop-in fuels differ based on the microorganism utilized and encompass: (1) the genetic modification of yeasts such as Y. lipolytica to transform biomass-derived sugars into liquid alkanes and alkenes [71,72]; (2) the cultivation of oleaginous algae abundant in lipids (triacylglycerols—TAGs and fatty acids), which can be converted into biodiesel or bio-oil via transesterification and hydrothermal liquefaction [127,128,129,130,131]; and (3) the engineering of lignocellulolytic bacteria for the synthesis of short- and long-chain hydrocarbons [132,133].

In this context, the yeast Y. lipolytica is notable for its metabolic versatility and capacity for lipid fuel synthesis [134]. Cyanobacteria are also promising for producing alkanes and alkenes naturally via the AAR/ADO pathway, with genetic engineering aimed at optimizing these pathways [125]. Oilseed algae represent a group with significant potential for “drop-in” biofuel production, as they accumulate neutral lipids and hydrocarbons capable of substituting biodiesel, aviation kerosene, and green diesel [135,136].

Metabolic customization plays a central role in this process, enabling the adjustment of chain length, branching degree, and saturation level of carbon chains, which define the physicochemical properties of the resulting fuels. For instance, short-chain and branched biofuels (C4–C8), known for their enhanced combustion efficiency, are derived from α-ketoacids via the Ehrlich pathway [137,138,139]. The modification of genes linked to this pathway has been a major focus for increasing production yields [137,138,140]. Metabolic engineering approaches in S. cerevisiae have been utilized to augment the production of branched alcohols (e.g., isobutanol) via the Ehrlich pathway and subsequently transform them into short-chain branched esters by overexpression of alcohol acyltransferases [141,142]. The Ehrlich pathway has been engineered in hosts such as E. coli, B. subtilis, C. glutamicum, Brevibacterium flavum, Ralstonia eutropha, and Synechococcus elongatus 7942 [143,144].

Several specific pathways are targets for this engineering. Engineering of the Ehrlich pathway for advanced alcohols focuses on three enzymatic steps and their corresponding genes. First, Transaminases (such as BAT1 and BAT2) initiate the process by converting amino acids into α-keto acids. Subsequently, α-Keto Acid Decarboxylases (KDCs), such as ARO10 or the heterologous kivd gene, remove carbon dioxide (CO2) to form an aldehyde. Finally, Alcohol Dehydrogenases (ADHs) reduce this aldehyde to the desired alcohol, with the overexpression of precursor pathway genes (such as ILV) also being a common strategy to maximize metabolic flux [145,146].

Conversely, long-chain and branched hydrocarbons (C15–C20) exhibit improved fluidity and lower freezing points, making them ideal for aviation applications [143,147]. These molecules are produced by Gram-positive bacteria such as B. subtilis, using α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BKD) and the FASII system to elongate α-ketoacids. Genes from this pathway, including the bkd operon and fabH2, are inserted to synthesize long-chain branched fatty acids [143,148,149].

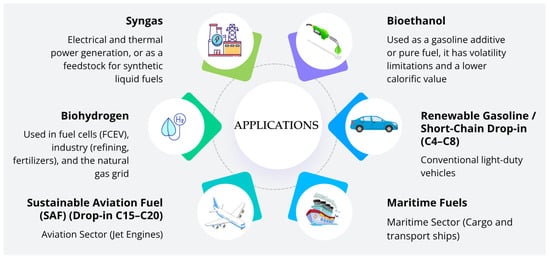

Another determining factor is the saturation level of the molecules, which affects fluidity, thermal stability, and freezing point [150]. Unsaturation lowers the melting point, which is good for aviation biofuels [151]. On the other hand, higher saturation levels improve thermal and oxidative stability, which is good for marine and automotive fuels [152]. The engineering of pathways that control the activity of desaturases and reductases makes it possible to change these properties. The overexpression of desaturases (Ole1 or Fad2) in microorganisms such as S. cerevisiae and Y. lipolytica aims to increase the production of unsaturated fatty acids, whereas deletion of these enzymes redirects metabolism toward more saturated and stable compounds [153,154,155,156,157,158]. Thus, advances in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology have enabled the improvement of microorganisms capable of synthesizing drop-in hydrocarbons with tunable properties, accelerating the commercial feasibility of lipid-based biofuels derived from renewable sources. However, despite these advances, a substantial gap still exists between the production of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and the global demand for aviation fuel. Current SAF supply accounts for only about 3% of total renewable fuel consumption, reflecting both limited production capacity and constraints associated with the availability of biomass on a large scale [159]. Some uses and types of advanced biofuels produced in PF are listed in Figure 4 and metabolic engineering strategies employed are listed in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Uses and types of advanced biofuels produced in PF.

For other products, the Fatty Acid Synthesis (lipogenesis) pathway employed by GM Yarrowia lipolytica involves the conversion of biomass-derived sugars into acetyl-CoA, subsequently into fatty acids/lipids, and finally into liquid alkanes/alkenes, utilizing metabolic engineering to optimize each stage of the process. In this process, the AAR/ADO pathway functions as a shunt branching from primary fatty acid (lipid) synthesis. The route initiates when the first enzyme, AAR, utilizes an Acyl-ACP molecule (an activated fatty acid) and converts it into a fatty aldehyde. Concurrently, the second enzyme, ADO, acts upon this aldehyde, removing the carbon from the aldehyde group (deformylation) to generate a terminal alkane. The production of alkenes (containing double bonds) follows the exact same pathway, occurring simply when the initial Acyl-ACP substrate is already unsaturated [160,161].

Table 4.

Metabolic engineering approaches microorganisms to produce “drop-in” and lipid based.

Table 4.

Metabolic engineering approaches microorganisms to produce “drop-in” and lipid based.

| Species | Target Product | WT Yield | GM Yield | WT vs. GM Improvement | Conditions | Genetic Strategy (GM) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Isobutanol | ∼0 g/L | 22 g/L | N/A (WT = 0) | Glucose (10%), fed-batch, 30 °C, 48 h | Insertion of isobutanol pathway: overexpression of alsS (BS), ilvC/D (Ec), kivd (Lc), adhA (Ec) | [162] |

| S. cerevisiae | Isobutanol | ∼0.008 g/L | 1.6 g/L | ∼200-fold increase | Glucose (20 g/L), batch, 30 °C, 72 h | Overexpression of ILV2, ILV5, ILV3 (valine pathway), ARO10 (KDC), and ADH2 (ADH) | [163] |

| E. coli | n-Butanol | ∼0 g/L | 15 g/L (∼0.19 g/g glucose) | N/A (WT = 0) | Glucose (80 g/L), fed-batch, 37 °C, anaerobic, 72 h | Modified Clostridial pathway (CoA-dependent): optimized thl, hbd, crt, bcd, etfAB, adhE2 | [164] |

| S. elongatus PCC 7942 | Isobutanol (secreted) | ∼0 g/L | 0.45 g/L | N/A (WT = 0) | Phototrophic culture (CO2), 30 °C, 6 days | Insertion of isobutanol pathway (as in E. coli): alsS (BS), ilvC/D (Ec), kivd (Lc), adhA (Ec) | [165] |

| E. coli | Alkanes (C13–C17) | ∼0 g/L | 0.58 g/L | N/A (WT = 0) | Glucose (20 g/L) + Oleic Acid (0.1%), 30 °C, 48 h | Insertion of Acyl-ACP Reductase (AAR) and Aldehyde-Deformylating Oxygenase (ADO) from cyanobacteria | [166] |

| Y. lipolytica | Lipids (TAGs) | ∼5 g/L | ∼15 g/L | ∼3-fold increase | Glucose (150 g/L), fed-batch, high C/N ratio, 96 h | Overexpression of DGA1 and DGA2 (TAG synthesis) and ACC1 (malonyl-CoA synthesis) | [167] |

| Y. lipolytica | Lipids (TAGs) | ∼7.5 g/L | ∼35 g/L | ∼4.6-fold increase | Glucose, fed-batch, high C/N ratio, 120 h | Deletion of all 6 POX genes (β-oxidation) + overexpression of DGA1 and DGA2 | [168] |

| Rhodosporidium toruloides | Lipids (TAGs) | ∼0.41 × X g/L | ∼0.65 × X g/L | ∼1.6-fold increase | Glucose (70 g/L), C/N = 100, 144 h | Overexpression of ACC1 (Acetyl-CoA carboxylase) using CRISPR-Cas9 | [169] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Farnesene | ∼0 g/L | ∼25 g/L | N/A (WT = 0) | Sugarcane molasses, fed-batch, 30 °C, ∼120 h | Overexpression of the Mevalonate (MVA) pathway (e.g., tHMG1), deletion of ERG9, insertion of Farnesene Synthase | [170] |

| Escherichia coli | Free Fatty Acids (FFAs) | ∼0 g/L (secreted) | ∼4.5 g/L | N/A (WT = 0) | Glucose (20 g/L), batch, 37 °C, 24 h | Deletion of fadD (prevents re-import/degradation) + overexpression of Thioesterase (TesA) | [14] |

Overview of microbial engineering strategies for the generation of hydrocarbon-like biofuels, including diesel, biojet fuel, and gasoline analogs. The table compiles microorganisms, target compounds, and performance outcomes reported in the literature. N/A = Not applicable, WT = Wild type, GM = Genetically modified. Gene names are italicized to distinguish them from protein names.

3.3. Syngas Fermentation

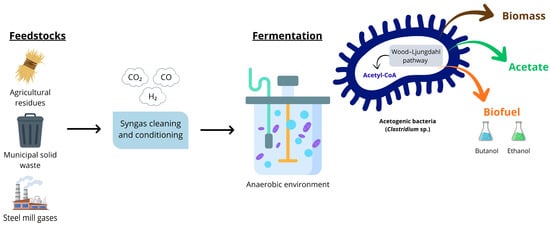

An emerging technological route for the sustainable synthesis of energy intermediates is synthesis gas (syngas) fermentation. In this process, anaerobic bacteria (particularly those of the Clostridium genus) are employed to convert industrial waste gases, such as CO2, carbon monoxide (CO), using hydrogen (H2) as a critical electron donor, into industrial products, including butanol, ethanol, and hexanol. The central biological mechanism in acetogenic bacteria is the WLP, also known as the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway, which enables acetogens to convert carbon from gaseous substrates into the metabolic intermediate acetyl-CoA. This intermediate is subsequently converted into biomass and acetate, which is further reduced to generate the desired alcohols (Figure 5) [15,16,171].

Figure 5.

Biological Conversion of Syngas into acetate, biomass, and biofuels via the Wood–Ljungdahl Pathway.

However, process efficiency and stability are variable and influenced by factors such as microbial strain, nutrient medium, and gas composition. A critical factor is oxygen (O2), which acts as a strong inhibitor and can completely suppress alcohol production at elevated concentrations [172]. A practical study demonstrated the conversion potential of biogenic syngas (gas generated by gasification) using the acetogenic bacteria Clostridium carboxidivorans and Clostridium autoethanogenum. Initially, O2 represents a critical component with a suppressive effect: untreated bi-ogenic syngas, containing 2459 ppm of O2, resulted in the complete inhibition of C. carboxidivorans’s metabolism, preventing growth, gas uptake, and alcohol production. The pre-treatment with a Pd catalyst and the subsequent reduction in the O2 content to 293 ppm was the decisive factor, resulting in an efficiency comparable to the reference artificial syngas, with biomass, acetate, and ethanol concentrations in the same order of magnitude and a carbon balance of 89.7–93.2%, similar to the 93.9% of the con-trol. The use of biogenic syngas (with reduced O2) in C. autoethanogenum resulted in gains in efficiency and selectivity relative to the reference gas. Process optimization was demonstrated by a 31% increase in the final ethanol concentration (from 2.74 g/L to 3.60 g/L) and a significant 104% increase in the final 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BDO) concentration (from 0.52 g/L to 1.06 g/L) [172].

Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology can overcome limitations in productivity and selectivity. Given the limited energy availability in chassis like C. autoethanogenum, computational (in silico) modeling aids in enhancing selectivity by identifying bottlenecks in branching pathways that produce undesirable by-products [173]. A recent study employed in silico stoichiometric and kinetic modeling for a systematic analysis of C. autoethanogenum metabolic network, identifying the most effective single, double, and triple interventions for the overproduction of 2,3-BDO with minimal carbon loss. Quantitative analysis revealed that the overexpression of the pyruvate–ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) enzyme constituted the most effective single intervention on the 2,3-BDO production rate, leading to a 2.6-fold increase (reaching 0.10 ± 0.023 compared to 0.039 ± 0.0091 of the WT). The most promising double intervention was the combined overexpression of PFOR and Acetolactate Synthase (ACLS), which elevated production to 0.14 ± 0.030, representing a 3.59-fold increase relative to the WT and a 1.4-fold gain over the single PFOR intervention. Furthermore, the triple intervention involving the overexpression of PFOR, ACLS, and Acetolactate Decarboxylase (ACLDC) achieved a flux value of 0.15 ± 0.056, corresponding to a fourfold increase compared to the WT and a 7% enhancement relative to the combined positive intervention of PFOR and ACLS [174].

Validated genetic approaches encompass the inactivation of the adhE gene in C. autoethanogenum, yielding a 180% enhancement in ethanol production, and a reduction of up to 38% in the acetate byproduct, alongside the creation of CO-responsive transcriptional modules in Eubacterium limosum, which, when integrated with CRISPR–Cas9, redirect carbon flux towards target products such as 2,3-BDO [24,175].

3.4. Biohydrogen as a Strategic Energy Vector

Hydrogen is recognized as a fundamental energy vector due to its clean combustion (which results solely in water vapor) and its high mass energy density. It exhibits a higher heating value (HHV) in the range of 120–142 MJ/kg, which is approximately three times the energy content of gasoline (whose fractions range between 41.1 and 44.6 MJ/kg) [176,177,178]. Hydrogen is considered an essential energy vector for a future carbon-neutral system. Although low-carbon alternatives exist, such as blue hydrogen (with Carbon Capture and Storage—CCS) and green hydrogen (produced via electrolysis), global production is overwhelmingly dominated by fossil routes. Currently, over 95% of the world’s hydrogen originates from non-renewable sources (primarily steam methane reforming—SMR), with green hydrogen (derived from 100% renewable electricity) restricted to only 1% of the total output [176,179,180].

In this context, biohydrogen production emerges as a decentralized and resilient alternative. Biohydrogen is a high-performance, non-polluting energy carrier that relies on biological systems or thermochemical treatments to convert organic waste or biomass. This route is particularly attractive because it employs low-cost renewable feedstocks, offering a more flexible mechanism to overcome the cost and infrastructure barriers faced by other low-emission hydrogen pathways [17].

3.4.1. Biological Pathways and Yield Engineering

Biohydrogen production predominantly transpires via dark fermentation (DF) and photosynthetic processes (photofermentation and biophotolysis), with yield engineering as the principal approach to enhance its purity and productivity. During DF, microorganisms function in anaerobic environments to transform organic substrates into alcohols, organic acids (such as acetic and butyric acids), and gases, including H2. This light-independent process is predominantly executed by bacteria from the Clostridium and Enterobacter genera. The efficiency is contingent upon hydrogenase activity and the corresponding electron transfer mechanisms [100,181].

The formate–hydrogen lyase pathway, characteristic of Enterobacter, converts pyruvate into formic acid, which is subsequently cleaved to release H2 and CO2. In contrast, in the ferredoxin pathway (Clostridium), the PFOR enzyme oxidizes pyruvate. The maximum theoretical yield (4 mol H2 per mol of glucose) is achieved when the fate of acetyl-CoA is directed toward acetate formation, but it is reduced by half when acetyl-CoA is diverted to butyrate production [100,181]. For Enterobacter, several studies have directly compared wild-type and genetically engineered strains. For example, the overexpression of the fhlA gene in Enterobacter cloacae WL1318 increased cumulative hydrogen production by 188% and improved the H2/S ratio by 37% compared with the wild-type strain [182].

In contrast, photofermentation and biophotolysis constitute phototrophic hydrogen-producing pathways, functioning as complementary routes to DF in integrated biohydrogen systems. In photofermentation, photosynthetic bacteria such as Rhodobacter use light to oxidize organic acids, often generated during DF, and convert them into hydrogen through the combined activity of hydrogenases and nitrogenases [183,184,185,186]. The overall reaction can be represented as (Equation (1)):

Recent studies have demonstrated the applicability of this route using real effluents; for example, Rhodobacter capsulatus B10 produced up to 126.5 mL H2/g of VFA from effluents derived from orange peel, with the highest yields obtained at a 25% effluent concentration and reduced performance at higher concentrations due to increased opacity of the medium and inhibition of the substrate [187]. The efficiency of this process depends on key parameters such as light intensity, optimization of the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, and the incorporation of metal cofactors [183,184,185,186].

Building on this phototrophic framework, biophotolysis represents another light-driven route for hydrogen formation but relies directly on water photolysis rather than organic acid oxidation. In biophotolysis, solar energy captured by photosystem II promotes the cleavage of water molecules, releasing oxygen, electrons, and protons. The reduced electrons generated in this process are subsequently directed toward hydrogen production via proton reduction, catalyzed by hydrogenase or nitrogenase enzymes. This pathway can occur as either direct or indirect biophotolysis [188].

In direct biophotolysis, solar energy captured by photosystem II drives water splitting, releasing electrons that are transferred to photosystem I, where they reduce protons through the action of hydrogenases. This results in hydrogen formation without greenhouse gas emissions, while oxygen is simultaneously released into the atmosphere [188]. The overall reaction is shown in Equation (2):

In indirect biophotolysis, electrons generated during photosynthesis are first used to fix CO2 and synthesize carbohydrates (Equations (3) and (4)), which are subsequently degraded, in the absence of light, to produce hydrogen [186]:

While phototrophic routes rely on light as the primary energy source, DF constitutes a fully anaerobic and light-independent biological process, representing a complementary strategy for hydrogen production. DF converts organic residues into hydrogen and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and is considered a truncated form of anaerobic digestion involving three main microbial stages. In the first stage, hydrolysis, hydrolytic bacteria degrade complex biopolymers into sugars, amino acids, and lipids. In the subsequent acidogenesis step, these molecules are fermented by acidogenic bacteria, producing VFAs such as acetic, propionic, butyric, lactic, and valeric acids, in addition to alcohols and carbonic acid. Hydrogen yield depends on the dominant acidogenic pathway: the acetate pathway produces 4 mol H2 per mol glucose (Equation (5)), while the butyrate pathway yields only 2 mol H2 per mol glucose (Equation (6)) [189]. Thus, the microbial composition and predominant metabolic route determine the overall efficiency of hydrogen production.

Linking DF to practical applications, the DF of food waste is particularly efficient due to its high carbohydrate content. In batch tests, various combinations of Clostridium butyricum, Clostridium beijerinckii, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Lactobacillus pentosus were evaluated, with the most effective formulation producing 46.0 ± 0.7 mL H2 g VS−1. When employed in a bioaugmentation strategy with sterile and non-sterile food waste, this combination achieved 89.6 ± 1.0 mL H2 g VS−1 and 76.7 ± 2.6 mL H2 g VS−1, respectively. The resulting microbial community was dominated by C. butyricum sensu stricto I, while Enterobacter contributed to lower yields in non-sterile conditions [190].

To overcome the yield and purity limitations of natural pathways, biohydrogen pro-duction can be enhanced through PF and metabolic engineering. In DF, genetic engineering can employ tools such as CRISPR-Cas to modify electron flow, redirecting reduced ferredoxin specifically to H2 production, minimizing the formation of competing byproducts. This result can be achieved by overexpressing hydrogenases and cofactor recycling enzymes, such as ferredoxin-NADH oxidoreductases and PFOR, while simultaneously suppressing competing metabolic pathways. These modifications can lead to significant improvements, enabling a 100% yield increase compared to wild-type strains, approaching or exceeding the theoretical maximum of 4 mol of H2 per mol of glucose used [100,191,192].

In biophotolysis, genetic engineering operates at two levels: structural and enzymatic. Structurally, it is possible to modify microalgae, such as C. reinhardtii, by reducing the size of their light-harvesting antennae and diminishing the chlorophyll content per unit cell volume. This leads to increased light penetration and transmittance, thereby enhancing photosynthetic performance, which is critical for boosting biomass and lipid production [193]. Structural light optimization is a crucial factor for gains in H2 productivity in high-density cultivation systems. In assays under saturating light intensity (285 μE m−2 s−1), the truncated antenna mutant (tla1) achieved a maximum specific H2 photoproduction rate of approximately 3.0 μmol mg−1Chlh−1, exceeding the parental strain (approximately 0.75 μmol mg−1Chlh−1) by fourfold. Furthermore, this modification conferred upon the mutant an efficiency of light energy conversion to H2 up to 8.5 times higher than the wild-type under saturating light [194].

Enzymatically, protein engineering overcomes enzyme sensitivity to O2 by creating transgenic mutant enzymes, for instance, with single and double mutations, in which the enzyme gas access channel is narrowed. This design allows for the preferential H2 egress while simultaneously restricting O2 ingress. In in vitro assays with 5% O2, the mutant produced up to 22 µL mL−1 of H2, a productivity approximately 7 times greater than the wild-type (3 µL mL−1). In long-term in vivo trials, the H2 concentration in the mutant reached 70 µL mL−1, a value approximately 30 times superior to the wild-type [195].

3.4.2. Barriers, Scalability, and Hybrid Biorefineries

Biohydrogen production encounters substantial obstacles that hinder its commercial feasibility, notably the low efficiency and yield of biological processes on an industrial scale. Various intrinsic and environmental factors serve as constraints, including the organism utilized, substrate type and concentration, pH, light availability, temperature, by-product inhibition, and oxygen sensitivity [196,197,198].

Moreover, biohydrogen is produced as a mixture with other gases, requiring rigorous purification techniques (such as pressure swing adsorption or selective membranes) to achieve the 99.9% purity necessary for fuel cell applications [199]. Storage and transportation present another major logistical and economic challenge due to its low energy density, necessitating costly and complex compression or liquefaction processes, as well as specialized infrastructure and safety considerations [200]. Bioreactor design, including systems such as the dynamic membrane bioreactor (DMBR), is also critical for achieving scalability [201].

To overcome the economic infeasibility of standalone production, the concept of hybrid biorefinery has gained prominence. This model focuses on the coproduction of multiple products, such as in co-fermentation systems using C. acetobutylicum and Enterobacter aerogenes to generate H2, ethanol, butanol, and acetone, while solid residues are digested to produce biomethane [202]. Other ways to coproduce include making organic acids and biopolymers from DF effluents and using genetic innovation to improve the coproduction of H2 and ethanol [196,203].

One particularly efficient reactor strategy is coupling DF with microbial electrolysis cells (MECs), which are bioelectrochemical systems in which electroactive microorganisms provide oxidized volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and other carboxylates at the anode, converting them to H2 at the cathode [204,205,206]. In this way, byproducts such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate, which limit the H2 yield in DF, are converted into gas and increase energy production from the substrate [207,208]. In integrated DF-MEC systems, the H2 yield can be increased by 40–300% compared to isolated DF, depending on the type of substrate and process [205,207,209]. DF provides the MECs with an effluent with good conductivity and a VFA profile that improves charge transfer, mitigating one of the main kinetic limitations of MECs [204,206,210]. This integration recovers substrate value, reduces costs, and demonstrates that the systems of co-production processes are more sustainable than stand-alone processes [195,198]. Despite promising performance, challenges such as cost, energy expenditure, and methanogenesis still limit large-scale application, requiring process optimization, pretreatments, and methanogenesis reduction strategies [204,206,210].

4. Advantages of Precision Fermentation for Biofuels

4.1. High Product Selectivity

High product selectivity in PF for biofuels is a central advantage, resulting from the synergy between genetic engineering and stringent bioprocess control [112,211,212]. Practical examples highlight this precision: deletion of the ldh gene in E. aerogenes increased production of the precursor 2,3-BDO by 71.2% [213]; metabolic manipulations in S. cerevisiae for alcohol coproduction raised the purity of 3-methyl-1-butanol from 42% to 71% [214]; and a coordinated strategy in S. cerevisiae (combining deletion of competing genes and cofactor optimization) enabled the selective production of FAMEs (Fatty Acid Methyl Esters) [154].

For genetic potential to be expressed at an industrial scale, advanced metabolic control is essential. Bioprocess strategies such as electrofermentation (EF) overcome conventional limitations by using electrodes to regulate the redox balance, increasing yields and minimizing by-product formation [215,216]. Similarly, optimizations such as enhanced Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (eSSF), employing cellulosic emulsions, enable rapid and efficient hydrolysis of complex substrates (e.g., isobutanol production within one day at 30 °C) [217]. Optimization of operational conditions (O2 availability, pH, and temperature) is a fundamental metabolic strategy capable of boosting yields (e.g., from 65% to 85% for 2,3-BDO) and achieving high selectivity by eliminating by-products and ensuring large-scale feasibility [218].

4.2. Substrate Flexibility

The flexibility of the substrate is a significant key advantage of PF, facilitating the exploration of sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels and promoting the advancement of a circular economy. PF facilitates the utilization of diverse low-cost, non-food carbon sources, overcoming resource competition and enhancing the value of the substantial quantities of residual lignocellulosic biomass produced by global agriculture, thereby preventing additional waste generation and reducing environmental impact [219,220].

Overcoming biomass recalcitrance can be achieved through optimized pretreatment. For example, pretreating reed straw residues with L-glutamic acid increased the yield of fermentable sugars by more than fivefold [221]. Additional strategies such as hydrolysis, hybrid fermentation, microbial co-interactions, and cocultures can also be employed to enhance process efficiency and convert residues into multiple biofuels, including bioethanol, biobutanol, and biomethane [221,222]. Advanced strategies such as PF are likewise used to expand the capacity to process diverse wastes, maximizing production and improving overall performance [216]. Furthermore, PF broadens substrate utilization to include gaseous sources such as syngas [223].

4.3. Modular Scalability and Synergistic Integration in Biorefineries

The strategy of decoupling from the traditional model of industrial scalability makes PF economically advantageous. Its perspective contrasts with the reliance on single, slowly constructed, and high-cost facilities.

4.3.1. The ‘Scale-Out’ vs. ‘Scale-Up’ Model

PF employs a scale-out strategy, utilizing multiple standardized, modular fermentation units, rather than the conventional scale-up method that focuses on enlarging a single large reactor. This transition offers economic benefits via consistent and foreseeable growth; it enables enterprises to initiate with smaller units and augment capacity in response to rising demand; and it enhances deployment efficiency, as prefabricated or standardized modules can be swiftly installed [29,224].

4.3.2. Synergistic Integration in Biorefineries

The modular nature of PF allows a unit to function as a plug-and-play module that can be retrofitted into an existing facility, for example, a pulp mill, a first-generation ethanol plant, or a biodiesel facility.

This integration enables three levels of synergy:

- I.

- Feedstock Synergy: The PF module can be designed to consume by-products or waste streams from the host facility. For example, it can use biogenic CO2 released from 1G ethanol fermentation, crude glycerol from a biodiesel plant, or hydrolysate from a pulp mill, transforming low-value residues into feedstocks for advanced biofuel production [225,226,227].

- II.

- Utility and Infrastructure Synergy: A new PF unit can share existing infrastructure, such as steam and electricity generation, inbound and outbound logistics, and wastewater treatment systems. This reduces costs associated with Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) and Operational Expenditure (OPEX) for new processes [226,227].

- III.

- Portfolio Synergy: The integration of new modules enables diversification of the product portfolio with higher value-added compounds. In this way, an ethanol-producing facility can begin producing SAF, thereby gaining access to additional markets [228,229,230].

4.4. Potential for Low-Carbon and Carbon-Negative Processes

PF for biofuels is strategically positioned within the broader context of Negative Emission Technologies (NETs), which are essential for atmospheric CO2 removal and global warming mitigation [166]. NETs encompass a portfolio of biological and engineering approaches, including Direct Air Capture (DAC), BECCS (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage), and biochar (carbon sequestration via pyrolyzed biomass), with mitigation potentials ranging from 0.013 MtCO2/year (current DAC systems) to 1.8 GtCO2/year (biochar) [231,232]. To put these figures into perspective, global energy-related CO2 emissions reached a record 37.4 Gt in 2023 [159]. Thus, while DAC technologies are still in an incipient stage of development, the projected capacity of biochar to mitigate approximately 4.8% of annual global emissions underscores that a diversified portfolio of NETs is vital for climate stabilization.

The industrial viability of these processes, such as DAC depends on the optimization of key performance indicators (KPIs), including carbon removal efficiency (CRE) and carbon removal rate (CRR) [233]. PF functions as a complementary technology focused on optimizing biological CO2-conversion routes. Processes such as gas fermentation, EF, and waste valorization enable carbon capture and conversion. Pressurized Electrofermentation (PEF) has demonstrated the ability to overcome mass-transfer limitations, optimizing CO2 conversion into value-added products, and its carbon-negative potential has been validated through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [234].