Abstract

The context of food science and biotechnology is undergoing a profound transformation, characterized by an evolutionary shift from conventional large-scale fermentation to precision biomanufacturing, positioning Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) as versatile cellular biofactories for next-generation functional foods. This review analyzes the evolutionary role of LAB, their utilization as probiotics, and the technological advances driving this shift. This work also recognizes the fundamental contributions of pioneering women in the field of biotechnology. The primary methodology relies on the seamless integration of synthetic biology (CRISPR-Cas editing), Multi-Omics analysis, and advanced Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning, enabling the precise, rational design of LAB strains. This approach has yielded significant findings, including successful metabolic flux engineering to optimize the biosynthesis of high-value nutraceuticals such as Nicotinamide Mononucleotide and N-acetylglucosamine, and the development of Live Biotherapeutic Products using native CRISPR systems for the expression of human therapeutic peptides (e.g., Glucagon-like Peptide-1 for diabetes). From an industrial perspective, this convergence enhances strain robustness and supports the digitalized circular bioeconomy through the valorization of agri-food by-products. In conclusion, LAB continue to consolidate their position as central agents for the development of next-generation functional foods.

1. Introduction

Food is an integral part of our civilization. It is a cultural phenomenon that, while it has evolved, is associated with traditions and social identities [1]. One example of food that has accompanied the evolutionary history of humanity is fermented food. It is believed that fermented foods were crucial for the survival of our ancestors; however, they have recently gained renewed interest due to scientific contributions regarding their beneficial effects on human health and the underlying molecular and microbiological mechanisms.

Currently, the context of food science and biotechnology is undergoing a profound and accelerating transformation, characterized by an evolutionary shift from conventional large-scale fermentation to precision biomanufacturing. Bridging the gap between ancestral practices and contemporary advances are the Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB), a key microbial group whose historical role as simple starter cultures is rapidly expanding to that of versatile and robust cellular biofactories.

LAB comprise a group of Gram-positive, non–spore-forming, aerotolerant bacteria phylogenetically classified within the phylum Firmicutes, primarily in the order Lactobacillales. LAB include the reclassified members of the Lactobacillus (L.)/Lactobacillaceae genus complex as well as several additional genera, such as Lactococcus (Lc.) and Tetragenococcus [2]. They are among the most influential and extensively utilized microorganisms in food fermentation, contributing fundamentally to the production of fermented dairy, meat, cereal, and vegetable products [3].

LAB are strategically positioned to become the cornerstone for developing next-generation functional foods tailored to modern health and sustainability demands. The technological leap enabling this future is defined by a rigorous confluence of frontier disciplines. The convergence of biotechnology and data science fundamentally redefines the boundary between food and medicine. Specifically, this is realized through the seamless integration of synthetic biology, high-throughput Multi-Omics analysis (genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics), and advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI)/Machine Learning (ML) algorithms. Tools such as CRISPR-Cas allow for the precise, rational design and genomic modification of LAB strains, optimizing metabolic pathways for the overproduction of specific bioactive compounds. Concurrently, AI-assisted design systems advantage omics data to predict complex phenotypes, such as flavor profiles and viability, thereby facilitating smart, self-regulating fermentations and minimizing batch variability [4]. From an industrial perspective, this precision-driven approach supports the sustainable production of high-value functional ingredients with a reduced carbon footprint. In this context, the digitalized circular bioeconomy represents an integrated framework in which advanced digital technologies are combined with biological systems to optimize the use of renewable resources, close material and energy loops, and valorize agri-food by-products, ultimately enhancing process efficiency, sustainability, and environmental performance. Finally, this technological framework provides the structure for personalized nutrition strategies, translating individual microbiome data into meticulously tailored food matrices engineered for optimal human and environmental health [5].

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of LAB, ranging from their historical role in food fermentation to their modern use as probiotics characterized via multi-omics. We discuss the advances and hurdles in LAB-based precision biomanufacturing, highlighting its potential in creating next-generation functional foods. Finally, the study addresses the valorization of agri-food by-products as a sustainable pathway for functional food production (Figure 1). This work also recognizes the fundamental and sustained contributions of pioneering women in the field of genetics and molecular biology whose discoveries have been fundamental to the advancement of LAB biotechnology.

Figure 1.

Precision biomanufacturing with LAB.

2. From Ancestral Fermentations to Contemporary Advances: The Evolving Role of LAB in Functional Foods

2.1. Fermentation in the History of Humanity

Fermented foods and beverages have recently been defined by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) as “foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components” [6]. Even though fermented foods have gained increasing popularity in the last 20 years, they were a staple of the human diet for thousands of years. Fermentation has accompanied the evolutionary history of humankind and is believed to have been crucial for the survival of our ancestors on the African grasslands, where the first key anatomical features of our species emerged [7,8]. Also, around 14,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Revolution, fermented foods and beverages accompanied the transition from hunter-gatherer communities to settled farming communities [6]. Thus, microorganisms have had a significant, though sometimes underestimated, impact on human culture and history. However, the changes in social, demographic, and nutritional habits, including the consumption of more ultra-processed foods high in saturated fats, simple sugars, and chemical additives and low in fiber and with few live microorganisms, have gradually led to a depletion in the richness and diversity of our symbiotic microorganisms [9].

Fermentation is a highly effective food preservation technique, as microbial metabolism produces high local concentrations of antimicrobial compounds such as ethanol and lactic acid, which inhibit the growth of spoilage or potentially pathogenic microorganisms. Consequently, food with microbiological stability, safety, and a longer shelf life is obtained. Secondly, fermentation improves the nutritional value and digestibility of food raw materials, increasing the content of free amino acids, synthesizing de novo vitamins, and breaking down substrates such as soluble fiber so that they can be assimilated by the host. Also, fermentation provides unique organoleptic properties, such as enhanced flavor, aroma, and texture [7,10].

Worldwide, these beneficial properties have led to the development of various fermented products made primarily from milk, but also from vegetables, fruits, grains, soybeans, other legumes, meat, and fish, among others [6].

2.2. LAB as Versatile Starter Cultures for Fermented Foods

Understanding the nutritional and health relevance of fermented foods requires recognition of the extensive microbial diversity involved in their production, including LAB, acetic acid bacteria, Bacillus spp. and other bacterial groups, as well as yeasts and filamentous fungi. Among these, LAB represent one of the most extensively studied and widely applied microbial groups in fermented food systems, owing to their central role in fermentation processes and their well-documented technological and functional properties [11]. LAB are metabolically characterized by the production of lactic acid from carbohydrates, causing an acidic environment that inhibits some pathogenic bacteria’s growth and avoids spoilage, contributing to extending the shelf life of products [3]. In addition, they may yield secondary metabolites, like exopolysaccharides (EPS), bacteriocins, and enzymes, that are valuable to human health, as will be discussed in the next section.

These microorganisms are regarded as safe for consumption and fall under the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) designation. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a GRAS substance is one that qualified experts agree has been sufficiently proven to be safe for its intended use [11]. Among their numerous applications, LAB are most prominently known for their role in producing fermented dairy products. Nevertheless, they are capable of growing in a wide range of food substrates, including fruits, vegetables, and cereals [11,12], and many diverse strains have been isolated from traditional fermented foods and beverages worldwide [13].

Fermentation can be carried out traditionally, using microorganisms naturally present in the substrate (yeasts that develop on grapes, wild bacteria present in milk for cheesemaking, etc.), or by the method known as “backslopping,” which involves using a small amount of a previously fermented product to inoculate fresh substrate (yeasts and bacteria for sourdough), or through controlled fermentation with a starter culture [14]. Globally, fermented foods are often produced using artisanal methods that vary according to local raw materials, processing techniques, and microbial resources [15]. In such traditional fermentations, microbial populations are usually not tightly controlled, rendering these foods valuable reservoirs of largely unexplored microbial diversity with potential applications in the food industry [16]. In fact, microorganisms isolated from the indigenous microbiota of traditional fermented products are often considered particularly promising as starter cultures, as they are well adapted to the environmental conditions of the food matrix [17]. However, the traditional method has certain disadvantages, mainly significant fluctuations in product quality, but it is still used in some homemade products. Therefore, since the 20th century, in the industrial production of some fermented foods, defined starter cultures have been introduced instead of using spontaneous fermentations, to ensure process control, product uniformity, and large-scale reproducibility [13,14]. A starter culture is defined as a preparation containing a high number of viable cells, either from a single microorganism or from a consortium of two or more species, that is deliberately added to initiate fermentation and induce specific biochemical and sensory changes in the food product [18].

Additionally, non-starter bacteria can be added, which can contribute to flavor development, ripening, and improved product safety. Furthermore, these adjunct cultures can help restore microbial diversity that is reduced by pasteurization and other heat treatments. Some of these cultures may also have probiotic properties, as will be discussed later [19]. Certain LAB species, such as Lactiplantibacillus (Lpb.) plantarum, can function either as starter or adjunct cultures depending on the application. For example, Lpb. plantarum is commonly used as a starter culture in meat and wine fermentations, including malolactic fermentation, whereas in dairy products it is typically regarded as an nsLAB [20].

The selection of microorganisms to be used in fermentation processes requires a thorough evaluation of their metabolic capabilities and technological performance, since their functional properties may differ between laboratory conditions and real food systems. In addition, candidate cultures must be recognized as safe, amenable to industrial-scale production, and capable of maintaining viability and stability during storage [21].

2.3. Health Benefits of LAB-Fermented Foods

Although evidence linking fermented foods to health has increased significantly in recent years, further boosting their popularity, knowledge of the relationship between fermented foods and health is not new. Metchnikoff’s book “Prolongation of life: optimistic studies,” published in 1907, is well-known. In this work, the author, who had focused his research interests on the aging process and its possible relationship with the presence of “harmful” bacteria, postulated that yogurt consumption could contribute to prolonging life and improving its quality. These were the pioneering studies that gave rise to the current interest in the gut microbiota and the use of microbes to promote health [22]. The gut microbiota is the community of millions of microbes that inhabit our intestines and play a crucial role in maintaining immune and metabolic homeostasis, protecting against pathogens, and exerting a marked influence on the host during homeostasis and disease [9].

It is currently proposed that fermented foods can improve health through various mechanisms, including the nutritional modification of raw materials and the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds, the stimulation of the immune system, and the modulation of the human gut microbiota [6].

Microbial activity during food fermentation results in the enrichment or reduction in compounds that affect the nutritional composition of the final food product. Microorganisms consume high-calorie carbohydrates (glucose, sucrose, lactose, and fructose) present in milk, meat, and plants through catabolic pathways. This can reduce the glycemic index and improve tolerance to certain components (such as lactose in milk, fructans in wheat, or raffinose, stachyose, and fructose in soy and legumes) [23,24]. Fermentation also increases the digestibility of polysaccharides, proteins or fats, and promotes biodetoxification and the elimination of antinutritional factors (ANF). ANF are components of plant-based foods that can reduce the absorption of essential nutrients or form toxic compounds during decomposition. Their effect on human health is controversial, as some authors suggest possible beneficial effects, while others recommend their consumption only after processing [25]. However, our current knowledge makes it clear that the negative effects are beyond reasonable doubt, while the positive effects still need to be clarified. In this sense, several studies report that lactic fermentation of sauerkraut, pickled cucumbers, or soy products showed a decrease in the content of oxalates, tannins, and glucosinolates [26,27]. Lactic fermentation is also considered the best strategy for reducing the adverse effects of tannins in cereals and pseudocereals [28,29]. Remarkably, in a recent study bacterial species with potential to reduce ANF were identified using a pan-genome study of 351 bacterial genomes. Authors suggest a combination of bacterial species such as L. strains (DSM 21115 and ATCC 14869) with Bacillus subtilis SRCM103689 to maximize the reduction in the ANF concentration [26].

Lactic fermentation has been shown to enhance both the concentration and bioaccessibility of several vitamins and antioxidant compounds, including flavonoids and tannins [30,31,32]. Vitamins are essential micronutrients, as humans lack the capacity to synthesize most of them endogenously. Over recent decades, considerable attention has been given to the ability of LAB to biosynthesize vitamins—particularly those of the B complex—during food fermentation. Importantly, vitamin production is a strain-specific trait rather than a universal characteristic of LAB.

Riboflavin (vitamin B2) biosynthesis has been reported in multiple LAB species, including Lpb. plantarum, Limosilactobacillus (Lmb.) fermentum, Lacticaseibacillus (Lcb.) rhamnosus, Lmb. mucosae, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Enterococcus (Ent.) faecium, Lc. lactis subsp. lactis, and L. acidophilus [33]. Similarly, extracellular folate production has been documented in strains of Streptococcus (Strep.) thermophilus, L. amylovorus, Lpb. plantarum, L. sakei, and Lc. lactis [34,35,36]. In addition, cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthesis has been confirmed in several LAB species, including Ent. faecium, Ent. faecalis, Lcb. casei, Furfurilactobacillus rossiae, Lmb. reuteri, Lpb. plantarum, Loigolactobacillus coryniformis, Lmb. fermentum, and Lcb. rhamnosus [34,35,36,37]. LAB strains have also been reported to synthesize other essential micronutrients such as thiamine (vitamin B1), niacin (vitamin B3), and menaquinone (vitamin K2), further highlighting their potential to enhance the nutritional value of fermented foods [32].

On the other hand, a significant increase in antioxidant activity has been reported in several foods fermented with LAB, mainly due to the metabolism of phenolic compounds. Biotransformations include deesterification, hydrolysis, or conversion of phenols into individual acids (gallic, quinic, caffeic, p-coumaric, ferulic, dihydrocaffeic, dihydroferulic, vinylcatechol, vinylguaiacol). Lpb. plantarum, L. acidophilus, and Lcb. paracasei, in particular, are mainly involved in the fermentation of phenol-rich foods, as they can withstand a high content of phenolic compounds [38,39]. Furthermore, during industrial biotechnological processes, LAB are often exposed to oxidative stress, which occurs due to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species inside cells. However, several LAB strains have been found to possess key antioxidant defense enzymes with high specific activity. These include two types of catalases and NADH peroxidase, as well as NADH oxidase, superoxide dismutase, and thioredoxin reductase. LAB cultures with antioxidant activity are in high demand, as they can contribute to the prevention of cardiovascular, inflammatory, and oncological diseases [40].

Furthermore, the bioactive compounds produced during fermentation, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bioactive peptides, EPS, and bacteriocins, work together to strengthen intestinal mucosal defenses. Emerging clinical and preclinical evidence demonstrates that regular consumption of fermented dairy products improves gut microbial diversity, increases fecal and systemic SCFA levels, decreases pro-inflammatory cytokine activity, and improves metabolic biomarkers in dysbiosis-associated conditions. The SCFAs produced bind to G protein-coupled receptors, increase tight junction protein activity, and modulate immune signaling, thereby reinforcing barrier integrity and attenuating inflammation [41,42].

However, it is important to note that not all fermented foods contain live microorganisms at the time of consumption, and not all fermented foods offer health benefits beyond their nutritional value. For example, breads made with yeast are baked after fermentation, which effectively kills the fermenting microorganisms. Similarly, in the production of fermented beverages like most beers and wines, the live microorganisms are eliminated at the end of the process [6,43]. Notably, inanimate microorganisms and/or their components, called postbiotics, can confer health benefits, as will be discussed in the following sections. Similarly, the terms “fermented food” and “probiotic” cannot be used interchangeably. While some fermented foods contain live microorganisms and bioactive compounds that provide health benefits, the term “probiotic” should be reserved for cases where there is a proven health benefit provided by well-defined and characterized live microorganisms [44].

3. Through Traditional Probiotics to Next-Generation Therapeutic Applications

Currently, LAB remain among the most studied strains as probiotics thanks to their long history of safe use and the growing body of mechanistic and clinical evidence. LAB have demonstrated potential benefits through multiple strain-specific mechanisms, such as mucosal adhesion, competitive exclusion of pathogens, barrier function, modulation of the host immune response, and positive effects on energy, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism, among others. These findings have been confirmed in vitro, in animal models, and in human clinical trials [45].

However, the most robust clinical data are obtained with a limited set of well-characterized strains, since in many cases the benefits depend on the dose, the strain, the duration of treatment, and other factors. For example, Lcb. rhamnosus GG has consistent evidence supporting the prevention and treatment of acute and antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children, while strains of Bifidobacterium (B.) animalis subsp. lactis (e.g., BB-12) show efficacy in improving intestinal function and stimulating the immune system [46].

Consensus definitions and guidance from expert bodies emphasize that probiotic effects cannot be generalized across species or strains and require demonstration of safety and a health benefit in the target population under intended use. Rigorous strain identification, stability during processing and storage, and preservation of functional properties in the chosen delivery matrix remain critical challenges for translating LAB candidates into efficacious products [44]. In this regard, genomic analyses of LAB within the same species demonstrate that they possess a pangenome in which each strain contains dozens of unique genes, hundreds of accessory genes, and distinct plasmid profiles. This phenomenon has been termed genetic fluidity or genetic plasticity. A recent study by Fischer et al. [47] conducted a comparative analysis of Pediococcus (Ped.) pentosaceus strains and showed that antibacterial activity and acidification profiles differed among isolates. Bioinformatic analyses of the genomes of the three highest-ranking isolates revealed pronounced genomic plasticity, with a core genome of 1460 genes and between 91 and 161 additional strain-specific genes. Furthermore, the three strains harbored different sets of plasmids carrying genes encoding distinct bacteriocins. These genetic variations may extend to other bacterial species and could explain the differences in probiotic properties observed among strains belonging to the same species.

A desirable characteristic in bacteria proposed as probiotics is that they are able to withstand gastrointestinal transit and reach the colon in a viable state. Upon ingestion, they encounter major physiological barriers—chiefly gastric acidity and bile salts—that challenge their survival [48]. The extent to which LAB colonize or persist in the gut is highly strain-dependent. Traditional starter cultures, such Strep. thermophilus and Lc. lactis, generally survive only transiently, with their populations declining rapidly once consumption ceases [49]. Conversely, several probiotic strains—including Lcb. rhamnosus GG, B. animalis subsp. lactis BB12, and Lpb. plantarum WCFS1—have demonstrated prolonged persistence in the gastrointestinal tract. Their ability to adhere for days or weeks, and in some cases months, is attributed to specialized adhesion molecules and versatile carbohydrate-metabolism pathways [50].

Due to their innate stress tolerance and the protective properties of the food matrix, LAB derived from fermented foods can transiently represent approximately 0.1–1% of the bacterial population in the large intestine, with similar proportions observed in the small intestine [51]. These values reflect current estimates of the resident gut microbiota combined with the fact that a single serving of fermented products such as yogurt or kefir can contain up to 109 viable LAB cells [51].

Probiotics research expanded considerably throughout the twentieth century, driven by advances in molecular biology, genetic sequencing, and bioinformatics. These tools enabled detailed characterization of the human microbiome, revealing a vast reservoir of microorganisms that influence host physiology during both health and disease. As analytical technologies improved, researchers identified numerous previously unrecognized strains with probiotic potential [52]. This progress has paved the way for the development of next-generation probiotics (NGPs) and live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), including strains engineered or optimized through synthetic biology approaches [8].

NGPs are defined as live microorganisms discovered largely through comparative microbiota analyses and shown to confer health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. LBPs are regulated as biological products intended for the prevention, treatment, or mitigation of disease and are distinct from vaccines [53]. These emerging microbial candidates often represent taxa not traditionally used in food or supplement applications and are typically identified through NGS and computational analyses. Several promising NGPs originate from gut-associated genera such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia intestinalis, Eubacterium spp., and Bacteroides spp., which have been linked to modulation of inflammatory pathways, metabolic function, and cancer-associated mechanisms [54].

Probiotics can be delivered in the form of conventional foods, infant formula, pet foods, dietary supplements, drugs, cosmetics, and even medical devices, and are clearly positioned in consumers’ minds far from the controversial issue of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) or genetically modified foods [52]. On the contrary, the regulatory pathways for NGPs, particularly those developed using recombinant or genetically engineered techniques, remain under refinement. Their advancement toward clinical use requires comprehensive preclinical investigations followed by well-designed human trials to demonstrate safety, efficacy, and mechanistic validity [53].

As is well known, conventional probiotics have a long history of use and are generally considered safe at the strain level by the US FDA, while the EFSA considers them safe at the species level with a qualified presumption of safety (QPS). In the case of NGPs, it is currently uncertain whether they will be subject to additional regulatory requirements beyond those applied to conventional probiotics. However, any GMO intended for use in foods or supplements within the European Union must undergo evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms. In addition, microorganisms developed or marketed as medicinal products require authorization from the European Medicines Agency [52].

In the United States, regulatory agencies do not formally employ the term probiotic. Instead, microorganisms intended for use in foods or dietary supplements are referred to as live microbial ingredients, whereas those developed for therapeutic purposes are classified as LBPs. Accordingly, live microorganisms are regulated either as foods or as dietary supplements when consumed for nutritional purposes, or as drugs when intended for disease prevention or treatment. In this regulatory framework, NGPs derived from human commensal microbiota and developed for disease-specific applications are categorized as LBPs. Furthermore, genetically modified or “engineered” NGP are considered recombinant LBP, defined as products containing microorganisms that have been intentionally genetically modified by the addition, deletion or alteration of translational genetic material [54,55].

Within the European Union, EFSA oversees the safety assessment of microorganisms used in food and feed applications through the QPS framework, which provides a generic safety pre-assessment for selected microbial taxa. Although the QPS list has been periodically updated, it currently excludes most gut-derived NGPs and genetically engineered probiotics, with the exception of certain bifidobacterial genera [56,56]. Conversely, biologically active medicinal products derived from bacterial or yeast sources require formal evaluation and approval by the EMA before clinical use.

NGPs are selected or intentionally modified to produce specific metabolites, interact with specific host signaling pathways, or act on well-defined diseases. Genetic engineering and precision editing tools—such as CRISPR-Cas-based genome editing, recombinant DNA technologies, plasmid-based expression systems, and targeted mutagenesis—are applied to improve strain stability, metabolic performance, and host interaction profiles. These approaches, which enhance both the efficacy and reproducibility of probiotic interventions, thereby increasing their reliability in clinical and translational applications, will be discussed later [57].

Engineered or otherwise tailored NGPs are currently being developed for a range of specialized applications, including oral and dermatological health, modulation of immune responses, and management of conditions such as allergies, metabolic disorders, cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease [55]. Existing probiotics, such as LAB, are modified through gene editing, as will be discussed in subsequent sections.

Despite major scientific advances, the field continues to evolve as new microbial candidates, technologies, and therapeutic opportunities emerge. Ongoing research is essential to fully elucidate the health-promoting potential of both traditional and next-generation probiotics. Integrative approaches (combining genomics, in vitro phenotyping, and controlled clinical trials) could be useful to accelerate the discovery of next-generation probiotics with defined mechanisms and clinically significant outcomes.

Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis of LAB and Probiotics Associated with Fermentation

Over the past two decades, technological advances such as DNA and RNA sequencing, omics approaches (proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, etc.), microbiome studies, and the computational collection of clinical and research data have increased the generation of biological data.

Individual omic approaches study the components of a single organism under specific conditions (such as genomics for DNA or proteomics for proteins, etc.), while “metaomic” approaches study data obtained from a community of organisms across the entire community (e.g., metagenomics or metatranscriptomics).

Regarding the selection and characterization of LAB used as starter cultures and as probiotics, culture-dependent techniques remain the gold standard. However, omics-based approaches now serve as powerful complementary tools. The application of molecular methods, high-throughput sequencing (HTS), and metagenomic analyses has substantially advanced our understanding of the individual and collective roles of microorganisms in fermented food ecosystems, enabling targeted strain improvement and product optimization [58]. HTS technologies have transformed microbiological research by enabling rapid and comprehensive genomic characterization of microbial isolates, thereby addressing many of the limitations associated with culture-dependent analytical approaches [59]. In the context of food fermentation, genome sequencing of starter cultures has provided valuable insights into their evolutionary trajectories and domestication processes [60]. Comparative genomic analyses indicate that microbial adaptation to food-associated niches is frequently accompanied by gene acquisition and loss, reflecting selective pressures imposed by specific substrates and processing conditions [61]. A notable example is the study by Zheng et al. [62], which compared genomes of Lmb. reuteri strains isolated from the human gut and sourdough to elucidate the genetic changes underlying the transition of a gut-associated symbiont to a food-adapted microorganism.

Beyond evolutionary insights, bioinformatic tools play a crucial role in guiding the rational selection of starter cultures. Genome-based screening allows the identification of functional traits relevant to fermentation performance, including genes involved in bacteriophage resistance, exopolysaccharide production, and flavor compound biosynthesis [63]. Moreover, the growing availability of datasets from large-scale sequencing initiatives offers opportunities to mine genomic information for the discovery of novel starter and adjunct cultures with desirable technological and functional properties.

In addition, the contribution of omics approaches to studying probiotic strains includes i—genomics and metagenomics for studying the complete genetic potential of the probiotic strain or the entire microbial community, respectively [56,64,65], and ii—transcriptomics and metatranscriptomics for analyzing gene expression patterns to understand which genes are actively “switched on” under specific conditions. The introduction of high-throughput metagenomic sequencing has facilitated the analysis of microbes, including unculturable bacteria, at the strain level. Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics have enabled the discovery of new generations of probiotics and have improved our understanding of the human microbiome and its contribution to host physiology [66,67,68]. iii—Proteomics and metaproteomics have revealed the intricate connections between proteins in probiotic cells and their relationship with the host environment [66,69], and iv—metabolomics and lipidomics have characterized small-molecule metabolites and lipids produced during microbial metabolism, which directly influence host physiology and phenotype [70,71].

For example, the safety of strains used as probiotics is an increasing concern, as adverse effects such as infections, transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence genes, and other factors with a negative impact on health can occur. For large-scale strain risk assessment, genomic data obtained through whole-genome sequencing allows for the evaluation of safety markers to ensure the safe use of the product, and helps to understand the subtle strain-level differences that are important for beneficial effects [66]. In addition, accurate sequencing of the genome of reference strains shows differences between sequences, which may influence experimental results with subsequent consequences for bioprocess designs. For example, whole genome sequencing of Lmb. reuteri PNW1 showed the presence of several genes important for its action as a probiotic, including those associated with lactic acid production, mucosal adhesion, stress tolerance, and therapeutically useful peptides [64]. On the other hand, transcriptomic studies conducted by Rodrigues et al. [67] demonstrated the ability of L. johnsonii and L. gasseri strains to modulate liver activity, resulting in improved lipid metabolism through enhanced mitochondrial health in murine models with induced type 2 diabetes.

By combining data from various molecular levels, researchers can move beyond correlation to infer specific mechanisms of action, select more effective probiotic candidates, and develop personalized therapies. The integration of multi-omics data can be applied to the study of probiotics as a systems biology approach to holistically understand how they function and interact with their host and the native microbiota [72].

Remarkably, omics technologies have revolutionized sports nutrition by enabling personalized dietary and training strategies based on the integration of individual genetic, molecular, and metabolic profiles. Among the precision nutritional interventions tailored to optimize athletic performance and recovery are probiotic and NGP supplementation. In this sense, a recent study shows that oral administration of a probiotic strain of Bacillus subtilis modified and optimized to perform intestinal delivery of lactate oxidase reduced blood lactate elevations in murine models without altering gut microbiota composition, liver function, or immune homeostasis [73].

Bianchi et al. [71], to assess the quality and consistency of probiotics during large-scale manufacturing, used an integrated multi-omics approach. The researchers combined functional proteomics and metabolomics to delineate distinct protein and metabolic profiles between samples of a multispecies formulation produced at two different manufacturing sites. The research highlights that even minor variations in production methods can lead to significant differences in a probiotic’s molecular and functional properties. The study concluded that combined multi-level analysis is a reliable and powerful tool for quality assurance in the large-scale production of probiotics. It enables the detection of subtle, but functionally significant, variations that might otherwise be missed by traditional single-level analyses.

On the other hand, identifying the stress response mechanism of probiotic bacteria has always been of interest to the scientific community. This allows for the selection of probiotic bacteria that can survive the production, processing, and storage of food products. To achieve this, a better understanding of stress-induced responses and adaptive mechanisms is necessary [53]. Traditional omics approaches, along with more recent ones such as interactomics (the study of the set of interactions between different biomolecules in a given environment, especially focusing on protein interactions), fluxomics (an innovative field of omics research that measures the rates of all intracellular fluxes in the central metabolism of biological systems), and phenomics (the systematic study of an organism’s phenotypic traits), have the potential to provide detailed information on the mechanisms of stress-induced responses in bacteria [74].

Conventional molecular techniques offer a general overview, but whole-genome sequencing technology provides a deeper understanding of bacterial stress responses and adaptation to environmental stressors. However, it has proven insufficient to obtain comprehensive information about the complex mechanisms involved [74]. A multi-omics approach involving transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic technologies, complemented by conventional molecular tools, allows for the analysis of gene expression patterns to understand how bacteria regulate genes in response to stress.

The application of multi-omics technologies presents exciting opportunities for probiotic research, as it allows for a deeper exploration of probiotic-host interactions and the creation of advanced, personalized probiotics with specific and proven health effects.

4. The Postbiotic Frontier: LAB as Producers of Bioactive Compounds with Health Benefits

Historically, the ability of a probiotic to exert a health effect has been linked to its capacity to remain viable. Nonetheless, it has long been understood that non-living microorganisms, their structural components, and their metabolic products can also modulate host physiology. Numerous terms have emerged in the literature to describe such preparations—including non-viable or heat-killed probiotics, tyndallized probiotics, cell lysates, paraprobiotics, ghostbiotics, and postbiotics [75]. In 2021, the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) introduced a consensus definition, specifying that a postbiotic is a “preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host” [75].

Before the adoption of this standardized definition, the term postbiotic had been used inconsistently, often referring solely to microbial products present without the organisms themselves. In this context, many studies described compounds synthesized by LAB, such as organic acids, bioactive peptides, and bacteriocins—as postbiotics. These metabolites have been widely investigated for their ability to enhance food preservation, inhibit pathogens, and support host health, as discussed below [76].

Under the current definition, the postbiotic concept encompasses preparations in which the microorganisms are no longer viable—whether as intact, inactivated cells or as cellular fragments such as cell wall components. Many postbiotic formulations also include microbial metabolites, proteins, or peptides that may contribute to the observed health effects; however, according to the current definition, these molecules do not qualify as postbiotics [76]. Some examples are reviewed in Moradi et al. [77].

A very interesting study by Yavorov-Dayliev et al. [78] evaluated the ability of Ped. acidilactici CECT 9879 and the heat-inactivated strain to ameliorate gestational diabetes mellitus in mice. Their findings demonstrated that both preparations significantly reduced fasting blood glucose levels and insulin resistance during gestation, while simultaneously decreasing visceral adiposity, accompanied by an increase in muscle tissue and improvements in intrahepatic triglyceride content and ALT levels. These findings were mediated by modulation of the insulin receptor, but also by overexpression of beta-oxidation genes and downregulation of fatty acid biosynthesis genes. Furthermore, supplementation with the microorganism and the postbiotic formulation modulated the composition of the gut microbiota in mice, with Ped. acidilactici comprising 75% of the microbial profile after only nine weeks of supplementation.

Similarly, a postbiotic product made from Weissella (W.) cibaria was developed to enhance disease resistance in rainbow trout against the bacterium Yersinia (Y.) ruckeri. The product, consisting in heat-inactivating W. cibaria cells, increases the concentration of LAB in the fish’s gut, boosts the immune response by up-regulating the cytokine IL-1β, and improves survival rates against Y. ruckeri infection [79]. Additionally, Dunand et al. [80] sought to determine the effect of the cell-free fraction (termed postbiotic by the authors) of milk fermented with proteolytic strains of Lactobacillus against Salmonella infection in mice. The resulting postbiotics exhibited significant immunomodulatory and cytoprotective properties against infection. Consequently, these findings suggest that the metabolic stabilization of postbiotics represents a viable strategy for developing functional ingredients suitable for incorporation into food matrices where the maintenance of viable cell populations is technically unfeasible.

Numerous studies propose the use of bioactive compounds produced by former Lactobacillus gender for food safety purposes. They contribute to biopreservation, inhibit or eliminate biofilms formed by foodborne pathogens, and can support the degradation of hazardous chemical contaminants such as mycotoxins, pesticides, and biogenic amines. Their effectiveness in food systems is influenced by several factors such as the specific LAB strain from which the postbiotic is derived, the characteristics of the target microorganism or contaminant, the concentration and format in which the postbiotic is applied, and the physicochemical properties of the food matrix. In this sense, a study performed by Ebrahimi et al. [81] evaluated the postbiotic functionalities of both cell-free supernatant (CFS) and heat-killed cells of L. kunkeei, isolated from natural honey. The CFS was found to contain three distinct antibacterial peptides, verified by LC/MS analysis, and potent in situ antifungal activity against Candida albicans was reported in a sugar-free lemonade model. Furthermore, the L. kunkeei isolate, in both its viable and heat-inactivated forms, was effective in reducing total aflatoxins (specifically B1, B2, G1, and G2).

Numerous studies have reported that several species of LAB act as efficient producers of Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), converting L-glutamate to GABA via the glutamate decarboxylase system [82]. GABA is a non-protein amino acid that acts as a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system and is considered by some authors as a postbiotic with promising applications in the development of functional foods and pharmaceutical products due to the reported health benefits. In addition, the most recent work has focused on optimizing fermentation conditions, substrate utilization, and genetic modifications to improve GABA yields by LAB. The list includes strains of Lpb. plantarum, Levilactobacillus (Lev.) brevis, certain B. species, Ped. acidilactici, Lc. lactis and W. confusa [82,83,84]. Lev. brevis stands out, recognized as one of the most efficient high-level producers of GABA among LAB. For example, the Lev. brevis CRL 2013 strain, isolated from quinoa, can produce remarkably high levels of GABA, reaching around 2.7 g/L [85]. Furthermore, optimized fermentation in a bioreactor of the Lev. brevis NCL912 strain achieved GABA concentrations exceeding 100 g/L [86].

5. Current Overview of Biomanufacturing with LAB: Technological Innovation

The capacity of LAB to ferment carbohydrates and exert probiotic, immunomodulatory, and metabolic functions, including postbiotic activity, positions them as versatile platforms for functional food biofabrication [4,5]. Time has shown that LAB stand out for their versatility and robustness under controlled industrial conditions. In recent decades, the development of synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and AI has enabled the redesign of LAB strains with genomic precision, improving their performance, tolerance, and ability to biosynthesize functional compounds. Thus, their historical role in traditional fermentations has evolved toward precision biomanufacturing. This type of biomanufacturing seeks to transcend its traditional use as fermenting microorganisms, transforming them into cellular biofactories capable of producing bioactive peptides, vitamins, EPS, enzymes, and metabolites with technological or nutraceutical properties [87,88,89,90].

Moreover, the integration of biosynthetic sensors and automated control systems facilitates smart fermentations, capable of self-regulating parameters such as pH, oxygenation, or metabolic flux velocity, making the process more efficient and generating less waste. This paradigm shift is aligned with the vision of the circular economy and the transition towards smart and personalized foods [89].

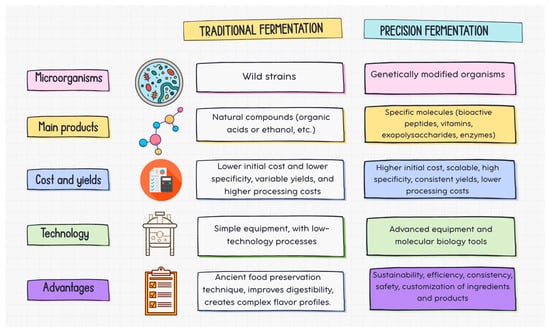

In summary, while traditional fermentation relies on wild microorganisms to carry out fermentation and produces general end products such as organic acids or ethanol, precision fermentation uses GMOs to produce specific molecules. Traditional fermentation has low specificity and variable yields, while precision fermentation is scalable, imparts high specificity and purity of the target product, and offers controlled production [90] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Traditional vs. precision fermentation.

5.1. Genetically Engineered Microbial Factories

CRISPR-Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and associated proteins) genetic editing has marked the beginning of a new era in precision bio-manufacturing. Historically, the genetic modification of LAB has been hindered by multiple intrinsic biological barriers [91]. The thick peptidoglycan-rich cell wall limits DNA uptake, resulting in low transformation efficiencies even under optimized electroporation conditions. In addition, strain-specific restriction–modification systems actively degrade foreign DNA, further reducing transformation success and reproducibility. Vector incompatibility and plasmid instability have also constrained heterologous gene expression in LAB hosts. Moreover, limited homologous recombination efficiency and DNA repair mechanisms have historically restricted precise chromosomal engineering. The high physiological variability among LAB strains has required extensive protocol optimization, which prevents standardization [91]. The implementation of CRISPR-Cas9 has overcome many of these traditional challenges associated with LAB genetic modification. Since then, editing using CRISPR-Cas9 in LAB has primarily aimed to enhance their functional properties for industrial, food, and medical applications, overcoming the limitations of traditional random mutagenesis and homologous recombination techniques (Table 1). Studies such as those by Rostampour et al. [92] have explored the diversity and distribution of natural CRISPR-Cas systems in Lpb. plantarum strains. Identifying and characterizing these endogenous systems is crucial for developing more efficient, native genome-editing tools, thereby avoiding the potential cytotoxicity of heterologous Cas effectors and facilitating the genetic manipulation of diverse LAB species.

Table 1.

Comprehensive review of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology applications in LAB.

CRISPR-Cas9 system enables the generation of improved strains with optimized traits—from enhanced phage resistance to increased metabolite production and probiotic efficacy—opening new avenues in food biotechnology and advanced biomedical applications [101,102,103]. LAB are widely employed as starter cultures in the dairy industry, where bacteriophage infections can compromise entire fermentation batches. In 2007, studies using Strep. thermophilus demonstrated that CRISPR loci, together with their associated cas genes, confer adaptive immunity against bacteriophage infection [63]. The phage-resistant strains obtained allowed for greater stability and consistency in the production of fermented foods.

The implementation of genome editing tools has allowed the fine-tuning of metabolic pathways to promote the overproduction of specific metabolites [92,104]. LAB have been genetically modified to enhance the biosynthesis of GABA, functional EPS, and natural antioxidants [83,99].

Lpb. plantarum is a versatile starter culture and probiotic chassis whose industrial potential depends on precise, plasmid-free genome engineering. Using a CRISPR/Cas9-assisted recombineering platform combining dsDNA and ssDNA templates, seamless knockouts, insertions, and point mutations were achieved and further optimized through phosphorothioate protection and adenine-specific methyltransferase–enhanced recombination. This strategy enabled the construction of an engineered Lpb. plantarum WCFS1 strain producing 797.3 mg/L N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), highlighting its value for advanced LAB metabolic engineering and future industrial applications [93]. This probiotic Lpb. plantarum was genetically modified to optimize its biosynthetic pathway. Precise genome editing, which included targeted gene truncation and the strategic relief of metabolic feedback repression, resulted in the overproduction of GlcNAc, a commercially valuable compound used in joint and gastrointestinal health supplements. This work demonstrates a highly efficient strategy for the rapid and scalable development of industrial strains.

Wang et al. [94] engineered Lpb. plantarum strains with single, double, and triple deletions of bile salt hydrolase (bsh) genes using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Their findings revealed that bsh1 and bsh3 are closely associated with bile salt resistance, thus enabling the selection of strains with higher tolerance and improved probiotic viability. Another notable example of metabolic engineering is the modification of Lcb. paracasei through ldhD (D-lactate dehydrogenase) gene inactivation and the introduction of the ldhL1 (L-lactate dehydrogenase) gene [95]. This modification converted the strain into a high optical purity L-lactic acid producer, a compound of significant industrial value. Several studies have employed genetically engineered LAB to achieve high lactic acid concentration while simultaneously valorizing lignocellulosic biomass. Fermentative production of lactic acid from lignocellulosic feedstocks provides a renewable and sustainable alternative to conventional raw materials [95].

Current research indicates a pivotal shift in CRISPR/Cas9 applications, moving beyond the functional characterization of model strains toward the enhancement of ecological fitness in complex industrial environments. A prime example of this trend is the recent work by Ma et al. [98], who utilized CRISPR/Cas9 to optimize Lactobacillus spp. specifically for silage production. By targeting traits essential for survival and dominance in fermenting plant biomass, this study highlights the capacity of genome editing to secure process stability in agricultural biotechnology, thereby supporting sustainable livestock development and food security.

The paradigm of LAB engineering is rapidly expanding from traditional fermentation to the development of sophisticated LBPs. A seminal advancement in this domain is the repurposing of native CRISPR-Cas systems to engineer strains capable of secreting human therapeutic peptides, circumventing the regulatory and stability challenges associated with exogenous plasmids. Addressing the global burden of Type 2 Diabetes, Zheng et al. [96] successfully exploited the endogenous Cas9 system of Lcb. paracasei to engineer the stable expression of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). This innovative, orally administrable strain offers a promising strategy for enhancing patient compliance in treating diabetes. The contrast between the work of Zhou et al. [93] using exogenous Cas9 with helper plasmids (recombineering) and Zheng et al. [96] focusing on native systems highlights a critical shift. While exogenous systems offer high efficiency (demonstrated by the GlcNAc yield); native systems are being pursued to reduce metabolic burden and cytotoxicity, which is crucial for the stability of therapeutic strains.

Recent advancements demonstrate that CRISPR-Cas technology in LAB has matured beyond elementary gene inactivation to facilitate sophisticated metabolic flux engineering. A notable application of this strategy is the transcriptome-guided engineering of Lpb. plantarum, where the CRISPR/Cas9 system was employed to characterize the niacin transporter lp2514. By validating this transporter’s pivotal role, Kong et al. [97] achieved a targeted metabolic rearrangement that optimized the biosynthesis of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN). Similarly, complex pathway modulation—including the relief of feedback inhibition—has been successfully applied to enhance GlcNAc production [93]. Together, these studies highlight the potential of CRISPR-assisted metabolic rewiring to transform LAB into robust cell factories for high-value nutraceuticals production.

Therefore, the CRISPR-Cas technology has revolutionized microbial genetic engineering by enabling precise and efficient genome modification in LAB; in addition, these advances enable the optimization of parameters such as growth rate, substrate consumption, and the production of desired metabolites, thereby reducing batch-to-batch variability and environmental impact [63,92,93,98,100].

5.2. Technological Convergence: AI, Synthetic Biology, and the Multi-Omics

The current trend is to transform LAB into intelligent microbial cell factories by integrating synthetic biology, bioreactor automation, and AI-based control systems. This technological convergence enables the sustainable production of bioactive compounds (bioactive peptides, EPS, B-group vitamins, antioxidant enzymes, among others) with full traceability and adaptability to specific health or nutritional demands [53]. Recent studies have demonstrated that supervised ML (AI algorithms) models applied to whole-genome datasets can successfully predict quantitative LAB capabilities, such as acidification kinetics and technological performance, by learning associations between genomic features and phenotypic outputs. These data-driven approaches allow the identification of predictive genomic signatures without prior mechanistic assumptions and are particularly well suited to the high dimensionality and strain-level variability characteristic of LAB. Supervised ML architectures, such as Random Forest algorithms, have been implemented to analyze LAB whole-genome sequences for the high-fidelity prediction of quantitative phenotypes. For instance, these models have successfully forecasted maximum acidification rates in Lc. lactis by leveraging diverse genomic feature representations. These include gene family presence/absence profiles, Pfam domain frequencies, and DNA-based k-mer subsequences (specifically 8-mers and 9-mers), enabling a robust correlation between genotypic variation and metabolic performance [105].

Additionally, ML approaches have been deployed to classify LAB at the species and subspecies level using phenotypic signatures such as single-cell Raman spectral profiles, achieving outstanding classification performance through ensemble learning, illustrating how pattern recognition techniques can resolve fine taxonomic and functional distinctions among LAB strains [106]. These examples underscore the potential of combining omics-driven data with AI/ML frameworks to uncover genotype–phenotype relationships in LAB, facilitating predictive functional profiling and rational strain selection for fermentation and probiotic applications. Dai et al. [107] detail an approach that combines ML and genome-scale analysis, which is related to metabolic flux, to predict the sensory characteristics of milk fermented by Lc. lactis. The goal was to provide support for optimizing strain selection and precisely controlling the flavor quality of the final product. The methods allowed for the effective identification of key features influencing multiple phenotypes, likely originating from their regulation by similar biological pathways or metabolic processes, thereby enhancing the understanding and control of flavor profiles in fermented dairy products. This study exemplifies how AI can significantly enhance the sensory quality of fermented dairy products.

Beyond flavor, AI and multi-omics tools are being applied to engineer functional attributes. Predictive modeling is actively used to optimize EPS synthesis in Lpb. plantarum [108]. Recent studies on the fermentation of tropical fruit juices, such as rambutan juice, utilized multi-omics analysis to unravel the dynamics of mixed LAB cultures [109]. The analysis revealed distinct synergistic mechanisms: Lpb. plantarum enriched the juice with organic acids and terpenes, while Lmb. fermentum promoted the accumulation of short-chain alcohols and aromatic compounds. The resulting co-fermentation enhanced flavor complexity and overall antioxidant activity. These data guide the precise application of probiotic strains and process optimization for developing high-value functional juices.

In complex traditional food fermentations, like Chinese Baijiu liquor, a combination of ML and multi-omic integration (microbiome and metabolome) has been instrumental in identifying critical quality markers. For example, nine microbial and twelve specific flavor markers were associated with successful fermentation [110]. The identification of Ligilactobacillus and Lactobacillus overabundance in abnormal fermentations, which led to off-flavors due to excess acids and esters, allows for robust, AI-predicted, microbial-biomarker-based quality control.

The application of AI extends beyond food product optimization to fundamental bacterial phenotype prediction directly from whole-genome data. Edirisinghe et al. [111] developed an ML approach to accurately predict core phenotypes, such as Gram staining and bacterial respiration types (aerobic, anaerobic) from genomic annotations. This capability is vital for the automated, high-throughput construction of quality in silico metabolic models, which is critical for accelerating research into the metabolic potential and biotechnological applications of uncharacterized LAB strains.

The complexity of multi-omic data requires advanced integration strategies. Multi-Omic Integration by ML Frameworks are being developed to efficiently integrate diverse datasets (genomics, metabolomics, etc.) [73,112,113]. These frameworks enhance computational performance for data integration and gene-metabolite association identification, thereby predicting complex phenotypes with greater robustness and speed than conventional methods.

The ultimate frontier involves the convergence of AI with synthetic biology and microbiome science. Synthetic biology provides modular genetic circuits to program specific functions into LAB, such as the sensing and response to environmental signals or the controlled release of target metabolites [114]. These strategies illustrating the potential for AI-guided strain engineering in functional food development are transforming LAB into “biointelligent systems,” capable of autonomous interaction with their environment. The integration of AI tools with computational synthetic design is leveraging evolutionary algorithms to accelerate the development of next-generation strains with adjustable metabolism and optimized performance. Concurrently, microbiome science provides the necessary contextual information to select LAB combinations that it should be compatible with the human gut community, ensuring functional efficacy [6,103]. The technological trifecta—AI, synthetic biology, and microbiome data are automated ecosystems where AI designs, evaluates, and selects optimized strains. These platforms drastically reduce R&D costs, accelerate the development of personalized functional products, and catalyze the transition toward traceable, biofabricated foods (Figure 1) [92,115]. The cornerstone of this evolution is the application of synthetic biology tools, such as CRISPR-Cas9, to create Genetically Engineered Microorganisms (GEMs) with precisely tuned metabolic pathways to produce functional bioactives and/or those relevant to human health. However, the inherent complexity of LAB metabolism requires AI to navigate the Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle. AI-driven platforms (AutoCRISPR) use deep learning to predict gene-editing outcomes and minimize metabolic burden in LAB significantly reducing research and development timelines from months to weeks [116]. With regard to bioprocess control, AI is driving its optimization. Scaling up the production of bioactives derived from Lactobacillus faces challenges related to batch consistency and environmental sensitivity. The implementation of Digital Twins (DT) and Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms has emerged as a critical solution. DT provides a high-fidelity simulation environment that replicates behavior in real time, and RL is an algorithm that acts as an ‘agent’ that makes sequential decisions within the digital twin for greater efficiency or lower consumption. The implementation of DT with RL algorithms has become established in 2025 as a critical solution for industry due to its ability to optimize complex systems in zero-risk environments. These AI models simulate the fermentation environment in real time, allowing for split-second adjustments to pH, temperature, and nutrient feeding within the bioreactor [90]. Studies indicate that RL-optimized systems can reduce batch failures by 60% and improve the purity of metabolites—such as specialized enzymes or postbiotics—to levels exceeding 98% [90,116]. This hardware and software architecture is essential for stabilizing the growth of sensitive Lactobacillus strains during high-volume industrial scaling.

Despite these technological advances, significant obstacles remain. The scalability of precision-fermented LAB is often limited by a lack of regional bio-manufacturing infrastructure and high initial capital costs (Figure 2). From a regulatory standpoint, bioactive derived from modified Lactobacillus must navigate the Novel Foods framework (EU Regulation 2015/2283 [117]), a process that can exceed three years. In conclusion, the convergence of AI and synthetic biology is effectively transforming LAB into a strategic pillar of the bioeconomy. While technical and regulatory barriers remain, the ability to programmer LAB and control industrial scaling with precision promises a more resilient, sustainable and personalized global nutrition system.

5.3. Intelligent Microbial Factories and Next-Generation Food Matrices: A New Paradigm for Food Sustainability

The holistic integration of sustainability, precision biomanufacturing, and multi-omics—governed by the overarching framework of AI and synthetic biology—not only enhances end-product quality but also establishes a fundamentally sustainable production paradigm. This synergy represents the current state of the art in the transition toward a circular bioeconomy, where maximum metabolic efficiency converges with ecological stewardship.

Within this framework, high-resolution optimization via RL has emerged as a disruptive catalyst. Recent evidence highlights that RL-optimized systems function as sophisticated ‘autonomous agents’ capable of navigating the complex, non-linear metabolic landscapes and fluxomes of LAB. By processing high-throughput, real-time data streams, these AI-driven models achieve unprecedented operational resilience, resulting in a reduction in batch failures through the preemptive correction of deviations in critical fermentation parameters (e.g., pH, dissolved oxygen, and substrate titration) [118]. Consequently, this prevents the substantial waste of raw materials and hydro-resources.

Furthermore, this precision architecture enables the attainment of molecular purities exceeding 98% for high-value metabolites, such as specialized enzymes and postbiotics [92,115], meeting the stringent requirements for pharmaceutical-grade applications within the food matrix. The robustness of this model is underpinned by multi-omic profiling—integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics—which provides the comprehensive datasets necessary for synthetic biology to program modular genetic circuits and orthogonal pathways. Such capabilities facilitate the metabolic engineering of LAB strains that are not only hyper-productive but also resource-efficient, serving as the genomic blueprint for biotechnological sustainability. Ultimately, the strategic implications for the global food system are profound: by minimizing carbon footprints through optimized energy consumption and maximizing nutrient bioconversion rates, LABs are positioned as the backbone of a next-generation precision manufacturing infrastructure.

The valorization of agri-food by-products is a key component for advancing sustainable food systems, with the circular economy acting as a driver of the optimal use of resources, reducing the environmental impact [119]. Complementarily, the use of LAB in the fermentation of alternative matrices offers a biotechnological strategy that not only reduces waste but also enhances the nutritional and functional profile of the resulting products. Recent studies have applied LAB strains to substrates such as grape pomace, cocoa bean shells, apple pomace, and defatted hazelnuts to produce yogurt-style fruit beverages [120]. All fermentations produced desirable aromatic compounds without off-flavors, and typical fermented notes developed. Moreover, LAB-derived secondary metabolites may contribute additional health-promoting properties to the beverages. Despite the growing potential of LAB-mediated these bioprocesses, several barriers continue to limit their large-scale deployment. Challenges persist in process scalability, implementation costs, and heterogeneous regulatory frameworks, as well as in consumer perception—particularly in plant-based fermentations—where improvements in nutrient bioavailability, antinutrient reduction, and sensory performance remain essential. Ensuring the food safety of LAB-fermented products derived from agri-food by-products also requires rigorous toxicological, agronomic efficacy, and life-cycle assessments, especially when these materials are intended for use as biofertilizers or other bioproducts. In acidic waste streams such as acid whey, further optimization of fermentation formulations is needed to achieve functional, nutritionally adequate, and sensorially acceptable products [121]. Collectively, these constraints highlight the need for integrated technological, regulatory, and consumer-centered strategies to fully realize the contribution of LAB-based valorization to sustainable and competitive agri-food innovation.

Agricultural waste can also be used as a substrate in symbiotic fermentation. Synbiotic fermentation consistently enhanced probiotic viability, acidity, and organic acid production, while immobilized systems exhibited superior growth kinetics, shorter lag phases, and markedly improved gastrointestinal survival during in vitro digestion. Agro-industrial residues functioned as efficient, low-cost immobilization supports due to their porous structure, enabling high cell adherence and protection. A broad range of probiotic strains—including Lpb. plantarum, Lcb. casei, L. acidophilus, Strep. thermophilus, B. longum, Lmb. reuteri, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Lcb. rhamnosus, and B. bifidum—was applied to soymilk fermentation using both free cells and synbiotic formulations immobilized on agro-industrial residues such as okara, whey protein, fruit peels, and sugarcane bagasse [122]. The integration of precision manufacturing into the valorization of these agri-food by-products would establish a fundamentally sustainable production paradigm.

6. Emerging Applications in Personalized Nutrition

The interconnection between LAB and personalized nutrition enables the development of food matrices precisely tailored to individual metabolic profiles. The LAB-personalized nutrition axis constitutes one of the most promising frontiers in contemporary food biotechnology. As human microbiome studies reveal causal relationships between gut bacteria, circulating metabolites, and metabolic health, LAB emerge as highly effective biological delivery vehicles for the targeted modulation of physiological functions [123].

Recent applications involve the utilization of designer LAB engineered for the production of specific bioactive compounds—such as modified polyphenols, SCFAs, or microbial neurotransmitters—that can act on metabolic, immunological, or neuroendocrine axes [2]. Strains of Lc. lactis and Lmb. reuteri have been genetically engineered to produce GABA and tryptophan hydroxylase, demonstrating a positive impact on metabolic regulation [99,124]. Furthermore, LAB are being integrated into digital nutrition platforms that combine microbiome data with AI predictive algorithms, facilitating the design of functional foods meticulously adjusted to individual metabolic signatures. These approaches rely on personalized metabolomics, which allows for the determination of an individual’s metabolic response to a specific food and the dynamic adjustment of fermented product formulations. Some authors have collectively defined the central tenets of precision nutrition and personalized medicine, positioning the gut microbiota as the most critical and dynamic therapeutic target. Fabozzi et al. [125] propose precision nutrition as a superior strategy for patients with infertility, using ‘deep phenotyping’ (metabolomics and nutrigenetics) to design specific dietary patterns. Personalized intervention seeks to modulate redox status and inflammatory response by precisely adjusting micronutrients (vitamins D, E, C, B12) and minerals (zinc, selenium) according to the patient’s genetic needs and microbiota profile. Ames et al. [126] analyze how nutrition in the early stages of life acts as a dynamic system that programs long-term health. They define direct breast milk as the ‘gold standard’ of personalized nutrition, as its composition changes in real time to adapt to the infant’s needs. Breast milk contains unique bioactive components (oligosaccharides, live cells) that cannot be fully replicated in infant formula or processed donor milk. These personalized nutrients drive the development of the gut microbiome and the maturation of the immune system through epigenetic mechanisms and the regulation of the ‘weaning reaction’, establishing antigen tolerance and preventing immune-mediated diseases in the future. Abeltino et al. [127] delve into the gut microbiota as the central mediator between diet and the host’s metabolic health. The study highlights the role of microbiota-derived metabolites, such as SCFAs, in regulating glucose and lipid pathways, as well as in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Personalized medicine must consider the unique enzymatic capacity of each individual’s microbiota to break down complex carbohydrates and phytochemicals. By integrating metagenomic sequencing data with lifestyle habits, it is possible to design diets that optimize neuroendocrine signaling and prevent chronic metabolic diseases.

The recent advances in microbiome research have fundamentally reshaped the conceptual framework of precision nutrition. Fabozzi et al. [125], Ames et al. [126] and Abeltino et al. [127] established the foundational concept, emphasizing that the gut microbiota is the key to unlocking precision nutrition. It is no longer enough to look at macro- or micronutrients; the focus must be on how an individual’s unique microbial community (the phenotype) processes these nutrients and, consequently, influences overall health.

The convergence of gut microbiota profiling in Smart Neuronutrition marks a transformative era in precision medicine [128]. Central to this evolution is the role of LAB within the gut–brain axis; these organisms act as metabolic transducers, converting dietary fibers into neuroprotective metabolites that mitigate neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. By leveraging multi-omic integration—encompassing metagenomics and metabolomics—researchers can now decode the functional phenotype of an individual’s microbiota. AI serves as the critical analytical engine, synthesizing multimodal data from wearable sensors and omics pipelines to predict cognitive trajectories and personalize probiotic interventions. However, a critical transition is required from black-box ML to explainable AI to ensure biological transparency [128]. Future advancements must prioritize strain-level genomic specificity and standardized clinical frameworks to translate these complex microbial interactions into scalable, equitable strategies for neurodegenerative prevention. The consensus across these works is clear: the future of health management is not a one-size-fits-all diet, but a data-driven feedback loop where deep biological insights (genomics, inflammation, microbiota) inform highly specific nutritional interventions to optimize individual phenotypes and promote health.

These innovations position LAB as central agents in the development of intelligent functional foods, designed to interact with the consumer’s gut microbiome to promote an optimal health status. In this regard, the convergence of biotechnology, personalized nutrition, and data science fundamentally redefines the boundary between food and medicine. By integrating AI with gut microbiome data, researchers can design LAB to produce specific molecules. This precision enables the development of hyper-personalized nutrition that addresses specific metabolic gaps or immune deficiencies, fundamentally redefining the role of LAB in the nexus between food and health. Furthermore, the use of AI in microbiome-targeted diets raises ethical concerns regarding data privacy and potential algorithmic biases [116].

7. Projections for the Integrated Precision Food Biomanufacturing Ecosystem

Despite compelling advancements in engineering LAB as versatile bio-manufacturing platforms, significant conceptual, technical, and regulatory challenges persist, impeding the full consolidation of this technology within advanced food biomanufacturing. One fundamental difficulty lies in the inherent genomic and phenotypic complexity of LAB. Intra-species diversity results in highly heterogeneous physiological responses to different environmental conditions and substrates. This heterogeneity is largely underpinned by a pronounced genetic fluidity or genetic plasticity, which dictates that functional and probiotic effects cannot be generalized across species or even individual strains. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that Pediococcus strains possess an expansive pan-genome in which the core genome may represent only a small fraction (e.g., 22%) of the total gene families [129]. The remaining repertoire comprises hundreds of accessory genes and strain-specific singletons, further diversified by the presence of varying sets of plasmids—typically ranging from three to six—and horizontally transferred elements such as prophages. Such extensive genetic variation results in markedly different metabolic capabilities, including variable carbohydrate utilization and disparate antibacterial profiles, even amongst closely related isolates [47]. Consequently, this inherent variability severely complicates the development of the accurate metabolic models that are crucial for precision engineering.

Furthermore, evolutionary adaptation within industrial fermentation environments can induce spontaneous mutations, compromising the genetic stability and technological performance of engineered strains over successive batches [130]. The maintenance of designed metabolic pathways in large-scale, long-term industrial settings remains a critical, often understated, technical hurdle.

A major technical bottleneck is the robust integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics) into truly predictive models. While AI tools possess the capability to process massive data volumes, the standardization of comprehensive datasets across different laboratories and the resulting reproducibility of predictive outcomes remain significant limiting factors. Current data frameworks often lack the necessary complexity and validation to confidently translate in silico predictions into reliable industrial yields [131].

The global adoption of genetically modified LAB (GMLABs) is severely hampered by disparate and stringent regulatory frameworks [132]. Particularly in jurisdictions like the European Union and parts of Latin America, stricter regulations concerning GMOs in functional foods contrast sharply with policies in Asia and the United States. This regulatory fragmentation significantly slows industrial uptake and stifles innovation, particularly in emerging markets.