Abstract

Alcoholic liver injury (ALI) is a major global public health issue, with oxidative stress imbalance as its core pathological mechanism. The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1–nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2–heme oxygenase-1/glutathione peroxidase 4 signaling pathway (Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4) signaling pathway is a key target for regulating hepatic antioxidant defense. This study integrated Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) molecular networking, network pharmacology, and animal experiments to systematically explore the hepatoprotective effect and mechanism of Cornus officinalis yeast-fermentation (COF). Component characterization identified 25 bioactive components, including flavonoids, triterpenic acids, and other fermentation-derived metabolites. Network pharmacology identified 441 common targets and 36 core targets of COF and ALI, which were enriched in oxidative stress regulation, inflammatory response, and the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway via Gene Ontology (GO)/Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. Molecular docking showed that icariin and other components had stable interactions with Keap1 and Nrf2 (binding energy < −5 kcal/mol). Animal experiments confirmed that COF reduced the liver index of ALI mice, downregulated serum Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT)/Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) activities, and ameliorated liver pathological damage. Western blot verified that COF inhibited Keap1 expression, promoted Nrf2 nuclear translocation, and upregulated HO-1/GPX4 expression. In conclusion, COF alleviates hepatic oxidative stress by regulating the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway, providing a scientific basis for its development as a functional food or candidate drug against ALI and a technical paradigm for fermentation-enhanced medicinal plant research.

1. Introduction

Alcoholic liver injury (ALI) is one of the primary causes of chronic liver diseases worldwide. Its incidence has been continuously increasing with the globalization of alcohol consumption, posing a significant health challenge that burdens public health systems [1]. The pathological mechanism of ALI involves complex interactions among oxidative stress, inflammatory cascades, and lipid metabolism disorders. Among these factors, the excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the core driver triggering hepatocyte damage—acetaldehyde produced during alcohol metabolism and abnormal fatty acid β-oxidation disrupt the liver’s redox balance, leading to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis [2].

In the body’s antioxidant defense system, the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1-nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Keap1–Nrf2) signaling pathway plays a central regulatory role. Its downstream effector proteins, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), are key molecules maintaining liver oxidative homeostasis. Under physiological conditions, Keap1 acts as an adapter protein to bind Nrf2, mediating Nrf2 degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway to maintain its low basal expression. When exposed to alcohol-induced oxidative stress, Keap1 undergoes conformational changes and dissociates from Nrf2; free Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus, specifically binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), and further initiates the expression of downstream antioxidant molecules such as HO-1, GPX4, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [3]. Among these, HO-1 directly scavenges ROS by degrading heme to produce antioxidant substances (e.g., carbon monoxide and bilirubin); GPX4, a key enzyme that inhibits lipid peroxidation, blocks ferroptosis-mediated hepatocyte death by catalyzing the reaction between glutathione and lipid peroxides [4]. However, long-term excessive alcohol consumption disrupts the dynamic balance of the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway, and sustained high expression of Keap1 inhibits Nrf2 activation, leading to downregulated expression of HO-1 and GPX4, a sharp reduction in liver antioxidant capacity, and ultimately exacerbating liver tissue inflammation and fibrosis [5]. Therefore, targeted activation of the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway to rebuild the liver’s oxidative defense barrier has become a core research direction in the field of ALI prevention and treatment.

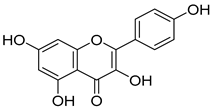

Due to their advantages of multitarget synergistic regulation and low toxicity, plant-derived natural products have attracted considerable attention in ALI intervention research [6]. For decades, especially since the late 20th century, extensive studies worldwide have focused on identifying and developing hepatoprotective plants for the prevention and treatment of liver diseases, including ALI [7]. A large number of medicinal and edible plants from different regions have been validated for their hepatoprotective potential: for instance, maca (Lepidium meyenii) polysaccharides alleviate alcoholic liver oxidative injury by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities [8]; Panax notoginseng residue-derived polysaccharides ameliorate ALI through activating Nrf2 signaling and regulating alcohol metabolism pathways [9]; and icariin, a flavonoid from Epimedium brevicornum Maxim., exerts hepatoprotective effects by targeting Keap1 to activate the Nrf2 pathway and inhibit oxidative stress and inflammation [10]. These studies collectively highlight the value of plant-derived natural products as promising candidates for ALI therapy. Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc. (CO), a traditional edible medicinal plant in East Asia, has been used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for more than 2000 years; its dried mature pulp is typically prescribed to “nourish the liver and kidneys, and astringe essence to prevent collapse” [11]. Modern pharmacological investigations, spanning from early phytochemical analyses to recent mechanism-focused studies, have confirmed that the hepatoprotective activity of C. officinalis is closely associated with its abundant bioactive components, including iridoid glycosides (loganin, morroniside), triterpenic acids (ursolic acid), and polyphenols (7-O-galloyl-D-sedoheptulose) [12,13,14]. Specifically, loganin alleviates oxidative damage by increasing SOD activity and decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in liver tissue; ursolic acid inhibits inflammatory responses by downregulating the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6); and 7-O-galloyl-D-sedoheptulose improves hepatic steatosis by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) [15]. Despite the preliminary verification of the hepatoprotective potential of C. officinalis, systematic and in-depth mechanistic studies are still lacking regarding whether it affects ALI by regulating the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway and how its key bioactive components modulate this pathway.

Microbial fermentation technology has emerged as a key approach to significantly increase the bioactivity and bioavailability of plant-derived components in recent years [16]. Among the various fermentation strategies, yeast fermentation is safe and efficient for biotransformation: via its own enzyme systems (e.g., glycosidases and esterases), yeast degrades macromolecular complex components in C. officinalis (e.g., polysaccharides and iridoid glycosides) into small-molecule bioactive metabolites (e.g., aglycones and short-chain fatty acids) while reducing component cytotoxicity and improving intestinal absorption efficiency [17]. Previous studies have confirmed that yeast fermentation can significantly increase the pharmacological activity of C. officinalis; for example, the conversion efficiency of iridoid glycosides to aglycones in fermented C. officinalis increases by more than 35%, and its neuroprotective activity is twice that of unfermented samples [18]. In addition, yeast metabolism may produce novel bioactive components (e.g., phenolic acid derivatives and terpenoid secondary metabolites) that synergize with the original plant components to expand its pharmacological activity spectrum [19]. However, clear evidence is still lacking regarding the chemical composition profile of yeast-fermented C. officinalis (COF), fermentation-specific metabolites, and whether COF improves ALI by regulating the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway—which has severely restricted its development as a functional food or hepatoprotective candidate drug.

The integrated research strategy combining metabolomics, network pharmacology, and in vivo experimental verification has become a core technical framework for deciphering the complex “multicomponent, multitarget, multipathway” mechanism of traditional herbal medicines [20]. Ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) combined with the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform enables high-throughput and high-sensitivity characterization of chemical components in COFs—it not only identifies known bioactive components but also captures trace and novel metabolites produced during fermentation [21]. Network pharmacology predicts the key targets and core pathways (especially the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway) of COFs in ALI by constructing a “COF component–ALI target–signaling pathway” interaction network on the basis of component structural characteristics and target biological functions [22]. Furthermore, in an alcohol-induced ALI animal model, systematic verification of network pharmacology predictions can be achieved by detecting liver injury markers (ALT, AST), oxidative stress indicators (MDA, SOD, and GSH), inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-6), and the expression levels of key molecules in the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway (Keap1, Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4), which provides direct evidence for clarifying the molecular mechanism by which COFs improve ALI.

On the basis of the above background, this study aimed to systematically explore the protective effect of COF on ALI and its molecular mechanism. The specific research contents include a comprehensive characterization of the chemical composition profile of COFs via UPLC-MS-MS/MS combined with GNPS technology to clarify fermentation-specific newly added metabolites and the variation law of bioactive components; construction of a “COF component–ALI target” network via network pharmacology to screen key functional targets and predict core regulatory pathways, with a focus on the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1–GPX4 pathway; and establishment of an alcohol-induced mouse ALI model to verify the ameliorative effect of COF on liver tissue pathological damage and its regulatory role in the expression of key molecules in the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1–GPX4 pathway. This study provides a scientific basis for the development of COFs as functional foods for ALI prevention and treatment and simultaneously offers new insights into mechanistic research on enhancing the bioactivity of medicinal plants via microbial fermentation technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Dried Cornus officinalis pulp (Hongxiang Chinese Medicine Technology Co., Ltd., Yuxi, Yunnan, China), Batch No. 20230802; Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) (Guangdong Huankai Microbial Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, Guangdong, China); Freeze-dried powder of Cornus officinalis pulp fermentation broth (laboratory-made); Silibinin capsules (National Medicine Approval No. H20040299, Tianjin Tasly Sentai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China); Edible alcohol (53% v/v, Henan Hanyong Wine Industry Co., Ltd., Jiaozuo, Henan, China), Batch No. 20230103;Alanine Transaminase (ALT) Activity Assay Kit (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); Aspartate Transaminase (AST) Activity Assay Kit (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) Lysis Buffer (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) Loading Buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); Polyvinylidene Difluoride (PVDF) Membrane (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA); Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) Ultra-Sensitive Kit (New Cell & Molecular Biotech Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China); Anti-Keap1 antibody (Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; rabbit monoclonal); Anti-Nrf2 antibody (Sanying Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; rabbit monoclonal); Anti-HO-1 antibody (Sanying Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; rabbit monoclonal); Anti-GPX4 antibody (Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; rabbit monoclonal); Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) rabbit monoclonal antibody (Genesee Scientific Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; goat anti-rabbit); Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China); L-Ascorbic acid standard (Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); HPLC-grade methanol (BCA Reagent Company, Houston, TX 77084, USA); Ultrapure water (laboratory-made); all other reagents were of analytical grade.

Yeast (Angel Yeast Co., Ltd., Yichang, Hubei, China). Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) male ICR mice (body weight 20–22 g) (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) (License No.: SCXK (Yu) 2020-0005; Quality Certificate No.: 410000000000011368).

2.2. Preparation of Fermented Cornus officinalis Fruit Samples

The yeast was activated on a PDA plate, and a single colony was picked and inoculated into a conical flask containing 100 mL of PDB medium. The conical flask was placed in a constant-temperature shaking incubator at 28 °C and cultured in the dark for 3 days at a rotation speed of 120 rpm. A total of 500 g of C. officinalis fruit was mechanically crushed, mixed with 2500 mL of sterile deionized water, and supplemented with 5% (w/v) glucose. The above yeast seed mixture was subsequently inoculated at an inoculation amount of 3%, and fermentation was continued in the dark under the same conditions for 28 days. After fermentation, the supernatant was collected, and the water in the system was removed via rotary evaporation. Finally, freeze-drying was performed to obtain the fermented solid powder of C. officinalis.

2.3. Molecular Networking Analysis

The dried extract was dissolved in chromatographic-grade methanol, and ultrasonic treatment was performed to promote dissolution. The solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane, and the filtrate was transferred to a sample vial for subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis. LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis was carried out via a Dionex UltiMate™ 3000 RSLCnano system coupled with a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

LC-MS/MS analysis of the extract was performed via a UPLC–Q Exactive MS (Thermo Scientific) instrument equipped with a C18 chromatographic column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm). Mobile phase A was an aqueous solution containing 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B was an acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% formic acid. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL/min: isocratic elution with 5% B was used from 0–5 min, followed by linear gradient elution from 5% to 95% B from 5–42 min. Data-dependent acquisition mode was adopted for analysis, with a full scan performed in the mass range of 100–1500 Da, a scan time of 100 ms, and a collision energy gradient set at 35 eV.

RawConverter software (version 2.0.0) was used to convert the MS/MS data files into mzXML format. The data analysis workflow and spectral clustering algorithm of the GNPS platform (http://gnps.ucsd.edu) (accessed on 28 September 2025) were employed. The precursor ion mass tolerance was set to 2.0 Da, and the MS/MS fragment ion tolerance was set to 0.5 Da. A network was constructed by filtering edges with a cosine value greater than 0.7 and a matched peak number greater than 6. The resulting spectral network was visualized via Cytoscape 3.9.1.

2.4. Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.4.1. Prediction and Screening of COF- and ALI-Related Targets

A total of 25 compounds were identified from the yeast-fermented Cornus officinalis (COF) sample via analysis via the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform. The standard simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) structural information of each compound was retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (accessed on 29 September 2025). The Swiss Target Prediction online tool (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch) (accessed on 29 September 2025) was used to predict the potential therapeutic targets of these compounds [23], and the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org) (accessed on 29 September 2025) was employed to standardize the target names.

Moreover, the keywords “alcoholic liver injury” were used to search for disease-related targets associated with alcoholic liver injury (ALI) in the GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) (accessed on 29 September 2025) and OMIM (https://omim.org) (accessed on 29 September 2025) databases. A GeneCards score ≥ 10 was set as the screening threshold, and targets meeting this criterion were included for further analysis. The intersection of targets predicted from the COF bioactive components and ALI-related targets was obtained to identify the common therapeutic targets of COF bioactive components and ALI. The jvenn online tool (https://jvenn.toulouse.inrae.fr/app/example.html) (accessed on 29 September 2025) was used to process the C. officinalis targets and disease-related targets, yielding the common target genes of fermented C. officinalis bioactive components and ALI.

2.4.2. Construction of a Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network and Screening of Core Targets

To explore the potential key common targets of COF and ALI and their interactions, the STRING network platform (https://cn.string-db.org/) (accessed on 29 September 2025) was utilized to construct a PPI network [24]. The protein species was set to Homo sapiens (human), and the minimum required interaction score was set to 0.900 to ensure highly reliable protein–protein interaction relationships. The data were imported into Cytoscape 3.9.1 software to generate a PPI diagram, followed by topological analysis of the PPI network. The visualization of the network diagram was optimized by adjusting the node size, color, and edge thickness, ultimately constructing a high-confidence protein–protein interaction network.

2.4.3. Gene Ontology (GO) Functional Enrichment Analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The Metascape database [25] (https://Metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1) (accessed on 29 September 2025) was used to perform GO functional enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on the core targets. GO enrichment analysis elucidated the biological significance of the core targets from three dimensions: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). During the analysis, the enrichment results were sorted by p value, and the top 10 pathways with the most significant p values were selected for visualization analysis to intuitively display the distribution of core targets in different signaling pathways. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis aimed to identify the signaling pathways significantly enriched by the core targets, thereby revealing the potential biological processes and molecular mechanisms underlying the pharmacological effects of COF.

2.4.4. Molecular Docking

To verify the binding ability and potential biological activity of the interactions between COF bioactive components and key targets, the target proteins of the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 pathway (consistent with those detected via Western blot) were selected for molecular docking analysis between proteins and small molecules. Specifically, the classic crystal structure of Keap1 (PDB ID: 4L7B) was designated as the target, and ligand 1vv from the 4L7B protein was employed for molecular docking, so as to ensure the reliability and comparability of the docking results. The 25 compounds identified from COF via GNPS were chosen as ligands, and their three-dimensional structures (in SDF format) were downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (accessed on 24 December 2025). The protein structures were retrieved from UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) (accessed on 24 December 2025) and obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) (accessed on 24 December 2025). Molecular docking was performed via the CB-Dock2 platform (https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/php/blinddock.php) (accessed on 24 December 2025), which integrates the Curvature Pocket Detection Algorithm (CurPocket); the automatic optimization function of the docking box in this method significantly improves the accuracy of blind docking. The docking results were analyzed and visualized for small molecule–target protein interactions via the PLIP online website (https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/plip-web/plip/index) (accessed on 24 December 2025) [26] and PyMOL software (version 3.1.6.1) to evaluate the degree of binding between receptors and ligands. For the Keap1 target, the binding energies and binding modes of the active components of COF were compared with those of the reference ligand 1vv, so as to evaluate the relative binding affinity and interaction specificity between the receptor and ligands.

2.5. Animal Experimental Verification

2.5.1. Animal Administration and Grouping

Specific pathogen-free (SPF)-grade male ICR mice (20–22 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (License No. SCXK (Yu) 2020-0005; Quality Certificate No. 410000000000011368). The mice were housed in an SPF-grade environment at a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C, a relative humidity of 50 ± 10%, and a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle, with free access to food and sterile water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Inspection Form of Guizhou Medical University (No. 2502554). Prior to the experiment, all mice were acclimatized under standard conditions for 7 days [27].

The mice were randomly divided into 5 groups (n = 12) [28]: the blank control group (Control), model group (Model), positive drug group (SFJ, 54 mg/kg), low-dose fermented C. officinalis group (COF-L, 100 mg/kg), and high-dose fermented C. officinalis group (COF-H, 400 mg/kg) [29]. The control and model groups were intragastrically administered an equal volume of deionized water (10 mL/kg) daily; the SFJ group was intragastrically administered silibinin capsule solution (54 mg/kg) [30]; and the COF-L and COF-H groups were intragastrically administered fermented C. officinalis solution at the corresponding doses. The intragastric volume for all groups was 10 mL/kg, and administration was continued for 14 days. From the 14th day onwards, except for those in the control group, the mice in the other groups were intragastrically administered 53% edible alcohol (12 mL/kg) 6 h after each drug administration for 3 consecutive days to establish an acute alcoholic liver injury (ALI) model. Twelve hours after the last alcohol gavage, blood samples were collected, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and liver tissues were harvested for subsequent analysis.

2.5.2. Determination of the Liver Index

After dissection, the liver tissue was quickly weighed, and the weights were recorded. The liver index was calculated according to the previously established formula [31], as shown in Formula (1):

W = m/M × 100

In Formula (1), W represents the liver index (%); m represents the mass of the mouse liver (g); and M represents the body weight of the mouse (g).

2.5.3. Detection of Serum ALT and AST Levels in Mice

Blood was collected via eyeball enucleation into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes. After standing for 2 h, the blood was centrifuged at 3000 r/min at 4 °C for 15 min to prepare the serum. The supernatant was aliquoted into 3 portions and stored at −80 °C for later use [32]. The levels of AST and ALT in mouse serum were determined according to the kit instructions.

2.5.4. Histopathological Observation

Fresh liver tissues were fixed in 4% (v/v) formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed under a microscope (DS-Fi 2, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) [33].

2.5.5. Western Blot

Liver tissues were rinsed with precooled PBS, and lysis buffer was added at a mass-to-volume ratio of 1:10 for mechanical homogenization. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000× g at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. The BCA method was used to determine the protein concentration. An appropriate amount of protein sample was mixed with 5× reducing loading buffer at a ratio of 4:1, denatured in a boiling water bath for 15 min, and stored at −20 °C for later use. The samples were loaded according to the calculated volume, and SDS–PAGE was performed via a 12% separating gel at a constant voltage of 200 V for approximately 30 min. Electrophoresis was stopped when the bromophenol blue indicator migrated approximately 1 cm from the bottom of the gel. The protein was subsequently transferred to a PVDF membrane at a constant current of 300 mA for 30 min in an ice bath. After membrane transfer, the PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 30 min, followed by the addition of primary antibodies against Nrf2 (1:1000 dilution), Keap1 (1:1000 dilution), HO-1 (1:1000 dilution), GPX4 (1:1000 dilution), and GAPDH (1:1000 dilution) and incubation at 4 °C overnight. After rinsing with TBST, an HRP-labelled secondary antibody (1:5000 dilution) was added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The membrane surface was evenly covered with ECL chemiluminescent reagent; after 1 min of reaction, the excess liquid was removed, and signals were collected via a chemiluminescence imaging system. The gray values of the bands were analyzed via Image Lab software (version 6.0, Bio-Rad Laboratories) [34].

2.5.6. Statistical Analysis

The data were statistically analyzed via IBM SPSS Statistics 27 software; all the quantitative data are presented as the mean ± SDs. Each dataset was subjected to a normality test. One-way ANOVA was used to compare homogeneous groups, and the least significant difference (LSD) test was used for multiple comparisons. GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0) was used for graphing [35].

3. Results

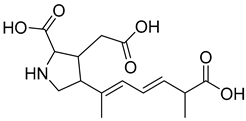

3.1. Investigation of the Chemical Composition of COF Using the Molecular Networking Approach

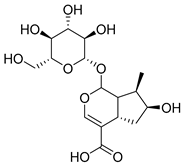

In order to investigate the chemical composition of yeast-fermented Corni Fructus (COF), we analyzed the fermentation supernatant using liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS/MS) in combination with the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform. A molecular network of the extract was successfully constructed, and compound identification was based on high matches between the MS/MS spectra of the detected components and the reference spectra in the GNPS library. The generated network visually illustrated the clustering and relationships among different compounds, facilitating a systematic compositional analysis.

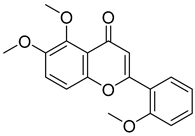

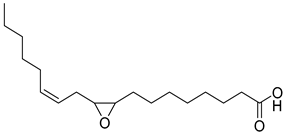

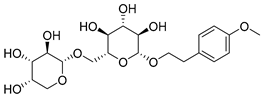

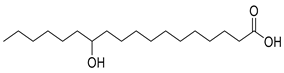

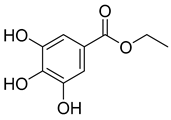

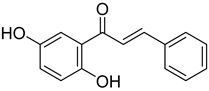

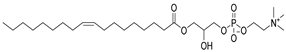

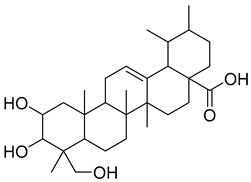

A total of 25 major chemical components were identified (Table 1 and Figure S2), encompassing four categories of compounds: 1 iridoid, 11 shikimic acids and phenylpropanoids, 1 terpenoid, and 12 other compounds. This analysis revealed the diverse chemical profile of COF, laying an important foundation for further investigation into the hepatoprotective effects and underlying mechanisms of yeast-fermented Corni Fructus.

Table 1.

Dereplication from the COF based on GNPS spectral match and molecular network approach.

3.2. Molecular Network Prediction

3.2.1. Prediction of COF Targets and ALI Targets

A total of 2588 targets for the 25 chemical components were obtained from the SwissTargetPrediction database. After removing duplicate data and standardizing gene names via the UniProt database, 825 targets of COF bioactive components were finally collected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bioactive components of COFs and their number of targets.

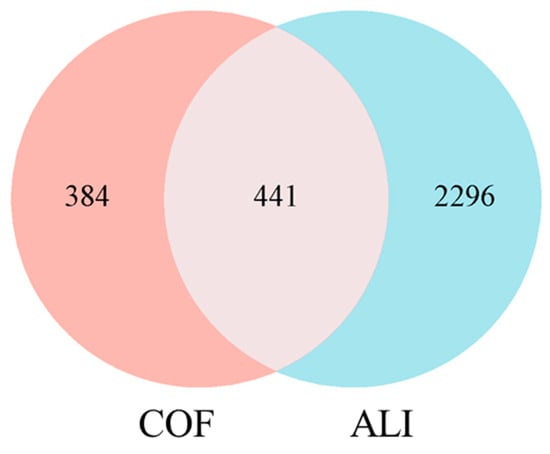

The OMIM and GeneCards databases were searched via the keyword “alcoholic liver injury”. A total of 97 ALI-related disease gene targets were obtained from the OMIM database; for the GeneCards database, the search results were filtered with a “relevance score” ≥ 10, resulting in 2666 ALI-related disease gene targets. The genes obtained from the two databases were merged and deduplicated, and after standardization via the UniProt database, 2737 disease genes were ultimately acquired. The intersection of COF bioactive component targets and ALI disease gene targets was taken, yielding 441 common targets for further analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of the COF and ALI targets.

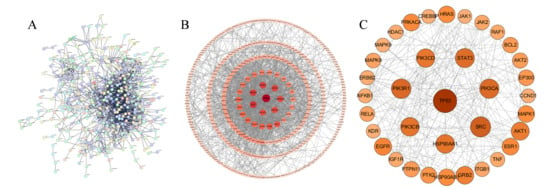

3.2.2. Construction of the PPI Network and Screening of Core Targets

To explore the molecular mechanism of fermented Cornus officinalis (COF) in treating alcoholic liver injury (ALI), the genes intersecting with COF bioactive component genes and ALI-related genes were uploaded to the STRING database to construct a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. The PPI network data constructed via the STRING platform (Figure 2A) were imported into Cytoscape 3.9.1 for visualization. After removing disconnected nodes in the network, the target network contained 373 nodes and 1531 edges (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks. (A) PPI network based on the STRING database; (B) PPI network constructed via Cytoscape 3.9.1; (C) PPI network of common core targets between COFs and ALI. ( Larger node size, darker color, and thicker connecting lines indicate higher importance of the node in the network in (B,C)).

Screening was performed with “Degree” as the key metric, resulting in 36 targets. In the network, a larger node size, darker color, and thicker connections to other nodes indicate greater importance of the node. The top 36 core targets were selected in descending order of degree via the cytoNCA plugin (Figure 2C), including tumor protein 53 (TP53), SRC proto-oncogene, nonreceptor tyrosine kinase (SRC), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1 (HSP90AA1), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). These results suggest that fermented Cornus officinalis may exert anti-ALI effects primarily by regulating these central targets.

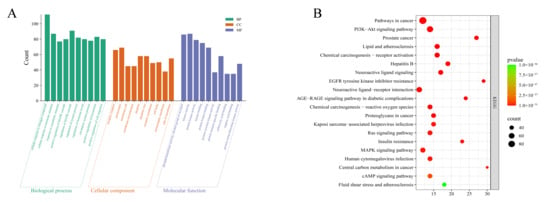

3.2.3. GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analyses

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to identify the functional characteristics of the common genes. The Metascape database was used to conduct GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses on the intersecting genes between Cornus officinalis and alcoholic liver injury (ALI). GO pathway enrichment analysis revealed three main categories: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF).

A total of 3773 GO terms were enriched in the GO enrichment analysis, including 3099 BP terms, 196 CC terms, and 478 MF terms (p < 0.05). In ascending order of p values, the top 10 terms were visualized via an enrichment bubble plot (Figure 3A). The GO enrichment analysis revealed that the relevant targets were involved mainly in biological processes such as the cellular response to nitrogen compounds and hormonal stimuli, the regulation of the MAPK signaling cascade, cell migration, and the regulation of systematic processes. In terms of molecular function, the targets were associated primarily with protein kinase activity and binding; for cellular components, the targets were concentrated in receptor complexes, postsynaptic membranes, and membrane rafts. These findings suggest that these targets are closely related to signal transduction and inflammatory regulation.

Figure 3.

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (A) bar chart of biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) enrichment; (B) bubble chart of KEGG pathway enrichment.

A total of 255 pathways were obtained from the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (Figure 3B), and the targets were significantly enriched in signaling pathways such as the PI3K-Akt, MAPK, and AGE-RAGE pathways—all of which are closely associated with inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Combined with the PPI network diagram, the nodes in the network are closely connected, forming highly connected hub genes centered on TP53, SRC, PIK3CA, STAT3, PIK3R1, and PIK3CB. These findings indicate that these genes play key roles in the entire regulatory network. Among them, TP53, as the central node of the network, has the highest degree of connectivity, suggesting that it plays a core role in apoptosis, the stress response, and inflammatory regulation; PIK3CA/PIK3R1/PIK3CB are important members of the PI3K signaling pathway and regulate cell survival and inflammatory responses; and STAT3 and SRC are involved in the transmission of various inflammatory and immune signals and synergistically regulate the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis together with MAPK, TNF, EGFR, and other molecules.

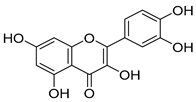

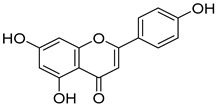

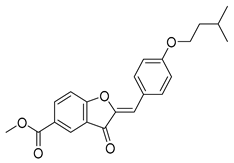

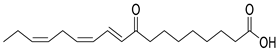

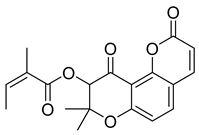

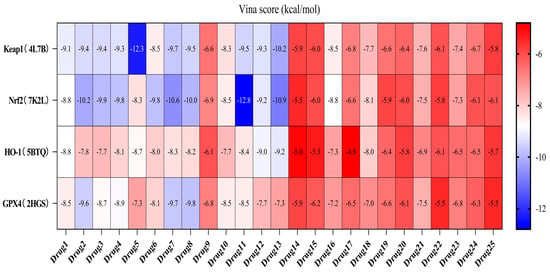

3.3. Molecular Docking and Structural Visualization of Bioactive Components with Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 Targets

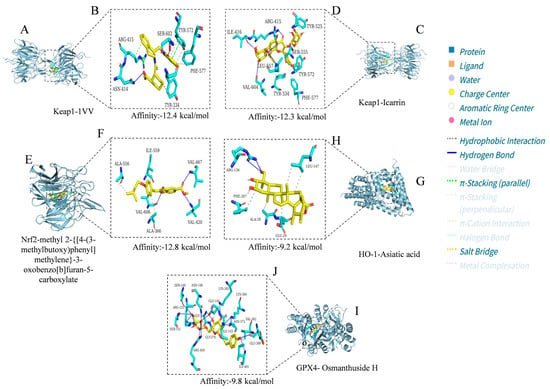

Molecular docking analysis was performed for 25 compounds (including icariin) with the Keap1 (PDB: 4L7B), Nrf2 (PDB: 7K2L), HO-1 (PDB: 5BTQ), and GPX4 (PDB: 2HGS) proteins via the CB-Dock2 database (Figure 4). The classic crystal structure of Keap1 (PDB ID: 4L7B) was selected as the docking receptor, and the endogenous ligand 1vv within this crystal structure was used as the positive control for parallel molecular docking with the active components of Cornus officinalis fermented product (COF) under identical docking parameters and operating conditions, which served as a quality control measure for the parallel docking process. However, only the docking scores of 25 small molecules against the aforementioned target were presented in the heatmap, so as to facilitate the focused analysis of the activity ranking and target preference of the candidate molecules. It is generally accepted that a binding energy lower than −5 kcal/mol indicates that bioactive components can bind effectively to target genes under natural conditions.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of docking scores between COF components and Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4.

Except for the docking value between Drug 17 and HO-1, the docking score heatmap revealed that the binding energies of all the other compounds were lower than −5 kcal/mol, indicating good binding activity. The docking energy of ligand 1vv with Keap1 (4L7B) was −12.4 kcal/mol. Among them, the binding energy of icariin to the Keap1 protein was −12.3 kcal/mol, indicating the strongest binding affinity. Its docking score of −12.4 kcal/mol is close to that of 1vv, indicating that icariin can bind stably to the 4L7B protein and thereby exert its biological effects. The binding energy of methyl 2-{[4-(3-methylbutoxy)phenyl]methylene}-3-oxobenzo[b]furan-5-carboxylate to the Nrf2 protein was −12.8 kcal/mol, the binding energy of Asiatic acid to HO-1 was −9.2 kcal/mol, and the binding energy of osmanthuside H to HO-1 was −9.8 kcal/mol.

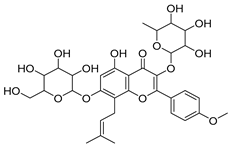

The PLIP online website and PyMOL software were used to analyze the interactions between the compounds with the highest binding energy and the target proteins and to generate interaction diagrams (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Visualization analysis results of docking between icariin, methyl 2-{[4-(3-methylbutoxy) phenyl]methylene}-3-oxobenzo[b]furan-5-carboxylate, Asiatic acid, and osmanthuside H and the Keap1, Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 proteins. (A) 1vv embedded in the binding pocket of key target Keap1; (B) Binding status of 1vv with amino acid residues of 4L7B; (C) Icarrin embedded in the binding pocket of key target Keap1; (D) Binding status of Icarrin with amino acid residues of 4L7B; (E) Methyl 2-{[4-(3-methylbutoxy)phenyl]methylene}-3-oxobenzo[b]furan-5-carboxy late embedded in the binding pocket of key target Nrf2; (F) Binding status of methyl 2-{[4-(3-methylbutoxy) phenyl]methylene}-3-oxobenzo[b]furan-5-carboxylate with amino acid residues of 7K2L; (G) Asiatic acid embedded in the binding pocket of key target HO-1; (H) Binding status of Asiatic acid with amino acid residues of 5BTQ; (I) Osmanthuside H embedded in the binding pocket of key target GPX4; (J) Binding status of osmanthuside H with amino acid residues of 2HGS. The compound structures are displayed as yellow stick models, and the amino acid residues are displayed as blue stick models. Hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and salt bridges are represented by blue solid lines, gray dashed lines, and yellow dashed lines, respectively.

In the Keap1-1vv complex, the ligand stably resides in the protein binding pocket through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, π-stacking (parallel), and salt bridges (Figure 5A). Specifically, 1vv forms tight hydrophobic interactions with hydrophobic residues such as ARG-415, TYR-334, TYR-572, and PHE-557, which helps maintain the ligand’s spatial orientation and binding stability. Meanwhile, it also forms a hydrogen bond network with residues including ASN-414 and SER-602, further enhancing binding specificity and affinity. Additionally, it forms parallel π-stacking with the amino acid residue TYR-572 and a salt bridge with ARG-415 (Figure 5B). Overall, ligand 1vv is stably embedded in the active pocket of Keap1, demonstrating strong binding potential.

In the Keap1–icariin complex, the ligand is stably localized in the protein binding pocket via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds (Figure 5C). Specifically, icariin forms intimate hydrophobic interactions with hydrophobic residues such as TYR-334, PHE-577, TYR-572, and TYR-525, which contributes to maintaining the ligand’s spatial positioning and binding stability. Simultaneously, it establishes a hydrogen bond network with residues including ILE-416, ARG-415, VAL-604, LEU-557, and SER-555, further reinforcing binding specificity and affinity (Figure 5D). Overall, icariin is stably embedded in the active pocket of Keap1, exhibiting robust binding potential. Compared with 1vv, the small molecule icariin can also bind stably to Keap1 and display favorable target-binding characteristics. As reported in the existing literature [36], icariin exerts hepatoprotective effects by regulating hepatic oxidative stress, suppressing inflammation, and inhibiting apoptosis, primarily through targeting Keap1 to activate the Nrf2 pathway. This is consistent with the molecular docking results of the present study, which confirm that icariin can bind to Keap1 in a targeted manner.

In the complex of Nrf2 and methyl 2-{[4-(3-methylbutoxy)phenyl]methylene}-3-oxobenzo[b]furan-5-carboxylate (Figure 5E), the ligand formed hydrophobic interactions with residues such as ALA-556, ALA-366, and ILE-559 and established hydrogen bond connections with VAL-366, VAL-606, and VAL-420 (Figure 5F). This dual interaction mode collectively maintained the stability of the ligand in the binding cavity, suggesting that this compound may enhance its ability to regulate Nrf2 through multisite binding.

In the HO-1–Asiatic acid complex, the carboxyl group and polycyclic structure of the ligand formed obvious hydrophobic interactions with residues such as PHE-207, ALA-28, GLU-29, and LEU-247 while forming a stable hydrogen bond with ARG-136 (Figure 5G,H). This dual interaction mode of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions helps strengthen the interaction between Asiatic acid and HO-1, indicating that Asiatic acid may promote the activation or stabilization of HO-1 through direct binding.

In the GPX4-osmanthuside H complex (Figure 5I), the ligand formed an extensive hydrogen bond network with multiple polar residues, including ILE-401, GLU-399, ARG-450, LYS-364, LYS-305, ASN-146, GLY-369, SER-149, ARG-125, SER-151, and ASN-373. It also formed hydrophobic interactions with VAL-362 and ILE-143 and formed a salt bridge with GLY-370 (Figure 5J). The synergy of multiple noncovalent interactions significantly enhanced the structural stability of the complex, suggesting that osmanthuside H has high binding affinity and potential regulatory activity on GPX4.

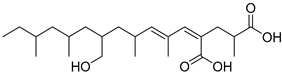

3.4. Results of Animal Experiment Verification

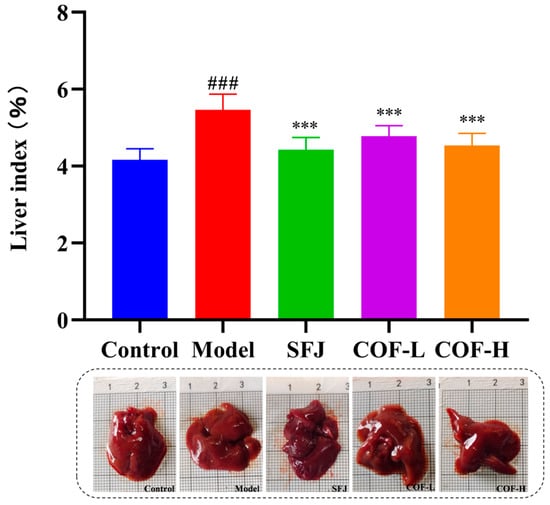

3.4.1. Effects of COF on the Liver Indices of Mice with Alcoholic Liver Injury

The liver index can reflect the degree of liver swelling and injury, and hepatomegaly is a clinically common symptom of alcoholic liver injury [37]. As shown in Figure 6, the liver indices of the model group were significantly greater than those of the control group, indicating that excessive alcohol intake induced hepatomegaly and that the liver injury model was successfully established. Compared with that in the model group, the liver index was significantly lower in both the SFJ group and the COF group, demonstrating that COF could effectively alleviate alcohol-induced hepatomegaly. These results suggest that both SFJ and COF ameliorate alcohol-induced liver injury in mice.

Figure 6.

Statistical analysis of the liver indices among the different groups. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test for post hoc multiple comparisons. Compared with the control group: ### p < 0.001; compared with the model group: *** p < 0.001.

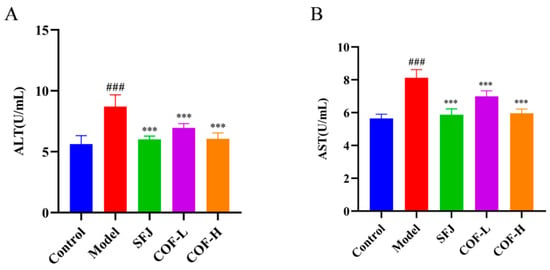

3.4.2. Effects of COF on the Serum AST and ALT Levels

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels in mice are commonly used as biomarkers to evaluate liver function or liver injury [38]. As shown in Figure 7, after treatment with 53% ethanol, the serum ALT and AST levels of the model group were significantly greater than those of the control group (p < 0.001), indicating the successful establishment of the alcoholic liver injury model.

Figure 7.

Effects of COF on serum ALT and AST levels in mice. (A) Serum ALT activity; (B) serum AST activity. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test for post hoc multiple comparisons. Compared with the control group: ### p < 0.001; compared with the model group: *** p < 0.001.

After intervention with different doses of silibinin (SFJ) or COF (COF-L, COF-H), the serum ALT and AST levels in the mice were significantly reduced (p < 0.001), and a dose–response trend was observed. These results demonstrate that COF can significantly improve alcohol-induced abnormalities in liver enzyme indicators and alleviate hepatocyte injury, suggesting that it has potential cytoprotective effects against alcoholic liver injury.

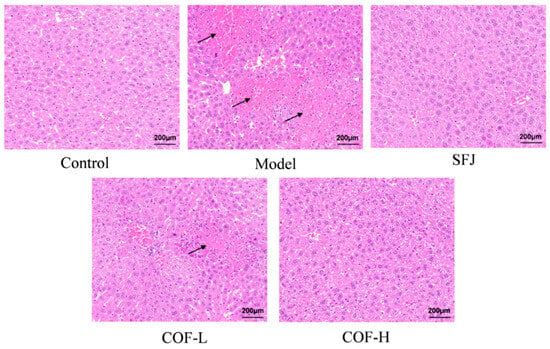

3.4.3. H&E Staining of Mouse Liver Tissues

The results of the H&E staining of liver tissues revealed that the mice in the control group had normal liver tissue structure and intact hepatic lobule morphology, with no obvious hepatocyte degeneration or necrosis (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Histological analysis of liver tissues via H&E staining (scale bar: 200 µm).

Compared with the control group, the model group presented a disordered arrangement of hepatocytes, widened intercellular spaces, many necrotic foci, and inflammatory cell infiltration (indicated by black arrows); some hepatocytes presented vacuolar degeneration, nuclear fragmentation, and karyolysis.

In contrast to that in the model group, liver tissue damage was improved to varying degrees in all the drug-treated groups. Specifically, in the SFJ group and COF-H group, hepatocytes were arranged relatively tightly, inflammatory cell infiltration was significantly reduced, and a small number of tiny vacuoles were observed in the cytoplasm. In the COF-L group, a small amount of inflammatory cell infiltration was still observed, and some hepatocytes retained nuclear fragmentation and karyolysis with slightly irregular cell morphology; no other significant abnormalities were found.

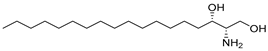

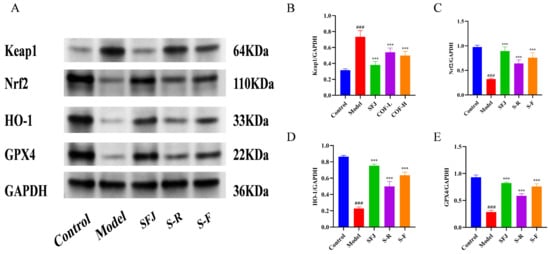

3.4.4. Detection of Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, and GPX4 Protein Expression by Western Blot

The results of the quantitative analysis of liver proteins via Western blotting revealed that COF (fermented Cornus officinalis) regulates oxidative damage by activating the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway (Figure 9). Compared with that in the control group, the expression of Keap1 in the model group was significantly greater, whereas the expression of Nrf2 was significantly lower—these findings suggest that Nrf2 dissociated from Keap1, thereby activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Moreover, the expression of Nrf2 downstream proteins (HO-1 and GPX4) was also significantly reduced in the model group.

Figure 9.

(A) Expression of Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, and GPX4 proteins. (B–E) Quantification of relative protein expression via densitometric analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test for post hoc multiple comparisons. Compared with the control group: ### p < 0.001; compared with the model group: *** p < 0.001.

Notably, COF intervention significantly reversed the above-mentioned changes in protein expression: it inhibited Keap1 expression and promoted the expression of Nrf2 and its downstream proteins in a dose-dependent manner. These findings indicate that the administration of edible alcohol to mice significantly aggravated liver oxidative stress and inhibited the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway, thereby causing oxidative damage to the organism. In contrast, COF treatment activated the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway, promoted the expression of antioxidant enzymes, and alleviated liver oxidative damage.

In conclusion, COF has an ameliorative effect on acute alcoholic liver injury, and its mechanism may be related to the regulation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway, as well as the inhibition of ethanol-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory damage in liver tissue—thus playing a protective role against acute alcoholic liver injury in mice.

4. Discussion

The prevention and treatment of alcoholic liver injury have long been a research focus in the field of public health, with its core pathological mechanism closely associated with oxidative stress imbalance [39,40,41]. In this study, an integrated strategy combining UPLC-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)), GNPS-based component characterization, network pharmacology prediction, and animal experimental verification was employed to systematically clarify the effect and molecular mechanism of yeast-fermented Cornus officinalis (COF) in improving alcoholic liver injury, providing multidimensional scientific evidence for its development as a functional food or hepatoprotective drug.

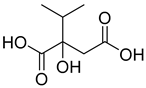

Fermentation transformation of plant-derived natural products is an effective approach to increase their bioactivity. In this study, UPLC-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) combined with GNPS molecular networking technology identified 25 bioactive components from COFs, including flavonoids (quercetin, kaempferol, and icariin), triterpenic acids (Asiatic acid), iridoid glycosides (loganic acid), and phenolic acids (ethyl gallate). Most of these components are metabolites or active forms of the original C. officinalis components after yeast fermentation. Compared with those in unfermented C. officinalis, the conversion of glycoside components to aglycones in fermented products may increase their bioavailability and target-binding ability [42]. Among these components, icariin [36] and Asiatic acid have been confirmed to possess definite hepatoprotective activity [43], whereas flavonoids such as quercetin and kaempferol play key roles in anti-inflammatory and antioxidative stress [44], suggesting that the hepatoprotective effect of COFs may originate from the synergistic action of multiple bioactive components.

As a core tool for deciphering the multicomponent and multitarget mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicines, network pharmacology was used in this study to construct a “component–target–disease” network. A total of 441 common targets between COFs and alcoholic liver injury were screened, and 36 core targets (including TP53, SRC, and PIK3CA) were further identified. GO functional enrichment analysis revealed that these core targets are involved mainly in biological processes such as the cellular response to nitrogen compound stimulation and the regulation of the MAPK signaling cascade, with molecular functions concentrated in protein kinase activity and binding, indicating that COF may exert its effects by regulating signal transduction and inflammatory response networks. KEGG pathway enrichment revealed that the core targets are significantly enriched in signaling pathways such as the PI3K–Akt, MAPK, and AGE-RAGE pathways, all of which are closely related to the regulation of oxidative stress, the inflammatory response, and apoptosis in alcoholic liver injury [45,46,47]. In particular, the Keap1–Nrf2 signaling pathway, as the core pathway of the body’s antioxidant defense, has related targets showing high connectivity in the network, providing a clear direction for subsequent mechanism verification [48].

Molecular docking technology provides an intuitive basis for predicting the interactions between bioactive components and target proteins [49]. In this study, docking analysis was performed on key proteins of the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 pathway. The results revealed that with the exception of Drug 17 and HO-1, the binding energies of all the other components in the COFs with the target proteins were lower than −5 kcal/mol, indicating good binding activity. Among them, the binding energy of icariin with Keap1 reached −10.0 kcal/mol, and it stably bound to the active pocket of Keap1 through hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding networks; the binding energy of methyl 2-{[4-(3-methylbutoxy)phenyl]methylene}-3-oxobenzo[b]furan-5-carboxylate with Nrf2 was −12.8 kcal/mol, and it enhances binding stability through a dual mode of hydrophobic interaction and hydrogen bonding; Asiatic acid with HO-1 and osmanthuside H with GPX4 also forms stable interaction complexes. These results confirm that the bioactive components in COFs can directly bind to key proteins of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway, providing a molecular basis for its regulation of this pathway.

The results of animal experiments further verified the hepatoprotective effect and molecular mechanism of COF. Compared with the model group, the COF intervention group presented a significantly lower liver index and lower serum activities of ALT and AST, suggesting that it can alleviate alcohol-induced hepatomegaly and hepatocyte injury. H&E staining of liver tissue revealed that COF improved the disordered arrangement of hepatocytes and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and vacuolar degeneration, further confirming its structural protective effect on liver tissue. The Western blot results demonstrated that after alcohol exposure, the expression of Keap1 in mouse liver tissue increased, whereas the expression of Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 decreased; however, COF intervention significantly reversed these changes. By inhibiting Keap1 expression, promoting Nrf2 nuclear translocation, and increasing the expression of downstream antioxidant enzymes (HO-1 and GPX4), COF enhances the liver’s antioxidant capacity and alleviates oxidative stress damage [50,51]. This finding is consistent with the results of network pharmacology prediction and molecular docking, clarifying the core mechanism by which COF improves alcoholic liver injury through regulating the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 signaling pathway.

The innovation of this study lies in the integration of metabolomics, network pharmacology, and in vivo experiments to systematically analyze the hepatoprotective effect and mechanism of yeast fermentation in C. officinalis, confirming the advantage of fermentation technology in enhancing the bioactivity of C. officinalis. These research results not only provide a scientific basis for the development of COFs as functional foods for the prevention and treatment of alcoholic liver injury but also offer a feasible technical paradigm for fermentation transformation and mechanistic research on medicinal plants [52]. However, this study still has certain limitations: first, the single bioactive component that plays a core role in COFs has not been identified, and subsequent studies need to verify the activity of key components through separation, purification, and in vitro experiments; second, the animal experiments only used an acute alcoholic liver injury model, and the preventive and therapeutic effects of COFs on chronic alcoholic liver disease need further verification; finally, the cross-regulatory relationships between the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway and other signaling pathways (such as the PI3K–Akt and MAPK pathways) have not been fully elucidated, and further in vitro cell experiments are needed. Future research can focus on the above directions to provide more comprehensive theoretical support for the development and application of COFs.

5. Conclusions

In this study, UPLC-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) combined with GNPS technology was successfully used to identify 25 bioactive components from yeast-fermented Cornus officinalis (COF), including flavonoids, triterpenic acids, iridoid glycosides, and phenolic acids. This study clarified the effects of fermentation on the transformation and enrichment of the bioactive components of C. officinalis. A “component–target–disease” interaction network was constructed on the basis of network pharmacology. A total of 441 common therapeutic targets between COF and alcoholic liver injury (ALI), as well as 36 core targets (including TP53, SRC, and PIK3CA), were screened out. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses revealed that the core targets are involved mainly in oxidative stress regulation, the inflammatory response, and cellular signal transduction processes and are significantly enriched in pathways closely related to the pathological mechanism of ALI (e.g., the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway). Molecular docking verification revealed that bioactive components in COFs, such as icariin and Asiatic acid, can form stable bonds with key proteins (Keap1, Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4) with binding energies of all <−5 kcal/mol, providing a molecular basis for pathway regulation. Animal experiments further confirmed that COF can significantly reduce the liver indices of mice with alcohol-induced liver injury, decrease the serum activities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and ameliorate liver tissue pathological damage (reducing hepatocyte necrosis, inflammatory infiltration, and vacuolar degeneration). Mechanistically, COF activates the Keap1–Nrf2–HO-1/GPX4 signaling pathway to alleviate liver oxidative stress damage by inhibiting Keap1 protein expression, promoting Nrf2 nuclear translocation, and increasing the expression of downstream antioxidant enzymes (HO-1 and GPX4). This study systematically elucidates the material basis and molecular mechanism by which yeast-fermented C. officinalis improves alcoholic liver injury, providing sufficient scientific evidence for its development as a functional food or candidate drug for the prevention and treatment of alcoholic liver injury. This study also offers a reference research paradigm for enhancing the efficacy of medicinal plants through fermentation and multidimensional mechanism analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010028/s1. Figure S1. Molecular network and annotation of compounds 1–25. Figure S2. Original imprinted image of the GAPDH protein. Figure S3. Original imprinted image of the Keap1 protein. Figure S4. Original imprinted image of the Nrf 2 protein. Figure S5. Original imprinted image of the GPX 4 protein. Figure S6. Original imprinted image of the HO-1 protein.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.T. and L.L. (Liangqun Li); Methodology, X.T., L.L. (Liangqun Li), L.L. (Lan Luo), Y.W., J.Y. and X.Y.; Formal analysis, X.T., H.L., J.Z., M.P. and Q.L.; Investigation, X.T.; Writing—original draft, X.T.; Writing—review and editing, H.L. and L.L. (Liangqun Li); Supervision, L.L. (Liangqun Li); Project administration, L.L. (Liangqun Li); Funding acquisition, L.L. (Liangqun Li) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82460764), the Guizhou Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. QKHZC [2025] General 055), and the Young Scientific and Technological Talents Growth Project of Guizhou Medical University (Grant No. 22QNRC14).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Inspection Form of Guizhou Medical University (protocol code 2502554) on 25 March 2025..

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALI | Alcoholic Liver Injury |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| GPX4 | Glutathione Peroxidase 4 |

| AREs | Antioxidant Response Elements |

| CO | Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc. |

| COF | Cornus officinalis Fermented by Yeast |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| GSH | Glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| PPARα | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Alpha |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| GNPS | Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| PDB | Potato Dextrose Broth |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| BP | Biological Process |

| CC | Cellular Component |

| MF | Molecular Function |

| SFJ | Silibinin Capsules |

References

- Maccioni, L.; Gao, B.; Leclercq, S.; Pirlot, B.; Horsmans, Y.; De Timary, P.; Leclercq, I.; Fouts, D.; Schnabl, B.; Stärkel, P. Intestinal permeability, microbial translocation, changes in duodenal and fecal microbiota, and their associations with alcoholic liver disease progression in humans. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1782157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Min, T.; Bai, Y.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Oxidative stress in alcoholic liver disease, focusing on proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Tian, T.; Li, X.; Hao, P.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, T.; Chen, P.; Cheng, Y.; Xue, F. Dexmedetomidine postconditioning attenuates myocardial ischemia/ reperfusion injury by activating the Nrf2/Sirt3/SOD2 signaling pathway in the rats. Redox Rep. 2023, 28, 2158526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Hu, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, K.; Luo, L.; Zeng, L. Hawk Tea Flavonoids as Natural Hepatoprotective Agents Alleviate Acute Liver Damage by Reshaping the Intestinal Microbiota and Modulating the Nrf2 and NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Tan, M.; He, Y.; Pan, Y.; Fan, X.; Ye, L.; Liu, L.; Fu, L. The Ethanolic Extract of Lindera aggregata Modulates Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Alleviates Ethanol-Induced Acute Liver Inflammation and Oxidative Stress SIRT1/ Nrf2/NF-κB Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 6256450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Liu, W.; Feng, L.; Zou, J.; Shi, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Huo, E.; Luan, F.; Zhang, M. Cornus officinalis Sieb.: An updated review on the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacokinetics. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 353, 120365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.A.; Sharief, N.H.; Mohamed, Y.S. Hepatoprotective Activity of Some Medicinal Plants in Sudan. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2019, 2019, 2196315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Yue, N.; Ye, D.; Zhu, Y.; Tao, R.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, A.; et al. Antioxidative and Energy Metabolism-Improving Effects of Maca Polysaccharide on Cyclophosphamide-Induced Hepatotoxicity Mice via Metabolomic Analysis and Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zheng, L.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Qu, Y.; Gao, M.; Cui, X.; Yang, Y. A Novel Acidic Polysaccharide from the Residue of Panax notoginseng and Its Hepatoprotective Effect on Alcoholic Liver Damage in Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.Y.; Park, S.M.; Ko, H.L.; Lee, J.R.; Park, C.A.; Byun, S.H.; Ku, S.K.; Cho, I.J.; Kim, S.C. Epimedium koreanum Ameliorates Oxidative Stress-Mediated Liver Injury by Activating Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Man, S.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Gao, W. Functional factors, nutritional value and development strategies of Cornus: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kang, H.; Peng, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, D.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, C. Therapeutic mechanism of Cornus Officinalis Fruit Coreon on ALI by AKT/Nrf2 pathway and gut microbiota. Phytomedicine 2024, 130, 155736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Abdu, H.I.; Khan, M.R.U.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Pei, J.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. A comprehensive review of Cornus officinalis: Health benefits, phytochemistry, and pharmacological effects for functional drug and food development. Front. Nutr. 2024, 10, 1309963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Xiao, M.; Li, Y.; Chitrakar, B.; Sheng, Q.; Zhao, W. Ursolic Acid Ameliorates Alcoholic Liver Injury through Attenuating Oxidative Stress-Mediated Ferroptosis and Modulating Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 21181–21192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, J.; Ling, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, X.; et al. Application of fermented Chinese herbal medicines in food and medicine field: From an antioxidant perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 148, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourou, M.; Economou, C.N.; Aggeli, L.; Janák, M.; Valdés, G.; Elezi, N.; Kakavas, D.; Papageorgiou, T.; Lianou, A.; Vayenas, D.V.; et al. Bioconversion of pomegranate residues into biofuels and bioactive lipids. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhao, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Akanda, M.R.; Cho, J.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Choi, Y.-J.; Park, B.-Y. Neuroprotective Effects of Cornus officinalis on Stress-Induced Hippocampal Deficits in Rats and H2O2-Induced Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Dong, M.; Liu, J.; Guo, N.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Y. Fermentation: Improvement of pharmacological effects and applications of botanical drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1430238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Shi, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H. Exploration of the Effect and Potential Mechanism of Echinacoside Against Endometrial Cancer Based on Network Pharmacology and in vitro Experimental Verification. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 1847–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Jiang, S.; Liu, X.; Tang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Qu, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Inflammatory Response and Oxidative Stress as Mechanism of Reducing Hyperuricemia of Gardenia jasminoides-Poria cocos with Network Pharmacology. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8031319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Ji, S.; Peng, L.; Sheng, J.; Wang, J. Integrating Strategy of Network Pharmacology, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and Experimental Verification to Investigate the Potential Mechanism of Gastrodia elata Against Alcoholic Liver Injury. Foods 2025, 14, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Zoete, V. Testing the predictive power of reverse screening to infer drug targets, with the help of machine learning. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schake, P.; Bolz, S.N.; Linnemann, K.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2025: Introducing protein–protein interactions to the protein–ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y. Treatment of Diabetes Nephropathy in Mice by Germinating Seeds of Euryale ferox through Improving Oxidative Stress. Foods 2023, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, B. Protective Effect of Polysaccharide from Maca (Lepidium meyenii) on Hep-G2 Cells and Alcoholic Liver Oxidative Injury in Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Song, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hu, J.; Meng, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zheng, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, Z. Cornus officinalis extract ameliorates fructose-induced hepatic steatosis in mice by sustaining the homeostasis of intestinal microecology and lipid metabolism. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Guo, X.; Niu, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, L.; Yang, L.; et al. Mao Jian Black Tea Ethanol Extract Alleviates Alcoholic Liver Injury in Mice via Regulation of the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Foods 2025, 14, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Hao, K.; Chen, X.; Wu, E.; Nie, D.; Zhang, G.; Si, H. Broussonetia papyrifera polysaccharide alleviated acetaminophen-induced liver injury by regulating the intestinal flora. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, K.; Watanabe, S.; Miura, S.; Ohtsubo, A.; Shoji, S.; Nozaki, K.; Tanaka, T.; Saida, Y.; Kondo, R.; Hokari, S.; et al. Prognostic significance of procalcitonin in small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Song, S. Isoflurane upregulates microRNA-9-3p to protect rats from hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibiting fibronectin type III domain containing 3B. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kong, J. Effect of aerobic exercise on acquired gefitinib resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; et al. Gut microbiota-derived ursodeoxycholic acid from neonatal dairy calves improves intestinal homeostasis and colitis to attenuate extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infection. Microbiome 2022, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, C.; Hu, H.; Yin, S. Liver Protecting Effects and Molecular Mechanisms of Icariin and Its Metabolites. Phytochemistry 2023, 215, 113841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C.; Qian, H.; Williams, S.N.; Sun, Z.; Peng, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, F.; et al. Persistent mTORC1 activation due to loss of liver tuberous sclerosis complex 1 promotes liver injury in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2023, 78, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Feng, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Xiu, G.; Xu, J.; Ning, K.; Ling, B.; Fu, Q.; Xu, J. ADSCs-derived exosomes ameliorate hepatic fibrosis by suppressing stellate cell activation and remodeling hepatocellular glutamine synthetase- mediated glutamine and ammonia homeostasis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, X.; Xu, J.; Qin, L.-Q. Lactoferrin prevents chronic alcoholic injury by regulating redox balance and lipid metabolism in female C57BL/6J mice. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Liu, B.; Tian, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Cai, D.; Sun, J.; Bai, W.; Jin, Y. Exposure to bisphenol A caused hepatoxicity and intestinal flora disorder in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, A.; Gali, S.; Sharma, S.; Kacew, S.; Yoon, S.; Jeong, H.G.; Kwak, J.H.; Kim, H.S. Dendropanoxide alleviates thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis via inhibition of ROS production and inflammation in BALB/C mice. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Liu, X.; Dias, A.C.P.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C. A study on the identification, quantification, and biological activity of compounds from Cornus officinalis before and after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and simulated colonic fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 98, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Ma, Y.; Ding, M.; Gao, F.; Yu, K.; Wang, S.; Qu, Y.; Hua, H.; Li, D. Asiatic acid and its derivatives: Pharmacological insights and applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 289, 117429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Ho, C.-T.; Bai, N. New utilization of Fraxinus mandshurica leaves: As a safe and promising natural antioxidant. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 20470–20482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, H.; Su, F.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator prevents ischemia/reperfusion induced intestinal apoptosis via inhibiting PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, R.; Sun, Y.; Liu, D.; Lin, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Lv, L.; Tian, X.; et al. circ-CBFB upregulates p66Shc to perturb mitochondrial dynamics in APAP-induced liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, W.; Song, D.; Yan, Y.; Yang, M.; Sun, Y. A potential role for mitochondrial DNA in the activation of oxidative stress and inflammation in liver disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5835910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Huo, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. Discovery of therapeutic candidates for diabetic retinopathy based on molecular switch analysis: Application of a systematic process. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3412032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, S. Network pharmacology and molecular docking study on the active ingredients of qidengmingmu capsule for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Huang, F.; Zhong, S.; Ding, R.; Su, J.; Li, X. Astaxanthin attenuates ferroptosis via Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Life Sci. 2022, 311, 121091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, R.; Sun, G.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, X. Protective effects of total flavonoids from Clinopodium chinense (Benth.) O. Ktze on myocardial injury in vivo and in vitro via regulation of Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Phytomedicine 2018, 40, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Lai, M.; Xu, C.; He, S.; Dong, L.; Huang, F.; Zhang, R.; Young, D.J.; Liu, H.; Su, D. Novel catabolic pathway of quercetin-3-O-rutinose-7 -O-α-L-rhamnoside by Lactobacillus plantarum GDMCC 1.140: The direct fission of C-ring. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 849439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.