The Effects of a Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacterial Inoculant Containing Lentilactobacillus hilgardii and Lentilactobacillus buchneri with or Without Chitinases on the Ensiling, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Whole-Crop Corn Silages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Forage, Treatments, and Ensiling

2.2. Preparation of Whole-Crop Corn Silage in Minisilos

2.3. Aerobic Stability

2.4. In Vitro Experiment

2.5. In Vitro Incubations and Measurements

2.6. Microbial Analyses of Corn Silage

2.7. Chemical Analysis

2.8. Calculation and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

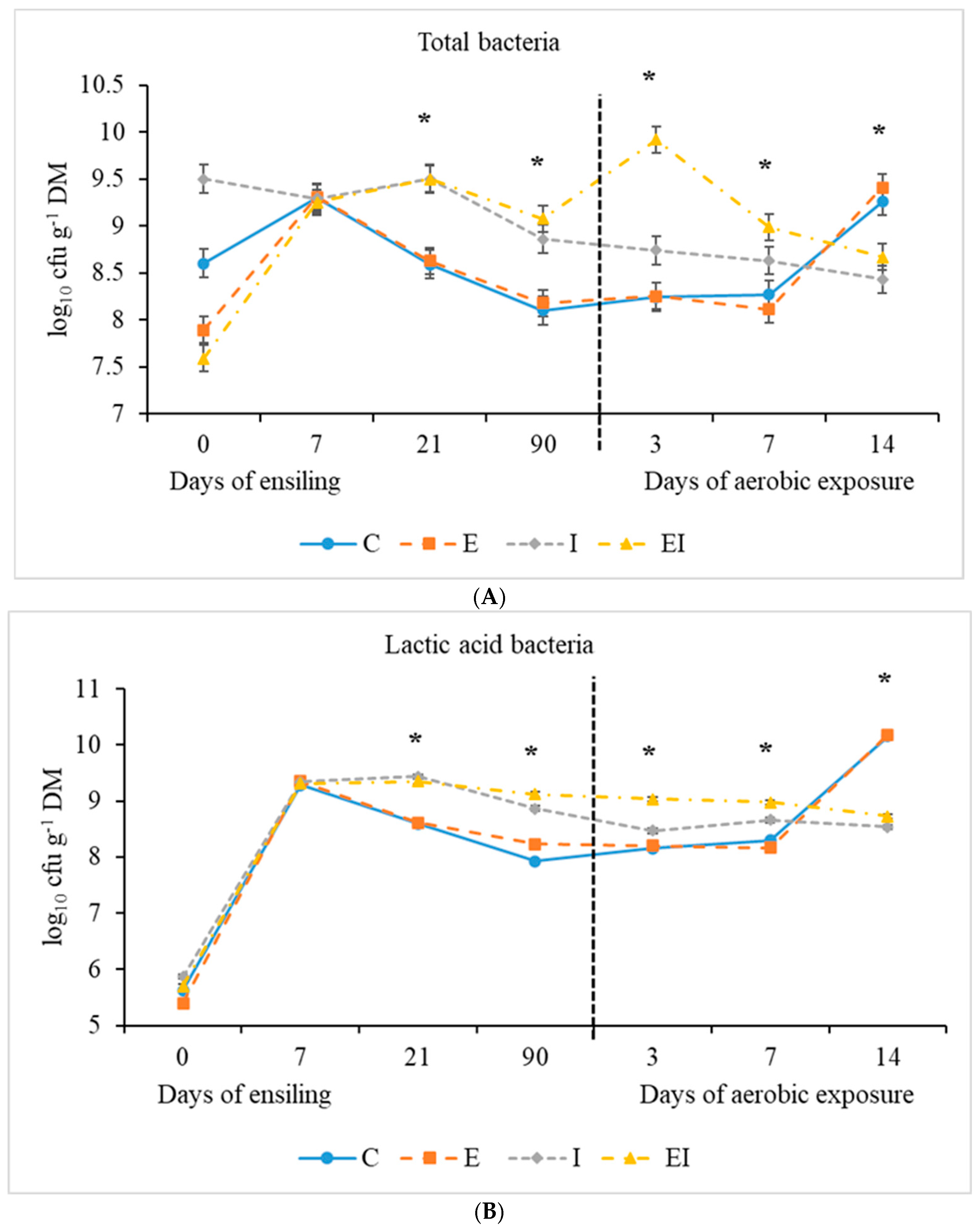

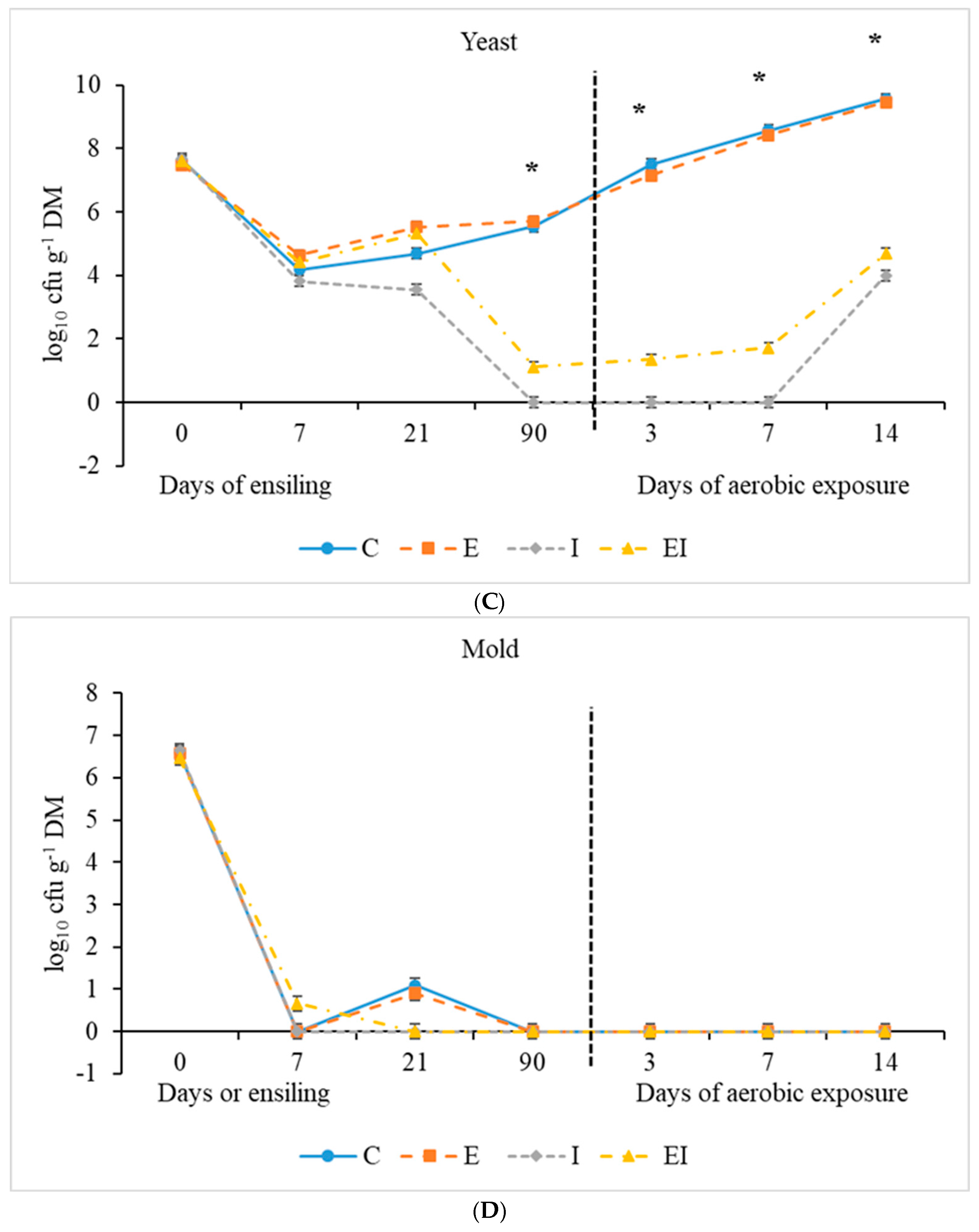

3.1. Fermentation Characteristics During Ensiling and Aerobic Exposure

3.2. In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Bacterial Inoculant and Chitinase on Ensiling Characteristics

4.2. Effects of Bacterial Inoculant and Chitinase on Aerobic Stability of Whole-Crop Corn Silages

4.3. Effects of Bacterial Inoculant and Chitinase on In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Silage

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erdman, R.A.; Piperova, L.S.; Kohn, R.A. Corn silage versus corn silage:alfalfa hay mixtures for dairy cows: Effects of dietary potassium, calcium, and cation-anion difference. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5105–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donna, M.A.; Roy, N.; Lee, C.; Lehmkuhler, J. Practical Corn Silage Harvest and Storage Guide for Cattle Producers. University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service. 2023. Available online: https://publications.mgcafe.uky.edu/sites/publications.ca.uky.edu/files/ID275.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Addah, W.; Baah, J.; Okine, E.K.; Owens, F.N.; McAllister, T.A. Effects of chop-length and ferulic acid esterase producing inoculant on fermentation and aerobic stability of barley silage, and growth performance of finishing feedlot steers. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 197, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, R.E.; Nadeau, E.M.G.; McAllister, T.A.; Contreras-Govea, F.E.; Santos, M.C.; Kung, L., Jr. Silage review: Recent advances and future uses of silage additives. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3980–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntillo, M.; Peralta, G.H.; Bürgi, M.D.M.; Huber, P.; Gaggiotti, M.; Binetti, A.G.; Vinderola, G. Meta-profiling of the bacterial community in sorghum silages inoculated with lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2375–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.; Niu, H.; Andrada, E.; Yang, H.-E.; Chevaux, E.; Drouin, P.; McAllister, T.A.; Wang, Y. Effects of inoculation of corn silage with Lactobacillus hilgardii and Lactobacillus buchneri on silage quality, aerobic stability, nutrient digestibility, and growth performance of growing beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, Skaa267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, F.; Elferink, S.J.; Spoelstra, S.F. Anaerobic lactic acid degradation during ensilage of whole crop maize inoculated with Lactobacillus buchneri inhibits yeast growth and improves aerobic stability. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 87, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, P.; Tremblay, J.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F. Dynamic succession of microbiota during ensiling of whole plant corn following inoculation with Lactobacillus buchneri and Lactobacillus hilgardii alone or in combination. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, M.; Mayrhuber, E.; Danner, H.; Braun, R. The role of Lactobacillus buchneri in forage preservation. Trends Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killerby, M.A.; Almeida, S.T.R.; Hollandsworth, R.; Guimaraes, B.C.; Leon-Tinoco, A.; Perkins, L.B.; Henry, D.; Schwartz, T.J.; Romero, J.J. Effect of chemical and biological preservatives and ensiling stage on the dry matter loss, nutritional value, microbial counts, and ruminal in vitro gas production kinetics of wet brewer’s grain silage. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filya, I.; Sucu, E.; Karabulut, A. The effect of Lactobacillus buchneri on the fermentation, aerobic stability and ruminal degradability of maize silage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmit, D.H.; Kung, L., Jr. A meta-analysis of the effects of Lactobacillus buchneri on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn and grass and small-grain silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4005–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriola, K.G.; Oliveira, A.S.; Jiang, Y.; Kim, D.; Silva, H.M.; Kim, S.C.; Amaro, F.X.; Ogunade, I.M.; Sultana, H.; Pech Cervantes, A.A.; et al. Meta-analysis of effects of inoculation with Lactobacillus buchneri, with or without other bacteria, on silage fermentation, aerobic stability, and performance of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7653–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Teng, K.; Cao, Y.; Shi, W.; Xuan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, J. Effects of Lactobacillus hilgardii 60TS-2, with or without homofermentative Lactobacillus plantarum B90, on the aerobic stability, fermentation quality and microbial community dynamics in sugarcane top silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, É.B.; Costa, D.M.; Santos, E.M.; Moyer, K.; Hellings, E.; Kung, L., Jr. The effects of Lactobacillus hilgardii 4785 and Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 on the microbiome, fermentation, and aerobic stability of corn silage ensiled for various times. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10678–10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, É.B.; Smith, M.L.; Savage, R.M.; Polukis, S.A.; Drouin, P.; Kung, L., Jr. Effects of Lactobacillus hilgardii 4785 and Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 on the bacterial community, fermentation and aerobic stability of high-moisture corn silage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.; Yang, H.-E.; Redman, A.-A.; Chevaux, E.; Drouin, P.; McAllister, T.A.; Wang, Y. Effects of a mixture of Lentilactobacillus hilgardii, Lentilactobacillus buchneri, Pediococcus pentosaceus and fibrolytic enzymes on silage fermentation, aerobic stability and performance of growing beef cattle. Tans. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B.F.; Ávila, C.L.S.; Pinto, J.C.; Neri, J.; Schwan, R.F. Microbiological and chemical profile of sugar cane silage fermentation inoculated with wild strains of lactic acid bacteria. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 195, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, F.; Piano, S.; Tabacco, E.; Borreani, G. Effects of conservation period and Lactobacillus hilgardii inoculum on the fermentation profile and aerobic stability of whole corn and sorghum silages. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2530–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoster, F.; Schmitz, J.E.; Daniel, R. Enrichment of chitinolytic microorganisms: Isolation and characterization of a chitinase exhibiting antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi from a novel Streptomyces strain. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 66, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeleye, A.; Normi, Y.M. Chitinase: Diversity, limitations, and trends in engineering for suitable applications. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR2018032300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, T.M.; de Oliveira, T.B.; Scarcella, A.S.A.; Polizeli, M.L.T.M.; Guazzaroni, M.E. Perspectives on expanding the repertoire of novel microbial chitinases for biological control. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3284–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpure, A.; Choudhary, B.; Gupta, R.K. Chitinases: In agriculture and human healthcare. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014, 34, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, B.; Yang, S.H. Microbial chitinases: Properties, current state and biotechnological applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozome, D.; Uechi, K.; Taira, T.; Fukada, H.; Kubota, T.; Ishikawa, K. Structural analysis and construction of a thermostable antifungal chitinase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0065222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Duniere, L.; Lynch, J.P.; Chevaux, E.; McAllister, T.A.; Baah, J.; Wang, Y. Application of Pediococcus pentosaceus, Pichia anomala, and chitinase to high moisture alfalfa hay at baling: Effects on ruminal digestibility. In Proceedings of the ASAS Joint Annual Meeting 2015, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–12 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Chevaux, E.; McAllister, T.; Baah, J.; Drouin, P.; Wang, Y. Impact of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Pichia anomala in combination with chitinase on the preservation of high-moisture alfalfa hay. Grass Forage Sci. 2018, 73, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.; Jin, L.; Chevaux, E.; McAllister, T.A.; Wang, Y. Impact of inoculation with Pediococcus pentosaceus in combination with chitinase on bale core temperature, nutrient composition, microbial ecology, and ruminal digestion of high-moisture alfalfa hay. Fermentation 2024, 10, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP); Bampidis, V.; Azimonti, G.; Bastos, M.L.; Christensen, H.; Dusemund, B.; Fašmon Durjava, M.; Kouba, M.; López-Alonso, M.; López Puente, S.; et al. Safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of Propionibacterium freudenreichii DSM 33189 and Lentilactobacillus buchneri (formerly Lactobacillus buchneri) DSM 12856 for all animal species (Lactosan GmbH & Co.KG.). EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma-Aldrich, 2025. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/US/en/product/sigma/c6137 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Nair, J.; Xu, S.; Smiley, B.; Yang, H.-E.; McAllister, T.A.; Wang, Y. Effects of inoculation of corn silage with Lactobacillus spp. or Saccharomyces cerevisiae alone or in combination on silage fermentation characteristics, nutrient digestibility, and growth performance of growing beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 4974–4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, R.S.; Schmidt, R.J.; Whitlow, L.W.; Kung, L., Jr. Effect of physical damage to ears of corn before harvest and treatment with various additives on the concentration of mycotoxins, silage fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 8th revised ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC). CCAC Guidelines on: The Care and Use of Farm Animals in Research, Teaching, and Testing; CCAC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009.

- Menke, K.H.; Raab, L.; Salewski, A.; Steingass, H.; Fritz, D.; Schneider, W. The estimation of the digestibility and metabolizable energy content of ruminant feeding stuffs from the gas production when they are incubated with rumen liquor in vitro. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 93, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addah, W.; Baah, J.; Groenewegen, P.; Okine, E.K.; McAllister, T.A. Comparison of the fermentation characteristics, aerobic stability and nutritive value of barley and corn silages ensiled with or without a mixed bacterial inoculant. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 91, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1944, 153, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, H.; Cheng, K.-J.; Costerton, J.W. Interactions between Treponema bryantii and cellulolytic bacteria in the in vitro degradation of straw cellulose. Can. J. Microbiol. 1987, 33, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, G.A.; Kang, J.H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000.

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysac-charides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Saldana, G.E.; Huber, J.T.; Poore, M.H. Dry matter, crude protein, and starch degradability of five cereal grains. J. Dairy Sci. 1990, 73, 2386–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addah, W.; Baah, J.; McAllister, T.A. Effects of an exogenous enzyme-containing inoculant on fermentation characteristics of barley silage and on growth performance of feedlot steers. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, F.D.; Snell, C.T. Colorimetric Methods of Analysis; D. van Nostrand Company Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1953; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Hristov, A.N.; McAllister, T.A.; Cheng, K.-J. Stability of exogenous polysaccharide-degrading enzyme in the rumen. Proc. West. Sect. ASAS 1997, 48, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, F.G.V.; Ávila, C.L.S.; Pinto, J.C.; Schwan, R.F. New inoculants on maize silage fermentation. R. Bras. Zootec. 2014, 43, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; France, J.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Mould, F.; Dijkstra, J. Comparison of mathematical models to describe disappearance curves obtained using the polyester bag technique for incubating feeds in the rumen. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 1875–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Inst. Inc. SAS OnlineDoc 9.3.1; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2012.

- De Boer, W.; Klein Gunnewiek, P.J.; Lafeber, P.; Janse, J.D.; Spit, B.E.; Woldendorp, J.W. Anti-fungal properties of chitinolytic dune soil bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Chen, C.; Wang, S. An antifungal chitinase produced by bacillus cereus with shrimp and crab shell powder as a carbon source. Curr. Microbiol. 2003, 47, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Updhyay, S.K.; Singh, M.; Sharma, I.; Sharma, P.; Kamboj, P.; Saini, A.; Voraha, R.; Sharma, A.K.; Upadhyay, T.K.; et al. Chitin, chitinases and chitin derivatives in biopharmaceutical, agricultural, and environmental perspective. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 9985–10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooke, J.A.; Hatfield, R.D. Biochemistry of ensiling. In Silage Science and Technology (Agronomy Series No. 42); Buxton, D.R., Muck, R.E., Harrison, H.J., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2003; pp. 95–139. [Google Scholar]

- Oude Elferink, S.J.; Krooneman, J.; Gottschal, J.C.; Spoelstra, S.F.; Faber, F.; Driehuis, F. Anaerobic Conversion of Lactic Acid to Acetic Acid and 1,2-Propanediol by Lactobacillus buchneri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, F.; Tabacco, E.; Piano, S.; Casale, M. Temperature during conservation in laboratory silos affects fermentation profile and aerobic stability of corn silage treated with Lactobacillus buchneri, Lactobacillus hilgardii, and their combination. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 1696–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, L.J.; Kung, L., Jr. Effects of combining Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 with various lactic acid bacteria on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 159, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, C.B.; Santos, A.d.O.d.; Carvalho, B.F.; Schwan, R.F.; Ávila, C.L.d.S. Wild Lactobacillus hilgardii (CCMA 0170) strain modifies the fermentation profile and aerobic stability of corn silage. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.H.; Jeong, S.M.; Kim, J.; Seo, M.J.; Baeg, C.H.; Lee, S.S.; Kang, B.S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.-C. Application effects of bacterial inoculants producing chitinase on corn silage. J. Korean Soc. Grassl. Forage Sci. 2023, 43, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, T.A.; Zenatti, T.F.; Antonio, G.; Campana, M.; Gandra, J.R.; Zilio, E.M.C.; de Mattos, L.F.A.; de Morais, J.G.P. Effect of chitosan on the preservation quality of sugarcane silage. Grass Forage Sci. 2018, 73, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, T.A.; Antonio, G.; Zilio, E.M.C.; Dias, M.S.S.; Gandra, J.R.; Castro, F.A.B.; Campana, M.; Morais, J.P.G. Chitosan level effects on fermentation profile and chemical composition of sugarcane silage. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2020, 57, e162942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, T.A.; Morais, J.P.G.; Facco, F.B.; Gandra, J.R.; Campana, M.; Capucho, E.; Garcia, T.M. Chitosan decreases fermentation losses and improves aerobic stability of rehydrated corn silage. Ciência Rural 2025, 55, e20230164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandra, J.R.; Oliveira, E.R.; Takiya, C.S.; Goes, R.H.T.B.; Paiva, P.G.; Oliveira, K.M.P.; Gandra, E.R.S.; Orbach, N.D.; Haraki, H.M.C. Chitosan improves the chemical composition, microbial quality, and aerobic stability of sugarcane silage. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 214, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandra, J.R.; Takiya, C.S.; Del Valle, T.A.; Oliveira, E.R.; de Goes, R.H.T.B.; Gandra, E.R.S.; Batista, J.D.O.; Araki, H.M.C. Soybean whole-plant ensiled with chitosan and lactic acid bacteria: Microorganism counts, fermentative profile, and total losses. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7871–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.P.G.; Cantoria Junior, R.; Garcia, T.M.; Capucho, E.; Campana, M.; Gandra, J.R.; Ghizzi, L.G.; Del Valle, T.A. Chitosan and microbial inoculants in whole-plant soybean silage. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 159, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Niu, H.; Tong, Q.; Chang, J.; Yu, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, D. The microbiota dynamics of alfalfa silage during ensiling and after air exposure, and the metabolomics after air exposure are affected by Lactobacillus casei and cellulase addition. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 519121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.É.; Liu, X.; Mellinger, C.; Gressley, T.F.; Stypinski, J.D.; Moyer, N.A.; Kung, L., Jr. Effect of dry matter content on the microbial community and on the effectiveness of a microbial inoculant to improve the aerobic stability of corn silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5024–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L., Jr. Aerobic stability of silage. In Proceedings of the California Alfalfa & Forage Symposium and Corn/Cereal Silage Conference, 1–2 December 2010; University of California Cooperative Extension: Visalia, CA, USA; Davis, CA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://alfalfasymposium.ucdavis.edu/+symposium/proceedings/2010/10-89.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Tabacco, E.; Righi, F.; Quarantelli, A.; Borreani, G. Dry matter and nutritional losses during aerobic deterioration of corn and sorghum silages as influenced by different lactic acid bacteria inocula. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item 5 | Corn Forage 1 | Silage After 90 d of Ensiling 2 | p-Value 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | E | I | EI | SEM 3 | I | E | I × E | ||

| pH | 5.84 ± 0.104 | 3.49 b | 3.55 ab | 3.54 bc | 3.60 a | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.257 |

| DM | 33.9 ± 0.87 | 33.6 | 35.0 | 33.5 | 34.4 | 0.68 | 0.245 | 0.121 | 0.227 |

| OM, % DM | 95.5 ± 0.15 | 96.0 | 95.6 | 96.1 | 96.3 | 0.30 | 0.249 | 0.789 | 0.337 |

| CP, % DM | 8.19 ± 0.22 | 8.12 | 8.02 | 8.16 | 8.45 | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.261 | 0.131 |

| ADF, % DM | 25.6 ± 2.00 | 26.7 | 28.3 | 28.1 | 26.1 | 0.98 | 0.536 | 0.783 | 0.097 |

| NDF, % DM | 44.2 ± 1.63 | 44.6 | 47.2 | 48.1 | 45.5 | 1.27 | 0.377 | 0.995 | 0.118 |

| Starch, % DM | 23.7 ± 2.17 | 22.3 | 22.5 | 20.8 | 23.4 | 1.38 | 0.337 | 0.136 | 0.154 |

| DM loss, % | NA | 6.77 | 2.87 | 4.49 | 4.41 | 2.16 | 0.862 | 0.368 | 0.388 |

| WSC, mg/g DM | 43.4 ± 6.51 | 30.5 a | 28.4 a | 6.4 b | 7.7 b | 1.47 | <0.001 | 0.803 | 0.236 |

| Fermentation products, mg g−1 DM | |||||||||

| Acetate (AC) | NA | 16.4 b | 15.7 b | 31.0 a | 29.5 a | 1.45 | <0.001 | 0.224 | 0.422 |

| Propionate | NA | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.010 | 0.640 | 0.112 | 0.875 |

| Butyrate | NA | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.027 | 0.214 | 0.103 | 0.335 |

| Total VFA | NA | 17.4 b | 16.7 b | 32.0 a | 28.7 a | 1.49 | <0.001 | 0.214 | 0.425 |

| Lactate (LA) | NA | 63.6 a | 49.9 b | 66.3 a | 44.9 c | 1.66 | 0.426 | <0.001 | 0.027 |

| LA:AC ratio | NA | 3.90 a | 3.21 b | 2.16 c | 1.61 c | 0.201 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.761 |

| Succinate | NA | 0.95 ab | 0.81 b | 1.09 a | 0.79 b | 0.056 | 0.293 | 0.004 | 0.193 |

| Ethanol | NA | 0.55 ab | 0.72 a | 0.25 b | 0.32 b | 0.108 | 0.011 | 0.303 | 0.644 |

| NH3-N | NA | 1.11 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.048 | 0.427 | 0.097 | 0.270 |

| Microbial population (log10 CFU g−1; fresh basis) | |||||||||

| Total bacteria | 9.05 ± 1.307 | 8.10 c | 8.18 c | 8.86 b | 9.08 a | 0.066 | <0.001 | 0.033 | 0.280 |

| LAB | 5.74 ± 0.293 | 7.93 d | 8.23 c | 8.87 b | 9.12 a | 0.074 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.721 |

| Yeasts | 7.65 ± 0.131 | 5.54 a | 5.71 a | ND | 1.11 b | 0.377 | <0.001 | 0.108 | 0.234 |

| Mold | 6.61 ± 0.267 | 1.09 | 0.91 | ND | ND | 0.625 | - | - | - |

| Treatments 1 | p-Value 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 4 | C | E | I | EI | SEM 2 | I | E | I × E |

| Aerobic stability (h) | 152.0 b | 156.0 b | >336.0 a | >336.0 a | 1.91 | 0.003 | 0.328 | 0.328 |

| Tmax, °C | 33.6 a | 34.7 a | 18.8 b | 18.9 b | 0.45 | <0.001 | 0.234 | 0.301 |

| Time to reach Tmax, h | 187.3 a | 194.7 a | 90.7 b | 18.7 c | 18.86 | <0.001 | 0.125 | 0.069 |

| Duration, h | ||||||||

| Days 1–3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Days 1–7 | 16.0 a | 12.0 a | 0 b | 0 b | 1.92 | <0.001 | 0.328 | 0.328 |

| Days 8–14 | 167.6 a | 167.5 a | 0 b | 0 b | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.347 | 0.347 |

| Days 1–14 | 183.6 a | 179.5 a | 0 b | 0 b | 1.92 | <0.001 | 0.320 | 0.320 |

| Area, duration (h) × temperature | ||||||||

| Days 1–3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Days 1–7 | 10.8 a | 5.7 ab | 0 b | 0 b | 1.99 | 0.003 | 0.236 | 0.236 |

| Days 8–14 | 703.9 b | 1291.4 a | 0 c | 0 c | 43.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Days 1–14 | 714.7 b | 1297.1 a | 0 c | 0 c | 41.66 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treatments 1 | p-Value 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | C | E | I | EI | SEM 2 | I | E | E × I |

| Gas production kinetics 4 | ||||||||

| A (ml g−1 DM) | 305.8 a | 314.4 a | 282.7 b | 290.4 b | 16.61 | <0.001 | 0.011 | 0.896 |

| c (h−1) | 0.185 a | 0.189 a | 0.153 b | 0.156 b | 0.0169 | <0.001 | 0.512 | 0.968 |

| Lag (h) | 1.59 ab | 1.68 a | 1.36 c | 1.49 bc | 0.241 | <0.002 | 0.034 | 0.778 |

| NDFD (%) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 38.5 a | 36.9 ab | 36.0 b | 34.7 b | 2.32 | 0.009 | 0.084 | 0.810 |

| 12 h | 60.8 a | 60.4 ab | 59.1 b | 59.7 ab | 0.80 | 0.030 | 0.889 | 0.301 |

| 24 h | 72.7 b | 72.3 b | 74.7 a | 76.7 a | 0.74 | <0.001 | 0.225 | 0.099 |

| 48 h | 82.9 b | 80.2 c | 84.9 a | 86.2 a | 0.77 | <0.001 | 0.196 | <0.001 |

| Total VFA (mmol/L) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 63.6 ab | 63.9 a | 60.0 bc | 59.1 c | 1.43 | 0.004 | 0.866 | 0.667 |

| 12 h | 81.8 a | 79.8 ab | 76.1 c | 78.0 bc | 1.35 | 0.005 | 0.995 | 0.124 |

| 24 h | 81.9 | 86.2 | 86.0 | 86.7 | 5.80 | 0.684 | 0.660 | 0.775 |

| 48 h | 102.2 | 102.4 | 101.7 | 99.0 | 7.61 | 0.635 | 0.743 | 0.715 |

| Acetate (%) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 55.7 | 56.2 | 55.6 | 55.4 | 0.68 | 0.498 | 0.785 | 0.585 |

| 12 h | 57.5 | 57.8 | 56.9 | 57.2 | 0.66 | 0.349 | 0.635 | 0.940 |

| 24 h | 55.9 | 56.1 | 55.3 | 55.5 | 0.45 | 0.159 | 0.682 | 0.993 |

| 48 h | 57.5 | 57.9 | 57.8 | 57.6 | 0.65 | 0.978 | 0.877 | 0.563 |

| Propionate (%) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 27.4 | 27.1 | 27.7 | 27.4 | 1.39 | 0.798 | 0.838 | 0.970 |

| 12 h | 25.4 | 25.0 | 26.3 | 26.0 | 1.23 | 0.425 | 0.772 | 0.924 |

| 24 h | 23.3 | 24.3 | 25.1 | 24.9 | 1.00 | 0.252 | 0.673 | 0.548 |

| 48 h | 24.0 | 23.6 | 23.8 | 24.1 | 1.13 | 0.893 | 0.954 | 0.703 |

| Butyrate (%) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 14.0 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 0.85 | 0.899 | 0.929 | 0.728 |

| 12 h | 13.7 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 0.70 | 0.457 | 0.931 | 0.950 |

| 24 h | 14.9 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 0.89 | 0.518 | 0.535 | 0.547 |

| 48 h | 12.5 | 12.6 | 12.5 | 12,4 | 0.63 | 0.874 | 0.982 | 0.850 |

| Iso-butyrate | ||||||||

| 6 h | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.023 | 0.108 | 0.258 | 0.974 |

| 12 h | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.010 | 0.360 | 0.923 | 0.360 |

| 24 h | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 0.025 | 0.957 | 0.713 | 0.753 |

| 48 h | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 0.029 | 0.042 | 0.882 | 0.984 |

| Valerate (%) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 1.49 | 1.47 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 0.128 | 0.447 | 0.995 | 0.950 |

| 12 h | 1.48 | 1.47 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 0.108 | 0.355 | 0.960 | 0.929 |

| 24 h | 1.97 | 2.00 | 1.99 | 2.03 | 0.078 | 0.692 | 0.566 | 0.941 |

| 48 h | 1.92 | 1.87 | 1.83 | 1.90 | 0.104 | 0.732 | 0.964 | 0.508 |

| Iso-valerate (%) | ||||||||

| 6 h | 0.71 b | 0.69 b | 0.78 a | 0.80 a | 0.086 | <0.001 | 0.834 | 0.192 |

| 12 h | 0.96 bc | 0.95 c | 1.02 a | 1.00 ab | 0.073 | 0.001 | 0.409 | 0.631 |

| 24 h | 2.22 | 2.16 | 2.25 | 2.21 | 0.124 | 0.552 | 0.506 | 0.898 |

| 48 h | 2.42 | 2.42 | 2.41 | 2.43 | 0.075 | 0.921 | 0.780 | 0.716 |

| Acetate/Propionate | ||||||||

| 6 h | 2.11 | 2.15 | 2.06 | 2.07 | 0.131 | 0.617 | 0.851 | 0.890 |

| 12 h | 2.32 | 2.38 | 2.22 | 2.24 | 0.132 | 0.339 | 0.737 | 0.907 |

| 24 h | 2.44 | 2.35 | 2.23 | 2.26 | 0.103 | 0.137 | 0.751 | 0.559 |

| 48 h | 2.45 | 2.51 | 2.48 | 2.43 | 0.143 | 0.788 | 0.963 | 0.706 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niu, H.; Nair, J.; Yang, H.-E.; McAllister, T.A.; Chevaux, E.; Wang, Y. The Effects of a Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacterial Inoculant Containing Lentilactobacillus hilgardii and Lentilactobacillus buchneri with or Without Chitinases on the Ensiling, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Whole-Crop Corn Silages. Fermentation 2026, 12, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010029

Niu H, Nair J, Yang H-E, McAllister TA, Chevaux E, Wang Y. The Effects of a Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacterial Inoculant Containing Lentilactobacillus hilgardii and Lentilactobacillus buchneri with or Without Chitinases on the Ensiling, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Whole-Crop Corn Silages. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Huaxin, Jayakrishnan Nair, Hee-Eun Yang, Tim A. McAllister, Eric Chevaux, and Yuxi Wang. 2026. "The Effects of a Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacterial Inoculant Containing Lentilactobacillus hilgardii and Lentilactobacillus buchneri with or Without Chitinases on the Ensiling, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Whole-Crop Corn Silages" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010029

APA StyleNiu, H., Nair, J., Yang, H.-E., McAllister, T. A., Chevaux, E., & Wang, Y. (2026). The Effects of a Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacterial Inoculant Containing Lentilactobacillus hilgardii and Lentilactobacillus buchneri with or Without Chitinases on the Ensiling, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Whole-Crop Corn Silages. Fermentation, 12(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010029