Abstract

The incorporation of native Amazonian fruits into dairy products has increased due to their ability to improve technological, sensory, nutritional, and biological properties. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) pulp on the chemical, physical, and sensory characteristics of fermented milk, using a central rotational composite design with two factors (sugar and cupuassu pulp). Our results are presented as response surfaces, showing that cupuassu pulp is positively associated with the examined parameters (pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids, total phenolic compounds, syneresis, and water retention capacity). The analysis suggested a promising formulation containing 27.8% cupuassu pulp and 8.6% sugar. The pulp and this promising formulation were characterized by pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids, proximate composition, and bioactive compounds (total phenolic compounds (TPC) and antioxidant activity). The physicochemical stability of the beverage was monitored over 28 days. Sensory acceptance and purchase intention for the promising formulation were also evaluated. Cupuassu contributed to an increase in soluble solids, while pH and titratable acidity remained stable during storage. Additionally, cupuassu pulp increased the total phenolic content and enhanced the beverage’s antioxidant activity. Sensory analysis showed that adding cupuassu pulp positively influenced all evaluated attributes (83% acceptance) and was associated with a favorable purchase intention. Incorporating cupuassu pulp into fermented milk proved to be technologically feasible and sensorially acceptable, meeting the demand for innovative dairy beverages with functional and sensory benefits.

1. Introduction

Fermented milk is a nutritious product rich in high-biological-value proteins, vitamins, and minerals, contributing significantly to a balanced diet. Regular consumption of dairy products has been associated with health benefits, including muscle development, improved bone health, and a reduced risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease [1,2,3]. Recent studies have shown that incorporating native fruits into the production of fermented dairy products, especially fermented milk, is beneficial. Amazonian fruits such as açaí, araçá-boi, and cupuassu remain a relevant source of bioactive compounds and have been successfully explored in studies on fermented foods [4,5,6,7].

Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) is a fruit native to the Amazon rainforest, known for its phenolic and flavonoid content, including epicatechin and quercetin. Due to its high content of bioactive compounds, cupuassu pulp has potential applications in health-promoting foods [4,8]. Additionally, it is a source of antioxidants, including flavan-3-ol monomers (flavanols) and their oligomers, which are proanthocyanidins [9]. These compounds are linked to various health benefits, such as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [10].

Cupuassu is recognized in the food industry for its unique flavor, high nutritional value, bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity, and economic potential [5,8]. Its incorporation into fermented matrices, such as dairy-based beverages, has the potential to expand flavor diversity, enhance nutritional and sensory attributes, and align consumer demand for functional foods with health-promoting attributes [5,10].

The incorporation of fruit-derived matrices into fermented dairy systems, such as cupuassu pulp, has been associated with enhanced functional properties and improved sensory performance, and has also contributed to key technofunctional attributes, including flavor, aroma, color, texture, and acidity [5,6,9]. Nevertheless, the development of fruit-enriched fermented milk formulations presents challenges related to product stability, matrix interactions, and sensory acceptability, which must be addressed to stabilize and produce a sensorially acceptable product fully. These challenges must be addressed to realize the potential of functional foods to improve health and support economic development. In addition to its technological potential, the fruit plays an essential socioeconomic role in the Amazon region, contributing to the income of small producers and adding value to the production chain by developing fermented foods [11].

Although the fruit has excellent potential, few studies have examined the use of cupuassu pulp in fermented milk. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) on the chemical, physical, and sensory qualities of fermented milk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The ingredients used to prepare the fermented milk included: whole Ultra High Temperature (UHT) milk (100 mL serving—57.5 kcal; 4.55% carbohydrates; 3.05% protein; 3.0% total fat; 1.8% saturated fat; 0.12% sodium; 0.24% calcium) (Piracanjuba, Cuiabá, Brazil), granulated sugar (Itamarati, Cuiabá, Brazil), freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria cultures containing Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium cultures (BioRich®, Cuiabá, Brazil), and frozen cupuassu pulp (100 g serving—62 kcal; 10% carbohydrates; 1.2% protein; 1% total fat; 0.4% saturated fat; 3.1% Total dietary fiber) (Pantanal Ind. E Com. De Polpa de Frutas e Alimentos LTDA, Cuiabá, Brazil).

The reagents used for analytical determination included: methanol (Anidrol, São Paulo, Brazil), sodium carbonate (Cromato Químicos Produtos, São Paulo, Brazil), Folin–Ciocalteau reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), ABTS (2.2′-azino-bis (ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine), Potassium persulfate and HCl (Synth, São Paulo, Brazil), oxalic acid (Dinâmica, São Paulo, Brazil), and ferric chloride (Isofar, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

2.2. Experimental Design and Preparation of Cupuassu Fermented Milk (FM-C)

This study was divided into three stages, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the experimental design.

In the first stage, the central composite rotational design (CCRD) was employed for a promising formulation of fermented milk, considering two independent variables: the concentration of added sugar (X1: 0.0–8.6%) and the concentration of cupuassu pulp (X2: 17.2–27.8%) (Table 1). The concentration ranges of sugar and cupuassu pulp were determined in preliminary tests. For sample preparation, the lactic acid bacteria (BioRich®) were homogenized in whole milk in a plastic beaker, and then sugar was added. The mixture was homogenized, packaged in glass bottles, and incubated in a germination chamber (TE-4020 LED, Tecnal, São Paulo, Brazil) at 40 °C for 5 h. After fermentation, cupuassu pulp was incorporated, the beverages were homogenized manually immediately after fermentation, and the samples were stored at 7 °C under refrigeration.

Table 1.

Central composite rotational design (CCRD) of Cupuassu sugar and pulp concentrations, in coded variables and real values (X1: Sugar (%), X2: Cupuassu pulp (%)).

The treatments were evaluated for TPC, syneresis, water retention capacity (WRC), pH, soluble solids (°Brix), and titratable acidity. The experimental data was processed using a second-order polynomial model (Equation (1)) and analyzed by ANOVA.

where Y is the response variable, X1 and X2 are the coded variables, the values of β are the estimated regression coefficients, and ε represents the experimental error. Response surface plots were generated for each variable using STATISTICA® 10.0 software. The predictive models were validated through triplicate trials with the promising formulation (fermented milk containing cupuassu pulp), and the experimental values were compared with the predicted responses using Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

In the first and second stages (Figure 1), both the raw material and the promising formulation were characterized by total phenolic compounds, syneresis, WRC, pH, soluble solids (°Brix), titratable acidity, antioxidants (ABTS and FRAP), and proximate composition.

Fermented milk was prepared under the same processing conditions as previously described, using the promising formulation. The product was packaged in 50 mL beakers, in triplicate, and stored at 7 °C. Samples were analyzed on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 for total soluble solids, titratable acidity, pH, syneresis, water retention capacity, and instrumental texture. Additionally, samples collected on days 1, 14, and 28 were stored at −18 °C for the measurement of total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity (ABTS and FRAP methods).

2.3. pH, Soluble Solids (°Brix), and Titratable Acidity

The pH of fermented milk was measured using a digital pH meter (Ms Tecnopon Instrumentação, Mpa-210, Piracicaba, Brasil) according to the methodology proposed by the Analytical Standards of the Adolfo Lutz Institute—017/IV [12]. Total soluble solids were determined by refractometry using an Abbé refractometer with a graduated Brix scale—316/IV (c). Titratable acidity was determined by titration with 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution with a pH between 8.2 and 8.4 [13]. The results will be expressed as a percentage of % lactic acid.

2.4. Syneresis and Water Retention Capacity (WRC)

Syneresis (%) (Equation (2)) and WRC (%) (Equation (3)) analyses were performed using centrifugation-based methods as described by Mohamed Ahmed et al. [14]. The following equations were used for the calculations:

2.5. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds

The cupuassu pulp extract was prepared for analysis of bioactive compounds according to the methodology proposed by Ayoub et al. [15], with modifications. To prepare the extract, 2 g of cupuassu pulp was added to 10 mL of 80% methanol in a tube. The extracts were placed on a shaking table (SP-180/S, KOVOSVIT MAS, São Paulo, Brazil) for 30 min at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) and protected from light. They were then transferred to a centrifuge (Hettich, Rotina 380R, Tuttlingen, Germany) for 5 min at 5 °C. The supernatant was stored at 4 °C in a freezer. For the analysis of bioactive compounds in fermented milk, samples were centrifuged (Hettich, Rotina 380R, Tuttlingen, Germany) for 10 min at 5000× g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was stored at 4 °C in a freezer for analysis.

2.5.1. Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds

The total phenolic compounds were quantified using the Folin–Ciocalteau method [16]. The results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) µg·100 g−1.

2.5.2. ABTS and FRAP Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant assay using the ABTS free radical-scavenging method was performed according to the methodology proposed by Nenadis et al. [17]. The results were expressed as μM of Trolox equivalent (TE) µmL·100 g−1. The iron reduction assay (FRAP) was estimated according to the methodology proposed by Pulido et al. [18]. The results were expressed as μM of ferrous sulfate equivalent µmL·100 g−1.

2.6. Proximate Composition

Proximate composition analyses were performed on cupuassu pulp, control fermented milk, and a promising formulation of fermented milk with cupuassu pulp. At the same time, soluble and insoluble dietary fiber were determined exclusively for cupuassu pulp. Moisture content (AOAC 925.45b) was determined by the thermogravimetric method in a drying oven (SOLAB, SL-102, Piracicaba, Brazil) at 105 °C. Ash content (AOAC 923.03) was measured by incinerating in a muffle furnace (Magnus, Ltd., 200 °F, São Vicente, Brazil) at 550 °C.

Lipid content in cupuassu pulp was quantified using the Soxhlet method (AOAC 920.39) with petroleum ether as the extraction solvent, and results were expressed as % on a wet basis. For fermented milk samples, the lipid content was determined using the Monjonnier method as described in ISO 23318:2022 [19]. Protein determination was quantified using the micro-Kjeldahl method (AOAC 960.52) using a nitrogen distiller (Tecnal TE-0364, Piracicaba, Brazil). All analyses were performed in triplicate [20] and results were expressed as % on a wet basis. Total dietary fiber (soluble and insoluble) in cupuassu pulp was determined using the AOAC enzymatic method [21]. Total and digestible carbohydrates (Equations (4) and (5)) were calculated by difference according to the legislation [22].

2.7. Texture Analysis

The texture of fermented milk was assessed for firmness, consistency, and cohesiveness. The analysis was performed using TA-XTplus Stable Micro System equipment (Stable Micro Systems Ltd., Godalming, UK), with pre-test speed: 1 mm/s; test speed: 1 mm/s; post-test speed: 5 mm/s; analysis distance: 30 mm (compression of approximately 70% of the sample volume); probe: acrylic cylinder with a diameter of 20 mm; trigger force: 10 g; sample volume: 50 mL; temperature: 6 ± 2 °C.

2.8. Viability of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) During Storage

For LAB analysis, 1 mL of fermented milk was added to 9 mL of sterile peptone water (0.1 g·100 mL−1—dilution 10−1), followed by dilutions up to 10−7. Next, 1 mL of each dilution was plated on Man Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 48 h in a BOD incubator (Biochemical Oxygen Demand). The results were expressed as the logarithm of the number of colony-forming units per milliliter of fermented milk (log CFU·mL−1). The analyses were conducted in triplicate on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 of product storage.

2.9. Sensory Analysis

The microbiological safety assessment of FM-C was conducted before sensory testing. Analyses for Salmonella/25 mL [23], Escherichia coli mL−1 [24], and Molds and Yeasts mL−1 [25] were performed. The results were then compared against Brazilian standards established by Normative Instruction No. 161, dated 1 July 2022 [25].

The sensory analysis of a promising cupuassu-fermented milk formulation was conducted using affective acceptance and purchase intention tests, as described by Dutcosky [26]. The sensory attributes assessed included appearance, color, texture, flavor, and overall evaluation. A structured nine-point hedonic scale was employed, ranging from 1 (disliked extremely) to 9 (liked extremely). The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Mato Grosso, protocol code 6.768.397.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Multiple analyses of variance evaluated the data, and the models were adjusted and visualized using response surface graphs, with the aid of STATISTICA® 7.0 software. The models were validated in a three-replication trial, using the central point. XLSTAT software (version 2024.4.1) was used for statistical analysis. Tukey’s test was used to compare means (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Selection of a Promising Formulation

The responses obtained from the CCRD, along with experimental data on CFT, CRA, syneresis, pH, total soluble solids, and titratable acidity, are presented in Table 2. It is worth highlighting that the ‘lack of fit’ for the pH, acidity, °Brix, WRC, and Syneresis models was significant. This result indicates that the polynomial model generated by the response surface is a mathematical simplification that proved insufficient to capture the complex nonlinear kinetics of the microbial fermentation process.

Table 2.

Models adjusted for total soluble solids (°Brix), pH, Titratable acidity, WRC, Syneresis, and TPC. x1 = sugar (%); x2 = cupuassu pulp (%).

The model adjusted for soluble solids (°Brix) showed a positive linear and a negative quadratic effect for the sugar variable and a positive linear effect for the pulp variable (Table 2). Thus, the addition of sugar increases the soluble solids content (Figure 2A). This result is consistent with the literature, since the soluble solids content is closely related to the amount of sugar added to fermented milk [27].

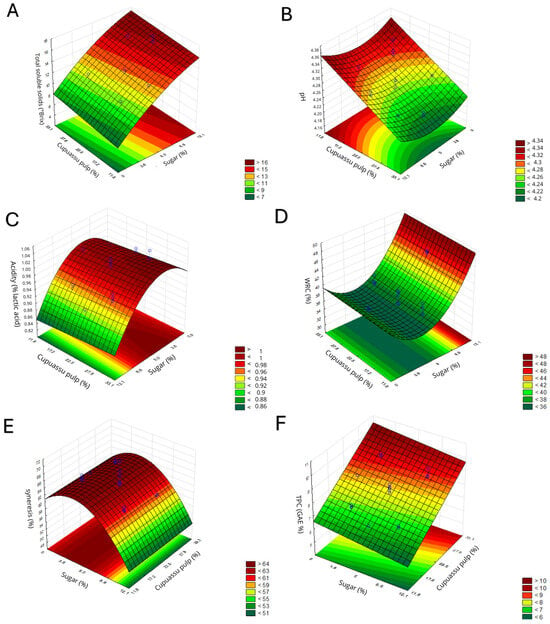

Figure 2.

Effect of cupuassu pulp (%) and sugar (%) concentrations in fermented milk, obtained by a Central composite rotational design (CCRD), on quality parameters: soluble solids (°Brix) (A), pH (B), titratable acidity (% lactic acid) (C), WRC (%) (D), syneresis (%) (E) and TPC (GAE %) (F).

The model adjusted for pH indicated a positive quadratic effect of sugar and an adverse linear effect of pulp. The reduction in pH is due to the production of lactic acid during the beverage’s fermentation. The quadratic effect of adding sugar can be explained by its buffering action, which contributes to pH stability by interacting with acids produced during fermentation, resulting in a less acidic product [28]. In addition, sugar serves as a substrate for bacterial growth, influencing texture and sensory attributes without significantly altering pH [29]. The promising formulation for the pH variable indicates an optimal cupuassu pulp concentration of 22.5%, while the sugar concentration ranges from 2 to 9%. (Figure 2B). However, the variation in pH values was low (0.10), which justifies the poor fit of the model (Table 2).

In the titratable acidity analysis, the adjusted model showed negative linear and quadratic effects of the sugar variable (Table 2). Thus, the addition of sugar reduced the product’s acidity, as sugar availability can influence the growth and activity of lactic acid bacteria [28]. The negative quadratic effect is consistent with the results obtained for pH, suggesting that sugar concentrations between 4 and 7% act as buffers, helping maintain the product’s pH and acidity.

On the other hand, the addition of cupuassu pulp did not significantly affect titratable acidity, which corroborates the pH results, in which the pulp had minimal effect on pH. Under acidic conditions, protein denaturation and aggregation occur, mainly affecting casein and whey proteins, which are highly sensitive to low pH, leading to loss of solubility and subsequent precipitation [30]. Thus, for the acidity and pH variables, we can conclude that the sugar concentration that performed best was 3–8% (Figure 2C).

In the model adjusted for WRC, the sugar variable showed positive linear and quadratic effects. As for syneresis, the effects were inverse, with negative linear and quadratic effects on the sugar variable (Table 2). These results show that the addition of sugar improves the WRC of fermented milk, reducing syneresis, as it promotes the formation of a more stable gel and increases water retention [31].

As shown in Figure 2D, regardless of the percentage of cupuassu pulp added, there was no significant effect on the WRC and syneresis of fermented milk, with the best results obtained at sugar concentrations between 8 and 9%. Previous studies using cupuassu pulp and flour reported that the addition of the fruit increased WRC in fermented milk and reduced syneresis in an inverse manner [5].

The regression model adjusted for TPC indicated a negative linear effect for the sugar variable and a positive linear effect for the cupuassu pulp variable (Table 2). These compounds enhance the nutritional value, functional properties, and sensory characteristics of fermented milk [32,33]. Therefore, the addition of cupuassu pulp increases the concentration of phenolic compounds in the beverage. It should be noted that the model obtained for phenolic compounds is considered predictive, as the model’s lack of fit was not significant (Table 2). Based on this, the promising formulation was selected using the phenolic compounds curve, specifically in the region corresponding to the beverage with the highest TPC. This decision also considered sensory pre-tests, which identified that beverages with added sugar concentrations between 8 and 12 g were the most preferred. Thus, to obtain a desirable beverage with a higher TPC content, the concentration of cupuassu pulp should be 27.8% and that of sugar 8.6% (Figure 2F). To validate the experimental model, the promising formulation (27.8% cupuassu pulp concentration and 8.6% sugar concentration) was prepared and reassessed for TPC. The predicted value (6.29 GAE μg·100 g−1) was lower than the value found in the validation (8.84 GAE μg·100 g−1), resulting in a 28% error. Once again, the high error observed reinforces that the complexity of the fermentation process is not adequately represented by the polynomial equations generated by the response surface model.

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Cupuassu Pulp and Beverages

The results of the physical-chemical composition of cupuassu pulp, control fermented milk, and promising formulation (FM-C) are presented in Table 3. The samples, control fermented dairy, and promising formulation (FM-C) were analyzed on day 1 of the shelf life. In Table 3, standard deviations are not reported for dietary fiber fractions (total, insoluble, and soluble) or carbohydrates, as these values were derived from a single analytical characterization of the cupuassu pulp using AOAC methods. Because these parameters reflect the intrinsic composition of the pulp rather than variability across formulation replicates, no standard deviation is applicable. Additionally, dietary fiber, total carbohydrates, and digestible carbohydrates were not determined for the control fermented milk. The AOAC enzymatic–gravimetric method is specific to plant matrices; since the control formulation contained no plant-derived ingredients, these analyses were considered not applicable, and the corresponding cells were left blank.

Table 3.

Physical and chemical composition of cupuassu pulp (Theobroma grandiflorum), control fermented milk, and FM-C (Mean ± SD).

The cupuassu pulp sample had a total dietary fiber content of 5.26%, with 4.38% insoluble fiber and 0.88% soluble fiber, which is significant given the total fiber content [34]. Cupuassu pulp contains polysaccharides such as pectin and dietary fiber, which influence the texture of the fruit and, consequently, the texture of fermented milk with cupuassu pulp [35].

Fermented milk with added cupuassu pulp showed similar trends in pH compared to the control (without added pulp). At the same time, titratable acidity remained virtually unchanged, with a variation in less than. The levels of soluble solids, titratable acidity, and pH vary depending on processing. Generally, the pulp is acidic and rich in soluble solids, contributing to its characteristic flavor [36].

Fermented milk with cupuassu pulp showed an approximately 15% increase in soluble solids compared to the control, demonstrating the effect of incorporating the fruit. The increase in soluble solids, especially sugars, contributes to a sweeter taste and can enhance fruity aromas, depending on the ingredients added, such as fruit pulps or juices. In addition, they can improve texture by increasing viscosity and making it creamier [37,38].

The presence of pulp resulted in higher total phenolic content and greater antioxidant activity, as demonstrated by FRAP and ABTS values, indicating enrichment of bioactive compounds in the pulp and thus enhancing the fermented milk drink with cupuassu pulp. Bioactive compounds present in fruits, such as polyphenols, increase the antioxidant activity of fermented milk, helping to combat oxidative stress and inflammatory processes in the body [33,39,40]. One of the main compounds found in the fruit pulp is methylxanthine alkaloids, which are also associated with antioxidant capacity and the prevention of chronic diseases [8,10,35].

Cupuassu stands out among Amazonian fruits for its intense flavor and aroma, sensory attributes that give it identity and potential for acceptance in fermented dairy products. Although recent studies indicate that cupuassu has lower levels of antioxidant compounds than Amazonian fruits such as açaí (Euterpe oleracea) and araçá-boi (Eugenia stipitate), it is still considered rich in bioactive compounds. However, in another study, cupuassu stands out for its balance between antioxidant compounds, aroma, flavor, and technological potential when compared to bacuri (Platonia insignis) [4]. In addition to its diverse phytochemical profile, the pulp’s neutral color makes it suitable for use in dairy products, as it does not visually interfere with the appearance of fermented milk. This combination of sensory characteristics and technological stability makes cupuassu a particularly attractive ingredient for developing fermented milks [5,6].

3.3. Shelf Life

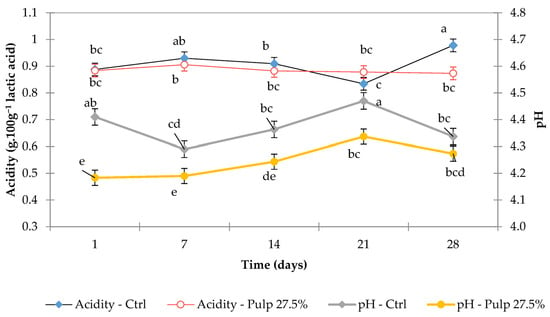

Figure 3 shows the evolution of pH and titratable acidity during the 28 days of storage of the control fermented milk and FM-C (27.5%). The Type III sum of squares indicated that the pH variable had a greater influence on pulp addition than on storage time. The reduction in pH in fermented milk beverages with added pulp is closely associated with the specific properties of cupuassu pulp and to the dynamics of microbial activity during storage [5].

Figure 3.

Acidity (% lactic acid) and pH values of control fermented milk and FM-C on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 of storage. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between storage times within the same formulation.

In the acidity analysis, the interaction between pulp addition and storage time had a combined impact (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S1). The acidity of fermented milk with cupuassu pulp and control samples remains stable throughout shelf life due to the balance between lactic acid bacteria activity, the properties of the added fruit pulp, and storage conditions.

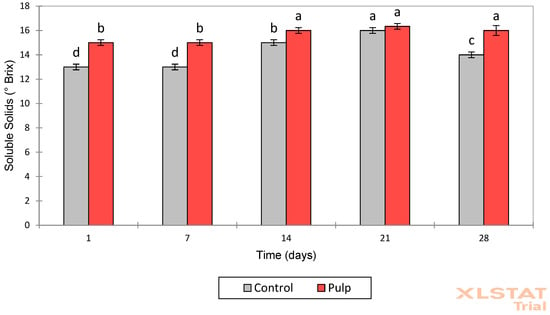

Storage time was the factor with the most significant impact (p < 0.0001) on the variation in total soluble solids (°Brix) (Figure 4, Supplementary Table S1). Cupuassu pulp, rich in sugars, organic acids, and bioactive compounds, contributes to an increase in °Brix. Variations in soluble solids over time reflect the consumption and transformation of sugars and other soluble components by microorganisms, as well as the influence of added cupuassu pulp on the composition and stability of the product [41].

Figure 4.

Soluble solids values (°Brix) of control fermented milk and FM-C on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between storage times within the same formulation.

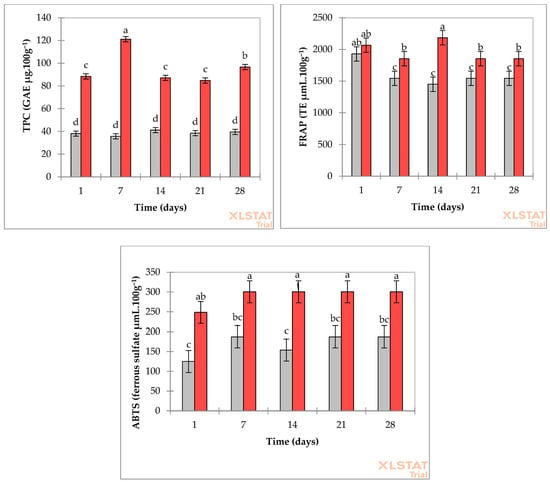

The concentration of cupuassu pulp was the factor that most influenced total phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity (ABTS and FRAP) in fermented milks, as indicated by analysis of variance (Type III) (Supplementary Table S1, Figure 5). FM-C resulted in increased TPC, FRAP, and ABTS levels at all storage times compared to control beverages, which showed reduced values over time. This result was expected because cupuassu pulp was added, which contains significant amounts of bioactive compounds [5].

Figure 5.

Total phenolic compound and antioxidant values (TPC, FRAP, and ABTS) of control fermented milk (gray bars) and FM-C (red bars) on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between storage times within the same formulation.

In the TPC analysis, a peak was observed on day 7, followed by reductions on days 14 and 21, and an increase on day 28. FRAP antioxidant capacity and content increased until day 14, reaching a maximum, but thereafter decreased on days 21 and 28. Finally, in the ABTS method, the fermented milk formulation with pulp showed higher and more stable values from day 7 to day 28 than on day 1. In contrast, the formulation without pulp showed low values that gradually increased over the first 14 days (Figure 5).

In the first days of storage, bioactive compounds such as phenolics and flavonoids can be degraded by oxidation, hydrolysis, or reactions with other milk components, thereby reducing their concentration [11,40,42]. Bioactive compounds in fruits can slow the growth of spoilage microorganisms, thereby increasing the shelf life of fermented milks [32,33]. In this way, FM-C can increase total phenolic compounds without altering its technological properties.

The concentration of cupuassu pulp was the variable with the most significant influence on syneresis in fermented milks (Table 4, Supplementary Table S1).

Table 4.

Syneresis, water retention capacity (WRC), and texture (firmness, cohesiveness, and consistency).

This is evidenced by higher levels of syneresis in pulp treatment, regardless of storage time. The presence of pulp compounds may have interfered with the formation and stability of the protein gel, thereby compromising the product’s water-retention capacity. Thus, the effects of pulp concentration overlap with the effects of time, justifying its greater statistical contribution. Fruit pulps, such as fig, cupuassu, and kiwi, increase the water retention of fermented milk, resulting in lower and more stable syneresis values over time [11].

The concentration of cupuassu pulp was the variable with the most significant influence on texture (firmness, cohesiveness, and consistency) in fermented milks (Table 4, Supplementary Table S1). Both treatments exhibited stable values for firmness, cohesiveness, and consistency throughout the Shelf-life period, with minimal variation between them and no significant difference. Thus, the addition of cupuassu pulp does not compromise the product’s firmness during storage. In fact, research shows that cupuassu pulp can help maintain or even improve the texture and firmness of fermented dairy products over time.

3.4. Viability of LAB

The results of the Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) count (CFU mL−1) of control fermented milk, and promising beverage (FM-C) are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) count (log CFU/mL) of control fermented milk and fermented milk with cupuassu pulp.

On day 1, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) counts were similar between the control and FM-C samples, indicating that the addition of cupuassu pulp did not negatively interfere with microbial development (log CFU/mL) (Table 5). These results suggest that cupuassu pulp provides adequate substrates for lactic culture growth, thereby favoring their viability in fermented milk.

During storage, an increase in LAB count was observed in both samples on day 7. However, FM-C showed lower values than the control. During fermentation, a gradual reduction in pH can be observed, compromising the viability of some lactic acid bacterial strains. In addition, bioactive compounds in cupuassu, especially polyphenols, can exhibit antimicrobial activity depending on the concentration used [43]. Another explanation for the reduction on the fourteenth day may be the temperature variation, which negatively affects their viability [43,44].

As fermentation progresses and during storage, lactic acid and other organic acids accumulate, resulting in a lower pH. A more acidic product can kill lactobacilli, reducing their viability during shelf life [45,46]. In addition, during storage, some compounds present in milk may decrease over time, limiting the resources necessary for the survival and growth of microorganisms [46]. These factors may justify the reduction in LAB viability on the 14 days of storage until the last day. Therefore, cupuassu pulp is a promising matrix for the application of lactic acid bacteria, maintaining viability, sensory quality, and microbiological safety.

3.5. Sensory Analysis

In the microbiological safety assessment, all results met the standards established by Brazilian current legislation (absence of Salmonella/25 mL, E. coli < 10 CFU mL−1, and molds and yeasts < 10 CFU mL−1). Therefore, the fermented milk samples were considered microbiologically safe for sensory evaluation.

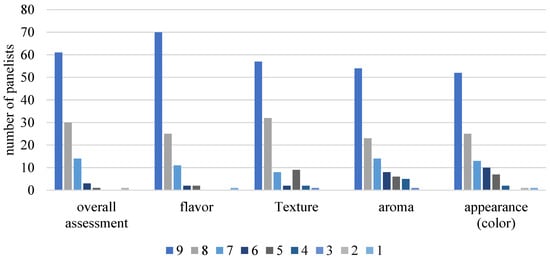

Of the 111 (n = 111) participants untrained in sensory analysis, 69 were female, and 40 were male. The average age of the tasters was 25.09 years, ranging from 18 to 55 years. The samples (15 mL) were served at 15 ± 2 °C in white plastic cups randomly coded with three digits, and water at room temperature was provided for mouth rinsing. Of the total number of participants, 30% reported consuming fermented milk once a week, 28.2% 2 to 4 times a week, 35.5% less than once a month, 5.5% once a day, and 0.9% never consumed fermented milk. The sensory acceptance results ranged from 9 (Liked extremely) to 8 (Liked very much), showing good acceptance of the product, with 83% (8.29 ± 1.06) for overall evaluation, 86% (8.38 ± 1.13) for flavor, 80% (8.05 ± 1.38) for texture, 69% (7.83 ± 1.52) for aroma, and 69% (7.79 ± 1.60) for appearance or color of the product (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sensory acceptance of promising fermented milk (FM-C). Hedonic scale: 9—Liked immensely, 8—Liked very much, 7—Liked moderately, 6—Liked slightly, 5—Neither liked nor disliked, 4—Disliked slightly, 3—Disliked moderately, 2—Disliked very much, 1—Disliked extremely.

The results showed that the addition of cupuassu pulp had a positive influence on all sensory attributes evaluated. These results are consistent with other studies showing that adding fruit pulp can significantly improve the taste, aroma, texture, and appearance of fermented milks, increasing their sensory acceptance [47,48,49].

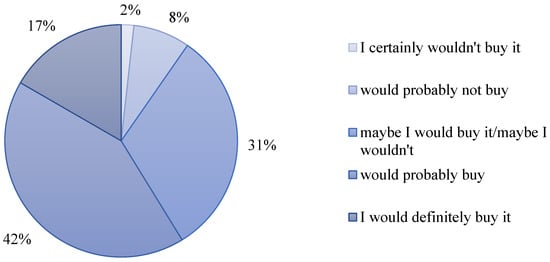

The FM-C showed strong purchase intent, with 42% of tasters indicating they would buy the product and 31% indicating they would probably buy it (Figure 7). The results show that cupuassu milk drinks were well accepted and have market potential, mainly because consumers recognize the product’s nutritional and functional benefits [7].

Figure 7.

Intention to purchase promising fermented milk (FM-C).

The use of this type of fruit adds regional value to the product and meets the demand for new fermented milk drink options with attractive functional and sensory potential.

4. Conclusions

The addition of cupuassu pulp to fermented milk increased total soluble solids, and the pH profile and titratable acidity remained stable throughout 28 days of storage, maintaining appropriate conditions for microbiological and sensory stability. In addition, the addition of pulp increased the total phenolic content and enhanced antioxidant activity. In sensory evaluation, the product was well accepted, indicating the viability of using this native Amazonian fruit to develop functional dairy beverages with commercial appeal. It can be concluded that adding cupuassu pulp to fermented milk is feasible from technological, nutritional, and sensory perspectives, thereby contributing to the appreciation of native Amazonian fruits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010020/s1, Table S1: ANOVA: Summary for all Y.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Y.O.D., M.C.M. and J.A.C.B.; methodology Y.O.D., R.A.d.S.M., C.P. and A.R.d.S.S.; formal analysis J.A.C.B.; investigation Y.O.D., R.A.d.S.M., A.R.d.S.S. and A.P.P.; resources M.C.M. and C.P.; writing—original draft Y.O.D.; writing—review and editing A.P.P., M.C.M. and J.A.C.B.; supervision M.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GERES CDESU NOTICE grant number 2024.001 , and supported by FAPEMAT (Mato Grosso State Research Support Foundation) scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Nutrition at the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT-Brazil), protocol code 6.768.397 on 16 April 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Garofalo, G.; Gaglio, R.; Busetta, G.; Ponte, M.; Barbera, M.; Riggio, S.; Piazzese, D.; Bonanno, A.; Erten, H.; Sardina, M.T.; et al. Addition of fruit purees to enhance quality characteristics of sheep yogurt with selected strains. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, Á.; Ortega, R.M. Introduction and Executive Summary of the Supplement, Role of Milk and Dairy Products in Health and Prevention of Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases: A Series of Systematic Reviews. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S67–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granato, D.; Barba, F.J.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Putnik, P. Functional Foods: Product Development, Technological Trends, Efficacy Testing, and Safety. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Carvalho, A.P.; da Silva Pena, R.; Chisté, R.C. Oven-Dried Cupuaçu and Bacuri Fruit Pulps as Amazonian Food Resources. Resources 2024, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Álzate, K.; Rosario, I.L.S.; de Jesus, R.L.C.; Maciel, L.F.; Santos, S.A.; de Souza, C.O.; Vieira, C.P.; Cavalheiro, C.P.; Costa, M.P. Physicochemical, Rheological, and Nutritional Quality of Artisanal Fermented Milk Beverages with Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) Pulp and Flour. Foods 2023, 12, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.C.R.; Martins, C.P.C.; Soutelino, M.E.M.; Rocha, R.S.; Cruz, A.G.; Mársico, E.T.; Silva, A.C.O.; Esmerino, E.A. An overview of the potential of select edible Amazonian fruits and their applications in dairy products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 65, 5572–5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.P.R.; Ferreira, B.M.; Freire, L.; Angélica Neri-Numa, I.; Guimarães, J.T.; Rocha, R.S.; Pastore, G.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Enhancing the functionality of yogurt: Impact of exotic fruit pulps addition on probiotic viability and metabolites during processing and storage. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.V.A.; Salimo, Z.M.; de Souza, T.A.; Reyes, D.E.; Bassicheto, M.C.; de Medeiros, L.S.; Sartim, M.A.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Gonçalves, J.F.C.; Monteiro, W.M.; et al. Cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum): A Multifunctional Amazonian Fruit with Extensive Benefits. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.S.D.; Oliveira Moreira, P.I.; Carvalho, A.V.; Freitas-Silva, O. Cupuassu Fruit, a Non-Timber Forest Product in Sustainable Bioeconomy of the Amazon—A Mini Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.S.D.; Santos, O.V.D.; Lannes, S.C.D.S.; Casazza, A.A.; Aliakbarian, B.; Perego, P.; Ribeiro-Costa, R.M.; Converti, A.; Silva Júnior, J.O.C. Bioactive compounds and value-added applications of cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum Schum.) agroindustrial by-product. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruel-Andreu, C.; Jiménez-Redondo, N.; Muelas, R.; Carbonell-Pedro, A.A.; Hernández, F.; Sendra, E.; Cano-Lamadrid, M. Techno-functional properties and enhanced consumer acceptance of whipped fermented milk with Ficus carica L. By-products. Food Res. Int. 2024, 195, 114959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAL. Métodos Físico-Químicos Para Análise de Alimentos, 4th ed.; 1st ed. digital; Instituto Adolfo Lutz: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11869:2012; I.T. Fermented Milks—Determination of Titratable Acidit—Potentiometric Method. International Dairy Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Alqah, H.A.S.; Saleh, A.; Al-Juhaimi, F.Y.; Babiker, E.E.; Ghafoor, K.; Hassan, A.B.; Osman, M.A.; Fickak, A. Physicochemical quality attributes and antioxidant properties of set-type yogurt fortified with argel (Solenostemma argel Hayne) leaf extract. LWT 2021, 137, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M.; de Camargo, A.C.; Shahidi, F. Antioxidants and bioactivities of free, esterified and insoluble-bound phenolics from berry seed meals. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woisky, R.G.; Salatino, A. Analysis of propolis: Some parameters and procedures for chemical quality control. J. Apic. Res. 1998, 37, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenadis, N.; Wang, L.-F.; Tsimidou, M.; Zhang, H.-Y. Estimation of Scavenging Activity of Phenolic Compounds Using the ABTS•+ Assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4669–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, R.; Bravo, L.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3396–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 23318:2022; Milk and Milk Products—Determination of Fat Content—Gravimetric Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- AOAC. Official Method 985.29; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Method 985.29. Section 45.4.07. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Arlington, VA, USA, 1997; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Ministério Da Saúde, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Instrução Normativa n° 75, de 8 de Outubro de 2020; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ABNT. NBR ISO 6579-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Method for Detection of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017.

- ABNT. NBR ISO 16649-2; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feed—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of β-Glucuronidase-Positive Escherichia coli—Part 2: Colony Counting Technique at 44 °C Using 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronide. International Organization for Standardization: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020.

- BRAZIL. Normative Instruction No. 161, 1 July 2022. Establishes Microbiological Standards for Foods; Official Journal of the Federative Republic of Brazil; Ministry of Health/National Health Surveillance Agency: Brasília, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dutcosky, S.D. Análise Sensorial de Alimentos. 2019. p. 426. Available online: https://www.livros1.com.br/pdf-read/livar/AN%C3%81LISE-SENSORIAL-DE-ALIMENTOS.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sidira, M.; Mitropoulou, G.; Galanis, A.; Kanellaki, M.; Kourkoutas, Y. Effect of Sugar Content on Quality Characteristics and Shelf-Life of Probiotic Dry-Fermented Sausages Produced by Free or Immobilized Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. Foods 2019, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, D.; Marciniak-Lukasiak, K.; Karbowiak, M.; Lukasiak, P. Effects of Fructose and Oligofructose Addition on Milk Fermentation Using Novel Lactobacillus Cultures to Obtain High-Quality Yogurt-Like Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Bhandari, B.; Gaiani, C.; Prakash, S. Physicochemical and microstructural properties of fermentation-induced almond emulsion-filled gels with varying concentrations of protein, fat and sugar contents. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, T.; Horne, D.S.; Lucey, J.A. Yogurt made from milk heated at different pH values. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6749–6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, F.C.; Teixeira, E.d.F.; Pacheco, A.F.C.; Paiva, P.H.C.; Tribst, A.A.L.; Leite Júnior, B.R.d.C. Impact of ultrasound-assisted fermentation on buffalo yogurt production: Effect on fermentation kinetic and on physicochemical, rheological, and structural characteristics. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, T.F.; Casarotti, S.N.; Penna, A.L.B. Lacticaseibacillus casei SJRP38 and buriti pulp increased bioactive compounds and probiotic potential of fermented milk. LWT 2021, 143, 111124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestes, A.A.; Verruck, S.; Vargas, M.O.; Canella, M.H.M.; Silva, C.C.; da Silva Barros, E.L.; Dantas, A.; de Oliveira, L.V.A.; Maran, B.M.; Matos, M.; et al. Influence of guabiroba pulp (Campomanesia xanthocarpa o. berg) added to fermented milk on probiotic survival under in vitro simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.M.D.; Silva, K.A.D.; Santos, I.L.; Yamaguchi, K.K.D.L. Aproveitamento integral do cupuaçu na área de panificação. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e34711528176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.d.A.; Corrêa, R.F.; Sanches, E.A.; Lamarão, C.V.; Stringheta, P.C.; Martins, E.; Campelo, P.H. “Cupuaçu” (Theobroma grandiflorum): A brief review on chemical and technological potential of this Amazonian fruit. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, G.A.B.; Xavier, A.A.O.; Neves, L.C.; Benassi, M.D.T. Caracterização físico-química de polpas de frutos da Amazônia e sua correlação com a atividade anti-radical livre. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2010, 32, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.N.; Guo, M.R. Effects of addition of strawberry juice pre- or postfermentation on physiochemical and sensory properties of fermented goat milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 4978–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Yang, Q.; Su, Y.; Xi, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, B.; Ai, N. Effect of prebiotics on rheological properties and flavor characteristics of Streptococcus thermophilus fermented milk. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minj, J.; Vij, S. Determination of synbiotic mango fruit yogurt and its bioactive peptides for biofunctional properties. Front. Chem. 2025, 12, 1470704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.T.C.; Farinazzo, F.S.; Mauro, C.S.I.; Ferreira, M.D.P.; De Moraes Filho, M.L.; Tarley, C.R.T.; Guergoletto, K.B.; Garcia, S. Effect of Fermentation by Probiotic Bacteria on the Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds from the Fruit of the Juçara Palm (Euterpe edulis Martius). Fermentation 2024, 10, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.d.; Frasao, B.d.S.; Lima, B.R.C.d.C.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Junior, C.A.C. Simultaneous analysis of carbohydrates and organic acids by HPLC-DAD-RI for monitoring goat’s milk yogurts fermentation. Talanta 2016, 152, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadi, W.; Mediani, A.; Benchoula, K.; Wong, E.; Misnan, N.; Sani, N. Characterization of Physicochemical, Biological, and Chemical Changes Associated with Coconut Milk Fermentation and Correlation Revealed by 1H NMR-Based Metabolomics. Foods 2023, 12, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagmignan, A.; Mendes, Y.C.; Mesquita, G.P.; Santos, G.D.; Silva, L.D.; de Souza Sales, A.C.; Castelo Branco, S.J.; Junior, A.R.; Bazán, J.M.; Alves, E.R.; et al. Short-Term Intake of Theobroma grandiflorum Juice Fermented with Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus ATCC 9595 Amended the Outcome of Endotoxemia Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarinis, C.; Verni, M.; Pinto, L.; Rizzello, C.G.; Baruzzi, F. Use of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria for the Fermentation of Legume-Based Water Extracts. Foods 2022, 11, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angmo, K.; Kumari, A.; Savitri; Bhalla, T.C. Probiotic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods and beverage of Ladakh. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarotti, S.; Monteiro, D.; Moretti, M.; Penna, A. Influence of the combination of probiotic cultures during fermentation and storage of fermented milk. Food Res. Int. 2014, 59, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogado, C.; Leandro, E.; Zandonadi, R.; De Alencar, E.; Ginani, V.; Nakano, E.; Habú, S.; Aguiar, P. Enrichment of Probiotic Fermented Milk with Green Banana Pulp: Characterization Microbiological, Physicochemical and Sensory. Nutrients 2018, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.K.; Aguiar-Oliveira, E.; Kamimura, E.S.; Maldonado, R.R. Milk and açaí berry pulp improve sensorial acceptability of kefir-fermented milk beverage. Acta Amaz. 2016, 46, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, R.R.; Buosi, R.E.; Avancini Neto, O.; Araújo, R.D.S.; Deziderio, M.A.; Aguiar De Oliveira, E.; Petrus, R.R.; Kamimura, E.S. Study of the composition of mango pulp and whey for lactic fermented beverages. J. Biotechnol. Biodivers. 2021, 9, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).