Abstract

This study evaluated the fermentation of calabash fruit (Crescentia cujete L.) seeds over 0, 24, 48, and 72 h to produce a daddawa-type condiment. Samples were analysed for proximate composition, antinutritional factors, morphological characteristics, and microbial profiles. Fermentation significantly (p < 0.05) reduced moisture content from 16.37% to 7.67%, carbohydrates from 34.73% to 22.93%, and crude fibre from 7.13% to 3.10%, while protein increased from 12.39% to 21.99%, fat from 24.86% to 28.69%, and ash from 4.02% to 7.62%. Antinutritional factors were also markedly reduced, with phytate decreasing from 2.23 mg/g to 0.24 mg/g, tannins from 0.17 mg/g to 0.03 mg/g, trypsin inhibitors from 3.14 mg/g to 0.17 mg/g, and saponins from 16.86 mg/g to 3.21 mg/g. Morphological analysis revealed fragmented clusters with intergranular pores, and functional amine groups responsible for the characteristic pungent aroma were detected. Bacterial isolates were identified as Bacillus and Lysinibacillus spp., with DNA sequencing confirming Bacillus spp. as the dominant fermenting organisms. These findings demonstrate that fermentation improves the nutritional quality, reduces antinutritional factors, and enhances the functional and culinary potential of calabash fruit seeds as a condiment.

1. Introduction

The challenge of protein-energy-malnutrition (PEM) in developing countries of the world has assumed a worrisome dimension due to a significant increase in cases of low immunity to diseases and poor growth rate in children, with accompanied mortality rate [1]. This development, according to the Global Nutrition Report by Liu [2], identified PEM as one of the leading factors responsible for mortality and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in many developing countries with low-income systems. Given the above, the use of fermentation as an indigenous means of food transformation and protein availability has been well documented. During fermentation, food substances containing nutrients like carbohydrates, proteins, lipids and other bioactive compounds are modified by the influence of microbial and enzymatic growth. This growth often results in value-added products which are antagonistic to other pathogenic microbes in the food.

According to Obafemi [3], a large variety of agri-foods such as cereals, legumes, dairy, roots, and tubers, have been fermented locally to produce value-added products. Furthermore, a significant number of fruit seeds have been fermented to produce condiments that enhance health, increase protein bioavailability, and improve food security in most developing countries [4]. In most African and Asian countries, traditional fermentation plays an important role in processing and preserving food [5,6]. Hence, the fermentation of fruit seeds (which often constitute waste or a medium of environmental pollution) to produce condiments represents a food valorisation approach in a circular economy. Moreover, the microbial flora from these condiments possesses probiotic traits, antibacterial properties, antioxidant properties, peptide production, and other health benefits that offer consumers unique nutritional and health benefits. As the demand to meet the dietary requirements of the growing population in developing countries like Nigeria increases, the need to harness the fermentation potentials of seeds from lesser-known fruits like Calabash fruit becomes imminent.

Calabash fruit (Crescentia cujete L.), obtained from the gourd tree, belongs to the Bignoniaceae family and is indigenous to tropical regions of Central and South America and Sub-Saharan Africa. It is found in Nigeria and other tropical regions of Africa and typically ripens over 6–7 months, with harvesting occurring when fully mature and yellow [7]. These seeds offer medicinal value against certain illnesses [7], especially in folk medicine, and are rich in bioactive compounds such as polyphenols and antioxidants that contribute to human health by modulating oxidative stress and supporting overall well-being [8]. Nutritionally, the seed is rich in protein with values ranging between 8.38 and 18.73%, depending on the source and processing methods [7,9]. Besides protein, the seed is also reportedly rich in fat (17.00–19.96%), which could be potentially used in food and non-food applications including biodiesels [10]. Despite the value of the calabash fruit and seed, its use remains limited due to the presence of antinutrients such as alkaloids, phytate, tannin, and saponin [7,11]. However, these antinutrients are reduced after processing; for example, phytate content in the seed was found to reduce by 75% after fermentation for 5 days. Previous studies documented the possibility of producing condiments from lesser-known seeds such as tamarind [12], prosopis Africana seeds [13,14], watermelon, and pumpkin [4]. However, the effect of fermentation period on the proximate, phytochemical, structural, and molecular characterisation of calabash seeds for condiment production has been sparsely reported. Furthermore, while calabash fruits are traditionally used in food and medicine, few studies have investigated the effect of fermentation on the nutritional, antinutritional, and microbial characteristics of their seeds. This study provides novel insights into fermentation-induced changes in calabash seeds, highlighting their potential as a functional condiment and source of bioactive compounds. Therefore, this study aims to investigate some quality attributes of fermented daddawa-type condiments from calabash fruit seed and assess the species diversity of the microbiota associated with the seed fermentation using molecular characterisation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Extraction and Preparation

Calabash tree fruits (Crescentia cujete L.) were harvested from a local horticultural farm in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Local farmers, who are experienced in determining fruit maturity, identified fully mature fruits, and maturity was further confirmed by a botanist at the Department of Botany, University of Ibadan, where the seeds were also formally identified. The fruits were cracked and allowed to decay for 3 days, after which the flat seeds were extracted by washing off the pulp with water. The extracted seeds were air-dried for 24 h and later dehulled manually and stored in Ziploc bags for subsequent processing.

2.2. Condiment Preparation

The seed preparation into fermented condiment was carried out according to the method reported by Olagunju [12] with little changes. Clean and uninfected seeds were sorted and rinsed again with distilled water, drained and subjected to boiling in a stainless-steel pressure pot for 3 h to enhance easy manual removal of the outer coat after rubbing between the palms. The dehulled seeds were later wrapped in clean banana leaves and cooked for 1 h in demineralised water, then drained and air-dried. The cooled seeds were separated into three portions, put in plastic containers coated with banana leaves that had been cleaned in potable water, then enclosed with additional banana leaves, and allowed fermentation for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. With increased fermentation time, a creamy, mucilaginous slime typical of other fermented condiments was observed with a characteristic strong fragrance of traditional condiments. Fermentation of calabash seeds was carried out using traditional methods without controlled temperature monitoring. Immediately after fermentation, samples were frozen and subsequently freeze-dried for further analyses. Samples intended for microbial analyses (Section 2.8 and Section 2.9) were withdrawn immediately after fermentation and processed without delay to ensure accuracy.

2.3. Proximate Composition

The proximate composition including moisture, ash, fat, fibre, protein, and total carbohydrate of fermented calabash fruit seed (FCS) obtained after 0, 24, 48, and 72 h of fermentation were determined using the AOAC [15] method. The samples were labelled FCS-0, FCS-24, FCS-48, and FCS-72 as fermented calabash fruit seed for 0 h, fermented calabash fruit seed for 24 h, fermented calabash fruit seed for 48 h, and fermented calabash fruit seed for 72 h, respectively.

2.4. Titratable Acidity Determination

The titratable acidity of the samples was determined by dissolving 2 g of ground condiment in 20 mL of distilled water in a 250 mL beaker. The mixture was then filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. A 10 mL aliquot of the filtrate was titrated volumetrically with 0.1 N NaOH using 1% phenolphthalein as an indicator until a slight colour change was observed. The mean titre value was recorded, and the titratable acidity was calculated as a percentage of tartaric acid present in the sample.

2.5. Anti-Nutrient Composition Determination

2.5.1. Tannin

The tannin content of the samples was determined by the procedure of Adebiyi [16]. Briefly, about 1 g of the condiment was mixed with 1% HCl and extracted with methanol at 30 °C for 20 min. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged (5810R; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at 2500× g for 10 min. 1 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 5 mL of vanillin and allowed to stand for 20 min at 30 °C and the absorbance at 500 nm was noted in a spectrophotometer (T70 UV-VIS, PG Coy, Alma Park, UK) where catechin was used as reference tannin.

2.5.2. Phytate

The method presented by Annor [17] was used to deduce the phytic acid of the samples. The sample (4 g) was dissolved in 2% HCl (100 mL) for 3 h and filtered, and the filtrate (25 mL) was added to 5 mL of ammonium thiocyanate indicator in a 25 mL conical flask. The mixture obtained was titrated with 1.95 g FeCl3 standard solution until a characteristic reddish colour was obtained after 5 min of holding time with the addition of 53.5 mL of distilled water to attain the right acid condition.

2.5.3. Trypsin Inhibitory Activity

This activity was assayed by the procedure prescribed by Jafar [18] with some modifications. About 1 mL of inhibitor extract was transferred into three test tubes having 1 mL of trypsin solution and 2 mL of casein solution before being placed carefully into a water bath (Clifton 105499, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Clifton, NJ, USA) at 37 °C for 20 min. This reaction was later interrupted by adding 6 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid which was allowed for 60 min at ambient temperature. The mixture was filtered and its absorbance at 280 nm in a UV spectrophotometer (Jenway, 7305 Bibby Scientfic, Stafforshire, UK) was noted. The blank solution contains 6 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid and a buffer solution.

2.5.4. Saponin

The saponin level of FCS was assessed by the method of Hamzah [19] with some changes. About 5 g of sample was dissolved in 50 mL of 20% aqueous ethanol in a conical flask. The mixture was supplied with heat with intermittent stirring in a water bath for 1 h at 50 °C and filtered through what man filter paper. The residue obtained was leached again with 80 mL of ethanol at 20% and both derivatives were condensed to 40 mL in the water bath at 90 °C. The aqueous layer was separated and recovered by partition with the other layer discarded. The saponin value was obtained and extracted as a percentage of the weight analysed given by the formula.

where A denotes the weight of the empty flask and extract, B denotes the weight of the empty flask, and Ws stands for the weight of sample.

Saponin mg/g = A − B/Ws

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The effect of fermentation on the morphology of the samples was analysed with a scanning electron microscope (Phenom ProX, phenom-World B.V., Eindhoven, The Netherlands). A micro portion of the fermented seed was carefully attached to an aluminium-based sample holder with a carbon adhesive and placed in chamber holes. The SEM micrographs were taken at 1500 magnification, 50 μm scale, a vacuum pressure of 5 × 10−5 Pascal, and 15 KV accelerating voltage.

2.7. Fourier Transform Infra-Red Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The functional groups in the sample were measured by a previously described method [20]. About 3 mg of the condiment sample was added to 150 mg of FTIR-grade potassium bromide (KBR) and flattened into a pellet with a hydraulic press system in a sample holder. The compressed FCS sample was subsequently viewed with FTIR equipment (Spectrum BX Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) within the wavelength of 400 to 4000 cm−1.

2.8. Isolation and Molecular Characterisation of Fermenting Microorganism

Isolation of fermenting microorganisms was performed by taking one gram from the highest fermenting time (72 h) ground into powder and serially diluted with a ringer tablet [21]. Isolation of bacteria was performed with MRS agar prepared based on the manufacturer’s guide. Serially diluted (1 mL) samples (10−6) were transferred into a sterile Petri dish in triplicates, and the molten agar was dispensed aseptically for further anaerobic incubation at 43 °C for 48 h. Sub-culturing was performed until pure culture was obtained. The pure culture was stored in a slant for further analysis.

2.9. Identification of Bacterial Isolates

The characterisation of bacterial isolates was assayed by the method of Cheesbrough [22]. On nutrient agar plates, the cultural traits of the bacterial isolates were visible. Colony size, morphology, surface appearance, opacity, texture, elevation, and colouration were the physical traits identified by visual observation. Biochemical assay included the following. Catalase test: To identify catalase enzyme-producing bacteria by placing individual colonies in hydrogen peroxide solution. Bubble-forming isolates in solution were referred to as catalase positive. Oxidase test: Colonies that developed a purple colour when the culture of test bacterium was flooded with 1% solution of tetramethyl phenylenediamine were observed as oxidase negative colour. Gram’s staining: Gram’s staining was performed by smearing and fixing the heating slide with inoculation, then flooding it with grams of iodine. The stain was then decolourised with 95% ethanol and washing. Finally smearing was counter-stained with safranin for 20 s. Gram-positive bacteria depicted a purple colour while Gram-negative showed pink when examined under an oil immersion lens. Test for starch hydrolysis: This involved streaking isolates aseptically on starch agar and flooding with gram’s iodine. Where the region around the streak was clear, it meant the organism hydrolysed the test starch and the test was positive; otherwise, it was negative.

2.10. DNA Extraction

The DNA extraction was assayed by the method of Yamaguchi [23] with slight variation. Bacteria isolates were cultured for 24 h, conveyed into an Eppendorf tube, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 120 s. The supernatant obtained was expunged with the addition of 600 µL of 2× CTAB buffer mixed with bacterial precipitate for onward incubation at 65 °C for 30 min. The incubated sample was cooled and mixed gently with 500 µL chloroform and gently dissolved by several upturnings of tube. The sample was subsequently centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min with the supernatant mixed with an equal amount of chilled isopropanol for DNA precipitation in an Eppendorf tube. Chilled samples were further frozen for 60 s and centrifuged again under similar condition with the supernatant. The sample was kept in the freezer for 1 h and again centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was cast off, while the obtained pellet was rinsed thoroughly with 70% ethanol aerated for 30 min. The rinsed pellet was resuspended in 100 µL of demineralized water, and the derived DNA value of the fermented sample was measured in a spectrophotometer at 260 nm and 280 nm for the evaluation of genomic purity, which was obtained at 1.8–2.0 for every of the DNA samples

2.11. DNA Electrophoresis and PCR Sequencing

The value and integrity of the obtained DNA sample were assayed using the agarose gel electrophoresis method, which often involves size fractionation on 1.0% agarose gels. The gels were formulated through addition and boiling of 1.0 g agarose in 100 mL of 0.5× TBE buffer solution. The boiled gels were chilled to about 45 °C with 10 µL of 5 mg/mL ethidium bromide formulated and mixed thoroughly in an electrophoresis chamber incorporated with combs. Upon gel solidification, 3 µL of the DNA, 5 µL of sterile demineralised water, and 2 µL of 6× loading dye were added and transferred into the prepared well. Electrophoresis was performed at 80 V for 2 h. The DNA integrity was visually harnessed and captured through a UV light source.

The primer employed was a 16S general primer for bacteria identification. The PCR kits used included 0.5 µL of Big Dye Terminator Mix, 1 µL of 5× sequencing buffer, 1 µL of M13 forward primer with 6.5 µL sterile distilled water, and 1 µL of the PCR, aggregating to a total of 10 µL. The PCR profile for sequencing was a Rapid profile, raising the primary Rapid thermal ramp temperature to 96 °C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles of Rapid thermal ramp to 96 °C for 10 s, Rapid thermal ramp to 50 °C for 5 s, and Rapid thermal ramp to 60 °C for 4 min, followed by Rapid thermal ramp to 4 °C then holding at this temperature. The PCR sequence product was made pure using 2 M Sodium acetate wash techniques. About 10 µL of the PCR product was mixed with 2 M Sodium acetate (1 µL) of pH 5.2, then 20 µL of absolute Ethanol was added and kept at −20 °C for 1 h at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. It was centrifuged and then washed with 70% ethanol and air-dried, re-suspended in 5 µL sterile distilled water, and kept at 4 °C for sequence running. The cocktail mix was combined with 9 µL of formamide with 1 µL of purified sequence aggregating to 10 µL. The samples were loaded on the machine (ABI 3130 xl machine, Hitachi, Japan) and the data in the form of A, C, T, and G were released.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All the data obtained were evaluated via statistical means by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) at a 95% significant confidence level. This was achieved with Statistical Package for Social Statistics SPSS Version 20.0. The results are shown with mean and standard errors using the Duncan range test for the separation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition

Fermentation significantly altered the proximate composition of fermented calabash fruit seed (FCS) as shown in Table 1. On a dry weight basis (dwb), fat (29.73–35.19%), protein (14.83–26.87%), and carbohydrate (14.35–41.53%) were the major components in the raw (FCS-0) and fermented samples (FCS-24-FCS-72). Overall, moisture, fibre, and carbohydrate contents decreased with increasing fermentation time, whereas ash, fat, and protein contents increased. A slight decline in protein was observed after 72 h of fermentation. It is important to note that these values for protein, fat, ash, fibre, and carbohydrate are expressed on a dwb, so the apparent increases in protein, fat, and ash are partly due to concentration effects caused by moisture loss, in addition to microbial biochemical transformations during fermentation. Many traditional African fermented condiments, such as tamarind [12], prosopis Africana seeds [13,14], watermelon, and pumpkin [4], are relatively high in protein on a dry weight basis. However, these condiments are typically used in small amounts for flavour and aroma rather than as a main dietary protein source. For a typical serving of 5–10 g added to a meal, the protein contribution would be approximately 1–2.5 g per serving, serving as a supplementary protein source. The increase in protein content makes the samples an alternative source for managing protein malnutrition concerns, especially in developing countries where animal protein could be expensive. The protein content of the raw sample (FCS-0, 12.39%) was higher than previously reported values for raw calabash fruit seed (8.38–10.42%) [7,9,24]. Among the fermented samples, FCS-24 exhibited a protein content (18.61%) comparable to that reported for calabash fruit seed fermented for five days, according to Suleiman [7]. After three days of fermentation (FCS-72), the protein content remained higher than the average value (approx. 18%) reported by the same author, depending on the fermentation method. The increase in protein content during fermentation may be attributed to several factors. Fermentative microorganisms can synthesise enzymes and degrade other substrates, effectively concentrating protein in the sample [12]. Additionally, the reduction in carbohydrate content during fermentation alters the nutrient ratios, resulting in an apparent increase in protein percentage [25]. Variations in the initial protein content of the seeds and differences in the composition and activity of microbial populations may also contribute to these observed differences. In addition, the observed increase in fat content during fermentation may enhance the caloric value of the samples, making them a more energy-dense food. However, the stability of these lipids should be considered, as improper storage could lead to lipid oxidation and rancidity, potentially affecting flavour and shelf life.

Table 1.

Proximate, pH, TTA and anti-nutritional composition of calabash fruit seed condiment.

3.2. Total Titratable Acidity (TTA)

The TTA of the raw samples was 0.16%, which significantly increased with the fermentation period (Table 1). Samples fermented at 24, 48, and 72 h, and showed higher TTA values of 0.16, 0.31, and 0.36%, respectively, with the later sample having more than double the TTA for the raw sample. The TTA is an important parameter peculiar to fermented foods where its increase is indicative of organic acid production. Previous studies associated this increase in TTA with the production of organic acids due to the continuous metabolic activity by fermenting microorganisms including lactic acid bacteria [26,27]. During fermentation, microbes such as lactic acid bacteria and yeasts typically utilise available carbohydrates and convert them into organic acids (e.g., lactic acid, acetic acid). As fermentation time progresses, more acids accumulate in the medium, resulting in a corresponding rise in titratable acidity. This observation suggests that fermentation was active and that acid production intensified between 24 and 72 h, with the most notable rise occurring after 24 h. A similar increase in the TTA of fermented kidney bean condiment by Ajatta [28] aligns with the present study.

3.3. Anti-Nutritional Constituents

The effect of fermentation on selected antinutrients in calabash fruit seeds showed that progressive fermentation significantly (p < 0.05) reduced phytate, tannin, trypsin inhibitor, and saponin (Table 1). All the antinutrients measured in this study exhibited substantial reductions, ranging from 81% to 95%, after 72 h of fermentation. The trypsin inhibitor showed the highest reduction, followed by phytate, tannin, and saponin. This significant decrease in antinutritional factors may be attributed to a combination of boiling and fermentation processes, and it aligns with earlier reports on tamarind-based fermented condiments [12]. According to Adebiyi [16], boiling can significantly reduce antinutritional factors through thermal inactivation of trypsin inhibitors. Additionally, other studies have attributed these reductions to the enzymatic activity of fermenting microbes. For example, Omer [29] reported that phytase enzymes form complexes with phytic acid, which binds certain minerals, thereby facilitating the reduction in phytic acid content. Similarly, tannase enzymes degrade tannins by forming complexes during fermentation, enhancing their bioavailability. The reduction in these antinutrients may also contribute to the observed increase in protein content of the samples (Table 1), as compounds like tannins form complexes with proteins; their degradation releases previously bound protein molecules, resulting in higher measurable protein levels.

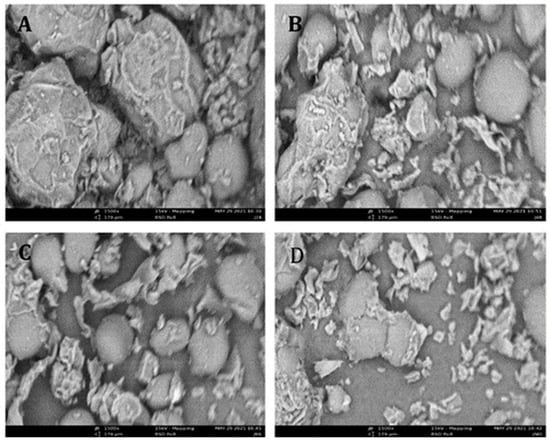

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The scanning electron micrographs revealed morphological changes in the structural framework of the condiments during fermentation (Figure 1A). The unfermented condiment exhibited irregular clusters of cohering structures, agglomerated in varying sizes, and contained relatively larger molecular assemblies. With progressive fermentation, these clusters became disrupted and fragmented into smaller particles, accompanied by widening of the intergranular pores (Figure 1B–D). These structural changes could likely be facilitated by pre-treatment operations such as washing, boiling, and dehulling, which enhanced microbial access during fermentation, as reported by Ojewumi [30]. The formation of wider pores also indicates improved removal of seed coats, which may contribute to the observed reduction in antinutritional factors (Table 1) by promoting leaching where applicable. Similar observations of pore formation in fermented Bambara groundnut condiments [16] further support these findings.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron micrographs of fermented calabash fruit seed. (A) Fermented calabash fruit seed for 0 h; (B) fermented calabash fruit seed for 24 h; (C) fermented calabash fruit seed for 48 h; and (D) fermented calabash fruit seed for 72 h 3.5 FTIR.

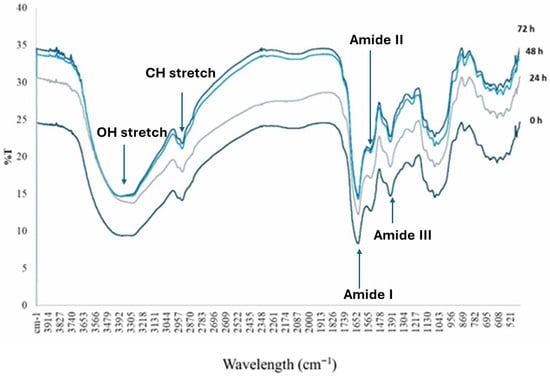

3.5. FTIR

The FTIR spectra of raw and fermented samples, presented in Figure 2, revealed functional groups associated with both general seed components and protein structure. Broad absorption bands were observed in the 3500–2800 cm−1 region, with peaks at 3392 and 2957 cm−1 corresponding to the O–H stretching of hydroxyl groups and C–H stretching of aliphatic compounds, respectively. These bands reflect the presence of carbohydrates, water, and other polar compounds, and their slight reduction in intensity after fermentation may indicate changes in hydrogen bonding and the partial utilisation of these compounds by fermenting microorganisms. In the 1750–1400 cm−1 region, peaks at 1652–1350 cm−1 corresponded to the N–H stretching and C=O stretching vibrations of amide groups, indicative of protein presence [31,32]. Fermentation caused these amides I (1652 cm−1), II (1560 cm−1), and III (1350 cm−1) bands to broaden and decrease in intensity compared with raw seeds, reflecting partial protein denaturation and hydrolysis. Similarly, a peak at 1070 cm−1 in the 1100–1000 cm−1 region was associated with the C–H stretching of aromatic aldehydes and N–H bending, consistent with protein breakdown and generation of smaller peptide fragments. Fermentation time further influenced protein-related spectral features. Samples fermented for 24 h retained relatively sharper amide bands, whereas those fermented for 48 and 72 h showed slight peak shifts and progressive broadening, indicating progressive disruption of secondary protein structures and increased heterogeneity in peptide environments. These changes were more pronounced in the amide I region, which is particularly sensitive to alterations in protein secondary structural elements such as α-helix, β-turn, β-sheet, and random coil conformations [33]. Overall, the structural modifications observed in the FTIR spectra align with the increases in protein content reported in Table 2, suggesting that fermentation not only alters protein structure through enzymatic hydrolysis but may also increase the relative concentration of protein fractions through the partial degradation of other seed components.

Figure 2.

FTIR Spectra of fermented calabash fruit seed. 0 h fermented calabash fruit seed for 0 h; 24 h: fermented calabash fruit seed for 24 h; 48 h: fermented calabash fruit seed for 48 h; 72 h: fermented calabash fruit seed for 72 h.

Table 2.

DNA sequencing of bacterial isolates from fermented condiment after 72 h.

3.6. Biochemical and Molecular Analysis

The biochemical and morphological of 15 bacterial isolates recovered from the fermented calabash seeds displayed diverse morphological and biochemical characteristics. All isolates were rod-shaped, and the majority were Gram-positive and catalase-positive, with most producing spores. Oxidase activity varied among the isolates, reflecting metabolic diversity. Starch hydrolysis was observed in several Bacillus isolates, while the Gram-negative isolates (Klebsiella and Providencia species) showed additional differences in anaerobic growth. Based on these phenotypic traits, the isolates were provisionally identified as Bacillus, Lysinibacillus, Klebsiella, and Providencia species, with Bacillus and Lysinibacillus dominating the fermentation environment. This diversity suggests multiple microbial strains contributed synergistically to substrate degradation during fermentation.

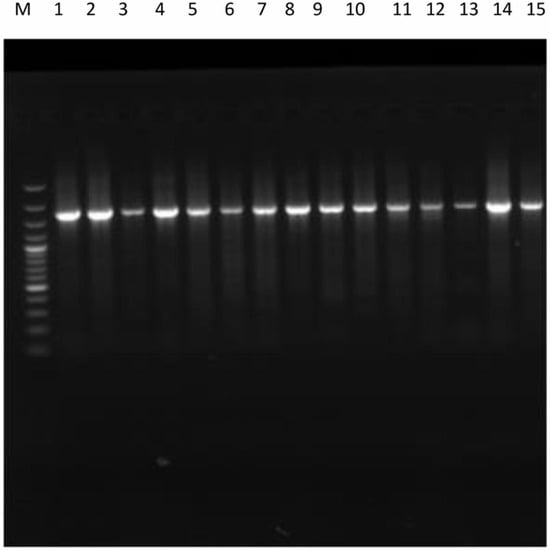

Molecular identification using 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed to confirm the provisional identification of the isolates. PCR amplification was attempted for all 15 isolates, and agarose gel electrophoresis showed visible bands for all samples, although band intensity varied (Figure 3). Five isolates (A–E) produced strong and distinct bands that yielded high-quality sequences suitable for reliable identification (Table 2). Faint PCR bands were observed for some isolates presumptively identified as Klebsiella and Providencia, but the resulting sequences were not sufficient enough for reliable taxonomic assignment and were therefore excluded from definitive molecular identification. Sequence analysis confirmed that these isolates belonged exclusively to Bacillus spp. (A, B, E) and Lysinibacillus spp. (C, D), which are commonly associated with traditional African fermented seed condiments [12,34,35]. The predominance of Bacillus species is consistent with their selective advantage during the fermentation of thermally pretreated seeds, as spore-forming, heat-resistant organisms survive cooking and dominate the microbial community [36]. Lysinibacillus fusiformis likely contributed to complementary enzymatic activities supporting the hydrolysis of proteins and carbohydrates. These observations align with FTIR results (Figure 2), where changes in amide I, II, and III bands indicated progressive protein denaturation and hydrolysis. The presence of these microorganisms has important functional implications. Bacillus species are known to produce proteases, amylases, lipases, cellulases, phytases, and nattokinase, facilitating hydrolysis of proteins and carbohydrates, reduction in antinutritional factors, and enhancement of digestibility [37]. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that some members of the genus Bacillus (e.g., B. cereus) are potentially pathogenic, and strain-level identification and toxin profiling were beyond the scope of this study [38]. Consequently, while the observed microbial population reflects patterns reported for traditional spontaneous fermentations, further molecular and toxicological studies are required to fully establish the safety of the fermented product prior to large-scale or commercial application.

Figure 3.

PCR amplification of the bacterial 16srRNA PCR gene of bacterial isolates.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated fermentation-induced changes in the nutritional, antinutritional, and microbial characteristics of calabash fruit seeds. Overall, fermentation of calabash fruit seeds significantly enhanced their nutritional profile, with increases in protein, fat, and ash content. Concurrently, fermentation effectively reduced antinutritional factors, including phytic acid, tannins, trypsin inhibitors, and saponins. Morphological analysis revealed fragmentation and the formation of granular structures, while functional group analysis identified carbonyl, carboxylic, and amine groups, which likely contributed to the characteristic ammoniacal aroma of the fermented product. Molecular characterisation confirmed that Bacillus and Lysinibacillus species dominated the fermentation process. Based on typical serving sizes of 5 g of dry condiment, a portion could contribute approximately 1.1 g of protein and 1.5 g of fat per meal, highlighting its potential as a functional flavouring ingredient. While the microbial community reflects patterns observed in traditional spontaneous fermentations, further molecular and toxicological studies are required to fully establish product safety. Additionally, sensorial evaluation is necessary to validate organoleptic and culinary suitability. These findings underscore the nutritional, biochemical, and microbial significance of fermenting calabash fruit seeds, highlighting their potential as a functional ingredient in local culinary applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.O. and M.G.; methodology, A.O.O. and M.G.; validation, S.A.O., A.O.O. and M.G.; formal analysis, A.O.O. and M.G.; investigation, M.G.; resources, A.O.O.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.O., A.O.O. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, S.A.O., A.O.O. and M.G.; supervision, A.O.O. and S.A.O.; project administration, A.O.O. and S.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge Yinusa Babarinde of the Department of Food Technology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria posthumously, for his technical assistance, who passed on shortly after the laboratory completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kurmi, A.; Jayswal, D.; Saikia, D.; Lal, N. Current Perspective on Malnutrition and Human Health. In Nano-Biofortification for Human and Environmental Health; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Jiang, S.; Han, L.; Kang, Z.; Shan, L.; Liang, L.; Wu, Q. Evolving patterns of nutritional deficiencies burden in low-and middle-income countries: Findings from the 2019 global burden of disease study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obafemi, Y.D.; Ajayi, A.A.; Adebayo, H.A.; Oyewole, O.A.; Olumuyiwa, E.O. The role of indigenous Nigerian fermented agrifoods in enhancing good health and well˗being. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpo, N.; Alalade, O.; Dawi, A.; Tahir, Z. Quality Attributes of Condiments Made from Some Locally Underutilized Seeds. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. DUJOPAS 2022, 8, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obafemi, Y.D.; Oranusi, S.U.; Ajanaku, K.O.; Akinduti, P.A.; Leech, J.; Cotter, P.D. African fermented foods: Overview, emerging benefits, and novel approaches to microbiome profiling. npj Sci. Food 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, O.C. African traditional foods and sustainable food security. Food Control 2023, 145, 109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, B. Effects of fermentation on the nutritional status of Crescentia cujete L. seed and its potentiality as aqua feedstuff. Animal Res. Int. 2019, 16, 3207–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, A.L.; Sevilla, U.T.A.; Tsai, P.W. Pharmacological Activities of Bioactive Compounds from Crescentia cujete L. Plant–A Review. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 13, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Obayomi, M.; Suleiman, B.; Bashir, A. Proximate and anti-nutrient composition of Afzelia africana and Crescentia cujete seeds. Ife J. Agric. 2019, 31, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Awulu, J.; Ogbeh, G.; Asawa, N. Comparative analysis of biodiesels from calabash and rubber seeds oils. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2015, 4, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbusola, E.M. Nutritional and antinutritional composition of calabash and bottle gourd seed flours (var Lagenaria siceraria). J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, O.F.; Ezekiel, O.O.; Ogunshe, A.O.; Oyeyinka, S.A.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A. Effects of fermentation on proximate composition, mineral profile and antinutrients of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seed in the production of daddawa-type condiment. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 90, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, M.A.; Oyeyiola, G.; Kolawole, F.L. Comparative study of physicochemical analysis of prosopis africana seeds fermented with different starter cultures. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 9, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, M.; Oyeyiola, G.; Omojasola, P.; Kolawole, F.; Oyeyinka, S.; Abdulsalam, K.; Sanni, A. Effect of Softening Agents on The Chemical and Anti-Nutrient Compositions of Fermented Prosopis africana Seeds. Carpathan J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Association of Official Analytical Chemists Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 18th ed.; AOAC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2010; Volume 3, pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Kayitesi, E. Assessment of nutritional and phytochemical quality of Dawadawa (an African fermented condiment) produced from Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea). Microchem. J. 2019, 149, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annor, G.A.; Debrah, K.T.; Essen, A. Mineral and phytate contents of some prepared popular Ghanaian foods. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafar, L.K.; Lekha, M.; Chandrashekharaiah, K. Studies on protease inhibitory peptides from the seeds of Tamarindus indica. J. Innov. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 4, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, R.; Makun, H.; Egwim, E. Phytochemical screening and invitro antioxidant activity of methanolic extract of selected Nigerian vegetables. Asian J. Basis ApSci. 2014, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Singh, S.; Adebola, P.O.; Gerrano, A.S.; Amonsou, E.O. Physicochemical properties of starches with variable amylose contents extracted from bambara groundnut genotypes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 133, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.G.; Krieg, N.R.; Sneath, P.H.; Staley, J.T.; Williams, S.T. Bergey’s Manual of Determinate Bacteriology; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cheesbrough, M. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Sasaki, K.; Kidachi, Y.; Shirama, K.; Kiyokawa, S.; Ryoyama, K.; Matsuoka, T.; Hino, A.; Umetsu, H.; Kamada, H. Detection of recombinant DNA in genetically modified soybeans and tofu. Jpn. J. Food Chem. Safety 2000, 7, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ejelonu, B.; Lasisi, A.; Olaremu, A.; Ejelonu, O. The chemical constituents of calabash (Crescentia cujete). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 19631–19636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, C.; Noetzold, H.; Bley, T.; Henle, T. Proximate composition and digestibility of fermented and extruded uji from maize–finger millet blend. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 37, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, H.; Ibe, S.; Odu, N.; Oyeyipo, O. Processing and characteristics of African breadfruit tempe-fortified lafun. Nat. and Sci. 2013, 11, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Ayinla, S.O.; Sanusi, C.T.; Akintayo, O.A.; Oyedeji, A.B.; Oladipo, J.O.; Akeem, A.O.; Badmos, A.H.A.; Adeloye, A.A.; Diarra, S.S. Chemical and physicochemical properties of fermented flour from refrigerated cassava root and sensory properties of its cooked paste. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajatta, M.; Olaoye, B.; Enujiugha, V. Biochemical changes during fermentation of kidney beans for production of condiment. In Proceedings of the 4th Regional Food Science and Technology Summit (REFOSTS), Akure, Nigeria, 6–7 June 2018; pp. 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, M.A.M.; Mohamed, E.A.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Yagoub, A.E.A.; Babiker, E.E. Effect of different processing methods on anti-nutrients content and protein quality of improved lupin (Lupinus albus L.) cultivar seeds. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 4, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojewumi, M.E.; Omoleye, J.A.; Ajayi, A.A.; Obanla, O.M. Molecular Compositions and Morphological Structures of Fermented African Locust Bean Seed (Parkia biglobosa). Lett. Appl. NanoBioScience 2021, 11, 3111–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Sun, L.; Zhao, G. Study on secondary structure of meat protein by FTIR. Food Ferment. Ind. 2015, 41, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, X.; Yang, H.; Qin, S.; Hong, L.; Pu, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J. Study of the molecular structure of proteins in fermented Maize-Soybean meal-based rations based on FTIR spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Hu, S.; Jia, J.; Tan, W.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Duan, X. Effects of short-term fermentation with lactic acid bacteria on the characterization, rheological and emulsifying properties of egg yolk. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademola, O.; Adeyemi, T.; Ezeokoli, O.; Ayeni, K.; Obadina, A.; Somorin, Y.; Omemu, A.; Adeleke, R.; Nwangburuka, C.; Oluwafemi, F.; et al. Phylogenetic analyses of bacteria associated with the processing of iru and ogiri condiments. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Jang, Y.-H.; Hamada, M.; Ahn, J.-H.; Weon, H.-Y.; Suzuki, K.-I.; Whang, K.-S.; Kwon, S.-W. Lysinibacillus chungkukjangi snov., isolated from Chungkukjang, Korean fermented soybean food. J. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Kwarteng, J.; Parkouda, C.; Adewumi, G.A.; Ouoba, L.I.I.; Jespersen, L. Technologically relevant Bacillus species and microbial safety of West African traditional alkaline fermented seed condiments. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopikrishna, T.; Kumar, H.K.S.; Perumal, K.; Elangovan, E. Impact of Bacillus in fermented soybean foods on human health. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahaotu, I.; Anyogu, A.; Njoku, O.; Odu, N.; Sutherland, J.; Ouoba, L. Molecular identification and safety of Bacillus species involved in the fermentation of African oil beans (Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth) for production of Ugba. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 162, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.