Biopesticide Production from Trichoderma harzianum by Solid-State Fermentation: Impact of Drying Process on Spore Viability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms and Inoculum Preparation

- x: number of microorganisms per gram of dry matter;

- a: total number of spores counted;

- b: dilution factor (100, 50, or 25 depending on the sample);

- 104: factor to scale to 1 mL of suspension;

- c: volume of the stock suspension in mL;

- d: mass of the dry sample in grams.

2.2. Solid-State Fermentation (SSF)

2.3. Enzyme Assay

2.4. Spore Quantification Produced on SSF

2.5. Spores Viability Under Different Stock Conditions

3. Results

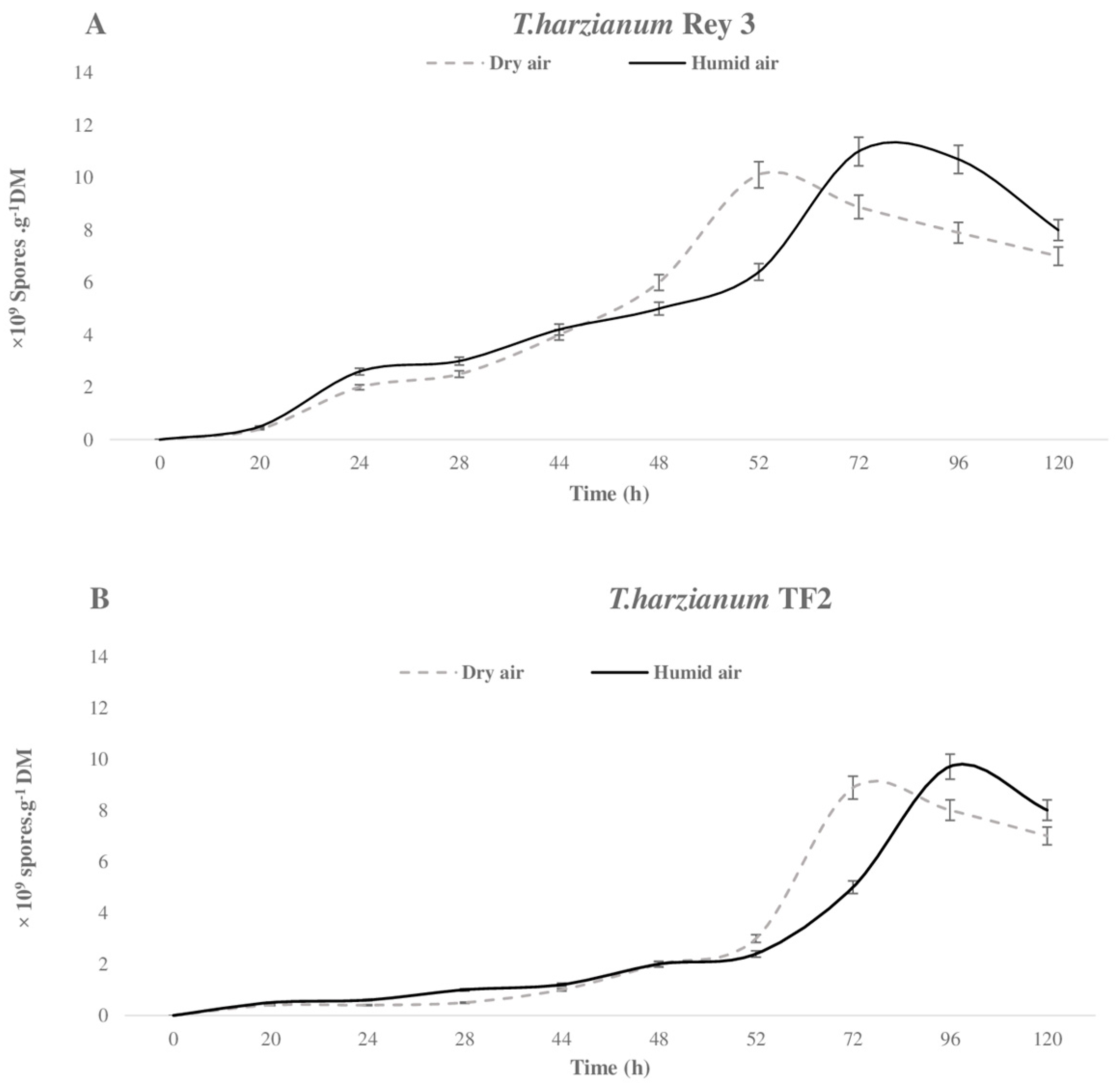

3.1. Effect of Dry-Air Application on Spore Production

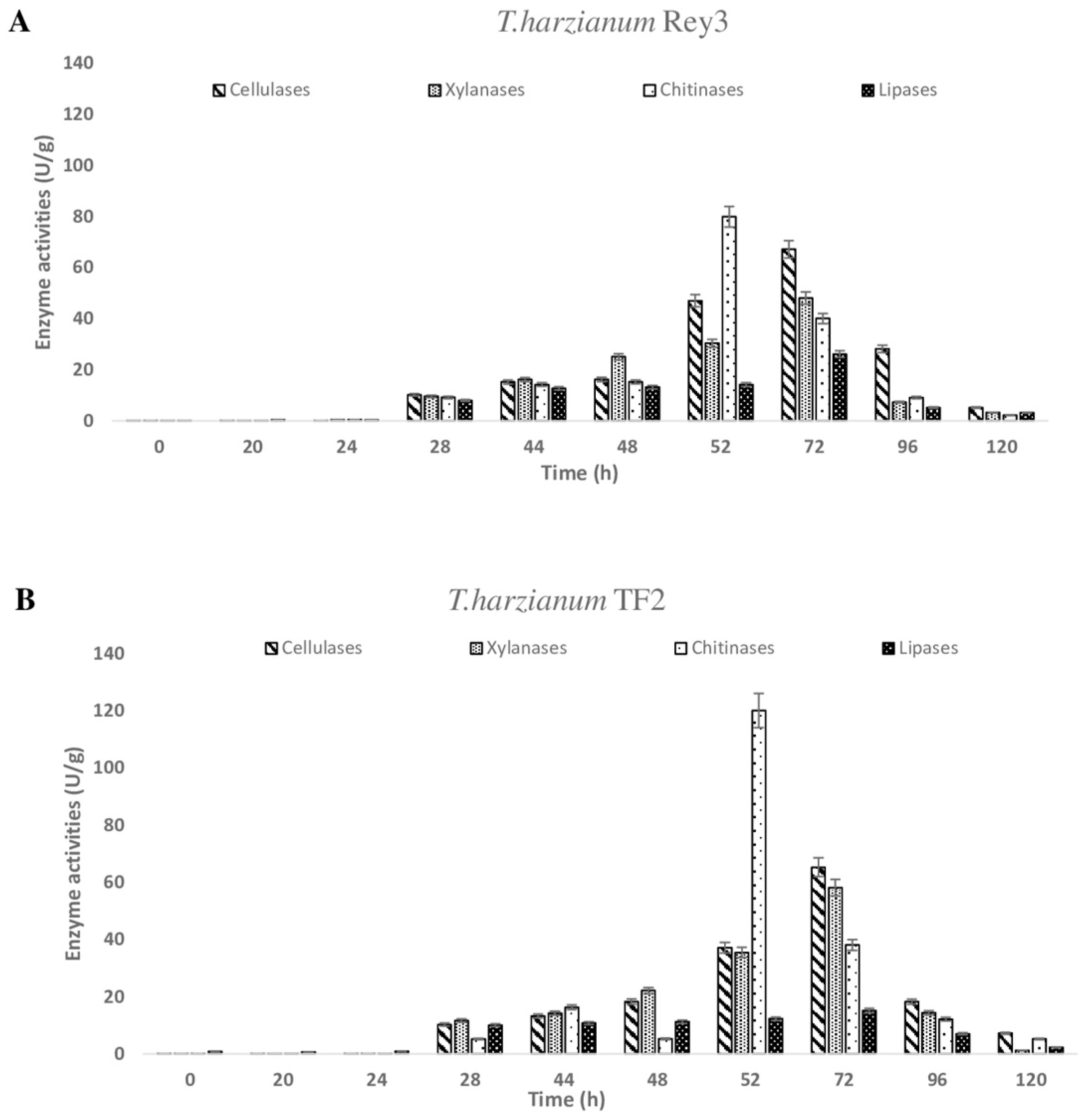

3.2. Determination of Enzyme Activities During Solid-State Fermentation

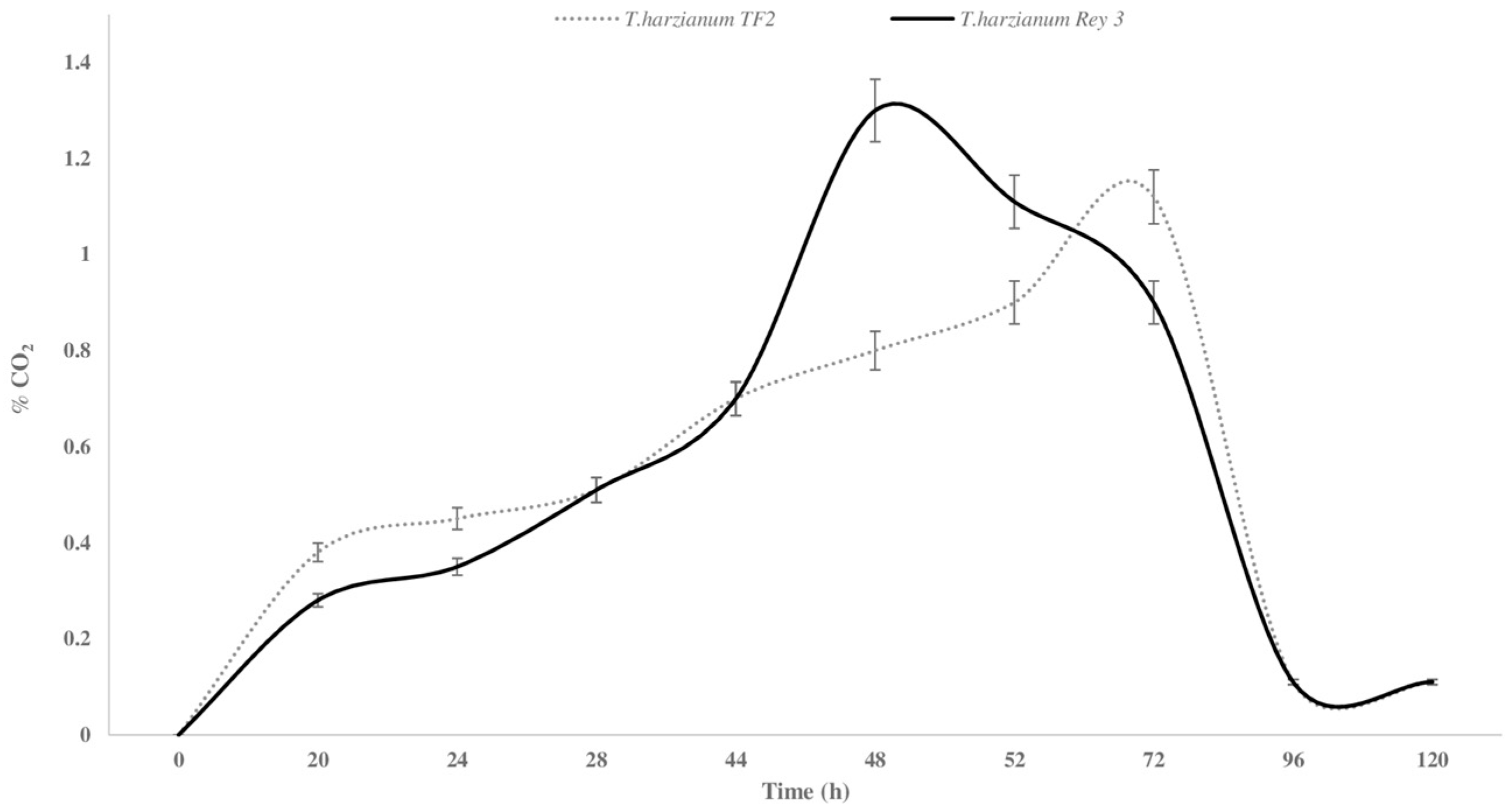

3.3. CO2 Evolution During SSF

3.4. Effect of Conservation Methods on Spore Viability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSF. | Solid-state fermentation |

| UN | United Nations |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| BCA | biological control agents |

| PDA | potato dextrose agar |

| IMBE | Institute Mediterranean of Biodiversity and Marine Ecology and Continental |

| DM | Dry material |

References

- Mattedi, A.; Sabbi, E.; Farda, B.; Djebaili, R.; Mitra, D.; Ercole, C.; Cacchio, P.; Del Gallo, M.; Pellegrini, M. Solid-State Fermentation: Applications and Future Perspectives for Biostimulant and Biopesticides Production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swilling, M. Introduction: Change in the Age of Sustainability. In The Age of Sustainability: Just Transitions in a Complex World, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–34. ISBN 9780429057823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Toward a Sustainable Agriculture Through Plant Biostimulants: From Experimental Data to Practical Applications. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.A.; Meng, L.; Xia, S.; Raza, M.F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H. Isolation, fermentation, and formulation of entomopathogenic fungi virulent against adults of Diaphorina citri. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4040–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganassi, S.; Di Domenico, C.; Altomare, C.; Samuels, G.J.; Grazioso, P.; Di Cillo, P.; Pietrantonio, L.; De Cristofaro, A. Potential of fungi of the genus Trichoderma for biocontrol of Philaenus spumarius, the insect vector for the quarantine bacterium Xylella fastidosa. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.; Barrena, R.; Artola, A.; Sánchez, A. Current developments in the production of fungal biological control agents by solid-state fermentation using organic solid waste. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 655–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.M.; Aguilar, C.N.; Haridas, M.; Sabu, A. Production of bio-fungicide, Trichoderma harzianum CH1 under solid-state fermentation using coffee husk. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracquadanio, C.; Quiles, J.M.; Meca, G.; Cacciola, S.O. Antifungal Activity of Bioactive Metabolites Produced by Trichoderma asperellum and Trichoderma atroviride in Liquid Medium. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.A.; Kasem, L.M.; Attaby, H.S.; Khalil, N.M.; El Amir, D.A.; Diab, M.R.; El-Baghdady, M.M.; Radwan, K.H.; Ibrahim, A.E. Molecular and genetic adaptations of heat-treated Trichoderma harzianum for enhanced stress resilience and biocontrol efficiency. Ann. Microbiol. 2025, 75, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz-Quiroz, R.; Robledo-Padilla, F.; Aguilar, C.N.; Roussos, S. Forced Aeration Influence on the Production of Spores by Trichoderma strains. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz-Quiroz, R.; Roussos, S.; Aguilar, C.N. Production of a biological control agent: Effect of a drying process of solid-state fermentation on viability of Trichoderma spores. Int. J. Green Tech. 2018, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, A.O.; Asevedo, E.A.; Souza Filho, P.F.; Santos, E.S.d. Extraction of Cellulases Produced through Solid-State Fermentation by Trichoderma reesei CCT-2768 Using Green Coconut Fibers Pretreated by Steam Explosion Combined with Alkali. Biomass 2024, 4, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loera-Corral, O.; Porcayo-Loza, J.; Montesinos-Matias, R.; Favela-Torres, E. Production of conidia by the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae using solid-state fermentation. In Microbial-Based Biopesticides. Methods in Molecular Biology; Glare, T., Moran-Diez, M., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1477, pp. 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Silva, J.; Mascarin, G.M.; Lopes, R.B.; Freire, D.M.G. Production of dried Beauveria bassiana conidia in packed-column bioreactor using agro-industrial palm oil residues. Biochem. Eng J. 2023, 198, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiza, N.; Moral-Vico, J.; Sánchez, A.; Oviedo, E.R.; Gea, T. Solid-State Fermentation from Organic Wastes: A New Generation of Bioproducts. Processes 2022, 10, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.-Z. Advances in Porous Characteristics of the Solid Matrix in Solid-State Fermentation. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Pandey, A., Larroche, C., Soccol, C.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 19–29. ISBN 9780444639905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velvizhi, G.; Jacqueline, P.J.; Shetti, N.P.; K, L.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Emerging trends and advances in valorization of lignocellulosic biomass to biofuels. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y. Optimization of Verticillium lecanii spore production in solid-state fermentation on sugarcane bagasse. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 82, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Pérez, J.; López-Pérez, M.; Viniegra-González, G.; Loera, O. Solid-state fermentation of Bacillus thuringiensis var kurstaki HD-73 maintains higher biomass and spore yields as compared to submerged fermentation using the same media. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzumanov, T.; Jenkins, N.; Roussos, S. Effect of aeration and substrate moisture content on sporulation of Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum. Process. Biochem. 2005, 40, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-González, F.; Figueroa-Montero, A.; Saucedo-Castañeda, G.; Loera, O.; Favela-Torres, E. Addition of spherical-style packing improves the production of conidia by Metarhizium robertsii in packed column bioreactors. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Hernández, O.; Ríos-Lira, A.; Pantoja-Pacheco, Y.V.; Jiménez-García, J.A.; Vázquez-López, J.A.; Hernández-González, S. Increase of Trichoderma harzianum Production Using Mixed-Level Fractional Factorial Design. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, D.; Alias, C.; Peron, G.; Ribaudo, G.; Gianoncelli, A.; Savino, S.; Boureghda, H.; Bouznad, Z.; Monti, E.; Gobbi, E. Solid-State Fermentation of Trichoderma spp.: A New Way to Valorize the Agricultural Digestate and Produce Value-Added Bioproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 3994–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alananbeh, K.M.; Alkfoof, R.; Muhaidat, R.; Massadeh, M. Production of Xylanase by Trichoderma Species Growing on Olive Mill Pomace and Barley Bran in a Packed-Bed Bioreactor. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Tahon, M.A.; Isaac, G.S. Anticancer and antifungal efficiencies of purified chitinase produced from Trichoderma viride under submerged fermentation. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 66, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, R.; Regus, F.; Claeys-Bruno, M.; Farnet Da Silva, A.-M.; Orsière, T.; Laffont-Schwob, I.; Boudenne, J.-L.; Dupuy, N. Statistical Experimental Design as a New Approach to Optimize a Solid-State Fermentation Substrate for the Production of Spores and Bioactive Compounds from Trichoderma asperellum. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldoni, D.B.; Antoniolli, Z.I.; Mazutti, M.A.; Jacques, R.J.S.; Dotto, A.C.; de Oliveira Silveira, A.; Ferraz, R.C.; Soares, V.B.; de Souza, A.R.C. Chitinase production by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 using solid state fermentation. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawaty, R.; Halifah, P.; Hartati, H.; Maulana, Z.; Salleh, M.M. Optimization of Chitinase Production by Trichoderma virens in Solid State Fermentation Using Response Surface Methodology. Mater. Sci. Forum 2019, 967, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xing, J.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Liu, G.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, J. Review of research progress on the production of cellulase from filamentous fungi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Sheng, Y.; Tai, Y.; Ding, J.; He, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, B.; He, J.; Ren, A.; He, Q. Mechanism of improved cellulase production by Trichoderma reesei in water-supply solid-state fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 419, 132017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legodi, L.M.; La Grange, D.C.; van Rensburg, E.L.J. Production of the Cellulase Enzyme System by Locally Isolated Trichoderma and Aspergillus Species Cultivated on Banana Pseudostem during Solid-State Fermentation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Tewari, R.; Soni, R.; Soni, S.K. Production of cellulases from Aspergillus niger NS-2 in solid state fermentation on agricultural and kitchen waste residues. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boondaeng, A.; Keabpimai, J.; Trakunjae, C.; Vaithanomsat, P.; Srichola, P.; Niyomvong, N. Cellulase production under solid-state fermentation by Aspergillus sp. IN5: Parameter optimization and application. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, R.; Medina-Morales, M.A.; Rodrìguez, R.; Farruggia, B.; Picó, G.; Aguilar, C.N. Production of a xylanase by Trichoderma harzianum (Hypocrea lixii) in solid-state fermentation and its recovery by an aqueous two-phase system. Can. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 2, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, Z.; Bettache, A.; Boucherba, N.; Amghar, Z.; Benallaoua, S. Optimization of xylanase production by newly isolated strain Trichoderma afroharzianum isolate AZ 12 in solid state fermentation using response surface methodology. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2020, 54, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, L.; Montero, G.; Stoytcheva, M.; Cervantes, L.; Gochev, V. Comparison of the performances of four hydrophilic polymers as supports for lipase immobilisation. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2014, 28, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, C.-H.; Xu, C.-J.; Lin, G.-C. Purification and partial characterization of a lipase from Antrodia cinnamomea. Process. Biochem. 2006, 41, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodman, H.R.; Noureddini, H. Effects of intermittent mechanical mixing on solid-state fermentation of wet corn distillers grain with Trichoderma reesei. Biochem. Eng. J. 2013, 81, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancelista, A.; Tril, U.; Stempniewicz, R.; Piegza, M.; Szczech, M.; Witkowska, D. Application of lignocellulosic waste materials for the production and stabilization of Trichoderma biomass. Pol. J. Environ. Studies 2013, 22, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Narwade, J.D.; Odaneth, A.A.; Lele, S.S. Solid-state fermentation in an earthen vessel: Trichoderma viride spore-based biopesticide production using corn cobs. Fungal Biol. 2023, 127, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Xiang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Bai, G.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Turning Waste into Wealth: Utilizing Trichoderma’s Solid-State Fermentation to Recycle Tea Residue for Tea Cutting Production. Agronomy 2024, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, R.; Molinet, J.; Mitropoulou, G.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Dupuy, N.; Masmoudi, A.; Roussos, S. From flasks to single used bioreactor: Scale-up of solid state fermentation process for metabolites and conidia production by Trichoderma asperellum. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 252, 109496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboué, Q.; Rébufa, C.; Dupuy, N.; Roussos, S.; Bombarda, I. Solid state fermentation pilot-scaled plug flow bioreactor, using partial least square regression to predict the residence time in a semicontinuous process. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maïga, Y.; Carboué, Q.; Hamrouni, R.; Tranier, M.-S.; Ben Menadi, Y.; Roussos, S. Development and Evaluation of a Disposable Solid-State Culture Packed-Bed Bioreactor for the Production of Conidia from Trichoderma asperellum Grown Under Water Stress. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 3223–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Nolasco, A.; Castillo-Araiza, C.O.; Huerta-Ochoa, S.; Reyes-Arreozola, M.I.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J.; Prado-Barragán, L.A. Evaluating the Performance of Yarrowia lipolytica 2.2ab in Solid-State Fermentation under Bench-Scale Conditions in a Packed-Tray Bioreactor. Fermentation 2024, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasone, K.K.; Peterson, S.W.; Jong, S.-C. Preservation and distribution of fungal cultures. In Biodiversity of Fungi: Inventory and Monitoring Methods; Muller, G.M., Bills, G.F., Foster, M.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berikten, D. Survival of thermophilic fungi in various preservation methods: A comparative study. Cryobiology 2021, 101, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bedak, O.A.; Sayed, R.M.; Hassan, S.H.A. A new low-cost method for long-term preservation of filamentous fungi. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 22, 101417, Erratum in Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 36, 101857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolka, L. Methods of Cryopreservation in Fungi. In Laboratory Protocols in Fungal Biology: Current Methods in Fungal Biology; Gupta, V.K., Tuohy, M.G., Ayyachamy, M., Turner, K.M., O’Donovan, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

) and humid air (

) and humid air ( ) during the SSF of T. harzianum Rey 3 (A) and T. harzianum TF2 (B).

) during the SSF of T. harzianum Rey 3 (A) and T. harzianum TF2 (B).

) and humid air (

) and humid air ( ) during the SSF of T. harzianum Rey 3 (A) and T. harzianum TF2 (B).

) during the SSF of T. harzianum Rey 3 (A) and T. harzianum TF2 (B).

| Treatment | Total Spores (Spores/g DM) | Viable Spores (Spores/g DM) | Viable Spores (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. harzianum Rey 3 | |||

| PDA | 9.6 × 109 | 3.1 × 109 | 32.6 |

| Lyophilized | 1.4 × 108 | 4.2 × 107 | 15.17 |

| Frozen | 6.8 × 109 | 2.0 × 108 | 2.91 |

| Dried | 9.3 × 109 | 2.7 × 109 | 28.98 |

| T. harzianum TF2 | |||

| PDA | 8.4 × 1010 | 3.2 × 1010 | 38.3 |

| Lyophilized | 4.7 × 108 | 7.4 × 107 | 15.6 |

| Frozen | 4.9 × 108 | 3.1 × 107 | 6.4 |

| Dried | 1.5 × 1010 | 5.1 × 109 | 33.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hamrouni, R.; Walker, V.; Farnet-Da Silva, A.-M.; Bresson, H.; Roussos, S.; Dupuy, N. Biopesticide Production from Trichoderma harzianum by Solid-State Fermentation: Impact of Drying Process on Spore Viability. Fermentation 2026, 12, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010019

Hamrouni R, Walker V, Farnet-Da Silva A-M, Bresson H, Roussos S, Dupuy N. Biopesticide Production from Trichoderma harzianum by Solid-State Fermentation: Impact of Drying Process on Spore Viability. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamrouni, Rayhane, Vincent Walker, Anne-Marie Farnet-Da Silva, Hervé Bresson, Sevastianos Roussos, and Nathalie Dupuy. 2026. "Biopesticide Production from Trichoderma harzianum by Solid-State Fermentation: Impact of Drying Process on Spore Viability" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010019

APA StyleHamrouni, R., Walker, V., Farnet-Da Silva, A.-M., Bresson, H., Roussos, S., & Dupuy, N. (2026). Biopesticide Production from Trichoderma harzianum by Solid-State Fermentation: Impact of Drying Process on Spore Viability. Fermentation, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010019