Abstract

Garden waste is a solid waste produced by plant littering or pruning. Improper disposal can easily pollute the environment. The addition of bulking agents (BAs) can improve the efficiency of organic waste composting. In this study, garden waste and dairy manure were used as raw materials, and easily available and recyclable branches were used as bulking agents to realize the synergistic resource utilization of the two. Three treatments were set up in the experiment, and 10% crushed branches, 1 cm branches, and 3 cm branches were added to the raw materials, respectively. The results showed that compared with the control group (adding crushed branches), the addition of 1 cm branches and 3 cm branches increased the cellulose degradation rate by 13.16–13.33% and the hemicellulose degradation rate by 18.24–23.86%. The monitoring results of CO2 release showed that the cumulative CO2 release of the treatment groups with 1 cm and 3 cm branches was 78.56 L and 102.17 L, respectively, which was significantly higher than that of the crushed branches (67.24 L), indicating that the addition of 1 cm and 3 cm branches increased microbial activity and degradation efficiency. Microbial diversity analysis further showed that in the treatment group with 1 cm branches, the number of nodes in the co-occurrence network increased by 24.11% and 2.84%, respectively, compared with the crushed branches and 3 cm branches, and the number of edges increased by 44.25% and 19.72%, forming the most abundant and complex microbial community, which verified its promotion effect on the composting process from the microbial level. In summary, this study recommends the use of branches with a particle size of 1 cm as BAs for garden waste composting.

1. Introduction

With the construction of ecologically civilized cities, the coverage of urban green space has increased significantly, and a large amount of garden waste has been generated. China produces about 350 million tons of garden waste every year [1]. Garden waste refers to plant residues such as dead branches and fallen leaves produced by natural littering or artificial pruning during the growth of garden plants. Garden waste is rich in organic matter and nutrient elements, among which cellulose accounts for about 40–60%, hemicellulose accounts for about 15–30%, and lignin accounts for 10–25%. It has broad prospects for resource utilization [2]. However, traditional garden waste disposal methods (incineration or landfill) will aggravate soil, water, and air pollution. On the one hand, they cause environmental pollution by emitting a large amount of greenhouse gases into the air, and on the other hand, they also represent a waste of resources and economic value [3]. Aerobic composting is a complex biological process driven by a series of microorganisms [4] and is an economical and environmentally friendly method for the treatment of agricultural and forestry wastes. During composting, microorganisms decompose organic matter into small molecular substances and release heat, and later polymerize into stable humus substances. Composting products are rich in N, P, and K nutrients and can be used as fertilizers or soil conditioners [5]. Re-application in soil can not only solve the problem of resource waste but also effectively increase soil fertility and provide sustainable nutrient supply for plant growth, which is of great significance for realizing the resource utilization of garden waste.

However, garden waste usually has a large proportion of lignocellulose and a high C/N ratio, which in theory can easily lead to problems such as long composting cycle and low degradation efficiency [6,7,8]. Long-term composting may also lead to a large amount of nitrogen loss and produce bad odor [9]. Practice in some parts of Europe shows that, through fine management (such as material pretreatment, regular turning, and ventilation), single garden waste can also achieve high-quality composting. In China, some studies have selected animal manure (such as dairy manure, chicken manure, and pig manure) and agricultural and forestry waste for co-composting. On the one hand, this solves the problem of organic waste in livestock and poultry breeding and realizes the recycling of the two types of waste. On the other hand, dairy manure naturally carries abundant indigenous degrading microorganisms and enzymes (such as cellulose-decomposing bacteria and xylanase), which can make up for the low microbial abundance of garden waste, and provide initial flora for the rapid construction and function of the pile microbial community. In addition, in order to avoid the above problems, previous studies have also taken many measures (such as adding organic additives, inorganic additives, and microbial additives), which can effectively regulate the microbial community structure and promote the rapid degradation and humification of organic matter [10,11]. Different from other measures, the application of bulking agents (BAs) has received extensive attention due to the availability and convenience of raw materials. At present, studies have confirmed the effectiveness of adding BAs to solve the above problems [12]. Jiang et al. [13] pointed out that NH3 emissions could be reduced by 22.8% by improving corn stover and adjusting C/N from 15 to 21. Yang et al. [14] pointed out that the application of corn stover in abandoned mushroom cultivation substrates can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, BAs can also provide richer nutrients, increase the voids in the pile, and improve water and aeration conditions, thereby increasing microbial diversity [15]. Jiao, Ren et al. [16] showed that the relative abundance of dominant fungal communities increased by more than 99% by adding 2 cm and 5 cm corn stalks to pig manure compost. Huet et al. [17] also showed that BAs can regulate microbial habitats and carbon resources, thereby promoting microbial and enzyme activities. At present, various BAs such as corn straw, sawdust, rice husk, waste paper, straw, and peanut shell have been applied to aerobic composting.

Compared with other BAs, branches, as a part of garden waste, have the characteristics of large yield, easy access, and low-cost. Moreover, the lignin content in branches is high and the degradation cycle is long, which allows them to be used repeatedly as microbial carriers. Although it has been reported that the appropriate particle size of BAs has been selected in the transformation of organic matter and the succession of fungal communities, the effects of branches with different particle sizes as BAs on physical and chemical indexes, microbial community succession, and carbon dioxide emissions in the aerobic composting of garden waste and dairy manure still need to be further explored.

Therefore, in response to these factors, a small aerobic composting reactor was used to mix crushed garden waste with dairy manure and improve it with three particle size branches for 54 days of aerobic composting treatment. The main purpose is to compare the effects of branches with different particle sizes as BAs on the conversion of compost organic matter, compost quality, and CO2 emissions, and to study the succession of bacterial and fungal communities during composting to reveal its internal mechanism.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Compost Materials and Sample Treatment

The composting experiment was conducted from June 2024 to August 2024 at the Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao County, Shandong Province, China. Garden waste came from Jinlong Shengshi Community, Linyi County, Dezhou City, Shandong Province, China, and was mainly composed of ginkgo biloba and plane leaves. Dairy manure was obtained from Qingdao Animal Husbandry Workstation and stored at 4 °C before use.

In order to ensure the uniform mixing of materials and shorten the composting cycle, the garden waste was crushed into small pieces of 3~5 mm by a crusher before composting. At the same time, the branches were treated separately into three different particle sizes: crushed debris, 1 cm, and 3 cm, which were used as compost BAs. Table 1 summarizes the main physical and chemical properties of dairy manure and garden waste.

Table 1.

Characterization of physical and chemical properties of raw materials.

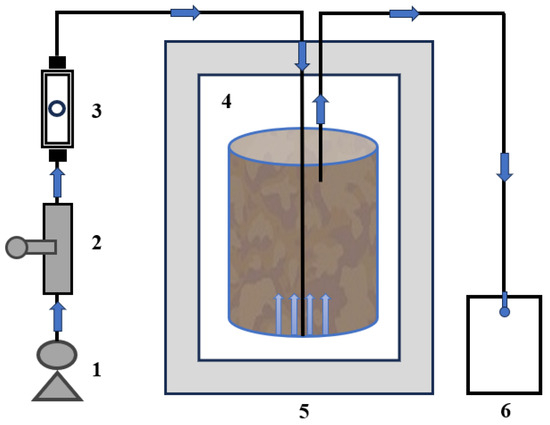

2.2. Composting Design and Sampling

The prepared bulking agents with three particle sizes (crushed, 1 cm, 3 cm) were fully mixed with garden waste and dairy manure, and the C/N of the mixture was adjusted to 26:1, which were named T1, T2, and T3, respectively, with T1 as the control group. Two experiments were repeated for each treatment. The initial moisture content was adjusted to 55% by adding distilled water. A specially designed laboratory-scale composting reactor was used, as shown in Figure 1. The composting device was composed of an air pump, a regulating valve, a flowmeter, a temperature control device, and a gas collection device. The aeration tube was extended to the bottom of the composting reactor to maintain aerobic conditions, and the aeration rate was 0.2 L/min/kg-TS. The reactor with a volume of 2.5 L was placed in an incubator, and the temperature during the composting process was controlled by adjusting the temperature of the incubator: In the heating stage (0–5 days), the temperature was increased from 30 °C to 55 °C at a rate of 5 °C per day. In the thermophilic stage (6–15 days), the temperature was maintained at 55 °C. In the cooling stage (16–25 days), the temperature was reduced from 55 °C to 25 °C at a rate of 3 °C per day, and then the compost reached maturity at room temperature. During the composting process, the water content of the system was regularly monitored, and a small amount of water was added to maintain the water content in the appropriate composting range (50~60%) to ensure microbial metabolic activity.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the experimental composting system: 1. air pump; 2. flow valve; 3. air flowmeter; 4. bio-reactor; 5. incubator; and 6. gas collection device.

During the composting period, a total of 8 samples were taken on the 0th, 3rd, 7th, 14th, 24th, 31st, 40st, and 54th days, and the moisture content of the pile was adjusted to keep the moisture content of the pile above 40%. Before each sampling, the mixture was fully mixed and then sampled, and three parallel samples were taken in each fermentation tank. The collected samples were divided into two parts. One part of the fresh samples was used to determine the physical and chemical properties, and the other part was freeze-dried in a freeze-dryer (10 N, Scientz, Ningbo, China) and stored in a refrigerator at −80 °C before biological analysis. Samples from days 0, 3, 7, 31, and 54 were subjected to high-throughput sequencing.

2.3. Determination of Physical and Chemical Properties

After the material was completely mixed, some of the samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 h and then calcined at 550 °C for 5 h to constant weight. The total solids (TSs) and organic matter (OM) contents were measured.

Aqueous extract: 3 g fresh samples were weighed and extracted with ultrapure water at a ratio of 1:10 (w/v). The samples were shaken at 150 rpm and 25 °C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was filtered with a 0.45 μm membrane, and the leachate was used to measure pH, electrical conductivity (EC), ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N), water-soluble nitrogen (WSN), and water-soluble carbon (WSC). WSC and WSN were measured using a TOC analyzer (liquid TOC II, Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany). Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometry and dual-wavelength ultraviolet spectrophotometry were used for the determination of NH4+-N and NO3−-N, respectively [18].

Another part of the samples was freeze-dried and ground to estimate total nitrogen content (TKN), cellulose, and hemicellulose. Total nitrogen content was determined by the Kjeldahl method. High-performance liquid chromatography was used to determine the content of various monosaccharides in the digestive juice of the sample after two-step hydrolysis with sulfuric acid, and the contents of cellulose and hemicellulose were calculated according to the concentration of xylose, arabinose, and glucose [19]. The CO2 produced during composting was collected daily using a gas sampling bag, and the CO2 content was determined by gas chromatography (GC-2014, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with a thermal conductivity detector. The temperatures of injection port, detector, and column oven were 100 °C, 150 °C, and 60 °C, respectively.

2.4. Microbiological Analysis

In order to study the structure and diversity of bacterial and fungal communities, samples were collected on days 0, 3, 7, 31, and 54, respectively. After DNA extraction, the quality of the extracted genomic DNA was examined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the concentration and purity of DNA were determined using NanoDrop2000 (ThermoScientific Company, Waltham, MA, USA). The V3–V4 variable region of the 16 S rRNA gene and the fungal ITS functional domain were amplified and sequenced. Primers 338 F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806 R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) were selected for bacterial amplification [20]. Fungal target genes were amplified using ITS1 (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS2 (5′ GCTGCGTTCTCATCGATGC-3′) [21]. In this study, PCR was used as the library construction step for high-throughput sequencing, and the amplified products were used for subsequent sequencing analysis. The amplification cycle program consisted of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s; annealing at 55 °C for 30 s; and extension at 72 °C for 60 s for a total of 28 cycles. After the last cycle, the reaction tube was incubated at 72 °C for 7 min to ensure sufficient extension, and finally stored at 4 °C. The specific analysis steps followed previous studies [22].

PCR amplification products were sequenced using the IluminaNextseq2000 platform (Shanghai Meiji Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The obtained original sequence was analyzed according to the following process: Fastp software (version 0.19.6) was used to control the quality of the double-ended original sequencing sequence, and FLASH software (version 1.2.11) was used for double-ended sequence splicing. The DADA2 plug-in of QIIME2 (version 2020.2) was used for denoising the sequence to obtain amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). All samples were subjected to sequence number flattening, and subsequent data analysis were performed on the Meiji Biocloud platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com, accessed on 18 February 2025). In addition, based on the comparison of the sequencing sequence with the NCBI human pathogen database, no human pathogen-related sequence was detected in the compost samples, indicating that the compost products met biosafety requirements.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Excel 2019 (Microsoft Windows, Atlanta, GA, USA) and Origin 2017 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) were used for data processing and mapping. All data were obtained by averaging three measurements and expressed as ‘mean ± standard deviation’, and error bars represent standard deviation. SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analysis and correlation testing. Origin 2017 was used to draw species composition histogram at the gate level. The community heatmap was drawn using the R language (version 3.3.1) pheatmap (1.0.8) package. Zi-Pi analysis was performed using the SpiecEasi (version 1.1.2) package and fastspar (version 1.0.0) package in R language (version 3.3.1); based on spearman correlation, species with |r| > 0.6 p < 0.05 were selected for network analysis [23].

3. Results and Discussion

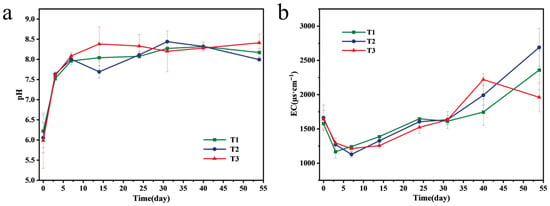

3.1. Changes in pH and EC During Composting

The pH characterizes the acidity and alkalinity of the composting environment, and its change can change the cell membrane charge of microorganisms, affecting nutrient absorption and the degradation of organic matter [3,24]. Therefore, pH is an important parameter affecting microbial activity and the composting process. Figure 2a shows the pH change curve for each treatment. The pH of each treatment showed a significant upward trend in the first week and finally stabilized at 7.5–8.5. The increase in pH was due to rising temperature, rapid degradation of organic acids during the heating stage, and the decomposition of nitrogen-containing organic matter such as proteins. Among them, the maximum increment was found in the T3 treatment, which was 40.52% higher than the initial mixed sample, indicating that the addition of 3 cm branches was beneficial to the activity of microorganisms, thus accelerating the mineralization decomposition process. In the later composting stage, the activity of nitrifying bacteria increased, releasing H+ due to alkalinity and stabilizing pH. At the end of composting, the pH of the T3 group was higher than that of the other two groups, which may be attributed to the addition of 3 cm branches. These branches increased porosity of the composting system and promoted more complete decomposition of organic nitrogen, generating more ammonia and stronger alkalinity. At the end of composting, the final pH values of T1, T2, and T3 treatments were 8.17, 8.00, and 8.41, respectively, all within the optimum composting pH range of 6.7–9.0 [25].

Figure 2.

Variations in some basic properties during composting: (a) pH and (b) EC.

EC value is an index used to reflect the concentration of soluble salts in compost extract [26]. Too high an EC value will have a toxic effect on plant growth. The EC value of each treatment showed a downward trend in the first seven days of composting and then gradually increased until the end of composting (Figure 2b). Due to the degradation of water-soluble substances such as small molecular organic acids, the EC value decreased rapidly in the initial stage. The increase in EC value may be due to the rapid decomposition and mineralization of complex organic matter such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose into soluble salts [27]. At the end of composting, the T3 treatment showed a lower EC value than the T1 and T2 treatments, which may be due to the addition of 3 cm branches improving the physical and chemical properties of compost materials, and more small molecules polymerized, thus accelerating the humification process. The EC of each treatment was less than 3500 μs/cm, which was in line with the safe use range of compost fertilizer [28].

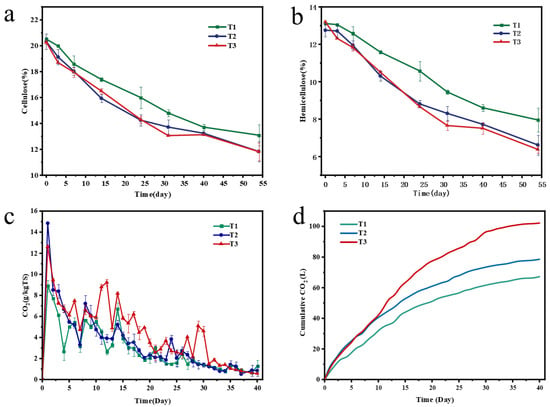

3.2. Effects of Branches on Carbon Dynamics and Cellulose Hemicellulose Loss

Carbon is one of the main elements in the composting process. Microbial growth requires carbon sources, and the degradation of organic matter can provide energy for microbial growth and activities, thus promoting composting maturity. Therefore, carbon metabolism during composting is closely related to microbial activity. In this study, changes in some important factors related to carbon, including cellulose, hemicellulose, and CO2 release, were studied to analyze the dynamics of carbon and the biodegradation of organic matter.

Garden waste contains a large amount of refractory cellulose and hemicellulose. Therefore, evaluating the content of cellulose and hemicellulose during composting can effectively reflect the efficiency of composting. As shown in Figure 3a,b, the content of cellulose and hemicellulose in each treatment group showed a significant downward trend during the whole composting process, but the addition of branches with different particle sizes resulted in different degradation rates among treatments. Among them, the degradation rates of cellulose and hemicellulose in T1, T2, and T3 treatments were 7.42% and 5.15%, 8.48% and 6.13%, and 8.45% and 6.81%, respectively. It can be seen that the degradation effects of cellulose and hemicellulose in T2 and T3 treatments were better than those in T1. This may be because the initial specific surface area of T1 treatment (crushing branch filler) is large, but it is easy to compact and agglomerate during composting, which destroys the continuity of the pile pores and leads to the formation of local anaerobic microenvironments, thus inhibiting the activity of functional microorganisms related to cellulose and hemicellulose decomposition. In the T2 (1 cm branch) and T3 (3 cm branch) treatments, the particle size of the branch BAs was moderate, and a stable and non-clogging pore structure could be formed during the composting cycle. This structure can not only continuously provide unobstructed gas exchange channels and ensure the aerobic environment of the pile, but also provide suitable microhabitats for cellulose- and hemicellulose-decomposing bacteria (such as actinomycetes) in garden waste, promote their directional proliferation and efficient secretion of extracellular enzymes (cellulase and hemicellulase), and ultimately improve the degradation efficiency of the target carbon source [29]. In addition, the degradation rate of cellulose in each treatment was higher than that of hemicellulose, indicating that cellulose was more easily utilized and decomposed by bacteria and fungi in garden waste composting. Consistent conclusions were drawn in previous studies [30].

Figure 3.

Variations in cellulose (a), hemicellulose (b), and CO2 emissions (c,d) during composting.

CO2 is the final product of microbial degradation of organic waste under aerobic conditions. Generally, the release rate of CO2 directly reflects microbial activity in the composting system, and the cumulative release of CO2 reflects the decomposition rate of organic matter [31]. Figure 3c shows the daily CO2 release of the three treatments during 0–40 days. On the first day of composting, the CO2 concentration of each treatment reached its peak, among which the peak value of T2 treatment was the highest, followed by T3, and T1 was the lowest, indicating that the addition of branches with different particle sizes had different effects on the growth and reproduction of microorganisms. After the peak, the CO2 concentration of each treatment group gradually decreased and tended to stablize in the later stage. Chen et al. showed that CO2 emission is closely related to the rapid degradation of organic matter and the succession of microbial communities [32]. Due to the increase in temperature and the rapid utilization of organic matter, microbial activity increased rapidly. Subsequently, due to the decrease in microbial activity and the reduction in available carbon sources, CO2 production gradually decreased until it stabilized. The CO2 production of the three treatments did not fluctuate widely for 10 days, at about 1 g/kg TS, and the relatively low and stable CO2 emission was an important sign of compost maturity [33]. In addition, on the 40th day of composting, the cumulative CO2 emissions of the T1, T2, and T3 groups were 67.24 L, 78.56 L, and 102.17 L, respectively (Figure 3d). The cumulative CO2 emissions of T2 and T3 treatments were 16.84% and 51.95% higher than that of the T1 group, respectively. This may be due to the fact that the branches acting as BAs optimize the supply and distribution of oxygen in the compost, which not only promotes the activity and heat production of aerobic microorganisms, but also provides abundant carbon sources for microorganisms, thus accelerating the synthesis of organic macromolecules [34,35].

Although CO2 emission is significantly positively correlated with microbial metabolic activities, its environmental effects need to be comprehensively examined in the context of climate change. In this study, although branches as BAs can effectively promote microbial activity and accelerate the decomposition and transformation of organic substrates, this also accompanied by an increase in CO2 emissions. If this emission is not included in the life cycle assessment, it may aggravate the regional carbon cycle and climate change. However, the high pore structure of the branches can optimize aeration performance of the pile and inhibit the formation of anaerobic conditions, thereby reducing (CH4) emissions. CH4’s 100-year global warming potential is 28 times that of CO2 [36], and the greenhouse effect of N2O is 300 times that of CO2 [37]. Therefore, a more comprehensive and objective assessment of its environmental impact can be achieved by comprehensively weighing the synergistic benefits of branches as BAs in reducing CH4 and N2O emissions.

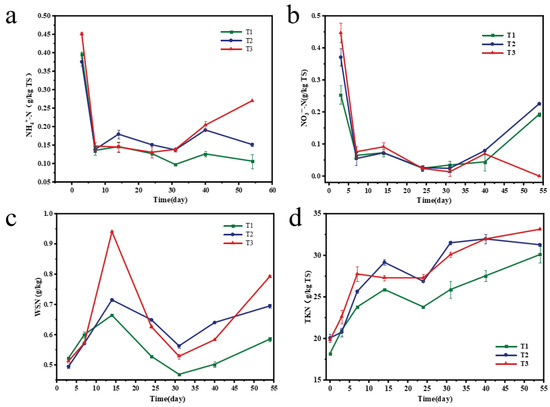

3.3. Effects of Branches on Nitrogen Transformation During Composting

In the process of composting, ammonification, nitrification, denitrification, assimilation, and volatilization of nitrogen will produce different nitrogen forms, such as ammonium hydroxide, ammonium nitrate, and ammonia, thereby improving composting products. The variation trends of NH4+-N and NO3−-N are shown in Figure 4a and b, respectively. The NH4+-N concentration of each treatment showed a downward trend in the first seven days of composting, after which the T1 and T2 treatments showed a relatively stable trend, while the T3 treatment increased significantly on the 40th day. NH4+-N content is closely related to the release of ammonia during composting, which is the main source of nitrogen loss [38,39]. Combined with the change in NO3−-N (Figure 4b), the decrease in NH4+-N concentration in the early stage was caused by the mineralization of organic nitrogen and the volatilization of NH3 [40]. The increase in NH4+-N concentration in the later stage of T3 treatment may be due to poor nitrification. The content of NO3−-N decreased in the first seven days, and then the content of NO3−-N in each treatment group decreased to almost zero. This may be due to the degradation of organic matter at this stage, resulting in insufficient oxygen supply and the formation of an anaerobic environment, resulting in denitrification and reduction in NO3−-N content. T1 and T2 increased on the 40th day, which may be caused by the conversion of NH4+-N to NO3−-N.

Figure 4.

NH4+-N (a), NO3−-N (b), water-soluble nitrogen (WSN) (c), and total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN) (d) during the composting process.

TKN is composed of organic nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen and is an essential nutrient for evaluating compost quality. Due to the large loss of organic matter and the relative retention of nitrogen, the TKN content based on dry matter showed an upward trend [41]. However, T1 and T2 decreased slightly on the 24th day (Figure 4d), which may be related to the mineralization of organic nitrogen. During the composting period, compared with T1 and T2, the TKN increase rate of T3 was the highest, increasing by 67.1%. This shows that adding branches as BAs has better nitrogen retention performance. In addition, the WSN content of T2 and T3 was higher than that of T1 (Figure 4c), which also means that adding segmental branches can retain more nitrogen nutrients, which is beneficial to plant growth.

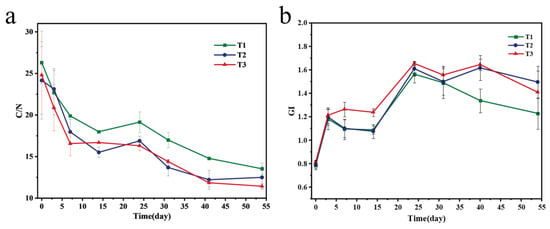

3.4. Evaluation of Compost Maturity: Dynamic Changes in C/N and Germination Index (GI)

C/N is one of the key indicators used to test whether the compost is mature or not. It is generally believed that when C/N < 20, the maturity standard is reached [42]. After the start of composting, the decrease in organic carbon content and the increase in total nitrogen content led to the gradual decrease in C/N, with the T3 group being preferentially reduced to below 20 first. The C/N of T1, T2, and T3 treatments decreased from 26.29, 24.15, and 24.80 to 13.52, 12.49, and 11.42, respectively. From Figure 5a, it can be seen that by the end of composting, the C/N of each treatment was less than 20, reaching the maturity requirement.

Figure 5.

C/N (a) and GI (b) during composting process.

From Figure 5b, in the early stage of composting, organic matter degraded to produce small molecular organic acids, ammonia, and other substances that inhibited seed germination. With the advancement of composting process, toxic substances were degraded, nutrients became stabilized, seed germination inhibition weakened, and GI rebounded. In the later stage of composting, GI was stable at more than 1.0, indicating that the compost had reached maturity, was non-toxic, and met safe application requirements.

3.5. Microbial Diversity and Succession

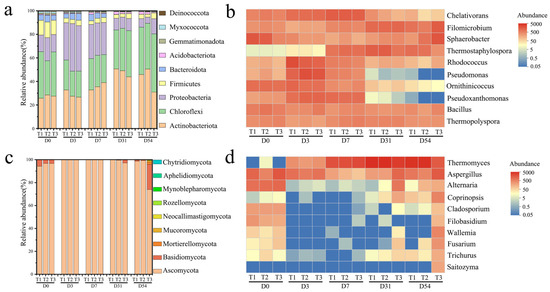

3.5.1. Diversity and Succession of Bacterial Community

Through high-throughput sequencing of composting samples at different stages, the effects of adding different particle size branches as BAs on the succession of bacterial and fungal communities in composting were explored. Figure 6a and Figure 6b show the distribution of bacteria in compost at the phylum and genus level, respectively. A total of 24 bacterial phyla were detected in 30 samples, including Actinobacteriota (34.93%), Chloroflexi (29.09%), Proteobacteria (20.07%), Firmicutes (8.24%), and Bacteroidota (3.09%). These phyla accounted for 95.25~95.26% of the identified sequences (Figure 6a). In the initial substrate, the dominant phyla Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes accounted for 20.54~26.97% of the identified sequences. However, with the increase in refractory lignocellulose content, Actinomycetes with higher lignocellulose degradation ability gradually became the main bacterial phylum, and the relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes gradually decreased. The large accumulation of Actinomycetes marks the maturity of the composting process [43]. At 54 days of composting, the abundance of Actinobacteriota in T1, T2, and T3 was 44.08%, 49.06, and 28.25%, respectively, and the abundance of Chloroflexi was 36.64%, 36.03%, and 45.22%, respectively. Previous studies have shown that some species of Chloroflexi (such as Thermophiles) and Actinobacteria can adapt to the high-temperature environment generated by composting and participate in the decomposition process of organic matter such as lignocellulose, thus promoting humus synthesis and improving germination index during composting [44,45]. The above results showed that different particle size branches as BAs can alter the bacterial community structure during composting.

Figure 6.

Bacterial community analysis: The histogram showed the top ten succession of bacterial (a) and fungal (c) communities at the phylum level. The heatmap showed the top ten genus of bacteria (b) and fungi (d) in the community.

At the genus level, it can be observed that common degrading bacteria such as Chelativorans, Pseudomonas, and Pseudoxanthomonas, which belong to Proteobacteria, proliferate rapidly in the early stage of composting and used carbohydrates, proteins, and other easily degradable organic matter to generate heat. Subsequently, with rising temperature, the relative abundance of these initial mesophilic bacteria decreased significantly after seven days. Instead, thermophilic bacteria such as Thermostaphylospora and Thermopolyspora, which are resistant to high temperature and can degrade refractory organic matter such as cellulose and hemicellulose, became dominant. Since then, with the consumption of nutrients, changes in physical and chemical properties, and interactions among microorganisms, many bacterial genera have prevailed. In addition, Bacillus maintained a high abundance throughout the composting process and studies have confirmed that Bacillus can produce polyphenol oxidase, which promotes the conversion of polyphenols into humus [46,47].

3.5.2. Diversity and Succession of Fungal Communities

Fungi can not only promote the decomposition of organic matter but also play an important role in the degradation of lignocellulose [48]. Among the 12 detected phyla, Ascomycota was the most common (93.90%), followed by Basidiomycota (2.46%) (Figure 6c). Both Ascomycota and Basidiomycota can degrade lignocellulose and promote humus synthesis [45]. Contrary to the succession of bacterial communities at the phylum level, Ascomycota played a major role in the composting process and dominated throughout the composting process in all three treatments. Ascomycetes are widely distributed in many composting ecosystems because they can quickly adapt to changing environmental factors during composting, including high temperature and low moisture [49]. In addition, Ascomycetes can secrete a variety of cellulases and hemicellulases to degrade lignocellulose and maintain activity at high temperatures [50]. As another common fungal phylum in composting, the presence of Basidiomycetes may be due to their strong lignocellulose-degrading ability [51].

At the genus level, fungi can be divided into the following three parts: I, those mainly from raw materials and inhibited by high temperature, including Alternaria, Cladosporium, and Fusarium. II, flora composed of genera such as Filobasidium, Wallemia, Saitozyma, and Trichurus, which remained low in abundance throughout the composting process, with no obvious enrichment peak. III, genera such as Thermomyces, Aspergillus, and Coprinopsis, which increased in abundance from day 7 onward and remained abundant until the end of composting. Theromyces is a thermophilic fungus capable of efficiently degrading lignocellulose by secreting enzymes. On the seventh day of composting, the content of the bacteria in T2 and T3 was higher than that in T1, which was also the reason why the content of cellulose and hemicellulose in T1 was higher than that in T2 and T3 in previous analyses. The presence of Theromyces, which are highly capable of utilizing lignocellulose, suggests that most readily available substances had been depleted, which is one of the reasons for the decline in other fungal genera [52].

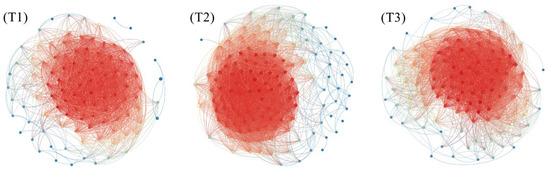

3.5.3. Co-Occurrence Network and Correlations of Microbial Communities

The topological characteristics of microbial networks provide a new perspective for studying the stability and resilience of ecosystem functions [53,54]. In order to further determine the symbiotic modes of microorganisms in the composting process under different treatments, a symbiotic network of bacteria and fungi was constructed (Figure 7). The analysis shows that the largest number of nodes was in T2 (141), followed by T3 (137) and T1 (107), and the greatest number of edges was in T2 (4371), followed by T3 (3509) and T1 (2437). This indicates that the most complex network structure can be observed in T2, indicating that using 1 cm branches as BAs established the strongest interaction between material transformation and microbial activity.

Figure 7.

Network analysis reveals the associations among bacterial ASV and fungal ASV. Each edge represents a significant strong relationship (r > 0.6, p < 0.05) between two connected ASVs. The size of each node is proportional to the number of edges on the node. Each node is colored according to its assigned network modularity. The red line represents a significant positive correlation, and the blue line represents a significant negative correlation.

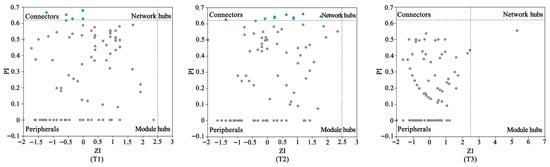

Zi-Pi analysis retained ASVs with relative abundance greater than 0.001%, Spearman correlation ≥ 0.6, and p < 0.05 in at least six samples. As shown in Figure 8, according to differences in within-module connectivity (Zi) and among-module connectivity (Pi), nodes were divided into four categories: peripherals (Zi < 2.5 and Pi < 0.62), connectors (Zi < 2.5 and Pi > 0.62), network hubs (Zi > 2.5 and Pi > 0.62), and module hubs (Zi > 2.5 and Pi < 0.62) [55]. In this study, most of the nodes in each network were peripherals (>93.15%). It was determined that T1 contained five kinds of connectors, T2 contained ten kinds of connectors, and T3 contained one module hub, with the rest being peripherals. Among them, ASV2 belongs to Aspergillus, ASV48 and ASV59 belong to Xanthomonas, and ASV80 belongs to Pseudomonas. By comparison, T2 contained a higher proportion of key species, indicating that T2 played a key role in maintaining the stability of the symbiotic network.

Figure 8.

Zi/Pi plot of nodes in the co-occurrence network.

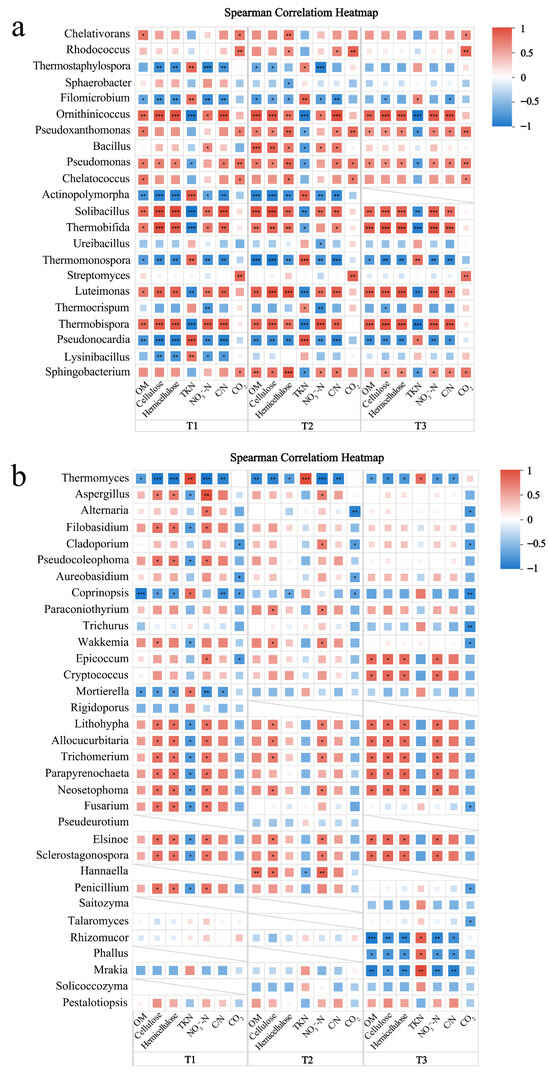

3.5.4. Correlation Analysis Between Physical and Chemical Factors and Microorganisms in Composting Process

Spearman correlation analysis was performed on the top 20 bacterial genera (Figure 9a) and fungal genera (Figure 9b) in the three treatment groups with physical and chemical factors. The heatmap results showed that there was a significant positive correlation or negative correlation between various microorganisms and physical and chemical factors (shown in the figure *), indicating that these microorganisms may play an important ecological role in the composting process.

Figure 9.

Correlation heatmaps of physicochemical factors with bacteria (a) and fungi (b) in all samples. The X-axis and Y-axis are environmental factors and species, respectively, and the correlation R value and p value are obtained by calculation. The R value is displayed in different colors in the figure. If the p value is less than 0.05, it is marked with *, and the right legend is the color interval of different R values. *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

Firstly, in terms of carbon cycle, this study found that Pseudoxanthomonas, Pseudomonas, and Chelatococcus belonging to Proteobacteria, and Rhodococcus and Streptomyces belonging to Actinobacteria, were significantly positively correlated with CO2 emissions in all treatments (p < 0.05). This indicates that Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria are key groups driving organic carbon mineralization in compost. In terms of cellulose and hemicellulose degradation, the lack or inhibition of efficient cellulose-degrading bacteria in the T1 treatment is the root cause of carbon source retention. For example, the abundance of Coprinopsis, a recognized efficient lignocellulolytic fungus, in the T1 group was always significantly lower than that in the T2 and T3 groups, and it was significantly negatively correlated with cellulose and hemicellulose in the T1 group, which proved that although it was an effective degrader, its low abundance was the root cause of T1 carbon source retention. At the same time, several thermophilic actinomycetes such as Filomicrobium, Actinopolymorpha, Thermomonospora, Thermomyces, and Thermostaphylospora, which were active in the T2 and T3 treatments, were significantly negatively correlated with cellulose/hemicellulose content. The abundance of these genera during the high-temperature period, especially the sustained higher abundance of Thermostaphylospora in T2 compared with T1 from the 7th–31st day, directly promoted the faster cellulose degradation rate in T2 treatment during this stage.

More importantly, the community structure showed functional imbalance in the early stage of the T1 treatment (0–7 days). Figure 6d shows that the relative abundance of Aspergillus and Filobasidium in the T1 group was significantly higher than that in the T2 and T3 groups and was significantly positively correlated with cellulose and hemicellulose content. This does not mean that they are efficient degraders; instead, it reveals their strong occupancy but low degradation efficiency. Their physical coverage may hinder the contact of other efficient bacteria with substrates, resulting in delayed degradation. In addition, Ornithinicoccus was significantly positively correlated with cellulose and hemicellulose content in all treatments, suggesting that Ornithinicoccus may not be a direct cellulose-degrading bacterium but is more inclined to use readily available carbon sources produced during fiber degradation. Its abundance increases with substrate abundance, reflecting its ecological strategy as a ‘secondary user’.

Secondly, in terms of nitrogen cycle, Pseudomonas and Ornithinicoccus were identified as key microorganisms related to nitrogen loss. The abundance was higher in the early stage of composting (0–7 days) and was significantly negatively correlated with TKN. As an aerobic denitrifying bacterium, Pseudomonas can directly convert nitrogen into gaseous forms, while Ornithinicoccus may produce volatile ammonia nitrogen through strong ammonification. The combined effect of the two constitutes the core mechanism of severe nitrogen loss in the early stage of T1. In contrast, Actinobacteria played a key role in nitrogen retention in the later stage of composting. Multiple genera, including Thermostaphylospora, Filomicrobium, Actinopolymorpha, Thermomonospora, and Thermocrispum, were significantly positively correlated with TKN. These bacteria belong to lignocellulose-degrading bacteria. When they decompose high-carbon substrates, they need to simultaneously absorb nitrogen sources to synthesize their own cellular substances (such as proteins and nucleic acids), which effectively retains nitrogen and reduces gaseous nitrogen loss. The increased abundance of Thermostaphylospora after seven days is a typical representative of this process.

In summary, this study revealed the complex interaction between microorganisms and composting physicochemical factors in different treatment groups. In the early stage of T1 treatment, low-efficiency nitrogen-consuming fungi (such as Aspergillus) were enriched, while high-efficiency degrading bacteria (such as Coprinopsis and various thermophilic Actinomycetes) were inhibited, resulting in the coexistence of ‘carbon retention’ and ‘nitrogen loss’. T2 and T3 improved microbial community composition by adding BAs to improve the microenvironment and nutrient supply conditions, thereby achieving efficient synergy of carbon and nitrogen cycles [56]. These correlations not only help to clarify the functional role of microorganisms in the composting process but also provide a theoretical basis for optimizing composting processes, regulating microbial community structure and improving composting efficiency.

3.6. Effect of Branch BAs on Microenvironment of Composting System

The microenvironment (moisture, permeability) of the composting system is one of the key factors affecting composting efficiency. In this study, the pore structure of branches used as BAs significantly optimized air fluidity in the composting system: their loose fiber skeleton broke the agglomeration state of the material, increased porosity, promoted diffusion and transmission of oxygen, and provided sufficient aerobic conditions for the metabolic activities of aerobic microorganisms. For example, the abundance of the high-efficiency lignocellulose-degrading fungus Coprinopsis in the T1 group was always significantly lower than that in the T2 and T3 groups, which was the root cause of carbon source retention in T1.

At the same time, because the temperature of the composting environment was continuously simulated by an incubator in this study and the water-holding capacity of branch fibers is relatively limited, the system’s water retention decreased slightly. This characteristic required the supplement of small amounts of water during the composting process to maintain an appropriate water level (50–60%). However, from a practical perspective, the strengthening effect of branches on permeability is the core advantage of branches as BAs, as it effectively alleviates the problem of ‘slow maturity caused by insufficient permeability’ in traditional composting. The minor fluctuation in water retention can be balanced by simple water regulation, so branches still have high practical application value.

4. Conclusions

This study verified that the addition of branches as BAs could effectively promote the composting process, and the size of the branches was proven to be related to carbon conversion, CO2 emission, and microbial activity. Compared with branch powder, the addition of branches with different particle sizes resulted in faster degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose and higher CO2 emissions. At the same time, the results of microbial diversity showed that the addition of 1 cm branches could optimize the living conditions of microorganisms, thereby enriching the richness and complexity of bacterial and fungal communities.

In practical application, the results of this study provide low-cost technical support for the resource utilization of garden waste and the improvement in quality and efficiency in the composting industry. Branches are widely available and easy to process. The standardized application of 1 cm diameter branches can achieve a win-win goal of ‘waste reduction’ and ‘high-quality composting’, which is in line with the concept of a circular economy. It can effectively solve the pain points such as slow decomposition of organic matter and severe nitrogen loss in traditional composting, laying a foundation for the promotion of compost products in farmland improvement, landscaping, and other scenarios. In short, 1 cm branches are recommended as compost BAs.

Future research can focus on the following directions: (1) Exploring the compounding effect of 1 cm branches with straw, sawdust, and other BAs to further optimize composting performance. (2) Conducting field experiments to systematically evaluate the long-term effects of branch-based compost products on soil–crop system growth and soil ecology. (3) Exploring CO2 emission reduction technologies in 1 cm branch-based composting systems by regulating branch pretreatment methods (such as carbonization or maturity) or composting process parameters (such as ventilation rate or turning frequency), balancing composting efficiency with environmental benefits.

Author Contributions

Q.L.: Conceptualization, Software, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, and Visualization. Z.L.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, and Project Administration. S.M.: Formal Analysis, Data Curation, and Software. L.L.: Formal Analysis and Data Curation. Q.H.: Investigation and Writing—Review and Editing. S.L.: Software and Visualization. M.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, and Supervision. Y.L.: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Resources, and Project Administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by the 2025 Qingdao Science and Technology Benefiting the People Demonstration Special Project (2325039/662) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2024QB307). Regarding the APC, it will be paid by the corresponding author personally first, and then reimbursed through the 2025 Qingdao Science and Technology Benefiting the People Demonstration Special Project (2325039/662) with the official invoice.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feng, X.; Zhang, L. Composite additives regulate physicochemical and microbiological properties in green waste composting: A comparative study of single-period and multi-period addition modes. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, G.; Yang, H.; Luo, Z. Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis mechanism: A state-of-the-art review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 62, 33–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pan, J.; Ma, X.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.J.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Solid digestate biochar amendment on pig manure composting: Nitrogen cycle and balance. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 349, 126848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Microbial community responses to biochar addition when a green waste and manure mix are composted: A molecular ecological network analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 273, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawoteea, S.A.; Mudhoo, A.; Kumar, S. Co-composting of vegetable wastes and carton: Effect of carton composition and parameter variations. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 227, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wei, S.; Jing, Z.; Lin, X. N2O emissions and nitrogen transformation during windrow composting of dairy manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zeng, Y. Ammonia emission mitigation in food waste composting: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Effects of additives on the co-composting of forest residues with cattle manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 368, 128384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, K.; Keener, H.M.; Elwell, D.L. Composting Short Paper Fiber with Broiler Litter and Additives: Part I: Effects of Initial pH and Carbon/Nitrogen Ratio On Ammonia Emission. Compos. Sci. Util. 2000, 8, 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Li, H.; Song, D.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y. Influence of zeolite and superphosphate as additives on antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial communities during factory-scale chicken manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Rong, K.; Li, J.; Jiang, L. Effects of microbial inoculant and additives on pile composting of cow manure. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1084171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Shi, X.-S.; Yang, Z.-M.; Xu, X.-H.; Guo, R.-B. Effects of recyclable ceramsite as the porous bulking agent during the continuous thermophilic composting of dairy manure. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Schuchardt, F.; Li, G.; Guo, R.; Zhao, Y. Effect of C/N ratio, aeration rate and moisture content on ammonia and greenhouse gas emission during the composting. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 23, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, G.X.; Yang, Q.Y.; Luo, W.H. Effect of bulking agents on maturity and gaseous emissions during kitchen waste composting. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Awasthi, M.K.; Li, R.; Park, J.; Pensky, S.M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Recent developments in biochar utilization as an additive in organic solid waste composting: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, M.; Ren, X.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Z. Humification improvement by optimizing particle size of bulking agent and relevant mechanisms during swine manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, J.; Druilhe, C.; Trémier, A.; Benoist, J.C.; Debenest, G. The impact of compaction, moisture content, particle size and type of bulking agent on initial physical properties of sludge-bulking agent mixtures before composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liao, X.; Wu, Y.; Liang, J.B.; Mi, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of different types of biochar on methane and ammonia mitigation during layer manure composting. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Feng, Q.; Li, X.; Xu, B.; Shi, X.; Guo, R. Effects of arginine modified additives on humic acid formation and microbial metabolic functions in biogas residue composting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, D.; Ma, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, Q.; Lee, D.-J. Denitrifying sulfide removal process on high-salinity wastewaters in the presence of Halomonas sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yin, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, W. Insight into the effect of nitrogen-rich substrates on the community structure and the co-occurrence network of thermophiles during lignocellulose-based composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.; Shi, X.; Lu, M.; Zhang, M.; Dong, X.; Li, X.; Guo, R. Accelerated adsorption of tetracyclines and microbes with FeOn(OH)m modified oyster shell: Its application on biotransformation of oxytetracycline in anaerobic enrichment culture. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberán, A.; Bates, S.T.; Casamayor, E.O.; Fierer, N. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 2012, 6, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Deng, Y.; Li, J.; Ji, M.; Ruan, W. Role of the proportion of cattle manure and biogas residue on the degradation of lignocellulose and humification during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 122941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Zang, B.; Li, Y. Effect of spent mushroom substrate as a bulking agent on gaseous emissions and compost quality during pig manure composting. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 12398–12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cano, I.; Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Biochar improves N cycling during composting of olive mill wastes and sheep manure. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, L. Combined addition of biochar, lactic acid, and pond sediment improves green waste composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 852, 158326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ju, M.; Li, W.; Ren, Q.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Y. Rapid production of organic fertilizer by dynamic high-temperature aerobic fermentation (DHAF) of food waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 197, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Cai, D.; Huang, F.; Mohamed, T.A.; Li, P.; Qiao, X.; Wu, J. Promoting lignin exploitability in compost: A cooperative microbial depolymerization mechanism. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 174, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, W.; Chang, N.; Sun, L.; Bello, A.; Deng, L.; Sun, Y. Exploration of β-glucosidase-producing microorganisms community structure and key communities driving cellulose degradation during composting of pure corn straw by multi-interaction analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Aguirre, E.; Auras, R.; Selke, S.; Rubino, M.; Marsh, T. Insights on the aerobic biodegradation of polymers by analysis of evolved carbon dioxide in simulated composting conditions. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Awasthi, S.K.; Liu, T.; Duan, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K. Effects of microbial culture and chicken manure biochar on compost maturity and greenhouse gas emissions during chicken manure composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 121908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wang, R.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ouyang, C.; Zhou, T. Effects of exogenous additives on thermophilic co-composting of food waste digestate: Coupled response of enhanced humification and suppressed gaseous emissions. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hu, H.-W.; Guo, H.-G.; Butterly, C.; Bai, M.; Zhang, Y.-S.; He, J.-Z. Lignite as additives accelerates the removal of antibiotic resistance genes during poultry litter composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xiong, J.; Cui, R.; Sun, X.; Han, L.; Xu, Y.; Huang, G. Effects of intermittent aeration on greenhouse gas emissions and bacterial community succession during large-scale membrane-covered aerobic composting. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC; Core Writing Team; Lee, H.; Romero, J. (Eds.) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–133. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Xu, R.; Canadell, J.G.; Thompson, R.L.; Winiwarter, W.; Suntharalingam, P.; Davidson, E.A.; Ciais, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 2020, 586, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Ma, W. Transformation of nitrogen and carbon during composting of manure litter with different methods. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainudin, M.H.; Mustapha, N.A.; Maeda, T.; Ramli, N.; Sakai, K.; Hassan, M. Biochar enhanced the nitrifying and denitrifying bacterial communities during the composting of poultry manure and rice straw. Waste Manag. 2020, 106, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.-Z.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, S.-P.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Tang, Y.-Q.; Kida, K. Insight into the microbiology of nitrogen cycle in the dairy manure composting process revealed by combining high-throughput sequencing and quantitative PCR. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, G. Performance of co-composting sewage sludge and organic fraction of municipal solid waste at different proportions. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, P.C.; Biswas, D.R. Assessment of maturity indices of rock phosphate enriched composts using variable crop residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, X.; Deng, H.; Dong, D.; Tu, Q.; Wu, W. New insights into the structure and dynamics of actinomycetal community during manure composting. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 3327–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yang, M.; Sun, H.; Meng, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, M.; Wu, C. Role of multistage inoculation on the co-composting of food waste and biogas residue. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Lu, W.; Liu, Y.; Ming, Z.; Liu, Y.; Meng, R.; Wang, H. Structure and diversity of bacterial communities in two large sanitary landfills in China as revealed by high-throughput sequencing (MiSeq). Waste Manag. 2017, 63, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-García, M.C.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; López, M.J.; Moreno, J. Effect of inoculation in composting processes: Modifications in lignocellulosic fraction. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Piazza, S.; Houbraken, J.; Meijer, M.; Cecchi, G.; Kraak, B.; Rosa, E.; Zotti, M. Thermotolerant and Thermophilic Mycobiota in Different Steps of Compost Maturation. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.; Su, C.; Mo, T.; Liao, L.; Zhu, F.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M. Effect of excess sludge and food waste feeding ratio on the nutrient fractions, and bacterial and fungal community during aerobic co-composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Xun, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, L. Thermomyces lanuginosus is the dominant fungus in maize straw composts. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 197, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, K.; Jarvis, Å.; Vasara, T.; Romantschuk, M.; Sundh, I. Effects of differing temperature management on development of Actinobacteria populations during composting. Res. Microbiol. 2007, 158, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, T.K.; Mäkelä, M.R.; Hildén, K. Lignin-modifying enzymes in filamentous basidiomycetes—Ecological, functional and phylogenetic review. J. Basic Microbiol. 2010, 50, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basotra, N.; Kaur, B.; Di Falco, M.; Tsang, A.; Chadha, B.S. Mycothermus thermophilus (Syn. Scytalidium thermophilum): Repertoire of a diverse array of efficient cellulases and hemicellulases in the secretome revealed. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Guo, W.; Wei, Y.; Luo, J.; Song, C.; Zhao, Y. Two types nitrogen source supply adjusted interaction patterns of bacterial community to affect humifaction process of rice straw composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 332, 125129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chu, L.; Ma, J.; Chi, G.; Lu, C.; Chen, X. Effects of multiple antibiotics residues in broiler manure on composting process. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Bascompte, J.; Dupont, Y.; Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19891–19896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Song, C.; Chen, X.; Zhao, M. Lignite drove phenol precursors to participate in the formation of humic acid during chicken manure composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).