An Intelligent Strategy for Colony De-Replication Using Raman Spectroscopy and Hybrid Clustering

Abstract

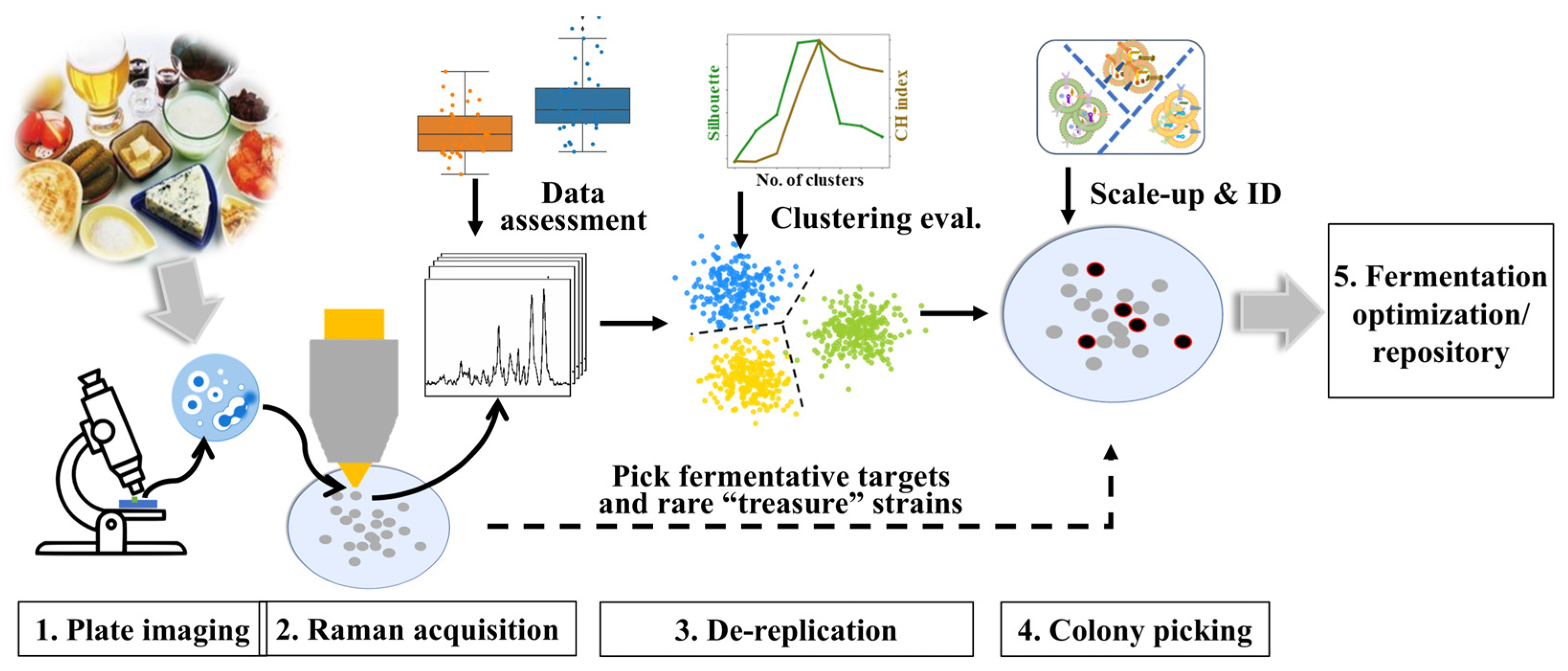

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Experimental Systems

2.2. Raman Acquisition Strategy and Instrument Parameters

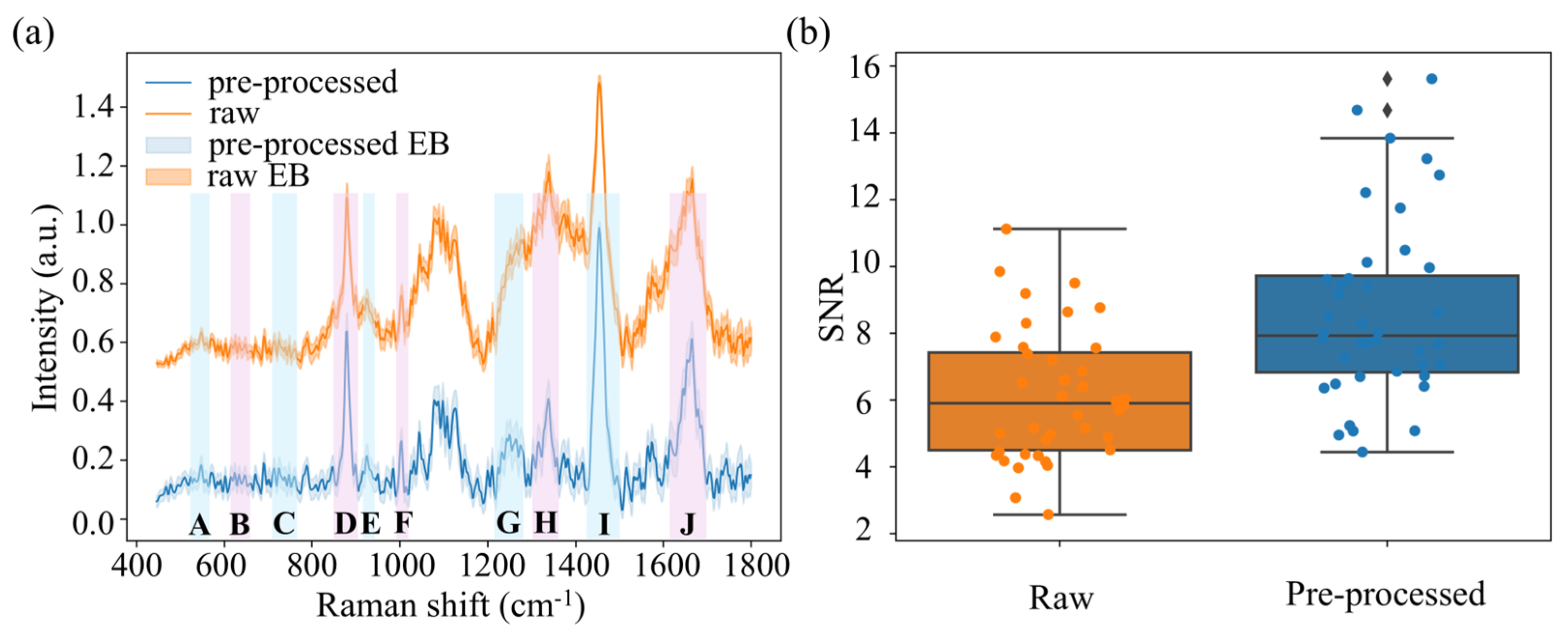

2.3. Spectral Denoising and Quality Assessment

2.4. Colony Selection Framework and Evaluation

2.5. Validation on Complex Mixed Plates

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spectral Denoising Performance

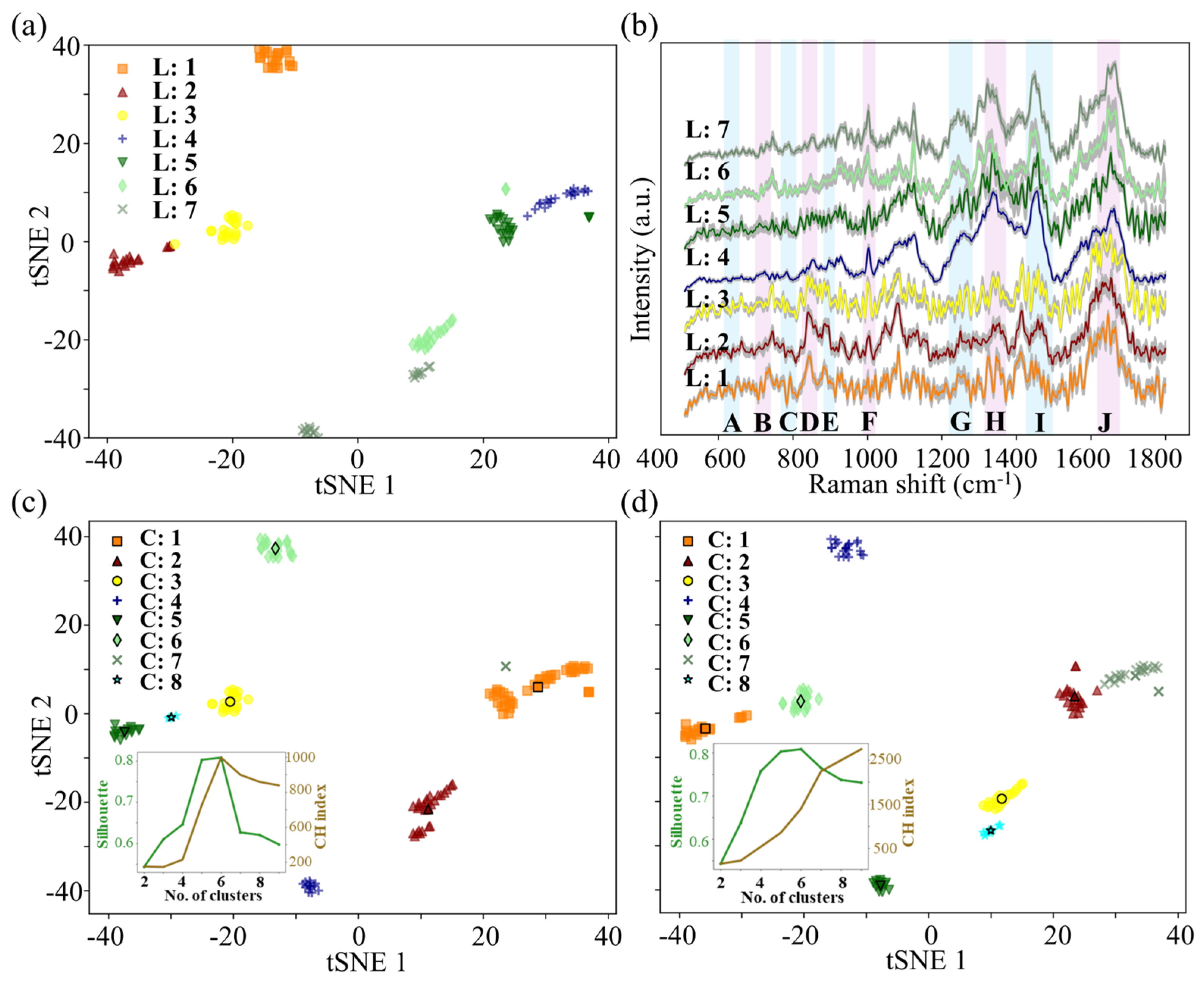

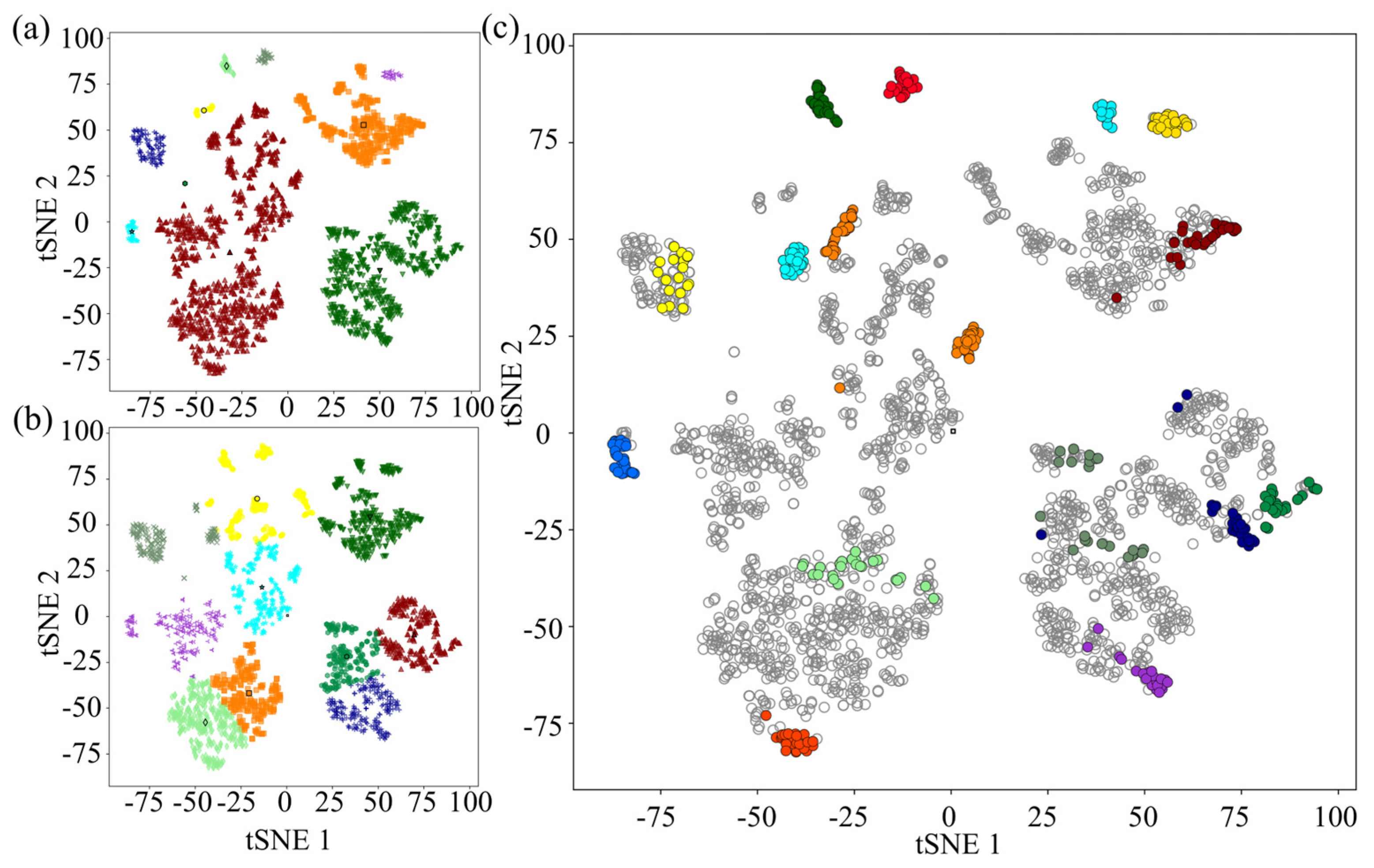

3.2. Application of the Method on Pure Colonies

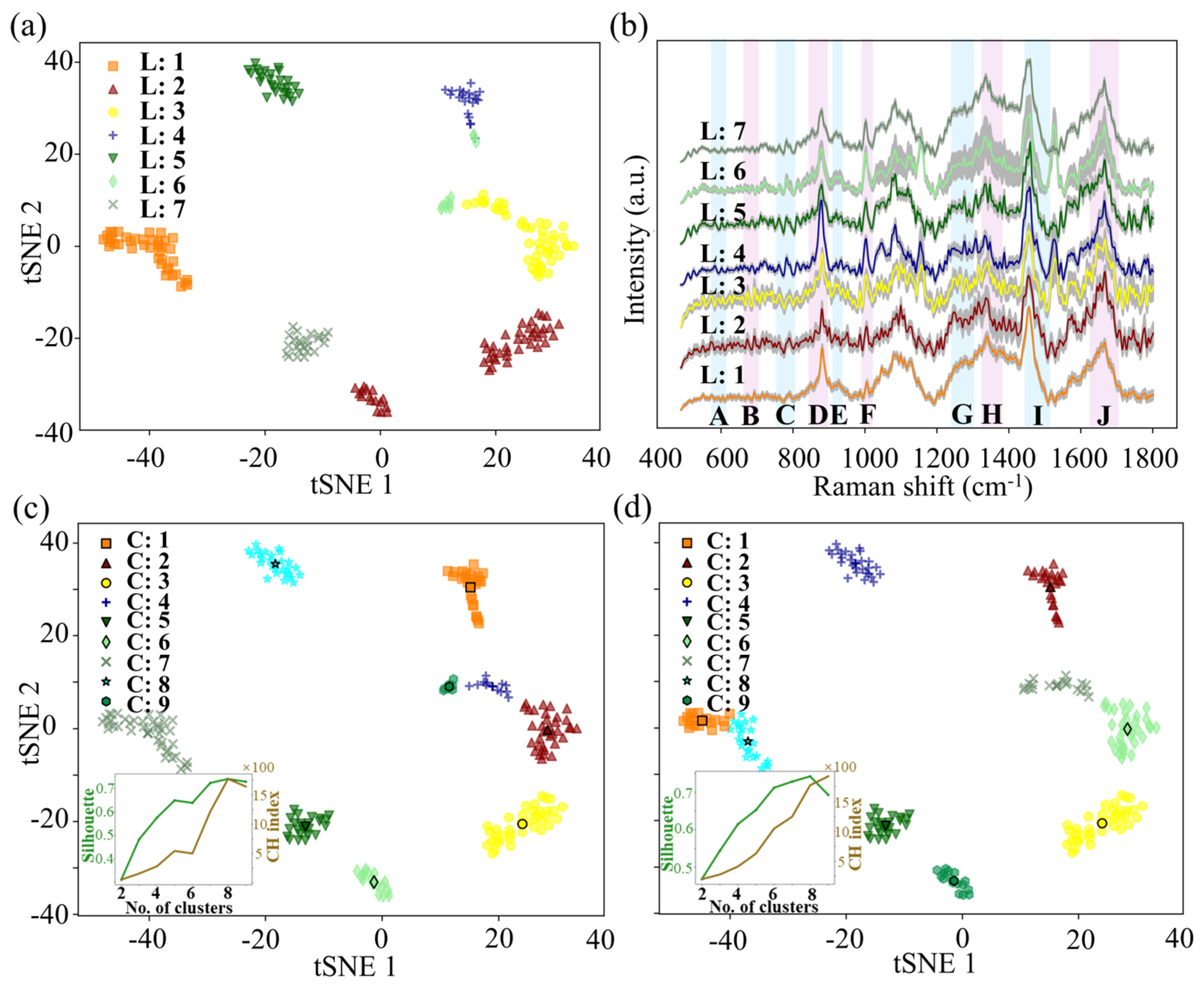

3.3. Application of the Method on Complex Mixed Plates

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Ning, K. Synergy of traditional practices and modern technology: Advancing the understanding and applications of microbial resources and processes in fermented foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 157, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sheth, R.U.; Zhao, S.; Cohen, L.A.; Dabaghi, K.; Moody, T.; Sun, Y.; Ricaurte, D.; Richardson, M.; Velez-Cortes, F.; et al. High-throughput microbial culturomics using automation and machine learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, J.; Huang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.-D. Machine learning advances in microbiology: A review of methods and applications. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 925454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuser, E.; Becker, K.; Idelevich, E.A. Evaluation of an automated system for the counting of microbial colonies. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00673-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; He, Y.; Yu, I.; Imani, A.; Scholl, D.; Miller, J.F.; Zhou, Z.H. Atomic structures of a bacteriocin targeting Gram-positive bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.L.; Pan, Q.K.; Miao, Z.H.; Suganthan, P.N.; Gao, K.Z. Multi-objective multi-picking-robot task allocation: Mathematical model and discrete artificial bee colony algorithm. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 6061–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Marsafari, M.; Tolosa, M.; Andar, A.; Ramamurthy, S.S.; Ge, X.; Kostov, Y.; Rao, G. Rapid ultrasensitive and high-throughput bioburden detection: Microfluidics and instrumentation. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 8683–8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombelet, S.; Natale, A.; Ronat, J.-B.; Kesteman, T.; Vandenberg, O.; Jacobs, J.; Hardy, L. Biphasic versus monophasic manual blood culture bottles for low-resource settings: An in-vitro study. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e124–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronnello, C.; Francipane, M.G. Moving towards induced pluripotent stem cell-based therapies with artificial intelligence and machine learning. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriotti, G.; Borisov, S.M.; Berg, J.S.; de Anna, P. Morphology and size of bacterial colonies control anoxic microenvironment formation in porous media. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17471–17480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binelli, M.R.; Kan, A.; Rozas, L.E.; Pisaturo, G.; Prakash, N.; Studart, A.R. Complex Living Materials Made by Light-Based Printing of Genetically Programmed Bacteria. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2207483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, A.; Campolongo, E.G.; Meyers, L.; Rayeed, S.M.; Stevens, S.; Zarubiieva, I.; Fluck, I.E.; Girón, J.C.; Jousse, M.; Lowe, S.; et al. Optimizing image capture for computer vision-powered taxonomic identification and trait recognition of biodiversity specimens. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2025, 16, 2260–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, J.B.; Lowhorn, R.J.; Walden, R.; Márquez-Zacarías, P.; Molotkova, E.; Perron, G.; Solis-Lemus, C.; Alarcon, D.P.; Brown, S.P. Machine learning identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from colony image data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Guo, C.; Zhai, L.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Single-cell rapid identification, in situ viability and vitality profiling, and genome-based source-tracking for probiotics products. Imeta 2023, 2, e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Lu, Z.-M.; Zhang, X.-J.; Chai, L.-J.; Wang, S.-T.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Shen, C.-H.; Li, B.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H. Metabolic Activity Profiling of High-Temperature Daqu Microbiota Using Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy and Deuterium Isotope Probing. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 18199–18207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Wu, Q. Non-Invasive Detection of Biomolecular Abundance from Fermentative Microorganisms via Raman Spectra Combined with Target Extraction and Multimodel Fitting. Molecules 2023, 29, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, M. RamanCluster: A deep clustering-based framework for unsupervised Raman spectral identification of pathogenic bacteria. Talanta 2024, 275, 126076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.H.; Ciloglu, F.U.; Yilmaz, U.; Simsek, E.; Aydin, O. Discrimination of waterborne pathogens, Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts and bacteria using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy coupled with principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 267, 120475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubewa, L.; Timoshchenko, I.; Kulahava, T. Specificity of carbon nanotube accumulation and distribution in cancer cells revealed by k-means clustering and principal component analysis of Raman spectra. Analyst 2024, 149, 2680–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapkevicius, M.D.L.E.; Sgardioli, B.; Câmara, S.P.; Poeta, P.; Malcata, F.X. Current trends of enterococci in dairy products: A comprehensive review of their multiple roles. Foods 2021, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidi-Fazli, N.; Hanifian, S. Biodiversity, antibiotic resistance and virulence traits of Enterococcus species in artisanal dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 129, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, J.; Martiniuk, J.; Ma, X.; Li, Q.; Measday, V.; Lu, X. Species identification and strain discrimination of fermentation yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces uvarum using Raman spectroscopy and convolutional neural networks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e01673-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, S.Á.; Makrai, L.; Csabai, I.; Tőzsér, D.; Szita, G.; Solymosi, N. Bacterial colony size growth estimation by deep learning. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, X.; Wang, S. Effects of different soybean and maize mixed proportions in a strip intercropping system on silage fermentation quality. Fermentation 2022, 8, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Lv, X.; Zhao, Q.; Lei, Y.; Gao, C.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Ma, T. Optimization of strains for fermentation of kiwifruit juice and effects of mono- and mixed culture fermentation on its sensory and aroma profiles. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Mu, J.; Gong, W.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, M.; Song, Y.; Li, B.; Jin, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D. In vitro diagnosis and visualization of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats and protective effects of ferulic acid by raman biospectroscopy and machine learning. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 14, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Yu, M. A Subpixel Calibration Strategy for Micro-Raman Spectrometer in Subvisible Particles Traceable Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3436109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, F.; Wang, Q.; Luo, J.; Hao, J.; Xu, M. Baseline correction method based on improved adaptive iteratively reweighted penalized least squares for the X-ray fluorescence spectrum. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 5707–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Sadasivan, J.; Seelamantula, C.S. Adaptive Savitzky-Golay filtering in non-Gaussian noise. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 5021–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Colony De-Replication Framework (Version 1.0) [Python 3.6]. Available online: https://github.com/lixinli1230-commits/kmeans-HCA (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Spedalieri, C.; Plaickner, J.; Speiser, E.; Esser, N.; Kneipp, J. Ultraviolet resonance raman spectra of serum albumins. Appl. Spectrosc. 2023, 77, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhu, X.; Fan, Q.; Wan, X. Raman spectra of amino acids and their aqueous solutions. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 78, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, A.C.S.; Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Raman spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2015, 50, 46–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plate | Total Colonies | Species Covered | Colonies Picked | Actual Number of Species Identified | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | Image + Clustering | Raman + Clustering | ||||

| A | 46 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| B | 67 | 10 | 13 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| C | 113 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, J.; Wang, S. An Intelligent Strategy for Colony De-Replication Using Raman Spectroscopy and Hybrid Clustering. Fermentation 2025, 11, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120691

Li X, Liu M, Sun J, Wang S. An Intelligent Strategy for Colony De-Replication Using Raman Spectroscopy and Hybrid Clustering. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120691

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xinli, Mingyang Liu, Jiaqi Sun, and Su Wang. 2025. "An Intelligent Strategy for Colony De-Replication Using Raman Spectroscopy and Hybrid Clustering" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120691

APA StyleLi, X., Liu, M., Sun, J., & Wang, S. (2025). An Intelligent Strategy for Colony De-Replication Using Raman Spectroscopy and Hybrid Clustering. Fermentation, 11(12), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120691