Comprehensive Advances on Probiotic-Fermented Medicine and Food Homology

Abstract

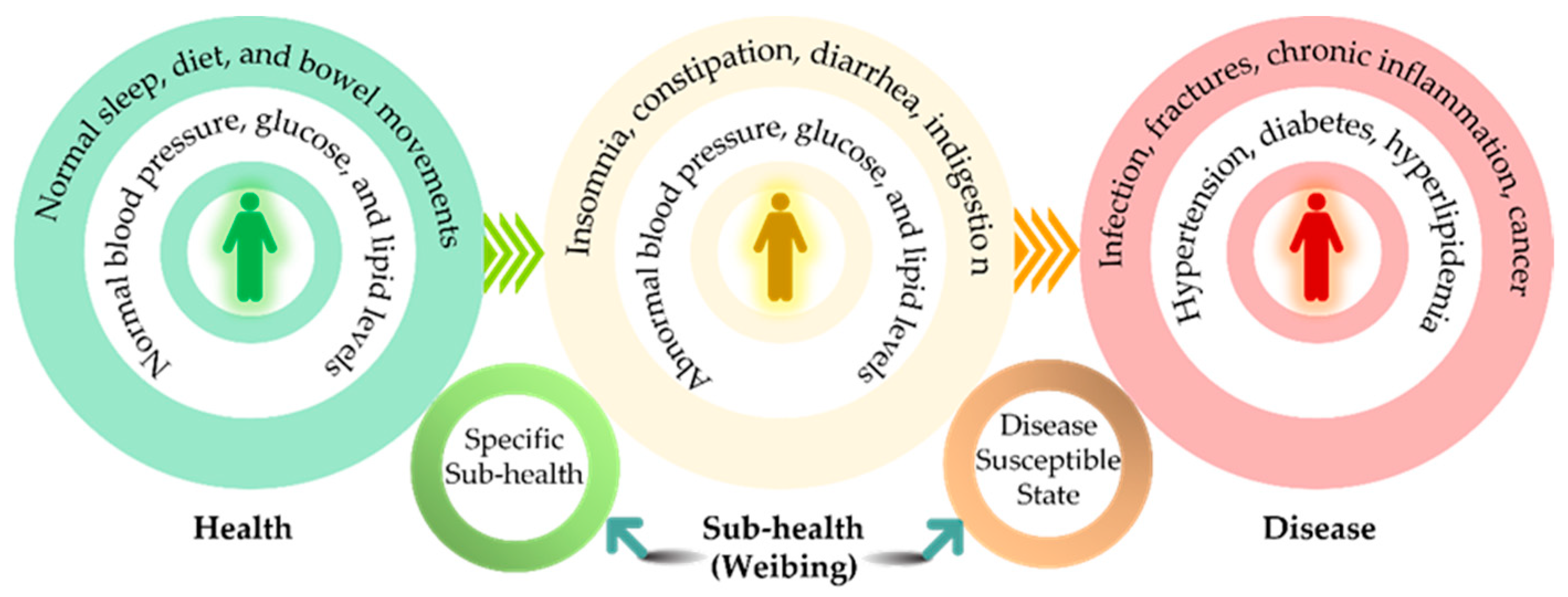

1. Introduction

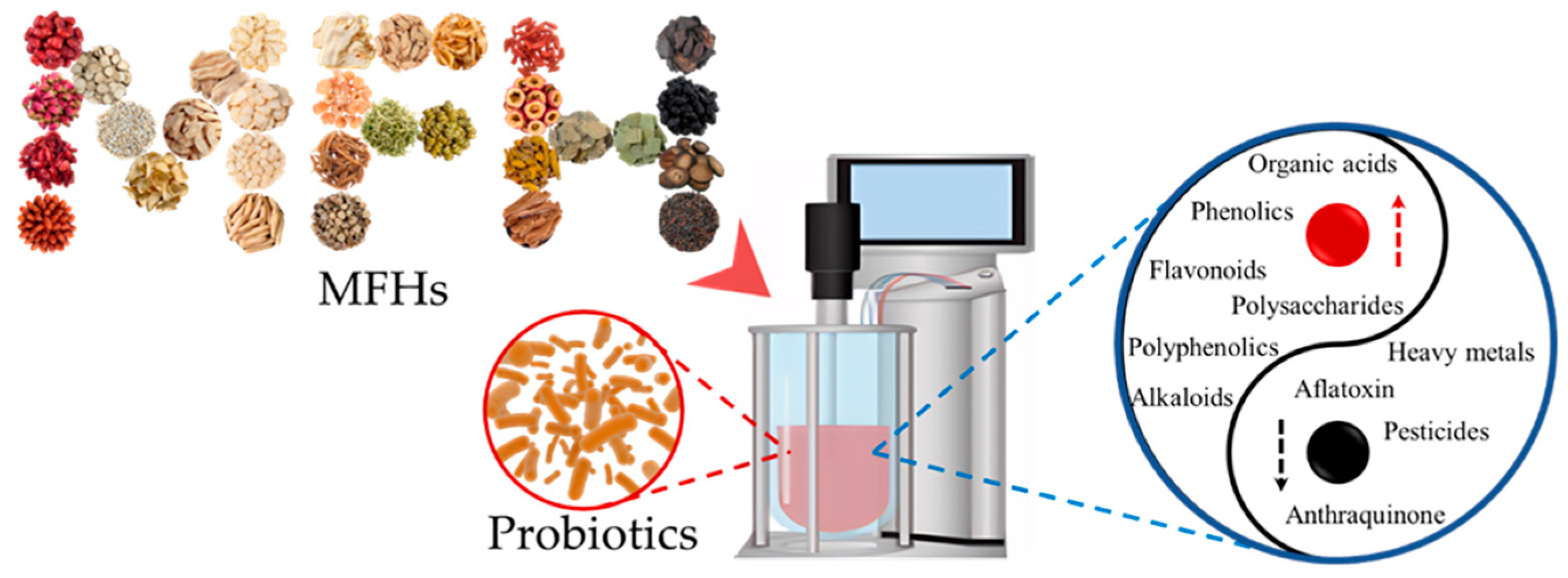

2. The Reciprocal Impact of Fermented MFHs and Probiotics

2.1. The Impact of Probiotics on MFHs

2.1.1. Changes in the Active Ingredients of MFHs

2.1.2. Changes in the Toxins, Heavy Metals, and Pesticides of MFHs

2.2. The Impact of MFHs on Probiotics

3. Pharmacological Activities of MFH Fermentation Product

3.1. Anti-Inflammation and Antibacterial Activity

3.2. Regulation of Hyperlipidemia, Hypertension, and Hyperglycemia

3.3. Antioxidation, Immune Enhancement, and Antitumor

3.4. Regulation of Intestinal Microecology

4. Establishment of the Effective Probiotic Fermentation System

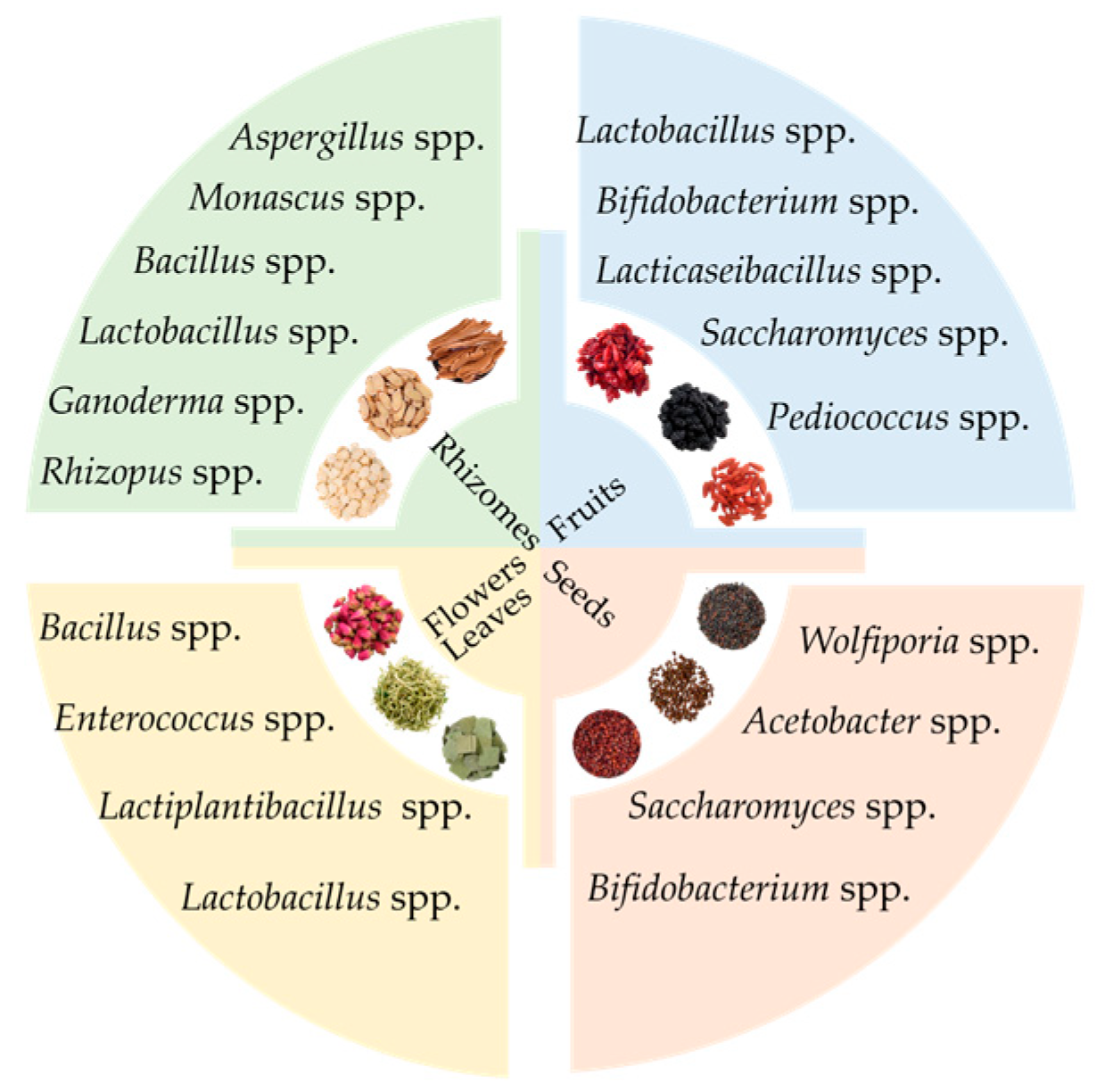

4.1. Selection of MFHs

4.2. Determination of Probiotics

4.2.1. Experimental and Empirical Method

4.2.2. AI Assistant Selection of Probiotics

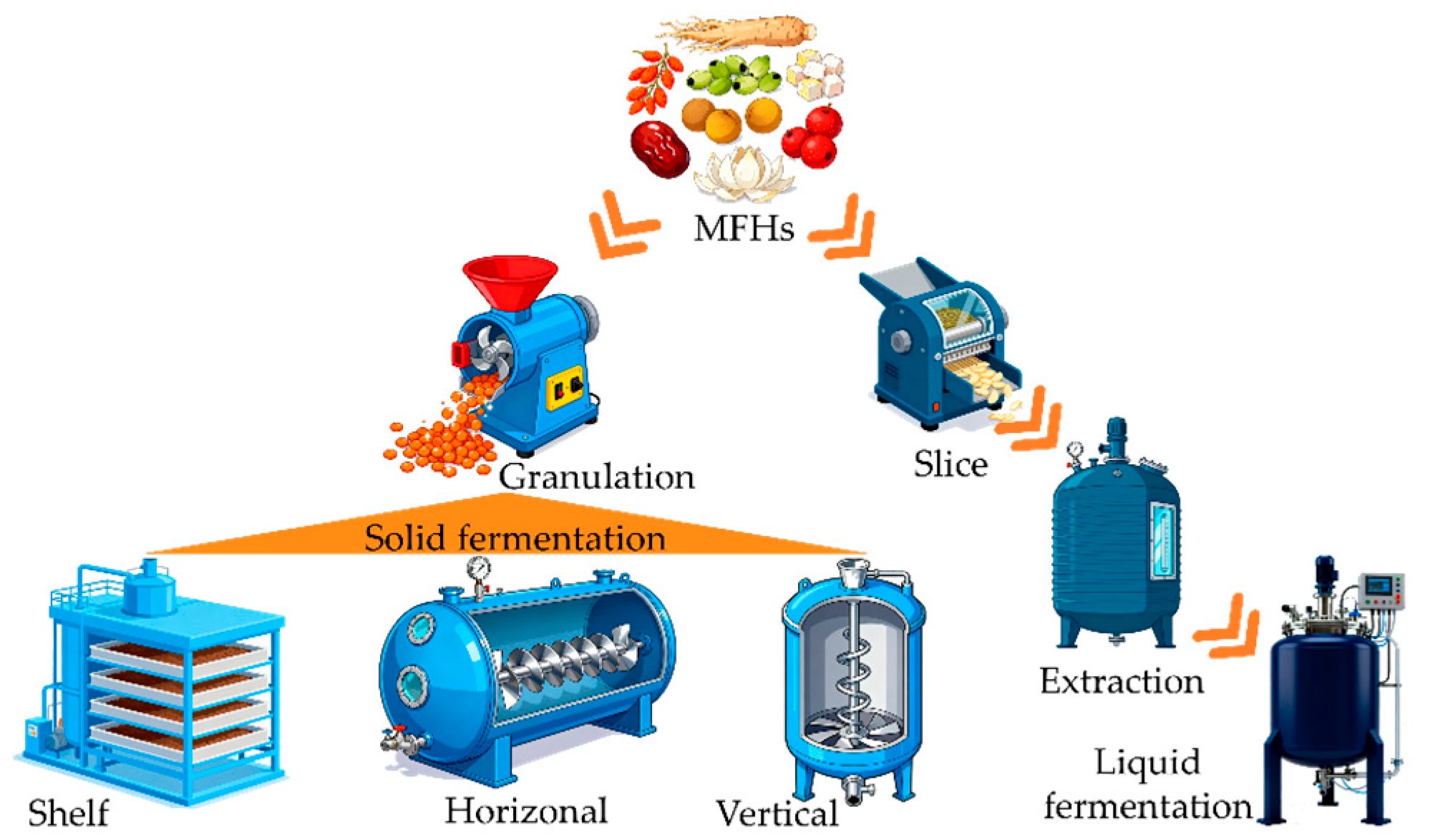

4.3. Fermentation Mode

4.3.1. Solid-State Fermentation (SSF)

4.3.2. Liquid Fermentation

4.3.3. Single-, Bidirectional-, and Multispecies-Probiotic Fermentation

5. Quality Control of MFH Fermentation

5.1. Quality Control of MFH Raw Materials

5.2. Screening of Adaptive Probiotics

5.3. Development of Fine-Regulated Fermentation

6. Challenges of MFH Fermentation

7. Perspective of MFH Fermentation

7.1. From Screening to Creating Probiotics for Fermentation

7.2. Establishment of a Quality Standard System

7.3. Application of AI in MFH Fermentation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, L. “Am I in ‘Suboptimal Health’?”: The Narratives and Rhetoric in Carving out the Grey Area Between Health and Illness in Everyday Life. Sociol. Health Illn. 2025, 47, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Z.; Kong, K.W.; Xiang, P.; He, X.; Zhang, X. Probiotic fermentation improves the bioactivities and bioaccessibility of polyphenols in Dendrobium officinale under in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion and fecal fermentation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1005912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Wang, R.; Ouyang, S.; Liang, W.; Duan, J.; Gong, W.; Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Kurihara, H.; et al. “Weibing” in traditional Chinese medicine—Biological basis and mathematical representation of disease-susceptible state. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M.-H.; Zhu, S.-R.; Duan, W.-J.; Ma, X.-H.; Luo, X.; Liu, B.; Kurihara, H.; Li, Y.-F.; Chen, J.-X.; He, R.-R. “Shanghuo” increases disease susceptibility: Modern significance of an old TCM theory. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 250, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tao, Y.; Qiu, L.; Xu, W.; Huang, X.; Wei, H.; Tao, X. Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) Leaf-Fermentation Supernatant Inhibits Adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes and Suppresses Obesity in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Mo, Q.; Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Zhong, H.; Feng, F. Enhancement in the metabolic profile of sea buckthorn juice via fermentation for its better efficacy on attenuating diet-induced metabolic syndrome by targeting gut microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Yeboah, P.J.; Ayivi, R.D.; Eddin, A.S.; Wijemanna, N.D.; Paidari, S.; Bakhshayesh, R.V. A review and comparative perspective on health benefits of probiotic and fermented foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 4948–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose Carlos, D.L.-M.; Leonardo, S.; Jesús, M.-C.; Paola, M.-R.; Alejandro, Z.-C.; Juan, A.-V.; Cristobal Noe, A. Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus niger GH1 to Enhance Polyphenolic Content and Antioxidative Activity of Castilla Rose (Purshia plicata). Plants 2020, 9, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Qin, C.-Q.; Li, T.-T.; Liu, W.-H.; Ren, D.-F. Fermentation of rose residue by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum B7 and Bacillus subtilis natto promotes polyphenol content and beneficial bioactivity. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2022, 134, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Miao, S. Increases of Lipophilic Antioxidants and Anticancer Activity of Coix Seed Fermented by Monascus purpureus. Foods 2021, 10, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.-C.; Lin, S.-P.; Yu, C.-P.; Chiang, H.-M. Comparison of Puerariae Radix and Its Hydrolysate on Stimulation of Hyaluronic Acid Production in NHEK Cells. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2010, 38, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.-S.; Shin, K.-C.; Oh, D.-K. Production of ginsenoside compound K from American ginseng extract by fed-batch culture of Aspergillus tubingensis. AMB Express 2023, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.-S.; Kim, M.-J.; Shin, K.-C.; Oh, D.-K. Increased Production of Ginsenoside Compound K by Optimizing the Feeding of American Ginseng Extract during Fermentation by Aspergillus tubingensis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Kang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, C.; Hao, L.; Huang, J.; Lu, J.; Jia, S.; Yi, J. Antioxidant properties and digestion behaviors of polysaccharides from Chinese yam fermented by Saccharomyces boulardii. LWT 2022, 154, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yin, X.; Fang, Y.; Xiong, T.; Peng, F. Effect of Limosilactobacillus fermentum NCU001464 fermentation on physicochemical properties, xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity and flavor profile of Pueraria Lobata. Food Chem. 2025, 476, 143490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Hu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Meng, T. Study on Conversion of Conjugated Anthraquinone in Radix et Rhizoma Rhei by Yeast Strain. Mod. Tradit. Chin. Med. Mater. Medica-World Sci. Technol. 2013, 15, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.S.; Zhao, R.H. Effect of fermentation on the anthraquinones content in Radix et Rhizoma Rhei. Yunnan J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Mater. Medica 2005, 26, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, N.; Song, X.-R.; Kou, P.; Zang, Y.-P.; Jiao, J.; Efferth, T.; Liu, Z.-M.; Fu, Y.-J. Optimization of fermentation parameters with magnetically immobilized Bacillus natto on Ginkgo seeds and evaluation of bioactivity and safety. LWT 2018, 97, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-W.; Lim, J.-M.; Jeong, H.-J.; Lee, G.-M.; Seralathan, K.-K.; Park, J.-H.; Oh, B.-T. Lead (Pb) removal and suppression of Pb-induced inflammation by Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus A6-6. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 78, ovaf039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, H. Biosorption of Heavy Metals by Lactic Acid Bacteria for Detoxification. In Lactic Acid Bacteria Methods and Protocols, 2nd ed.; Kanauchi, M., Ed.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 2851, pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Ren, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. The Involvement of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Exopolysaccharides in the Biosorption and Detoxication of Heavy Metals in the Gut. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halttunen, T.; Salminen, S.; Tahvonen, R. Rapid removal of lead and cadmium from water by specific lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 114, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teemu, H.; Seppo, S.; Jussi, M.; Raija, T.; Kalle, L. Reversible surface binding of cadmium and lead by lactic acid and bifidobacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Sinha, V.; Kannan, A.; Upreti, R.K. Reduction of Chromium-VI by Chromium Resistant Lactobacilli: A Prospective Bacterium for Bioremediation. Toxicol. Int. 2012, 19, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Zhai, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Narbad, A.; Zhang, H.; Tian, F.; Chen, W. Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM639 alleviates aluminium toxicity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 100, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza Alizadeh, A.; Hosseini, H.; Mohseni, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Hashempour-Baltork, F.; Hosseini, M.-J.; Eskandari, S.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Aminzare, M. Bioremoval of lead (pb) salts from synbiotic milk by lactic acid bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labus, J.; Tang, K.; Henklein, P.; Krüger, U.; Hofmann, A.; Hondke, S.; Wöltje, K.; Freund, C.; Lucka, L.; Danker, K. The α1 integrin cytoplasmic tail interacts with phosphoinositides and interferes with Akt activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2024, 1866, 184257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, A.; Swamidason, J.T.E.Y.; Mariappan, P.; Bojan, V. Microbial degradation of flubendiamide in different types of soils at tropical region using lactic acid bacteria formulation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Zhao, M.; Xia, T.; Wang, Q.; Yu, J.; Qiao, C.; Zhang, H.; Lv, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M. Effect of Different Fermentation Methods on the Physicochemical, Bioactive and Volatile Characteristics of Wolfberry Vinegar. Foods 2025, 14, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Q.; Tan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, L.; Tang, J.; Xiang, W. Characterization of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-producing Saccharomyces cerevisiae and coculture with Lactobacillus plantarum for mulberry beverage brewing. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanklai, J.; Somwong, T.C.; Rungsirivanich, P.; Thongwai, N. Screening of GABA-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria from Thai Fermented Foods and Probiotic Potential of Levilactobacillus brevis F064A for GABA-Fermented Mulberry Juice Production. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, K.; Douglass, H.; Erritzoe, D.; Muthukumaraswamy, S.; Nutt, D.; Sumner, R. The role of GABA, glutamate, and Glx levels in treatment of major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 141, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, C.C.; Yoon, Y.; Yoo, H.S.; Oh, S. Effect of Lactobacillus fermentation on the anti-inflammatory potential of turmeric. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; He, X.; Xu, K.; Xue, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X. Platycodon grandiflorum root fermentation broth reduces inflammation in a mouse IBD model through the AMPK/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 3946–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Kang, C.-H.; Hwang, H.S. Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Astragalus membranaceus Fermented by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Cells. Fermentation 2021, 7, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Liu, S.; Ai, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Y. Fermented ginseng attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses by activating the TLR4/MAPK signaling pathway and remediating gut barrier. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, H.; Liu, H.; Cheng, H.; Pan, L.; Hu, M.; Li, X. Goji berry juice fermented by probiotics attenuates dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, N.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, Y. Mulberry leaf extract fermented with Lactobacillus acidophilus A4 ameliorates 5-fluorouracil-induced intestinal mucositis in rats. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 64, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sohaimy, S.A.; Shehata, M.G.; Mathur, A.; Darwish, A.G.; Abd El-Aziz, N.M.; Gauba, P.; Upadhyay, P. Nutritional Evaluation of Sea Buckthorn “Hippophae rhamnoides” Berries and the Pharmaceutical Potential of the Fermented Juice. Fermentation 2022, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.P.; Capozzi, V.; Russo, P.; Dridier, D.; Spano, G.; Fiocco, D. Immunobiosis and probiosis: Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria with a focus on their antiviral and antifungal properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9949–9958, Erratum in Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’cOnnor, P.M.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C.; Cotter, P.D. Antimicrobial antagonists against food pathogens: A bacteriocin perspective. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.M.; Yi, S.J.; Cho, I.J.; Ku, S.K. Red-Koji Fermented Red Ginseng Ameliorates High Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorders in Mice. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4316–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Bao, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Zhou, L.; Fu, Q. Fermented Gynochthodes officinalis (F.C.How) Razafim. & B.Bremer alleviates diabetic erectile dysfunction by attenuating oxidative stress and regulating PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 307, 116249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Shang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Xue, N.; Huang, C.; Li, F.; Li, J. Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Activity of Polygonatum sibiricum Fermented with Lactobacillus brevis YM 1301 in Diabetic C57BL/6 Mice. J. Med. Food 2021, 24, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Qu, Q.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.; Yang, P.; Han, L.; Shi, X. Monascus ruber fermented Panax ginseng ameliorates lipid metabolism disorders and modulate gut microbiota in rats fed a high-fat diet. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; You, Y.; Ai, Z.; Dai, W.; Piao, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Fermented ginseng improved alcohol liver injury in association with changes in the gut microbiota of mice. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 5566–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Li, Z.; Han, L.; Shi, X. Paecilomyces cicadae-fermented Radix astragali activates podocyte autophagy by attenuating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways to protect against diabetic nephropathy in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Jung, J.E.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.J.; Kim, H.Y. Effects of the fermented Zizyphus jujuba in the amyloid β25-35-induced Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nutr. Res. Pr. 2021, 15, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Liu, H.; Ma, R.; Ma, J.; Fang, H. Fermentation by Multiple Bacterial Strains Improves the Production of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Goji Juice. Molecules 2019, 24, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Liu, L.; Lai, T.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Z.; Xiao, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, M. Phenolic profile, free amino acids composition and antioxidant potential of dried longan fermented by lactic acid bacteria. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 4782–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; You, S.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, M. Protection Impacts of Coix lachryma-jobi L. Seed Lactobacillus reuteri Fermentation Broth on Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Yamano, S.; Imagawa, N.; Igami, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Ito, H.; Watanabe, T.; Kubota, K.; Katsurabayashi, S.; Iwasaki, K. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei A221-fermented ginseng on impaired spatial memory in a rat model with cerebral ischemia and β-amyloid injection. Tradit. Kamp-Med. 2019, 6, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-Y.; Choi, J.W.; Park, Y.; Oh, M.S.; Ha, S.K. Fermentation enhances the neuroprotective effect of shogaol-enriched ginger extract via an increase in 6-paradol content. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 21, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Qi, H.; Tang, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X.; Kong, Z.; Jia, S.; et al. Probiotic fermentation of Ganoderma lucidum fruiting body extracts promoted its immunostimulatory activity in mice with dexamethasone-induced immunosuppression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, X.; Rui, B.; Du, Y.; Lei, Z.; Guo, X.; Wang, C.; Yuan, D.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; et al. Probiotic Fermentation of Astragalus membranaceus and Raphani Semen Ameliorates Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppression Through Intestinal Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Dependent or -Independent Regulation of B Cell Function. Biology 2025, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, M.; Li, R.; Qu, Q.; Li, Z.; Feng, M.; Tian, Y.; Ren, W.; et al. Exploring the Prebiotic Potential of Fermented Astragalus Polysaccharides on Gut Microbiota Regulation In Vitro. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 82, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, B.; Guo, C.-E.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Qian, J.; Li, H. Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) fermentation liquid protects against alcoholic liver disease linked to regulation of liver metabolome and the abundance of gut microbiota. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 101, 2846–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Chu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Tang, S.; Zogona, D.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Lactobacillus casei Fermented Raspberry Juice In Vitro and In Vivo. Foods 2021, 10, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Zhou, L.; Ren, Y.; Liu, F.; Xue, Y.; Wang, F.-Z.; Lu, R.; Zhang, X.-J.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H.; et al. Lactic acid fermentation of goji berries (Lycium barbarum) prevents acute alcohol liver injury and modulates gut microbiota and metabolites in mice. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, P.; et al. Fermented Astragalus and its metabolites regulate inflammatory status and gut microbiota to repair intestinal barrier damage in dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1035912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzinger, S.; Grässel, S.; Dowejko, A.; Reichert, T.E.; Bauer, R.J. Induction of type XVI collagen expression facilitates proliferation of oral cancer cells. Matrix Biol. 2011, 30, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Song, W.-S.; Oh, D.-K. Enhanced production of ginsenoside compound K by synergistic conversion of fermentation with Aspergillus tubingensis and commercial cellulase. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1538031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi, R.S.; Dong, X.; Jiang, C.; Sun, Z.; Deng, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Mesa, A.; Huang, X.; et al. Antimicrobial activity and enzymatic analysis of endophytes isolated from Codonopsis pilosula. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; He, Y.; He, W.; Song, X.; Peng, Y.; Hu, X.; Bian, S.; Li, Y.; Nie, S.; Yin, J.; et al. Exploring the Biogenic Transformation Mechanism of Polyphenols by Lactobacillus plantarum NCU137 Fermentation and Its Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties in Wolfberry Juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 12752–12761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Xiong, L.; Hu, H.; Liu, H. Lactobacillus acidophilus-Fermented Jujube Juice Ameliorates Chronic Liver Injury in Mice via Inhibiting Apoptosis and Improving the Intestinal Microecology. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Guo, F.; Li, C.; Xiang, D.; Gong, M.; Yi, H.; Chen, L.; Yan, L.; Zhang, D.; Dai, L.; et al. Aqueous extract of fermented Eucommia ulmoides leaves alleviates hyperlipidemia by maintaining gut homeostasis and modulating metabolism in high-fat diet fed rats. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.-F.; Yu, W.-N.; Zhang, B.-L. Manufacture and antibacterial characteristics of Eucommia ulmoides leaves vinegar. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-H.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Shen, Y.-M. The fermentation of 50 kinds of TCMs by Bacillus subtilis and the assay of antibacterial activities of fermented products. Zhong Yao Cai 2006, 29, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Li, J.; Hong, Y.; Liang, P.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. iProbiotics: A machine learning platform for rapid identification of probiotic properties from whole-genome primary sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bai, M.; Liu, W.; Li, W.; Zhong, Z.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Dong, G.; Sun, Z. Predicting Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus-Streptococcus thermophilus interactions based on a highly accurate semi-supervised learning method. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Song, M.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; An, X.; Qi, J. The effects of solid-state fermentation on the content, composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of flavonoids from dandelion. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, G.; Ling, J. New flavonoid and their anti-A549 cell activity from the bi-directional solid fermentation products of Astragalus membranaceus and Cordyceps kyushuensis. Fitoterapia 2024, 176, 106013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, S.; Gurumurthy, K. An overview of probiotic health booster-kombucha tea. Chin. Herb. Med. 2023, 15, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Pitol, L.O.; Biz, A.; Finkler, A.T.J.; de Lima Luz, L.F.; Krieger, N. Design and Operation of a Pilot-Scale Packed-Bed Bioreactor for the Production of Enzymes by Solid-State Fermentation. In Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Steudler, S., Werner, A., Cheng, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 169, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhao, L.; Chen, L.; Shi, G.; Ding, Z. Refined regulation of polysaccharide biosynthesis in edible and medicinal fungi: From pathways to production. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 358, 123560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, W.; Luo, J.; Liu, L.; Peng, X. Lonicera japonica Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum Improve Multiple Patterns Driven Osteoporosis. Foods 2024, 13, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Suh, H.J.; Kang, C.-M.; Lee, K.-H.; Hwang, J.-H.; Yu, K.-W. Immunological Activity of Ginseng Is Enhanced by Solid-State Culture with Ganoderma lucidum Mycelium. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Jia, J.; Wu, Q. Bidirectional fermentation of Monascus and Mulberry leaves enhances GABA and pigment contents: Establishment of strategy, studies of bioactivity and mechanistic. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, L.; Xu, G. Bacillus subtilis and Bifidobacteria bifidum Fermentation Effects on Various Active Ingredient Contents in Cornus officinalis Fruit. Molecules 2023, 28, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, S.; Gouda, M.M.; Mubeen, B.; Imtiaz, A.; Murtaza, M.S.; Awan, K.A.; Rehman, A.; Alsulami, T.; Khalifa, I.; Ma, Y. Synergistic enhancement in the mulberry juice’s antioxidant activity by using lactic acid bacteria co-culture fermentation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Yan, L.; Jing, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Huang, Y. Insights into traditional Chinese medicine: Molecular identification of black-spotted tokay gecko, Gekko reevesii, and related species used as counterfeits based on mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene sequences. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2025, 35, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mei, R.; Zhao, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Surface enhanced Raman scattering tag enabled ultrasensitive molecular identification of Hippocampus trimaculatus based on DNA barcoding. Talanta 2025, 294, 128289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Liao, X.; Xi, Y.; Chu, Y.; Liu, S.; Su, H.; Dou, D.; Xu, J.; Xiao, S. Screening and Application of DNA Markers for Novel Quality Consistency Evaluation in Panax ginseng. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gan, X.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Li, T.; et al. Seasonal variation of antioxidant bioactive compounds in southern highbush blueberry leaves and non-destructive quality prediction in situ by a portable near-infrared spectrometer. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 139925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; He, F.; Hu, R.; Wan, X.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L.; Ho, C.-T.; Li, S. Dynamic Variation of Secondary Metabolites from Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua Rhizomes During Repeated Steaming–Drying Processes. Molecules 2025, 30, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, N.; Jankowska, M.; Nawrot, S.; Nogal-Nowak, K.; Wąsik, S.; Czerwonka, G. Phenotypic and Genetic Characterization and Production Abilities of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Strain 484—A New Probiotic Strain Isolated From Human Breast Milk. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Bi, C. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Insights into Its Genetic Diversity, Metabolic Function, and Antibiotic Resistance. Genes 2025, 16, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIFST Notice: Group Standard “General Principles for Probiotics in Food”. Available online: https://www.cifst.org.cn/a/ttbzglxt/bzfb/20220616/2478.html (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Walter, J.; Maldonado-Gómez, M.X.; Martínez, I. To engraft or not to engraft: An ecological framework for gut microbiome modulation with live microbes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turroni, F.; Özcan, E.; Milani, C.; Mancabelli, L.; Viappiani, A.; van Sinderen, D.; Sela, D.A.; Ventura, M. Glycan cross-feeding activities between bifidobacteria under in vitro conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, J.E.; Cosetta, C.M.; Reens, A.L.; Brooker, S.L.; Rowan-Nash, A.D.; Lavin, R.C.; Saur, R.; Zheng, S.; Autran, C.A.; Lee, M.L.; et al. Precision modulation of dysbiotic adult microbiomes with a human-milk-derived synbiotic reshapes gut microbial composition and metabolites. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 1523–1538.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, C.; et al. Heavy Metal Contaminations in Herbal Medicines: Determination, Comprehensive Risk Assessments, and Solutions. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 595335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-J.; Zhang, W.-S.; Wu, J.-S.; Xin, W.-F. Research progress of pesticide residues in traditional Chinese medicines. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2019, 44, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Pant, K.; Brar, D.S.; Thakur, A.; Nanda, V. A review on Api-products: Current scenario of potential contaminants and their food safety concerns. Food Control 2022, 145, 109499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kodama, K.; Sengoku, S. The Co-Evolution of Markets and Regulation in the Japanese Functional Food Industry: Balancing Risk and Benefit. Foods 2025, 14, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galai, K.E.; Dai, W.; Qian, C.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, M.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Isolation of an endophytic yeast for improving the antibacterial activity of water chestnut Jiaosu: Focus on variation of microbial communities. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2025, 184, 110584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Gan, Q.; Ruan, W.; Liu, T.; Yan, Y. Leveraging artificial intelligence for efficient microbial production. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 439, 133286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yin, J.; Ding, L.; Li, P.; Xiao, H.; Gu, Q.; Han, J. New perspectives on key bioactive molecules of lactic acid bacteria: Integrating targeted screening, key gene exploration and functional evaluation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaposhnikov, L.A.; Rozanov, A.S.; Sazonov, A.E. Genome-Editing Tools for Lactic Acid Bacteria: Past Achievements, Current Platforms, and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, R.; Zarimeidani, F.; Ghanbari Boroujeni, M.R.; Sadighbathi, S.; Kashaniasl, Z.; Saleh, M.; Alipourfard, I. CRISPR-Assisted Probiotic and In Situ Engineering of Gut Microbiota: A Prospect to Modification of Metabolic Disorders. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Pan, X.; Gong, Z.; Jiang, J.-H.; Chu, X. Engineered Probiotics Secreting IL-18BP and Armed with Dual Single-Atom Catalysts for Synergistic Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 50337–50348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xie, W. Chinese expert consensus on the application of live combined Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus powder/capsule in digestive system diseases (2021). J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 38, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QB/T 5760-2023; Edible Composite Jiaosu. China Light Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Liu, D.; Jin, K.; Peng, J. An improved deep convolutional generative adversarial network for quantification of catechins in fermented black tea. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 327, 125357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Holscher, H.D.; Maslov, S.; Hu, F.B.; Weiss, S.T.; Liu, Y.-Y. Predicting metabolite response to dietary intervention using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Piao, X.; Mahfuz, S.; Long, S.; Wang, J. The interaction among gut microbes, the intestinal barrier and short chain fatty acids. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 9, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikel, S.; Valdez-Lara, A.; Cornejo-Granados, F.; Rico, K.; Canizales-Quinteros, S.; Soberón, X.; Del Pozo-Yauner, L.; Ochoa-Leyva, A. Combining metagenomics, metatranscriptomics and viromics to explore novel microbial interactions: Towards a systems-level understanding of human microbiome. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, H.; Bu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, W.; Han, F. Comprehensive Advances on Probiotic-Fermented Medicine and Food Homology. Fermentation 2025, 11, 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120682

Dong H, Bu D, Cheng Y, Gao W, Han F. Comprehensive Advances on Probiotic-Fermented Medicine and Food Homology. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120682

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Huijun, Derui Bu, Yutong Cheng, Wen Gao, and Fubo Han. 2025. "Comprehensive Advances on Probiotic-Fermented Medicine and Food Homology" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120682

APA StyleDong, H., Bu, D., Cheng, Y., Gao, W., & Han, F. (2025). Comprehensive Advances on Probiotic-Fermented Medicine and Food Homology. Fermentation, 11(12), 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120682