Abstract

Enteric methane (CH4) emissions from ruminants contribute significantly to agricultural greenhouse gases. Anti-methanogenic feed additives (AMFA), such as Asparagopsis spp. and 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP), reduce CH4 emissions by inhibiting methanogenic enzymes. However, CH4 inhibition often leads to dihydrogen (H2) accumulation, which can impact rumen fermentation and decrease dry matter intake (DMI). Recent studies suggest that co-supplementation of CH4 inhibitors with alternative electron acceptors, such as phloroglucinol, fumaric acid, or acrylic acid, can redirect excess H2 during methanogenesis inhibition into fermentation products nutritionally beneficial for the host. This review summarizes findings from rumen simulation experiments and in vivo trials that have investigated the effects of combining a CH4 inhibitor with an alternative H2 acceptor to achieve effective methanogenesis inhibition. These trials demonstrate variable outcomes depending on additive combinations, inclusion rates, and adaptation periods. The use of phloroglucinol in vivo consistently decreased H2 emissions and altered fermentation patterns, promoting acetate production, compared with fumaric acid or acrylic acid as alternative electron acceptors. As a proof-of-concept, phloroglucinol shows promise as a co-supplement for reducing CH4 and H2 emissions while enhancing volatile fatty acid profiles in vivo. Optimizing microbial pathways for H2 utilization through targeted co-supplementation and microbial adaptation could enhance the sustainability of CH4 mitigation strategies using feed additive inhibitors in ruminants. Further research using multi-omics approaches is needed to elucidate the microbial mechanisms underlying the redirection of H2 toward beneficial fermentation products during enteric methanogenesis inhibition. This knowledge will help guide the formulation of novel co-supplements designed to reduce CH4 emissions and improve energy efficiency for sustainable livestock production.

1. Background

Several strategies have been explored in recent years to mitigate enteric methane (CH4) emissions, with the use of anti-methanogenic feed additives (AMFA) increasingly recognized as the most potent abatement approach for ruminants [1,2,3]. These feed additives, including CH4 inhibitors and rumen modifiers, can significantly reduce enteric CH4 emissions, primarily by direct inhibition of methanogen-specific enzymes, indirect modulation of rumen fermentation, or both [4]. Notably, supplementation with the red macroalgae Asparagopsis spp. or the synthetic compound 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) has consistently achieved reductions in enteric CH4 emissions by more than 20% in ruminants [4]. The CH4 reduction effect of Asparagopsis is mainly attributed to bromoform (CHBr3), the major active ingredient present at up to 100-fold the level of any other component, such as dibromochloromethane [5]. Bromoform acts by competitively inhibiting coenzyme M methyltransferase and methyl coenzyme M reductase (MCR), enzymes used by the methanogenic archaea in the reduction of one- or two-carbon substrates with dihydrogen (H2) to produce CH4 [6]. Similarly, synthetic inhibitors such as iodoform [7,8], 2-bromoethanesulfonate (BES; [9]), and 3-NOP [10] specifically target MCR, a key enzyme shared by all CH4 production pathways, thereby affecting all methanogens [11]. Nitrate is also an effective synthetic feed additive for mitigating CH4, both in vitro and in vivo [12,13]. Dietary nitrate supplementation reduced CH4 emissions in in vivo studies [12,14], largely due to the direct toxic effect of the ingredient, which inhibits methanogenic microbial activity [13]. In addition to reducing enteric CH4 emission, these feed additive inhibitors may also impact on dry matter intake (DMI), weight gain, or milk production in ruminant livestock [4].

The inhibition of enteric methanogenesis with CH4 inhibitors alters the metabolism of rumen microbial communities [11]. This results in increased H2 emission in vivo [15], increased accumulation of H2 in vivo [16,17], and, sometimes, increased ruminal levels of intermediate electron carriers such as ethanol, formate [16,18], and lactate [19]. Accumulation of H2 due to CH4 inhibitor supplementation has both positive and negative effects on hydrogenogenic and hydrogenotrophic ruminal microorganisms [20]. The concentration of ruminal H2 centrally regulates the proportions of fermentative end-products, as indicated by the metabolic interactions among fermentative bacteria and between hydrogenogenic bacteria and hydrogenotrophic methanogens [21]. Enteric methanogenesis is an evolutionary adaptation that limits the accumulation of ruminal H2 resulting from fiber degradation [22], as high ruminal H2 partial pressure would otherwise impair microbial carbohydrate digestion [23,24]. Under typical conditions, methanogenic archaea utilize H2 to produce CH4 [11], which indirectly sustains the fermentation process and mitigates the negative feedback inhibition of excess H2 on the degradation of dry matter in the rumen [23]. Thus, the removal of H2 enables the re-oxidation of NADH to NAD+, which occurs through the transfer of electrons released from the oxidation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to 1, 3-diphosphoglycerate during glycolysis, a process essential for the continuation of hexose catabolism in the rumen [25,26]. The health and productivity of animals can be negatively impacted by disruptions to the rumen microbiome, which facilitate these reactions [21]. Therefore, to preserve feed conversion and animal productivity, dietary intervention strategies that manipulate the rumen microbial environment to inhibit methanogenesis require careful consideration [27].

Mitigation strategy using feed additives to reduce rumen methanogenesis requires a consistent and sustained reduction in CH4 emissions from ruminants without negatively affecting animal health, welfare, or productivity [1,11,28]. However, studies have shown that feed additive inhibitors reduce enteric methanogenesis and often increase ruminal H2 emissions [12,29,30,31], suggesting that this is a consequence of direct inhibition of ruminal CH4 production [32]. Increased enteric H2 emission indicates higher dissolved H2 levels in the rumen, associated with a reduced redox state [33]. A surplus of electron donors from H2 accumulation during the inhibition of rumen methanogenesis can impact optimal microbial fermentation and synthesis [23,32], potentially leading to negative effects on animal performance as reflected in decreased feed intake [31]. The challenge with using inhibitors to reduce enteric CH4 emissions is the inefficiency of the rumen microbiome in capturing and redirecting excess H2 spared by methanogenesis inhibition into alternative metabolic pathways for the synthesis of metabolites usable by ruminants [34,35]. This indicates that the rumen system can still be optimized to improve animal productivity by feeding novel substrates to modify rumen microbiome and redirect H2 towards the production of beneficial fermentation products [36]. Thus, co-supplementation of an alternative electron sink with higher H2 affinity during methanogenesis inhibition would be a promising strategy for a robust mitigation of enteric CH4 emissions in ruminants. For example, microbial reduction of phloroglucinol or fumaric acid could provide a pathway to incorporate increased H2 produced under methanogenesis inhibition conditions into the production of acetate or propionate, an energy-yielding product used by the animal [32,35]. The metabolic fate and significance of the absorbed alternative electron sink may affect the beneficial effects on animal productivity during enteric methanogenesis inhibition. This depends on the nutritional requirements of each animal species and the energy savings achieved through H2 incorporation [37]. Previous literature postulated that co-supplementation of a feed additive inhibitor with an alternative electron sink would significantly reduce CH4 production without a concomitant increase in H2 accumulation or emissions, thereby mitigating the negative effects of methanogenesis inhibition on fermentation and animal performance [35,38,39]. Hence, this current review summarized recent findings from rumen simulation experiments and in vivo trials that have investigated the effects of combining a CH4 inhibitor with an H2 acceptor to achieve effective inhibition of methanogenesis. Although the data were insufficient for meta-analysis, a direct comparison of variances across trials was used to highlight significant findings.

Scope of the Review

This review examines the integrated approach of co-supplementing methanogenesis inhibitors with alternative H2 acceptors to enhance CH4 mitigation in vitro and in ruminants. It synthesizes findings from limited in vitro rumen simulation studies and in vivo trials that evaluated the combined effects of inhibitors such as Asparagopsis spp., BES, 3-NOP, and nitrate with electron acceptors like phloroglucinol, fumaric acid, and acrylic acid. The review focuses on the impact of such combinations on CH4 and H2 emissions, fermentation parameters, microbial communities, and production parameters. It highlights dose-dependent responses, adaptation periods, and microbial interactions that influence H2 redirection toward beneficial metabolites, such as acetate and propionate. By comparing outcomes across studies, this review identifies knowledge gaps and emphasizes the need for future research to use multi-omics approaches to understand microbial dynamics and inform the formulation of robust co-supplements to sustainably mitigate CH4 emissions without compromising animal productivity.

2. Integrated Approach: Co-Supplementation of a Methane Inhibitor with an Alternative H2 Acceptor In Vitro and In Vivo

Only a small number of laboratory experiments and animal studies have explored the synergistic effects of methanogenesis inhibitors and alternative electron acceptors on fermentation parameters, CH4 production, and H2 accumulation or emissions (Table 1). The in vitro rumen simulation experiments by Huang et al. [38] and Romero et al. [35] evaluated the effects of CH4 inhibitors (Asparagopsis or BES) used alone or with an alternative electron acceptor (phloroglucinol) on CH4 production, H2 accumulation, fermentation parameters, and microbial communities. These in vitro experiments confirmed the inhibitory potential of individual CH4 inhibitors at different concentrations, which increased H2 accumulation and substantially decreased CH4 production, total VFA, and the acetate-to-propionate (A:P) ratio [35,38]. Huang et al. [38] showed that phloroglucinol supplemented alone and in combination with BES decreased CH4 production, propionate production, and H2 accumulation, as well as increased acetate production, total VFA and A:P ratio compared to the CH4 inhibitor-only treatment. In Huang et al. [38], the intensity of the impacts of co-supplementation on CH4 production, fermentation parameters, and H2 accumulation increased with the accelerated inclusion of phloroglucinol up to 36 mM. Similarly, Romero et al. [35] demonstrated the effects of CH4 inhibitor-only (Asparagopsis) and co-supplementation with the increasing doses of phloroglucinol (6, 16, 26 and 36 mM) on CH4 production, H2 accumulation, and fermentation parameters. Supplementation of Asparagopsis at 2% DM of substrate with increasing doses of phloroglucinol (6, 16, 26, and 36 mM) linearly decreased CH4 production, propionate production, and H2 accumulation, while increasing acetate production, total VFA, and A:P ratio [35]. Thorsteinsson et al. [32] examined the effects of nitrate or Asparagopsis with and without fumaric acid as an alternative electron acceptor on CH4 production and H2 accumulation in vitro. Thorsteinsson et al. [32] found that supplementation with nitrate alone reduced CH4 production without resulting in detectable levels of H2 production. The combination of nitrate and fumaric acid has not further decreased CH4 production compared to the nitrate-only treatment, thus making it impossible to evaluate the effect of nitrate with fumaric acid co-supplementation on H2 production [32]. Thorsteinsson et al. [32] speculated that all available dissolved H2 was used for nitrate reduction to ammonia or other competing pathways, explaining the lack of increased H2 levels in the nitrate treatment. However, Thorsteinsson et al. [32] reported that supplementation of Asparagopsis with fumaric acid significantly reduced CH4 production resulting in insignificant change in H2 production (Table 1). There was no synergistic effect of supplementing Asparagopsis with fumaric acid on H2 production in Thorsteinsson et al. [32]. Severe inhibition of methanogenesis by Asparagopsis, with or without fumaric acid, had no effect on dry matter degradability at any incubation period compared to the control, suggesting that the excess H2 produced may have been redirected in the production of other metabolites, such as propionate and butyrate, through pathways that have not been analyzed in Thorsteinsson et al. [32]. In a recent in vitro study, Battelli et al. [39] observed a different interaction where none of the combinations of CH4 inhibitor (Iodoform or Quercetin) with alternative H2-acceptor (activated charcoal powder, phloroglucinol, or vitamin E) demonstrated a synergistic effect to reduce H2 production and improve fermentation parameters (Table 1). However, a co-supplementation of CH4 inhibitors, including Iodoform and Quercetin (Table 1), significantly decreased CH4 production and numerically reduced H2 production without impacts on the total VFA concentrations compared to the control [39]. The synergistic effect between these CH4 inhibitors could be due to complementary mechanisms of action, where Quercetin reduces protozoan abundance [40] and modulates microbial fermentation [41], while Iodoform targets and inhibits specific methanogenic enzymes [8,30]. The inclusion of Quercetin could indirectly limit CH4 production by reducing the abundance of protozoa and thus decreasing interspecies H2 transfer to methanogens for methanogenesis [39]. Microbial degradation of Quercetin to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate in the rumen also consumes H2 or formate, which could act as a competing electron sink and reduce the availability of H2 for CH4 production [42,43].

Table 1.

Summary of the experiments demonstrating effects of co-supplementation of methane inhibitors with alternative hydrogen acceptors on dihydrogen accumulation or emission during methanogenesis inhibition.

Furthermore, the publications by Maigaard et al. [44] and Romero et al. [36] reported effects of combined supplementation of CH4 inhibitors and alternative H2 acceptors on rumen fermentation, enteric CH4 and H2 emissions, and animal performance in vivo (Table 1). Maigaard et al. [44] reported that co-supplementation of 3-NOP (60 mg/kg of DM) with fumaric acid (390 g/d), acrylic acid (242 g/d), or phloroglucinol (480 g/d) as an alternative electron acceptor, significantly reduced CH4 emissions and numerically decreased H2 emissions without pronounced effects on total VFA in lactating dairy cows fed high-forage diets. The co-supplementation of 3-NOP (60 mg/kg of DM) with phloroglucinol (480 g/d) had no pronounced effect on the DMI, but co-supplementation with fumaric acid (390 g/d) or acrylic acid (242 g/d) significantly increased propionate production and significantly reduced the A:P ratio [44]. Consistently, supplementation of fumaric acid-only reduced CH4 emissions and shifted rumen fermentation patterns towards a higher proportion of propionate, lower A:P ratio, and decreased total VFA in goats fed low and high forage diets [45], as also found by [44]. However, the anti-methanogenic co-supplementation of nitrate (15 g/kg of DM) with fumaric acid (390 g/d), acrylic acid (242 g/d), or fumaric acid (195 g/d) plus acrylic acid (121 g/d) had no significant effects on CH4 and H2 emissions, but improved DMI except for co-supplementation with acrylic acid in dairy cows [44]. The numerical reduction in H2 emissions in vivo, observed with the co-supplementation of nitrate and fumaric acid in Maigaard et al. [44], agrees with the previous findings using similar ingredients in vitro [32]. Romero et al. [36] demonstrated that inclusion of 2% DM Asparagopsis with phloroglucinol at up to 20 g/kg DM/d, a rumen equivalent concentration of 36 mM/d, in high-forage diets reduced CH4 and H2 emissions compared to the control without negative impacts on rumen fermentation and DMI in dairy goats. Moreover, in vivo supplementation with phloroglucinol, with or without Asparagopsis, shifted fermentation patterns towards a higher proportion of acetate and an increased A:P ratio, and a lower proportion of propionate [36]. Comparatively, a previous rumen simulation study [35] used Asparagopsis (dosed at 2% DM) with phloroglucinol (dosed at 36 mM) and found a more pronounced decrease in CH4 production (−100%) and H2 accumulation (−46%) compared to the reductions observed (Table 1) in dairy goats fed similar ingredients at the same concentrations in Romero et al. [36]. This discrepancy could be due to the differences between in vitro and in vivo experimental conditions. Overall, there is a paucity of data on the in vivo evaluation of co-supplementation with a CH4 inhibitor and an alternative H2 acceptor.

There is limited data on the response of microbiota to co-supplementation with a CH4 inhibitor and an alternative H2 acceptor, both in vitro and in vivo. Published in vitro studies by Huang et al. [38] and Romero et al. [35] reported the effects of co-additives on microbiota composition in rumen fluid inoculum from lactating cows and dairy goats. An interesting analysis by Huang et al. [38] found that phloroglucinol alone (dosed at 36 mM), or in combination with the methanogenesis inhibitor BES (dosed at 3 μM) in a 72 h incubation using rumen fluid from dairy cows, reduced archaeal methanogens abundance and increased bacterial abundance, without affecting the population of fungi or protozoa, compared to the control cultures. Supplementation of phloroglucinol at a 36 mM inclusion level, combined with 2% DM Asparagopsis, significantly decreased the abundances of methanogenic archaea, fungi, and protozoa, without affecting the bacterial population, after 5-day incubation in rumen fluid from dairy goats, compared to the Asparagopsis-only treatment [35]. However, co-supplementation of phloroglucinol at 36 mM and 2% DM Asparagopsis tended to decrease total bacterial abundance and had no effect on populations of anaerobic fungi, archaea, and protozoa in goats [36]. The effectiveness of these co-additives, such as phloroglucinol with Asparagopsis, on the microbiota composition has shown large variation between in vitro and in vivo studies, as analyzed using quantitative (q)PCR. In the in vitro experiment, Romero et al. [35] observed a reduction in methanogenic archaea, fungi, and protozoa in treatment cultures supplemented with a combination of 36 mM phloroglucinol and 2% DM Asparagopsis, whereas Romero et al. [36] indicated the absence of noticeable effects on rumen microbiome using a similar concentration of the same co-additives in goats. This may be due to the differences between in vitro and in vivo conditions.

The short-term supplementation of a CH4 inhibitor with an alternative H2 acceptor (fumaric acid or phloroglucinol), in in vivo trials, had no effects on production parameters such as feed intake in goats [36] and dairy cows [44]. Maigaard et al. [44] observed transient decreased DMI in cows fed supplementation of acrylic acid with nitrate or 3-NOP, where the reduction appeared acute and reversed over days of the short experimental periods. The typical effect of individual supplementation with methanogenesis inhibitors on DMI, associated with the accumulation of excess H2 in the rumen [46], was potentially mitigated by co-supplementation with phloroglucinol [36] and with fumaric or acrylic acid [44]. However, these trials lasted only for short experimental periods and involved small sample sizes [36,44], which impede adequate assessment of the impacts of co-supplements on animal productivity. Future research should evaluate the impacts of supplementing a CH4 inhibitor with an alternative H2 acceptor on production parameters in growing or lactating ruminants, including trials with large sample sizes and ad libitum feeding conducted over long-term experimental periods [36]. Long-term trials with feed additives are also important for evaluating the negative effects of supplementation on animal health and safety [47]. Notably, it is essential to monitor indicators of pathology in living animals, such as blood inflammation markers and feed refusal, and to perform visual and histological examinations in slaughtered animals, as some AMFA used in feeding trials could have a positive, negative, or no effect on animal health [47].

3. Potentials of H2 Acceptor Co-Supplementation for Enhanced Methanogenesis Inhibition

The effectiveness of a CH4 inhibitor with an alternative H2 acceptor has shown a wide variation across in vitro and in vivo studies due to differences in inclusion rates of the feed additives, ration formulation, duration of adaptation to the ingredients, and animal species or source of the rumen fluid inoculum for in vitro experiments (Table 1). Several metabolic pathways have been identified as alternative electron sinks for excess H2 produced by methanogenesis inhibition, including microbial degradation of fumaric acid [44], acrylic acid [44], or phloroglucinol [36]. The dietary co-supplementation with alternative electron sinks stimulates rumen microbial groups that use H2 as a reductant to metabolize these additives into nutritionally usable products for the animal, thereby decreasing excess H2 accumulation. This minimizes digestible energy losses from ruminal greenhouse gas production while avoiding fermentation inhibition and thus is probably an excellent methanogenesis-inhibition strategy [48]. For example, co-supplementation with fumaric acid or acrylic acid increases the proportion of propionate, while inclusion of phloroglucinol promotes acetate production in vivo (Table 1), which are energy-yielding products nutritionally beneficial to the host. Succinate-forming bacteria in the rumen use H2 or formate as an electron donor to reduce fumaric acid into succinic acid, which is further decarboxylated to propionate via the succinate-propionate pathway. This process limits the availability of H2 for CH4 production. In this reduction, 1 mole of H2 is consumed for every mole of fumaric acid converted to succinic acid [49]. Fumaric acid reduction occurs when the population of succinate-forming bacteria is sufficiently large, and the H2 partial pressure is high, as these ruminal microbes have a lower affinity for H2 than methanogenic archaea [50]. Similarly, acrylic acid is reduced to propionate via a different mechanism, the acrylate pathway, and 1 mole of H2 is consumed for every mole of acrylic acid reduction process [51]. Maigaard et al. [44] observed an increased proportion of propionate in nitrate (15 g/kg DM/d) or 3-NOP (60 mg/kg DM/d) co-supplementation with fumaric acid (390 g/d) or acrylic acid (242 g/d), which suggests that some H2 was redirected to the reduction of fumaric acid and acrylic acid to propionate (Table 1). Moreover, inclusion of phloroglucinol facilitated the incorporation of accumulated H2 during biotransformation of the additive into VFA, particularly acetate [38]. Huang et al. [38] also found that the molar proportions of isobutyrate and isovalerate, which are produced from the deamination of branched-chain amino acids and function as a carbon skeleton in the production of branched-chain amino acids [52], were reduced by the supplementation of phloroglucinol, with or without BES. Increased synthesis or reduced degradation of branched-chain amino acids in the rumen may enhance the amount of these amino acids available for productive functions in the small intestine of the host ruminant [38]. Rumen microbes such as Eubacterium oxidoreducens spp. and Coprococcus spp. can use formate or H2 as an electron donor to reduce phloroglucinol, producing VFA, particularly acetate [53,54]. Tsai et al. [55] indicated that one molecule of H2 is utilized to degrade one molecule of phloroglucinol to produce two molecules each of acetate and CO2. Notably, different phloroglucinol reductases from anaerobic fermenting bacteria, classified within the NADPH-dependent short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases family, catalyze the reduction of phloroglucinol to dihydrophloroglucinol (DHP), which is followed by hydrolytic ring cleavage of DHP to form 3-hydroxy-5-oxohexanoate and then subsequently converted to acetate and butyrate as end products [53,56]. When supplemented at sufficient concentration, phloroglucinol serves as an alternative H2 acceptor, allowing excess H2 produced from methanogenesis inhibition to be redirected into useful products for the host ruminant [38]. Huang et al. [38] demonstrated that, under equivalent CH4 inhibition using BES (3 μM), co-supplementation with a higher dose of phloroglucinol at 36 mM resulted in a more pronounced reduction of H2 accumulation compared to a lower dose (6 mM) of an alternative electron acceptor. The low H2 recovery, concomitant with an increased A:P ratio due to a higher proportion of acetate in an accelerated dose of an alternative electron acceptor in BES (3 μM) plus Phloroglucinol (36 mM) treatment, indicated a reduction of phloroglucinol to acetate [38]. Microbial degradation of phloroglucinol by Coprococcus spp. results in the production of acetate and CO2 [54], while Eubacterium oxidoreducens reduces phloroglucinol to acetate and butyrate as end products [53]. However, the bacteria that catabolise phloroglucinol as a substrate, including Coprococcus spp., Eubacterium oxidoreducens, and Streptococcus ovis [42,54], are present at low abundance in the rumen [38]. Hence, a long-term adaptation of the rumen microbiota is necessary to promote the growth of such bacteria for effective degradation of phloroglucinol, using H2 to deliver reducing equivalents. Published in vitro studies showed that a sequential batch incubation for a longer duration (3–5 d) using phloroglucinol as an alternative H2 acceptor and BES or Asparagopsis as the CH4 inhibitor decreased metabolic hydrogen recovery and increased total VFA and acetate production compared to shorter (24-h) incubations [35,38]. Romero et al. [36] adapted dairy goats to diets containing increasing concentrations of phloroglucinol (5, 10, 15, and 20 g/kg DM) for 10 d, which resulted in insignificant difference in H2 emissions. Similarly, the study by Maigaard et al. [44] found no interaction between co-supplementation of 3-NOP (60 mg/kg DM/d) with phloroglucinol (480 g/d) and H2 emissions, potentially due to the 7-d short period for ingredient adaptation in the rumen. Therefore, a long adaptation (≥10 d) to a supplemented feed in vivo or longer incubation times in vitro could favor the optimal growth of bacteria able to metabolize phloroglucinol or other compound acting as alternative electron acceptors to reduce H2 accumulation during methanogenesis inhibition. In addition, long-term experiments are crucial to determine whether the antimethanogenic effects of feed additives persist over time and to assess if the rumen microbiome or metabolic processes develop adaptations that reduce efficacy [47]. Hristov et al. [47] recently suggested that studies testing the efficacy of feed additives on CH4 reduction in ruminants should preferably span a full production cycle, depending on the production system (beef or dairy), or at least a minimum experimental length of 12 to 15 weeks (≥84 d).

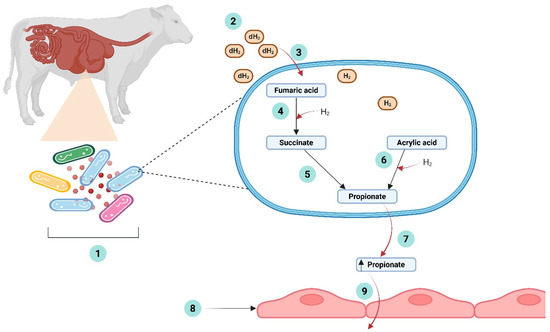

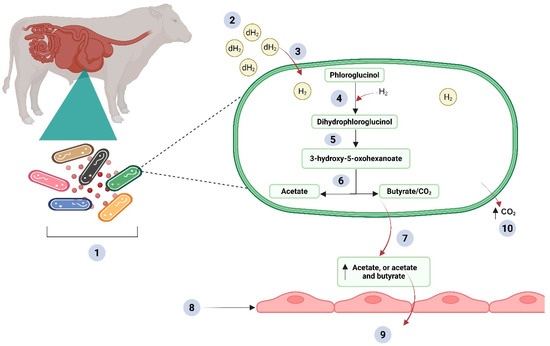

Although different combinations of CH4 inhibitors and alternative H2 acceptors have been recently explored in vitro and in vivo (Table 1), including co-supplementation of Asparagopsis with phloroglucinol, BES with phloroglucinol [35,38], nitrate with fumaric acid or acrylic acid [44], iodoform with activated charcoal powder, vitamin E, or phloroglucinol [39], and 3-NOP with phloroglucinol [44]. Dietary co-supplementation with alternative electron acceptors, such as fumaric acid or acrylic acid, increases ruminal propionate levels (Figure 1), whereas phloroglucinol mainly increases ruminal acetate production (Figure 2). These shifts in fermentation patterns not only consumed excess H2 during methanogenesis inhibition but also increased the levels of energy-yielding precursors in animals, which could consequently improve feed efficiency. Propionate serves as the main precursor for gluconeogenesis and is the primary energy source for weight gain and lactose production, while acetate provides the carbon required for milk fat synthesis in ruminants [57]. The low efficacy in H2 reduction from fumaric acid or acrylic acid co-supplementation in lactating dairy cows [44] seems to result from incomplete conversion of these organic acids, which is typical of reduced efficiency in slow-growing, low-numbers ruminal microbiota after a short adaptation period. The use of phloroglucinol in vivo consistently decreased H2 emissions compared to dietary co-supplementation with fumaric acid or acrylic acid as an alternative electron acceptor, as shown in Table 1. This suggests that ruminal degradation of phloroglucinol can more effectively redirect excess H2 into beneficial fermentation products than fumaric acid or acrylic acid. However, animals supplemented with phloroglucinol alone showed a higher decrease in H2 emissions than those fed a co-supplementation of a CH4 inhibitor with phloroglucinol, suggesting that further optimization of this nutritional strategy may still be possible [36]. The response of H2 emissions in dairy goats [36] and lactating dairy cattle [44] to co-supplementation with phloroglucinol provides a proof of concept and suggests that combining a CH4 inhibitor and phloroglucinol as dietary supplements can be used across different ruminant species. Although this co-supplementation with phloroglucinol would need further confirmation using animal experiments in different production settings. Future research is warranted using multi-omics (metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, and metaproteomics) to establish a deep understanding of the effects of a methanogenesis inhibitor with an alternative H2 sink (e.g., phloroglucinol or any co-additive) in vivo. This should elucidate the effects of co-supplementation on ruminal microbes, mechanisms, microbial gene expression, enzymes, and metabolic pathways involved in redirecting H2 toward beneficial fermentation products during methanogenesis inhibition in the rumen. Findings from these analyses will guide the formulation of novel co-additives designed to reduce enteric CH4 and improve energy efficiency for sustainable livestock production.

Figure 1.

A schematic illustrating the pathways involved in the degradation of fumaric acid and acrylic acid, highlighting the redirection of excess dihydrogen (H2) by organic acid-utilizing bacteria during the inhibition of methanogenesis in the rumen. (1) Microbial degradation of fumaric acid and acrylic acid by organic acid-utilizing bacteria in the rumen. (2) Increased concentrations of dissolved dihydrogen (dH2) during the inhibition of methanogenesis. (3) Capture of excess dihydrogen (H2) for the reduction of organic acid (fumaric acid or acrylic acid) by ruminal bacteria. (4) Reduction of fumaric acid to succinate using incorporated dihydrogen (H2) as an electron donor by organic acid-utilizing bacteria in the rumen. (5) Decarboxylation of succinate to propionate via succinate-propionate pathway. (6) Reduction of acrylic acid to propionate using incorporated dihydrogen (H2) as an electron donor, via the acrylate pathway. (7) Increased propionate production. (8) Rumen wall. (9) Absorption of propionate through the rumen wall. Created in BioRender: Ahmad, I. (2025) http://BioRender.com/cmqasgs.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustrating the pathways involved in the degradation of phloroglucinol, highlighting the redirection of excess dihydrogen (H2) by phloroglucinol-utilizing bacteria during the inhibition of methanogenesis in the rumen. (1) Microbial degradation of phloroglucinol by bacteria in the rumen. (2) Increased concentrations of dissolved dihydrogen (dH2) during the inhibition of methanogenesis. (3) Capture of excess dihydrogen (H2) for the reduction of phloroglucinol by ruminal bacteria. (4) Reduction of phloroglucinol to dihydrophloroglucinol using incorporated dihydrogen (H2) as an electron donor, catalyzed by NADPH-dependent short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases. (5) Hydrolysis of dihydrophloroglucinol to 3-hydroxy-5-oxohexanoate. (6) Conversion of 3-hydroxy-5-oxohexanoate primarily results in acetate and carbon dioxide (CO2) production when degraded by Coprococcus spp., or acetate and butyrate when degraded by Eubacterium oxidoreducens. (7) Increased acetate or acetate and butyrate production. (8) Rumen wall. (9) Absorption of acetate or acetate and butyrate through the rumen wall. (10) Increased carbon dioxide (CO2) production. Created in BioRender: Ahmad, I. (2025) https://BioRender.com/cfd68sv.

4. Conclusions

Anti-methanogenic feed additive inhibitors effectively reduce enteric CH4 emissions but often lead to H2 accumulation, which can impair rumen fermentation and animal performance. Thus, an approach to stimulate enteric microbial groups capable of capturing excess H2 via alternative energy-yielding metabolic pathways in the rumen should be considered when inhibiting CH4 emissions from livestock. Dietary co-supplementation with alternative electron acceptors such as phloroglucinol, fumaric acid, or acrylic acid offers a promising strategy to redirect excess H2 into beneficial fermentation products during methanogenesis inhibition. However, outcomes vary across studies due to differences in additive combinations, dosages, and adaptation periods. Phloroglucinol, used as a co-supplement with Asparagopsis, or 3-NOP, shows strong potential to reduce H2 emissions and improve VFA profiles in vivo. Future research should explore long-term microbial adaptation and the use of multi-omics analyses to gain a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between electron sink-utilizing bacteria abundances and rumen dynamics, with the aim of optimizing H2 utilization pathways during enteric methanogenesis inhibition. Developing a tailored supplementation strategy of a CH4 inhibitor with an alternative H2 acceptor could enhance CH4 mitigation while preserving or improving animal health and feed efficiency. While co-supplementation with alternative H2 acceptors, particularly phloroglucinol, may enhance mitigation of enteric CH4 emissions in ruminant livestock, the cost of the quantities required to achieve a robust daily reduction in ruminal greenhouse gas emissions will be impractical for on-farm adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: I.A.; methodology, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation: I.A.; writing—review and editing: I.A., R.P.R., J.P.B., R.B. and A.A.O.; supervision: R.P.R., J.P.B. and A.A.O.; funding acquisition: R.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is supported by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania Agricultural Development Fund, Hobart, Australia (1300 368 550). Ibrahim Ahmad also received a grant in the form of a top-up stipend from the Tim Healey Memorial Scholarship, awarded by the A. W. Howard Memorial Trust Inc., in recognition of his contributions to promoting sustainable agriculture in Australia (UTAS Ref: 00030728).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Honan, M.; Feng, X.; Tricarico, J.M.; Kebreab, E. Feed additives as a strategic approach to reduce enteric methane production in cattle: Modes of action, effectiveness and safety. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2021, 62, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Hristov, A.N.; Price, W.J.; McClelland, S.C.; Pelaez, A.M.; Cueva, S.F.; Oh, J.; Dijkstra, J.; Bannink, A.; Bayat, A.R.; et al. Full adoption of the most effective strategies to mitigate methane emissions by ruminants can help meet the 1.5 °C target by 2030 but not 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2111294119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Abdalla, A.L.; Alvarez, C.; Arndt, C.; Becquet, P.; Benchaar, C.; Berndt, A.; Mauricio, R.M.; McAllister, T.A.; et al. Invited review: Current enteric methane mitigation options. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9297–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prado, A.; Vibart, R.E.; Bilotto, F.M.; Faverin, C.; Garcia, F.; Henrique, F.L.; Leite, F.F.G.D.; Mazzetto, A.M.; Ridoutt, B.G.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; et al. Feed additives for methane mitigation: Assessment of feed additives as a strategy to mitigate enteric methane from ruminants—Accounting; How to quantify the mitigating potential of using antimethanogenic feed additives. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.; Magnusson, M.; Paul, N.A.; Kinley, R.; de Nys, R.; Tomkins, N. Identification of bioactives from the red seaweed Asparagopsis taxiformis that promote antimethanogenic activity in vitro. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, D.E.; Yarish, C.; Hristov, A.N. Enteric methane mitigation through Asparagopsis taxiformis supplementation and potential algal alternatives. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 999338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.M.; Kennedy, F.S.; Wolfe, R.S. Reaction of multihalogenated hydrocarbons with free and bound reduced vitamin B12. Biochemistry 1968, 7, 1707–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, C.R.; Kinley, R.D.; de Nys, R.; King, N.; Adams, S.L.; Packer, M.A.; Svenson, J.; Eason, C.T.; Magnusson, M. Benefits and risks of including the bromoform containing seaweed Asparagopsis in feed for the reduction of methane production from ruminants. Algal Res. 2022, 64, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsalus, R.P.; Romesser, J.A.; Wolfe, R.S. Preparation of coenzyme M analogs and their activity in the methyl coenzyme M reductase system of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 2374–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duin, E.C.; Wagner, T.; Shima, S.; Prakash, D.; Cronin, B.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Duval, S.; Rümbeli, R.; Stemmler, R.T.; Thauer, R.K.; et al. Mode of action uncovered for the specific reduction of methane emissions from ruminants by the small molecule 3-nitrooxypropanol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 6172–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanche, A.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Durmic, Z.; Garcia, F.; Santos, F.G.; Huws, S.; Jeyanathan, J.; Lund, P.; Mackie, R.I.; et al. Feed additives for methane mitigation: A guideline to uncover the mode of action of antimethanogenic feed additives for ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olijhoek, D.W.; Hellwing, A.L.F.; Brask, M.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Højberg, O.; Larsen, M.K.; Dijkstra, J.; Erlandsen, E.J.; Lund, P. Effect of dietary nitrate level on enteric methane production, hydrogen emission, rumen fermentation, and nutrient digestibility in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6191–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, X.; Cao, Y.; Cai, C.; Cui, H.; Yao, J. Nitrate decreases methane production also by increasing methane oxidation through stimulating NC10 population in ruminal culture. AMB Express 2017, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zijderveld, S.M.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Dijkstra, J.; Newbold, J.R.; Hulshof, R.B.A.; Perdok, H.B. Persistency of methane mitigation by dietary nitrate supplementation in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 4028–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Muñoz, C. Current Perspectives on Achieving Pronounced Enteric Methane Mitigation From Ruminant Production. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 2, 795200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, A.; Harper, M.T.; Oh, J.; Giallongo, F.; Young, M.E.; Ott, T.L.; Duval, S.; Hristov, A.N. Effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on rumen fermentation, lactational performance, and resumption of ovarian cyclicity in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowley, F.C.; Kinley, R.D.; Mackenzie, S.L.; Fortes, M.R.; Palmieri, C.; Simanungkalit, G.; Almeida, A.K.; Roque, B.M. Bioactive metabolites of Asparagopsis stabilized in canola oil completely suppress methane emissions in beef cattle fed a feedlot diet. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Denman, S.E.; Yang, C.; Cheung, J.; Mitsumori, M.; McSweeney, C.S. Methane Inhibition Alters the Microbial Community, Hydrogen Flow, and Fermentation Response in the Rumen of Cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amgarten, M.; Schatzmann, H.J.; Wuthrich, A. ‘Lactate type’ response of ruminal fermentation to chloral hydrate, chloroform and trichloroethanol. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 1981, 4, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M. Metabolic Hydrogen Flows in Rumen Fermentation: Principles and Possibilities of Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, R.I.; Kim, H.; Kim, N.K.; Cann, I. Invited Review—Hydrogen production and hydrogen utilization in the rumen: Key to mitigating enteric methane production. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, M.J.; Miller, T.L.; Stewart, C.S. Microbe-microbe interactions. In The Rumen Microbial Ecosystem; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T.A.; Newbold, C.J. Redirecting rumen fermentation to reduce methanogenesis. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2008, 48, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lingen, H.J.; Plugge, C.M.; Fadel, J.G.; Kebreab, E.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J. Thermodynamic Driving Force of Hydrogen on Rumen Microbial Metabolism: A Theoretical Investigation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, M.J. The Rumen Fermentation: A Model for Microbial Interactions in Anaerobic Ecosystems. In Advances in Microbial Ecology: Volume 3; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1979; pp. 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B.; Wallace, R.J. Energy-yielding and energy-consuming reactions. In The Rumen Microbial Ecosystem; Hobson, P.N., Stewart, C.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 246–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.K.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Jena, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Puniya, A.K. Rumen Microbiology: An Overview. In Rumen Microbiology: From Evolution to Revolution; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmic, Z.; Duin, E.C.; Bannink, A.; Belanche, A.; Carbone, V.; Carro, M.D.; Crüsemann, M.; Fievez, V.; Garcia, F.; Hristov, A.; et al. Feed additives for methane mitigation: Recommendations for identification and selection of bioactive compounds to develop antimethanogenic feed additives. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizsan, S.J.; Ramin, M.; Chagas, J.C.; Halmemies-Beauchet-Filleau, A.; Singh, A.; Schnürer, A.; Danielsson, R. Effects on rumen microbiome and milk quality of dairy cows fed a grass silage-based diet supplemented with the macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1112969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsson, M.; Lund, P.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Noel, S.J.; Schönherz, A.A.; Hellwing, A.L.F.; Hansen, H.H.; Nielsen, M.O. Enteric methane emission of dairy cows supplemented with iodoform in a dose–response study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maigaard, M.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Johansen, M.; Walker, N.; Ohlsson, C.; Lund, P. Effects of dietary fat, nitrate, and 3-nitrooxypropanol and their combinations on methane emission, feed intake, and milk production in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsson, M.; Maigaard, M.; Lund, P.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Nielsen, M.O. Effect of fumaric acid in combination with Asparagopsis taxiformis or nitrate on in vitro gas production, pH, and redox potential. JDS Commun. 2023, 4, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, M.H.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Larsen, M.; Højberg, O.; Ohlsson, C.; Walker, N.; Hellwing, A.L.F.; Lund, P. Gas exchange, rumen hydrogen sinks, and nutrient digestibility and metabolism in lactating dairy cows fed 3-nitrooxypropanol and cracked rapeseed. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 2047–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M. Opportunities and Hurdles to the Adoption and Enhanced Efficacy of Feed Additives towards Pronounced Mitigation of Enteric Methane Emissions from Ruminant Livestock. Methane 2022, 1, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Huang, R.; Jiménez, E.; Palma-Hidalgo, J.M.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Popova, M.; Morgavi, D.P.; Belanche, A.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. Evaluating the effect of phenolic compounds as hydrogen acceptors when ruminal methanogenesis is inhibited in vitro—Part 2. Dairy goats. Animal 2023, 17, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Popova, M.; Morgavi, D.P.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Belanche, A. Exploring the combination of Asparagopsis taxiformis and phloroglucinol to decrease rumen methanogenesis and redirect hydrogen production in goats. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2024, 316, 116060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M. A theoretical comparison between two ruminal electron sinks. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Romero, P.; Belanche, A.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Yanez-Ruiz, D.; Morgavi, D.P.; Popova, M. Evaluating the effect of phenolic compounds as hydrogen acceptors when ruminal methanogenesis is inhibited in vitro—Part 1. Dairy cows. Animal 2023, 17, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.; Maigaard, M.; Lashkari, S.; Nørskov, N.P.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Nielsen, M.O. Combination of methane-inhibitors and hydrogen-acceptors: Effects on in vitro rumen fermentation. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.T.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, I.D.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, S.S. Effects of Flavonoid-rich Plant Extracts on In vitro Ruminal Methanogenesis, Microbial Populations and Fermentation Characteristics. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.; Nielsen, M.O.; Nørskov, N.P. Dose- and substrate-dependent reduction of enteric methane and ammonia by natural additives in vitro. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1302346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, L.R.; Bryant, M.P. Eubacterium oxidoreducens sp. nov. requiring H2 or formate to degrade gallate, pyrogallol, phloroglucinol and quercetin. Arch. Microbiol. 1986, 144, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.M.; Blank, R.; Zorn, F.; Wein, S.; Metges, C.C.; Wolffram, S. Ruminal degradation of quercetin and its influence on fermentation in ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 5688–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maigaard, M.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Hellwing, A.L.F.; Larsen, M.; Andersen, F.B.; Lund, P. The acute effects of rumen pulse-dosing of hydrogen acceptors during methane inhibition with nitrate or 3-nitrooxypropanol in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 5681–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, N.; Cao, Y.; Jin, C.; Li, F.; Cai, C.; Yao, J. Effects of fumaric acid supplementation on methane production and rumen fermentation in goats fed diets varying in forage and concentrate particle size. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M. Inhibition of Rumen Methanogenesis and Ruminant Productivity: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Bannink, A.; Battelli, M.; Belanche, A.; Sanz, M.C.C.; Fernandez-Turren, G.; Garcia, F.; Jonker, A.; Kenny, D.A.; Lind, V.; et al. Feed additives for methane mitigation: Recommendations for testing enteric methane-mitigating feed additives in ruminant studies. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Yang, C. Ruminal methane production: Associated microorganisms and the potential of applying hydrogen-utilizing bacteria for mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M.; Kohn, R.A.; Wallace, R.J.; Newbold, C.J. A meta-analysis of fumarate effects on methane production in ruminal batch cultures. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 2556–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanuma, N.; Iwamoto, M.; Hino, T. Effect of the Addition of Fumarate on Methane Production by Ruminal Microorganisms In Vitro. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, C.J.; López, S.; Nelson, N.; Ouda, J.O.; Wallace, R.J.; Moss, A.R. Propionate precursors and other metabolic intermediates as possible alternative electron acceptors to methanogenesis in ruminal fermentation in vitro. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 94, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Russell, J.B. Fermentation of peptides and amino acids by a monensin-sensitive ruminal Peptostreptococcus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 2742–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, L.R.; Crawford, R.L.; Hemling, M.E.; Bryant, M.P. Metabolism of gallate and phloroglucinol in Eubacterium oxidoreducens via 3-hydroxy-5-oxohexanoate. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-G.; Jones, G.A. Isolation and identification of rumen bacteria capable of anaerobic phloroglucinol degradation. Can. J. Microbiol. 1975, 21, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-G.; Gates, D.M.; Ingledew, W.M.; Jones, G.A. Products of anaerobic phloroglucinol degradation by Coprococcus sp. Pe15. Can. J. Microbiol. 1976, 22, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conradt, D.; Hermann, B.; Gerhardt, S.; Einsle, O.; Müller, M. Biocatalytic Properties and Structural Analysis of Phloroglucinol Reductases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15531–15534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.R.K.; Hyder, I. Ruminant Digestion. In Textbook of Veterinary Physiology; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).