Abstract

D-Allulose is a promising low-calorie rare sugar with significant health benefits. However, its industrial production is hindered by the low catalytic efficiency (≤33% conversion) and unfavorable equilibrium of the key enzyme, D-allulose 3-epimerase (DAE). To overcome this thermodynamic bottleneck, an in vitro synthetic enzymatic cascade based on a phosphorylation–dephosphorylation strategy was constructed. This engineered system comprises four synergistically operating enzymes: D-allulose-3-epimerase (DAE), L-rhamnulose kinase (RhaB), polyphosphate kinase (PPK), and acid phosphatase (AP). Through rational design and systematic optimization, the cascade achieved an exceptional 84.5% conversion yield from 50 mM D-fructose. Importantly, the system also maintained high conversion rates of 64.4% and 61.1% at high D-fructose loadings (50–100 g L−1). This performance, together with the integration of a low-cost PolyP6–PPK ATP regeneration module, underscores the potential industrial applicability of the proposed cascade strategy.

1. Introduction

The global prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes has been exacerbated by decades of dietary overreliance on high-sugar, high-fat foods, driving demand for low-calorie sweeteners. Among these, D-allulose (C-3 epimer of D-fructose) stands out due to its near-zero caloric content (0.4 kcal/g) and approximately 70% of the sweetness to sucrose [1,2]. Its commercial appeal is further solidified by regulatory endorsements, such as the FDA’s GRAS designation and its exemption from “total sugars” labeling (2020) [3]. Beyond its role as a sweetener, D-allulose enhances food quality by participating in the Maillard reaction and inhibiting crystallization in dairy products [4,5,6]. It also offers significant physiological benefits, including the regulation of blood glucose and insulin levels, management of body weight, and modulation of gut microbiota [7,8,9,10]. Consequently, D-allulose is increasingly incorporated into a wide range of food products, from baked goods to beverages [11].

The scarcity of D-allulose in nature renders its extraction from plant sources economically unfeasible [12]. Currently, most D-allulose is synthesized through chemical or biological methods. Chemical synthesis typically involves selective aldol condensation, molybdate catalysis, alkaline isomerization, and other reactions [13,14]. However, the aforementioned chemical approaches often encounter challenges such as complex separation and purification processes, toxic reagents, and low overall yields. In contrast, enzymatic synthesis represents a compelling alternative for D-allulose production due to its high efficiency, mild reaction conditions, marked specificity, and environmentally benign profile [15,16,17,18]. For instance, Yang et al. expressed D-allulose 3-epimerase (DAE) from Agrobacterium tumefaciens in the thermotolerant bacterium Kluyveromyces marxianus, achieving a production of 190 g L−1 of D-allulose from 750 g L−1 D-fructose at 55 °C for 12 h, with a conversion rate of 25.3% [19]. However, the intrinsic reversibility of the DAE-catalyzed reaction imposes a thermodynamic equilibrium, typically limiting conversion yields to below 33–40% and creating a fundamental bottleneck for cost-effective production [3,19]. Recent advances have also focused on improving the catalytic properties and stability of D-allulose 3-epimerase (DAEase) through enzyme engineering and in vivo screening strategies. For example, biosensor-assisted, growth-coupled evolution platforms have enabled the selection of DAE variants with significantly enhanced activity and thermostability, providing enzyme-level solutions to the inherent performance bottlenecks of this key catalyst [20]. Such progress complements the present study, which addresses these limitations from a system-level perspective through a multi-enzyme cascade design.

To overcome this thermodynamic barrier, multi-enzyme cascade systems based on phosphorylation–dephosphorylation strategies have emerged as a promising direction [3,21]. Such systems enhance overall reaction efficiency by minimizing unstable intermediates, improving reaction specificity, and reducing by-product formation [22]. Notably, several cascade designs have demonstrated considerable potential for high-yield D-allulose production [3,21]. For example, a simplified four-enzyme cascade achieved 41.2% yield from 10.0 mM D-glucose [23], while an in vitro synthetic enzymatic biosystem based on phosphorylation–dephosphorylation routes for starch-to-D-allulose conversion, attained high yields of 88.2% and 79.2% from 10 and 50 g L−1 starch, respectively [21]. The particular effectiveness of this strategy lies in its capacity to drive reaction equilibria toward D-allulose synthesis, as the irreversible dephosphorylation step facilitates a nearly complete theoretical conversion [24]. This principle is further illustrated by a one-pot system comprising sucrose phosphorylase (SP), fructokinase (FRK), D-allulose-6-phosphate 3-epimerase (A6PE), and D-allulose-6-phosphate phosphatase (A6PP), which achieved an impressive 88.8% yield from 10 mM sucrose [25]. However, translating these advances to industrial-scale production remains challenging, as most systems are restricted to relatively low substrate loadings (<50 g L−1). This limitation stems from enzyme instability, mass transfer limitations, and substrate inhibition at higher concentrations, highlighting the need for cascades that maintain high efficiency at industrially viable substrate concentrations.

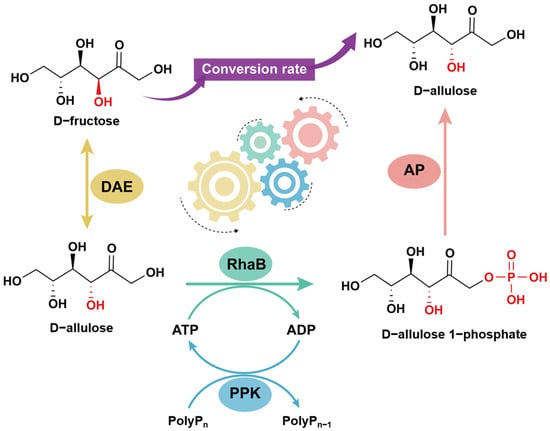

In this work, we designed a four-enzyme cascade comprising D-allulose-3-epimerase (DAE), L-rhamnulose kinase (RhaB), polyphosphate kinase (PPK), and acid phosphatase (AP) for D-allulose synthesis from D-fructose. As illustrated in Scheme 1, the four-enzyme cascade was strategically constructed to overcome the thermodynamic limitations of the DAE-catalyzed reaction by coupling irreversible dephosphorylation with ATP regeneration. We established a cost-effective ATP regeneration cycle using polyphosphate (PolyP), systematically optimized key reaction parameters for industrial applicability, and evaluated the system’s performance at high substrate loadings. This integrated approach provides an efficient and scalable biocatalytic strategy that overcomes key thermodynamic and economic constraints, offering a promising route for the industrial production of D-allulose.

Scheme 1.

Schematic of D−allulose synthesis via the multienzyme cascade reaction constructed in this study. D−fructose is first converted to D−allulose by D−allulose 3−epimerase (DAE), followed by phosphorylation to D−allulose 1−phosphate by L−rhamnose kinase (RhaB) using ATP. ATP is regenerated in situ by polyphosphate kinase (PPK) using polyphosphate. Finally, acid phosphatase (AP) dephosphorylates D−allulose 1−phosphate to release free D−allulose, driving the reaction toward product formation. The differently colored gears represent different enzymatic modules involved in the multi-enzyme cascade system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Chemicals

The genes encoding D-allulose-3-epimerase (DAE, NCBI: WP_077721022.1), L-rhamnulose kinase (RhaB, NCBI: NP_709708), and polyphosphate kinase (PPK, NCBI: Q92SA6.1) were codon-optimized, synthesized, and cloned into pET21a(+), pET28a(+), and pET28a(+) vectors, respectively, resulting in the expression plasmids pET21a-DAE, pET28a-RhaB, and pET28a-PPK. All constructs were fused with a modified N-terminal His-tag (HE tag). Escherichia coli Top10 was used for DNA manipulation, and Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was used for recombinant protein expression. Acid phosphatase (AP) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). D-Fructose (99.0%) and D-allulose (99.0%) were obtained from the Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminoethane (99.9%) and hydrochloric acid were supplied by the Damao Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). ATP was procured from Yeasen (Shanghai, China). An XBridge BEH amide column (3.5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) was purchased from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). Other chemicals were purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China). Without further purification, all chemicals and reagents were obtained from commercial vendors.

2.2. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

Recombinant Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strains were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic (100 μg mL−1 ampicillin or kanamycin) at 37 °C until reaching an optical density (OD600 = 0.6–0.8). Protein overexpression was induced by adding 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubating for an additional 16 h at 16 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 4 °C and washed three times with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). The cells were then resuspended in the same buffer and lysed by ultrasonication. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000× g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the target enzymes in the supernatants were obtained for further purification. His-tagged proteins were purified on a His Trap™ FF column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) in an AKTA pure system at a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1. Wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 20–60 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) was used to elute unbound proteins, and the target enzyme was eluted with elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, pH 7.5). The eluted protein was further dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) to remove imidazole and concentrated by Amicon® Ultra filter (10 kDa) (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The protein concentration was measured using the Bradford Assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Purified proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to determine their molecular mass and purity.

2.3. Enzyme Activity Assays

The conversion efficiency of the multienzyme reaction was evaluated based on the concentration of D-allulose produced. The multienzyme reaction mixture was prepared in a Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM D-fructose, 5 mM Mg2+, 10 mM polyphosphate (PolyP6), 10 mM ATP, and 0.1 mg·mL−1 each of DAE, RhaB, and polyphosphate kinase (PPK). After incubation at 45 °C for 2 h, the reaction was stopped by boiling. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation for 10 min. Subsequently, the pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 5.0 with HCl. Acid phosphatase (2 µL) was added, and the reaction was incubated at 30 °C for 12 h. The reaction was terminated by heating at 100 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation, and D-allulose was quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a refractive index detector (RID-20A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and an XBridge BEH amide column. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and water (80:20, v/v) with 0.1% (v/v) ammonia, operated at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from triplicate measurements.

2.4. Optimization of Multienzyme Cascade Reaction Conditions

The following parameters of the multienzyme system reaction were optimized: temperature, pH, metal ion concentration, as well as ATP and PolyP6 concentrations. Based on the initial conditions, the influence of reaction temperature (30–80 °C) and pH (6.0–10.0) on D-allulose biosynthesis was evaluated. To investigate the effects of metal ions on the multienzyme reaction, different metal ions (Ca2+, Ni2+, Fe2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, and Mn2+) and EDTA were individually added to the reaction system at a final concentration of 5 mM. Based on the optimum reaction temperature, pH, and metal ion conditions, the effects of ATP and PolyP6 concentrations on the biosynthesis of D-allulose was also investigated. To further improve D-allulose yield, various concentrations of ATP (0–50 mM) and PolyP6 (0–50 mM) were tested to determine the optimal conditions.

2.5. Biosynthesis of D-Allulose

The biosynthesis of D-allulose from D-fructose was performed using an optimum multienzyme cascade system with 50 mM D-fructose. The reaction was conducted at 50 °C for 2 h and then terminated by heating at 100 °C. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation. Subsequently, the pH was adjusted to 5.0 using concentrated HCl. Acid phosphatase (2 µL) was added, and the reaction was conducted at 30 °C for 12 h. The reaction was terminated by heating at 100 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation, the D-allulose concentration in the supernatant was determined using HPLC. For the three-enzyme reaction containing only DAE, RhaB, and AP, PolyP6 and PPK were omitted, and the remaining reaction components and analytical conditions remained the same as described above.

2.6. Conversion of High Concentration of D-Fructose into D-Allulose

High concentrations of D-fructose (50–500 g L−1) wereused for D-allulose production. The reaction system was carried out in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), containing 5 mM ATP, 10 mM PolyP6, 5 mM Mg2+, and 1.0 mg mL−1 each of DAE, RhaB, and PPK. The reaction was conducted at 50 °C for 24 h and then terminated by heating at 100 °C. All subsequent steps and analytical conditions were the same as described in Section 2.5.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Multienzyme Cascade Components

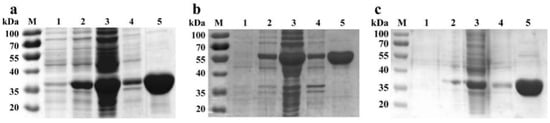

The successful implementation of a multi-enzyme cascade hinges on the efficient production of high-quality enzyme components. Accordingly, we procured the key catalysts for our system: DAE from Novibacillus thermophilus, RhaB from Shigella flexneri 2a str. 301, and PPK from Sinorhizobium meliloti. Each enzyme was successfully overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) or BL28(DE3) as N-terminal His-tagged fusions and purified to near-homogeneity via affinity chromatography (Figure 1). SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed both the high purity of the preparations and that the observed molecular weights for DAE (~35 kDa), RhaB (~55 kDa), and PPK (~35 kDa) were in full agreement with their theoretical values (Figure 1a–c, lane 5). The high purity of these enzyme preparations provided a critical foundation for the subsequent construction and precise optimization of the multienzyme cascade.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of (a) DAE, (b) RhaB and, (c) PPK. Lane M: protein marker; lane 1: cell lysate without induction; lane 2: cell lysate after induction; lane 3: the soluble supernatant of induced cell lysate; lane 4: the insoluble precipitation of cell lysate with induction; lane 5: purified protein.

3.2. Systematic Optimization of Cascade Reaction Conditions

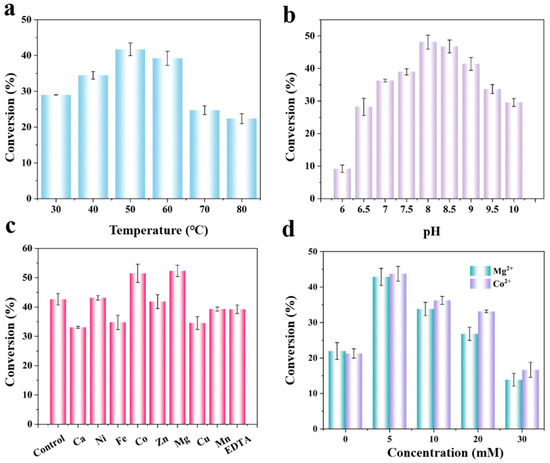

Having established a purified enzyme toolkit, we proceeded to systematically optimize the reaction conditions to maximize the synergy of the four-enzyme cascade. Temperature affects enzyme activity, stability, and mass transfer within the reaction system, thereby influencing overall product formation [26]. As shown in Figure 2a, the conversion of D-allulose increased with rising temperatures from 30 to 50 °C, indicating 50 °C as the optimum for the multienzyme cascade, beyond which a decline was observed. This decline was likely due to the incipient thermal denaturation of one or more enzyme components. Enzyme activity is sensitive to pH variations, with different enzymes exhibiting distinct optimal pH values [27]. Therefore, we sought a pH condition that balanced the activities of all four enzymes. Three different buffer systems were selected for experiments: phosphate-buffered solution (pH 6.0–7.0), Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5–8.5), and glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 9.0–10.0). Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) exhibited the highest catalytic efficiency under baseline conditions (5 mM ATP, 10 mM PolyP, no metal ions), affording a 49.0% conversion (Figure 2b). This pH value was therefore selected as the compromise condition for subsequent optimization, which ultimately increased the conversion to 84.5%. Extreme acidity or alkalinity can alter enzyme conformation, reducing efficiency and potentially inactivating enzymes, which in turn affects the conversion rate of D-fructose [28].

Figure 2.

Optimization of multienzyme cascade reaction conditions for D-allulose production. Effect of (a) temperature, (b) pH, (c) metal ions, and (d) the concentrations of Mg2+ and Co2+. Reactions were carried out using 50 mM D-fructose and 0.1 mg·mL−1 each of DAE, RhaB, and PPK in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), supplemented with 5 mM ATP, 10 mM PolyP6, and 5 mM Mg2+. All reactions were incubated at 50 °C for 2 h, and D-allulose was quantified by HPLC.

Certain metal ions play essential roles in enzyme catalysis, functioning as electron donors/acceptors, Lewis acids, or structural regulators [29]. As shown in Figure 2c, Co2+ and Mg2+ significantly enhance the reaction, in contrast, Ca2+, Zn2+, and Cu2+ exhibit inhibitory effects on the multi-enzyme cascade. Co2+ is a recognized activator in DAE catalytic reactions, while Mg2+ serves as a crucial cofactor in kinase catalytic processes [30,31]. Further optimization revealed that both 5 mM Co2+ and Mg2+ supported higher conversion rates (Figure 2d). However, although Co2+ demonstrated stronger catalytic activity, Mg2+ was selected for all further studies due to its lower toxicity, and broader industrial applicability [32,33], and it is essential for ATP regeneration catalyzed by polyphosphate kinase, which drives the phosphorylation steps in the system [34]. This selection aligns with the goal of developing a practical and scalable biocatalytic process.

3.3. Balancing the ATP and Polyphosphate System

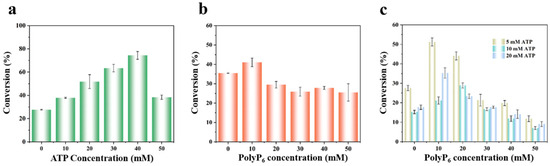

In multienzyme cascade reactions, ATP serves as the initial phosphate donor for substrate phosphorylation. This ATP is then continuously regenerated by polyphosphate kinase (PPK), a feature that is central to the economic viability of the phosphorylation–dephosphorylation strategy. As shown in Figure 3a, the conversion efficiency exhibited a strong dependence on ATP concentration, rising to a maximum of 73% at 40 mM before sharply declining to 36% at 50 mM. This decline indicates that high ATP concentrations may inhibit PPK activity or impair RhaB and PPK through ADP and phosphate accumulation [35,36]. Furthermore, the observed inhibition aligns with established reports that excessive ATP can suppress the overall efficiency of multi-enzyme cascades [31].

Figure 3.

Optimization of ATP and PolyP6 concentrations for D-allulose production. Effect of (a) ATP concentration, (b) PolyP6 concentration, and (c) combined ATP and PolyP6 concentrations on D-allulose production. Reactions were performed with 50 mM D-fructose and 0.1 mg·mL−1 each of DAE, RhaB, and PPK in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) at 50 °C for 2 h, supplemented with the indicated ATP and PolyP6 concentrations. D-allulose concentrations were determined by HPLC.

The concentration of the phosphate donor, polyphosphate (PolyP), was equally critical. PolyP molecules vary in chain length and are typically classified as short chains (3–5 Pi) or long chains (>10 Pi) [37]. In this study, sodium hexametaphosphate (PolyP6), a short-chain PolyP, was used. As illustrated in Figure 3b, 10 mM PolyP6 resulted in the highest conversion rate. At higher concentrations, the conversion decreased, suggesting that excess PolyP6 might impede the reaction by affecting PPK efficiency [38,39]. The underlying cause, as noted in prior studies, could be the highly negative charge of PolyP6, which may lead to non-specific enzyme binding or chelation of essential metal ions like Mg2+ [40].

Although a decline in conversion was observed at elevated ATP and PolyP6 levels, the underlying inhibitory mechanisms are not yet fully understood. Previous studies suggest that excessive ATP or PolyP may cause enzyme inhibition, cofactor chelation, or undesired side reactions. For example, excess PolyP6 can chelate essential metal ions such as Mg2+, diminishing their availability for enzymatic activity [40]. Additionally, elevated ATP concentrations are known to allosterically inhibit kinase activity as part of cellular feedback regulation, as observed in systems including AMPK and PFK-1 [41,42,43]. Further studies are needed to clarify whether analogous effects occur in this specific multienzyme cascade.

Guided by the dual objectives of high yield and low cost, we rationally explored a more economical operating region. Strikingly, at a substantially reduced ATP concentration of 5 mM, the system achieved a 51% conversion when coupled with 10 mM PolyP6 (Figure 3c). This demonstrates that the cascade retains high functional efficiency under ATP-limiting conditions, provided that the PolyP-driven regeneration cycle is optimally tuned. This strategy is pivotal, as it establishes a feasible approach to drastically reduce the economic burden of stoichiometric ATP addition, thereby significantly enhancing the industrial prospects of the biocatalytic process.

To further demonstrate the cost advantage of the PolyP-driven ATP regeneration strategy, we compared it with conventional systems based on literature-reported parameters. The phosphoenolpyruvate–pyruvate kinase (PEP–PK) system generates 1 mol ATP per mol PEP but relies on a high-energy phosphate donor that is typically priced in the hundreds of USD per gram, rendering preparative- or industrial-scale application economically prohibitive [44]. The acetate kinase–acetyl phosphate (AcK–AcP) system also requires stoichiometric acetyl phosphate, which is substantially more expensive than inorganic phosphate donors and further limited by the reversible nature of the AcK-catalyzed reaction [44]. In contrast, the PPK system employs inorganic polyphosphate (PolyP6), a low-cost and widely available phosphate donor reported to be suitable for large-scale enzymatic applications. PolyP enables multi-cycle ATP regeneration, allowing a single equivalent of ATP to be recycled repeatedly during the reaction, which has supported gram-scale biocatalysis in published systems [45]. Collectively, these quantitative comparisons emphasize the intrinsic economic advantage of the PolyP-driven phosphorylation–dephosphorylation cascade.

3.4. D-Allulose Synthesis via the Optimized Multienzyme Cascade

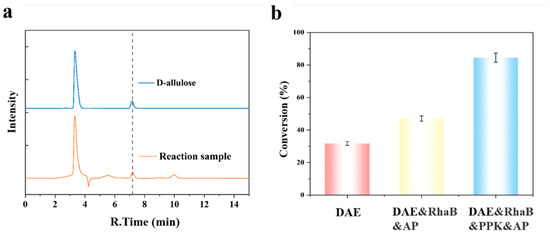

With the optimal reaction conditions established (5 mM ATP, 10 mM PolyP6, 5 mM Mg2+ in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), the performance of the fully constituted cascade was evaluated using 50 mM D-fructose as substrate. To deconvolute the contribution of each module, three distinct enzyme configurations were compared (Figure 4b): a single-enzyme system (DAE), a three-enzyme system (DAE & RhaB & AP), and a four-enzyme system incorporating ATP regeneration (DAE & RhaB & PPK & AP). As anticipated, the single-enzyme reached a conversion of 31.7%, a ceiling imposed by the inherent thermodynamic equilibrium of the epimerization reaction. Introducing the phosphorylation module (DAE, RhaB, and AP) increased the conversion to 47.0%, demonstrating the initial pull provided by ATP-driven phosphorylation. The complete four-enzyme system (DAE, RhaB, PPK, and AP), featuring the integrated ATP regeneration cycle, achieved a remarkable final conversion of 84.5%. This result unambiguously validates the critical role of the sustainable, PolyP-driven ATP regeneration in maximizing the driving force of the phosphorylation–dephosphorylation strategy, pushing the yield far beyond the thermodynamic limit of the single-step reaction.

Figure 4.

Multienzyme cascade synthesis of D-allulose. (a) HPLC analysis of the multienzyme cascade reaction, and (b) effects of different enzyme combinations on D-allulose formation. All reactions were conducted with 50 mM D-fructose, 0.1 mg·mL−1 each of the enzymes used in the respective combinations, 5 mM ATP, 10 mM PolyP6, and 5 mM Mg2+ in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) at 50 °C for 2 h. HPLC conditions follow those described in Section 2.3. The dashed line indicates the retention time correspondence between the D-allulose standard and the peak observed in the reaction sample.

3.5. Cascade Performance at High Substrate Loadings

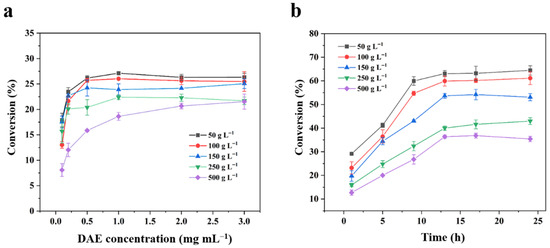

The industrial potential of a biocatalytic process is critically evaluated based on its performance under high substrate loadings, which directly impact the economic feasibility of downstream processing and overall titer. To assess this, the optimized cascade was rigorously tested against the conventional single-enzyme DAE system across a demanding concentration range of D-fructose (50 to 500 g L−1). As shown in Figure 5a, the DAE system achieved a maximum equilibrium conversion of only 26.3% at 50 g L−1 D-fructose within 1 h, which further decreased to 21.5% at 500 g L−1. In contrast, the multi-enzyme cascade demonstrated superior robustness, achieving high conversion yields of 64.4% at 50 g L−1 and 61.1% at 100 g L−1 (Figure 5b), albeit requiring a longer reaction time (~13 h) to reach equilibrium. Although a gradual decline in conversion was observed beyond 150 g L−1, a common challenge in concentrated systems due to increased viscosity and mass transfer limitations [46,47], the cascade consistently and substantially outperformed the single-enzyme system across the entire concentration range. This performance definitively establishes that the integrated system successfully overcomes the fundamental thermodynamic bottleneck, enabling high-yield production at industrially relevant substrate loading.

Figure 5.

Comparison of different enzymatic reaction systems under high concentrations of D-fructose. Effect of (a) DAE concentration on the conversion efficiency of the single-enzyme system and (b) reaction time on the conversion efficiency of the multienzyme cascade system. All reactions were carried out at 50 °C and pH 8.0 with substrate concentrations ranging from 50 to 500 g L−1.

A comparative analysis with previously reported D-allulose biosynthesis systems further contextualizes the advantages of this cascade (Table 1). While traditional pathways like A6PE/A6PP often involve complex enzymatic steps and depend on expensive cofactors [23,48], and sucrose-derived strategies require additional auxiliary enzymes [49], the system developed here distinguishes itself through its strategic simplicity and efficiency. Our cascade employs a minimal set of only four enzymes and utilizes D-fructose—a simple and readily available substrate. It achieved a notably high conversion rate of 84.5% from 50 mM D-fructose, driven by an exceptionally low-cost ATP regeneration system (requiring only 5 mM ATP and 10 mM PolyP6). This combination of minimal enzyme requirement, straightforward substrate usage, and cost-effective cofactor recycling underscores the superior economic and operational feasibility of our platform. The retained high conversion at industrially relevant concentrations (50–100 g L−1), coupled with the system’s simplicity, positions this cascade as a highly competitive and promising route for scalable D-allulose production. Future work will focus on enzyme engineering and process intensification to further enhance substrate tolerance and reduce reaction times, thereby fully unlocking the industrial potential of this system.

Table 1.

Comparative evaluation of D-allulose biosynthesis systems.

Beyond conversion yield and pathway configuration, practical evaluation of D-allulose production systems also depends on factors such as cofactor cost, operational complexity, and performance under high substrate concentrations. These aspects are summarized in Table 1, which complements the system-level comparison in Table 1. This additional assessment highlights that most previously reported cascades rely either on costly phosphoryl donors (e.g., PEP or acetyl phosphate) or require multi-step enzymatic modules, whereas the PolyP6-PPK-based strategy used in this work offers lower cofactor cost, reduced process complexity, and stable performance at substrate concentrations up to 100 g L−1. These distinctions further underscore the practical and economic advantages of the present cascade relative to earlier designs.

3.6. Enzyme Stability and Reusability Considerations

Although the free-enzyme system in this study exhibits high catalytic efficiency, its industrial applicability largely depends on catalyst stability and reusability. While the immobilization and thermal stability of certain key enzymes, such as NtDAE, is well documented, the overall stability of the cascade and its potential for repeated use have not yet been evaluated [51,52]. Previous studies indicate that D-allulose epimerases can maintain activity during prolonged operation or multiple reuse cycles when applied with immobilization or carrier-assisted strategies [53]. These observations suggest that, under suitable process configurations, catalyst stability and reusability may be achievable for the present cascade. Future investigations, including long-term operation and immobilization-based approaches, will be essential to fully assess and enhance the industrial potential of this system.

4. Conclusions

Taken together, our results demonstrate the establishment of a four-enzyme cascade for the high-yield synthesis of D-allulose from D-fructose. The system centers on an integrated phosphorylation–dephosphorylation strategy featuring a cost-effective, polyphosphate-driven ATP regeneration cycle, which effectively overcomes the thermodynamic equilibrium constraint of conventional DAE catalysis. This approach achieved a remarkable 84.5% conversion rate, representing a 2.7-fold improvement over the single-enzyme method. Furthermore, the cascade maintained robust performance at industrially relevant substrate concentrations, reaching 64.4% and 61.1% conversion at 50 and 100 g L−1, respectively. By combining high efficiency, operational simplicity, and economic viability, this work provides a scalable and promising biocatalytic platform for the industrial production of D-allulose and other high-value rare sugars.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and H.T.; methodology, H.T.; validation, D.F.; formal analysis, Y.L., H.T. and D.F.; investigation, H.T.; resources, S.H.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and H.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., H.T. and S.H.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, S.H.; project administration, Q.W.; funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2023YFA0913600, and the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province, grant number 2022B0202120001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data supporting this study are included in the article. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; Gao, X.D.; Li, Z. Recent Advances Regarding the Physiological Functions and Biosynthesis of D-Allulose. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 881037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Ke, M.; Ye, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Characterization of a Recombinant D-Allulose 3-Epimerase from Thermoclostridium caenicola with Potential Application in D-Allulose Production. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Luan, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, F.; Feng, W.; Xu, W.; Song, P. Advances in the Biosynthesis of D-Allulose. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Q. Advances in the Bioproduction of D-Allulose: A Comprehensive Review of Current Status and Future Prospects. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, Y.; Yamada, T.; Iida, T.; Ozaki, N.; Gou, Y.; Oshida, Y.; Koike, T. Investigation of D-Allulose Effects on High-Sucrose Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance via Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamps in Rats. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Rastall, R.A.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Rodriguez-Garcia, J. Effect of D-Allulose, in Comparison to Sucrose and D-Fructose, on the Physical Properties of Cupcakes. LWT 2021, 150, 111989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Park, H.; Choi, B.R.; Ji, Y.; Kwon, E.Y.; Choi, M.S. Alteration of Microbiome Profile by D-Allulose in Amelioration of High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongkan, W.; Jinawong, K.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Jaiwongkam, T.; Kerdphoo, S.; Tokuda, M.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. D-Allulose Provides Cardioprotective Effect by Attenuating Cardiac Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Obesity-Induced Insulin-Resistant Rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Sendo, M.; Dezaki, K.; Hira, T.; Sato, T.; Nakata, M.; Goswami, C.; Aoki, R.; Arai, T.; Kumari, P.; et al. GLP-1 Release and Vagal Afferent Activation Mediate the Beneficial Metabolic and Chronotherapeutic Effects of D-Allulose. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teysseire, F.; Bordier, V.; Beglinger, C.; Wölnerhanssen, B.K.; Meyer-Gerspach, A.C. Metabolic Effects of Selected Conventional and Alternative Sweeteners: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, K.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, X.; Ji, N.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Biochemical Characterization, Structure-Guided Mutagenesis, and Application of a Recombinant D-Allulose 3-Epimerase from Christensenellaceae bacterium for the Biocatalytic Production of D-Allulose. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1365814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Feng, Z.; Guan, L.; Lu, F.; Qin, H.M. Two-Step Biosynthesis of D-Allulose via a Multienzyme Cascade for the Bioconversion of Fruit Juices. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E.J. A New Synthesis of D-Psicose (D-Ribo-Hexulose). Carbohydr. Res. 1967, 5, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamine, S.; Iida, T.; Okuma, K.; Izumori, K. Manufacturing Method of Rare Sugar Syrup through Alkali Isomerization and Its Physiological Function. Bull. Appl. Glycosci. 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Lin, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, C.; Du, K.; Lin, H.; Lin, J. D-Psicose 3-Epimerase Secretory Overexpression, Immobilization, and D-Psicose Biotransformation, Separation and Crystallization. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Tesfay, M.A.; Ning, Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, G.; Hu, H.; Xu, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, C.; Ren, Y.; et al. Green Biotechnological Synthesis of Rare Sugars/Alcohols: D-Allulose, Allitol, D-Tagatose, L-Xylulose, L-Ribose. Food Res. Int. 2025, 206, 116058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, F.; Qin, H.M. Engineering a Thermostable Version of D-Allulose 3-Epimerase from Rhodopirellula baltica via Site-Directed Mutagenesis Based on B-Factors Analysis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2020, 132, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.D.; Xu, B.P.; Yu, T.L.; Fei, Y.X.; Cai, X.; Huang, L.G.; Jin, L.Q.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zheng, Y.G. Identification of Hyperthermophilic D-Allulose 3-Epimerase from Thermotoga sp. and Its Application as a High-Performance Biocatalyst for D-Allulose Synthesis. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Mu, D.; Jiang, S.; Luo, S.; Wu, Y.; Du, M. Cell Regeneration and Cyclic Catalysis of Engineered Kluyveromyces marxianus of a D-Psicose-3-Epimerase Gene from Agrobacterium tumefaciens for D-Allulose Production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Gao, X.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Lu, F.; Qin, H.-M. Growth-Coupled Evolutionary Pressure Improving Epimerases for D-Allulose Biosynthesis Using a Biosensor-Assisted In Vivo Selection Platform. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2306478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Han, P.; You, C. Thermodynamics-Driven Production of Value-Added D-Allulose from Inexpensive Starch by an In Vitro Enzymatic Synthetic Biosystem. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 5088–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, E.; Brucher, B.; Schrittwieser, J.H. Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Reactions: Overview and Perspectives. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2239–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, Z.; Du, X.; Cheng, Q.; Ji, F.; Nie, Z.; Zhan, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, A.; Delidovich, I.; et al. D-Allulose Production via a Simplified In Vitro Multienzyme Cascade Strategy: Biosynthesis and Crystallization. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Shi, T.; Li, Y.; Han, P.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.-H.P. An In Vitro Synthetic Biology Platform for the Industrial Biomanufacturing of Myo-Inositol from Starch. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Tu, W.; Liu, S.; Ji, Y.; Schwaneberg, U.; Guo, Y.; Ni, Y. Novel Multienzyme Cascade for Efficient Synthesis of D-Allulose from Inexpensive Sucrose. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.K. Enzymes: Principles and Biotechnological Applications. Essays Biochem. 2015, 59, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.F.; Ju, L.K. On Optimization of Enzymatic Processes: Temperature Effects on Activity and Long-Term Deactivation Kinetics. Process Biochem. 2023, 130, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Lin, J.; Gao, L.; Lin, H.; Lin, J. Enzymatic Fructose Removal from D-Psicose Bioproduction Model Solution and the System Modeling and Simulation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, J.D. The Role of Metals in Enzyme Activity. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1977, 7, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Li, C.; Bai, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z. D-Allulose 3-Epimerase for Low-Calorie D-Allulose Synthesis: Microbial Production, Characterization, and Applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Ning, X.; Xu, W.; Li, Z. In Vitro Biosynthesis of ATP from Adenosine and Polyphosphate. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Cobalt in hard metals and cobalt sulfate, gallium arsenide, indium phosphide and vanadium pentoxide. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2006; pp. 1–294. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance for Industry: Enzyme Preparations: Recommendations for Submission of Chemical and Technological Data for Food Additive Petitions and GRAS Notices; Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition: College Park, MD, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/79379/download (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Cao, C.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Tan, T.; Liu, L. Enzymatic Production of Glutathione Coupling with an ATP Regeneration System Based on Polyphosphate Kinase. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 185, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Niu, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X. High Conversion of D-Fructose into D-Allulose by Enzymes Coupling with an ATP Regeneration System. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019, 61, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimane, M.; Sugai, Y.; Kainuma, R.; Natsume, M.; Kawaide, H. Mevalonate-Dependent Enzymatic Synthesis of Amorpha-4,11-diene Driven by an ATP-Regeneration System Using Polyphosphate Kinase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cao, H.; Nie, K.; Li, C.; Xu, H.; Wang, F.; Tan, T.; Liu, L. Rational Design of Substrate Binding Pockets in Polyphosphate Kinase for Use in Cost-Effective ATP-Dependent Cascade Reactions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 5325–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Huang, B.; Li, Z.; Ye, Q. One-Pot Synthesis of Glutathione by a Two-Enzyme Cascade Using a Thermophilic ATP Regeneration System. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 241, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Masuda, Y.; Kirimura, K.; Kino, K. Thermostable ATP Regeneration System Using Polyphosphate Kinase from Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 for D-Amino Acid Dipeptide Synthesis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 103, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameda, A.; Shiba, T.; Kawazoe, Y.; Satoh, Y.; Ihara, Y.; Munekata, M.; Ishige, K.; Noguchi, T. A Novel ATP Regeneration System Using Polyphosphate–AMP Phosphotransferase and Polyphosphate Kinase. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2001, 91, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMPK: A Nutrient and Energy Sensor That Maintains Energy Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.R.; Farrants, G.W.; Hudson, P.J. Phosphofructokinase: Structure and Control. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1981, 293, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.H.; Stratton, M.M.; Lee, I.H.; Rosenberg, O.S.; Levitz, J.; Mandell, D.J.; Kortemme, T.; Groves, J.T.; Schulman, H.; Kuriyan, J. A Mechanism for Tunable Autoinhibition in the Structure of a Human Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II Holoenzyme. Cell 2011, 146, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Cao, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. The Cost-Efficiency Realization in E. coli-Based Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavanti, M.; Hosford, J.; Lloyd, R.C.; Brown, M.J.B. ATP Regeneration by a Single Polyphosphate Kinase Powers Multigram-Scale Aldehyde Synthesis In Vitro. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, S.; Sampedro, J.G. Measuring Solution Viscosity and Its Effect on Enzyme Activity. Biol. Proced. Online 2003, 5, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitnitsky, A.E. Solvent Viscosity Dependence for Enzymatic Reactions. Physica A 2008, 387, 5483–5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Feng, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Chen, J.; Niu, D.; Liu, J. Phosphorylation-Driven Production of D-Allulose from D-Glucose by Coupling with an ATP Regeneration System. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 15539–15547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, W.G.; Xu, J.Z. Economical One-Pot Synthesis of Isoquercetin and D-Allulose from Quercetin and Sucrose Using Whole-Cell Biocatalyst. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2024, 176, 110412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Arsalan, A.; Zhang, G.; Yun, J.; Zhang, C.; Qi, X. Coexpression of D-Allulose 3-Epimerase and L-Rhamnose Isomerase in Bacillus subtilis through a Dual Promoter Enables High-Level Biosynthesis of D-Allose from D-Fructose in One Pot. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 2056–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.X.; Sun, C.Y.; Jin, Y.T.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zheng, Y.G.; Li, M.; Wang, H.Y.; Chen, D.S. Properties of D-Allulose 3-Epimerase Mined from Novibacillus thermophilus and Its Application to Synthesis of D-Allulose. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2021, 148, 109816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Chen, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhao, F.; Han, S. Designable Immobilization of D-Allulose 3-Epimerase on Bimetallic Organic Frameworks Based on Metal Ion Compatibility for Enhanced D-Allulose Production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273 Pt 1, 133027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.Q.; Liu, W.J.; Zhang, H.Y.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, T. Designable Properties of D-Allulose 3-Epimerase Hybrid Nanoflowers and Co-Immobilization on Resins for Improved Enzyme Activity, Stability, and Reusability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).