Nutritional and Physicochemical Attributes of Sourdough Breads Fermented with a Novel Pediococcus acidilactici ORE 5 Strain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism, Raw Materials and Media

2.2. Culture Immobilization and Freeze-Drying

2.3. Sourdough Making

2.3.1. Sourdough Preparation

2.3.2. Sourdough Bread Making

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Analysis of LAB and Yeasts in Sourdough

2.4.2. pH and Acidity

2.4.3. Specific Loaf Volume

2.4.4. Organic Acids

2.4.5. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.4.6. Phytic Acid

2.4.7. Sensory Evaluation

2.4.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Viable Cell Counts in the Sourdoughs

3.2. Bread Volume and Acidity Levels

3.3. Organic Acids Content

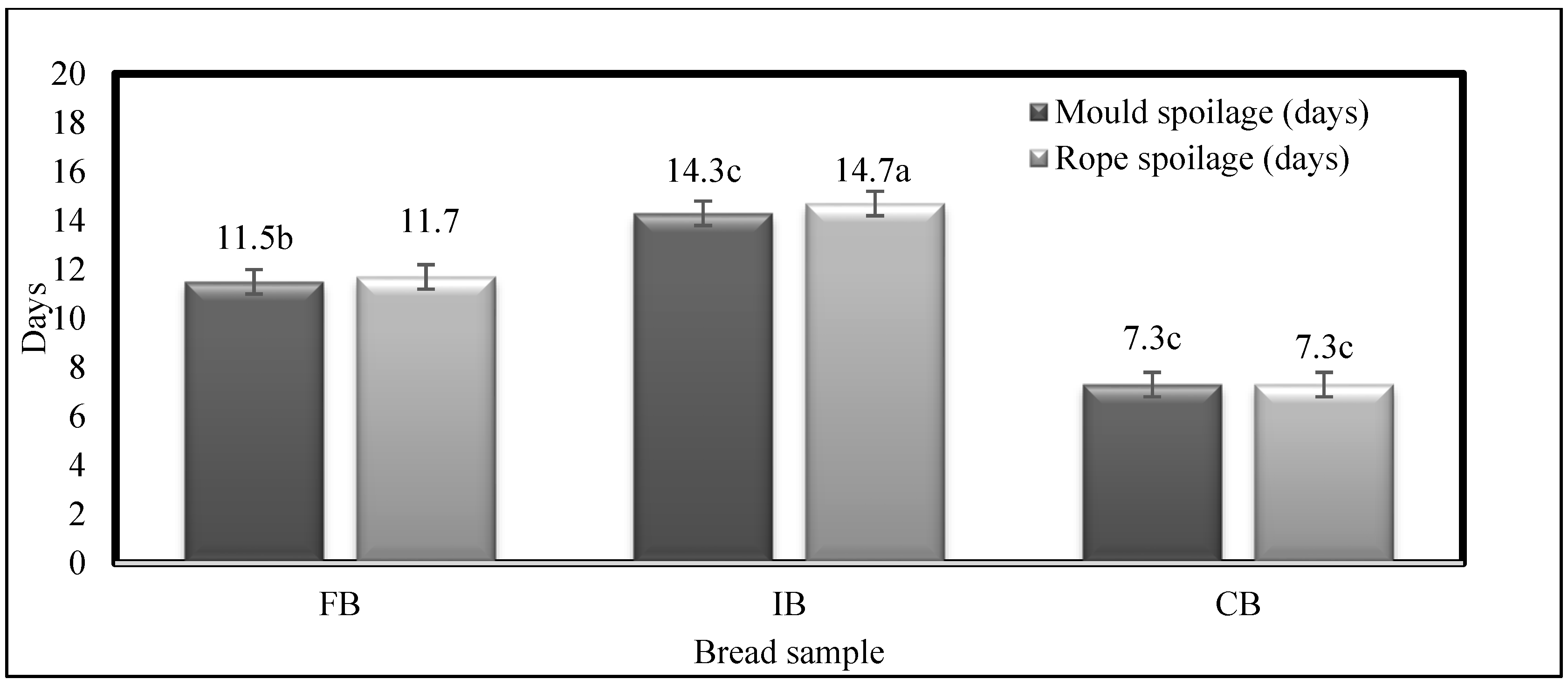

3.4. Spoilage of the Baked Breads During Storage

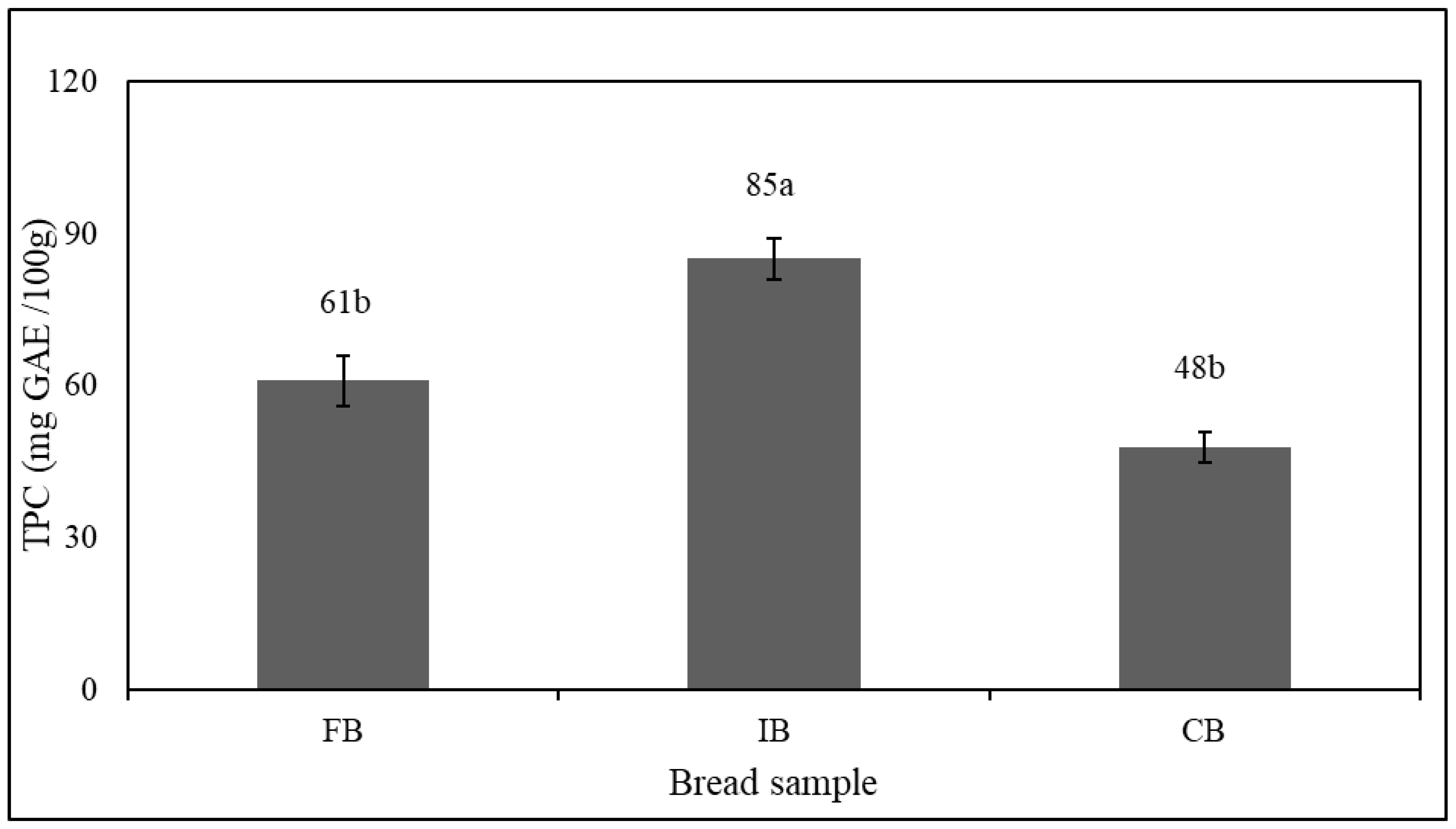

3.5. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

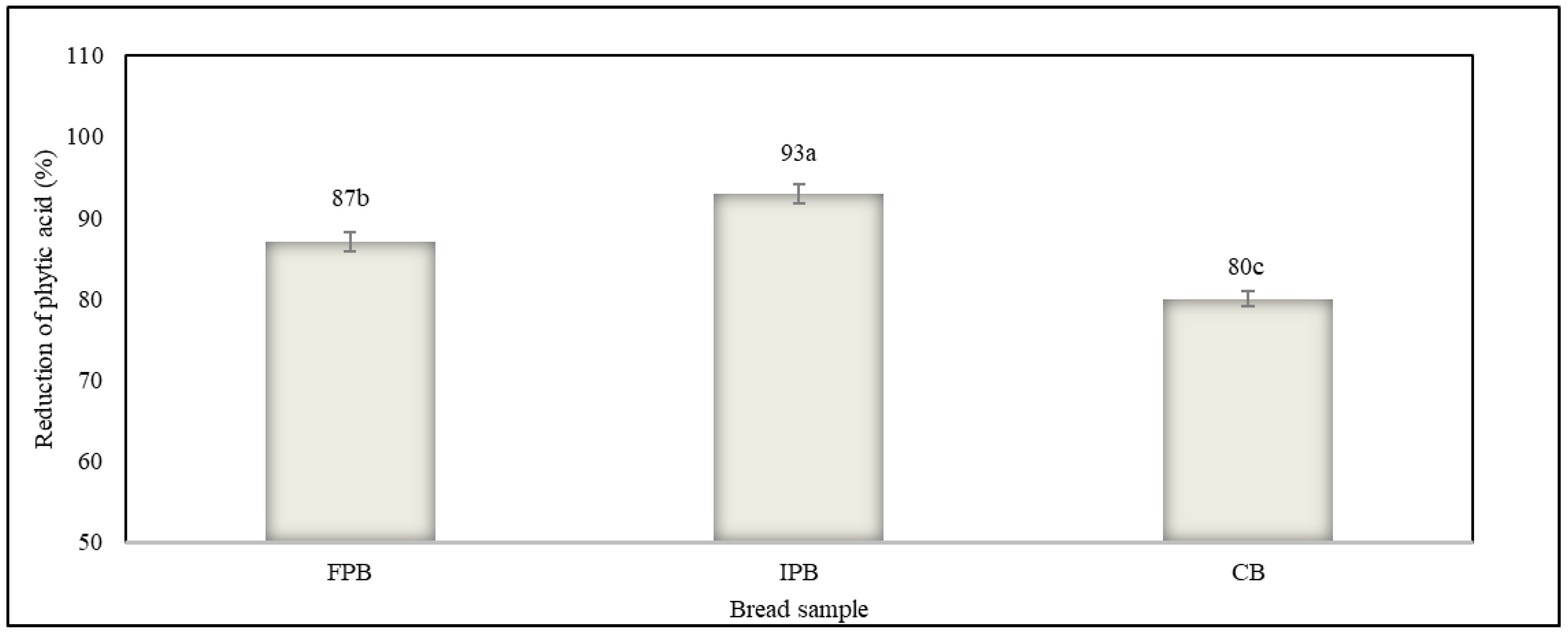

3.6. Content of Phytic Acid

3.7. Sensory Evaluation

3.8. Industrial Application and Scale-Up Potential

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sgroi, F.; Sciortino, C.; Baviera-Puig, A.; Modica, F. Analyzing Consumer Trends in Functional Foods: A Cluster Analysis Approach. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, P.; Wirkijowska, A.; Teterycz, D.; Łysakowska, P. Innovations in Wheat Bread: Using Food Industry By-Products for Better Quality and Nutrition. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S. Innovations in Sourdough Bread Making. Fermentation 2021, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Islam, S. Sourdough Bread Quality: Facts and Factors. Foods 2024, 13, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkay, Z.; Falah, F.; Cankurt, H.; Dertli, E. Exploring the Nutritional Impact of Sourdough Fermentation: Its Mechanisms and Functional Potential. Foods 2024, 13, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Haque, A.R.; Kabir, M.R.; Hasan, S.K. Fortification of Bread with Mango Peel and Pulp as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: A Comparison with Plain Bread. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luti, S.; Mazzoli, L.; Ramazzotti, M.; Galli, V.; Venturi, M.; Marino, G.; Lehmann, M.; Guerrini, S.; Granchi, L.; Paoli, P. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Sourdoughs Containing Selected Lactobacilli Strains Are Retained in Breads. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.S.; Silva, J.; Ho, P.; Teixeira, P.; Malcata, F.X.; Gibbs, P. Relevant Factors for the Preparation of Freeze-Dried Lactic Acid Bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 2004, 14, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, L.B.; Con, A.H.; Gul, O. Storage Stability and Sourdough Acidification Kinetic of Freeze-Dried Lactobacillus Curvatus N19 under Optimized Cryoprotectant Formulation. Cryobiology 2020, 96, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Dioso, C.M.; Liong, M.-T.; Nero, L.A.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Ivanova, I.V. Beneficial Features of Pediococcus: From Starter Cultures and Inhibitory Activities to Probiotic Benefits. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugaban, J.I.I.; Bucheli, J.E.V.; Park, Y.J.; Suh, D.H.; Jung, E.S.; Franco, B.D.G.d.M.; Ivanova, I.V.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Todorov, S.D. Antimicrobial Properties of Pediococcus Acidilactici and Pediococcus Pentosaceus Isolated from Silage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, D.; Raina, N.; Kumar, A.; Katoch, M.; Khajuria, Y.; Slathia, P.S.; Sharma, P. Probiotic Properties of a Phytase Producing Pediococcus Acidilactici Strain SMVDUDB2 Isolated from Traditional Fermented Cheese Product, Kalarei. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartkiene, E.; Vizbickiene, D.; Bartkevics, V.; Pugajeva, I.; Krungleviciute, V.; Zadeike, D.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Juodeikiene, G. Application of Pediococcus Acidilactici LUHS29 Immobilized in Apple Pomace Matrix for High Value Wheat-Barley Sourdough Bread. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 83, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Omedi, J.O.; Huang, C.; Chen, C.; Liang, L.; Zheng, J.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Huang, W. Effect of Black Bean Supplemented with Wheat Bran Sourdough Fermentation by Pediococcus Acidilactici or Pediococcus Pentosaceus on Baking Quality and Staling Characteristics of Wheat Composite Bread. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-E.; Hwang, C.-F.; Tzeng, Y.-M.; Hwang, W.-Z.; Mau, J.-L. Quality of white bread made from lactic acid bacteria-enriched dough: Quality of lactic acid bacteria-enhanced bread. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2012, 36, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, K.; Sagdic, O.; Durak, M.Z. Use of Phytase Active Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Sourdough in the Production of Whole Wheat Bread. LWT 2018, 91, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachi, I.; Fhoula, I.; Smida, I.; Taher, I.B.; Chouaibi, M.; Jaunbergs, J.; Bartkevics, V.; Hassouna, M. Assessment of Lactic Acid Bacteria Application for the Reduction of Acrylamide Formation in Bread. LWT 2018, 92, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizeikiene, D.; Juodeikiene, G.; Paskevicius, A.; Bartkiene, E. Antimicrobial Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria against Pathogenic and Spoilage Microorganism Isolated from Food and Their Control in Wheat Bread. Food Control 2013, 31, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatou, C.; Nikolaou, A.; Prapa, I.; Tegopoulos, K.; Plesssas, S.; Grigoriou, M.E.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Kourkoutas, Y. Effect of Immobilized Pediococcus Acidilactici ORE5 Cells on Pistachio Nuts on the Functional Regulation of the Novel Katiki Domokou-Type Cheese Microbiome. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Daoutidou, M.; Terpou, A.; Plessas, S. Evaluation of a Novel Potentially Probiotic/Pediococcus Acidilactici ORE5 in Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cornelian Cherry Juice: Assessment of Nutritional Properties, Physicochemical Characteristics, and Sensory Attributes. Fermentation 2024, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S.; Bekatorou, A.; Kanellaki, M.; Psarianos, C.; Koutinas, A. Cells Immobilized in a Starch–Gluten–Milk Matrix Usable for Food Production. Food Chem. 2005, 89, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Daoutidou, M.; Plessas, S. Impact of Functional Supplement Based on Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) Juice in Sourdough Bread Making: Evaluation of Nutritional and Quality Aspects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S.; Mantzourani, I.; Alexopoulos, A.; Alexandri, M.; Kopsahelis, N.; Adamopoulou, V.; Bekatorou, A. Nutritional Improvements of Sourdough Breads Made with Freeze-Dried Functional Adjuncts Based on Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Subsp. plantarum and Pomegranate Juice. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzourani, I.; Terpou, A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Plessas, S. Assessment of Ready-to-Use Freeze-Dried Immobilized Biocatalysts as Innovative Starter Cultures in Sourdough Bread Making. Foods 2019, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonik, S.K.; Tamanna, S.T.; Happy, T.A.; Haque, M.N.; Islam, S.; Faruque, M.O. Formulation and Evaluation of Cereal-Based Breads Fortified with Natural Prebiotics from Green Banana, Moringa Leaves Powder and Soya Powder. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpou, A.; Bekatorou, A.; Bosnea, L.; Kanellaki, M.; Ganatsios, V.; Koutinas, A.A. Wheat Bran as Prebiotic Cell Immobilisation Carrier for Industrial Functional Feta-Type Cheese Making: Chemical, Microbial and Sensory Evaluation. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 13, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Ameur, H.; Polo, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Thirty Years of Knowledge on Sourdough Fermentation: A Systematic Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Sauri, M.; Alakomi, H.-L.; Mattila-Sandholm, T. Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria to Inhibit Rope Spoilage in Wheat Sourdough Bread. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, C.; Lima, A.; Raymundo, A.; Sousa, I. Sourdough Fermentation as a Tool to Improve the Nutritional and Health-Promoting Properties of Its Derived-Products. Fermentation 2021, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Pieraccini, G.; Venturi, M.; Galli, V.; Reggio, M.; Di Gioia, D.; Furlanetto, S.; Orlandini, S.; Innocenti, M. Millet Fermented by Different Combinations of Yeasts and Lactobacilli: Effects on Phenolic Composition, Starch, Mineral Content and Prebiotic Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balli, D.; Bellumori, M.; Paoli, P.; Pieraccini, G.; Di Paola, M.; De Filippo, C.; Di Gioia, D.; Mulinacci, N.; Innocenti, M. Study on a Fermented Whole Wheat: Phenolic Content, Activity on PTP1B Enzyme and in Vitro Prebiotic Properties. Molecules 2019, 24, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc, F.; Sabuncu, M.; Yavuz, G.G.; Düven, G.; Abdo, R.M.K.; Bağci, U.; Şahan, Y.; Toğay, S.Ö.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Exploring Tarhana’s Prebiotic Potential Using Different Flours in an in Vitro Fermentation Model. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 4754–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlama, K.; Sengun, I.Y.; Nalbantsoy, A. Assessment of Probiotic, Biosafety and Technological Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Tarhana. Biologia 2024, 80, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.A.; Jin, Y.H.; Mah, J.-H. Influence of Pediococcus Pentosaceus Starter Cultures on Biogenic Amine Content and Antioxidant Activity in African Sourdough Flatbread Fermentation. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Chondrou, P.; Bontsidis, C.; Karolidou, K.; Terpou, A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Galanis, A.; Plessas, S. Assessment of the Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Kefir Grains: Evaluation of Adhesion and Antiproliferative Properties in in Vitro Experimental Systems. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffai, Y.M.; Fechtali, T. A Critical Review on the Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Sourdough Nutritional Quality: Mechanisms, Potential, and Challenges. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sourdoughs | LAB | Yeasts |

|---|---|---|

| Log cfu/g | ||

| Free P. acidilactici ORE 5 | 9.4 ± 0.1 b | 7.1 ± 0.1 a |

| Immobilized P. acidilactici ORE 5 | 10.7 ± 0.1 a | 7.0 ± 0.2 a |

| Traditional | 8.3 ± 0.2 c | 7.2 ± 0.1 a |

| Absence of P. acidilactici ORE 5 | 5.1± 0.2 c | 7.0 ± 0.1 a |

| Bread Sample | pH | TTA (mL NaOH N/10) | SLV (mL/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FB | 4.51 ± 0.05 b | 7.61 ± 0.07 b | 2.51 ± 0.05 a |

| IB | 4.30 ± 0.05 a | 9.13 ± 0.05 a | 2.50 ± 0.03 a |

| CB | 4.76 ± 0.04 c | 6.80 ± 0.03 c | 2.54 ± 0.05 a |

| Bread Sample | Organic Acids (g/kg Bread) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic | Acetic | Formic | Propionic | n-Valeric | Caproic | |

| FB | 2.59 ± 0.04 b | 0.85 ± 0.01 c | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 b |

| IB | 2.96 ± 0.08 a | 0.99 ± 0.03 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a |

| CB | 2.19 ± 0.05 c | 0.74 ± 0.03 d | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | tr | tr | tr |

| Bread Sample | Flavor | Taste | Appearance | Overall Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB | 8.9 ± 0.1 a | 8.7 ± 0.2 a | 8.9 ± 0.1 a | 8.8 ± 0.2 a |

| IB | 8.9 ± 0.2 a | 8.8 ± 0.1 a | 8.9 ± 0.2 a | 8.8 ± 0.1 a |

| CB | 8.3 ± 0.2 b | 8.2 ± 0.1 a | 8.2 ± 0.1 b | 8.3 ± 0.1 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mantzourani, I.; Alexopoulos, A.; Mitropoulou, G.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Plessas, S. Nutritional and Physicochemical Attributes of Sourdough Breads Fermented with a Novel Pediococcus acidilactici ORE 5 Strain. Fermentation 2025, 11, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120666

Mantzourani I, Alexopoulos A, Mitropoulou G, Kourkoutas Y, Plessas S. Nutritional and Physicochemical Attributes of Sourdough Breads Fermented with a Novel Pediococcus acidilactici ORE 5 Strain. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120666

Chicago/Turabian StyleMantzourani, Ioanna, Athanasios Alexopoulos, Gregoria Mitropoulou, Yiannis Kourkoutas, and Stavros Plessas. 2025. "Nutritional and Physicochemical Attributes of Sourdough Breads Fermented with a Novel Pediococcus acidilactici ORE 5 Strain" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120666

APA StyleMantzourani, I., Alexopoulos, A., Mitropoulou, G., Kourkoutas, Y., & Plessas, S. (2025). Nutritional and Physicochemical Attributes of Sourdough Breads Fermented with a Novel Pediococcus acidilactici ORE 5 Strain. Fermentation, 11(12), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120666