Isolation and Partial Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Starter Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Natural Whey Starter Culture Sampling

2.2. Bacteria Enumeration and Isolation from NWS Culture

2.3. Enrichment Cultures

2.4. Genotypic Identification by Partial 16S rDNA Gene Sequence Analysis

2.5. Species- and Subspecies-Specific PCR

2.6. Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RAPD-PCR) Analysis

2.7. High-Throughput Sequencing

2.8. Determination of the Safety Parameters

2.8.1. Antibiotic Susceptibility

2.8.2. Hemolytic Activity

2.9. Homo- and Heterofermentative Properties

2.9.1. Small-Scale Experiments for Biomass and Acid Production

2.9.2. Analytical Methods: UHPLC Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Enumeration and Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Starter Culture

3.2. Molecular Identification of Species Isolated from Natural Whey Starter Cultures

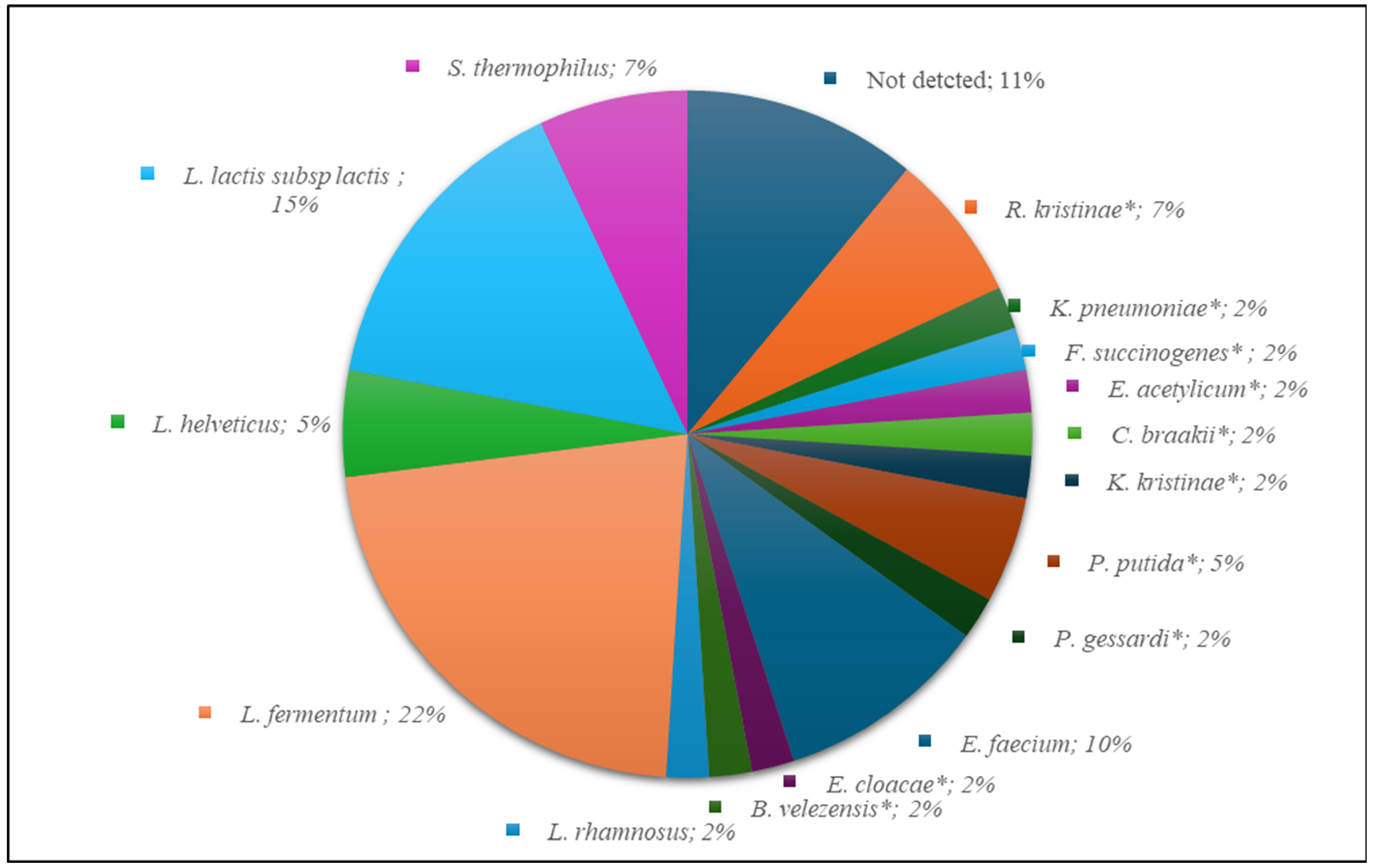

3.2.1. Sequencing of V1–V3 rDNA Region

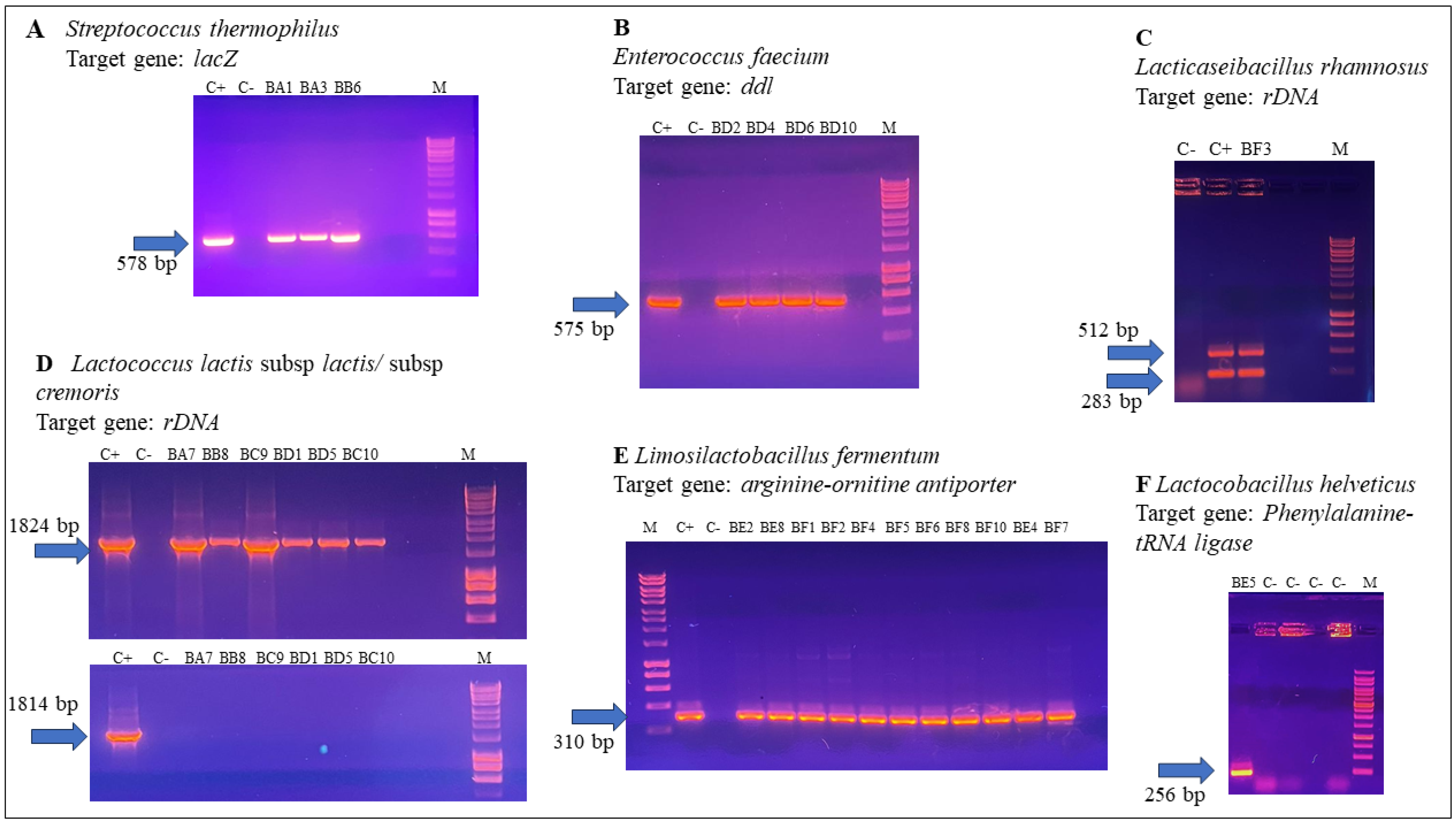

3.2.2. Species- and Subspecies-Specific PCR

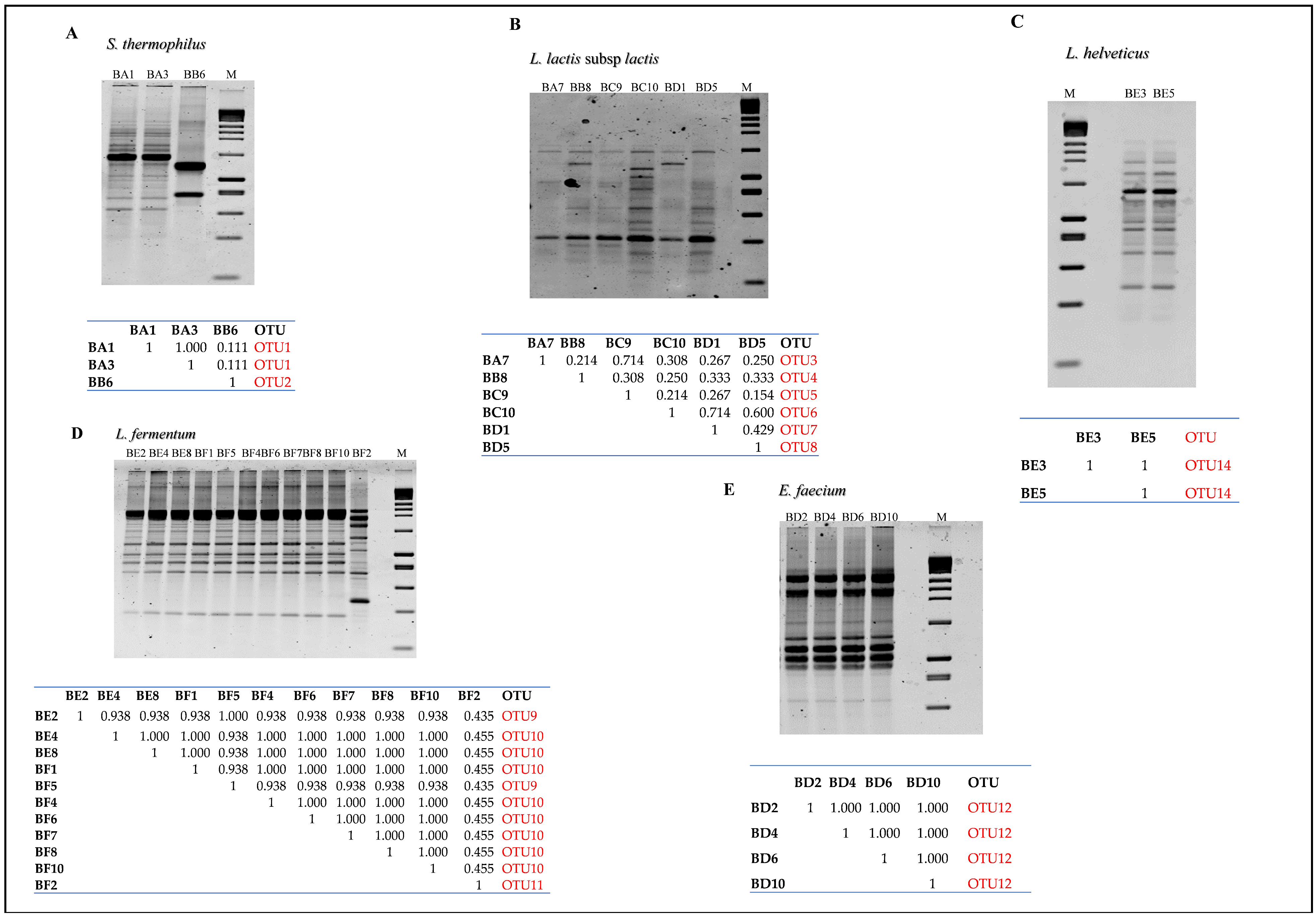

3.2.3. Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RAPD-PCR) Analysis

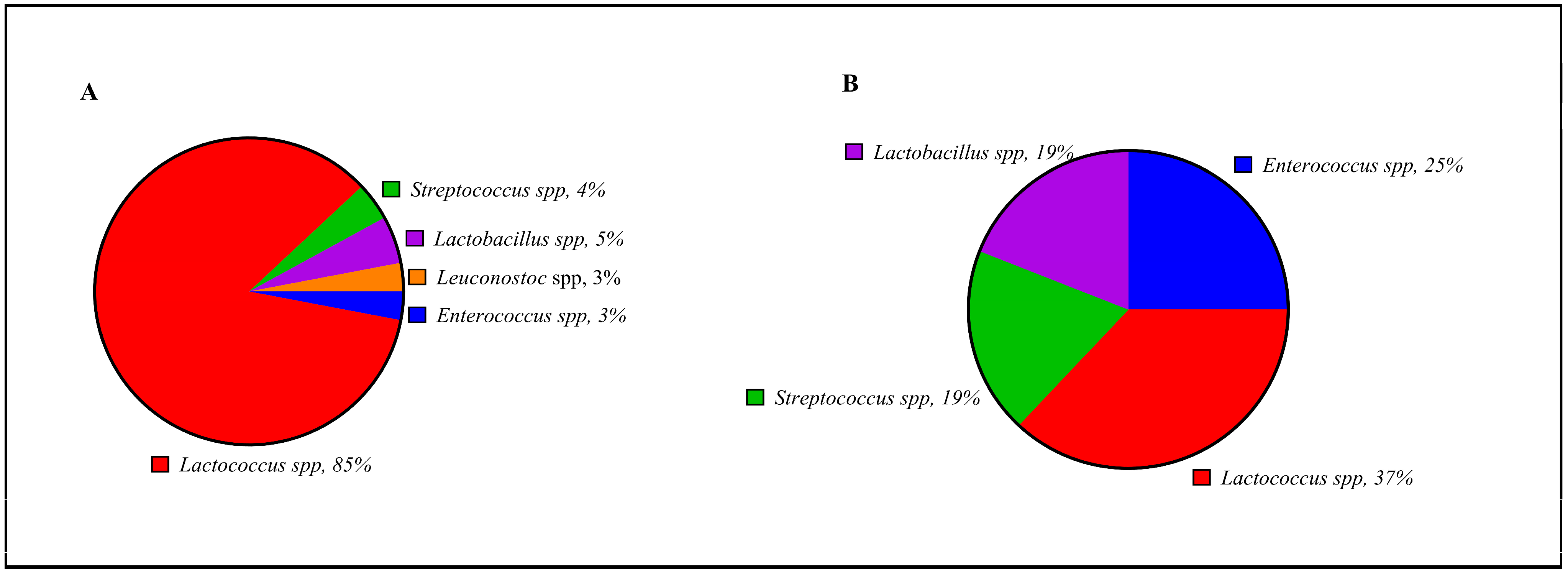

3.2.4. 16S rDNA Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis (NGS)

3.3. Safety Parameters (Antibiotic Susceptibility and Hemolytic Activity)

3.4. Physiological Studies in Small-Scale Fermentation Experiments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Çetin, B.; Usal, M.; Aloğlu, H.; Busch, A.; Dertli, E.; Abdulmawjood, A. Characterization and technological functions of different lactic acid bacteria from traditionally produced Kırklareli white brined cheese during the ripening period. Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bai, M.; Kwok, L.Y.; Zhong, Z.; Sun, Z. The intricate symbiotic relationship between lactic acid bacterial starters in the milk fermentation ecosystem. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 65, 728–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzić-Vidojević, A.; Tonković, K.; Leboš Pavunc, A.; Beganović, J.; Strahinić, I.; Kojić, M.; Veljović, K.; Golić, N.; Kos, B.; Čadež, N.; et al. Evaluation of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria as starter cultures for production of white pickled and fresh soft cheeses. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.S.; da Cruz Pedrozo Miguel, M.G.; Martinez, S.J.; Bressani, A.P.P.; Evangelista, S.R.; Silva E Batista, C.F.; Schwan, R.F. The use of mesophilic and lactic acid bacteria strains as starter cultures for improvement of coffee beans wet fermentation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, R.; Zhang, F.; Song, Y.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, A.; Liu, Y.; Peng, H.; Hui, Y.; Ren, R.; Wang, B. Physicochemical and textural characteristics and volatile compounds of semihard goat cheese as affected by starter cultures. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, M.M.; Chourasia, R.; Phukon, L.C.; Sarkar, P.; Ray, R.C.; Singh, S.P.; Rai, A.K. Lactic acid bacteria in the functional food industry: Biotechnological properties and potential applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 10730–10748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujović, M.; Mladenović, K.G.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T.; Laranjo, M.; Stefanović, O.D.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.D. Advantages and disadvantages of non-starter lactic acid bacteria from traditional fermented foods: Potential use as starters or probiotics. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1537–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boujamaai, M.; Mannani, N.; Aloui, A.; Errachidi, F.; Ben Salah-Abbès, J.; Riba, A.; Abbès, S.; Rocha, J.M.; Bartkiene, E.; Brabet, C.; et al. Biodiversity and biotechnological properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Moroccan sourdoughs. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutin, J.; Dufrene, F.; Guyot, P.; Palme, R.; Achilleos, C.; Bouton, Y.; Buchin, S. Microbial composition and viability of natural whey starters used in PDO Comté cheese-making. Food Microbiol. 2024, 121, 104521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, R.; Gazzillo, M.; Campolattano, N.; Sacco, M.; Muscariello, L. Isolation and Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Cultures of Buffalo and Cow Milk. Foods 2022, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chiara, I.; Marasco, R.; Della Gala, M.; Fusco, A.; Donnarumma, G.; Muscariello, L. Probiotic Properties of Lactococcus lactis Strains Isolated from Natural Whey Starter Cultures. Foods 2024, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, M.; Celano, G.; Serale, N.; Costantino, G.; Calabrese, F.M.; Calasso, M.; De Angelis, M. Dynamic microbial and metabolic changes during Apulian Caciocavallo cheese-making and ripening produced according to a standardized protocol. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6541–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, G.; Levante, A.; Lazzi, C.; Bottari, B.; Gatti, M.; Neviani, E. Dynamics of a natural bacterial community under technological and environmental pressures: The case of natural whey starter for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. Food Res. Int. 2020, 129, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, M.; Bottari, B.; Lazzi, C.; Neviani, E.; Mucchetti, G. Invited review: Microbial evolution in raw-milk, long-ripened cheeses produced using undefined natural whey starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, L.; Fornasari, M.E.; Gatti, M.; Lazzi, C.; Neviani, E.; Giraffa, G. Grana Padano cheese whey starters: Microbial composition and strain distribution. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 127, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, L.; Quadu, E.; Bortolazzo, E.; Bertoldi, L.; Randazzo, C.L.; Pizzamiglio, V.; Solieri, L. Insights on the bacterial composition of Parmigiano Reggiano Natural Whey Starter by a culture-dependent and 16S rRNA metabarcoding portrait. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellassi, P.; Fontana, A.; Morelli, L. Application of flow cytometry for rapid bacterial enumeration and cells physiological state detection to predict acidification capacity of natural whey starters. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.; Malcata, F.X.; Silva, C.C.G. Distinct Bacterial Communities in São Jorge Cheese with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). Foods 2023, 12, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolini, D.; Frisso, G.; Mauriello, G.; Salvatore, F.; Coppola, S. Microbial diversity in natural whey cultures used for the production of Caciocavallo Silano PDO cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giello, M.; La Storia, A.; Masucci, F.; Di Francia, A.; Ercolini, D.; Villani, F. Dynamics of bacterial communities during manufacture and ripening of traditional Caciocavallo of Castelfranco cheese in relation to cows’ feeding. Food Microbiol. 2017, 63, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, I.; Di Cagno, R.; Buchin, S.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Microbial ecology dynamics reveal a succession in the core microbiota involved in the ripening of pasta filata caciocavallo pugliese cheese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 6243–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Trana, A.; Sabia, E.; Di Rosa, A.R.; Addis, M.; Bellati, M.; Russo, V.; Dedola, A.S.; Chiofalo, V.; Claps, S.; Di Gregorio, P.; et al. Caciocavallo Podolico Cheese, a Traditional Agri-Food Product of the Region of Basilicata, Italy: Comparison of the Cheese’s Nutritional, Health and Organoleptic Properties at 6 and 12 Months of Ripening, and Its Digital Communication. Foods 2023, 12, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarquero, D.; Renes, E.; Combarros-Fuertes, P.; Fresno, J.M.; Tornadijo, M.E. Evaluation of technological properties and selection of wild lactic acid bacteria for starter culture development. LWT 2022, 171, 114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.L.; Houck, K.; Smukowski, M. 47. Milk and Milk Products. In Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schau, H.P. J. F. MacFaddin, Media for Isolation-Cultivation-Identification-Maintenance of Medical Bacteria, Volume I. XI + 929 S., 163 Abb., 94 Tab. Baltimore, London 1985. Williams and Wilkins. $ 90.00. ISBN: 0-683-05316-7. J. Basic Microbiol. 1986, 26, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Hertel, C.; Tannock, G.W.; Lis, C.M.; Munro, K.; Hammes, W.P. Detection of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella species in human feces by using group-specific PCR primers and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liasi, S.A.; Azmi, T.I.; Hassan, M.D.; Shuhaimi, M.; Rosfarizan, M.; Ariff, A.B. Antimicrobial activity and antibiotic sensitivity of three isolates of lactic acid bacteria from fermented fish product, Budu. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2009, 5, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Maragkoudakis, P.A.; Zoumpopoulou, G.; Miaris, C.; Kalantzopoulos, G.; Pot, B.; Tsakalidou, E. Probiotic potential of Lactobacillus strains isolated from dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, A.; D’ambrosio, S.; Cimini, D.; Falco, L.; D’Agostino, M.; Finamore, R.; Schiraldi, C. No Waste from Waste: Membrane-Based Fractionation of Second Cheese Whey for Potential Nutraceutical and Cosmeceutical Applications, and as Renewable Substrate for Fermentation Processes Development. Fermentation 2022, 8, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’ambrosio, S.; Ventrone, M.; Alfano, A.; Schiraldi, C.; Cimini, D. Microbioreactor (micro-Matrix) potential in aerobic and anaerobic conditions with different industrially relevant microbial strains. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 37, e3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, T.; Ricciardi, A.; Condelli, N.; Parente, E. Metataxonomic and metagenomic approaches for the study of undefined strain starters for cheese manufacture. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3898–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Guidone, A.; Matera, A.; De Filippis, F.; Mauriello, G.; Ricciardi, A. Microbial community dynamics in thermophilic undefined milk starter cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 217, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrokou, M.K.; Themeli, C.; Paramithiotis, S.; Mataragas, M.; Bosnea, L.; Argyri, A.A.; Chorianopoulos, N.G.; Skandamis, P.N.; Drosinos, E.H. Microbial Ecology of Greek Wheat Sourdoughs, Identified by a Culture-Dependent and a Culture-Independent Approach. Foods 2020, 9, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Yang, S.M.; Lim, B.; Park, S.H.; Rackerby, B.; Kim, H.Y. Design of PCR assays to specifically detect and identify 37 Lactobacillus species in a single 96 well plate. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parente, E.; Zotta, T.; Giavalisco, M.; Ricciardi, A. Metataxonomic insights in the distribution of Lactobacillaceae in foods and food environments. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 391–393, 110124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscariello, L.; Marino, C.; Capri, U.; Vastano, V.; Marasco, R.; Sacco, M. CcpA and three newly identified proteins are involved in biofilm development in Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2013, 53, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, S.; Ravi, K.; Srinivas, V.; Jadhav, S.; Khan, A.; Arun, A.; Riley, L.W.; Madhivanan, P. Comparison of culture-dependent and culture-independent molecular methods for characterization of vaginal microflora. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 66, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Food Safety Programme. Health Implications of Acrylamide in Food: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Consultation, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland, 25–27 June 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ercolini, D.; De Filippis, F.; La Storia, A.; Iacono, M. “Remake” by high-throughput sequencing of the microbiota involved in the production of water buffalo mozzarella cheese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8142–8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Maske, B.L.; De Dea Lindner, J.; Vale, A.S.; Favero, G.R.; Viesser, J.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Góes-Neto, A.; Soccol, C.R. An updated review on bacterial community composition of traditional fermented milk products: What next-generation sequencing has revealed so far? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1870–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarge, V.; Ogier, J.C.; Girard, V.; Maladen, V.; Leveau, J.Y.; Gruss, A.; Delacroix-Buchet, A. Raw cow milk bacterial population shifts attributable to refrigeration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5644–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, M.; Rossetti, L.; Bardelli, T.; Carminati, D.; Nazzicari, N.; Giraffa, G. Bacterial Community of Grana Padano PDO Cheese and Generical Hard Cheeses: DNA Metabarcoding and DNA Metafingerprinting Analysis to Assess Similarities and Differences. Foods 2021, 10, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penland, M.; Falentin, H.; Parayre, S.; Pawtowski, A.; Maillard, M.B.; Thierry, A.; Mounier, J.; Coton, M.; Deutsch, S.M. Linking Pélardon artisanal goat cheese microbial communities to aroma compounds during cheese-making and ripening. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 345, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbès, C.; Ali-Mandjee, L.; Montel, M.C. Monitoring bacterial communities in raw milk and cheese by culture-dependent and -independent 16S rRNA gene-based analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1882–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunziata, L.; Brasca, M.; Morandi, S.; Silvetti, T. Antibiotic resistance in wild and commercial non-enterococcal Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria strains of dairy origin: An update. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P.; Trymers, M.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Tkacz, K.; Zadernowska, A.; Modzelewska-Kapituła, M. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Context of Animal Production and Meat Products in Poland-A Critical Review and Future Perspective. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuben, R.C.; Roy, P.C.; Sarkar, S.L.; Alam, R.U.; Jahid, I.K. Isolation, characterization, and assessment of lactic acid bacteria toward their selection as poultry probiotics. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, N.; Mohamad, N.E.; Yeap, S.K.; Hussin, Y.; Aziz, M.N.M.; Masarudin, M.J.; Sharifuddin, S.A.; Hui, Y.W.; Ho, C.L.; Alitheen, N.B. Isolation and Characterization of Lactobacillus spp. from Kefir Samples in Malaysia. Molecules 2019, 24, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerlikaya, O. Probiotic potential and biochemical and technological properties of Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis strains isolated from raw milk and kefir grains. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Song, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.; Chai, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, H.; et al. AcrR1, a novel TetR/AcrR family repressor, mediates acid and antibiotic resistance and nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis F44. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6576–6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelarends, G.J.; Mazurkiewicz, P.; Konings, W.N. Multidrug transporters and antibiotic resistance in Lactococcus lactis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1555, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, A.B.; Mayo, B. Antibiotic Resistance-Susceptibility Profiles of Streptococcus thermophilus Isolated from Raw Milk and Genome Analysis of the Genetic Basis of Acquired Resistances. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokatlı, M.; Gülgör, G.; Bağder Elmacı, S.; Arslankoz İşleyen, N.; Özçelik, F. In Vitro Properties of Potential Probiotic Indigenous Lactic Acid Bacteria Originating from Traditional Pickles. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 315819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, J.W. Aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuben, R.C.; Roy, P.C.; Sarkar, S.L.; Rubayet Ul Alam, A.S.M.; Jahid, I.K. Characterization and evaluation of lactic acid bacteria from indigenous raw milk for potential probiotic properties. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigkrimani, M.; Panagiotarea, K.; Paramithiotis, S.; Bosnea, L.; Pappa, E.; Drosinos, E.H.; Skandamis, P.N.; Mataragas, M. Microbial Ecology of Sheep Milk, Artisanal Feta, and Kefalograviera Cheeses. Part II: Technological, Safety, and Probiotic Attributes of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolates. Foods 2022, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golomb, B.L.; Marco, M.L. Lactococcus lactis metabolism and gene expression during growth on plant tissues. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudeepa, E.S.; Bhavini, K. Review on Lactobacillus fermentum. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2020, 6, 719–726. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Leng, C.; Chen, H.; Sun, J.; Fan, X.; Li, A.; Feng, Z. Metabolic Profiles of Carbohydrates in Streptococcus thermophilus During pH-Controlled Batch Fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, R.; Masud, T.; Sohail, A.; Sammi, S.; Naz, R.; Sharma Khanal, B.K.; Nawaz, M.A. In vitro screening of EPS-producing Streptococcus thermophilus strains for their probiotic potential from Dahi. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorántfy, B.; Johanson, A.; Faria-Oliveira, F.; Franzén, C.J.; Mapelli, V.; Olsson, L. Presence of galactose in precultures induces lacS and leads to short lag phase in lactose-grown Lactococcus lactis cultures. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, E.H.E.; Nashat, S.; El-Sadek, N.; Metwaly, H.; El-Soda, M. Selection of wild lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Egyptian dairy products according to production and technological criteria. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zommara, M.; El-Ghaish, S.; Haertle, T.; Chobert, J.M.; Ghanimah, M. Probiotic and technological characterization of selected Lactobacillus strains isolated from different egyptian cheeses. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, G.; Casalino, L.; Di Paolo, M.; Sardo, A.; Vuoso, V.; Franco, C.M.; Marrone, R. Influence of Different Starter Cultures on Physical–Chemical, Microbiological, and Sensory Characteristics of Typical Italian Dry-Cured “Salame Napoli”. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus/Species/Subspecies | Primer | Sequence 5′ > 3′ | Target Gene | Amplicon Size (bp) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophilus | Str-THER-F2116 Str-THER-R2693 | GCTTGGTTCTGAGGGAAGC CTTTCTTCTGCACCGTATCCA | lacZ | 578 | [10] |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis | Lactis F 23 SRevLac | GCTGAAGGTTGGTACTTGTA AGTGCCAAGGCATCCACC | 16S rRNA (V1) and 16S/23S spacer region | 1824 | [10] |

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | PLc(A)For 23SRevLac | GGTGCTTGCACCAATTTGAA AGTGCCAAGGCATCCACC | 16S rRNA (V1) and 16S/23S spacer region | 1814 | [10] |

| L. fermentum | Lac-FER-F753 Lac-FER-R1062 | CCAGATCAGCCAACTTCACA GGCAAACTTCAAGAGGACCA | Arginine-ornitine antiporter | 310 | [10] |

| L. rhamnosus | PrI RhaII | CAGACTGAAAGTCTGACGG GCGATGCGAATTTCTATTATT | 16S rRNA (V1) and 16S/23S spacer region | 512 283 | [26] |

| L. helveticus | LHELV_F LHELV_R | ACGATGCTACTCACTCACAC GCACCTAATACTTCGATCCAAC | Phenylalanine tRNA ligase | 256 | This study |

| E. faecium | EfaeciumF EfaeciumR | GCAAGGCTTCTTAGAGA CATCGTGTAAGCTAACTTC | D-Ala Ala ligase | 575 | [10] |

| Strain | Origin | Respiratory Metabolism | Temperature (°C) | Media | Volume of Media | Agitation (RPM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophilus BA1 | Cow | Aerobic | 44 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| S. thermophilus BB6 | Cow | Aerobic | 44 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BA7 | Cow | Aerobic | 30 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BB8 | Cow | Aerobic | 30 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC9 | Cow | Aerobic | 30 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC10 | Cow | Aerobic | 30 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD1 | Cow | Aerobic | 30 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD5 | Cow | Aerobic | 30 | M17 | 40 | 150 |

| L. fermentum BF1 | Cow | Anaerobic | 37 | MRS | 45 | 0 |

| L. fermentum BF2 | Cow | Anaerobic | 37 | MRS | 45 | 0 |

| L. fermentum BE2 | Cow | Anaerobic | 37 | MRS | 45 | 0 |

| L. rhamnosus BF3 | Cow | Anaerobic | 37 | MRS | 45 | 0 |

| L. helveticus BE3 | Cow | Anaerobic | 37 | MRS | 45 | 0 |

| E. faecium BD6 | Cow | Aerobic | 37 | BHI | 40 | 150 |

| NWS Sample | Mesophilic Lactococci and Streptococci (ESTY) | Termophilic Lactococci and Streptococci (ESTY) | Enterococci and Others (BHI) | Mesophilic Lactobacilli (MRS) | Mesophilic Lactobacilli (Rogosa) | Mesophilic Lactobacilli (Enriched Culture) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow’s milk | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 7.07 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 9.6 ± 0.1 |

| Strain | AM 10 μg | TE 30 μg | P 10 μg | CN 10 μg | VA 30 μg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC9 | S | S | S | S | S |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BB8 | R | R | R | R | R |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC10 | R | R | R | R | R |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD5 | R | R | R | R | R |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BA7 | S | S | S | S | S |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD1 | R | R | R | R | R |

| S. thermophilus BA1 | R | R | R | R | R |

| S. thermophilus BB6 | S | S | S | R | S |

| L. fermentum BE2 | S | S | S | S | R |

| L. fermentum BF1 | S | S | S | S | R |

| L. fermentum BF2 | S | S | S | S | R |

| L. helveticus BE3 | S | S | S | R | S |

| L. rhamnosus BF3 | S | S | S | S | R |

| E. faecium BD6 | S | S | S | R | S |

| Strain | pH (4 h) | pH (6 h) | Final pH (24 h) | Viability (CFU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophiles BA1 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 5 × 102 |

| S. thermophiles BB6 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 6 × 106 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BA7 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 7 × 107 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BB8 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 4 × 107 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC9 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 4 × 107 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC10 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 9 × 107 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 2 × 106 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD5 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 4 × 106 |

| L. fermentum BF1 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 6 × 107 |

| L. fermentum BF2 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 9 × 108 |

| L. fermentum BE2 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 7 × 108 |

| L. rhamnosus BF3 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 9 × 108 |

| L. helveticus BE3 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 9 × 108 |

| E. faecium BD6 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 7 × 107 |

| Strain | OD600nm | Cell Dry Weight (g/L) | Final pH | Viability (CFU/mL) | Cell Dry WEIGHT/O.D. | Median with Standard Deviation (Cell Dry Weight/OD) for Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophiles BA1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 7 × 103 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.1 |

| S. thermophiles BB6 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 7 × 107 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BA7 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 3 × 108 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.41 ± 0.1 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BB8 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 4 × 108 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC9 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 1 × 108 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC10 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 4 × 108 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 3 × 108 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD5 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5 × 109 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | |

| L. fermentum BF1 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 9 × 107 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.33 ± 0.05 |

| L. fermentum BF2 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 9 × 107 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |

| L. fermentum BE2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 8 × 107 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| L. rhamnosus BF3 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 7 × 107 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| L. helveticus BE3 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4 × 107 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| E. faecium BD6 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 6 × 107 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Strain | 8 h | 24 h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid (g/L) | Ethanol (g/L) | Lactic Acid (g/L) | Ethanol (g/L) | Yield Yp/s (Lactic Acid Produced/Glucose–Lactose Consumed g/g) | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC9 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BC10 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD1 | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 11.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis BD5 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| L. fermentum BF1 | 12.5 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 12.5 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| L. fermentum BF2 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| L. fermentum BE2 | 12.8 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 12.5 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| L. rhamnosus BF3 | 14.0 ± 0.2 | ≤0.20 | 15.6 ± 0.2 | ≤0.20 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| L. helveticus BE3 | 13.2 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| E. faecium BD6 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Chiara, I.; Marasco, R.; Della Gala, M.; Alfano, A.; Parecha, D.; Costanzo, N.; Schiraldi, C.; Muscariello, L. Isolation and Partial Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Starter Culture. Fermentation 2025, 11, 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120668

De Chiara I, Marasco R, Della Gala M, Alfano A, Parecha D, Costanzo N, Schiraldi C, Muscariello L. Isolation and Partial Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Starter Culture. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):668. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120668

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Chiara, Ida, Rosangela Marasco, Milena Della Gala, Alberto Alfano, Darshankumar Parecha, Noemi Costanzo, Chiara Schiraldi, and Lidia Muscariello. 2025. "Isolation and Partial Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Starter Culture" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120668

APA StyleDe Chiara, I., Marasco, R., Della Gala, M., Alfano, A., Parecha, D., Costanzo, N., Schiraldi, C., & Muscariello, L. (2025). Isolation and Partial Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Natural Whey Starter Culture. Fermentation, 11(12), 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120668