Simple Summary

This study evaluated the effects of Histomonas meleagridis infection on growth performance, lesion indicators, and the composition of the cecal microbial community in chickens. The results showed that fourteen days post-infection represented the peak stage of disease development. Compared with the control group, infected chickens exhibited a significant reduction in body weight, along with severe lesions in the liver and cecum. At the same time, the abundance of beneficial bacteria in the cecum, such as Verrucomicrobia and Lactobacillus aviarius, decreased, whereas the abundance of harmful bacteria, including Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, increased. These findings contribute to a better understanding of microbial changes in the chicken cecum following infection with H. meleagridis.

Abstract

Histomonosis, caused by Histomonas meleagridis, leads to economic losses in the poultry and livestock industry. In recent years, studies on the role of intestinal microbiota in host physiological health have attracted growing attention. Understanding the changes in gut bacterial communities of chickens is crucial for improving poultry and livestock production. This study investigated the impact of Histomonas meleagridis infection on the growth performance, overall health, and cecal microbiota composition of chickens. Body weight changes and pathological alterations were assessed at different time points post-infection through animal experiments, with 7 days post-infection defined as the early stage and 14 days as the peak stage of infection. Cecal content samples were collected from the 7-day control group (G1), 7-day infected group (G2), 14-day control group (G3), and 14-day infected group (G4) for 16S rRNA sequencing analysis. The microbial diversity analysis revealed that H. meleagridis infection altered the number of microbial species in the cecal microbiota of chickens. The alpha diversity index was significantly reduced (p < 0.05), and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed significant structural differences between infected and control groups (p = 0.001). Taxonomic composition analysis showed that beneficial gut bacteria, such as Firmicutes and Lactobacillus spp., decreased in abundance, whereas Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, Escherichia spp., and Fusobacterium mortiferum were enriched in the infected group. LEfSe analysis indicated that G1 was enriched with Oscillospiraceae and Blautia; G2 with Christensenellaceae; G3 with Verrucomicrobia and Lactobacillus aviarius; and G4 with Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria. In conclusion, H. meleagridis infection markedly altered the cecal microbiota composition by shifting the relative abundances of beneficial and pathogenic bacteria, resulting in reduced microbial diversity.

1. Introduction

Histomonas meleagridis is a protozoan parasite responsible for histomonosis, commonly known as “blackhead disease” or infectious enterohepatitis [1,2]. Characteristic lesions occur in the liver and cecum, typically presenting as caseous cores in the cecum and volcanic crater-like focal necrosis on the liver surface [3]. The disease poses a serious threat to turkeys, with mortality rates reaching up to 100%. In chickens, while the mortality rate is comparatively lower, histomonosis significantly impairs production performance, resulting in decreased egg production, reduced body weight, and an elevated mortality rate that can persist for several weeks [4,5]. In recent years, concerns regarding food safety and public health have led to the progressive ban of nitroimidazole compounds, nitrofuran compounds, and other effective veterinary drugs in the United States, the European Union, and China [6,7,8,9,10]. The live attenuated vaccine obtained through serial in vitro passaging has demonstrated effective immunoprotection but has not yet been successfully commercialized [11,12,13]. This situation has created significant challenges in the prevention and control of histomonosis, necessitating urgent exploration of novel strategies. Previous in vitro studies have shown that Escherichia coli in the gut influences the energy absorption and metabolism of H. meleagridis [14], while in vivo research has revealed that the presence of H. meleagridis increases the relative abundance of E. coli, thereby exacerbating pathological changes [15,16]. Thus, elucidating the interactions between H. meleagridis and intestinal microbiota populations may provide critical insights for developing novel alternative therapies.

The intestinal microbiota refers to the microbial community inhabiting the animal gut, including trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and other microorganisms [17]. The chicken intestine harbors a highly diverse microbiota that interacts with the host to establish a stable and coordinated intestinal ecosystem [18]. Complex interactions between intestinal microorganisms and the host influence physiological balance, health, immunity, and production performance [19,20,21]. Recent studies have demonstrated that parasitic infections can induce gut microbiota dysbiosis, leading to intestinal barrier dysfunction and exacerbation of disease progression. Infection with Trichuris ovis significantly altered the diversity of the cecal microbiota in goats, increasing the abundance of opportunistic pathogens such as Proteobacteria and Bacteroides while reducing beneficial bacteria [22]. Entamoeba histolytica infection induced notable shifts in the gut microbiota of amoebiasis patients, characterized by an increased abundance of Prevotella copri, which was associated with inflammatory diarrhea [23]. Similarly, in broilers infected with Eimeria acervulina, the alpha diversity of the luminal and mucosal microbiota in the duodenum and jejunum was altered, manifested by a reduced abundance of short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria and an increased abundance of opportunistic pathogens [24]. Infection with Eimeria tenella modified the composition and structure of the cecal microbiota in broilers, leading to a decrease in beneficial commensals such as Lactobacillus spp. and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, while increasing the relative abundance of Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter jejuni [25,26,27]. However, current research on H. meleagridis infection and changes in the chicken gut microbiota has primarily focused on the phylum and genus levels, with no reports at the specific species level. Based on this background, the present study investigated changes in body weight, liver, and cecal lesions in chickens following H. meleagridis infection, as well as alterations in the cecal microbiota composition at the phylum, genus, and species levels during both the early and peak stages of infection. This approach aims to identify bacterial taxa associated with histomonosis and provide a basis for developing alternative strategies to mitigate the impact of the disease on the poultry industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Yangzhou University, under license no. SYXK (SU) 2021-0027 for chickens. All chickens were housed and handled in accordance with the principles of humane care and use of laboratory animals.

2.2. Animals

A total of 30 one-day-old white leghorn chickens were purchased from Jiangsu Boehringer Ingelheim Vitong Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China). The chickens were housed in an H. meleagridis-free environment, and their feed was supplemented with multivitamins and trace elements.

2.3. Parasite

The H. meleagridis strain JSYZ-D, isolated from the liver of an infected chicken in Yangzhou, is preserved in liquid nitrogen at the Parasite Laboratory of the School of Veterinary Medicine, Yangzhou University. After resuscitation, it was inoculated into a mixed medium consisting of 9 mL Medium 199 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1 mL of 10% inactivated horse serum (Gibco), supplemented with 11 mg of sterilized rice starch (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China), and incubated at 40 °C in an anaerobic incubator [28].

2.4. Experimental Design

At 14 days of age, all chickens were weighed and randomly divided into two groups—the H. meleagridis-infected group and the control group (after adjustment to ensure similar average body weights across groups). Each group consisted of 15 chickens, housed in separate cages. On the same day (14 days of age), each chicken in the experimental group was artificially infected via the cloacal route with 2.0 × 105 H. meleagridis. Prior to artificial infection, the number of H. meleagridis cells/mL was calculated by hemocytometer and trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) staining to ensure the viability of the parasites at the time of infection. Artificial infection was performed according to the method described by Beer et al. [11].

2.5. Sample Collection and Intestinal Lesion Score

On 7, 14, and 21 days post-infection, five chickens were randomly selected from both the infected group and the control group at each experimental time point. Thus, all chickens were divided into six groups according to the dissection time, with five chickens in each group. At the three experimental time points, the chickens in the infected and control groups were weighed and then euthanized via cervical dislocation, followed by lesion scoring of the cecum and liver. At each experimental time point, cecal contents were collected from each euthanized chicken, and these content samples were stored at −80 °C. Cecal content samples from the infected group and their corresponding control group chickens with severe lesions and high lesion scores were selected for microbial sequencing.

2.6. Lesion Scoring Rules

Cecal scoring criteria [29,30] were as follows: the longitudinal fold of the cecal wall was well-characterized and lacked macroscopical lesions, and the cecal contents were thick with dark feces and no caseous exudate, score 0; cecal wall thickening or presence of scattered petechiae, or both, score 1; moderate thickening of the cecal wall with caseous exudate or contents forming a caseous core, color change of cecal contents or absence of contents and bleeding spots in the cecum, score 2; the cecal wall was thickened, with a prominent caseous core of cecal contents, the cecum had no contents, or the cecal wall appeared petechiae, score 3; the wall of the cecum was significantly thickened, and the cecal mucosal layer appeared fibrotic necrotic and ulcerated, with a caseous core or no contents in the cecum, the presence of a hemorrhagic blind end, or cecal rupture leading to peritonitis, score 4. Liver scoring criteria were as follows [29,30]: no macroscopic round necrotic lesion, score 0; presence of 1–5 small, round necrotic foci (<5 mm in diameter), score 1; many small, round necrotic foci (≥5), or large necrotic foci (≥5 mm in diameter), score 2; many macroscopic small and large necrotic foci, score 3; presented with complex lesions and numerous mixed lesions, score 4. All lesions were scored without knowing the grouping.

2.7. DNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from cecum contents using the E.Z.N.A. soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and concentration of DNA extract were determined by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and kept at −80 °C prior to further use. The full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primer pairs 27F (5′-AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) using a T100 Thermal Cycler PCR thermocycler (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR reaction mixture included 4 μL 5 × Fast Pfu buffer, 2 μL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL of each primer (5 μM), 0.4 μL Fast Pfu polymerase, 10 ng of template DNA, and ddH2O to reach a final volume of 20 µL. PCR amplification cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 29 cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 45 s, and single extension at 72 °C for 10 min, ending at 4 °C. The PCR product was extracted from 2% agarose gel and purified using the PCR Clean-Up Kit (YuHua, Shanghai, China) according to manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced on an Illumina Nextseq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the standard protocols by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.8. Bioinformatic Analysis

Raw FASTQ files were de-multiplexed using an in-house perl script, and then quality-filtered by fastp version 0.19.6 and merged by FLASH version 1.2.7 with the following criteria: (i) The reads were truncated at any site receiving an average quality score of <20 over a 50 bp sliding window, and truncated reads shorter than 50 bp or reads containing ambiguous characters were discarded. (ii) Only overlapping sequences longer than 10 bp were assembled according to their overlapped sequence. The maximum mismatch ratio of overlap region was 0.2. Reads that could not be assembled were discarded. (iii) Samples were distinguished according to the barcode and primers, and the sequence direction was adjusted and exact barcode matching was performed, with a maximum 2-nucleotide mismatch in primer matching. Then, the optimized sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using UPARSE v7.0.1090 with 97% sequence similarity level. The most abundant sequence for each OTU was selected as a representative sequence. To minimize the effects of sequencing depth on alpha and beta diversity measurements, the number of 16S rRNA gene sequences from each sample was rarefied to 20,000, which still yielded an average Good’s coverage of 99.09%. The taxonomy of each OTU representative sequence was analyzed by RDP Classifier version 2.2 against the 16S rRNA gene database (e.g., Silva v138) using a confidence threshold of 0.7.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Bioinformatic analysis of gut microbiota was carried out using the Majorbio Cloud platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com, accessed on 28 February 2025). Based on the OTUs information, rarefaction curves and alpha diversity indices including observed OTUs, Chao1 richness, Shannon index, and Good’s coverage were calculated using Mothur v1.30.1. The similarity among the microbial communities in different samples was determined by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity using the Vegan v2.5-3 package. The PERMANOVA test was used to assess the percentage of variation explained by the treatment, along with its statistical significance, using Vegan v2.5-3 package. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/LEfSe, accessed on 28 February 2025) was performed to identify the significantly abundant taxa (phylum to genera) of bacteria among the different groups (LDA score > 4, p < 0.05).

IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 software (version 22.0; IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to conduct a one-way ANOVA test and one-dimensional variance descriptive statistical analysis on data such as body weight comparison and lesion scores from the six experimental groups of chickens, with (p < 0.05) as the significance judgment criterion.

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

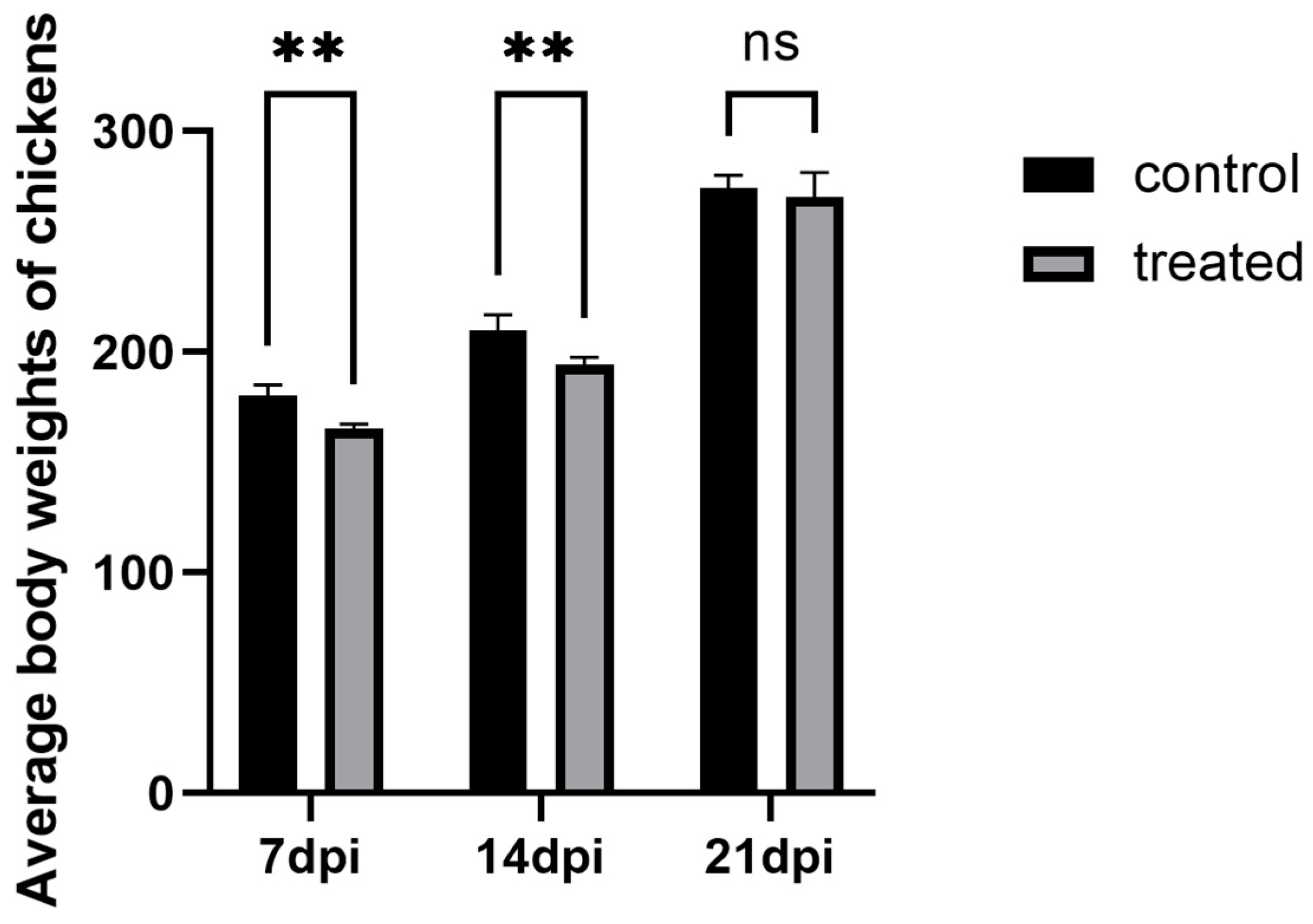

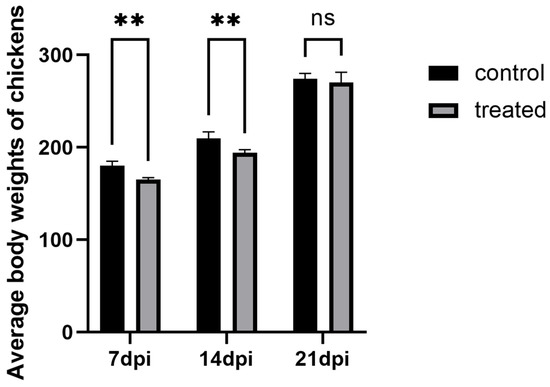

During the infection process, the chickens in each experimental group were weighed to obtain body weight comparison data. The results showed that significant differences in body weight were observed between the 7-day infected group and the control group, as well as between the 14-day infected group and the control group (p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was found in body weight in the 21-day experimental group (p > 0.05), suggesting that the severity of H. meleagridis infection was more pronounced at 7 days post-infection (dpi) and 14 days post-infection (dpi). The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The comparison of average body weights of layer hens across experimental groups. ** p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05.

3.2. Intestinal Lesion and Intestinal Lesion Score

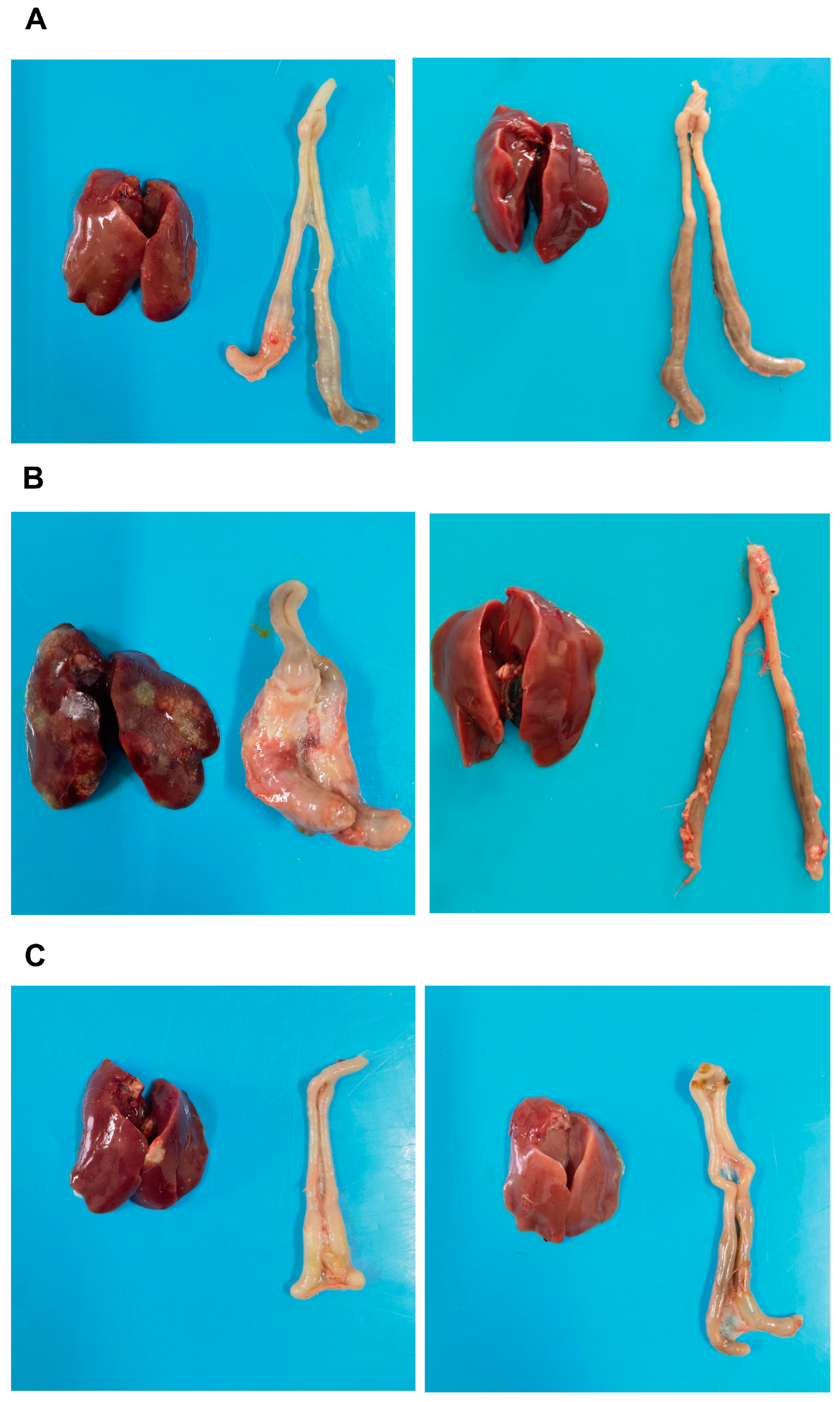

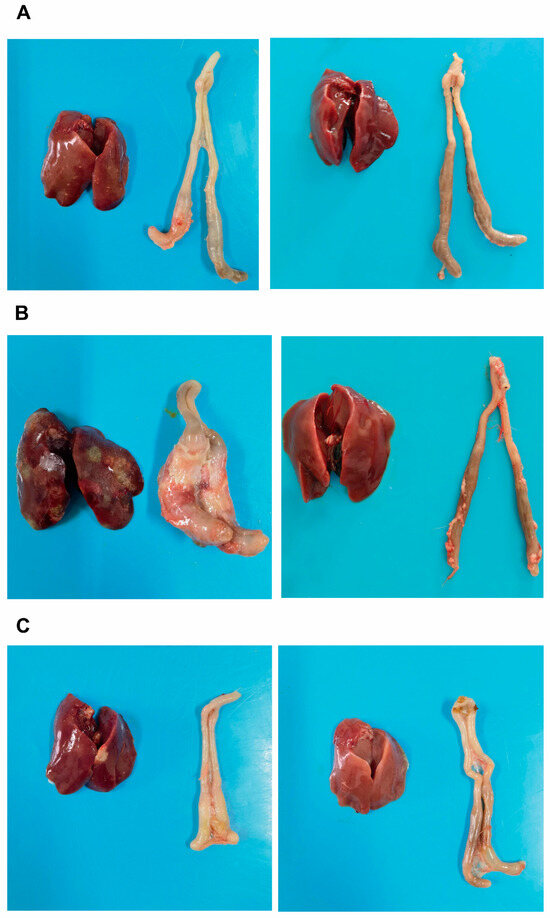

The chickens in each experimental group were dissected to observe pathological changes. The results showed that, in the 7 dpi group, during necropsy, a small number of chickens had crater-like necrotic foci on the liver, with the diameter of the necrotic foci being less than 5 mm, and an obvious cecal plug (Figure 2A, the left side of the image represents the infected group, while the right side represents the control group; the same applies below). In the 14 dpi group, most chickens exhibited liver enlargement, obvious congestion, and multiple crater-like necrotic foci, with some necrotic foci exceeding 5 mm in diameter; the liver was brittle and fragile. The cecum was significantly swollen, with increased volume, and when cut open, the cecal wall was thickened, adhered, and a cecal plug was visible inside (Figure 2B). In the 21 dpi group, during necropsy, a small number of chickens had necrotic foci on the liver, and the cecum was slightly swollen (Figure 2C); no pathological changes were observed in the control group.

Figure 2.

The comparison of liver and cecal lesion conditions across experimental groups. (A): Liver and cecum of the infected group (left) and control group (right) at 7 days post-infection (dpi); (B): Liver and cecum of the infected group (left) and control group (right) at 14 dpi; (C): Liver and cecum of the infected group (left) and control group (right) at 21 dpi.

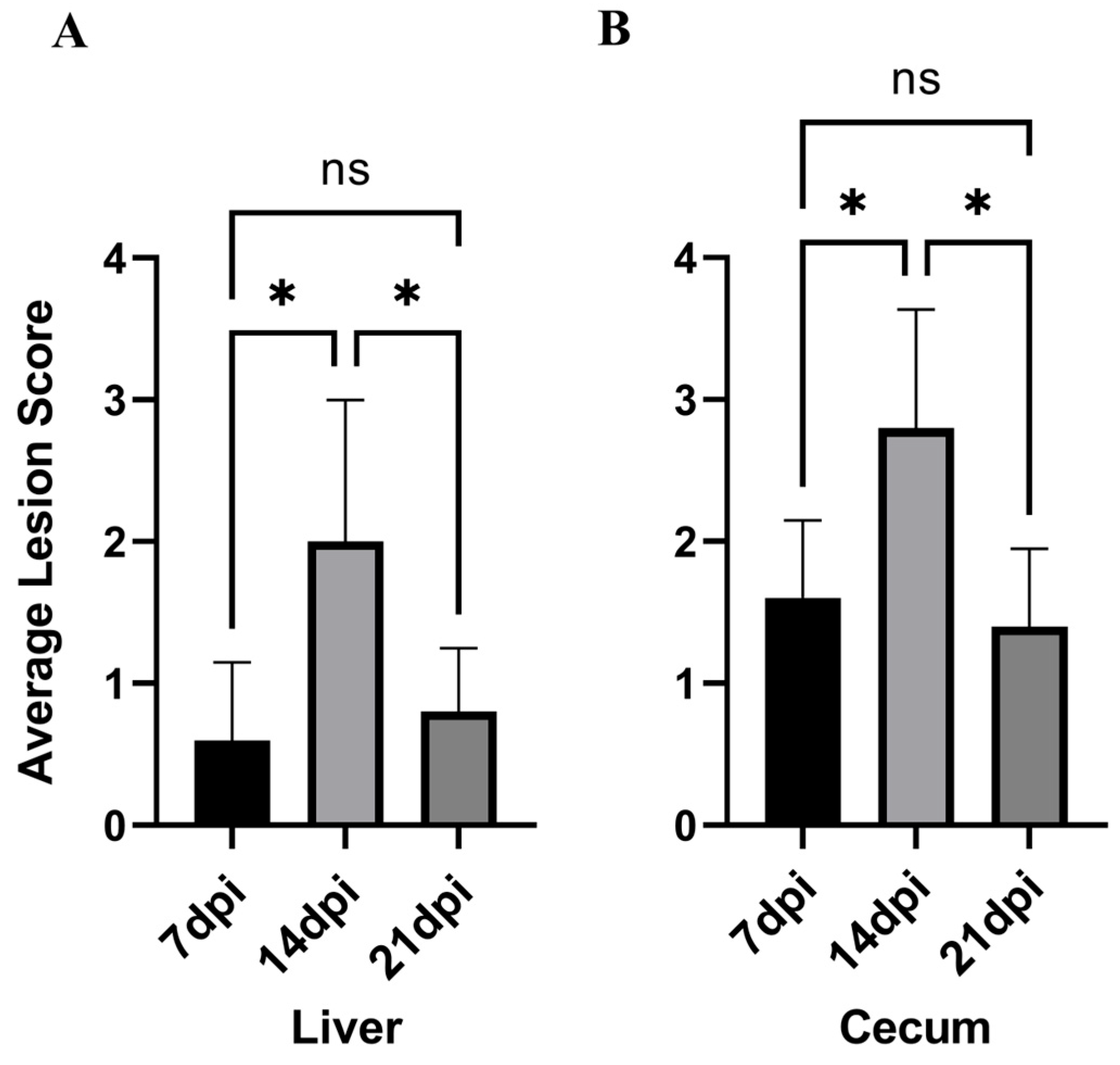

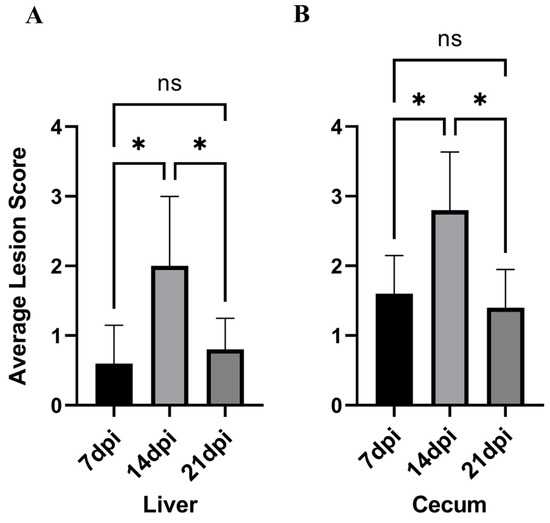

The average liver–cecum lesion scores of chickens in each experimental group are shown in Table 1 and Figure 3. It can be observed that the lesion score at 14 dpi is the highest, with the average liver–cecum lesion scores at 14 dpi significantly higher than those at 7 dpi (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the average liver–cecum lesion scores at 21 dpi were significantly lower than those at 14 dpi (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

The lesion scoring status across experimental group.

Figure 3.

The lesion scoring status across experimental groups. (A): Liver lesion score. (B): Cecum lesion score. * p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05.

Given that there was no significant difference in body weight between the infected and control groups at 21 days, and that the liver and cecal lesion scores were significantly reduced, we selected the following four groups for 16S rRNA sequencing analysis: the 7-day control group, the 7-day infected group, the 14-day control group, and the 14-day infected group.

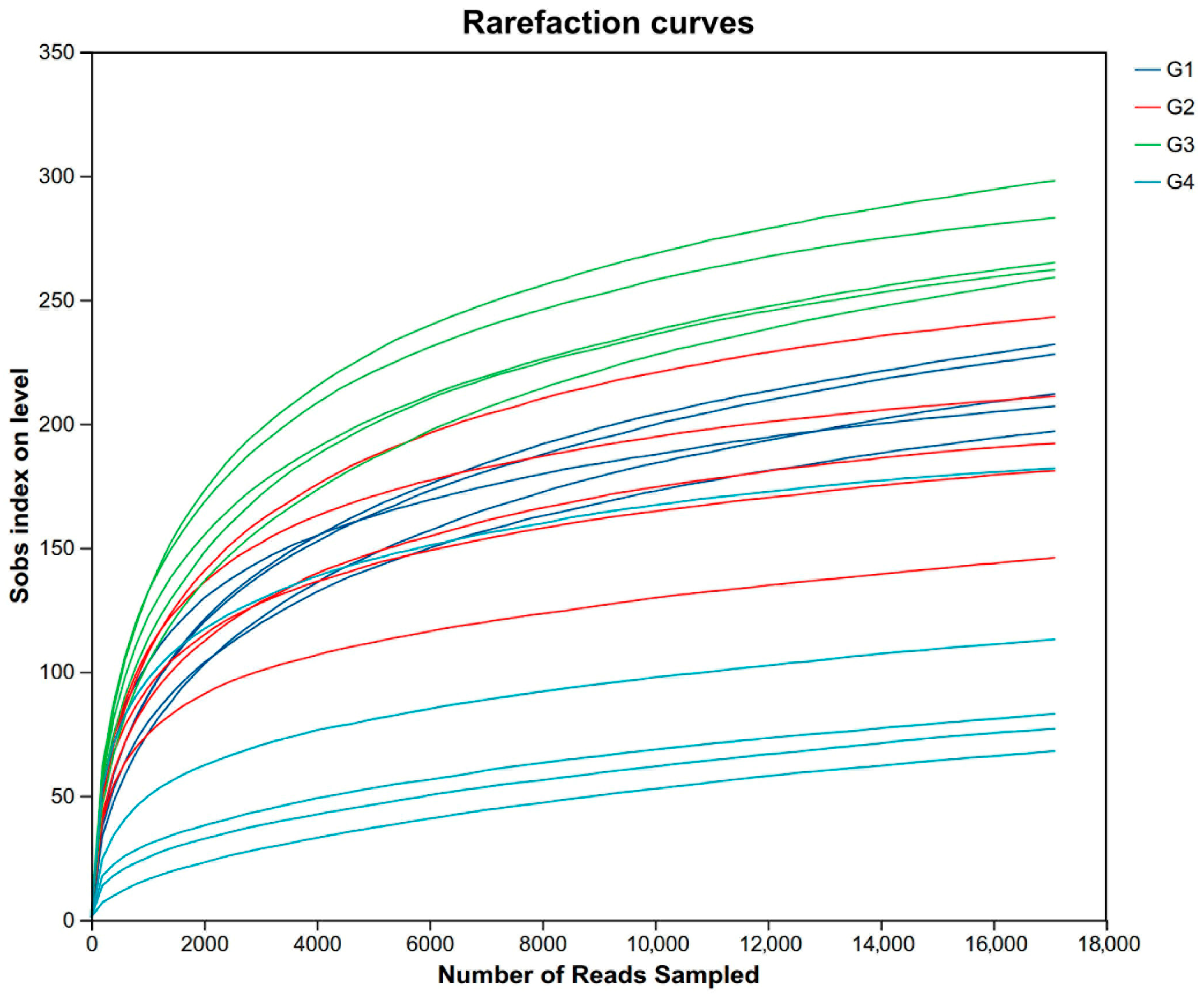

3.3. Rarefaction Curve and the Change in the Alpha and Beta of Cecal Gut Microbiota

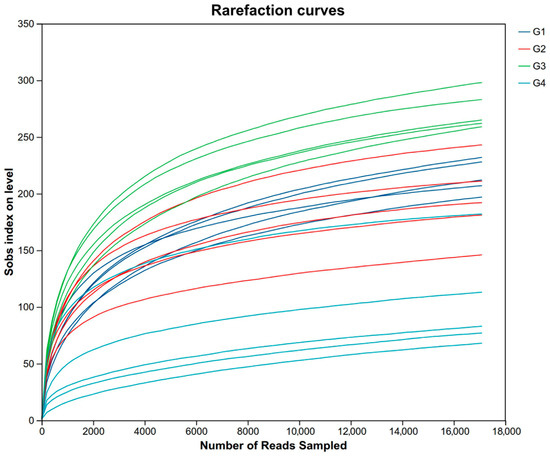

For descriptive convenience, the 7-day control group, the 7-day infected group, the 14-day control group, and the 14-day infected group are, respectively, designated as G1, G2, G3, and G4. After quality filtering and assembly, we obtained a total of 669,538 sequences; the average sequence lengths were 1458 bp per sample. The rarefaction curves of 20 samples stabilized as the data increased, indicating sufficient data sampling and sequencing depth to assess richness and microbial community diversity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The rarefaction curves of 20 samples. Abbreviations: G1, the 7-day control group; G2, the 7-day infected group; G3, the 14-day control group; G4, the 14-day infected group.

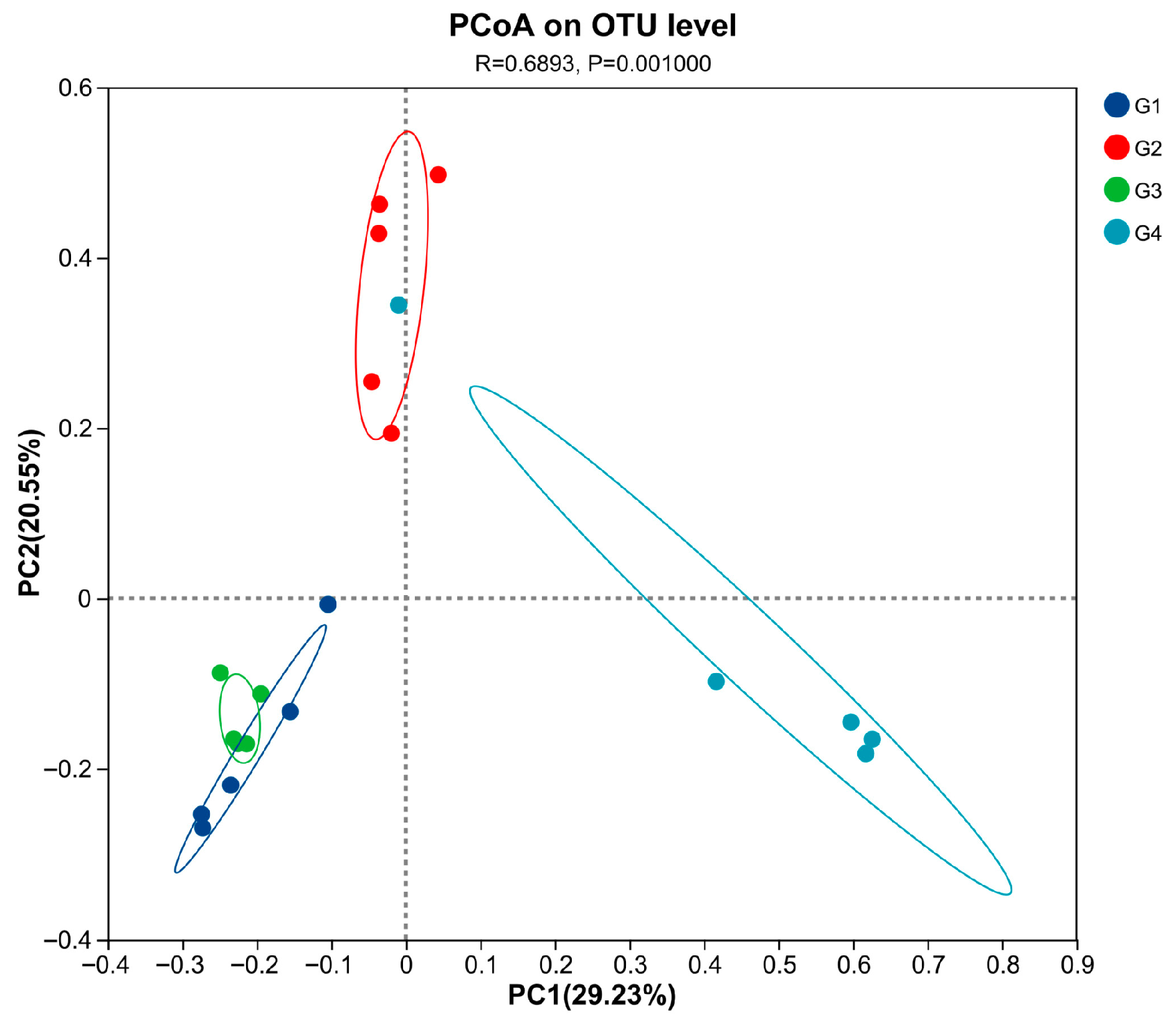

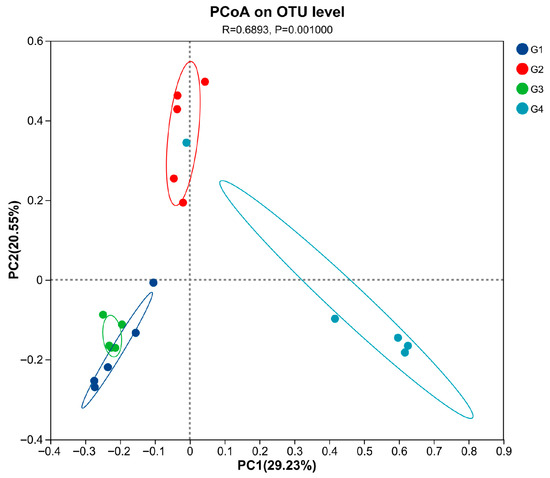

Compared with the control group (Table 2), there were no significant differences in the ACE, Chao, Shannon, and Simpson indices in the 7 dpi group (p > 0.05). The ACE, Chao, Shannon, and Sobs indices in the 14 dpi group were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). When comparing the 7 dpi group with the 14 dpi group, it was found that the ACE, Chao, Shannon, and Sobs indices at 14 dpi were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). The PCoA results (Figure 5) demonstrated significant differences in cecal microbiota diversity among the groups (p = 0.001). The cecal microbial structure distribution of the infected and control groups at 14 dpi showed distinct clustering on opposite sides, with significant separation. At 14 dpi, the microbial structure distribution of the cecal microbiota in the control and infected groups of chickens showed a clear left–right separation with a substantial distance between them. Compared to the control group, the infected group deviated toward the positive PC1 axis, and this deviation increased over time.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of alpha diversity indices across experimental groups.

Figure 5.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed at the OUT level based on weighted UniFrac distances for all samples. Abbreviations: G1, the 7-day control group; G2, the 7-day infected group; G3, the 14-day control group; G4, the 14-day infected group.

3.4. Analysis of the Composition and Differential Changes in Species Abundance of Cecal Microbiota in Chickens

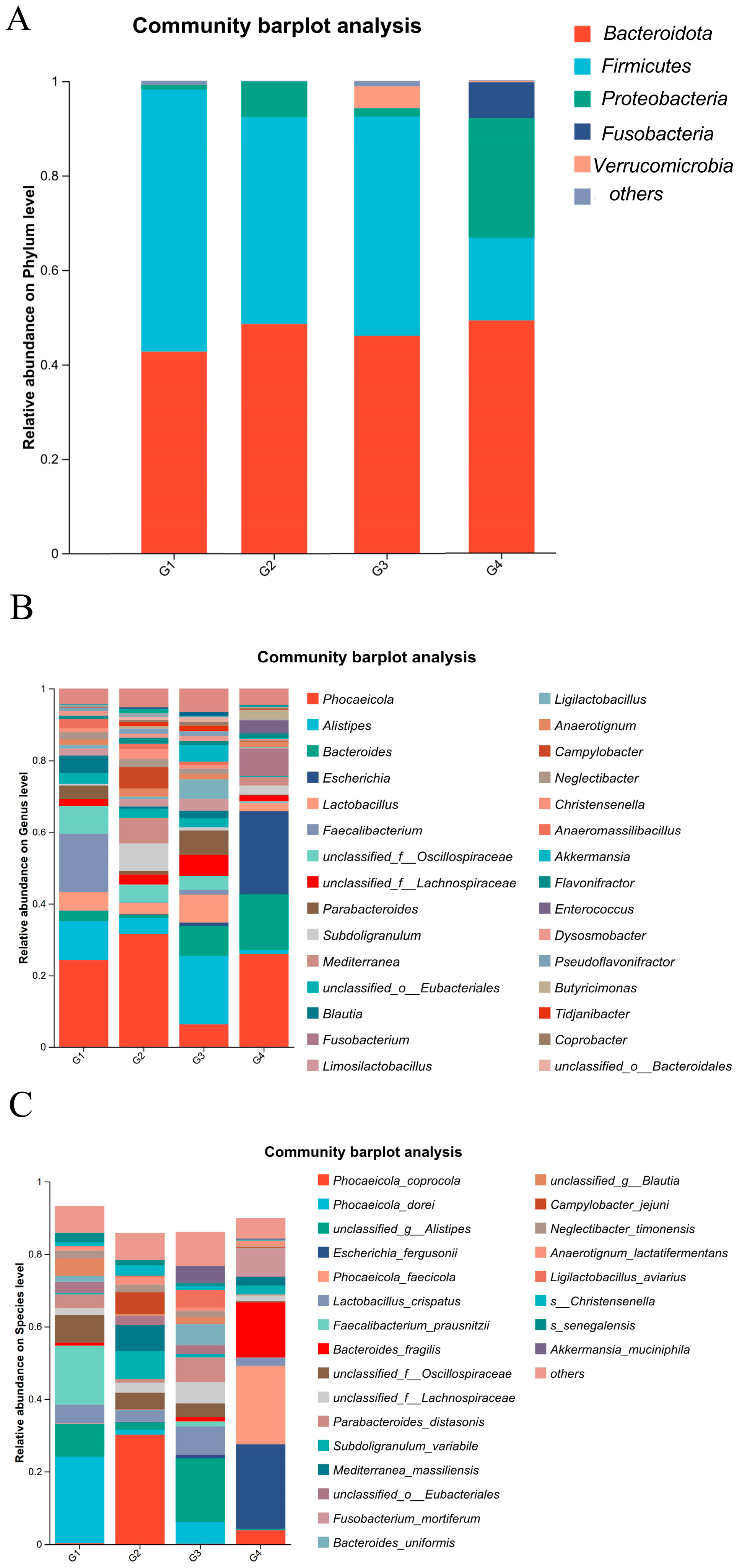

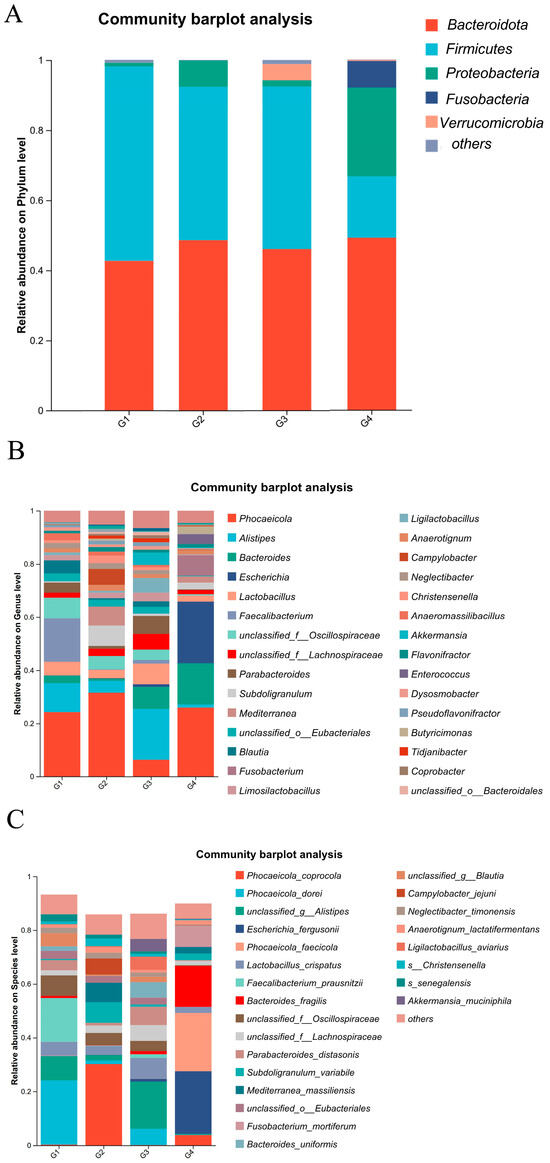

As illustrated in Figure 6A, at the phylum level, the dominant bacterial phyla in both the control and infected groups were Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, and Firmicutes, with the additional presence of Fusobacteria and Verrucomicrobia. After H. meleagridis infection, the abundance of Firmicutes decreased, whereas the abundances of Bacteroidota and Proteobacteria increased. Verrucomicrobia was detected in the control group, while Fusobacteria emerged in the infected group. Compared to the 7 dpi group, the 14 dpi group showed a further reduction in Firmicutes abundance and an elevation in Proteobacteria abundance.

Figure 6.

Composition of cecal microbiota species abundance. (A) The phylum level. (B) The genus level. (C) The species level. Abbreviations: G1, the 7-day control group; G2, the 7-day infected group; G3, the 14-day control group; G4, the 14-day infected group.

As shown in Figure 6B, at the genus level, the dominant bacterial genera in the chicken intestinal microbiota include Phocaeicola spp., Alistipes spp., Bacteroides spp., Escherichia spp., Lactobacillus spp., and Faecalibacterium spp. Following H. meleagridis infection, compared to the control group, the abundances of Phocaeicola spp., Bacteroides spp., Escherichia spp., Subdoligranulum spp., and Fusobacterium spp. increased, whereas the abundances of Alistipes spp., Lactobacillus spp., Parabacteroides spp., Mediterranea spp., Blautia spp., Limosilactobacillus spp., Ligilactobacillus spp., Anaerotignum spp., and Campylobacter spp. decreased. Compared to the 7 dpi group, the 14 dpi group exhibited increased abundances of Bacteroides spp., Escherichia spp., Fusobacterium spp., Enterococcus spp., and Mediterranea spp., while the abundances of Alistipes spp., Lactobacillus spp., Akkermansia spp., and Limosilactobacillus spp. decreased.

At the species level (Figure 6C), the dominant bacterial species in the chicken intestinal microbiota include Bacteroides fragilis, Lactobacillus crispatus, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Following H. meleagridis infection, compared to the control group, the abundance of Phocaeicola coprocola, Escherichia fergusonii, Bacteroides fragilis, Subdoligranulum variabile, Mediterranea massiliensis, Fusobacterium mortiferum, Anaerotignum lactatifermentans, and Campylobacter jejuni increased, while the abundances of Phocaeicola dorei, Phocaeicola faecicola, Lactobacillus crispatus, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Parabacteroides distasonis, Bacteroides uniformis, Ligilactobacillus aviravius, and Akkermansia muciniphila decreased. Compared to the 7 dpi group, the 14 dpi group exhibited a marked increase in the abundance of Escherichia fergusonii, Phocaeicola faecicola, Bacteroides fragilis, Mediterranea massiliensis, and Fusobacterium mortiferum, whereas the abundances of Phocaeicola coprocola, Lactobacillus crispatus, Subdoligranulum variabile, and Campylobacter jejuni showed a pronounced decline.

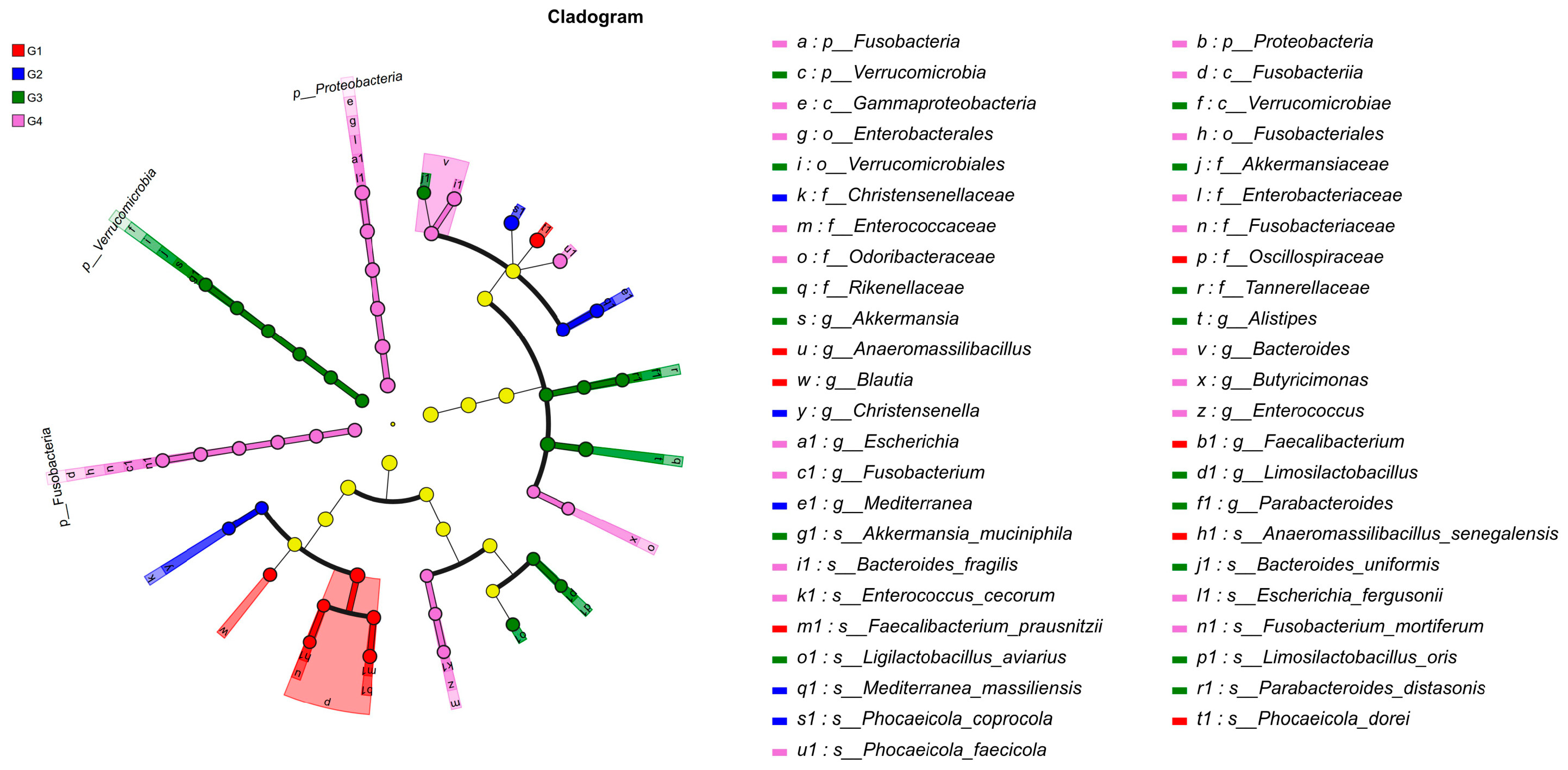

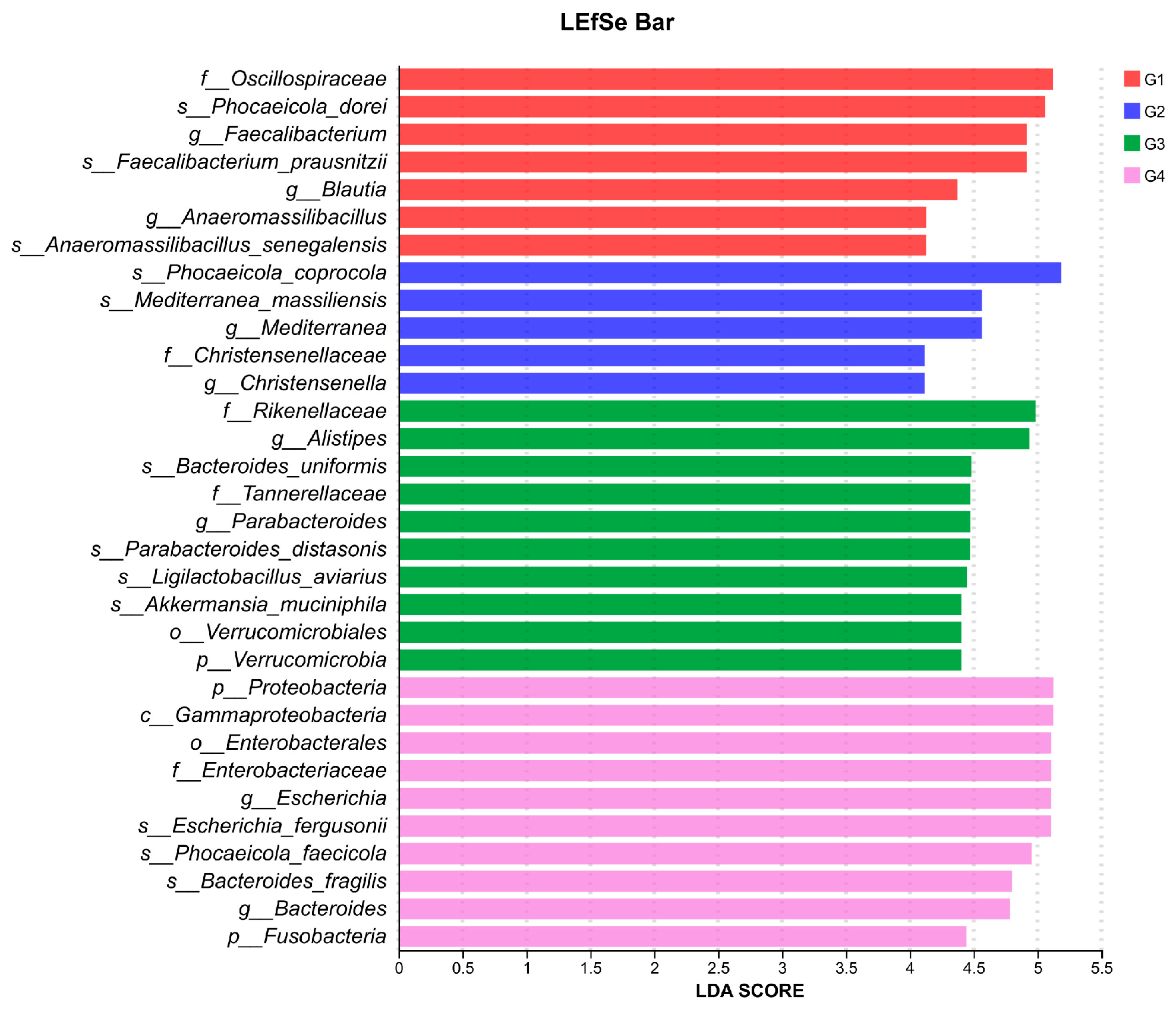

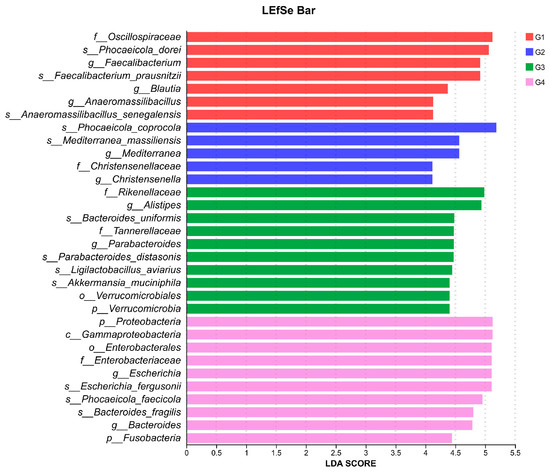

3.5. LEfSe-Based Discriminant Analysis of Multi-Level Species Differences in Cecal Microbiota Across Experimental Groups

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of H. meleagridis infection on the gut microbiota, we conducted LEfSe analysis. The taxonomic cladogram and LDA scores obtained from the LEfSe analysis confirmed and visualized the effects of infection (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Filtered by LEfSe analysis (LDA threshold of 4), it was found that at 7 dpi, the control group was enriched with Oscillospiraceae spp., Blautia spp., Phocaeicola dorei, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, while the infected group was enriched with Christensenella, Phocaeicola coprocola, and Mediterranea massiliensis; at 14 dpi, the control group showed enrichment of Verrucomicrobia, Rikenellaceae, Tannerellaceae, Akkermansiaceae, Alistipes spp., Bacteroides spp., Bacteroides uniformis, Ligilactobacillus aviarius, and Limosilactobacillus oris, whereas the infected group exhibited enrichment of Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Escherichia spp., Fusobacterium spp., Enterococcus spp., Escherichia fergusonii, Phocaeicola faecicola, and Bacteroides fragilis.

Figure 7.

LEfSe analysis of taxonomic biomarkers in cecal microbiota among experimental groups. Abbreviations: G1, the 7-day control group; G2, the 7-day infected group; G3, the 14-day control group; G4, the 14-day infected group.

Figure 8.

LDA scores obtained from the LEfSe analysis of the gut microbiota in different groups. An LDA effect size of greater than 4 was used as a threshold for the LEfSe analysis. Abbreviations: G1, the 7-day control group; G2, the 7-day infected group; G3, the 14-day control group; G4, the 14-day infected group.

4. Discussion

Histomonosis, a parasitic disease primarily affecting poultry, such as chickens and turkeys, is globally distributed and presents significant economic challenges to the poultry industry. The absence of prophylactic drugs and commercially available vaccines for treatment or prevention has led to increased efforts to control this disease [31]. Recent advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies have enabled a more comprehensive understanding of the gut microbiota, which comprise trillions of microorganisms residing in the animal intestine [32]. A stable gut microbiota community is closely linked to host health, with the microbiota playing a pivotal role in modulating the immune system and enhancing production performance [18,33,34].

In this study, experimental infection of white leghorns with H. meleagridis revealed the most pronounced differences in body weight and lesion scores at 7 dpi and 14 dpi compared to controls, whereas lesions alleviated and body weight gradually recovered by 21 dpi, consistent with previous findings [35,36]. We hypothesized that these changes in body weight and pathology might be associated with alterations in the cecal microbiota induced by H. meleagridis infection. Therefore, cecal contents from infected chickens at 7 and 14 dpi were selected for microbiota diversity analysis. The observed weight recovery may be attributed to the resolution of infection and restoration of physiological functions. However, it should be noted that this study involved a limited sample size, which may introduce potential survivor bias or selection bias, warranting further investigation.

Analysis of microbiota diversity indicated that H. meleagridis infection induced marked changes in the cecal microbiota, which were likely associated with the severity of pathological lesions. We therefore hypothesize that reduced diversity of the cecal microbiota is accompanied by more severe cecal lesions and greater body weight loss, suggesting a potential negative correlation between cecal microbiota diversity and pathological damage. This indicates that dysbiosis of the cecal microbiota plays an important role in the pathophysiological changes induced by H. meleagridis infection.

Following H. meleagridis infection, the alpha diversity of the cecal microbiota in chickens decreased throughout the course of infection, indicating a reduction in both microbial richness and evenness. This phenomenon is consistent with findings from studies on multiple intestinal parasites. Infection with E. tenella and E. necatrix have been shown to reduce the diversity of the cecal microbiota in chickens [37,38]. Similarly, Cryptosporidium infection causing diarrhea in goats and calves led to decreased gut microbiota diversity [39,40]. To elucidate the dynamic distribution of bacterial species, this study further analyzed bacterial composition at the phylum, genus, and species levels. The most frequently identified bacteria in the cecal microbiota of control group chickens were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and Fusobacteria, consistent with previous reports by Huang et al. [41]. This study revealed that following H. meleagridis infection, the abundances of Firmicutes and Verrucomicrobia decreased, while those of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria increased. A higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidota helps reduce pathogen colonization [42]. In this case, the ratio decreased, while the levels of inflammatory bacteria, such as Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, increased [43,44,45]. Based on the aforementioned changes, we propose that H. meleagridis infection alters the abundance of beneficial and pathogenic bacteria in the gut, which may influence the progression of histomonosis.

Following H. meleagridis infection, alterations were observed in the cecal microbiota at both the genus and species levels. Based on the cecal species composition, the abundances of L. crispatus, L. aviarius, Limosilactobacillus vaginalis, L. oris, and Limosilactobacillus reuteri were observed to decrease post-infection. Certain species of Lactobacillus spp. are well-established probiotics widely used in food and feed additives for disease prevention and treatment [46,47]. They ferment carbohydrates to produce lactic acid and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), secrete antimicrobial factors [48], promote mucus and sIgA secretion [49], modulate immune cytokine expression [50,51,52], and alter gut microbiota composition, thereby exerting antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and intestinal barrier-enhancing effects [53]. L. crispatus belongs to the genus Lactobacillus, is commonly found in the female urogenital tract, and helps combat colonization by uropathogens [54]. In livestock and poultry, L. crispatus produces lactic acid and lowers intestinal pH to inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria such as C. jejuni and Salmonella [55,56]. Additionally, L. aviarius, L. vaginalis, L. oris, and L. reuteri belong to the genera Ligilactobacillus spp. and Limosilactobacillus spp. within the phylum Firmicutes. The combined application of L. salivarius and L. reuteri in broilers has been shown to enhance intestinal morphology and increase the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 [57]. Furthermore, L. reuteri and L. vaginalis isolated from chicken ceca produce extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs), which facilitate intestinal colonization of beneficial bacteria and exhibit strong antibacterial activity against E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium in vitro [58]. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that H. meleagridis infection may lead to a relative reduction in the abundance of these species, thereby decreasing the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors and lactic acid, weakening the intestinal barrier. This could create opportunities for the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, consequently exacerbating pathological lesions.

In addition to the genus Lactobacillus, beneficial bacterial species such as Alistipes, F. prausnitzii, and A. muciniphila were also notably present in the control group. Similarly to Lactobacilli, Alistipes is a propionate producer capable of expressing acetyl-CoA carboxylase. It also expresses glutamate decarboxylase, influencing SCFA levels and the production of the metabolite γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [59]. F. prausnitzii produces butyrate with anti-inflammatory properties, increases the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 to reduce intestinal inflammation, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the Th17 pathway [60,61]. A. muciniphila, belonging to the phylum Verrucomicrobia, degrades mucin, enhances SCFA levels, and contributes to intestinal barrier protection and immune regulation [62]. A significant reduction in the abundance of these bacterial species was observed at 14 dpi. We hypothesize that the intestinal inflammation caused by H. meleagridis infection may be related to the decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria possessing anti-inflammatory functions.

In addition to the beneficial bacteria mentioned above, changes in certain pathogenic bacteria are also noteworthy. As the infection progressed, the abundance of Campylobacter increased at 7 dpi. C. jejuni, the predominant species within this genus and a zoonotic pathogen, employs capsular polysaccharide (CPS) production to evade the host immune system [63]. However, existing studies have demonstrated that lactobacilli possess anti-Campylobacter properties and can reduce C. jejuni loads [62]. By 14 dpi, the abundances of Escherichia spp. and Fusobacterium spp. increased, specifically manifested as a rise in E. fergusonii and F. mortiferum. Certain species of Fusobacterium can invade colonic epithelial cells and activate intracellular inflammatory signaling pathways [64]. A research indicated that E. fergusonii carries genes encoding the virulence factor heat-labile enterotoxin (LT), which is also present in enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) [65]. This toxin penetrates cells and induces apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells, although its activity can be suppressed by SCFAs [66]. In this study, we observed that C. jejuni increased significantly at 7 dpi but markedly decreased at 14 dpi, which we hypothesize may be suppressed by lactobacilli—particularly L. crispatus—consistent with earlier findings. Conversely, the notable increase in E. fergusonii and F. mortiferum at 14 dpi may have resulted from the reduction in beneficial bacterial populations. Therefore, we propose that the decline of these beneficial species likely impaired microbial metabolite levels and cytokine-mediated immune pathways, thereby leading to compromised intestinal barrier function and exacerbated inflammatory responses. As a consequence, more severe pathological manifestations were observed during the later stages of H. meleagridis infection. Although certain functional correlations of the aforementioned bacterial species have been described, this study lacks supporting functional data, such as metagenomics analyses, SCFA quantification, and transcriptomic profiling. Hence, the observed associations between these bacteria and histomonosis should be regarded as preliminary inferences based on current observations, and their functional relevance warrants further investigation.

Through LEfSe analysis, we observed that at 7 dpi, the control group was predominantly enriched with bacterial taxa possessing potential probiotic functions, including key butyrate- and acetate-producing genera such as Blautia and F. prausnitzii. The latter is recognized as a crucial marker of intestinal health, renowned for its anti-inflammatory properties, such as inducing regulatory T cells and generating anti-inflammatory metabolites [67]. Additionally, P. dorei and L. reuteri have also been associated with the maintenance of gut homeostasis [68,69]. In contrast, the 7 dpi group showed enrichment of Christensenellaceae. While Christensenellaceae is often linked to host leanness and is known to influence gut microbiota composition [70], with some studies indicate that its abundance may decrease under disease conditions [71]. Therefore, we hypothesize that early-stage H. meleagridis infection impairs the enrichment of beneficial bacteria in the gut, which may lead to impaired intestinal health and body weight loss in chickens.

As the infection progressed to 14 days, the control group exhibited enrichment in various taxa associated with mucosal health and complex carbohydrate metabolism. These included Akkermansiaceae (particularly A. muciniphila), a representative of the Verrucomicrobia phylum, which plays a key role in maintaining intestinal barrier function by degrading and promoting regeneration of the mucus layer [72,73], as well as members of the Bacteroides spp., which help prevent intestinal inflammation through production of IL-10 and acetate [74]. Conversely, the 14 dpi group demonstrated a marked increase in pathogenic bacteria. Enrichment of Proteobacteria is a classic signature of gut dysbiosis [75]. Among its members, the genus Escherichia (including the species E. fergusonii) represents an emerging zoonotic pathogen that has been isolated from chicken meat in certain regions and from human patients with diarrhea. This bacterium can express the heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) gene [76,77] and participates in carbon source metabolism, playing a significant role in host energy accumulation [78,79]. More notably, the enrichment of Fusobacteria and its representative Fusobacterium spp. is particularly significant, as this phylum has been associated with colorectal cancer in humans [80] and can elevate levels of cytotoxic (CD8+) T cells to enhance anti-tumor responses. Additionally, the enrichment of Bacteroides fragilis warrants attention, as certain subtypes (such as enterotoxigenic ETBF) are established pathogenic factors [81]. Based on the above research findings, we hypothesize that under H. meleagridis infection, the abundance of pathogenic bacteria in the chicken gut increases, while the populations of metabolic and beneficial bacterial species decrease. This may adversely affect the growth performance and intestinal barrier function of chickens, leading to aggravated pathological severity.

The LEfSe analysis clearly delineates the structural changes in the gut microbiota induced by H. meleagridis infection: the early stage is characterized by a relative reduction in commensal/beneficial bacteria and an increase in specific bacterial families, while the later stage transitions to a dysbiotic state marked by a significant increase in Proteobacteria (particularly Escherichia), Fusobacteria, and opportunistic pathogens such as B. fragilis. We propose that this microbial shift may be linked to the pathological progression of H. meleagridis infection and the exacerbation of intestinal inflammation. However, our studies have indicated that LEfSe analysis requires a substantial volume of sequencing data to yield accurate results [82,83]. In contrast, the data sample size utilized in this study is relatively limited, which imposes constraints on identifying biomarker species affected by H. meleagridis. Therefore, further investigation is warranted.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrates that Histomonas meleagridis infection results in reduced body weight, as well as cecal and hepatic lesions in chickens, leading to decreased species richness in the cecal microbiota, a reduced alpha diversity index of the gut microbial community, and alterations in the composition and structure of the cecal microbiome. Notably, the abundance of non-pathogenic bacteria significantly diminished. Conversely, the abundance of opportunistic pathogens increased. This research provides a more comprehensive theoretical foundation for understanding the interactions between parasites and gut microbiota. Furthermore, these findings may offer new strategic insights for preventing and controlling histomoniasis through microbial intervention strategies. However, the findings of this study still require validation with larger sample sizes and more functional data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X., Q.C., and Y.L.; methodology, Q.C.; software, Q.C.; validation, W.Z., H.A., R.L., Y.L., and Q.C.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Q.C. and Y.L.; resources, J.T., Z.H., and Y.Y.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.C. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and Q.C.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, J.X. and D.L.; project administration, Z.H.; funding acquisition, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 31772727, the 111 Project D18007, the open project YF202503 of the Key Laboratory of poultry preventive medicine of the Ministry of Education, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD); the Jiangsu Co-innovation Center for Prevention and Control of Important Animal Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses provided experimental equipment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Yangzhou University (Protocol No. 202203043, Date: 3 March 2022). All chickens were handled in accordance with the good animal practices required by the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China. This study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available. Raw sequence reads were uploaded to the NCBI BioProject databank (PRJNA 1338818).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Beer, L.C.; Petrone-Garcia, V.M.; Graham, B.D.; Hargis, B.M.; Tellez-Isaias, G.; Vuong, C.N. Histomonosis in Poultry: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 880738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Liebhart, D.; Bilic, I.; Ganas, P. Histomonas meleagridis—New Insights into an Old Pathogen. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 208, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kong, L.; Tao, J.; Xu, J. An Outbreak of Histomoniasis in Backyard Sanhuang Chickens. Korean J. Parasitol. 2018, 56, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhart, D.; Sulejmanovic, T.; Grafl, B.; Tichy, A.; Hess, M. Vaccination against Histomonosis Prevents a Drop in Egg Production in Layers Following Challenge. Avian Pathol. 2013, 42, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebhart, D.; Hess, M. Spotlight on Histomonosis (Blackhead Disease): A Re-Emerging Disease in Turkeys and Chickens. Avian Pathol. 2020, 49, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.G.; Wang, S.; Rong, J.; Chen, C.; Hou, Z.F.; Liu, D.D.; Tao, J.P.; Xu, J.J. Inhibitory Effects of Different Plant Extracts on Histomonas meleagridis In Vitro and In Vivo in Chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 337, 110487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Paker, C.; Graham, D.; Hargis, B.M.; Jenkins, M.C. Histomonas meleagridis Infections in Turkeys in the USA: A Century of Progress, Resurgence, and Tribute to Its Early Investigators, Theobald Smith, Ernst Tyzzer, and Everett Lund. J. Parasitol. 2024, 110, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebhart, D.; Ganas, P.; Sulejmanovic, T.; Hess, M. Histomonosis in Poultry: Previous and Current Strategies for Prevention and Therapy. Avian Pathol. 2017, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougald, L.R. Blackhead Disease (Histomoniasis) in Poultry: A Critical Review. Avian Dis. 2005, 49, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.R.; Shaw, A.L.; Hungerford, L.L.; Messenheimer, J.R.; Zhou, T.; Pillai, P.; Omer, A.; Gilbert, J.M. Regulatory Considerations for the Approval of Drugs Against Histomoniasis (Blackhead Disease) in Turkeys, Chickens, and Game Birds in the United States. Avian Dis. 2016, 60, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, L.C.; Graham, B.D.M.; Barros, T.L.; Latorre, J.D.; Tellez-Isaias, G.; Fuller, A.L.; Hargis, B.M.; Vuong, C.N. Evaluation of Live-Attenuated Histomonas meleagridis Isolates as Vaccine Candidates against Wild-Type Challenge. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.G.; Kong, L.M.; Rong, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Hou, Z.-F.; Liu, D.-D.; Tao, J.-P.; Xu, J.-J. Evaluation of an Attenuated Chicken-Origin Histomonas meleagridis Vaccine for the Prevention of Histomonosis in Chickens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1491148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Liebhart, D.; Grabensteiner, E.; Singh, A. Cloned Histomonas meleagridis Passaged in Vitro Resulted in Reduced Pathogenicity and Is Capable of Protecting Turkeys from Histomonosis. Vaccine 2008, 26, 4187–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilic, I.; Hess, M. Interplay between Histomonas meleagridis and Bacteria: Mutualistic or Predator–Prey? Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhamid, M.K.; Quijada, N.M.; Dzieciol, M.; Hatfaludi, T.; Bilic, I.; Selberherr, E.; Liebhart, D.; Hess, C.; Hess, M.; Paudel, S. Co-Infection of Chicken Layers with Histomonas meleagridis and Avian Pathogenic Escherichia Coli Is Associated with Dysbiosis, Cecal Colonization and Translocation of the Bacteria from the Gut Lumen. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 586437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganas, P.; Liebhart, D.; Glösmann, M.; Hess, C.; Hess, M. Escherichia Coli Strongly Supports the Growth of Histomonas meleagridis, in a Monoxenic Culture, without Influence on Its Pathogenicity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2012, 42, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehata, A.A.; Tellez-Isaias, G.; Eisenreich, W. (Eds.) Alternatives to Antibiotics Against Pathogens in Poultry; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-70479-6. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, D.; Hughes, R.J.; Moore, R.J. Microbiota of the Chicken Gastrointestinal Tract: Influence on Health, Productivity and Disease. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 4301–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofori, F.; Dargenio, V.N.; Dargenio, C.; Miniello, V.L.; Barone, M.; Francavilla, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 578386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, A.; Waheed, J.; Hamza, A.; Mohyuddin, S.G.; Lu, Z.; Namula, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.J. The Role of Intestinal Microbiota in Chicken Health, Intestinal Physiology and Immunity. JAPS J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2020, 31, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, T.; Luo, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wang, D.; Wu, C.; Fang, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Miao, J.; et al. Impact of Gut Microbial Diversity on Egg Production Performance in Chickens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e01927-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.H.; Malik, I.M.; Tak, H.; Ganai, B.A.; Bharti, P. Host, Parasite, and Microbiome Interaction: Trichuris Ovis and Its Effect on Sheep Gut Microbiota. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 333, 110356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Padalia, J.; Moonah, S. Tissue Destruction Caused by Entamoeba Histolytica Parasite: Cell Death, Inflammation, Invasion, and the Gut Microbiome. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2019, 6, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, P.M.; Miska, K.B.; Jenkins, M.C.; Yan, X.; Proszkowiec-Weglarz, M. Effects of Eimeria acervulina Infection on the Luminal and Mucosal Microbiota of the Duodenum and Jejunum in Broiler Chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1147579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, M.C.; Katarzyna, B.M.; Stanislaw, K.; Mark, C.J.; Jonathan, S. Effects of Eimeria tenella on Cecal Luminal and Mucosal Microbiota in Broiler Chickens. Avian Dis. 2022, 66, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zhao, G.X.; Huang, H.B.; Li, H.R.; Shi, C.W.; Yang, W.T.; Jiang, Y.L.; Wang, J.Z.; Ye, L.P.; et al. Dissection of the Cecal Microbial Community in Chickens after Eimeria tenella Infection. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.E.; Van Diemen, P.M.; Martineau, H.; Stevens, M.P.; Tomley, F.M.; Stabler, R.A.; Blake, D.P. Impact of Eimeria tenella Coinfection on Campylobacter jejuni Colonization of the Chicken. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00772-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Kolbe, T.; Grabensteiner, E.; Prosl, H. Clonal Cultures of Histomonas meleagridis, Tetratrichomonas gallinarum and a Blastocystis sp. Established through Micromanipulation. Parasitology 2006, 133, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; McDougald, L.R. Blackhead Disease (Histomonas meleagridis) Aggravated in Broiler Chickens by Concurrent Infection with Cecal Coccidiosis (Eimeria tenella). Avian Dis. 2001, 45, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Fuller, L.; McDougald, L.R. Infection of Turkeys with Histomonas meleagridis by the Cloacal Drop Method. Avian Dis. 2004, 48, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Kimminau, E. Critical Review: Future Control of Blackhead Disease (Histomoniasis) in Poultry. Avian Dis. 2017, 61, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhuang, W.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, H.; Yao, Y.; Sun, X.; Hu, W. Research Progress in High-Throughput DNA Synthesis and Its Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 7973–8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbin, J.T.; Gong, J.; Orouji, S.; Esufali, J.; Mallick, A.I.; Parvizi, P.; Shewen, P.E.; Sharif, S. Oral Treatment of Chickens with Lactobacilli Influences Elicitation of Immune Responses. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; McWhorter, A.R.; Willson, N.L.; Andrews, D.M.; Underwood, G.J.; Moore, R.J.; Hao Van, T.T.; Chousalkar, K.K. Vaccine Protection of Broilers against Various Doses of Wild-Type Salmonella Typhimurium and Changes in Gut Microbiota. Vet. Q. 2025, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, R.; Hafez, H.M. Experimental Infections with the Protozoan Parasite Histomonas meleagridis: A Review. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Rong, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Hou, Z.; Liu, D.; Tao, J.; et al. MicroRNA Expression Profile of Chicken Liver at Different Times after Histomonas meleagridis Infection. Vet. Parasitol. 2024, 329, 110200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, Z.; Broadwater, C.; Tobin, I.; Liu, J.; Whitmore, M.; Zhang, G. Is Intestinal Microbiota Fully Restored After Chickens Have Recovered from Coccidiosis? Pathogens 2025, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, F.U.; Yang, Y.; Leghari, I.H.; Lv, F.; Soliman, A.M.; Zhang, W.; Si, H. Transcriptome Analysis Revealed Ameliorative Effects of Bacillus Based Probiotic on Immunity, Gut Barrier System, and Metabolism of Chicken under an Experimentally Induced Eimeria tenella Infection. Genes 2021, 12, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbek-Kolin, E.; Husso, A.; Niku, M.; Loch, M.; Pessa-Morikawa, T.; Niine, T.; Kaart, T.; Iivanainen, A.; Orro, T. Faecal Microbiota in Two-Week-Old Female Dairy Calves during Acute Cryptosporidiosis Outbreak–Association with Systemic Inflammatory Response. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 151, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammeri, M.; Obregón, D.A.; Chevillot, A.; Polack, B.; Julien, C.; Pollet, T.; Cabezas-Cruz, A.; Adjou, K.T. Cryptosporidium Parvum Infection Depletes Butyrate Producer Bacteria in Goat Kid Microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 548737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, K.; Jiang, F.; Wang, H.; Tang, D.; Liu, D.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; He, X.; et al. The Chicken Gut Metagenome and the Modulatory Effects of Plant-Derived Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids. Microbiome 2018, 6, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Shen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tang, J.; Hou, S.; Xie, M. Effects of Total Dietary Fiber on Cecal Microbial Community and Intestinal Morphology of Growing White Pekin Duck. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 727200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Shan, X.; Zhang, R.; Xing, H.; Zhang, T.; et al. Alterations of Intestinal Mucosal Barrier, Cecal Microbiota Diversity, Composition, and Metabolites of Yellow-Feathered Broilers under Chronic Corticosterone-Induced Stress: A Possible Mechanism Underlying the Anti-Growth Performance and Glycolipid Metabolism Disorder. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03473-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, S.; Sujino, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Yoshimatsu, Y.; Harada, Y.; Nishiyama, K.; Aoto, Y.; Adachi, K.; Hayashi, N.; Amafuji, K.; et al. D-Amino Acids Ameliorate Experimental Colitis and Cholangitis by Inhibiting Growth of Proteobacteria: Potential Therapeutic Role in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 16, 1011–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Shi, L.; Ge, Y.; Leng, D.; Zeng, B.; Wang, T.; Jie, H.; Li, D. Dynamic Changes in the Gut Microbial Community and Function during Broiler Growth. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01005-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, N.; Sunder, J.; De, A.K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Joardar, S.N. Probiotics in Poultry: A Comprehensive Review. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2024, 85, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un-Nisa, A.; Khan, A.; Zakria, M.; Siraj, S.; Ullah, S.; Tipu, M.K.; Ikram, M.; Kim, M.O. Updates on the Role of Probiotics against Different Health Issues: Focus on Lactobacillus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Growth, Health, Rumen Fermentation, and Bacterial Community of Holstein Calves Fed Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG during the Preweaning Stage1. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Hou, C.; Zeng, X.; Qiao, S. The Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria as a Probiotic in Swine Diets. Pathogens 2015, 4, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Tsen, H.Y.; Lin, C.L.; Yu, B.; Chen, C.S. Oral Administration of a Combination of Select Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains to Reduce the Salmonella Invasion and Inflammation of Broiler Chicks. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.S.; Yoon, J.H.; Jung, J.Y.; Joo, S.Y.; An, S.H.; Ban, B.C.; Kong, C.; Kim, M. The Modulatory Effects of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Strain NSMJ56 on Gut Immunity and Microbiome in Early-Age Broiler Chickens. Animals 2022, 12, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, R.; Mortada, M.; Cosby, D.E.; Singh, M.; Applegate, T.J.; Syed, B.; Pender, C.M.; Curry, S.; Murugesan, G.R.; Selvaraj, R.K. Synbiotic Supplementation to Decrease Salmonella Colonization in the Intestine and Carcass Contamination in Broiler Birds. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qian, K.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y. Roles of Probiotic Lactobacilli Inclusion in Helping Piglets Establish Healthy Intestinal Inter-environment for Pathogen Defense. Probiotics Antimicro. 2018, 10, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, K.F.; Parris, J.; Engelbrecht, K.; Reid, G.; Burton, J.P. Interconnected Microbiomes—Insights and Innovations in Female Urogenital Health. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 1378–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobierecka, P.A.; Wyszyńska, A.K.; Aleksandrzak-Piekarczyk, T.; Kuczkowski, M.; Tuzimek, A.; Piotrowska, W.; Górecki, A.; Adamska, I.; Wieliczko, A.; Bardowski, J.; et al. In Vitro Characteristics of Lactobacillus spp. Strains Isolated from the Chicken Digestive Tract and Their Role in the Inhibition of Campylobacter Colonization. MicrobiologyOpen 2017, 6, e00512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal-McKinney, J.M.; Lu, X.; Duong, T.; Larson, C.L.; Call, D.R.; Shah, D.H.; Konkel, M.E. Production of Organic Acids by Probiotic Lactobacilli Can Be Used to Reduce Pathogen Load in Poultry. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavan, N.; Gupta, M.; Bahiram, K.B.; Korde, J.P.; Kadam, M.; Dhok, A.; Kumar, S. Ligilactobacillus salivarius and Limosilactobacillus reuteri Improve Growth and Intestinal Health in Broilers Via Modulating Gut Microbiota and Immune Response. Res. Vet. Sci. 2024, 194, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoka, M.S.R.; Mehwish, H.M.; Hayat, H.F.; Hussain, N.; Sarwar, S.; Aslam, H.; Nadeem, A.; Shi, J. Characterization, the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Exopolysaccharide Isolated from Poultry Origin Lactobacilli. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polansky, O.; Sekelova, Z.; Faldynova, M.; Sebkova, A.; Sisak, F.; Rychlik, I. Important Metabolic Pathways and Biological Processes Expressed by Chicken Cecal Microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikeocha, I.J.; Al-Kabsi, A.M.; Chiu, H.-T.; Alshawsh, M.A. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Ameliorates Colorectal Tumorigenesis and Suppresses Proliferation of HCT116 Colorectal Cancer Cells. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Siles, M.; Duncan, S.H.; Garcia-Gil, L.J.; Martinez-Medina, M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: From Microbiology to Diagnostics and Prognostics. ISME J. 2017, 11, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Yang, J.-Y.; Yan, Z.-H.; Hu, S.; Li, J.-Q.; Xu, Z.-X.; Jian, Y.-P. Recent Findings in Akkermansia Muciniphila-Regulated Metabolism and Its Role in Intestinal Diseases. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maue, A.C.; Mohawk, K.L.; Giles, D.K.; Poly, F.; Ewing, C.P.; Jiao, Y.; Lee, G.; Ma, Z.; Monteiro, M.A.; Hill, C.L.; et al. The Polysaccharide Capsule of Campylobacter jejuni Modulates the Host Immune Response. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkusa, T.; Yoshida, T.; Sato, N.; Watanabe, S.; Tajiri, H.; Okayasu, I. Commensal Bacteria Can Enter Colonic Epithelial Cells and Induce Proinflammatory Cytokine Secretion: A Possible Pathogenic Mechanism of Ulcerative Colitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Kang, M.S.; An, B.K.; Shin, E.G.; Kim, M.J.; Kwon, J.H.; Kwon, Y.K. Isolation and Epidemiological Characterization of Heat-Labile Enterotoxin-Producing Escherichia fergusonii from Healthy Chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 160, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, P.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: Intestinal Pathogenesis Mechanisms and Colonization Resistance by Gut Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2055943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Dorfman, R.G.; Liu, H.; Yu, T.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; Xu, L.; Yin, Y.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Produces Butyrate to Maintain Th17/Treg Balance and to Ameliorate Colorectal Colitis by Inhibiting Histone Deacetylase 1. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1926–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, X.; Hu, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Ni, Y. Comparison of the Effects of Feeding Compound Probiotics and Antibiotics on Growth Performance, Gut Microbiota, and Small Intestine Morphology in Yellow-Feather Broilers. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Song, L.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ren, Z. Genomic, Probiotic, and Functional Properties of Bacteroides dorei RX2020 Isolated from Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbuğa-Schön, T.; Suzuki, T.A.; Jakob, D.; Vu, D.L.; Waters, J.L.; Ley, R.E. The Keystone Gut Species Christensenella minuta Boosts Gut Microbial Biomass and Voluntary Physical Activity in Mice. mBio 2024, 15, e02836-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Dong, J.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Z.; Tan, X.; Li, H.; Sun, K.; Zhao, A.; Huang, M. Comparison of Fecal Microbiota and Metabolites in Diarrheal Piglets Pre-and Post-Weaning. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1613054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Hou, Y.; Lao, X. The Role of Akkermansia muciniphila in Disease Regulation. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, J.; Hao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Zeng, F.; Hu, J.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila Plays Critical Roles in Host Health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 49, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Cui, M.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Lu, A.; Qi, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, C.; et al. Microbiota-Derived Acetate Enhances Host Antiviral Response via NLRP3. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitetta, L.; Oldfield, D.; Sali, A. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Efficacy of Probiotics as Functional Foods. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2024, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakita, T.; Lee, K.; Morita, M.; Okuno, M.; Kyan, H.; Okano, S.; Maeshiro, N.; Ishizu, M.; Kudeken, T.; Taira, H.; et al. Isolation and Whole-genome Sequencing Analysis of Escherichia fergusonii Harboring a Heat-labile Enterotoxin Gene from Retail Chicken Meat in Okinawa, Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 68, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuno, M.; Tsuru, N.; Yoshino, S.; Gotoh, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Hayashi, T.; Ogura, Y. Isolation and Genomic Characterization of a Heat-Labile Enterotoxin 1-Producing Escherichia fergusonii Strain from a Human. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00491-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.W.; Lin, C.Y.; Wu, M.; Hsieh, C.; Yu, H.T. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals a Functional Signature for Biomass Degradation by Cecal Microbiota in the Leaf-Eating Flying Squirrel (Petaurista alborufus lena). BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.K.; Torok, V.A.; Percy, N.J. Microbial Fingerprinting Detects Unique Bacterial Communities in the Faecal Microbiota of Rats with Experimentally-Induced Colitis. J. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.; Yang, L.; Pei, Z. Gut Microbiota, Fusobacteria, and Colorectal Cancer. Diseases 2018, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, C.L. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis: A Rogue among Symbiotes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic Biomarker Discovery and Explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khleborodova, A.; Gamboa-Tuz, S.D.; Ramos, M.; Segata, N.; Waldron, L.; Oh, S. Lefser: Implementation of Metagenomic Biomarker Discovery Tool, LEfSe, in R. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.