Phytotherapeutic Approaches in Canine Pediatrics

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Use of Herbal Medicine in Puppies

2.1. Gastrointestinal Disorders

2.2. Respiratory Diseases

2.3. Dermatopathies

2.4. Miscellanea

2.5. Side Effects

- Class 1: Herbs that can be safely consumed when used appropriately (e.g., calendula, chamomile, echinacea, eyebright, hawthorn, lavender, lemon balm, nettle, peppermint, valerian, dandelion, and thistle);

- Class 2: Herbal plants which come with specific restrictions on use, as indicated by a qualified expert in the use of the substance. Subcategories include: 2a (for external use only), 2b (not recommended during pregnancy), 2c (not advised during lactation), and 2d (other specific use restrictions);

- Class 3: These herbs should only be used under the supervision of a qualified expert.

| Medicinal Plants (Scientific Name) | Adverse Reactions |

|---|---|

| Aconitum spp. | Salivation, nausea, emesis, cardiac arrhythmias |

| Allium sativum | Antiplatelet effect, hematologic disorders |

| Artemisia absinthum | Convulsions, trembling of the limbs, digestive disorders, thirst, paralysis, death |

| Digitalis spp. | Gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, weakness, muscle tremors, miosis, potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias |

| Echinacea spp. | Hepatotoxicity |

| Ephedra spp. or Ma Huang | Hyperactivity, tremors, seizures, behavior changes, vomiting, tachycardia, hyperthermia |

| Larrea tridentate | Hepatotoxicity |

| Juniperus sabina | Gastrointestinal and respiratory disorders, haemorrhages |

| Marshmallow root | Hypoglycemic effect |

| Mentha piperita | Hepatotoxicity |

| Rubus idaeus | Reproductive disorders |

- -

- Arnica montana (with a mild anticoagulant effect): when combined with NSAIDs (meloxicam, phenylbutazone, or acetylsalicylic acid), it can induce potentially fatal gastric or intestinal bleeding;

- -

- Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus): caution is advised to avoid concomitant use of aspirin and other NSAIDs;

- -

- Black currant (Ribes nigrum): it has an additive diuretic effect with other diuretic drugs.

- -

- Echinacea: not recommended in combination with acetaminophen as it increases the risk of liver toxicity;

- -

- Garlic (Allium sativum): it should be avoided simultaneously with anticoagulants;

- -

- Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.): it may present an additional risk of bleeding if given together with NSAIDs. It induces omeprazole hydroxylation;

- -

- Ginger (Zingiber officinale): it appears to have some benefit against motion sickness in dogs but reduces platelet aggregation through inhibition of thromboxane synthase. It may increase bleeding tendency if taken concurrently with aspirin or other NSAIDs;

- -

- Ginseng (Panax gingseng, P. quinquefolius): a possible interaction with imatinib has been reported;

- -

- Kava (Piper methysticum): in combination with acetaminophen, it can potentially increase the risk of hepatotoxicity. It also increases barbiturate-induced sleep time in laboratory animals and anticonvulsant effects in humans;

- -

- Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra): contains plant constituents that inhibit the renal activity of 11-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, thereby reducing the conversion of cortisol to cortisone, resulting in increased renal levels of cortisol available to bind to mineralocorticoid receptors. It also causes a reduction in salicylate concentration. It contains high levels of potassium that can cause sodium–potassium imbalance, leading to cardiac arrhythmias and hypertension. It is contraindicated in type I diabetes;

- -

- St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): it should not be used concomitantly with central nervous system antidepressants. It also seems that it can reduce the clearance and increase the plasma concentrations of a number of clinical drugs including cyclosporine, midazolam, methadone, imatinib, tacrolimus, digoxin, and theophylline;

- -

- Milk thistle (Sylibum marianum): it inhibits the metabolism of losartan and increases the clearance of metronidazole;

- -

- Valerian (Valeriana officinalis): it is expected to potentiate the sedative effects of opioids.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pesch, L. Holistic Pediatric Veterinary Medicine. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 2014, 44, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegi, L.; Pieroni, A.; Guarrera, P.M.; Vangelisti, R. A review of plants used in folk veterinary medicine in Italy as basis for a databank. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.A.; García-Barriuso, M.; Amich, F. Ethnoveterinary medicine in the Arribes del Duero, western Spain. Vet. Res. Commun. 2011, 35, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piluzza, G.; Bullitta, S. Correlations between phenolic content and antioxidant properties in twenty-four plant species of traditional ethnoveterinary use in the Mediterranean area. Pharma Biol. 2011, 49, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E.; de Pasquale, C.; Lenzarini, C.; Censorii, E.; Gonàlez-Tejero, M.R.; Sànchez-Rojas, C.P.; Ramiro-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Skoula, M.; Johnson, C.; et al. Circum-Mediterranean cultural heritage and medicinal plants uses in traditional animal healthcare: A field survey in eight selected areas within the RBIA project. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motti, R.; Ippolito, F.; Bonanomi, G. Folk Phytotherapy in Paediatric Health Care in Central and Southern Italy: A Review. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudato, M.; Capasso, R. Useful plants for animal therapy. OA Altern. Med. 2013, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, C.; Turner, N.; Brauer, G.; Khan, T. Medicinal plants used in British Columbia, Canada for reproductive health in pets. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 90, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgorlon, S.; Stefanon, B.; Sandri, M.; Colitti, M. Nutrigenomic activity of plant derived compounds in health and disease: Results of a dietary intervention study in dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 109, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romha, G.; Dejene, T.A.; Telila, L.B.; Bekele, D.F. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants: Preparation and application methods by traditional healers in selected districts of southern Ethiopia. Vet. World 2015, 8, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Long, C. An ethnoveterinary study on medicinal plants used by the Buyi people in Southwest Guizhou, Chine. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Rahman, I.U.; Calixto, E.S.; Ali, N.; Ijaz, F. Ethnoveterinary Therapeutic Practices and Conservation Status of the Medicinal Flora of Chamla Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henion, J.; Evans, S.; Wakshlag, J.J. Key quality control aspects about cannabinoid-rich hemp products that a veterinarian needs to know: A practitioner’s guide. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, A.; Mussarat, S.; Adnan, M.; AbdElsalam, N.M.; Ullah, R.; Khan, A.L. Ethnoveterinary study of medicinal plants in a tribal society of Sulaiman Range. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 127526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakare, A.G.; Shah, S.; Bautista-Jmenez, V.; Bhat, J.A.; Dayal, S.R.; Madzimure, J. Potential of ethno-veterinary medicine in animal health care practice in the South Pacific Island countries: A review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 2193–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musthaba, S.M.; Baboota, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ahuja, A.; Ali, J. Status of novel drug delivery technology for phytotherapeutics. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoshima, H.; Hirata, S.; Ayabe, S. Antioxidative and anti-hydrogen peroxide activities of various herbal teas. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Park, W. Zoonotic Diseases and Phytochemical Medicines for Microbial Infections in Veterinary Science: Current State and Future Perspective. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, A.; Ramoni, R.; Basini, G.; Bussolati, S.; Quintavalla, F. Oxidant–Antioxidant Status in Canine Multicentric Lymphoma and Primary Cutaneous Mastocytoma. Processes 2020, 8, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintavalla, F.; Basini, G.; Bussolati, S.; Carrozzo, G.G.; Inglese, A.; Ramoni, R. Redox status in canine Leishmaniasis. Animals 2021, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, B.; Susperregui, J.; Sahagún, A.M.; Diez, M.J.; Fernández, N.; García, J.J.; López, C.; Sierra, M.; Díez, R. Use of medicinal plants by veterinary practitioners in Spain: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1060738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardoni, S.; Pistelli, L.; Baronti, I.; Najar, B.; Pisseri, F.; Bandeira Reidel, R.V.; Papini, R.; Perrucci, S.; Mancianti, F. Traditional Mediterranean plants: Characterization and use of an essential oils mixture to treat Malassezia otitis externa in atopic dogs. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 1891–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompf, R.E. Nutritional and Herbal Therapies in the Treatment of Heart Disease in Cats and Dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2005, 41, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raditic, D.M. Complementary and integrative therapies for lower urinary tract diseases. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2015, 45, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickel, F.; Schuppan, D. Herbal medicine in the treatment of liver diseases. Dig. Liver Dis. 2007, 39, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkan, S. Comparison of the effects of an herbal mouthwash with chlorhexidine on surface bacterial counts of dental plaque in dogs. Biosci. Biotech. Res. Asia 2015, 12, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, C. Do recent research studies validate the medical plants used in British Columbia, Canada for pets diseases and wild animals taken into temporary care? J. Ehtnopharmacol. 2019, 236, 366–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardeccia, M.L.; Elam, L.H.; Deabold, K.A.; Miscioscia, E.L.; Huntingford, J.L. A pilot study examining a proprietary herbal blend for the treatment of canine osteoarthritis pain. Can. Vet. J. 2022, 63, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lans, C.; Turner, N.; Khan, T.; Brauer, G. Ethnoveterinary medicines used to treat endoparasites and stomach problems in pigs and pets in British Columbia, Canada. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 148, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves da Silva, E.M.; Silva Rodrigues, V.; Oliveira Jorge, J.; Fonseca Osava, C.; Szabò, M.P.J.; Garcia, M.V.; Andreotti, R. Efficacy of Tagetes minuta (Asteraceae) essential oil against Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) on infested dogs and in vitro. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2016, 70, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lans, C.; Harper, T.; Georges, K.; Bridgewater, E. Medicinal plants used for dogs in Trinidad and Tobago. J. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 45, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Nath, I.; Senapati, S.B.; Panda, S.K.; Das, M.R.; Patra, B.K. Comparative Evaluation of Nutraceuticals (Curcuma longa L., Syzygium aromaticum L. and Olea europaea) with Single-agent Carboplatin in the Management of Canine Appendicular Osteosarcoma. Indian. J. Anim. Res. 2022, 56, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, V.; Calzuola, I.; Gianfranceschi, G.L. Nutritional relevance of wheat sprouts containing high levels of organic phosphates and antioxidant compounds. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2004, 38, S123–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erarslan, Z.B.; Kultur, S. Ethnoveterinary medicine in Turkey: A comprehensive review. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2019, 43, 555–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, S. Effectiveness of treatments for firework fears in dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Santos, N.; Beck, A.; Maenhoudt, C.; Billy, C.; Fontbonne, A. Profile odf dogs’ breeders and their consideration on female reproduction, maternal care and peripartum stress—An International Survey. Animals 2021, 11, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, K.A. Barking up the same tree: A comparison of ethnomedicine and canine ethnoveterinary medicine among the Aguaruna. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.C.; Alarcòn, R. Hunting and hallucinogens: The use psychoactive and other plants to improve the hunting ability of dogs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 171, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, L.A.; Kaplan-Zattler, A.J.; Lee, J.A. Fluid Therapy for Pediatric Patients. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 2022, 52, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K.H.N.P.; Fuchs, K.d.M.; Corrêa, J.V.; Chiacchio, S.B.; Lourenço, M.L.G. Neonatology: Topics on Puppies and Kittens Neonatal Management to Improve Neonatal Outcome. Animals 2022, 12, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, D.F. Neonatal and pediatric care of the puppy and kitten. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintavalla, F.; Filipponi, G.; Pozza, O.; Belloli, A. La sindrome del cucciolo nuotatore. Veterinaria 1998, 12, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Macintire, D.K. Pediatric intensive care. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 1999, 29, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldrick, P. Juvenile animal testing in drug development—Is it useful? Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 2010, 57, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor, H.K. Influence of Food on Paediatric Gastrointestinal Drug Absorption Following Oral Administration: A Review. Children 2015, 2, 244–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal-Kluever, A.; Fisher, J.; Grylack, L.; Kakiuchi-Kiyota, S.; Halpern, W. Physiology of the Neonatal Gastrointestinal System Relevant to the Disposition of Orally Administered Medications. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueters, R.; Bael, A.; Gasthuys, E.; Chen, C.; Schreuder, M.F.; Frazier, K.S. Ontogeny and Cross-species Comparison of Pathways Involved in Drug Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion in Neonates (Review): Kidney. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2020, 48, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papich, M.G.; Martinez, M.N. Applying Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) Criteria to Predict Oral Absorption of Drugs in Dogs: Challenges and Pitfalls. AAPS J. 2015, 17, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaissaire, J.P. Le Chien Animal da Laboratoire; Vigot Freres: Paris, France, 1972; pp. 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.P.; Stambouli, F.; Martin, L.J.; Dumon, H.J.; Biourge, V.C.; Nguyen, P.G. Influence of age and body size on gastrointestinal transit time of radiopaque markers in healthy dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2002, 63, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbitts, J. Issues related to the use of canines in toxicologic pathology—Issues with pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Toxicol. Pathol. 2003, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Casal, M. Chapter 15. Management and critical care of the neonate. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Reproduction and Neonatology; England, G.C.W., von Heimendahl, A., Eds.; British Small Animal Veterinary Association: Gloucester, UK, 2010; pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya Navarrete, A.L.; Quezada Tristán, T.; Lozano Santillán, S.; Ortiz Martínez, R.; Valdivia Flores, A.G.; Martínez Martínez, L.; De Luna López, M.C. Effect of age, sex, and body size on the blood biochemistry and physiological constants of dogs from 4 wk. to >52 wk. of age. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poffenbarger, E.M.; Ralston, S.L.; Chandler, M.L.; Olson, P.N. Canine neonatology. Part 1. Physiologic differences between puppies and adults. Compend. Contin. Educ. Pract. Vet. 1990, 12, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Trepanier, L.A. Applying pharmacokinetics to veterinary clinical practice. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 2013, 43, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, R. Drug disposition in the newborn. In Proceedings of the Pharmacologie et Toxicologie Vétérinaires, 2e Congrés Européen Toulouse, Toulouse, France, 13–17 September 1982; INRA Publ: Paris, France, 1982; pp. 455–458. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, N.; Crescioli, G.; Bettiol, A.; Menniti-Ippolito, F.; Maggini, V.; Gallo, E.; Mugelli, A.; Vannacci, A.; Firenzuoli, F. Safety of complementary and alternative medicine in children: A 16-years retrospective analysis of the Italian Phytovigilance system database. Phytomedicine 2019, 61, 152856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Patra, R.C.; Nandi, S.; Swarup, D. Oxidative stress indices in gastroenteritis in dogs with canine parvoviral infection. Res. Vet. Sci. 2009, 86, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanavicius, C.J.; Powell, K.L.; Vester, B.M.; Karr-Lilienthal, L.K.; Pope, L.L.; Fastinger, N.D.; Wallig, M.A.; Tappenden, K.A.; Swanson, K.S. Fructan Supplementation and Infection Affect Food Intake, Fever, and Epithelial Sloughing from Salmonella Challenge in Weanling Puppies. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1923–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chetan, G.E.; De, U.K.; Singh, M.K.; Chander, V.; Raja, R.; Paul, B.R.; Choudhary, O.P.; Thakur, N.; Sarma, K.; Prasasd, H. Antioxidant supplementation during treatment of outpatient dogs with parvovirus enteritis ameliorates oxidative stress and attenuates intestinal injury: A randomized controlled trial. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2023, 21, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, O.W. Análise In Vitro da Atividade Antiviral de Óleos Essenciais Sobre o Parvovírus Canino- Tipo 2. Thesis, Programa de PósGraduação em Biotecnologia, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, Brasil 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.ucs.br/11338/6815 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Meineri, G.; Martello, E.; Radice, E.; Bruni, N.; Saettone, V.; Atuahene, D.; Armandi, A.; Testa, G.; Ribaldone, D.G. Chronic Intestinal Disorders in Humans and Pets: Current Management and the Potential of Nutraceutical Antioxidants as Alternatives. Animals 2022, 12, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xaxa, L.S.; Kumar, P. Efficacy of Centella asiatica (Beng Saag) on hemato-biochemical and oxidative stress due to gastro enteritis in pups. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2020, SP-8, 49–54. Available online: http://www.entomoljournal.com/ (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Campigotto, G.; Alba, D.F.; Sulzbach, M.M.; Dos Santos, D.S.; Souza, C.F.; Baldissera, M.D.; Gundel, S.; Ourique, A.F.; Zimmer, F.; Petrolli, T.G.; et al. Dog food production using curcumin as antioxidant: Effects of intake on animal growth, health and feed conservation. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 74, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, R.; Jami, S.I.; Alam, E.K.; Alam, B. Antidiarrheal Activity of Lannea coromandelica Linn. Bark Extract. Am. Eurasian J. Sci. Res. 2013, 8, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Szweda, M.; Szarek, J.; Dublan, K.; Męcik-Kronenberg, T.; Kiełbowicz, Z.; Bigoszewski, M. Effect of mucoprotective plant-derived therapies on damage to colonic mucosa caused by carprofen and robenacoxib administered to healthy dogs for 21 days. Vet. Q. 2014, 34, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Benavides, J.R.; Ruano, A.L.; Silva-Rivas, R.; Castillo-Veintimilla, P.; Vivanco-Jaramillo, S.; Bailon-Moscoso, N. Medicinal plants used as anthelmintics: Ethnomedical, pharmacological, and phytochemical studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, L.H.; Basiouny, S.O.; Dawoud, H.A. Treatment of experimental heterophyiasis with two plant extracts, areca nut and pumpkin seed. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2002, 32, 501–506, 1 p following 506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Day, M.J.; Carey, S.; Clercx, C.; Kohnx, B.; MarsilIo, F.; Thiry, E.; Freyburger, L.; Schulz, B.; Walker, D.J. Aetiology of Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex and Prevalence of its Pathogens in Europe. J. Comp. Pathol. 2020, 176, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichling, J.; Fitzi, J.; Fürst-Jucker, J.; Bucher, S.; Saller, R. Echinacea powder: Treatment for canine chronic and seasonal upper respiratory tract infections. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilk 2003, 145, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresch, M.; Mevissen, M.; Ayrle, H.; Melzig, M.; Roosje, P.; Walkenhorst, M. Medicinal plants as therapeutic options for topical treatment in canine dermatology? A systematic review. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.; Autore, G.; Severino, L. Pharmaco-toxicological aspects of herbal drugs used in domestic animals. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, P.; Gupta, A.R.; Jena, D.; Patra, R.C. Therapeutic management of juvenile demodicosis with herbal preparation in a puppy—A case report. Intern. J. Livest. Res. 1964, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.S. Effect of a herbal compound for treatment of sarcoptic mange infestations on dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 1996, 63, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michál’ová, A.; Takáčová, M.; Karasová, M.; Kunay, L.; Grelová, S.; Fialkovičová, M. Comparative Study of Classical and Alternative Therapy in Dogs with Allergies. Animals 2022, 12, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, N.; El-Banna, R.; Arafa, M.M.; Hady, M.M. Hypoglycemic efficacy of Rosmarinus officinalis and/or Ocimum basilicum leaves power as a promising clinic-nutritional management tool for diabetes mellitus in Rottweiler dogs. Vet. World 2020, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahandeh, G.; Khoshdel, A.; Sedehi, M.; Aliakbari, A. Phytotherapy with Hordeum Vulgare: A Randomized Controlled Trial on Infants with Jaundice. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, SC16–SC19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Ahmed, F.; Cayer, C.; Mullally, M.; Carballo, A.F.; Otarola Rojas, M.; Garcia, M.; Baker, J.; Masic, A.; Sanchez, P.E.; et al. New Botanical Anxiolytics for Use in Companion Animals and Humans. AAPS J. 2017, 19, 1626–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, D.L. Aromatherapy for travel-induced excitement in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2006, 229, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsato Alvarenga, I.; MacQuiddy, B.; Duerr, F.; Elam, L.H.; McGrath, S. Assessment of cannabidiol use in pets according to a national survey in the USA. JSAP 2023, 64, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemer, S. Therapy and Prevention of Noise Fears in Dogs—A Review of the Current Evidence for Practitioners. Animals 2023, 13, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Girard, D.; Gerstenberg, G.; Stoffel, L.; Kohler, T.; Klein, S.D.; Eschenmoser, M.; Mitter, V.R.; Nelle, M.; Wolf, U. Euphrasia Eye Drops in Preterm Neonates with Ocular Discharge: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, S.; Di Ianni, F.; Di Girolamo, N.; Canello, S.; Gnudi, G.; Guidetti, G.; Miduri, F.; Fabbi, M.; Daga, E.; Parmigiani, E.; et al. Effect of a commercially available fish-based dog food enriched with nutraceuticals on hip and elbow dysplasia in growing Labrador retrievers. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 82, 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, A.; Mishra, S.; Singh, N.; Pathak, R.; Sonkar, N.; Kashyap, A.; Das, S. Role of nutraceuticals in pet animals. Biot. Res. Today 2021, 3, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Z.; McGuffin, M. American Herbal Products Association’s. Botanical Safety Handbook, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. xxii–xxiii. ISBN 978-4665-1694-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms, T.G.; Khan, S.A.; Means, C. Suspected caffeine and ephedrine toxicosis resulting from ingestion of an herbal supplement containing guarana and ma huang in dogs: 47 cases (1997–1999). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.G.; McLean, M.K.; Khan, S.A. Adverse reactions from essential oil-containing natural flea products exempted from Environmental Protection Agency regulations in dogs and cats. JVECC 2012, 22, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppenga, R.H. Herbal Medicine: Potential for intoxication and interactions with conventional drugs. Clin. Tech. Small Anim. Pract. 2002, 17, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byard, R.W.; Musgrave, I. The potential side effects of herbal preparations in domestic animals. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2021, 17, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, W. Herbal medication: Potential for adverse interactions with analgesic drugs. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002, 27, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, M.T.; Langler, A.; Osterman, T. Systematic review on phytotherapy in neonatology. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2011, 18, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H.; De Filippis, A.; Baldi, A.; Dacrema, M.; Esposito, C.; Garzarella, E.U.; Santarcangelo, C.; Tantipongpiradet, A.; Daglia, M. Beneficial Effects of Plant Extracts and Bioactive Food Components in Childhood Supplementation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartges, J.; Boynton, B.; Vogt, A.H.; Krauter, E.; Lambrecht, K.; Svec, R.; Thompson, S. AAHA Canine Life Stage Guidelines. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2012, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.C.; Srivastava, A.; Lall, R. (Eds.) Nutraceuticals in Veterinary Medicine; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. vii–ix. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, K. Assessing pet supplements. Use widespread in dogs and cats, evidence and regulation lacking. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 250, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

| PLANT | MOLECULES |

|---|---|

| Aesculus hippocastanum | Escin |

| Ananas sativus | Bromelain |

| Artemisia annua | Artemisinin |

| Atropa belladonna | Atropine, Hyoscine methylbromide (hemisynthesis) |

| Camellia sinensis | Theophylline |

| Cannabis sativa | Cannabidiol |

| Catharanthus roseus | Vincristine, Vinblastine, Videsine, and Vinorelbine (hemisynthesis) |

| Chinchona officinalis | Quinidine |

| Claviceps purpurea | Ergotamine, Ergotoxine, Nicergoline (hemisynthesis), Bromocriptine (hemisynthesis) |

| Digitalis lanata and D. purpurea | Digoxin, Digitoxin, and Methyldigoxin |

| Juniperus communis | Teniposide and etoposide |

| Mappia foetida Miers. | Comptothecin analogs |

| Papaver somniferum | Morphine, Papaverine, Codeine, and Buprenorphine |

| Pausinystalia yohimbe | Yohimbine |

| Pilocarpus jaborandi | Pilocarpine |

| Podophyllum emodi Wall. | Podophyllotoxin |

| Rauwolfia serpentina | Ajmaline and Reserpine |

| Taxus brevifolia | Paclitaxel and Taxotere (hemysinthesis) |

| Vinca minor | Vincamine |

| Infectious Diseases | Non-Infectious Diseases |

|---|---|

| Bacterial infections Local infection (e.g., skin, eyes, umbilicus) General bacterial infection Sepsis/septicemia Viral infections Canine adenovirus 2 Canine herpesvirus Distemper virus Kennel cough complex Canine viral enteritis (parvovirus, coronavirus, rotavirus, etc.) Parasites Protozoa (Giardia, Coccidia) Roundworm, hookworm | Genetic diseases Hemorrhage (vit. K deficiency) Juvenile hypoglycemia, dehydratation Hypothermia Juvenile cellulitis Impetigo Malformations, defects (e.g., swimmer puppy syndrome) Non-infectious diarrhoea Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) Toxic milk syndrome Fading puppy syndrome Traumatic insults/injuries Foreign body ingestion or electrical cord injury Fatty liver syndrome Passive immunity transfer failure |

| Gastric pH | Acid secretion from the stomach is delayed for several days after birth. In puppies, compared to adult dogs, gastric pH is less acidic. |

| Gastric Emptying (closely related to the physical characteristics of the ingested food) | Antral contractions in puppies increase from 0.2 contractions per minute on the day of birth to a peak of 2.3 contractions per minute on the 11th day, after which they gradually decline. Gastric emptying plays a crucial role in determining the initiation of drug absorption, as it represents a rate-limiting step preceding the exposure of drugs to the absorptive membrane of the small intestine. Gastric emptying can exhibit significant variations during growth, and studies assessing gastric emptying using radiopaque markers in dogs have not revealed any significant differences between males and females. |

| Bile Secretion (0.5 mL/kg/h) | It progressively develops, thereby restricting the absorption of fat-soluble substances. |

| Splanchnic Blood Flow | Food intake induces an increased splanchnic blood flow, which in turn will increase the absorption and transfer of nutrients into the bloodstream. |

| Gastrointestinal Transit Times | Puppies exhibited a shorter mean T50 compared to adults. Age did not significantly affect the mean small intestinal transit time in any breed, and the mean orocecal transit time decreased significantly only during the growth of large-breed dogs. Intestinal blood supply is lower in puppies. Food intake can influence the disintegration of formulations and drug dissolution in the GI tract. The impact of food on drug absorption depends on the dosage form’s nature, the excipients utilized in the formulation, and the particle size of the drug in the formulation. This is especially relevant in younger patients, where feeding occurs more frequently than in adults. Conspicuous jejunal lymph nodes and a mild amount of anechoic peritoneal fluid were considered normal. |

| Membrane Interactions | Immediately after birth, the special epithelium starts to disappear essentially gone after 24 h. Nevertheless, during the first 2 days of life, systemic effects may occur following oral administration of drugs that are not normally absorbed from the intestine. Drug absorption in pediatric patients involves transporters and enzymes that may not be fully mature. High viscosity within the intestinal lumen can slow down the diffusion rate of a drug, leading to reduced overall absorption. |

| Intestinal Microbial Flora | The gut microbiome of dogs is more like that of humans than that of mice and pigs. During weaning, puppies’ gut microbiota gradually becomes more similar to that of adult dogs due to the transition from milk to solid food, influenced by both dietary and behavioral factors. This microbiome development can have consequences on enteric metabolism and the intestinal wall. The predominant phyla in feces of puppies, pregnant, and lactating bitches are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria, and Actinobacteria. Various factors, including breed, age, living conditions, diet, and methodology, can contribute to this variability. Older age was associated with a lower proportion of Fusobacteria. |

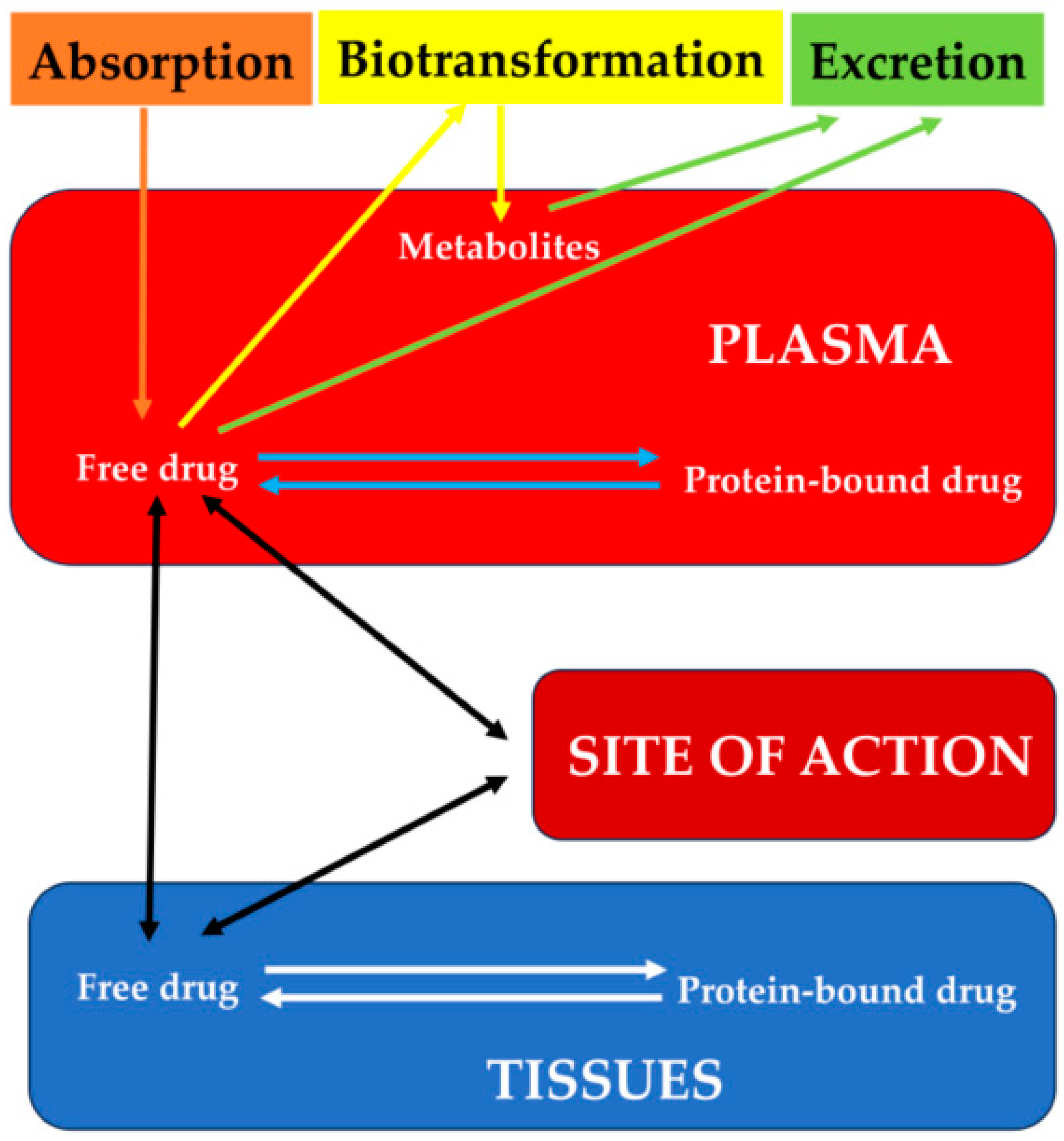

| Liver | Immaturity of the liver results in reduced drug clearance in puppies. The hepatic microsomal pathways associated with drug metabolism develop rapidly during the first 3 to 4 weeks after birth, and by 8 to 12 weeks, they approach activity levels similar to those in adult animals. The in vitro activities of enzymes like P-450, glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P), and UDP-glucuronyl transferase (GT) are immature at birth and develop gradually during postnatal life. Because phase I (oxidation) and phase II (glucuronidation) hepatic enzyme systems are not fully functional in puppies, drugs that require hepatic metabolism for excretion tend to reach higher plasma levels. Conversely, drugs that rely on hepatic metabolism for activation have lower plasma concentrations. Additionally, oral drugs subject to first-pass metabolism are at risk of accumulating to toxic levels in plasma if administered at the adult dose. The immaturity of the liver can exacerbate many coagulopathies during the pre-pubescent period. |

| Kidney (renal blood flow: 440 mL/min/m2) | Renal function in puppies appears to mature within the first 4 to 6 weeks of life. The volume of nephron segments continues to grow from postnatal week 2, when nephrogenesis ceases, to approximately postnatal week 28, resulting in an enlargement of up to 300%. This maturation process leads to a reduced renal clearance of water-soluble drugs, primarily due to the low glomerular filtration rate and renal blood flow in neonates, and later, a reduced renal excretion caused by immature renal tubules. Incomplete tubular absorption is responsible for glucosuria in puppies younger than 8 weeks of age. During the first 8 weeks, urine-specific gravity varies from 1.006 to 1.017. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quintavalla, F. Phytotherapeutic Approaches in Canine Pediatrics. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci11030133

Quintavalla F. Phytotherapeutic Approaches in Canine Pediatrics. Veterinary Sciences. 2024; 11(3):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci11030133

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuintavalla, Fausto. 2024. "Phytotherapeutic Approaches in Canine Pediatrics" Veterinary Sciences 11, no. 3: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci11030133

APA StyleQuintavalla, F. (2024). Phytotherapeutic Approaches in Canine Pediatrics. Veterinary Sciences, 11(3), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci11030133