Abstract

This study investigates the impact of wood origin and the geometry of barrel alternatives on the extraction of volatile compounds and total ellagitannins during the aging of tsipouro, a traditional Greek spirit. French, American, and Greek oak, along with Greek chestnut, were used in the form of veneers, sticks, and particles to simulate aging conditions. Volatile compounds were analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, while ellagitannin levels were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection after acidic hydrolysis. A total of nine volatile compounds were identified, with significant differences (p < 0.05) observed based on wood type and fragment dimensions. French oak exhibited higher concentrations of vanillin, syringaldehyde, sinapaldehyde, and coniferaldehyde, while Greek chestnut showed notably lower levels of these compounds. However, chestnut wood yielded the highest ellagitannin concentrations (up to 17.84 mg/L), whereas Greek oak exhibited the lowest (0.20–0.60 mg/L). Veneers (wood sheets) were generally more efficient than sticks or particles in compound extraction. These findings indicate that both the botanical origin and physical dimensions of wood fragments play a crucial role in shaping the chemical profile of aged spirits. Furthermore, the results highlight the potential of Greek woods as sustainable, economically beneficial alternatives in modern aging practices.

1. Introduction

Tsipouro is a traditional Greek spirit, distilled from grape marc and recognized as a national product. It is similar to other beverages such as grappa, marc, orujo, zivania, etc. As outlined in European Commission’s regulation (EC) 2019/787, the initial distillation process occurs in the presence of the grape marc itself, following strict procedural guidelines [1]. The regulation sets a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 37.5% v/v for grape marc spirits, ensuring compliance with established standards [2,3].

Beyond its technical definition, tsipouro carries a deep cultural and linguistic heritage. The term is believed to derive from the ancient Greek oxyporion (“sharp or fiery drink”), recorded in the Athonite monastic tradition to describe early distilled beverages [4]. This etymology highlights the historical continuity of Greek distillation, linking ancient medicinal and monastic practices with modern artisanal production.

Distillation in Greece has a deep-rooted history, with Aristotle discussing its fundamental principles as early as the 4th century BC. Furthermore, during the Byzantine era, skilled coppersmiths from the mountainous Agrafa region of Thessaly migrated to major cities such as Thessaloniki and Constantinople, contributing to the development of distillation equipment and techniques. Despite Greece’s long tradition of distillation and its abundant high-quality raw materials, tsipouro remained an unstandardized, bulk-produced beverage primarily for individual and family use until the late 20th century, when organized distilleries began commercial bottling [5]. Although tsipouro production remains relatively small—accounting for approximately 7% of Greek alcoholic beverage production—its popularity continues to rise [6].

Various factors contribute significantly to the chemical and sensory characteristics of the product. These encompass the choice of the grape variety, climatic conditions, viticultural practices, conditions during fermentation, the distillation process and, if applicable, the aging process of the distillate in wooden barrels [7].

Wood plays a crucial role in the traditional production and aging of tsipouro, referred to as “aged tsipouro”. While the initial distillation typically involves copper stills, the maturation process often relies on wooden barrels, especially oak, which significantly enhances the character of the spirit. The use of oak contributes to the development of complex aromas, smoother taste, and a rich amber color, particularly in aged varieties [8]. Natural wood compounds such as tannins, vanillin, and lignin derivatives interact with the distillate over time, imparting notes of spice, vanilla, and dried fruit [9,10]. Additionally, the porosity of wood allows for controlled oxidation, leading to further refinement of the flavor profile [11]. Scientific studies on other wood-aged spirits like whisky and wine also confirm that extractives from oak staves significantly influence aroma and chemical balance [12]. In the context of Greek distillation traditions, wood is not only a material for aging but also a symbol of authenticity and craftsmanship [8,13]. Thus, wood aging supports both quality enhancement and the preservation of cultural identity in tsipouro production.

In recent years, an innovative and cost-effective alternative to traditional barrel aging of wines and alcoholic beverages has gained prominence: the use of oak chips, toasted staves, cubes, and other wood fragments. These wood alternatives, derived from the same species used in cooperage (typically Quercus robur, Quercus alba, or Quercus petraea), are prepared through established thermal modification techniques, including toasting at different temperatures and durations to release specific aromatic and structural compounds [14,15,16,17].

Compared to traditional wooden barrels, these wood fragments have a much larger surface-area-to-volume ratio, which leads to a faster and often more intense extraction of both volatile compounds—such as vanillin, eugenol, furfural, and lactones—and non-volatile components such as tannins and ellagitannins [8,18,19]. These compounds contribute directly to the organoleptic characteristics of the aged product, affecting its aroma, flavor, mouthfeel, and color. Several studies have found that the chemical profile and sensory outcomes of beverages aged with toasted oak chips can be comparable to those aged in barrels, especially when chips are used in combination with micro-oxygenation techniques [20,21].

Moreover, aging with wood fragments allows greater control over flavor development, as producers can vary chip size, toasting degree, contact time, and wood origin. It is also considered more economically viable and sustainable, as it reduces the need for new barrels and allows for partial or small-batch aging [22].

This method is particularly useful in the tsipouro industry, where smaller producers may seek affordable ways to introduce wood-aged profiles into their products without investing in full barrels. However, the choice between chips and barrels may ultimately depend on the desired complexity, market positioning, and authenticity goals of the producer.

Indeed, within the European winemaking context, the use of oak fragments in the maceration of grapes has arisen as a substitute for the conventional approach of aging in oak barrels. This practice is officially authorized and governed by European Union (EU) regulations (EC) No 2165/2005 [23] and (EC) No 1507/2006 [24], which outline specific guidelines for the incorporation of oak fragments in the winemaking process. These regulations marked a significant shift, permitting European producers to participate in the global market.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the influence of varying wood fragment dimensions—particles, sticks, and veneers—originating from different wood types, namely American oak (AO), French oak (FO), Greek oak (GO), and Greek chestnut (GC), on the aging process of tsipouro. While prior studies have extensively investigated the effects of oak chips on a range of beverages such as ciders, wines, and beers, the present study addresses a notable gap in understanding the influence of diverse wood fragment sizes on tsipouro maturation. To achieve this goal, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was employed to analyze volatile compounds in tsipouro, and a high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD) was used to determine ellagic tannins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tsipouro Samples

The tsipouro samples (40% v/v) employed in this study are described in detail by Karathanos et al. [8]. In brief, they were obtained through the fermentation and subsequent distillation of grape pomace from the Mavro Moscato (Black Muscat) grapevine variety, cultivated organically at the foothills of the Agrafa Μountains in the region of Karditsa, Thessaly, Greece.

2.2. Wooden Fragments

The wooden fragments used in the survey originated from four distinct botanical species: French oak (FO) (Quercus petraia), American oak (AO) (Quercus alba), Greek oak (GO) (Quercus trojana or Quercus macedonica), and Greek chestnut (GC) (Castanea sativa). The first two types (French and American oak) were generously provided by Tonellerie Nadalie in Bordeaux, France, in the form of sizable staves. The latter two, acquired in the form of tree logs, were sourced from the Department of Forestry, Wood Sciences, and Design (DFWSD) at the University of Thessaly in Karditsa, Greece. The processes of seasoning, toasting, and cutting the woods into small pieces- fragments with dimensions of 2.0 × 2.0 × 1.0 cm (particles; 25 pieces), 20.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 cm (sticks; 5 pieces), and 20.0 × 5.0 × 0.2 cm (veneers; 2 pieces) were carried out at the laboratories of DFWSD, as shown in Figure 1. The Greek oak tree was obtained from an oak forest in Macedonia, Greece, and its harvesting was conducted with the permission of the Forestry Office of Kozani, Western Macedonia, Greece, specifically for this research endeavor.

Figure 1.

Wood fragments were prepared in three different forms based on size and geometry: (a) veneers, (b) particles, and (c) sticks.

2.3. Toasting

The toasting technique was performed according to a previously published method by the research group [8]. Briefly, a two-stage toasting process was applied: the first stage at 160 °C for 6 h, followed by a second stage at 200 °C for 8 h, using a drying and heating chamber (Binder GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) (Figure 2). The wood fragments were weighed before and after toasting. These pieces were then placed in 4 L glass containers with tsipouro for 3 years, providing a total wood–liquid contact surface of approximately 400–420 cm2, equivalent to ~100–105 cm2/L. This corresponds to a surface-to-volume (S/V) ratio of ≈2.0 m2/225 L, reproducing realistic contact conditions of barrel aging on a laboratory scale, as reported in the previous literature [20]. Small dimensional variations (<5%) may occur due to manual cutting and natural heterogeneity of the wood, but they do not affect the targeted S/V equivalence among treatments.

Figure 2.

Toasting process.

2.4. Determination of Volatile Compounds in Aged Tsipouro by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

Volatile components were extracted using liquid–liquid extraction with dichloromethane as the solvent, following an adapted protocol originally designed for wine sample analysis [25]. The analysis of volatile compounds using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) was conducted by the Agilent Technologies 7890A GC System (Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with the Agilent Technologies 5975C VL MSD with Triple-Axis Detector (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The system was equipped with a capillary column HP-5MS (5%-Phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), dimensions 30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm. Helium gas was utilized as the carrier gas, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection volume was set at 1 μL. The program initiated with an inlet temperature of 220 °C. The temperature profile commenced at 40 °C for 3 min, followed by a ramp of 3 °C/min up to 160 °C, and then a steep increase of 10 °C/min until reaching 240 °C, where it was held for 10 min.

Chromatograms, conducted through Full Scan, were processed using the Chemstation G1701DA D.01.00 integrated software (Agilent Technologies) and quantification was performed with respect to the internal standard (3-octanol).

2.5. Determination of Total Ellagitannin Concentration in Aged Tsipouro by High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Diode Array Detector (HPLC-DAD) Analysis

Aged tsipouro (40 mL) was subjected to vacuum evaporation using a rotary evaporator (Büchi AG, Flawil, Switzerland) at 50 °C until complete dryness. The resulting residue was re-dissolved in a small quantity of methanol (MeOH) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and transferred to a 20 mL volumetric flask. The flask was then filled to volume with MeOH, and the suspension was subjected to ultrasonic treatment in an ultrasonic bath (EMAG Emmi-20 HC, EMAG GmbH, Salach, Germany) for 10 min to ensure thorough homogenization.

Acid hydrolysis of aged tsipouro samples was carried out using a modified protocol originally developed for wine sample analysis [26]. Control samples (without hydrolysis) and treated samples (with hydrolysis) were prepared for comparison.

For the control, 2 mL of the suspension was transferred to a 5 mL volumetric flask, and the volume was adjusted with MeOH. For the hydrolysis samples, two Pyrex tubes with Teflon caps were each filled with 4 mL of the suspension and 1 mL of concentrated HCl (37%) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The tubes were placed in a water bath maintained at 100 °C for 2 h to facilitate hydrolysis. Following the reaction period, the tubes were allowed to cool to room temperature. The contents of each tube were subsequently transferred to separate 10 mL volumetric flasks, and the volume was adjusted with MeOH. All samples, including the control, were filtered through RC filters (pore size 0.2 μm, diameter 15mm) purchased from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA) to remove particulates and ensure sample purity. The filtered solutions were then transferred to HPLC vials for further analysis.

Simultaneously, standard solutions and calibration curves were also prepared for gallic acid, vescalagin, castalagin, catechin, vanillic acid, syringic acid, syringaldehyde, p-coumaric acid, coniferaldehyde, naringenin, and ellagic acid at concentrations ranging from 2 to 100 ppm. The total ellagitannin concentration was estimated by measuring the amount of ellagic acid released through acidic hydrolysis. This process involved the release of one molecule of ellagic acid from each ellagitannin monomer or dimer. The total ellagitannin concentration was expressed as mg/L of free ellagic acid released.

An HPLC system from Jasco (Tokyo, Japan) was employed for the analysis. The system consisted of a PU-2089 plus pump, a Rheodyne model 7725i injection valve with an integrated 20 μL loop, and a diode array detector (DAD; Jasco MD-910). The chromatographic separations were performed using a Nucleosil 100-5 C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μm particle size) (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany).Two solvents were utilized for the analysis. Solvent A consisted of 0.1% v/v H3PO4 in HPLC-grade water, while solvent B was 0.1% v/v H3PO4 in HPLC-grade MeOH. A solvent flow rate of 1 mL/min was applied under the following elution program: from 0 to 70 min, 100% solvent A; from 70 to 72 min, 100% solvent B; and from 72 to 73 min, 100% solvent A.

The injection volume for each sample was 40 μL, and the column temperature was maintained at a constant 25 °C throughout the analysis. Detection was performed over a wavelength range of 210–320 nm, with chromatograms extracted at 280 nm.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The mean and standard deviation (S.D.) were calculated from three replicates. Data were subsequently analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19.0; Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Volatile Compounds

The current study focuses on the determination of volatile compounds as well as on the total concentration of ellagic tannins extracted from diverse wood types and geometric configurations added in tsipouro during its aging process.

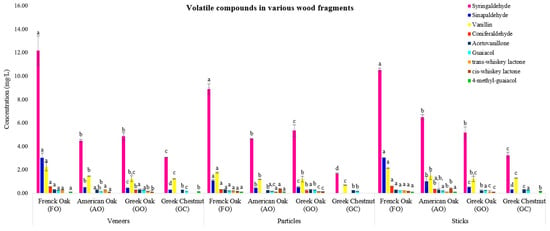

Figure 3 and Table 1 illustrate the identification of nine volatile compounds in the samples, each contributing distinct sensory characteristics. These compounds include acetovanillone (vanilla aroma note), cis-whiskey lactone (coconut-like, woody, and vanilla), coniferaldehyde, guaiacol (smoky and sweet), 4-methyl-guaiacol (roast and spicy), sinapaldehyde, syringaldehyde (vanilla), trans-whiskey lactone (coconut-like, woody, and vanilla), and vanillin (vanilla). Nevertheless, notable statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed among the samples due to the origin and the dimension of the wood fragments. These findings indicate that the type and structure of the wood material play a decisive role in modulating the extraction of aroma-active compounds, ultimately shaping the sensory expression of the distillate.

Figure 3.

Volatile compounds in aged tsipouro after contact with different wood fragment types (veneers, particles, sticks) from four wood origins (French oak (FO), American oak (AO), Greek oak (GO), Greek chestnut (GC)). Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Different Latin letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) for the same compound among wood origins within the same fragment type.

Table 1.

Volatile compounds in aged tsipouro after contact with different wood fragment types (veneers, particles, sticks) from four wood origins (French oak (FO), American oak (AO), Greek oak (GO), Greek chestnut (GC)).

In agreement with these compositional differences, the aromatic profile of aged tsipouro, as previously reported by our research group [8], is characterized by high aromatic intensity and balance. The bouquet combines floral, citrus, dried fruit, and sweet notes (vanilla, honey, caramel) with wood- and spice-derived attributes, resulting in a complex yet harmonious olfactory profile. This composition reflects the successful integration of volatile compounds originating from both the distillate and the wood, defining the distinctive typicity and sensory character of aged tsipouro.

Among the examined oak wood origins—French, American, and Greek—French oak exhibited higher concentrations of vanillin, sinapaldehyde, syringaldehyde, and coniferaldehyde compared to Greek and American oak, which yielded more similar results, as determined by GC-MS analysis. Syringaldehyde, vanillin, and sinapaldehyde were identified as the predominant compounds across all oak samples, with syringaldehyde displaying the highest concentration, ranging from 4.48 to 12.18 mg/L, regardless of wood shape or origin. In contrast, vanillin and sinapaldehyde were present at lower concentrations, ranging from 1.16 to 2.14 mg/L and 0.42 to 3.00 mg/L, respectively (Figure 3).

However, when comparing the studied samples from oak wood with those from chestnut, significantly lower concentrations of syringaldehyde, vanillin, and sinapaldehyde were observed in chestnut samples. Furthermore, in the case of particles in chestnut wood, sinapaldehyde was not detected at all. On the other hand, acetovanillone and guaiacol were detected in all samples, albeit at low concentrations, ranging from 0.22 to 0.30 mg/L and 0.11 to 0.24 mg/L, respectively (Figure 3).

Our results indicate significantly higher syringaldehyde concentrations compared to those reported by Rodriguez-Bencomo et al. [27], who observed levels ranging from 1.45 to 3.18 mg/L in American and French oak chips, with substantially lower concentrations in Spanish oak chips (0.51–0.96 mg/L). In addition, in the same study, vanillin concentrations were found to be highest in American oak, followed by French oak, and markedly lower in Spanish oak chips (0.22–0.99 mg/L). These discrepancies between our findings and those of previous studies may be attributed not only to variations in wood dimensions and toasting conditions, but also to differences in alcohol strength and the presence of suspended solids in wine compared to tsipouro.

Hernández-Orte et al. [28] and Arapitsas et al.’s [29] studies have shown that elevated concentrations of syringaldehyde and vanillin in wines are often associated with the use of oak chips or fragments to replicate the sensory characteristics of barrel aging. Similarly, Juan et al. [30] reported higher syringaldehyde levels in lower-priced wines, suggesting the potential incorporation of wood fragments during production. These findings highlight syringaldehyde’s value as an indicator for distinguishing wines that have undergone traditional barrel aging from those exposed to alternative oak treatments. While the use of oak fragments is a cost-effective practice, ensuring transparency in product labeling remains essential. Clear disclosure of aging methods is necessary to prevent wines and alcoholic beverages from being marketed as barrel-aged at premium prices without meeting the corresponding* criteria. However, this potential misrepresentation could be mitigated through consumer education and awareness initiatives, which would help prevent misinformation and adulteration while reinforcing confidence in the authenticity and quality of these products.

These observations align closely with the findings of Hernández-Orte et al. [28], who proposed a systematic approach for differentiating the enological impact of oak barrels and wood fragments during the aging process. Specifically, their study identified three key criteria that could serve as a comprehensive framework for classification. According to Criterion 1, wines with syringaldehyde concentrations below 100 μg/L or vanillin and furfural concentrations below 20 μg/L are considered to have remained below the extraction threshold, implying minimal or no contact with wood. Criterion 2 establishes that a ratio of (vanillin + acetovanillone)/eugenol < 20 is indicative of wines aged in barrels, whereas Criterion 3 states that a ratio of (vanillin + acetovanillone)/eugenol > 20 suggests wines macerated with wood fragments. This framework not only enhances our understanding of oak aging in wines but could also be extended to other aged spirits, such as tsipouro, offering a more structured and objective evaluation of alternative aging methods.

As for the remaining compounds—trans-whisky lactone, cis-whisky lactone, coniferaldehyde, and 4-methyl-guaiacol—they were either detected at low concentrations or absent in certain samples. It is well-established that AO exhibits higher concentrations of cis-whiskey lactones compared to other oak varieties [31,32], while higher levels of vanillin are found in FO [31,33]. These compounds are considered characteristic markers of their respective wood species and origins. These observations are consistent with our findings, regardless of the wood fragment form (Figure 3).

However, when comparing trans-whisky lactone, as shown in Figure 3, FO exhibited slightly higher levels, followed by GO and AO, with GO falling in between French and American oak. The only exception was found in veneers, where no significant differences were observed between American and French oak (p > 0.05). On the other hand, trans- and cis-whiskey lactones, as well as coniferaldehyde, were consistently absent in all Greek chestnut (GC) samples, regardless of the wood fragment dimensions. Our findings—the presence of cis- and trans-whiskey lactones in oak wood and their absence in chestnut—are in line with those reported by Fernández de Simón et al. [34]. These authors also noted that cis- and trans-isomers of γ-methyl-γ-octalactone (whiskey lactones) were exclusively detected in oak wood, both before and after toasting, suggesting that these compounds could serve as potential chemical markers to distinguish oak from chestnut wood. In contrast, Caldeira et al. [35] reported significantly lower levels of these two isomers in Portuguese chestnut wood.

Interestingly, 4-methyl-guaiacol was not detected in any Greek oak (GO) samples, regardless of their form—veneers, particles, or sticks. Similarly, this compound was not extracted from American oak veneers or Greek chestnut particles, which may be due to its low concentration, preventing detection.

The consistent absence of 4-methyl-guaiacol in all GO samples suggests its potential non-existence in this wood species. This finding may serve as a unique chemical marker, distinguishing GO from other oak varieties and potentially aiding in the detection of adulteration, much like cis-whiskey lactone in AO and vanillin in FO. Moreover, a comparable distinction could be drawn for Greek chestnut, where the absence of coniferaldehyde, cis-whisky lactone, and trans-whisky lactone may further differentiate its chemical profile and aid in fraud detection. However, further research is required to validate these findings and establish robust chemical markers that can effectively prevent fraudulent practices.

Focusing further on the various wood dimensions (veneers, particles, and sticks), significant differences (p < 0.05) in volatile compound extraction were observed (Table 1). Sticks were observed to be more suitable for the extraction of certain compounds, often yielding similar or even higher extraction rates compared to veneers. This trend was particularly evident for coniferaldehyde, which was not detected in either American oak veneers or particles. Veneers also demonstrated suitable extraction efficiency in the case of syringaldehyde from FO. On the other hand, particle fragments may be considered less effective, particularly in the case of chestnut wood, as they exhibited lower extraction yields. Moreover, a notable decrease in sinapaldehyde extraction was shown in both FO and AO particles, exceeding ~67% and 50%, respectively, compared to sticks (Table 1). However, in the case of GO, the overall profile showed that the concentrations across different fragments were similar, with no statistically significant differences.

The observed significant differences between particle, veneer, and stick fragments could likely be attributed to variations in wood dimensions. Veneers and sticks, due to their larger surface contact with the distillate, may enhance extraction efficiency. Although the total surface area of the wood fragments was comparable, the extraction process for veneers and sticks was more effective than for particles. However, in the case of veneers, a significantly smaller amount of wood was required, suggesting a potential economic advantage. This approach allows for optimized wood utilization. Ultimately, all three forms of wood fragments—veneers, particles, and sticks—could be used depending on the specific scientific or industrial needs, economic considerations, and the desired organoleptic characteristics to be imparted.

3.2. Assessing Total Ellagitannin Levels in Aged Tsipouro

It is widely known that oak wood contributes non-volatile compounds, such as ellagitannins, to the wine [26,36,37,38,39]. Motivated by this, the study of ellagitannins in aged tsipouro was of particular interest.

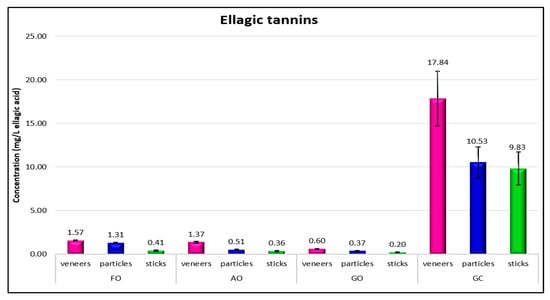

Initially, the total ellagitannin content was estimated based on the amount of ellagic acid released through acidic hydrolysis. In this process, each ellagitannin monomer or dimer yields one molecule of ellagic acid. The total ellagitannin concentration, expressed as mg/L of ellagic acid released in a spirit model solution, was applied to our samples and showed considerable variability, ranging from 0.20 to 17.84 mg/L, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The total ellagic tannins’ concentration, expressed as mg/L of ellagic acid in aged tsipouro after contact with different wood fragment types (veneers, particles, sticks) from four wood origins (French oak (FO), American oak (AO), Greek oak (GO), and Greek chestnut (GC)). Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

High levels of ellagitannins were notably observed in Greek chestnut wood across all wood fragment types. This finding aligns with the higher content of ellagic acid (potentially derived from ellagic tannins) found in wines aged in chestnut compared to oak, as reported in previous studies [40,41].

In comparison to chestnut, French and American oak showed lower concentrations of ellagitannins, with Greek oak exhibiting the lowest levels, ranging from 0.20 to 0.60 mg/L. This may suggest that regional origin and oak species may significantly influence ellagitannin content.

When examining the different wood diameters, veneers were the most effective for the extraction of ellagitannins, followed by particles with moderate efficiency, while sticks were found to be the least suitable. This difference is likely due to the thickness of the wood fragment, where, during the toasting and aging process, ellagic tannins may be more easily extracted from a very thin wood, such as veneers, which have a thickness of 0.2 cm and a width of 5 cm.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights the influence of wood origin and the geometry of barrel alternatives on the extraction of volatile compounds and ellagitannins during tsipouro aging. French oak showed the highest levels of key aromatic compounds, whereas Greek chestnut contributed the greatest ellagitannin content. Among the wood fragment types, veneers were found to be the most efficient for extraction, likely due to their thinness and increased surface area, while sticks were less effective, particularly for ellagitannins. In contrast, sticks were less effective, particularly for ellagitannins. The use of wood fragments offers an eco-friendly, practical, economical, fast, and effective alternative to traditional barrel aging.

Beyond these technological insights, the findings also emphasize the broader connection between material origin and product identity. Although distillation limits the direct impact of terroir compared to wine, grape variety and regional characteristics still influence the aromatic and compositional traits of tsipouro. Moreover, the use of Greek wood species such as Quercus trojana (Greek oak) and Castanea sativa (chestnut) for aging introduces additional regional elements, enriching the spirit’s authenticity and reinforcing its local character. Given that tsipouro holds a Geographical Indication status, the integration of locally sourced materials—both grapes and wood—can further strengthen its connection to place and contribute to the development of distinctive, high-quality aged products representative of the Greek terroir. Therefore, future research could investigate in greater depth the relationship between tsipouro typicity, terroir, and the provenance of the wood used for aging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and Y.K.; methodology, A.K. and Y.K.; software, A.K. and G.S.; formal analysis, A.K. and N.K.; data curation, A.K., G.S., and N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, N.K., G.N., and Y.K.; supervision, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Laboratory of Quality Control of Wooden Products and Wood Constructions, Department of Forestry, Wood Sciences, and Design at the University of Thessaly (Karditsa, Greece), for providing the Greek wood samples and preparing the wood fragments. They also wish to thank “Tonellerie Nadalie” (Bordeaux, France) for providing the American and French oak staves.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) 2019/787 of 17 April 2019. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L130, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Marinaki, M.; Sampsonidis, I.; Nakas, A.; Arapitsas, P.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Theodoridis, G. Analysis of the Volatile Organic Compound Fingerprint of Greek Grape Marc Spirits of Various Origins and Traditional Production Styles. Beverages 2023, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aade.gr. Ethyl Alcohol and Alcoholic Beverages. L 2969/2001—FEK 281/A/18-12-2001. Available online: https://www.aade.gr/sites/default/files/2020-03/6%20%CE%A6%CE%95%CE%9A%20281-%CE%91-2001_0.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Kourilas, E.L. The Vineyards of Mount Athos. In Athos, Light in Darkness; Athonite Reprints: Mount Athos, Greece, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Soufleros, E.H.; Rodovitis, B.A. Tsipouro and Tsikoudia: The Greek Grape Mark Distillate; Soufleros Evangelos: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Data General Chemical State Laboratory (G.C.S.L.). Edit Greek Federation of Spirits Producers (SEAOP). 2023. Available online: https://www.seaop.gr/press-office/press-releases?pageNo=2 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Kokoti, K.; Kosma, I.S.; Tataridis, P.; Badeka, A.V.; Kontominas, M.G. Volatile Aroma Compounds of Distilled “Tsipouro” Spirits: Effect of Distillation Technique. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karathanos, A.; Soultani, G.; Kontoudakis, N.; Kotseridis, Y. Impact of Different Wood Types on the Chemical Composition and Sensory Profile of Aged Tsipouro: A Comparative Study. Beverages 2024, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.S. Wine Science: Principles and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Puech, J.L. Extraction and Evolution of Lignin Products in Armagnac Matured in Oak. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1981, 32, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, J.M.; Paterson, A.; Piggott, J.R. Changes in Wood Extractives from Oak Cask Staves Through Maturation of Scotch Malt Whisky. J. Sci. Food Agric 1993, 62, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatonnet, P.; Dubourdie, D.; Boidron, J.N.; Pons, M. The Origin of Ethylphenols in Wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1992, 60, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakourou, M.; Strati, I.F.; Manika, E.-M.; Resiti, V.; Tataridis, P.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Assessment of Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, Colour and Sensory Attributes of Wood Aged “Tsipouro”. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 6, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canas, S.; Casanova, V.; Belchior, A.P. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Content of Portuguese Wine Aged Brandies. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, M.V.; Sánchez-Guillén, M.M.; Ruiz de Mier, M.; Delgado-González, M.J.; Rodríguez-Dodero, M.C.; García-Barroso, C.; Guillén-Sánchez, D.A. Use of Alternative Wood for the Ageing of Brandy de Jerez. Foods 2020, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Belchior, A.P.; Clímaco, M.C.; Bruno de Sousa, R. Aroma Profile of Portuguese Brandies Aged in Chestnut and Oak Woods. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 458, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Anjos, O.; Portal, V.; Belchior, A.P.; Canas, S. Sensory and Chemical Modifications of Wine-Brandy Aged with Chestnut and Oak Wood Fragments in Comparison to Wooden Barrels. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 660, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourdes, M.; Michel, J.; Saucier, C.; Quideau, S.; Teissedre, P.-L. Identification, Amounts, and Kinetics of Extraction of C-Glucosidic Ellagitannins during Wine Aging in Oak Barrels or in Stainless Steel Tanks with Oak Chips. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvela, E.; Makris, D.P.; Kefalas, P.; Moutounet, M. Extraction of Phenolics in Liquid Model Matrices Containing Oak Chips: Kinetics, Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectroscopy Characterisation and Association with In Vitro Antiradical Activity. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gómez, R.; del Alamo-Sanza, M.; Martínez-Gil, A.M.; Nevares, I. Red Wine Aging by Different Micro-Oxygenation Systems and Oak Wood—Effects on Anthocyanins, Copigmentation and Color Evolution. Processes 2020, 8, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Picariello, L.; Moio, L.; Waterhouse, A.L. Cabernet Sauvignon Aging Stability Altered by Microoxygenation. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 70, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, M.T.; Capuano, R.; Moio, L.; Gambuti, A. Wood Powders of Different Botanical Origin as an Alternative to Barrel Aging for Red Wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) 2165/2005 of 20 December 2005. Off. J. Eur. Union 2005, L345, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) 1507/2006 of 11 October 2006. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L280, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, V.; Stefova, M.; Stafilov, T.; Vojnoski, B.; Bíró, I.; Bufa, A.; Kilár, F. Validation of a Method for Analysis of Aroma Compounds in Red Wine Using Liquid–Liquid Extraction and GC–MS. Food Anal. Methods 2012, 5, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chira, K.; Teissedre, P.L. Extraction of Oak Volatiles and Ellagitannins Compounds and Sensory Profile of Wine Aged with French Winewoods Subjected to Different Toasting Methods: Behaviour During Storage. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bencomo, J.J.; Ortega-Heras, M.; Pérez-Magariño, S.; González-Huerta, C. Volatile Compounds of Red Wines Macerated with Spanish, American, and French Oak Chips. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6383–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orte, P.; Franco, E.; Huerta, C.G.; García, J.M.; Cabellos, M.; Suberviola, J.; Orriols, I.; Cacho, J. Criteria to Discriminate Between Wines Aged in Oak Barrels and Macerated with Oak Fragments. Food Res. Int. 2014, 57, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapitsas, P.; Antonopoulos, A.; Stefanou, E.; Dourtoglou, V.G. Artificial Aging of Wines Using Oak Chips. Food Chem. 2004, 86, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, F.S.; Cacho, J.; Ferreira, V.; Escudero, A. Aroma Chemical Composition of Red Wines from Different Price Categories and Its Relationship to Quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5045–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Prieto, L.J.; López-Roca, J.M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; Pardo Mínguez, F.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Maturing Wines in Oak Barrels: Effects of Origin, Volume, and Age of the Barrel on the Wine Volatile Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3272–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Maroto, M.C.; Guchu, E.; Castro-Vázquez, L.; de Torres, C.; Pérez-Coello, M.S. Aroma-Active Compounds of American, French, Hungarian and Russian Oak Woods, Studied by GC–MS and GC–O. Flavour Fragr. J. 2008, 23, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdán, T.G.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Volatile Composition of Aged Wine in Used Barrels of French Oak and of American Oak. Food Res. Int. 2002, 35, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Simón, B.; Cadahía, E.; Del Álamo, M.; Nevares, I. Volatile Compounds in Acacia, Chestnut, Cherry, Ash and Oak Woods, With a View to Their Use in Cooperage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3217–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Clímaco, M.C.; de Sousa, R.B.; Belchior, A.P. Volatile Composition of Oak and Chestnut Woods Used in Brandy Ageing: Modification Induced by Heat Treatment. J. Food Eng. 2006, 76, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estévez, I.; Alcalde-Eon, C.; Le Grottaglie, L.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T. Understanding the Ellagitannin Extraction Process from Oak Wood. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 3089–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chira, K.; Anguellu, L.; Da Costa, G.; Richard, T.; Pedrot, E.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.-L. New C-Glycosidic Ellagitannins Formed upon Oak Wood Toasting, Identification and Sensory Evaluation. Foods 2020, 9, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadrat, M.; Lavergne, J.; Emo, C.; Teissedre, P.L.; Chira, K. Validation of a Mass Spectrometry Method to Identify and Quantify Ellagitannins in Oak Wood and Cognac During Aging in Oak Barrels. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 128223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Centeno, M.R.; Chira, K.; Teissedre, P.L. Ellagitannin content, volatile composition and sensory profile of wines from different countries matured in oak barrels subjected to different toasting methods. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalekou, M.; Kallithraka, S.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Kotseridis, Y.; Pappas, C. Ellagitannins in Wines: Future Prospects in Methods of Analysis Using FT-IR Spectroscopy. LWT 2019, 101, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alañón, M.E.; Castro-Vázquez, L.; Díaz-Maroto, M.C.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Gordon, M.H.; Pérez-Coello, M.S. Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolic Composition of Different Woods Used in Cooperage. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1584–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).