Valorization of Second-Grade Watermelon in a Lycopene-Rich Craft Liqueur: Formulation Optimization, Antioxidant Stability, and Consumer Acceptance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock Supply and Pre-Treatment

2.2. Experimental Design and Maceration

2.3. Downstream Processing

2.4. Analytical Determinations

2.5. Sensory Evaluation

2.6. Storage Stability

2.7. Mass-Balance and Carbon Footprint

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Ethics and AI Statement

3. Results

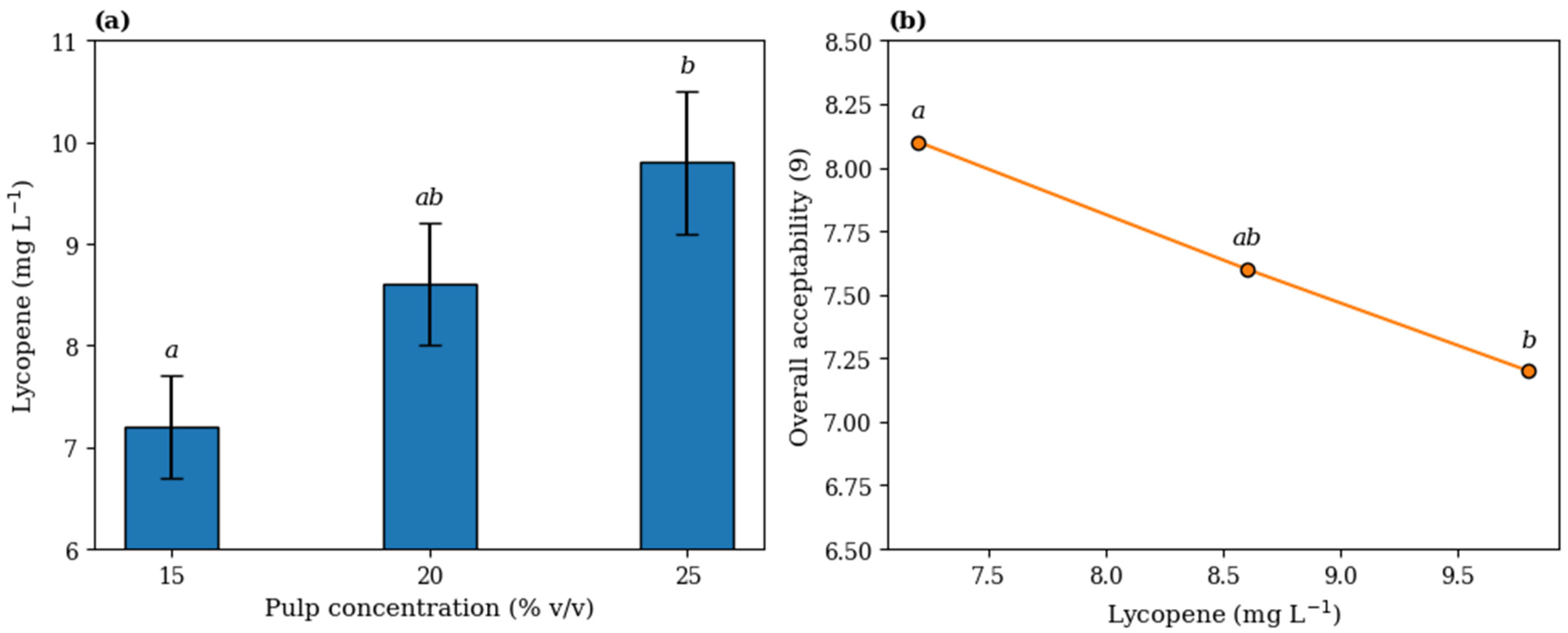

3.1. Physicochemical Profile and Lycopene Recovery

3.2. Sensory Acceptance and Consumer Clustering

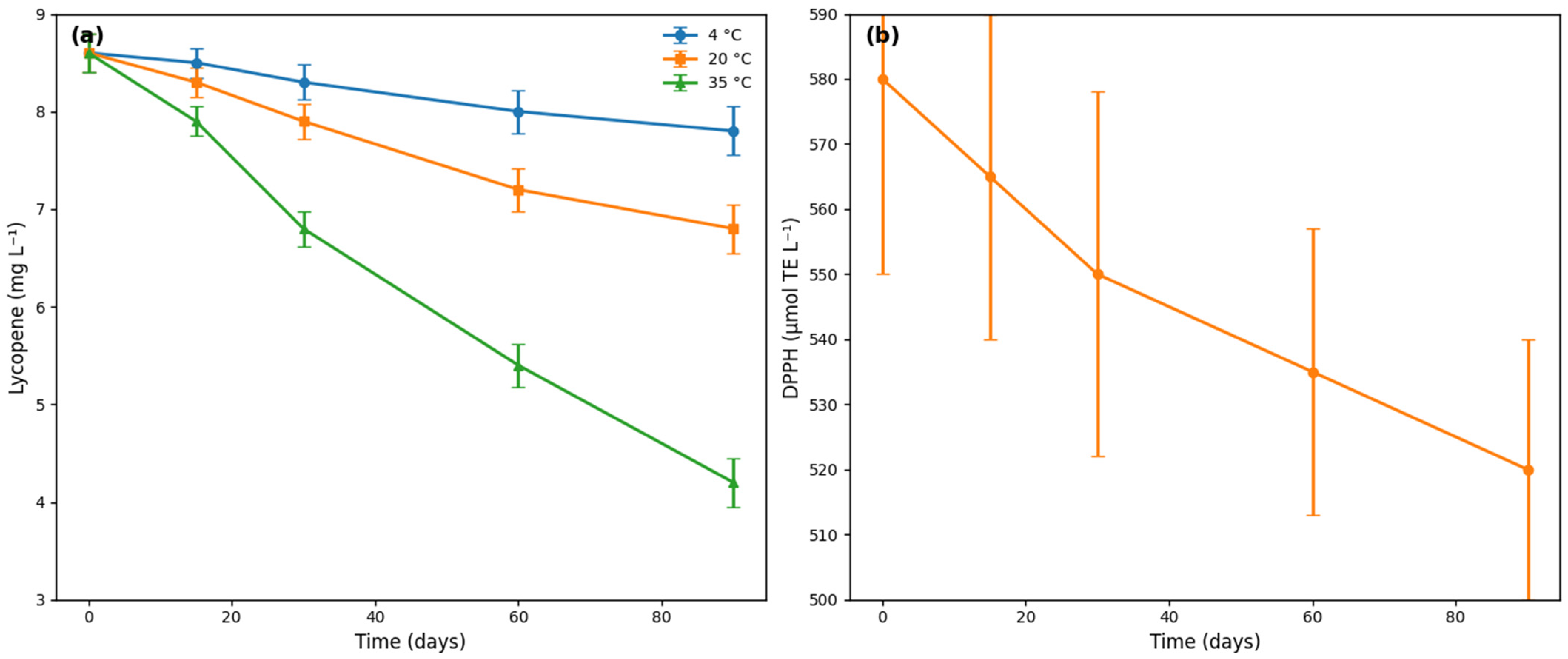

3.3. Storage Stability and Shelf-Life Projection

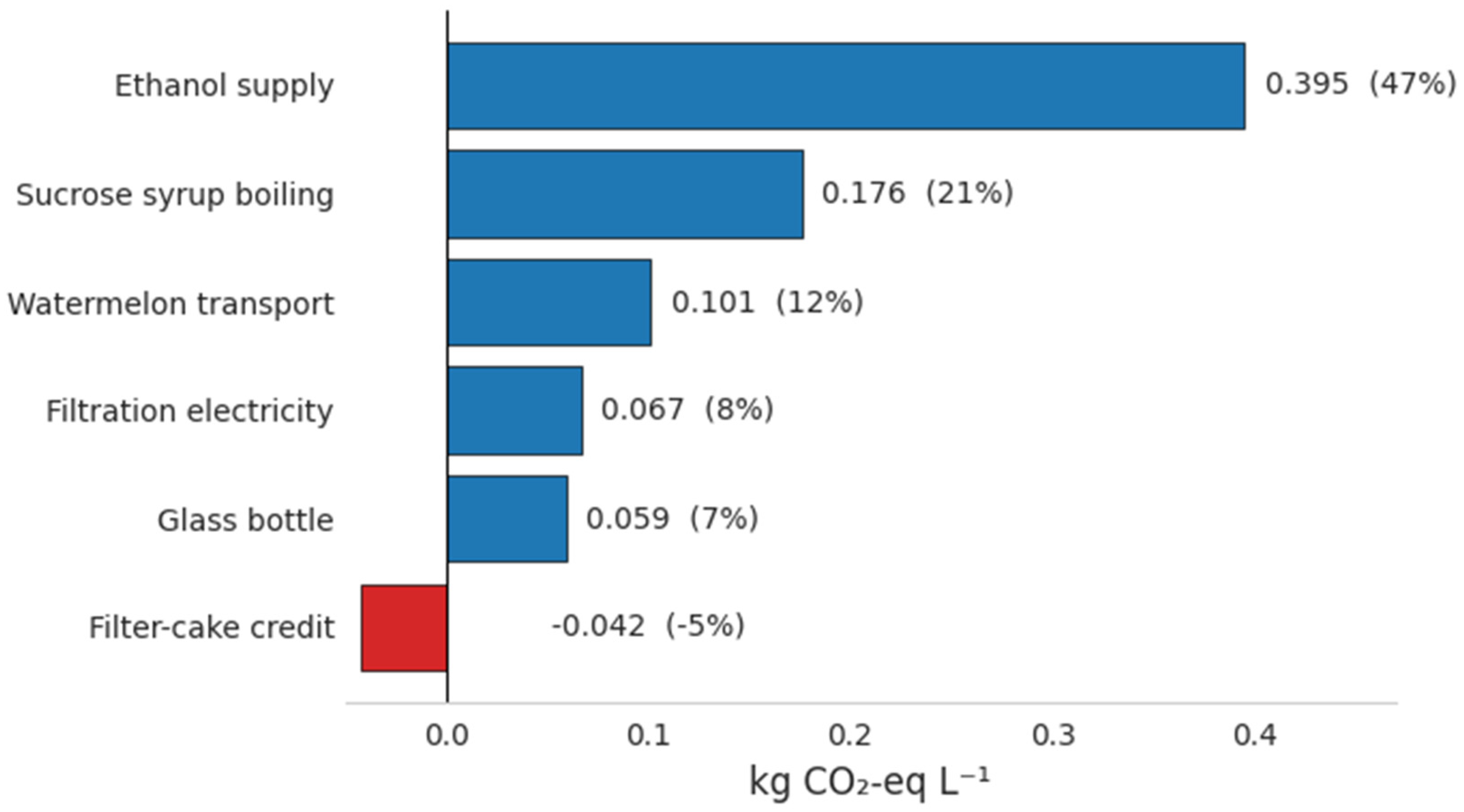

3.4. Cradle-to-Gate Carbon Footprint

3.5. Scale-Up Verification

4. Discussion

4.1. Physicochemical Profile and Lycopene Recovery

4.2. Sensory Acceptance and Consumer Clustering

4.3. Storage Stability and Shelf-Life Projection

4.4. Carbon Footprint and Hot-Spot Analysis

4.5. Scale-Up Verification and Economic Outlook

4.6. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CIE | Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| Ea | Activation energy |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| INFOGEST | International consensus static in vitro digestion protocol |

| LCA | Life-cycle assessment |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| TE | Trolox equivalent |

| VS | Volatile solids |

References

- Grand View Research. Craft Spirits Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report 2024–2030; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/craft-spirits-market (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Postigo, V.; García, M.; Crespo, J.; Canonico, L.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Bioactive Properties of Fermented Beverages: Wine and Beer. Fermentation 2025, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritika; Rizwana; Shukla, S.; Sondhi, A.; Tripathi, A.D.; Lee, J.-K.; Patel, S.K.; Agarwal, A. Valorisation of fruit waste for harnessing the bioactive compounds and its therapeutic application. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Statistical Database; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Perkins-Veazie, P.; Collins, J.K.; Davis, A.R.; Roberts, W. Carotenoid Content of 50 Watermelon Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2593–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salin, N.S.M.; Saad, W.M.M.; Razak, H.R.A.; Salim, F. Effect of Storage Temperatures on Physico-Chemicals, Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Properties of Watermelon Juice (Citrullus lanatus). Metabolites 2022, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP). Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola: Cierre 2023. Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/anuario-estadistico-de-la-produccion-agricola (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.-J. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, E.; Raikos, V. Lycopene in Beverage Emulsions: Optimizing Formulation Design and Processing Effects for Enhanced Delivery. Beverages 2018, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafieiro, C.S.; Tavares, P.P.L.; DE Souza, C.O.; Cruz, L.F.; Mamede, M.E.O. Elaboration of wild passion fruit (Passiflora cincinnata Mast.) liqueur: A sensory and physicochemical study. An. da Acad. Bras. de Cienc. 2022, 94, e20211446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, M.E.A.O.; Gomes, M.d.R.; Junior, N.d.M.A.; Candeias, V.M.S.; Lima, D.A.; Vilar, S.B.d.O.; da Silva, A.B.M. Influência de diferentes técnicas de extração sobre a capacidade antioxidante do da casca de melancia desidratada. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e323101321333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.; Cosme, F.; Nunes, F.M. Production and Characterization of Red Fruit Spirits Made from Red Raspberries, Blueberries, and Strawberries. Foods 2024, 13, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 8586:2023; Sensory analysis: Selection and Training of Sensory Assessors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/76667.html (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Davis, A.; Fish, W.; Perkins-Veazie, P. A Rapid Hexane-free Method for Analyzing Lycopene Content in Watermelon. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badin, E.; Quevedo-Leon, R.; Ibarz, A.; Ribotta, P.; Lespinard, A. Kinetic Modeling of Thermal Degradation of Color, Lycopene, and Ascorbic Acid in Crushed Tomato. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.L. Food Packaging: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, C.; Güneş, S.; Vilela, A.; Gomes, R. Life-Cycle Assessment in Agri-Food Systems and the Wine Industry—A Circular Economy Perspective. Foods 2025, 14, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, V.; Bitsch, R. Intestinal absorption of lycopene from different matrices and interactions to other carotenoids, the lipid status, and the antioxidant capacity of human plasma. Eur. J. Nutr. 1999, 38, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC International. Luff-Schoorl Method. In Official Methods of Analysis, 21st ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmanović, M.; Makajić-Nikolić, D. Heterogeneity of Serbian consumers’ preferences for local wines: Discrete choice analysis. Ekon. Poljopr. 2020, 67, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, H.; Seyedimany, A. Wine consumer typologies based on level of involvement: A case of Turkey. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2023, 35, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, M.; Touranlou, F.A.; Rezaie, M. Sensory evaluation methods for food products targeting different age groups: A review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentair. X-Flow R-100 Microfiltration Module—Technical Datasheet; Pentair: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malisic, B.; Misic, N.; Krco, S.; Martinovic, A.; Tinaj, S.; Popovic, T. Blockchain Adoption in the Wine Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdeano, M.C.; Gomes, F.d.S.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Almeida, E.L.; Moulin, L.C.; de Grandi Castro Freitas de Sá, D.; Tonon, R.V. Lycopene-rich watermelon concentrate used as a natural food colorant: Stability during processing and storage. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Total Soluble Solids (°Brix) | Total Sugars (g 100 g−1) | pH | Lycopene (mg L−1) | Color CIE | Overall Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (15%) | 24.1 ± 0.4 a | 6.2 ± 0.2 a | 5.6 ± 0.1 a | 7.2 ± 0.5 a | L*: 28.4 ± 0.9 a | 7.1 ± 0.7 a |

| a*: 12.3 ± 0.5 a | ||||||

| b*: 8.7 ± 0.4 a | ||||||

| T2 (20%) | 23.3 ± 0.5 b | 6.1 ± 0.3 a | 5.7 ± 0.1 a | 8.6 ± 0.6 b | L*: 26.1 ± 1.0 b | 7.6 ± 0.6 ab |

| a*: 14.1 ± 0.6 b | ||||||

| b*: 9.2 ± 0.5 a | ||||||

| T3 (25%) | 22.0 ± 0.6 c | 6.4 ± 0.2 a | 5.9 ± 0.2 b | 9.8 ± 0.7 c | L*: 24.7 ± 1.1 c | 7.2 ± 0.8 b |

| a*: 15.8 ± 0.7 c | ||||||

| b*: 9.8 ± 0.6 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cervantes-Vázquez, M.G.; Luna-Ortega, J.G.; Cervantes-Vázquez, T.J.Á.; Ríos-Plaza, J.L.; García-Carrillo, M.; Márquez-Mendoza, J.I.; Vela-Perales, V.; Valenzuela-García, A.A.; Gonzales-Torres, A. Valorization of Second-Grade Watermelon in a Lycopene-Rich Craft Liqueur: Formulation Optimization, Antioxidant Stability, and Consumer Acceptance. Beverages 2025, 11, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060175

Cervantes-Vázquez MG, Luna-Ortega JG, Cervantes-Vázquez TJÁ, Ríos-Plaza JL, García-Carrillo M, Márquez-Mendoza JI, Vela-Perales V, Valenzuela-García AA, Gonzales-Torres A. Valorization of Second-Grade Watermelon in a Lycopene-Rich Craft Liqueur: Formulation Optimization, Antioxidant Stability, and Consumer Acceptance. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060175

Chicago/Turabian StyleCervantes-Vázquez, María Gabriela, J. Guadalupe Luna-Ortega, Tomás Juan Álvaro Cervantes-Vázquez, Juan Luis Ríos-Plaza, Mario García-Carrillo, J. Isabel Márquez-Mendoza, Vianey Vela-Perales, Ana Alejandra Valenzuela-García, and Anselmo Gonzales-Torres. 2025. "Valorization of Second-Grade Watermelon in a Lycopene-Rich Craft Liqueur: Formulation Optimization, Antioxidant Stability, and Consumer Acceptance" Beverages 11, no. 6: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060175

APA StyleCervantes-Vázquez, M. G., Luna-Ortega, J. G., Cervantes-Vázquez, T. J. Á., Ríos-Plaza, J. L., García-Carrillo, M., Márquez-Mendoza, J. I., Vela-Perales, V., Valenzuela-García, A. A., & Gonzales-Torres, A. (2025). Valorization of Second-Grade Watermelon in a Lycopene-Rich Craft Liqueur: Formulation Optimization, Antioxidant Stability, and Consumer Acceptance. Beverages, 11(6), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060175