Abstract

The Songhua River Basin (SRB) in Northeast China is a high-latitude basin experiencing significant snow cover changes under global warming. This study quantified spatiotemporal changes in snowmelt in the SRB (1961–2020). A specific focus was placed on the changes at event scale, including frequency, magnitude and duration, that have been underexplored in previous work. Correlations between snowmelt and key driving factors were assessed to identify the dominant controls governing the melt process. A significant elevation-dependent decreasing trend in annual snowmelt was found over the decades, with the decrease most pronounced at lower elevations. Relative to the baseline period (1961–1990), the snowmelt dates during 1991–2020 advanced, with the 25%, 50%, and 75% cumulative levels occurring 9, 6, and 2 days earlier, respectively. Seasonally, snowmelt increased significantly in early spring (February to March) but decreased notably in late spring (April to May). Snowmelt events exhibited reduced frequency, total volume, peak value, and mean rate, along with fewer extreme events. The strongest correlation across snowmelt event types was found with mean snow depth for complete depletion and with accumulated sunshine duration for incomplete depletion, while Rain-on-Snow Melt events were most closely associated with sunshine and temperature. This study can provide a crucial reference for sustainable water management and spring agricultural irrigation in the SRB.

1. Introduction

Seasonal snowpack is a critical component of the global climate system and plays a vital role in the hydrological cycle. Its high albedo and low thermal conductivity regulate surface energy balance, soil temperature, and atmospheric dynamics [1]. However, rapid snow ablation processes can trigger severe natural disasters. Melt rates during extreme events can even surpass concurrent precipitation, triggering cascading hazards including landslides, dam failures, and floods [2]. Global warming is projected to intensify the hydrological cycle, leading to profound alterations in the frequency, intensity, and timing of snowmelt events globally [3,4,5]. The distribution characteristics of snow, such as range, depth, and duration, directly determine the potential scale and timing of meltwater release, and the changes in its distribution pattern caused by climate change will further reshape the risk pattern of related disasters. Therefore, a precise understanding of the spatiotemporal patterns of snowmelt and its climatic drivers is crucial for proactive climate adaptation, sustainable water resource management, and effective hazard mitigation [6,7].

Observational evidence confirms widespread changes in snowmelt dynamics. A general advancement in snowmelt timing has been documented across many mountainous regions worldwide [8]. Declining snow water equivalent (SWE) across deep-snowpack areas has contributed to a decreasing trend in snow ablation rates over the mid-to-high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere [9]. For extreme snowmelt events, warming-induced snowpack reduction is identified as a key factor suppressing both snowmelt and the frequency of extreme melt events [10]. Compounding these changes, a projected shift from snowfall to rainfall is expected to increase the occurrence of rain-on-snow events [11], which exhibit strong regional heterogeneity but can dramatically accelerate melt [12,13]. The interplay of climatic factors, including temperature, precipitation phase, total precipitation, and snowpack properties, collectively governs these complex changes [14].

The Songhua River Basin (SRB) in Northeast China is a critical region for such investigation. As a major seasonal snow cover region and an essential agricultural zone, ecological and socio-economic systems in the basin are heavily dependent on the snow storage and spring meltwater recharge [15]. This basin is highly sensitive to global warming, and recent spatiotemporal variations in snow cover and snowfall have garnered considerable attention [16]. Zhong et al. reported a delayed snow season onset, an advanced end date, and a consequently shortened snow season, despite no clear trend in total snowfall amount [17]. A critical knowledge gap remains regarding a systematic, long-term, and event-scale analysis of the snowmelt process itself within the SRB. Addressing this gap is crucial for deciphering the direct impacts of climate change on the hydrological system in the basin.

To address this gap, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of snowmelt dynamics and their climatic drivers in the Songhua River Basin over the period 1961–2020. Our specific objectives are as follows: (1) to quantify the spatiotemporal characteristics of snowmelt; (2) to reveal the changing patterns of snowmelt processes at the event scale; and (3) to assess the correlation between snowmelt events and key climatic factors, thereby clarifying the impact of climate change on basin-scale snowmelt. The findings are expected to inform critical water resource decisions, particularly in mitigating spring agricultural droughts and optimizing irrigation scheduling, thereby enhancing climate resilience for this vital agricultural region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region

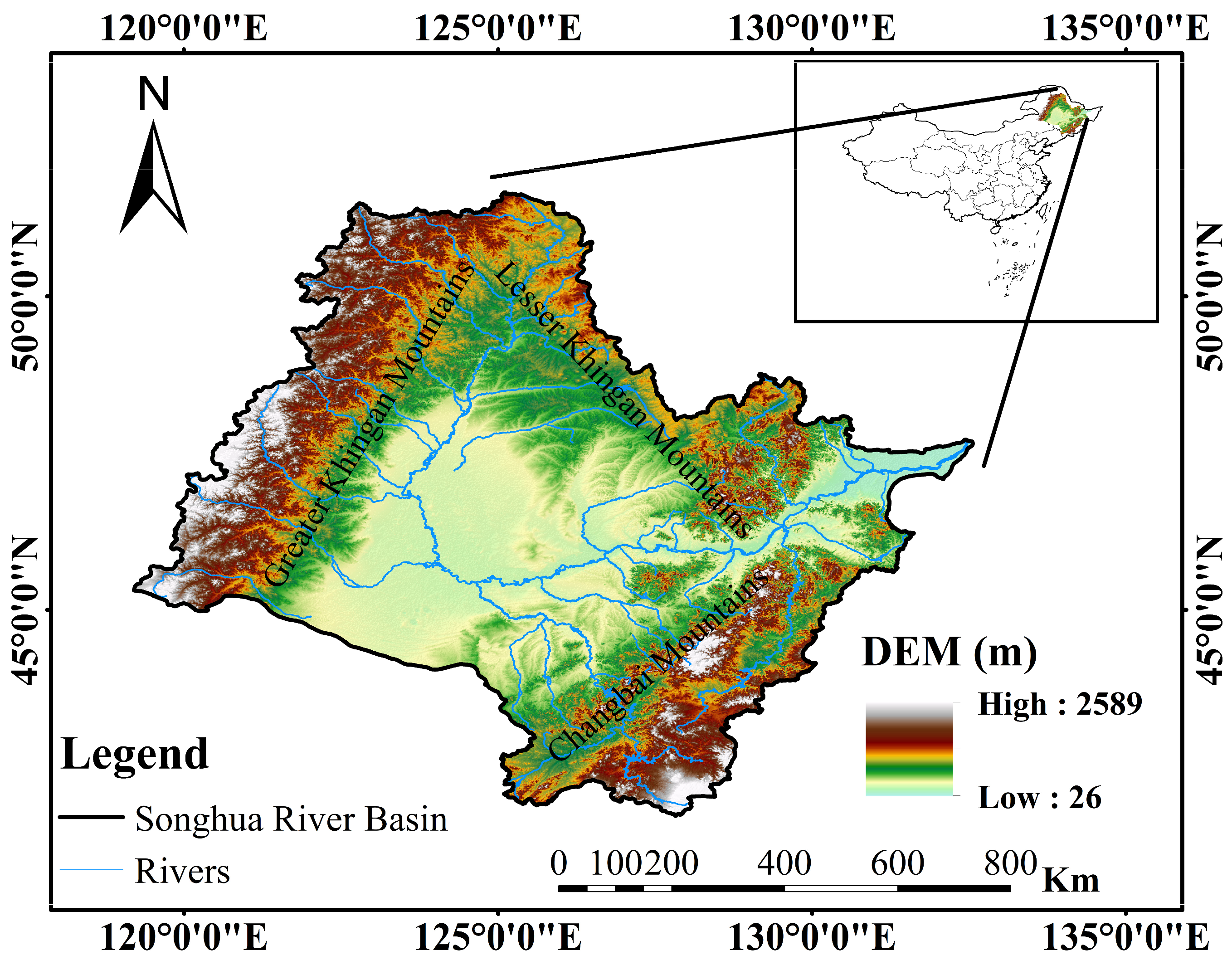

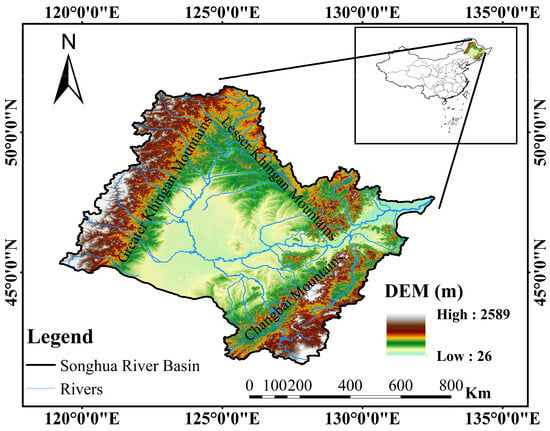

The SRB is located in Northeast China, with a geographical range from 119°52′ to 132°31′ E and 41°42′ to 51°38′ N, covering a total area of approximately 556,800 km2 (Figure 1). The basin is surrounded by mountains on three sides, including the Greater and Lesser Khingan Mountains, which form barriers to the west and north, respectively, while the Changbai Mountains define the eastern boundary. The mean annual temperature across the basin ranges from −5 °C to 6 °C [18]. The average annual precipitation throughout the basin ranges between 379.55 mm and 827.88 mm, showing a decreasing trend from east to west [19].

Figure 1.

Location and topography of the Songhua River Basin (SRB).

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. ERA5-Land Data

This study uses daily precipitation, snow depth and snowmelt data from the ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-land, URL (accessed on 15 September 2024)) for the SRB from 1961 to 2021. ERA5-Land is the latest reanalysis dataset produced by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), with a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°, providing higher resolution compared to its predecessors, ERA-Interim and ERA5. In the dataset, snow depth represents the snow water equivalent depth within the snow-covered area of a grid, with a unit of meters. It has already accounted for the influence of snow cover fraction. That is, when only part of a grid box is covered by snow, the value given is the average water equivalent depth converted for the entire grid box. Snowmelt refers to the accumulated amount of water resulting from the melting of snow within the snow-covered area. It is also expressed in meters of water equivalent, representing the depth of water if the melted snow were spread evenly over the whole grid box. For example, if 50% of a grid box is snow-covered, and the water from melting that snow is equivalent to a depth of 0.02 m, this parameter would have a value of 0.01 m. In this study, the original values (in meters) for the aforementioned parameters were uniformly converted to millimeters (mm) to facilitate analysis.

The ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset offers high spatiotemporal resolution. Therefore, this study validated the snow depth data using an independent satellite-based product—the Long-term Series of Daily Snow Depth Dataset in China (1979–2024) sourced from the National Tiβn Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/) [20]. It was generated from multi-sensor passive microwave brightness temperature data via a well-established retrieval algorithm, with a spatial resolution of 0.25°, and provides daily snow depth information. In this study, a spatiotemporal comparison was conducted between the ERA5-Land snow depth data and this dataset for their overlapping period from 1979 to 2021.

According to Tan et al. [21], a hydrological year in this study is defined from 1 August to 31 July of the following year. Both annual snowmelt and annual snow depth are calculated according to this hydrological year framework. Based on the snow cover phenology in Northeast China [22,23], the snow season is divided into two distinct phases: the Snow Depth Accumulation Period (SDAP, spanning 1 September to 31 January) and the Snow Depth Ablation Period (SDABP, spanning 1 February to 31 May).

2.2.2. Weather Data

Weather data for the SRB from 1961 to 2021, including mean temperature, maximum temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and sunshine duration, were obtained from the CN05.1 daily dataset to assess their influence on snowmelt processes. These data were also calculated for the hydrological year. CN05.1 is a high-resolution gridded meteorological dataset developed by the National Meteorological Information Center of the China Meteorological Administration (http://data.cma.cn). It was constructed based on historical data from over 2400 surface observation stations across China, using thin plate spline interpolation and angular distance weighting methods for spatial interpolation, with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°.

2.2.3. DEM

A Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of the SRB was extracted from SRTMDEM90 for topographic analysis. SRTMDEM90 is a standardized global topographic dataset jointly developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), based on data acquired during the Space Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) in 2000. The data was obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/). The dataset was generated using Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) technology, with an original spatial resolution of approximately 90 m.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Delineation and Characterization of Snowmelt Events

For the definition of snowmelt events, a threshold of daily snowmelt ≥ 0.1 mm was applied, and consecutive periods meeting this condition with a minimum duration of one day were identified as independent events. The daily melting threshold of ≥0.1 mm was selected to sensitively capture the beginning of spring snowmelt and weak snowmelt signals, and maintain the continuity of the snowmelt period for accurate hydrological analysis. This method is consistent with the common practice in mid to high latitude snow research, where 0.1 mm of water column per day is widely used as a baseline sensitivity threshold for detecting melting occurrence while minimizing noise [24,25].

Subsequently, characteristics such as frequency, Total Snowmelt (TSM), Peak Daily Snowmelt (PDSM), Snowmelt Duration (SMD), and Mean Snowmelt Rate (MSMR) were analyzed.

This study identifies independent snowmelt events from observed snow depth data. Events are classified into two types according to snow depth at the end of melting. Complete Snow Depletion (CSD) events occur when snow depth decreases to 0.1 mm or less, indicating full ablation of the snowpack. In these cases, the average snow depth primarily controls the maximum available meltwater. Incomplete Snow Depletion (ICSD) events are those where snow depth remains above 0.1 mm after melting, reflecting partial ablation or an interrupted melt process.

Generally, Rain-on-Snow (ROS) events are defined by liquid precipitation falling on an existing snow cover [26]. This study does not directly identify such ROS events. Instead, we first identify broader snowmelt events. To identify the specific contribution of rainfall to melt, we then define a subclass of snowmelt events termed Rain-on-Snow Melt (ROSm) event, during which at least a daily rainfall larger than 0.1 mm occurs.

2.3.2. Influencing Factors of Snowmelt Events

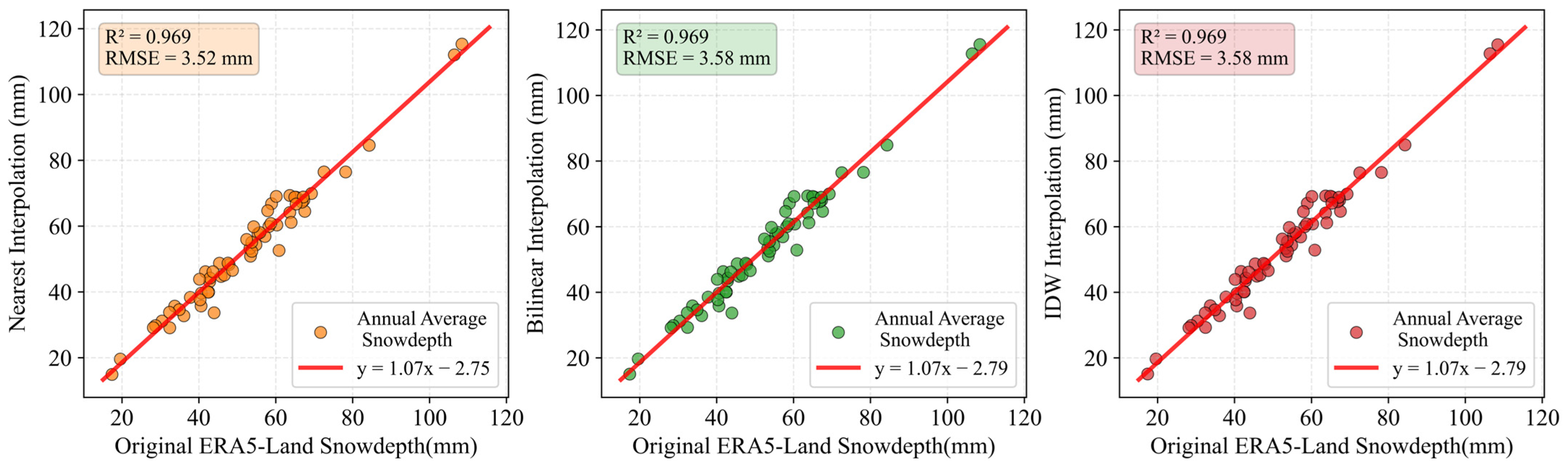

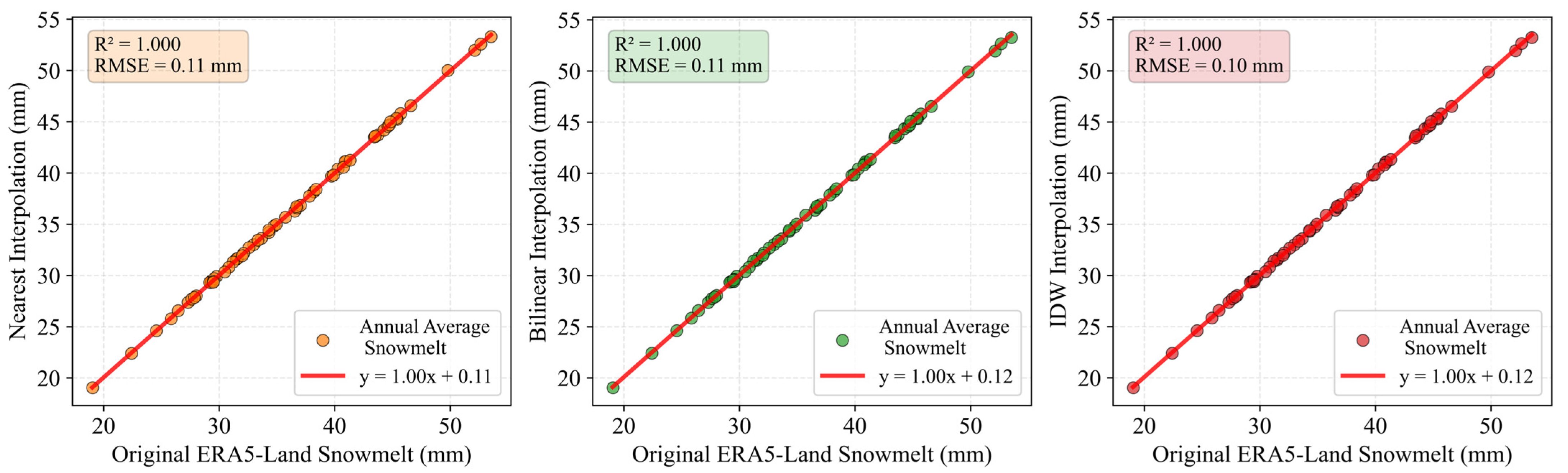

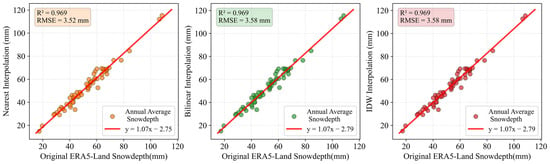

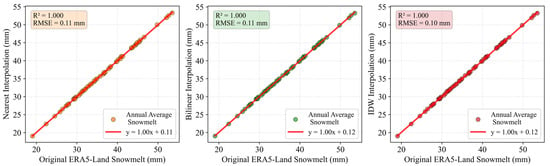

To analyze the influencing factors of snowmelt events, this study first resampled the precipitation, snow depth and snowmelt data from ERA5-Land to a uniform spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° and aligned them strictly with the meteorological data. To select an appropriate interpolation method, we evaluated three widely used approaches Nearest Neighbor Interpolation, Bilinear Interpolation, and Inverse Distance Weighting. These methods were tested on snow depth and snowmelt data, with results showing excellent agreement between the interpolated and original data. Specifically, both snow depth and snowmelt achieved very high accuracy (R2 > 0.968 for snow depth and R2 = 1.0 for snowmelt), and errors remained low (RMSE approximately 3.52–3.58 mm for snow depth and 0.10–0.11 mm for snowmelt) (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The performance differences among the methods were not substantial, indicating that all are well-suited for this study area. Based on considerations of physical conservatism (preserving original pixel values and avoiding non-physical interpolation results), numerical stability, and computational efficiency for processing large-scale datasets, we ultimately selected the Nearest Neighbor Interpolation method for spatial resampling.

Figure 2.

Performance of three spatial interpolation methods (Nearest Neighbor, Bilinear, Inverse Distance Weighting) for snow depth from ERA5-Land over the Songhua River Basin (1961–2020).

Figure 3.

Performance of three spatial interpolation methods (Nearest Neighbor, Bilinear, Inverse Distance Weighting) for snowmelt from ERA5-Land over the Songhua River Basin (1961–2020).

Thereafter, rainfall was separated from the precipitation based on the condition that the daily mean temperature exceeds 0 °C, and the Accumulative Rainfall (ARF) during snowmelt events was calculated. Meanwhile, other indicators that may play potential physical roles during the snowmelt process, including Mean Snow Depth (MSD), Mean Relative Humidity (MRHU), Mean Wind Speed (MWS), Accumulative Maximum Positive Temperature (AMPT), and Accumulative Sunshine Duration (ASSD) were extracted during the events. MSD directly reflects snow storage and is a fundamental variable that determines snowmelt potential, playing an important controlling role in snowmelt runoff [10]. ARF occurring above 0 °C constitutes rain-on-snow events, which can significantly accelerate snowmelt and potentially trigger floods [27]. MWS affects the surface energy balance by modulating turbulent exchange and sensible heat flux over the snowpack [28]. AMPT directly represents heat accumulation during snowmelt and is a key driver of snow phase change [10,27]. ASSD represents solar radiative energy input that directly heats and ablates the snow cover [28]. MRHU indirectly regulates the energy consumption of snowmelt by influencing latent heat flux and sublimation or condensation processes at the snow surface [10].

2.3.3. Trend Analysis

This study employed the Thiel-Sen test to calculate the change trends of annual and monthly snowmelt in the SRB from 1961 to 2020, and used the Mann–Kendall test to analyze the significance of these trends. The combination of the Thiel–Sen test and the Mann–Kendall test is commonly used for trend analysis of long-term hydrological time series [29,30,31]. Based on the Thiel-Sen test [32], the slope β is calculated as follows:

where xi and xj are the values of the time series at time i and j, n is the number of samples. β > 0 indicates an upward trend in the time series, while β < 0 suggests a downward trend.

The Mann–Kendall test is a nonparametric method for detecting trends, developed by Mann and Kendall [33,34]. It determines whether a time series exhibits a statistically significant trend and assesses whether the trend is increasing or decreasing. The method evaluates trends by comparing all pairs of data points, generates a statistic S, and computes a Z-value based on S and its standard deviation to determine the significance of the trend. The statistic Z is calculated using the following formula:

where n is the length of the data set. Under the null hypothesis, the data points xi are independent and randomly ordered. The statistic Z follows a standard normal distribution under the null hypothesis of no trend, with a mean of zero and variance as defined. At a significance level α, if |Z| ≥ Z1−α/2, the null hypothesis is rejected, where Z1−α/2 represents the (1−α/2) quantile of the standard normal distribution. A positive value of Z indicates an upward trend in the time series, while a negative value suggests a downward trend. At the significance level α = 0.05, if |Z| > 1.96, the trend in the series is considered statistically significant.

2.3.4. Pearson Correlation Analysis

This study employed the Pearson correlation coefficient method to analyze the correlations between the total snowmelt of snowmelt events and key climatic factors (MSD, ARF, AMPT, ASSD, MRHU, and MWS) in the SRB from 1961 to 2020. The Pearson correlation coefficient is a classical statistic for measuring the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables [35,36]. The formula for calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient r is as follows:

where, xi and yi represent paired observations. and ȳ denote the sample means of variables x and y, n is the sample size. |rxy| ∈ [0, 1], The larger the value, the stronger the correlation; Otherwise, it is weaker.

2.3.5. Partial Correlation Analysis

This study utilized Partial Correlation Analysis to assess the net relationship between specific climatic variables and total snowmelt of snowmelt events, after controlling for the influence of other meteorological factors. Partial correlation coefficient is an indicator that measures the direct linear correlation between certain variables under the control of other variables [37]. The formula for calculating the partial correlation coefficient rXYZ between variables X and Y while controlling for variable Z is as follows:

where rXY, rXZ, and rYZ represent the Pearson correlation coefficients between variables X and Y, X and Z, and Y and Z, respectively. Z denotes the set of controlled meteorological variables. The partial correlation coefficient rXYZ quantifies the strength and direction of the linear relationship between X and Y after removing the linear effects of Z on both X and Y. This formula can be extended to control for multiple variables.

2.3.6. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

To compare the relative importance of different climatic factors in influencing total snowmelt of snowmelt events, Multiple regression coefficients from Multiple Linear Regression Analysis were employed. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis is a statistical technique used to model the relationship between a dependent variable and two or more independent variables [38]. The original multiple linear regression model is formulated as:

By standardizing all variables (subtracting their mean and dividing by their standard deviation), the model is transformed to

The standardized coefficient for the j-th predictor is calculated from its original coefficient βj as:

where Y represents the dependent variable, and Xj represents the j-th independent variable. βj and βjstd are the original and standardized regression coefficients for Xj, respectively. sXj and sY denote the sample standard deviations of Xj and Y. ϵ is the error term, and k is the number of predictors. The absolute value of indicates the relative influence of that variable on total snowmelt. For model fitting, data for each weather condition subset were first standardized. In subsets with no rainfall, the ARF variable was excluded due to its near-zero values and lack of explanatory power.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Snowmelt at Annual and Seasonal Scales in the SRB

3.1.1. Spatiotemporal Variability of Annual Snowmelt

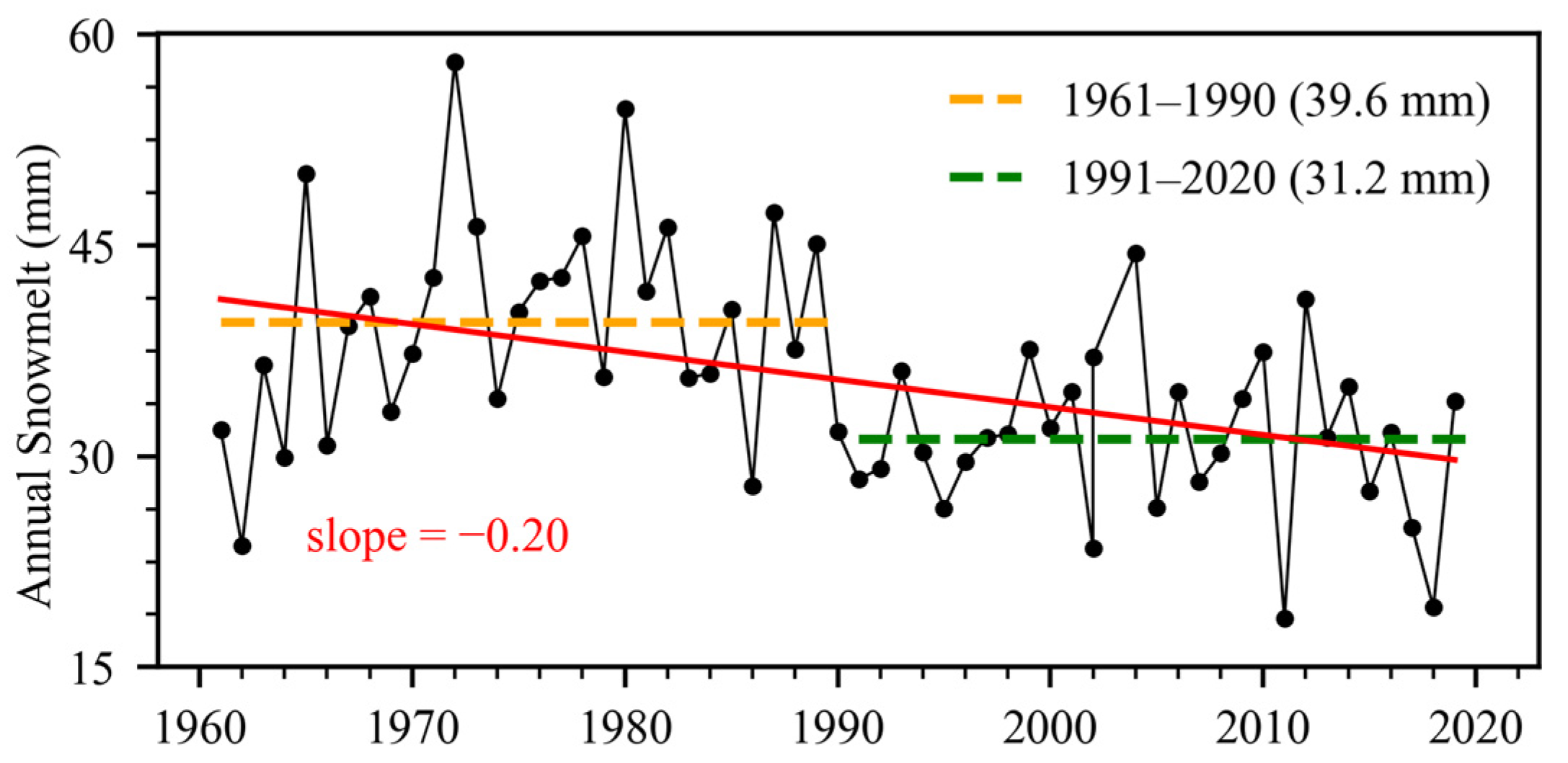

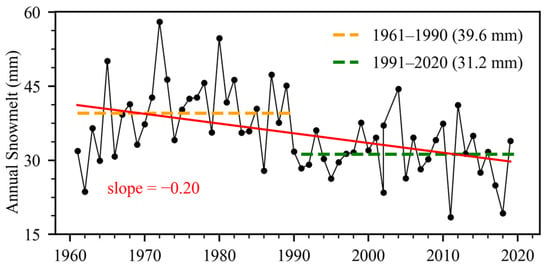

Annual snowmelt in the Songhua River Basin fluctuated from 18.5 mm (2011) to 58.1 mm (1972) during the period of 1961–2020, with a long-term average of 35.6 mm (Figure 4). A significant decreasing trend was identified in the annual snowmelt of the basin at a rate of −0.19 mm/a (p < 0.05). The average annual snowmelt decreased from 39.6 mm (1961–1990) to 31.2 mm (1991–2020), indicating a reduction of 21.2%.

Figure 4.

Temporal trend of annual snowmelt during 1961–2020.

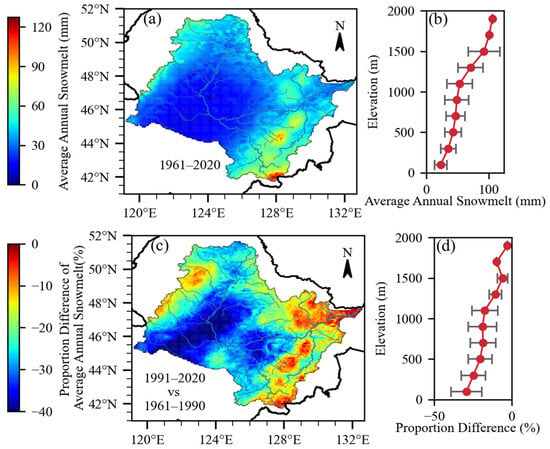

Spatially, the long-term (1961–2020) average snowmelt displayed substantial heterogeneity across the basin, ranging from 0.02 mm to 127.51 mm (Figure 5a). Generally, the snowmelt was lower in the central part of the basin, while higher in the northwestern and southeastern regions. This spatial distribution was strongly influenced by elevation (Figure 5b), exhibiting a significant positive correlation within the 400–1200 m and >1600 m elevation zones. Compared to the period of 1961–1990, the average snowmelt during 1991–2020 showed a basin-wide decrease ranging from 0% to 40% (Figure 5c). This decline also displayed a clear elevation dependency (Figure 5d). The most pronounced decrease was concentrated in lower elevations where inherent snowmelt was low, whereas the higher elevation zones with high snowmelt witnessed comparatively smaller reduction, weakened with increasing altitude. However, the snowmelt and its reduction were effectively uniform in the critical transition zone of 600–1200 m.

Figure 5.

(a) The spatial distribution of the annual average snowmelt and (b) its distribution with elevation in the SRB during 1961–2020. (c) Spatial distribution and (d) distribution with elevation of the proportional change in average annual snowmelt for 1991–2020 relative to 1961–1990.

3.1.2. Intra-Annual Dynamics of Snowmelt Processes

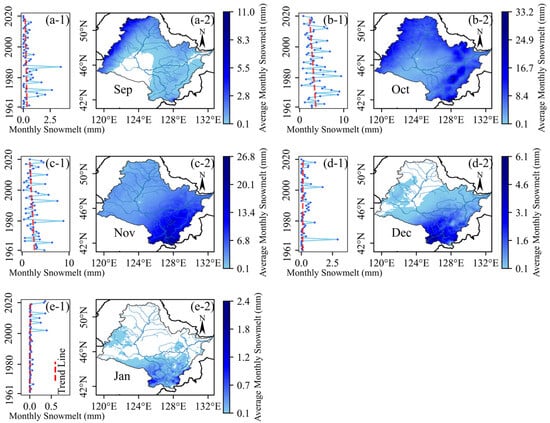

From 1961 to 2020, snowmelt in the SRB primarily occurred from September to May of the following year (Figure 6). During the SDAP, monthly snowmelt was generally low and concentrated from September to December, with long-term regional average snowmelt of 0.5 mm, 3.6 mm, 2.5 mm and 0.3 mm, respectively. The snowmelt in the SDAP mainly occurs in the northwestern Greater Khingan Range region (September), and the southeastern Changbai Mountain region (October to December) (Figure 6(b-2)–(d-2)). Almost all the months in SDAP showed a decreasing trend in the mean snowmelt of the basin during the study period (Figure 6(a-1)–(d-1)). Figure 7 shows the monthly snowmelt changes between 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 across the SRB. It can be observed that monthly snowmelt during the SDAP had a general decreasing trend, although with notable monthly and regional variations (Figure 7). The proportion of the SRB exhibiting decreased snowmelt was 74% in September, 87% in October, 52% in November, 17% in December, and only 0.3% in January. Concurrently, there was 12% and 43% of the basin that experienced increasing snowmelt in October and November, respectively, mainly observed in the northern part of the basin. A majority of the basin (54% and 77%, respectively) showed no significant change in December and January.

Figure 6.

Annual changes (a-1,b-1,c-1,d-1,e-1) and the spatial distribution (a-2,b-2,c-2,d-2,e-2) of average monthly snowmelt in SDAP (i.e., September to November, respectively) in the SRB (1961–2020).

Figure 7.

Differences in the spatial distribution of average monthly snowmelt in SDAP between 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 in the SRB.

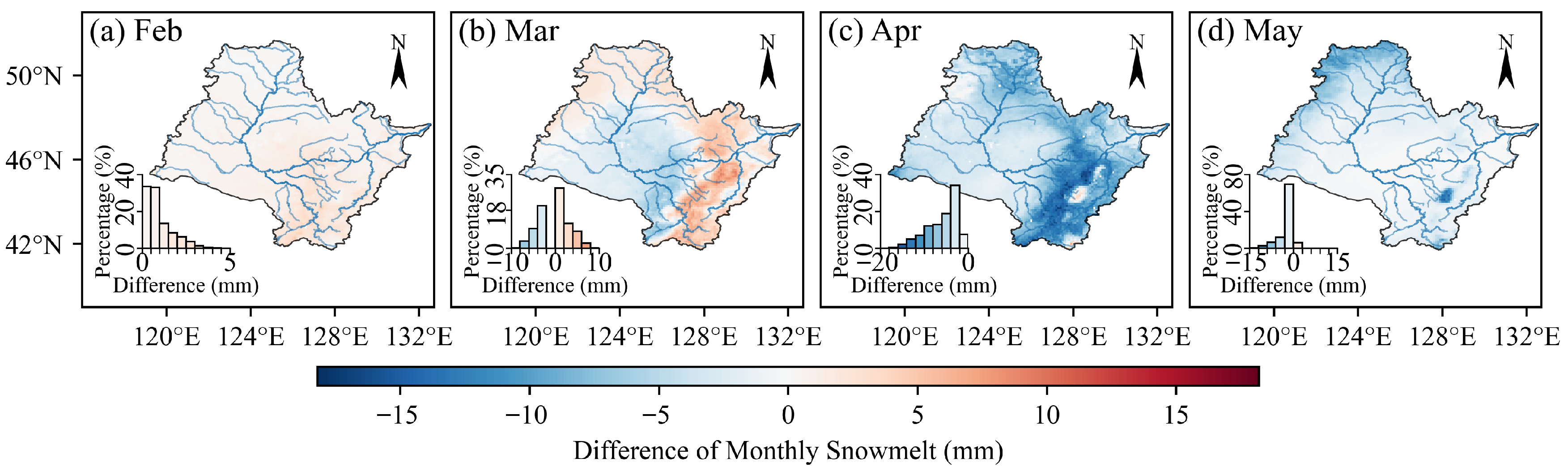

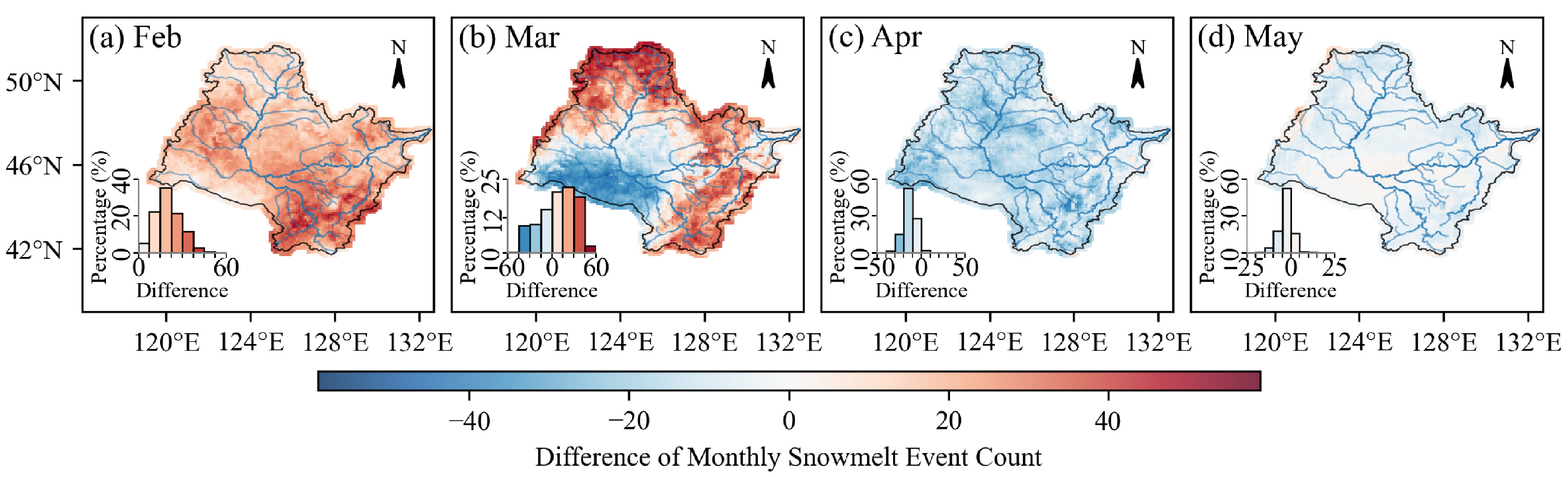

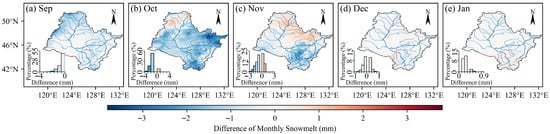

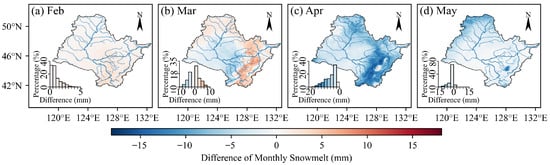

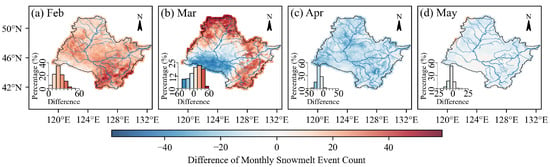

The snowmelt in SDABP was more significant than SDAP, especially in March and April, with regional average values of 9.2 mm and 15.6 mm, respectively. Spatially, the snowmelt center exhibited a clear seasonal migration. Significant melt in SDABP was first observed in February in the southeast basin (Changbai Mountain area), where the largest snowmelt reaches 10.6 mm. Throughout March, the core melting area expanded toward the northeastern parts of the basin, with a maximum monthly melt of 49.6 mm. By April, the most intense melt was predominantly concentrated in the northwestern (Greater and Lesser Khingan Ranges) and southeastern (Changbai Mountain) highlands. (Figure 8(c-2,d-2)). Basin-scale average snowmelt exhibited a statistically significant increasing trend in both February and March, with the increasing rates of 0.007 mm/a and 0.013 mm/a, respectively. However, snowmelt in April and May exhibited significant decreases, with rates of −0.058 mm/a and −0.012 mm/a, respectively (Figure 8(c-1,d-1)). Monthly snowmelt changes between 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 were pronounced and spatially diverse during the SDABP (Figure 9). The ablation season was marked by a strong early melt pulse, with snowmelt increasing across 99.5% of the basin in February and 53% in March. The increasing snowmelt in March was mainly located in the northwestern and southeastern basins, with a maximum rise of 9.6 mm. This earlier and intensified melt likely contributed to a reduced snowpack by the late ablation period. Accordingly, April and May were characterized by widespread decreases in snowmelt, affecting 99% and 90% of the SRB area, with maximum decreases of 18.2 mm and 14.8 mm, respectively.

Figure 8.

Annual changes (a-1,b-1,c-1,d-1) and the spatial distribution (a-2,b-2,c-2,d-2) of average monthly snowmelt in SDABP (i.e., from February to May, respectively) in the SRB (1961–2020).

Figure 9.

Differences in the spatial distribution of average monthly snowmelt in SDABP between 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 in the SRB.

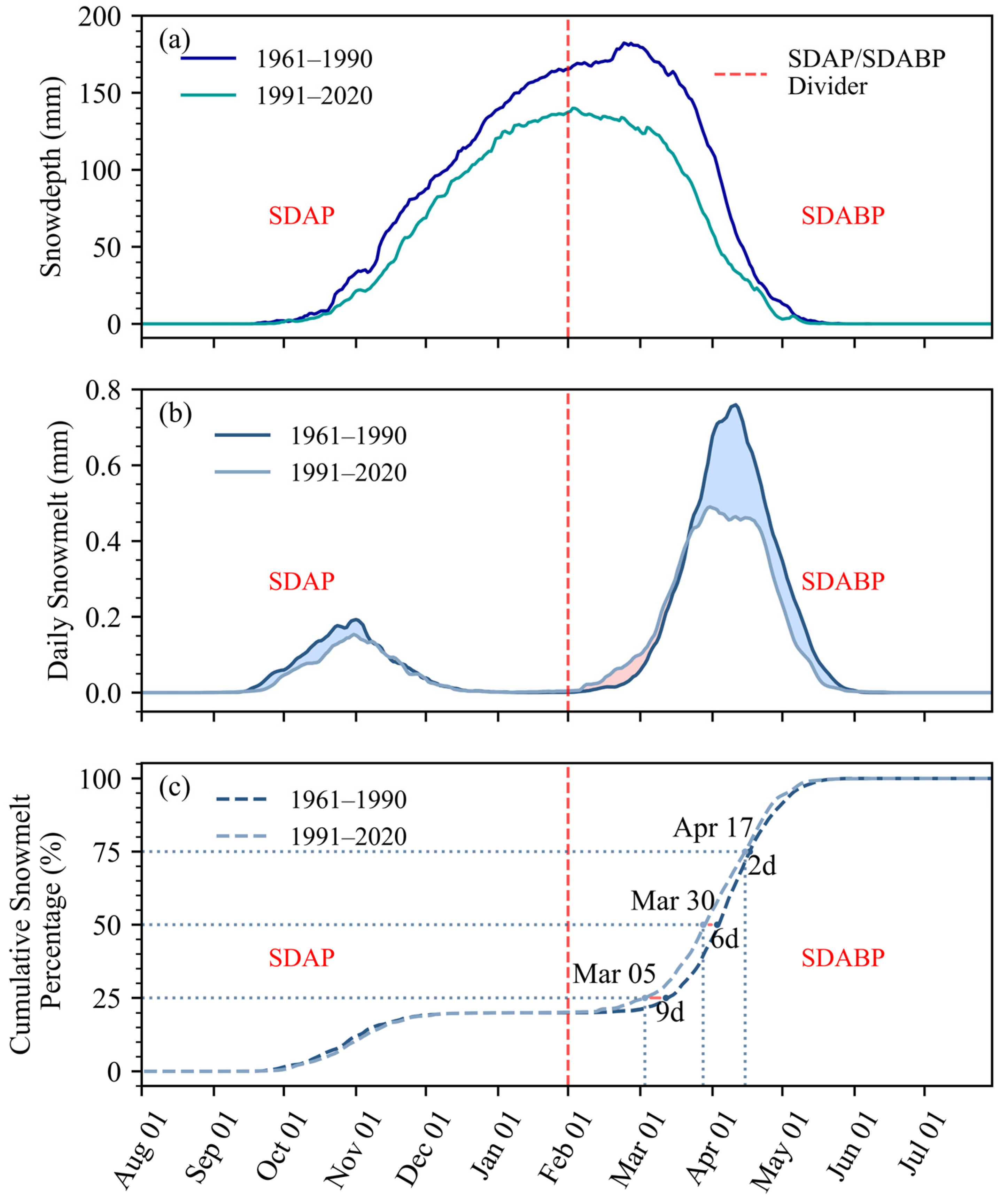

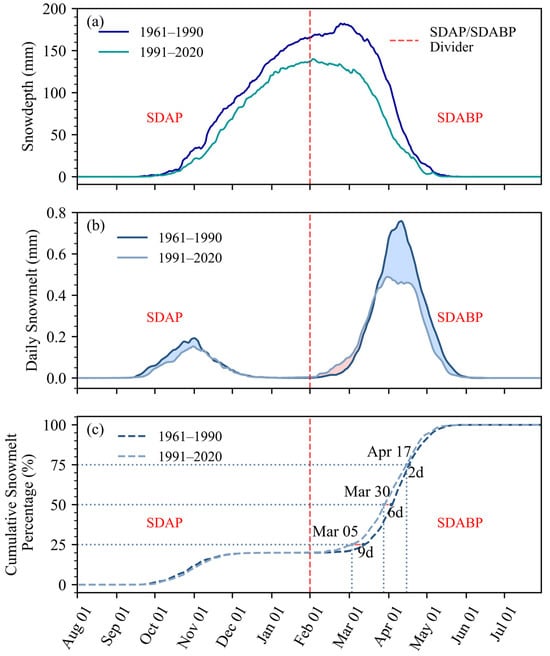

A comparative analysis of daily snow characteristics in the Songhua River Basin (SRB) also reveals substantial shifts between 1991–2020 and the 1961–1990 baseline (Figure 10a). The snow onset date shifted earlier from September 18 to 16, while the last snow cover date was delayed from May 27 to June 8. The date of maximum snow depth also advanced notably from February 23 to February 1, accompanied by a 23% reduction in depth, from 182.32 mm to 139.99 mm (Figure 10a). These seasonal changes correspond to altered snowmelt patterns (Figure 10b). Average daily snowmelt showed a decrease during the SDAP, especially from mid-September to early November, with a maximum reduction of 0.14 mm (Figure 10b). Daily snowmelt during the SDABP exhibited a more significant decrease in April and May, with a maximum value of 0.49 mm. However, a general increase in February and March was observed, with a maximum rise of 0.15 mm (Figure 10b). Consequently, the seasonal progression of cumulative snowmelt showed a clear advance, with the timings of 25%, 50%, and 75% completion occurring 9, 6, and 2 days earlier, respectively (Figure 10c).

Figure 10.

Differences in snowdepth (a), daily snowmelt (b) and cumulative snowmelt percentage (c) between the periods 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 for the hydrological year (1 August to 31 July) in the SRB.

3.2. Changing Characteristics of Snowmelt Events in the SRB

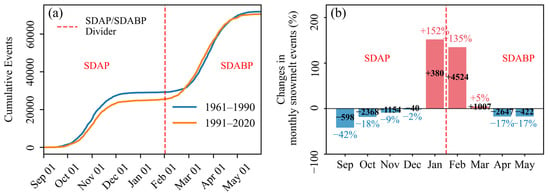

3.2.1. Changes in the Frequency of Snowmelt Events

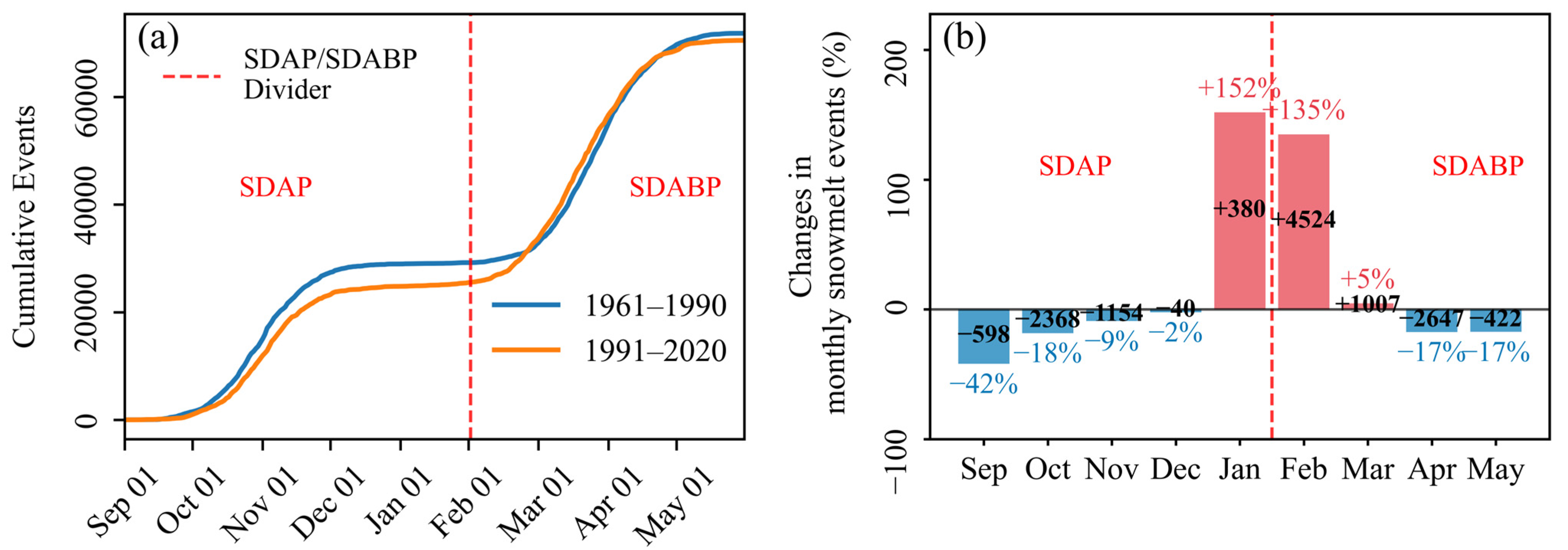

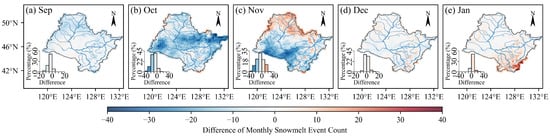

The long-term average annual cumulative snowmelt events during 1961–1990 and 1991–2020 were 71,835 and 70,542, respectively, indicating an overall slight decreasing trend (Figure 11a). In addition, noticeable shifts in the intra-annual distribution of the snowmelt events were identified between the two periods. Specifically, the early SDAP (i.e., September to December) and late SDABP (i.e., April to May) experienced widespread declines, with the most pronounced relative reductions in September (−42%) and October (−17%) (Figure 11b). Conversely, the frequency of snowmelt events increased in the late snow accumulation period and the early snow ablation period (January–March). The most significant increases were observed in January and February, where snowmelt event frequencies more than doubled.

Figure 11.

Snowmelt anomalies in the recent period (1991–2020) relative to the baseline (1961–1990) in the SRB. (a) Cumulative snowmelt events from September to May. (b) Anomalies in monthly snowmelt events.

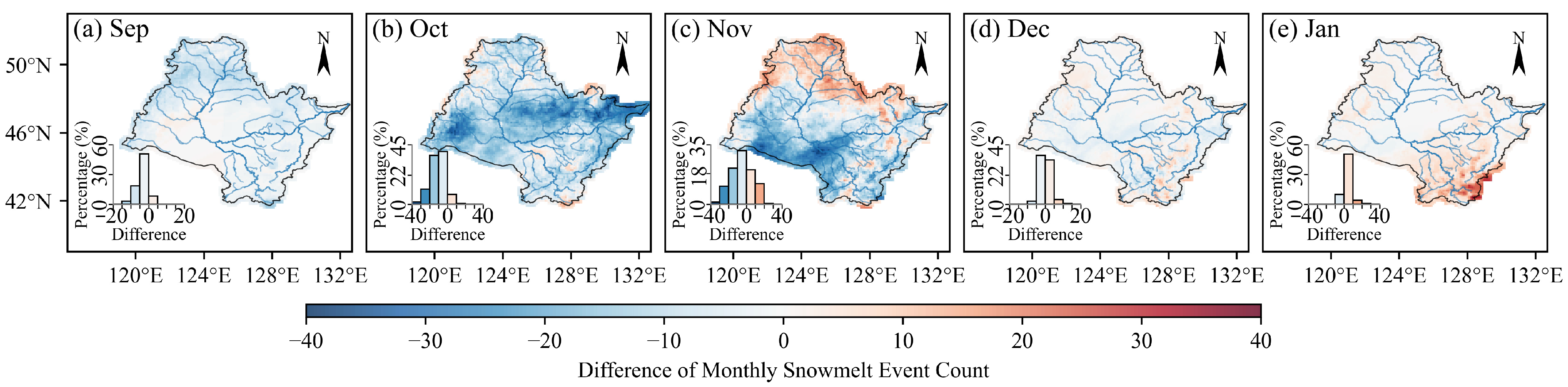

Spatially, these seasonal shifts were expressed as complex and heterogeneous patterns across the basin (Figure 12). 72%, 90%, and 65% of the basin experienced decreases in snowmelt event frequency in September, October, and November, respectively, with maximum decreases of 17, 40, and 38 events/a (Figure 12a–c). Although this decreasing trend prevailed, November displayed a distinct north-south divergence, with the south (65%) experiencing widespread declines while the northern basin (34%) saw an increase in event frequency (Figure 12d). During the late SDAP (January) and the early SDABP (February, March), which corresponds to the period of maximum snow depth (Figure 7a), the frequency of snowmelt events generally increased. The areas experiencing an increase accounted for 55%, 99%, and 65% of the basin area, respectively, with maximum increases of 37, 54, and 59 events/a (Figure 12e and Figure 13a,b). In March, areas of decrease were primarily concentrated in the southeast and northwest, but 34% of the area in the central part showed a decrease, with a maximum decrease of 52 events/a (Figure 13b). 97% and 75% of the basin showed a decrease in the frequency of snowmelt events during the late SDABP (i.e., April, May), with localized maximum decreases of 46 and 22 events/a (Figure 13c,d), respectively. Notably, increases in snowmelt events in May were also observed in the basin, especially in the high-elevation areas of the northwestern and southeastern parts (Figure 13d).

Figure 12.

Differences in the spatial distribution of average monthly snowmelt events in SDAP between 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 in the SRB.

Figure 13.

Differences in the spatial distribution of average monthly snowmelt events in SDABP between 1991–2020 and 1961–1990 in the SRB.

3.2.2. Shifts in Event Magnitude and Duration

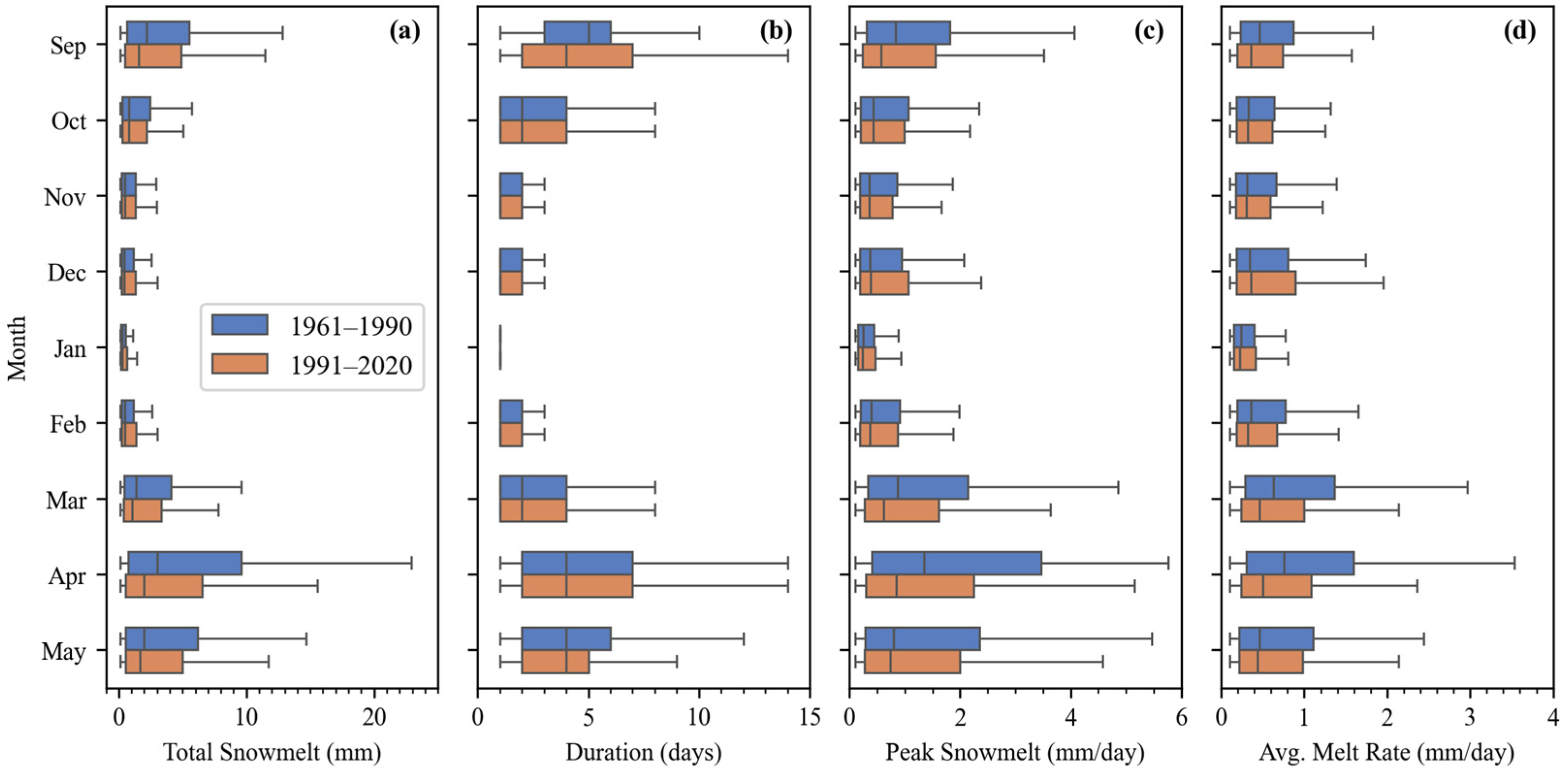

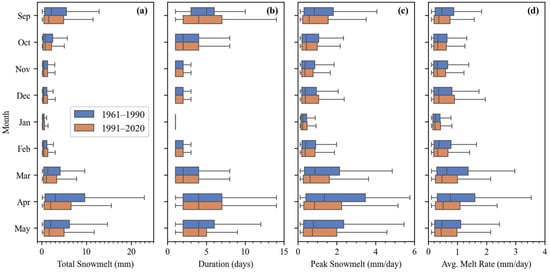

Figure 14a–d present the ranges of TSM, SMD, PDSM, and MSMR of snowmelt events occurring from September to the following May during the two periods of 1961–1990 and 1991–2020.

Figure 14.

Box Plots of snowmelt event metrics (September–May). (a) Total Snowmelt (TSM), (b) Snowmelt Duration (SMD), (c) Peak Daily Snowmelt (PDSM), and (d) Mean Snowmelt Rate (MSMR) for 1961–1990 and 1991–2020.

A clear seasonal pattern was observed in TSM, with the highest values typically occurring in September of SDAP and March-May of SDABP. Compared to 1961–1990, the event TSM showed a significant decrease in these months during 1991–2020, with median values decreasing by 32% in September (from 2.2 mm to 1.5 mm), 21% in March (from 1.4 mm to 1.1 mm), 33% in April (from 3.0 mm to 2.0 mm), and 15% in May (from 2.0 mm to 1.7 mm), respectively. In contrast, TSM from October to February remained consistently low (medians: 0.3 to 0.8 mm) and showed negligible change between periods.

Snowmelt event duration (SMD) was generally longer in the early SDAP (September-October) and late SDABP (April-May) stages of the snow season. Compared to 1961–1990, a notable shift in SMD was observed during 1991–2020, specifically in September, where the median duration shortened from 5 to 4 days, yet the maximum duration increased from 10 to 14 days. However, event durations in other months are remarkably stable across the two periods, with median values of 1–2 days in October–March and 3–4 days in April and May.

Peak and average snowmelt rates exhibited similar seasonal patterns in the Songhua River Basin, with larger values concentrated in the early SDAP (i.e., September) and the main SDABP (March–May). The seasonal pattern remained congruent across the two periods, but the 1991–2020 period was marked by a pronounced downward shift in September and across the SDABP. The PDSM and MSMR declined respectively from 0.8 to 0.6 mm/day and from 0.5 to 0.4 mm/day in September. The most severe declines of snowmelt rates in the SDABP were observed in April (PDSM, −38%; MSMR, −33%). Rates across October to January remained largely unchanged between periods, except for December, where PDSM and MSMR have increased by 3.85% and 4.05%, respectively.

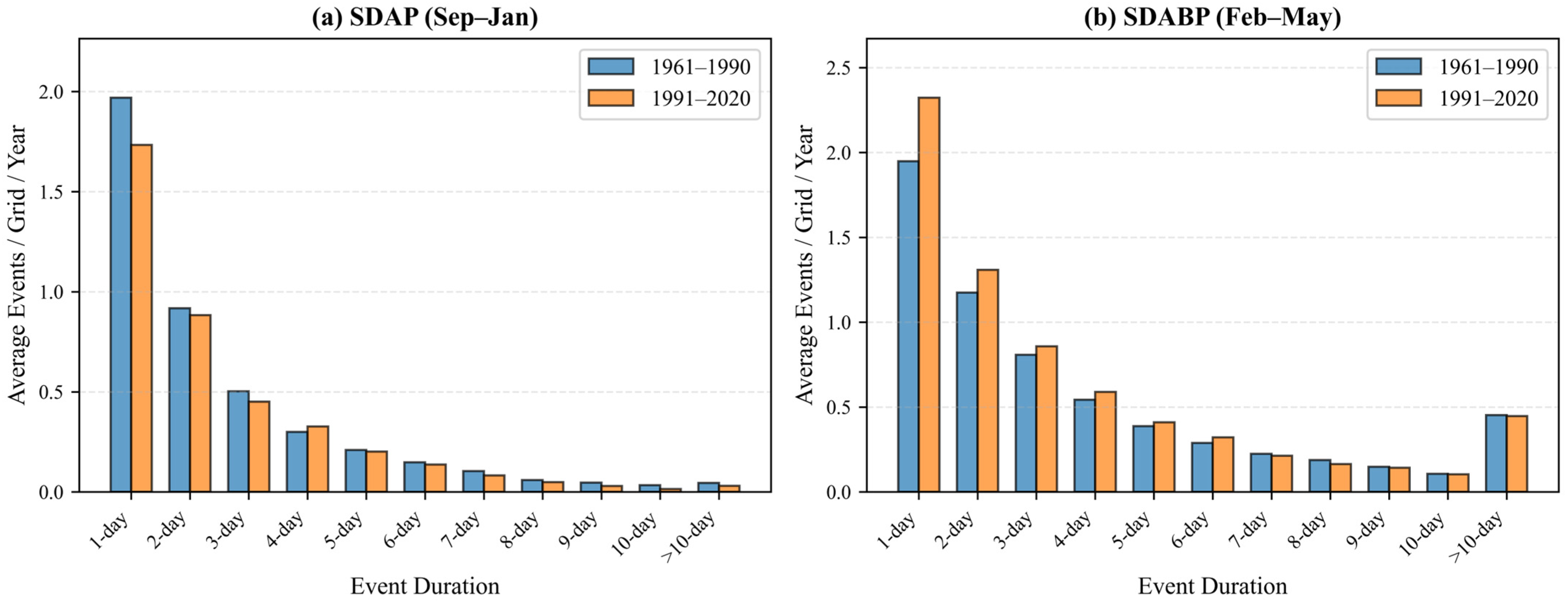

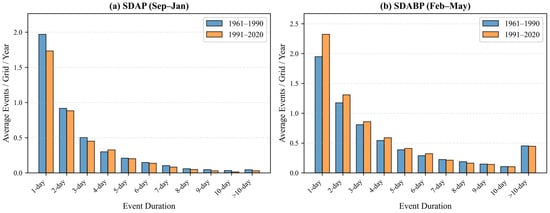

A comparative analysis between the periods 1961–1990 and 1991–2020 reveals significant changes in the number and distribution of snowmelt events with varying durations in the SRB, along with marked seasonal differences (Figure 15). During the SDAP (Sep to Jan), the annual average number of snowmelt events per grid cell decreased from 4.34 to 3.94, a decline of 9.2%. Most event durations showed a reduction, with the most pronounced decreases observed in longer-duration events. Ten-day events fell by 57.0%, from 0.03 to 0.01 events per grid cell per year, nine-day events decreased by 36.3% from 0.05 to 0.03, and seven-day events declined by 20.8% from 0.10 to 0.08. Among shorter events, one-day events decreased by 12.0% from 1.97 to 1.73, and three-day events dropped by 10.3% from 0.50 to 0.45. The only exception was four-day events, which increased slightly by 9.1% from 0.30 to 0.33. Overall, this period was characterized by a reduction in snowmelt events, particularly a sharp decline in longer-duration events. In contrast, during the SDABP (Feb to May), the annual average number of snowmelt events per grid cell increased from 6.27 to 6.88, a rise of 9.8%. This change was dominated by a significant increase in short-duration events. One-day events increased substantially by 19.2% from 1.95 to 2.32, two-day events rose by 11.4% from 1.17 to 1.31, and six-day events grew by 11.2% from 0.29 to 0.32. Meanwhile, longer-duration events (seven days or more) generally decreased, with eight-day events declining by 12.4% from 0.19 to 0.16. In summary, the SDABP period experienced an overall increase in snowmelt events, driven mainly by more frequent but shorter-duration events (1–6 days), whereas longer-duration events slightly decreased or remained stable, indicating a trend toward more frequent and shorter snowmelt processes in this season.

Figure 15.

Comparison of snowmelt event frequency and duration in the SRB between 1961–1990 and 1991–2020 by season (SDAP and SDABP).

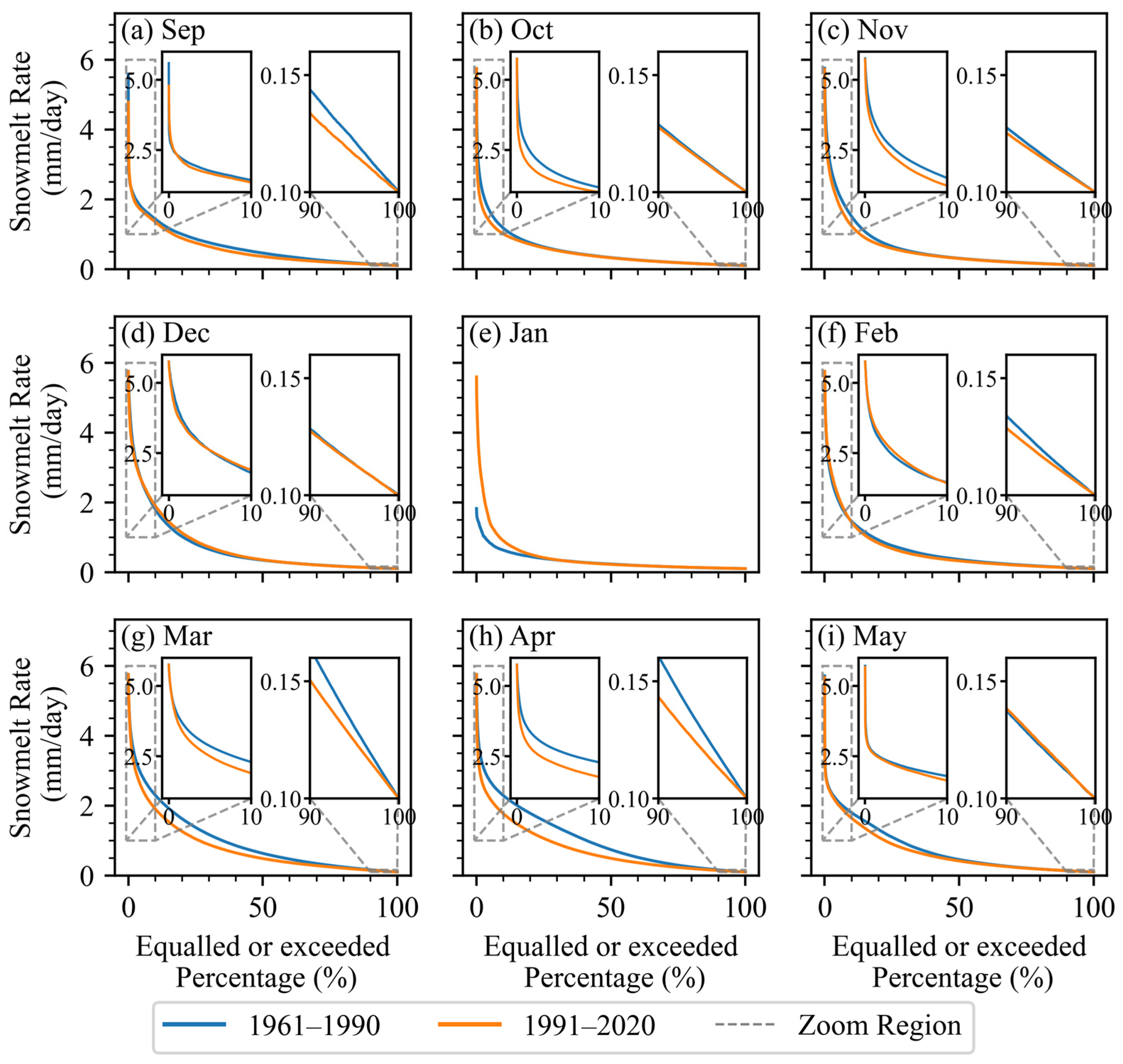

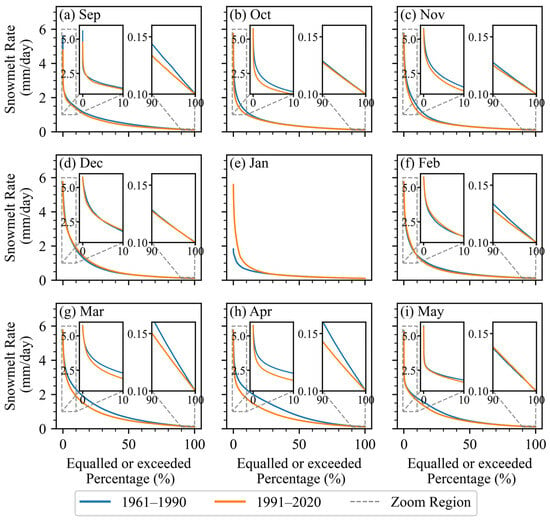

Figure 16a–i shows the changes of snowmelt regimes indicated by MSMR between periods of 1961–1990 and 1991–2020. It can be found that the shifts in MSMR were characterized by distinct monthly signatures. General attenuation in events with melt rates for all percentages was identified across the early and late snow season (September–November and March–May). However, event melt rates displayed a more complex redistribution in winter months. Specifically, January underwent a broad intensification in snowmelt rates across all percentiles, particularly for events above the 80th percentile, increasing by up to 3.8 mm/day. December and February exhibited a decrease in mid and high-rate events (above the 50th percentiles) and a slight increase in low-rate events (below the 10th percentiles), indicating a shift in the characteristics of winter melt events.

Figure 16.

Duration Curves of Mean Snowmelt Rate (MSMR) in different months from September to May for the Periods 1961–1990 and 1991–2020.

3.3. Dominant Climatic Drivers of Event Total Snowmelt

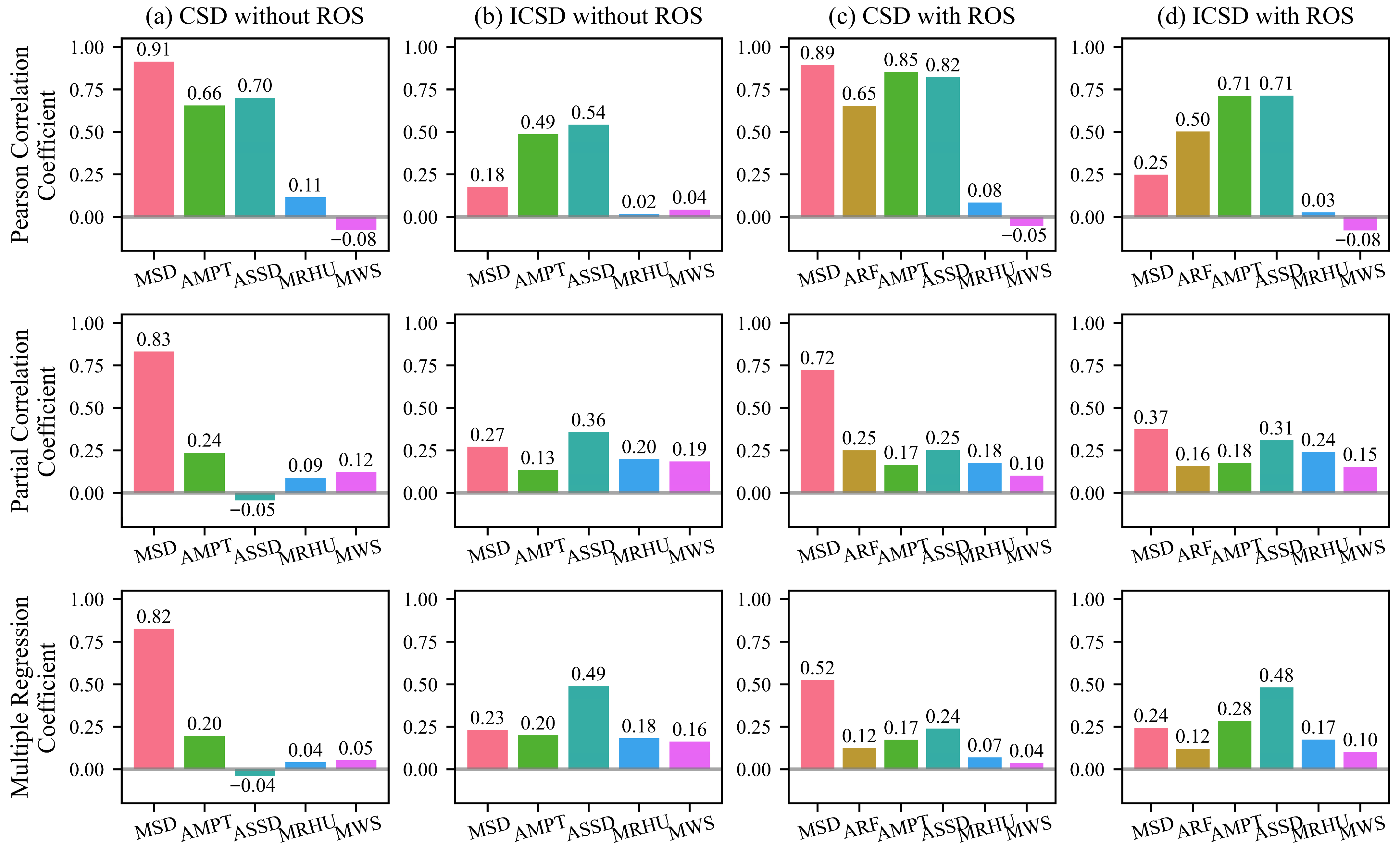

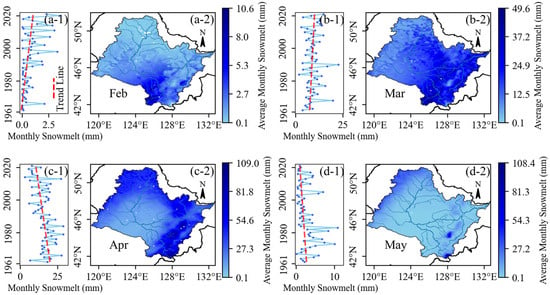

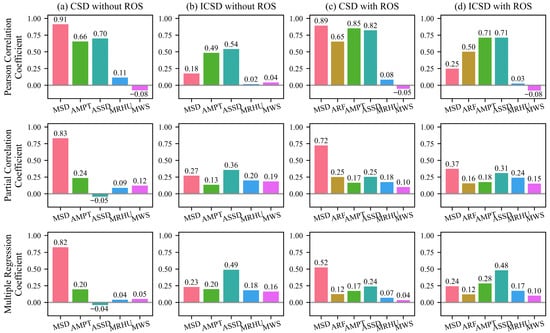

Based on comprehensive statistical analyses of 680,070 snowmelt events identified across 1050 grid points (1961–2020), the associations between key drivers and four event types were evaluated using Pearson correlation, partial correlation, and multiple regression. The results reveal distinct statistical patterns for Complete (CSD) and Incomplete (ICSD) Snow Depletion events, with and without Rain-on-Snow (ROS), and highlight critical contrasts between statistical methods (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Comparison of Pearson Correlation, Partial Correlation, and Multiple Regression Coefficients between Total Snowmelt (TSM) and Climatic Factors for the Four Snowmelt Event Types. (a) Complete Snow Depletion (CSD) without Rain-on-Snow (ROS). (b) Incomplete Snow Depletion (ICSD) without ROS. (c) CSD with ROS. (d) ICSD with ROS. Climatic factors include Mean Snow Depth (MSD), Accumulative Rainfall (ARF), Accumulative Maximum Positive Temperature (AMPT), Accumulated Sunshine Duration (ASSD), Mean Relative Humidity (MRHU), and Mean Wind Speed (MWS).

For CSD without ROS events (57.4%), Mean Snow Depth (MSD) exhibited the strongest association. It showed a very high Pearson correlation (r = 0.91), which remained strongly significant in both partial correlation (0.83) and multiple regression coefficients (β = 0.82). This consistent pattern indicates that for events culminating in full ablation, the initial snowpack mass is the foremost statistical determinant of melt characteristics, with other factors playing secondary roles. Notably, while Accumulative Maximum Positive Temperature (AMPT) and Accumulative Sunshine Duration (ASSD) showed substantial Pearson correlations (0.66 and 0.70), their independent associations diminished markedly when controlling for covariates, as shown by their lower partial correlations and β coefficients. This suggests their strong bivariate relationships are partly mediated by or confounded with snow depth.

For ICSD without ROS events (25.2%), the statistical pattern differed. MSD showed only a weak Pearson correlation (0.18) but a stronger positive partial correlation (0.27) and β (0.23), indicating its positive association becomes clearer when isolating it from other meteorological influences. ASSD emerged as the most consistent and strong predictor across all three metrics (r = 0.54, partial = 0.36, β = 0.49), suggesting solar radiation is closely associated with partial melt events where energy limitation may prevent full depletion. Variables like Mean Relative Humidity (MRHU) and Mean Wind Speed (MWS) showed negligible simple correlations but positive partial correlations and β coefficients, revealing their potential supportive role, which is masked in bivariate analysis but discernible in a multivariate context.

For CSD with ROS events, MSD remained the factor with the strongest association, though its standardized coefficient was attenuated compared to dry events (β = 0.52). Accumulative Rainfall (ARF) showed a moderate Pearson correlation (0.65) but more modest independent associations (partial = 0.25, β =0.12), indicating that while rainfall co-occurs with complete ablation, its unique contribution is secondary to the available snowpack. AMPT and ASSD maintained strong simple correlations but saw reduced independent effects in the multivariate models.

For the rarest ICSD with ROS events (3.1%), ASSD emerged with the strongest independent association (β = 0.48), followed by AMPT (β = 0.28). MSD showed a modest relationship that strengthened in partial correlation analysis (0.37), while ARF’s unique contribution appeared limited (β = 0.12). This pattern implies that for interrupted melt periods with concurrent rainfall, the process is most strongly associated with energy-related variables (sunshine and temperature) rather than primarily with initial mass or rainfall amount.

Cross-method comparison underscores that simple correlation can overestimate the apparent strength of meteorological drivers like temperature and sunshine, especially for CSD events, due to their co-variation with snow depth. Partial correlation and regression coefficients, which account for inter-variable relationships, provide a clearer view of each factor’s unique contribution. This is evident for humidity and wind, which consistently showed near-zero simple correlations but non-negligible positive partial correlations and β weights across event types, indicating a consistent, though minor, facilitative association that is revealed only after accounting for dominant factors.

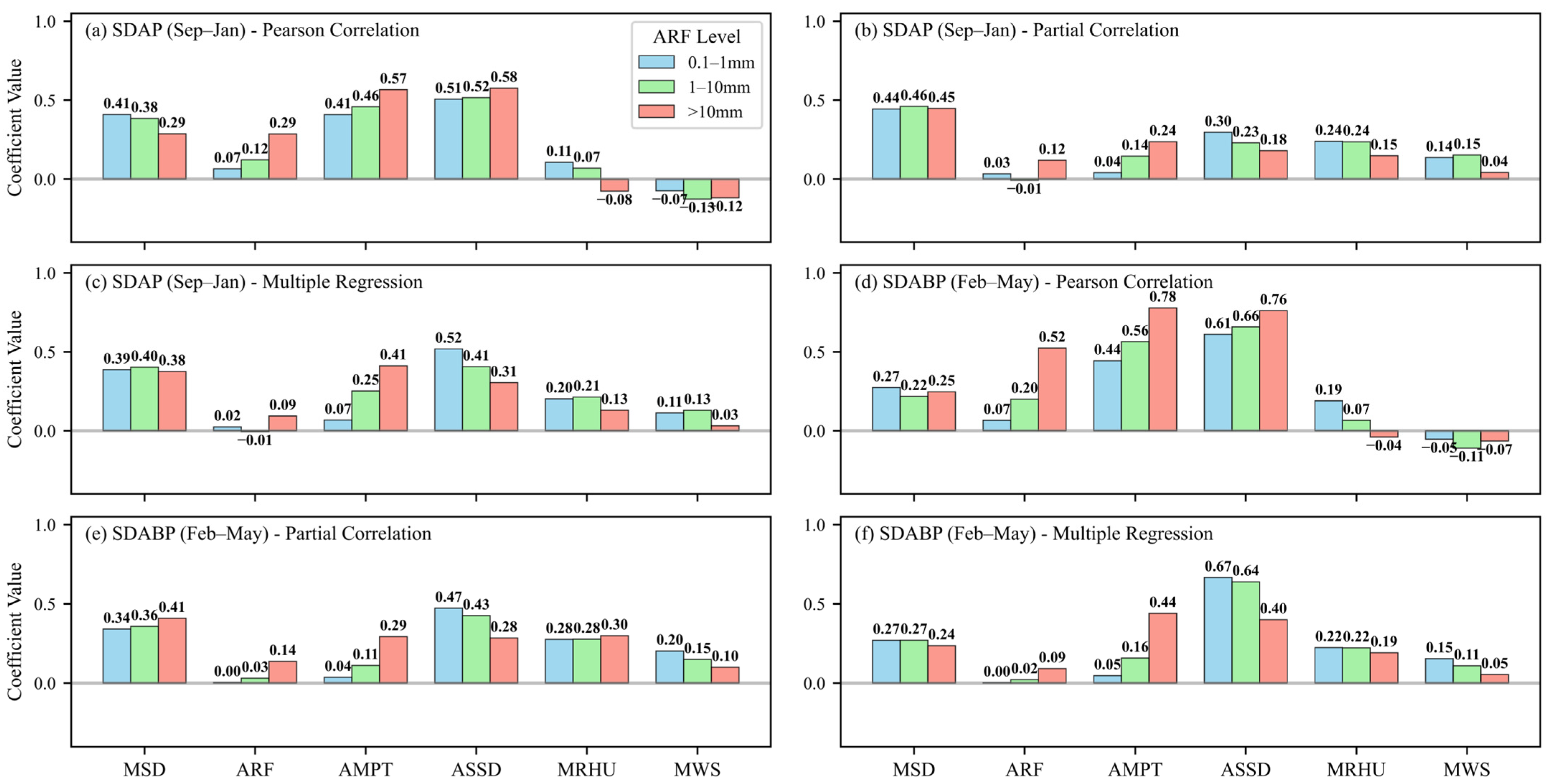

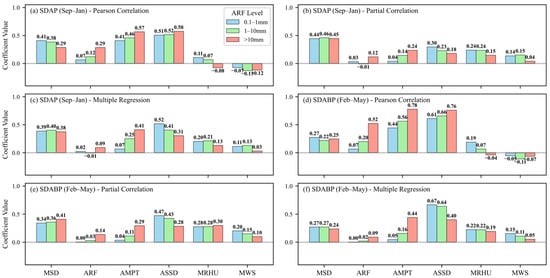

Stratified analysis of ROSm events further indicates that the association of cumulative rainfall is modulated by both seasonal timing and rainfall amount (Figure 18). During the Snow Depth Accumulation Period (SDAP, Sep–Jan), rainfall contributed minimally to melt across all intensities, with negligible β coefficients for ARF (ranging from −0.006 to 0.09). This suggests autumn/winter rainfall energy is likely consumed in warming the cold snowpack. During the Snow Depth Ablation Period (SDABP, Feb-May), the association strengthened only for heavy rain (>10 mm), with Pearson correlation for ARF reaching 0.52. However, multivariate analysis showed its independent association remained moderate (partial = 0.14, β = 0.09), indicating high-intensity spring rainfall occurs within weather systems that also bring significant sensible heat (high AMPT) and modulate radiation (ASSD).

Figure 18.

Stratified analysis of ROSm events. Effects of Mean Snow Depth (MSD), Accumulative Rainfall (ARF), Accumulative Maximum Positive Temperature (AMPT), Accumulated Sunshine Duration (ASSD), Mean Relative Humidity (MRHU) and Mean Wind Speed (MWS) across seasons (SDAP: September–January, SDABP: February–May) and rainfall intensity classes (0.1–1 mm, 1–10 mm, >10 mm).

Across all ROSm events strata, ASSD was the most robust and strongly associated predictor, with β coefficients consistently the highest (peaking at 0.67). This underscores solar radiation’s primary statistical association with melt energy, even during rainfall. AMPT also showed strong bivariate and independent associations, particularly for SDABP heavy rain (r = 0.78, β up to 0.44). MSD maintained a significant positive effect, especially during SDAP, with its role as a fundamental mass control often clarified in partial correlation analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Elevational Dependency in the Snowmelt Response to Climate Warming

Anthropogenic warming has triggered widespread declines in snow cover extent and duration [39,40]. Although the overall decreasing trend in snowmelt across China is not significant [41], our study reveals a significant reduction in annual snowmelt within the SRB from 1961 to 2020. This underscores the importance of regional-scale assessments and can be primarily attributed to the pronounced warming in the basin [18,19], which leads to a decrease in snow accumulation and consequently the available mass for melt. The magnitude of this reduction exhibits a clear elevation dependence. The most pronounced declines occurred at lower elevations, whereas the spatial variability of the trend was minimal within the 600–1200 m range. This pattern suggests the existence of critical elevation zones where the competing influences of temperature and precipitation balance each other. Similarly, elevation thresholds, below which temperature dominates snow cover changes and above which precipitation is more influential, have been identified in other mountain systems, such as Switzerland and the Tianshan Mountains [42,43]. The attenuated reduction trend in our study’s high-elevation areas (>1600 m) aligns with this framework, potentially indicating regions where increased precipitation may partially offset warming-induced melt.

4.2. Earlier Snowmelt Onset Reconfigures the Spring Hydrograph

Consistent with observed snow cover declines, the snowmelt season in the SRB has advanced [44,45]. This study found that the dates marking 25%, 50%, and 75% of the spring cumulative snowmelt have shifted earlier by 9 days, 6 days, and 2 days, respectively. This advancement has reconfigured the spring hydrograph, manifesting as increased snowmelt in early spring (February–March) but a sharp decrease in late spring (April–May). A similar shift toward earlier snowmelt (increased in March and decreased in April) in northeastern China was also reported by Yang et al. [41]. Research indicates that snowmelt serves as a critical natural reservoir in Northeast China, contributing 66% and 33% of the runoff in April and May, respectively. This is essential for maintaining spring soil moisture; without snow cover, soil moisture from March to May is projected to decrease by at least 20% [10]. The sharp decline in late-spring snowmelt directly weakens the water supply capacity during this critical period. Spring drought is closely related to preceding snow conditions. Regions with low early-season snowpack, high temperatures, and insufficient precipitation (e.g., eastern Inner Mongolia and northwestern Liaoning) are more prone to drought [46]. In the southern Songnen Plain, winter snow depth is a key predictor of spring soil moisture and drought severity [47]. The hydrothermal conditions during the snowmelt period and snow depth during the freezing period (which suppresses soil evaporation and promotes meltwater infiltration) are important mechanisms in the formation of spring drought [48]. The warming-driven advancement of snowmelt and the reallocation of meltwater from late spring to early spring have disrupted the natural rhythm that previously relied on late-spring meltwater to alleviate spring drought. This shift may also directly threaten spring crop growth and food security by altering soil moisture conditions [10,47]. The current hydrological regime has transitioned from a stable late-spring water supply to a pattern characterized by increased early-spring meltwater and a sharp decrease in late spring, leading to a growing mismatch with agricultural water demand and potentially intensifying the risk of spring water scarcity. Therefore, future adaptation strategies must prioritize measures such as enhanced reservoir regulation and optimized irrigation to address the new challenges posed by earlier snowmelt and diminished late-spring snowmelt.

4.3. Shifting Drivers of Snowmelt Events

The characteristics of snowmelt events are regulated by snow conditions and energy inputs [10,49]. This study indicates that complete ablation events are primarily controlled by pre-event snow depth, whereas events during the residual snow period are driven synergistically by accumulated positive degree days, sunshine duration, and rain on snow. This mechanistic understanding explains the observed weakening of overall snowmelt intensity and a reduction in the frequency and rate of extreme melt events across the basin. Although this might suggest a lower risk of large-scale snowmelt floods, the increasing overlap of the spring melt season with the rainfall season could exacerbate the potential for rainfall-snowmelt compound floods [12,50,51]. Global multi-basin analyses confirm that ROS events, by simultaneously releasing rainwater and significantly accelerating snowmelt (with melt rates potentially doubling) through the advected heat, often generate flood peaks and destructive forces far exceeding those from individual factors [52,53]. Under a warming climate, the frequency of such events has shown a significant increasing trend in high-latitude regions such as western North America and central Europe [28,52]. Their core disaster-causing mechanism lies in the spatiotemporal overlap of the two key factors: “liquid precipitation” and “seasonal snowpack”. For the Songhua River Basin, the earlier snowmelt season revealed in this study essentially significantly widens the temporal overlap window between the snow-cover period and the spring heavy rainfall season. Multiple studies indicate that this overlap is key to exacerbating compound flood risks in high-latitude coastal zones (e.g., south-central Alaska) and specific elevation belts in High Mountain Asia (e.g., the mid-altitude region around 3.0–4.5 km) [28,53]. Although the causal mechanisms leading to such floods differ across continents, rainfall, snow water equivalent (SWE), soil moisture, and air temperature have been universally identified as critical drivers [52]. The formation mechanisms and future changes of these compound extremes thus constitute a critical area for future research [49,54], with direct implications for future water security, ecological stability, and disaster risk management [15].

4.4. Uncertainty and Limitations

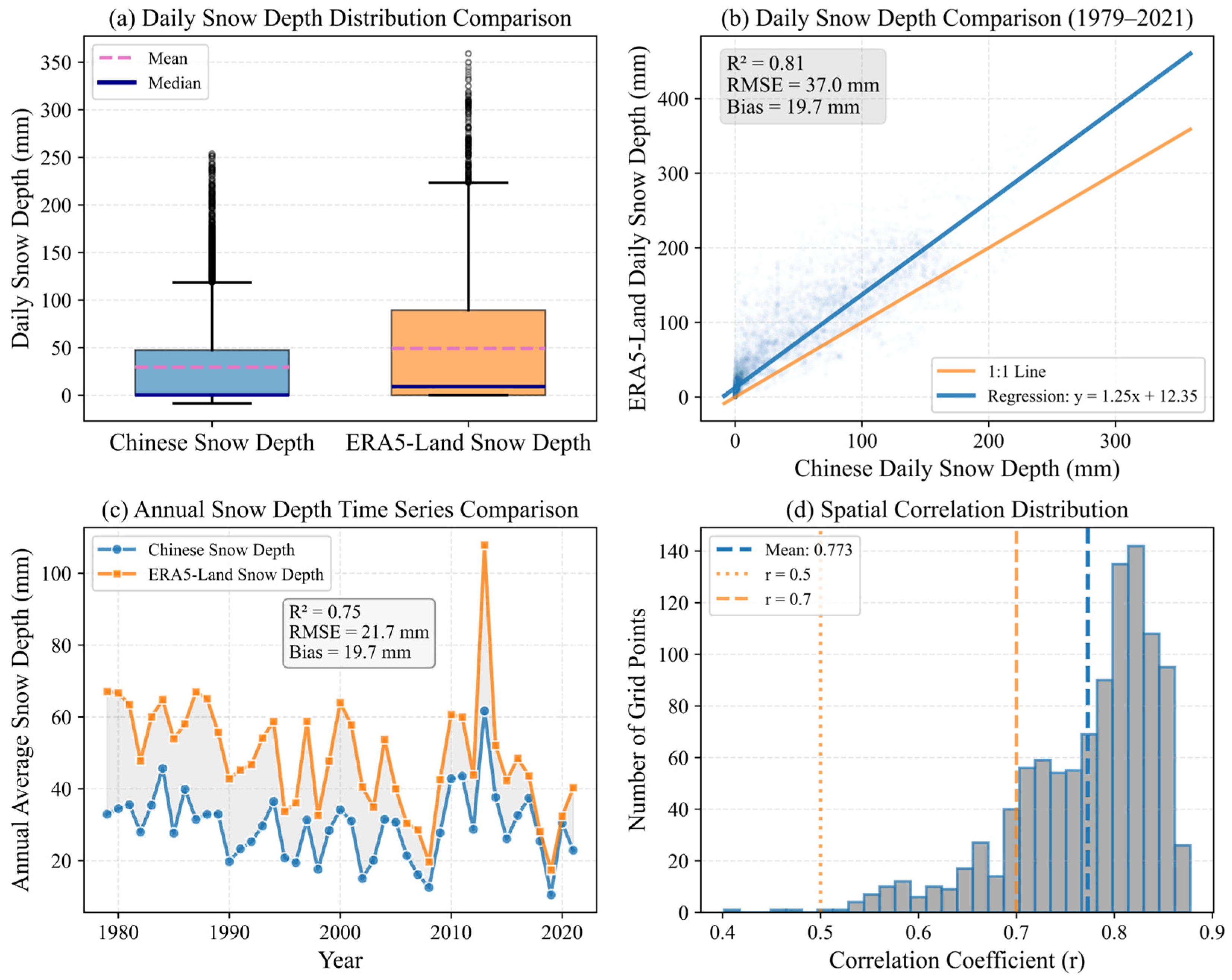

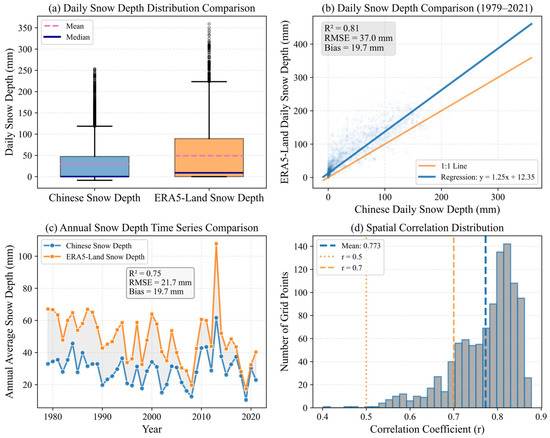

This study is subject to several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The findings regarding regional snowmelt are closely tied to the selected snow depth and snowmelt data. Considering its longer continuous record of snow depth and snowmelt data, this study employs the ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset for analysis. Validation against the independent Long-term Series of Daily Snow Depth Dataset in China reveals that ERA5-Land snow depths are systematically higher, which may lead to an overestimation of snowmelt in some regions compared to this reference dataset. Regarding the accuracy of ERA5-Land, performance varies across different regions. For instance, Li et al. also reported an overestimation on the Tibetan Plateau [10], while Ari et al. indicated that ERA5-Land tends to overestimate in North America and Asia but underestimate in Europe, highlighting its spatially dependent uncertainties [55]. Although snowmelt in the SRB may be overestimated, the ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset demonstrates strong consistency with the Chinese snow depth dataset in terms of spatiotemporal patterns. Specifically, 99.7% of grid cells show correlation coefficients above 0.5, with 85.5% exceeding 0.7 and a mean spatial correlation of 0.77 (Figure 19d). Since this study focuses more on long-term trends in snowmelt rather than absolute melt magnitudes, the ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset is considered suitable, as it effectively captures temporal trends consistent with the observational data, evidenced by high R2 values of 0.81 (Figure 19b) at the daily scale and 0.75 (Figure 19c) at the annual scale.

Figure 19.

Comparative Analysis of ERA5-Land Daily Snow Depth with the Long-term Series of Daily Snow Depth Dataset in China in the SRB (1961–2021). (a) Daily Snow Depth Distribution Comparison, (b) Daily Snow Depth Comparison, (c) Annual Snow Depth Time Series Comparison, (d) Spatial Correlation Distribution.

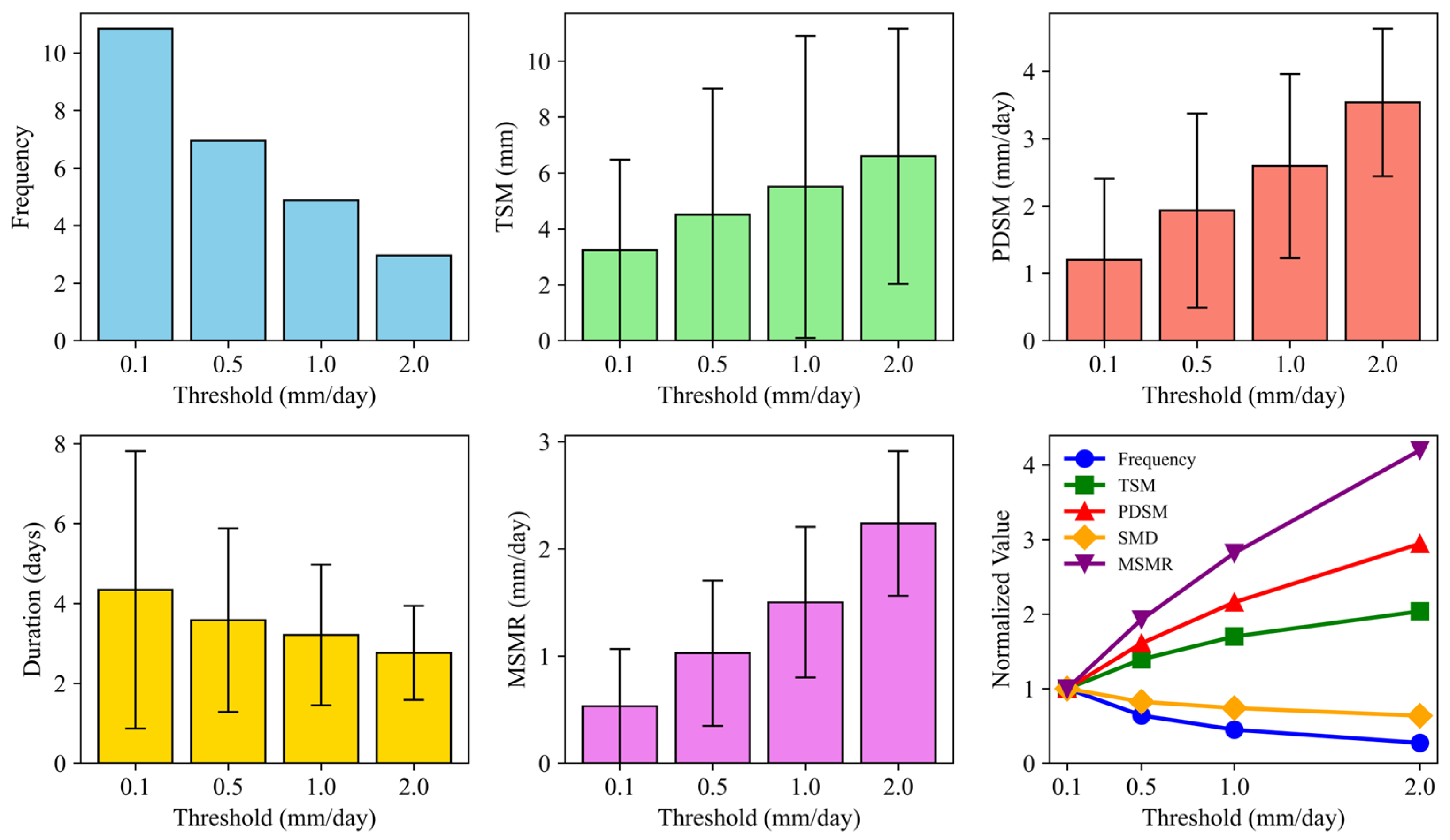

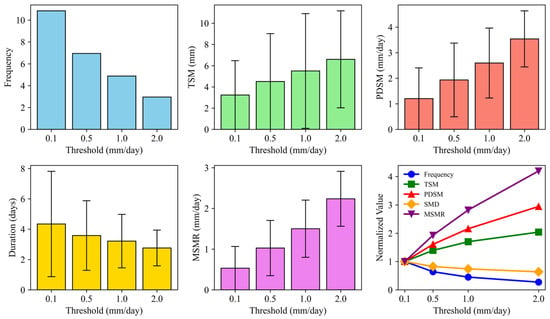

In characterizing snowmelt events, the selection of a discrimination threshold can significantly influence the extraction of event features. This study adopts a melt threshold of ≥0.1 mm/day to sensitively capture the onset of spring snowmelt and weak melt signals, thereby supporting accurate hydrological process analysis. A lower threshold helps identify a more complete sequence of events, including minor melt processes. To assess the impact of threshold selection, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by comparing thresholds of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mm/day (Figure 20). The results show that using a 0.1 mm/day threshold captures 72.8% more events than using a 2.0 mm/day threshold, indicating that a lower threshold preserves a more comprehensive picture of melt occurrences. In contrast, higher thresholds (e.g., 1.0 or 2.0 mm/day) selectively identify fewer but more intense events, which are typically associated with greater TSM, higher PDSM amounts, and faster MSMR. Therefore, lower thresholds are suitable for systematically capturing the dynamics and continuity of melt processes, while higher thresholds are more appropriate for analyzing high-intensity melt events. Ultimately, the choice of threshold should align closely with specific research objectives.

Figure 20.

Sensitivity Analysis of Snowmelt Event Statistical Characteristics to Daily Intensity Thresholds.

Furthermore, this research has focused predominantly on climatic drivers, without explicitly accounting for non-climatic factors such as land use/cover changes and vegetation dynamics, which can modulate the surface energy balance and thus the local melt rate.

To address these limitations, several directions are proposed for future work: (1) integrating multi-source data (e.g., from remote sensing and in-situ observations) with reanalysis datasets to improve the precision of snowmelt monitoring; (2) incorporating land surface models to quantify the contributions of climate change and human activities (e.g., afforestation, urbanization) to the observed alterations in the snowmelt regime; (3) projecting long-term melt trajectory and their hydrological impacts under a warming climate with process-based models; (4) elucidating the mechanisms, spatiotemporal patterns, and associated flood risks of rainfall-snowmelt compound events. Such focused studies will be indispensable for developing robust strategies for adaptive water resources management and enhanced flood disaster mitigation in the Songhua River Basin and similar snow-dominated regions.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the spatiotemporal changes and driving mechanisms of snowmelt in the SRB from 1961 to 2020. The results demonstrate a significant declining trend in annual snowmelt across the SRB, primarily attributable to reduced snowpack under climate warming. This decline in snowmelt was spatially heterogeneous and strongly elevation-dependent, being most pronounced at lower elevations and substantially attenuated above 600 m. The spring snowmelt season has advanced substantially, with the timings of cumulative melt reaching 25%, 50%, and 75% occurring 9, 6, and 2 days earlier in 1991–2020 compared to 1961–1990. Concurrently, the seasonal distribution of melt has restructured, shifting from late spring (April–May) to early spring (February–March). At the event scale, snowmelt events have weakened in intensity, with reductions in frequency, Total Snowmelt (TSM), Peak Daily Snowmelt (PDSM), and Mean Snowmelt Rate (MSMR). A general decline in both frequency and duration during September to January, versus a shift toward more frequent, shorter-duration events (1–6 days) from February to May. Despite this overall decline, the average melt rate for winter (January) events has increased significantly. Based on multivariate statistical analyses of snowmelt events, comparing Pearson correlation, partial correlation, and multiple linear regression coefficients across four event types, the strongest independent association with total snowmelt was found with mean snow depth for complete depletion events and with accumulated sunshine duration for incomplete depletion events, while Rain-on-Snow Melt events were most closely associated with accumulated sunshine duration and accumulative maximum positive temperature.

In summary, global warming has reconfigured the snowmelt regime of the SRB toward reduced volume, earlier timing, and weakened intensity. These changes are likely to significantly alter spring flood pulses, affect ecological water demand, and challenge water resource management. Future research should prioritize quantifying the cascading impacts of this shifted snowmelt regime on flood risk and ecosystem stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z.; Data curation, X.L. and W.Z.; Methodology, G.Z. and P.Q.; Formal analysis, P.Q.; Funding acquisition, F.L. (Fengping Li); Software, X.L.; Validation, F.L. (Fan Liu); Visualization, X.L.; Writing—original draft, X.L.; Writing—review and editing, F.L. (Fengping Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42471033) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, China (XDA28020501).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SRB | Songhua River Basin |

| SDAP | Snow Depth Accumulation Period |

| SDABP | Snow Depth Ablation Period |

| TSM | Total Snowmelt |

| PDSM | Peak Daily Snowmelt |

| SMD | Snowmelt Duration |

| MSMR | Mean Snowmelt Rate |

| MSD | Mean Snow Depth |

| MRHU | Mean Relative Humidity |

| MWS | Mean Wind Speed |

| ARF | Accumulative Rainfall |

| AMPT | Accumulative Maximum Positive Temperature |

| ASSD | Accumulative Sunshine Duration |

| CSD | Complete Snow Depletion |

| ICSD | Incomplete Snow Depletion |

| ROS | Rain-on-Snow |

| ROSm | Rain-on-Snow Melt |

References

- Zhang, T. Influence of the seasonal snow cover on the ground thermal regime: An overview. Rev. Geophys. 2005, 43, RG4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, J.; Zeng, X. Characteristics and causes of extreme snowmelt over the conterminous United States. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E1526–E1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.E.; Cannon, A.J.; Hinzman, L. Historical trends and extremes in boreal Alaska river basins. J. Hydrol. 2015, 527, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A.C.; Zhang, Q.; Lopez Caceres, M.L.; Murayama, H. Soil temperature and soil moisture dynamics in winter and spring under heavy snowfall conditions in North-Eastern Japan. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 3235–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; McCrary, R.R.; Jacobs, J.M. Future changes in snowpack, snowmelt, and runoff potential extremes over North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL094985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliainen, J.; Luojus, K.; Derksen, C.; Mudryk, L.; Lemmetyinen, J.; Salminen, M.; Ikonen, J.; Takala, M.; Cohen, J.; Smolander, T.; et al. Patterns and trends of Northern Hemisphere snow mass from 1980 to 2018. Nature 2020, 581, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, X.; Li, X. Spatiotemporal variation of snow depth in the Northern Hemisphere from 1992 to 2016. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, C. Hotspots of snow cover changes in global mountain regions over 2000–2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 243, 111781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Che, T.; Li, X.; Wang, N.; Yang, X. Slower snowmelt in spring along with climate warming across the Northern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 12331–12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, P.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zhang, F. Intensified warming suppressed the snowmelt in the Tiβn Plateau. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2024, 15, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wu, T.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Hu, G.; Wang, W.; Qin, Y.; Yang, S. Characteristics of the ratios of snow, rain and sleet to precipitation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau during 1961–2014. Quat. Int. 2017, 444, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotovy, O.; Nedelcev, O.; Jenicek, M. Changes in rain-on-snow events in mountain catchments in the rain-snow transition zone. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2023, 68, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surfleet, C.G.; Tullos, D. Variability in effect of climate change on rain-on-snow peak flow events in a temperate climate. J. Hydrol. 2013, 479, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; You, Q.; Smith, T.; Kelly, R.; Kang, S. Spatiotemporal dipole variations of spring snowmelt over Eurasia. Atmos. Res. 2023, 295, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Feng, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, H. Snow as an important natural reservoir for runoff and soil moisture in Northeast China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2020JD033086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wu, T.; Tang, G.; Xu, Y. Recent progress in studies of climate change in China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2012, 29, 958–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, X.; Qin, C.; Xu, X.; Lalic, B.; Ćupina, B. Dynamic changes in snowfall extremes in the Songhua River Basin, Northeastern China. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Miao, C.; Han, J. Spatiotemporal changes in temperature and precipitation over the Songhua River Basin between 1961 and 2014. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, G.; Xu, Y.J. Spatiotemporal variability of climate and streamflow in the Songhua River Basin, northeast China. J. Hydrol. 2014, 514, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, T.; Dai, L.; Li, X. Long-Term Series of Daily Snow Depth Dataset in China (1979–2024); National Tiβn Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.J.; Wu, Z.N.; Mu, X.M.; Gao, P.; Zhao, G.; Sun, W.; Gu, C. Spatiotemporal changes in snow cover over China during 1960–2013. Atmos. Res. 2019, 218, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhang, Y. Investigating snow cover duration changes based on a cloud-free snow cover product developed using a spatiotemporal cloud removal method for Northeast China. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2497520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.L.; Li, X.F.; Gu, L.J.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, T. Significant decreasing trends in snow cover and duration in Northeast China during the past 40 years from 1980 to 2020. J. Hydrol. 2023, 626, 130318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodetskaya, I.V.; Durán-Alarcón, C.; González-Herrero, S.; Clem, K.R.; Zou, X.; Rowe, P.; Imazio, P.R.; Campos, D.; Santos, C.L.-D.; Dutrievoz, N.; et al. Record-high Antarctic Peninsula temperatures and surface melt in February 2022: A compound event with an intense atmospheric river. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puggaard, A.; Hansen, N.; Mottram, R.; Nagler, T.; Scheiblauer, S.; Simonsen, S.B.; Sørensen, L.S.; Wuite, J.; Solgaard, A.M. Bias in modeled Greenland Ice Sheet melt revealed by ASCAT. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 2963–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Ebtehaj, A.; Cohen, J.; Foufoula-Georgiou, E. On risk of rain on snow over high-latitude coastal areas in North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL114775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, C.; Lu, H. The spatial and temporal distribution of rain-on-snow events and their driving factors in China. Hydrol. Process. 2025, 39, e70098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Li, H.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Du, X.; Ye, X. Identification of key influence factors and an empirical formula for spring snowmelt-runoff: A case study in mid-temperate zone of northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, L.; Lai, Z.; Tian, Q.; Liu, W.; Li, J. Innovative trend analysis of annual and seasonal air temperature and rainfall in the Yangtze River Basin, China during 1960–2015. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2017, 164, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Cao, J.; Ali, S.; Muhammad, S.; Ullah, W.; Hussain, I.; Akhtar, M.; Wu, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhou, J. Observed trends and variability of seasonal and annual precipitation in Pakistan during 1960–2016. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 8313–8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Khare, D.; Kundu, S. Spatial and temporal analysis of rainfall and temperature trend of India. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 122, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods, 4th ed.; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, C.; Xu, Z.; Zuo, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J. Vertical influence of temperature and precipitation on snow cover variability in the Yarlung Zangbo River basin, China. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Song, S.; Sun, W.; Mu, X.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Recent changes in extreme precipitation and drought over the Songhua River Basin, China, during 1960–2013. Atmos. Res. 2015, 157, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, H.W.; Ma, X.F.; Zhang, J.; Yang, R. Relationship between vegetation phenology and snow cover changes dur-ing 2001–2018 in the Qilian Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagioras, A.; Kourtidis, K. Study of the influence of local meteorology on the atmospheric potential gradi-ent. Atmos. Res. 2025, 323, 108168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikiishi, K.; Nakasato, H. Height dependence of the tendency for reduction in seasonal snow cover in the Himalaya and the Tiβn Plateau region, 1966–2001. Ann. Glaciol. 2006, 43, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.S. Global and regional snow cover decline: 2000–2022. Climate 2023, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Trends and variability in snowmelt in China under climate change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Tejeda, E.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Beniston, M. The changing roles of temperature and precipitation on snowpack variability in Switzerland as a function of altitude. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 2131–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Zhou, X.; Tuo, Y.; Li, R.; Duan, Z. The vertical influence of temperature and precipitation on snow cover variability in the Central Tianshan Mountains, Northwest China. Hydrol. Process. 2019, 33, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Robinson, D.A.; Kang, S. Changing Northern Hemisphere snow seasons. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5305–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorkauf, M.; Marty, C.; Kahmen, A.; Hiltbrunner, E. Past and future snowmelt trends in the Swiss Alps: The role of temperature and snowpack. Clim. Change 2021, 165, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Hao, L.; Fu, Q.; Liu, H.; Ren, Y.; Li, T. Analysis of spring drought in Northeast China from the perspective of atmosphere, snow cover, and soil. CATENA 2024, 236, 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, B.; Su, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, G. Prediction of spring agricultural drought using machine learning algorithms in the southern Songnen Plain. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3836–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Su, Y.; Fu, Q.; Ren, Y.; Li, T. Study on the driving factors of spring agricultural drought in Northeast China from the perspective of atmosphere and snow cover. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 317, 109620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Cui, M.; Wan, J.; Zhang, S. A review on snowmelt models: Progress and prospect. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wigmosta, M.S.; Yan, H.; Eldardiry, H.; Yang, Z.; Deb, M.; Wang, T.; Judi, D. Amplified extreme floods and shifting flood mechanisms in the Delaware River Basin in future climates. Earths Future 2024, 12, e2023EF003868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Yang, D.; Robinson, D. Winter rain on snow and its association with air temperature in northern Eurasia. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 2728–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kar, K.K.; Srivastava, S.; Koya, S.R.; Pokharel, S.; Likins, M.; Roy, T. Trends and causal structures of rain-on-snow flooding. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, F.; Chen, Y.; Fang, G.; Li, Z.; Duan, W.; Qin, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, B. Unraveling the complexities of rain-on-snow events in High Mountain Asia. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chen, X.; Hamdi, R.; Li, L.; Cui, F.; De Maeyer, P.; Duan, W. Rainfall-driven extreme snowmelt will increase in the Tianshan and Pamir regions under future climate projection. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, G.; Liu, D.W.; Zhao, X.C.; Zhang, Q. Snow droughts over 1951–2021 show a decreasing and then increasing trend. Atmos. Res. 2025, 325, 108237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.