Spatial–Temporal Response of Urban Flooding to Land Use Change: A Case Study of Wuhan’s Main Urban Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. NewFlood Model

2.2.2. Roughness Coefficient

2.2.3. Land-Use Change Matrix

2.3. Data Sources and Scenario Design

2.3.1. DEM and Land Use Data

2.3.2. Rainfall Model and Scenario Design

3. Results

3.1. Verification of the Simulation Results of Urban Flooding

3.2. Characteristics of Land Use Change

3.2.1. Spatial Characteristics of Land Use Change

3.2.2. Analysis of Land Use Transfer

3.3. The Influence of Land Use Changes on Water Depth in MUAW

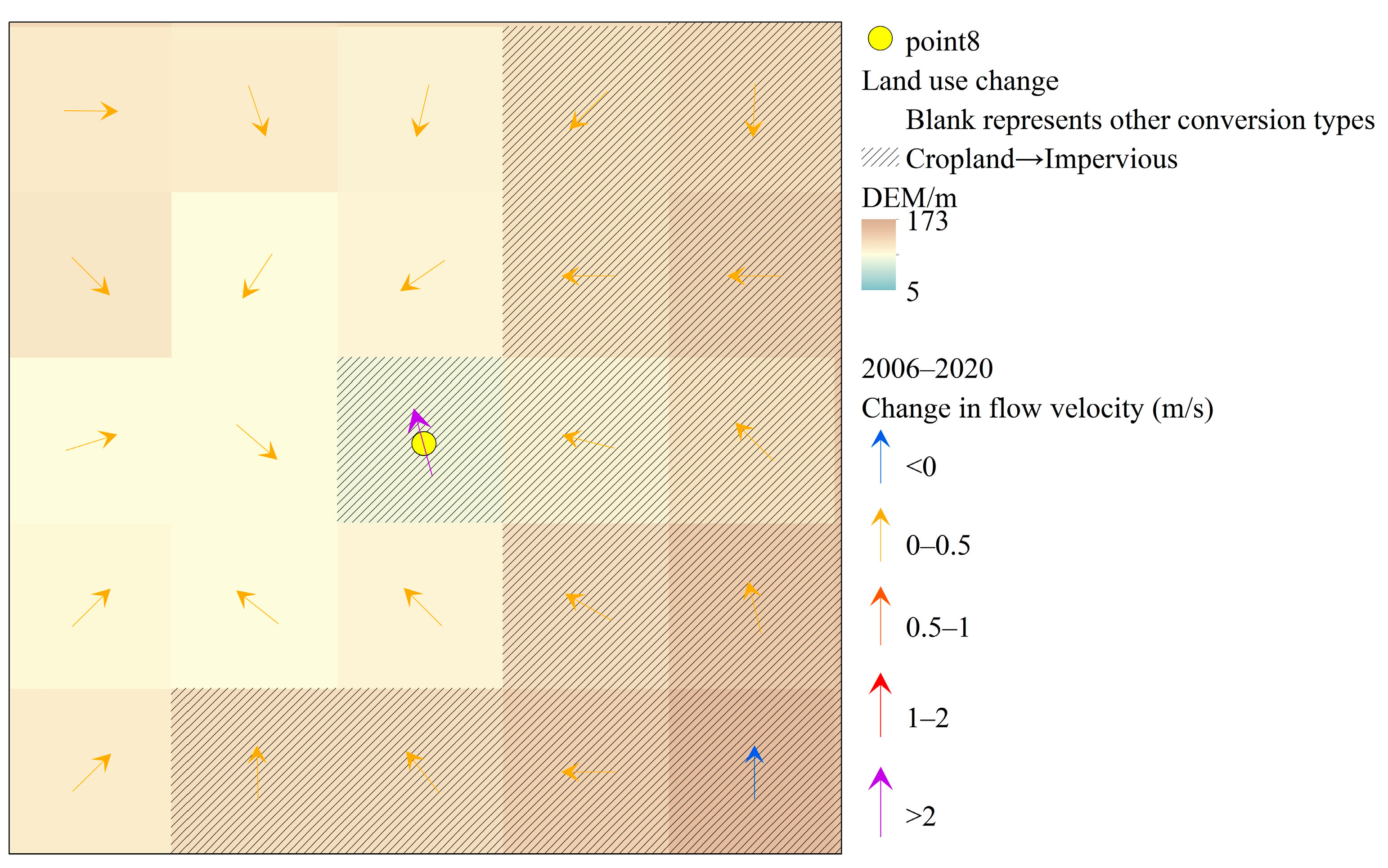

3.4. The Influence of Land Use Changes on the Flow Velocity in Flood-Prone Areas

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on the Significance of This Study

4.2. Discussion on Comparing with Existing Study Results

4.3. Practical Implications for Urban Flood Management

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MUAW | Main Urban Area of Wuhan |

References

- Rentschler, J.; Avner, P.; Marconcini, M.; Su, R.; Strano, E.; Vousdoukas, M.; Hallegatte, S. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 2023, 622, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaian, S.K.; Sanders, B.F.; Abdolhosseini Qomi, M.J. How urban form impacts flooding. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Gan, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Horton, D.E. Urbanization enhances channel and surface runoff: A quantitative analysis using both physical and empirical models over the Yangtze River basin. J. Hydrol. 2024, 635, 131194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslinger, K.; Breinl, K.; Pavlin, L.; Pistotnik, G.; Bertola, M.; Olefs, M.; Greilinger, M.; Schöner, W.; Blöschl, G. Increasing hourly heavy rainfall in Austria reflected in flood changes. Nature 2025, 639, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Geng, X.; Jia, W.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Wu, Z. Towards climate-adaptive equality in coastal megacities: Assessing urban flooding risk disparities and nonlinear effect of multidimensional indicators through an interpretable LightGBM-SHAP framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 132, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.J. Urban Waterlogging Simulation and LID Optimization Based on SWMM and FVCOM Coupling Model. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.J.; Wang, C.T.; Wang, W.J.; Zhang, L.L.; Huang, H.P.; Zhang, S.T. Regional runoff characteristics in Zhengzhou City based on SCS-CN model. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 42, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, G. Urban watershed ecosystem health assessment and ecological management zoning based on landscape pattern and SWMM simulation: A case study of Yangmei River Basin. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N. Urban Waterlogging Numerical Simulation and Multi-Scale Risk Assessment. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.H.; Lu, Q.H. Application of MIKE FLOOD model in drainage schemes for high-density built-up areas: Taking the southern region of Fuhai River in Shenzhen as an example. Pearl River 2024, 45, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.P.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, R.B. Application of XPSWMM hydraulic model in urban waterlogging control project of Pujiang County. Munic. Eng. Technol. 2025, 43, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelorosso, R.; Petroselli, A.; Cappelli, F.; Noto, S.; Tauro, F.; Apollonio, C.; Grimaldi, S. Blue-green roofs as nature-based solutions for urban areas: Hydrological performance and climatic index analyses. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 5973–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.J. Research on the Identification of Recreational Hotspots and Visual Landscape Optimization of Waterfront Greenways in Wuhan Based on Multisource Data. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, H.J.; Cheng, G. Evaluation of the planning and implementation of sponge city construction based on source control in Wuhan. China Water Wastewater 2023, 39, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Jiao, L.; Su, J. Urban land system change: Spatial heterogeneity and driving factors of land use intensity in Wuhan, China. Habitat Int. 2025, 159, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Z. Quantifying land-use change impacts on the dynamic evolution of flood vulnerability. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zevenbergen, C.; Ma, Y. Urban pluvial flooding and stormwater management: A contemporary review of China’s challenges and “sponge cities” strategy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 80, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Kesserwani, G.; Hall, J.W. A 2D shallow flow model for practical dam-break simulations. J. Hydraul. Res. 2011, 49, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; She, D.; Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the impact of low impact development practices on the urban flooding over a humid region of China. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022, 58, 1264–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Coulthard, T.J. Evaluating the importance of catchment hydrological parameters for urban surface water flood modelling using a simple hydro-inundation model. J. Hydrol. 2015, 524, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.Y. Urban Land Use Change and the Response of Flood Disasters—Based on the Empirical Research of Nanjing, Wuhan and Hefei. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Lin, B.; Falconer, R.A. A boundary-fitted numerical model for flood routing with shock-capturing capability. J. Hydrol. 2007, 332, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.Q.; Han, Y.Z.; Bai, X.M. Hydrological effects of littet on different forest stands and study about surface roughness coefficient. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2010, 24, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.P.; Guo, Y.X. Analysis on the spatio-temporal dynamic evolution of land use structure of western urban agglomerations in the past 40 years. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Bu, X.; Li, Y.F.; He, Z.F. Land use change and its impact on ecosystem service value in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020. J. Tianjin Norm. Univ. Sci. Ed. 2023, 43, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelorosso, R.; Apollonio, C.; Rocchini, D.; Petroselli, A. Effects of Land Use-Land Cover Thematic Resolution on Environmental Evaluations. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.-Y. Evaluation of the effect of land use/cover change on flood characteristics using an integrated approach coupling land and flood analysis. Hydrol. Res. 2016, 47, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, X.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, P. Urban flooding risk assessment based on the impact of land cover spatiotemporal characteristics with hydrodynamic simulation. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 4131–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, N. Review on flood hazard assessment index and grade classification. China Flood Drought Manag. 2019, 29, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.L.; Li, J.C.; Yang, D.; Bai, G.G.; Guo, K.H. Impact of land use change on catchment stormwater flooding process based on a hydrodynamic model. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2020, 31, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Bourke, R. Urbanization impacts on flood risks based on urban growth data and coupled flood models. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhou, X.; Mills, J.; Xiao, W. Impact of land use/land cover changes on urban flooding: A case study of the Greater Bay Area, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 13261–13275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Use Type | Roughness Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Impervious | 0.016 |

| Water | 0.027 |

| Grassland | 0.030 |

| Cropland | 0.035 |

| Forest | 0.150 |

| Barren | 0.025 |

| Scenario ID | Land Use Scenario | Rainfall Return Period (Years) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 2006 | 5 | Baseline land use under standard rainfall |

| S2 | 2006 | 50 | Baseline land use under heavy rainfall |

| S3 | 2006 | 100 | Baseline land use under extreme rainfall |

| S4 | 2020 | 5 | Urbanized land use under standard rainfall |

| S5 | 2020 | 50 | Urbanized land use under heavy rainfall |

| S6 | 2020 | 100 | Urbanized land use under extreme rainfall |

| Land Use Type | 2020 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropland | Forest | Grassland | Water | Barren | Impervious | Total | Change Rate | ||

| 2006 | Cropland | 278.301 | 3.230 | 0.009 | 9.059 | 0.005 | 124.250 | 414.852 | −27.343% |

| Forest | 3.270 | 14.356 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.115 | 17.757 | −0.935% | |

| Grassland | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.216 | 0.248 | −95.968% | |

| Water | 19.455 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 170.275 | 0.01 | 11.387 | 201.133 | −9.818% | |

| Barren | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.050 | −62.000% | |

| Impervious | 0.369 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.998 | 0.000 | 327.099 | 329.466 | 10.201% | |

| Total | 301.425 | 17.591 | 0.010 | 181.385 | 0.019 | 463.074 | 963.505 | - | |

| No. | Flood-Prone Location | Land Use Change (2006~2020) | Maximum Flow Velocity (m/s) | Time of Maximum Flow Velocity (min) | Maximum Water Depth (m) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2020 | Δv | 2006 | 2020 | Δv | 2006 | 2020 | Δv | |||

| 1 | Near Jianyi Road | No change | 12.121 | 12.125 | +0.004 | 75 | 75 | 0 | 4.495 | 4.496 | +0.001 |

| 2 | Near Yinhu Street | No change | 10.993 | 10.992 | 0.000 | 70 | 70 | 0 | 4.256 | 4.256 | 0.000 |

| 3 | Qingliuzi Interchange | No change | 0.374 | 0.374 | 0.000 | 71 | 71 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

| 4 | Youyi Avenue Overpass | Cropland converted to impervious | 3.468 | 5.799 | +2.331 | 68 | 68 | 0 | 4.344 | 4.344 | 0.000 |

| 5 | Near Baiyu Chemical Plant and Kangning Road | Cropland converted to impervious | 1.646 | 3.566 | +1.920 | 66 | 63 | −3 | 4.274 | 4.288 | +0.014 |

| 6 | Near Xuhong Avenue | No change | 5.663 | 5.664 | +0.001 | 70 | 70 | 0 | 4.019 | 4.020 | +0.001 |

| 7 | Raoyang Road and Bayi Road | Cropland converted to impervious | 5.585 | 11.930 | +6.345 | 77 | 77 | 0 | 4.570 | 4.570 | 0.000 |

| 8 | Guanggu Third Road and Erquan Street | Cropland converted to impervious | 5.124 | 11.095 | +5.971 | 64 | 62 | −2 | 4.358 | 4.371 | +0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Wang, Y. Spatial–Temporal Response of Urban Flooding to Land Use Change: A Case Study of Wuhan’s Main Urban Area. Hydrology 2026, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010003

Wang T, Wang Y. Spatial–Temporal Response of Urban Flooding to Land Use Change: A Case Study of Wuhan’s Main Urban Area. Hydrology. 2026; 13(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tianle, and Yueling Wang. 2026. "Spatial–Temporal Response of Urban Flooding to Land Use Change: A Case Study of Wuhan’s Main Urban Area" Hydrology 13, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010003

APA StyleWang, T., & Wang, Y. (2026). Spatial–Temporal Response of Urban Flooding to Land Use Change: A Case Study of Wuhan’s Main Urban Area. Hydrology, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010003