Abstract

The elimination of toxic and long-lasting dyes like crystal violet (CV) from wastewater continues to be a major environmental challenge. Considering this, in this study, a novel amine-modified adsorbent was synthesized by functionalizing ZIF-67 with phosphorylethanolamine (PEA@ZIF-67) nanocomposite to enhance dye removal efficiency. Comprehensive characterization of PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite using FTIR, XRD, TGA, and BET techniques confirmed the successful incorporation of PEA into ZIF-67 without compromising the structural integrity of the ZIF-67. The BET specific surface area of PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite was noted to be 145.3 m2/g. Furthermore, the application of PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite for CV adsorption was investigated and optimized using the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) technique, with the adsorbent dosage, initial dye concentration, and temperature as the operational variables. Under optimized conditions, qmax was 4348 mg/g. Adsorption kinetic studies showed the Avrami model to best fit the respective CV adsorption results, suggesting a heterogeneous and time-dependent mechanism. On the other hand, the Redlich–Peterson adsorption isotherm, which signifies a hybrid adsorption behavior, was noted to be effective. The thermodynamic studies confirmed that the CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67 is spontaneous, endothermic, and entropy-driven. The post-adsorption FTIR and XRD analyses indicated that the used PEA@ZIF-67 was stable, thus supporting its reuse capability.

Keywords:

ZIF-67; crystal violet; phosphorylethanolamine; adsorption; RSM; Avrami; Redlich–Peterson; functionalization 1. Introduction

Industrial wastewater discharged into the biosphere poses alarming risks to human health and ecosystems. This wastewater contains many toxic and hazardous substances, such as dyes, which impair the quality of receiving water bodies. The presence of dyes in water bodies can significantly impede light penetration, thereby diminishing photosynthetic activity, which is crucial for aquatic life [1]. Moreover, several dyes are known to pose severe threats to human health through various exposure routes, such as ingestion, dermal contact, or inhalation, and are carcinogenic and mutagenic [2,3,4]. Among these dyes, Crystal Violet (CV) stands out due to its extensive industrial use and high environmental persistence. Widely applied in the textile dyeing, printing inks, and biological staining, CV is a synthetic triphenylmethane dye that has raised growing concern because of its toxicity, resistance to biodegradation, and potential health hazards [5]. These characteristics make its removal from industrial effluents both challenging and critical. Therefore, it is urgently necessary to create efficient and cost-effective techniques to remove these dyes. Techniques to treat dyes encompass a broad spectrum of approaches, including physical, chemical, and biological treatments, each presenting a unique set of advantages and disadvantages. Physical methods, such as adsorption, membrane filtration, and coagulation, are widely employed due to their simplicity and effectiveness in removing dyes from water [6,7,8,9]. Among these, adsorption has gained prominence due to its cost-effectiveness and ability to remove a wide range of dyes [10,11]. Several types of adsorbents have been utilized for dye removal, including activated carbon [12], zeolites [13], alumina [14], and MOF/ZIF, known for their high thermal and chemical stability [15,16,17]. Several studies reported the removal of CV dye from wastewater via adsorption [5,18,19,20,21]. Among these, ZIF-based adsorbents have recently gained significant attention due to their remarkable thermal and chemical stability [22]. One recent example is ZIF-60, which was used for CV removal [23] and showed a high adsorption capacity. These findings reinforce the potential of ZIF materials, specifically the modified ZIFs, to serve as the next-generation adsorbents for the treatment of respective polluted streams. Phosphorylethanolamine (PEA) is an organic compound that serves as an important intermediate in the biosynthesis of phospholipids, which are a major component of biological membranes [24]. Structurally, it contains both a phosphate and an amine group. In materials science and nanotechnology, PEA is used as a surface modifier or functionalizing agent, where its amine and phosphate groups enable it to bond with metal ions or MOFs, enhancing hydrophilicity, stability, and interfacial compatibility of materials [25]. Building on this, the study investigates ZIF-67 functionalized with phosphorylethanolamine (PEA@ZIF-67) nanocomposite for removing CV dye from water, aiming to improve interaction and adsorption capacity through targeted functionalization. To the best of our knowledge, no study so far has explored the application of PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite for water decontamination and specifically for dye removal. Considering this, the present research successfully synthesized, characterized, and demonstrated the successful application of PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite for CV dye removal with a high adsorption capacity. The post-adsorption PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite characterization also confirmed it to be stable. The adsorption process was also optimized using the response surface methodology (RSM) based modeling.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

Reagent-grade high-purity chemicals, including Sigma-Aldrich 98% Co(NO3)2∙6H2O, 2-methylimidazole (C4H6N2, ≥99% purity, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), ammonium hydroxide (ACS standards met, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), phosphorylethanolamine (PEA, ≥96% purity, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), were used. Ultra-pure water was used for all the experimental work.

2.2. Nanocomposite Production

Initially, 68.39 g of Co(NO3)2∙6H2O was stirred in 470 mL of ultra-pure water for ten minutes at room temperature. Concurrently, 77.1 g of 2-methyl imidazole and 500 mL of ammonium solution (NH4OH)/PW mixture (250 mL Na4OH + 250 mL ultra-pure water) are mixed together to give the second solution, which was also stirred for 10 min. Afterward, these solutions were stirred for 1 h. The resulting solution was left standing for another hour and then centrifuged 4 times (20 min each) at 6000 rpm. The washed solution was placed in the oven to dry completely for three days at 80 °C. Finally, the ZIF-67 powder was kept in sealed vials before undergoing functionalization and characterization. For the incorporation of PEA into ZIF-67, 10 g of ZIF-67 was thermally activated under vacuum at 150 °C for 24 h. Following activation, the ZIF-67 powder was mixed in a 300 mL ultra-pure water solution and was sonicated for 30 min using an amplitude of 70% and an on-off frequency of 30-3 s. Concurrently, in a separate closed flask, 2.93 g of PEA was stirred with 200 mL of ultra-pure water. Both solutions were mixed together in a round-bottom flask and were kept under stirring for 10 min. Subsequently, this solution was subjected for 24 h to an oil bath reflux system at 100 °C. The resultant solution was then centrifuged three times (20 min each) at 6000 rpm. The liquid mixture was then exposed to 80 °C (three days), and PEA@ZIF-67 was preserved in a sealed vial prior to utilization and characterization. For the characterization part, the FTIR measurements (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10, Waltham, MA, USA) were measured up to 4000 cm−1 using a DTGS KBr detector and KBr beamsplitter, with a gain setting of 1.0 and an optical velocity of 0.4747. A Rigaku Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used for XRD tests, whereas the thermogravimetric analysis was completed using TA Instruments Discovery SDT 650 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Furthermore, the specific surface area and pore size were determined using a BELSORP MAX X specific surface area and porosity analyzer (BEL Japan, Inc., Osaka, Japan).

2.3. Crystal Violet Adsorption Experiments

2.3.1. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Modeling

The RSM technique was employed to optimize the system variables, including adsorbent dosage, CV concentration, and temperature, as specified in Table 1. Specifically, a face-centered central composite design (FCCCD) was utilized, with one replication each for factorial, axial, and center points. The design comprised randomized experimental runs to minimize bias and ensure statistical robustness; 15 lab experiments were conducted, and the corresponding adsorption capacities were recorded. The software used for RSM modeling is Design Expert Version 13

Table 1.

The RSM factors and levels.

For the adsorption work, 100 mL of the solution at the specified initial CV concentration was mixed with the predetermined dosage of PEA@ZIF-67. The mixtures were then agitated on a shaker at three different temperatures (10, 25, and 40 °C) for 24 h at 250 rpm. Afterward, 0.2 µm filters were used for separation, and the aqueous samples were tested for dye concentration using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Equations (1) and (2) were then employed for data analysis.

where qt (mg/g) is adsorption capacity, R (%) represents removal efficiency, Absblank is the absorbance value of blank and Abssample at t is the absorbance value of sample at time t, V (in liter) is the volume of treated solution, m (g) is the mass of adsorbent used (PEA@ZIF-67), and Co & Ct are CV amounts at time zero and time t (in mg/L).

2.3.2. Adsorption Tests

For the rate/kinetics of CV uptake by PEA@ZIF-67, time was varied under constant experimental conditions (PEA@ZIF-67 dosage = 5 mg, initial CV concentration = 150 mg/L, temperature = 40 °C, and neutral pH maintained using ultra-pure water in all solutions). The aim was to evaluate the rate at which CV was removed from the solution and to accurately determine the equilibrium adsorption time. The obtained kinetic data were analyzed by fitting to models, i.e., pseudo-first order (Equation (3)), pseudo-second order model [26] (Equation (4)), Avrami-model [27] (Equation (5)), and intra-particle (Equation (6)) to identify the best-fitting model describing the adsorption kinetics.

where qt (mg/g) is adsorption capacity, at time t, qe (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (qt at time t, qe at equilibrium), k1 (1/min), k2 (g/mg/min), kAV (1/min) and Kdiff (mg/g·min0.5) are respective rate constants, C (mg/g) is intraparticle model intercept, and t (min) is the adsorption time.

The isotherm experiments were completed at 5 to 400 mg/L of CV concentration. All experiments were performed under constant conditions (adsorbent dosage = 5 mg, temperature = 40 °C). Altogether 11 adsorption experiments were completed, and the respective data were then analyzed by fitting to the Langmuir [28] (Equation (7)), Freundlich [29] (Equation (8)), and Redlich–Peterson [30] (Equation (9)) to evaluate the adsorption behavior and identify the model providing the best fit.

where qmax (mg/g) is the maximum adsorption capacity, KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir adsorption constant, KF (mg/g·(L/mg)1/n) is the Freundlich adsorption capacity constant, n (dimensionless) is the Freundlich adsorption intensity (heterogeneity factor), KRP (L/g) is the Redlich–Peterson adsorption capacity constant, aRP () stands for Redlich–Peterson number related to adsorption affinity, bRP (dimensionless) exponent indicates the adsorption heterogeneity, and Ce (mg/L) is the adsorbate’s equilibrium amount.

The thermodynamic parameters of adsorption were determined to evaluate the nature and spontaneity of CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67. Three experiments were conducted at 10, 25, and 40 °C, with an adsorbent dosage = 5 mg and an initial CV concentration = 100 mg/L. The distribution coefficient Kd was calculated using the Kd = qe/Ce. The ΔH° and entropy ΔS° were determined utilizing the van’t Hoff equation (Equation (10)), while Gibbs free energy (ΔG°) was computed in accordance with Equation (11) [31].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of PEA@ZIF-67

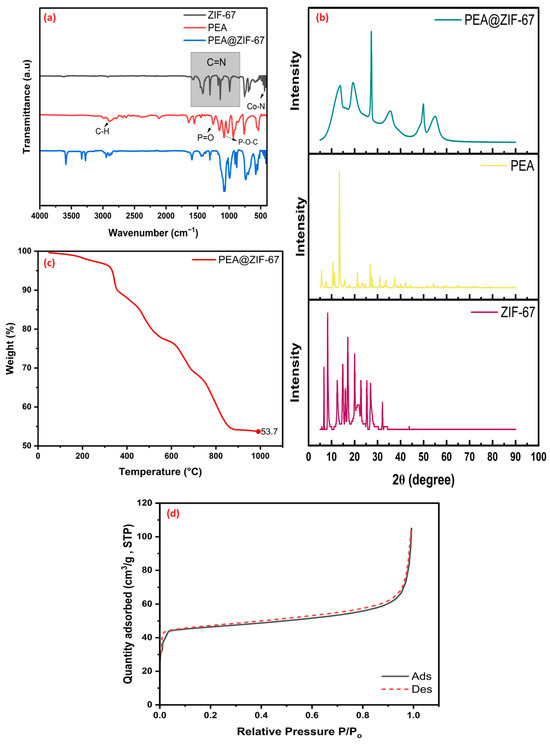

FTIR spectra of ZIF-67, PEA, and PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite are presented in Figure 1a. Most peaks in the PEA@ZIF-67 spectrum correspond to features from the original components, i.e., ZIF-67 and PEA. Notably, the Co–N stretching vibration observed at a range from 420 to 430 cm−1 in ZIF-67 undergoes a slight shift in PEA@ZIF-67, appearing at 418 cm−1, indicating possible interaction between cobalt centers and the functional groups of PEA. In the region from 540 to 1600 cm−1, vibrations associated with the imidazole ring (ZIF-67) and phosphate groups (PEA), such as P=O and P–O–C stretching, are evident, confirming successful modification of the ZIF-67 with PEA. Also, a distinct peak is seen close to 2948 cm−1 that matches with the C-H stretching from PEA [32,33,34,35,36,37]. Additionally, peaks at 3277, 3335, and 3591 cm−1 are new within the FTIR spectrum of PEA@ZIF-67, which are absent in both pristine ZIF-67 and PEA. These peaks likely correspond to N–H and O–H stretching vibrations influenced by hydrogen bonding or coordination effects introduced during the modification process, and their presence further supports the successful incorporation and interaction of PEA within the ZIF-67 framework. Furthermore, XRD findings in Figure 1b show that characteristic diffraction peaks of ZIF-67 are retained in PEA@ZIF-67, indicating the crystalline form of the parent framework is retained. Notable peaks in the PEA@ZIF-67 pattern appear at 2θ values of 13.78°, 19.2°, 27.26°, 35.62°, 49.9°, and 55.18°, which are consistent with the typical reflections of the crystal structure of ZIF-67. The preservation of these peaks confirms that the modification process with PEA did not disrupt the stability of ZIF-67. Furthermore, the absence of sharp PEA peaks in the composite suggests that PEA is either highly dispersed within the ZIF-67 matrix or has interacted with the framework. These results collectively indicate that PEA was successfully incorporated into ZIF-67. Additionally, the TGA curve of PEA@ZIF-67 is shown in Figure 1c displays a multi-stage thermal decomposition pattern. The first weight loss below 150 °C is due to the evaporation of physically attached aqueous media or residual solvent. A significant weight loss at 150 °C till 400 °C is related to the loss of incorporated PEA, whereas the further decomposition observed from 400 °C to approximately 950 °C is associated with the gradual breakdown of the ZIF-67 structure [38]. The synthesized nanocomposite was also analyzed for specific surface area and pore size, and as shown in Figure 1d. The isotherm profile corresponds predominantly to a Type I(b) isotherm, indicative of narrow mesopores and wider micropores, with a noticeable Type IV contribution at relatively high relative pressures, confirming the existence of mesoporosity. A Type H4 hysteresis loop was also observed, suggesting slit-shaped pores and the coexistence of micro–mesoporous structures [39]. Quantitative analysis revealed 145.3 m2/g, 0.1521 cm3/g, and 2.09 nm values for specific surface area, pore volume, and pore diameter, respectively. Compared to pristine ZIF-67, the surface area has decreased. This decrease can be attributed to the partial blockage of pores by the grafted PEA molecules, as well as possible structural alterations during the modification process. Such effects are common in post-synthetic functionalization, where the introduced functional groups occupy part of the internal pore volume, thereby reducing the overall BET surface area.

Figure 1.

Characterization results for the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. (a) FTIR spectra of ZIF-67, PEA, and PEA@ZIF-67. (b) XRD patterns ZIF-67, PEA, and PEA@ZIF-67. (c) TGA curve of PEA@ZIF-67. (d) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of PEA@ZIF-67.

3.2. Crystal Violet Adsorption

3.2.1. Benchmarking CV Adsorption on Pristine ZIF-67 and PEA@ZIF-67

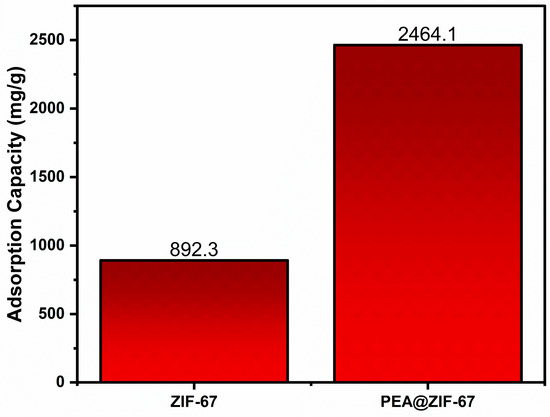

A 24 h adsorption test was conducted to compare the performance of the modified adsorbent (PEA@ZIF-67) with pristine ZIF-67. The adsorption capacities of CV on both materials are presented in Figure 2. As shown, PEA@ZIF-67 exhibited a substantially higher adsorption capacity, approximately a 2.75-fold improvement over the pristine ZIF-67 material. This clear enhancement demonstrates that functionalization significantly increased the adsorption capability of ZIF-67. Given this huge improvement, all subsequent studies (i.e., RSM modeling, kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamics) were conducted using PEA@ZIF-67.

Figure 2.

Comparison of CV adsorption capacity on ZIF-67 and PEA@ZIF-67.

3.2.2. RSM Modeling

Table 2 provides the results from the CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67, along with the respective RSM-based experimental design. The highest CV adsorption capacity was noted to be 590.81 mg/g at a 25 mg/L PEA@ZIF-67 dose, CV concentration of 150 mg/L, and 40 °C temperature, with a 98.5% removal efficiency. In contrast, the lowest adsorption of 47.87 mg/g was observed under the conditions of a 75 mg/L PEA@ZIF-67 dose, 50 mg/L CV concentration, and a temperature of 10 °C, with a corresponding removal efficiency of 71.8%. Notably, a lower adsorbent dose combined with higher dye concentration and elevated temperature significantly enhances the adsorption performance. This is postulated to result from the concentration gradient, which facilitates faster diffusion of dye molecules into the adsorbent [40]. Moreover, a lower adsorbent dosage also minimizes the possibility of particle aggregation, thereby maximizing the availability and utilization of active sites for adsorption. In contrast, higher dosages may promote particle agglomeration, reducing the above-mentioned effective surface characteristics [41].

Table 2.

The RSM-based design of experiments (DOE) and responses for CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67.

The RSM model describing the adsorption capacity as a function of the selected variables is also presented in Equation (12). The overall model significance was confirmed by the ANOVA results presented in Table 3, with a p-value less than 0.0001, showing that the developed reduced quadratic mathematical formulation adequately describes variability in the adsorption capacity. The variables A, B, C, A2, and B2, as well as their interactions, are also significant, with p-values less than 0.05. Hence, this model can be utilized to estimate the CV adsorption capacity onto PEA@ZIF-67 using the specified variables; A, B, and C represent the PEA@ZIF-67 dose (mg/L), initial CV concentration (mg/L), and temperature (°C), respectively.

ln Adsorption = 4.95 − 0.4562 A + 0.4923 B + 0.3081 C − 0.0787 AC + 0.0602 BC + 0.1301 A2 − 0.0861 B2

Table 3.

ANOVA results for the reduced quadratic model (transformed using natural log).

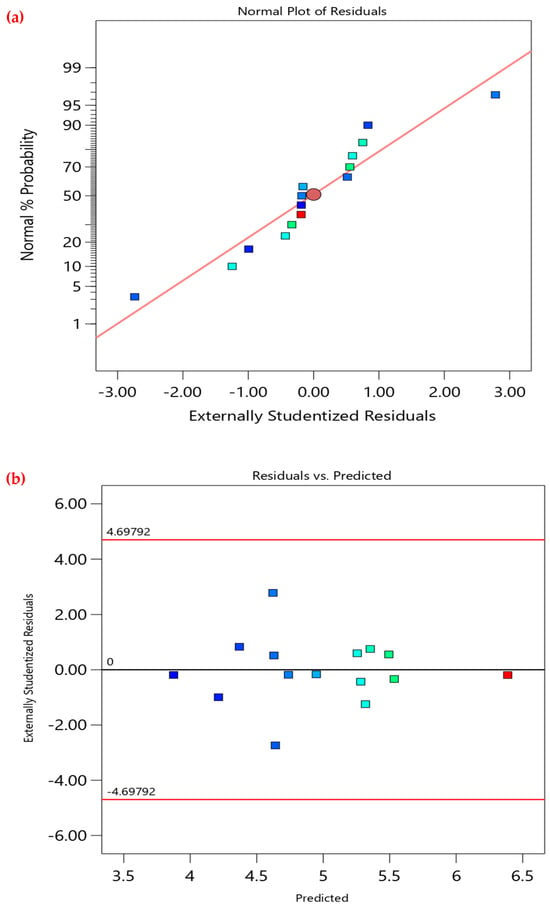

Additionally, validating the RSM model is crucial to confirm its reliability and accuracy. This can be achieved by model graphical analysis, as presented in Figure 3. The normality plot in Figure 3a shows a linear distribution of residuals, thus confirming the assumption of normality. Moreover, the residuals versus predicted plot (Figure 3b) confirms the randomness as the respective residuals are randomly scattered around the “0” line, and all residuals are within the limits. The predicted versus actual values plot (Figure 3c) also verifies the model’s predictive capability, since it shows tightly aligned data points along the 45° trend, demonstrating the RSM model’s high accuracy and reliability in predicting the adsorption capacity of CV onto PEA@ZIF-67. This is also proven by the fit statistics of the model shown in Table 4. The difference between adjusted R2 and predicted R2 must be less than 0.2 (20%) to confirm good agreement and validate the model’s predictive capability. In the present study, the change in R2 from adjusted (0.9939) to predicted (0.9885) was found to be 0.0054 (0.54%), which is well below the recommended threshold. Moreover, the adequate precision value of 69.5425 is more than the desirable minimum value of 4, indicating a very high signal-to-noise ratio. This further demonstrates that the model is statistically significant and possesses excellent predictive ability within the studied experimental range.

Figure 3.

Model graphical analysis. (a) normal plot of residuals, (b) residuals versus predicted plot, (c) predicted versus actual plot.

Table 4.

Fit statistics for the reduced quadratic model (transformed using natural log).

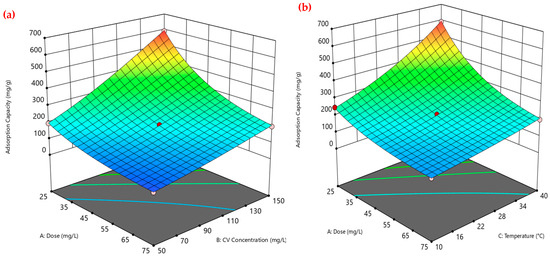

Furthermore, the three-dimensional surface plots shown in Figure 4 illustrate the interactive effects of PEA@ZIF-67 dose (A), CV dye concentration (B), and temperature (C) on the CV adsorption capacity of PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. As observed in Figure 4a (A vs. B at 40 °C), the adsorption capacity increases markedly with higher initial CV concentrations, especially at lower adsorbent dosages. This supports the earlier explanation regarding enhanced mass transfer due to a greater concentration gradient. Figure 4b (A vs. C at CV 150 mg/L), shows a similar trend, where higher temperatures contribute to increased adsorption capacity, particularly at lower doses. This may be attributed to the enhancement in kinetic energy of CV molecules at higher temperatures, which promotes better interaction with active sites on the adsorbent surface. This thermally driven mechanism will be further elaborated in the thermodynamic analysis section. Furthermore, Figure 4c (B vs. C at a constant dose of 25 mg/L) demonstrates that increasing both CV concentration and temperature leads to a synergistic improvement in the CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. The surface slopes upward toward higher values of both factors, reinforcing that the combined effect of elevated temperature and CV concentration significantly enhances the adsorption capacity of the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. Overall, the respective trends indicate that maximum adsorption capacity is achieved under the conditions of low adsorbent dose, high CV concentration, and elevated temperature, validating the significance of these factors in optimizing dye removal efficiency. Furthermore, the first interaction diagram (Figure 4d) clearly shows a decreasing trend in the adsorption capacity with an increasing adsorbent dose, particularly at higher temperatures (red line). The reason for this inverse relationship may be that PEA@ZIF-67 particles aggregate at higher dosages, decreasing the amount of specific surface area and active surface sites available for CV adsorption. The interaction also confirms that lower dosages are more effective at higher temperatures, supporting the earlier discussion and the findings presented in the response surface plots. Furthermore, in Figure 4e, a positive interaction is observed, where adsorption capacity increases significantly with both increasing dye concentration and temperature. At higher temperatures (red line), the increase in adsorption capacity is steeper, indicating a synergistic enhancement of dye uptake. This can be explained by the combined effect of a stronger concentration gradient (at high dye concentration) and increased molecular energy (at higher temperatures), which together promote a better penetration of CV molecules into the adsorbent pores and eventually lead to its stronger binding to the adsorption sites onto PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. These results further validate that high initial dye concentrations and elevated temperatures are key contributors to maximizing the CV adsorption efficiency.

Figure 4.

Response surface and interaction plots for the adsorption capacity of CV onto PEA@ZIF-67: (a) Dose vs. CV concentration; (b) Dose vs. Temperature; (c) CV concentration vs. Temperature; (d) interaction of dose and temperature; (e) interaction of CV concentration and temperature. Note: (1) red and light pink dots in (a–c) represent experimental values. (2) black, green, and red in (d,e) represent experimental values at low, center, and high levels.

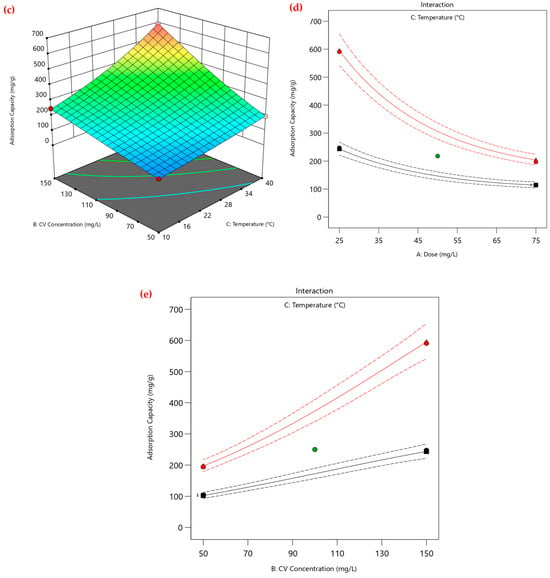

3.2.3. RSM Parameter Optimization

The numerical optimization results generated by Design-Expert (Version 13) software are presented in Figure 5. The ramp plots illustrate the optimum levels of the three factors, adsorbent dose, CV concentration, and temperature, required to achieve the maximum predicted adsorption capacity. The desirability function reached a value of 1.000, indicating that the selected conditions represent an optimal combination within the experimental design space. As shown, the optimal parameters were an adsorbent dose of 25 mg, CV concentration of 150 mg/L, and temperature of 40 °C, yielding a predicted adsorption capacity of 595.04 mg/g. These optimized conditions were subsequently adopted for the kinetic and isotherm experiments; however, a lower adsorbent dose (i.e., 5 mg) was used in those studies to minimize particle agglomeration and avoid overdosing effects that could mask the intrinsic adsorption behavior.

Figure 5.

Optimization ramp plots for CV adsorption. Note: red dots represent optimized inputs, and the blue dot represents the predicted response at optimal conditions.

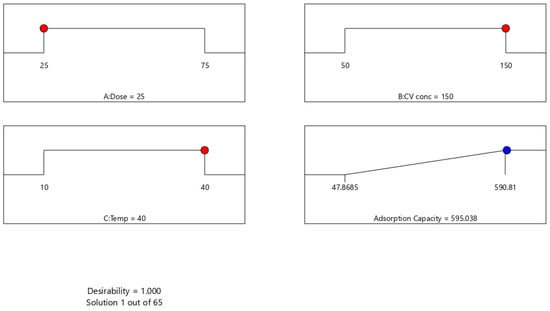

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics, Isotherms, and Thermodynamics

Understanding reaction kinetics is essential to realize the real-life applications [42]. In this study, time-dependent kinetics trends were thus probed to assess the removal behavior of CV dye using the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. The obtained results were then checked against pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), intra-particle, and Avrami models. In kinetic experiments, a lower adsorbent dose of 5 mg of PEA@ZIF-67 was used in 100 mL of 150 mg/L CV (at 40 °C). A total of 14 samples were analyzed at different contact times, ranging from 30 min to 96 h, to assess the equilibrium time. Several kinetic parameters, including adsorption capacity (qe), model-specific parameters, correlation coefficients (R2 and adjusted R2), and rate constants, are outlined in Table 5. Figure 6 also displays a plot of the experimental data and the fitted models. The respective results show that the Avrami kinetic model most accurately fits the experimental data, as demonstrated by its high adjusted R2 value of 0.996. This suggests that the adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67 occurs on a heterogeneous surface and involves multiple mechanisms, including both physisorption and chemisorption. Furthermore, the nature of the Avrami model implies a complex adsorption mechanism, suggesting that multilayer adsorption may occur during the early stages of the process, driven by surface heterogeneity and diffusion-controlled processes. It is also augmented by the increased adjusted R2 values obtained for the PFO (Adj-R2 = 0.994) and PSO (Adj-R2 = 0.985) formulations, indicating that both physical and chemical interactions may contribute to the overall CV removal. Additionally, the intra-particle diffusion model exhibited a reasonably good fit (Adj-R2 = 0.847), indicating that the pollutant’s movement into pores is important. This further confirms the complexity of the CV adsorption mechanism onto the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite, involving surface interactions, multilayer adsorption, and internal diffusion within the pores of the adsorbent.

Table 5.

Kinetic model equations, parameters, and fitting results for the adsorption of CV onto PEA@ZIF-67.

Figure 6.

Kinetic data and model fitting for the adsorption of CV onto PEA@ZIF-67.

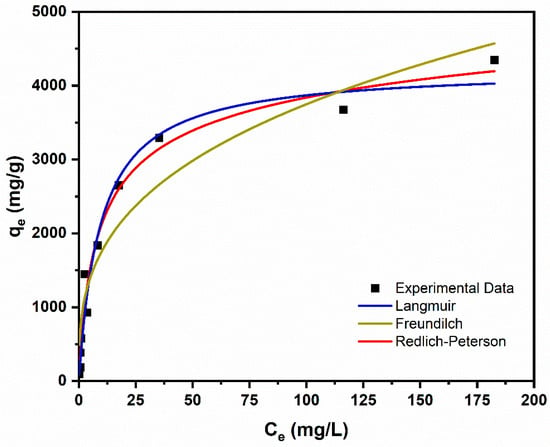

In continuation, the respective adsorption isotherm fitting outcomes are given in Table 6, while the corresponding plots are shown in Figure 7. An equilibrium contact time of 48 h, as determined from the kinetic studies, was employed in all isotherm experiments. The Redlich–Peterson isotherm displays a good model output among the tested models, evidenced by a high adjusted R2 of 0.975. This model suggests the presence of both monolayer and multilayer adsorption characteristics. Also, the exponent value bRP = 0.9 indicates a stronger affinity toward the Langmuir model, implying that monolayer adsorption is more dominant at equilibrium. Furthermore, a high CV adsorption capacity of 4348 mg/g, indicates strong interactions among CV dye and PEA@ZIF-67 functional groups (such as –PO4). In contrast, the kinetic data revealed a more complex adsorption mechanism. The Avrami kinetic model exhibited the best fit (Adj-R2 = 0.996), indicating a time-dependent process occurring on a heterogeneous surface and involving multiple mechanisms, including multilayer adsorption, physisorption, and chemisorption. The apparent discrepancy between the kinetic and equilibrium interpretations can be reconciled by considering the dynamic nature of the adsorption process. During the initial stages, adsorption may proceed through multilayer formation and diffusion-driven interactions, gradually stabilizing into a more uniform monolayer structure at equilibrium. Therefore, the combined analysis supports a sequential or co-existing adsorption behavior, where an initially complex, heterogeneous mechanism transitions into a predominantly monolayer-dominated state.

Table 6.

Isotherm equations, parameters, and fitting results for the adsorption of CV onto PEA@ZIF-67.

Figure 7.

Isotherms experimental data and plots.

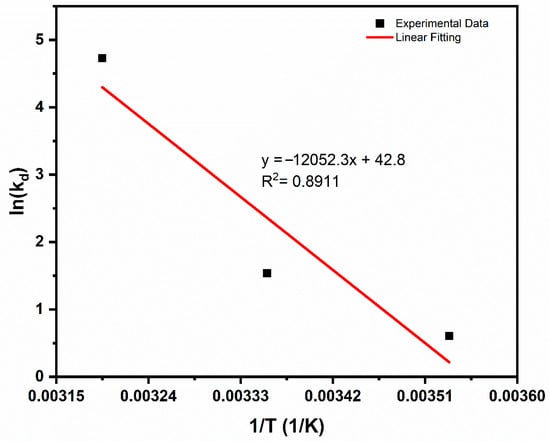

The thermodynamic nature of CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite was also evaluated and fitted to the van’t Hoff equation, with a linear plot of ln(Kd) versus 1/T shown in Figure 8. The corresponding thermodynamic parameters ΔG°, ΔH°, and ΔS° are also summarized in Table 7. Positive ΔH° = 100.20 kJ/mol supports an endothermic trend, thus showing that heat input enhances adsorption efficiency. This is further supported by the increasing Kd values and decreasing ΔG° with higher temperatures, which reflect an increased adsorption capacity and stronger adsorbent–adsorbate interactions as temperature rises. The positive entropy change suggests an increased disorder. This, along with the respective Gibbs free energy values (ΔG°), supports the spontaneous nature of the CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. Notably, as temperature rises, ΔG° becomes more negative, supporting an endothermic process where increased thermal energy promotes adsorption. Collectively, these thermodynamic results indicate that CV removal using PEA@ZIF-67 is preferred at elevated temperatures.

Figure 8.

Linear plot of ln(Kd) versus 1/T for thermodynamic analysis.

Table 7.

Thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of CV onto PEA@ZIF-67 at different temperatures.

The effect of functionalization on adsorption capacity is obvious. Compared with the pristine ZIF-67 and other adsorbent values reported in previous studies, shown in Table 8, the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite exhibited a significantly enhanced adsorption capacity, more than three times higher, and in some cases exceeding a fivefold improvement, relative to ZIF-67. This improvement can be attributed to the introduction of hydrophilic phosphate and amine functional groups from PEA, which facilitated stronger electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding with the cationic CV molecules. Overall, the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite exhibited an adsorption capacity that was the second highest among the compared materials, surpassed only by ZIF-60 in CV removal performance.

Table 8.

Adsorption capacities of various adsorbents for CV removal.

3.4. Post Adsorption Analysis

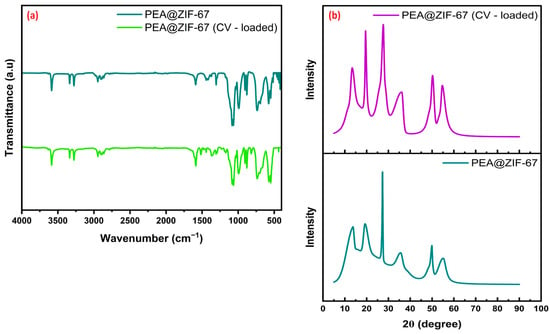

A further explanation of CV removal using PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite was also probed, and to achieve this, selective post-adsorption FTIR and XRD analyses were also performed and then compared with the respective pristine PEA@ZIF-67 findings (Figure 9). The FTIR results exhibit no significant shifts in the characteristic peak positions, indicating the absence of covalent bond formation between CV moieties and surface functional groups. However, a noticeable reduction in the transmittance intensity is observed, which can be attributed to PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite surface coverage by CV molecules. This phenomenon is commonly associated with physisorption, where the adsorbate molecules interact with the surface sites through non-covalent forces such as π–π stacking and weak van der Waals forces. Similarly, the XRD patterns confirmed the retention of the crystalline structure of PEA@ZIF-67 after CV adsorption, with no peak shifts or phase transformation, suggesting that the framework remained structurally intact. These findings also show that despite respective enhanced thermal activation, the crystallinity and integrity of the adsorbent framework are preserved, indicating higher stability of the PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite.

Figure 9.

(a) FTIR spectra and (b) XRD patterns of PEA@ZIF-67 before and after CV adsorption.

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism

Despite the physisorption-like behavior observed in post-adsorption FTIR and XRD analyses, thermodynamic and kinetic results suggest a more complex interaction. The high enthalpy change (ΔH° = 100.20 kJ/mol) obtained from thermodynamic studies strongly indicates a chemisorption process involving energetically significant interactions, such as electrostatic attraction or hydrogen bonding. Furthermore, the superior fit of the Avrami kinetic model (n = 1.14, Adj-R2 = 0.996) reflects a heterogeneous and time-dependent adsorption mechanism with contributions from both surface interaction and diffusion processes. The equilibrium data best fit the Redlich–Peterson isotherm, supporting a hybrid adsorption mode that combines features of both monolayer chemisorption and heterogeneous surface binding. Collectively, these findings indicate that CV adsorption onto PEA@ZIF-67 proceeds via a hybrid mechanism, where chemisorption dominates, supported by non-covalent physical interactions that do not disrupt the material’s structure. The overall process involves strong localized interactions facilitated by surface functional groups and enhanced by thermal activation, while preserving the crystallinity and integrity of the adsorbent framework.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully synthesized and functionalized ZIF-67 with PEA to develop a high-performance PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite for the treatment of CV-contaminated streams. A detailed PEA@ZIF-67 nanocomposite probe using FTIR, XRD, and TGA indicated attachment of PEA with the ZIF-67 framework, while BET specific surface area analysis demonstrated the material’s porous nature. Adsorption experiments revealed that PEA@ZIF-67 exhibited excellent dye removal of 4348 mg/g. RSM modeling identified adsorbent amount, initial dye concentration, and temperature as significant factors influencing adsorption capacity, with statistical validation confirming the model’s robustness and predictive reliability. The three-dimensional response surfaces highlighted that maximum adsorption occurs at low adsorbent doses, high dye concentrations, and elevated temperatures. Kinetic modeling revealed that the Avrami model best described the process (Adj-R2 = 0.996), indicating a heterogeneous, time-dependent mechanism involving both physisorption and chemisorption. Isotherm analysis favored the Redlich–Peterson model, suggesting hybrid adsorption behavior, while thermodynamic results confirmed endothermic and entropy-driven spontaneity. Post-adsorption characterization revealed framework stability, with physisorption-like behavior. Overall, PEA@ZIF-67 exhibits exceptional adsorption capacity and hybrid interaction mechanisms, positioning it as an effective adsorbent for CV dye removal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Methodology, S.A.O. and M.A.S.E.; Software, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Validation, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Formal analysis, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Investigation, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Resources, S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Data curation, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Writing—original draft, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Writing—review & editing, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Visualization, M.A.S.E., S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Supervision, S.A.O. and M.S.V.; Project administration, M.S.V.; Funding acquisition, M.S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Construction and Building Materials (IRC-CBM) at the King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals (KFUPM) under Research Grant # INCB2512.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the Chemical Engineering Department and the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at KFUPM for providing access to Lab facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, J.; Sharma, S.; Soni, V. Classification and impact of synthetic textile dyes on Aquatic Flora: A review. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 45, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Mohd-Setapar, S.H.; Chuong, C.S.; Khatoon, A.; Wani, W.A.; Kumar, R.; Rafatullah, M. Recent advances in new generation dye removal technologies: Novel search for approaches to reprocess wastewater. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 30801–30818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Recent advances for dyes removal using novel adsorbents: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y. A Ternary Magnetic Recyclable ZnO/Fe3O4/g-C3N4 Composite Photocatalyst for Efficient Photodegradation of Monoazo Dye. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, N.; Shefa, N.R.; Reza, K.; Shawon, S.M.A.Z.; Rahman, M.W. Adsorption of crystal violet dye from synthetic wastewater by ball-milled royal palm leaf sheath. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsami, S.; Mohamadi, M.; Sarrafzadeh, M.H.; Rene, E.R.; Firoozbahr, M. Recent advances in the treatment of dye-containing wastewater from textile industries: Overview and perspectives. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 143, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Ayub, F.; Baig, M.M.; Farooq, U.; Khan, S.A.; Al-Anzi, B. Sustainable clay-polymer adsorbents for emerging contaminants removal: A review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Khan, T.A.; Alharthi, S.S.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, H. Functionalized iminodiacetic acid pectin/montmorillonite hydrogel for enhanced adsorption of 4-nitrophenol from simulated water: An integrated approach of response surface optimization and non-linear modeling. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burakov, A.E.; Galunin, E.V.; Burakova, I.V.; Kucherova, A.E.; Agarwal, S.; Tkachev, A.G.; Gupta, V.K. Adsorption of heavy metals on conventional and nanostructured materials for wastewater treatment purposes: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 148, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, S.H.; Ng, C.H.; Islam, A.; Abdulkareem-Alsultan, G.; Joseph, C.G.; Janaun, J.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Khandaker, S.; Islam, G.J.; Znad, H.; et al. Sustainable toxic dyes removal with advanced materials for clean water production: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Maguana, Y.; Elhadiri, N.; Benchanaa, M.; Chikri, R. Activated Carbon for Dyes Removal: Modeling and Understanding the Adsorption Process. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2096834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, E.S.; Farghali, A.A.; Khedr, M.H.; Taha, M. Nano clinoptilolite zeolite as a sustainable adsorbent for dyes removal: Adsorption and computational mechanistic studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 409, 125538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Dubey, S.; Gautam, R.K.; Chattopadhyaya, M.C.; Sharma, Y.C. Adsorption characteristics of alumina nanoparticles for the removal of hazardous dye, Orange G from aqueous solutions. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 5339–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Ampiaw, R.E.; Lee, W. Adsorptive removal of dyes from wastewater using a metal-organic framework: A review. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Sabouni, R. Efficient removal of cationic dye using ZIF-8 based sodium alginate composite beads: Performance evaluation in batch and column systems. Chemosphere 2023, 342, 140163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.; Nataraj, N.; Panda, P.K.; Tseng, C.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Sakthivel, R.; Chung, R.-J. Construction of Methotrexate-Loaded Bi2S3 Coated with Fe/Mn-Bimetallic Doped ZIF-8 Nanocomposites for Cancer Treatment Through the Synergistic Effects of Photothermal/Chemodynamic/Chemotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 17, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabryanty, R.; Valencia, C.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Putro, J.N.; Santoso, S.P.; Kurniawan, A.; Ju, Y.-H.; Ismadji, S. Removal of crystal violet dye by adsorption using bentonite—Alginate composite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5677–5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, H.J.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Arumugam, T.K.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Vasudevan, D. An efficient removal of crystal violet dye from waste water by adsorption onto TLAC/Chitosan composite: A novel low cost adsorbent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, A.; Mittal, J.; Malviya, A.; Kaur, D.; Gupta, V.K. Adsorption of hazardous dye crystal violet from wastewater by waste materials. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2010, 343, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Pal, A. Removal of crystal violet dye from wastewater by surfactant-modified alumina. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2005, 44, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.A.; Ullah, S.; Shahid, M.U.; Hossain, I.; Najam, T.; Ismail, M.A.; Rehman, A.U.; Karim, R.; Shah, S.S.A. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIF-8 & ZIF-67): Synthesis and application for wastewater treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 356, 129828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, U.M.; Onaizi, S.A.; Vohra, M.S. Crystal violet removal using ZIF-60: Batch adsorption studies, mechanistic & machine learning modeling. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phosphorylethanolamine (Monoaminoethyl Phosphate)|Endogenous Metabolite|MedChemExpress. Available online: https://www.medchemexpress.com/Phosphorylethanolamine.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Song, X.; Zhao, T.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. A phosphorylethanolamine-functionalized super-hydrophilic 3D graphene-based foam filter for water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 343, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.I.; Onaizi, S.A.; Vohra, M.S. Novel CTAB functionalized graphene oxide for selenium removal: Adsorption results and ANN & RSM modeling. Emergent Mater. 2024, 7, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadi, S.A.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Onaizi, S.A. Adsorptive removal of organic pollutants from aqueous solutions using novel GO/bentonite/MgFeAl-LTH nanocomposite. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BinMakhashen, G.M.; Bahadi, S.A.; Al-Jamimi, H.A.; Onaizi, S.A. Ensemble meta machine learning for predicting the adsorption of anionic and cationic dyes from aqueous solutions using Polymer/graphene/clay/MgFeAl-LTH nanocomposite. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jamimi, H.A.; Bahadi, S.A.; BinMakhashen, G.M.; Onaizi, S.A. Optimal hybrid artificial intelligence models for predicting the adsorptive removal of dyes and phenols from aqueous solutions using an amine-functionalized graphene oxide/layered triple hydroxide nanocomposite. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkoshab, M.Q.; Al-Amrani, W.A.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Onaizi, S.A. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8/layered triple hydr(oxide) composite for boosting the adsorptive removal of acid red 1 dye from wastewater. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 699, 134637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, P.; de Paula, J. Physical Chemistry, 9th ed.; W. H Freeman Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, F.S.; Safdar, M.; Lewis, A.; Mazlan, N.A.; Radacsi, N.; Fan, X.; Arellano-García, H.; Huang, Y. Superhydrophobic ZIF-67 with exceptional hydrostability. Mater. Today Adv. 2023, 20, 100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, M.R.; Shaharun, M.S.; Khan, M.M.R.; Al-Mahmodi, A.F.; Almashwali, A.A.; Bangash, I. ZIF-67 hybridization and boron doping to enhance the photo-electrocatalytic properties of g-C3N4. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarayapalli, K.C.; Vattikuti, S.V.P.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Yoo, K.S.; Nagajyothi, P.C.; Shim, J. Hydrogen production and photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4/Co-MOF (ZIF-67) nanocomposite under visible light irradiation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, X.; Ai, L.; Jiang, J. Mechanistic insight into the interaction and adsorption of Cr(VI) with zeolitic imidazolate framework-67 microcrystals from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 274, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Lu, H.; Hong, X.; Jiang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Hollow Zn/Co ZIF Particles Derived from Core–Shell ZIF-67@ZIF-8 as Selective Catalyst for the Semi-Hydrogenation of Acetylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10889–10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalooei, M.; Torabideh, M.; Rajabizadeh, A.; Zeinali, S.; Abdipour, H.; Ahmad, A.; Parsaseresht, G. Evaluating the efficiency of zeolitic imidazolate framework-67(ZIF-67) in elimination of arsenate from aqueous media by response surface methodology. Results Chem. 2024, 11, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Cui, W.; Zou, Y.; Chu, H.; Xu, F.; Sun, L. Thermal decompositions and heat capacities study of a co-based zeolitic imidazolate framework. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W. Reporting Physisorption Data for Gas/Solid Systems with Special Reference to the Determination of Surface Area and Porosity. Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.K.; Salleh, M.A.M.; Karim, W.A.W.A.; Idris, A.; Abidin, Z.Z. Batch adsorption of basic dye using acid treated kenaf fibre char: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181–182, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djelloul, C.; Hasseine, A.; Hamdaoui, O. Adsorption of cationic dye from aqueous solution by milk thistle seeds: Isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Desalination Water Treat 2017, 78, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadi, S.A.; Al-Amrani, W.A.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Hossain, M.; Onaizi, S.A. Adsorption of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants from Wastewater Using Various Effective Adsorbents: A Comparative Study. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Z.; Liu, G. Efficient removal of crystal violet by polyacrylic acid functionalized ZIF-67 composite prepared by one-pot synthesis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 631, 127655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, R.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Adsorption of Crystal Violet Dye Using Activated Carbon of Lemon Wood and Activated Carbon/Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanocomposite from Aqueous Solutions: A Kinetic, Equilibrium and Thermodynamic Study. Molecules 2021, 26, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadi, S.A.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Onaizi, S.A. Adsorption of anionic and cationic azo dyes from wastewater using novel and effective multicomponent adsorbent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 337, 126402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Javeed, T.; Zafar, S.; Taj, M.B.; Ashraf, A.R.; Din, M.I. Adsorption of crystal violet dye by using a low-cost adsorbent—Peanut husk. Desalination Water Treat 2021, 233, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loulidi, I.; Boukhlifi, F.; Ouchabi, M.; Amar, A.; Jabri, M.; Kali, A.; Chraibi, S.; Hadey, C.; Aziz, F. Adsorption of Crystal Violet onto an Agricultural Waste Residue: Kinetics, Isotherm, Thermodynamics, and Mechanism of Adsorption. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 5873521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Lu, R.; Ren, S.S.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X. Three dimensional reduced graphene oxide/ZIF-67 aerogel: Effective removal cationic and anionic dyes from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 348, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, B.; Ioannou, K.; Kotanidis, G.; Ioannidis, I.; Constantinides, G.; Baker, M.; Hinder, S.; Mitterer, C.; Pashalidis, I.; Kostoglou, N.; et al. Removal of Crystal Violet Dye from Aqueous Solutions through Adsorption onto Activated Carbon Fabrics. C 2024, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Dwivedi, M.K.; Malviya, V.; Jain, P.; Yadav, A.; Jain, N. Adsorption of Crystal violet dye from aqueous solution by activated sewage treatment plant sludge. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 283, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, M.; Reguig, B.A.; Monir, M.E.A.; Althagafi, T.M.; Fatmi, M.; Remil, A.; Zehhaf, A.; Ghebouli, M.A. Kinetics thermodynamics and adsorption study of raw treated diatomite as a sustainable adsorbent for crystal violet dye. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.