Crude Blend Optimization for Enhanced Gasoline Yield: A Nigerian Refinery Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

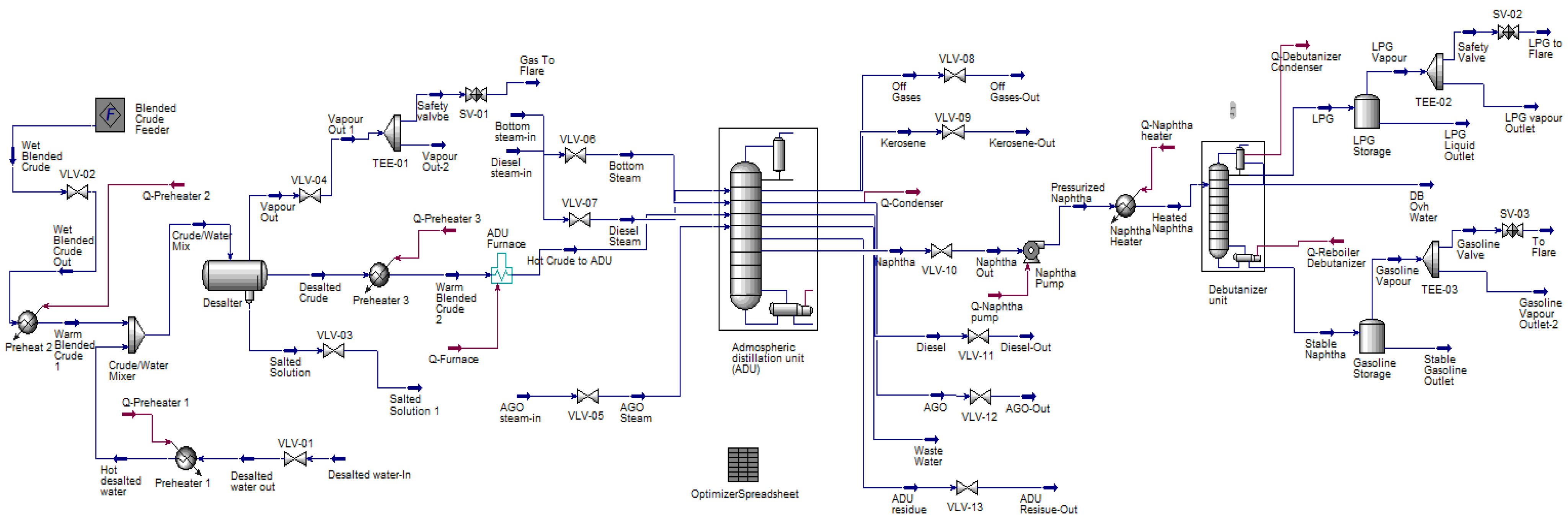

2.1. Simulation Tool and Process Methodologies

2.2. Generating Crude Oil Essay

2.3. Crude Oil Feeder and Desalting Process

2.4. Crude Distillation Column (CDU) Design

2.5. Debutanisation and Naphtha Stabilisation

2.6. Process Optimisation Using Aspen HYSYS

2.7. Variables, Functions, and Constraints

2.8. Sensitivity Analysis—Technical

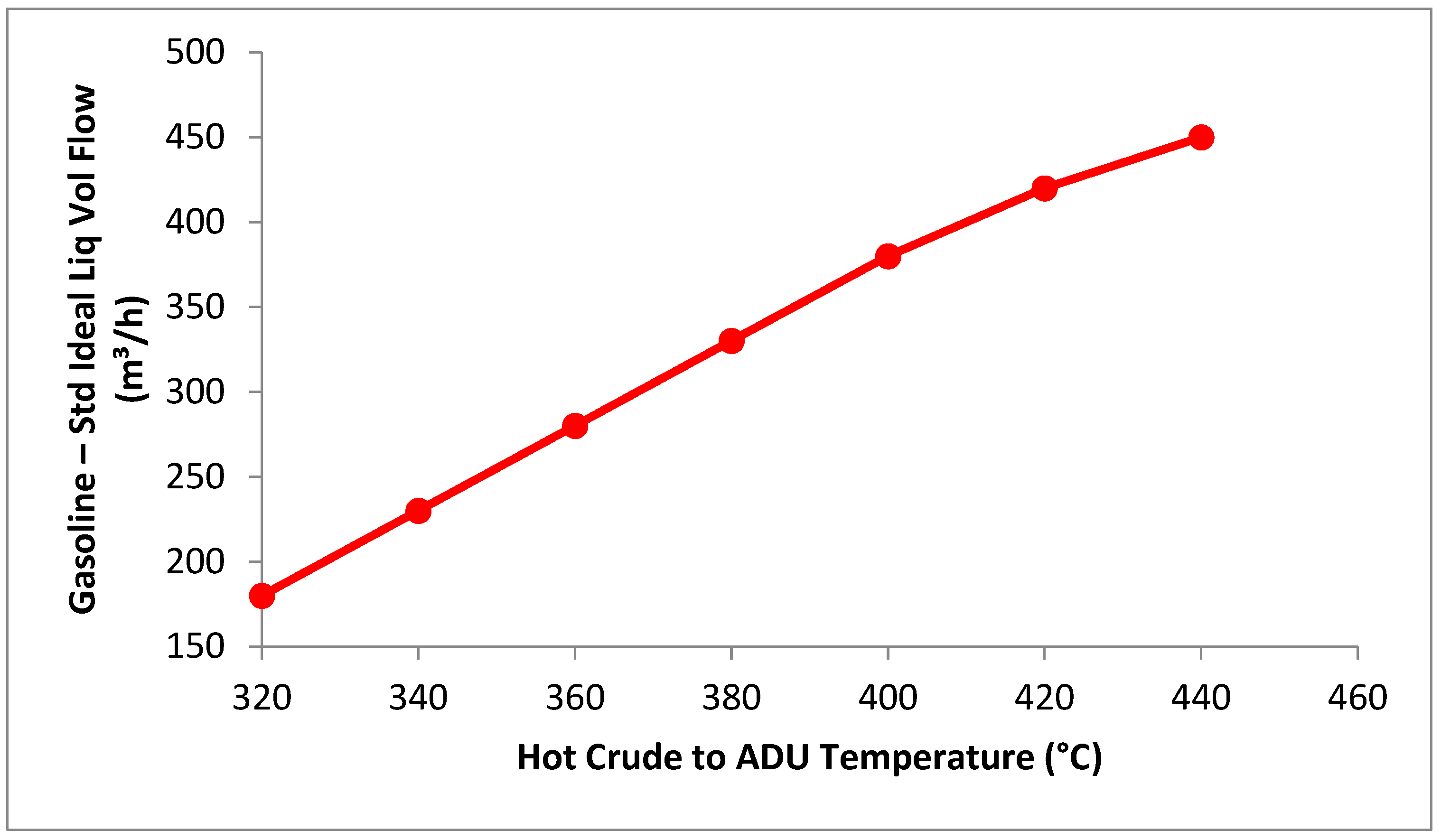

2.8.1. Case Study 1—Crude Oil Temperature vs. Gasoline Yield

2.8.2. Case Study 2—Crude Blend Ratio Constraints vs. Gasoline Yield

3. Process Economics Costing and Project Evaluation

3.1. Expenditure Costing Analysis

3.2. Revenue Costing Analysis

3.3. Profitability Analysis (PA)

3.4. Net Present Value (NPV)

- When NPV , the project is profitable.

- When NPV , the project breaks even.

- When NPV , the project is unprofitable.

3.5. Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- 4.

- When IRR , the project is profitable and should be accepted.

- 5.

- When IRR , the project breaks even and may be accepted if the other risks are favourable.

- 6.

- When IRR , the project is unprofitable and should be rejected.

3.6. Payback Period (PBP)

3.7. Sensitivity Analysis—Economics

3.7.1. Scenario 1—Crude Oil Price Increases

3.7.2. Scenario 2—Tax Increase

3.7.3. Scenario 3—Reduction in Operational Days by 10%

3.8. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Izuaka, M. NMDPRA Gives New Figure of Daily Petrol Consumption in Nigeria. 2022. Available online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/553297-nmdpra-gives-new-figure-of-daily-petrol-consumption-in-nigeria.html (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Okoro, E.E.; Dosunmu, A.; Igwilo, K.; Anawe, P.A.L.; Mamudu, A.O. Economic advantage of in-country utilization of Nigeria crude oil. Open J. Yangtze Oil Gas 2017, 2, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbuigwe, A. Refining in Nigeria: History, challenges and prospects. Appl. Petrochem. Res. 2018, 8, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.A.; Oni, A.O.; Adejuyigbe, S.B.; Adewumi, B.A. Thermo-economic and environmental assessment of a crude oil distillation unit of a Nigerian refinery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 66, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalinakshan, S.; Sivasubramanian, V.; Ravi, V.; Vasudevan, A.; Sankar, M.S.R.; Arunachalam, K. Progressive crude oil distillation: An energy-efficient alternative to conventional distillation process. Fuel 2019, 239, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, X.S.; Fan, Q.; Chen, J. Distillation yields and properties from blending crude oils: Maxila and Cabinda Crude Oils, Maxila and daqing crude oils. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, G.J. The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum, 5th ed.; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lόpez, C.D.C.; Hoyos, L.J.; Mahecha, C.A.; Arellano-Garcia, H.; Wozny, G. Optimization model of crude oil distillation units for optimal crude oil blending and operating conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 12993–13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaoping, L.; Luoyong, D.; Benxian, S.; Lijuan, Z.; Feng, T.; Xinru, X.; Jingyi, Y.; Beilei, Z. The distillation yield and properties of ternary crude oils blending. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2011, 29, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Bernal, D.E.; Franzoi, R.E.; Engineer, F.G.; Kwon, K.; Lee, S.; Grossmann, I.E. Integration of crude-oil scheduling and refinery planning by Lagrangean decomposition. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 138, 106812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Li, X.; Sui, H. The optimization and prediction of properties for crude oil blending. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2015, 76, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, X. A Novel Scheduling Strategy for Crude Oil Blending. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 18, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sad, C.M.; da Silva, M.; dos Santos, F.D.; Pereira, L.B.; Corona, R.R.; Silva, S.R.; Portela, N.A.; Castro, E.V.; Filgueiras, P.R.; Lacerda, V. Multivariate data analysis applied in the evaluation of crude oil blends. Fuel 2019, 239, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, E.A.; Sanchez-Reyna, G.; Ancheyta, J. Comparison of mixing rules based on binary interaction parameters for calculating viscosity of crude oil blends. Fuel 2019, 249, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Abdulla, T.; Hussein, A. Steady-state simulation and analysis of crude distillation unit at Baiji Refinery. J. Pet. Res. Stud. 2024, 14, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, M.; Bulama, I.; Mohammed, M. Optimizing crude distillation through heat integration: Insights from Kaduna Refinery, Nigeria. Int. J. Energy Power Syst. Res. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneh, O.C. A review on petroleum: Source, uses, processing, products and the environment. J. Appl. Sci. (Asian Netw. Sci. Inf.) 2011, 11, 2084–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattouh, B. The dynamics of crude oil price differentials. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyekunle, L.O.; Famakin, O.A. Studies on Nigerian crudes. I. characterization of crude oil mixtures. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2004, 22, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.O.; Tobi, A.J.; Aseibichin, C. Simulation of Nigerian crude oil types for modular refinery (topping plant) operations. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 12, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavella, R.A.; da Silva Júnior, F.M.R.; Santos, M.A.; Miraglia, S.G.E.K.; Pereira Filho, R.D. A review of air pollution from petroleum refining and petrochemical industrial complexes: Sources, key pollutants, health impacts, and challenges. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivito, F.; Ilham, Z.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I.; Oza, G.; Procopio, A.; Nardi, M. Oil spill recovery of petroleum-derived fuels using a bio-based flexible polyurethane foam. Polymers 2025, 17, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Shah, G.; Singh, H.; Bhatt, U.; Singhal, K.; Soni, V. Advancements in natural remediation management techniques for oil spills: Challenges, innovations, and future directions. Environ. Pollut. Manag. 2024, 1, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Firoozabadi, A.; Wheeler, M. Operational efficiency in the energy transition: Optimising existing oil and gas systems for sustainability. Comput. Energy Sci. 2024, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Saghir, H.; Ahmad, I.; Kano, M.; Çalişkan, H.; Hong, H. Prediction and optimisation of gasoline quality in petroleum refining: The use of a machine-learning model as a surrogate in an optimisation framework. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2024, 9, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijić, Ž.; Rimac, N. Data-driven fouling detection in refinery preheat-train heat exchangers using neural networks and gradient boosting. Sensors 2025, 25, 4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulhussein, Z.; Al-Sharify, Z.; Alzuraiji, M.; Onyeaka, H. Environmental significance of fouling on the crude-oil flow: A comprehensive review. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 27, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratiev, D.; Shishkova, I.; Angelova, N.; Atanassov, K. Generalised-net model of the processes in a petroleum refinery—Part I: Theoretical study. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazazi, A.; Farooq, Z. Heat integration retrofit for a sustainable energy-efficient design: A case study of Aramco’s refinery. Acad. Energy J. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, F.; Ayodele, E.; Wokoma, T. Leveraging process simulation for modular refinery optimisation: A case study on water-box cooler retrofit and crude distillation unit performance enhancement. In SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition; SPE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeek, M.; Elwardany, M.; Nassib, A.; Ahmed, M.; Mohamed, H.; Abdelaal, M. Sustainable refining: Integrating renewable energy and advanced technologies. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 17051–17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D86-23; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Petroleum Products and Liquid Fuels at Atmospheric Pressure. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D2892-22; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Crude Petroleum (15-Theoretical Plate Column). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Zhang, J.; Wen, Y.; Xu, Q. Simultaneous optimization of crude oil blending and purchase planning with delivery uncertainty consideration. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 8453–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, M.A.; Al-Sahhaf, T.A.; Elkilani, A.S. Fundamentals of Petroleum Refining: Products Composition; Elsevier: Oxford, UK; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ranaee, E.; Ghorbani, H.; Keshavarzian, S.; Ghazaeipour Abarghoei, P.; Riva, M.; Inzoli, F.; Guadagnini, A. Analysis of the performance of a crude-oil desalting system based on historical data. Fuel 2021, 291, 120046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokal, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A. Performance appraisals of gas/oil separation plants. SPE Prod. Oper. 2008, 23, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, B.; Cobbinah, I.J.; Ankomah, Y.; Marfo, S.A.; Dankwah, J.R. Desalting of crude oil using locally manufactured Ghanaian alcoholic beverage (akpeteshie) as demulsifier. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 2023, 16, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gary, J.H.; Handwerk, G.E.; Kaiser, M.J. Petroleum Refining: Technology and Economics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, D.; Gadalla, M.; Ashour, F. New retrofit approach for optimization and modification for a crude oil distillation system. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2013, 35, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaja, Z.; Akpa, J.G.; Dagde, K.K. Optimization of crude distillation unit case study of the port harcourt refining company. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, K.J.; Zein, S.H.; Hasan, A.H.; Ahmed, U.; Jalil, A.A. Process design optimisation, heat integration, and techno-economic analysis of oil refinery: A case study. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Effects 2023, 45, 4931–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.W.; Oh, M.; Lee, T.H. Design optimization of a crude oil distillation process. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2000, 23, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnot, R.K. Chemical Engineering Design: Chemical Engineering Volume 6 (Chemical Engineering Series), 4th ed.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Favennec, J. Economics of oil refining. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Energy Economics; Hafner, M., Luciani, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK; Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott, R.K.; Towler, G.P. Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Song, J. Operation optimisation of a combined heat and power plant integrated with flexibility retrofits in the electricity market. Energies 2025, 18, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Liu, S.; He, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Q.; Pan, M. Improving energy saving of crude oil distillation units with optimal operations. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GlobalPetrolPrices.com. United Kingdom Fuel Prices, Electricity Prices, Natural Gas Prices. 2023. Available online: https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/United-Kingdom/ (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. Typical Retail Prices of Petroleum Products and Crude Oil Price Index; Department for Energy Security and Net Zero: London, UK, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/oil-and-petroleum-products-monthly-statistics (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Aviation Fuel Prices. 2023. Available online: https://aviationfuelprices.com/aerodromes/category/airport/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

| Crude | API Gravity (°API) | Sulphur (wt%) | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antan | 26.5 | 0.27 | Medium-sweet |

| Usan | 29.0 | 0.27 | Medium-sweet |

| Bonga | 29.4 | 0.25 | Medium-sweet |

| Forcados | 31.05 | 0.22 | Medium-sweet |

| Product | Cut Point Range (°C) | Notes/Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) | <30 | C1–C4 light ends |

| Gasoline (naphtha) | 30–200 | [32,33]; motor spirit fraction |

| Kerosene | 150–250 | Jet fuel/domestic kerosene |

| Diesel | 250–360 | Automotive diesel oil |

| Atmospheric Gas Oil (AGO) | 360–540 | Feed to vacuum distillation/FCC |

| Residue | >540 | To vacuum distillation/residue upgrading |

| Parameter | Value/Description | Reference Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Total stages | 29 theoretical stages | HYSYS setup/refinery practice |

| Feed stage | Stage 28 | Typical CDU feed entry |

| Side strippers | 3 (kerosene, diesel, AGO) | [39] |

| Steam-to-product ratio | 0.05–0.1 kg/kg | [35] |

| Pump-arounds | 3 (upper ~tray 5, middle ~tray 12, lower ~tray 19) | Refinery practice |

| Product draw trays | Kerosene (tray 7), Diesel (tray 14), AGO (tray 21) | Literature ranges |

| Furnace outlet temperature | 340–370 °C | [40] |

| Condenser pressure | 140 kPa | HYSYS defaults/design data |

| Reboiler pressure | 230 kPa | HYSYS defaults/design data |

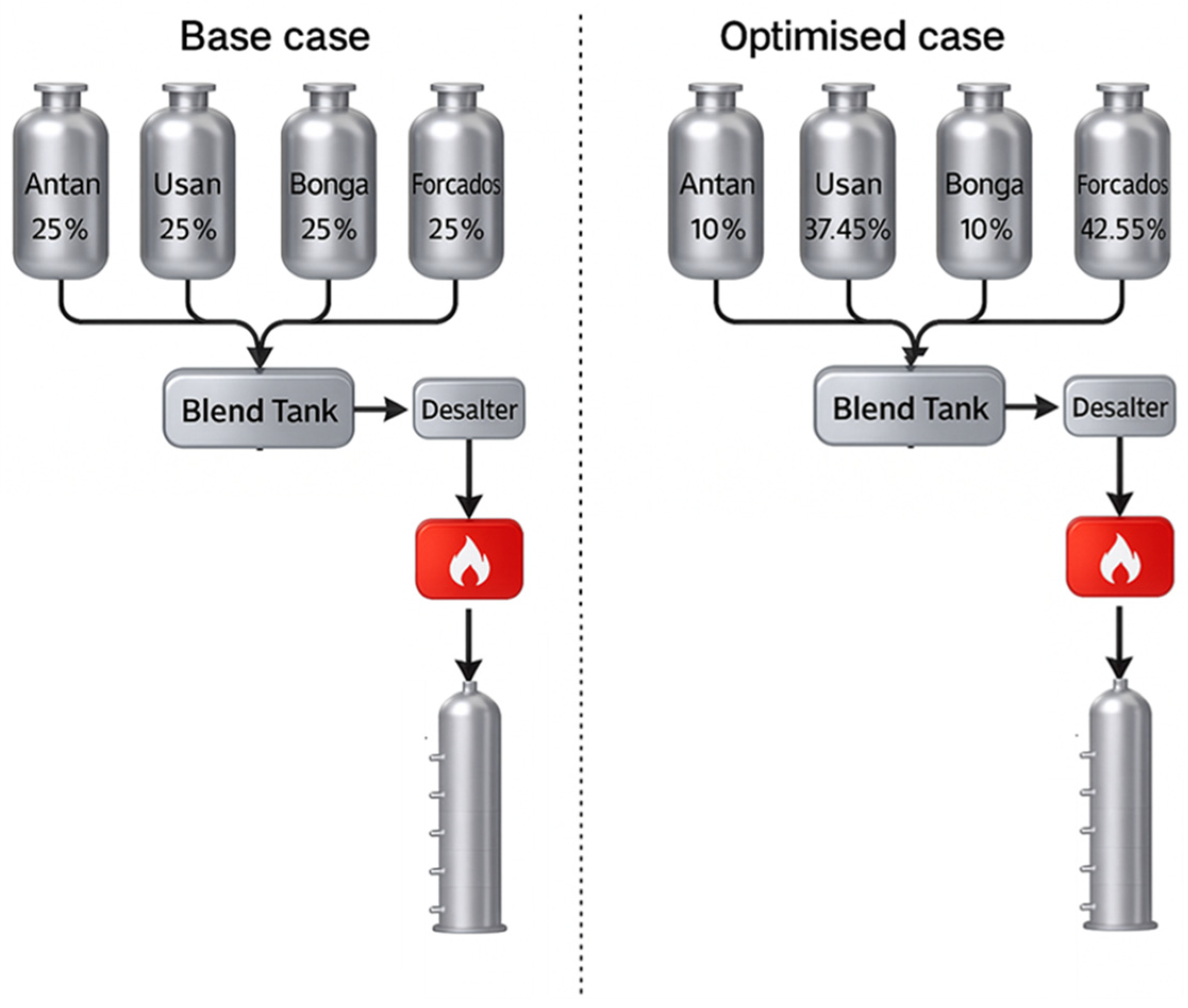

| S/N | Optimisation Iterations | Constraints (%) | Crude Oil Blending Ratio (%) | Total Ratio | Gasoline Yield (m3/h) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Higher Bound | Crude Ratio A | Crude Ratio B | Crude Ratio C | Crude Ratio D | ||||

| 1 | regular operations | 10 | 70 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | 315.6 |

| 2 | 1st | 10 | 70 | 11.22 | 47.47 | 16.73 | 24.58 | 100 | 326.77 |

| 3 | 2nd | 10 | 70 | 10 | 37.39 | 10 | 42.61 | 100 | 333.11 |

| 4 | 3rd | 10 | 70 | 10.01 | 37.40 | 10.01 | 42.58 | 100 | 333.10 |

| 5 | 4th | 10 | 70 | 10 | 37.45 | 10 | 42.55 | 100 | 333.10 |

| S/N | Petroleum Products | Mass Flowrate (kg/h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Work | Current Work | ||||||

| Regular Simulation | Optimized Simulation | DIFF (%) | Regular Simulation | Optimized Simulation | DIFF (%) | ||

| 1 | LPG | 7440 | 7474 | 0.46 | |||

| 2 | Gasoline | 75,120 | 76,560 | 1.92 | 245,400 | 258,400 | 5.30 |

| 3 | Kerosene | 51,830 | 52,390 | 1.08 | 55,220 | 55,360 | 0.25 |

| 4 | Diesel | 110,500 | 111,200 | 0.63 | 113,400 | 113,800 | 0.35 |

| 5 | Atmospheric gas oil | 29,690 | 29,770 | 0.27 | 27,530 | 27,640 | 0.40 |

| 6 | ADU residue | 315,700 | 315,700 | - | 420,100 | 403,700 | −3.90 |

| Parameter | Regular Blending | Optimized Blending | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gasoline yield (L day−1) | 7,572,000 | 7,999,200 | +5.64 |

| S/N | Optimization Iteration | Constraints (%) | Crude Oil Blending Ratio (%) | Total Ratio | Gasoline Yield (m3/h) | Gasoline Yield (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Higher Bound | Crude Ratio A | Crude Ratio B | Crude Ratio C | Cruderatio D | |||||

| 1 | Normal Operations | 10 | 70 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | 315.50 | - |

| 2 | Case 1 | 5 | 75 | 5.00 | 5 | 5 | 85 | 100 | 344.02 | 9 |

| 3 | Case 2 | 15 | 65 | 15.01 | 40.01 | 15.01 | 29.97 | 100 | 326.19 | 3.40 |

| 4 | Case 3 | 20 | 60 | 20 | 35.81 | 20 | 24.19 | 100 | 320.32 | 1.50 |

| 5 | Case 4 | 25 | 55 | 25 | 25.06 | 25 | 24.94 | 100 | 315.35 | −0.05 |

| S/N | Expenses | Amounts (GBP) | Remarks (GBP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Capital expenditure (CAPEX) | ||

| A1 | Fixed capital cost (FCC) | 5,357,165,985.92 | |

| A2 | Working capital cost (WCC) | 803,574,897.89 | |

| A3 | Indirect capital costs (ICC) | 924,111,132.57 | |

| Total direct capital costs (TDCC) | 6,160,740,883.80 | ||

| CAPEX summary | |||

| TDCC | 6,160,740,883.80 | ||

| TICC | 924,111,132.57 | ||

| Total CAPEX (investment) costs | 7,084,852,016.37 | ||

| B | Operating expenditure (OPEX) | ||

| B1 | Fixed operating cost (FOC) | 1,319,452,404.32 | |

| B2 | Variable operating cost (VOC) | 4,124,418,227.82 | |

| B3 | Indirect production cost (IPC) | 1,633,161,189.64 | |

| Total direct production cost (TDPC) | 5,443,870,632.13 | ||

| TDPC | 5,443,870,632.13 | ||

| TIPC | 1,633,161,189.64 | ||

| Total OPEX cost | 7,077,031,821.78 | Annual | |

| Annual production cost | Total OPEX Cost | 7,077,031,821.78 | |

| Production cost GBP/BSPD | Annual production cost/Annual production rate | 131.06 |

| S/N | Products | Product Yield | Rate (GBP) | Revenue (GBP/Day) | Revenue (GBP/Annum) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Qty (m3/h) | Vol. % | Qty (L/h) | Qty (L/d) | ||||

| 1 | LPG | 13.25 | 1.30 | 13,250 | 318,000 | 0.78 | 246,450 | 88,722,000 |

| 2 | Gasoline | 315.50 | 31.70 | 315,500 | 7,572,000 | 1.57 | 11,888,040 | 4,279,694,400 |

| 3 | Kerosene | 64.10 | 6.40 | 64,100 | 1,538,400 | 1.56 | 2,399,904 | 863,965,440 |

| 4 | Diesel | 128.90 | 13 | 128,900 | 3,093,600 | 1.45 | 4,485,720 | 1,614,859,200 |

| 5 | Gas Oil | 30.69 | 3.10 | 30,690 | 736,560 | 0.87 | 640,807.20 | 230,690,592 |

| 6 | Residue | 441.40 | 44.40 | 441,400 | 10,593,600 | 0.84 | 8,898,624 | 3,203,504,640 |

| 993.84 | 100.00 | 993,840 | 23,852,160 | 28,559,545.20 | 10,281,436,272 | |||

| S/N | Products | Products Yields | Rate (GBP) | Revenue (GBP/Day) | Revenue (GBP/Annum) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Qty (m3/h) | Vol (%) | Qty (L/h) | Qty (L/d) | ||||

| 1 | LPG | 13.25 | 1.30 | 13,250 | 318,000 | 0.78 | 246,450 | 88,722,000 |

| 2 | Gasoline | 333.30 | 33.50 | 333,300 | 7,999,200 | 1.57 | 12,558,744 | 4,521,147,840 |

| 3 | Kerosene | 64.10 | 6.40 | 64,100 | 1,538,400 | 1.56 | 2,399,904 | 863,965,440 |

| 4 | Diesel | 128.90 | 13 | 128,900 | 3,093,600 | 1.45 | 4,485,720 | 1,614,859,200 |

| 5 | Atmospheric Gas Oil | 30.69 | 3.10 | 30,690 | 736,560 | 0.87 | 640,807.20 | 230,690,592 |

| 6 | ADU Residue | 423.70 | 42.60 | 423,700 | 10,168,800 | 0.84 | 8,541,792 | 3,075,045,120 |

| 993.94 | 100 | 993,940 | 23,854,560 | 28,873,417.20 | 10,394,430,192 | |||

| S/N | Products | Product Yields for Regular Operation | Product Yields for Optimized Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Qty (m3/h) | Vol. (%) | Qty (L/h) | Qty (L/d) | Qty (m3/h) | Vol. (%) | Qty (L/h) | Qty (L/d) | |

| 1 | LPG | 13.25 | 1.30 | 13,250 | 318,000 | 13.25 | 1.30 | 13,250 | 318,000 |

| 2 | Gasoline | 315.50 | 31.70 | 315,500 | 7,572,000 | 333.30 | 33.50 | 333,300 | 7,999,200 |

| 3 | Kerosene | 64.10 | 6.40 | 64,100 | 1,538,400 | 64.10 | 6.40 | 64,100 | 1,538,400 |

| 4 | Diesel | 128.90 | 13.0 | 128,900 | 3,093,600 | 128.90 | 13.00 | 128,900 | 3,093,600 |

| 5 | Gas Oil | 30.69 | 3.10 | 30,690 | 736,560 | 30.69 | 3.10 | 30,690 | 736,560 |

| 6 | ADU residue | 441.40 | 44.40 | 441,400 | 10,593,600 | 423.70 | 42.60 | 423,700 | 10,168,800 |

| 993.84 | 100 | 993,840 | 23,852,160 | 993.94 | 100 | 993,940 | 23,854,560 | ||

| S/N | Gasoline Yields | Total Products Yield | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (L/h) | (L/yr) | (Rev/yr) | (L/h) | (L/yr) | (Rev/yr) | ||

| 1 | Regular crude blending | 315,500 | 2,725,920,000 | GBP 4,279,694,400 | 993,840 | 8,586,777,600 | GBP 10,281,436,272 |

| 2 | Optimized crude blending | 333,300 | 2,879,712,000 | GBP 4,521,147,840 | 993,940 | 8,587,641,600 | GBP 10,394,430,192 |

| 3 | Yield gain | 17,800 | 153,792,000 | GBP 241,453,440 | 100 | 864,000 | GBP 112,993,920 |

| 4 | Yield Gain (%) | 5.64 | 5.64 | 5.64 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.10 |

| S/N | Project Appraisal Indicators | Regular Values | Optimized Values | DIFF (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NPV | GBP 10,186,138,961.11 | GBP 10,795,149,778.30 | 6 | Increased and more preferable. |

| 2 | IRR | 33.70 | 34.70 | 2.80 | |

| 3 | PBP | 3.30 | 3.20 | −3.40 | Reduced and more preferable. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zein, S.H.; Ajayi, A.; Jabbar, K.J.; Abdullah, M.F.; Ahmed, U.; Jalil, A.A. Crude Blend Optimization for Enhanced Gasoline Yield: A Nigerian Refinery Case Study. ChemEngineering 2026, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010005

Zein SH, Ajayi A, Jabbar KJ, Abdullah MF, Ahmed U, Jalil AA. Crude Blend Optimization for Enhanced Gasoline Yield: A Nigerian Refinery Case Study. ChemEngineering. 2026; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleZein, Sharif H., Azeez Ajayi, Khalaf J. Jabbar, Muhammad Faiq Abdullah, Usama Ahmed, and A. A. Jalil. 2026. "Crude Blend Optimization for Enhanced Gasoline Yield: A Nigerian Refinery Case Study" ChemEngineering 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010005

APA StyleZein, S. H., Ajayi, A., Jabbar, K. J., Abdullah, M. F., Ahmed, U., & Jalil, A. A. (2026). Crude Blend Optimization for Enhanced Gasoline Yield: A Nigerian Refinery Case Study. ChemEngineering, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010005