Abstract

Food fermentation is an ancient bioprocess characterized by complex biochemical transformations driven primarily by microbial communities. Across the diverse regions of China, various ethnic groups have developed a rich array of traditional fermented foods through long-term practical experience. These foods are integral to local culinary heritage and provide valuable systems for studying microbial ecology and function. From the perspective of microbial interactions, this review summarizes key concepts and major interaction types—including mutualism, commensalism, and competition—and describes how bacteria, yeasts, and molds interact via metabolic division of labor to drive substrate conversion, flavor formation, preservation, and biosynthesis of functional compounds. Focusing on four representative ethnic fermented foods—Dong fermented fish, Mongoslian milk curd, Miao sour soup, and Manchurian kombucha—we analyze how microbial interactions contribute to product quality, safety, and sensory attributes. Given current challenges in industrializing traditional fermented foods, such as poor standardization and variable quality, we propose future research directions centered on modern microbiome tools, designed microbial consortia, and process optimization. This work aims to provide a scientific foundation and practical strategies for modernization and quality improvement of traditional fermented foods.

1. Introduction

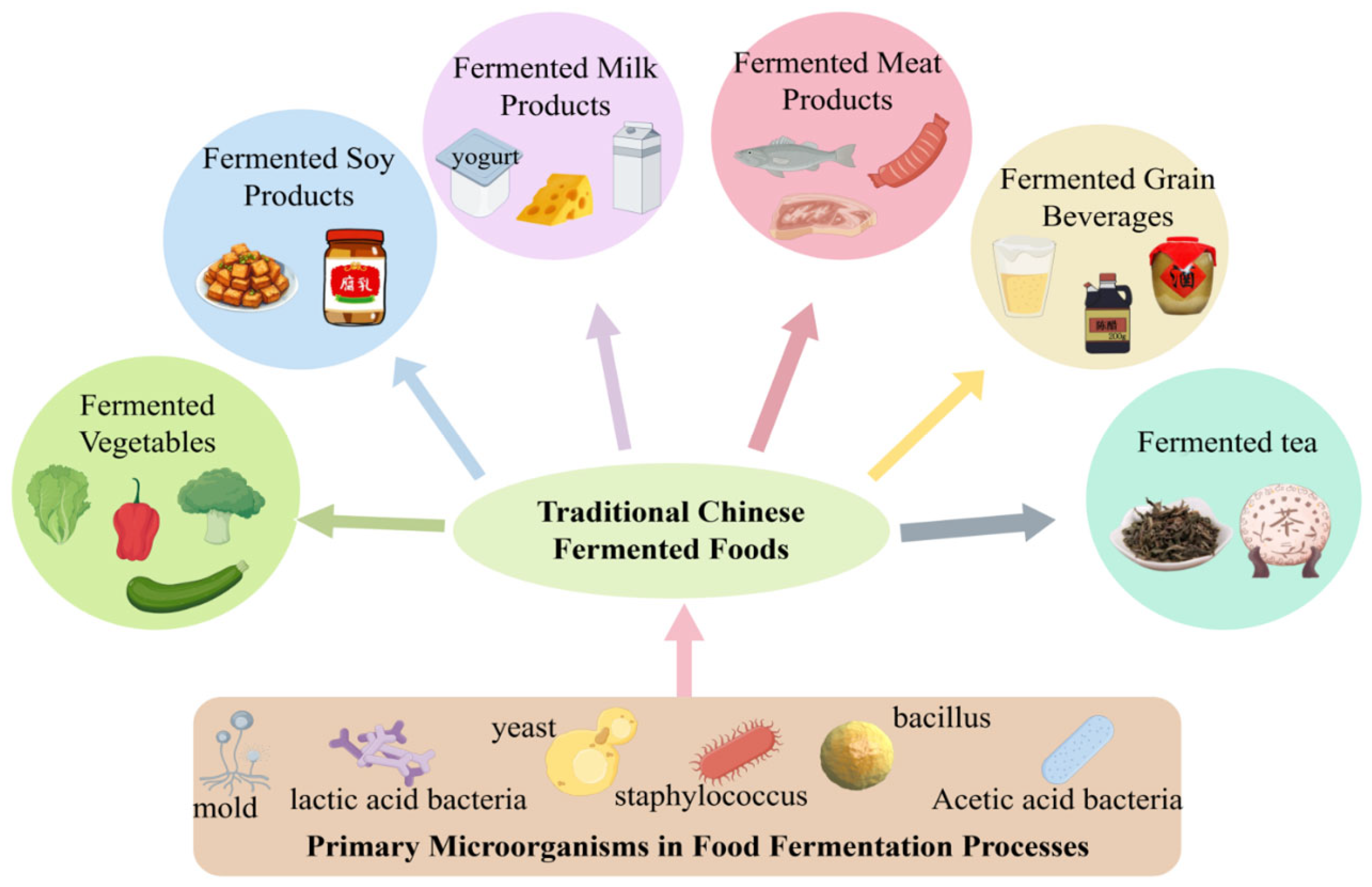

As a multi-ethnic nation, China has developed a rich and diverse culinary culture through the long-term historical practices of its fifty-six ethnic groups. Among these traditions, fermented foods—whether produced by natural fermentation or through inoculation with traditional starters—occupy an essential role in the daily diets and ceremonial practices of various communities. Their significance stems from sensory qualities [1], nutritional value [2,3], and reported health benefits [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Figure 1 presents an overview of traditional Chinese fermented foods, spanning categories such as fermented vegetables, soy products, dairy, meat, grains, and tea. Representative examples include sour meat [10] and sour fish [11] from southwestern regions, cheeses [12] and yogurts [13] associated with northern pastoral groups, and sour soups [14] and fermented soybean products [15] prevalent across various localities. These foods are not merely products of adaptive ingenuity in response to local environmental conditions; they also constitute a form of “living heritage,” deeply embedded with ethnic identity and cultural memory. Selected traditional fermented foods emblematic of China’s culinary heritage are further summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Traditional Chinese Fermented Foods.

Food fermentation involves the dynamic succession of microbial communities that convert substrates into biomass and diverse metabolites [16,17]. Within these systems, microorganisms engage in ecological interactions—such as mutualism, commensalism, and competition—which collectively enhance food safety, nutritional quality, and flavor development [18,19]. Key mechanisms include the production of antimicrobial compounds, nutrient competition and cross-feeding, ion acquisition, signaling, pH modulation, and biofilm formation [20]. In this context, “microbial interactions” refer to relationships that lead to measurable functional outcomes—such as flavor formation or safety enhancement—through mechanisms like cross-feeding or environmental modification. Correlations derived solely from omics-based analyses are insufficient to establish causality.

While pure-culture fermentation is well-established industrially, many traditional ethnic fermented foods derive their distinctive sensory and functional qualities from complex, naturally formed microbial consortia. The flavor complexity and functional diversity achieved through such interactive fermentation are difficult to replicate using single strains. Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms behind microbial interactions in traditional foods not only provides a scientific reappraisal of ethnic food heritage but also lays a theoretical foundation for developing novel starter cultures [21], optimizing fermentation processes [22,23], and advancing the standardization and industrialization of traditional production [24,25,26]. Such research is vital for preserving biological and cultural diversity and supporting sustainable local economies.

This review summarizes fundamental principles of microbial interactions and then examines their roles in representative fermented foods from China’s ethnic minorities. By synthesizing evidence on how complex microbial communities transform raw materials via ecological and metabolic networks, we further discuss how modern scientific approaches can be used to characterize, preserve, and improve these traditional bioprocesses.

Table 1.

Fermented Foods with Chinese Characteristics.

Table 1.

Fermented Foods with Chinese Characteristics.

| Types of Fermented Foods with Chinese Characteristics | The Microbial Strains Used in the Fermentation Process | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermented soybean products | Soy sauce | Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus sojae, Aspergillus niger | [27] |

| Fermented bean curd | Enterococcus, Lactococcus, Geotrichum, Mortierella, Bacillus cereus | [28] | |

| Soybean Paste | Aspergillus oryzae, Biscudii yeast, Bacillus, and Lactobacillus plantarum | [29,30] | |

| Fermented grain products | Vinegar | Lactobacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Lentilactobacillus, Limosilactobacillus, Leuconostoc, and Pediococcus. | [31] |

| Baijiu | Lactobacillus, Thermoactinomyces, Aquabacterium, Aspergillus, and Kazachstania | [32] | |

| Rice wine | Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Saccharomyces cerevisiae | [33] | |

| Fermented Vegetable Products | Pickled cabbage | Latilactobacillus sakei, Loigolactobacillus coryniformis subsp. torquens, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum, and Secundilactobacillus malefermentans | [34] |

| Kimchi | Lactococcus, Weismannia, and Lactobacillus | [35] | |

| Fermented meat products | Pickled Fish | Lactobacillus plantarum, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Bacillus, Micrococcus, Pseudomonas, Candida, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Saccharomyces | [36] |

| Ham | P. urinaeequi, P. pentosaceus, and L. pentosus.; S. xylosus, S. equus, S. gallinarum | [37] | |

| Fermented dairy products | Cheese | Lactococcus, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, and Enterococcus | [38] |

| Yogurt | Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Streptococcus, Leuconostoc, Bifidobacterium, and Peptostreptococcus | [39] | |

2. Microbial Interactions

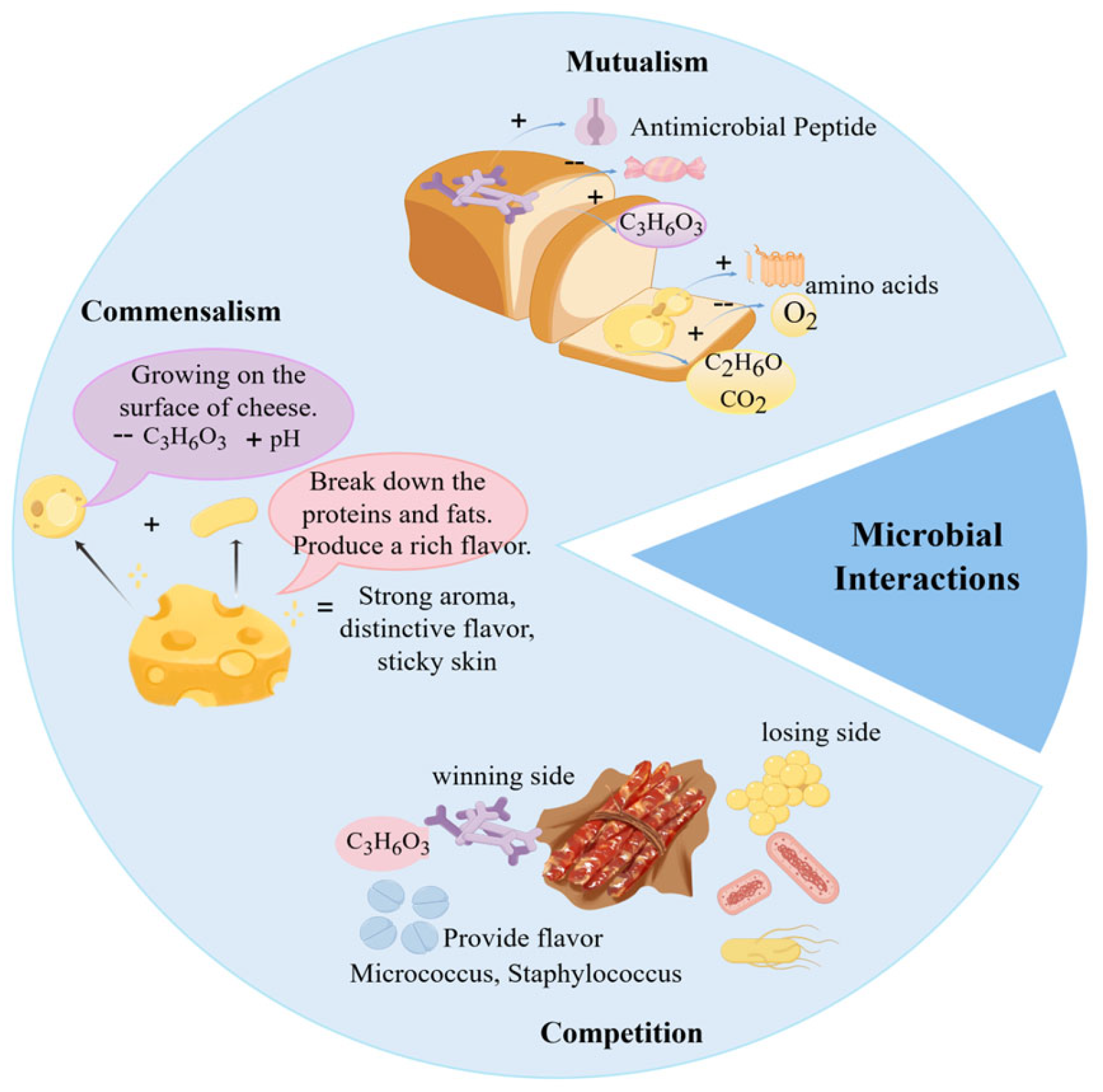

Microbial interactions play a pivotal role in food fermentation, not only determining fermentation success but also serving as the fundamental mechanism underlying the distinct sensory properties and safety of fermented products. Through cooperative and competitive relationships, acid-producing bacteria, oxygen-consuming microorganisms, and producers of antimicrobial substances collectively modify the fermentation milieu, selectively favoring the proliferation of beneficial microbes and thereby substantially improving product biosafety [40]. In contrast to the often monotonous flavor profiles resulting from single-strain fermentation, synergistic microbial activities give rise to complex, well-balanced, and multi-layered flavor systems [3,41,42]. Moreover, these interactions directly influence the physical structure of food, functioning both as a natural preservation strategy and as a key contributor to the enhancement of overall product quality and value [43,44,45]. As shown in Figure 2, common microbial interactions in food fermentation include mutualism, commensalism, and competition.

Figure 2.

Common Microbial Interactions in Food Fermentation.

2.1. Mutualism

Mutualism describes a close and interdependent interaction between two or more microorganisms, in which all participating members derive benefit from the relationship. It is characterized by coexistence and reciprocal dependence. In nature, over 98% of microorganisms exhibit some form of nutritional auxotrophy, lacking key genes or pathways necessary for the synthesis of essential metabolites [46]. These microorganisms rely on acquiring such nutrients from their environment to maintain vital cellular functions, making mutualistic relationships a widespread phenomenon in microbial ecosystems [47]. In food fermentation, whether through direct inoculation of specific microbes or by selectively promoting the growth of indigenous microbial populations, mutualistic interactions contribute to the production of organic acids, ethanol, and other metabolic end-products. These metabolites, in turn, enhance food safety, extend shelf life, and improve the sensory and functional qualities of fermented foods [48]. However, the extent of mutualistic benefits is often context-dependent, varying with strain specificity, substrate composition, and processing conditions.

Multiple studies indicate that interactions among diverse microbial communities can generate unique sensory characteristics. For example, in coffee fermentation, yeasts (such as Pichia kudriavzevii, Torulaspora delbrueckii, Hanseniaspora uvarum, Candida railenensis, Wickerhamomyces anomalus, etc.) and bacteria (e.g., Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum) are commonly involved [49,50,51]. The application of defined microbial starters has proven effective in modulating flavor quality. Sequential inoculation with Lactobacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for instance, enhances fruity and fermented notes while increasing the diversity of volatile compounds in coffee [52]. Similarly, coffee co-inoculated with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens achieves higher sensory evaluation scores [53]. In Swiss cheese fermentation, Ilhan [54] observed that Lactococcus lactis supplies lactic acid as a substrate and establishes a favorable environment for Propionibacterium, while Propionibacterium in turn creates structural pores that facilitate the growth of Lactococcus lactis and contributes to characteristic flavor development. Furthermore, Tong et al. [55] demonstrated that varying the inoculation ratio of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus significantly influences the fermentation kinetics and final properties of yogurt. These strains exhibit cross-feeding through the exchange of growth factors such as amino acids and formic acid, working collectively to accelerate acidification and aroma formation.

2.2. Commensalism

In fermentation systems, commensalistic interactions among microorganisms contribute to the development of complex flavor profiles in fermented foods. Commensalism describes a relationship in which one microorganism benefits from another without harming or benefiting the latter [56]. In practice, commensalistic effects may be difficult to distinguish from succession or indirect interactions without targeted validation. Such interactions can shape novel flavors by supporting the growth or activity of certain fermentative microbes, without negatively affecting the dominant fermenting populations. For instance, a Japanese research team reported that the characteristic flavor of white mold cheese arises from aromatic compounds generated through intricate bacterial–fungal interactions. Lactic acid bacteria lower the internal pH of the cheese, creating a favorable environment for the surface growth of the white mold Penicillium, which in turn forms the distinctive rind. The study further confirmed that volatile metabolites produced during this process significantly contribute to the unique aroma of the cheese [57]. Similarly, in soy sauce fermentation, Liu et al. [27] highlighted the roles of the koji fermentation and mash fermentation stages. During koji fermentation, molds such as Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus flavus enzymatically hydrolyze proteins and starches into short-chain compounds. These breakdown products then serve as substrates for lactic acid bacteria and yeasts during mash fermentation, where they are further converted into organic acids and aroma compounds that define the flavor of soy sauce. Additionally, Canon et al. [58] observed that proteolytic lactic acid bacteria can supply branched-chain amino acids to non-proteolytic strains, thereby promoting the growth of the latter without compromising their own metabolic activity. This finding offers a theoretical basis for designing fermented foods with improved functional properties or for developing novel fermentation substrates.

2.3. Competition

Competitive interactions occur when two or more microorganisms inhibit each other’s growth by competing for limited resources [59]. While some microbes may temporarily suppress others through the secretion of inhibitory metabolites, such effects are often transient. Over time, resistant subpopulations can emerge among the inhibited strains, subsequently competing with the dominant microbes for nutrients and ecological niches, thereby challenging their supremacy [60].

A representative example can be observed during kimchi fermentation. Initial colonizers such as Enterococcus faecalis rapidly utilize simple sugars (e.g., glucose and fructose) to produce acid and carbon dioxide, creating an acidic environment that inhibits competitors like Escherichia coli. As the pH drops and readily available sugars become depleted, the competitive fitness of E. faecalis declines. More acid-tolerant species, such as Lactobacillus plantarum, which can metabolize a broader range of carbohydrates, then gain a competitive advantage and become dominant in the mid-fermentation stage, driving further acidification. In the late stage, extremely low pH and nutrient scarcity suppress nearly all bacterial activity. At this point, acid-tolerant yeasts capable of utilizing residual complex carbon sources gradually become more competitive and initiate slow growth. This dynamic illustrates how shifts in environmental conditions continuously reshape the competitive landscape, leading to the succession of dominant microbial communities throughout fermentation [61,62,63].

Competitive mechanisms critically shape winemaking. Saccharomyces cerevisiae rapidly converts sugars into ethanol—a compound broadly inhibitory to many microorganisms. Its early metabolic activity also lowers pH, further suppressing competitors. Some strains even secrete proteinaceous toxins targeting wild yeasts. By thriving anaerobically and consuming oxygen, S. cerevisiae additionally restricts aerobic competitors like acetic acid bacteria and molds, securing dominance [64,65,66].

As highlighted in a review by Torres [67], ethanol stands out as the most significant inhibitory compound in alcoholic fermentations, with Saccharomyces cerevisiae being the primary producer of ethanol at high concentrations. Ashaolu et al. [68]. noted that lactic acid bacteria–dominated fermentations not only improve nutritional and sensory attributes but also enhance food safety through the production of antimicrobial compounds such as carbon dioxide, short-chain organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, diacetyl, and lactoperoxidase systems. These metabolites can help reduce aflatoxin levels, detoxify harmful substances, suppress pathogenic contamination, and lower the energy required for cooking, thereby improving the overall safety profile of grain-based fermented foods. The influence of microbial competition and other ecological interactions on the properties of representative fermented foods is summarized in Table 2. Notably, inhibitory outcomes are often modulated by environmental factors (e.g., pH, oxygen availability, and nutrient limitation) and may vary across strains and processing regimes.

2.4. Shared Mechanisms Underlying Microbial Interactions in Food Fermentations

Fermentation outcomes are shaped by microbial interactions across diverse systems. Early community assembly is initiated by environmental remodeling: pioneer microorganisms acidify the matrix or consume oxygen, thereby enriching functional taxa and suppressing competitors. For example, oxygen depletion by Aspergillus can favor vitamin B12 production by propionic acid bacteria [69]; oxygen availability drives bacterial succession and flavor development in Huangjiu wheat Qu [70]; and acidification by acid-tolerant bacteria inhibits pathogens [71]. Community stability and metabolic efficiency are sustained by metabolic complementarity and cross-feeding. Typically, yeasts or molds supply vitamins and amino acids to auxotrophic lactic acid bacteria (LAB), whereas LAB produce organic acids that lower pH and favor acid-tolerant populations [72], while promoting efficient macromolecule conversion.

Representative interaction modules include: (1) LAB–yeast consortia in sourdough and fermented beverages, where yeasts provide growth factors and LAB release assimilable nitrogen via proteolysis [73,74,75]; (2) yeast–acetic acid bacteria (AAB) consortia in kombucha and vinegar, in which yeast-derived ethanol is oxidized by AAB to acetic acid, generating an acidic environment that limits spoilage organisms [76,77]; and (3) mold–bacteria partnerships in soy sauce and cheese, where fungal extracellular enzymes (e.g., from Aspergillus spp.) liberate oligosaccharides and peptides that support bacterial growth and flavor biosynthesis [78,79]. These interactions also determine sensory properties: downstream conversion of ethanol and organic acids into volatile compounds (e.g., esters) drives aroma and flavor complexity [80], whereas nutrient competition and antimicrobial metabolites (e.g., bacteriocins) further modulate community structure and succession [81,82]. Collectively, fermentation is governed by coupled processes of environmental selection, metabolic cooperation, and competition that underpin ecosystem robustness and determine final product quality and safety.

Table 2.

Effects of Microbial Interactions on Fermented Foods.

Table 2.

Effects of Microbial Interactions on Fermented Foods.

| Function Type | Fermented Foods | Primary Strains | Interactions Between Strains | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Yogurt | Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus | S. thermophilus provides formic acid, folic acid, carbon dioxide, and fatty acids to initiate the growth of L. bulgaricus. L. bulgaricus produces excess peptides and free amino acids to meet the biosynthetic demands of S. thermophilus. | [83] |

| Fermented bean curd | Mucor, Lactobacillus, Bacillus and Saccharomyces | Mucor decomposes proteins and starch into peptides, amino acids, and monosaccharides, which are then utilized by yeast to produce alcohol, esters, and other aromatic compounds. | [84] | |

| Sourdough Bread | Saccharomyces exiguus and Lactic acid bacteria | Lactic acid bacteria convert sugars in flour into lactic acid and acetic acid, which yeast utilizes. The carbon dioxide produced by yeast causes the dough to rise, creating more space for lactic acid bacteria to thrive. | [85] | |

| Commensalism | Cheddar cheese | Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactococcus strains | S. thermophilus has a crucial role in boosting Lactococcus growth | [86] |

| Soy sauce | L. Fermentum and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii | L. Fermentum alleviates the inhibitory effect of acetic acid on Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, and its metabolites promote the growth of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii | [87] | |

| Baijiu | S. cerevisiae and Lactobacillus buchneri | Yeast and lactic acid bacteria synergistically enhance product yield while mutually supplying nutrients to promote growth and metabolic activity. | [32] | |

| Competition | Marula wine | Lactobacillus, Lactobacillus plantarum; luconobacter oxydans, Acetobacter pasteuriannus | Lactic acid bacteria inhibit the growth of acetic acid bacteria through malic acid-lactic acid fermentation. | [88] |

| Sausage | Debaryomyces hansenii (yeast), Penicillium and Aspergillu competing for limited resources | Yeast and mold protect the fermentation process internally by competing for resources, contributing unique flavors and textures to the sausage casing. Bifidobacteria metabolize carbohydrates to produce lactic acid and small amounts of acetic acid, lowering the product’s pH. | [89] |

3. Microbial Interactions in Fermented Foods of China’s Ethnic Minorities

3.1. Dong Ethnic Fermented Fish: A “Sour-Savory Symphony” Driven by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast

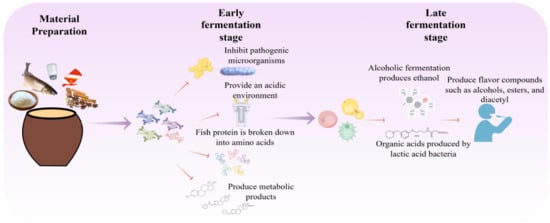

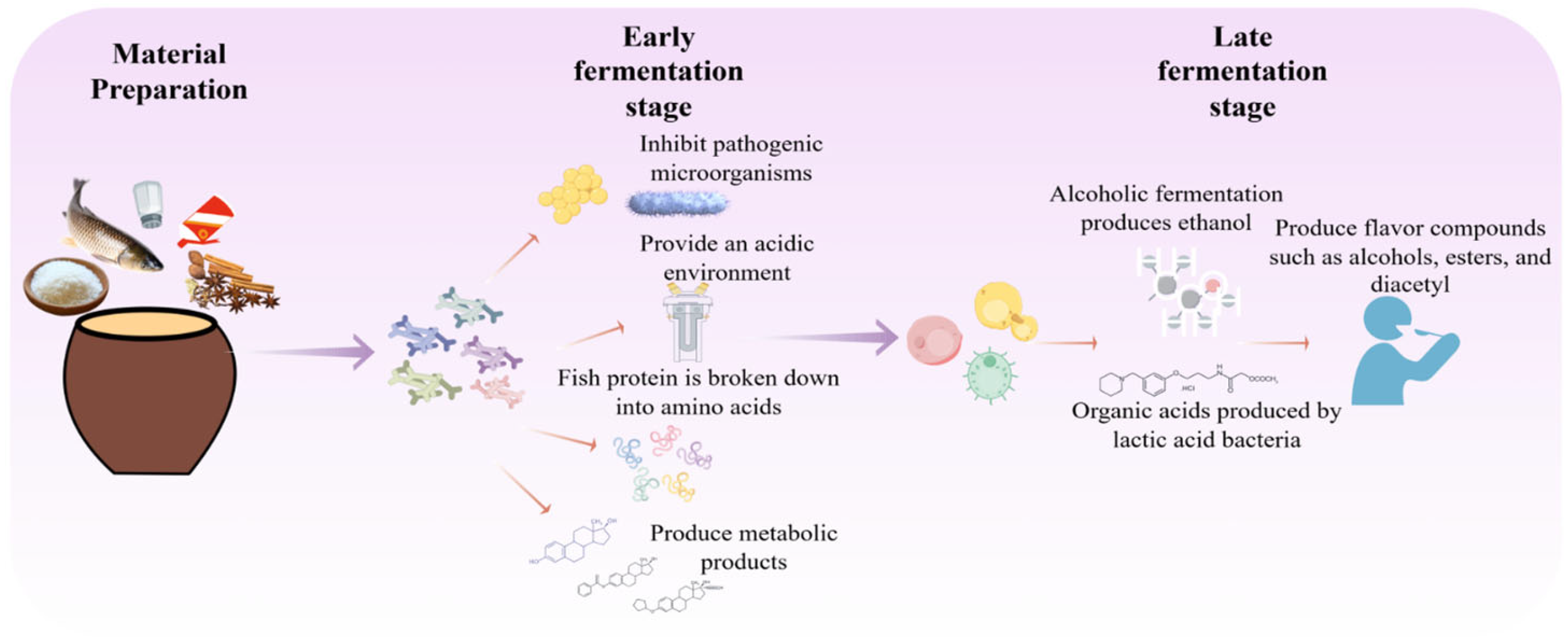

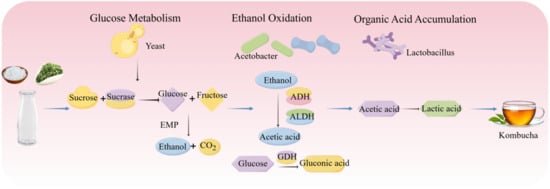

Fermented fish is a traditional preserved food of the Dong ethnic group in southwestern China, typically prepared by anaerobically fermenting fresh fish with glutinous rice, chili peppers, Sichuan peppercorns, and seasonings in sealed jars. The product exhibits a distinct sour-umami taste and a complex aroma [90]. Its fermentation is driven by a core consortium of LAB and yeasts, along with other bacteria such as Staphylococcus and Bacillus. The fermentation process of Dong fermented fish is depicted in Figure 3.

During the initial fermentation stage, lactic acid bacteria (primarily Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus brevis, and Lactobacillus curvatus, which are commonly found in fermented fish products [36]) proliferate rapidly. They produce large amounts of lactic acid, directly forming the characteristic sour flavor while inhibiting the growth of spoilage and pathogenic bacteria, thereby establishing a biologically selective environment that ensures product safety [91]. Simultaneously, the acidic environment promotes moderate hydrolysis of fish muscle proteins, softening the tissue and improving texture.

As fermentation progresses and the environment becomes highly acidic, acid-tolerant yeasts—including species such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hansenula anomala, Pichia spp., and Candida spp.—begin to thrive [92]. These yeasts utilize residual carbohydrates or metabolites to produce ethanol. Consistent with the shared mechanisms summarized in Section 2.4, this ethanol reacts with LAB-generated organic acids to form volatile esters, such as ethyl acetate and ethyl lactate [93]. These ester compounds are largely responsible for the fruity, floral, and wine-like notes that complement the foundational sourness, collectively creating the complex, well-rounded flavor profile typical of high-quality Dong fermented fish.

Recent omics-based studies have helped characterize the metabolic basis of flavor development and its association with microbial succession in fermented fish. Volatilomics and metabolomics analyses suggested that fermentation is accompanied by the accumulation of umami-related amino acids, succinic acid, and peptides, together with changes in taste-active nucleotides and key volatile compounds [94]. In parallel, combined HS-SPME-GC-MS and 16S rRNA sequencing with correlation network analysis indicated that alcohols, nitrogen-containing compounds, aldehydes, and esters are major volatile categories, and that specific bacterial taxa are associated with characteristic aroma compounds [95]. Notably, these omics results mainly provide correlative evidence; therefore, targeted validation remains necessary to confirm functional interactions. Supporting this point, co-culture experiments showed that yeast can promote LAB growth and shorten the lag phase, likely by increasing soluble nitrogen sources (e.g., peptides), while co-metabolism of amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid and aspartic acid) may contribute to volatile formation [96].

Figure 3.

Fermentation Process of Pickled Fish.

Figure 3.

Fermentation Process of Pickled Fish.

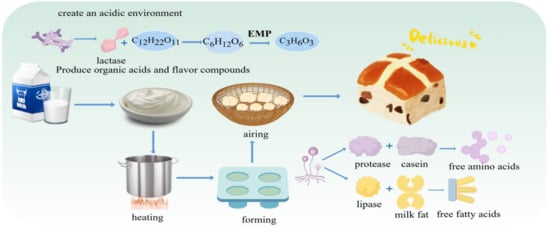

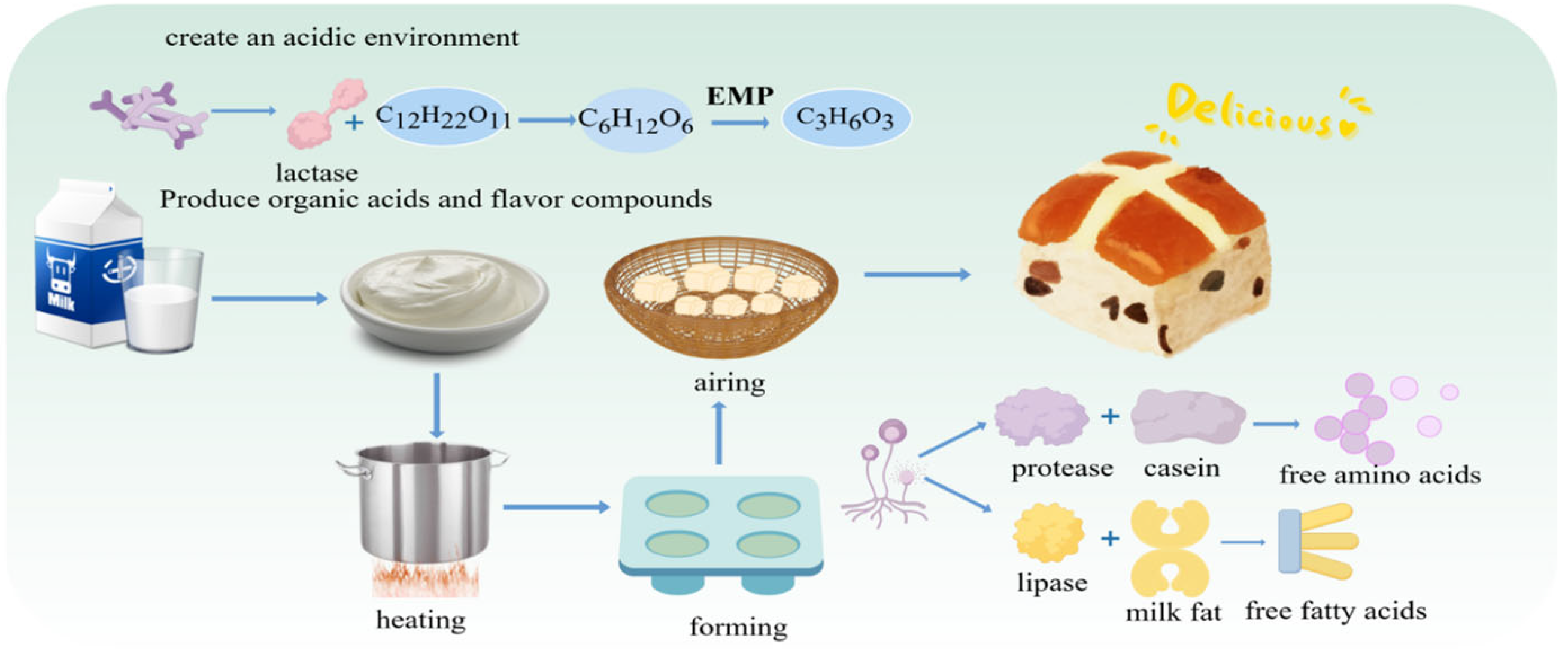

3.2. Milk Tofu: The “Flavor Shaping” by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Molds

Mongolian milk tofu, known as “Huruda” in Mongolian, is a traditional dairy product made from cow’s, sheep’s, or horse’s milk. It is produced by first fermenting the milk into yogurt via LAB, followed by heating, pressing, molding, and air-drying [97]. This process is not driven by a single microorganism but relies on a symbiotic community comprising LAB, yeasts, and molds. Through a series of synergistic, competitive, and antagonistic interactions, these microbes collectively drive key biochemical transformations, including protein conversion, lipid hydrolysis, flavor compound formation, and pathogen inhibition, ultimately shaping the product’s distinctive texture, flavor profile, and safety characteristics. The fermentation process of milk curd is shown in Figure 4.

Microbial interactions during Huruda production can be broadly described in three stages. Stage 1: Lactic Acid Fermentation. LAB like L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus dominate initially. Their rapid lactose metabolism produces large amounts of lactic acid, causing a sharp pH drop. This acidification serves two key purposes: (1) it coagulates milk proteins (e.g., casein) to form the foundational gel structure of the product, and (2) creates a selective acidic environment that inhibits spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms, ensuring biosafety and securing LAB’s ecological dominance [98].

Stage 2: Yeast Fermentation. As pH decreases, acid-tolerant yeasts (e.g., K. marxianus, S. cerevisiae) become active. Their interaction with LAB is crucial for flavor development. Yeast-produced alcohols esterify with LAB-derived acids (e.g., acetic, butyric acid) to form aromatic esters (e.g., ethyl acetate), imparting fruity and floral notes [12]. Yeast metabolism also generates various trace flavor compounds (aldehydes, ketones, sulfur-containing substances) [44], collectively building the rich, multi-layered flavor profile of high-quality milk curd.

Stage 3: Maturation and mold Activity. During shaping and air-drying, environmental molds (e.g., Penicillium, Aspergillus) may colonize the product. They secrete proteases and lipases that further break down proteins and lipids, releasing free amino acids, peptides, and fatty acids [99]. This enhances umami and richness while providing substrates for secondary flavor reactions (Maillard reaction, lipid oxidation), leading to more complex and mellow flavors [100]. This mold-driven biotransformation, often combined with specific aging techniques, represents a specialized, advanced stage of microbial succession in the fermentation system [101].

Figure 4.

Fermentation Process of Mongolian Milk Curd.

Figure 4.

Fermentation Process of Mongolian Milk Curd.

3.3. Miao Sour Soup: A Lactobacillus-Dominated “Sour-Aroma Ecosystem”

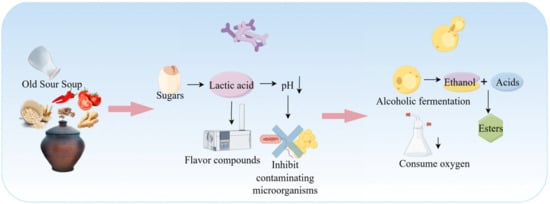

Miao sour soup is a traditional fermented condiment of southwestern China’s ethnic groups, known for its characteristic sour-umami flavor, digestibility, and extended shelf-life. This is achieved through a locally adapted fermentation system based on plant-based ingredients such as rice, flour, chili peppers, tomatoes, and ginger. The process is driven by a dynamic microbial consortium, predominantly composed of LAB, along with yeasts and minor AAB. Through syntrophic, cross-feeding, and competitive interactions, these microorganisms degrade macromolecules (e.g., starch, protein, cellulose), generating organic acids, free amino acids, volatile compounds, and bioactive metabolites. These products collectively contribute to the product’s reddish/translucent appearance, mellow sourness, and rich, lingering umami taste [102]. The fermentation process of Miao sour soup is shown in Figure 5.

This fermentation system represents a typical microecosystem with LAB as its absolute core. The dominant LAB populations mainly include Lactobacillus sporogenes, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and other Lactobacillus species [103]. During the initial fermentation stage, lactic acid bacteria rapidly metabolize fermentable sugars released from raw materials (such as glucose and maltose) to produce lactic acid through homofermentative or heterofermentative processes. This causes a sharp drop in the pH of the fermentation medium, effectively inhibiting the vast majority of spoilage microorganisms and potential foodborne pathogens while promoting the release of intracellular flavor precursors and nutrients [104]. The metabolic activities of LAB contribute a delicate tartness and a layered, complex sour aroma [105]. Furthermore, the combination of multiple LAB metabolites yields an acidity profile that is not sharp or one-dimensional, but rather mild, well-rounded, and characterized by a sophisticated aromatic bouquet [106].

As the initial sugar content declines and the acidic environment stabilizes, the ecological role of yeasts becomes increasingly prominent. Yeasts metabolize residual sugars and generate ethanol. As described in Section 2.4, this ethanol reacts with LAB-derived organic acids (e.g., lactic and acetic acids) to yield volatile esters such as ethyl acetate and ethyl lactate. These compounds impart characteristic fruity and wine-like aromas, which are key contributors to the ester-driven fragrance of sour soup. In a related study, Zhang et al. [107]. identified 35 volatile organic compounds in fermented sour soup, including 11 alcohols, 9 esters, 6 aldehydes, 5 ketones, 2 acids, 1 furan, and 1 ether, which collectively shape its complex aromatic profile.

Beyond aroma formation, yeast enzymatic activity significantly enhances flavor complexity. Yeast-secreted proteases and lipases degrade proteins and lipids, liberating free amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid, aspartic acid) and free fatty acids. These compounds function both as direct flavor contributors and as essential precursors for subsequent Maillard and Strecker reactions. Moreover, the limited consumption of organic acids and the buffering capacity of yeast metabolites modulate pH within the fermentation system, preventing over-acidification and thus contributing to long-term microbial stability and ecological equilibrium.

Figure 5.

Fermentation Process of Miao Sour Soup.

Figure 5.

Fermentation Process of Miao Sour Soup.

3.4. Manchurian Kombucha

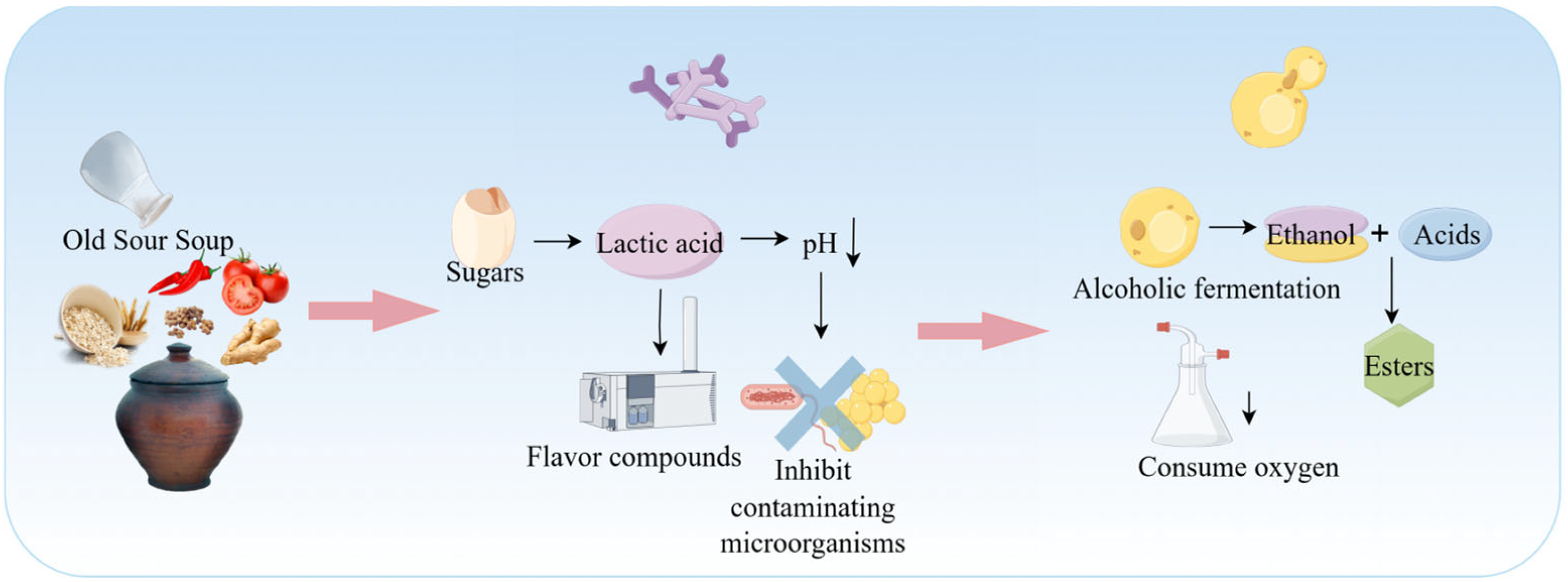

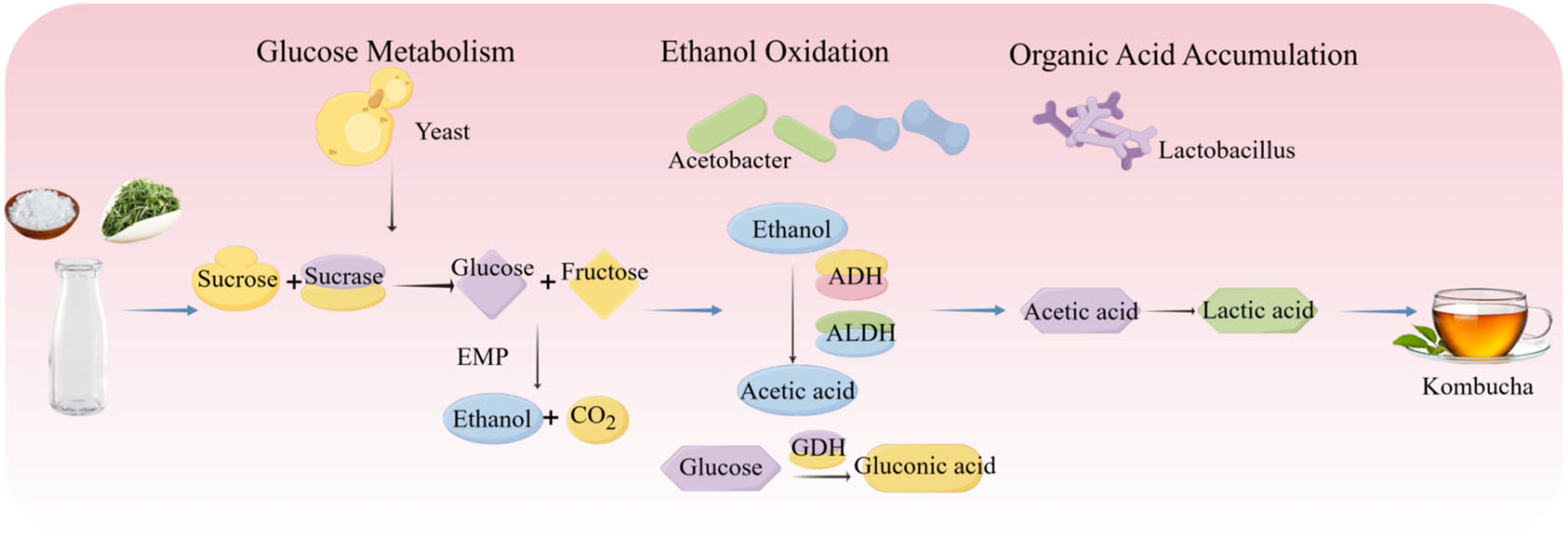

Kombucha is a traditional fermented tea beverage with origins in Northeast China thousands of years ago, and has since gained worldwide popularity [108]. It is produced by fermenting sweetened tea using a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), which generates a range of bioactive compounds and imparts its characteristic flavor profile. This process is driven by the interactions of multi-species microbial communities, primarily comprising yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces spp.), acetic acid bacteria (e.g., Acetobacter spp.), and lactic acid bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus spp.) [109]. Key metabolites such as ethanol, acetic acid, gluconic acid, and other organic acids are closely linked to both the distinct sensory properties and the potential health-related functions of kombucha [110]. The fermentation process of kombucha is shown in Figure 6.

During the fermentation of kombucha, yeasts, AAB, and LAB form a dynamic symbiotic network driven by a sequential metabolic cascade of “sugar catabolism–ethanol oxidation–organic acid accumulation.” The interplay of their metabolites and shifting environmental parameters collectively governs the progression of fermentation. In the initial phase, yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces boulardii hydrolyze sucrose and convert it to ethanol and CO2 [111]. Subsequently, consistent with the oxidative mechanisms described in Section 2.4, AAB (e.g., Acetobacter spp.) become increasingly active, oxidizing ethanol to acetic acid and directly converting glucose to gluconic acid [112]. In the later stages, LAB such as Lactobacillus plantarum further modulate acidity by converting acetic acid into lactic acid, thereby extending the metabolic chain and contributing to the overall acid profile [113]. Moreover, cross-feeding interactions among LAB, yeasts, and AAB significantly enhance the functional resilience and metabolic stability of the fermentation system. Notably, certain LAB strains can metabolize acetic acid to produce lactic acid, which helps regulate environmental acidity and creates favorable conditions for the growth of other community members [114,115]. These relationships are often inferred from compositional or correlative evidence, and targeted validation would strengthen causal interpretation.

The bioactive components in kombucha are derived both from the tea leaves themselves—such as polyphenols, polysaccharides, vitamins, minerals, and amino acids—and from the metabolic activities of the microorganisms involved in fermentation. Key bioactive compounds generated through microbial action include polyphenols, organic acids, vitamins, enzymes, and functional proteins such as bacteriocins [116]. In a study by Jafari et al. [117], black tea fermented at room temperature for 14 days showed increased invertase activity during fermentation, resulting in elevated polyphenol content and enhanced antioxidant capacity. Cardoso et al. [118] reported that kombucha prepared from black tea exhibited stronger antioxidant activity compared to that from green tea. The accumulation of lactic acid significantly lowers the pH of kombucha, thereby enhancing its antimicrobial properties [119]. During fermentation, certain LAB and yeast strains synthesize B-complex vitamins, such as thiamine (vitamin B1) [120]. Additionally, the presence of LAB facilitates the production of bioactive peptides and bacteriocins (e.g., nisin), which exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms like Listeria and Staphylococcus aureus [121].

Figure 6.

Fermentation Process of Kombucha.

Figure 6.

Fermentation Process of Kombucha.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Microbial interactions constitute not only the fundamental biological basis for the development of flavor and quality in traditional fermented foods, particularly those reviewed here from China’s ethnic minorities, but also serve as a critical link between natural ecosystems, ethnic food cultures, and food science. Analysis of representative examples—including Dong sour fish, milk tofu, Miao sour soup, and Manchurian kombucha—demonstrates that diverse microbial groups establish stable yet dynamic fermentation ecosystems through mutualistic, commensal, and competitive interactions. These interactions collectively drive substrate conversion, flavor formation, safety assurance, and functional improvement. This observation supports the view that fermentation is essentially a cooperative metabolic network supported by microbial communities through functional niche partitioning. The stability and functional diversity of this network directly govern the sensory properties, nutritional quality, and technological robustness of fermented food products.

4.1. Fermented Foods and Human Health

In food fermentation processes, bacteria, yeasts, and molds play essential roles in decomposing complex substrates and generating bioactive metabolites with significant health benefits. These range from supporting digestive function to modulating immune responses [122]. Moreover, recent research is increasingly focused on exploring novel and less-characterized microbial strains to achieve more specific and targeted health outcomes. Often isolated from distinct ecological niches or identified through advanced microbiological techniques, these strains possess unique metabolic profiles that may confer therapeutic advantages extending beyond general gut health [123]. In contrast to traditional probiotics, which primarily aim to maintain gut microbiome equilibrium [124], these emerging strains are being investigated for their potential in addressing specific health conditions, including mental well-being [125,126], immune regulation [127,128,129], metabolic health [130,131], and the prevention of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disorders [132,133] and diabetes [134,135]. By elucidating the distinct microbial transformations and bioactive compounds produced by such strains, researchers are paving the way for applications in precision nutrition and personalized health. This progress holds promise for developing targeted, strain-specific fermented foods and supplements tailored to individual health needs, thereby opening new frontiers at the intersection of fermentation science and human health.

4.2. Drawbacks in Traditional Fermented Food Production Methods

Traditional food fermentation, while embodying rich culinary heritage, faces limitations in meeting modern technological standards and consumer expectations [136]. A key challenge is the low standardization of production, which leads to inconsistent quality across batches and regions due to reliance on natural conditions and artisanal expertise, hindering large-scale industrialization [137]. Secondly, food safety remains a concern, as open fermentation environments risk contamination by pathogens or toxigenic molds, and inadequate process control may promote the formation of harmful compounds such as biogenic amines. The lack of real-time monitoring and prolonged fermentation cycles further reduce efficiency and increase costs [138]. Additionally, many traditional products depend on high salt or sugar content for preservation, conflicting with contemporary dietary guidelines that emphasize reduced sodium and sugar intake, thereby limiting their alignment with modern health-conscious trends.

4.3. Modern Technology Empowers Traditional Fermentation

To address the aforementioned limitations, modern technologies are injecting new vitality into traditional fermentation processes, offering promising pathways for future advancement. In the near term, priorities should focus on improving batch-to-batch consistency, safety control, and standardization; in the longer term, efforts can move toward more designable fermentation systems enabled by microbiome engineering and intelligent process control. Key research and development directions include:

4.3.1. Precise Microbiome Regulation and Engineered Microbial Consortia

Metagenomics and other high-throughput sequencing technologies enable comprehensive profiling of core microbial communities and their functional roles in traditional fermentations. This knowledge allows for the rational design of defined starter cultures by blending functionally characterized core strains—akin to formulating a microbial “prescription”—which can fundamentally enhance fermentation consistency, product stability, and safety [139]. Synthetic microbial ecology further supports the construction of tailored multi-strain consortia that work cooperatively to efficiently produce target flavor compounds or bioactive ingredients [140].

4.3.2. Real-Time Monitoring and Intelligent Process Control

The deployment of advanced sensor systems enables real-time tracking of key fermentation parameters such as pH, temperature, microbial biomass, and specific metabolite concentrations. Coupled with big-data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI), fermentation dynamics can be modeled and predicted, allowing for adaptive optimization and intelligent control of the process. AI-driven systems can autonomously adjust operational parameters to ensure consistent product quality across batches [141].

4.3.3. Targeted Flavor and Health-Oriented Design

Metabolic engineering strategies [142] can be applied to genetically modify or adaptively evolve production strains, enhancing their capacity to synthesize desirable flavor compounds while minimizing off-flavors or harmful metabolites. Additionally, novel fermentation agents [143] can be developed to rapidly establish dominance in low-salt or low-sugar environments, effectively suppressing contaminating microorganisms and enabling the production of fermented foods that align with modern health-conscious dietary preferences.

Looking forward, the production of traditional fermented foods is poised to evolve from an empirically dependent, environmentally variable process into a transparent, predictable, and designable system—termed “intelligent fermentation.” This paradigm shift is rooted in a deeper understanding of microbial ecology and fermentation dynamics, supported by advanced sensing, data integration, and bioprocess control. By integrating modern science with traditional wisdom, intelligent fermentation can retain the unique sensory and cultural attributes of heritage foods while systematically addressing their historical limitations. Ultimately, this approach will provide global consumers with fermented products that are safer, more consistent, and nutritionally tailored, with diverse sensory profiles [144].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.; methodology, X.J. and X.L.; investigation, P.S., Y.D., Z.W., S.M., W.W. and W.Z.; supervision, L.D.; project administration, L.D.; funding acquisition, S.D.; resources, S.D.; visualization, X.J.; writing—original draft, X.L.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and L.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Liaoning Provincial Science and Technology Plan Joint Plan (Natural Science Foundation-General Program) (No.2025-MSLH-016); Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2014020134); Liaoning Provincial Department of Education University Basic Scientific Research Surface Project (JYTMS20230376).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAB | acetic acid bacteria |

| LAB | lactic acid bacteria |

| EMP | Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas |

| LA | Lactic Acid |

| ADH | Alcohol Dehydrogenase |

| ALDH | Aldehyde Dehydrogenase |

| GDH | Glucose Dehydrogenase |

References

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, T.; Guo, R.; Ye, Q.; Zhao, H.; Huang, X. The regulation of key flavor of traditional fermented food by microbial metabolism: A review. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Jomaa, S.A.; El-Wahed, A.A.; El-Seedi, A.H.R. The Many Faces of Kefir Fermented Dairy Products: Quality Characteristics, Flavour Chemistry, Nutritional Value, Health Benefits, and Safety. Nutrients 2020, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Mu, D.; Guo, L.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, X. From flavor to function: A review of fermented fruit drinks, their microbial profiles and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuwendaal, N.K.; Stanton, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Beresford, T.P. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Ozaeta, I.; Astiazaran, O.J. Fermented foods: An update on evidence-based health benefits and future perspectives. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S.; Sarkar, P.; Sahoo, D.; Rai, A.K. Potential of fermented foods and their metabolites in improving gut microbiota function and lowering gastrointestinal inflammation. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2025, 105, 4058–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Zhang, M.; Fu, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Fang, X.; Li, Z.; Teng, T.; Shi, B. Branched Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Rich Fermented Protein Food Improves the Growth and Intestinal Health by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in Young Pigs. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2024, 72, 21594–21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rul, F.; Béra-Maillet, C.; Champomier-Vergès, M.C.; El-Mecherfi, K.E.; Foligné, B.; Michalski, M.C.; Milenkovic, D.; Savary-Auzeloux, I. Underlying evidence for the health benefits of fermented foods in humans. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 4804–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, R.; Schneider, E.; Gunnigle, E.; Cotter, P.D.; Cryan, J.F. Fermented foods: Harnessing their potential to modulate the microbiota-gut-brain axis for mental health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 158, 105562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Yang, W.G. Microbial diversity and metabolic pathways involved in flavor formation in Xiangxi sour meat. China J. Food Sci. 2025, 25, 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.X.; Li, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhao, X.Q.; Kang, C.Y.; Sun, J.L. Isolation, screening, and phenotypic characterization of lactic acid bacteria from traditional fermented sour fish. China J. Food Sci. 2024, 24, 380–391. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhou, R.; Ma, M. Integrated metabolomics and high-throughput sequencing to explore the dynamic correlations between flavor related metabolites and bacterial succession in the process of Mongolian cheese production. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Habib, A.; Ding, X.; Lv, H. Physiochemical and Microbial Analysis of Tibetan Yak Milk Yogurt in Comparison to Locally Available Yogurt. Molecules 2023, 28, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Han, F.; Wang, Z.; Du, M.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z. Screening of dominant strains in red sour soup from Miao nationality and the optimization of inoculating fermentation conditions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 9, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, B.; Li, Q.; Yang, C.; Yu, P.; Yang, X.; Li, T. Dynamic changes on sensory property, nutritional quality and metabolic profiles of green kernel black beans during Eurotium cristatum-based solid-state fermentation. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, J.; Lan, Y.; Lu, N.; Tian, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, Y. Bioaugmented ensiling of sweet sorghum with Pichia anomala and cellulase and improved enzymatic hydrolysis of silage via ball milling. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, C.; Bai, J.; Li, J.; Cheng, K.; Zhou, X.; Dong, Y.; Xiao, X. Fermented barley extracts with Lactobacillus plantarum dy-1 decreased fat accumulation of Caenorhabditis elegans in a daf-2-dependent mechanism. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Ushio, M.; Suzuki, K.; Abe, M.S.; Yamamichi, M.; Okazaki, Y.; Canarini, A.; Hayashi, I.; Fukushima, K.; Fukuda, S.; et al. Facilitative interaction networks in experimental microbial community dynamics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1153952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, X.; He, Y. Microbial Interactions in Food Fermentation: Interactions, Analysis Strategies, and Quality Enhancement. Foods 2025, 14, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, E.C.; Dutton, R.J. Putting microbial interactions back into community contexts. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 65, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzamourani, A.P.; Taliadouros, V.; Paraskevopoulos, I.; Dimopoulou, M. Developing a novel selection method for alcoholic fermentation starters by exploring wine yeast microbiota from Greece. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1301325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Miao, Y.; Liu, C.; Zong, M.; Lou, W. Investigation into optimizing fermentation processes to enhance uric acid degradation by probiotics. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 396, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Yi, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Synergistic Fermentation of Pichia kluyveri and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Integrated with Two-Step Sugar-Supplement for Preparing High-Alcohol Kiwifruit Wine. Metabolites 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizo, J.; Guillén, D.; Farrés, A.; Díaz-Ruiz, G.; Sánchez, S.; Wacher, C.; Rodríguez-Sanoja, R. Omics in traditional vegetable fermented foods and beverages. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 791–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, F.; Tucci, P.; Del Matto, I.; Marino, L.; Amadoro, C.; Colavita, G. Autochthonous Cultures to Improve Safety and Standardize Quality of Traditional Dry Fermented Meats. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawaz, H.; Bottari, B.; Scazzina, F.; Carini, E. Eastern African traditional fermented foods and beverages: Advancements, challenges, and perspectives on food technology, nutrition, and safety. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, G.; Li, J.; Cheng, P.; Song, Q.; Lv, W.; Wang, C. Starter molds and multi-enzyme catalysis in koji fermentation of soy sauce brewing: A review. Food Res. Int. 2024, 184, 114273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Liu, T.; Su, C.; Ji, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Evaluation of bacterial and fungal communities during the fermentation of Baixi sufu, a traditional spicy fermented bean curd. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2020, 100, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, L.; Gu, J.; Mu, G.; Tuo, Y. Screening lactic acid bacteria and yeast strains for soybean paste fermentation in northeast of China. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4502–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.; Yu, H.; Liu, J. Effect of the changs of microbial community on flavor components of traditional soybean paste during storage period. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Maske, B.; Murawski De Mello, A.F.; Da Silva Vale, A.; Prado Martin, J.G.; de Oliveira Soares, D.L.; De Dea Lindner, J.; Soccol, C.R.; de Melo Pereira, G.V. Exploring diversity and functional traits of lactic acid bacteria in traditional vinegar fermentation: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 412, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Zhou, J.; He, G. Effect of microbial interaction on flavor quality in Chinese baijiu fermentation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 960712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, B.; Huang, H.; Xu, J.; Xin, Y.; Hu, L.; Wen, L.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Han, Y.; Li, C. Rice Wine Fermentation: Unveiling Key Factors Shaping Quality, Flavor, and Technological Evolution. Foods 2025, 14, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. Characterization of microbiota of naturally fermented sauerkraut by high-throughput sequencing. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, S.; Lee, S.H.; Roh, S.W.; Son, H.; Whon, T.W. Does kimchi deserve the status of a probiotic food? Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 6512–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleggia, L.; Osimani, A. Fermented fish and fermented fish-based products, an ever-growing source of microbial diversity: A literature review. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ji, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, R.; Bai, T.; Hou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. A Review: Microbial Diversity and Function of Fermented Meat Products in China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 645435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettera, L.; Levante, A.; Bancalari, E.; Bottari, B.; Gatti, M. Lactic acid bacteria in cow raw milk for cheese production: Which and how many? Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1092224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, Y.; Degu, T.; Fesseha, H.; Mathewos, M. Isolation and Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Cow Milk and Milk Products. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 4697445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, P.; Yin, P.; Cai, J.; Jin, B.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S. Bacterial community succession and volatile compound changes in Xinjiang smoked horsemeat sausage during fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yang, L.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Fu, J.; Liu, G.; Kan, Q.; Ho, C.; Huang, Q.; Lan, Y.; et al. Applications of multi-omics techniques to unravel the fermentation process and the flavor formation mechanism in fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 8367–8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yu, L.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Narbad, A.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q.; Tian, F. Exploring Core fermentation microorganisms, flavor compounds, and metabolic pathways in fermented Rice and wheat foods. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Chang, C.; Jiang, T.; Zheng, T.; Ji, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pan, D.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Z. Antioxidant Peptides Derived from Cheese Products via Single and Mixed Lactobacillus Strain Fermentation. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2024, 72, 21221–21230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, C.; Wen, B.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, W. Combining Untargeted Metabolomics and High-Throughput Sequencing to Explore the Dynamics of Small-Molecular Metabolites in the Fermentation Stage of Inner Mongolian Cheese. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2025, 73, 20341–20351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Wee, S.; Ler, S.G.; Henry, C.J.; Gunaratne, J. Unraveling the impact of tempeh fermentation on protein nutrients: An in vitro proteomics and peptidomics approach. Food Chem. 2025, 474, 143154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, G.; Shitut, S.; Preussger, D.; Yousif, G.; Waschina, S.; Kost, C. Ecology and evolution of metabolic cross-feeding interactions in bacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 455–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auchtung, J.M.; Hallen-Adams, H.E.; Hutkins, R. Microbial interactions and ecology in fermented food ecosystems. Nat. Reviews. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Frank, D.; Zhao, J. Microbiological and biochemical performances of six yeast species as potential starter cultures for wet fermentation of coffee beans. LWT 2021, 137, 110430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Yin, Y.; Shang, M.; Liu, K.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, J. Effect on Arabica Coffee Flavor Quality of Enhanced Fermentation with Pichia membranifaciens Through Change Microbial Communities and Chemical Compounds. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, H.A.; Borém, F.M.; Alves, A.P.D.C.; Santos, C.M.D.; Schwan, R.F.; Haeberlin, L.; Nakajima, M.; Sugino, R. Natural fermentation with delayed inoculation of the yeast Torulaspora delbrueckii: Impact on the chemical composition and sensory profile of natural coffee. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassimiro, D.M.D.J.; Batista, N.N.; Fonseca, H.C.; Oliveira Naves, J.A.; Coelho, J.M.; Bernardes, P.C.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Wet fermentation of Coffea canephora by lactic acid bacteria and yeasts using the self-induced anaerobic fermentation (SIAF) method enhances the coffee quality. Food Microbiol. 2023, 110, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helena Sances Rabelo, M.; Meira Borém, F.; Paula De Carvalho Alves, A.; Soares Pieroni, R.; Mendes Santos, C.; Nakajima, M.; Sugino, R. Fermentation of coffee fruit with sequential inoculation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Effects on volatile composition and sensory characteristics. Food Chem. 2024, 444, 138608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janne Carvalho Ferreira, L.; Luiz Lima Bertarini, P.; Rodrigues Do Amaral, L.; Souza Gomes, M.D.; Maciel De Oliveira, L.; Diniz Santos, L. Coinoculation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens in solid-state and submerged coffee fermentation: Influences on chemical and sensory compositions. LWT 2024, 202, 116299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, I.C.; Laine, P.; Andreevskaya, M.; Paulin, L.; Kananen, S.; Tynkkynen, S.; Auvinen, P.; Smolander, O. Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of the microbial community in Swiss-type Maasdam cheese during ripening. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 281, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, T.; Hu, H.; Tian, J.; He, B.; Tai, J.; He, Y. Influence of Different Ratios of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus on Fermentation Characteristics of Yogurt. Molecules 2023, 28, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengler, K.; Zaramela, L.S. The social network of microorganisms—How auxotrophies shape complex communities. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 2018, 16, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki-Iwashima, A.; Matsuura, H.; Iwasawa, A.; Shiota, M. Metabolomics analyses of the combined effects of lactic acid bacteria and Penicillium camemberti on the generation of volatile compounds in model mold-surface-ripened cheeses. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canon, F.; Briard-Bion, V.; Jardin, J.; Thierry, A.; Gagnaire, V. Positive Interactions Between Lactic Acid Bacteria Could Be Mediated by Peptides Containing Branched-Chain Amino Acids. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 793136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, D.; Maistrenko, O.M.; Andrejev, S.; Kim, Y.; Bork, P.; Patil, K.R.; Patil, K.R. Polarization of microbial communities between competitive and cooperative metabolism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Whon, T.W.; Roh, S.W.; Jeon, C.O. Unraveling microbial fermentation features in kimchi: From classical to meta-omics approaches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 7731–7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Park, S.; Kim, E.; Cho, K.; Kwon, S.J.; Son, H. Effect of Fungi on Metabolite Changes in Kimchi During Fermentation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Hwang, I.M.; Lee, J. Temperature impact on microbial and metabolic profiles in kimchi fermentation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilelidou, E.A.; Nisiotou, A. Understanding Wine through Yeast Interactions. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Dana, F.; David, V.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R.; Hayar, S.; Colosio, M.; Alexandre, H. Bioprotection with Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A Promising Strategy. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlé, O.; Legrand, J.; Tesnière, C.; Pradal, M.; Mouret, J.; Nidelet, T. Investigations of the mechanisms of interactions between four non-conventional species with Saccharomyces cerevisiae in oenological conditions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e233285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, E.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Peng, Y.; Lai, J.; Sun, X.; Zeng, S.; Ao, L.; et al. Environmental factor driven microbial interactions regulate flavor metabolisms in polymicrobial fermented alcoholic beverages: A dynamic coupling framework. Food Res. Int. 2026, 225, 118097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Guardado, R.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B.; Reguant, C.; Bordons, A. Microbial interactions in alcoholic beverages. Int. Microbiol. Off. J. Span. Soc. Microbiol. 2022, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Varga, L.; Greff, B. Nutritional and functional aspects of European cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkers Rooijackers, J.C.M.; Turner, O.; Almekinders, E.; Smid, E.J. Spatial-temporal distribution of oxygen and its effect on microbial dynamics and vitamin B12 content in lupin tempeh. LWT 2024, 201, 116275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Han, X.; Xu, Y.; Mao, J. Environmental factors drive microbial succession and huangjiu flavor formation during raw wheat qu fermentation. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, C.; Qiu, F.; Peng, D.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Acid-resistant Bacillus velezensis effectively controls pathogenic Colletotrichum capsici and improves plant health through metabolic interactions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e325–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Ma, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, H.; Liu, X.; Tan, M.; Li, K. A review and prospects: Multi-omics and artificial intelligence-based approaches to understanding the effects of lactic acid bacteria and yeast interactions on fermented foods. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 99, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Maione, A.; Buonanno, A.; Guida, M.; Andolfi, A.; Salvatore, F.; Galdiero, E. Biological activities, biosynthetic capacity and metabolic interactions of lactic acid bacteria and yeast strains from traditional home-made kefir. Food Chem. 2025, 470, 142657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tian, J.; Li, L.; He, Y. Physiology, quorum sensing, and proteomics of lactic acid bacteria were affected by Saccharomyces cerevisiae YE4. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.; Roullier-Gall, C.; Verdier, F.; Martin, A.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Alexandre, H.; Grandvalet, C.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R. Microbial Interactions in Kombucha through the Lens of Metabolomics. Metabolites 2022, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Camacho, J.J.; Santos-Dueñas, I.M.; García-García, I.; García-Martínez, T.; Peinado, R.A.; Mauricio, J.C. Correlating Microbial Dynamics with Key Metabolomic Profiles in Three Submerged Culture-Produced Vinegars. Foods 2024, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Dai, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, K.; Rong, C.; et al. A Review on the Interaction of Acetic Acid Bacteria and Microbes in Food Fermentation: A Microbial Ecology Perspective. Foods 2024, 13, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.H.; Kim, M.K. Physiochemical Quality and Sensory Characteristics of koji Made with Soybean, Rice, and Wheat for Commercial doenjang Production. Foods 2020, 9, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, M.D.O.P.; Lima, F.R.; Passamani, F.R.F.; Santos, M.A.D.A.; Rezende, J.D.P.; Batista, L.R. Fungal and bacterial diversity present on the rind and core of Natural Bloomy Rind Artisanal Minas Cheese from the Canastra region, Brazil. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Du, B.; Li, X.; Sun, B. Targeted microbial collaboration to enhance key flavor metabolites by inoculating Clostridium tyrobutyricum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the strong-flavor Baijiu simulated fermentation system. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Han, M.; Chen, Y.; Ren, J.; Liu, T.; Liang, Y.; Hu, X.; et al. Microbial communities and metabolite dynamics in the flowering fermentation of Fu brick Tea: Correlations with mycotoxin degradation. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.A.; Kuipers, B.; Atashgahi, S.; Aalvink, S.; Smidt, H.; de Vos, W.M. Inter-species Metabolic Interactions in an In-vitro Minimal Human Gut Microbiome of Core Bacteria. npj Biofilms Microbomes 2022, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Mu, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Z.; et al. Fermentation characteristics and postacidification of yogurt by Streptococcus thermophilus CICC 6038 and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus CICC 6047 at optimal inoculum ratio. J. Dairy. Sci 2024, 107, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Dong, Z.; Hao, T. High-throughput sequencing-based study on bacterial community structure and functional prediction of fermented bean curd from different regions in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Qiao, N.; Bechtner, J. The quest for the perfect loaf of sourdough bread continues: Novel developments for selection of sourdough starter cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 407, 110421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkonian, C.; Zorrilla, F.; Kjærbølling, I.; Blasche, S.; Machado, D.; Junge, M.; Sørensen, K.I.; Andersen, L.T.; Patil, K.R.; Zeidan, A.A. Microbial interactions shape cheese flavour formation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, W.; Huang, M.; Su, G.; Zhao, M.; Feng, Y. Mechanistic insights into soy sauce flavor enhancement via Co-culture of Limosilactobacillus fermentum and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, A.; La Grange, D.; Moganedi, K. Microbial and Chemical Dynamics during Marula Wine Fermentation. Beverages 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.; Andrade, M.J.; Cebrián, E.; Roncero, E.; Delgado, J. Perspectives on the Probiotic Potential of Indigenous Moulds and Yeasts in Dry-Fermented Sausages. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Luo, K.L. A study on Dong sour fish culture from the perspective of ecological ethnology. J. Guangxi Norm. Univ. Natl. 2021, 38, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J. Identification of Key Characteristic Flavor Compounds in Fermented Sour Fish and the Improvement Effect of Aroma-Producing Yeasts. Master’s Thesis, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.P.; You, S.B.; Ma, D.Y.; Xia, H.; Bian, F.; Geng, Y.; Shi, S.T.; Yu, J.H.; Bi, Y.P. Screening of high-protease-producing strains and evaluation of their effects on the bioactivity of Spirulina fermentates. Food Ferment. Ind. 2021, 47, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Huang, Y.Q.; Li, X.H.; Wang, F.X.; Ma, X.Y. Research progress on microbial community composition and its correlation with flavor metabolism in fermented fish products in China. Food Sci. 2024, 45, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Dong, M.; Dong, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, B.; Qin, L. Integrated volatolomics and metabolomics analysis reveals the characteristic flavor formation in Chouguiyu, a traditional fermented mandarin fish of China. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, S. Contribution of autochthonous microbiota succession to flavor formation during Chinese fermented mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, L.; Xie, M.; Rong, Z.; Yin, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Microbial interactions between Lactoplantibacillus plantarum and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa in the fermented fish juice system. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Study on Traditional Mongolian Food Processing Techniques. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qigeqi. Study on Traditional Milk Tofu Starters and Their Applications. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Daling. Composition and Changes of Microbial Communities during Traditional Milk Tofu Production. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Ai, N.S.; Cao, Y.P. Characterization of the key odorants in kurut with aroma recombination and omission studies. J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 4164–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Tegexibayaer; Li, C.; Yang, B.; Guo, L. Isolation and identification and lipase activity of mold in Mongolian Hurood. China Brew. 2023, 42, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, F.; Luo, Y.; Li, D.; Zhong, D.; He, G.; Wei, Z.; Jia, L. Kaili Red sour soup: Correlations in composition/microbial metabolism and flavor profile during post-fermentation. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137602. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, W.; He, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Feng, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L. Effects of post-fermentation on the flavor compounds formation in red sour soup. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1007164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Xie, L.; Li, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, L. The Correlation Mechanism between Dominant Bacteria and Primary Metabolites during Fermentation of Red Sour Soup. Foods 2022, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zeng, J.; Tian, Q.; Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X. Effect of the bacterial community on the volatile flavour profile of a Chinese fermented condiment—Red sour soup—During fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2022, 155, 111059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Jiang, J.; Feng, D.; Shi, Y.; Hu, P. Comparison of Fermentation Behaviors and Characteristics of Tomato Sour Soup between Natural Fermentation and Dominant Bacteria-Enhanced Fermentation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Hu, M.; Meng, W.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, S. Microbial community structure analysis and screening of dominant strains in Guizhou white sour soup: Enhancing safety, improving flavor, and shortening fermentation cycle. Food Chem. X 2025, 30, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.; Zhang, X.; Mutukumira, A.N. Kombucha: Production and Microbiological Research. Foods 2022, 11, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Li, M.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.; Chen, G.; Lao, F.; Wu, J. Comparative genomics and fermentation flavor characterization of five selected lactic acid bacteria provide predictions for flavor biosynthesis metabolic pathways in fermented muskmelon puree. Food Front. 2024, 5, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y. Decoding the dynamic evolution of volatile organic compounds of dark tea during solid-state fermentation with Debaryomyces hansenii using HS-SPME-GC/MS, E-nose and transcriptomic analysis. LWT 2025, 223, 117765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Ho, C.; Wang, Y.; Cai, T.; Li, S.; Ma, J.; Guo, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Effect of inoculation with different Eurotium cristatum strains on the microbial communities and volatile organic compounds of Fu brick tea. Food Res. Int. 2024, 197, 115219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tso, N.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, R. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Microbial Synergistic Metabolic Mechanisms and Health Benefits in Kombucha Fermentation: A Review. Biology 2025, 14, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureys, D.; Britton, S.J.; De Clippeleer, J. Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2020, 78, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Fan, L.Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, L. Research progress on the development and utilization of functional microorganisms in kombucha. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2024, 45, 388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, D.K.A.; Wang, B.; Lima, E.M.F.; Shebeko, S.K.; Ermakov, A.M.; Khramova, V.N.; Ivanova, I.V.; Rocha, R.D.S.; Vaz-Velho, M.; Mutukumira, A.N.; et al. Kombucha: An Old Tradition into a New Concept of a Beneficial, Health-Promoting Beverage. Foods 2025, 14, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolak, H.; Piechota, D.; Kucharska, A. Kombucha Tea-A Double Power of Bioactive Compounds from Tea and Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeasts (SCOBY). Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, R.; Naghavi, N.S.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Doudi, M.; Shahanipour, K. Kombucha microbial starter with enhanced production of antioxidant compounds and invertase. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.R.; Neto, R.O.; Dos Santos D’Almeida, C.T.; Do Nascimento, T.P.; Pressete, C.G.; Azevedo, L.; Martino, H.S.D.; Cameron, L.C.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Barros, F.A.R.D. Kombuchas from green and black teas have different phenolic profile, which impacts their antioxidant capacities, antibacterial and antiproliferative activities. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, E.; Hashemi, S.M.B. Lactic acid production—Producing microorganisms and substrates sources-state of art. Heliyon 2020, 6, e4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, M.D.M.; de Moreno De LeBlanc, A.; Savoy De Giori, G.; LeBlanc, J.G. Thiamine-producing lactic acid bacteria and their potential use in the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voidarou, C.; Antoniadou, M.; Rozos, G.; Tzora, A.; Skoufos, I.; Varzakas, T.; Lagiou, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Fermentative Foods: Microbiology, Biochemistry, Potential Human Health Benefits and Public Health Issues. Foods 2020, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, N.; Aslan, M.; Yesilcimen Akbas, M.; Ozcan, F.; Sar, T.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Effects of fungal based bioactive compounds on human health: Review paper. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 7004–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Li, H.; OHair, J.; Bhatti, S.; Chen, F.; Nasr, K.A.; Johnson, T.; Zhou, S. Biochemical Characteristics of Microbial Enzymes and Their Significance from Industrial Perspectives. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019, 61, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Delgado, S.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Lourenço, A.; Gueimonde, M.; Margolles, A. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 10–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berding, K.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Moloney, G.M.; Boscaini, S.; Strain, C.R.; Anesi, A.; Long-Smith, C.; Mattivi, F.; Stanton, C.; Clarke, G.; et al. Feed your microbes to deal with stress: A psychobiotic diet impacts microbial stability and perceived stress in a healthy adult population. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawky, E.; Surendran, S.; El-Khair, R.M.A. Fermented Vegetables as a Source of Psychobiotics: A Review of the Evidence for Mental Health Benefits. In Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, Y.; Kwon, K.H.; Jung, Y.J. Probiotic Functions in Fermented Foods: Anti-Viral, Immunomodulatory, and Anti-Cancer Benefits. Foods 2024, 13, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.H.; Randhawa, S.K.; Meisel, M. Dietary Commensal Wrestles Iron from Tumor Microenvironment to Activate Antitumoral Macrophages. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2400–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, M.; Manjunath, A.; Halami, P.M. Effect of probiotics as an immune modulator for the management of COVID-19. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowska-Rojek, A.; Tyski, S. How to Improve Health with Biological Agents-Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Negi, P.S. Appraising the role of biotics and fermented foods in gut microbiota modulation and sleep regulation. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e17634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Gancarz, M.; Szymańska, J. Role of Gut Microbiota, Probiotics and Prebiotics in the Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules 2021, 26, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Singh, V.; Sharma, K.; Sliti, A.; Baunthiyal, M.; Shin, J. Significance of Soy-Based Fermented Food and Their Bioactive Compounds Against Obesity, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2024, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluzio, M.D.C.G.; Dias, M.D.M.E.; Martinez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. Kefir and Intestinal Microbiota Modulation: Implications in Human Health. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 638740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Butani, K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Prajapati, B.G. Effects of Fermented Food Consumption on Non-Communicable Diseases. Foods 2023, 12, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Zhao, Y.; Xin, S.; Li, T.; Xu, Y. Solid-State Fermentation Engineering of Traditional Chinese Fermented Food. Foods 2024, 13, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L. Research on Safety Risk Control and Management of Traditional Fermented Foods. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Economics and Business, Shijiazhuang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elhalis, H.; Chin, X.H.; Chow, Y. Soybean fermentation: Microbial ecology and starter culture technology. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 7648–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, L.X.; Tan, X.; Ji, Q.; Qiao, C.; Pan, L. Research progress on traditional fermented foods based on omics approaches. China J. Food Sci. 2025, 25, 486–500. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Qu, G.; Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Du, G.; Fang, F. Synergistic Fermentation with Functional Microorganisms Improves Safety and Quality of Traditional Chinese Fermented Foods. Foods 2023, 12, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; Song, J.; Liu, C.; Lin, R.; Liang, D.; Aweya, J.J.; Weng, W.; Zhu, L.; Shang, J.; Yang, S. Synthetic microbial communities: Novel strategies to enhance the quality of traditional fermented foods. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Xiang, H.; Wu, Y.; Sun-Waterhouse, D. Transforming the fermented fish landscape: Microbiota enable novel, safe, flavorful, and healthy products for modern consumers. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 3560–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysin, A.P.; Egorov, A.R.; Godzishevskaya, A.A.; Kirichuk, A.A.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kritchenkov, A.S. Biologically Active Supplements Affecting Producer Microorganisms in Food Biotechnology: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, S.D.; Zhang, J.X.; Zong, C.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Zhang, Z.M.; Dou, S.H.; Liang, L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, F. From traditional fermented foods to “big health” foods: New opportunities for functional microorganisms. China Brew. 2025, 44, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.