Abstract

Citrus fruits are susceptible to ‘Huanglongbing’, leading to widespread antibiotic use during planting. Additionally, to enhance economic efficiency, plant growth regulators (PGRs) are also applied to citrus fruits. To rapidly screen for antibiotics and plant growth regulators in citrus fruits, a method was developed for the simultaneous detection of exogenous contaminants in mandarin, orange, pomelo, and lemon using QuEChERS combined with liquid chromatography–quadrupole/orbitrap mass spectrometry. By comparing the responses or recoveries of compounds under different conditions, the optimal extraction and purification were determined. The method was used to verify the methodological parameters for four citrus fruits. The results showed that the detection limits for 10 antibiotics and 53 plant growth regulators in the four citrus fruits ranged from 1 to 50 μg/kg, and the limits of quantitation ranged from 1 to 80 μg/kg. And the coefficient of determination (R2) was ≥ 0.99. The recovery of all compounds was between 60% and 120%, and the relative standard deviation (RSD) was less than 20%. The method was applied to the 42 real samples, and a total of nine compounds were detected at concentrations ranging from 0.002 to 0.852 mg/kg. The results demonstrated that the method was simple, sensitive, accurate, and reliable, making it suitable for detecting antibiotics and plant growth regulators in citrus fruits.

1. Introduction

Citrus fruits (Citrus L.), derived from Rutaceae shrubs, originated in Southeast Asia, such as Yunnan Province of China, Myanmar, etc. It is the fruit with the highest cultivation area and yield in the world. Primary cultivated varieties include mandarin, orange, pomelo, lemon, and kumquat [1,2]. Huanglongbing (HLB) is the most destructive disease of citrus fruit. After infection, fruit yield is reduced, or no harvest occurs, a condition called “citrus cancer” [3]. The pathogen was a Gram-negative bacterium, including the Asian strain (CLas), the American strain (CLam), and the African strain (CLaf). Only CLas was found in China [4,5,6]. Since the 1970s, China has studied the use of antibiotics to prevent and treat HLB. Oxytetracycline, tetracycline, streptomycin, and ampicillin can effectively suppress the pathogen through scion soaking, trunk injection, or foliar spraying [7,8,9]. Among them, oxytetracycline and streptomycin were approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for prevention and treatment [10]. However, the application of these antibiotics raises concerns about pathogen resistance and the risk of cross-species transmission, which may affect the health of animals and humans via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) [11]. At the same time, some countries, such as the European Union and the United States, have established maximum residue limits (MRLs) for antibiotics in citrus fruits [12]. Therefore, the establishment of rapid detection methods for antibiotics in citrus fruits is critical to ensure their quality and safety.

Plant growth regulators (PGRs) are organic compounds, either extracted from microorganisms or chemically synthesized, that mimic the chemical structures and physiological effects of natural plant hormones. PGRs can enhance fruit quality and increase yield and are extensively utilized in modern agricultural production [13,14,15]. The impact of PGRs on plant growth and development is indeed significant, even at low concentrations. For example, spraying early-ripening pomelos with 0.1% brassinosteroids increased yield by 72% [16]. Nevertheless, their excessive application is not without risks, as it can readily induce phytotoxicity, including fruit deformity and a decline in tree vigor [17], posing a serious threat to fruit marketability and the sustainable management of orchards. Therefore, the establishment of rapid detection methods for PGR residues in citrus fruits is essential, as it will be a crucial step toward promoting the high-quality and sustainable development of the citrus industry.

According to the literature, detection methods for antibiotics have been established for animal-derived foods [18,19]. However, some literature reports on the detection technology for antibiotic residues in plant-derived foods [20,21], indicating that their presence is becoming increasingly common. At the same time, because of the higher infection rate of HLB in citrus fruits, antibiotics were used to prevent and treat HLB, and antibiotic residues will appear in citrus fruits. On the contrary, the detection methods for PGRs in plant-derived foods are more mature than those for antibiotics [22,23]. Although PGR methods are numerous, the detection samples are mainly singular, and the detection instruments are mostly LC-MS/MS. For example, Su et al. established a method for pesticides and PGRs in cherries by LC-MS/MS and used the technology to detect compounds in cherry cultivation in the main areas [24]. Yue et al. used QuEChERS combined with LC-MS/MS to detect 19 PGRs and fungicides in Radix Ophiopogonis, and the limit of quantification (LOQ) was 0.16–5.61 μg/kg [25]. The above detection methods are sensitive; they have the disadvantages of limited target compounds and incomplete detection, making it challenging to meet the needs of high-throughput detection. In recent years, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) technology has become increasingly popular and is widely used to detect chemical hazards, such as pesticides and veterinary drugs. This technology not only detects various compounds but also offers additional advantages for screening unknown compounds [26]. To realize the simultaneous and rapid detection of antibiotics and PGRs in citrus fruits, based on liquid chromatography–quadrupole/electrostatic field orbitrap mass spectrometry (LC-Q-orbitrap/MS), a method for the simultaneous determination of 10 antibiotics and 53 plant growth regulators in citrus (including mandarin, orange, grapefruit and lemon) was established by optimizing the preparation conditions and successfully applied to the analysis of actual samples. The purpose of this study is to provide robust technical support for the monitoring of exogenous pollutants in citrus to promote the high-quality, sustainable development of the industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

The ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole/orbitrap mass spectrometry consisted of the Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in conjunction with Q-Orbitrap mass spectrometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Bremen, Germany). AH-30 Fully Automatic Homogenizer and Auto EVA 80 Fully Automatic Parallel Nitrogen Blowing Concentrator were obtained from Raykol Instrument Co., Ltd. (Xiamen, China); PL602-L electronic balance was purchased from Mettler-Toledo (Zurich, Switzerland); SR-2DS oscillator (Taitec, Saitama, Japan), a KDC-40 low-speed centrifuge (Zonkia, Hefei, China), ultrasonic cleaner (Kunshan, China), and a Milli-Q ultrapure water machine (Milford, MA, USA) were also purchased.

2.2. Materials and Reagents

The standards of 63 compounds (purity grade, >92%) were from Alta Company (Alta, Tianjin, China); ceramic homogenizer was from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA); formic acid, ammonium acetate, methanol, and acetonitrile (all LC-MS grade) were obtained from Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA); and acetic acid, NaCl, anhydrous Na2SO4, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, disodium hydrogen phosphate, and citric acid (analytical grade forms) were obtained from Beijing Chemical Plant (Beijing, China). The appropriate sorbent of primary secondary amine (PSA) and octadecylsilane (C18) were obtained from Tianjin Agela Technology (Tianjin, China).

2.3. Standard Solution Preparation

A total of 10 antibiotics and 53 plant growth regulators were transferred into a 10 mL brown volumetric flask, and the volume was adjusted to scale with methanol. After ultrasound, a mixed standard working solution of 10 mg/L was obtained and stored in a brown storage liquid bottle. The solution was stored at 4 °C in the dark.

2.4. Sample Collection

A total of 42 samples (14 mandarin, 10 orange, 8 pomelo, and 10 lemon) were collected from fruit stores and supermarkets in Beijing, and all weighed more than 500 g. The sample was ground using a homogenizer after removing the fruit stalk and stored at −20 °C.

2.5. Instrument Parameters

Chromatographic separation was achieved under the following chromatographic conditions: equipped with reversed-phase chromatography column (Accucore aQ 150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm); column temperature: 40 °C; injection volume: 5 µL; mobile phases A and B were 5 mM ammonium acetate −0.1% formic acid–water and 0.1% formic acid–methanol, respectively; gradient elution program, 0 min to 3 min; the mobile phase B was 1% to 30%; 3 min to 6 min, the mobile phase B was 30% to 40%; from 6 min to 9 min, the mobile phase B was 40%; from 9 min to 15 min, the mobile phase B was 40% to 60%; from 15 min to 19 min, the mobile phase B was 60% to 90%; from 19 min to 23 min, the mobile phase B was 90%; from 23 min to 23.01 min, the mobile phase B was 90% to 1% (run after 4 min); flow rate was 0.4 mL/min.

Heated Electrospray Ionization (HESI) was used on the Q-Orbitrap in negative and positive ionization modes. The conditions for electrospray ionization were set as follows: scan mode: full scan/data dependent secondary scan (Full MS/dd-MS2); Full MS scan range: 80–1100 m/z; resolution: 70,000 Full Width at Half Maximum (FHWM), Full MS; and MS2 was 17,500 FHWM; maximum injection time was 200 ms and 60 ms for Full MS and MS2; automatic gain control of Full MS and MS2 was 1 × 106 and 2 × 105, respectively; loop count and multiplex count were 1; Isolation width: 2.0 m/z; under fill ratio: 1%; stepped normalized collision energy: 20, 40, and 60; apex trigger: 2–6 s; and dynamic exclusion: 8 s. The information on MS is in Table 1.

Table 1.

The information on 10 antibiotics and 53 plant growth regulators.

2.6. Sample Preparation

Accurately weigh 10 g (±0.01 g) of the sample into a 100 mL centrifuge tube, add 5 mL of Na2EDTA-Mcllvaine buffer solution (37.2 g ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, 27.5 g disodium hydrogen phosphate and 12.0 g citric acid, water volume to 1000 mL, and adjust pH to 4.0) and 20 mL of 3% acetic acid acetonitrile, and homogenize for 1 min. Then, the ceramic homogenizer, 4 g anhydrous Na2SO4, and 1 g NaCl were added, shaken for 20 min, and centrifuged at 4500 r/min for 5 min. A total of 8 mL of the supernatant was added to a centrifuge tube (containing 100 mg C18 and 200 mg anhydrous MgSO4), shaken for 10 min, and centrifuged at 4500 r/min for 5 min. After which, 4 mL of the supernatant was pipetted into a tube, evaporated to dryness in a 40 °C water bath under a gentle stream of nitrogen, then dissolved in 1 mL of acetonitrile/water (3:2, v/v), and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter for LC-Q-Orbitrap/MS analysis.

2.7. Method Validation

The method was validated across four citrus fruits by evaluating matrix effect, limits of detection (LODs), limits of quantification (LOQs), accuracy, and precision. Matrix effects were evaluated by comparing the slope of the matrix-matched calibration curve with the solvent calibration curve. LOD and LOQ were the signal-to-noise ratios (S/N) ≥ 3 and the signal-to-noise ratios (S/N) ≥ 10 at the lowest addition level of the compound, respectively. Meanwhile, the recovery ranged from 60% to 120%, and the relative standard deviation (RSD) was <20% for LOQ. The accuracy and precision of the compounds were verified at 1× LOQ, 2× LOQ, and 10× LOQ, with six replicates at each spiked level.

Thermo Fisher Scientific TM Tracefinder TM (version 4.1, Waltham, MA, USA) software was used to analyze the data based on the self-built database. The data results were analyzed using Excel (Version 2019) software, and an analysis of graphs was drawn using Origin 2024 software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Extraction Solvent Acidity and Volume

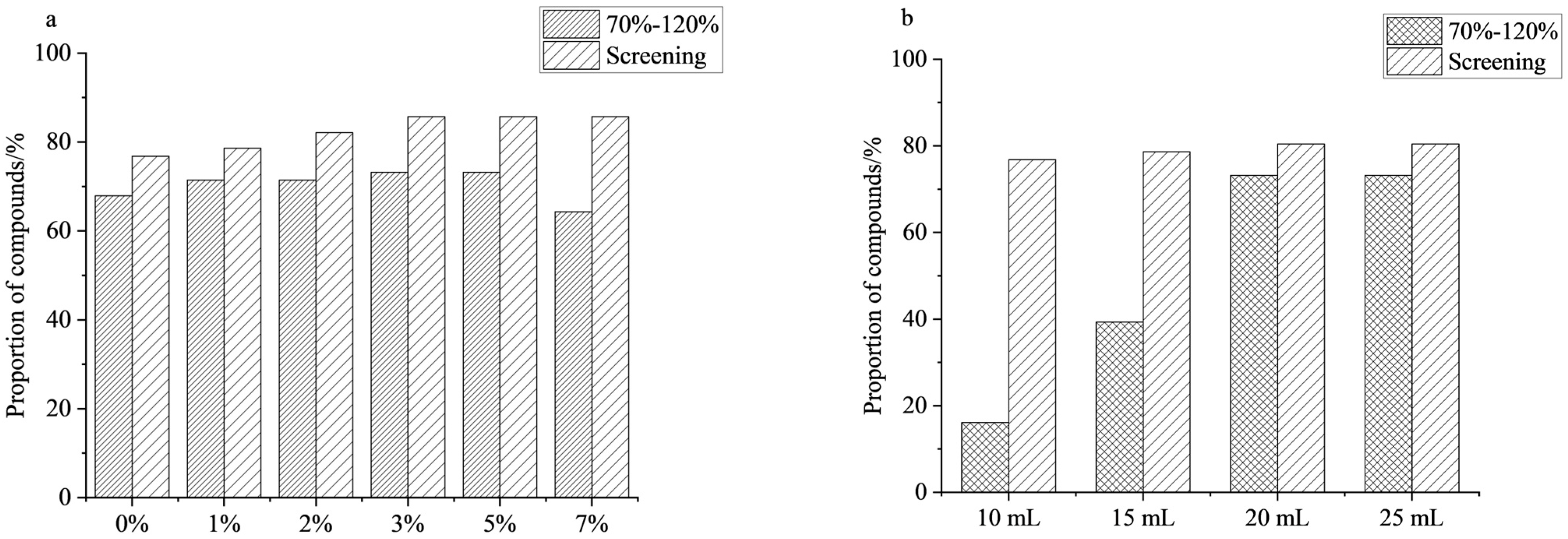

Acetonitrile was employed as the extraction solvent due to its strong polarity, which enables efficient extraction of compounds while significantly reducing co-soluble impurities [27,28]. According to the literature, most PGRs exhibit higher extraction efficiency under acidic conditions, with substantially greater stability than under neutral conditions [29]. Therefore, using mandarin as a matrix, this study compared the extraction recoveries of the compounds using acetonitrile with different concentrations of acetic acid (0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 5%, 7%). As shown in Figure 1a, with increasing acetic acid concentration, the number of compounds with recoveries in the 70–120% range increased first, then decreased. Optimal recovery was observed at acetic acid concentrations of 3–5%. Under these conditions, 73.2% of the compounds met the recovery criteria, and 85.7% were successfully detected. When the acetic acid content was further increased to 7%, the proportion of compounds satisfying the recovery criteria decreased to 64.3%, while the detection rate remained unchanged. In summary, 3% and 5% acetic acid in acetonitrile provided the best extraction performance. Between them, 3% acetic acid in acetonitrile was ultimately selected as the optimal extraction condition for subsequent analysis.

Figure 1.

Effect of extraction solvents on the proportion of compounds: (a) acidity of extraction solvents; (b) volume of extraction solvents (n = 3).

To further enhance extraction efficiency, the effect of extraction solvent volume (10, 15, 20, and 25 mL) on compound recovery was investigated. The results are shown in Figure 1b; the number of recoveries for the compounds increased with increasing extraction volume. When the extraction volume was 10 mL, only nine compounds met the recovery criteria, yielding a qualified rate of 16.1%, indicating that insufficient solvent volume hampered complete extraction. As the extraction volume increased, the number of compounds meeting the recovery criteria gradually increased. When the volume increased to 20 mL, the number of qualified compounds reached a maximum, 4.6 times that at 10 mL. However, when the volume was further expanded to 25 mL, the number of qualified compounds remained the same as at 20 mL, and the RSD increased, indicating reduced repeatability. Based on the experimental results, 20 mL was finally determined to be the optimal extraction solvent volume.

3.2. Optimization of the Type of Salt

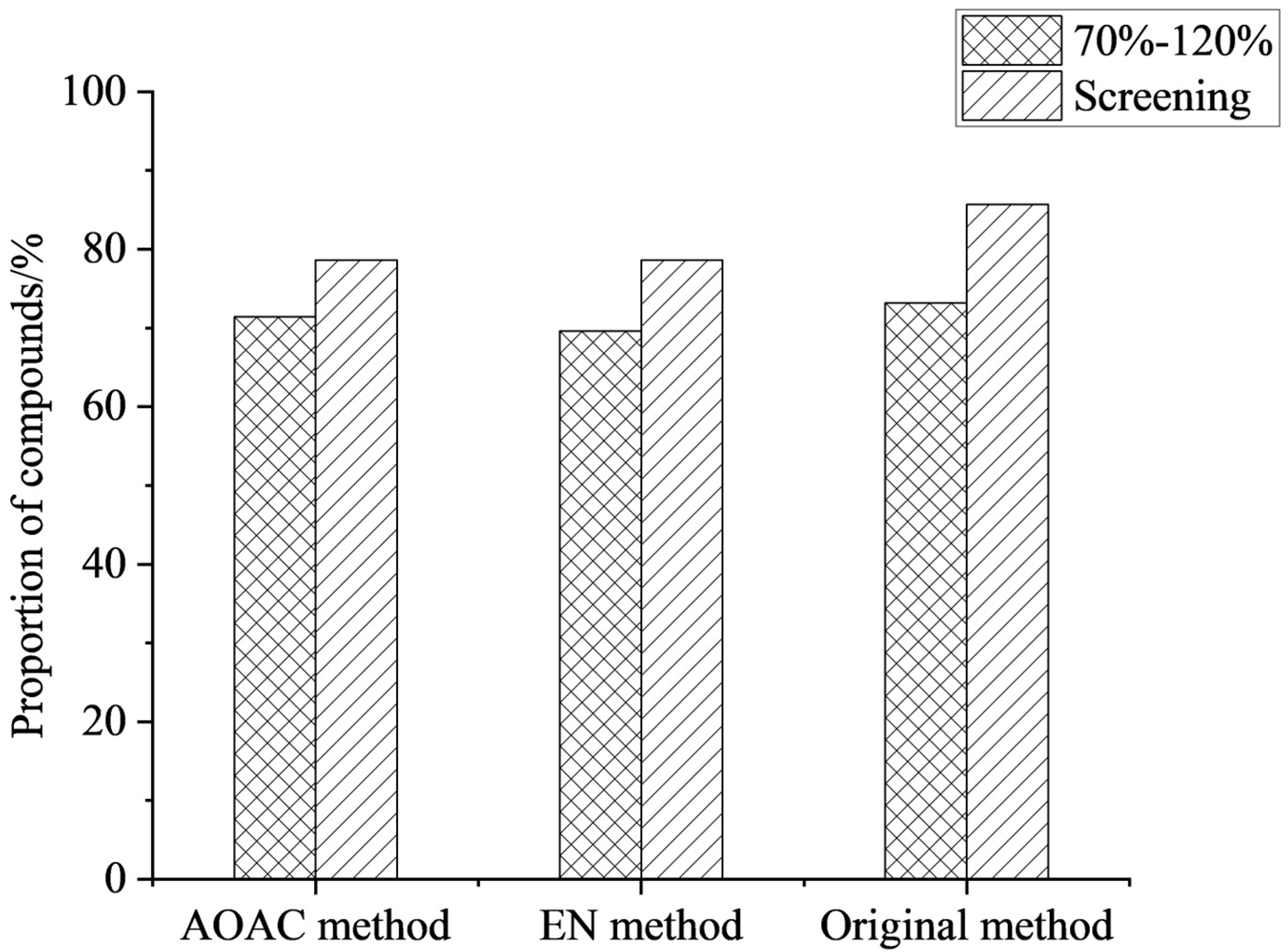

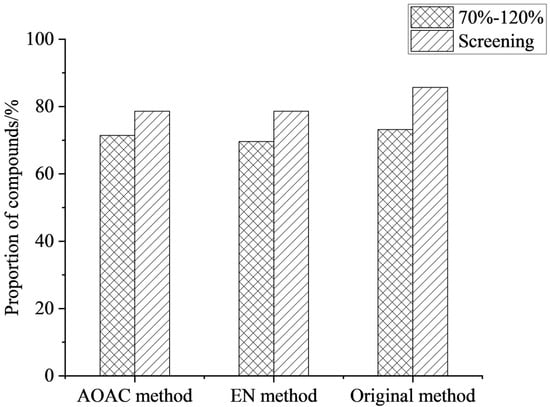

During extraction, the choice of salt is crucial for improving compound recovery. The core mechanism was to induce the separation of the miscible acetonitrile and aqueous phases by significantly increasing the ionic strength of the aqueous phase [30]. The addition of salt to the extraction solution substantially alters the distribution behavior of the compounds between the two phases, driving their transfer from the aqueous phase to the organic extraction phase, thereby achieving efficient extraction [31]. In this work, the extraction effects of the original method (4 g Na2SO4 + 1 g NaCl), EN (4 g Na2SO4 + 1 g NaCl + 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate + 1 g sodium citrate), and AOAC (6 g Na2SO4 + 1.5 g NaAc) were compared. The results showed that the three salting agents had little effect on the recoveries of the compounds, but the compound detection rate of the original method was 85.7%, slightly higher than that of the other two methods (see Figure 2). Therefore, the original method (4 g Na2SO4 + 1 g NaCl) was selected as the extraction salts for this work.

Figure 2.

Effect of different types of salts on the proportion of compounds (n = 3).

3.3. Optimization of the Adsorbent

For QuEChERS, the commonly used purification absorbents include PSA, C18, and MgSO4. PSA removed numerous impurities, such as organic acids, sugars, and pigments, and adsorbed compounds containing carboxyl groups. C18 exhibits hydrophobic properties and can be used to remove non-polar impurities; it effectively removes interfering substances such as fatty acids and fat-soluble pigments. MgSO4 removed water from the matrix to promote the separation of acetonitrile from the aqueous phase [32,33]. The presence of endogenous components, including abundant natural pigments, sugars, and organic acids in citrus fruits, can interfere with the detection of compounds. To improve quantitative accuracy and avoid instrument pollution, the three purification absorbents of MgSO4, PSA, and C18 were optimized in this work. The factors and levels were designed for MgSO4 (0 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg, 600 mg), PSA (0 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg), and C18 (0 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg) by an orthogonal experimental design table (L16(43)), with 16 runs and three experimental factors at four levels [34]. Experiments were conducted to determine each factor’s primary and secondary effects on recovery based on the proportion of compounds in each treatment group. The results were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the best purification absorbents. The results of the orthogonal test of purification absorbents are shown in Table 2, and the ANOVA results are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Purification results of the L16(43) sample’s orthogonal test.

Table 3.

Analysis of ANOVA experiment results.

According to the analysis of orthogonal experiment results, the higher R value indicated greater importance of the factor in the experiment. The results in Table 2 showed that the three factors were significant for the compounds, with A > C > B, and the K values were larger when factor A was at level 1, and factors B and C were both at level 3. Simultaneously, the ANOVA results in Table 3 indicated that factors A and C significantly affect the recoveries of the compounds (p < 0.05), while factor B has no significant effect (p > 0.05). However, as the amount of factor B increases, the ability to eliminate interference also increases. Conversely, excessive amounts could lead to reduced recoveries due to adsorption of the compounds. Therefore, in combination with the results of Table 2 and Table 3, this work ultimately selected 200 mg MgSO4 and 100 mg C18 as the purification filler.

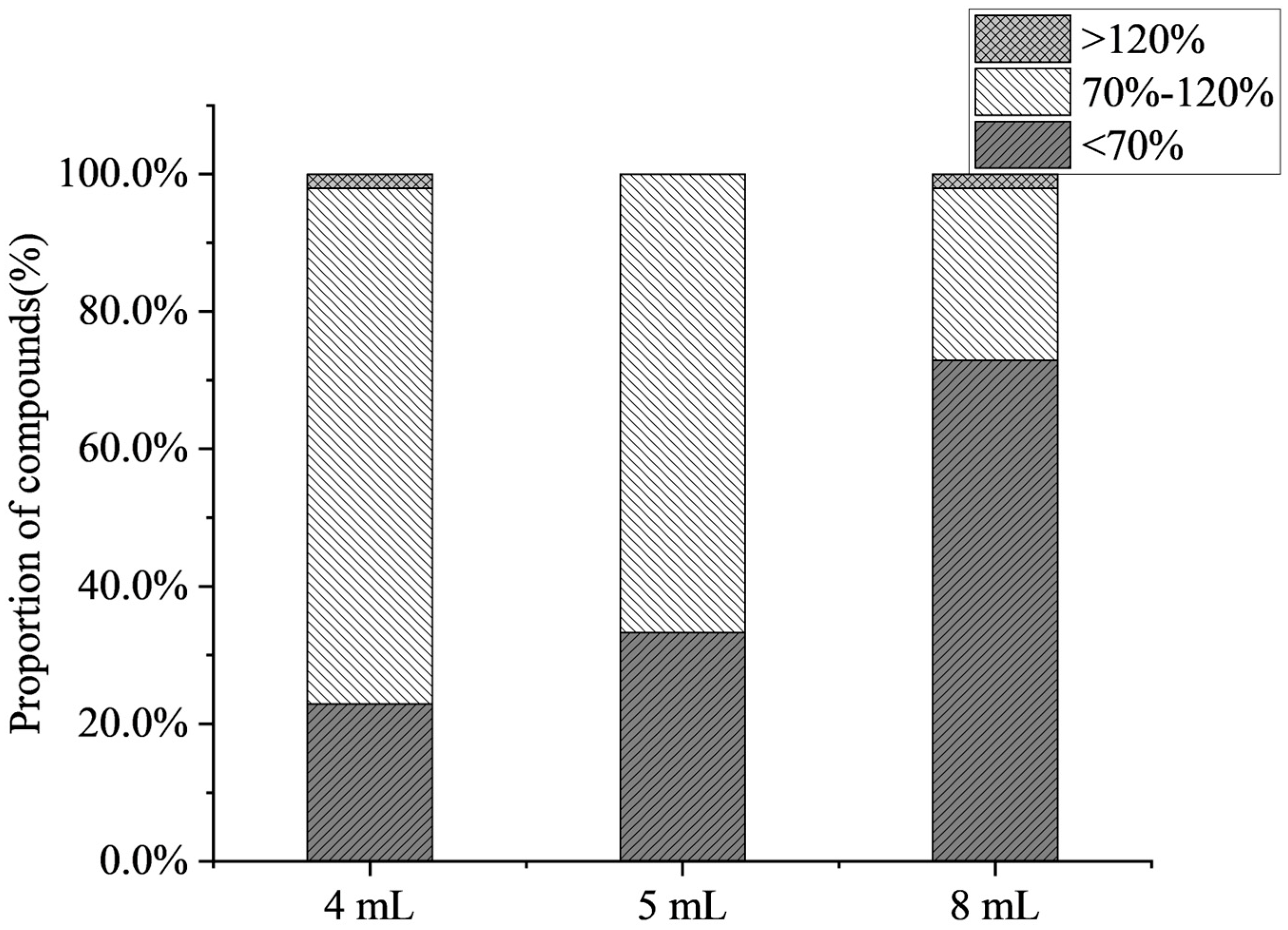

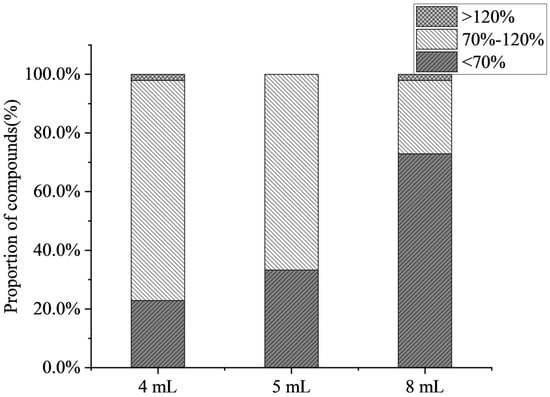

3.4. Optimization of the Volume of Evaporation

The effects of different volumes of evaporation (4 mL, 5 mL, 8 mL) on the recoveries of compounds were investigated in this work. Figure 3 shows that the average recovery decreased with an increase in the volume of evaporation, and some compounds (such as 6-benzylaminopurine and chlorphonium) exhibited a declining recovery trend. When the volume of evaporation was 8 mL, only 25% of the target compound recovery was accepted. The results indicate that as the volume of evaporation increased, the matrix effect increased, and antibiotics and PGRs were mostly inhibited in citrus fruits. At the volume of evaporation of 4 mL, the highest number of compounds was detected, achieving a detection rate of 91.1%. Therefore, the volume of evaporation of 4 mL was selected.

Figure 3.

Effect of the volume of evaporation on the proportion of compounds (n = 3).

3.5. Matrix Effect

Matrix effect (ME) occurs when interfering substances in the sample enter the ion source with the target compound, altering the compound’s ionization efficiency and thereby affecting the method’s accuracy and sensitivity [35]. The calculation formula of matrix effect was used: matrix effect (ME, %) = [(K1 − K2)/K2] × 100%, where K1 and K2 are the slopes of the matrix-matched standard curve and the slope of the solvent standard curve, respectively. The results showed that |ME| was lower than 20%, between 20% and 50%, or higher than 50%, indicating weak, medium, and strong matrix effects, respectively. Matrix effect is displayed in Table 4. Overall, the primary effects observed were weak matrix effects and medium matrix effects in the four citrus fruits, accounting for 74.6%, 66.7%, 63.5%, and 57.1% of the total, respectively. Except for Oleandomycin and Sulfadimethoxine, all antibiotics showed strong matrix effects, accounting for 80.0%; the PGRs mainly showed weak and medium matrix effects, with proportions of 84.9%, 75.5%, 71.7%, and 64.2% for the four citrus fruits, respectively.

Table 4.

Determination coefficients, the limits of detection (LODs), limits of quantification (LOQs), and matrix effect (ME) of 10 antibiotics and 53 PGRs in four citrus fruits.

3.6. Linear Range, LOD, and LOQ

The mixed standard working solution was added to the blank sample, the sample was extracted and purified according to 2.6, and a matrix-matched standard curve was established. LC-Q-Orbitrap/MS was used to detect the compounds. The results showed that the determination coefficients (R2) of the compounds in four citrus fruits were all greater than 0.99 (see Table 4). In addition to the compounds listed in Table 4, six compounds were not included due to poor R2 values in pomelo and lemon. The LODs in four citrus fruits were 1–50 µg/kg, with the LOQs being 2–80 µg/kg in mandarin and orange and 2–50 µg/kg in pomelo and lemon for 10 antibiotics. For 53 plant growth regulators, the LODs were 1–20 µg/kg in mandarin and pomelo and 2–50 µg/kg in orange and lemon, while the LOQs in four citrus fruits were 1–20 µg/kg, 1–50 µg/kg, 1–50 µg/kg, and 1–80 µg/kg, respectively. The proportions of the target compound with LOQ ≤ 5 µg/kg were 66.7%, 61.9%, 68.3%, and 63.5%, respectively.

3.7. Recovery and Precision

Results shown in Table 5 indicate that the recovery of all compounds in mandarin, orange, pomelo, and lemon was 61.4–119.9%, 62.6–119.9%, 61.4–119.8%, and 62.6–119.6%, respectively, and the relative standard deviations (RSDs) of the four citrus fruits were lower than 20%. For antibiotics, the recovery rates of four citrus fruits were 61.8–118.6%, 70.4–119.6%, 63.3–118.0%, and 71.2–116.5%, respectively. The recoveries of PGRs in four citrus fruits were 61.4–119.9%, 62.6–119.9%, 61.4–119.8%, and 62.6–119.6%, respectively. The result indicated that the method had good accuracy and precision and could accurately quantify all compounds in four citrus fruits simultaneously.

Table 5.

Results of average recoveries and the relative standard deviations (RSDs) of 10 antibiotics and 53 PGRs in four citrus fruits (n = 6).

3.8. Analysis of Real Samples

The established method was applied to 14 batches of mandarin, 10 batches of orange, 8 batches of pomelo, and 10 batches of lemon. The results (Table 6) revealed that nine compounds had an amount of 35 times, including 1 antibiotic amount of 12 times and 8 PGR amounts of 23 times. Antibiotic was detected in lemon, and the concentration range was 0.059–0.120 mg/kg. The PGRs were detected in three other citrus fruits; among them, there were five compounds in mandarin, six compounds in orange, and two compounds in pomelo, with the concentration ranges being 0.004–0.165 mg/kg, 0.002–0.084 mg/kg, and 0.006–0.852 mg/kg, respectively. Based on the National Food Safety Standard—Maximum residue limits of pesticides in food (GB 2763-2021), the result of the compounds did not exceed the limit value [36].

Table 6.

Detection of antibiotics and PGRs in four citrus fruits.

4. Conclusions

In citrus cultivation, the widespread use of antibiotics and PGRs has led to detectable residues of these compounds in citrus fruits due to the prevalence of infections. In order to achieve simultaneous detection of antibiotics and PGRs in citrus fruits, a method for the detection of 10 antibiotics and 53 plant growth regulators in citrus fruits by QuEChERS combined with LC-Q-Orbitrap/MS was established by optimizing the pretreatment conditions in this work. Overall, 63 compounds passed the validation with satisfactory recoveries and exhibited a good sensitivity in four citrus fruits through the validation of methodological parameters such as matrix effect, limit of determination, limit of quantitation, determination coefficients, and recovery. The results showed that the determination coefficients of all compounds were good (R2 ≥ 0.99), and the recoveries were between 60% and 120%. RSD was <20%. The LOQs in four citrus fruits were 2–80 µg/kg for 10 antibiotics and 1–80 µg/kg for PGRs. This method analyzed 42 batches of citrus fruits, and a total of one antibiotic and eight PGRs were detected. The result indicated that the method is characterized by rapidity, simplicity, and sensitivity. It not only rapidly screens antibiotics and PGRs in citrus fruits but also provides support for other citrus fruits.

Author Contributions

Y.X.: Writing—Original Draft, Validation, and Methodology; Z.L.: Resources, Validation, and Methodology; M.S.: Validation and Formal Analysis; X.W.: Validation and Methodology; K.T.: Data Curation and Validation; Q.C.: Data Curation and Methodology; C.F.: Funding Acquisition; H.C.: Writing—Review and Editing, Project Administration, Validation, and Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the science and technology project of the State Administration for Market Regulation (2023MK196).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albert, G.W.; Javier, T.; Victoria, I.; Antonio, L.; Estela, P.; Carles, B.; Concha, D.; Tadeo, F.R.; Jose, C.; Roberto, A.; et al. Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus. Nature 2018, 554, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.M.; Zhao, C.Y.; Shi, H.; Liao, Y.C.; Xu, F.; Du, H.J.; Xiao, H.; Zheng, J.K. Nutrients and bioactives in citrus fruits: Different citrus varieties, fruit parts, and growth stages. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 63, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, A.; Lourdes, C.; Stefania, B.; Marcelo, P.M.; Renato, B.B.; Leandro, P. Cultural management of Huanglongbing: Current status and ongoing research. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, F.; Chen, X.H.; Wang, C.; Zheng, Z.; Deng, X.L. Research advances on Citrus Huanglongbing-induced fruit symptomatology, quality deterioration, and underlying molecular Mechanisms. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2025, 52, 2046. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhao, P.Z.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Ye, J. Fighting citrus Huanglongbing with evolutionary principles. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 97, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.L.; Zheng, Y.Q.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, M.R. Current research on genomic analysis of Candidatus liberibacter spp. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2019, 40, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, Y.; Powell, C.A.; Doud, M.S.; Yang, C.; Duan, Y. Effective antibiotics against ‘Candidatus liberibacter asiaticus’ in HLB-Affected citrus plants identified via the graft-based evaluation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.S.; Zhou, Y.; Achor, D.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, N.; Zhou, C.Y. Inhibition effect of oxytetracycline on citrus Huanglongbing and its effect on citrus yield and quality. J. Plant Prot. 2020, 47, 1354. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.F.; Chen, S.; Yuan, H.Z. Research progress on screening methods for pesticide against Citrus Huanglongbing. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2025, 27, 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Batuman, O.; Britt-Ugartemendia, K.; Kunwar, S.; Yilmaz, S.; Fessler, L.; Redondo, A.; Chumachenko, K.; Chakravarty, S.; Wade, T. The use and impact of antibiotics in plant agriculture: A review. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesme, J.; Simonet, P. The soil resistome: A critical review on antibiotic resistance origins, ecology and dissemination potential in telluric bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 17, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T.; Yang, G.L.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, D.; Luo, T. Multidimensional Analysis of Antibiotic Residues in Plant-Derived Agricultural Products: Source Characteristics, Regulatory Standards, Risk Assessment, and Future Prospects. Food Sci. 2025, 27, 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo-Morales, C.E.; Lerma, T.A.; Martínez, J.M.; Palencia, M.; Combatt, E.M. Phytohormones and Plant Growth Regulators—A Review. J. Sci. Technol. Appl. 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.F.; Yin, X.X.; Liu, F.; Huang, B.; Wang, P. Research progress on the application of plant growth regulators in citrus production. Zhejiang Ganju 2023, 40, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, K.; Kumar, P.; Negi, S.; Sharma, R.; Joshi, A.K.; Suprun, I.I.; Al-Nakib, E.A. Physiological perspective of plant growth regulators in flowering, fruit setting and ripening process in citrus. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 309, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.O.; Yang, X. Preliminary report on the experiment of 0.1% brassinolide on fruit retention and yield increase of yongjia early fragrant pomelo. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2007, 13, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.M.; Du, M.W.; Jiang, F. Common Phytotoxicity Symptoms and Solutions of Plant Growth Regulators; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Z.X.; Song, S.F.; Gao, J.; Song, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yang, X.; Jiang, D.G.; Yang, D.J. Antibiotic residues in chicken meat in China: Occurrence and cumulative health risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 116, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.X.; Zhang, J.R.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, P.; Xia, W.; Wang, J.; Shen, X.S.; Kong, C. Utilization of wolfberry biomass waste-derived biochar as an efficient solid-phase extraction material for antibiotic detection in aquatic products. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, S.; Yaya, E.E.; Chandravanshi, B.S. Development and validation of HPLC-DAD method for the simultaneous determination of different classes of antibiotic residues in root, leafy and fruit-bearing vegetables preceded by effervescence-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid micro extraction (EA-DLLME). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 146, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, L.j.; Li, X.; Bao, R. Development of a simple UPLC-MS/MS method coupled with a modified QuEChERS for analyzing multiple antibiotics in vegetables and applied to pollution assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 129, 106135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.X.; Nie, F.; Gong, S.; Wang, Y.D.; Chen, D.; Wang, Z.J.; Li, P.; Wei, J.C. Panoramic contamination profiling and dietary exposure risk of plant growth regulators in medicinal and edible plants: A data modeling-driven MMSPE-UPLC-MS/MS platform. J. Hazard. Mater. 2026, 501, 140811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Huang, N.; Yuan, L.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, X.; Wan, Y.Q.; Liu, F. Simultaneous determination of plant growth regulators residues in citrus and unhusked rice by QuEChERS-UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Nanchang Univ. Nat. Sci. 2024, 48, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.M.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Z.L.; Shen, W.J.; Jiang, L.L.; Zhang, Y.Y. Determination of the 15 compounds include both pesticides and plant growth regulators (PGRs) in cherry by liquid chromatography triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS). Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Mao, S.H.; Zhou, Z.; Ruan, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F. Detection of 19 Plant Growth Regulators and Fungicides in Radix Ophiopogonis by Automatic QuEChERS Combined with UPLC-MS/MS. J. Instrum. Anal. 2025, 44, 318–325. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.T.; Liang, W.Y.; Yan, Z.Q.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhao, C.X.; Xu, G.W. Suspect and nontarget screening of pesticides and their transformation products in agricultural products using liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry. Talanta 2025, 283, 127154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaağaçlı, H.; Balkan, T.; Kızılarslan, M.; Kara, K. Pesticide residues in citrus fruits from Türkiye: Assessment of distribution, matrix effects, and health risks in lemon, mandarin, and orange. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 147, 108091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.L.; Huang, X.Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Qi, P.; Tan, J.P.; Huang, S.; Wang, C.L.; Liu, J. Simultaneous determination of prochloraz and its metabolitein cirtus via QuEChERS-UPLC-MS/MS. Agrochemicals 2022, 61, 820. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, X.P.; Liu, B.; Zhu, W.F.; Chen, J.B.; Ma, L.; Zhao, L.; Huang, L.Q.; Chen, X. Simultaneous Detection of Multiple Plant Growth Regulator Residues in Cabbage and Grape Using an Optimal QuEChERS Sample Preparation and UHPLC-MS/MS Method. J. AOAC Int. 2021, 105, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.; Silva, P.; Perestrelo, R.; Câmara, J.S. Residue Analysis of Insecticides in Potatoes by QuEChERS-dSPE/UHPLC-PDA. Foods 2020, 9, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.P.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.Z.; Wang, Z.W.; Xu, H.; Di, S.S.; Zhao, H.Y.; Wang, X.Q. Integrated QuEChERS strategy for high-throughput multi-pesticide residues analysis of vegetables. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1659, 462589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Li, J.X.; Wei, J.; Tong, K.X.; Xie, Y.J.; Chang, Q.Y.; Yu, X.X.; Li, B.; Lu, M.L.; Fan, C.L.; et al. Multi-residue analytical method development and dietary exposure risk assessment of 345 pesticides in mango by LC-Q-TOF/MS. Food Control 2025, 170, 111016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.Y.; Yu, F.Y.; Tian, Q.; Zou, Y.D.; Chen, Q.H.; Wang, H.D.; Guo, D.A.; et al. Integration of QuEChERS pretreatment and advanced liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis for the broad-spectrum screening and simultaneous quantification of 15 mycotoxins in Citrus reticulata peel. Food Chem. 2026, 502, 147597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Xie, Y.J.; Chang, Q.Y.; Bai, Y.T.; Tong, K.X.; Wu, X.Q.; Chen, H. Simultaneous determination of 202 pesticide residues and 19 mycotoxins in coix seed by QuEChERS coupled with LC-Q-TOF/MS and subsequent assessment of dietary exposure risk. Food Control 2025, 175, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M.; Gigliobianco, R.M.; Magnoni, F.; Censi, R.; Martino, P.D. Compensate for or minimize Matrix Effects? Strategies for overcoming Matrix Effects in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry technique: A tutorial review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 2763-2021; Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. 2021. Available online: http://www.chinapesticide.org.cn/zgnyxxw/zwb/detail/17901 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.