Abstract

This study investigated the effect of superheated steam (SS) assisted glycosylation modification on the flavor profile of oyster peptides (OP), and explored the correlation between key flavor compounds and glycosylation degree using Gas Chromatography–Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) and nano-scale Liquid Chromatography coupled with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (nano-LC/HRMS). The results indicated that SS treatment accelerated the glycosylation process, reduced free amino groups level, and distinguished their unique flavor through E-nose. GC-IMS analysis detected 64 signal peaks including 13 aldehydes, 6 ketones, 7 esters, 6 alcohols, 2 acids, 2 furans and 5 other substances. And it was revealed that SS-mediated glycosylation treatment reduced the levels of fishy odorants like Heptanal and Nonanal, while promoting the pleasant-smelling alcohols and esters. In addition, Pearson correlation showed a positive correlation between excessive glycation and the increase in aldehydes, which might cause the recurrence of undesirable fishy notes. Further nano-LC/HRMS analysis revealed that arginine and lysine acted as the main sites for glycosylation modification. Notably, glycosylated peptides such as KAFGHENEALVRK, DSRAATSPGELGVTIEGPKE, generated by mild SS treatment could convert into ketones and pyrazines in subsequent reactions, thereby contributing to overall sensory enhancement. In conclusion, SS treatment at 110 °C for 1 min significantly improved the flavor quality of OP and sustains improvement in subsequent stages, providing theoretical support for flavor optimization of oyster peptides.

1. Introduction

Oysters, specifically the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (Family: Ostreidae), are the most widely cultivated shellfish globally and are prevalent in China’s coastal regions. Known for their delicate meat and rich protein content, as well as their substantial vitamins and trace elements, oysters are often referred to as “Marine milk” [1]. In China, the most traditional methods of processing oysters include consuming fresh, drying into products, or using as seasonings, which generally results in a low overall utilization rate. Therefore, deep-processing oyster products have become a market focus. Enzymatic hydrolysis, which utilizes different types of proteases to break down protein raw materials, offers advantages such as mild conditions and ease of control [2,3], and has become one of the primary methods for producing oyster peptides (OP). Research has shown that OP derived from enzymatic hydrolysis exhibits antihypertensive, antioxidant, antitumor, antifatigue, and anticoagulant properties [4,5]. They can also promote sexual reproduction and improve the structure of intestinal flora [6].

However, oysters and their hydrolysates (OP) possess unpleasant fishy flavor substances such as short-chain aldehydes and unsaturated aldehydes [7], which limits the application fields of oysters and hinders their high-value utilization. To address this issue, researchers have developed methods for fishy flavor removal, which can be broadly divided into two categories. One approach removes the fishy flavor directly through adsorption by deodorants or encapsulation of volatile compounds. The other approach masks the fishy flavor by generating other aromatic substances, such as through the Maillard reaction, microbial fermentation, and spice marination [8]. The Maillard reaction is widely used to mask undesirable flavors and enhance food taste profiles. In the initial phase of this reaction, known as glycosylation, compounds including N-substituted glycosylamine and 1-amino-1-deoxy-2-ketose are produced. This stage involves the condensation of free amino groups found on protein side chains with the carbonyl groups present in reducing sugars [9]. These early products act as precursors to volatile flavors, continuously participating in the reaction and thereby affecting the food’s taste profile. Research conducted by Liu et al. [10] demonstrated that the level of glycosylation directly influenced the presence of volatile compounds, thereby enhancing the aromatic qualities of silver carp.

Superheated steam (SS), as an emerging and efficient thermal processing technology, demonstrates unique advantages in food processing. This technology involves heating saturated steam beyond its boiling point under pressurized conditions, utilizing combined heat transfer mechanisms such as convection, condensation, and radiation to achieve highly efficient processing [11]. Currently, SS has been widely applied in drying, sterilization, and quality improvement of fruits, vegetables, cereals, meat, and dairy products, showing remarkable effectiveness in reducing harmful substances and enhancing food quality [12]. Specifically, Wang et al. [13] demonstrated that compared to charcoal, infrared, and microwave heating, superheated steam treatment significantly inhibits lipid oxidation in fried beef patties, thereby reducing the formation of carcinogenic heterocyclic amines. Chindapan et al. [14] found that this technology enhances the flavor characteristics of Robusta coffee beans, expanding their commercial application prospects. Takemitsu et al. [15] also reported that superheated steam treatment can reduce off-flavor compounds such as aldehydes and acids in barley by approximately 50%, significantly improving its palatability.

The unique thermophysical properties of SS, such as its high thermal conductivity and continuous dry flow characteristics, demonstrate significant potential in driving the glycosylation process during the initial stage of the Maillard reaction. In promoting glycosylation, SS exerts synergistic effects through multiple mechanisms: its excellent thermal conductivity enables rapid and uniform heating of materials, providing sufficient activation energy for the condensation reaction between free amino groups in peptides and carbonyl groups in reducing sugars; meanwhile, the continuous dry flow effectively removes water molecules generated during the reaction, shifting the reaction equilibrium toward glycosylation products and thereby enhancing reaction rate [16]. According to Chen et al. [17] prolonged superheated steam treatment led to a significant increase in Maillard reaction products (MRP) within the β-lactoglobulin-glucose (βlg-Glu) system. Particularly in the flavor improvement of oyster peptides, this technology offers a dual advantage: generating desirable flavor compounds through glycosylation while simultaneously removing primary fishy odor components, achieving synergistic flavor enhancement [18,19]. Despite the considerable potential of superheated steam technology, systematic research on its application in glycosylation-mediated flavor modification of oyster peptides remains relatively limited.

To comprehensively elucidate the flavor transformation mechanism, advanced analytical techniques are required. On the one hand, the rapid and sensitive profiling of volatile organic compounds is crucial. Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) has emerged as a powerful tool for visualizing food flavors, renowned for its high sensitivity, rapid analysis, and ability to detect volatile fingerprints without complex pre-treatment [20]. On the other hand, a deep understanding at the molecular level necessitates the precise identification of modified peptide segments. Nano-scale Liquid Chromatography coupled with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (nano-LC/HRMS), as a cornerstone of modern food proteomics, offers unparalleled sensitivity and accuracy for characterizing low-abundance glycated peptides in complex systems [21,22]. The combination of these two techniques provides a holistic strategy, linking macroscopic flavor changes to microscopic molecular modifications.

Therefore, this study explored the molecular mechanism underlying the deodorization of glycosylated OP mediated by SS. The extent of glycosylation of glycosylated OP was assessed by measuring its free amino group content. An E-nose, GC-IMS in conjunction with principal component analysis (PCA), and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were used to assess the volatile components of the OP. The glycosylated peptide segments were also identified using nano-LC/HRMS, and the results provided deeper insights into how the glycosylation process influences the OP’s flavor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Fresh oysters were acquired from Rushan Breeding Base (Rushan, Shandong, China, October 2023). Neutrase (100,000 U/g) and Flavourzyme (30,000 U/g) were sourced from Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Analytical-grade glucose and o-phthaldialdehyde were also supplied by the same company. Chromatographic-grade formic acid and acetonitrile (98%) were sourced from Beijing Merck Drugs and Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. Preparation of OP

The experiment was conducted with slight modifications based on Zhang et al. [20]. After shelling and removing the meat from fresh oysters, the meat was weighed and distilled water was added in a 1:2 ratio depending on the bulk of the meat to the liquid. Blended the oysters in a tissue homogenizer for 5 min. Subsequently, the pH of the oyster homogenate was adjusted to 7.0 using 0.1 M NaOH. Then, a composite enzyme mixture (Neutrase–Flavourzyme = 1:1, m/m) was added at a dosage of 0.7% (m/m, relative to oyster meat mass) to initiate enzymatic hydrolysis. The mixture was hydrolyzed enzymatically for four hours in a water bath at 50 °C. After that, the enzyme was heated for ten minutes at 100 °C in a water bath to render it inactive. In a refrigerated centrifuge set at 4 °C, the sample was centrifuged for 20 min at 8000 rpm to produce the OP solution. After that, the supernatant was gathered and freeze-dried for subsequent use.

2.3. Preparation of the OP-Glucose System

The freeze-dried OP powder was dissolved in deionized water, followed by addition of glucose at a 1:1 (w/w) ratio. After complete dissolution by vortex mixing, the OP-glucose solution was divided into 7 equal aliquots and freeze-dried for subsequent experiments.

2.4. Glycosylation of the OP-Glucose System

The superheated steam generator (ZKMB-28GB17, Vatti, Zhongshan, Guangdong, China) was preheated to the set temperature. Then, 0.5 g of freeze-dried OP-glucose mixture samples was weighed, placed in 20 mL glass vials, and subjected to heat treatment in the superheated steam chamber. The treatment temperatures were 110 °C and 130 °C, with durations of 1, 3, and 5 min, respectively. To stop the glycosylation reaction, all samples were quenched for ten minutes in an ice-water bath. These samples, treated under different conditions, were named 110-1, 110-3, 110-5, 130-1, 130-3, and 130-5. Additionally, an untreated OP group was set up as a comparison, named TAI. The freeze-dried OP-glucose mixture that has not undergone any further heat treatment was named as CON.

2.5. Determination of the Free Amino Groups

With a small modification, the o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) method for determining free amino groups was carried out as Huang et al. [23] reported. Lysine was used at values ranging from 0 to 0.60 mg/mL to create a standard curve. Dissolved the glycosylated OP samples in ultrapure water and diluted to 1 mg/mL. After mixing a 100 μL aliquot of 1 mg/mL material with 2 mL of o-phthalaldehyde, the absorbance at 340 nm was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (U-2910, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The standard curve equation was then used to determine the sample’s free amino groups content.

2.6. Determination of Volatile Flavor Profile by E-Nose

The smell of OP was examined using the E-nose (PEN3, Airsense, Schwerin, Germany). Following a slightly adapted version of the method outlined by Liu et al. [24], 0.5 g of the glycosylated OP samples was weighed, transferred to a 20 mL sample vial, and securely sealed. The vials were incubated in a 60 °C water bath for 30 min, followed by equilibration at room temperature before the PEN3 probe was inserted for measurement. The measurement parameters were as follows: 400 mL/min of carrier gas flow rate, 90 s for cleaning, 10 s for zeroing, 5 s for preparation, and 100 s for measurement. The E-nose features ten metal oxide sensors, each designed to detect specific types of compounds: W1C (aromatics), W5S (nitrogen oxides), W3C (aromatic, ammonia), W6S (hydrogen), W5C (short-chain alkanes, aromatics), W1S (methyl compounds), W1W (inorganic sulfides), W2S (alcohols, aldehydes, ketones), W2W (aromatics, organic sulfides), and W3S (long-chain alkanes).

2.7. Determination of Volatile Compounds by HS-GC-IMS

HS-GC-IMS (Flavour Spec, G.A.S, Dortmund, Germany) was utilized to examine the volatile chemicals in the samples. The method was carried out based on the work of Nie et al. [25] with minor modifications. Separately, dissolved 0.5 g of each sample in 8 mL of deionized water, then aspirated 2 mL of the mixture into a 20 mL headspace container. A 500 μL aliquot was injected for examination following a 15 min incubation period at 60 °C. For gas chromatography (GC), separation was achieved on an Agilent DB-WAX capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) maintained at a constant temperature of 60 °C. High-purity nitrogen (≥99.999%) served as the carrier gas, with its flow rate programmed as follows: 2 mL/min for 2 min, increased to 10 mL/min over 10 min, then to 100 mL/min over 20 min, and finally to 150 mL/min for the last 10 min. For ion mobility spectrometry (IMS), the drift tube (9.8 cm) was operated at 45 °C with a uniform electric field of 400 V/cm. High-purity nitrogen (≥99.999%) was used as the drift gas at a constant flow rate of 150 mL/min. The NIST database and the GC-IMS library standards were applied to qualitatively analyze the volatile compounds.

2.8. Sensory Evaluation Test

The sensory evaluation test was adapted with modifications from the approach described by Zhao et al. [26]. A panel of ten trained sensory evaluators (5 male, 5 female, aged 23–28) was assembled. This study focused specifically on odor attributes. Through preliminary analysis and discussion, the panel identified five key attributes for evaluation: “fishy odor”, “seafood odor”, “burnt aroma”, “caramel odor”, and “meaty aroma”, along with overall acceptability. A 10-point scale (0–9) was used for assessment, where scores of 0–2 indicated extremely weak intensity/extreme dislike, 3–5 represented moderate intensity/moderate liking, and 6–9 denoted extremely strong intensity/strong liking. All evaluations were conducted in a standard sensory laboratory under controlled conditions—ensuring a well-ventilated, odor-free, and quiet environment. Between samples, evaluators observed a 10 min rest interval to minimize carryover effects.

2.9. Identification of Glycated Peptides by Nano-LC/HRMS

Adapted from Fu et al. [22], the nano-LC/HRMS method for identifying glycosylation sites was performed with minor adjustments. The glycated oyster peptide samples were desalted using a C18 cartridge. The peptides were then lyophilized, reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution, and analyzed using an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) coupled to an EASY-nano LC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A 5 μL sample was injected by the autosampler onto a loading column (Thermo Scientific EASY column, 100 μm × 2 cm, 5 μm, C18) and subsequently separated on an analytical column (Thermo Scientific EASY column, 75 μm × 10 cm, 3 μm, C18) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in 84% acetonitrile (B). A linear gradient was run from 0% to 35% B over 75 min, followed by an increase to 100% B over 7 min (75–82 min), and a final hold at 100% B for 3 min (82–85 min). The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent mode, automatically switching between full-scan MS and MS/MS acquisitions. The detection was performed in positive ion mode (ESI+) with a spray voltage of 2.2 kV. Full-scan MS spectra (m/z 350–1550) were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer at a resolution of 60,000, with an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 2 × 106 and a maximum injection time of 50 ms. The MS/MS spectra were obtained at a resolution of 15,000, with a normalized collision energy of 32 eV and an underfill ratio of 0.1%. The raw files were submitted to the Sequest server via Proteome Discoverer (version 1.4.1.14) for database searching using ETD/HCD fragmentation modes. The database used for the search was uniprot_Crassostrea_gigas_83441_20230518. For ETD spectra, the precursor ion tolerance was set to 20 ppm, and the fragment ion tolerance was set to 1.2 Da. For HCD spectra, the precursor ion tolerance was set to 20 ppm, and the fragment ion tolerance was set to 0.1 Da. The result filtering parameters were as follows: FDR < 0.01. Variable modifications included: Oxidation (K, M, P) and C6H10O5 (K, R).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Every experiment was carried out in triplicate, and the mean ± SD was used to express the results. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 17.0, and significant differences between groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. For GC-IMS analysis, the Reporter and Gallery Plot plug-ins were utilized to evaluate sample differences and generate fingerprints, while SIMCA 14.1 (MKS Umetrics AB Inc., Andover, MA, USA) was employed for multivariate statistical analysis of volatile compounds. The relationship between glycosylation degree and volatile compound content was assessed using Pearson correlation analysis in Origin Pro 2024 (Origin Lab Corp, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Free Amino Groups

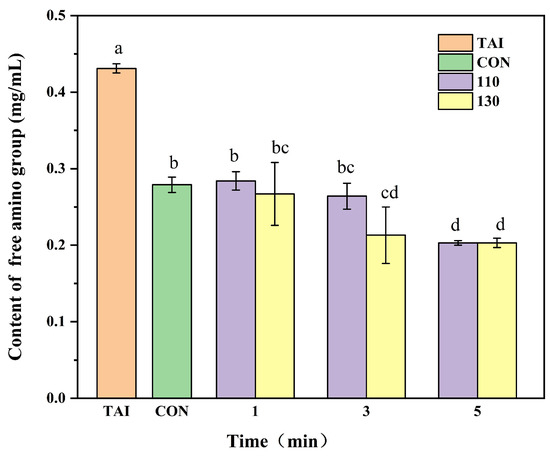

A decrease in free amino groups content, a measure of the degree of glycosylation, results from the gradual reaction of proteins’ free amino groups with sugar carbonyl groups during glycosylation [27]. When glucose was added, the free amino groups content significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in comparison to the TAI group, as seen in Figure 1. The significant loss of lysine residues suggested that alterations in protein conformation might have occurred. Given the crucial role of lysine in maintaining β-sheet structure [28], its modification could have been a potential contributing factor to the reduction in ordered secondary structures. With higher SS temperatures and extended processing times, the free amino groups content generally decreased, aligning with the results reported by Zhang et al. [29]. The high thermal conductivity of SS provides sufficient activation energy for the condensation reaction between free amino groups and reducing sugars, increases the collision rate between protein and sugar molecules, and consequently intensifies the degree of glycosylation [30]. Intriguingly, the 110-1 group’s free amino groups content did not alter much compared to the CON group, possibly due to the low temperature and short duration of the SS treatment, which failed to instantly remove the deeply embedded moisture in the samples. Consequently, reducing sugars could not replace the spatial positions of water molecules for further glycosylation modification [31]. As the reaction time extended, the free amino groups content in the 110-5 group and the 130-5 group became essentially the same. This convergence may result from conjugate breakdown, structural alterations, and glycosylation site saturation, which decreased OP’s ability to bind glucose and prevented further reductions in free amino content [32].

Figure 1.

Impact of glycosylation reaction on the free amino group content of OP. TAI: unprocessed OP; CON: OP with added sugar but no SS reaction; 110: the temperature of SS is 110 °C; 130: the temperature of SS is 130 °C. Different letters in the figure indicate statistically significant differences among groups (p < 0.05).

3.2. Analysis of E-Nose

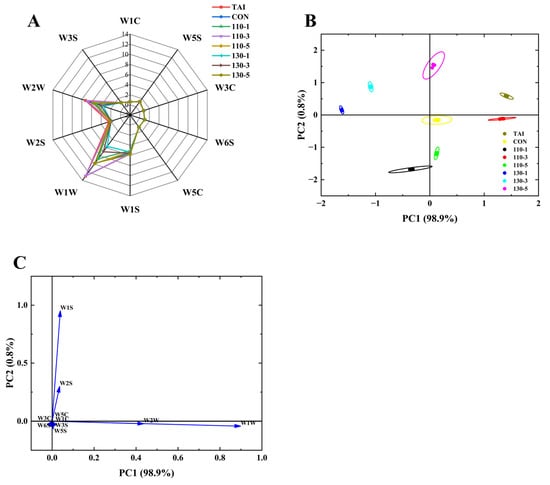

The E-nose, which simulates biological olfactory functions through metal oxide sensors, is a highly efficient and rapid instrument for detecting the volatile flavor profiles [24]. As depicted in Figure 2A, the response values of six sensors, W3S, W1C, W5S, W3C, W6S, and W5C, remained relatively low both before and after SS treatment, with negligible variations observed across the samples. This suggested that the contents of nitrogen oxides, ammonia compounds, hydrides, and short-chain alkanes did not change significantly during the sample processing. Among the eight sample groups, the sensors W2W, W2S, W1W, and W1S demonstrated high sensing capabilities and notable group differences, indicating that the primary flavor chemicals in the OP were sulfides, aromatic compounds, alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones. Moreover, the samples’ response metrics on the W1W and W2W sensors varied considerably, suggesting that these two sensors were able to differentiate between OP samples that had been exposed to SS at various temperatures and times.

Figure 2.

(A) Radar Chart; (B) PCA Plot; (C) Loading Plot of the E-nose. TAI: unprocessed OP; CON: OP with added sugar but no SS reaction; 110-1: SS temperature of 110 °C was treated for 1 min; 110-3: SS temperature of 110 °C was treated for 3 min; 110-5: SS temperature of 110 °C was treated for 5 min; 130-1: SS temperature of 130 °C was treated for 1 min; 130-3: SS temperature of 110 °C was treated for 3 min; 130-5: SS temperature of 130 °C was treated for 5 min.

In order to facilitate efficient sample separation, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a technique used to reduce the dimensionality of data from E-nose sensors, extract important distinctive variables, and emphasize those with the highest contribution rates [33]. PCA centers on the responses of different sensors of the E-nose and can characterize the flavor differences between different samples. The farther the distance between the sample distribution areas, the greater the flavor differences. According to Figure 2B, PC1 accounted for 98.9% of the variance, and PC2 accounted for 0.8%, resulting in a cumulative variance of 99.7%, well above the threshold of 85%. This demonstrates that the two principal components effectively captured the variations in sample flavor profiles. Within the principal component analysis area, the TAI group and the 110-3 group overlapped on the first principal component, while the 130-5, 110-5, and 110-1 groups also overlapped with the CON group on the first principal component. However, significant differences were noted in the second principal component among these groups. Overall, the distinct separation of sample positions across groups demonstrates that the E-nose effectively distinguishes the main component variations in OP under different SS treatments. To further evaluate sensor contributions, the loading plot (Figure 2C) was analyzed. Sensors farther from the origin showed greater contributions The findings revealed that sensors W1W and W2W contributed more significantly to PC1, whereas W1S and W2S showed a higher contribution rate to PC2. This indicated that sensors W1W, W2W, W1S, and W2S were important in determining the flavor of OP samples, which was in line with the radar chart’s findings.

3.3. Analysis of Volatile Compounds in OP Treated Under Various SS Conditions

3.3.1. Qualitative Analysis of Volatile Compounds in OP Treated Under Various SS Conditions

To better examine the variations in flavor characteristics of glycosylated OP induced by SS, GC-IMS was employed to separate the volatile compounds. The results (Table 1) revealed 64 signal peaks in all, encompassing monomers, dimers, and neutral compounds. These compounds comprise 13 aldehydes, 6 ketones, 7 esters, 6 alcohols, 2 acids, 2 furans, and 5 other substances, with the latter category including 3 unidentified compounds.

Table 1.

Volatile flavor compounds in different SS conditions of OP by GC-IMS.

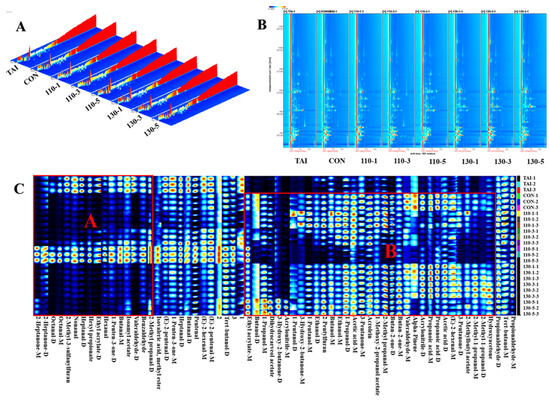

Three-dimensional spectra (Figure 3A) illustrate the distribution of volatile compounds and their relative abundance in the sample set, where ion migration time (ms), retention time (s), and ion peak intensities are plotted on the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively, in the three-dimensional spectra [34]. It was clear that there were significant variations in the locations and peak intensities of volatile chemicals in OP treated under various SS conditions, even if their distribution patterns were comparable. Figure 3B showed a two-dimensional spectrum obtained through dimensionality reduction techniques. The red vertical line at X-axis 1.0 represents the RIP (Reaction Ion Peak). The color intensity of the spots indicates the signal strength of certain volatile organic chemicals; darker colors indicate higher concentrations and stronger signals. Each point on either side of the RIP peak represents an identified volatile molecule [35]. The volatile compound compositions in samples treated with SS at different temperatures and durations formed points with varying positions and colors in the spectrum. The 130-5 and 110-5 groups exhibited significantly higher volatile compound abundance, likely resulting from enhanced glycosylation-driven flavor formation under prolonged SS exposure.

Figure 3.

(A) Three-dimensional spectra of volatile compounds; (B) GC-IMS two-dimensional spectra of volatile compounds; (C) fingerprint of volatile compounds in different SS conditions of OP. The differential volatile compounds in oyster peptides, induced by glycosylation, are manifested as distinct areas A and B in the fingerprint.

To correctly and graphically depict the differences in volatile flavor compounds between several sample groups, a fingerprint plot as shown in Figure 3C was constructed. In this plot, every row represented all volatile compounds in a sample group and every column represented the difference in content of the same compound among different sample groups, with darker colors indicating higher content. As shown in Figure 3C, the Propionaldehyde-M, Tert-butanol-M, Propionaldehyde-D, Tert-butanol-D, (E)-2-pentenal-M, (E)-2-hexenal-M, Pentenal, Butanal-D, Heptanal-D, 1-Penten-3-one-M, (E)-2-pentenal-D, Isovaleric acid, Methyl ester-M, were detected in all samples. These compounds possessed pungent, waxy, moldy, yeast-like, and intense oily flavor, collectively forming the basic aroma of the OP samples.

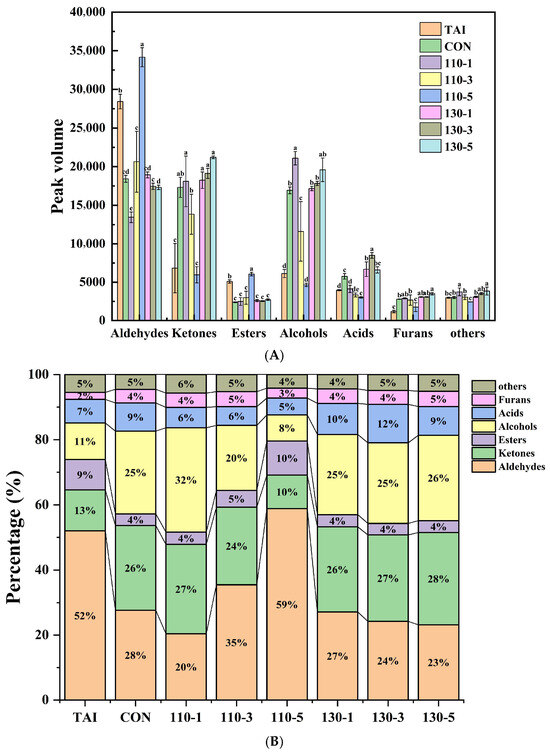

In Area A, the TAI group exhibited high levels of nine aldehydes, including 2-Methyl propanal-D, Benzaldehyde, Valeraldehyde-D, Butanal-M, Hexanal, Heptanal-D, Nonanal, Octanal-M, Octanal-D. Aldehydes, typically originating from lipid oxidation, significantly influenced aroma owing to their low detection thresholds [18]. Studies have shown that low molecular weight aldehydes such as Heptanal, Nonanal, and Octanal possess strong fishy and oily flavor, serving as the primary compounds contributing to a fishy flavor [36]. After SS treatment, the content of aldehydes in the samples decreased significantly, with the 110-1 group showing the lowest content (Figure 4). Interestingly, the aldehydes content increased with the extension of reaction time at 110 °C, while it decreased with the extension of reaction time at 130 °C. This was mainly because: at 110 °C, oyster peptides underwent peptide bond cleavage and amino acid pyrolysis, while promoting the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acid side chains, and more aldehydes were generated as the reaction time prolongs; at the higher temperature of 130 °C, the degradation of aldehydes was accelerated, and aldehydes reacted with free amino groups in the initial stage of Maillard reaction to form Schiff bases [10,37]. At this time, the degradation rate of aldehydes was greater than the generation rate, which resulted in a decrease in their content.

Figure 4.

(A) Peak volumes of volatile compounds in different OP samples; (B) the percentage of various volatile compounds in different OP samples. Different letters in the figure indicate statistically significant differences among groups (p < 0.05).

Area B represented volatile compounds produced after glycosylation treatment with SS. As the glycosylation reaction progresses with SS, more alcohols, ketones, acids, and furans were generated. In the glycosylation system, alcohols, ketones, and acids typically had higher flavor thresholds and did not significantly impact sensory properties [38]. Among these, the 110-1 group had the highest alcohols content. Alcohols, mainly resulting from lipid oxidation and decomposition, possess pleasant fruity and floral aromas [39,40]. Like aldehydes, ketones are linked to lipid oxidation and play a significant role as flavor precursors in reaction known as the Maillard system [41]. Both alcohols and ketones experienced different degrees of change during the glycosylation process, indicating their involvement in the glycosylation reaction and the generation of additional volatile compounds. Acids, often produced by the breakdown of long-chain fatty acids, contributed minimally to flavor due to their high thresholds and low concentrations. Furan, formed through carbohydrate dehydration, fatty acid oxidation, or the Amadori rearrangement mechanism, was predominantly detected in glycosylated samples. Notably, 2-Pentylfuran, with its low threshold, imparted a pleasant aroma characterized by sweetness and roasted notes [24]. Overall, the 110-1 group exhibited the best deodorizing effect, as it had the lowest aldehydes content and the highest alcohols content. The mild SS treatment (110-1 group) provided sufficient thermal energy to drive the initial glycosylation reaction while effectively preventing the reaction from progressing to advanced stages or triggering excessive degradation. This condition not only facilitated the participation of original fishy aldehydes in the reaction but also suppressed the generation of new aldehydes. In contrast, more intense or prolonged treatments were associated with an increase in the concentration of specific aldehydes. We hypothesize that these conditions may have disrupted the balance of initial reaction pathways, potentially promoting either the oxidative regeneration of carbonyls or progression into advanced Maillard stages that yield less desirable flavors. This indicates that mild SS-mediated glycation reactions are more effective in improving the undesirable flavor of OP.

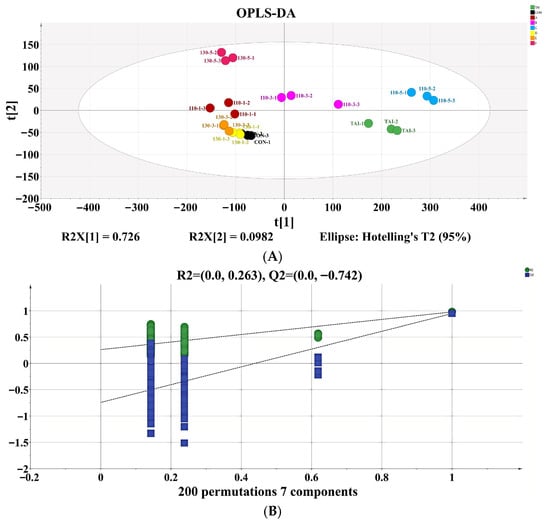

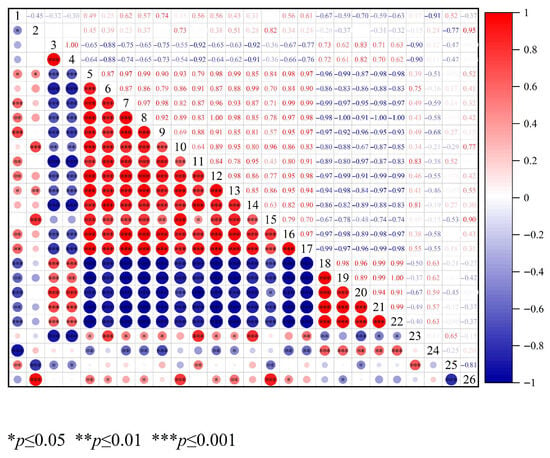

3.3.2. Multivariate Analysis of Volatile Compounds in OP Treated Under Various SS Conditions

Account on the volatile compound data collected by GC-IMS, we constructed an OPLS-DA model to comprehensively evaluate the flavor distinction in OP subjected to different SS treatments. The discriminant effect of the model was shown in Figure 5A, where the R2X, R2Y, Q2 value were 0.975, 0.865, and 0.652, respectively. These values demonstrated the model’s excellent reliability and its ability to predict the flavor of OP handled under various SS conditions. The 130-3 group, 130-1 group, and CON group were relatively close, suggesting that the volatile compounds in these three groups were similar. The other five groups were more dispersed, indicating major variations in the similarity of volatile compounds during the processing of OP with different SS treatments. Following 200 permutation tests, the model yielded R2 = 0.263 and Q2 = -0.742, with R2 exceeding Q2 and Q2 intersecting the negative y-axis (Figure 5B), confirming the absence of overfitting [42]. To better identify the key flavor driving the variances in OP treated with different SS situations, a VIP value plot was created. The higher the VIP value, the more that variable contributes to group distinction when using VIP > 1.0 as the criterion. Volatile substances with VIP > 1.0 were marked in red in Figure 5C. Using the thresholds of p < 0.05 and VIP > 1.0, 22 substances with significant contributions to OP samples were screened out. The differential contribution degrees, from largest to smallest, are 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone-D, Acetic acid-M, Ethanol-M, Pentenal, 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone-M, 1-Propanol-M, Propionaldehyde-M, Heptanal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-D, (E)-2-hexenal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-M, Ethanol-D, 2-Pentylfuran, 2-Methyl-1-propanol-D, Propanoic acid-M, Ethyl acrylate-D, 2-Methyl-1-propanol-M, Acrylonitrile-M, 1-Propanol-D, Octanal-M, Hydroxyacetone, and Butan-2-one-D. The results indicate that these volatile compounds could be used to distinguish OP samples treated under different SS conditions.

Figure 5.

(A) OPLS-DA; (B) model cross-validation diagram; (C) VIP score of OPLS-DA model. In Figure 5C, the shading in red color indicates the flavor compounds that have VIPs > 1.0, and the shading in green color indicates the flavor compounds that have VIPs < 1.0.

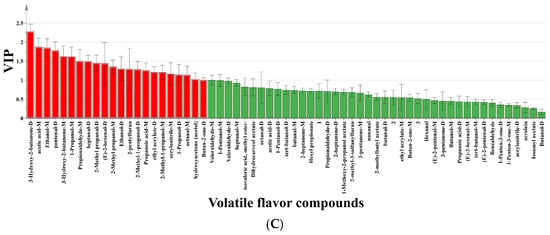

3.4. Analysis of Sensory Evaluation

The radar chart based on the sensory evaluation results was shown in Figure 6. The assessment covered six attributes: fishy odor, seafood odor, burnt aroma, caramel odor, meaty aroma, and overall acceptability. In terms of fishy odor, 110-1 and 130-1 groups received lower scores, indicating a milder fishy odor and better deodorization effect. For seafood odor, all groups treated with SS-assisted glycosylation showed reduced scores, with 130-5 group scoring the lowest. Regarding meaty aroma, the TAI group scored the lowest, followed by the CON group, which suggested that superheated steam-assisted glycosylation effectively enhanced the meaty aroma. As for burnt aroma and caramel odor, 130-5 group scored the highest, followed by 110-5 group, indicating that prolonged SS treatment led to excessive glycosylation in OP samples, thus intensifying the burnt aroma and caramel odor, which to some extent negatively affected the overall odor acceptability. Consequently, in terms of overall odor acceptability, 110-1 group was consistently rated as having the most desirable odor profile.

Figure 6.

Sensory evaluation results of oyster peptides treated with different superheated steam.

3.5. Analysis of Glycosylated Peptides

In order to unequivocally identify glycosylation sites, glycopeptides were subjected to Electron Transfer Dissociation (ETD) analysis, yielding high-quality tandem mass spectrometry data. As illustrated in the spectra provided in the Figures S1–S7, the ETD spectra typically exhibit strong signals and well-covered c- and z-ion series. This high-quality fragment information enabled reliable elucidation of the peptide sequences and, based on the mass differences between adjacent fragment ions, allowed for confident and precise localization of the glycosylation sites. For instance, in the case of the glycopeptide DVIDTNKDRTIDE identified in the CON group (Figure S1B), the mass difference between the adjacent c6 and c7 ions was determined to be 290.1449 Da. This observed mass shift significantly exceeds the theoretical residue mass of a lysine. Further calculation confirmed that this difference corresponded precisely to the sum of the lysine residue mass (128.09496 Da) and the glycan moiety mass (162.04994 Da), thereby confirming this site as a glycosylation site. Table 2 summarized the key data of the detected glycopeptides, including their peptide sequences, mass-to-charge ratios (m/z), charge, and mass deviations (ΔM). The mass deviations for all glycopeptides were within ±5 ppm, confirming the excellent agreement between our high-precision mass spectrometry measurements and the theoretical models. Overall, Lys (K) and Arg (R) are the main alteration sites, which is consistent with earlier findings suggesting that both of those amino acids may act as glycosylation sites in peptides produced from food [43]. Notably, the quantity of glycosylated peptides found rose in tandem with the temperature and length of the SS treatment, matching the level of glycosylation in the OP. Moreover, the three glycosylated peptides KAFGHENEALVRK, DVIDTNKDRTIDE and DSRAATSPGELGVTIEGPKE were mainly produced by slight glycosylation reactions, while GQRGIPGERGRDGDRGSNG, YISLEELYKIMTTK and SLYNKENKHVPLK were unique glycosylated peptides in group 130-5, suggesting that SS treatment might have exhibited selectivity for certain protein degradation pathways and saccharification reactions. This selectivity could have promoted the glycosylation reaction, possibly by exposing specific amino acid residues that are prone to modification. Furthermore, the glycosylated peptide DKDGKGKIPEEY was consistently present across different SS conditions, indicating that the specific amino acid (lysine) within this peptide might have possessed high reactivity. The flavor contribution was evaluated by the amino acid makeup and the protein of origin of the saccharide peptides [44]. Glycosylated peptides rich in lysine (K) and arginine (R) (such as DKDGKGKIPEEY and RRGESGPNGEPGRTGPPGPRGPRG) were efficient substrates for the Maillard reaction. The reaction rate between the ε-amino group of lysine or the guanidino group of arginine and the glycosyl group is generally fast in model systems, which might have facilitated the formation of Amadori rearrangement products (ARPs) under our experimental conditions. According to a common Maillard pathway [45], ARPs can undergo dehydration to form 3-deoxyglucosone (3-DG), which may further react to form furan rings. Subsequent oxidative modification of these furan rings, potentially involving interactions with amino groups and reactive oxygen species, provided a plausible route for the generation of the mild fruity aroma compounds that were detected. Furthermore, the detection of flavor substances with roasted and nutty aromas may be associated with another set of identified peptides, particularly those rich in hydrophobic amino acids (such as DSRAATSPGELGVTIEGPKE and SPFKVEVGPAKT). The theory that hydrophobic amino acid side chains could be oxidized by hydroxyl radicals to form alkoxyl radicals, followed by β-scission reactions resulting in C–C bond cleavage [46], provided a reasonable explanation for the formation of roasted-nutty compounds. Most of these glycosylated peptides were produced by slight glycosylation reactions. Flavor precursor proteins play a key role in altering flavor. The glycosylated peptides identified by different SS conditions were mainly released from the following proteins: EF-hand domain-containing protein, Sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein, Filamin-C, Collagen α-2(I) chain, Myosin heavy chain, and striated muscle. Zhang et al. [47] identified oyster umami peptides and found myosin as the main precursor protein of potential umami peptides. According to Hu et al. [48], myosin contained a significant amount of savory chemicals, while collagen from all fish samples primarily contained sweet amino acids and bitter peptides As a result, myosin and collagen might be good protein sources for producing a lot of taste-active peptides.

Table 2.

The glycated peptides from OP identified by nano-LC/HRMS.

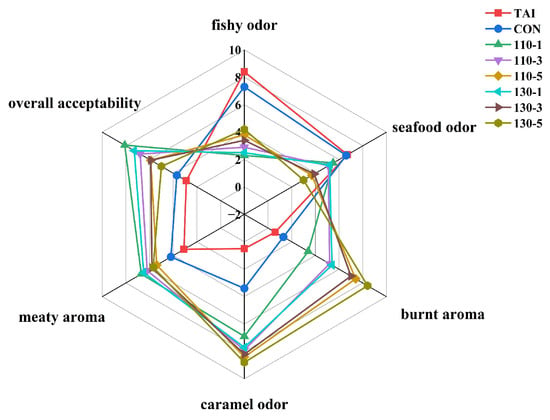

3.6. Analysis of the Correlation Between Important Volatile Compounds and Glycosylation Degree

To systematically evaluate the glycosylation process of OP, free amino groups content and the number of glycosylated peptides were adopted as key evaluation metrics. The number of glycosylated peptides not only comprehensively reflected the diversity of glycosylation modification sites but also effectively mitigated quantitative biases caused by differences in ionization efficiency among glycosylated segments in nano-LC/HRMS technology [49,50]. This provided a more robust systematic basis for assessing glycosylation levels. For flavor characterization, the response signals from two characteristic sensors in the electronic nose were integrated with 22 key volatile compounds (VIP > 1) screened by GC-IMS. A correlation model between glycation indicators and flavor characteristics was systematically constructed using Pearson correlation analysis. Figure 7 displayed the findings. The quantity of glycosylated peptides, Pentenal, Heptanal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-D, Octanal-M, and Hydroxyacetone were significantly correlated negatively with the free amino group content (r = −0.91 to −0.45, p < 0.05). Conversely, significant positive associations were observed with 1-Propanol-M, 1-Propanol-D, and Ethanol-M (r = 0.65 to 0.79, p < 0.05). This indicated that as the free amino group content decreases, the number of glycosylated peptides continuously increases, and the glycosylation degree of OP intensifies. Meanwhile, substances such as Pentenal, Heptanal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-D, Octanal-M, and Hydroxyacetone increase to varied degrees. This implied that the intensification of glycosylation tends to encourage lipid oxidation, leading to the production of more aldehyde compounds, which is line with the studies of Khan et al. [51]. Pentenal, Heptanal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-D, and Octanal-M showed a positive correlation with the response values of W1W and W2W sensors (sensitive to sulfides and aromatic compounds) in the electronic nose. This was mainly because amino acids in oyster peptides (such as cysteine, phenylalanine, leucine) served as common precursors for sulfides, aromatic compounds, and aldehydes [52]. Superheated steam glycosylation accelerated the catabolism of these amino acids, which led to a simultaneous increase in the production of the three types of substances, thereby resulting in a positive correlation between the sensor response values and aldehyde content. However, these substances showed a negative correlation with 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone-D, Acetic acid-M, Ethanol-M, 1-Propanol-M, Ethanol-D, 2-Pentyl furan, 2-Methyl-1-propanol-M and 1-Propanol-D (r = −0.99 ~ −0.46, p < 0.05). This indicated that alcohols and ketones participate in glycosylation reactions, leading to creating more ephemeral flavor molecules. Complex connections were shown between the degree of glycosylation and the concentration of important volatile chemicals. The mutual transformation among alcohols, ketones, acids, and aldehydes results in the production of a richer variety of volatile aromatic substances [10].

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis between glycosylation degree and key volatile compounds. 1 represents free amino groups content; 2 represents the number of glycosylated peptides; 3 represents the response values of W1W; 4 represents the response values of W2W; 5-26 represent the contents of 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone-D, Acetic acid-M, Ethanol-M, 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone-M, 1-Propanol-M, (E)-2-hexenal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-M, Ethanol-D, 2-Pentylfuran, Propanoic acid-M, 2-Methyl-1-propanol-M, Acrylonitrile-M, 1-Propanol-D, Pentenal, Heptanal-D, 2-Methyl propanal-D, Ethyl acrylate-D, Octanal-M, Butan-2-one-D, Hydroxyacetone, Propionaldehyde-M, and 2-Methyl-1-propanol-D.

4. Discussion

This study systematically investigated how SS conditions regulate the flavor profile of OP through glycosylation. The results demonstrated that SS treatment significantly accelerated the glycosylation rate of OP, as evidenced by a notable reduction in free amino group content. This structural modification was directly correlated with marked changes in volatile compounds. Specifically, the content of key fishy odorants such as heptanal, nonanal, and octanal was significantly reduced, effectively mitigating the characteristic marine off-flavor. Concurrently, SS-assisted glycosylation promoted the formation of various flavor-active compounds, including alcohols, ketones, acids, and esters, thereby enriching the overall aromatic complexity. However, correlation analysis and sensory evaluation results revealed a critical finding: excessive reaction intensity was associated with the accumulation of certain aldehydes, ultimately negatively affecting sensory quality, whereas moderate glycosylation (110-1) effectively enhanced flavor acceptability. This nonlinear relationship underscores the importance of optimizing SS parameters to achieve balanced flavor enhancement. To further elucidate the molecular basis of these changes, we identified 56 unique glycated peptides in different SS-treated samples using nano-LC/HRMS. These modified peptides, derived from various oyster protein precursors, provide direct molecular evidence of the glycosylation reaction. More importantly, as potential flavor carriers or precursors, their formation and distribution are fundamentally linked to the observed macroscopic flavor transformations. In conclusion, this work confirmed that controlled glycosylation mediated by superheated steam was an effective strategy for improving the flavor of oyster peptides. Our integrated analytical approach, combining volatile compound profiling with precise molecular modification data, not only provides a theoretical foundation for the practical application of OP but also establishes a robust methodological framework for the rational flavor design of peptide-based functional foods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/foods15020236/s1, Figure S1. (A–D) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the CON group. Figure S2. (A–E) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the 110-1 group. Figure S3. (A–J) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the 110-3 group. Figure S4. (A–F) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the 110-5 group. Figure S5. (A–G) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the 130-1 group. Figure S6. (A–J) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the 130-3 group. Figure S7. (A–N) Annotated MS/MS spectra of identified glycosylated peptides from the 130-5 group.

Author Contributions

L.-H.W.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. J.-W.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Data curation. Z.-C.T.: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision. X.-M.S.: Investigation, Supervision, Methodology. Y.-Y.H.: Formal analysis, Software. Z.-Z.H.: Validation, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science & Technology Project of the Education Department of Jiangxi Province (GJJ2200309), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20232BAB215059) and Graduate Student Innovation Found of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (YJS2024037).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Sensory evaluation was approved by the Experimental Ethics and Welfare Committee, College of Life Sciences, Jiangxi Normal University (Code: 20251114-001) on 7 November 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Z.R.; Su, G.W.; Zhou, F.B.; Lin, L.Z.; Liu, X.L.; Zhao, M.M. Alcalase-Hydrolyzed Oyster (Crassostrea rivularis) Meat Enhances Antioxidant and Aphrodisiac Activities in Normal Male Mice. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.L.; Yang, Y.F.; Wang, W.L.; Fan, Y.X.; Liu, Y. A Potential Flavor Seasoning from Aquaculture By-Products: An Example of Takifugu Obscurus. LWT 2021, 151, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Tao, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xie, J. Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Production, Biological Activities, Opportunities and Challenges. J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.Y.; Liao, W.W.; Kang, M.; Jia, Y.M.; Wang, Q.; Duan, S.; Xiao, S.Y.; Cao, Y.; Ji, H.W. Anti-Fatigue and Anti-Oxidant Activities of Oyster (Ostrea rivularis) Hydrolysate Prepared by Compound Protease. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 6577–6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.J.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Tian, C.C. Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Peptide Fraction from Oyster Soft Tissue by Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3947–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Z.; Yang, L.; Li, G.Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Cao, W.H.; Lin, H.S.; Chen, Z.Q.; Qin, X.M.; Huang, J.Z.; Zheng, H.N. Low-Molecular-Weight Oyster Peptides Ameliorate Cyclophosphamide-Chemotherapy Side-Effects in Lewis Lung Cancer Mice by Mitigating Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Immunosuppression. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 95, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.L.; Ren, Z.Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.C.; Weng, W.Y.; Shi, L.F. Selective Adsorption of Volatile Compounds of Oyster Peptides by V-Type Starch for Effective Deodorization. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.M.; Hong, H.; Luo, Y.K.; Li, B.; Tan, Y.Q. From Formation to Solutions: Off-Flavors and Innovative Removal Strategies for Farmed Freshwater Fish. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooshkam, M.; Varidi, M.; Bashash, M. The Maillard Reaction Products as Food-Born Antioxidant and Antibrowning Agents in Model and Real Food Systems. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Y.; Shen, S.Y.; Xiao, N.Y.; Jiang, Q.Q.; Shi, W.Z. Effect of Glycation on Physicochemical Properties and Volatile Flavor Characteristics of Silver Carp Mince. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, W.; Maggiolino, A.; Kour, J.; Arshad, M.S.; Aslam, N.; Afzal, M.F.; Meghwar, P.; Zafar, K.-W.; De Palo, P.; Korma, S.A. Dynamic Alterations in Protein, Sensory, Chemical, and Oxidative Properties Occurring in Meat during Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1057457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, F.; Yi, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, Y. Superheated Steam Technology: Recent Developments and Applications in Food Industries. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, S. Reduction of the Heterocyclic Amines in Grilled Beef Patties through the Combination of Thermal Food Processing Techniques without Destroying the Grilling Quality Characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindapan, N.; Puangngoen, C.; Devahastin, S. Profiles of Volatile Compounds and Sensory Characteristics of Robusta Coffee Beans Roasted by Hot Air and Superheated Steam. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3814–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemitsu, H.; Amako, M.; Sako, Y.; Kita, K.; Ozeki, T.; Inui, H.; Kitamura, S. Reducing the Undesirable Odor of Barley by Cooking with Superheated Steam. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 4732–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, P.-W.; Tu, Z.-C.; Hu, Y.-M.; Wang, H. Effects of Superheated Steam Treatment on the Allergenicity and Structure of Chicken Egg Ovomucoid. Foods 2022, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shao, Y.; Tu, Z.; Liu, J. Effect of Superheated Steam on Maillard Reaction Products, Digestibility, and Antioxidant Activity in β-Lactoglobulin-Glucose System. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 287, 138514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Hwang, K.E.; Jeong, T.J.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeon, K.H.; Kim, E.M.; Sung, J.M.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, C.J. Comparative Study on the Effects of Boiling, Steaming, Grilling, Microwaving and Superheated Steaming on Quality Characteristics of Marinated Chicken Steak. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2016, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutikno, L.A.; Bashir, K.M.I.; Kim, H.; Park, Y.; Won, N.E.; An, J.H.; Jeon, J.-H.; Yoon, S.-J.; Park, S.-M.; Sohn, J.H.; et al. Improvement in Physicochemical, Microbial, and Sensory Properties of Common Squid (Todarodes pacificus Steenstrup) by Superheated Steam Roasting in Combination with Smoking Treatment. J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019, 8721725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Tu, Z.C.; Hu, Z.Z.; Hu, Y.M.; Wang, H. Efficient Preparation of Oyster Hydrolysate with Aroma and Umami Coexistence Derived from Ultrasonic Pretreatment Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C. Critical Review of New Advances in Food and Plant Proteomics Analyses by Nano-LC/MS towards Advanced Foodomics. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 176, 117759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.F.; Xu, X.B.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.Z.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Du, M. Identification and Characterisation of Taste-Enhancing Peptides from Oysters (Crassostrea gigas) via the Maillard Reaction. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q.; Tu, Z.C.; Xiao, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.M.; Zhang, Q.T.; Niu, P.P. Characteristics and Antioxidant Activities of Ovalbumin Glycated with Different Saccharides under Heat Moisture Treatment. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Al-Dalali, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, J.H.; He, Z.G. Effect of Different Processing Steps in the Production of Beer Fish on Volatile Flavor Profile and Their Precursors Determined by HS-GC-IMS, HPLC, E-Nose, and E-Tongue. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, S.; Zhang, L.; Xie, Y.; Feng, S.; Yu, Y.; Tan, C.; Tu, Z. Effects of Different Thermal Processing Methods on Physicochemical Properties, Microstructure, Nutritional Quality and Volatile Flavor Compounds of Silver Carp Bone Soup. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Liu, C.; Qiu, S.; Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Hou, C.; Huang, R.; Li, J. Flavor Profile Evaluation of Soaked Greengage Wine with Different Base Liquor Treatments Using Principal Component Analysis and Heatmap Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.L.; Sun, W.Y.; Zhan, S.N.; Jia, R.; Lou, Q.M.; Huang, T. Glycosylation with Different Saccharides on the Gelling, Rheological and Structural Properties of Fish Gelatin. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kang, X.; Zhou, X.; Tong, L.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Lou, Q.; Huang, T. Glycosylation Fish Gelatin with Gum Arabic: Functional and Structural Properties. LWT 2021, 139, 110634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Tu, W.; Shen, Y.; Wang, H.B.; Yang, J.Y.; Ma, M.; Man, C.X.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Jiang, Y.J. Changes in Whey Protein Produced by Different Sterilization Processes and Lactose Content: Effects on Glycosylation Degree and Whey Protein Structure. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Zhou, Y.R.; Zhang, S.Q.; Xie, Z.H.; Wen, P.W.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.M.; Wu, P.H.; Liu, J.J.; Jiang, Q.N.; et al. Effects of Different High-Temperature Conduction Modes on the Ovalbumin-Glucose Model: AGEs Production and Regulation of Glycated Ovalbumin on Gut Microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Ye, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sha, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, T.; Hu, Y.; Tu, Z. The Mechanism of Decreased IgG/IgE-Binding of Ovalbumin by Preheating Treatment Combined with Glycation Identified by Liquid Chromatography and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10693–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Jia, H.; Mráz, J.; Zhao, R.; Li, S.J.; Dong, X.P.; Pan, J.F. Modified Structural and Functional Properties of Fish Gelatin by Glycosylation with Galacto-Oligosaccharides. Foods 2023, 12, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melucci, D.; Bendini, A.; Tesini, F.; Barbieri, S.; Zappi, A.; Vichi, S.; Conte, L.; Gallina Toschi, T. Rapid Direct Analysis to Discriminate Geographic Origin of Extra Virgin Olive Oils by Flash Gas Chromatography Electronic Nose and Chemometrics. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.H.; Tu, Z.C.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.M.; Wen, P.W.; Huang, X.L.; Wang, S. Discrimination and Characterization of Different Ultrafine Grinding Times on the Flavor Characteristic of Fish Gelatin Using E-Nose, HS-SPME-GC-MS and HS-GC-IMS. Food Chem. 2024, 433, 137299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, A.R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Ferreiro, M.; Setyaningsih, W.; Rohman, A.; Riyanto, S.; Palma, M. Development of a Methodology Based on Headspace-Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry for the Rapid Detection and Determination of Patin Fish Oil Adulterated with Palm Oil. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 7524–7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.X.; Chong, Y.Q.; Ding, Y.T.; Gu, S.Q.; Liu, L. Determination of the Effects of Different Washing Processes on Aroma Characteristics in Silver Carp Mince by MMSE–GC–MS, e-Nose and Sensory Evaluation. Food Chem. 2016, 207, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Nasiru, M.M.; Zhuang, H.; Zhou, G.H.; Zhang, J.H. Effects of Partial NaCl Substitution with High-Temperature Ripening on Proteolysis and Volatile Compounds during Process of Chinese Dry-Cured Lamb Ham. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wang, X.C.; Liu, Y. Physicochemical and Sensory Variables of Maillard Reaction Products Obtained from Takifugu Obscurus Muscle Hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2019, 290, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dalali, S.; Li, C.; Xu, B.C. Effect of Frozen Storage on the Lipid Oxidation, Protein Oxidation, and Flavor Profile of Marinated Raw Beef Meat. Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cai, Y.; Cao, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, P.; Gu, Q. Comparison of Different Species of Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Aroma Profile of Whole Mandarin (Citrus Reticulata Blanco Cv. Unshiu) Juice. J. Future Foods 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.N.; Yang, Q.F.; Hong, H.; Feng, L.G.; Liu, J.; Luo, Y.K. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Maillard Reaction Products Derived from Cod (Gadus morhua L.) Skin Collagen Peptides and Xylose. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.T.; Xie, J.L.; Yuan, H.B.; Wang, L.L.; Liu, F.Q.; Deng, Y.L.; Jiang, Y.W.; Yang, Y.Q. Characterization of Volatile Metabolites in Pu-Erh Teas with Different Storage Years by Combining GC-E-Nose, GC–MS, and GC-IMS. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.; Beilin, L. Advanced Glycation End-Products: A Review. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, G.; Zheng, L.; Cui, C.; Yang, B.; Ren, J.; Zhao, M. Characterization of Antioxidant Activity and Volatile Compounds of Maillard Reaction Products Derived from Different Peptide Fractions of Peanut Hydrolysate. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3250–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shen, M.; Lu, J.; Yang, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Fan, H.; Xie, J.; Xie, M. Maillard Reaction Harmful Products in Dairy Products: Formation, Occurrence, Analysis, and Mitigation Strategies. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Arntfield, S.D. Probing the Molecular Forces Involved in Binding of Selected Volatile Flavour Compounds to Salt-Extracted Pea Proteins. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Tu, Z.C.; Wen, P.W.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.M. Peptidomics Screening and Molecular Docking with Umami Receptors T1R1/T1R3 of Novel Umami Peptides from Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) Hydrolysates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xiao, N.Y.; Ye, Y.T.; Shi, W.Z. Fish Proteins as Potential Precursors of Taste-active Compounds: An in Silico Study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 6404–6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helm, S.; Baginsky, S. MSE for Label-Free Absolute Protein Quantification in Complex Proteomes. In Plant Membrane Proteomics; Mock, H.-P., Matros, A., Witzel, K., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1696, pp. 235–247. ISBN 978-1-4939-7409-2. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.C.; Gorenstein, M.V.; Li, G.-Z.; Vissers, J.P.C.; Geromanos, S.J. Absolute Quantification of Proteins by LCMSE. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2006, 5, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Jo, C.; Tariq, M.R. Meat Flavor Precursors and Factors Influencing Flavor Precursors—A Systematic Review. Meat Sci. 2015, 110, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Lv, M.; Pan, C.; Lo, X.; Ya, S.; Yu, E.; Ma, H. Analysis of the Mechanism of Difference in Umami Peptides from Oysters (Crassostrea ariakensis) Prepared by Trypsin Hydrolysis and Boiling through Hydrogen Bond Interactions. Food Chem. 2025, 476, 143367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.