Abstract

Hawthorn is widely distributed across China, including Shanxi, Henan, Hebei, Shandong, and Shaanxi provinces. It is rich in functional components and nutritional elements, making it a crucial raw material for medicinal and food products. This review provides comprehensive information of the distribution of hawthorn germplasm resources in China and compares the differences in nutrient composition, chemical substances, and functional activities among different species. Furthermore, it offers a statistical analysis of the diversified processing and applications of hawthorn in China. Finally, the review identifies current challenges in the agro-food industries and states the future outlook of the industry. By systematically integrating research findings into a comprehensive “resource–characterization–application” framework, the study addresses the current fragmentation and lack of systematic organization in hawthorn research. It seeks to provide a scientific basis for directional breeding, strategic planning of production areas, precise product development, and high-quality development of the hawthorn industry in years to come.

1. Introduction

Hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge) has cultivated approximately 1000 varieties worldwide, primarily distributed across the Northern Hemisphere. Among these, China stands as a significant region with a long history of hawthorn cultivation. China possesses relatively abundant hawthorn resources. A survey of hawthorn resources proposed the classification and grouping of hawthorn species, identifying twenty-three species and six varieties [1]. Its cultivation area spans the entire country. The botanical characteristics among different hawthorn varieties vary, primarily influenced by the combination of atmospheric variables and human factors.

It is well known for its distinctive flavor, major nutrients, and bioactive compounds. In addition to standard macronutrients and minerals, hawthorn is rich in vitamin C, flavonoids, organic acids, and polyphenols. The advancement of food processing technologies has further popularized hawthorn as a widely consumed food product. Nationally developed hawthorn products include popular snacks like candied haws, cakes, canned goods, wine, vinegar, and slices, as well as healthy foods. The 2020 edition of the Pharmacopeia of the People’s Republic of China (Part 1) outlines the hawthorn fruit’s functions, which include aiding digestion, strengthening the stomach, promoting blood circulation, and reducing blood pressure and lipids. It is also beneficial for indigestion, diarrhea, abdominal pain, amenorrhea, postpartum complications, specific pains, and hyperlipidemia conditions.

Nowadays, significant progress has been made in research works on hawthorn in various fields, such as botany, chemistry, pharmacology, clinical medicine, food, and cultivation. Hawthorn boasts an abundant variety of resources. The search conducted in major databases, i.e., CNKI, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using “hawthorn” as the subject or keyword revealed that the main cultivated hawthorns in China include hawthorn, North hawthorn (North Crataegus, Bei shanzha), South hawthorn (South Crataegus, Nan Shanzha), large-fruited hawthorn, and Guang hawthorn (Guang shanzha, also called Cantonese Crataegus) [2]. However, a detailed analysis of the search results reveals that the current reviews on hawthorn tend to focus on relatively limited topics, such as hawthorn’s botanical taxonomy, processing techniques, and extraction of bioactive compounds. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the Chinese hawthorn value chain by synthesizing information on germplasm resources, bioactive compounds and efficacy, processing applications, and other aspects, enabling readers to access information more efficiently.

2. Classification and Evolution of Hawthorn

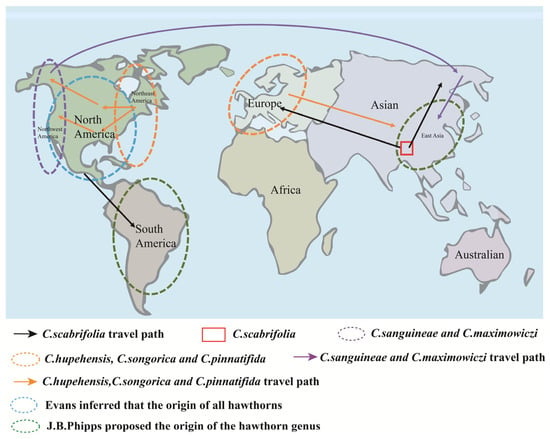

Hawthorn (C. pinnatifida Bunge) belongs to the genus Crataegus within the subfamily Maloideae of the Rosaceae family. It is widely distributed across Asia, Europe, and the Americas, between latitudes 20° N and 60° N [3]. There is considerable disagreement among scholars regarding the global classification, distribution, and total number of the Crataegus species, with estimates ranging from 150 to 1200 (Figure 1). However, most Chinese plant taxonomists concur that the genus comprises approximately 1000 species.

Figure 1.

Worldwide distribution of hawthorn cultivation.

Chinese hawthorn refers to several species, in addition to Crataegus pinnatifida (Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge var. major N. E. Brown; Crataegus pinnatifida Bge.), called North Crataegus (Bei Shanzha) and included in the pharmacopeia of the People’s Republic of China, South Crataegus (Nan shanzha) and Cantonese Crataegus (Guang shanzha) are commonly used in the Chinese market. In fact, there are two types of large-fruited hawthorn with the same name in China. One type of large-fruited hawthorn refers to a variety of plants in the Sect. Pinnatifidae of the Crataegus genus in the Maloideae subfamily of the Rosaceae family. This species is distinguished from the original by its larger fruit, which ripens to a red color.

Another type of large-fruited hawthorn is the Malus doumeri plant in the Sect. Pinnatifidae of the Malus Mill. genus in the Maloideae subfamily of the Rosaceae family, also known as Cantonese Crataegus (Guang shanzha). The mature fruit is green or greenish yellow. In China, hawthorn is primarily cultivated in Shandong, Shanxi, Henan, Hebei, Shan’xi, and Liaoning provinces for economic purposes mainly. In addition, Cantonese Crataegus fruit is large and shares similar pharmacological properties with the Chinese medicinal herb hawthorn, so it is often called “large-fruited hawthorn”. Cantonese Crataegus (Guang shanzha), including two closely related species from Malus doumeri (Bois) Chev. (locally called Taiwan crabapple) and Malus leiocalyca S.Z. Huang [4], are mainly distributed in the southwest of Guizhou, western and southwest of Jiangxi, southwest of Zhejiang, eastern and southeast of Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, and southeast of Yunnan in China and Taiwan. To attain a better understanding of Chinese hawthorn germplasm, resources are shown in Figure 2.

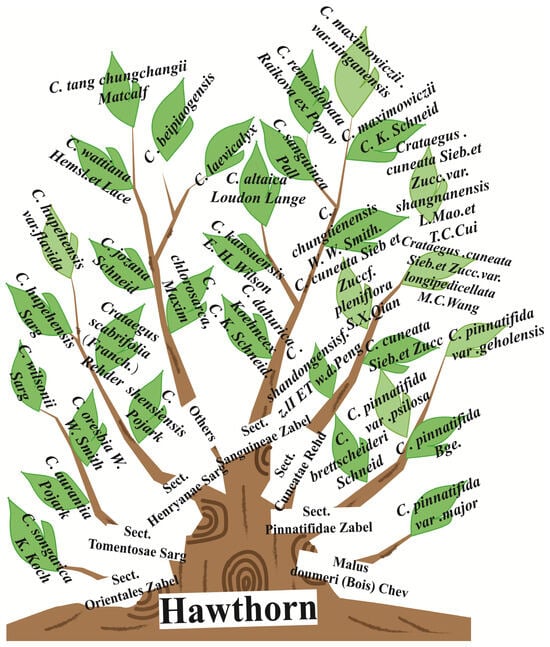

Figure 2.

The classification of Chinese hawthorn germplasm resources.

3. Distribution, Cultivation, and Characteristics of Hawthorn

Crataegus plant resources are relatively rich with widespread cultivation across China. Based on their natural geographical distribution, these plants can be classified into three groups, i.e., widespread, medium-range, and narrow-range species. Table 1 summarizes the survey of Chinese Crataegus resources and the classification systems proposed by Chinese scholars. As shown in Table 1, hawthorn resources are widely distributed and diverse. Currently, the primary hawthorn species used for medicinal purposes include the Northern hawthorn, which is approved for the use of food and medicine, as well as Southern hawthorn varieties. The southern varieties, namely the wild hawthorn (C. cuneata Sieb. et Zucc.) and the Cantonese Crataegus (Guang shanzha), are common in the regional market [5].

Table 1.

Classification and growth characteristics of Chinese Crataegus plants.

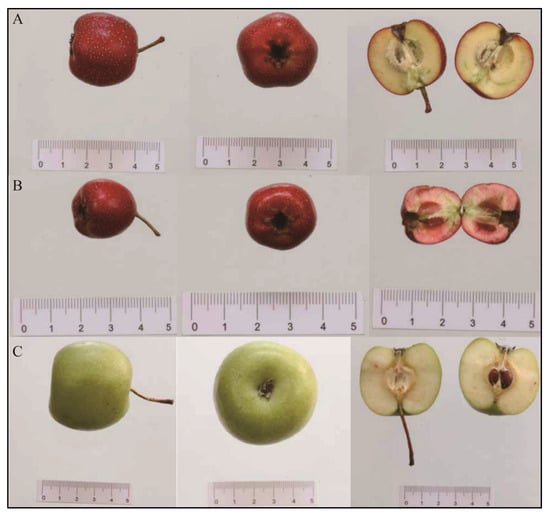

Table 2 compares the traits of North Crataegus (Bei Shanzha), South Crataegus (Nan shanzha), and Cantonese Crataegus (Guang shanzha) cultivars, using carpel and seed characteristics as key identification criteria. Figure 3 shows the fruit shapes and cross-sections of different hawthorn types. The comparative analysis reveals the following orders, such as Southern < Northern < Cantonese for fruit size and flesh thickness, Northern < Southern < Cantonese for outer skin color, Northern < Cantonese < Southern for flesh color, and Northern < Southern < Cantonese for seed number.

Table 2.

Morphological differences in typical hawthorn varieties across regions.

Figure 3.

Comparative morphological analysis of different typical regional hawthorn varieties, i.e., North Crataegus (A), South Crataegus (B), and Cantonese Crataegus (C) [6].

4. Active Chemical Substances and Functional Effects

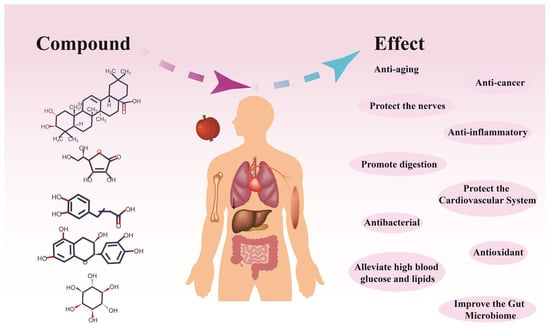

Hawthorn is rich in biologically active substances, such as sugar, flavonoids, phenols, terpenes, pectin, organic acids, etc. It is especially rich in pectin, which reaches 6.4%, and is ranked as the top of fruits; pectin exists in fruit tissues in different forms of protopectin, pectin, and pectinic acid [7]. Hawthorn has been used in traditional medicine since the ancient era. While its pharmacological effects were once unclear, they are now being elucidated through advances in research techniques (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hawthorn exhibits a range of pharmacological effects.

4.1. Basic Nutrients

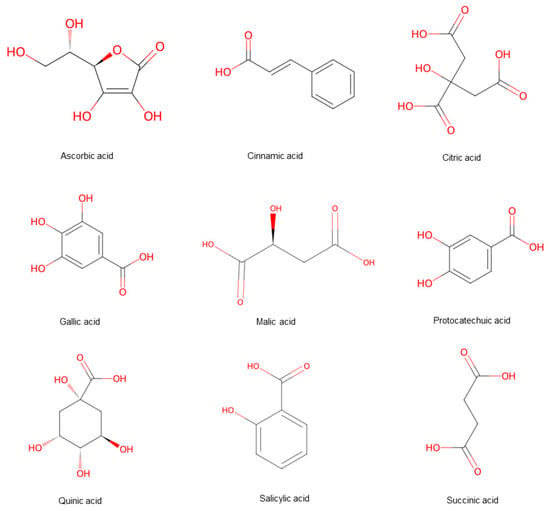

Hawthorn is notable for its high nutritional value, containing some of the highest levels of amino acids, proteins, trace elements, and vitamins among fruits, with particularly significant calcium (Ca2+) content [8]. Organic acids are widely distributed in the leaves, roots, and fruits of plants. Beyond modulating flavor, these organic acids have demonstrated physiological effects, including vasodilation (softening blood vessels), enhanced absorption of calcium and iron, and stimulation of digestive secretions. Consequently, they contribute to increased appetite, improved digestion, and relief from thirst and heat. A total of 76 organic acid metabolites were detected in hawthorn fruits (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hawthorn fruits comprise a variety of acid compounds. Note: Red color means oxygen-containing functional groups.

Citric, malic, quinic, succinic, and ascorbic acids were identified as the predominant types [9]. Phenolic acids, which are derivatives of these organic acids, are notable for their potent antioxidant activity. Recent pharmacological studies have shown that phenolic acids possess various bioactivities, including antidiabetic effects. In vitro studies indicated that phenolic acids primarily exert antidiabetic effects by inhibiting the activity of α-glucosidase and α-amylase, thereby preventing blood glucose elevation [10]. South and North hawthorns contain gallic acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid, while Guang hawthorns contain p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, dihydrocaffeic acid, and genipic acid.

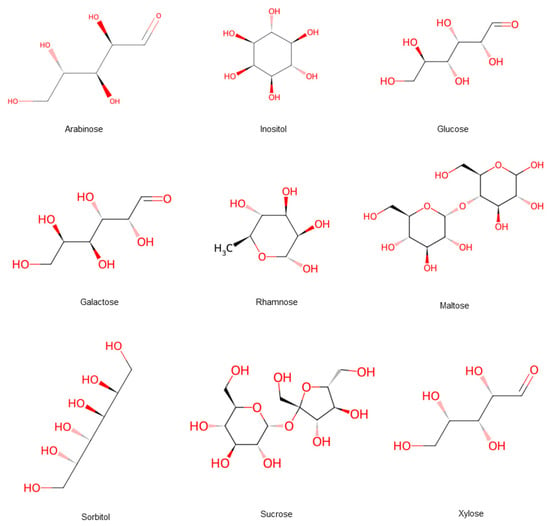

The sugar in hawthorn primarily include maltose, sucrose, glucose, arabinose, galactose, rhamnose, xylose, sorbitol, and inositol, among other sugar and sugar alcohols [11] (Figure 6). It contains some functional sugars with multiple health benefits, such as regulating blood sugar levels. Northern hawthorn has higher total sugar content than its southern counterpart [12]. The sugar contains acidic polysaccharides and galacturonic acid, which form hawthorn pectin, which is a compound with diverse biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-glycation, anti-tumor, and lipid-lowering effects, as well as prebiotic activity and heavy metal removal [7]. Hawthorn pectin is rich in polygalacturonic acid, which can be hydrolyzed by the enzyme polygalacturonase into pectin oligosaccharides. Experimental studies in SAMP8 mice have shown that these functional oligosaccharides exhibit senescence-delaying properties, and possess the primary mechanism involved in interfering with apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide, (H2O2), inhibiting the expression of key cell cycle factors, and stabilizing the cellular state [13]. Hawthorn is rich in pectin, a beneficial compound that has led to the development of various products like jelly, tea, and cake. As the seventh major nutrient, dietary fiber is crucial for preventing and mitigating conditions, such as constipation, hyperglycemia, colorectal cancer, and hypertension. Hawthorn pomace contains the highest levels of dietary fiber, and is therefore often considered a better source of non-traditional dietary fiber. The global annual disease burden indicates that mental disorders are a major public health problem. Consequently, advance treatment approaches like traditional herbal and dietary therapies are gaining attention [14].

Figure 6.

Hawthorn fruits contain a variety of sugar forms. Note: Red color means oxygen-containing functional groups.

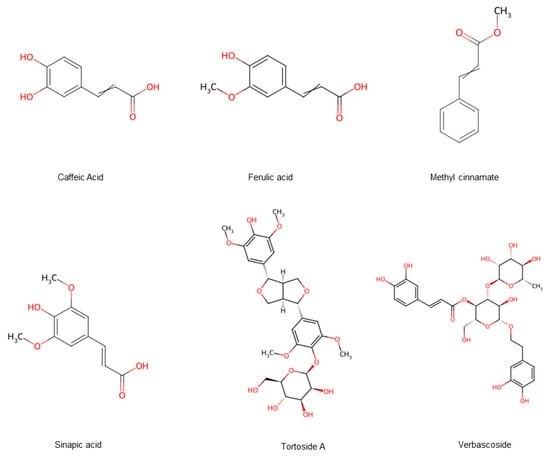

4.2. Phenylpropanoids

Phenylpropanoids are a structurally rich and functionally diverse class of plant secondary metabolites. In hawthorn, 182 phenylpropanoids have been identified (Figure 7), which include simple phenylpropanoids (22 compounds), coumarins (2 compounds), and lignans (158 compounds) [15]. Phenylpropanoids exhibit diverse biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor effects [16]. Studies have shown that more than 150 lignans, a subclass of phenylpropanoids isolated from hawthorn fruits, have demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties. The analysis of these compounds offers the potential for developing advance, cost-effective drugs with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory applications [17,18,19].

Figure 7.

Hawthorn fruits contain phenylpropanoid compounds. Note: Red color means oxygen-containing functional groups.

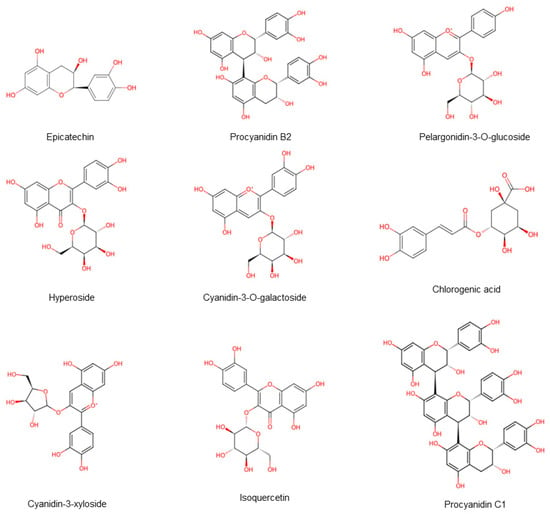

4.3. Phenolic Compounds

Hawthorn ranked first among 30 anti-aging fruits, primarily due to its rich phenolic compounds. These include flavonoids, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins [20] (Figure 8). An acidic environment helps maintain the stability of phenolic compounds, and hawthorn is rich in organic acids, which provides a favorable condition for this stability [21]. Research findings indicated that the composition and concentration of phenolic compounds in plants are affected by numerous factors, including altitude, light exposure, soil conditions, and sampling location, and demonstrate positive correlation with ambient air temperature and sunlight [22]. This is exemplified by the phenolic profiles of different hawthorn species. The total phenolics in Northern hawthorn consist predominantly of chlorogenic acid, proanthocyanidin B2, and epicatechin, whereas in Guang hawthorn, they are primarily chlorogenic acid, phloridzin, and ursolic acid. In addition to its antioxidant activity, hawthorn is beneficial for managing a variety of conditions, including inflammation, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, peptic ulcers, and microbial infections [23]. Researchers identified over 60 flavonoids in hawthorn [24], with the total flavonoid content varying between different varieties and plant parts, ranging from 2.27 to 17.40 mg/g [25]. Studies have found that the total flavonoid content in Southern hawthorn fruits is higher than Northern hawthorn.

Figure 8.

The availability of phenolic compounds in hawthorn fruits. Note: Red color means oxygen-containing functional groups.

For instance, in vitro studies have shown that hawthorn polyphenols aid digestion by influencing lipid and amino acid metabolism and modulating the intestinal microbiota [26,27,28]. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death worldwide and significant health risk in modern society. Early clinical studies indicated that hawthorn is effective in its prevention and treatment [29], as its fruits, leaves, and flowers exhibit antispasmodic, cardiotonic, antihypertensive, and anti-atherosclerotic properties. The antioxidant activity of hawthorn polyphenols and triterpenoids mediates their protective effects, which include inhibiting cell apoptosis [30], increasing myocardial glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity, reducing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels [31], and mitigating nitrosative stress and lipid peroxidation [32]. Furthermore, hawthorn polyphenols can also effectively mitigate other oxidative stress-related diseases, including diabetes [33], inflammation [34], depression [14], hyperlipidemia [35], and bacterial infections [36].

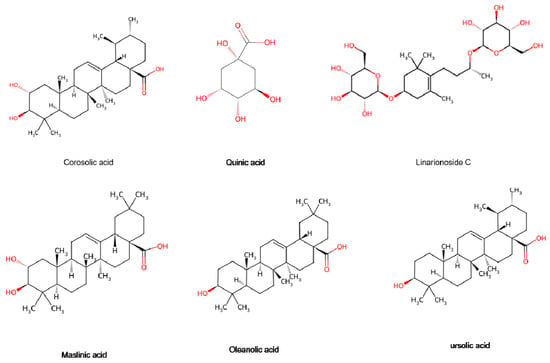

4.4. Terpenoids

Terpenoids are formed by the association of six isoprene units, primarily comprising monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, triterpenes, and their glycosides. At present, 28 distinct terpenoids have been identified in the hawthorn [15] (Figure 9). Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are found in very low concentrations in the fruits but primarily located in the leaves [17]. These compounds serve as significant raw materials for the spice and pharmaceutical industries. As the main phytochemicals in Rosaceae fruits, triterpenoids, primarily triterpene acids, such as oleanolic acid, ursolic acid, and 2α-hydroxyursolic acid, are critical to hawthorn fruit quality [37]. The results of cellular experiments showed that ursolic acid, a major component of triterpenoids, exhibited strong inhibition of the growth of human cancer cells HepG2, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 [37]. These compounds impart potential tumor-relieving properties to hawthorn. We look forward to more scientific clinical studies confirming it as an ideal source of healthy foods with cancer-preventive effects.

Figure 9.

Terpenoids are present in the hawthorn fruits. Note: Red color means oxygen-containing functional groups.

The chemical profile of hawthorn varies significantly between northern and southern varieties. While Southern hawthorn has a lower concentration of ursolic acid, it is richer in corosolic, oleanolic, and quinic acids. These essential oil components are primarily derived from the mixture of terpenoids and phenylpropanoids [38]. There is little research on hawthorn essential oil and the existing research primarily focuses on the extraction and identification of components from its flowers [39,40]. This essential oil has a unique aroma and possesses antiviral and antibacterial properties, making it suitable for use in deterrents and attractants, and in the food, pharmaceutical, and perfume industries [41]. The global tumor burden is increasing, where high incidence and mortality rates present a severe public health challenge. Maslinic acid (MA), a natural pentacyclic triterpene acid found in hawthorn, exhibits anti-cancer effects by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Cell-based studies have verified that MA can regulate different pathways, including the MAPK, OMA1, and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways, which regulate the growth of breast, nasopharyngeal, cervical, and human neuroblastoma cells [42,43,44]. Current cellular studies provide the basis for more clinical research focused on hawthorn actives.

4.5. Other Components

In addition to the aforementioned functional substances, a wide array of other compounds including nitrogen compounds, such as choline, acetylcholine, squalene, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides, alkaloids, peptides, tannins, and saponins have been isolated from various hawthorn tissues [45]. Due to this chemical diversity, hawthorn shows considerable promise as a source for novel lead compounds in drug discovery and as a therapeutic agent for preventing and treating cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and digestive tract diseases, in addition to possessing anti-aging effects [46]. For instance, studies have found that hawthorn ethanol extract (CPE) can inhibit the aggregation and degradation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) [47]. Through separation and identification, compounds including crataeguslignan A and 4″-O-(8-guaiacylglycerol) buddlenol A were isolated as the active ingredients [19]. Amyloid deposits and neuronal fiber tangles are among the causes of Alzheimer’s disease. These findings indicated that this class of compounds may have potential applications in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. However, a large number of clinical studies are still needed to support the evidence.

5. Extraction Process for Functional Materials

The study summarized and discussed the significance of bioactive compounds in hawthorn. To conduct a more scientific analysis of its potential properties, it is necessary to extract these compounds from hawthorn. Currently, the primary extraction methods for preparing water-soluble dietary fiber, hawthorn polysaccharides, flavonoids, and other active functional components domestically and internationally include traditional methods (maceration, percolation, decoction, reflux). Advance approaches include pressurized solvent extraction, countercurrent extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, ultrasonic-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, ultra-high-pressure extraction, rapid solvent extraction, flash extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, dual-phase extraction, fermentation, and combined methods. A comprehensive evaluation of water-based extraction methods determined that the 60 °C water leaching method was the optimal technique for extracting mixed active substances [48]. By optimizing the ultrasonic-assisted extraction process for flavonoids from hawthorn seeds, the optimal conditions were determined, such as an ultrasound temperature of 65 °C, an ultrasonic time of 37 min, an extraction temperature of 91 °C, an extraction time of 90 min, a solid–liquid ratio of 1:18, and 72% ethanol [49]. One of the methods includes an ionic liquid (IL)-based one-step micellar extraction procedure for extracting multiple polar compounds from hawthorn berries. Compared to traditional methods, this approach is simpler, more sensitive, environmentally friendly, and highly efficient [50]. It is a synergistically enhanced DES extraction technique using ultrasonic and resin in situ adsorption to extract phenolic compounds from hawthorn seeds. The results indicated that the process involving choline chloride and oxalic acid, along with non-resin XDA-1, facilitates the extraction of polyphenolic compounds [51]. A comparative analysis of different applications for extracting water-soluble dietary fiber (SDF) from hawthorn pomace was conducted. The results indicated that the microwave-assisted enzymatic method yielded the optimum SDF extraction rate [52].

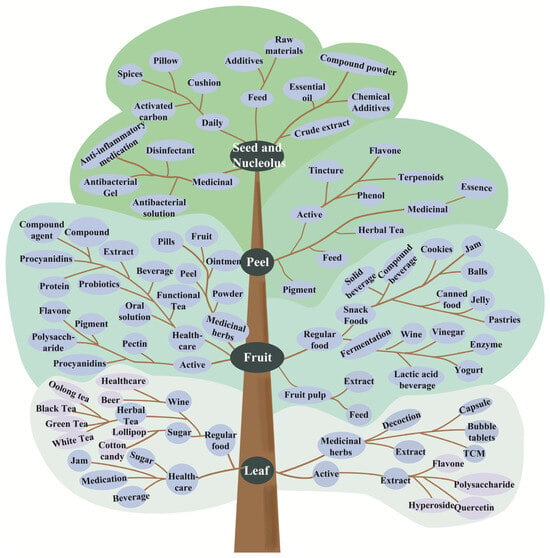

6. Current Research on Hawthorn Processing Applications

The hawthorn plant is edible. Its fruit is dried and pressed for extensive use in the pharmaceutical, food, and agro-industries sectors, including the production of common snacks and health products (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Hawthorn processing layout from different plant parts.

6.1. Hawthorn Leaf

Extensively researched for its potent antioxidant and cytoprotective properties, the often-overlooked hawthorn leaf byproduct can be made into a tea rich in active ingredients, such as polysaccharides, flavonoids, and triterpenes [53]. Polyphenols, the primary antioxidants in hawthorn, effectively scavenge superoxide anions [54]. Supported by correlation analyses, these properties make hawthorn leaf extracts promising for use in functional foods, nutritional supplements, and cosmetic or medical hygiene products [55]. Consequently, the extract has been approved by the China Food and Drug Administration for treating heart disease and hyperlipidemia [56].

6.2. Hawthorn Peel

Hawthorn peel, though often discarded or dried for infusions due to its sour and astringent taste, is a rich source of bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and triterpenoids [57]. Studies indicated that these compounds can be co-extracted, and the peel contains significantly higher levels of polyphenols and flavonoids than fruit pulp, underscoring its promise as a raw material for industrial extraction and medicinal use [58].

6.3. Hawthorn Fruit

The hawthorn fruit serves as the base for over 100 distinct products. These encompass everything from primary processed forms, such as dried, powdered, and pulped hawthorn to traditional delicacies, beverages, and fermented foods. Its applications extend to the pharmaceutical sector and even to other industrial uses like animal feed and feed additives.

6.3.1. Traditional Hawthorn Products

This study systematically studied the packaging, sweeteners, gelling agents, and process optimization for apricot and rose jam composite fruit leather, providing a theoretical basis for its production and storage [59]. A sucrose-free hawthorn fruit peel using oligoxylose and xylitol as sucrose substitutes was shown to prevent constipation [60]. The study also optimized the formula and microwave sugar infiltration process for low-sugar hawthorn preserved fruit from multiple perspectives [61,62]. Furthermore, research on hawthorn cakes has primarily focused on the process of optimization and multi-dimensional formula innovation [63], exemplified by varieties, such as lily, persimmon, and red date hawthorn cakes.

6.3.2. Hawthorn Juice Drinks and Fermented Hawthorn Products

The sour and astringent taste of hawthorn juice, caused by its rich nutrient profile, limits its consumer appeal and sales, making the development of diversified products a key priority. While techniques, such as high-pressure processing [64], are applied to improve the sensory profile of hawthorn juice, its combination with probiotic-rich yogurt presents another avenue for product development [65,66,67]. Yogurt is beneficial for its health benefits, including promoting intestinal health and calcium absorption. Remarkably, fermenting a mixture of hawthorn and yogurt yields a product with viable probiotic count greater (1.86 times) than standard yogurt [68,69]. The national promotion of “fruit-instead-of-grain” winemaking has driven growing interest and market demand for fruit wines, leading to increasingly in-depth research on hawthorn wine and fruit rich in fermentable sugar. Hawthorn wine is produced in various forms, such as hawthorn fruit wine [70], glutinous rice wine [71], brandy [72], distilled wine [73], health wine [74], and beer [75], respectively. Research has mainly focused on processing technology [73], fermentation strains [76], applications, and their impact on quality [77].

Studies indicated that vinegar, which is produced via acetic acid fermentation of alcohol, possesses a blood sugar-lowering effect. While hawthorn is nutritious, its unpalatable taste often leads to its use as a compound ingredient, fermented alongside other fruits to produce composite fruit vinegar [78]. Previous studies on hawthorn vinegar have mainly investigated its production process, aromatic compounds, and health efficacy. The fermentation process, driven by microorganisms like yeast, lactic acid bacteria, and acetic acid bacteria, generates various enzymes and bioactive compounds. Consequently, hawthorn vinegar is classified as a functional food, with purported benefits including regulating acid–base balance, enhancing metabolism, and promoting skin health. Hawthorn pomace, a byproduct of juicing rich in dietary fiber, represents a high-quality substrate for enzymatic preparation. Current research on hawthorn-derived enzymes has largely focused on fermentation methodologies and product quality assessment [79], encompassing specific investigations into mixed-strain fermentation [80], optimization of raw material ratios [81], fermentation process parameters [82], and antioxidant activities [83].

6.3.3. Other Products

Hawthorn, a plant with a long history of medicinal and edible use, is a primary raw material in traditional Chinese medicine and modern health supplements [84,85], encapsulated in products such as hawthorn and danshen dispersible tablets and effervescent tablets. Although a waste product from food production, hawthorn residue has potential as a resource. For example, as a feed additive in aquaculture, it has been shown to improve lipid metabolism and enhance production performance in animals [86,87].

6.4. Hawthorn Kernel

Hawthorn kernels, when processed into powder, function as a valuable raw material. They can be used directly or as an auxiliary substance for the extraction of bioactive compounds, including total flavonoids and phenolic acids [88]. Their versatility allows for further development into a range of products spanning the pharmaceutical, food, and industrial sectors, such as natural medicines, food additives, activated carbon, and specialty oils [89,90]. GC-MS analysis of the main hawthorn seed extracts, obtained by dry distillation at different temperatures, revealed that the fraction collected at 211–230 °C exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity and optimum concentration of major compounds [91].

6.5. Current Status and Prospects of Hawthorn Industry Development

According to the available literature, there are thousands of hawthorn processing and sales companies in China, most of which are small- and medium-sized enterprises. Only a small proportion of companies are large, leading enterprises. Using whole-network big data, the top ten brands of hawthorn products have been selected based on multiple indices, such as brand value, word-of-mouth evaluation, sales volume, and industry recognition. These brands offer more than 30 different product forms, including hawthorn strips, hawthorn slices, hawthorn chicken gizzard slices, and hawthorn tea. Hawthorn processing and sales companies in China are unevenly distributed, heavily influenced by the location of hawthorn cultivation. These companies are primarily located in the Hebei, Shandong, Henan, and Shanxi provinces, as well as major municipalities like Beijing and Shanghai. The production of hawthorn products also includes specialized items like hawthorn powder, paste, and dried fruit mainly produced by pharmaceutical companies, while food items, such as hawthorn cakes, biscuits, and candies are primarily handled by the food processing industry.

A significant challenge is the lack of leading companies and advanced processing for different hawthorn products. Items like hawthorn shreds, honey, and jam have few top-ten-ranked producers and are typically only primary processed, indicating limited technological development. Simple processing technologies, such as drying, boiling, and distillation are low in technical complexity and low in product-added value. Consequently, the market exhibits significant disparity among enterprises, with a clear divide between those producing a diverse product line and those limited to only one or two varieties. Guangxi is a leading production region for large-fruit hawthorn in China, with a cultivation area exceeding 10,000 ha and an annual output of approximately 60,000 tons. The local industry includes ten major agroprocessing plants that produce a variety of products, such as hawthorn cakes, slices, wine, and vinegar. Even so, Guangxi has not been considered in the top ten brands. This shows that the evaluation, sales, and industry recognition of hawthorn enterprises in Guangxi still need to be improved globally.

7. Conclusions and Future Outlook

This paper compiled the distribution of Chinese hawthorn germplasm, along with its nutritional and functional components, processing strategies, and industrial status. Furthermore, we present a novel taxonomic tree of its germplasm resources, offering a clearer systematic understanding of the plant. Hawthorn is an important medicinal and edible plant, valued for its unique flavor, rich nutritional profile, and abundance of bioactive substances. Researchers have analyzed its nutrients, verified its health benefits, and optimized processing approaches. Consequently, entrepreneurs have developed a diverse range of hawthorn products, spanning from primary foods and refined extracts to chemical and pharmaceutical applications. Analysis of hawthorn enterprise landscape indicates an industry characterized by limited scale and uneven regional development. China’s Guangxi province, which is a key producer of large-fruited hawthorn, is notably underrepresented among the industry’s top-tier brands. For Guangxi’s hawthorn enterprises to gain a competitive edge, significant improvements are required in different areas, including brand value, market reputation, sales volume, industry standing, brand heritage, international footprint, and accolades.

The world hosts a rich diversity of hawthorn species with complex phylogenetic relationships. Although China is a key center of origin for the genus, the evolutionary history of these plants remains controversial and requires further study. Furthermore, the establishment of core germplasm collections and molecular identification of local varieties are still limited. To support the conservation, evaluation, and breeding resources of hawthorn, molecular analyses of genetic diversity are urgently needed. These analyses should employ techniques, such as morphology, molecular markers, and simplified genome sequencing. Furthermore, research has confirmed that the pharmacological activity of hawthorn is primarily attributed to flavonoids like quercetin and hyperoside, as well as phenolic acids, which are often used as international quality control standards. However, the Chinese pharmacopeia uses only organic acids as indicators, which fails to fully reflect the active ingredients. Therefore, incorporating flavonoids into the quality control system is crucial in years to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, resources: F.Z., and J.C.; resources and software: Y.T., X.D., X.W., and B.L.; writing—original draft: F.Z., and, J.C.; writing—review and editing: K.K.V., and G.-L.C.; project management, funding acquisition and supervision, validation and visualization: F.Z., and G.-L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guangxi Science and Technology Program (GNK-AB241484003), the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System Guangxi Innovation Team—Specialty Fruits (nycytxgxcxtd-2024-17), and the Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences Basic Research Business Project (GNK2026YT164, GNK2025YP145).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Authors did not use any animal or human experimental materials and are therefore not subject to their ethical concerns. The present research did not involve human participants and/or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data generated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Guangxi Subtropical Crops Research Institute, Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanning, Guangxi, China for providing the necessary facilities for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jia, J.X.; Jia, D.X.; Ren, Q.M. Crops and their wild relatives in China. In Volume of Fruit Crops; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 57–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H. Research progress on character identification and organic acid compositions of Shanzha (Crataegus pinnatifida), Nanshanzha (south Crataegus) and Guangshanzha (cantonese Crataegus). J. Liaoning Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2023, 25, 132–137, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, J.B. Biogeographic, taxonomic, and cladistic relationships between East Asiatic and North American Crataegus. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1983, 70, 667–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhou, Y. Study of Characteristics and Utilization Value of Malus Doumeri in Guangxi. For. Investig. Des. 2014, 2, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.M. Chinese Materia Medica; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 1–252. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Bu, H.; Zhang, T.; Lao, Y.; Dong, W. Molecular analysis of evolution and origins of cultivated Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) and related species in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Gao, X.; Liu, J.; Chitrakar, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y. Hawthorn pectin: Extraction, function and utilization. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Albu, C.; Alecu, A.; Seciu-Grama, A.-M.; Radu, G.L. Antioxidant and antidiabetic activity of Cornus mas L. and Crataegus monogyna Fruit Extracts. Molecules 2024, 29, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, R.; Guo, R.; Nong, H.; Qin, Y.; Dong, N. Integrative analysis of metabolome and transcriptome reveals molecular insight into metabolomic variations during hawthorn fruit development. Metabolites 2023, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczykolan, A.; Pietrzak, W.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Nowak, R. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-diabetic activity of phenolic acids fractions obtained from Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. Molecules 2021, 26, 3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazhand, A.; Lucarini, M.; Durazzo, A.; Zaccardelli, M.; Cristarella, S.; Souto, S.B.; Silva, A.M.; Severino, P.; Souto, E.B.; Santini, A. Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.): An updated overview on its beneficial properties. Forests 2020, 11, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Bu, A.; Wang, B.; Sun, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, B.; Wang, A. Sugar and organic acid metabolism and accumulation in different cultivars during fruit development in hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida). Food Qual. Saf. 2025, 9, fyaf010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, D.; Lin, G.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L.; Ai, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, M.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Chen, X.; et al. Anti-ageing and antioxidant effects of sulfate oligosaccharides from green algae Ulva lactuca and Enteromorpha prolifera in SAMP8 mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.W.; Han, T.; Jung, J.; Song, Y.; Um, M.Y.; Yoon, M.; Kim, Y.T.; Cho, S.; Kim, I.; Han, D.; et al. Chlorogenic acid from Hawthorn berry (Crataegus pinnatifida Fruit) prevents stress hormone-induced depressive behavior, through monoamine oxidase B-reactive oxygen species signaling in hippocampal astrocytes of mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Yang, X.; Shi, P.; Xu, L.; Guo, Q. Botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activity of Crataegus pinnatifida (Chinese hawthorn): A review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 74, 1507–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Lv, T.; Shang, X.; Yao, G.; Lin, B.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Song, S. Racemic neolignans from Crataegus pinnatifida: Chiral resolution, configurational assignment, and cytotoxic activities against human hepatoma cells. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Liao, B.; Fan, M.; Duan, B. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and safety concerns of hawthorn (Crataegus genus): A comprehensive review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Luan, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, M.; Lu, Y.; Tao, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Wan, L. Crataegus pinnatifida: A botanical, ethnopharmacological, phytochemical, and pharmacological overview. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 301, 115819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Lou, L.L.; Zhang, H.; Guo, R.; Wang, X.B.; Huang, X.X.; Song, S.J. A new dineolignan with anti-β-amyloid aggregation activity from the fruits of crataegus pinnatifida bge. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2112–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, P. Composition and health effects of phenolic compounds in hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) of different origins. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1578–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningsih, S.; Wulandari, L.; Wartono, M.W.; Munawaroh, H.; Ramelan, A.H. The effect of pH and color stability of anthocyanin on food colorant. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 193, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, F. HPLC Determination of eight polyphenols in the leaves of Crataegus pinnatifida Bge. var. major. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2009, 47, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Dey, S.; Marbaniang, D.; Pal, P.; Ray, S.; Mazumder, B. Grape seed extract: Having a potential health benefits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chai, X.; Zhao, F.; Hou, G.; Meng, Q. Food applications and potential health benefits of hawthorn. Foods 2022, 11, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkin, V.A.; Pravdivtseva, O.E.; Shaikhutdinov, I.K.; Kurkina, A.V.; Volkova, N.A. Quantitative determination of total flavonoids in blood-red hawthorn fruit. Pharm. Chem. J. 2020, 54, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, C.; Jin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, H.; Hanna, M.; Yuan, L. Phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity of Crataegus pinnatifida fruit infusion and decoction and influence of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on their digestive recovery. LWT 2021, 135, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Yan, M.; Zhao, X.; Jin, H.; Gong, Y. Effect of hawthorn seed extract on the gastrointestinal function of rats with diabetic gastroparesis. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 130, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Shi, D.; Wang, H.; Chang, X. Microencapsulated hawthorn berry polyphenols alleviate exercise fatigue in mice by regulating AMPK signaling pathway and balancing intestinal microflora. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 97, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.E.; Brown, P.N.; Talent, N.; Dickinson, T.A.; Shipley, P.R. A review of the chemistry of the genus Crataegus. Phytochemistry 2012, 79, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayalakshmi, R.; Devaraj, S.N. Cardioprotective effect of tincture of Crataegus on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2004, 56, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Jiang, W.; Xiong, X.; Chen, J.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y. Ethanol extract of Chinese hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida) fruit reduces inflammation and oxidative stress in rats with doxorubicin-induced chronic heart failure. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e926654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, N.A.; Thiruchenduran, M.; Devaraj, S.N. Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of Crataegus oxyacantha on isoproterenol-induced myocardial damage. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 367, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Q.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, M.; Liu, D.; Diao, T.; Lv, W. Hawthorn leaf flavonoids protect against diabetes-induced cardiomyopathy in rats via PKC-α signaling pathway. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 2071952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.J.; Li, Y.; Cao, Q.H.; Wu, H.X.; Tang, X.Y.; Gao, X.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. In vitro and in vivo evidence that quercetin protects against diabetes and its complications: A systematic review of the literature. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, H.; Lin, H.; Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.; Chen, C.; Chyau, C. Protective effect of hawthorn fruit extract against high fructose-induced oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic β-cells. Foods 2022, 12, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, L.F.; Xu, J.G. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and action mechanism of different extracts from hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida Bge.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Guo, R.; You, L.; Abbasi, A.M.; Li, T.; Fu, X.; Liu, R.H. Major triterpenoids in Chinese hawthorn “Crataegus pinnatifida” and their effects on cell proliferation and apoptosis induction in MDA-MB-231 cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 100, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouville, A.S.; Erlich, G.; Azoulay, S.; Fernandez, X. Forgotten perfumery plants—Part I: Balm of Judea. Chem. Biodiversity 2019, 16, e1900506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, X.; Bouville, A.S.; Portes, P.; Lhommet, J.C.; Azoulay, S. Forgotten perfumery plants: Hawthorn volatile extract study. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2024, 36, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havsteen, B.H. The biochemistry and medical significance of the flavonoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 96, 67–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Grover, A. Maslinic acid differentially exploits the MAPK pathway in estrogen-positive and triple-negative breast cancer to induce mitochondrion-mediated, caspase-independent apoptosis. Apoptosis 2020, 25, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.-W.; Yang, M.-D.; Peng, S.-F.; Chen, J.-C.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lu, T.-J.; Chueh, F.-S.; Lien, J.-C.; Lai, K.-C.; et al. Maslinic acid induces DNA damage and impairs DNA repair in human cervical cancer HeLa cells. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 6869–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Dong, Q.; Hao, X.; Qiao, L. Maslinic acid induces anticancer effects in human neuroblastoma cells mediated via apoptosis induction and caspase activation, inhibition of cell migration and invasion and targeting MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. AMB Express 2020, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Peng, W.; Qin, R.; Zhou, H. Crataegus pinnatifida: Chemical constituents, pharmacology, and potential applications. Molecules 2014, 19, 1685–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Cui, L.; Liu, S.; Fei, Y.; Tao, Q.; Chang, X. Research progress on functional components and processing of hawthorn. Food Res. Dev. 2017, 15, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, E.; Kwon, H.; Jeon, J.; Jung, C.J.; Moon, M.; Jun, M.; Lee, Y.C.; Kim, D.H.; Jung, J.W. The fruit of Crataegus pinnatifida ameliorates memory deficits in β-amyloid protein-induced Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 243, 112107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, P.C.; Leclercq, L.; Rossi, J.-C.; Desvignes, I.; Hertzog, J.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Chemat, F.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Cottet, H. Optimizing water-based extraction of bioactive principles of hawthorn: From experimental laboratory research to homemade preparations. Molecules 2019, 24, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Yu, G.; Zhu, C.; Qiao, J. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) of flavonoids compounds (FC) from hawthorn seed (HS). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012, 19, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.S.; Yi, L.; Li, X.Y.; Cao, J.; Ye, L.H.; Cao, W.; Da, J.H.; Dai, H.B.; Liu, X.J. Ionic liquid-based one-step micellar extraction of multiclass polar compounds from hawthorn fruits by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5275–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; He, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Yang, P.; Niu, Q. Enhanced deep eutectic solvent extraction of phenolic compounds from hawthorn seeds with ultrasonic and resin in-situ adsorption assistance: Process optimization, component analysis, and extraction mechanism. Food Chem. 2025, 480, 143885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qixin, Z.; Yong, W.; Suwen, L.; Yongping, X.; Shuyu, W.; Xuedong, C. The effects of different extraction methods on structure and functional properties of soluble dietary fiber in hawthorn pomace. Food Ferment. Indust. 2024, 50, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, G.; Liu, Y.; Lin, X.; Gao, P.; Wang, F.; Zhou, L.; Li, L. Bioactive compounds from Crataegus pinnatifida Bge. leaves: Potential health benefits. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Shao, T.; Peng, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Su, H. Chemical composition, biological activities, and quality standards of hawthorn leaves used in traditional Chinese medicine: A comprehensive review. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1275244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurek, N.; Świeca, M.; Kapusta, I.T. Berries, leaves, and flowers of six hawthorn species (Crataegus L.) as a source of compounds with nutraceutical potential. Molecules 2024, 29, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.Y.; Liu, R.H.; Xu, X.D.; Yu, M.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.L. The pharmacokinetics of C-glycosyl flavones of Hawthorn leaf flavonoids in rat after single dose oral administration. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B.; Ji, Z.; Chen, W. Phytochemical compositions of extract from peel of hawthorn fruit, and its antioxidant capacity, cell growth inhibition, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, W.; Huang, D.; Yang, X. Polyphenols from hawthorn peels and fleshes differently mitigate dyslipidemia, inflammation and oxidative stress in association with modulation of liver injury in high fructose diet-fed mice. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016, 257, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmamat, G.; Zuoshan, F.; Yujia, B. Effect of packing method on storage quality of apricot and rose paste composite fruit peel and establishment of shelf life model. Food Ferment. Indust. 2025, 51, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, L.-H.; Liu, J.; Yan, Q.J.; Jiang, Z.Q. Preventive effects of sugar-free hawthorn rolls on constipation in mice. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2020, 41, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L. Research on processing technology of low sugar hawthorn preserved fruits. Food Nutr. China 2015, 4, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Xiao-xian, T.; Qiao, Z.; Fei-fei, S.; Ding-jin, L.; Wen, C.; Zhen-hua, D. Processing technology of low-sugar preserved Malus domeri (Bois) Chev. by microwave-assisted sugar permeation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Gao, Q.; Ran, K.; Jiao, M.; Fu, X.; Han, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, N. The nutritional and bioactive components, potential health function and comprehensive utilization of hawthorn: A review. Food Front. 2025, 6, 2108–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Jin, Y.; Tian, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Hanna, M.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, H. High-pressure and thermal processing of cloudy hawthorn berry (Crataegus pinnatifida) juice: Impact on microbial shelf-life, enzyme activity and quality-related attributes. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shan, W.; Han, Y.; Li, X. Solid-state fermentation with lactic acid bacteria of citric acid degrading for hawthorn fruit improvement: Sensory, flavor, antioxidant properties. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Lei, H. Effect of lactic acid bacteria fermentation on physicochemical properties, phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity and volatile components of hawthorn juice. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Guo, X. Optimization of blanching process of hawthorn using central composite design and response surface method. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 632, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, S. Effects of yam powder produced by different drying ways on the quality and antioxidant activity of greek style yogurt during refrigeration. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2025, 46, 200−207, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Ma, L. Storage quality and antioxidant properties of yam and hawthorn yogurt under gastrointestinal fluid environment. China Brew. 2021, 40, 124–128, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Xiong, J.; Sun, J.; Du, F.; Xu, G.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Lou, X. Dynamic transformation in flavor during hawthorn wine fermentation: Sensory properties and profiles of nonvolatile and volatile aroma compounds coupled with multivariate analysis. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 139982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Luo, L. Optimization of brewing technology and quality evaluation of sparkling hawthorn Huangjiu. China Brew. 2022, 41, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Guo, N.; Tong, H.; Ye, J. Optimization of vacuum distillation process of hawthorn distilled liquor and effect of the process on flavor components. China Brew. 2022, 41, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Lv, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Z. Effects of different pretreatments on physicochemical properties and phenolic compounds of hawthorn wine. CyTA—J. Food 2020, 18, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, W.; Chen, S.; Chen, A.; Li, C. Development of Polygonatum sibiricum-haw wine and analysis of its volatile compounds. Liquor.-Mak. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiński, A.; Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Szumny, A.; Gąsior, J.; Głowacki, A. Assessment of volatiles and polyphenol content, physicochemical parameters and antioxidant activity in beers with dotted hawthorn (Crataegus punctata). Foods 2020, 9, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Mu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yi, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Effects of different lactic acid bacteria on the physicochemical properties, functional characteristics and metabolic characteristics of fermented hawthorn juice. Food Chem. 2025, 470, 142672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenc, F.; Jarošová, M.; Bedrníček, J.; Nohejl, V.; Míková, E.; Smetana, P. Effect of wine yeast (Saccharomyces sp.) strains on the physicochemical, sensory, and antioxidant properties of plum, apple, and hawthorn wines. Foods 2025, 14, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, G.B.; Özdemir, N.; Ertekin-Filiz, B.; Gökırmaklı, Ç.; Kök-Taş, T.; Budak, N.H. Volatile aroma compounds and bioactive compounds of hawthorn vinegar produced from hawthorn fruit (Crataegus tanacetifolia (lam.) pers.). J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Bian, H.J.; Bao, J.K. Molecular mechanisms of Polygonatum cyrtonema lectin-induced apoptosis and autophagy in cancer cells. Autophagy 2009, 5, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Tian, J.; Bi, J.; Peng, X.; Gao, J. Optimization of fermentation technology and its in-vitro activity of hawthorn enzyme. Food Mach. 2025, 40, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, L.; Tong, L.; Guo, D.; Ji, X. Optimization and scale-up of fermentation processes driven by models. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Gao, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Mu, G.; Wu, X. Influence of soaking Malus domeri (Bois) Chev. Leaves on gut microbiota and metabolites of long-living elderly individuals in Hezhou city, Guangxi, China. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chang, X.; Liu, X.; Shen, Z. Effects of pretreatments on anthocyanin composition, phenolics contents and antioxidant capacities during fermentation of hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida) drink. Food Chem. 2016, 212, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabdelli, F.; Bekhti, N.; Piras, A.; Benhafsa, F.M.; Ilham, M.; Adil, S.; Anes, L. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Crataegus monogyna leaves’ extracts. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 3234–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Li, H.; Yuan, Y.N.; Dai, H.Q.; Yang, B. Antioxidant activity and components of a traditional chinese medicine formula consisting of Crataegus pinnatifida and Salvia miltiorrhiza. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ho, W.K.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; James, A.E.; Lam, L.W. Hawthorn fruit is hypolipidemic in rabbits fed a high cholesterol diet. J. Nutr. 2001, 132, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Jiang, G.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Li, C.; Wu, D.; Dai, Q. Effects of enzyme supplementation on the nutrient, amino acid, and energy utilization efficiency of citrus pulp and hawthorn pulp in Linwu ducks. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2018, 50, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasain, J.K.; Peng, N.; Dai, Y.; Moore, R.; Arabshahi, A.; Wilson, L.; Barnes, S.; Michael Wyss, J.; Kim, H.; Watts, R.L. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry identification of proanthocyanidins in rat plasma after oral administration of grape seed extract. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 1886.127-2016; National Food Safety Staandards-Food Additives—Hawthorn Nuclear Smoked Flavouring Material I, II. China Quality and Standards Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2016. Available online: https://www.ChineseStandard.net/PDF.aspx/GB1886.127-2016 (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Kwek, E.; Yan, C.; Ding, H.; Hao, W.; He, Z.; Liu, J.; Ma, K.Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.Y. Effects of hawthorn seed oil on plasma cholesterol and gut microbiota. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, H.; Li, P.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Peng, W.; Su, W. Simultaneous determination of six compounds in destructive distillation extracts of hawthorn seed by GC-MS and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.