Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infection is a primary cause of gastritis and gastric ulcers. It is crucial to find alternative therapies for H. pylori infection due to the significant side effects of current antibiotics. Heyndrickxia coagulans is an ideal probiotic due to its functionality and stability in production and storage. This study explored the anti-bacterial effects of H. coagulans BHE26 in vitro and in vivo. H. coagulans BHE26 showed notable tolerance to simulated gastric juice (pH 3.0) and 1% bile salts, highlighting its potential suitability for gastrointestinal survival. H. coagulans BHE26 was resistant to ceftriaxone but sensitive to penicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, lincomycin, tetracycline and chloramphenicol. These characteristics showed that H. coagulans BHE26 is a potential probiotic bacterium. In vitro assays demonstrated that H. coagulans BHE26 inhibited H. pylori, reduced urease activity, and displayed notable auto-aggregation and co-aggregation abilities. In vivo, administration of H. coagulans BHE26 alleviated H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal damage, significantly lowered serum anti-bacterial IgG levels, and modulated gastric microbiota composition, including an increase in Turicibacter and a decrease in Lactobacillus abundance. These results indicate that H. coagulans BHE26 alleviated H. pylori-induced inflammation, offering a novel therapeutic strategy against H. pylori infection.

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a widespread human pathogen that colonizes the gastric mucosa [1,2]. Over half of the global population is infected with H. pylori, with a reported prevalence of 55.8% in China [3]. Long-term infection can cause a series of gastrointestinal diseases, such as chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [4,5]. H. pylori infection and its related diseases pose a substantial health burden in China and remain a significant global public health concern [6]. Antibiotic-based regimens, primarily comprising amoxicillin and metronidazole, remain the first-line treatment for H. pylori infection [7]. In recent years, antibiotic resistance has become an increasing concern worldwide. Rising antibiotic resistance has steadily reduced the success of H. pylori eradication [8]. Additionally, antibiotic treatment can disrupt gut microbiota, causing adverse effects such as diarrhea, anorexia, and bloating [9,10]. These risks are particularly concerning for vulnerable populations, including children, pregnant women, and lactating individuals [11]. Thus, identifying safer and more effective eradication strategies remains a major global clinical challenge.

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits, are widely used to maintain the microbial homeostasis and support intestinal health. In H. pylori eradication programs, probiotics have gained increasing attention for their ability to enhance eradication rates and reduce the adverse effects of antibiotic therapy [12,13,14]. Both the European Maastricht VI Consensus and the Sixth Chinese Consensus on H. pylori infection recommend probiotic supplementation as an adjunct to standard eradication regimens [15,16,17]. Thus, identifying probiotics with strong anti-bacterial activity is crucial for improving treatment strategies.

Heyndrickxia coagulans is a thermotolerant, spore-forming, lactic acid-producing bacterium. Its ability to form resistant endospores ensures high survival during storage, gastrointestinal transit, and food processing [18]. In recent years, the growing consumer demand for health-promoting foods has driven a rapid expansion in the application of probiotics in the functional food industry. Heyndrickxia coagulans is used in the food industry, such as in wine making and sugar production, owing to its butyric acid-producing and fermentation capabilities [19,20]. It is used as a food additive for dairy products and pasta due to its excellent heat resistance and harsh-environment resistance [20]. Notably, H. coagulans is the only spore-forming bacterium approved for use as a food ingredient in China, offering advantages in storage and transportation, and application [21,22]. However, studies on its inhibitory effects against H. pylori are still limited. Current research on H. coagulans primarily focuses on its role in modulating immunity, alleviating constipation, mitigating acute alcohol intoxication and restoring intestinal microbiome homeostasis [23,24,25]. Fermented foods represent rich and diverse microbial ecosystems that have yielded multiple Lactobacilli with anti-bacterial activity [26]. However, H. coagulans with comparable inhibitory potential remains largely underexplored. To date, no systematic studies have isolated and characterized H. coagulans from fermented foods with anti-H. pylori activity. Therefore, screening H. coagulans with anti-H. pylori activity from fermented foods (homemade soybean paste) is crucial for the prevention and treatment of H. pylori infections.

We have isolated a strain of H. coagulans BHE26 with inhibitory effects against H. pylori, deposited under the accession number CGMCC No. 30414 [27]. The inhibitory and strain-specific properties were analyzed after determining anti-bacterial activity, acid resistance, hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation and co-aggregation. Animal experiments evaluated the effects of H. coagulans BHE26 on H. pylori infection in vivo, using gastric urease activity, histopathology, serum anti-bacterial IgG levels, and microbiota changes as key indicators. This study developed a H. coagulans strain with gastric tolerance and anti-bacterial activity, suggesting its potential application in dietary interventions for H. pylori management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

H. coagulans BHE26 (CGMCC No.30414, E26) was stored at the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC). H. pylori SS1 (GDMCC 1.1824) was obtained from Hangzhou Baosai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 (LP) was provided by Hebei Yiran Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shijiazhuang, China). Brain heart infusion broth (BHI) was from Hope Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China). The bile salts and urease were from Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Pepsin, trypsin, proteinase K, papain, and bile salts were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The other reagents were of analytical grade.

H. pylori was cultured on Columbia agar Base (CAB) under microaerophilic conditions for 72 h. H. pylori colonies were scraped from the agar surface and resuspended in BHI broth supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum to adjust the bacterial concentration to an optical density (OD600) of 0.10 ± 0.01. The modified glucose-supplemented de Man Rogosa Sharpe (GMRS) agar (20 g glucose; 10 g yeast extract; 10 g peptone; 2.68 g K2HPO4·3H2O; 0.05 g manganese sulfate; 0.048 g magnesium sulfate; 2 g ammonium citrate; and 15 g agar dissolved in 1 L distilled water).

2.2. In Vitro Anti-Bacterial Activity of H. coagulans BHE26

The anti-bacterial activity of H. coagulans BHE26 was evaluated using the agar well diffusion assay as described by Paucar-Carrión et al. with minor modifications [28]. Briefly, H. pylori suspension (OD600 = 1.0 in BHI) was spread evenly on Columbia blood agar plates supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Wells with a diameter of 6 mm were made using a sterile cork borer. Each well was filled with 50 μL of GMRS (negative control), Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 (positive control), 50 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing H. coagulans BHE26 (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL), or 50 μL of the supernatant obtained from H. coagulans BHE26 culture after centrifugation at 8000× g for 10 min using a high-speed refrigerated centrifuge (LYNX 6000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The plates were incubated under microaerophilic conditions at 37 °C for 72 h, and the diameters of the inhibition zones were measured. The values were determined by three independent experiments.

2.3. Characterization of Antimicrobial Compounds from H. coagulans BHE26

Protease sensitivity assays: The cell-free supernatant (CFS) from H. coagulans BHE26 was treated with different enzymes to determine the nature of the compounds responsible for the antimicrobial activity. Pepsin (pH 3.0), acid protease (pH 3.0), trypsin (pH 7.0), proteinase K (pH 7.0), or papain (pH 7.0) was added to 50 mL CFS to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL at 37 °C for 1 h. To evaluate the influence of pH, the CFS was adjusted to pH 7.0 using 1 mol/L NaOH. Bacterial viability was determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining and quantified by flow cytometry (Accuri C6 Plus, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The inhibitory effect was expressed as the percentage of H. pylori death relative to the untreated control. Each experiment was carried out in three parallel replicates. Inhibition rate (%) was calculated according to the following formula:

where N1 represents the number of PI-positive (non-viable) cells, and N0 represents the total number of detected cells (PI-positive + PI-negative).

Inhibition rate (%) = N1/N0 ∗ 100

Organic acid profile: The concentrations of organic acids in the 24 h fermentation supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; LC-20AT, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Briefly, the strain was cultured in MRS broth at 37 °C for 24 h. Cultures were centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min using a high-speed refrigerated centrifuge (LYNX 6000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The CFS was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed using an Aminex HPX-87H column (300 × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) maintained at 30 °C, with phosphate buffer as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The detection was carried out at 215 nm. Lactic acid and acetic acid were used as standards.

2.4. Tolerance to Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions

Preparation of gastric fluid: The pH of sodium chloride (0.3%, w/v) was adjusted to 3.0 with concentrated hydrochloric acid. After the addition of protease (0.35%, w/v), the solution was filtered with a 0.22 mm filter. The tolerance to artificial gastric fluid was assessed following the method of Zhang et al. with slight modifications [29]. Briefly, the suspension (0.5 mL, 108 CFU/mL) of H. coagulans BHE26 was diluted in the artificial gastric fluid (4.5 mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Then, astric fluid tolerance was assessed by mixing 0.5 mL of the suspension with 4.5 mL of simulated astric fluid, followed by static incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The viable bacterial counts were determined using the pour plate method. Data are presented as:

where Nt represents the number of surviving cells, and N0 denotes the number of initial cells.

Survival rate (%) = LgNt/LgN0

Bile tolerance: The bile tolerance of H. coagulans BHE26 was evaluated as previously described by Angmo et al. with some modifications [30]. H. coagulans BHE26 (10%, v/v) was inoculated into GMRS broth containing 0% (m/v) and 1.0% (m/v) bile salts, respectively. After a reactivation step at 37 °C for 4 h, the culture (100 μL, 108 CFU/mL) was serially diluted and spread onto agar plates. Although the physiological bile salt concentration in the human small intestine is approximately 0.3% [31], 1% was used to evaluate the maximum tolerance and robustness of the strain under extreme stress conditions. After a 24 h incubation at 37 °C, surviving colonies were enumerated using standard colony-forming unit (CFU) counts. All experiments were performed in three independent replicates to ensure reproducibility.

2.5. The Agglutination Activity of H. coagulans BHE26

2.5.1. Hydrophobicity

The concentration of H. coagulans BHE26 cells was adjusted to 108 CFU/mL with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 10 mmol/L, pH 7.4). Equal volumes of the H. coagulans BHE26 suspension (2 mL) and xylene (2 mL) were mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 was applied as the positive control. The OD600 was then measured. Hydrophobicity was calculated as follows:

where A0 represents the absorbance at 0 h, and At denotes the absorbance measured at time t (h) after the addition of xylene

Hydrophobicity (%) = (A0 − At) ∗ 100%/A0.

2.5.2. Auto-Aggregation

The auto-aggregation capacity of H. coagulans BHE26 was determined according to the method of Fonseca et al. with slight modifications [32]. The H. coagulans BHE26 cells were adjusted to 108 CFU/mL with PBS (10 mmol/L, pH 7.4) and incubated statically at 37 °C for 48 h. The OD600 of the upper liquid was measured at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 16, 24, and 48 h. Auto-aggregation was calculated as follows:

where A0 and At are the absorbance values of the upper liquid at 0 h and t h, respectively.

Auto-aggregation (%) = (A0 − At) ∗ 100%/A0

2.5.3. Co-Aggregation

The concentrations of H. pylori, H. coagulans BHE26 and Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 (positive control) were adjusted to 108 CFU/mL with PBS (10 mmol/L, pH 7.4). The bacterial suspensions of H. coagulans BHE26 and L. plantarum CN2018 were each combined with the H. pylori in equal volumes and incubated statically at 37 °C for 48 h. The absorbance of the upper solution were measured at 600 nm at various times. Co-aggregation was calculated as follows:

where A0 and Amix refer to the OD600 of the upper solution at 0 h and at various incubation times, respectively.

Co-aggregation (%) = (A0 − Amix) ∗ 100%/A0

2.6. Antibiotic Susceptibility and Safety Assessment

The antibiotic susceptibility of H. coagulans BHE26 was evaluated using the method of Huang et al. with slight modifications [33]. Briefly, H. coagulans BHE26 cells (1.0 × 108 CFU/mL, 100 μL) was spread on GMRS agar plates. Antibiotic discs including penicillin (10 μg), gentamicin(10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), lincomycin (2 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25 μg), were then placed on the surfaces of GMRS agar plates, respectively. After incubating the plates at 37 °C for 24 h, the inhibition zones were measured.

H. coagulans BHE26 was spot-inoculated onto a blood agar plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Hemolytic activity was classified as α-hemolysis (greenish discoloration surrounding the colonies), β-hemolysis (clear zones of lysis around the colonies), and γ-hemolysis (absence of any zone surrounding the colonies). Staphylococcus aureus served as the positive control.

2.7. Effect of H. coagulans BHE26 on H. pylori Infected Mice

2.7.1. Animals and Treatments

A total of 108 male C57BL/6J mice (5 weeks old, 20–24 g) were purchased from Zhejiang Viton Lihua Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Jiaxing, China). All animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines established by the Welfare and Ethics Review Committee of Zhengzhou University Laboratory Animal Center (approval number: ZZU-LAC20211015[15]). After one week of acclimatization, the mice were randomly allocated into two main experimental sets: the therapeutic intervention (n = 60) and preventive intervention (n = 48).

In the therapeutic experiment, mice were assigned to five groups (n = 12 per group): Control (Con), infection control (Hp_0), therapeutic control (Hp_GMRS), H. pylori treatment (Hp_E26), and supernatant treatment (Hp_E26_FS). The H. pylori infection model was established by oral gavage with 0.2 mL of H. pylori suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL) every other day for four doses. After infection, mice in the therapeutic groups received the following treatments for four weeks.

- •

- Con group—gavaged daily with sterile water (0.2 mL/day);

- •

- Hp_0 group—infected with H. pylori and gavaged daily with sterile water (0.2 mL/day);

- •

- Hp_GMRS group—infected with H. pylori and gavaged daily with 0.2 mL of GMRS medium;

- •

- Hp_E26 group—infected with H. pylori and treated daily with H. coagulans BHE26 suspension (5 × 108 CFU/mL, 0.2 mL/day);

- •

- Hp_E26_FS group—infected with H. pylori and treated daily with 24 h fermented supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 (0.2 mL/day).

The dose, dosing frequency, oral gavage route, and treatment duration were selected to align with regimens commonly used in murine probiotic models of H. pylori infection.

In the preventive experiment, mice were divided into four groups (n = 12 per group): Control (Con), infection control (Hp_1), prevention group (E26_Hp), and H. coagulans BHE26-only group (E26). Treatments were arranged as follows:

- •

- Con group—gavaged with sterile water throughout the experiment;

- •

- Hp_1 group—gavaged with sterile water for 3 weeks prior to H. pylori infection and continued during infection;

- •

- E26_Hp group—gavaged with H. coagulans BHE26 (5 × 108 CFU/mL, 0.2 mL/day) for 3 weeks before H. pylori challenge and continuously treated during infection;

- •

- E26 group—gavaged with H. coagulans BHE26 (5 × 108 CFU/mL, 0.2 mL/day) for 4 weeks without H. pylori challenge.

After overnight fasting, blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000× g for 15 min at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C. Mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the stomachs were removed aseptically. Each stomach was rinsed with sterile PBS (0.01 mol/L, pH 7.4) to remove residual contents, and tissues from the pyloric region were collected. The samples were divided into three parts: one for urease activity assay after homogenization in sterile saline (1:9, w/v), one snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for 16S rRNA sequencing, and one fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin for histological examination.

2.7.2. Urease Activity

Gastric urease activity was determined using a modified phenol-red rapid urease test [34]. Briefly, 50 µL of gastric tissue homogenate was mixed with 150 µL of urease and incubated under microaerophilic conditions for 24 h at 37 °C. A color change from yellow to purple indicated positive urease activity.

2.7.3. Histopathological Analysis of Gastric Tissue and Measurement of Anti-Bacterial-IgG Antibodies in Mouse Serum

Gastric tissues were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 4–6 μm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) for histopathological assessment and with Warthin–Starry silver stain to visualize H. pylori. Slides were examined under a light microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Serum anti-bacterial IgG was measured by ELISA (Cusabio, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

2.7.4. Analysis of Gastric Tissue Microbiota

Biological information was analyzed by targeting the V4 and V5 regions of the mouse gastric tissue using 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing. PCR amplification was performed with the forward primer (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA) and reverse primer (CCGTCAATTCCTTTGAGTTT). Amplicon sequence variant (ASV) noise reduction was applied to process the sequencing data, enhancing the accuracy of the analysis [35]. The validated data were subsequently used for taxonomic annotation and abundance profiling. Sequencing depth and coverage were assessed using rarefaction curves and Good’s coverage index, with most samples exceeding 97% [36]. To investigate variations in community structure across samples, beta-diversity metrics and Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis were employed [37].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test, considering a significance level of p < 0.05, using SPSS 26.0. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anti-Bacterial Activity of H. coagulans BHE26

The growth inhibition assay against H. pylori serves as a key and direct indicator for the screening of probiotics [38]. The fermentation broths and supernatants of Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 exhibited distinct inhibitory effects against H. pylori, with inhibition zone diameters ranging from 12.44 mm to 14.29 mm (Table 1). No inhibition zones were observed for the bacterial suspension of H. coagulans BHE26, similar to the negative control (GMRS ), suggesting that the antibacterial activity may be attributed to extracellular metabolites. The fermentation broth and cell-free supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 produced inhibition zones of 13.19 ± 0.46 mm and 13.76 ± 0.22 mm, respectively (Table 1), indicating that the antibacterial activity is primarily mediated by extracellular metabolites. In agar diffusion assays, inhibition zones in the range of approximately 10–20 mm are generally considered to reflect moderate but biologically relevant antibacterial activity [39]. The inhibition zone diameters observed in the present study (approximately 12–14 mm) are comparable to those reported for other probiotic strains against H. pylori, supporting the biological significance of the antagonistic effects [40,41].

Table 1.

Effects of fermentation broth and supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 on the diameter (mm) of the inhibition zone of H. pylori *.

The absence of inhibition by bacterial suspensions, together with the clear activity of fermentation broths and cell-free supernatants, indicates that secreted antimicrobial compounds mediate the antagonistic effects. Probiotic strains produce extracellular metabolites, including organic acids, antimicrobial peptides, and bacteriocins, which inhibit H. pylori growth and adhesion in vivo. Lyophilized cell-free supernatants of Limosilactobacillus fermentum T0701, containing these secreted compounds, strongly suppressed H. pylori growth and reduced bacterial adhesion to epithelial cells [41]. These extracellular effects correspond with the observed reduction in gastric colonization in vivo.

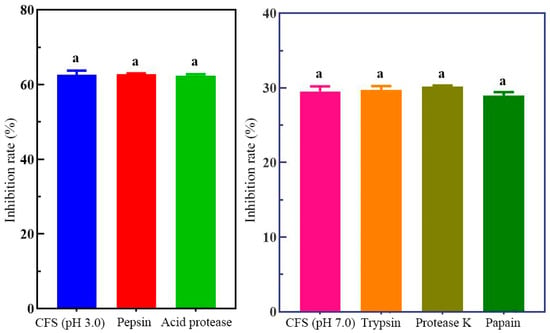

3.2. Analysis of Antimicrobial Components in the CFC

Incubation with acidic proteases (pepsin and acid protease) or neutral proteases (trypsin, proteinase K, and papain) resulted in no significant changes in H. pylori viability compared with the untreated control (p > 0.05) (Figure 1). These results suggest that the inhibitory activity of the cell-free supernatant is not protein-based. HPLC analysis showed that lactic acid was the predominant organic acid in the supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 after 24 h of fermentation (35.8 mmol/L), followed by acetic acid (31.7 mmol/L). The dominance of lactic acid, together with the marked reduction in inhibitory activity after pH neutralization, supports its major role in suppressing H. pylori growth (Figure 2). Lactic acid has been reported to enhance antibacterial effects by suppressing H. pylori urease activity and increasing bacterial membrane permeability [42]. Acetic acid, although present at lower concentrations, may contribute synergistically to inhibition.

Figure 1.

Effect of protease treatment on the antibacterial activity of H. coagulans BHE26 CFS against H. pylori. The CFS was treated with acidic proteases (pepsin and acid protease) or neutral proteases (trypsin, proteinase K, and papain) prior to incubation with H. pylori. The inhibitory effect was expressed as the percentage of H. pylori death, calculated relative to the untreated control. The same letter indicates no significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

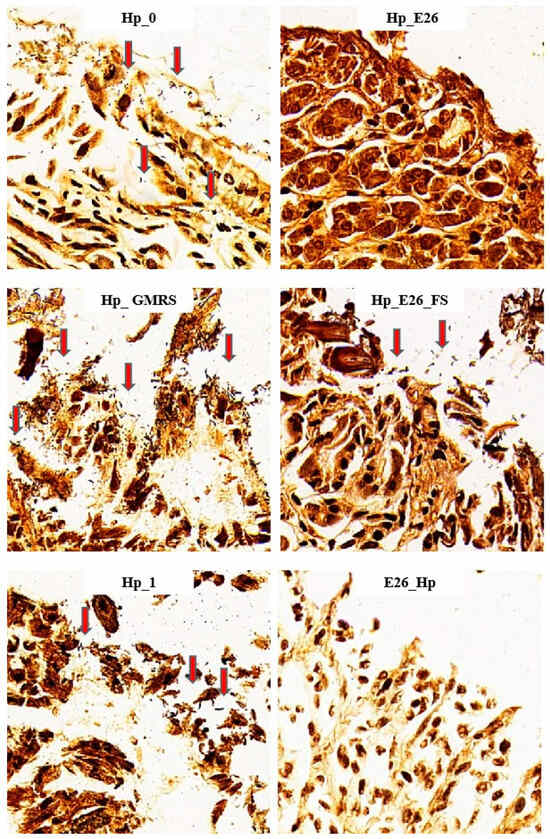

W-S silver staining of gastric tissue sections showing H. pylori (red arrows) at 400× magnification. Hp_0, Hp_E26, Hp_GMRS, Hp_E26_FS, Hp_1, and E26_Hp denote infection control in the therapeutic experiment, H. pylori treatment, therapeutic control, supernatant treatment, infection control in the preventive experiment and prevention group, respectively.

3.3. Tolerance to Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions

The ability of probiotics to survive gastrointestinal transit is a key criterion for exerting beneficial effects on the host. Low pH and bile salts are the initial physiological challenges faced by probiotic strains during gastrointestinal passage [43]. After 3 h of incubation in artificial gastric fluid at pH 3.0, H. coagulans BHE26 exhibited a survival rate of 69.3%, indicating effective tolerance to acidic conditions. Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 (positive control) showed a survival rate of 79.1%. Bile salt tolerance is critical for probiotics in vivo. Bile salts can damage the cell structure, with the extent of damage increasing at higher concentrations. H. coagulans BHE26 exhibited a survival rate of 85.8% after 4 h of incubation in MRS broth with 1% bile salt, indicating its strong tolerance to high bile salt concentrations. Although the physiological bile salt concentration in the human small intestine is approximately 0.3%, 1% was intentionally used to evaluate the strain’s maximum tolerance and robustness under extreme stress [31]. Under the same conditions, L. plantarum CN2018 exhibited a survival rate of 50.1%. Hyronimus et al. found that Bacillus coagulans and B. racemilacticus were unable to survive under such harsh conditions [44]. In contrast, Nithya and Halami reported that B. subtilis Bn1 exhibited tolerance to 0.3% ox-bile, whereas B. flexus Hk1 was susceptible [45]. Overall, these results indicate that H. coagulans BHE26 can withstand acidic pH and high bile salt stress, supporting its potential suitability as a probiotic capable of surviving gastrointestinal transit.

3.4. The Agglutination Activity of H. coagulans BHE26

H. coagulans BHE26 exhibited a hydrophobicity of 45.8%, which was significantly higher than that of the positive control Lactobacillus plantarum CN2018 (21.9%, p < 0.05). However, hydrophobicity alone is not considered a reliable predictor of epithelial adhesion in vivo. Hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation, and co-aggregation represent strain-specific physicochemical traits which are often associated with adhesion potential in vitro [46]. These relationships vary markedly among strains and experimental conditions [46,47]. H. coagulans BHE26 displayed a high auto-aggregation percentage of 68% after 24 h, exceeding CN2018 (61%, p < 0.05). In addition, it demonstrated strong co-aggregation with H. pylori, reaching 64.7% and 79.4% at 24 and 48 h, respectively, which were significantly higher than the corresponding values observed for L. plantarum CN2018 (62.1% and 70.2%, p < 0.05).

Previous studies have reported that specific co-aggregation between probiotics and H. pylori is associated with reduced pathogen adhesion to epithelial surfaces in vitro [40,48]. Co-aggregation can promote physical association between probiotics and H. pylori. Administration of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17648 has been linked to reduced gastric H. pylori burden in vivo [49]. Moreover, clinical trials have demonstrated beneficial adjunctive effects of L. reuteri DSM17648, including reduced H. pylori load and improved treatment tolerability [50]. These findings are consistent with passive removal through aggregate formation as a plausible, strain-specific mechanism, while competitive exclusion and other complementary effects are also likely to contribute.

3.5. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Safety Evaluation

H. coagulans BHE26 was resistant to ceftriaxone but sensitive to penicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, lincomycin, tetracycline and chloramphenicol (Table 2). Certain resistance phenotypes in probiotic genera, including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Bacillus, are intrinsic and non-transferable and therefore do not pose an inherent safety concern in the absence of mobile genetic elements [51]. According to EFSA, only acquired antimicrobial resistance genes carried on mobile genetic elements are considered a relevant safety concern, whereas intrinsic, species-associated resistance is generally not considered a safety concern in the absence of evidence for transferability [51,52]. H. coagulans BHE26 exhibited resistance to ceftriaxone but was susceptible to multiple clinically important antibiotics. The results are consistent with other Bacillus strains showing predominantly intrinsic resistance patterns and broad susceptibility profiles, as evidenced in Bacillus velezensis where potential resistance genes are chromosomally encoded without mobile elements and with broad antibiotic sensitivity [53]. Thus, H. coagulans BHE26’s antibiotic susceptibility profile aligns with current safety evaluation frameworks. To further ensure the safety of the H. coagulans BHE26, a hemolysis assay was performed. H. coagulans BHE26 strain exhibited γ-hemolytic activity (Table 3), indicating it is non-hemolytic and safe.

Table 2.

Antibiotic sensitivity of H. coagulans BHE26.

Table 3.

Hemolytic activity of H. coagulans BHE26.

3.6. Effect of H. coagulans BHE26 on H. pylori-Infected Mice

3.6.1. Urease Activity and W–S Silver Staining Analyses

As shown in Table 4, both the blank control (Con) and the H. coagulans BHE26-only group (E26) were urease-negative, confirming the absence of endogenous H. pylori infection. In the H. pylori model groups, urease positivity ranged from 80% to 100%, whereas daily oral administration of H. coagulans BHE26 markedly reduced urease-positive rates to 30–40% in both the bacterial suspension (Hp_E26) and fermented supernatant (Hp_E26_FS) groups. Notably, preventive pretreatment with H. coagulans BHE26 (E26_Hp) resulted in the lowest urease positivity of 17%. W-S silver staining further corroborated these findings (Figure 2). Abundant brown-black, rod- and spiral-shaped H. pylori cells were observed on the gastric mucosal surface and within glandular lumens in infected control groups, whereas gastric colonization was substantially reduced following H. coagulans BHE26 treatment. The positive staining rates decreased from 80 to 100% in infected controls to 40% (Hp_E26), 50% (Hp_E26_FS), and 25% (E26_Hp), demonstrating a marked suppression of H. pylori colonization. Probiotics have been shown to reduce urease activity and colonization through mechanisms such as growth inhibition and competitive adhesion, while complete bactericidal elimination by probiotics alone is rarely observed [40,54,55]. The dosing regimen, including daily oral gavage and a multi-week treatment period, was consistent with that used in previous studies investigating probiotic interventions against H. pylori. For example, Lactobacillus plantarum ZFM4 and Lacticaseibacillus casei T1 have been administered by daily oral gavage at comparable doses (108–109 CFU per dose) for multiple weeks, resulting in reduced gastric colonization and urease activity without complete eradication of H. pylori [56,57]. The Hp_GMRS group, which received GMRS medium alone as a vehicle control, showed no significant changes in urease activity and bacterial colonization. This indicates that the observed effects were specifically attributable to H. coagulans BHE26 and its fermentation-derived products. These results demonstrate that H. coagulans BHE26 effectively suppresses H. pylori colonization and urease activity in vivo.

Table 4.

Urease activity and W-S silver staining results of gastric tissue in mice.

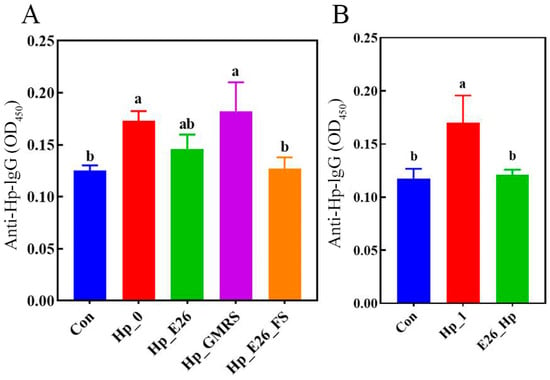

3.6.2. Measurement of Anti-Bacterial-IgG Antibodies in Mouse Serum

In both treatment and prevention groups, serum anti-bacterial IgG levels were significantly higher in the infection controls (Hp_0 and Hp_1) than in the blank control (Con) (Figure 3, p < 0.05). Following probiotic intervention, antibody levels generally declined, except in the Hp_GMRS group, where no significant difference was observed. Notably, the Hp_E26_FS group exhibited a significant reduction in anti-bacterial IgG levels (p < 0.05). These results demonstrate that H. pylori infection was associated with a marked increase in serum antibacterial IgG levels, whereas treatment with H. coagulans BHE26 significantly attenuated this response. This decrease is likely attributable to reduced antigenic stimulation resulting from diminished gastric colonization and alleviated mucosal inflammation, rather than to a direct modulation of humoral immunity [58,59]. This observation aligns with previous study that administration of Lactobacillus strains to H. pylori-infected mice reduces gastric bacterial load and concurrently lowers serum antibody levels [60].

Figure 3.

Levels of anti-bacterial IgG antibodies in mouse serum (A) therapeutic intervention group; (B) prophylactic intervention group. Different letters (a, b) indicate significant differences from each other (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

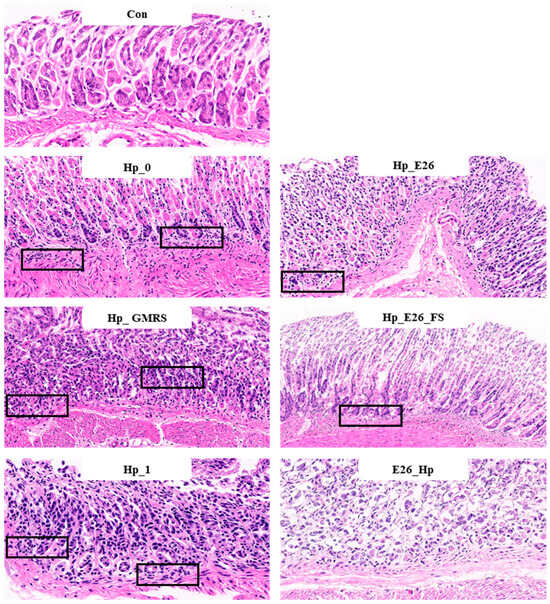

3.6.3. H. coagulans BHE26 Inhibits H. pylori Infection In Vivo

H&E staining revealed that H. pylori infection caused significant disruption of the gastric mucosal architecture, accompanied by extensive infiltration of immune cells (Figure 4). In contrast, mice treated with H. coagulans BHE26 showed preserved gastric structures and markedly reduced inflammatory infiltration. Mild inflammation observed in the control group was attributed to mechanical intragastric administration. Both post-infection (Hp_E26) and pre-infection (E26_Hp) treatments with H. coagulans BHE26 significantly alleviated mucosal inflammation compared to their respective controls (Hp_0 and Hp_1), whereas the GMRS treatment showed no improvement (Figure 4). The fermentation supernatant (Hp_E26_FS) also decreased inflammatory cell infiltration, suggesting that bioactive metabolites from H. coagulans BHE26 contributed to its anti-inflammatory effects (Figure 4). These findings indicate that both the bacterial suspension and fermentation supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 exert protective effects against H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal injury. The anti-inflammatory effect appears to be mediated by reduced H. pylori colonization and urease activity, and enhanced mucosal immune defense [61].

Figure 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of gastric tissue sections at 200× magnification. Black boxes indicate inflammatory cell infiltration. Con, Hp_0, Hp_E26, Hp_GMRS, Hp_E26_FS, Hp_1, and E26_Hp denote blank control group, infection control in the therapeutic experiment, H. pylori treatment, therapeutic control, supernatant treatment, infection control in the preventive experiment and prevention group, respectively.

3.7. Bioinformatic Analysis of Gastric Microbiota

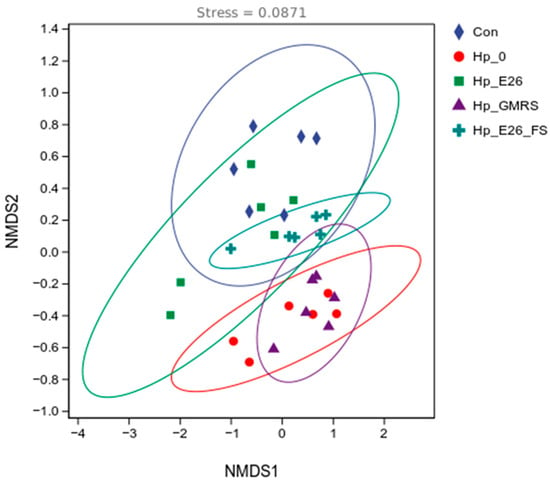

3.7.1. Beta Diversity Analysis

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Jaccard distances revealed clear separation of gastric microbiota among experimental groups (stress = 0.0871; Figure 5). The Hp_0 group clustered distinctly from controls, indicating substantial H. pylori-induced dysbiosis. In contrast, the Hp_E26 group overlapped considerably with controls, suggesting that bacterial suspension intervention effectively attenuated microbial composition toward a healthy state. The Hp_E26_FS and Hp_GMRS groups formed intermediate clusters, with minimal overlap, highlighting differential modulatory effects of bacterial supernatant versus GMRS treatment. Adonis analysis confirmed these observations, showing significant differences between control and Hp_0 groups (p < 0.01) and between Hp_E26 and Hp_0 (p < 0.05), while no significant difference was observed between Hp_E26 and controls (p > 0.05). The Hp_E26_FS and Hp_GMRS groups also differed significantly (p < 0.01), reinforcing that distinct intervention modalities yield divergent effects on the gastric microbial community.

Figure 5.

Beta-diversity analysis. Con, Hp_0, Hp_E26, Hp_GMRS, Hp_E26_FS, denote blank control group, infection control in the therapeutic experiment, H. pylori treatment, therapeutic control, and supernatant treatment, respectively.

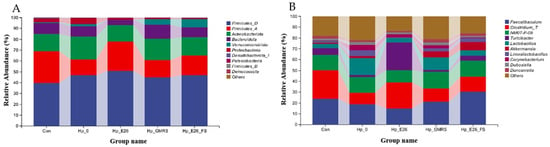

3.7.2. Phylum Level and Genus Level Species Analysis

At the phylum level, the dominant bacterial taxa were similar across all groups (Figure 6A), including Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Proteobacteria, although their relative abundances differed. Compared with the control group, H. pylori infection (Hp_0) resulted in a decrease in Firmicutes and Bacteroidota and an increase in Actinobacteriota. At the genus level, the major bacterial genera included Faecalibaculum, Clostridium_T, Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, Akkermansia, and Dubosiella (Figure 6B). Administration of H. coagulans BHE26 to H. pylori-infected mice enriched gastric Limosilactobacillus and Dubosiella, indicating functional microbiota modulation under dysbiosis rather than contamination [62]. Probiotics may suppress H. pylori via competitive exclusion, modulation of microbial metabolites, and attenuation of mucosal inflammation [62,63]. These microbial shifts coincided with significant reductions in gastric H. pylori colonization and serum anti-H. pylori IgG levels, supporting a contributory role of microbiota remodeling in pathogen suppression.

Figure 6.

Histogram of relative abundance of gastric microbiota at phylum level (A) and genus level (B). Con, Hp_0, Hp_E26, Hp_GMRS, Hp_E26_FS, denote blank control group, infection control in the therapeutic experiment, H. pylori treatment, therapeutic control, and supernatant treatment, respectively.

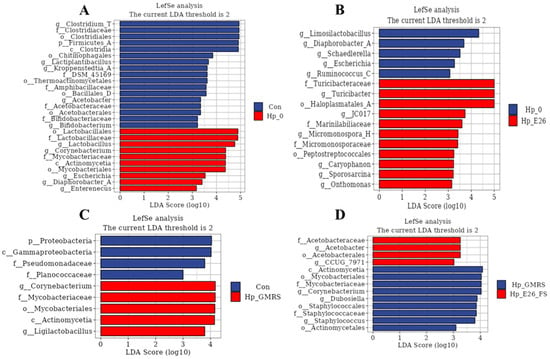

3.7.3. Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) Analysis

LEfSe analysis revealed that H. pylori infection significantly reshaped the gastric microbiota in mice. Compared with the control group, the Hp_0 group showed enrichment of Lactobacillales, Corynebacterium, Actinobacteria, and Mycobacteriales, along with a reduction in Clostridia and Firmicutes_A (LDA score > 4; Figure 7A). The Hp_E26 group was characterized by increased Turicibacter and Haloplasmatales_A, while Lactobacillus abundance decreased relative to Hp_0 (LDA score > 4; Figure 7B). Reduced Lactobacillus abundance has been frequently reported in H. pylori-infected hosts, as specific Lactobacillus strains can inhibit H. pylori growth or adhesion through organic acid production and competitive exclusion [64,65]. An increased abundance of Turicibacter was also detected in Hp_E26 group (Figure 7B). Turicibacter strains are associated with host bile acid profiles and lipid metabolism [66]. The enrichment of Turicibacter observed in this study is interpreted as a community-level shift reflecting altered host or environmental conditions. In addition, the Hp_E26_FS group exhibited lower levels of Actinobacteria, Mycobacteriales, and Corynebacterium than the Hp_GMRS group (LDA score > 4; Figure 7D). H. pylori infection induced gastric dysbiosis by disrupting microbial balance, whereas treatment with the bacterial suspension or supernatant of H. coagulans BHE26 effectively alleviated these alterations, restoring the microbiota toward a composition resembling that of healthy controls. Probiotic interventions can remodel the gastric microbiota and counteract H. pylori-mediated dysbiosis [67].

Figure 7.

LEfSe multi-level taxonomic analysis of gastric microbiota. (A) Differentially abundant taxa between the Con and Hp-0 groups. (B) Differentially abundant taxa between the Hp-0 and Hp-E26 groups. (C) Differentially abundant taxa between the Con and Hp-GMRS groups. (D) Differentially abundant taxa between the Hp-GMRS and Hp-E26-FS groups. Con, Hp-0, Hp-E26, Hp-GMRS, Hp-E26-FS denote blank control group, infection control group, therapeutic group 1, therapeutic control group, therapeutic group 2, respectively.

4. Conclusions

This study aimed to systematically evaluate the potential of H. coagulans BHE26 against H. pylori in vitro and in vivo. H. coagulans BHE26 directly inhibited H. pylori growth in vitro. It expressed remarkable hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation and co-aggregation ability. In the H. pylori-infected mouse model, administration of H. coagulans BHE26 significantly reduced H. pylori colonization and urease activity, as well as serum H. pylori-specific IgG levels. Moreover, this strain effectively modulated the composition of the gastric microbiota toward a healthier profile, suggesting its role in supporting gastric microbial homeostasis. These findings indicate that H. coagulans BHE26 exhibits promising probiotic potential and may be considered for future application in functional food industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W. and C.D.; methodology, N.W.; software, J.G.; validation, N.W. and J.G.; formal analysis, J.G.; investigation, D.Z.; resources, L.D.; data curation, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W.; writing—review and editing, C.D.; visualization, Z.H. and Z.R.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, N.W.; funding acquisition, C.D.; supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research Projects of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (grant number: 25B550009), the Doctor Research Fund of the Henan University of Technology (grant number: 2023BS086), the Postdoctoral Scientific Research Fund of Henan University of Technology (grant number: 21450081), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (Youth Program, grant number: 252300423564), the Food Engineering Technology Research Center/Key Laboratory of Henan Province, Henan University of Technology (grant number: GO202503), the Open Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology and Breeding (grant number: 20240206), the Cultivation Project of Tuoxin Team in Henan University of Technology (grant number: 2024TXTD07), the Double First-Class Undergraduate Innovation Program of Henan University of Technology (grant number: HN-HautFood IAEG-019), and the Key Scientific and Technological Project in Henan Province (grant number: 242102111052).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines established by the Welfare and Ethics Review Committee of Zhengzhou University Laboratory Animal Center (approval number: ZZU-LAC20211015[15], approval date: 12 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Lingguang Du, Dongge Zheng and Zhihui Hao were employed by the Zhengzhou Jinbaihe Biological Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Malfertheiner, P.; Camargo, M.C.; El-Omar, E.; Liou, J.M.; Peek, R.; Schulz, C.; Smith, S.I.; Suerbaum, S. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ruan, X.; Hang, X.; Heng, D.; Cai, C.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, L.; Bi, H.; Zhang, L. Antagonist targeting the species-specific fatty acid dehydrogenase/isomerase fabx for anti-H. pylori infection. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2414844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, J.K.Y.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; Graham, D.Y.; Wong, V.W.S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, Z.; Li, W.; Deng, X.; Yu, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, W.; Guo, X.; et al. Weizmannia coagulans BCF-01: A novel gastrogenic probiotic for Helicobacter pylori infection control. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2313770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavros, Y.; Merchant, J.L. The immune microenvironment in gastric adenocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leja, M.; Grinberga-Derica, I.; Bilgilier, C.; Steininger, C. Review: Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Peng, F.; Huang, H.; Xu, X.; Guan, Q.; Xie, M.; Xiong, T. Characterization, mechanism and in vivo validation of Helicobacter pylori antagonism by probiotics screened from infants’ feces and oral cavity. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 1170–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhai, S.; Wang, C.; Bai, Z.; Tian, P.; Tie, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gu, S. Weizmannia coagulans BC99 modulate gut microbiota after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 125, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.M.; Lee, Y.C.; Wu, M.S. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection and its long-term impacts on gut microbiota. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, H.; Su, J.; Zhang, C.; Huang, L. Modulation of gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function during alleviation of antibiotic-associated diarrhea with Rhizoma Zingiber officinale (Ginger) extract. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10839–10851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gao, H.; Miao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Li, F.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in humans and phytotherapy, probiotics, and emerging therapeutic interventions: A review. Front Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1330029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Zhu, M.; He, Y.; Wang, T.; Tian, D.; Shu, J. The impacts of probiotics in eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Feng, C.; Jia, P.; Yan, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, N.; Chen, W.; Gao, W. Effect of Clostridium butyricum and Bacillus coagulans on fecal and serum metabolic profiles in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 130, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.D.; Su, C.H.; Hsu, Y.M. Antagonistic activities of Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB3 against Helicobacter pylori infection through lipid raft formation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 796177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallone, C.A.; Chiba, N.; van Zanten, S.V.; Fischbach, L.; Gisbert, J.P.; Hunt, R.H.; Jones, N.L.; Render, C.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Moayyedi, P.; et al. The toronto consensus for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; Rokkas, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Liou, J.M.; Schulz, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Hunt, R.H.; Leja, M.; O’Morain, C.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: The Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut 2022, 71, 1724–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugano, K.; Tack, J.; Kuipers, E.J.; Graham, D.Y.; El-Omar, E.M.; Miura, S.; Haruma, K.; Asaka, M.; Uemura, N.; Malfertheiner, P. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut 2015, 64, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.S.; Dubhashi, A.V. In-vitro transit tolerance of probiotic Bacillus species in human gastrointestinal tract. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 1899–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuray, G.; Erginkaya, Z. Potential use of Bacillus coagulans in the food industry. Foods 2018, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresca, E.; Aulitto, M.; Contursi, P. Harnessing the dual nature of Bacillus (Weizmannia) coagulans for Sustainable production of biomaterials and development of functional food. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Moon, J.S.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, D.; Choi, H.S.; Oh, I. Blending three probiotics alleviates loperamide-induced constipation in sprague-dawley (sd)-rats. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, S.; Fijan, T.; Connil, N. Overview of probiotic strains of Weizmannia coagulans, previously known as bacillus coagulans, as food supplements and their use in human health. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, Y.; Gai, Z.; Wu, Y.; Fang, S.; Gu, S. Weizmannia coagulans BC99 relieves constipation symptoms by regulating inflammatory, neurotransmitter, and lipid metabolic pathways: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Foods 2025, 14, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhai, S.; Duan, M.; Cao, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gu, S. Weizmannia coagulans BC99 enhances intestinal barrier function by modulating butyrate formation to alleviate acute alcohol intoxication in rats. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Fan, Y.; Liu, T.; Peng, N. Bacillus coagulans in combination with chitooligosaccharides regulates gut microbiota and ameliorates the DSS-induced colitis in mice. Microbiol. Spectrum. 2022, 10, e0064122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tian, F.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. In vitro screening of lactobacilli with antagonistic activity against Helicobacter pylori from traditionally fermented foods. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 5627–5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.H.; Fan, X.; Gao, J.; Zheng, D.G.; Du, L.G.; Hao, Z.H.; Ma, Y.X.; Wang, S.S. Screening of Haiendrix coagulans with antagonistic effect on Helicobacter pylori and its application in fermented milk. J. Henan Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 46, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Carrión, C.; Espinoza-Monje, M.; Gutiérrez-Zamorano, C.; Sánchez-Alonzo, K.; Carvajal, R.I.; Rogel-Castillo, C.; Sáez-Carrillo, K.; García-Cancino, A. Incorporation of Limosilactobacillus fermentum UCO-979C with anti-Helicobacter pylori and immunomodulatory activities in various ice cream bases. Foods 2022, 11, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Evaluation of gastrointestinal tolerance and regulation of immune-related genes of Lactobacillus reuteri J1 in vitro. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2019, 40, 101–106,113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angmo, K.; Kumari, A.; Bhalla, T.C. Probiotic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods and beverage of Ladakh. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, L.; Gueimonde, M.; Sánchez, B.; Margolles, A.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. Effect of the adaptation to high bile salts concentrations on glycosidic activity, survival at low pH and cross-resistance to bile salts in Bifidobacterium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, H.C.; de Sousa Melo, D.; Ramos, C.L.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Probiotic properties of Lactobacilli and their ability to inhibit the adhesion of enteropathogenic bacteria to Caco-2 and HT-29 Cells. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Peng, F.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, Z.G.; Xie, M.Y.; Xiong, T. Isolation and characteristics of lactic acid bacteria with antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P.; Wilson, J.; Lee, A. Further development of the Helicobacter pylori mouse vaccination model. Vaccine 2000, 18, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shao, D.; Zhou, J.; Gu, J.; Qin, J.; Chen, W.; Wei, W. Signatures within esophageal microbiota with progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 32, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.S.; Soliman, M.S.; Elhossary, W.; El-Kholy, A.A. Analysis of gastric mucosa-associated microbiota in functional dyspepsia using 16S rRNA gene next-generation sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. Disease managing capacities and mechanisms of host effects of lactic acid bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1365–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chornchoem, P.; Tandhavanant, S.; Saiprom, N.; Preechanukul, A.; Thongchompoo, N.; Sensorn, I.; Chantratita, W.; Chantratita, N. Metagenomic evaluation, antimicrobial activities, and immune stimulation of probiotics from dietary supplements and dairy products. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Huo, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhang, C. Screening probiotics for Anti-Helicobacter pylori and investigating the effect of probiotics on patients with Helicobacter pylori Infection. Foods 2024, 13, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornsenee, P.; Surachat, K.; Wong, T.; Kaewdech, A.; Saki, M.; Romyasamit, C. Lyophilized cell-free supernatants of Limosilactobacillus fermentum T0701 exhibited antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, P.X.; Fang, H.Y.; Yang, H.B.; Tien, N.Y.; Wang, M.C.; Wu, J.J. Lactobacillus pentosus strain LPS16 produces lactic acid, inhibiting multidrug-resistant Helicobacter pylori. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2016, 49, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sui, L.; Mu, G.; Zhu, X.; Qian, F. Screening of potential probiotics with anti-Helicobacter pylori activity from infant feces through principal component analysis. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyronimus, B.; Le Marrec, C.; Sassi, A.H.; Deschamps, A. Acid and bile tolerance of spore-forming lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 61, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, V.; Halami, P.M. Evaluation of the probiotic characteristics of Bacillus species isolated from different food sources. Ann. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantanawilas, P.; Pahumunto, N.; Teanpaisan, R. Aggregation and adhesion ability of various probiotic strains and Candida species: An in vitro study. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 2163–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.F.; Yu, H.L.; Ai, L.Z.; Wu, Z.J.; Guo, B.H.; Chen, W. Aggregation and adhesion properties of 22 Lactobacillus strains. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 4252–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntarachot, N.; Sunpaweravong, S.; Kaewdech, A.; Wongsuwanlert, M.; Ruangsri, P.; Pahumunto, N.; Teanpaisan, R. Characterization of adhesion, anti-adhesion, co-aggregation, and hydrophobicity of Helicobacter pylori and probiotic strains. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holz, C.; Busjahn, A.; Mehling, H.; Arya, S.; Boettner, M.; Habibi, H.; Lang, C. Significant reduction in Helicobacter pylori load in humans with non-viable Lactobacillus reuteri DSM17648: A pilot study. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2014, 7, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.I.; Nawawi, K.N.M.; Hsin, D.C.C.; Hao, K.W.; Mahmood, N.R.K.N.; Chearn, G.L.C.; Wong, Z.; Tamil, A.M.; Joseph, H.; Raja Ali, R.A. Probiotic containing Limosilactobacillus reuteri DSM 17648 as an adjunct treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e13017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Teng, D.; Mao, R.Y.; Hao, Y.; Wang, X.M.; Wang, J.H. A critical review of antibiotic resistance in probiotic bacteria. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards). Statement on how to interpret the QPS qualification on ‘acquired antimicrobial resistance genes’. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, G.; Kong, H.; Kim, N.; Lee, S.; Sul, S.; Jeong, D.-W.; Lee, J.-H. Antibiotic susceptibility of Bacillus velezensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auclair-Ouellet, N.; Tremblay, A.; Kassem, O.; Caballero-Calero, S.E.; Bronner, S.; Binda, S. Probiotics as adjuvants to standard Helicobacter pylori treatment: Evidence for the use of Lacidofil®, an established blend of thoroughly characterized strains. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadvar, N.; Akrami, S.; Mousavi Sagharchi, S.-M.-A.; Askandar, R.H.; Merati, A.; Aghayari, M.; Kaviani, N.; Afkhami, H.; Kashfi, M. A review for non-antibiotic treatment of Helicobacter pylori: New insight. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1379209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.Y.; Wu, L.Y.; Sun, X.; Gu, Q.; Zhou, Q.Q. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum ZFM4 in Helicobacter pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice: Prevention is better than cure. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 13, 1320819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.H.; Cao, M.; Peng, J.S.; Wu, D.Y.; Li, S.; Wu, C.M.; Qing, L.T.; Zhang, A.D.; Wang, W.J.; Huang, M.; et al. Lacticaseibacillus casei T1 attenuates Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and gut microbiota disorders in mice. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Han, M.; Qi, Y.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Z.P.; Jiang, D.C.; Gai, Z.H. Enhancement of host defense against Helicobacter pylori infection through modulation of the gastrointestinal microenvironment by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lp05. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1469885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.S.; Lee, H.A.; Kim, J.Y.; Jeong, J.W.; Shim, J.J.; Lee, J.L.; Sim, J.H.; Chung, Y.; Kim, O. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by Lactobacillus paracasei HP7. Lab. Anim. Res. 2018, 34, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouras, D.; Maragkoudakis, P.; Petraki, K.; Martinez-Gonzalez, B.; Eriotou, E.; Michopoulos, S.; Kalantzopoulos, G.; Tsakalidou, E.; Mentis, A. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Q.; Ren, F.F.; Qin, H.M.; Bukhari, I.; Yang, J.; Gao, D.F.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Lehtinen, M.J.; Zheng, P.Y.; Mi, Y. Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lp-115 inhibit Helicobacter pylori colonization and gastric inflammation in a murine model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1196084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Peng, C.; Xu, X.B.; Li, N.S.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, N.H. Probiotics mitigate Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and premalignant lesions in INS-GAS mice with the modulation of gastrointestinal microbiota. Helicobacter 2022, 27, e12898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikha, M.; Karbalaei, M. Probiotics as the live microscopic fighters against Helicobacter pylori gastric infections. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.; Anwar, M.T.; Linz, B.; Backert, S.; Pachathundikandi, S.K. The Influence of Gastric Microbiota and Probiotics in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Associated Diseases. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.-F.; Tian, D.; Wang, T.-Y.; Shu, J.-C.; He, Y.-J.; Zhu, M.-J. The impact of probiotics on gut microbiota in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 6736–6743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.B.; Gonzalez, E.L.; Choy, K.; Faull, K.F.; Jewell, T.; Arellano, A.; Liang, J.; Yu, K.B.; Paramo, J.; Hsiao, E.Y. Gut microbiota Turicibacter strains differentially modify bile acids and host lipids. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.X.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Li, P.; Wu, S.Y.; Zhou, T.; Gu, Q. Exopolysaccharide from Lacticaseibacillus paracasei alleviates gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice by regulating gastric microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1426358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.