Abstract

The global food supply is increasingly challenged by toxicologically relevant natural and synthetic chemicals, including mycotoxins, pesticides, heavy metals, and migrants from food packaging. Conventional physical and chemical detoxification approaches can reduce contaminant loads but may compromise nutritional and sensory quality or leave residues, motivating a shift toward biological strategies. This review synthesizes current evidence on Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii, a clinically established probiotic yeast, as a multifaceted biological detoxification agent in foods. We outline its dual modes of action: (i) rapid, reversible adsorption of contaminants mediated by the architecture of the yeast cell wall (β glucans, mannans, chitin), and (ii) active biotransformation through secreted proteins and enzymes. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii has been reported to remove up to 96.9% of aflatoxin M1 in reconstituted milk, depending on strain, dose, contact time, pH, and matrix effects. We collate findings for other contaminant classes and highlight practical variables that govern efficacy, while comparing detoxification performance with bacterial probiotics and conventional methods. Critical knowledge gaps were highlighted, including standardized testing protocols, mechanistic resolution of adsorption versus degradation, stability and regeneration of binding capacity, sensory impacts, with scale up and regulatory pathways. A roadmap is proposed to harmonize methods and unlock the full potential of this promising biotherapeutic yeast for food safety applications.

1. Introduction

Foodborne chemical contaminants from environmental sources, processing operations, and packaging materials pose continuing risks to consumer health [1,2,3]. Their adverse effects including oxidative stress, inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and intestinal disturbances underscore the need for effective mitigation strategies [4,5]. Although physical and chemical detoxification methods are widely used, these approaches may compromise nutritional or sensory quality or leave undesirable residues [6,7]. To address these limitations, interest has grown in biological strategies employing probiotic microorganisms as safer and more sustainable alternatives in food systems [5,8,9]. When administered in adequate amounts, they benefit health to support microbiota homeostasis, strengthen intestinal barrier, and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines [10,11,12]. Recent research has increasingly emphasized the capacity of specific microorganisms, particularly yeasts, to mitigate foodborne contaminants. Several strains reduce chemical contaminants through adsorption to cell-wall components or through enzymatic biotransformation, with efficacy depending on the contaminant type, strain characteristics, and food matrix conditions [1,13,14,15]. For example, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae show strong adsorption of aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) in ultra-high temperature (UHT) milk [16], and patulin removal by S. cerevisiae depends on cell-wall β-1,3-glucan composition [17]. A LAB–yeast consortium (Lactobacillus rhamnosus + S. cerevisiae) has achieved up to 98.4% AFM1 detoxification in milk [18].

Within this context, Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii has emerged as a uniquely promising probiotic yeast due to its dual relevance in human health and food applications. While bacteria such as Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lacticaseibacillus casei, and species of Bifidobacterium (e.g., B. bifidum, B. lactis, B. longum, B. thermophilum) remain dominant in commercial probiotics [12,19,20], S. cerevisiae var. boulardii stands out for its robust survival, therapeutic properties, and detoxification potential. It has been effectively used to manage intestinal diseases [20], demonstrates high cell viability in fermented beverages [21], and exhibits notable capacity to reduce contaminants in dairy matrices [22,23]. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii was first isolated from lychee and mangosteen fruit peels by Henri Boulard, who observed that traditional fruit infusions alleviated cholera symptoms during an outbreak [24]. Since then, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii has been widely used in the treatment of intestinal diseases and is considered one of the main probiotic microorganisms in the pharmaceutical and food industry [24,25]. Despite being taxonomically classified within S. cerevisiae, it differs markedly in physiology and stress tolerance. Its optimal growth at 37 °C, enhanced acid resistance, and distinct metabolic traits set it apart from conventional S. cerevisiae strains and reinforce its efficiency as both a probiotic and a decontaminant [26,27]. Table 1 summarizes the distinguishing features supporting its unique functional role.

Table 1.

Physiological and genetic distinctions between Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii and S. cerevisiae.

Critical physiological and genetic differences between S. cerevisiae var. boulardii and S. cerevisiae strains (Table 1) help explain its superior performance as a probiotic and its emerging role in contaminant detoxification. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii exhibits optimal growth at 37 °C and shows enhanced survival under simulated gastric conditions (pH ≤ 2) and in the presence of bile salts, supporting its persistence during gastrointestinal transit and in acidic food matrices. Additional copies of FLO genes and associated flocculation capacity promote adhesion to microbial cells and contaminants, improving toxin binding and removal. Variations in cell-wall composition and stress-response gene dosage further contribute to environmental resilience and influence adsorption behavior. The lack of sporulation reduces spoilage risks in food applications, while differences in carbohydrate utilization including the inability to metabolize galactose remain relevant for selecting strains for specific fermentation processes [28,29,30].

To confer probiotic benefits, microorganisms must survive gastrointestinal transit and act beneficially within the host. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii influences multiple intestinal processes. It exerts anti-inflammatory activity by promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines and stimulating immunoglobulin A production. It also competes with pathogens for receptor binding sites, suppresses virulence traits, maintains epithelial integrity, and inhibits Candida albicans filamentation and biofilm formation [31,32]. Furthermore, it reduces adherence and invasion by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC), protecting tight-junction proteins [26,33,34]. As a non-colonizing, transient yeast, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii competes effectively for nutrients and adhesion sites, promoting the removal of pathogens through its expanded flocculin repertoire [35,36,37]. These mechanisms complement adsorption and biotransformation processes, expanding its relevance to contaminant detoxification. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii also secretes digestive enzymes and proteins capable of binding toxins and modulates the synthesis of short- and branched-chain fatty acids [24,37,38,39,40,41]. Given its distinctive physiological attributes and growing relevance in food processing, a focused assessment of its roles in detoxifying chemical contaminants is warranted.

Accordingly, this review synthesizes current knowledge on the capacity of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii to bind, transform, and mitigate foodborne chemical contaminants. We examine its biological mechanisms, summarize evidence across contaminant classes and food matrices or study type (in vitro/animal), and highlight key research gaps and future directions for translating this yeast into practical food-industry applications.

2. Overview of Food Contaminants Assessed for Detoxification by S. cerevisiae var. boulardii

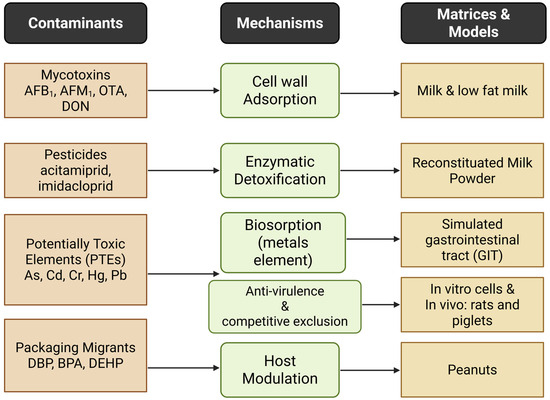

Figure 1 provides a visual overview linking the contaminant classes covered in this study to the major detoxification mechanisms and the matrices/models most frequently investigated.

Figure 1.

Major contaminant types with the detoxification mechanisms in the commonly used food matrices or experimental models.

2.1. Mycotoxins

Several common and toxicologically relevant food contaminants occur in nature. Among them, mycotoxins are toxic compounds originating from the secondary metabolism of some fungal species such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Alternaria. In terms of occurrence in food, the main ones responsible for toxicity include aflatoxins (AF), ochratoxin A (OTA), patulin (PAT), fumonisins (FBs), deoxynivalenol (DON), zearalenone (ZEN), and others [42]. The production of these mycotoxins can occur at different stages of the food production chain; however, they are most frequently found under field conditions or during improper storage of grains and feed [9]. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that mycotoxins contaminate more than 25% of the world’s cereal crops, with some reports suggesting this figure could be as high as 60% to 80% [43]. Mycotoxins can be found naturally in a variety of food products, including fruits, rice, beans, corn, peanuts, wheat, barley, spices, and milk, among others, causing significant damage to crops [44,45]. The health and economic implications of this contamination are profound [46]; as a consequence, humans and animals are directly exposed to mycotoxin toxicity upon consumption of contaminated food. The toxic effects depend mainly on the type, concentration, and exposure time of each mycotoxin. Most of these contaminants can cause hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, neurotoxicity, immunosuppression, and carcinogenicity and are therefore considered a global public health problem [45,47]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has categorized AFB1 as a Group 1 human carcinogen, while FBs and OTA are classified as Group 2B human carcinogens [48]. Furthermore, the prevalence of masked mycotoxins that evade conventional detection methodologies is an emerging concern in the field of food safety.

2.2. Pesticides

Insecticides are a type of pesticide used to control pests in crops and restrict the invasion of insects, weeds, and others that adversely affect plant growth. Pesticides are primarily used to enhance crop production and prevent disease; however, their widespread use makes them one of the major chemical contaminants to which living beings are exposed [49]. The transfer of certain pesticide classes, such as neonicotinoids, to food indicates their potential to harm human health due to their systemic ability to penetrate plant tissues and accumulate in edible parts [50,51]. Diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, reproductive disorders, chronic respiratory diseases, and different types of cancer are associated with exposure to pesticides [52]. The use of pesticides in agricultural production is essential to meet industrial needs and global food security, but their use also promotes high health risks for the environment and living beings [49]. The acute toxicity caused by pesticides is associated with their inhalation, ingestion, and direct contact with eyes or skin. In contrast, long-term exposure can cause chronic toxicity such as neurotoxicity, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, and endocrine disturbance [53].

2.3. Packaging Migrants (Phthalates and Bisphenol A)

Phthalates and bisphenol A are chemicals widely used in the manufacture of plastics, ranging from beverage and food containers to medical devices [54]. Food is the most common form of exposure to these constituents due to their potential to leach into food. Leaching from plastic materials is facilitated by several degradation processes, including chemical, physical, biological, or photodegradation. Factors including heat and ultraviolet exposure, mechanical stress, or microbial processes weaken the polymer structure, allowing these chemicals to migrate into the surroundings [55]. These chemicals are considered endocrine disruptors, as they can interfere with hormone function and also cause developmental and reproductive disorders [56]. The harmful effects of these contaminants are due to their high lipophilicity, which facilitates absorption by different routes and accumulation in tissues [57]. Chronic exposure to these chemical components has been associated with adverse health effects, including developmental issues from pregnancy to adulthood, alterations in the nervous system and brain, and increased vulnerability to breast and liver cancer [58].

2.4. Potentially Toxic Elements

Potentially toxic elements (PTE), another class of non-biodegradable pollutants, also pose a significant health risk. They are naturally present in the earth’s crust, but with increasing urbanization and industrialization, the probability of their accumulation in the environment has increased extensively [59]. Consequently, human exposure to PTE occurs through several routes, including inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact, as well as direct consumption of crops irrigated with contaminated water [60]. Similarly, plants readily absorb PTE, which can bioaccumulate in their tissues and be transferred through the food web, increasing exposure to humans and animals [51,61]. This exposure is alarming due to their persistent, nondegradable, and toxic nature, even at low concentrations. Excessive involuntary exposure to PTE in the food chain is due to the presence of these compounds in water, air, and soil. The high toxicity of these PTE, even at low concentrations, makes them a major threat to food safety and human health [62]. PTE such as mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic cause serious damage to public health. Depending on exposure time, individual sensitivity, and metal type, exposure is linked to several harmful consequences, including immune system dysfunction, neurological diseases, skin lesions, liver disease, and kidney cancer [63,64].

3. Detoxification of Food Contaminants by S. cerevisiae var. boulardii

Chemical food contamination leads to significant food losses, reduces the value of food products, and poses substantial risks to human health [65]. The widespread and persistent nature of these contaminants, coupled with the limitations of existing physical and chemical detoxification methods, emphasize a substantial need for a new, more sustainable approach to food safety. The use of microorganisms to detoxify xenobiotics in food has been highlighted, and probiotic bacteria and yeasts have been shown to be effective in their ability to bind chemical compounds [14]. It has also been shown that probiotics during intestinal transit can inhibit absorption, leading to a decrease in the availability of toxic compounds to the body. Likewise, they can decrease the poisonous capacity of these compounds through binding or altering their structural integrity and facilitate their excretion [1,66,67]. Yeasts adsorb toxic compounds through the surface of their cell walls, and both viable and non-viable cells have a high capacity for reducing toxins in food and feed. The different compositions of the yeast cell wall give rise to considerable variation in their ability to adsorb toxic components [13,68]. In bacteria, the cell wall structure is composed of proteins, teichoic acids, peptidoglycans, and polysaccharides, which serve as binding sites. In the presence of chemical compounds that have negatively charged groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and phosphoryl, they are able to bind to the bacterial surface [14,17,69]. Rapid adsorption via mannans/β-glucans/chitin is a shared feature of Saccharomyces spp., and is therefore not unique to S. cerevisiae var. boulardii. Reported differences in β-glucan content, mannoprotein patterns, surface charge, and flocculation phenotypes can, however, create strain-specific performance alterations across S. cerevisiae and S. boulardii [70,71]. Compared with LAB, which possess peptidoglycan/teichoic-acid-rich cell walls and acidify the medium, S. cerevisiae var. bouvardias offers robust tolerance to low pH and bile, and sustained viability at ~37 °C, making it suitable for co-ingestion scenarios [72]. For pre-consumption applications in foods where yeast growth is undesirable (e.g., fresh dairy), heat-inactivated cells or purified cell-wall fractions of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii and/or LAB adjuncts may be preferable. Organism choice should be guided by contaminant class, matrix, and process constraints.

3.1. Mechanisms of Detoxification

S. cerevisiae var. boulardii counters toxins through several biochemical routes. Initially, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii secretes a serine protease that cleaves toxin molecules and prevents their engagement with epithelial receptors, thereby neutralizing their effects [37,73]. It also modulates host immunity by dampening toxin triggered inflammatory signaling cascades and by promoting production of specific anti toxin IgA [74,75]. Under certain conditions, the yeast produces acetic acid, lowering gut pH and inhibiting many harmful microorganisms and their toxins [37,72]. The secreted protease, together with other factors, can bind toxins or alter the epithelial surface so that receptor binding is hindered [76,77]. By blunting toxin action and inflammation, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii helps preserve tight junctions and overall barrier integrity, reducing fluid leakage into the intestinal lumen [77,78]. In addition, it may directly interfere with pathogen physiology by competing for substrates, modifying the local environment, or perturbing bacterial processes [75].

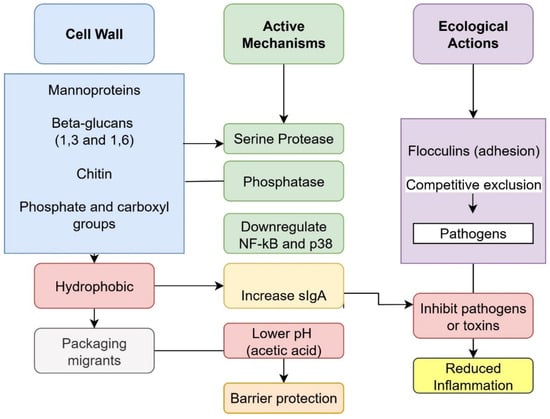

S. cerevisiae var. boulardii acts through more than one route in food detoxification, combining passive binding with enzymatic activity and pathogen antagonism [29]. A well-documented route is adsorption of contaminants to the yeast cell wall. The mechanisms of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii in food detoxification is described in Figure 2. This pathway contributes substantially to the removal of mycotoxins and some PTE. The cell wall’s mannans and β-1,3/β-1,6 glucans overlaying chitin expose phosphate/carboxyl groups and hydrophobic domains that engage planar aromatics and coordinate cations [70,79]. Binding of mycotoxins to yeast cell walls lowers absorption and toxicity [13,68]. Illustrative findings include high binding of total aflatoxins by viable S. cerevisiae (74.7%) and removal of ochratoxin A by S. cerevisiae var. boulardii up to 44% under simulated gastrointestinal conditions [80,81]. In reconstituted milk, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii achieved 96.88% removal of AFM1 at 37 °C, outperforming other probiotic strains [82]. Because adsorption depends on wall integrity and composition [13], binding can be reversible; toxins may desorb if not eliminated promptly, such as through regular bowel movements [83]. For industrial applications, this indicates that adsorption alone may require stabilization approaches or efficient separation steps. To improve stability and enable reuse, disrupted cell-wall fractions of S. cerevisiae and L. rhamnosus were immobilized onto nano-silica and subsequently entrapped within alginate beads. This combined disruption and immobilization significantly enhanced AFM1 removal, with reductions ranging from 53% for free cell-wall fractions (15 min) to 87% for alginate-entrapped adsorbents (24 h). Moreover, the immobilized beads were reusable, maintaining around 85% adsorption efficacy [84].

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii in food detoxification.

Yeast cell walls present functional groups that can bind metal ions and support biosorption [85]. Using yeast biomass as a sorbent is attractive economically because it can be sourced as an industrial byproduct [86]. Performance, however, appears strain specific. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa shows high tolerance and removal for Hg, Cu, and Pb, whereas planktonic S. boulardii tends to tolerate only Pb and forms weak biofilms—a trait that can limit metal capture [87]. These contrasts underscore a knowledge gap and argue against a one size fits all approach [88]. A finer grained understanding of cell wall–metal interactions could guide strategies to strengthen binding, from genetic tuning to combining S. cerevisiae var. boulardii with complementary binders [89]. Beyond adsorption, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii secretes enzymes that directly inactivate toxins. The 54 kDa serine protease (ysp3) hydrolyzes and neutralizes Clostridioides difficile toxins A and B [37,90], and a 63 kDa phosphatase (pho8) can inactivate E. coli endotoxin [91]. In models of DON exposure, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii reversed toxin induced transcriptomic changes and attenuated NF κB and p38 MAPK signaling [92]. Taken together, these findings indicate protection that extends beyond toxin removal to restoration of host pathways, offering a more complete detoxification strategy than adsorption alone [75,93]. The mechanistic diversity of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii aligns with different application formats: adsorption and biosorption support the use of inactivated cells or isolated cell-wall fractions in foods, whereas enzymatic and host-modulatory activities favor co-ingestion of viable cells. Reported process parameters such as dose, contact time, and pH or formulation correlate with the highest contaminant removals in dairy matrices (e.g., AFM1 reductions of up to 96.88% at ~37 °C within 90 min) and with encapsulated preparations in simulated gastrointestinal tract systems for AFB1, as discussed previously [82] and summarized in Table 2. Because adsorption-based binding is reversible, industrial applications should incorporate stabilization strategies (e.g., immobilization) or efficient separation steps to minimize desorption.

Table 2.

Applications of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii in for detoxification of food contaminants.

3.2. Applications of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii for Detoxification of Food Contaminants

The studies to date span multiple contaminants and matrices. Table 2 summarizes conditions, doses, and outcomes reported for S. cerevisiae var. boulardii. The detoxification of chemical contaminants in food depends on several factors, including contaminant concentration, incubation time, and pH. However, the limited number of studies to date and the significant heterogeneity in methodologies and outcome measurements make direct comparison challenging. Contaminant concentration is an important factor in the ability of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii strains to bind toxic compounds. Khadivi et al. [22] showed that a mix of L. rhamnosus, L. plantarum, and S. cerevisiae var. boulardii (107 CFU/mL) achieved a 100% adsorption rate of AFM1 at an initial concentration of 0.75 ng/mL, while the adsorption rate was 93% with an initial concentration of 0.5 ng/mL [23]. Martínez et al. [22] observed 25% of AFM1 (34.89 ng/mL) adsorption by S. cerevisiae var. boulardii at cell concentration of 107 CFU/mL.

Incubation time also plays an important role in detoxification efficacy. Silva et al. [94] used the yeasts S. cerevisiae var. boulardii and S. cerevisiae and the bacterium L. delbrueckii to investigate the reduction of AFB1 produced by A. parasiticus. The probiotic strain S. cerevisiae var. boulardii (107 CFU/mL) adsorbed 65.8% of the AFB1 produced by the fungus during the 7-day incubation period [94]. Rezasoltani et al. [82] evaluated S. cerevisiae var. boulardii, L. casei, or L. acidophilus for removal of AFM1 at two different incubation times (30 and 90 min). They observed that among the three strains used, the yeast S. cerevisiae var. boulardii achieved the highest percentage of AFM1 removal, reaching 96.8% at a cell concentration of 109 CFU/mL with 90 min of incubation. Under the same conditions, the yeast reached 91.5% under an incubation time of 30 min [82]. pH is also an important factor that can influence the effectiveness of probiotic strains in absorbing toxic compounds. Pereyra et al. during a gastrointestinal simulation, analyzed the adsorption capacity of AFB1 by S. cerevisiae var. boulardii grown in different culture media. After simulation, with an alkaline condition (pH = 8), S. cerevisiae var. boulardii produced in a medium of soluble extract of dried distillers’ grains was able to bind 5.72 μg/g of AFB1 [95]. At neutral environment (pH = 7), S. cerevisiae var. boulardii obtained an AFB1 adsorption capacity of 86.7% when coated with whey protein concentrate and lyophilized [96].

While studies do not directly evaluate detoxification in foods; therefore, in vitro and in vivo findings are included only briefly to illustrate the biological relevance of adsorption mechanisms. In vitro digestive-simulation studies indicate that S. cerevisiae var. boulardii can bind DON and AFB1, reducing their cytotoxicity, consistent with adsorption behavior observed in food-matrix studies [96,97]. Animal studies demonstrate that ingestion of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii mitigates downstream physiological effects of DON exposure, supporting the biological relevance of its adsorption capacity [92,98]. Additional rodent studies show attenuation of toxic effects from phthalates, bisphenol A, and pesticides when probiotics, including S. cerevisiae var. boulardii, are administered [54,99,100]. Probiotic mixtures containing S. cerevisiae var. boulardii have also shown protective effects in rodent models of arsenic exposure [101,102,103]. Reported efficacy varies with strain/phenotype (including flocculation and wall composition), contact time (minutes–days), dose (1 × 107–1 × 109 CFU/mL), contaminant load, and matrix. Many studies use model systems and do not include desorption tests, realistic residue levels, or sensory endpoints, and strain identifiers are sometimes missing. Since adsorption is inherently reversible, desorption may occur during food processing, storage, or digestion, which represents a critical limitation that must be assessed for industrial applications. Adsorption is often rapid yet reversible, and stability under processing and gastrointestinal-like conditions remains incompletely characterized. To aid comparability and translation, future studies should report the strain ID, dose (log CFU/mL or biomass g/L), contact time, pH, temperature, matrix composition, contaminant level (ng/mL or mg/kg), and outcomes as percent removal (or binding capacity with units), with mass balance where possible.

4. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

4.1. Enhancing Efficacy Through Genetic and Metabolic Engineering

Genetic and metabolic engineering now make it possible to rationally design improved S. cerevisiae var. boulardii strains. While numerous such strategies have been developed, their relevance to food-detoxification applications depends on whether they improve contaminant binding, stability, or performance in food matrices. A recent work adapting CRISPR-Cas9 to this yeast opened the door to targeted strain improvement [104,105,106], which could be applied to strengthen cell-wall binding sites or reduce desorption in food systems. A clear priority is to increase binding affinity and stability toward mycotoxins and PTE. One route is to engineer flocculins and other cell-wall adhesins so that interactions with target contaminants are stronger and ideally less reversible [107]. Such modifications are directly relevant to improving adsorption efficiency in food-based detoxification processes. For example, an S. cerevisiae var. boulardii strain expressing a fibronectin-targeting ligand showed enhanced adhesion to inflamed mucosa [108]. However, its relevance lies only in illustrating how targeted ligand expression could also be directed toward contaminant motifs relevant to foods. In parallel, engineering can amplify endogenous detoxification enzymes (e.g., proteases, phosphatases) or introduce novel catabolic activities to broaden the range of degradable compounds [109,110]. Applying these enzymatic strategies to foodborne contaminants would broaden the yeast’s capacity beyond adsorption alone. Feasibility has already been demonstrated by expressing human lysozyme in S. cerevisiae var. boulardii for gut health applications [106], although this is not food-specific and should be interpreted only as evidence that foreign proteins can be expressed successfully. From a regulatory and safety perspective, strains that avoid antibiotic markers are desirable [105]. Auxotrophic systems such as uracil auxotrophy allow selection and maintenance without antibiotics and remain a practical framework for industrial and clinical use [110,111]. Hence, such systems should be considered primarily insofar as they support the safe use of engineered strains for food-detoxification purposes.

4.2. Elucidating Novel Mechanisms with Multi-Omics Technologies

Systems biology tools can move the field beyond descriptive findings to mechanism. Metabolomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics together can reveal the molecular basis of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii’s actions [112]. When applied to food matrices, these approaches can identify specific metabolites, cell-wall components and or proteins that directly govern contaminant binding or influence adsorption stability. Metabolomics, for instance, can profile the exometabolome and uncover bioactive molecules that extend beyond known enzymes and binding proteins [113]. These analyses may clarify whether secreted or surface-associated metabolites enhance contaminant sequestration in foods. Non-targeted analyses have already detected metabolites such as phenyllactic acid and 2-hydroxyisocaproic acid in S. cerevisiae var. boulardii, absent from S. cerevisiae, that may underpin distinct antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [41]. Only those metabolites affecting contaminant interactions in food systems are relevant to the detoxification context. Proteomics and transcriptomics, in turn, can map secreted proteins, cell-wall components, and host–microbe interactions across food matrices and tissues [114]. These valuable tools can be used to identify the binding motifs, stress-response pathways, and adsorption-associated structures that determine strain performance in foods. As example, transcriptomic data indicate that S. cerevisiae var. boulardii can reverse the DON-induced shift in intestinal gene expression and dampen inflammatory signaling (NF-κB, p38 MAPK) [92]. Though this reflects post-ingestion physiological protection rather than food-matrix detoxification and is therefore only indirectly relevant. Future omics work should instead focus on how the yeast behaves within food environments, which components mediate contaminant binding, and how processing conditions influence these mechanisms.

4.3. Synergistic Biocontrol Communities for Scalable Food Detoxification

Progress will likely require a change from single-strain solutions to multi-species consortia. Combining S. cerevisiae var. boulardii with LAB can generate complementary modes of action and improve functional stability across diverse food matrices [115]. Studies already demonstrate LAB–yeast synergy, including enhanced growth, survival, and technological performance in food systems [21,116]. These interactions may also strengthen adsorption performance via co-aggregation or complementary binding activities. Further robustness and detoxification capacity can be achieved by pairing S. boulardii with non-living components such as prebiotics or postbiotics, especially if these enhance adsorption stability or reduce desorption during food processing or storage [115]. From a translational perspective, major bottlenecks lie in production, stabilization, and delivery. Cost-effective, large-scale fermentation requires optimization for biomass yield and retention of functional traits, but only those that capably affect contaminant binding and stability in the food matrices of interest. Stabilization methods more economical than freeze-drying should be prioritized [117], provided they preserve adsorption capacity and minimize post-processing desorption. Integrating these elements, as consortium design, bioprocess optimization, and practical delivery formats, will be essential to developing S. cerevisiae var. boulardii-based detoxification systems that are feasible for large-scale food applications [118,119]. Immobilization or entrapment of yeast cell-wall fractions on nano-silica or alginate matrices is one promising approach, as it reduces desorption, enables adsorbent reuse, and maintains high AFM1 removal efficiencies [84].

Probiotic candidates intended for food applications must meet GRAS (U.S.) or QPS (EU) criteria [120], exhibit minimal risk of antimicrobial-resistance gene transfer [121], and demonstrate product- and gastrointestinal-stability during scalable, genetically stable manufacturing processes [122]. For food-detoxification uses, the primary considerations include contaminant-binding stability, safety of the yeast preparation, and its impact on food quality. Saccharomyces cerevisiae holds GRAS and QPS status; S. cerevisiae var. boulardii falls within this species, but product- and strain-specific safety evaluations remain necessary when proposed as a decontamination aid. In food matrices, viable yeasts may cause spoilage through gas and ethanol production or alterations to texture and flavor, making heat-inactivated cells or purified cell-wall fractions more suitable for pre-consumption detoxification. For co-ingestion applications, rare cases of fungemia have been reported in severely immunocompromised individuals; thus, GMP/HACCP controls, appropriate strain selection, and clear labeling are required to mitigate risk. Regulatory approval typically involves submission of a GRAS notice in the U.S. or a QPS-based dossier in the EU specifying intended use, safety characterization, controls on residual activity, and potential sensory impacts. Within the context of food detoxification, regulatory considerations should emphasize functional stability, desorption risk, and performance consistency under real processing conditions.

5. Conclusions

Chronic dietary exposure to chemical contaminants contributes to a broad spectrum of toxic effects. Although the current evidence base is modest, studies on the probiotic yeast S. cerevisiae var. boulardii has potential for biological detoxification across mycotoxins, pesticides, PTE, and packaging migrants such as BPA and phthalates. Performance is shaped by contaminant load, contact time, pH, strain and dose, formulation (e.g., encapsulation), and properties of the food matrix. Adsorption predominates, with complementary contributions from enzymatic detoxification, host modulatory effects, anti-virulence activity, and competitive exclusion. Two persistent obstacles are the reversibility of binding and methodological heterogeneity across studies. Priority work should now focus on: (i) standardized protocols across matrices and contaminant classes; (ii) disentangling adsorption versus degradation and stabilizing binding; (iii) dose–response and kinetic data under realistic processing and storage conditions; (iv) sensory, quality, and safety assessments; (v) scalable production and delivery formats (viable, inactivated, or cell wall fractions); and (vi) clear regulatory pathways for food applications. Progress on these fronts will help move S. cerevisiae var. boulardii-based detoxification from promise to practice and reduce the burden of foodborne chemical hazards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N.P. and C.A.F.d.O.; methodology, K.N.P., A.C.D.d.O., S.U. and U.N.; validation, S.A. and C.A.F.d.O.; formal analysis, S.U. and U.N.; investigation, K.N.P., A.C.D.d.O. and H.F.d.S.; resources, C.A.F.d.O.; data curation, H.F.d.S., S.U. and U.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N.P., S.U. and U.N.; writing—review and editing, S.U., U.N., S.A. and C.A.F.d.O.; visualization: S.A.; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, C.A.F.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant numbers: 2022/03952-1, 2023/05989-2 and 2024/00896-9.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for the financial support and scholarships.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Średnicka, P.; Juszczuk-Kubiak, E.; Wójcicki, M.; Akimowicz, M.; Roszko, M.Ł. Probiotics as a Biological Detoxification Tool of Food Chemical Contamination: A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 153, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, I.A.; Koh, W.Y.; Paek, W.K.; Lim, J. The Sources of Chemical Contaminants in Food and Their Health Implications. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.; Ye, Z.; Kakade, A.; Virk, A.K.; Li, X.; Liu, P. A Review on Gut Remediation of Selected Environmental Contaminants: Possible Roles of Probiotics and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2018, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.S.; Menon, S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Gupta, N.; Bandral, J.D.; Gandotra, G.; Anjum, N. Food Safety and Hygiene: A Review. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 8, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Nonthermal Physical Technologies to Decontaminate and Extend the Shelf-Life of Fruits and Vegetables: Trends Aiming at Quality and Safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2095–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebelo, K.; Malebo, N.; Mochane, M.J.; Masinde, M. Chemical Contamination Pathways and the Food Safety Implications along the Various Stages of Food Production: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Freire, L.; Rezende, V.; Noman, M.; Ullah, S.; Abdullah; Badshah, G.; Afridi, M.; Tonin, F.; de Oliveira, C. Occurrence of Mycotoxins in Foods: Unraveling the Knowledge Gaps on Their Persistence in Food Production Systems. Foods 2023, 12, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ali, S.; Rezende, V.T.; Nabi, G.; Tonin, F.G.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. Global Occurrence and Levels of Mycotoxins in Infant Foods: A Systematic Review (2013–2024). Food Control 2025, 171, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in Occurrence, Importance, and Mycotoxin Control Strategies: Prevention and Detoxification in Foods. Foods 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Pradhan, S.; Chakrabarti, S.; Mondal, K.C.; Ghosh, K. Current Status of Probiotic and Related Health Benefits. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, T.; Negi, R.; Sharma, B.; Kour, D.; Kumar, S.; Rai, A.K.; Rustagi, S.; Singh, S.; Sheikh, M.A.; Kumar, K.; et al. Diversity, Distribution and Role of Probiotics for Human Health: Current Research and Future Challenges. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 53, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Li, J. Complicated Interactions between Bio-Adsorbents and Mycotoxins during Mycotoxin Adsorption: Current Research and Future Prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchetti, G.M.; Jadán-Piedra, C.; Monedero, V.; Zúñiga, M.; Vélez, D.; Devesa, V. Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeasts to Reduce Exposure to Chemical Food Contaminants and Toxicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Saari, N.; Meor Hussin, A.S. Review on the Biological Detoxification of Mycotoxins Using Lactic Acid Bacteria to Enhance the Sustainability of Foods Supply. Molecules 2020, 25, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corassin, C.H.; Bovo, F.; Rosim, R.E.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Efficiency of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains to Bind Aflatoxin M1 in UHT Skim Milk. Food Control 2013, 31, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Effect of Yeast Cell Morphology, Cell Wall Physical Structure and Chemical Composition on Patulin Adsorption. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem-Bekhit, M.M.; Riad, O.K.M.; Selim, H.M.R.M.; Tohamy, S.T.K.; Taha, E.I.; Al-Suwayeh, S.A.; Shazly, G.A. Box–Behnken Design for Assessing the Efficiency of Aflatoxin M1 Detoxification in Milk Using Lactobacillus Rhamnosus and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Life 2023, 13, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.T.; Balthazar, C.F.; Silva, R.; Rocha, R.S.; Graça, J.S.; Esmerino, E.A.; Silva, M.C.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Duarte, M.C.K.H.; Freitas, M.Q.; et al. Impact of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Food Texture. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, C.; Qin, X.; Zhou, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Xie, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Saccharomyces Boulardii, a Yeast Probiotic, Inhibits Gut Motility through Upregulating Intestinal Serotonin Transporter and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 181, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.Z.A.; Liu, S.Q. Fortifying Foods with Synbiotic and Postbiotic Preparations of the Probiotic Yeast, Saccharomyces Boulardii. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.P.; Magnoli, A.P.; González Pereyra, M.L.; Cavaglieri, L. Probiotic Bacteria and Yeasts Adsorb Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Degrade It to Less Toxic AFM1-Metabolites. Toxicon 2019, 172, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadivi, R.; Razavilar, V.; Anvar, S.A.A.; Akbari-Adergani, B. Aflatoxin M1-Binding Ability of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains and Saccharomyces Boulardii in the Experimentally Contaminated Milk Treated with Some Biophysical Factors. Arch. Razi Inst. 2020, 75, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniszewski, A.; Kordowska-Wiater, M. Probiotic and Potentially Probiotic Yeasts—Characteristics and Food Application. Foods 2021, 10, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmann, M. The Benefits of Saccharomyces Boulardii. In The Yeast Role in Medical Applications; InTech: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Czerucka, D.; Dahan, S.; Mograbi, B.; Rossi, B.; Rampal, P. Saccharomyces Boulardii Preserves the Barrier Function and Modulates the Signal Transduction Pathway Induced in Enteropathogenic Escherichia Coli-Infected T84 Cells. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 5998–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukaszewicz, M. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Var. Boulardii—Probiotic Yeast. In Probiotics; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Czerucka, D.; Piche, T.; Rampal, P. Review Article: Yeast as Probiotics—Saccharomyces Boulardii. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 26, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, H.F.; Carosia, M.F.; Pinheiro, C.; de Carvalho, M.V.; de Oliveira, C.A.F.; Kamimura, E.S. On Probiotic Yeasts in Food Development: Saccharomyces Boulardii, a Trend. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e92321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, K.Y.F.; García-Ríos, E.; Costa, C.E.; Guillamón, J.M.; Domingues, L.; Teixeira, J.; van Gulik, W.M. Selection and Subsequent Physiological Characterization of Industrial Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains during Continuous Growth at Sub- and- Supra Optimal Temperatures. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 26, e00462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, R.; Hosseinzadeh, D. Probiotics and Gastro-Intestinal Disorders Augmentation, Enhancement, and Strengthening of Epithelial Lining. In Probiotics: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhance Health and Mitigate Disease; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 188–215. ISBN 9781040036167. [Google Scholar]

- Krasowska, A.; Murzyn, A.; Dyjankiewicz, A.; Łukaszewicz, M.; Dziadkowiec, D. The Antagonistic Effect of Saccharomyces Boulardii on Candida Albicans Filamentation, Adhesion and Biofilm Formation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.S.; Dalmasso, G.; Arantes, R.M.E.; Doye, A.; Lemichez, E.; Lagadec, P.; Imbert, V.; Peyron, J.F.; Rampal, P.; Nicoli, J.R.; et al. Interaction of Saccharomyces Boulardii with Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Protects Mice and Modifies T84 Cell Response to the Infection. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8925, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontier-Bres, R.; Munro, P.; Boyer, L.; Anty, R.; Imbert, V.; Terciolo, C.; André, F.; Rampal, P.; Lemichez, E.; Peyron, J.F.; et al. Saccharomyces Boulardii Modifies Salmonella Typhimurium Traffic and Host Immune Responses along the Intestinal Tract. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman-Davis, R.; Figurska, M.; Cywinska, A. Gut Microbiota Manipulation in Foals—Naturopathic Diarrhea Management, or Unsubstantiated Folly? Pathogens 2021, 10, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moré, M.I.; Swidsinski, A. Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745 Supports Regeneration of the Intestinal Microbiota after Diarrheic Dysbiosis—A Review. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2015, 8, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, P.; Almeida, V.; Yılmaz, M.; Teixeira, M.C. Saccharomyces Boulardii: What Makes It Tick as Successful Probiotic? J. Fungi 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Ruszkowski, J.; Fic, M.; Folwarski, M.; Makarewicz, W. Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745: A Non-Bacterial Microorganism Used as Probiotic Agent in Supporting Treatment of Selected Diseases. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Mansell, T.J. Yeasts as Probiotics: Mechanisms, Outcomes, and Future Potential. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 137, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Saccharomyces Boulardii in Adult Patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Wen, X.; Zhang, G.; Cai, J.; Qiao, Z.; An, Z.; Zheng, J.; Li, L. Unique Probiotic Properties and Bioactive Metabolites of Saccharomyces Boulardii. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2023, 15, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Ondari, E.N.; Ogbonna, C.U.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Baran, K.; Okpala, C.O.R.; Korzeniowska, M.; Guiné, R.P.F. Mycotoxins Affecting Animals, Foods, Humans, and Plants: Types, Occurrence, Toxicities, Action Mechanisms, Prevention, and Detoxification Strategies—A Revisit. Foods 2021, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, W.; Iqbal, S.Z.; Ahmad, K.; Majid, A.; Haider, W.; Li, X. Mycotoxins: A Comprehensive Review of Its Global Trends in Major Cereals, Advancements in Chromatographic Detections and Future Prospectives. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanushree, M.P.; Sailendri, D.; Yoha, K.S.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Mycotoxin Contamination in Food: An Exposition on Spices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patial, V.; Asrani, R.K.; Thakur, M. Food-Borne Mycotoxicoses: Pathologies and Public Health Impact. In Foodborne Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 239–274. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.Z. Mycotoxins in Food, Recent Development in Food Analysis and Future Challenges; a Review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, E.; Niemcewicz, M.; Ceremuga, M.; Stela, M.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Siadkowski, A.; Bijak, M. Molecular Aspects of Mycotoxins—A Serious Problem for Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC. IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Ren, J.; Hou, Y.; Han, Z.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y. Exposure Level of Neonicotinoid Insecticides in the Food Chain and the Evaluation of Their Human Health Impact and Environmental Risk: An Overview. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-H.; Xiao, J.-J.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Fu, Y.-Y.; Ye, Z.; Liao, M.; Cao, H.-Q. Interactions of Food Matrix and Dietary Components on Neonicotinoid Bioaccessibility in Raw Fruit and Vegetables. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhang, A.; Tan, M.; Yan, S.; Jiang, D. Transfer of Heavy Metals along the Food Chain: A Review on the Pest Control Performance of Insect Natural Enemies under Heavy Metal Stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides and Human Chronic Diseases: Evidences, Mechanisms, and Perspectives. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 268, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmad, F.A.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Zeyaullah, M.d.; AlShahrani, A.M.; Muzammil, K.; Saati, A.A.; Wahab, S.; Elbendary, E.Y.; Kambal, N.; et al. Pesticides Impacts on Human Health and the Environment with Their Mechanisms of Action and Possible Countermeasures. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralić, K.; Pavić, A.; Javorac, D.; Živančević, K.; Božić, D.; Radaković, N.; Antonijević Miljaković, E.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Ćurčić, M.; Bulat, Z.; et al. Comprehensive Investigation of Hepatotoxicity of the Mixture Containing Phthalates and Bisphenol A. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445, 130404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridson, J.H.; Masterton, H.; Theobald, B.; Risani, R.; Doake, F.; Wallbank, J.A.; Maday, S.D.M.; Lear, G.; Abbel, R.; Smith, D.A.; et al. Leaching and Transformation of Chemical Additives from Weathered Plastic Deployed in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaauwendraad, S.M.; Shahin, S.; Duh-Leong, C.; Liu, M.; Kannan, K.; Kahn, L.G.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Ghassabian, A.; Trasande, L. Fetal Bisphenol and Phthalate Exposure and Early Childhood Growth in a New York City Birth Cohort. Environ. Int. 2024, 187, 108726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monisha, R.S.; Mani, R.L.; Sivaprakash, B.; Rajamohan, N.; Vo, D.-V.N. Remediation and Toxicity of Endocrine Disruptors: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1117–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas-Moreno, J.; Mora, A.; Kumar, M.; Meng, X.-Z.; Mahlknecht, J. Worldwide Risk Assessment of Phthalates and Bisphenol A in Humans: The Need for Updating Guidelines. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feruke-Bello, Y.M. Contamination of Fermented Foods with Heavy Metals. In Indigenous Fermented Foods for the Tropics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar, V.; Lee, V.R.; Gupta, V. Heavy Metal Toxicity. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, R.; Zhu, Q.; Long, T.; He, X.; Luo, Z.; Gu, R.; Wang, W.; Xiang, P. The Innovative and Accurate Detection of Heavy Metals in Foods: A Critical Review on Electrochemical Sensors. Food Control 2023, 150, 109743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.d.S.; KC, S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, Effects and Present Perspectives of Heavy Metals Contamination: Soil, Plants and Human Food Chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.-H. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.A.; Darwish, W.S. Environmental Chemical Contaminants in Food: Review of a Global Problem. J. Toxicol. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, N.; Maini Rekdal, V.; Balskus, E.P. Chemical Transformation of Xenobiotics by the Human Gut Microbiota. Science 2017, 356, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, N.A.; Ramadan, A.T.; ElRakaiby, M.T.; Aziz, R.K. Toxicomicrobiomics: The Human Microbiome vs. Pharmaceutical, Dietary, and Environmental Xenobiotics. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfliegler, W.P.; Pusztahelyi, T.; Pócsi, I. Mycotoxins—Prevention and Decontamination by Yeasts. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015, 55, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebicz, A.; Śliżewska, K. In Vitro Detoxification of Aflatoxin B1, Deoxynivalenol, Fumonisins, T-2 Toxin and Zearalenone by Probiotic Bacteria from Genus Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeast. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.-R.; Rani Ramakrishnan, S.; Kim, S.-J.; Seo, S.-O. Yeast Cell Wall Mannan Structural Features, Biological Activities, and Production Strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, G.L.; Oktaviani, L.; Balia, R.L.; Rialita, T. Potential Application of Yeast Cell Wall Biopolymers as Probiotic Encapsulants. Polymers 2023, 15, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, B.T.; Subotić, A.; Vandecruys, P.; Deleu, S.; Vermeire, S.; Thevelein, J.M. Enhancing Probiotic Impact: Engineering Saccharomyces Boulardii for Optimal Acetic Acid Production and Gastric Passage Tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0032524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, T.Y.; Lee, W.J.; Goh, H.H. Molecular Genetics and Probiotic Mechanisms of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pothoulakis, C. Review Article: Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Action of Saccharomyces Boulardii. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stier, H.; Bischoff, S.C. Influence of Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745 on the Gut-Associated Immune System. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2016, 9, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, R.; Waseem, H.; Ali, J.; Ghazanfar, S.; Ali, G.M.; Elasbali, A.M.; Alharethi, S.H. Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces: Back to Nature to Improve Human Health. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terciolo, C.; Dapoigny, M.; Andre, F. Beneficial Effects of Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745 on Clinical Disorders Associated with Intestinal Barrier Disruption. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzi, S. The Effects of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Boulardii CNCM I-1079 Supplementation on Gut Barrier Function and Systemic Inflammation in Transition Dairy Cows. Master’s Thesis, The University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, G.; Bussey, H. Cell Wall Assembly in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006, 70, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzi, L.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M.; Bevilacqua, A. Ochratoxin A Removal by Yeasts after Exposure to Simulated Human Gastrointestinal Conditions. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, M2756–M2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, E.M.; Sadek, Z.I.; El-Shafei, K.; Abd El-Khalek, A.B. Aflatoxins Binding by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. boulardii in Functional Cereal Based Ice-cream. Life Sci. J. 2011, 8, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rezasoltani, S.; Ebrahimi, N.A.; Boroujeni, R.K.; Aghdaei, H.A.; Norouzinia, M. Detoxification of Aflatoxin M1 by Probiotics Saccharomyces Boulardii, Lactobacillus Casei, and Lactobacillus Acidophilus in Reconstituted Milk. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2022, 15, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.A.; Anniballi, F.; Austin, J.W. Adult Intestinal Toxemia Botulism. Toxins 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidimehr, A.; Khiabani, M.S.; Mokarram, R.R.; Kafil, H.S.; Ghiasifar, S.; Vahidimehr, A. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Cell Walls Immobilized on Nano-Silica Entrapped in Alginate as Aflatoxin M1 Binders. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tian, Z.; Cheng, H.; Xu, G.; Zhou, H. Adsorption Process and Mechanism of Heavy Metal Ions by Different Components of Cells, Using Yeast (Pichia Pastoris) and Cu2+ as Biosorption Models. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17080–17091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Yan, S.; Sun, X.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z. Applications of Yeasts in Heavy Metal Remediation. Fermentation 2025, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujić, S.M.; Radojević, I.D.; Vasić, S.M.; Čomić, L.R.; Ostojić, A.M. Heavy metal tolerance and removal efficiency of the Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa AND Saccharomyces Boulardii planktonic cells and biofilm. Kragujev. J. Sci. 2018, 40, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.; Mudassar, M.; Fazio, F.; Noreen, S.; Quayson, A.; Mandal, S. Application of Probiotic-Based Diets in Enhancing Immune Response and Disease Resistance in Farmed Tilapia. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394425649_Application_of_Probiotic-Based_Diets_in_Enhancing_Immune_Response_and_Disease_Resistance_in_Farmed_Tilapia (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Wang, J.; Chen, C. Biosorption of Heavy Metals by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2006, 24, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M. Predicting the Mechanisms of Probiotic Activity in Saccharomyces Boulardii: A Contribution to the Development of the ProBioYeastract Database. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tomicic, Z.; Colovic, R.; Cabarkapa, I.; Vukmirovic, D.; Djuragic, O.; Tomicic, R. Beneficial Properties of Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces Boulardii. Food Feed. Res. 2016, 43, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassane-Kpembi, I.; Pinton, P.; Hupé, J.F.; Neves, M.; Lippi, Y.; Combes, S.; Castex, M.; Oswald, I.P. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Boulardii Reduces the Deoxynivalenol-Induced Alteration of the Intestinal Transcriptome. Toxins 2018, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontier-Bres, R.; Rampal, P.; Peyron, J.F.; Munro, P.; Lemichez, E.; Czerucka, D. The Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745 Strain Shows Protective Effects against the B. Anthracis LT Toxin. Toxins 2015, 7, 4455–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, J.F.M.; Peluzio, J.M.; Prado, G.; Madeira, J.E.G.C.; Silva, M.O.; de Morais, P.B.; Rosa, C.A.; Pimenta, R.S.; Nicoli, J.R. Use of Probiotics to Control Aflatoxin Production in Peanut Grains. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 959138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, C.M.; Gil, S.; Cristofolini, A.; Bonci, M.; Makita, M.; Monge, M.P.; Montenegro, M.A.; Cavaglieri, L.R. The Production of Yeast Cell Wall Using an Agroindustrial Waste Influences the Wall Thickness and Is Implicated on the Aflatoxin B1 Adsorption Process. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloni, V.L.; Bainotti, M.B.; Vergara, L.D.; Escobar, F.; Montenegro, M.; Cavaglieri, L. Influence of Technological Procedures on Viability, Probiotic and Anti-Mycotoxin Properties of Saccharomyces Boulardii RC009, and Biological Safety Studies. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Wang, K.; Zhou, S.-N.; Wang, X.-D.; Wu, J.-E. Protective Effect of Saccharomyces Boulardii on Deoxynivalenol-Induced Injury of Porcine Macrophage via Attenuating P38 MAPK Signal Pathway. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 182, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassane-Kpembi, I.; Canlet, C.; Tremblay-Franco, M.; Jourdan, F.; Chalzaviel, M.; Pinton, P.; Cossalter, A.M.; Achard, C.; Castex, M.; Combes, S.; et al. 1H-NMR Metabolomics Response to a Realistic Diet Contamination with the Mycotoxin Deoxynivalenol: Effect of Probiotics Supplementation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 138, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, Ç.; Akpınar, E.; Aksu, E.H.; Ömür, A.D.; Yıldırım, S.; Kara, M.; Bolat, İ.; Tsatsakis, A.; Mesnage, R.; Golokhvast, K.S.; et al. Reproductive Effects of S. Boulardii on Sub-Chronic Acetamiprid and Imidacloprid Toxicity in Male Rats. Toxics 2023, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralić, K.; Živančević, K.; Jorgovanović, D.; Javorac, D.; Radovanović, J.; Gojković, T.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Ćurčić, M.; Mandinić, Z.; Bulat, Z.; et al. Probiotic Reduced the Impact of Phthalates and Bisphenol A Mixture on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Development: Merging Bioinformatics with in Vivo Analysis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 154, 112325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Khatun, S.; Maity, M.; Jana, S.; Perveen, H.; Dash, M.; Dey, A.; Jana, L.R.; Maity, P.P. Association of Vitamin B12, Lactate Dehydrogenase, and Regulation of NF-ΚB in the Mitigation of Sodium Arsenite-Induced ROS Generation in Uterine Tissue by Commercially Available Probiotics. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visciano, P. Arsenic in Water and Food: Toxicity and Human Exposure. Foods 2025, 14, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Jenisova, Z.; Feszterova, M.; Baros, S.; Liska, J.; Hudecova, D.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Arsenic: Toxicity, Oxidative Stress and Human Disease. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2011, 31, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, J.P.; Moreno, D.S.; Domingues, L. Genetic Engineering of Saccharomyces Boulardii: Tools, Strategies and Advances for Enhanced Probiotic and Therapeutic Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 84, 108663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Helal, S.E.; Peng, N. CRISPR-Cas-Based Engineering of Probiotics. BioDesign Res. 2023, 5, 0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Kong, I.I.; Zhang, G.C.; Jayakody, L.N.; Kim, H.; Xia, P.F.; Kwak, S.; Sung, B.H.; Sohn, J.H.; Walukiewicz, H.E.; et al. Metabolic Engineering of Probiotic Saccharomyces Boulardii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2280–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeini, K.; Zoghi, A.; Khosravi-Darani, K. Application of Yeasts as Pollutant Adsorbents. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpepper, T.; Senthil, K.; Vlcek, J.; Hazelton, A.; Heavey, M.K.; Sellers, R.S.; Nguyen, J.; Arthur, J.C. Engineered Probiotic Saccharomyces Boulardii Reduces Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer Burden in Mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, 70, 2348–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Singh, D.; Bose, S.K.; Trivedi, P.K. Biodegradation of Environmental Pollutant through Pathways Engineering and Genetically Modified Organisms Approaches. In Microorganisms for Sustainable Environment and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 137–165. ISBN 9780128190012. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, L.E.; Fasken, M.B.; McDermott, C.D.; McBride, S.M.; Kuiper, E.G.; Guiliano, D.B.; Corbett, A.H.; Lamb, T.J. Functional Heterologous Protein Expression by Genetically Engineered Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces Boulardii. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyachandran, S.; Vibhute, P.; Kumar, D.; Ragavendran, C. Random Mutagenesis as a Tool for Industrial Strain Improvement for Enhanced Production of Antibiotics: A Review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrocino, I.; Rantsiou, K.; McClure, R.; Kostic, T.; de Souza, R.S.C.; Lange, L.; FitzGerald, J.; Kriaa, A.; Cotter, P.; Maguin, E.; et al. The Need for an Integrated Multi-OMICs Approach in Microbiome Science in the Food System. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinschen, M.M.; Ivanisevic, J.; Giera, M.; Siuzdak, G. Identification of Bioactive Metabolites Using Activity Metabolomics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stastna, M. The Role of Proteomics in Identification of Key Proteins of Bacterial Cells with Focus on Probiotic Bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedin, K.A.; Mirhakkak, M.H.; Vaaben, T.H.; Sands, C.; Pedersen, M.; Baker, A.; Vazquez-Uribe, R.; Schäuble, S.; Panagiotou, G.; Wellejus, A.; et al. Saccharomyces Boulardii Enhances Anti-Inflammatory Effectors and AhR Activation via Metabolic Interactions in Probiotic Communities. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamah, A.K. Physicochemical and Microbial Characteristics of Yogurt with Added Saccharomyces Boulardii. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2017, 5, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.T.; da Silva, R.N.A.; Borges, A.S.; Siqueira, A.E.B.; Puerari, C.; Bento, J.A.C. Smart and Functional Probiotic Microorganisms: Emerging Roles in Health-Oriented Fermentation. Fermentation 2025, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhong, Q. Drying of Probiotics to Enhance the Viability during Preparation, Storage, Food Application, and Digestion: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Sun, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J.; Wu, T. Enteric Delivery of Probiotics: Challenges, Techniques, and Activity Assays. Foods 2025, 14, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the Update of the List of QPS-recommended Biological Agents Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA (2017–2019). EFSA J. 2020, 18, e05966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duche, R.T.; Singh, A.; Wandhare, A.G.; Sangwan, V.; Sihag, M.K.; Nwagu, T.N.T.; Panwar, H.; Ezeogu, L.I. Antibiotic Resistance in Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria of Fermented Foods and Human Origin from Nigeria. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, A.A.; Pinto-Neto, W.d.P.; da Paixão, G.A.; Santos, D.d.S.; De Morais, M.A., Jr.; De Souza, R.B. Journey of the Probiotic Bacteria: Survival of the Fittest. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).