Authentication of Propolis: Integrating Chemical Profiling, Data Analysis and International Standardization—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

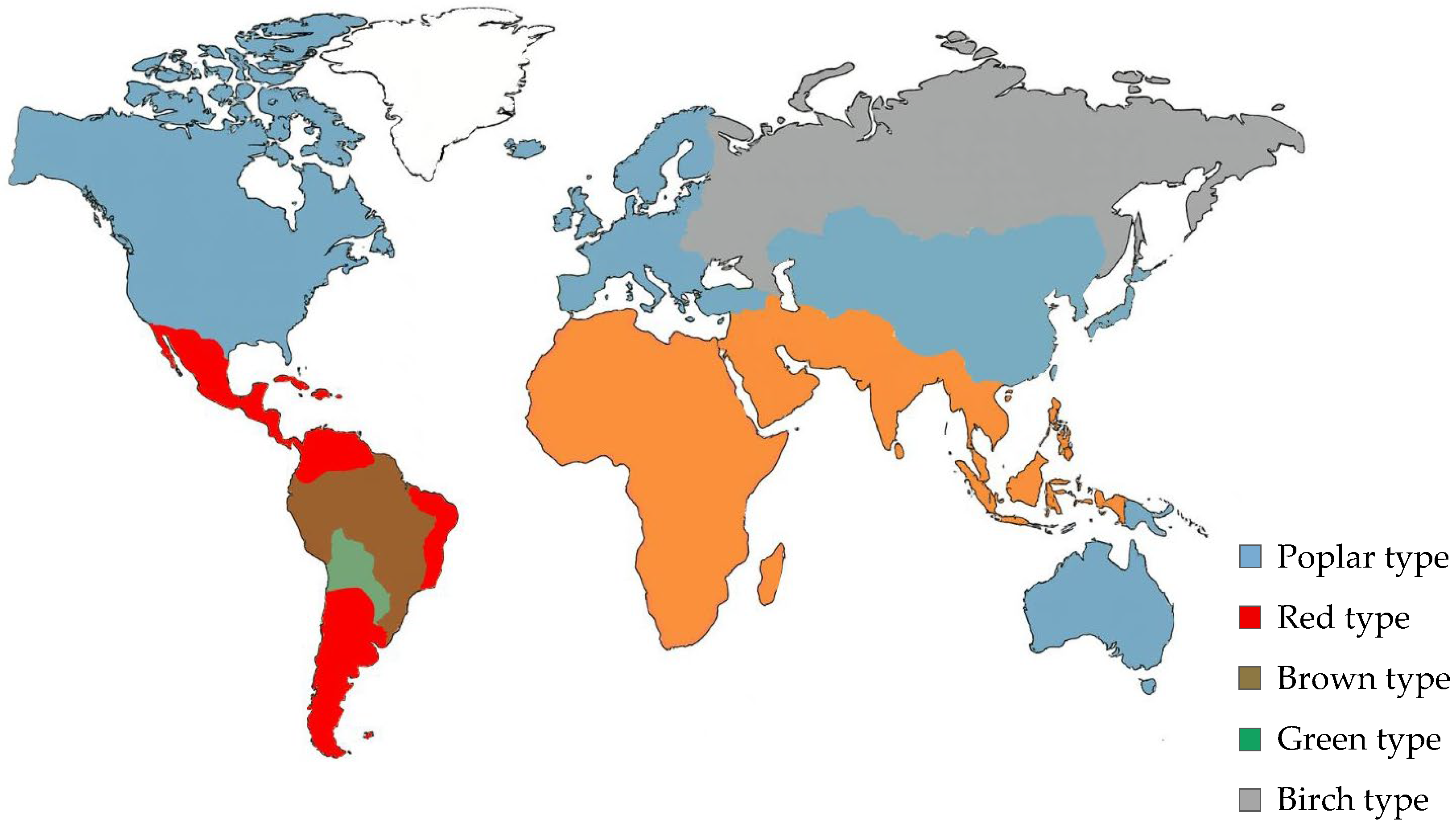

2. Botanical and Geographical Variability

3. Fraud and Adulteration in Propolis

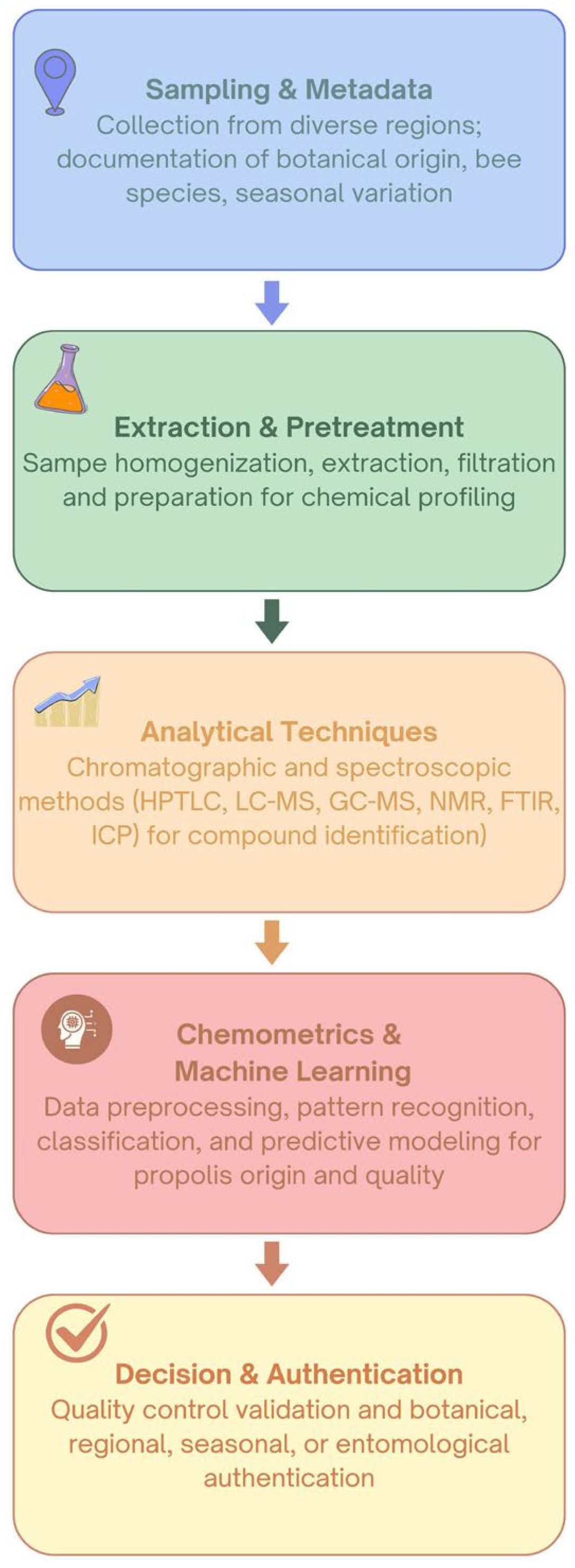

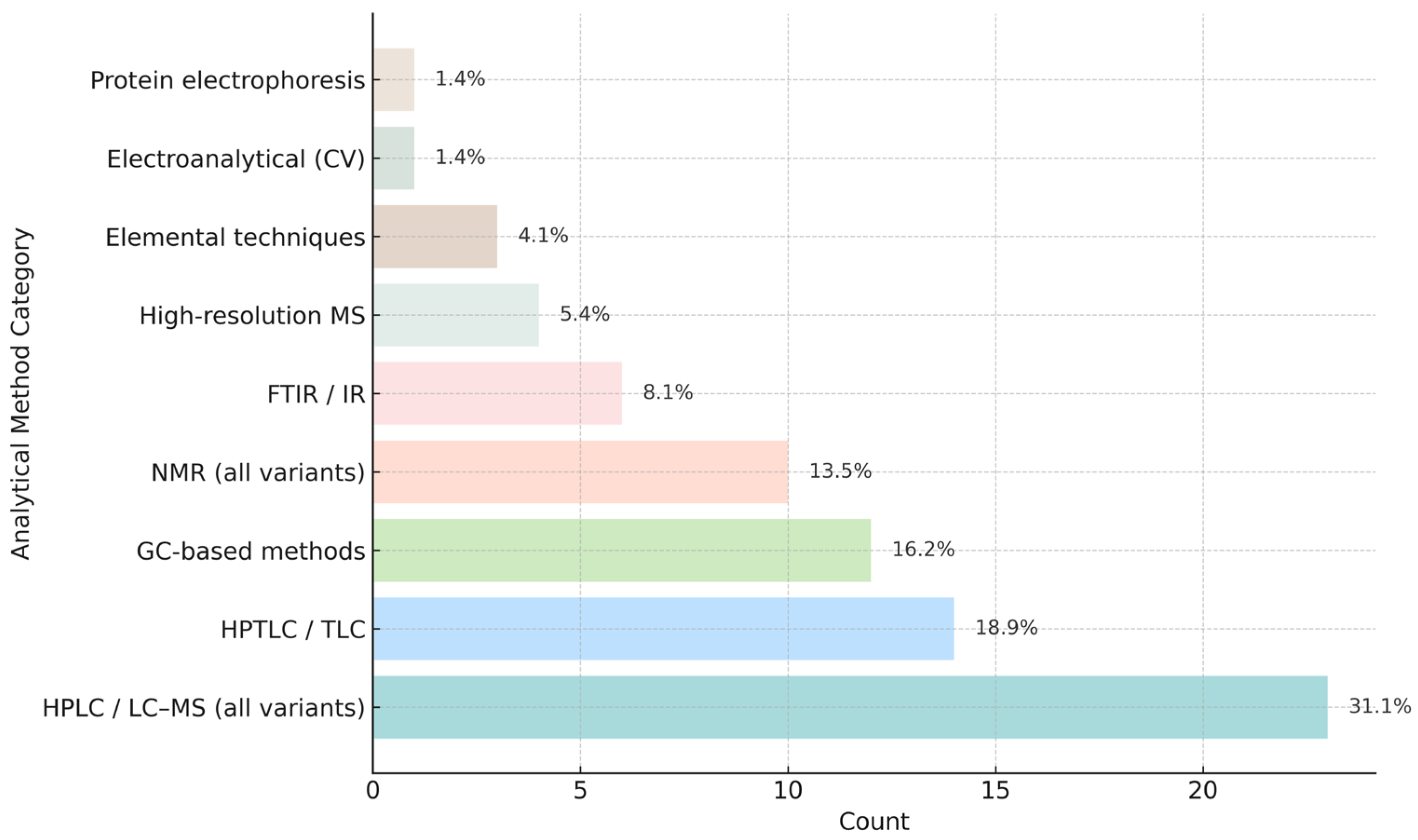

4. Analytical Approaches for Propolis Profiling and Characterization

4.1. Chromatographic Techniques

4.2. Spectroscopic Techniques

4.3. Elemental Analysis

4.4. Volatilomics

4.5. Proteomics

4.6. Electroanalytical Techniques

4.7. Palynology

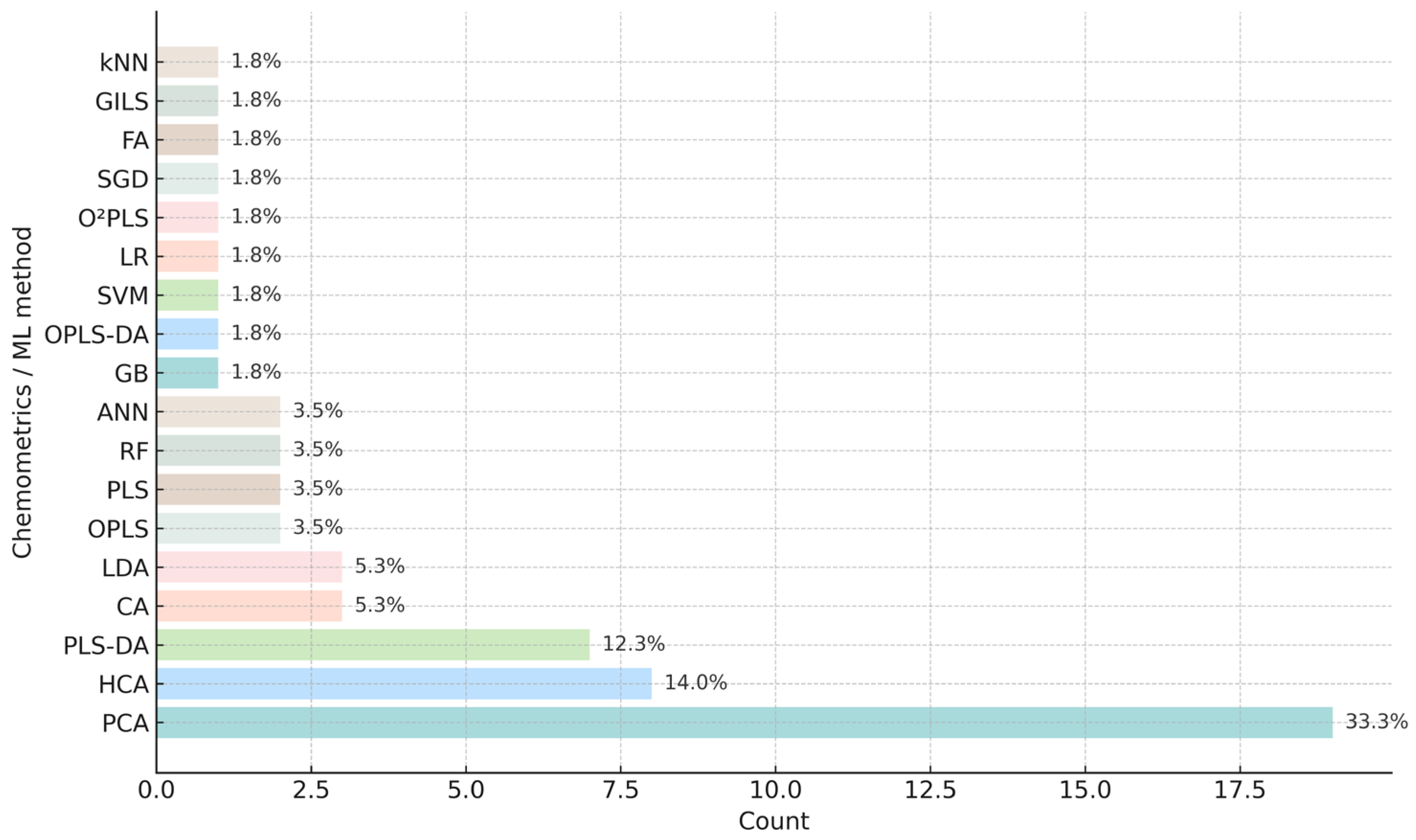

5. Chemometrics and Machine Learning for Data Treatment

5.1. Unsupervised, Supervised and Regression Chemometric Tools

5.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

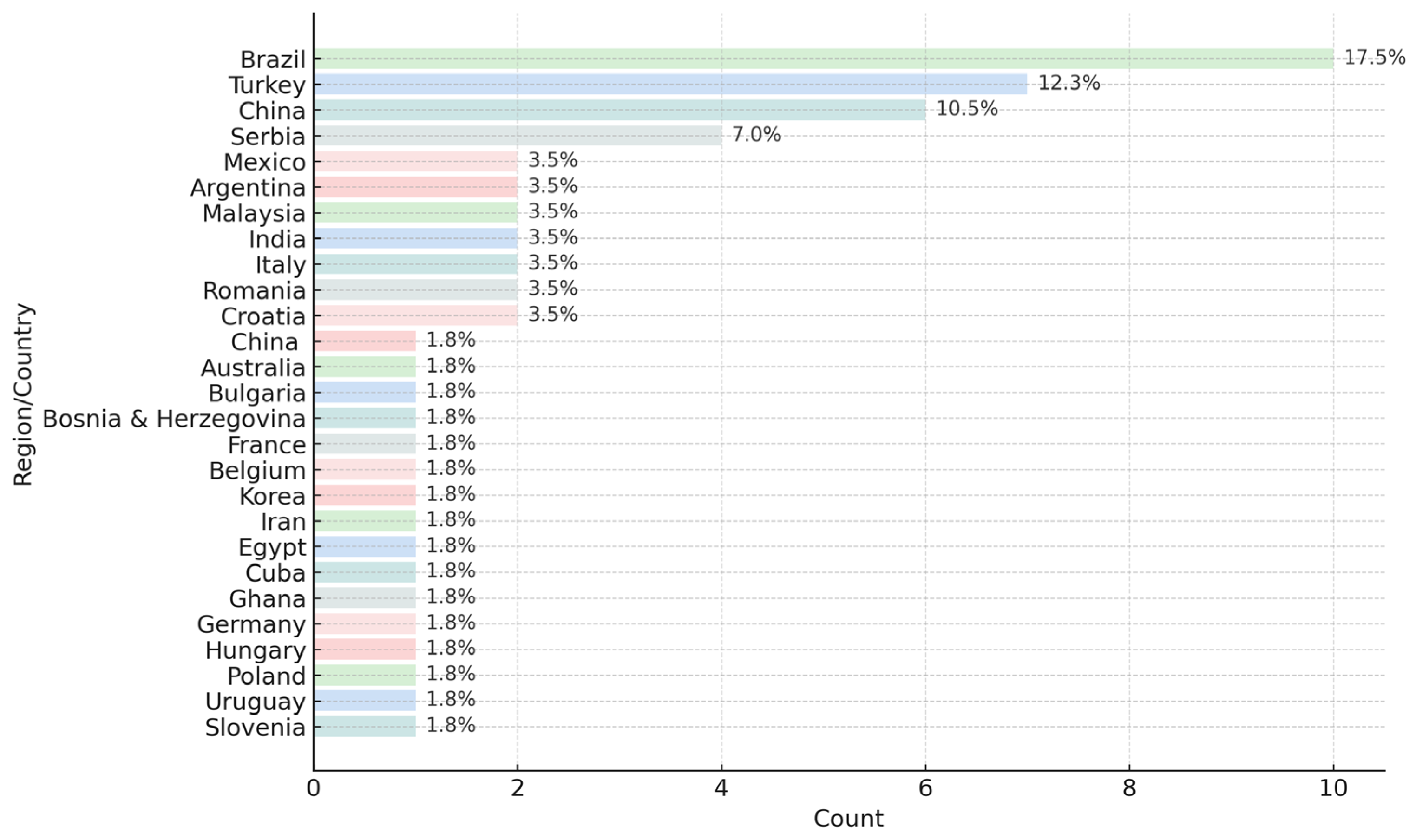

6. Geographical Case Studies

6.1. Europe

6.2. Latin America

6.3. Asia

6.4. Africa

6.5. Australia

| Propolis Type | Region/Country | Bee Type | N Samples | Analytical Methods | Target Markers | Chemometrics/ML | Authentication Target | Key Outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poplar-type | Turkey | A.m. caucasica; A.m. anatolica; A.m. carnica | 3 | GC–MS | 48 compounds; Populus and Salix markers | - | Bee species origin | Bee race behavior differences influence propolis composition | [52] |

| Poplar-type | Croatia | Apis mellifera | 6 | HPLC; HPTLC; GC-MS; UV-Vis | Flavonoids; Phenolic acids | - | Geographical origin; QC | HPTLC, HPLC and GC characterization and QC | [64] |

| Chinese poplar-type | China | Apis mellifera | 12 | DHS-GC/MS; E-nose; GC-O | 99 volatiles; odor-active compounds | PCA | Geographical origin | Geographical regions classified; key odorants identified | [57] |

| Mixed-type, Multifloral | India | Apis mellifera | 30 (Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan) | LC-ESI-QTOF-MS; RP-HPLC; TPC; TFC; DPPH/FRAP | beta-Carotene; Galangin; CAPE | PCA; ANN | Geographical origin | Regional characterization of northern Indian propolis | [51] |

| Stingless bee propolis (Geniotrigona thoracica) | Malaysia | Stingless bee | 5 | HPTLC; FTIR | Flavonoids; Phenolics; Terpenoids | PCA; HCA | Geographical origin | Three clusters by location; FTIR + chemometrics classify effectively | [53] |

| Mixed-type | Ghana | Apis mellifera | 3 | TPC; TFC; DPPH; TLC | Caffeic/quinic derivatives; Quercetin; Naringenin; Hesperidin; Rosmarinic acid; Methyl cinnamate; Steroids; Triterpenoids | PCA; HCA; ANOVA | Source/solvent differentiation | Regional and solvent authentication | [46] |

| Brazilian brown | Brazil | Apis mellifera | 7 | SHS-GC-MS | Monoterpenes; Sesquiterpenes | PCA; HCA; heatmap | Botanical origin (resin source) | Volatile profile matched Araucaria angustifolia resins; strong clustering | [28] |

| Brown; Red; Yellow | Cuba | Apis mellifera | 65 | HPLC-PDA; LC-MS; 1H NMR; 13C NMR | Polyisoprenylated benzophenones; Isoflavonoids; Pterocarpans | - | Type classification (color-based) | Three chemical types: brown = benzophenones; red = isoflavonoids; yellow = aliphatic | [48] |

| Stingless bee (Melipona beecheii) | Mexico | Melipona beecheii | 35 | UV-Vis (TPC; TFC) | Total phenolics; Total flavonoids | PCA; HCA | Geographical origin | Clustered samples by region and bioactivity | [31] |

| 16 high-grade types | Australia (different regions) | Apis mellifera | 158 | HPLC-UV; 1H NMR; DPPH assay | Phenolics; Flavonoids (chrysin; pinocembrin; galangin; prenylated stilbenes; artepillin C) | PCA; PLS-DA | Geographical origin; QC | Identified 16 high-grade types; several exceeded Brazilian green/red propolis in antioxidant capacity | [67] |

7. Regulatory and Standardization Perspectives

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alday, E.; Valencia, D.; Garibay-Escobar, A.; Domínguez-Esquivel, Z.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Rastrelli, L.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Robles-Zepeda, R.E.; Hernandez, J.; et al. Plant origin authentication of Sonoran Desert propolis: An antiproliferative propolis from a semi-arid region. Sci. Nat. 2019, 106, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankova, V.; Popova, M.; Trusheva, B. Propolis volatile compounds: Chemical diversity and biological activity: A review. Chem. Cent. J. 2014, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morlock, G.E.; Ristivojević, P.; Chernetsova, E.S. Combined multivariate data analysis of high-performance thin-layer chromatography fingerprints and direct analysis in real time mass spectra for profiling of natural products like propolis. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1328, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolaylı, S.; Birinci, C.; Kara, Y.; Ozkok, A.; Tanugur Samancı, A.E.; Şahin, H.; Yildiz, O. A melissopalynological and chemical characterization of Anatolian propolis and an assessment of its antioxidant potential. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1213–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhamizah, I.; Niza, N.F.S.M.; Rodi, M.M.M.; Zakaria, A.J.; Ismail, Z.; Mohd, K.S. Chemical and biological analyses of Malaysian stingless bee propolis extracts. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2016, 20, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdock, G.A. Review of the Biological Properties and Toxicity of Bee Propolis (Propolis). Food Chem. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, C.-P.; Li, G.Q.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Wang, K.; Hu, F.-L. Identification of catechol as a new marker for detecting propolis adulteration. Molecules 2014, 19, 10208–10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anđelković, B.; Vujišić, L.; Vučković, I.; Tešević, V.; Vajs, V.; Gođevac, D. Metabolomics study of Populus type propolis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 135, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasote, D.; Bankova, V.; Viljoen, A.M. Propolis: Chemical Diversity and Challenges in Quality Control. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1887–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarelli, M.A.; Camiña, J.M.; Pettenati, E.M.; Marchevsky, E.J.; Pellerano, R.G. Trace mineral content of Argentinean raw propolis by neutron activation analysis (NAA): Assessment of geographical provenance by chemometrics. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, R.; Borgonovo, G.; Leoni, V.; Giupponi, L.; Ceciliani, G.; Sala, S.; Bassoli, A.; Giorgi, A. Effectiveness of different analytical methods for the characterization of propolis: A case study in Northern Italy. Molecules 2020, 25, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suđi, J.; Pastor, K.; Ilić, M.; Radišić, P.; Martić, N.; Petrović, N. A Novel Approach for Improved Honey Identification and Scientific Definition: A Case of Buckwheat Honey. J. Apic. Res. 2024, 63, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutavski, Z.; Nastić, N.; Živković, J.; Šavikin, K.; Veberič, R.; Medič, A.; Pastor, K.; Jokić, S.; Vidović, S. Black Elderberry Press Cake as a Source of Bioactive Ingredients Using Green-Based Extraction Approaches. Biology 2022, 11, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivošija, S.; Jerković, I.; Nastić, N.; Zloh, M.; Jokić, S.; Banožić, M.; Aladic, K.; Vidović, S. Green pathway for utilisation of orange peel dust and in silico evaluation of pharmacological potential. Microchem. J. 2023, 193, 109132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, R.E.; Lucas, K.; Higgins, J.; Mojica, E.-R.E. ATR-FTIR characterization and multivariate analysis classification of different commercial propolis extracts. Meas. Food 2025, 18, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, H.; He, H. PAK1-Blockers: Potential Therapeutics against COVID-19. Med. Drug Discov. 2020, 6, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, J.; Glavinić, U.; Ristanić, M.; Erjavec, V.; Denk, B.; Dolašević, S.; Stanimirović, Z. Bee-Inspired Healing: Apitherapy in Veterinary Medicine for Maintenance and Improvement of Animal Health and Well-Being. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilaki, A.; Hatzikamari, M.; Stagkos-Georgiadis, A.; Goula, A.M.; Mourtzinos, I. A Natural Approach in Food Preservation: Propolis Extract as Sorbate Alternative in Non-Carbonated Beverage. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 125080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkuş, T.N.; Değer, O.; Yaşar, A. Chemical characterization of water and ethanolic extracts of Turkish propolis by HPLC-DAD and GC-MS. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2021, 44, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, L.; Marghitas, L.A.; Dezmirean, D. Quality Criteria for Propolis Standardization. Anim. Sci. Pap. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 44, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bankova, V. Chemical Diversity of Propolis and the Problem of Standardization. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankova, V.; Popova, M.; Trusheva, B. Latest Developments in Propolis Research: Chemistry and Biology. In Chemistry, Biology and Potential Applications of Honeybee Plant-Derived Products; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2016; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforcin, J.M.; Bankova, V. Propolis: Is There a Potential for the Development of New Drugs? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, S.; Hatano, A.; Yoshino, M.; Hosoya, T.; Shimamura, Y.; Masuda, S.; Kumazawa, S. Identification of the Phenolic Compounds Contributing to Antibacterial Activity in Ethanol Extracts of Brazilian Red Propolis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1293–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catchpole, O.; Mitchell, K.; Bloor, S.; Davis, P.; Suddes, A. Antiproliferative Activity of New Zealand Propolis and Phenolic Compounds vs. Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatino, A.; Salatino, M.L.F. Scientific note: Often quoted, but not factual data about propolis composition. Apidologie 2021, 52, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzelmeriç, E.; Ristivojević, P.; Trifković, J.; Daştan, T.; Yılmaz, O.; Cengiz, O.; Yeşilada, E. Authentication of Turkish propolis through HPTLC fingerprints combined with multivariate analysis and palynological data and their comparative antioxidant activity. LWT 2018, 87, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Sartori, A.G.; Spada, F.P.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Rosalen, P.L.; Ikegaki, M.; Bastos, J.K.; de Alencar, S.M. An insight into the botanical origins of propolis from permanent preservation and reforestation areas of southern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Jang, K.-S. UPLC/FT-ICR MS-based high-resolution platform for determining the geographical origins of raw propolis samples. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, A.A.; Nour, I.H.; Metwally, A.M.; Asaad, A.M.; Shams Eldin, S.M.; Ibrahim, R.S. An integrated strategy for chemical, biological and palynological standardization of bee propolis. Microchem. J. 2022, 182, 107923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Ruiz, J.C.; Pacheco López, N.A.; Rejón Méndez, E.G.; Samos López, F.A.; Medina Medina, L.; Quezada-Euán, J.J.G. Phenolic content and bioactivity as geographical classifiers of propolis from stingless bees in southeastern Mexico. Foods 2023, 12, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, K. (Ed.) Emerging Food Authentication Methodologies Using GC/MS; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafantaris, I.; Amoutzias, G.D.; Mossialos, D. Foodomics in Bee Product Research: A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.P.; Zheng, H.Q.; Liu, G.; Hu, F.L. Development and validation of HPLC method for determination of salicin in poplar buds: Application for screening of counterfeit propolis. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.W.; Sun, S.Q.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q. Rapid discrimination of extracts of Chinese propolis and poplar buds by FT-IR and 2D IR correlation spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 883, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristivojević, P.; Dimkić, I.; Güzelmeriç, E.; Trifković, J.; Knežević, M.; Berić, T.; Yeşilada, E.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Stanković, S. Profiling of Turkish propolis subtypes: Comparative evaluation of their phytochemical compositions, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. LWT 2018, 95, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayworm, M.A.S.; Fernandes-Silva, C.C.; Salatino, M.L.F.; Salatino, A. A simple and inexpensive procedure for detection of a marker of Brazilian alecrim propolis. J. Apic. Res. 2015, 54, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraschin, M.; Somensi-Zeggio, A.; Oliveira, S.K.; Kuhnen, S.; Tomazzoli, M.M.; Raguzzoni, J.C.; Zeri, A.C.M.; Carreira, R.; Correia, S.; Costa, C.; et al. Metabolic profiling and classification of propolis samples from southern Brazil: An NMR-based platform coupled with machine learning. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.; Pastor, K.; Ilić, A.; Vasić, M.; Nastić, N.; Vujić, Đ.; Ačanski, M. Legume Fingerprinting through lipid composition: Utilizing GC/MS with multivariate statistics. Foods 2023, 12, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papotti, G.; Bertelli, D.; Plessi, M.; Rossi, M.C. Use of HR-NMR to classify propolis obtained using different harvesting methods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soós, A.; Bódi, E.; Várallyay, S.; Molnár, S.; Kovács, B. Element composition of propolis tinctures prepared from Hungarian raw propolis. LWT 2022, 154, 112762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sârbu, C.; Moţ, A.C. Ecosystem discrimination and fingerprinting of Romanian propolis by hierarchical fuzzy clustering and image analysis of TLC patterns. Talanta 2011, 85, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, T.G.; Dos Santos Arruda, R.E.; da Cruz Almeida, E.T.; Dos Santos Oliveira, J.M.; Basílio-Júnior, I.D.; Celerino de Moraes Porto, I.C.; Rodrigues Sabino, A.; Tonholo, J.; Gray, A.; Ebel, R.E.; et al. Comprehensive multivariate correlations between climatic effect, metabolite profile, antioxidant capacity, and antibacterial activity of Brazilian red propolis metabolites during seasonal study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Qu, L.; Wang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Liu, H.; Nie, Z. Rapid analysis and authentication of Chinese propolis using nanoelectrospray ionization mass spectrometry combined with machine learning. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzelmeriç, E.; Özdemir, D.; Şen, N.B.; Çelik, C.; Yeşilada, E. Quantitative determination of phenolic compounds in propolis samples from the Black Sea Region (Türkiye) based on HPTLC images using partial least squares and genetic inverse least squares methods. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 229, 115338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amankwaah, F.; Addotey, J.N.; Orman, E.; Adosraku, R.; Amponsah, I.K. A comparative study of Ghanaian propolis extracts: Chemometric analysis of the chromatographic profile, antioxidant, and hypoglycemic potential and identification of active constituents. Sci. Afr. 2023, 22, e01956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, N.; Huang, H.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Chen, G.T.; Tao, S.J.; Yang, M.; Li, X.N.; Li, P.; Guo, D.A. Simultaneous quantification of eight major bioactive phenolic compounds in Chinese propolis by high-performance liquid chromatography. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta-Rubio, O.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Campo Fernandez, M.; Márquez Hernández, I.; Rosado, A.; Rastrelli, L. Chemical characterization of Cuban propolis by HPLC–PDA, HPLC–MS, and NMR: The brown, red, and yellow Cuban varieties of propolis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7502–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tian, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, H.; Hu, F. A new propolis type from Changbai Mountains in North-east China: Chemical composition, botanical origin and biological activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avula, B.; Sagi, S.; Masoodi, M.H.; Bae, J.-Y.; Wali, A.F.; Khan, I.A. Quantification and characterization of phenolic compounds from northern Indian propolis extracts and dietary supplements. J. AOAC Int. 2020, 103, 1378–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.; Chopra, H.K.; Nanda, V. Characterization and antioxidant potential of polyphenolic biomarker compounds of Indian propolis: A multivariate and ANN-based approach. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silici, S.; Kutluca, S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of propolis collected by three different races of honeybees in the same region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 99, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiazaman, A.A.M.; Mohd, K.S.; Md Zin, N.B.; Mohamad, H.; Aziz, A.N. HPTLC profiling and FTIR fingerprinting coupled with chemometric analysis of Malaysian stingless bee propolis. J. Teknol. 2023, 85, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surek, M.; Cobre, A.F.; Fachi, M.M.; Santos, T.G.; Pontarolo, R.; Crisma, A.R.; Felipe, K.B.; de Souza, W.M. Propolis authentication of stingless bees by mid-infrared spectroscopy and chemometric analysis. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 161, 113370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.G.; Peyfoon, E.; Zheng, L.; Lu, D.; Seidel, V.; Johnston, B.; Parkinson, J.A.; Fearnley, J. Application of principal components analysis to 1H-NMR data obtained from propolis samples of different geographical origin. Phytochem. Anal. 2006, 17, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiveron, A.P.; Rosalen, P.L.; Ferreira, A.G.; Thomasi, S.S.; Massarioli, A.P.; Ikegaki, M.; Franchin, M.; Sartori, A.G.O.; Alencar, S.M. Lignans as new chemical markers of a certified Brazilian organic propolis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 2135–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Qin, Z.H.; Guo, X.F.; Hu, X.S.; Wu, J.H. Geographical origin identification of propolis using GC–MS and electronic nose combined with principal component analysis. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahali, Y.; Kler, S.; Revets, D.; Planchon, S.; Leclercq, C.C.; Renaut, J.; Shoormasti, R.S.; Pourpak, Z.; Ollert, M.; Hilger, C. Proteome analysis of propolis deciphering the origin and function of its proteins. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristivojević, P.; Trifković, J.; Stanković, D.M.; Radoičić, A.; Manojlović, D.; Milojković-Opsenica, D. Cyclic Voltammetry and UV/Vis Spectroscopy in Combination with Multivariate Data Analysis for the Assessment of Authenticity of Poplar Type Propolis. J. Apic. Res. 2017, 56, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek-Gorecka, A.; Keskin, S.; Bobis, O.; Felitti, R.; Górecki, M.; Otreba, M.; Stojko, J.; Olczyk, P.; Kolayli, S.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A. Comparison of the antioxidant activity of propolis samples from different geographical regions. Plants 2022, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, K.; Salek, R.M.; Conesa, P.; Hastings, J.; de Matos, P.; Rijnbeek, M.; Mahendrakar, T.; Williams, M.; Neumann, S.; Rocca-Serra, P.; et al. MetaboLights—An Open-Access Database for Metabolomics Studies and Associated Metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D781–D786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and Community Curation of Mass Spectrometry Data with GNPS. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Ristivojević, P.; Trifković, J.; Vovk, I.; Lušić, D.; Tešić, Ž. TLC Fingerprinting and Pattern Recognition Methods in the Assessment of Authenticity of Poplar-Type Propolis. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2016, 54, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medić-Šarić, M.; Bojić, M.; Rastija, V.; Cvek, J. Polyphenolic profiling of Croatian propolis and wine. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 51, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, F.B.; Krüger, P.F.; Lima, L.C.; Caramão, E.B. Multivariate GC-MS Profiling of Brazilian Brown Propolis for Regional Authentication. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 63, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, S.; Wei, W.; Ping, S.; Shen, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, F. Development of High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Method for Quality and Authenticity Control of Chinese Propolis. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, C1–C8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.T.N.; Brooks, P.R.; Bryen, T.J.; Williams, S.; Berry, J.; Tavian, F.; McKee, B.; Tran, T.D. Quality assessment and chemical diversity of Australian propolis from Apis mellifera bees. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CXS 12-1981; Standard for Honey. Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/es/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B12-1981%252FCXS_012e.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- EU. Directive 2001/110/EC of 20 December 2001 relating to honey. Off. J. Eur. Commun. 2001, L 10, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

| Propolis Type | Region/Country | N Samples | Analytical Methods | Target Markers | Chemometrics/ML | Authentication Target | Key Outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue; Orange | Germany | 64 | HPTLC; DART-MS | Caffeic acid; Naringenin; Apigenin; Quercetin; Kaempferol; Galangin; Chrysin; Ellagic acid | PCA; HCA; LDA | Subtype discrimination | Blue type vs. Orange type discrimination | [3] |

| Poplar-type | Italy | 60 | HR-NMR | Flavonoids; Phenolic acids | Factor Analysis; General Discriminant Analysis | Harvesting method | 1H NMR (4.5–13 ppm) classified by harvesting method with 96.7% predictive capacity | [40] |

| Orange; Blue; Non-phenolic | Turkey; Serbia | 60 | HPTLC; Palynology; UV-Vis; Antioxidant assays | Quercetin; Caffeic acid; CAPE; Pinobanksin; Galangin | PCA | Subtype discrimination; Geographical origin | Orange subtype richest; Turkish vs. European | [27] |

| Orange; Blue | Turkey | 48 | UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS/MS | Chrysin; Galangin; Pinocembrin; CAPE | ANOVA | Subtype classification | Orange subtype highest phenolics | [36] |

| Poplar-type tinctures | Hungary | 252 | ICP-OES/ICP-MS | Essential/Toxic elements | Correlation analysis | Elemental QC; Geographical origin | Geographical authentication impracticable | [41] |

| Romanian poplar-type | Romania | 39 | TLC; Image Analysis | Phenolic band patterns | Fuzzy clustering; PCA | Geographical origin; Botanical origin | Meadow area vs. Forest area | [42] |

| Red propolis | Brazil | 39 | UV-Vis; HPLC-DAD; LC-MS; DPPH | Flavonoids; Isoflavonoids; Polyprenylated Benzophenones | Correlation analysis; PCA; PLS-DA; OPLS-DA | Climate effect | Climate–metabolite relationship | [43] |

| Poplar-type | Argentina | 96 | NAA | Trace minerals | PCA; LDA; kNN | Geographical origin | Elemental fingerprints for specific provenance | [10] |

| Poplar-type | Mexico | 12 | 1H-NMR; HPLC-UV-DAD | Pinocembrin; Pinobanksin; Chrysin; Galangin; Kaempferol; Quercetin; p-Coumarc acid; Naringenin | PCA; HCA | Botanical origin | Botanical sources: Populus fremontii; Ambrosia ambrosioides; Bursera laxiflora | [1] |

| Chinese poplar-type | China | 37 | nanoESI-MS; UPLC-MS/MS | Caffeic acid; p-Cinnamic acid; CAPE; Pinocembrin; Genistein; Ctric acid; Arctopicrn; Sinapinic acid; Benzoic acid; Gluconic acid; Quinic acid | PLS-DA; ANOVA; VIP Analysis; ML (RF, SVM, NN, LR, GB, SGD, Tree) | Climate-zone origin | Climate-zone and propolis-color authentication | [44] |

| Blue; Orange; Green | Egypt | 60 | HPTLC-ESI-MS; UV; Palynology | 3,4-Dimethoxycinnamic acid; Caffeic acid; Isoferulic acid; Rosmarinic acid; Quercetin | OPLS; PLS | Type discrimination; bioefficacy markers | HPTLC fingerprinting of 3 global propolis types; Palynological identification of 13 plant families | [30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastor, K.; Dolašević, S.; Nastić, N. Authentication of Propolis: Integrating Chemical Profiling, Data Analysis and International Standardization—A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244259

Pastor K, Dolašević S, Nastić N. Authentication of Propolis: Integrating Chemical Profiling, Data Analysis and International Standardization—A Review. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244259

Chicago/Turabian StylePastor, Kristian, Slobodan Dolašević, and Nataša Nastić. 2025. "Authentication of Propolis: Integrating Chemical Profiling, Data Analysis and International Standardization—A Review" Foods 14, no. 24: 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244259

APA StylePastor, K., Dolašević, S., & Nastić, N. (2025). Authentication of Propolis: Integrating Chemical Profiling, Data Analysis and International Standardization—A Review. Foods, 14(24), 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244259