Abstract

Porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns continue to serve as a cornerstone of restorative dentistry owing to their strength, affordability, and esthetics. However, late-onset complications such as oral burning and lichenoid reactions have been observed in long-serving PFMs, suggesting complex host–material interactions that extend beyond simple mechanical wear. This Perspective introduces the Nallan–Nickel Effect, a theoretical model proposing that a host- and environment-dependent threshold of bioavailable nickel ions (Ni2+), once exceeded, may trigger a neuro-immune cascade culminating in a burning phenotype. Within this framework, slow corrosion at exposed PFM interfaces releases Ni2+ into saliva and crevicular fluid, facilitating epithelial uptake and activation of innate immune sensors such as TLR4 and NLRP3. The resulting cytokine milieu (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) drives NF-κB, mediated inflammation and T-cell activation, while neurogenic mediators—including nerve growth factor (NGF), substance P, and CGRP—sensitize TRPV1/TRPA1 nociceptors, establishing feedback loops of persistent burning and neurogenic inflammation. Modifying factors such as low salivary flow, acidic oral pH, mixed-metal galvanic coupling, and parafunctional stress can lower this threshold, whereas replacement with high-noble or all-ceramic materials may restore tolerance. The model generates testable predictions: elevated local free Ni2+ levels and increased expression of TLR4 and TRPV1 in symptomatic mucosa, along with clinical improvement following substitution of nickel-containing restorations. Conceptually, the Nallan–Nickel Effect reframes PFM-associated burning and lichenoid lesions as threshold-governed, neuro-immune phenomena rather than nonspecific irritations. By integrating corrosion chemistry, mucosal immunology, and sensory neurobiology, this hypothesis offers a coherent, testable framework for future translational research and patient-centered management of PFM-related complications.

1. Background

Porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns have long been a benchmark in fixed prosthodontics because they balance durability, esthetics, and affordability [1,2,3,4,5]. While all-ceramic alternatives—especially zirconia—are increasingly popular for translucency and biocompatibility, PFMs remain widely used in cost-sensitive settings [3,4]. Their combination of a strong metallic substructure with an esthetic veneer explains their persistence in routine practice [5].

PFM crowns are supported by a metallic substructure whose composition varies by alloy class [6]. Base-metal systems commonly contain nickel, cobalt, chromium, and molybdenum: nickel adds strength but is the most frequent dental sensitizer [7,8]; cobalt contributes rigidity; chromium forms a protective oxide; and molybdenum improves resistance to pitting [9,10]. Minor elements (iron, manganese, silicon, carbon) fine-tune mechanical performance [11]. Noble and high-noble alloys incorporate greater proportions of precious metals that enhance passivity and biocompatibility (e.g., palladium for hardness/corrosion resistance; gold for corrosion resistance/ductility) [12,13,14,15].

PFM crowns remain one of the most frequently used restorative options worldwide due to their balance of strength, cost-effectiveness, and aesthetics [16,17]. However, their long-term biological impact has not been adequately addressed, particularly the delayed complications arising from gradual porcelain wear and subsequent metal ion release [18]. The emergence of persistent burning sensations and lichenoid reactions in some long-term PFM wearers represents more than a localized adverse effect, it can significantly impair oral function, patient comfort, and overall quality of life [19,20].

This article is presented as a Perspective. It synthesizes relevant mechanistic, clinical, and translational evidence to support the development of the proposed hypothesis, the Nallan–Nickel effect. References were identified through targeted searches in PubMed and Scopus using keywords such as “nickel corrosion,” “porcelain-fused-to-metal complications,” “burning mouth,” “oral lichenoid lesions,” “TLR4/NLRP3,” and “TRPV1 sensitization.” Additional references were selected based on their relevance to neuro-immune mechanisms and dental alloy biocompatibility, complemented by the authors’ expertise in periodontology, prosthodontics, and oral medicine.

Building on emerging mechanistic evidence, we introduce the concept of the Nallan–Nickel effect, a proposed hypothesis that suggests nickel ion release from exposed metallic substructures could reach a critical threshold beyond which mucosal irritation, immune sensitization, and TRPV1-mediated neurogenic activation may converge to produce persistent burning symptoms. This hypothesized effect, though not yet conclusively proven, provides a unifying explanation for the delayed onset and chronicity of symptoms in susceptible individuals. Given the global reliance on PFMs [17,21,22], especially in resource-limited settings, systematically addressing this complication is essential to raise clinical awareness, improve early detection, and guide safer restorative material selection.

In long-serving PFMs, nickel-containing Ni–Cr frameworks are most likely to lower the threshold for the Nallan–Nickel effect once porcelain thins or microfractures. Disruption of the passive film permits slow, persistent nickel release at the saliva–mucosa interface, maintaining a small pool of bioavailable Ni2+ that can drive epithelial stress and neuro-immune activation. Co-Cr removes the nickel component but can still accelerate corrosion galvanically when coupled to dissimilar metals (e.g., amalgam, high-noble posts, titanium). High-noble (Au-Pt-Pd) and titanium frameworks exhibit more stable passivation with lower galvanic drive, while all-ceramic options eliminate metal-ion exposure entirely. Clinically, Table 1 supports prioritizing all-ceramic or high-noble replacements when Nallan–Nickel Effect is suspected, avoiding mixed-metal couples in the same quadrant, and polishing/temporarily coating any unavoidable exposed metal until definitive treatment.

Table 1.

Dental alloy families and nickel relevance.

2. Clinical Concern: Long-Term Wear and Symptom Development

Despite their advantages, PFMs are not without drawbacks [28]. Over time, the porcelain layer may undergo gradual wear, chipping, or even fracture, especially in patients with parafunctional habits or heavy occlusal loads. As the veneering porcelain thins, the underlying metallic substructure becomes increasingly exposed to the oral environment. This prolonged exposure sets the stage for potential biological complications [29,30,31].

One notable clinical observation is the emergence of burning sensations in the oral cavity after years of porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crown service. The mechanism behind this phenomenon is plausibly linked to the release of metal ions from the exposed substructure [32,33]. When the veneering porcelain wears down, the underlying metallic framework comes into direct contact with saliva, dietary acids, and microbial metabolites. This interaction accelerates the corrosion of base-metal alloys such as nickel–chromium or cobalt–chromium, leading to the release of ions such as Ni2+, Co2+, and Pd2+ [29,30,34,35]. These ions may penetrate oral mucosa, irritate epithelial and subepithelial tissues, and exert cytotoxic effects. Nickel in particular is known to impair keratinocyte and fibroblast function, causing low-grade inflammation and delayed healing. In cases where multiple types of metal are present intraorally, galvanic currents may develop, further enhancing corrosion and worsening ion release [36,37].

The burning sensation experienced by patients is not only due to direct irritation but also involves neurogenic sensitization [38]. Importantly, burning mouth symptoms and lichenoid lesions in dental practice can arise from a variety of etiologies. Potential contributors include adverse reactions to metallic ions, hypersensitivity to restorative materials, microbial biofilm changes, autoimmune mucosal diseases such as lichen planus, drug-related lichenoid reactions, systemic conditions including diabetes or xerostomia, and functional pain disorders such as primary Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS) [39]. Despite careful evaluation, a substantial proportion of cases remain idiopathic, reflecting the complexity of overlapping biological, systemic, and neurological influences. This diversity of possible causes underscores the central challenge in clinical dentistry: distinguishing material-related triggers such as the hypothesized Nallan–Nickel effect from other local or systemic factors.

Metal ions are capable of activating transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, notably TRPV1, which are key mediators of noxious stimuli perception. Their activation lowers the pain threshold, creating persistent burning sensations [40]. At the same time, inflammatory mediators released as a result of corrosion—such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and prostaglandin E2, further sensitize nociceptors in the oral mucosa, amplifying pain signaling. With prolonged stimulation, both peripheral hyperalgesia and central sensitization may develop, similar to the mechanisms proposed in primary burning mouth syndrome, thereby explaining the chronicity of symptoms in some patients [41,42].

Another important factor is hypersensitivity and immunological reactivity. Nickel, palladium, and cobalt, which are frequently used in dental alloys, are well-recognized sensitizers in dentistry. With long-term exposure, some individuals develop type IV hypersensitivity, a T-cell mediated reaction [43,44]. Once sensitized, even minimal ion release can provoke exaggerated responses characterized by burning sensations, erythema, or lichenoid striations [7,43]. In many cases, this manifests as oral lichenoid contact reactions, which are clinically and histologically similar to oral lichen planus [45,46]. The proposed mechanism involves haptenization, where metal ions bind to host proteins and alter keratinocyte antigens, thereby triggering cytotoxic T-cell–driven immune damage. This process is more pronounced in older patients whose mucosal immunity is dysregulated, making them more vulnerable to hypersensitivity responses after chronic exposure [47,48].

The delayed onset of symptoms observed in these cases is consistent with a cumulative, dose-dependent, and time-dependent process. At first, the porcelain veneer acts as a protective barrier, shielding the oral environment from the underlying alloy [49,50]. Over years of occlusal wear, chipping or microfractures can occur; however, saliva gains access to the porcelain–metal interface, which enhances corrosion. Gradually, as the load of released ions increases, the biological tolerance threshold of the oral mucosa may be exceeded, leading to the onset of symptomatic burning or the development of lichenoid lesions [36,51].

3. The Nallan–Nickel Effect

We hypothesize that the most distinctive and biologically plausible trigger for burning in long-term PFM wearers is the chronic release of Ni2+ from the underlying substructure once the porcelain veneer has thinned or fractured. Nickel has long been recognized as the most frequent sensitizer in dentistry, and even at relatively low concentrations—estimated around 5–10 μg/L in saliva [52], it may act as a hapten, binding to epithelial proteins, altering keratinocyte antigens, and initiating T-cell–mediated hypersensitivity [53].

The cited threshold of 5–10 µg/L in saliva was originally reported in studies on orthodontic appliances and therefore should not be interpreted as a definitive cutoff for patients with single PFM crowns [52]. Instead, it is presented here as a hypothetical benchmark to illustrate the plausibility of a threshold-dependent response. This concentration range is consistent with sensitization data from patch testing, where nickel reactivity is observed at very low exposure levels in susceptible individuals. Moreover, in vitro studies demonstrate that neuronal TRPV1/TRPA1 channels can be activated at micromolar nickel concentrations, supporting the possibility that similar levels in saliva or crevicular fluid could contribute to epithelial stress, immune activation, and neurogenic sensitization [53]. Taken together, the 5–10 µg/L value should be understood as a conceptual anchor for the Nallan–Nickel effect hypothesis rather than a clinically validated threshold in the context of PFM restorations.

Beyond immune activation, nickel ions exert direct cytotoxic effects on keratinocytes and fibroblasts, impairing mucosal repair and promoting a state of low-grade inflammation [54]. Importantly, Ni2+ is also capable of activating TRPV1 channels, which are critical mediators of heat and nociceptive signaling [55,56]. Their activation reduces the pain threshold of oral mucosal nociceptors, thereby producing a unique burning sensation rather than nonspecific soreness or ulceration [57]. Other alloy constituents such as cobalt or palladium may contribute to hypersensitivity or lichenoid reactions, but the burning phenotype appears to be most uniquely linked to nickel exposure [58]. We therefore suggest the concept of the Nallan–Nickel effect as a threshold-dependent hypothesis, whereby cumulative nickel ion release may surpass the mucosa’s biological tolerance, initiating immune sensitization and neurogenic activation that could manifest as persistent oral burning. While not yet definitively proven, this hypothesis offers a coherent framework to explain the delayed yet characteristic onset of burning sensations in long-term PFM crown wearers and highlights nickel release as the key determinant in this clinical presentation.

Porcelain wear creates a crevice environment at the porcelain–metal interface where oxygen tension, chloride, and organic acids fluctuate [59]. In base-metal PFMs the protective Cr2O3 film passivates intermittently; microcracks and low pH (dietary acids, plaque lactic acid) drive film breakdown and mixed active–passive dissolution [60]. Galvanic microcells form between phases in the alloy and with other intraoral metals, increasing local anodic current density and preferential nickel dissolution [61]. In saliva, Ni2+ exists as aquo-complexes and as complexes with chloride, bicarbonate, thiocyanate, and thiol-rich proteins (albumin, histatins, cystatines) [62]. Protein binding prolongs mucosal residence while still allowing slow ligand exchange at epithelial surfaces, maintaining a small but persistent pool of bioavailable Ni2+—the exposure mode most compatible with delayed symptom onset in long-serving PFMs [63].

At the epithelial barrier, Ni2+ can enter keratinocytes through DMT-1/ZIP family transporters and nonspecific Ca2+ channels, and it competes at Mg2+/Zn2+ enzyme sites, disturbing cytoskeletal dynamics and tight-junction scaffolding (ZO-1/occludin), which increases paracellular permeability and facilitates deeper ion penetration [64]. Intracellular nickel perturbs mitochondria (ΔΨm loss, ATP fall), increases ROS, and shifts redox signaling toward Nrf2 and MAPK (p38/JNK/ERK) activation [65]. Although nickel is weakly redox-active, it indirectly amplifies oxidative stress via mitochondrial leakage and by inhibiting antioxidant enzymes, generating 4-HNE and related lipid aldehydes that are potent TRPA1/TRPV1 sensitizers in peripheral nociceptors [66].

Innate immune sensing provides a second amplifier. Human TLR4 can be directly engaged by Ni2+ (via histidine-dependent coordination in the TLR4/MD-2 complex), producing rapid NF-κB activation in dendritic cells and keratinocytes, with IL-1β/IL-6/TNF-α release and up-regulation of costimulatory molecules [67]. Concurrently, lysosomal stress from Ni2+ uptake triggers NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, yielding caspase-1–dependent IL-1β/IL-18 [68,69]. These cytokines both lower nociceptor thresholds and license robust antigen presentation [70]. On this background, nickel acts as a classical contact hapten, it coordinates with sulfhydryl/imidazole groups on self-proteins, creating neo-epitopes that bind MHC I/II and polarize Th1/Th17 responses. The resulting cytokine milieu (IFN-γ/IL-17A) drives lichenoid interface mucositis and sustains neurogenic inflammation [71].

The neuro-sensory component closes the loop. Ni2+ and the associated oxidative/inflammatory mediators sensitize TRPV1 and TRPA1 on peptidergic afferents; acidification and PKC/PKA signaling further potentiate channel gating [72]. Activated fibers release substance P and CGRP, causing mast-cell degranulation (histamine, tryptase) and microvascular leakage, each of which again sensitizes TRP channels and P2X3 purinoceptors [73]. Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) induced by epithelial stress promotes peripheral sprouting, converting intermittent irritation into peripheral hyperalgesia and, with time, central wind-up. This neuro-immune crosstalk explains why the dominant patient-reported phenotype is burning rather than dull pain or purely erosive lesions [74].

Nickel’s epigenetic footprint likely prolongs susceptibility. By displacing Fe2+ in JmjC histone demethylases and TET dioxygenases, Ni2+ favors H3K9 hypermethylation and DNA hypermethylation, stabilizing pro-inflammatory transcriptional programs; it also inhibits prolyl-hydroxylases, stabilizing HIF-1α, which augments nociceptor sensitivity and vascular responses [75]. Together, these changes create a tissue “memory” that makes later, smaller nickel exposures clinically expressive.

The oral ecosystem may intensify exposure. Several plaque bacteria express Ni-dependent ureases; locally elevated nickel can upregulate urease activity, generating ammonia that intermittently raises pH and re-passivates the surface—ironically reducing visual corrosion while sustaining slow Ni2+ flux [76]. Sulfur metabolites (H2S, thiols) from anaerobes chelate nickel, keeping it soluble; chloride and fluoride at low pH destabilize passive films, especially with acidulated phosphate fluoride products [77]. Low salivary flow concentrates ions, and dissimilar metals create persistent galvanic currents. These factors collectively modulate the effective dose-time integral that determines symptom risk [78].

Within this framework, the Nallan–Nickel effect is the point at which the product of (i) nickel release rate from the restoration, (ii) mucosal exposure time and permeability, and (iii) host neuro-immune sensitivity exceeds an individual tolerance boundary, tipping the system from compensated irritation to self-sustaining burning. The boundary is lowered by prior nickel sensitization, TRPV1 gain-of-function variants, aging-related barrier thinning, and inflammasome-prone genotypes; it is raised by intact saliva, neutral pH, and absence of galvanic couples. The model predicts that a similar mean salivary nickel concentration can be asymptomatic in one patient yet symptomatic in another if permeability or sensitivity terms differ—capturing the clinic’s heterogeneity without abandoning a threshold mechanism.

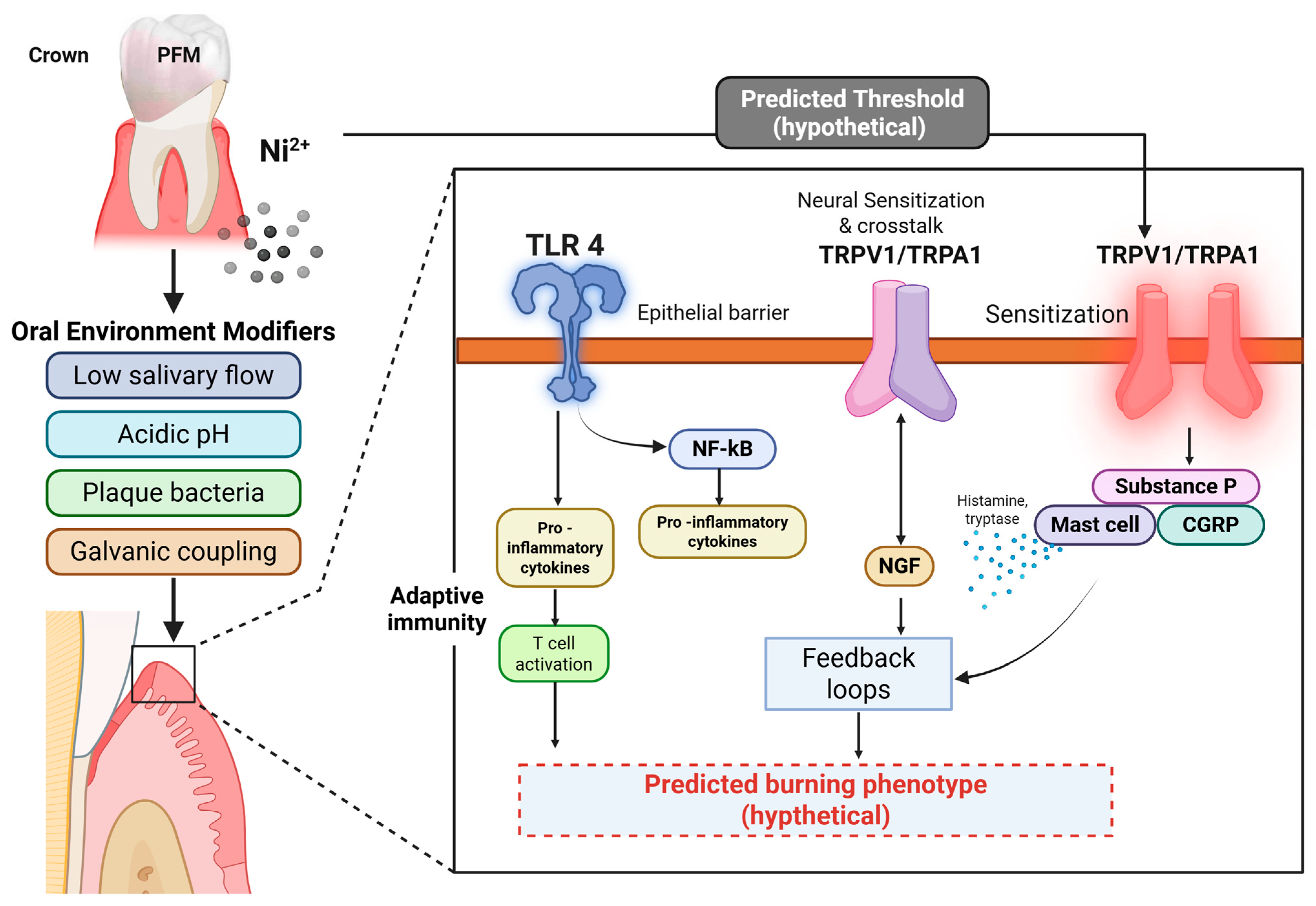

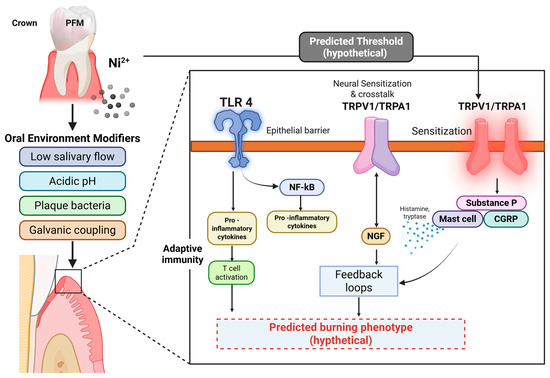

Symptomatic PFM wearers expected to show a higher free (unbound) Ni2+ fraction in saliva relative to total nickel, increased salivary IL-1β/IL-6, 8-isoprostane, NGF, SP/CGRP, and lowered GSH: GSSG. Buccal biopsies adjacent to exposed PFMs would be expected to exhibit TLR4 and TRPV1 up-regulation, NLRP3 components, and tight-junction disarray. In vitro, conditioned media from corroding Ni-Cr coupons at pH 5.5 should sensitize human oral keratinocytes and trigeminal neurons; TRPV1/TRPA1 antagonists or TLR4 blockade should attenuate this effect. These mechanistic layers—electrochemical release and speciation, epithelial entry and barrier loosening, innate/adaptive immune activation, neurogenic sensitization, and epigenetic locking provide a biologically coherent, threshold-based account of nickel’s role in PFM-associated burning, and they give the Nallan–Nickel effect both explanatory power and clear paths for validation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanistic model linking nickel ion (Ni2+) release from porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) restorations to neural sensitization and burning mouth–like symptoms (the Nallan–Nickel effect). Nickel ions liberated under adverse oral conditions—such as low salivary flow, acidic pH, bacterial plaque, or galvanic coupling—activate toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) at the epithelial interface. This activation triggers NF-κB–mediated transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promotes T-cell activation, amplifying local immune responses. Released cytokines and nerve growth factor (NGF) engage transient receptor potential channels TRPV1 and TRPA1, producing cross-talk and sensitization of peripheral nociceptors. Mast cell degranulation releases histamine and tryptase, while neuropeptides (Substance P, CGRP) sustain neurogenic inflammation and feedback loops. Together, these mechanisms lower the predicted threshold for neural activation, leading to a hypothetical burning phenotype under sustained exposure conditions. Created with Biorender.com.

Another important long-term concern with porcelain-fused-to-metal restorations is the gradual appearance of oral lichenoid lesions in the adjacent mucosa. A biologically plausible explanation is that, as the porcelain veneer wears down, the underlying metal framework becomes exposed to the oral environment, leading to slow but continuous corrosion and the release of metal ions such as nickel, palladium, or cobalt. These ions can bind to epithelial proteins and alter their surface antigens, effectively turning normal host cells into perceived foreign targets [79]. The immune system, particularly cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, responds by attacking these altered cells, resulting in a localized, cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction [80]. Clinically, this presents as white striations, erythema, or ulcerations closely resembling oral lichen planus. What makes this reaction distinctive is its chronicity and close topographic relationship with the metal-containing restoration, supporting the notion of a contact-induced lichenoid reaction rather than idiopathic lichen planus [81]. Over time, the persistence of this immune response may not only cause discomfort but also poses a small risk of malignant transformation, which underscores the importance of recognizing the potential biological trade-offs of long-term metal exposure in otherwise durable and cost-effective PFM restorations.

Systemic considerations. Although this Perspective centers on local mucosal pathways, nickel released from compromised PFMs may also contribute to systemic exposure. Swallowed Ni2+ can undergo gastrointestinal absorption and enter the bloodstream bound to proteins, with potential distant effects reported in sensitized individuals (e.g., cutaneous flares) and cytokine modulation at higher exposures [82]. While the quantities expected from a single PFM crown are likely far below occupational or dietary peaks, chronic, low-level absorption could act as an adjunctive amplifier of immune tone in predisposed patients or exacerbate comorbidities characterized by systemic inflammation. These points do not alter the local, hypothesis-driven nature of the Nallan–Nickel effect; rather, they place it within nickel’s broader toxicological profile and support cautious interpretation pending direct patient-level data.

4. Timeframe for Development of Burning Sensations or Lichenoid Lesions

The onset of burning or lichenoid reactions with PFMs is typically delayed, emerging years after placement. Early in service, the porcelain veneer acts as a barrier. With time, microfractures/chipping expose the alloy; progression then depends on alloy type, corrosion rate, and oral environment (salivary pH, dissimilar metals, diet, hygiene) [83,84,85,86].

A systematic review demonstrated that fixed orthodontic appliances significantly increase salivary nickel and chromium ion levels, with peaks typically occurring within 3–6 months after placement, followed by a gradual decline, though never to zero [87]. These fluctuations were attributed to electrochemical corrosion, mastication-related friction, and dietary or salivary influences [87]. Importantly, even though the concentrations did not usually reach toxic thresholds, the release of nickel and chromium ions was associated with hypersensitivity reactions, burning sensations, and mucosal changes in susceptible individuals [87].

This evidence dovetails directly with clinical observations in long-term PFM crown wearers, where the porcelain veneer gradually wears away, exposing the underlying metallic framework. Much like orthodontic brackets, these metal alloys undergo progressive corrosion, releasing nickel, chromium, and other ions into the oral cavity. The review strengthens this hypothesis by confirming that ion release is not just theoretical but measurable in saliva, and it correlates with clinical symptoms such as burning mouth, metallic taste, mucosal erythema, and lichenoid lesions [87].

The difference in timing between orthodontic appliances and PFMs can be plausibly explained by the nature of exposure. Orthodontic appliances present metallic surfaces that are in direct contact with saliva from the outset, resulting in an early surge of ion release that peak within months before partially stabilizing through oxide layer formation [88]. In contrast, PFMs are initially protected by their porcelain coating, which acts as a barrier to salivary contact. Only after years of occlusal wear, microfractures, or chipping does the underlying metal become exposed, initiating slow but persistent corrosion [89]. This leads to a chronic, low-grade release of nickel and chromium ions that accumulates over time [83,88]. Once ion concentrations surpass an individual’s mucosal or immunological tolerance threshold, symptoms such as burning sensations or lichenoid changes become clinically apparent. Moreover, aging-related thinning of the oral mucosa and immune dysregulation further increase susceptibility in long-term wearers [90].

Thus, while orthodontic appliances show a short- to medium-term surge in ion release, PFM crowns generate a delayed but continuous exposure that explains the late onset of burning mouth and lichenoid reactions in many patients. Taken together, both lines of evidence highlight a shared biological mechanism—metal ion penetration of mucosa, activation of epithelial and dendritic cells, and T-cell–mediated immune responses—that underlies the development of hypersensitivity and contact lichenoid reactions in susceptible individuals.

5. Individual Susceptibility

Not all patients who have long-standing PFM crowns develop burning sensations or lichenoid reactions. Susceptibility depends on several biological and environmental factors:

- Allergic Predisposition: Patients with a known sensitivity to nickel, palladium, or cobalt are at higher risk. Many cases of oral lichenoid contact reactions are essentially delayed hypersensitivity phenomena in predisposed individuals [91].

- Mucosal and Immune Status: Older individuals often show reduced mucosal barrier function and altered immune regulation, making them more vulnerable to irritation and hypersensitivity [92].

- Genetic and Epigenetic Factors: Variability in pain receptor expression (e.g., TRPV1 polymorphisms) or immune response genes may explain why some individuals develop neurogenic burning sensations while others remain asymptomatic despite similar exposures [93].

- Oral Environment: Low salivary flow, acidic oral pH, and the presence of dissimilar metals (which induce galvanic currents) all increase corrosion and ion release, thereby raising the risk of symptoms [78].

- Duration of Exposure: The longer the crown remains in service after porcelain breakdown, the greater the cumulative release of ions and the higher the risk of symptomatic manifestation [94].

6. Management of Symptoms

- When patients present with burning sensations or lichenoid lesions associated with long-term PFM crowns, the first step is careful diagnosis. A thorough history and examination should be undertaken to establish a temporal link between the onset of symptoms and the restoration. Other systemic causes of burning mouth syndrome, such as endocrine, neurological, or psychogenic disorders, should also be excluded. Patch testing for nickel, cobalt, or palladium hypersensitivity can help confirm immunological involvement [95].

- Once a prosthesis-related cause is suspected, the definitive management involves the removal or replacement of the offending PFM crown. Metal-free restorations, particularly zirconia or lithium disilicate crowns, are the preferred substitutes because they eliminate the source of ion release while providing good esthetics and strength. In situations where financial constraints or clinical limitations necessitate continued use of PFMs, selecting high-noble alloys with a higher content of gold or platinum is advisable, as these materials exhibit significantly lower corrosion rates and better biocompatibility [96].

- For patients with active mucosal lesions or burning discomfort, symptomatic relief measures may be required until replacement is carried out. Topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus) can reduce lichenoid inflammation, while topical anesthetics, clonazepam rinses, or capsaicin rinses may help attenuate burning sensations through desensitization of oral nociceptors. Strict oral hygiene maintenance, reduction in parafunctional habits, and avoidance of acidic foods or alcohol-containing mouth rinses further support mucosal healing. Importantly, patients with lichenoid lesions should be kept under regular surveillance, as these lesions carry a small but real risk of malignant transformation [97,98].

From the standpoint of the Nallan hypothesis, modifiable risk factors can be envisioned as operating along a threshold-raising strategy, where immediate measures are aimed at reducing local triggers while longer-term solutions focus on definitive replacement of the offending material. For example, porcelain thinning, microcracks, or the presence of mixed-metal galvanic pairs may lower the hypothesized nickel exposure threshold. In such situations, temporary measures such as smoothing and polishing exposed margins, using neutral rather than acidulated fluoride agents, or applying protective surface coatings may help stabilize the oral environment until replacement with nickel-free, high-noble, or all-ceramic restorations can be pursued [99].

Other influences—such as acidic dietary products, low salivary flow, or parafunctional activity—are also likely to shape nickel bioavailability and material degradation. Acidic conditions increase the proportion of free ions, reduced salivary clearance concentrates them, and excessive occlusal loading accelerates surface failure. Each of these contexts invites targeted, practical responses: dietary counseling, saliva-supportive interventions, or occlusal protection [100].

The guiding perspective is that short-term strategies may buffer against nickel release and galvanic effects, but the ultimate test of the Nallan hypothesis lies in the patient’s clinical response once the suspected source is definitively eliminated. If symptoms resolve after material change, this observation strengthens the plausibility of the proposed mechanism, while ongoing symptoms would invite reconsideration of other contributing factors.

7. Other Potential Triggers and Confounders

While nickel is emphasized as the primary suspect in the proposed Nallan–Nickel effect, it is important to recognize that other components of PFM crowns and associated factors may also contribute to adverse outcomes. Cobalt and palladium, both present in commonly used base-metal alloys, can undergo corrosion and ion release. Although their sensitization profiles differ from nickel, they may interact synergistically with nickel to amplify mucosal irritation or immune activation [101]. In particular, cobalt ions have been implicated in oxidative stress pathways, while palladium has been associated with delayed hypersensitivity reactions in sensitized individuals [102]. Additionally, microbial biofilm changes on roughened or corroded PFM surfaces may exacerbate local inflammation [103]. Altered surface chemistry can favor colonization by sulfur-producing bacteria, which generate volatile sulfur compounds that lower local pH and further accelerate alloy degradation, creating a feed-forward loop that enhances metal ion release [104].

It is also essential to differentiate the Nallan–Nickel effect from confounding clinical conditions. Co-existing BMS, a functional pain disorder, may mimic or overlap with symptoms attributed to PFMs. Likewise, systemic conditions such as diabetes, xerostomia, or nutritional deficiencies may lower mucosal thresholds and potentiate symptom expression [105]. In this Perspective, we emphasize that the Nallan–Nickel effect is a hypothesis-driven model specifically linking PFM-derived nickel exposure to burning and lichenoid lesions, but careful clinical assessment must consider alternative triggers and systemic modifiers to avoid over-attribution.

8. Differentiation from Primary Burning Mouth Syndrome and Other Lichenoid Conditions

It is important to distinguish the proposed Nallan–Nickel effect from primary Burning BMS and other causes of oral lichenoid lesions. Primary BMS is a functional pain disorder characterized by neuropathic mechanisms in the absence of identifiable local or systemic triggers [106]. In contrast, the Nallan–Nickel effect is a hypothesis-driven model that attributes burning symptoms to a threshold-dependent, local biological response to nickel ion release from porcelain-fused-to-metal restorations. Thus, while both may present with overlapping burning sensations, Nallan–Nickel effect implies a material-related trigger with potential reversibility upon crown replacement, whereas primary BMS persists independently of restorative factors.

Similarly, oral lichenoid lesions may arise from diverse etiologies such as autoimmune lichen planus, drug reactions, or idiopathic mucosal hypersensitivity [107].

Nallan–Nickel effect-related lichenoid reactions differ in that they are hypothesized to emerge specifically in the context of chronic low-level nickel exposure and local immune activation. Careful clinical evaluation, exclusion of systemic causes, and correlation with dental history are therefore essential to avoid misclassification. This comparison underscores the need for rigorous diagnostic criteria and highlights Nallan–Nickel effect as a proposed, testable mechanism rather than a universal explanation for all burning or lichenoid presentations.

9. Limitations of the Hypothesis

While the Nallan–Nickel effect provides a mechanistic framework for understanding burning sensations and lichenoid lesions in long-serving PFM crowns, it remains a hypothesis built on indirect evidence. The current model draws largely from in vitro studies, extrapolated immunological mechanisms, and observations in related conditions such as orthodontic appliances and contact hypersensitivity. Direct clinical studies specifically confirming the Nallan–Nickel effect in symptomatic PFM wearers are lacking.

Another limitation is the variability of nickel release in vivo, which depends on multiple patient-specific and environmental factors such as salivary composition, diet, and the presence of dissimilar metals. These make it difficult to establish uniform thresholds across populations. Furthermore, genetic and epigenetic predispositions, while plausible modifiers of susceptibility, have not been conclusively linked to clinical outcomes in this context.

Finally, most of the proposed pathways—such as TRPV1/TRPA1 sensitization, TLR4 activation, and NLRP3 inflammasome engagement—are supported by mechanistic plausibility but require validation in targeted experimental and translational studies. Until such direct evidence is available, the Nallan–Nickel effect should be regarded as a conceptual model that generates testable predictions rather than an established fact.

10. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Nallan–Nickel effect should be regarded as a hypothetical framework rather than a proven mechanism. The model is built primarily on indirect evidence, integrating corrosion studies, immunological pathways, and neurogenic sensitization to explain late-onset burning sensations and lichenoid lesions in long-serving PFM restorations. While this synthesis provides a biologically coherent explanation, its validity remains to be demonstrated in clinical and translational studies.

As emphasized in the section “Limitations of the Hypothesis,” the Nallan–Nickel effect must be interpreted with caution, given the absence of direct patient-level validation and the influence of multiple confounding factors such as salivary flow, galvanic coupling, and genetic predisposition. Accordingly, the model should be understood as a proposal that generates testable predictions rather than as an established clinical fact.

Ultimately, the Nallan–Nickel effect serves as a conceptual roadmap. By reframing PFM-related complications as threshold-governed, neuro-immune processes, the hypothesis invites future researchers to design rigorous mechanistic and clinical investigations. Whether validated or refuted, the Nallan–Nickel effect advances dialogue, stimulates targeted inquiry, and fosters a more precise understanding of biologically adverse outcomes associated with long-term dental restorations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C.S.K.C. and N.T.H.; methodology, N.T.H. and; validation, N.T.H., M.M.R. and R.B.; formal analysis, N.T.H.; investigation, N.C.S.K.C., V.P., M.S.I. and R.M.; resources, N.C.S.K.C.; data curation, N.T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.S.K.C. and N.T.H.; writing—review and editing, N.T.H., M.M.R., V.P., R.B. and R.M.; visualization, N.C.S.K.C., M.S.I.; supervision, M.M.R.; project administration, N.T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gallucci, G.O.; Grütter, L.; Nedir, R.; Bischof, M.; Belser, U.C. Esthetic outcomes with porcelain-fused-to-ceramic and all-ceramic single-implant crowns: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 22, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, R. A comparison of all-ceramic restorative systems: Part 2. Gen. Dent. 2000, 48, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zarone, F.; Russo, S.; Sorrentino, R. From porcelain-fused-to-metal to zirconia: Clinical and experimental considerations. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, J.G.; Cipra, D.L. Alternative crown systems: Is the metal-ceramic crown always the restoration of choice? Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1992, 36, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.D., Jr. Combining monolithic zirconia crowns, digital impressioning, and regenerative cement for a predictable restorative alternative to PFM. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2013, 34, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, H.J.; Soltvedt, B.M.; Nguyen, P.N.; Ronold, H.J.; Johnsen, G.F. Discrepancy in alloy composition of imported and non-imported porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns produced by Norwegian dental laboratories. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2020, 7, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, M. Base metal alloys used for dental restorations and implants. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 51, 603–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontana, M.; Bianchi, L.; Hansel, K.; Agostinelli, D.; Stingeni, L. Nickel allergy: Epidemiology, pathomechanism, clinical patterns, treatment and prevention programs. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 20, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehifard, E.; Ghaffari, T.; Mohammadian-Navid, S.; Ghafari-Nia, M.; Farmani, A.; Nasirpouri, F. Effect of chemical passivation on corrosion behavior and ion release of a commercial chromium-cobalt alloy. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2020, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, A.; Zakeralhosseini, R.; Moayed, M.H. An investigation on the effect of molybdenum alloy element and molybdate inhibitor on the stable and metastable pits and its correlation with the pit morphology. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 153, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajraktarova-Valjakova, E.; Korunoska-Stevkovska, V.; Kapusevska, B.; Gigovski, N.; Bajraktarova-Misevska, C.; Grozdanov, A. Contemporary dental ceramic materials: A review of chemical composition, physical and mechanical properties, and indications for use. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wataha, J.C. Biocompatibility of dental casting alloys: A review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 83, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Vermilyea, S.G.; Brantley, W.A. In vitro corrosion resistance of high-palladium dental casting alloys. Dent. Mater. 1999, 15, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant-Corroy, A.; Corne, P.; De March, P.; Fleutot, S.; Cleymand, F. Influence of recasting on the quality of dental alloys: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 205–211.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarifard, E.; Farzin, M.; Zohour Parlack, A.; Taghva, M.; Zare, R. Comparing castability of nickel-chromium, cobalt-chromium, and non-precious gold color alloys using two different casting techniques. J. Dent. 2022, 23, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brukl, C.E.; Ocampo, R.R. Compressive strengths of a new foil and porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1987, 57, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzmann, N.U.; Hagmann, E.; Weiger, R. What is the prevalence of various types of prosthetic dental restorations in Europe? Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2007, 18 (Suppl. 3), 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, A.; Arnelund, C.F.; Johansson, A. A clinical evaluation of cobalt-chromium metal-ceramic fixed partial dentures and crowns: A three- to seven-year retrospective study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2007, 98, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnazzawi, A. Effect of fixed metallic oral appliances on oral health. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2018, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, R.; Capaccio, P.; Pignataro, L.; Spadari, F. Burning mouth syndrome: The role of contact hypersensitivity. Oral Dis. 2009, 15, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Näpänkangas, R.; Haikola, B.; Oikarinen, K.; Söderholm, A.L.; Remes-Lyly, T.; Sipilä, K. Prevalence of single crowns and fixed partial dentures in elderly citizens in Finland. J. Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, L.C.; Wu, B.; Yu, L.Y.; Wang, X.P.; Liu, Y. A comparative analysis of metal allergens associated with dental alloy prostheses and the expression of HLA-DR in gingival tissue. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C. Evaluation of marginal and internal gaps of Ni–Cr and Co–Cr alloy copings manufactured by microstereolithography. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosgogeat, B.; Vaicelyte, A.; Gauthier, R.; Janssen, C.; Le Borgne, M. Toxicological risks of cobalt–chromium alloys in dentistry: A systematic review. Materials 2022, 15, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majerič, P.; Lazić, M.M.; Mitić, D.; Lazić, M.; Lazić, E.K.; Vastag, G.; Anžel, I.; Lazić, V.; Rudolf, R. The thermomechanical, functional and biocompatibility properties of a Au–Pt–Ge alloy for PFM dental restorations. Materials 2023, 17, 5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, J.; Rylska, D.; Januszewicz, B.; Konieczny, B.; Cichomski, M.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Radwanski, M.; Sokolowski, J.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Corrosion resistance of titanium dental implant abutments: Comparative analysis and surface characterization. Materials 2023, 16, 6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succaria, F.; Morgano, S.M. Prescribing a dental ceramic material: Zirconia vs lithium-disilicate. Saudi Dent. J. 2011, 23, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imirzalioglu, P.; Alaaddinoglu, E.; Yilmaz, Z.; Oduncuoglu, B.; Yilmaz, B.; Rosenstiel, S. Influence of recasting different types of dental alloys on gingival fibroblast cytotoxicity. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2012, 107, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hassan, M.I.; Abu-Hammad, O.A.; Harrison, A. Stress distribution associated with loaded ceramic onlay restorations with different designs of marginal preparation: An FEA study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2000, 27, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zhong, Q. Corrosion of dental alloys in artificial saliva with Streptococcus mutans. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e017444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, G.; Garhammer, P. Biological interactions of dental cast alloys with oral tissues. Dent. Mater. 2002, 18, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, I.; Makarov, N.A.; Thoma, D.S.; Zwahlen, M.; Pjetursson, B.E. All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part I: Single crowns (SCs). Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, M.; Huang, M.; Wang, C.; Hung, C.; Chen, C. Survival assessment of fractured porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns surface roughened by sandblasting and repaired by composite resin after in vitro thermal fatigue. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilhan, H.; Bilgin, T.; Cakir, A.F.; Yuksel, B.; Von Fraunhofer, J. The effect of mucine, IgA, urea, and lysozyme on the corrosion behavior of various non-precious dental alloys and pure titanium in artificial saliva. J. Biomater. Appl. 2007, 22, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljak-Guberina, R.; Knezović-Zlatarić, D.; Katunarić, M. Dental alloys and corrosion resistance. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2002, 36, 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeda-Zayas, A.; Menendez Lopez-Mateos, L.; Palma-Fernández, J.C.; Iglesias-Linares, A. Assessment of metal ion accumulation in oral mucosa cells of patients with fixed orthodontic treatment and cellular DNA damage: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, D.; Mondello, M.R.; Cimino, F.; Cristani, M.; Pergolizzi, S.; Saija, A. Toxic effect of nickel in an in vitro model of human oral epithelium. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 159, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, S.D. Burning Mouth Syndrome. In Atlas of Uncommon Pain Syndromes, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ditrichova, D.; Kapralova, S.; Tichy, M.; Ticha, V.; Dobesova, J.; Justova, E.; Eber, M.; Pirek, P. Oral lichenoid lesions and allergy to dental materials. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2007, 151, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Szallasi, A. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels: A clinical perspective. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2474–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, H.A.; Chen, A.; Kravatz, N.L.; Chavan, S.S.; Chang, E.H. Involvement of neural transient receptor potential channels in peripheral inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 590261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y. The dual role of TRPV1 in peripheral neuropathic pain: Pain switches caused by its sensitization or desensitization. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1400118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, J.; Scheper, R.J.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Rustemeyer, T.; Feilzer, A.J. Palladium-based dental alloys are associated with oral disease and palladium-induced immune responses. Contact Dermat. 2014, 71, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrolvaezin, A.; Pezhman, A.; Zare, I.; Nasab, S.Z.; Chamani, S.; Naghizadeh, A.; Mostafavi, E. Systemic allergic contact dermatitis to palladium, platinum, and titanium: Mechanisms, clinical manifestations, prevalence, and therapeutic approaches. MedComm 2023, 4, e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrbova, R.; Podzimek, S.; Himmlova, L.; Roubickova, A.; Janovska, M.; Janatova, T.; Bartos, M.; Vinsu, A. Titanium and other metal hypersensitivity diagnosed by MELISA® test: Follow-up study. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5512091. [Google Scholar]

- Muris, J.; Goossens, A.; Gonçalo, M.; Bircher, A.J.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Foti, C.; Rustemeyer, T.; Feilzer, A.J.; Kleverlaan, C.J. Sensitization to palladium and nickel in Europe and the relationship with oral disease and dental alloys. Contact Dermat. 2015, 72, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipinda, I.; Hettick, J.M.; Siegel, P.D. Haptenation: Chemical reactivity and protein binding. J. Allergy 2011, 2011, 839682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizawa, T.; Kumagai, K.; Matsubara, R.; Nasu, K.; Kitaura, K.; Suzuki, M.; Hamada, Y.; Suzuki, R. Characterization of metal-specific T-cells in inflamed oral mucosa in a novel murine model of chromium-induced allergic contact dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tian, B.; Wei, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; He, L.; Zhang, S. Investigation of the time-dependent wear behavior of veneering ceramic in porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns during chewing simulations. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 40, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazzawi, T.F. Clinical survival rate and laboratory failure of dental veneers: A narrative literature review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, J.; Podzimek, S.; Tomka, M.; Kucerová, H.; Mihaljevic, M.; Hána, K.; Miksovský, M.; Sterzl, I.; Vinsová, J. Metal alloys in the oral cavity as a cause of oral discomfort in sensitive patients. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2006, 27 (Suppl. 1), 53–58, Erratum in Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2007, 28, iii. [Google Scholar]

- Quadras, D.D.; Krishna Nayak, U.S.; Kumari, N.S.; Priyadarshini, H.R.; Gowda, S.; Fernandes, B. In vivo study on the release of nickel, chromium, and zinc in saliva and serum from patients treated with fixed orthodontic appliances. Dent. Res. J. 2019, 16, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Arakaki, R.; Yamada, A.; Tsunematsu, T.; Kudo, Y.; Ishimaru, N. Molecular mechanisms of nickel allergy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.; Wood, E.J. Exposure of human keratinocytes and fibroblasts in vitro to nickel sulphate ions induces synthesis of stress proteins Hsp72 and Hsp90. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2000, 80, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuba, Y.M. Beyond neuronal heat sensing: Diversity of TRPV1 heat-capsaicin receptor-channel functions. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 612480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbert, M.; Radtke, D.; Wodarski, R.; Damann, N.; Hatt, H.; Wetzel, C.H. Direct activation of transient receptor potential V1 by nickel ions. Pflügers Arch. 2010, 459, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, W.D., Jr. The role of TRPV1 receptors in pain evoked by noxious thermal and chemical stimuli. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 196, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, F.; Sakurai, J.; Shimizu, R.; Kayamori, K.; Harada, H. Oral lichenoid contact lesions related to dental metal allergy may resolve after allergen removal. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 17, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, N. Corrosion of metallic biomaterials: A review. Materials 2019, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, J.; Lohrengel, M. Stability, reactivity and breakdown of passive films: Problems of recent and future research. Electrochim. Acta 2000, 45, 2499–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinaric, M.R.; Kanizaj, L.; Zuljevic, D.; Katic, V.; Spalj, S.; Curkovic, H.O. Effect of oral antiseptics on the corrosion stability of nickel–titanium orthodontic alloys. Mater. Corros. 2018, 69, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, E.; Bonna, A.; Goch, G.; Bal, W. Salivary histatin-5, a physiologically relevant ligand for Ni(II) ions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011, 105, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.; Benet, L. An examination of protein binding and protein-facilitated uptake relating to in vitro–in vivo extrapolation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 123, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Uda, M.; Hirose, Y.; Hirai, Y. Restoration of calcium-induced differentiation potential and tight junction formation in HaCaT keratinocytes by functional attenuation of overexpressed high mobility group box-1 protein. Cytotechnology 2020, 72, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyachor, C.P.; Dooka, D.B.; Orish, C.N.; Amadi, C.N.; Bocca, B.; Ruggieri, F.; Senofonte, M.; Frazzoli, C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Mechanistic considerations and biomarker levels in nickel-induced neurodegenerative diseases: An updated systematic review. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 13, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germande, O.; Ducret, T.; Quignard, F.; Deweirdt, J.; Freund-Michel, V.; Errera, H.; Cardouat, G.; Vacher, P.; Muller, B.; Berger, P.; et al. NiONP-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment in an in vitro pulmonary vascular cell model mimicking endothelial dysfunction. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, M.; Zdyb, K.; Medici, S.; Pelucelli, A.; Simula, G.; Gumienna-Kontecka, E.; Zoroddu, M.A. Ni(II) interaction with a peptide model of the human TLR4 ectodomain. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 44, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to metals. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1055788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, J.; Blander, J.M. Increasing complexity of NLRP3 inflammasome regulation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 109, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, V.S.; Daniels, M.J.D.; Palazón-Riquelme, P.; Dewhurst, M.; Luheshi, N.M.; Rivers-Auty, J.; Green, J.; Redondo-Castro, E.; Kaldis, P.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; et al. The three cytokines IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-1α share related but distinct secretory routes. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 8325–8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masjedi, K.; Bruze, M.; Ahlborg, N. T-helper 22 cell type responses to nickel in contact allergic subjects are associated with T-helper 1, T-helper 2, and T-helper 17 cell cytokine profile responses and patch test reactivity. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 184, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouin, O.; Lebonvallet, N.; Gall-Ianotto, C.L.; Sakka, M.; Buhé, V.; Plée-Gautier, E.; Carré, L.; Lefeuvre, L.; Misery, L.; Le Garrec, R. TRPV1 and TRPA1 in cutaneous neurogenic and chronic inflammation: Pro-inflammatory response induced by their activation and sensitization. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Guo, Z.; Sun, Y.; Kingery, W.S.; Clark, J.D. Substance P signaling controls mast cell activation, degranulation, and nociceptive sensitization in a rat fracture model of complex regional pain syndrome. Anesthesiology 2012, 116, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Shi, X.; Liao, T.; Jie, L.; Yu, L.; Wang, P. NGF signaling exacerbates KOA peripheral hyperalgesia via increased TRPV1-labeled synovial sensory innervation in KOA rats. Pain Res. Manag. 2024, 2024, 1552594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, C.C.; Wang, Z.; Tanwar, V.S.; Zhang, X.; Zang, C.; Cuddapah, S. Nickel-induced transcriptional changes persist post exposure through epigenetic reprogramming. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morou-Bermudez, E.; Elias-Boneta, A.; Billings, R.; Burne, R.; Garcia-Rivas, V.; Brignoni-Nazario, V.; Suarez-Perez, E. Urease activity in dental plaque and saliva of children during a three-year study period and its relationship with other caries risk factors. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Shi, S.; Dai, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, X. Corrosion mechanisms of nickel-based alloys in chloride-containing hydrofluoric acid solution. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepelova, N.; Antoshin, A.; Voloshin, S.; Usanova, A.; Efremov, Y.; Makeeva, M.; Evlashin, S.; Stepanov, M.; Turkina, A.; Timashev, P. Oral galvanism side effects: Comparing alloy ions and galvanic current effects on the mucosa-like model. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, Z.; Vlahova, A.; Zlatev, S.; Stoeva, I.; Tomov, D.; Davcheva, D.; Hadzhigaev, V. Clinical evaluation of corrosion resistance, ion release, and biocompatibility of CoCr alloy for metal-ceramic restorations produced by CAD/CAM technologies. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, M.; Mohaideen, K.; Sennimalai, K.; Gothankar, G.S.; Arora, G. Effect of oral environment on contemporary orthodontic materials and its clinical implications. J. Orthod. Sci. 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, V.V.; Setlur, K.; Yerlagudda, K. Oral lichenoid lesions—A review and update. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, F.; Curato, C.; Thierse, H.; Siewert, K.; Luch, A. Immunological mechanisms of metal allergies and the nickel-specific TCR–pMHC interface. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M. Fracture reasons in ceramic-fused-to-metal restorations. J. Oral Rehabil. 2003, 30, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakelyan, M.; Spagnuolo, G.; Iaculli, F.; Dikopova, N.; Antoshin, A.; Timashev, P.; Turkina, A. Minimization of adverse effects associated with dental alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 7476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsel, R.P.; Lin, D. Retrospective analysis of porcelain failures of metal–ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures supported by 729 implants in 152 patients: Patient-specific and implant-specific predictors of ceramic failure. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2009, 101, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farga-Niñoles, I.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Román-Rodríguez, J.L.; Solá-Ruíz, M.F.; Granell-Ruíz, M.; Fons-Font, A. Fractographic study of the behavior of different ceramic veneers on full coverage crowns in relation to supporting core materials. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2013, 5, e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imani, M.M.; Mozaffari, H.R.; Ramezani, M.; Sadeghi, M. Effect of fixed orthodontic treatment on salivary nickel and chromium levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Tikku, T.; Khanna, R.; Maurya, R.P.; Verma, G.; Murthy, R.C. Release of nickel and chromium ions in the saliva of patients with fixed orthodontic appliance: An in-vivo study. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, M.; Zeman, F.; Baitinger, T.; Galler, J.; Koller, M.; Handel, G.; Rosentritt, M. The clinical performance of porcelain-fused-to-metal precious alloy single crowns: Chipping, recurrent caries, periodontitis, and loss of retention. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 27, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M.S.; Singh, T.; Zakeri, G.; Hung, M. Oral health and older adults: A narrative review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.M.; Agrawal, M.R.; Chougule, S.A.; Mistry, J.D. Oral lichenoid reaction due to nickel alloy contact hypersensitivity. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013009754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, L.; Xie, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F. Mucosal immune response in biology, disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, N.; Okumura, M.; Tadokoro, O.; Sogawa, N.; Tomida, M.; Kondo, E. Effect of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in TRPV1 on burning pain and capsaicin sensitivity in Japanese adults. Mol. Pain 2018, 14, 1744806918804439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawthan, M.; Chrcanovic, B.R.; Larsson, C. Retrospective clinical study of tooth-supported single crowns: A multifactor analysis. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 130, e12871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberdi-Navarro, J.; Aguirre-Urizar, J.M.; Ginestal-Gómez, E. Clinical presentation of burning mouth syndrome in patients with oral lichenoid disease. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2020, 25, e805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarone, F.; Di Mauro, M.I.; Ausiello, P.; Ruggiero, G.; Sorrentino, R. Current status on lithium disilicate and zirconia: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, M.B. Rationale for the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in the management of oral lichen planus and mucosal inflammatory diseases. Cureus 2024, 16, e74570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utz, S.; Suter, V.; Cazzaniga, S.; Borradori, L.; Feldmeyer, L. Outcome and long-term treatment protocol for topical tacrolimus in oral lichen planus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wylie, C.M.; Shelton, R.M.; Fleming, G.J.; Davenport, A.J. Corrosion of nickel-based dental casting alloys. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, Y.; Sakira, A.K.; Ouédraogo, M.; Tapsoba, I.; Konsem, T.; Beugré, J.B. Influence of pH on the release of nickel ions from fixed orthodontic appliances in artificial saliva. J. Orthod. Sci. 2024, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonefeld, C.M.; Nielsen, M.M.; Vennegaard, M.T.; Johansen, J.D.; Geisler, C.; Thyssen, J.P. Nickel acts as an adjuvant during cobalt sensitization. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, R.; Moelijker, N.; Hendriks, G.; Brandsma, I. A tiered approach to investigate the inhalation toxicity of cobalt substances. Tier 2b: Reactive cobalt substances induce oxidative stress in ToxTracker and activate hypoxia target genes. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 129, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, D.; Váchová, L.; Palková, Z. Hostile environments: Modifying surfaces to block microbial adhesion and biofilm formation. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.T.; Kannoorpatti, K.; Padovan, A.; Thennadil, S. Effect of pH regulation by sulfate-reducing bacteria on corrosion behaviour of duplex stainless steel 2205 in acidic artificial seawater. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 200639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadhini, E.N. Burning tongue and taste alteration in xerostomic undiagnosed diabetic patients with vitamin D deficiency. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, T. Burning mouth syndrome. Rev. Pain 2011, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binnie, R.; Dobson, M.L.; Chrystal, A.; Hijazi, K. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid lesions—Challenges and pitfalls for the general dental practitioner. Br. Dent. J. 2024, 236, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).