Abstract

In this study, we present a new, facile, and eco-friendly approach to the synthesis of silver nanoparticles using an aqueous extract obtained from wasted goat bone, which acted as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Hydroxyapatite (GHAP) derived from the same biogenic source was then added to the Ag-NPs solution, resulting in the formation of a nanocomposite (Ag@GHAP). Biogenic GHAP and Ag@GHAP have been characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), dynamic light scattering (DLS), zeta potential, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), confirming the formation of crystalline GHAP with well-dispersed silver nanoparticles. According to AFM studies, the Ag@GHAP composite exhibits a higher surface roughness alteration than GHAP. XRD revealed that the crystalline sizes of GHAP and Ag@GHAP are 10.2 and 15.6 nm, respectively. Zeta potential showed that GHAP and Ag@GHAP possessed values of −12.4 and −11.7 mV, respectively. Ag@GHAP showed a promising performance in photocatalysis and antioxidant applications as compared to GHAP. The energy band gap (Eg) values are 5.1 eV and 4.5 eV for GHAP and Ag@GHAP, respectively. Ag@GHAP showed photocatalytic activity during the degradation of methylene blue dye (5 ppm) under solar irradiation with a removal efficiency of 99.15% in 100 min at the optimum conditions. The antioxidant activity of GHAP and Ag@GHAP was determined using the DPPH method. The results showed enhanced antioxidant activity of a silver decorated sample with IC50 values of 36.83 and 2.95 mg/mL, respectively. As a result, the Ag@GHAP composite is a promising candidate in environmental treatment and scavenging of free radicals.

1. Introduction

Hydroxyapatite fabricated from natural resources has gained increasing interest owing to its biocompatibility and versatility; thus, animal bone waste is used for the production of hydroxyapatites, which have recently attracted more attention because of their remarkable characteristics [1]. Hydroxyapatite, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, is one of the most common bioceramics used in biomedical applications, which is specifically used for regrowing bones and as a hard tissue substituted material [2]. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles are considered a valuable material applicable to different applications due to their stability, insolubility, resistance to heat and mechanical change, and lack of impact from moisture [3]. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles are used in several vital fields such as odontology, orthopedics, biomedical engineering, and drug delivery [4], as well as many environmental treatments [5]. It has been reported that hydroxyapatite nanoparticles can speed up healing and recovery because they can seamlessly integrate with human tissue due to their biocompatibility [6].

Although hydroxyapatite can be produced synthetically or naturally, natural materials are the most advantageous and economical [7]. For the synthetic production of the pure hydroxyapatite phase, each method needs several handling parameters, including pH adaptation, temperature, pressure, and the molar ratio of calcium and phosphate precursors. The general methods for the synthesis of hydroxyapatite include dry, wet, and high-temperature methods [8]. Dry methods are carried out by solid state [9] or mechanochemical techniques [10]. Wet methods are implemented via chemical precipitation [11], hydrothermal [12], or hydrolysis techniques [13]. High temperature methods are achieved by combustion [14] or pyrolysis techniques [15]. While these techniques are widely used to synthesize hydroxyapatite nanoparticles, only a small percentage of them provide satisfactory economics or performance. This is mainly because the synthesis involves extensive factors and is an expensive, complex process [16]. Thus, the extraction of hydroxyapatite from natural resources is the most feasible and economical option [17]. This could enhance the hydroxyapatite synthesis as well as waste recycling. Animal scales, teeth, and bones, the precursor of hydroxyapatite, are a good source for its fabrication [18].

Water recycling using materials derived from food waste recovery is important for environmental treatment because it addresses two environmental challenges simultaneously. Also, it is an effective, economic, and simple strategy in environmental protection. Biogenic hydroxyapatite composites have been used as photocatalysts in wastewater treatment, such as the use of marine shell residues–hydroxyapatite/Nb2O5 in photocatalytic removal of organic dyes under sunlight [19], Anadara granosa–hydroxyapatite/Ag3PO4 in photocatalytic removal of Rhodamine-B under visible light [20], and cow bone–hydroxyapatite/MnFe2O4 in photocatalytic removal of methylene blue under visible light [21].

Hydroxyapatite is considered an insulator due to its wide band gap. However, the incorporation of hydroxyapatite into composite structures with plasmonic materials can enhance its semiconducting properties, thus enhancing its functional photocatalytic behavior [22]. One of the most effective methods to enhance the light absorption and photocatalytic performance of wide-band gap materials is the incorporation of Ag-NPs, which is mostly attributed to the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of Ag-NPs, enabling strong absorption in both visible and near-UV light regimes, with the generation of highly energetic localized electromagnetic fields [23]. These plasmon-induced charge carriers may help charge transfer processes or facilitate the generation of hot electrons, thus enabling more efficient separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and suppressing their recombination, which improve the photocatalytic properties of the loaded material under solar irradiation even if the semiconductor possesses a relatively large band gap and limited intrinsic light absorption.

This study is devoted to the biogenic fabrication of Ag-NPs hydroxyapatite obtained from goat bone wastes, and to the dedicated structural characterization obtained via XRD, FTIR, SEM, DLS, AFM, and zeta potential, highlighting a possible role in photocatalytic and anti-oxidant applications.

2. Results and Discussion

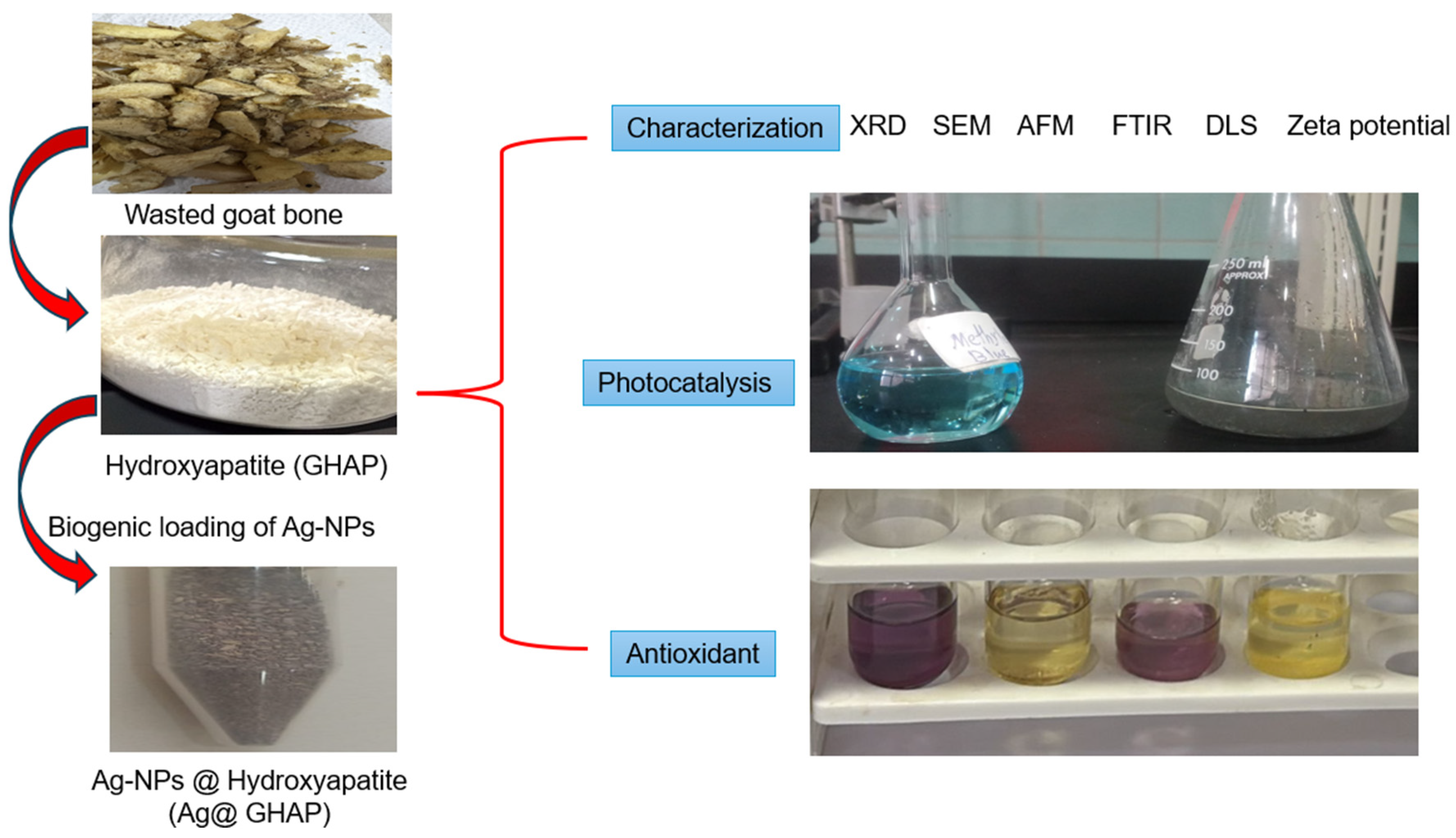

The goal of this work is the harnessing of goat bone waste. The gel obtained from the aqueous extract of goat bone was used for the green synthesis of Ag-NPs for the first time, subsequently loaded with hydroxyapatite produced from the heat treatment of goat bone. The physicochemical characteristics, photocatalytic activity, and antioxidant capacity applications of uncoated and Ag NPs-coated hydroxyapatite were studied, Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Biogenic synthesis, characterization and applications of GHAP and Ag@GHAP.

2.1. Characterization of GHAP and Ag@GHAP

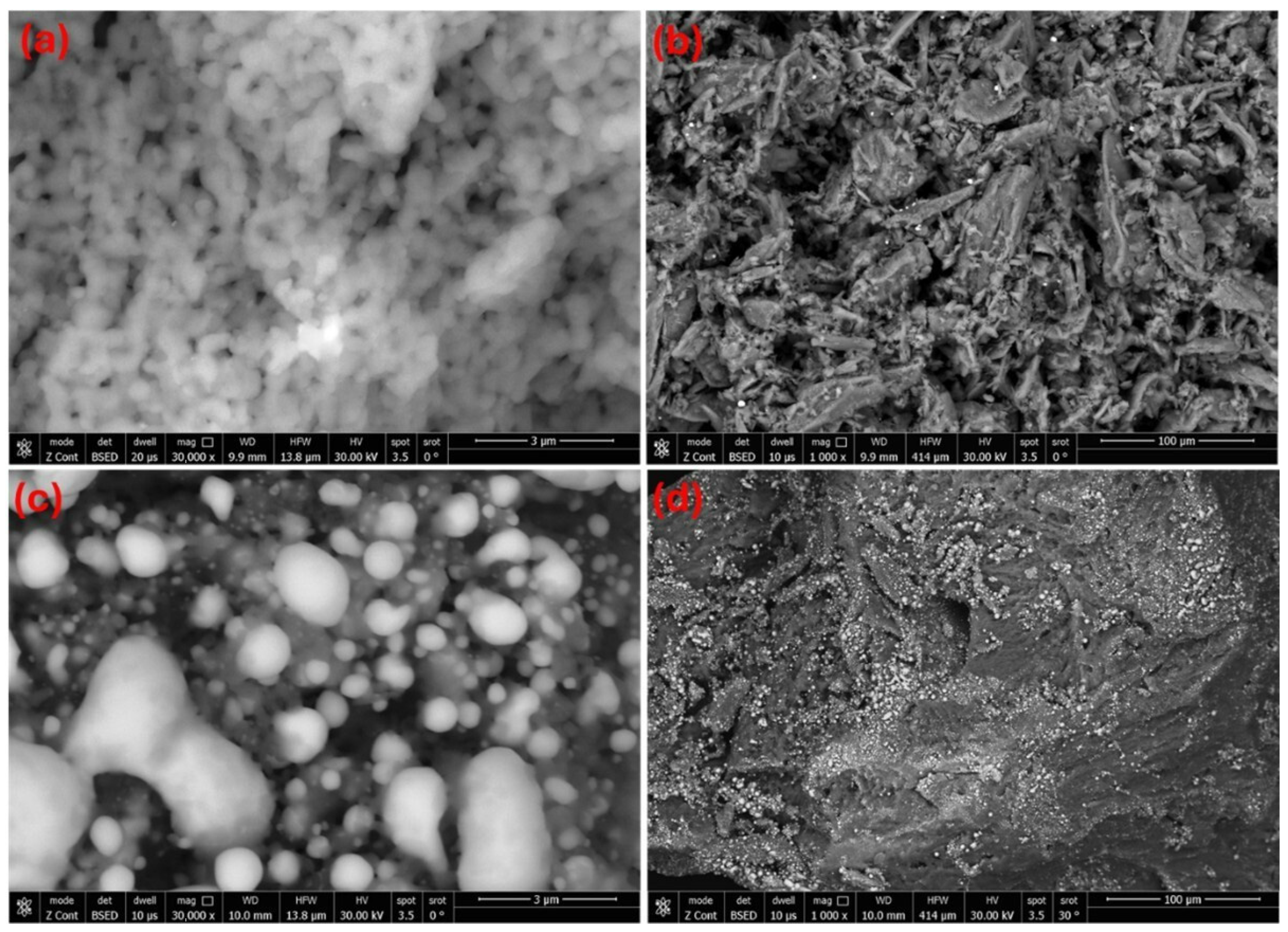

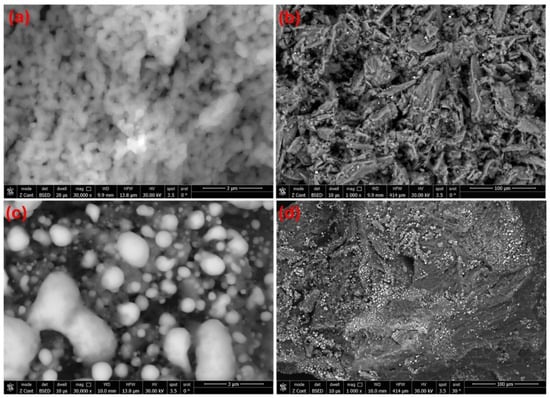

2.1.1. SEM Analysis

Figure 1 shows the SEM images of GHAP and Ag@GHAP at different magnifications (3 µm and 100 µm), as shown, respectively, in Figure 1a,b for GHAP. Figure 1c,d show the same magnifications for the Ag@GHAP. The hydroxyapatite has grains that interlock to create a porous structure, as shown in Figure 1a, and these grains appear as rod shapes. For higher magnifications, as shown in Figure 1b, the crystallites show gaps between agglomerates, which demonstrates its suitability as a biomedical covering due to its larger surface area [24]. The form and porosity of the nanostructure enable cells to join, which is the reason for the structural shape, as shown by the nanoscale needle-like grains at higher magnification after combining the pure hydroxyapatite with silver nanoparticles (Ag@GHAP).

Figure 1.

SEM images of (a) GHAP with magnification 3 µm, (b) GHAP with magnification 100 µm, (c) Ag@GHAP with magnification 3 µm, and (d) Ag@GHAP with magnification 100 µm.

The SEM images reveal the surface morphological changes. At a low magnification (3 µm), the grains are more uniformly dispersed, as shown in Figure 1c, and the silver nanoparticles appear to have a spherical shape. At higher magnifications (100 µm), the Ag nanoparticles appear as brilliant spots, as shown in Figure 1d. The denser porous confirmed the composition structure of the fabricated Ag@GHAP composite. The presence of Ag nanoparticles on the GHAP caused morphological changes in the particles, which is advantageous for photocatalyst and biomedical effects. On the other hand, the SEM images of the Ag@GHAP composite reveal a uniform structure with shiny dots under a bright microscope [25]. The SEM images showed that the fabricated Ag@GHAP composite could be applied in biomedical coatings and photocatalyst applications.

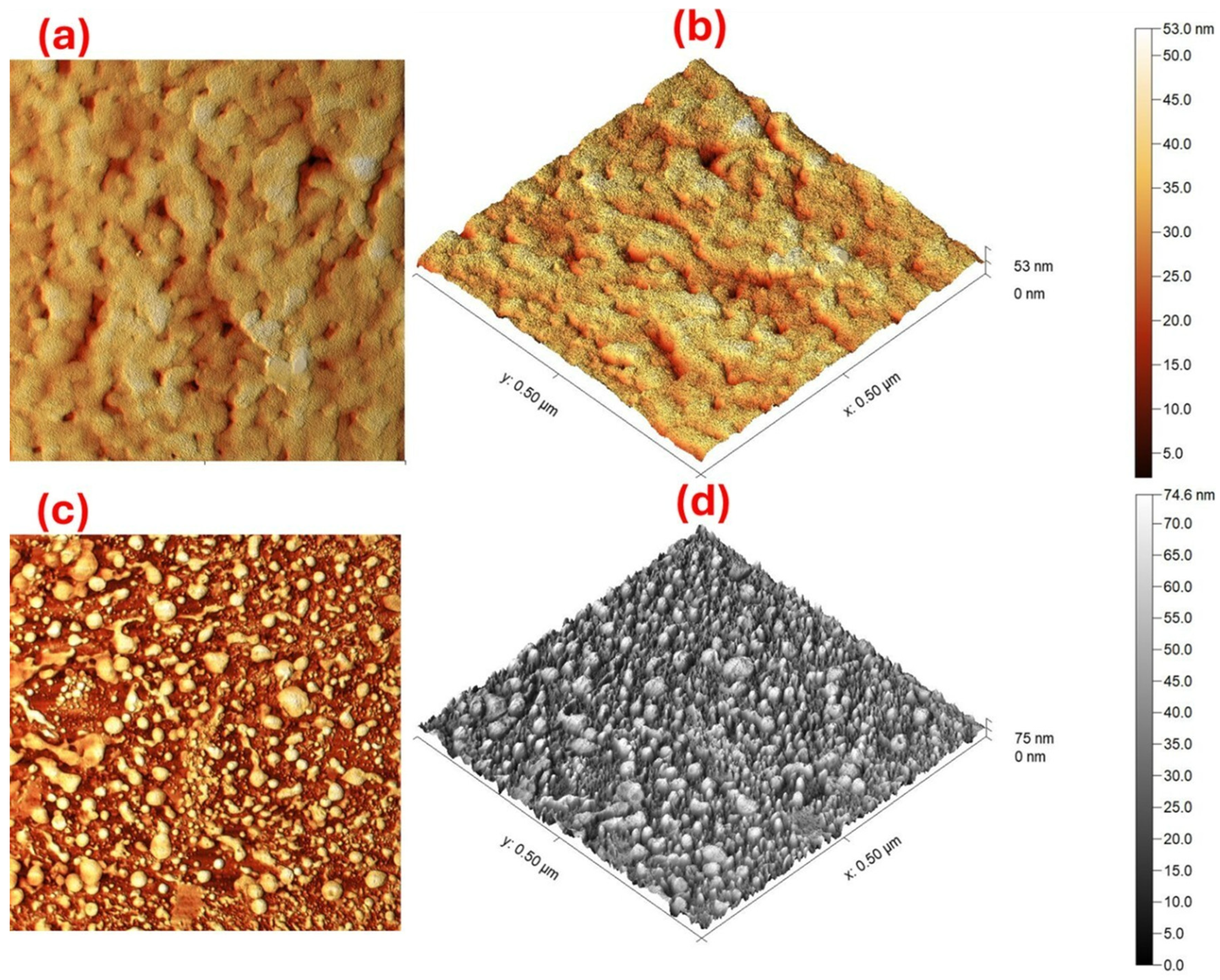

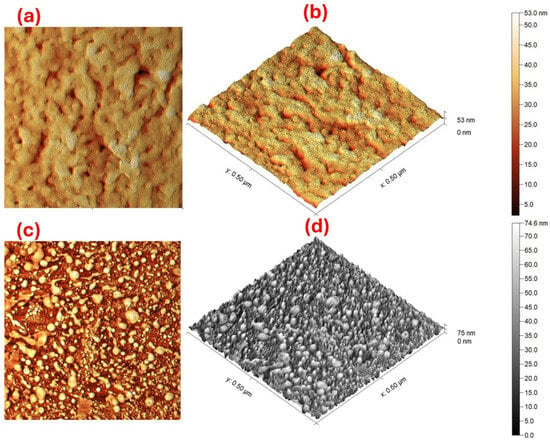

2.1.2. AFM Analysis

Figure 2 shows AFM micrographs of 2D and 3D surface scans of pure hydroxyapatite GHAP and the composite Ag@GHAP. Figure 2a shows the 2D images of pure GHAP, which indicate agglomerated nanoparticles and clusters of particles. The higher grains in the lighter parts with the lower grains in the darker region confirm the surface modification of the composites [26]. Figure 2b, for the 3D dimensions of GHAP, provides the more porous structure, surface height changes, and morphology shape. The data of AFM shows that the average root-mean-square roughness (RMS) of GHAP is nearly 4.98 nm. Also, the significant differences between deep voids and elevated grain clusters with nanoscale roughness confirm the increasing surface area of the fabricated composite [27].

Figure 2.

AFM images of the (a) 2D of GHAP, (b) 3D of GHAP, (c) 2D of Ag@GHAP, and (d) the 3D of Ag@GHAP.

The 2D and 3D AFM images of the composite (Ag@GHAP) are shown, respectively, in Figure 2c,d. The images appeared as a homogenous grain distribution with small AgNPs over the GHAP matrix. Also, the surface of the material (Ag@GHAP) seems denser in height than in the pure GHAP. The RMS roughness of the composite (Ag@GHAP) is nearly 12.97 nm, suggesting that it has a more uniform distribution. The changes in the surface roughness by the addition of the AgNPs confirm the improvement of the mechanical properties of the fabricated composite for the photocatalyst applications and the functional antibacterial activity [28]. The AFM indicates the surface roughness is modified for the composite Ag@GHAP; this is because AgNPs cover the most space which reduced the surface gaps. The AFM data shows the well-defined and uniform nanoscale morphology of GHAP and Ag@GHAP, proving that they have suitable structural requirements for applications in biomedical coatings and photolysis.

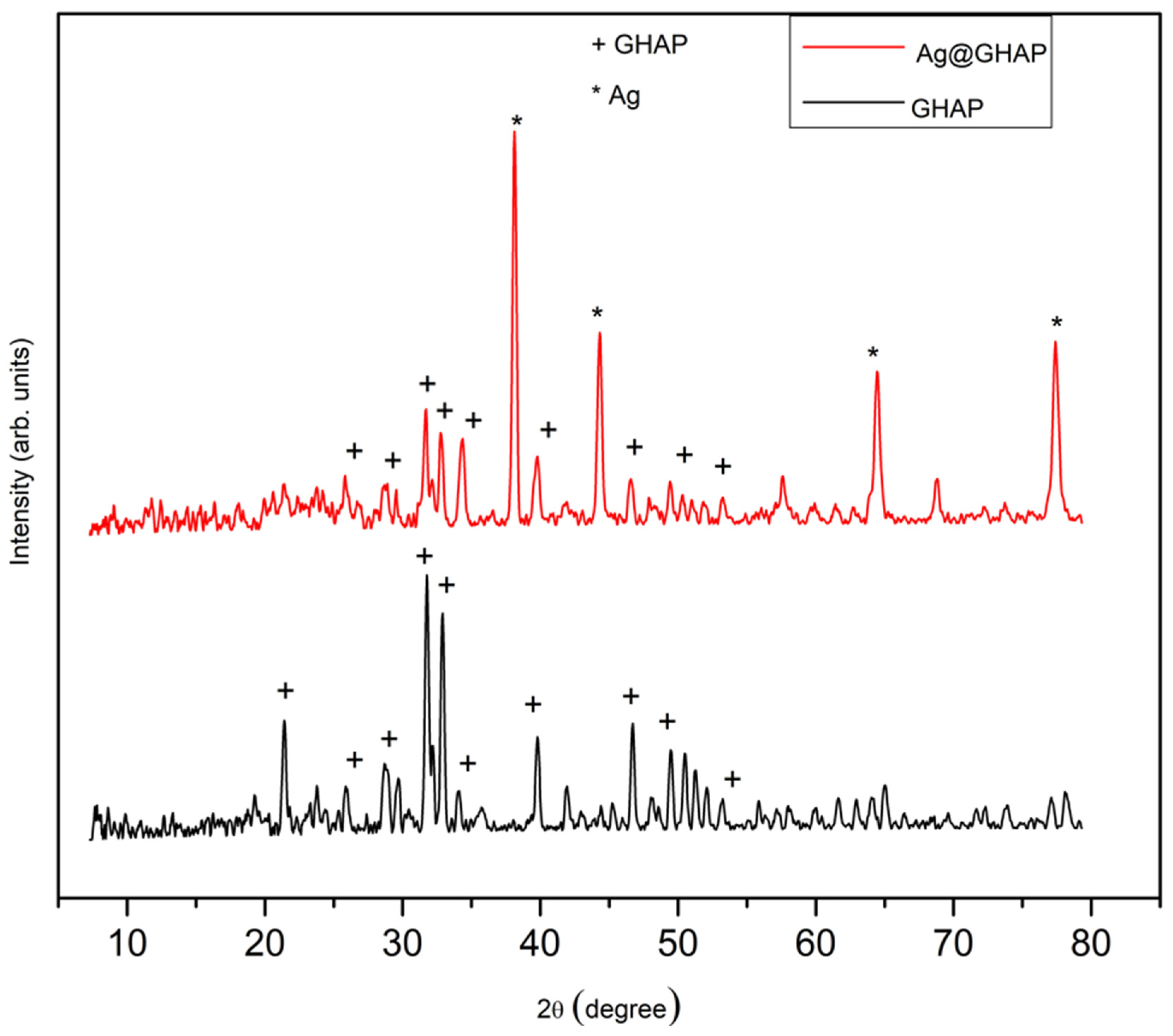

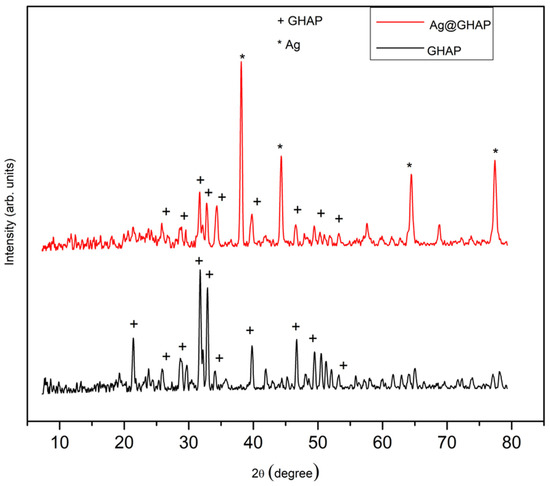

2.1.3. Powder XRD Analysis

Powder XRD spectra were shown in Figure 3. The XRD of GHAP indicates a crystalline shape. The GHAP diffraction peaks appeared at 2θ of 26°, 28°, 31.75°, 32.31°, 33.87°, 39.82°, 46.8°, 49.5°, and 53° correspond to the (002), (210), (211), (112), (300), (310), (222), (213), and (004) crystallographic planes, respectively [29]. These peaks show that the production of pure GHAP was successful. The sharpness peak intensities demonstrate that hydroxyapatite is highly crystalline. The XRD results suggest that one of the GHAP characteristics is high crystalline, which is more favorable to bioactivity and photocatalysis applications [30].

Figure 3.

Powder XRD spectra of GHAP and Ag@GHAP.

The powder XRD spectrum of Ag@GHAP reported in Figure 3 shows the mixture of hydroxyapatite and silver nanoparticles, confirming the AgNPs in the GHAP surface. The diffraction peaks of the Ag@GHAP contain the peaks of the GHAP and additional silver peaks at 2θ of 38.9°, 45.1°, 65.2°, and 78.12°, that correspond, respectively, to (111), (200), (220), and (311) [31]. The presence of both peaks for Ag and GHAP confirm the successful formation of ANPs on the AGHAP surface. The structural modification of the composite showed by powder-XRD analysis is supported by the results of SEM and AFM analyses.

The crystallite size (D) of the GHAP and Ag was estimated by the Scherrer equation [32], Equation (1),

where β denotes the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the peak, θ signifies the Bragg angle, and λ indicates the wavelength (0.154 Å). The dislocation density (δ) was given using the subsequent formula, Equation (2) [33].

Furthermore, lattice strain values (M) were calculated by the Stokes–Wilson formula, Equation (3) [34].

The values of D, δ, and M are presented in Table 1 for GHAP and for AgNPs in the composite Ag@GHAP. The average crystalline size D of the GHAP is 10.2 nm, while for Ag in the composite Ag@GHAP is increased to 15.6 nm. The estimated dislocation density is nearly 99.46 × 10−4 lines/nm2 for GHAP, while for Ag in the composite Ag@GHAP is decreased to 45.29 × 10−4 lines/nm2, and the lattice strain values (M) are nearly 0.73 for GHAP and reduced to 0.45 for Ag in the composite Ag@GHAP. The data confirms that the degree of crystallinity for GHAP decreased with the addition of Ag. This may be attributed to the addition of Ag correlating with variations in crystallite size values.

Table 1.

The average crystalline parameters of the GHAP and the AgNPs in the Ag@GHAP composites.

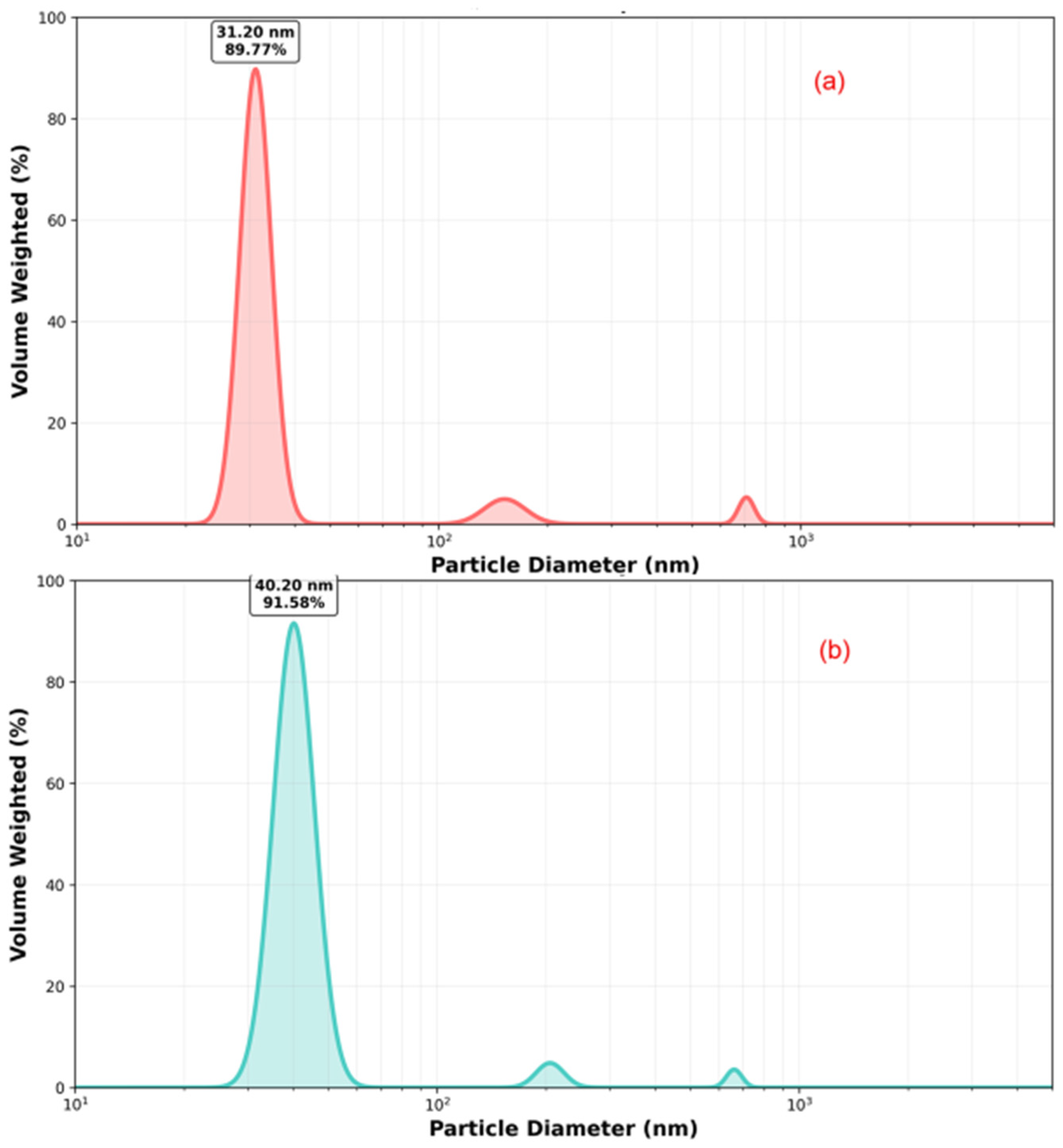

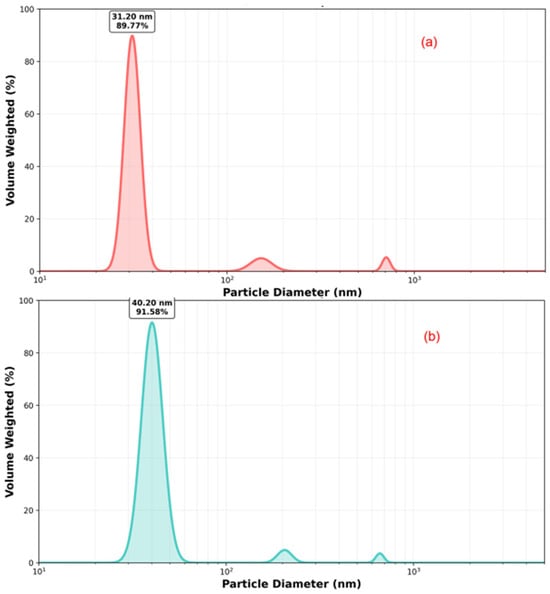

2.1.4. DLS Analysis

The particle size distribution for GHAP is shown in Figure 4a and for the Ag@GHAP is shown in Figure 4b. The analysis for GHAP reveals an average particle size of 31.20 nm. The distribution of the size shows a broad shape, which means the GHAP has a surface reactive structure with nanoscale aggregates. The addition of AgNPs to GHAP modifies the particle size distribution which is expanded to the 40.20 nm range as seen in Figure 4b. This is because the interstitial gaps filled by AgNPs modified the GHAP grain aggregation. The obtained results show the size range for the Ag@GHAP composite is changed compared to GHAP. The particle size distribution and uniform dispersion confirms the improvements of the homogeneity properties of the composite [35].

Figure 4.

The particle size distribution of (a) GHAP and (b) Ag@GHAP.

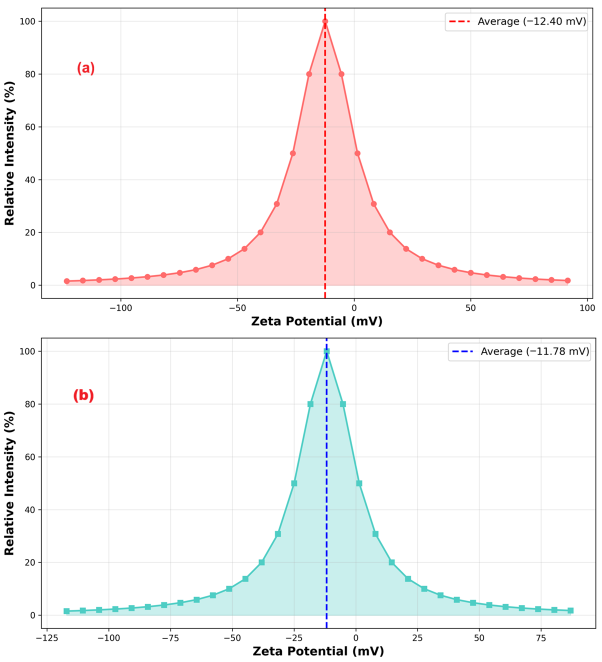

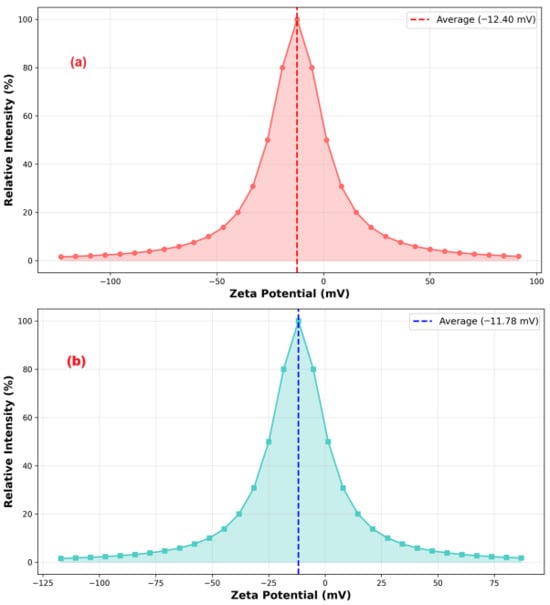

2.1.5. Zeta Potential Studies

The Zeta potential of GHAP is shown in Figure 5a, while for the composite Ag@GHAP is shown in Figure 5b. The presence of phosphate groups and hydroxyl ions in the medium causes GHAP to have a negative zeta potential of around −12.4 mV, as shown in Figure 5a. This charge helps electrostatic repulsion to keep particles to make colloidal solutions more stable [27]. The negative zeta potential shows a more repulsive force to produce stable suspensions. The zeta potential is less negative and reaches −11.78 mV for the composite Ag@GHAP, due to the inclusion of AgNPs with hydroxyapatite as shown in Figure 5b. The surface interaction of the phosphate and hydroxyl groups of GHAP induced more surface charges [36], which indicates that the AgNPs increased the surface charge properties of the GHAP matrix. The results indicate that the fabricated composite GHAP/AgNPs shows great promise for coatings and photocatalysis due to their enhanced stability and surface reactivity.

Figure 5.

Zeta potential of (a) GHAP and (b) Ag@GHAP.

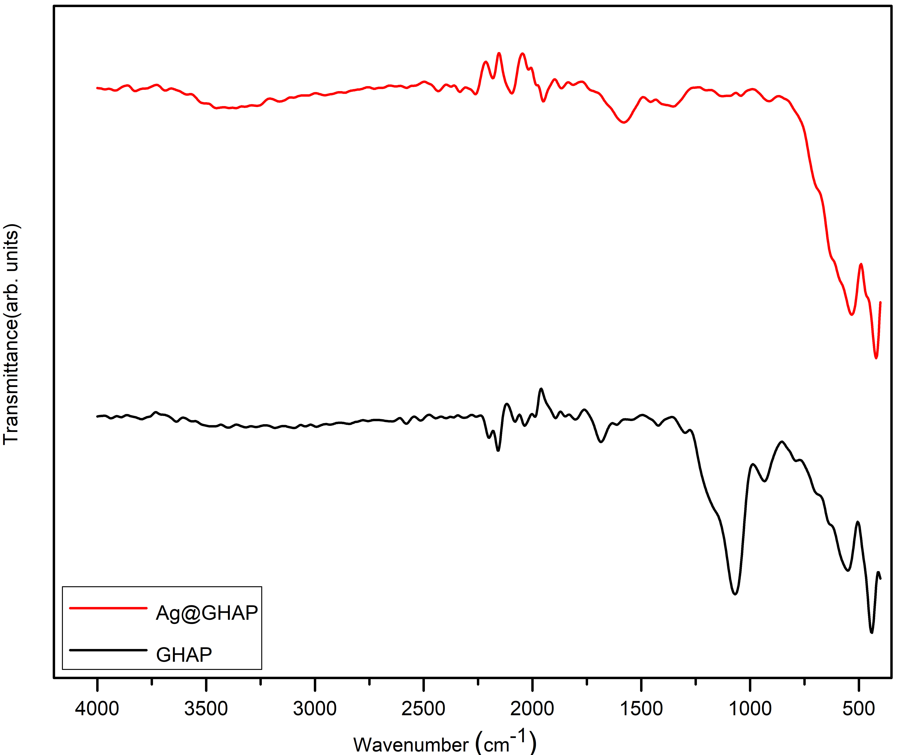

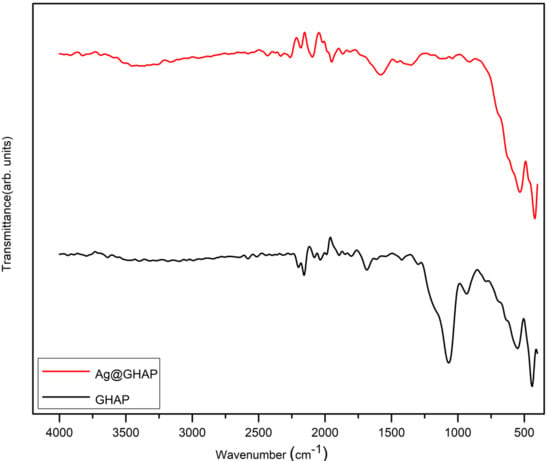

2.1.6. FTIR Investigation

The FTIR spectra of GHAP and Ag@GHAP powder samples confirmed the vibrational bands of the phosphate (PO43−) and hydroxyl (OH−) groups [37] as shown in Figure 6. The absorption bands of 1065 cm−1 and 925 cm−1 corresponding, respectively, to the phosphate asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations. The GHAP is identified by the appearance of bending vibrations at 550 cm−1. The weak broadened bands around 3570 cm−1 and 630 cm−1 are assignable to OH− vibration, which confirms the presence of the hydroxyapatite phase [38]. The changes in the band intensities and the shifting of peaks indicate that the AgNPs interact with the functional groups of GHAP. The hydrogen bonding interactions with the partial replacement of OH− groups by the addition of AgNPs causes broadening and reduction in peak intensity. These changes prove the AgNPs successfully integrated into GHAP which enhances biological and photocatalysis capabilities [39].

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of GHAP and Ag@GHAP.

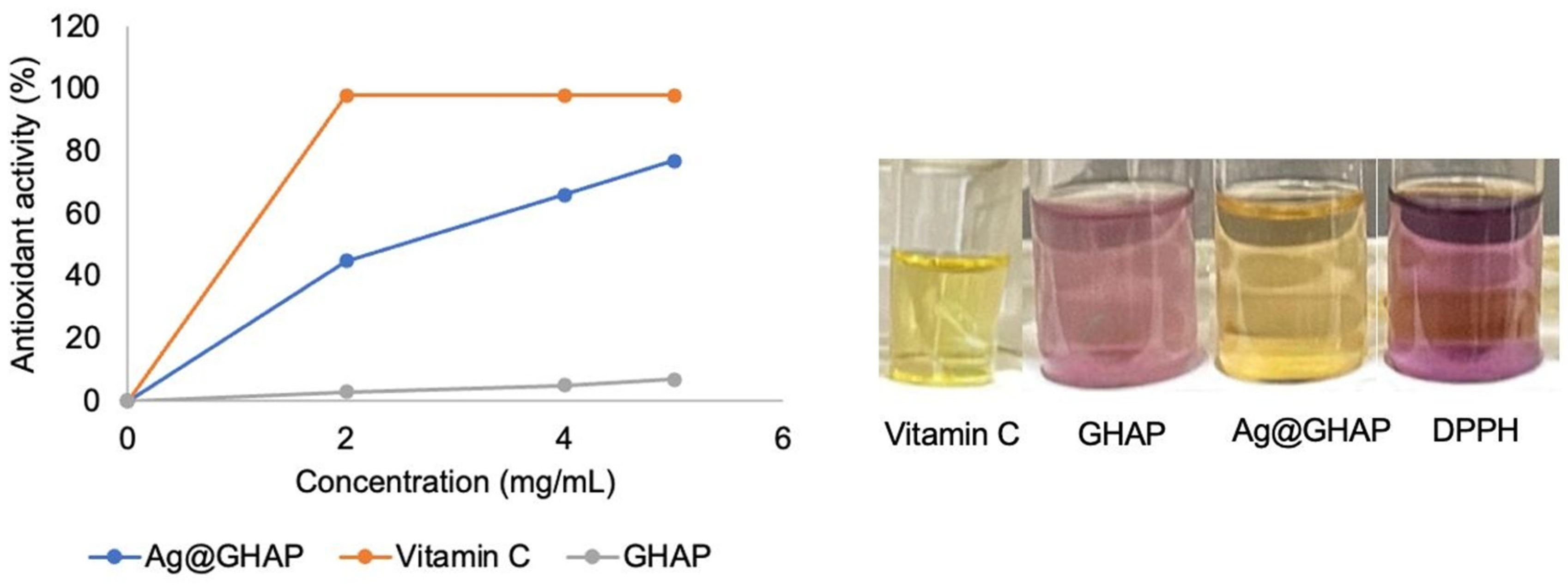

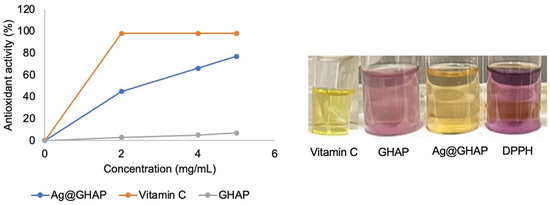

2.2. Antioxidant Activity of GHAP and Ag@GHAP

The DPPH assay represents one of the popular methods for evaluating the ability of an antioxidant compound to scavenge free radicals [40]. The assay principle is based on the ability of antioxidants to donate electrons or hydrogen atoms to neutralize free radicals. The deep violet color of DPPH, a nitrogen-centered radical stabilized by delocalization across its aromatic system, is accompanied by a significant absorbance at 517 nm in its absorption spectrum [41]. Thus, the conversion of DPPH• into its yellow reduced form (DPPH-H) upon interaction with an antioxidant agent results in a detectable drop in absorbance. In addition, the stable ascorbyl radical is formed when ascorbic acid (vitamin C) donates a hydrogen atom from its enediol group. The antioxidant activities of GHAP, Ag@GHAP, and ascorbic acid were evaluated at various concentrations, and their IC50 values were determined with the purpose of comparing their free radical scavenging potentials, (Table 2, Figure 7). Ag@GHAP obviously showed a concentration-dependent activity: 77% at 5 mg/mL decreased to 45% at 2 mg/mL with an IC50 value of 2.949 mg/mL, indicating outstanding antioxidant potency. On the contrary, GHAP had very weak activity, having only 7% inhibition at the highest concentration and a high value of IC50 (36.83 mg/mL), indicating the minimal free radical scavenging capacity of GHAP. The positive control used, ascorbic acid, had nearly complete inhibition, ≈98%, at all tested concentrations together with the lowest IC50 value, 1.03 mg/mL, confirming a strong antioxidant capacity. These results thus show that Ag@GHAP exhibits higher antioxidant activity compared to pure GHAP, demonstrating that the presence of decorated silver enhanced the antioxidant activity [42]. The data presented that the sample Ag@GHAP exhibits a dose-dependent antioxidant activity. As the concentration decreases from 5 mg/mL to 2 mg/mL, the antioxidant activity decreases from 77% to 45%, indicating that a higher concentration of the sample is more effective at neutralizing free radicals.

Table 2.

Antioxidant activity of GHAP and Ag@GHAP samples according to DPPH assay.

Figure 7.

Antioxidant activity of GHAP and Ag@GHAP.

2.3. Photocatalytic Activity of GHAP and Ag@GHAP

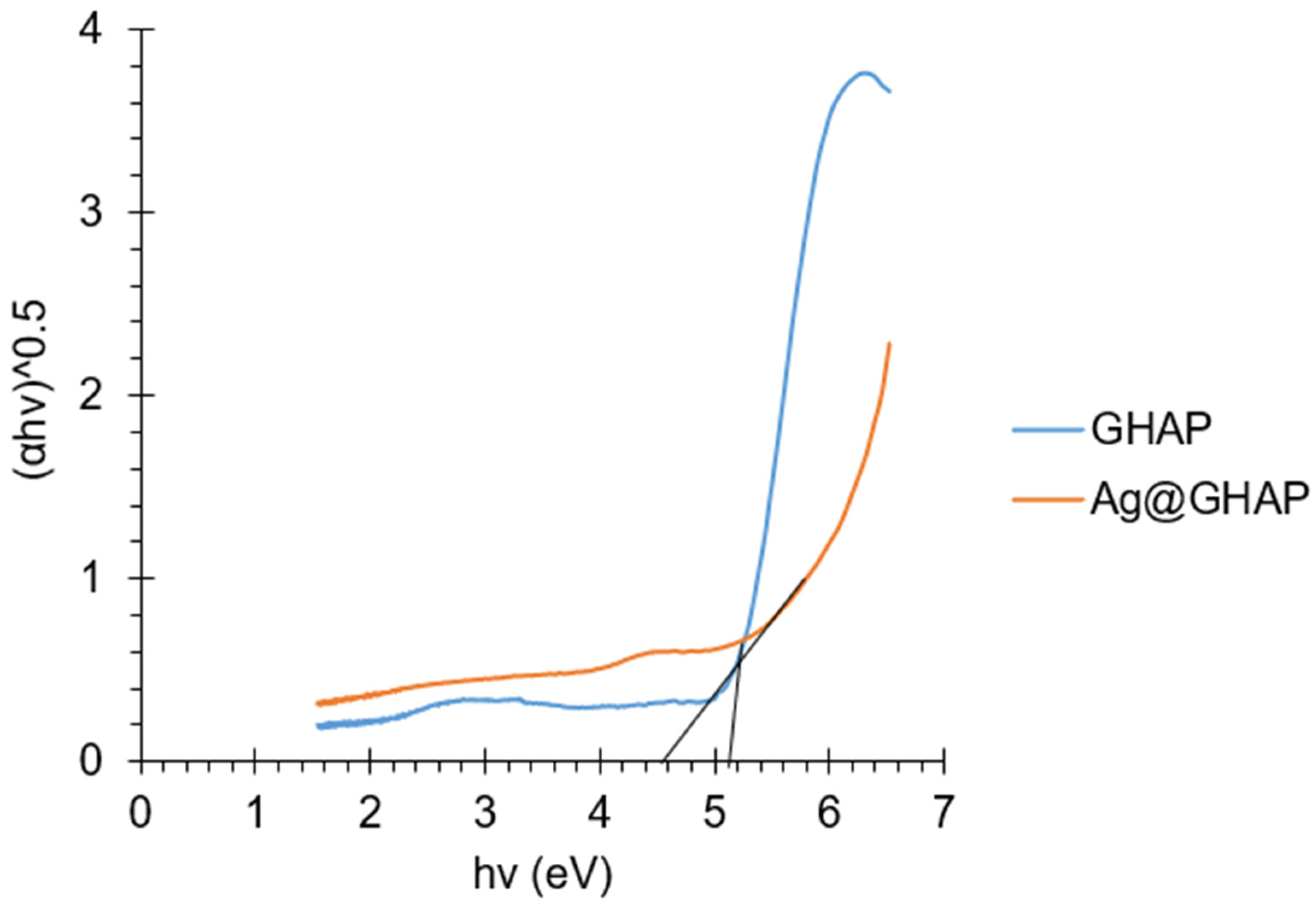

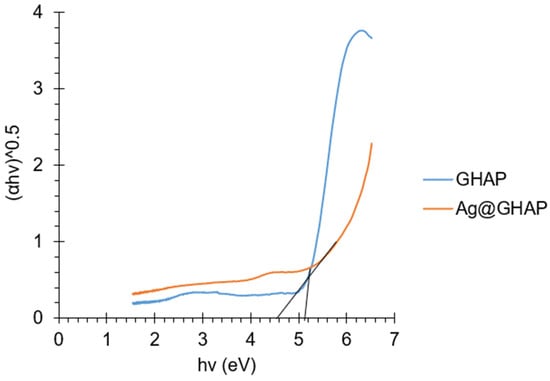

The energy band gap of GHAP and Ag@GHAP has been studied using the Tauc’s equation, Equation (4) [43], Figure 8.

where α is the absorption coefficient,

is photon energy, n = ½ corresponds to allowed direct, A is a constant, Eg is the band gap, and ν is the frequency of the photon. The energy band gap can be calculated by plotting (αhν)2 as a function of photon energy (hν).

Figure 8.

Tauc’s plot of GHAP and Ag@GHAP.

The energy band gap values obtained were 5.1 eV and 4.5 eV for GHAP and Ag@GHAP, respectively. This indicates that the silver decorated sample has higher semiconducting properties compared to the undecorated sample, which is attributable to the effect of silver [44]. Therefore, Ag@GHAP is used as a photocatalyst by degrading MB dye under solar irradiation with an intensity of 40 × 103 LUX.

The absorption spectra of MB dye were studied as a result of three different control experiments: photolysis without a catalyst, catalyst adsorption without light, and photolysis with a catalyst present. At a maximum of 666 nm, the chromophore absorption of MB is seen [45]. The photolysis experiment showed that there was no dye degradation in the absence of Ag@GHAP. After 60 min the MB removal was checked in the presence of Ag@GHAP (0.5 g/L) and in the presence and absence of sunlight. Adsorption experiment results after 60 min without light showed a slight loss in dye color with a removal efficiency of ≈30.90%, indicating the presence of active sites on the Ag@GHAP surface that allowed dye adsorption. After 60 min, the efficiency of dye degradation when a catalyst is present and exposed to sunlight is ≈72.7%. These tests conclude that Ag@GHAP is a good photocatalyst that effectively degraded MB under sunlight irradiation.

The study of the effects of contact time, catalyst mass, and solution pH was carried out to find the optimal condition of photocatalytic degradation of MB under solar irradiation in the presence of Ag@GHAP.

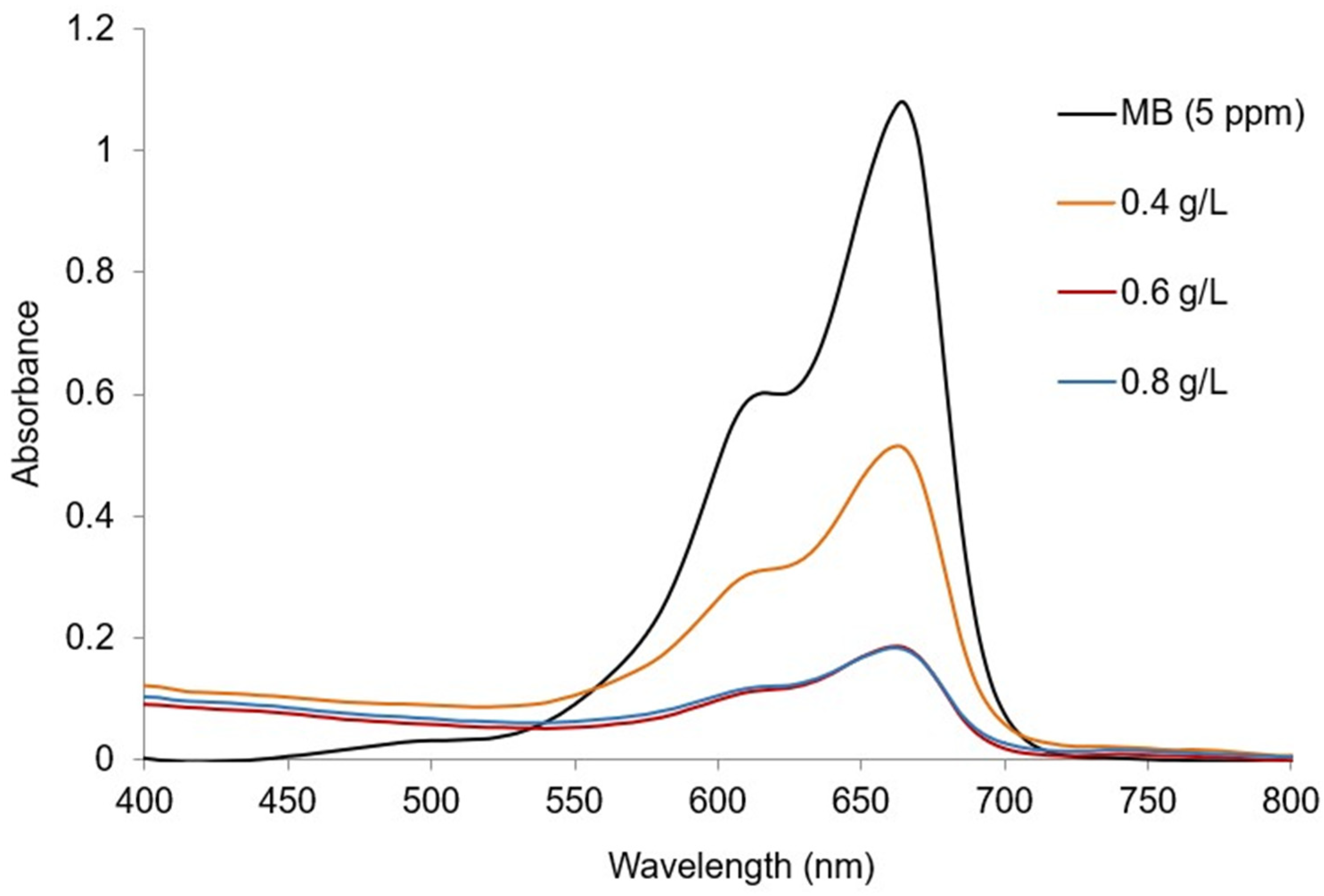

2.3.1. Effect of Catalyst Dose

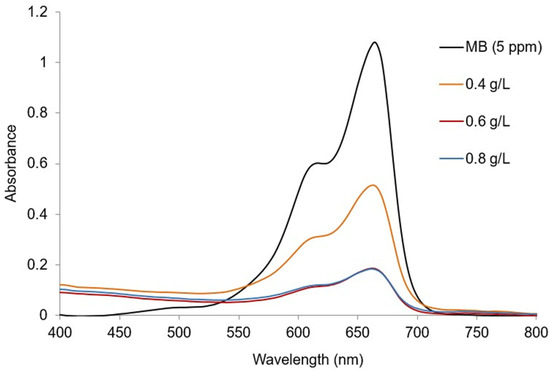

Figure 9 shows the absorption spectra of MB dye with variation in the catalyst doses (0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 g/L) of Ag@GHAP with other parameters being constant, natural pH (7.4), contact time (90 min), and 5 ppm MB dye. The removal percentage varied from 45.45% to 85.45% as a result of the increased number of active sites accessible for MB adsorption when the catalyst mass was increased from 0.4 g/L to 0.6 g/L [44]. There was no notable chromophore breakdown at the dose of 0.8 g/L. This is ascribed to the optimum mass of Ag@GHAP for MB molecule adsorption, which is 0.6 g/L. So, this concentration is chosen as the desired dose in the following experiments.

Figure 9.

Absorption spectra of MB with different catalyst concentrations.

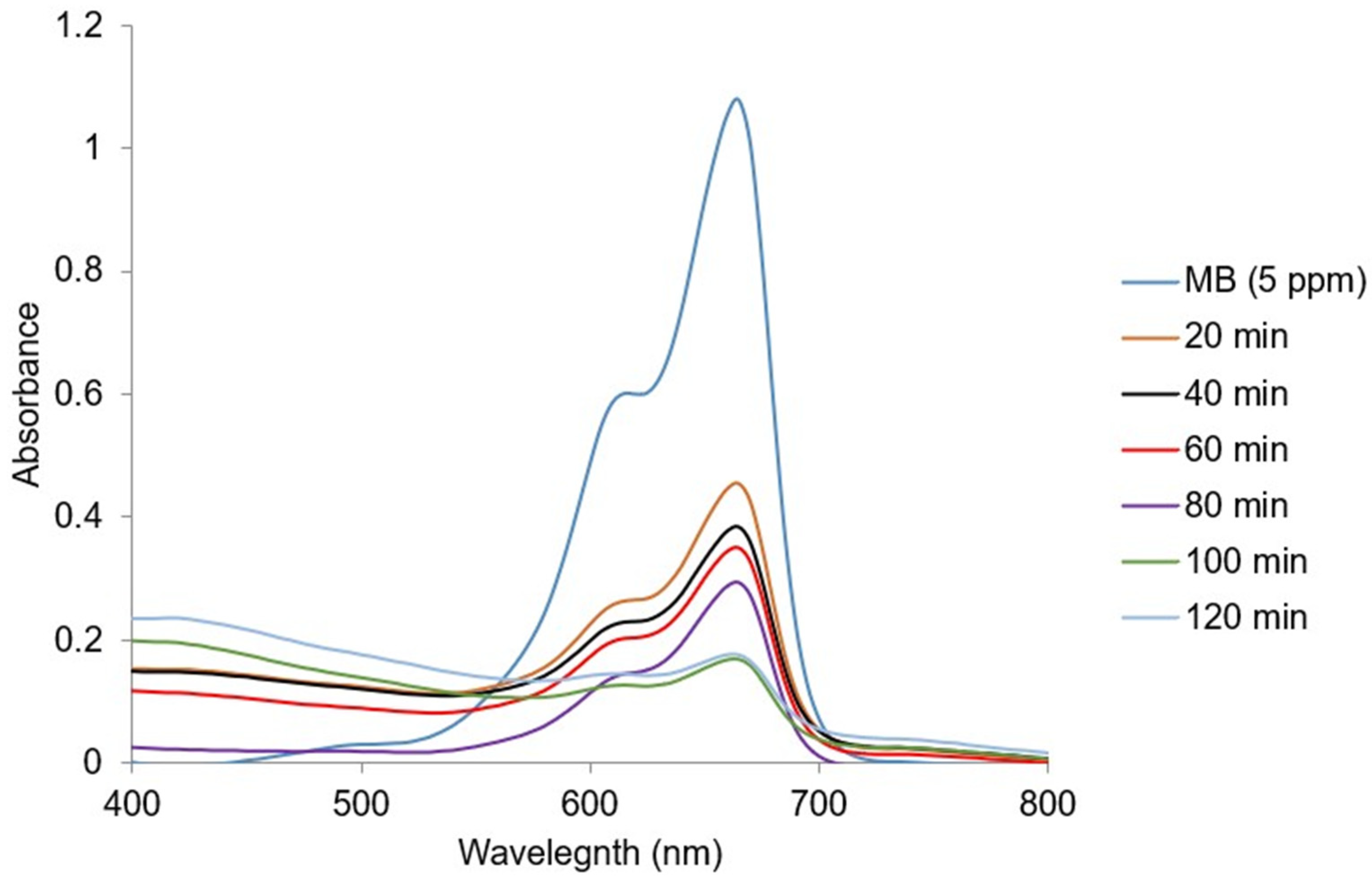

2.3.2. Effect of Illumination Time

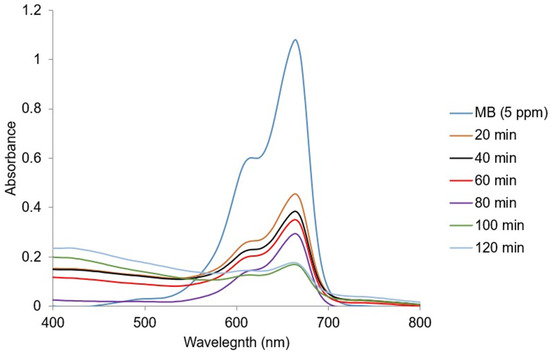

The effect of the ideal time of the photocatalytic degradation of MB (5 ppm) using 0.6 g/L of Ag@GHAP is illustrated in Figure 10. In the first 20 min, the removal of MB rises quickly, reaching 60.15%, which is assigned to the presence of a high number of active sites on the catalyst surface, leading to increased adsorption of MB molecules [46]. The degradation efficiencies are 65.01%, 66.92%, 71.98%, 85.05%, and 85.08%, respectively, at 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 min. As active sites on the Ag@GHAP surface were completed gradually, MB adsorption decreased, which resulted in a reduction in the removal rate. At 100 min, the maximum degradation (85.05%) is achieved.

Figure 10.

Electronic spectra of MB with contact illumination time.

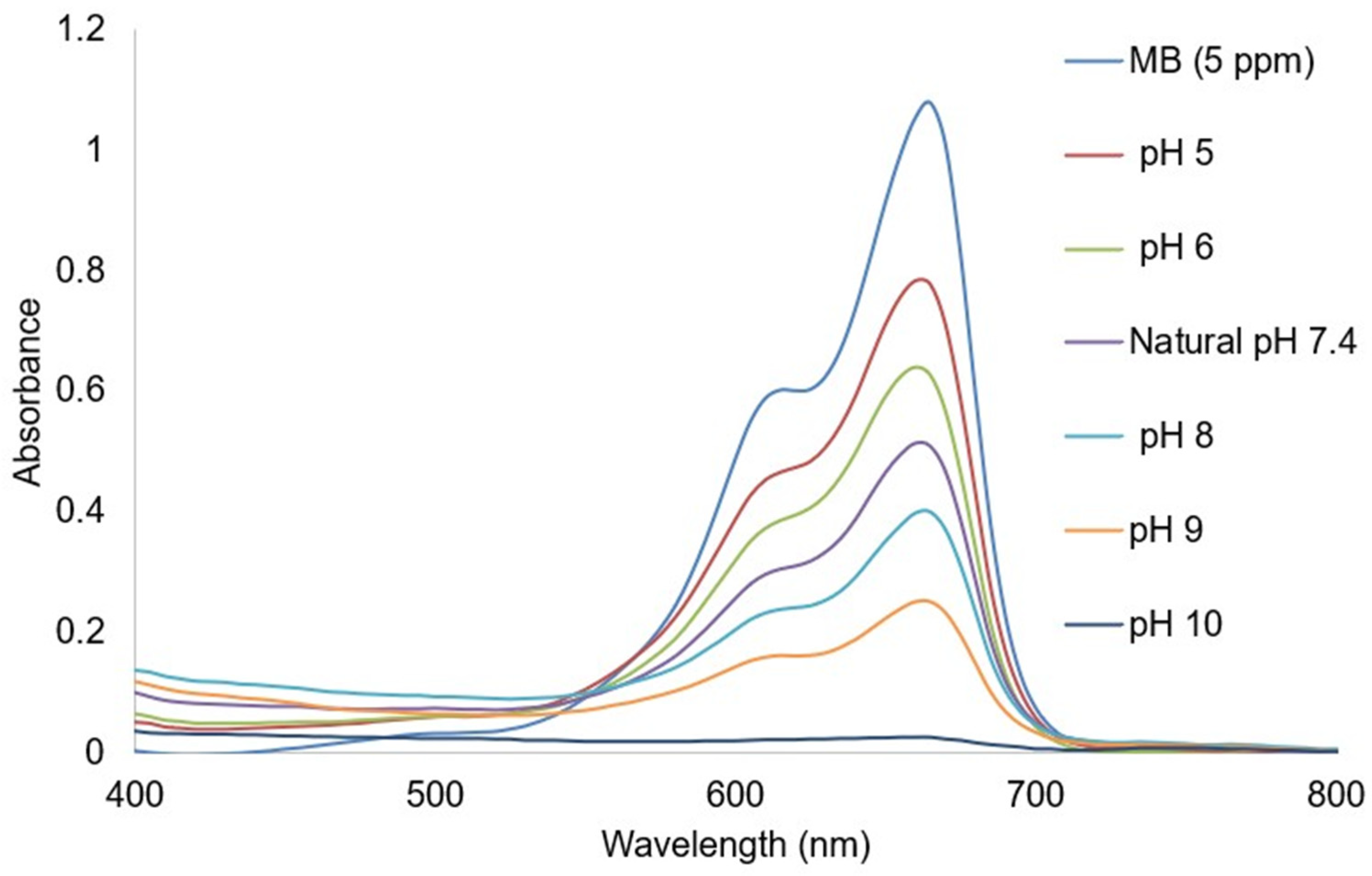

2.3.3. Effect of pH

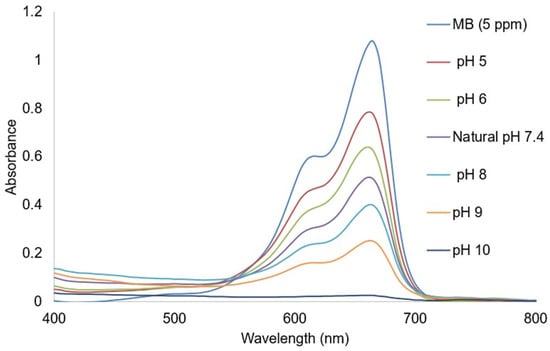

The impact of solution pH (5, 6, 7.4, 8, 9, and 10) on photocatalytic removal of 5 ppm MB was investigated with a constant dose of Ag@GHAP and contact time of 0.6 g/L and 100 min, respectively. As shown in Figure 11, the largest amount of MB degradation (99.15%) occurs at pH 10, which is the optimal pH value for MB degradation. The pH value at which the adsorbent has the maximum negative charge is on this surface. The least amount of MB decomposition, which correlates to the maximum positive charge, is seen in acidic pH [47]. For MB as a cationic dye, the percentage of photocatalytic degradation decreases with increasing solution acidity and increases with increasing solution basicity. This explains the greater uptake of MB in high basic solution due to the increasing of the negative charge of the catalyst. Otherwise, in an acidic medium, the positive charge on the catalyst surface leads to the electrostatic repulsion of the MB molecules from the adsorbent, which reduces the adsorption of MB [48].

Figure 11.

Effect of pH on MB degradation.

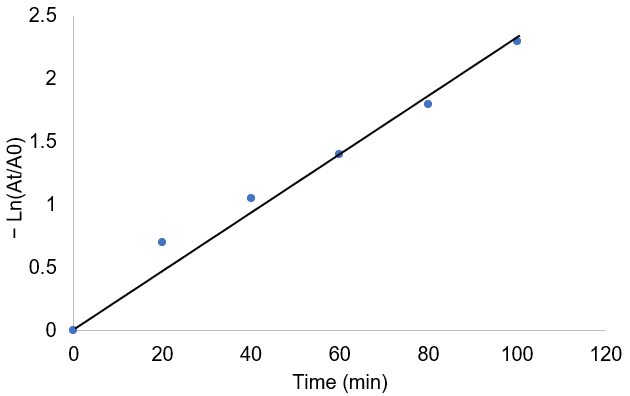

2.3.4. Photocatalysis Kinetic Investigation

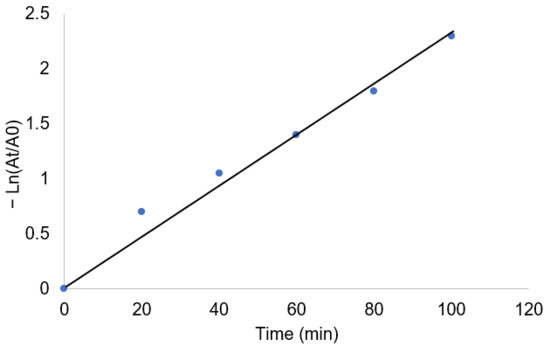

The kinetic reaction of the photocatalytic decomposition of MB in the presence of Ag@GHAP as a photocatalyst under sunlight irradiation has been evaluated using the Langmuir–Hinshelwood model [49], Equation (5),

where A0 is the initial MB concentration, At is the MB concentration after a definite time, k is the rate constant, and t is the MB decomposition time. As present in Figure 12, the linear relationship between

and (t) indicates the photocatalytic process follows a pseudo-first order model. The calculated rate constant (k) was 0.0216 min−1 and the correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.98) confirms the fitting of the data with the pseudo-first order model [50]. This suggests the photocatalytic degradation of MB depends mainly on the dye concentration, while Ag@GHAP supports sufficient active sites for dye adsorption for photoreaction with sunlight.

Figure 12.

Pseudo first order photocatalytic degradation kinetics of MB in presence Ag@GHAP.

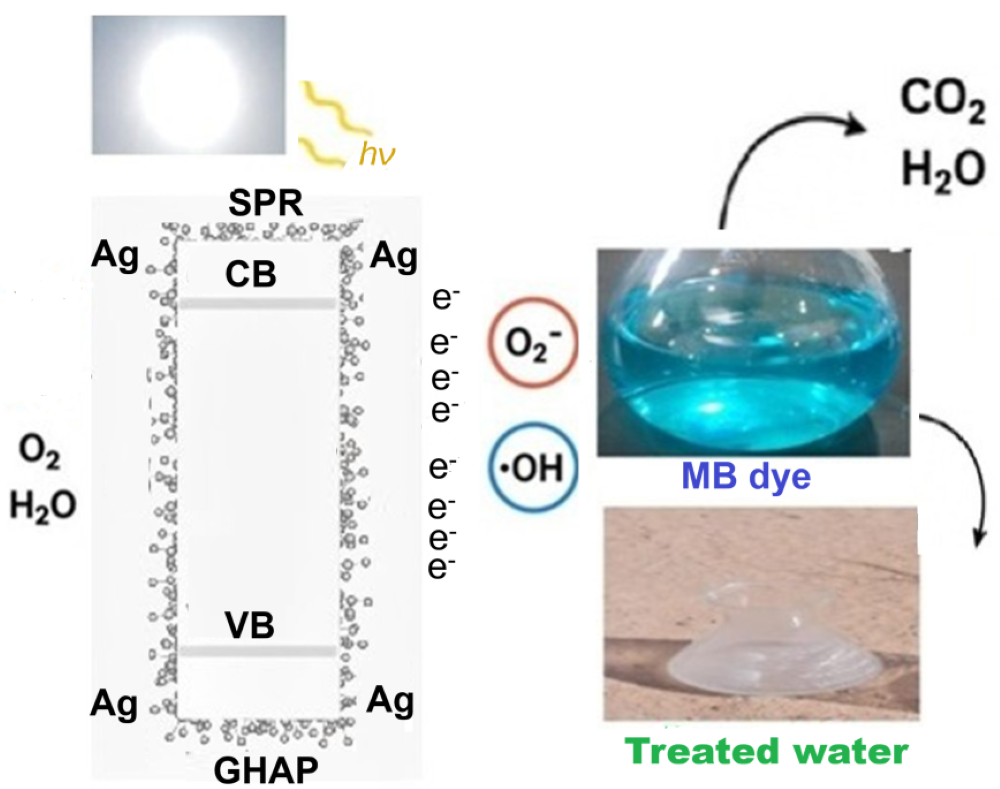

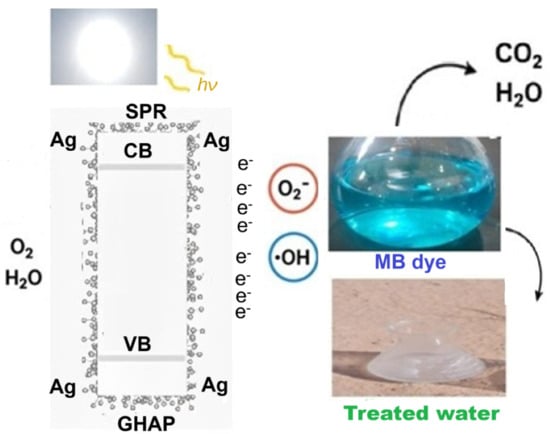

2.3.5. Photocatalysis Mechanism

Figure 13 represents the proposed photocatalytic mechanism of Ag@GHAP under sunlight irradiation. The photocatalytic activity can be interpreted as plasmon resonance (SPR) of Ag-NPs [51]. The sunlight irradiation produces holes (h+) and electrons (e−) on the catalyst surface. The generated electrons transferred to the GHAP conduction band and reacted with oxygen molecules, resulting in the formation of superoxide anion radicals (·O2−). The generated holes that formed due to the migration of electrons reacted with water molecules, resulting in the formation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH). The generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) reacted with the MB molecule and mineralized it to CO2 and H2O, Equations (6)–(10), which appeared from the gradual discoloration of the MB solution. Therefore, we can conclude that the SPR of Ag-NPs enhanced sunlight absorption and charge separation, improving the photocatalytic activity of Ag@GHAP.

Ag@GHAP + hν (sunlight) → e− + h+

O2 + e− → O2−

h+ + H2O → OH +H

h+ + OH− → OH

MB (Blue color) + OH + O2− → CO2 + H2O + Pure water (colorless)

Figure 13.

Suggested mechanism of the photocatalytic degradation of MB in presence Ag@GHAP.

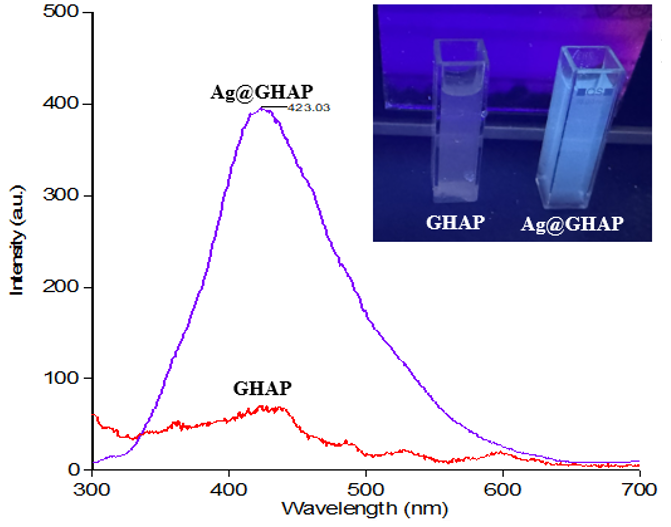

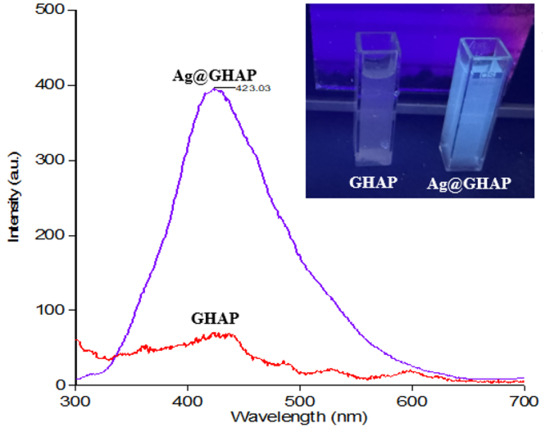

2.3.6. Photoluminescence (PL) Analysis

Upon irradiation under a UV light source (365 nm), Ag@GHAP in water exhibits a detectable PL emission at room temperature compared to the PL emission of GHAP, Figure 14. The figure also exhibits the PL spectra upon excitation at 230 nm. It is observed that the Ag@GHAP composite has a significantly enhanced PL emission peak at 423.03 nm, as compared to pristine GHAP, with a 5.7-fold enhancement in the UV emission of Ag@GHAP, which further confirms the synergistic interaction between Ag-NPs and GHAP [52]. Indeed, Ag-NPs act as efficient recombination sites for the electron-hole pairs (e−/h+) generated upon sunlight irradiation, due to the SPR effect of silver [53]. These results agree well with the proposed mechanism where the electrons excited from Ag-NPs are transferred to the CB of GHAP, confirming charge separation and subsequent generation of ROS.

Figure 14.

Emission spectra of GHAP and Ag@GHAP at λex = 230 nm; the inset shows the image of the effect of UV excitation at λ = 365 nm on the GHAP and Ag@GHAP.

The results of the current study are compared with similar hydroxyapatite composites in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the photocatalytic and antioxidant activities of Ag@GHAP with similar hydroxyapatite composites.

3. Experiments

3.1. Starting Materials

A piece of goat bone was obtained from a market in Sakaka, Jouf, Saudi Arabia. Milli-Q water was used for all experiments. Silver nitrate, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), and methylene blue dye was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as received.

3.2. Characterization Techniques

A Zeiss LEO Supra 55VP Field Emission SEM Zeiss 1530 was used to take SEM pictures (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) operated at 20 kV with a working distance of 10 mm. Powder X-ray diffraction spectra were obtained using a D8-Find Bruker diffractometer (Burker, Billerica, MA, USA) fitted with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å) running at 40 kV and 40 mA. FTIR measurements in the wavenumber range of 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1 were performed with a spectrophotometer, an IRTracer-100 SHIMADZU (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Zeta potential was measured at room temprature using a NanoSight NS500 zeta sizer analyzer supplied by Malvern Panalytical Ltd. (Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, Panalytical, UK). AFM was conducted using a 5600 L AFM instrument model (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Malvern Panalytical Ltd. manufactures the particle size analyzer used for DLS, the NanoSight NS500 model (Malvern Panalytical UK). Absorption spectra in the wavelength range of 190–1100 nm were recorded using a Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Cary Eclipse Fluorometric spectrophotometer (Agilent Company, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for testing the fluorescence analysis. All measurements were taken with a quartz cell (1 cm) at slit widths 5 nm for excitation wavelength and 10 nm for emission wavelength.

3.3. Fabrication of Recycled Hydroxyapatite (GHAP)

A 10 g fragment of goat bone was purchased from a marketplace in Sakaka. Recycled goat bone was prepared by removing the impurities. The remaining bone marrow was subsequently crushed and then calcined for two hours at 1000 °C in a muffle furnace. The resulting GHAP was then pulverized into a powder and stored in a desiccator for further experiments.

3.4. Fabrication of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Decorated with Hydroxyapatite (Ag@GHAP)

A 5 g sample of goat bone was boiled in 100 mL of distilled water, resulting in a gel that, in a volume of 50 mL, was mixed into a 50 mL solution of 1% (w/v) silver nitrate solution. During the stirring, 5 g of GHAP were added to the mixture. This solution was heated to 80 °C for 1 h with continuous stirring. The brown solid formed was filtered and dried for 2 h at 110 °C in an oven, then calcined for 2 h at 500 °C in a muffle furnace to produce Ag@GHAP.

3.5. Photocatalytic Experiments

As a model for observing the solar semiconducting behavior of Ag@GHAP, methylene blue dye (MB) was used. To embed the adsorption of MB on the catalyst surface, a definite weight of catalyst was introduced to a 50 mL solution of 5 ppm of MB in a 150 mL quartz conical flask with stirring in the dark. The mixture was then exposed to 40 × 103 Lux of sunlight (measured by (PeakTech Prüf- und Messtechnik GmbH, Ahrensburg, Germany). Every 20 min, about 3 mL of the treated MB solution was centrifuged for 1 min to separate the solid photocatalyst. Then, the absorbance (A) of the solution was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at (λmax 666 nm), and the decomposition efficiency (%) was calculated according to the formula in Equation (11) [60,61]:

where A0 is the absorbance of MB before treatment (1.1 AU) and At is the MB absorbance after photocatalytic experiment.

3.6. Antioxidant Experiments

GHAP and Ag@GHAP were conducted for evaluation of their antioxidant activity using the DPPH radical scavenging method [62]. This method is based on the capability of the antioxidant agent to reduce 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (violet color) into 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazine (yellow color), which results in a measurable decrease in absorbance at 517 nm.

To perform the test, a 0.1 mM DPPH solution was prepared in ethanol. One milliliter of this solution was combined with 2 mL of the sample at different concentrations (2, 4, and 5 mg/mL) or with the standard ascorbic acid. Then, the mixture was incubated in a dark at room temperature for 30 min, and then it was measured by UV-Vis. The percentage of radical scavenging was calculated according to Equation (12) [63],

% Scavenging = [(Acontrol − Asample)/Acontrol] × 100

Acontrol is the absorbance of the DPPH solution before treatment with the sample, while Asample is the absorbance of the DPPH solution after treatment with the sample. The concentration required to neutralize 50% of the radicals (IC50 value) was calculated. All experiments were carried out in triplicate [64].

4. Conclusions

This study presented a novel eco-friendly approach for synthesizing silver nanoparticles using gel extract from goat bone, subsequently incorporated into hydroxyapatite bioceramic, which is produced from recycled goat bones. A thorough evaluation was performed utilizing physicochemical techniques (FTIR, XRD, AFM, DLS, SEM, and zeta potential), which verified the successful synthesis of crystalline hydroxyapatite with modified surface characteristics and evenly distributed silver nanoparticles. Compared to pristine hydroxyapatite, the silver composite significantly enhanced PL emission and improved the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (5 ppm) with 99.15% removal efficiency under sunlight. The mechanism of photocatalytic activity is discussed based on the SPR of Ag-NPs. Also, the silver composite showed antioxidant potential with an IC50 value of 2.949 compared to 36.83 for pure hydroxyapatite, which implies that the silver-decorated composite fabricated from goat bone is a cheap and viable option for use in environmental and biomedical fields. Future works will explore its applications in the removal of other pollutants and biocompatibility applications such as drug delivery, antimicrobial activity, antihemolytic activity, and wound healing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.N.; Methodology, H.B. and A.M.N.; Software, A.A. and R.F.H.; Validation, A.H.A. and A.S.A.Z.; Formal analysis, R.F.H. and F.A.A.; Investigation, A.S.A.Z.; Resources, A.A. and H.B.; Data curation, R.F.H. and F.A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.H.A., A.A. and H.B.; Writing—review & editing, A.A. and A.M.N.; Visualization, A.M.N.; Supervision, A.H.A. and A.S.A.Z.; Funding acquisition, A.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No (DGSSR-2024-02-01149).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lunetta, E.; Messina, M.; Cacciotti, I. Doped hydroxyapatite bioceramic from food wastes for orthopedic applications. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.M.; Arafa, W.A.; Ashammari, K.; Moustafa, S.; Alsirhani, A.M.; Hasaneen, M.F. A new green catalyst and antimicrobial agent derived from eco-friendly products of camel bones: Synthesis and physicochemical characterization. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 13589–13607. [Google Scholar]

- Okpe, P.C.; Folorunso, O.; Aigbodion, V.S.; Obayi, C. Hydroxyapatite synthesis and characterization from waste animal bones and natural sources for biomedical applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2024, 112, e35440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu’ad, N.M.; Haq, R.A.; Noh, H.M.; Abdullah, H.Z.; Idris, M.I.; Lee, T.C. Synthesis method of hydroxyapatite: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 29, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, M.; Rajan, H.K.; Chandraprabha, M.N.; Shetty, S.; Mukherjee, T.; Girish Kumar, S. Recent developments in green synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanocomposites: Relevance to biomedical and environmental applications. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2024, 17, 2422409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.H.; Arafa, W.A.; Moustafa, S.M.; Alsohaimi, I.H.; Elnasr, T.A.S.; Halawani, R.F.; Al Zbedy, A.S.; Nassar, A.M. Green extraction of biomass from waste goat bones for applications in catalysis, wastewater treatment, and water disinfection. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Kawsar, M.; Bahadur, N.M.; Ahmed, S. Synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite using emulsion, pyrolysis, combustion, and sonochemical methods and biogenic sources: A review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 3548–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Shojai, M.; Khorasani, M.T.; Dinpanah-Khoshdargi, E.; Jamshidi, A. Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite with diverse structures. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7591–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y.; Rawal, A.; Koshy, P.; Ben-Nissan, B.; Kono, H.; Kikuchi, M. Structural transformations in mechanochemically-synthesized strontium-doped hydroxyapatite. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 28073–28082. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, K.; Skwarek, E. Physicochemical Analysis of Composites Based on Yellow Clay, Hydroxyapatite, and Clitoria ternatea L. Obtained via Mechanochemical Method. Materials 2025, 18, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naubnome, V.; Prihanto, A.; Schmahl, W.W.; Pusparizkita, Y.M.; Ismail, R.; Jamari, J.; Bayuseno, A.P. Chemical precipitation of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite with calcium carbonate derived from green mussel shell wastes and several phosphorus sources. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawsar, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Bahadur, N.M.; Islam, D.; Ahmed, S. Crystalline structure modification of hydroxyapatite via a hydrothermal method using different modifiers. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 3889–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova-Udaeta, M.; Kim, Y.; Yasukawa, K.; Kato, Y.; Fujita, T.; Dodbiba, G. Study on the synthesis of hydroxyapatite under highly alkaline conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 4385–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, K.; Swamiappan, S. Synthesis of hydroxyapatite via sol–gel combustion route: A comparative analysis of single and mixed fuels. Mater. Lett. 2024, 357, 135731. [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa, M.; Hanazawa, T.; Itatani, K.; Howell, F.S.; Kishioka, A. Characterization of hydroxyapatite powders prepared by ultrasonic spray-pyrolysis technique. J. Mater. Sci. 1999, 34, 2865–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suba Sri, M.; Usha, R. An insightful overview on osteogenic potential of nano hydroxyapatite for bone regeneration. Cell Tissue Bank. 2025, 26, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avşar, C.; Ertunç, S. Development of industrial waste management approaches for adaptation to circular economy strategy: The case of phosphogypsum-derived hydroxyapatite. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 2770–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Thanikodi, S.; Palaniyappan, S.; Giri, J.; Hourani, A.O.; Azizi, M. Sustainable synthesis of marine-derived hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications: A systematic review on extraction methods and bioactivity. Adv. Manuf. Polym. Compos. Sci. 2025, 11, 2508547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.A.M.; Morais, D.F.S.; Oliveira, R.A.; Teodoro, M.D.; Silva, U.C.; Motta, F.V.; Bomio, M.R.D. Study of the influence of phase transformations of the biogenic Hydroxyapatite/Nb2O5 heterostructure on the photodegradation of different dye mixtures under sunlight irradiation. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 192, 109400. [Google Scholar]

- Fatimah, I.; Audita, R.; Purwiandono, G.; Hidayat, H.; Sagadevan, S.; Oh, W.C.; Doong, R.A. In-situ synthesis of hydroxyapatite-supported Ag3PO4 using cockle (Anadara granosa) shell as photocatalyst in rhodamine B photodegradation and antibacterial agent. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100797. [Google Scholar]

- Algethami, J.S.; Hassan, M.S.; Alorabi, A.Q.; Alhemiary, N.A.; Fallatah, A.M.; Alnaam, Y.; Almusabi, S.; Amna, T. Manganese ferrite–hydroxyapatite nanocomposite synthesis: Biogenic waste remodeling for water decontamination. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.S.; Machado, T.R.; Trench, A.B.; Silva, A.D.; Teodoro, V.; Vieira, P.C.; Martins, T.A.; Longo, E. Enhanced photocatalytic and antifungal activity of hydroxyapatite/α-AgVO3 composites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 252, 123294. [Google Scholar]

- Romolini, G.; Gambucci, M.; Ricciarelli, D.; Tarpani, L.; Zampini, G.; Latterini, L. Photocatalytic activity of silica and silica-silver nanocolloids based on photo-induced formation of reactive oxygen species. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2021, 20, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Chawhuaveang, D.D.; Lam, W.Y.H.; Chu, C.H.; Yu, O.Y. The preventive effect of silver diamine fluoride-modified salivary pellicle on dental erosion. Dent. Mater. 2025, 41, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, A.J.; Albusalih, D.; Jasim, T.A.; Radhi, N.S.; Al-Khafaji, Z.; Falah, M. Identify in Vitro Behaviour of Composite Coating Hydroxyapatite-Nano Silver on Titanium Substrate by Electrophoretic Technic for Biomedical Applications. J. Adv. Res. Micro Nano Engieering 2024, 28, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Byon, H.R.; Hong, S. Nanoscale study on noninvasive prevention of dental erosion of enamel by silver diamine fluoride. Biomater. Res. 2024, 28, 0103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.S.; Predoi, D.; Iconaru, S.L.; Predoi, M.V.; Ghegoiu, L.; Buton, N.; Motelica-Heino, M. Copper doped hydroxyapatite nanocomposite thin films: Synthesis, physico–chemical and biological evaluation. Biometals 2024, 37, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, S.; Singh, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Chaudhari, L.R.; Joshi, M.G.; Dutt, D. Silver-doped hydroxyapatite laden chitosan–gelatin nanocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: An in-vitro and in-ovo evaluation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 206–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiammal, S.; Fathima, A.S.L.; Al-Ghanim, K.A.; Nicoletti, M.; Baskar, G.; Iyyappan, J.; Govindarajan, M. Synthesis and characterisation of magnesium-wrapped hydroxyapatite nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 44, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukosman, O.K.; Pourmostafa, A.; Dogan, E.; Bensalem, A. Balancing antibacterial activity and toxicity in silver-loaded hydroxyapatite: The impact of the silver nanoparticle incorporation method. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 9954–9967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, S.; Kumawat, G.; Khandelwal, M.; Khangarot, R.K.; Saharan, V.; Nigam, S.; Harish. Phyco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles by environmentally safe approach and their applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.M.; Nassar, A.M.; Ibrahim, N.M.; Elsaman, A.M.; Rashad, M.M. An easy synthesis of nanostructured magnetite-loaded functionalized carbon spheres and cobalt ferrite. J. Coord. Chem. 2013, 66, 4387–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, A.; Al-Harbi, N.; Alotaibi, B.M.; Uosif, M.A.M.; Abdeltwab, E. Structural characteristics and dielectric properties of irradiated polyvinyl alcohol/sodium iodide composite films. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 159, 111651. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, B.M.; Altuijri, R.; Atta, A.; Abdeltwab, E.; Abdelhamied, M.M. Fabrication, structure and optical characteristics of CuO/polymer nanocomposites materials for optical devices. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2024, 29, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibay-Alvarado, J.A.; Garcia-Zamarron, D.J.; Silva-Holguín, P.N.; Donohue-Cornejo, A.; Cuevas-González, J.C.; Espinosa-Cristóbal, L.F.; Ruíz-Baltazar, Á.d.J.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Polymer-Based Hydroxyapatite–Silver Composite Resin with Enhanced Antibacterial Activity for Dental Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.S.; Predoi, D.; Iconaru, S.L.; Predoi, M.V.; Rokosz, K.; Raaen, S.; Negrila, C.C.; Buton, N.; Ghegoiu, L.; Badea, M.L. Physico-Chemical and Biological Features of Fluorine-Substituted Hydroxyapatite Suspensions. Materials 2024, 17, 3404. [Google Scholar]

- Nashaat, S.M.; Enan, E.T.; El-Din, A.S.S.; Abdelaziz, D. Developing a novel therapeutic and bioactive resin-based root canal sealer incorporated with silver polydopamine-modified hydroxyapatite fillers. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1133. [Google Scholar]

- Keser, S.; Yıldız, A.; Barzinjy, A.A.; Kareem, R.O.; Mahmood, B.K.; Agid, R.S.; Ates, T.; Temüz, M.M.; Koytepe, S.; İnce, T.; et al. Effects of pyrocatechol on the computational, structural, spectroscopic and thermal properties of silver-modified hydroxyapatite. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 61, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser, S.; Firat, M.; Barzinjy, A.A.; Kareem, R.O.; Ates, T.; Ates, B.; Tekin, S.; Sandal, S.; Özcan, I.; Bulut, N.; et al. Impact of quercetin and gallic acid on the electronic, structural, spectroscopic, thermal properties and in vitro bioactivity of silver-modified hydroxyapatite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 339, 130751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhafer, C.E.B.; Nassar, A.M.; Alanazi, A.H.; Alotaibi, N.F.; Ali, H.M.; Hasaneen, M.F.; Moustafa, S.M. Synthesis, Structure, Thermal, and Optical Analysis of Ag@ MgO/ZnO: A Promising Nanocomposite for Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Applications. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e03173. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, P.; Demirhan, E.; Ozbek, B. Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Bioactive Chitosan-Hydroxyapatite Sponge-Like Scaffolds Functionalized with Ficus carica Linn Leaf Extract for Enhanced Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. Food Biosci. 2025, 69, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, N.; Nayak, S.G.; Bandiwaddar, K.T.; Kulkarni, D. Decoration of silver nanoparticles over Galphimia gracilis leaves extract and assessment of their antioxidant properties. Pharmacol. Res.-Nat. Prod. 2025, 8, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.A.; Alqarni, L.S.; Alghamdi, M.D.; Alotaibi, N.F.; Moustafa, S.M.; Nassar, A.M. Phytosynthesis via wasted onion peel extract of samarium oxide/silver core/shell nanoparticles for excellent inhibition of microbes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, P.; Deb, S. Silver nanoparticles decorated wide band gap MoS2 nanosheet: Enhanced optical and electrical properties. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounas, A.; Ait Baha, A.; Izghri, Z.; Idouhli, R.; Tabit, K.; Yaacoubi, A.; Abouelfida, A.; Bacaoui, A. Biochar/Zeolite-Supported TiO2 Nanocatalyst for the Photodegradation of Organic Pollutants in Aqueous Media. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 3139–3150. [Google Scholar]

- Toan, H.P.; Luu, T.A.; Nguyen, D.V.; Nguyen, M.C.; Phan, P.D.M.; Nguyen, N.L.; Van Nguyen, T.; Hoang, L.H.; Binh, T.H.; Dong, C.; et al. Unlocking the Origin of Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Performance via Thermodynamic Insights: A Study of Surface Active-Site Engineering in ZnO. Small 2025, 21, e2412719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matinise, N.; Botha, N.; Fall, A.; Maaza, M. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using zinc vanadate nanomaterials with structural and electrochemical properties. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, M.M.; Shokry, H.; Hassanin, A.H.; Awad, S.; Samy, M.; Elkady, M. Novel palm peat lignocellulosic adsorbent derived from agricultural residues for efficient methylene blue dye removal from textile wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianmawii, L.; Singh, N.M. Photoluminescence and photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and methyl red using Pr3+ doped CdS nanoparticles. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 18, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, S.R.; Hassan, S.A. Impact of LaZnFe2O4 supported NiWO4@D400-MMT@CMS/MMA nanocomposites as a catalytic system in remediation of dyes from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppala, S.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Peng, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, L. Hierarchical ZnO/Ag nanocomposites for plasmon-enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 15116–15121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, B.; Joy, L.K.; Thomas, H.; Thomas, V.; Joseph, C.; Narayanan, T.N.; Al-Harthi, S.; Unnikrishnan, N.V.; Anantharaman, M.R. Evidence for enhanced optical properties through plasmon resonance energy transfer in silver silica nanocomposites. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 085701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanti, M.; Basak, D. Highly enhanced UV emission due to surface plasmon resonance in Ag–ZnO nanorods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 542, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; Fatima, H.; Tahir, J.; Anwar, M.S. Doped hydroxyapatite photocatalyst for efficient degradation of Methylene blue dye. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 172, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, K.; Kumar, N.D.; Velmurugan, R.; Gokulnath, M.; Parvathy, S.; Ayyar, M.; Swaminathan, M.; Prabhu, P.; Alhuthali, A.M.S.; Abdellattif, M.H.; et al. Enhanced efficiency of zinc oxide hydroxyapatite nanocomposite in photodegradation of methylene blue, ciprofloxacin, and in wastewater treatment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junnarkar, M.V.; Sawant, P.V.; Parekar, M.A.; Kardile, A.V.; Thorat, A.B.; Joshi, R.P.; Mene, R.U. Silver-blend hydroxyapatite bio-ceramics for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Acad. Mater. Sci. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalan, A.E.; Afifi, M.; El-Desoky, M.M.; Ahmed, M.K. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes of cellulose acetate containing hydroxyapatite co-doped with Ag/Fe: Morphological features, antibacterial activity and degradation of methylene blue in aqueous solution. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 9212–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Shikha, D. Thrombogenicity, DPPH assay, and MTT assay of sol–gel derived 3% silver-doped hydroxyapatite for hard tissue implants. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2025, 22, e14884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Shikha, D.; Sinha, S.K. DPPH radical scavenging assay: A tool for evaluating antioxidant activity in 3% cobalt–Doped hydroxyapatite for orthopaedic implants. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 13967–13973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.M.; Alanazi, A.H.; Alzaid, M.M.; Moustafa, S. Harnessing wasted mushroom peel aqueous extract for mycogenic synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for solar photocatalysis and antimicrobial applications. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 20991–21006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, L.S.; Alghamdi, M.D.; Alshahrani, A.A.; Alotaibi, N.F.; Moustafa, S.M.; Ashammari, K.; Alruwaili, I.A.; Nassar, A.M. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine-B and water densification via eco-friendly synthesized Cr2O3 and Ag@Cr2O3 using garlic peel aqueous extract. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilel, H.; Abdelzaher, H.M.; Moustafa, S.M. Biochemical profile, antioxidant effect and antifungal activity of Saudi Ziziphus spina-christi L. for vaginal lotion formulation. Plant Sci. Today 2023, 10, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aldogman, B.; Bilel, H.; Moustafa, S.M.N.; Elmassary, K.F.; Ali, H.M.; Alotaibi, F.Q.; Hamza, M.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; El-Ghorab, A.H. Investigation of chemical compositions and biological activities of Mentha suaveolens L. from Saudi Arabia. Molecules 2022, 27, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bień, D.; Lange, A.; Matuszewski, A.; Ostrowska, A.; Klimek, M.; Batorska, M.; Jaworski, S. Biocompatibility and antioxidant effects of hydroxyapatite-quercetin composites: In vitro and in ovo studies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.