Abstract

The rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complex fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL) has previously demonstrated promising luminescent properties, enabling its direct application as a probe for walled cells such as Candida albicans and Salmonella enterica. In this new study, we present a significantly expanded and comprehensive characterization of ReL, incorporating a wide range of experimental and computational techniques not previously reported. These include variable-temperature 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, CH-COSY, single-crystal X-ray diffraction, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT calculations, Fukui functions, non-covalent interaction (NCI) indices, and electrochemical profiling. Structural analysis confirmed a pseudo-octahedral geometry with the bromide ligand positioned cis to the epoxy group. NMR data revealed the coexistence of cis and trans isomers in solution, with the trans form being slightly more stable. DFT calculations and aromaticity descriptors indicated minimal electronic differences between isomers, supporting their unified treatment in subsequent analyses. Electrochemical studies revealed two oxidation and two reduction events, consistent with ECE and EEC mechanisms, including a Re(I) → Re(0) transition at −1.50 V vs. SCE. Theoretical redox potentials showed strong agreement with experimental data. Biological assays revealed a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells, contrasting with previously reported low toxicity in microbial systems. These findings, combined with ReL’s luminescent and antimicrobial properties, underscore its multifunctional nature and highlight its potential as a bioactive and imaging agent for advanced therapeutic and microbiological applications.

Keywords:

rhenium tricarbonyl; Fukui; NCI; aromaticity; cyclic voltammetry; X-ray; hirshfeld surface; HeLa 1. Introduction

Extensive research has been dedicated to rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes, resulting in various categories of complexes with adjustable structural characteristics [1,2]. The geometrical and optical properties of these complexes have also been explored using computational relativistic methods [3,4]. The first report on the photophysical properties of neutral fac-[Re(CO)3(N,N)X] complexes (where N,N is 1,10-phenanthroline and X is Cl) was described by Wrighton, M. & Morse, D. L. in 1974 [5,6]. Since then, compounds of this kind have been extensively studied, resulting in the discovery of numerous luminescent rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes with the following architecture: fac-[Re(CO)3(N,N)X]n. Here, N,N signifies a bidentate diimine ligand in an equatorial orientation, X designates a halide ligand serving as an ancillary component, and n represents the charge that can assume values of either 0 or 1+ [7]. These complexes have been found to possess remarkable properties for use in catalysis, as photoluminescent probes, and even in biological applications [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The most red-shifted emission wavelength of these rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes exhibits no discernible correlation with either the solvent polarity or excitation wavelength, revealing a substantial Stokes shift exceeding 200 nm. These characteristics underscore the noteworthy alteration in the dipole moment between the ground and excited states [15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

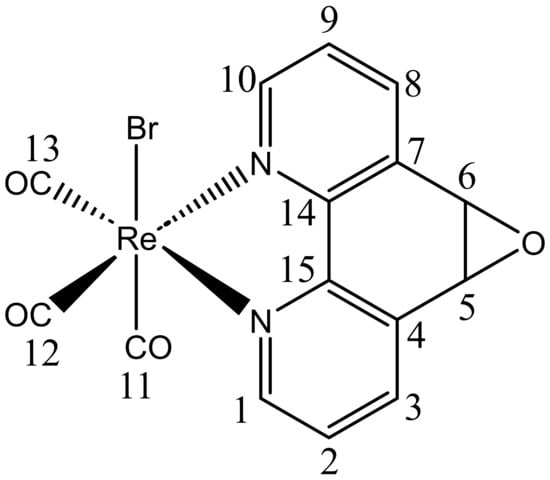

The neutral fac-[Re(CO)3(N,N)L] isomer is the most studied complex in this family due to its tunable photophysical properties, which are closely related to its structural variations [22,23,24]. Recent studies have also explored the potential of rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes in biological applications [25,26]. For example, rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes with neutral N,N-bidentate formazans have demonstrated potential applications in photodynamic therapy [27,28]. Another study reported unexpectedly high cytotoxicity of rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes bearing 1, 10-phenanthroline derivatives [29]. Some studies have shown that these complexes can selectively target cancer cells and induce cell death, as exemplified by the photosensitization of reactive oxygen species and DNA intercalation [29,30]. Additionally, neutral rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes have been used as catalysts in organic synthesis, where they have shown high activity and selectivity for various reactions [31,32]. Overall, rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes are promising compounds with diverse applications in various fields. Recently, we reported a novel neutral fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] complex, referred to as ReL [33], Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of ReL. Numbers correspond to carbon atoms labels.

This complex comprises two isomeric forms, cis and trans, distinguished by the position of the hydrogen atoms in the equatorial ligand with respect to the bromide. At 25 °C, the trans-isomeric form predominates [33]. In our previous investigation, we characterized ReL using physicochemical techniques and conducted UV–Vis and photoluminescence experiments in organic solvents of varying polarities. Remarkably, ReL displayed favorable properties as a luminescent probe when examining Gram-negative bacteria (Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium) and yeasts (Candida albicans) using confocal microscopy [26]. Interestingly, although it has been proposed that rhenium(I) complexes must be cationic to stain walled cells (e.g., bacteria and fungi), ReL is neutral [33]. In this study, we present a comprehensive spectroscopic characterization of ReL using 1D and 2D NMR and FTIR spectroscopy. Furthermore, the molecular structure of ReL was determined using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD). To further characterize its molecular properties, Hirshfeld surface analysis and Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, including geometry optimization, Fukui function analysis [34], and Noncovalent Interaction (NCI) index calculations [35] were conducted. Additionally, Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) was performed to assess the contribution of the equatorial ligand L (5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline) to the redox processes of ReL complex. To distinguish the rhenium core-associated redox processes, we compared the CV of ReL with L ligand profiles. Moreover, computational studies were employed to estimate the redox potentials, following a thermodynamic cycle approach to calculate the free energies and electron density plots. This characterization provides valuable insights into the electronic properties of such complexes. Finally, other authors have reported examples of [Re(CO)3(N,N)X] complexes with strong potential for development as chemotherapeutic agents. Based on this, ReL was evaluated for its cytotoxic potential in HeLa cervical cancer cells through the MTT assay.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL)

The rhenium(I) complex ReL was obtained in good yield by reacting [Re(CO)3Br(THF)]2 with ligand L in a 1:2 ratio. Its structure was confirmed by 1H NMR and FTIR using the KBr pellet method, which revealed three distinct ν(CO) bands, indicating a loss of local symmetry around the Re(CO)3 core. This complements previously published ATR-FTIR data from our group [36,37]. Characteristic features of the fac-isomers were observed, including a narrow symmetric band and two broader antisymmetric bands of comparable intensity (Figure S1). These spectral features align with the fac geometry confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, discussed below. Importantly, the absence of IR signatures typical of mer-isomers, such as a significantly weaker high-frequency band, supports the exclusive formation of the fac-isomer in this system. The 1H NMR spectrum of ReL in deuterated DMSO at 25 °C (Figure S2a) showed well-resolved signals for the 1,10-phenanthroline ring, consistent with previous reports (Figure S2b). The epoxy group displayed a split signal at approximately 5.09 ppm (5.15 and 5.05 ppm), suggesting the presence of an isomeric mixture. This splitting is attributed to the different spatial orientations of the epoxide relative to the bromide ligand, which supports the coexistence of cis and trans-fac-isomers. Similar behavior has been reported for related rhenium(I) complexes by Martí et al. [38]. In the complex fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Cl], only the trans isomer, where the epoxide group is oriented opposite to the chloride ligand was successfully isolated and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, despite the synthesis producing both fac isomers. To confirm the coexistence of these species in solution, 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C and 60 °C in deuterated DMF. At 25 °C, the protons adjacent to the epoxide appeared as a single resonance near 5.10 ppm, attributed to the cancellation of opposing electronic effects in the cis and trans forms. Upon heating to 60 °C, this signal resolved into two distinct peaks, indicating the presence of both isomers. These species differed in the orientation of the epoxide relative to the chloride ligand (cis/trans). At room temperature, chemical shift differences were effectively compensated, resulting in coincident resonances; increasing the temperature altered solvent properties, reducing this compensation and enabling signal separation. This behavior confirmed that the complex existed as a mixture of two stable fac isomers rather than a fac/mer equilibrium, consistent with IR and 13C NMR data. In our case, the complex ReL crystallized as the cis isomer, as verified by X-ray diffraction. In its 1H NMR spectrum at 25 °C in deuterated DMSO, the vicinal epoxide protons exhibited a narrow splitting at 5.15 ppm and 5.05 ppm, reflecting two distinct environments depending on the epoxide’s position relative to the bromide ligand (cis or trans). Variable-temperature 1H NMR experiments at 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C (Figures S3–S5) revealed consistent splitting patterns, further supporting the presence of two stable fac isomers rather than a fac/mer equilibrium. Additionally, the 13C-NMR spectra at 25 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C (Figures S6–S9) showed a stable resonance at 197.4 ppm assigned to the carbonyl ligands, along with split signals for the phenanthroline moiety. A CH-COSY experiment at 25 °C (Figure S10) confirmed these assignments. Unlike the chloride analog reported by Martí et al., which only crystallized in the trans form, ReL exhibited clear evidence of isomeric coexistence in solution. Notably, no significant spectral changes were observed when lowering the temperature from 60 °C to 25 °C, suggesting that the bromide ligand influences the rhenium core differently than chloride. This hypothesis was further supported by the DFT calculations discussed in the following section. Importantly, the 1H-NMR spectra of ReL showed no detectable impurities (Figure S2a,b), confirming the sample purity. For more details, see the ESI.

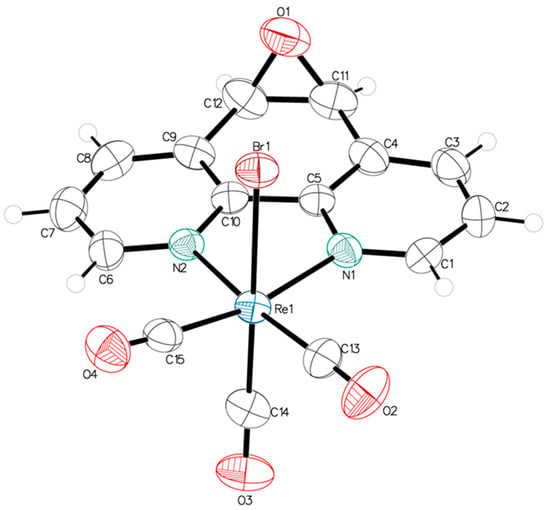

2.2. X-Ray Structure of ReL

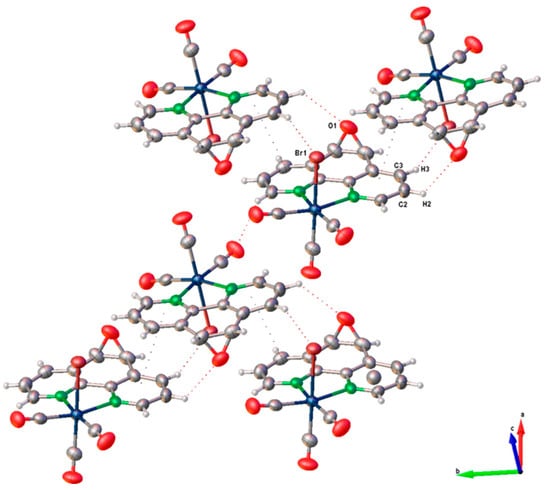

A single crystal suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis of fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL) was successfully grown, exhibiting the cis isomer with respect to the bromide and epoxy group positions. ORTEP drawings of the ReL compound and the atom numbering scheme are shown in Figure 2. ReL crystallized in the orthorhombic P212121 space group, with one molecular entity in the asymmetric unit (Table S1). The Re(I) metal center exhibited a slightly distorted octahedral coordination geometry. This geometry is characterized by three facially oriented carbonyl ligands. The diamine L coordinates the complex in the equatorial plane. An axial bromide ancillary ligand is also positioned cis to the epoxy group, completing the octahedral geometry. The Re−CO bond distances observed in this study are consistent with those reported for similar Rhenium(I) complexes [39]. Notably, the Re−CO bond length trans to the pyridyl group is slightly shorter (1.905 (7) Å) than the Re−CO bonds trans to the bromide ligand (1.914 (7) Å). This difference highlights the influence of the epoxy ring, which is positioned cis to the bromide ancillary ligand, on the bond length of the entire Re−Br (2.6158 (7) Å) moiety. The bond distances and angles are listed in Table S2. The intermolecular interactions constituting the crystalline packing of the ReL structure reveal that the crystals are stabilized by intermolecular hydrogen bonds C(2)-H(2)⋅⋅⋅O(1) between O(1) of the epoxide fragment and the C(2) of the phenanthroline fragment, as well as C(6)-H(6)⋅⋅⋅O(2) among the carboxyl groups in the phenanthroline fragment (Table S3). These interactions are related through a twofold screw axis parallel to the b axis. Additionally, the crystal packing is further stabilized by the C(3)-H(3)⋅⋅⋅Br(1) intermolecular interactions between the Br(1) ligand and the C(3) of the phenanthroline fragment, which are related through a twofold screw axis parallel to the b axis (Figure 3). Finally, π⋅⋅⋅π interactions were observed between the phenanthroline fragments, characterized by an angle of 2.080°, a centroid-centroid distance of 3.857 Å, and a shift distance of 1.639 Å, mediated by a two-fold screw axis parallel to the b-axis.

Figure 2.

ORTEP view of the molecular structure of ReL. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability.

Figure 3.

Crystal packing pattern of ReL.

The crystal packing arrangements of ReL and the analogous complex fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Cl] (Figure S11) exhibited notable differences in their π···π stacking interactions. In ReL, these interactions were more prominent, as indicated by a shorter centroid-to-centroid distance (3.857 Å), a smaller interplanar angle (2.089°), and reduced slippage (1.638 Å). In contrast, the chloride-containing complex displayed slightly weaker π···π stacking, with corresponding values of 3.942 Å, 4.986°, and 1.733 Å. These structural parameters suggest a more efficient π-stacking arrangement in ReL, which may contribute to enhanced crystal stability and packing density.

A comparative analysis of the dominant intermolecular contacts in both structures highlights the differing contributions of hydrogen bonding and π-stacking interactions to the overall supramolecular architecture. While both types of interactions are present in ReL and its chloride analog, the packing of ReL is primarily governed by π···π stacking, whereas the chloride complex exhibits a more balanced interplay between hydrogen bonding and π-interactions. These observations underscore the significant influence of halide substitution on modulating non-covalent interactions and crystal packing behavior in rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes, suggesting that the bromide ligand influences the rhenium core differently from chloride. On the other hand, the crystal structure of ReL was analyzed using Hirshfeld surface mapping and fingerprint plots, revealing the nature and relative contributions of intermolecular interactions (Figure S12). The dominant contacts were O···H (38.9%), associated with hydrogen bonding, followed by Br···H (10.0%) and C···C (6.5%), linked to dipole–dipole and π–π interactions, respectively. This analysis provides insights into the non-covalent forces stabilizing crystal packing. For more details, see the ESI.

2.3. DFT Studies: Geometries Optimizations, Fukui Index, NCI Analysis and Aromaticity

The structural and electronic features of fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL) were examined to clarify the subtle differences between its cis and trans isomers. These isomers arise from the relative orientation of the bromide ligand in the rhenium tricarbonyl core with respect to the epoxy group of the phenanthroline ligand. As described in Section 2.1, both forms coexist in solution and resist conventional separation, which explains why the electrochemical measurements reflect the properties of their mixture rather than those of the isolated species.

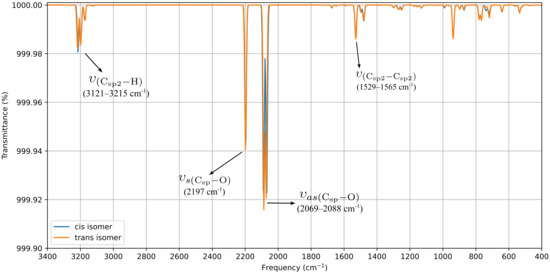

DFT optimization and vibrational analyses revealed no significant electronic or structural differences between the cis and trans isomers (Figure 4). The computed FTIR spectra reproduce the three characteristic CO stretching bands: the symmetric νCO vibration at 2197.0 cm−1 matches the experimental value (Figure S1), whereas the antisymmetric modes are calculated in the 2069.0–2088.0 cm−1 range. The third band, absent from the experimental spectrum, can be attributed to the trans influence of bromide, which reduces the splitting between the antisymmetric modes to only 19.0 cm−1. A detailed comparison of both forms is provided in the SI (Figures S13 and S14), confirming their near-identical behavior at the molecular level. This effect stems from the reduction in symmetry induced by the epoxy substituent. The enthalpy difference between cis and trans, only 2.74 kJ·mol−1, indicates a slightly greater stability of the trans isomer, which is consistent with the minor chemical shift splitting observed in the experimental 1H-NMR spectrum (5.10 and 5.07 ppm for cis and trans isomers, respectively, see Figure S2a).

Figure 4.

Computed FTIR for ReL of cis and trans isomeric form (with respect to epoxy-1,10-phenanthroline moiety and bromide ancillary ligand).

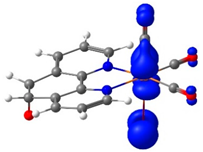

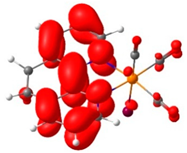

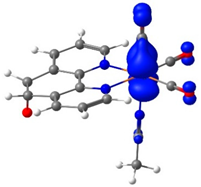

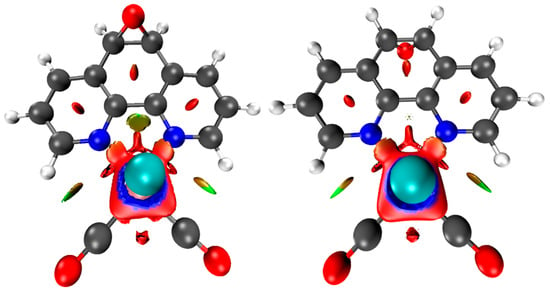

The electronic reactivity was analyzed using Fukui functions (FF). The FF characterizes the variation in electron density upon the addition or removal of electrons, providing insight into the most electrophilic and nucleophilic regions of a molecule [40,41,42]. According to Sebthilkumar et al. [43,44], these functions can be computed using specific equations [45,46]. In this study, the FF values for the cis and trans isomeric forms of ReL were calculated in the gas phase using the BP86 functional and the def2-TZVPP basis set. The SARC-ZORA-TZVPP basis set was employed to account for the relativistic effects on the rhenium atom. For both isomers, the nucleophilic sites (ƒ+) were concentrated on the phenanthroline nitrogen atoms and adjacent carbons, while the electrophilic regions (ƒ−) were located on the bromide ligand and the rhenium center (Figures S15 and S16). The close similarity between the cis and trans distributions indicates that the orientation of the bromide relative to the epoxy group does not substantially affect the electron-density response.

Noncovalent Interaction (NCI) analyses [47,48] offer a complementary perspective. The NCI index identifies interactions within a chemical system based solely on electron density. A two-dimensional graphical representation provides a detailed characterization of these interactions. Both forms exhibited π–π stacking and halogen bonding consistent with the crystal packing shown in Figure 3, while the reduced density-gradient plots confirmed weak interactions around bromine and essentially no differences in the phenanthroline or epoxy regions (Figure 5). A broader view of the non-covalent interactions can be observed on Figures S17 and S18. A faint Van der Waals contact between bromide and the aromatic framework was observed in the cis isomer, but overall, the interaction landscape was nearly identical. Notably, the epoxy oxygen consistently withdraws electron density from the phenanthroline ring, an effect that is insensitive to the position of the neighboring hydrogens.

Figure 5.

Upper view of the NCI plot for the cis (left) and trans (right) isomeric forms, revealing different van der Waals interactions. These calculations were performed at the BP86 and def2-TZVPP levels.

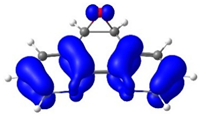

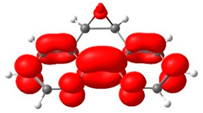

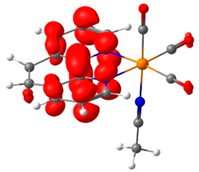

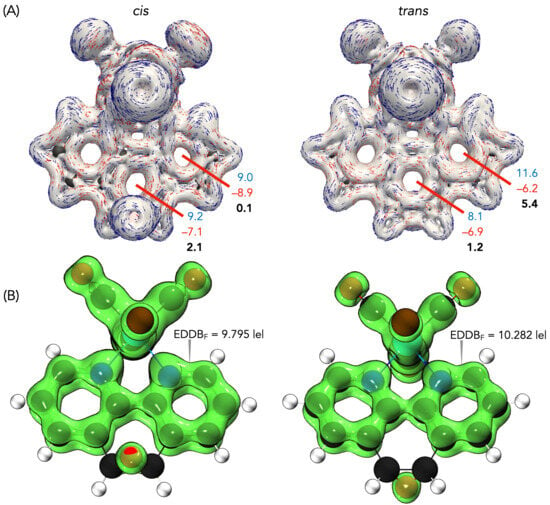

Finally, the aromaticity descriptors highlighted the subtle electronic distinction between the isomers. Aromaticity remains a fundamental concept in molecular chemistry as it provides essential insights into the stability, geometry, and magnetic behavior of cyclic systems [49]. Despite the absence of a strictly formalized definition, aromaticity is conventionally assessed through a variety of criteria, including energetic, structural, magnetic, and electronic factors. Each of these criteria reflects distinct aspects of electron delocalization [49,50]. The evaluation of aromaticity was carried out using magnetically induced current density (MICD) calculations at the BP86 level. For Re, a fully relativistic small-core effective potential (ECP60MDF) with its associated segmented valence basis set was employed, whereas the def2-TZVP basis set was used for the remaining atoms. The diatropic (aromatic) and paratropic (antiaromatic) ring currents were assessed using two integration planes. Positive net ring-current strength (RCSnet) values are indicative of aromatic character, whereas negative values are associated with antiaromaticity. MICD calculations revealed diatropic currents along the phenanthroline perimeter and paratropic contributions within its internal rings (Figure 6a). In the cis isomer, these currents were weak, with RCSnet values of 2.1 nA·T−1 for the central ring and nearly negligible contributions from the lateral rings. In contrast, the trans isomer sustained stronger local aromaticity in the lateral rings (RCSnet = 5.4 nA·T−1), while the central ring remained weakly aromatic (1.2 nA·T−1). The EDDB values support this view, confirming greater delocalization in the lateral rings of the trans isomer, in agreement with Hückel’s rule and Clar’s description of the sextet localization in phenanthroline (Figure 6b). The slightly higher delocalization in the trans isomer correlates with its marginally greater thermodynamic stability.

Figure 6.

(a) Modulus of current density and vector flux with an isovalue of ±0.05 of cis and trans forms of ReL. Integration planes (red) used to determine the intensity of the current densities in nA·T−1. Diatropic values are in blue, paratropic values are in red and net values are in bold. (b) EDDBF isosurfaces with the corresponding electron populations for the cis and trans forms of ReL.

Taken together, these results indicate that cis and trans ReL share nearly identical structural and electronic frameworks, with the only appreciable difference being the enhanced local aromaticity of the lateral rings in the trans isomer. This distinction, although modest, explains its slight thermodynamic preference and supports treating the isomeric mixture as a unified species in electrochemical and biological studies.

2.4. Cyclic Voltammetry

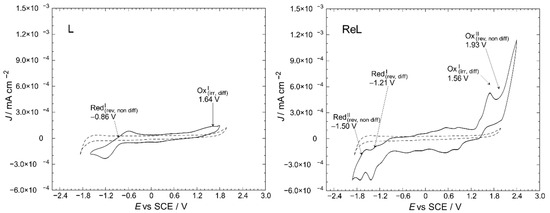

Electrochemical measurements of ReL were performed on its isomeric mixture, as individual contributions from the cis and trans forms could not be experimentally resolved. Computational studies revealed negligible differences in energy and non-covalent interactions between the isomers, indicating that the relative orientation of the epoxide and bromide ligands did not significantly influence the redox behavior (See Section 2.3). Therefore, the observed metal-centered oxidation and ligand-centered reduction processes are considered representative of the entire mixture. The redox properties of transition-metal complexes are known to depend on several factors, including the oxidation state of the metal center, the electronic characteristics of the ligands, and the solvent and electrolyte environment [51,52]. The cyclic voltammograms of ReL and its uncoordinated equatorial ligand (L) are shown in Figure 7, enabling a direct comparison of their redox profiles and the identification of metal- and ligand-centered processes.

Figure 7.

Cyclic voltammetry profiles of the L and ReL compared to blank (dashed line). Interface: Pt|10−3 mol/L of the respective compound +10−1 mol/L of TBAPF6 in anhydrous CH3CN under an argon atmosphere. Scan rate: 200 mV/s.

Here, one can notice the differences between the profiles for a blank solution and the respective compounds. The L displayed oxidation and reduction signals at 1.64 and −0.86 V vs. SCE, respectively. For ReL, two irreversible oxidations were found at 1.56 and 1.93 V, and two quasi-reversible reductions were found at approximately −1.21 and −1.50 V.

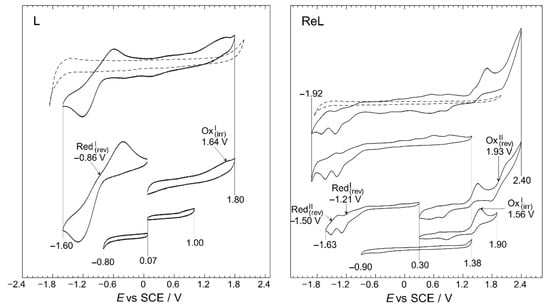

A working window study was performed to identify the electrodic processes for the L and ReL, the relation between them, and reversibility, Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Working-window study CV profiles of the L and ReL compared to blank (dashed line). Interface: Pt|10−3 mol/L of respective compound+10−1 mol/L of TBAPF6 in anhydrous CH3CN under an argon atmosphere. Scan rate: 200 mV/s.

The working-window study (Figure 8) shows that the L and ReL display typical behaviors observed for analogous compounds studied before. The working window study for L exhibited an intense quasi-reversible reduction, RedI, process at a half-wave potential of −0.86 V and a low-intensity irreversible oxidation at 1.64 V. These signals have been previously identified for similar dinitrogenated (N,N) ligands [16,53,54,55,56]. For the ReL complex, various oxidation and reduction processes were observed in the full potential window (−1.92 to 2.40 V vs. SCE) in the cyclic voltammogram shown in Figure 8. However, if the CV profile from the bottom of the figure is inspected (−0.90 to 1.38 V vs. SCE), none of these signals are observed in the wider potential range CV profile and do not correspond to impurities since few were detected by 1H-NMR (Figure S2a). Precisely, when the anodic limit reaches 1.90 V a reduction is observed 0.85 V after potential-sweep inversion. Thus, this reduction could belong to oxidated products formed after the 1.56 V process, possibly indicating that OxI may also be considered a quasi-reversible process. On the other hand, when anodic limit reaches 2.40 V, another reduction signal appears at 0.50 V. Due to the separation between 0.50 and 1.93, it is unlike that the reduction at 0.50 is related to the oxidation’s products from 1.93 V; more likely corresponds to a reduction from solvent oxidation by-products. All in all, only two oxidations were observed for ReL: an irreversible process occurring at 1.56 V, followed by another irreversible process at 1.93 V. In addition, two quasi-reversible reductions are observed at −1.21 and −1.50 V, respectively. This behavior is consistent with past outcomes on similar molecules [57,58].

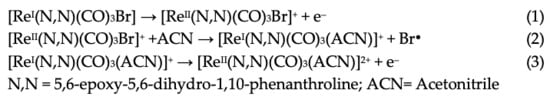

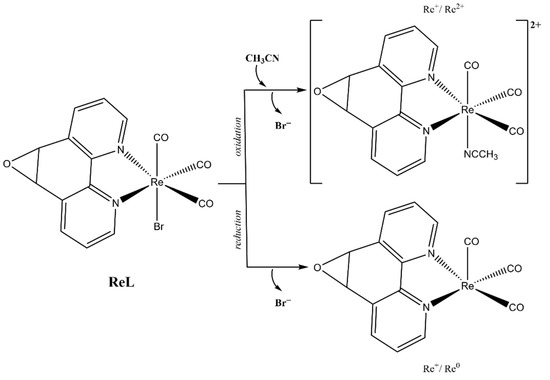

The first oxidation at 1.56 V for ReL corresponds to a (1) single electron irreversible oxidation of rhenium center ReI→II, followed by an (2) intramolecular fast reduction ReII→I, with an immediate substitution of bromide radical by a solvent molecule. We then observed a second (3) irreversible oxidation at 1.93 V, producing a dicationic species. Thus, the complete oxidation process followed an electrochemical–chemical–electrochemical steps mechanism (ECE) (Scheme 1), which was previously reported for similar complexes containing different diimine (N,N) ligands [59,60,61].

Scheme 1.

Reaction mechanism for ReL oxidations at 25 °C.

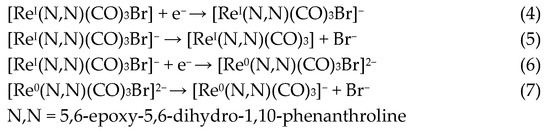

Regarding the reductions in the ReL complex, two quasi-reversible processes are observed in Figure 7 and Figure 8. These reductions have been extensively reported as two single-electron processes: the first one at −1.21 V potential (4) belongs to the quasi-reversible reduction of the L, followed by (5) reversible bromide elimination.

The second at −1.50 V potential (6) corresponds to the reversible reduction from the rhenium center ReI→0, generating a dianionic species that may also go through a (7) bromide elimination step. Thus, the reduction follows the electrochemical-electrochemical–chemical mechanism (EEC) with bromide dissociation as the chemical step (Scheme 2). Similar mechanisms have been described for the reduction of other rhenium(I) complexes. Bromide removal is considered reversible because it is coupled to a redox process that generates a coordinatively unsaturated species, which has the capacity to recapture the bromide [57,61].

Scheme 2.

Reaction mechanism for ReL reductions at 25 °C.

The general reaction scheme for oxidations and reductions is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Electrochemical reaction scheme for ReL.

The observed reductions of ReL closely align with the position and nature of their individual constituents. Furthermore, computational studies on comparable systems emphasize the evenly distributed LUMO above the (N,N) ligand and the rhenium core [53,57]. Scan rate studies were performed to determine whether the current of the electrodic processes depended on the species diffusion. As shown in Figure S19, the current increased with the scan rate, as expected. As can be seen from the summary presented in Table 1, mass transfer control is present in some of the electrodic processes displayed by the molecules under study.

Table 1.

Summary of the electrochemical processes.

Complementarily, a voltammetry experiment was conducted in a CO2-saturated solution (Figure S20) to preliminarily check a possible electrocatalytical potential of the complex towards CO2 reduction process. An increase in the current density was observed, which may be associated with the CO2 reduction processes [62,63]. These results suggest a possible influence of the complex on the process, which must be rigorously evaluated through further studies. Future studies will involve modifying electrodes with these complexes to systematically investigate their catalytic behavior during the reduction ReI→0 processes [4,52]. To better understand the metallic center reduction process ReI→0, the half-wave potentials for a family of compounds measured in identical conditions are presented in Figure S21 [4,57]. As expected, some trends can be observed on the ReI→0 potential depending on the size of the ligands and/or nature of the moieties present. On the one hand, the presence of the ancillary ligand corresponding to a Schiff base (red dashed enclosure) showed the most negative values. In previous studies [53,57], the ancillary ligand exhibited a withdrawing effect to the rhenium core, as evidenced by UV–Vis spectroscopy, theoretical calculations, and other methods. These reports have pointed out that this kind of ancillary ligand leads to a less intense electron density on the rhenium core, which could explain why the reduction processes require higher potential values. In the middle, the complexes with a halide ion as a ligand (blue line) were observed. Finally, the most positive potential value for ReI→0 belongs to the complex with a benzimidazole ligand. This ligand appears to influence the homogeneous distribution of electron density in the rhenium core. Thus, the reduction in the observed potential values in this Re complex family is strongly influenced by the aromaticity due to the nature of the substituents in the ligands’ moiety. Reduction processes for this type of compound are important in the study of potential electrocatalytic capabilities for the carbon dioxide reduction process [64,65,66].

2.5. Computed Oxidation and Reduction Potentials of ReL

To better understand the redox processes described in Section 2.4, we employed a computational methodology using a thermodynamic cycle to calculate free energies in both the gas-phase and solvated states. The CPCM model with acetonitrile as the solvent was used to estimate the solvation energies. We found oxidation and reduction potentials at +2.04 V and −0.92 V, respectively, for L, which agree with the experimental trends (Table 2).

Table 2.

Electrochemical values of L and ReL complex (experimental data and theoretical calculations).

As observed after 1H-NMR analysis (Figure S2a,b), both isomers are present in the solution. For the computational calculations, only one of the isomeric structures (trans) was considered, as the other isomer is expected to exhibit similar properties based on previous computational studies. For ReL, we identified two oxidation processes at +1.45 V and +2.11 V, which agree with experimental data at +1.56 V and +1.93 V, respectively. These processes were attributed to rhenium oxidation following an electrochemical–chemical–electrochemical mechanism (see discussion above). Regarding the reduction, two processes are calculated at −1.31 and −1.95 V (see Table 2), consistent with the reduction of the L equatorial ligand at −1.21 V and the reduction of ReI→0 at −1.50 V, respectively.

To complement these findings, electron density plots were calculated for the L and the ReL complex (see Table 2). The analysis focused on the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) to identify the most probable oxidation site. For the L, the HOMO is primarily localized in the 1,10-phenanthroline ring, with a minor contribution from the oxygen atom of the epoxy moiety (see Table 3). The significant potential difference in oxidation peaks observed in the calculations can be attributed to the electron-withdrawing effect of the 1,10-phenanthroline moiety, which increases the energy required to oxidize the epoxy group in L. In contrast, the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) is predominantly distributed across the fused aromatic rings.

Table 3.

Electron density of molecular orbitals HOMO and LUMO involved in electrochemical steps of redox mechanisms for L, ReL and ReL-ACN complexes.

For the ReL complex, redox calculations indicated that the spatial modification of the epoxy group relative to the bromine ligand in the octahedral arrangement did not significantly alter the electronic properties. The HOMO and LUMO plots revealed that the electron density was primarily localized either on the metal core or within the aromatic ring system (Table 3). Specifically, the HOMO was concentrated in the rhenium tricarbonyl core rather than in the 1,10-phenanthroline ring, suggesting that oxidation is most likely to occur at the rhenium center (ReI→II). The experimental results revealed a second reversible oxidation at +1.93 V, suggesting the formation of a dicationic species. The ReL-ACN complex exhibited a HOMO distribution centered on the metal core, with a stabilization energy of ΔE = 2.50 eV. This value is lower than that obtained for the L (ΔE = 4.87 eV), confirming that oxidation is more likely to occur at the metal center. Regarding the LUMO, the electron density is primarily distributed in the 1,10-phenanthroline ring, indicating that reduction is more likely to occur in this region. Based on these analyses, ReL exhibited a characteristic cyclic voltammetry profile, beginning with an initial irreversible oxidation, followed by a second reversible oxidation that followed an electrochemical–chemical–electrochemical (ECE) mechanism. Additionally, the complex undergoes two reversible reductions processes consistent with the electrochemical–electrochemical–chemical (EEC) mechanism.

2.6. Cell Viability Assays

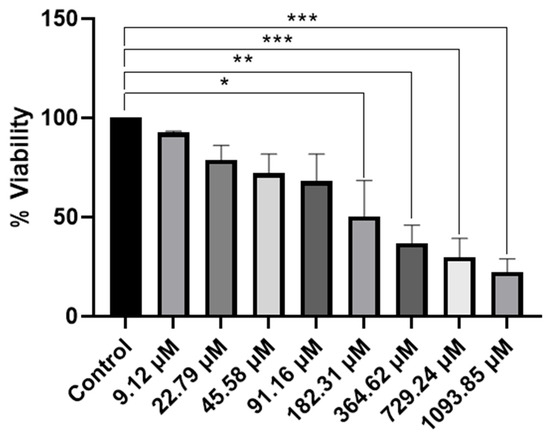

Rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes featuring dinitrogenated N,N′ ligands, such as 1,10-phenanthroline derivatives, combined with chloride or bromide as ancillary ligands have gained attention as promising candidates in anticancer research [67,68,69]. The incorporation of halides confers neutrality to these complexes, improving lipophilicity, cellular uptake, and physiological stability, critical attributes for effective drug delivery. These structural benefits correlate with significant cytotoxic activity against human cancer cell lines, notably HeLa (cervical cancer) [67]. Representative examples, including Re(CO)3(1,10-phenanthroline)Cl and its functionalized analogues, exhibit strong potential for development as chemotherapeutic agents [29,70]. Based on this, the proposed complex fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL) was evaluated for its cytotoxic potential in HeLa cervical cancer cells. The cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay, which revealed a measurable reduction in metabolic activity, suggesting that ReL may exert cytotoxic effects under the tested conditions [71,72], Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Evaluation of cell viability of ReL complex by a MTT assay in HeLa cells. A An MTT assay was performed to evaluate cell viability in the presence of the complex, dissolved in DMSO to obtain final concentrations of 9.12 µM, 22.79 µM, 45.58 µM, 91.16 µM, 182.31 µM, 364.62 µM, 729.24 µM and 1093.85 µM. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to that of the control group. Analyses were performed with n = 3 and evaluated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Symbol (*) indicates a statistically significant difference with p < 0.05. Group differences versus control were evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. Significance codes: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 (two-sided; posthoc– adjusted where applicable).

The MTT assay provided comprehensive information on the cytotoxic effects of the ReL complex. A reduction in cell viability was observed, which depended on the concentration, indicating that ReL demonstrates cytotoxic activity under the conditions tested. The lowest concentration of the compound exhibited behavior like that of the control. Subsequently, at concentrations of 22.79 µM, 45.58 µM, and 91.16 µM, a decrease in cell viability was observed, suggesting an early onset of biological activity; however, these differences were not statistically significant. This trend was accentuated at concentrations of 182.31 µM and 364.62 µM, where significant cytotoxic effects were detected (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively). At higher concentrations (729.24 µM and 1093.85 µM), cell viability was reduced to below 40% compared to control, with highly significant differences (p < 0.0001). Therefore, ReL complex demonstrated a clear concentration-dependent cytotoxic effect, characterized by a progressive reduction in cell viability as the dose increased.

Cell viability of fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] decreased in a dose-dependent manner, with significant reductions observed at 182.31 μM and above, yielding an IC50 of 182.31 μM. In contrast, neutral rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes bearing unmodified phenanthroline ligands typically display much higher potency, with reported IC50 values of 1.2–1.8 μM, surpassing cisplatin (6.6 μM) [25,29,67,73]. Although the bromide ligand may enhance lipophilicity, this effect does not offset the structural constraints imposed by the epoxide modification, highlighting the critical role of rational ligand design in achieving optimal biological performance [29,67]. Importantly, replacing the bromide ligand with a neutral donor that enables formation of cationic species could improve aqueous solubility and facilitate endocytotic uptake, potentially lowering IC50 values to levels comparable with other highly active rhenium tricarbonyl analogues reported in the literature [74]. Complexes bearing benzimidazole or bipyridine derivatives typically display IC50 values in the 50–100 μM range, depending on ligand lipophilicity and substitution patterns [67]. Neutral complexes of the type fac-[Re(CO)3(Phenathroline)Cl or Br] are attractive as activatable precursors [29,75]. These features suggest their potential as prodrug candidates that could be activated in biological environments, although further optimization is required to improve stability and lipophilicity. These considerations highlight the need for rational ligand modification to optimize both physicochemical properties and anticancer activity [76].

In brief, the ReL complex exhibited a clear dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells, with an IC50 significantly higher than cisplatin. This relatively low toxicity indicates that ReL could potentially meet key requirements for an effective fluorophore, including minimal cytotoxicity, high photostability, and efficient cellular uptake without permeabilizing agents, ensuring reliable bioimaging in epithelial (non-walled) cell models while preserving cell viability [26]. Interestingly, previous studies reported that ReL interacts effectively with walled cells such as Gram-negative bacteria and yeasts, showing minimal or no cytotoxicity, while significant effects were observed against Gram-positive bacteria, suggesting a selective biological response. Moreover, its intrinsic luminescent properties enable direct application as a fluorescent probe for microbial imaging, particularly in Salmonella enterica and Candida albicans [33]. These findings highlight the multifunctional nature of ReL, combining imaging capability with selective bioactivity and underscoring its potential as a versatile tool for microbiological applications.

3. Experimental and Theoretical Details

3.1. Materials and Instruments

The initial reagents, sourced from Merck and Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), were used as received, without additional purification. Acetonitrile (CH3CN) was dried using molecular sieves and purged with argon gas in preparation for the electrochemical experiments. The synthesis and comprehensive characterization of the rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complex are described in detail. Additional methodological, crystallographic, and computational details are provided in Appendix A

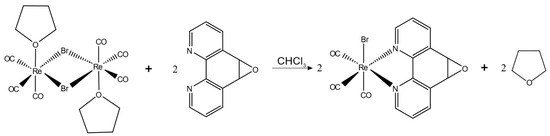

3.2. Synthesis of fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL)

The complex was prepared following a previously documented method, which involved the reaction of L with the [Re(CO)3Br(THF)]2 dimer in a 2:1 ratio in toluene. The mixture was stirred for 15 min at room temperature2. Reaction scheme is presented on Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Reaction scheme for the synthesis of ReL.

FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3433 (νNH); 2021 (symmetric νCO); 1909 (antisymmetric νCO); and 1435 (νCC). 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ = 9.13–9.07 [m, 2H, C1,C10], 8.76–8.65 [m, 2H, C3,C8], 7.94–7.82 [m, 2H, C2,C9], 5.10 [d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H,C6] and 5.08 [d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, C5]. 13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ = 197.40; 153.47; 150.93; 141.86; 133.89; 128.31; and 54.91.

For the characterization of ReL, we conducted FTIR spectra (ATR) using a Bruker Vector-22 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Billerica, MA, USA). Additionally, 1H-NMR, 13CNMR, and CHCOSY spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE 400 spectrometer (400 MHz) and maintained at 25 °C. The compound was dissolved in deuterated DMSO.

3.3. Structure Determination

Crystals suitable for X-ray analysis of compound ReL were obtained as previously described and mounted using MiTeGen Micro Mounts (New York, NY, USA). Table S1 presents the experimental and crystallographic data for ReL, while selected bond distances and angles for all the studied compounds are shown in Table S2. The intramolecular interactions are outlined in Table S3. Detailed information on the crystal, X-ray data collection, and structure solution is provided in the Supporting Information. Intensity data were collected at room temperature using a Bruker Smart Apex diffractometer (Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a bi-dimensional CMOS Photon100 detector and a graphite monochromator employing Mo-Kα radiation. A frame separation of 0.31 and a collection time of 10 s per frame were used at 296 K. APEX3 (Bruker AXS), SHELXL (Sheldrick), and the TONTO package integrated within CrystalExplorer 17.5 were used in their standard distributions. Data integration was performed using APEX3 software, with absorption corrections applied via SADABS. The solution and refinement for compound ReL were carried out with Olex2. The structure of ReL was solved using the Patterson method and refined with the SHELXL package through least squares minimization [77]. The refinement utilized full matrix least squares on reflection intensities (F2), with all non-hydrogen atoms refined anisotropically and hydrogen atoms positioned in idealized locations.

The intermolecular interactions in the crystalline molecules were studied using Hirshfeld surface analysis. This surface is defined as the fraction of the electron density sphere of the atoms of the molecule of interest, “promolecule” that contributes to the total electron density of the crystalline molecule “procrystal” system, considering a normalized contact distance (dnorm), where rVdW is the van der Waals (vdW) radius of the atom corresponding to the interior or exterior of the Surface (Equation (1)). For this reason, Hirshfeld surface analysis has gained prominence as a powerful tool to explore and describe various intermolecular interactions present in crystal packing. Furthermore, these surfaces are related to their corresponding 2D fingerprint plots [78,79,80,81]. This plot allows us to explore, quantify, and compare the contributions of the different interactions present in the crystal structure and helps to elucidate important information about close contacts and more distant interactions and areas where contacts are weak. Crystal Explorer 17.5 software [82] was used to calculate the Hirshfeld surface [78,79] and associated 2D-fingerprint plots [83,84] of the L1–4 compounds using the crystallographic information file (CIF) as input for the analysis. The electrostatic potentials were mapped on the Hirshfeld surfaces using the 3–21G basis set at the level of Hartree-Fock theory over a range of ±0.002 au using the TONTO computational package integrated into the program Crystal Explorer [82]. For the generation of fingerprint plots, the bond lengths of hydrogen atoms involved in interactions were normalized to standard neutron values (C-H = 1.083 Å, N-H = 1.009 Å, O-H = 0.983 Å) [85].

Equation (1): Normalized contact distance, defined in terms of de, di, and the VdW radii of the atoms. Red (distances shorter than the sum of VdW radii) through white to blue (distances longer than the sum of VdWradii).

3.4. Electrochemical Characterization

For all electrochemical studies, the working solution consisted of 0.01 mol/L of the respective compounds (L and ReL complex). This solution was supplemented with 0.1 mol/L of tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) as a supporting electrolyte. In this study, all CV experiments were conducted under standardized conditions using a platinum working electrode in anhydrous acetonitrile containing 10−3 mol·L−1 of the respective compound (L or ReL) and 0.1 mol·L−1 of tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) as the supporting electrolyte. Measurements were carried out under an argon atmosphere at a scan rate of 200 mV·s−1. The compounds and electrolyte were prepared in high p.a. anhydrous acetonitrile (CH3CN). Prior to each experiment, the working solution underwent purging with high-purity argon gas, with an argon atmosphere maintained throughout the experiment [4]. For carbon dioxide reduction experiments, the solution was purged with CO2, and a constant pressure of this gas was maintained during measurements. A polycrystalline, non-annealed platinum disc with a 2 mm diameter was used as the working electrode. The working electrode was polished with alumina slurry (particle size 0.3 µm) on soft leather, then rinsed with bi-distilled water, acetone, and finally dried before and between measurements. A platinum gauze of substantial geometrical dimensions was employed for the counter electrode, segregated from the primary cell compartment by a fine sintered glass. All recorded potentials in this document are referenced to Ag/AgCl electrodes in tetramethylammonium chloride to align with the potential of a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) at room temperature [86]. Electrochemical cells, syringes, volumetric flasks, and the rest of the employed glassware were always washed with bi-distilled water, acetone, and oven-dried at 60 °C for at least 12 h prior to all experiments. All electrochemical experiments were executed at room temperature, using a CHI900B bipotentiostat CH Instruments (Austin, TX, USA) interfaced with a computer running CHI 9.12 software. This software facilitated experimental control and data acquisition.

3.5. Theoretical Details

All calculations in this study were performed within the Density Functional Theory (DFT) framework using ORCA 5.0.4 [87]. Molecular geometries were fully optimized employing the B3LYP hybrid functional with the def2-TZVPP basis set. The Tight SCF convergence criteria and the RIJCOSX approximation were applied for Coulomb integral calculations to enhance computational efficiency. The solvation effects were estimated using the Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) [88,89], with acetonitrile as the solvent. Frequency analyses were conducted to obtain the thermodynamic parameters necessary for determining the reduction potentials.

For the Fukui function analysis, an optimization calculation was performed using ORCA 5.0.4 to obtain the electronic density of the neutral species. Density Functional Theory (DFT) was employed with the BP86 functional and the def2-TZVPP basis set [90,91,92]. For the rhenium atom, the SARC-ZORA-TZVPP basis set [92] was used to account for the relativistic effects associated with heavy metals. Adiabatic calculations were carried out to obtain the electronic density of the positively and negatively charged species. This approach assumes that the molecular geometry remains unchanged upon charge variation, which means that the geometric structures of the charged species are not re-optimized. Such an approximation is valid for systems in which the charge influence on geometry is minimal, as seen in radicals and other charged species where structural changes upon electron addition or removal are negligible. This adiabatic treatment simplifies the analysis and enables the study of the reactivity and electronic density of charged species without requiring geometric optimization for each charge state. To generate figures highlighting nucleophilic and electrophilic reactivity sites, Chemcraft 1.8 software was used to perform density subtraction operations.

The NCI approach relies on electron density and its derivatives, allowing the identification of noncovalent interactions based on the reduced density gradient (S) in low-density regions. Within this framework, the reduced density gradient is defined by the equation described for Trujillo et al. and Villegas-Escobar et al. [93,94]. The optimized structure from the Fukui function calculation of the neutral species was used for the NCI analysis. Multiwfn 3.8 software [95] was employed to generate .cube files to obtain density gradient data. The .cube files were then visualized using the VMD 1.9 software [96] to identify and display the different types of interactions within the structure. Additionally, Python programming language 3.12.12 script developed by our research group was utilized to generate RDG analysis figures.

The magnetically induced current density (MICD) was analyzed using the GIMIC program [97,98]. For a more detailed analysis of cyclic current Lows and to evaluate current profiles across selected integration planes, the planes were positioned perpendicular to the molecular plane. The ring currents and their intensities were then determined by integrating the current density across these planes. For this analysis, the Gauge Included Atomic Orbitals (GIAO) method [99] was used to study diatropic (aromatic) and paratropic (antiaromatic) ring currents circulating clockwise and counterclockwise, respectively. The two-dimensional Gauss-Lobatto algorithm was used to integrate the currents passing through an integration plane. The current density paths were done using Paraview5.10.0 [100]. Computations were performed by Gaussian 16.B015 with the BP86 (functional, in which a small-core fully relativistic effective core potential (ECP60MDF) [101] and associated segmented valence basis sets were adopted for Re and the def2-TZVP [102,103] basis set was used for the remaining atoms [101,104]. Also, aromaticity was evaluated by performing electron density of delocalized bonds (EDDB) calculations using EDDBRun scripts [105].

The methodology for computing the reduction and oxidation potentials was based on an established thermodynamic cycle approach [106,107,108,109]. This method calculates the free energy of the species in both gas-phase and solvated state. Separate thermodynamic cycles were used for each oxidation and reduction potential, as illustrated in Figures S22 and S23. To establish the computational protocol for estimating redox potentials, standard Gibbs free energies in acetonitrile were obtained from gas- and solution-phase calculations for the reduced and oxidized species. The gas-phase free energy was derived from single-point energy calculations. The standard absolute redox potential (E0) was determined using the following equation:

In the given equation, n represents the number of electrons consumed or generated in the specific half-reaction, and F denotes the Faraday constant. This thermodynamic model establishes a direct connection between the changes in the free energy in the condensed phase related to reduction or oxidation and the corresponding processes in the gas phase. Furthermore, to determine the free energy associated with ionization or electron attachment at 298 K, it is essential to calculate the thermal contributions to the free energy at 298 K. Considering this, the remaining link between the gas and the condensed phase is defined by the difference in solvation free energies between the oxidized and reduced species involved in the respective processes. The calculated absolute free energy of reduction or oxidation represents the generation or consumption of a free electron.

Additionally, the theoretical calculation of the free energy for the oxidation and reduction processes considers the complexity of the electrochemical mechanisms.

3.6. MTT Assay Protocol

HeLa cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), a recognized supplier of authenticated cell lines and microbial strains for biomedical research and diagnostics. The MTT assay is an established colorimetric method for assessing cell viability, based on the ability of living cells to reduce the tetrazolium (MTT) to a purple formazan [71,72]. This color change is indicative of cellular metabolic activity, as viable cells convert MTT into an insoluble product whose color intensity can be quantified to determine cell viability [72]. This assay was performed using a 96-well plate, in which 35,000 cells were seeded per well. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin. . Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. 200 µL of each prepared solution (9.12, 22.79, 45.58, 91.16, 182.31, 364.62, 729.24, and 1093.85 µM) was added to the respective cell well. Stock solutions were obtained by dissolving precise amounts of the compound in DMSO. Appropriate controls were included to ensure the reliability of the assay: the positive control consisted of culture medium alone, the negative control was DMSO, and the vehicle control was a mixture of culture medium and DMSO. These controls provided a baseline for evaluating the specific effects of this compound on cell viability.

The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. Subsequently, a 5 mg/mL MTT solution, diluted 1:10 in culture medium, was added to each well. The MTT incubation was continued for two hours to allow the conversion of MTT to formazan. After MTT incubation, 100 µL of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formazan complexes. The solution was carefully resuspended in each well to ensure complete dissolution of the formazan. Finally, absorbances at 570 nm and 630 nm were measured using a BioTek microplate reader. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage with respect to the control group. Analyses were performed with n = 3 and evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test [110,111].

4. Conclusions

In this study, we present a comprehensive structural, electronic, and biological characterization of a neutral rhenium(I) complex fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br] (ReL). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction confirmed the cis configuration, and Hirshfeld surface analysis revealed dominant O···H interactions in the crystal packing. Variable-temperature NMR spectroscopy demonstrated the coexistence of cis and trans isomers in solution, with the trans form being slightly more stable than the cis form. DFT calculations, including Fukui functions, NCI indices, and aromaticity descriptors, showed that both isomers share nearly identical electronic and structural frameworks, with enhanced local aromaticity in the trans isomer, which explains its slight thermodynamic preference. This supports the treatment of the isomeric mixture as a unified species in electrochemical and biological studies. Electrochemical studies revealed a typical fac-[Re(CO)3(N,N)X] profile, including a ReI → Re0 transition, with theoretical redox potentials aligning well with the experimental data. Biologically, ReL demonstrated dose-dependent cytotoxicity in HeLa cells, in contrast to its previously reported low toxicity in microbial systems. Combined with its luminescent properties and antimicrobial activity, these findings underscore the multifunctional nature of ReL and its potential as a bioactive and imaging agent for therapeutic and microbiological applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics14010003/s1, Figure S1: FTIR (KBr) spectrum of ReL; Figure S2: a. 1HNMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 400 MHz in DMSO-d6 at 25 °C; Figure S2: b. Expanded aromatic zone of the 1H-NMR spectrum of ReL at 400 MHz and 25 °C, with samples dissolved in deuterated DMSO; Figure S3: 1HNMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 400 MHz in DMSO-d6 at 40 °C; Figure S4: 1HNMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 400 MHz in DMSO-d6 at 50 °C; Figure S5: 1HNMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 400 MHz in DMSO-d6 at 60 °C; Figure S6: a. 13C NMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 100 MHz in deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) at 25 °C; Figure S6: b. Expanded aromatic zone of 13C NMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 100 MHz in deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) at 25 °C; Figure S7: 13C NMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 100 MHz in deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) at 40 °C; Figure S8: 13C NMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 100 MHz in deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) at 50 °C; Figure S9: 13C NMR spectrum of ReL recorded at 100 MHz in deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) at 60 °C; Figure S10: CH COSY spectrum of ReL recorded in deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) at 25 °C; Figure S11: Comparison of the crystal packing patterns of ReL and fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Cl] (CCDC-239411)* complexes; Figure S12: Hirshfeld surfaces mapped over dnorm (top) and 2D fingerprint plots of ReL (bottom) show the principal percentage contribution of contacts between complexes; Figure S13: Computed FTIR of cis isomeric form of ReL, with respect to epoxy moiety 1,10-phenenthroline and bromide ancillary ligand; Figure S14: Computed FTIR of the trans isomeric form of ReL, with respect to epoxy moiety 1,10-phenenthroline and bromide ancillary ligand; Figure S15: Plot of the Fukui function of the ReL cis isomeric form: the left plot indicates a nucleophilic site (f+), and the right plot indicates an electrophilic site (f−); Figure S16: Plot of the Fukui function of the ReL trans isomeric form: the left plot indicates a nucleophilic site (f+) and the right plot indicates an electrophilic site (f−); Figure S17: Noncovalent interaction (NCI) analysis of the cis-isomeric form of ReL. Bottom: The NCI color scale is −0.02 <λH> 0.02 a.u. These calculations were performed at the BP86 and def2-TZVPP level; Figure S18: Noncovalent interaction (NCI) analysis of the trans-isomeric form of ReL. Bottom: The NCI color scale is −0.02 <λH> 0.02 a.u. These calculations were performed at the BP86 and def2-TZVPP level; Figure S19: Cyclic voltammetry scan-rate study of L and ReL. Interface: Pt| 10−3 mol/L of respective compound + 10−1 mol/L of TBAPF6 in anhydrous CH3CN under an argon atmosphere. Scan rate: 25–200 mV/s; Figure S20: Cyclic voltammetry for CO2-electrocatalysis preliminary study. Interface: Pt| 10−3 mol/L of fac-Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)Br (ReL) + 10−1 mol/L of TBAPF6 in anhydrous CH3CN under saturated Ar(—) or CO2 (---). Scan rate: 100 mV/s; Figure S21: Half-wave potential values for Rhenium (I) tricarbonyl center reductions were determined for a family of fac-[Re(CO)3(N,N)X]n compounds; Figure S22: Thermodynamic free energy cycles used in the computation of equilibrium redox potentials for L: (A) L/L− pair and (B) L+/L pair; Figure S23: Thermodynamic free energy cycles used in the computation of equilibrium redox potentials for ReL complex: (A) FO/FR pair, (B) Different species (FO and FR) involved in electrochemical steps of redox mechanisms (ReL-ACN = fac-[Re(CO)3(5,6-epoxy-5,6-dihydro-1,10-phenanthroline)(ACN)]+); Table S1: Crystal data collection and structure refinement parameters for the ReL compound; Table S2: Bond distances (Å) and angles (°) for the ReL compound; Table S3: Intermolecular hydrogen-bonding interaction parameters for ReL compound. References [112,113] is cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and M.G.; methodology, A.C., R.M.-G., R.A., L.L.-P., C.V., M.C.O. and M.G.; software, E.A.-G.; validation, A.C. and M.G.; formal analysis, A.C., V.A., E.A.-G. and M.G.; investigation, A.C., V.A., E.A.-G., R.M.-G., R.A., L.L.-P., C.V., M.C.O. and M.G.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.C. and M.G.; writing—original draft, A.C., E.A.-G., R.M.-G., R.A., L.L.-P., A.A.M., C.V., M.C.O. and M.G.; writing—review & editing, A.C., V.A., E.A.-G., R.M.-G., A.A.M., M.C.O. and M.G.; visualization, A.A.M. and M.G.; supervision, A.A.M. and M.G.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funds were provided by ANID through grants numbers (FONDECYT) 1230917 and (FONDECYT) 1220272.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

A. Carreño thanks Fondecyt 1230917 (ANID). M. Gacitúa thanks FONDECYT 1220272 (ANID). R. Arce thanks the Millennium Institute on Green Ammonia as Energy Vector MIGA, ANID/Millennium Science Initiative Program/ICN2021_023. A Carreño acknowledges Dayán Páez-Hernández (Center of Applied Nanosciences CANS, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Universidad Andres Bello, Chile) for software facilities and Bs. Juan Manuel Ortega Martinez (Fondecyt 1230917) for editing and the English translation. We also thank Poldie Oyarzún from the Laboratorio de Análisis de Sólidos (L.A.S.), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Universidad Andrés Bello, for helping with the crystal measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Supplementary data CCDC reference number 2400807 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge at www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (accessed on 4 December 2025) [or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; Fax: (internat.) +44 1223/336 033; E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

References

- Ko, C.-C.; Cheung, A.W.-Y.; Lo, L.T.-L.; Siu, J.W.-K.; Ng, C.-O.; Yiu, S.-M. Syntheses and photophysical studies of new classes of luminescent isocyano rhenium(I) diimine complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, T.; Flores, E.; Gómez, A.; Godoy, F.; Mascayano, C.; Martí, A.A.; Ferraudi, G. Kinetic study of the azo—Hydrazone photoinduced mechanism in complexes with a -Re(CO)3L0/+ core by flash photolysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2023, 442, 114802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicum, A.-L.E.; Louis, H.; Mathias, G.E.; Agwamba, E.C.; Malan, F.P.; Unimuke, T.O.; Nzondomyo, W.J.; Sithole, S.A.; Biswas, S.; Prince, S. Single crystal investigation, spectroscopic, DFT studies, and in-silico molecular docking of the anticancer activities of acetylacetone coordinated Re(I) tricarbonyl complexes. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2023, 546, 121335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Solís-Céspedes, E.; Zúñiga, C.; Nevermann, J.; Rivera-Zaldívar, M.M.; Gacitúa, M.; Ramírez-Osorio, A.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Arratia-Pérez, R.; Fuentes, J.A. Cyclic voltammetry, relativistic DFT calculations and biological test of cytotoxicity in walled-cell models of two classical rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complexes with 5-amine-1,10-phenanthroline. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 715, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrighton, M. Photochemistry of metal carbonyls. Chem. Rev. 1974, 74, 401–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrighton, M.; Morse, D.L. Nature of the lowest excited state in tricarbonylchloro-1,10-phenanthrolinerhenium(I) and related complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilworth, J.R. Rhenium chemistry—Then and Now. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 436, 213822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merillas, B.; Cuéllar, E.; Diez-Varga, A.; Torroba, T.; García-Herbosa, G.; Fernández, S.; Lloret-Fillol, J.; Martín-Alvarez, J.M.; Miguel, D.; Villafañe, F. Luminescent Rhenium(I)tricarbonyl Complexes Containing Different Pyrazoles and Their Successive Deprotonation Products: CO2 Reduction Electrocatalysts. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 11152–11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar, E.; Pastor, L.; García-Herbosa, G.; Nganga, J.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Diez-Varga, A.; Torroba, T.; Martín-Alvarez, J.M.; Miguel, D.; Villafañe, F. (1,2-Azole)bis(bipyridyl)ruthenium(II) Complexes: Electrochemistry, Luminescent Properties, And Electro- And Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez–Arteaga, B.; Gómez, A.; Flores, E.; Vega, A.; Cruz–Piñones, B.; Godoy, F.; Maldonado, T. Revealing the Unusual behavior of rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complex functionalized with Aza-Macrocycles in response to metal ions. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2025, 574, 122389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choroba, K.; Penkala, M.; Palion-Gazda, J.; Malicka, E.; Machura, B. Pyrenyl-Substituted Imidazo[4,5-f][1,10]phenanthroline Rhenium(I) Complexes with Record-High Triplet Excited-State Lifetimes at Room Temperature: Steric Control of Photoinduced Processes in Bichromophoric Systems. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 19256–19269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanasekaran, P.; Huang, J.-H.; Jhou, C.-R.; Tsao, H.-C.; Mendiratta, S.; Su, C.-H.; Liu, C.-P.; Liu, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-H.; Lu, K.-L. A neutral mononuclear rhenium(I) complex with a rare in situ -generated triazolyl ligand for the luminescence “turn-on” detection of histidine. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diksha; Somasundaram, M.; Ganeshan, M.; Samal, S.K.; Dharumadurai, D.; Madrahimov, S.; Deshwal, A.; Kaur, H.; Sinopoli, A.; Yempally, V. Synthesis and structural elucidation of cytotoxic mono and dinuclear rhenium carbonyl complexes bearing bis-{1,3-(imino pyrrolyl)-m-chloro phenyl)} ligand. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, H.C.; Clède, S.; Guillot, R.; Lambert, F.; Policar, C. Luminescence Modulations of Rhenium Tricarbonyl Complexes Induced by Structural Variations. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 6204–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palion-Gazda, J.; Choroba, K.; Maroń, A.M.; Malicka, E.; Machura, B. Structural and Photophysical Trends in Rhenium(I) Carbonyl Complexes with 2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridines. Molecules 2024, 29, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlapa-Kula, A.; Małecka, M.; Maroń, A.M.; Janeczek, H.; Siwy, M.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; Szalkowski, M.; Maćkowski, S.; Pedzinski, T.; Erfurt, K.; et al. In-Depth Studies of Ground- and Excited-State Properties of Re(I) Carbonyl Complexes Bearing 2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine and 2,6-Bis(pyrazin-2-yl)pyridine Coupled with π-Conjugated Aryl Chromophores. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 18726–18738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alka, A.; Shetti, V.S.; Ravikanth, M. Coordination chemistry of expanded porphyrins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 401, 213063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palion-Gazda, J.; Szłapa-Kula, A.; Penkala, M.; Erfurt, K.; Machura, B. Photoinduced Processes in Rhenium(I) Terpyridine Complexes Bearing Remote Amine Groups: New Insights from Transient Absorption Spectroscopy. Molecules 2022, 27, 7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, K.; Horner, J.; Demirci, G.; Cortat, Y.; Crochet, A.; Mamula Steiner, O.; Zobi, F. In Vitro Biological Activity of α-Diimine Rhenium Dicarbonyl Complexes and Their Reactivity with Different Functional Groups. Inorganics 2023, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp-Greenwood, F.L. An Introduction to Organometallic Complexes in Fluorescence Cell Imaging: Current Applications and Future Prospects. Organometallics 2012, 31, 5686–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsche, D.; Lima, M.A.L.; Meitinger, N.; Prasad, K.; Mandal, S.; Glusac, K.D.; Rau, S.; Pannwitz, A. Shifting the MLCT of d6 metal complexes to the red and NIR. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 530, 216454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diksha; Kaur, M.; Megha; Reenu; Kaur, H.; Yempally, V. Rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complex with thiosemicarbazone ligand derived from Indole-2-carboxaldehyde: Synthesis, crystal structure, computational investigations, antimicrobial activity, and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1301, 137319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, M.; Green, O. Rhenium tricarbonyl chloro of di-2-pyridylketone 4-aminobenzoyl hydrazone (dpk4abh), fac-[Re(CO)3(κ2-N,N-dpk4abh)Cl]: Synthesis, spectroscopic and electrochemical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 996, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, O.S. Proton-coupled electron transfer with photoexcited ruthenium(II), rhenium(I), and iridium(III) complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 282–283, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.L.; Marker, S.C.; Lambert, V.J.; Woods, J.J.; MacMillan, S.N.; Wilson, J.J. Synthesis, characterization, and biological properties of rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes bearing nitrogen-donor ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 907, 121064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, C.; Carreño, A.; Polanco, R.; Llancalahuen, F.M.; Arratia-Pérez, R.; Gacitúa, M.; Fuentes, J.A. Rhenium (I) Complexes as Probes for Prokaryotic and Fungal Cells by Fluorescence Microscopy: Do Ligands Matter? Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 461605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capulín Flores, L.; Paul, L.A.; Siewert, I.; Havenith, R.; Zúñiga-Villarreal, N.; Otten, E. Neutral Formazan Ligands Bound to the fac-(CO)3 Re(I) Fragment: Structural, Spectroscopic, and Computational Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 13532–13542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manav, N.; Janaagal, A.; Gupta, I. Unveiling new horizons: Exploring rhenium and iridium dipyrrinato complexes as luminescent theranostic agents for phototherapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 511, 215798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enslin, L.E.; Purkait, K.; Pozza, M.D.; Saubamea, B.; Mesdom, P.; Visser, H.G.; Gasser, G.; Schutte-Smith, M. Rhenium(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes of 1,10-Phenanthroline Derivatives with Unexpectedly High Cytotoxicity. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 12237–12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, H.S.; Mai, C.-W.; Zulkefeli, M.; Madheswaran, T.; Kiew, L.V.; Delsuc, N.; Low, M.L. Recent Emergence of Rhenium(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes as Photosensitisers for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, L.; Grills, D.C.; Gobetto, R.; Priola, E.; Nervi, C.; Polyansky, D.E.; Fujita, E. Photochemical CO2 Reduction Using Rhenium(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes with Bipyridyl-Type Ligands with and without Second Coordination Sphere Effects. ChemPhotoChem 2021, 5, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cheng, S.-C.; Ko, C.-C. Luminescent rhenium(I) complex with cyanopentafluorophosphate ligand: Synthesis, characterization, and photophysics. J. Organomet. Chem. 2023, 1001, 122882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Zúñiga, C.; Ramírez-Osorio, A.; Pizarro, N.; Vega, A.; Solis-Céspedes, E.; Rivera-Zaldívar, M.M.; Silva, A.; Fuentes, J.A. Exploring rhenium (I) complexes as potential fluorophores for walled-cells (yeasts and bacteria): Photophysics, biocompatibility, and confocal microscopy. Dye. Pigment. 2021, 184, 108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, P.P.; Bieger, K.; Cuchillo, A.; Tello, A.; Muena, J.P. Theoretical determination of a reaction intermediate: Fukui function analysis, dual reactivity descriptor and activation energy. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1227, 129369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, T.; Laplaza, R.; Peccati, F.; Fuster, F.; Contreras-García, J. The NCIWEB Server: A Novel Implementation of the Noncovalent Interactions Index for Biomolecular Systems. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 4483–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Solis-Céspedes, E.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Arratia-Pérez, R. Exploring the geometrical and optical properties of neutral rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complex of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-diol using relativistic methods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 685, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nahhas, A.; Consani, C.; Blanco-Rodrίguez, A.M.a.; Lancaster, K.M.; Braem, O.; Cannizzo, A.; Towrie, M.; Clark, I.P.; Zális, S.; Chergui, M.; et al. Ultrafast Excited-State Dynamics of Rhenium(I) Photosensitizers [Re(Cl)(CO)3(N,N)] and [Re(imidazole)(CO)3(N,N)]+: Diimine Effects. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 2932–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martí, A.A.; Mezei, G.; Maldonado, L.; Paralitici, G.; Raptis, R.G.; Colón, J.L. Structural and Photophysical Characterisation of fac-Tricarbonyl(chloro)(5,6-epoxy-1,10-phenanthroline)rhenium(I)]. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2005, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, L.; Brandon, M.P.; Coleman, A.; Chippindale, A.M.; Hartl, F.; Lalrempuia, R.; Pižl, M.; Pryce, M.T. Ligand-Structure Effects on N-Heterocyclic Carbene Rhenium Photo- and Electrocatalysts of CO2 Reduction. Molecules 2023, 28, 4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, F.; Demirpolat, A.; Kazachenko, A.S.; Kazachenko, A.S.; Issaoui, N.; Al-Dossary, O. Molecular Structure, Electronic Properties, Reactivity (ELF, LOL, and Fukui), and NCI-RDG Studies of the Binary Mixture of Water and Essential Oil of Phlomis bruguieri. Molecules 2023, 28, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultinck, P.; Clarisse, D.; Ayers, P.W.; Carbo-Dorca, R. The Fukui matrix: A simple approach to the analysis of the Fukui function and its positive character. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultinck, P.; Van Neck, D.; Acke, G.; Ayers, P.W. Influence of electron correlation and degeneracy on the Fukui matrix and extension of frontier molecular orbital theory to correlated quantum chemical methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, K.; Ramaswamy, M.; Kolandaivel, P. Studies of chemical hardness and Fukui function using the exact solution of the density functional theory. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2001, 81, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, L.; Kolandaivel, P. Study of effective hardness and condensed Fukui functions using AIM, ab initio, and DFT methods. Mol. Phys. 2005, 103, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, T.S.; Raja, K.; Mandapati, K.R.; Goli, S.R.; Babu, M.S.S. Efficient Approach for the Synthesis of Aryl Vinyl Ketones and Its Synthetic Application to Mimosifoliol with DFT and Autodocking Studies. Molecules 2023, 28, 6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G.P.; Das, D.; Sheet, P.S.; Beg, H.; Salgado-Morán, G.; Misra, A. Morphology directing synthesis of 1-pyrene carboxaldehyde microstructures and their photo physical properties. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaton, Y.; Djukic, J.-P. Noncovalent Interactions in Organometallic Chemistry: From Cohesion to Reactivity, a New Chapter. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3828–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukin, G.K.; Cherkasov, A.V.; Zarovkina, N.Y.; Artemov, A.N. Experimental and Theoretical AIM and NCI Index Study of Substituted Arene Tricarbonyl Complexes of Chromium(0). ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 5014–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solà, M.; Ottosson, H.; Baranac, M.; Stojanovi’c, S.c. Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: How to Define Them. Chemistry 2025, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacanamboy, D.S.; García-Argote, W.; Pumachagua-Huertas, R.; Cárdenas, C.; Leyva-Parra, L.; Ruiz, L.; Tiznado, W. Interpreting Ring Currents from Hückel-Guided σ- and π-Electron Delocalization in Small Boron Rings. Molecules 2025, 30, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Dawson, G.; Diao, T. Experimental Electrochemical Potentials of Nickel Complexes. Synlett 2021, 32, 1606–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitinger, N.; Mandal, S.; Sorsche, D.; Pannwitz, A.; Rau, S. Red Light Absorption of [ReI(CO)3(α-diimine)Cl] Complexes through Extension of the 4,4′-Bipyrimidine Ligand’s π-System. Molecules 2023, 28, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño, A.; Gacitua, M.; Schott, E.; Zarate, X.; Manriquez, J.M.; Preite, M.; Ladeira, S.; Castel, A.; Pizarro, N.; Vega, A.; et al. Experimental and theoretical studies of the ancillary ligand (E)-2-((3-amino-pyridin-4-ylimino)-methyl)-4,6-di-tert-butylphenol in the rhenium(I) core. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 5725–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.-H.; Pan, M.-Y.; He, Q.; Tang, Q.; Chow, C.-F.; Gong, C.-B. Electrochromic behavior of fac-tricarbonyl rhenium complexes. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, L.; Polyansky, D.E.; Gobetto, R.; Grills, D.C.; Fujita, E.; Nervi, C.; Manbeck, G.F. Molecular Catalysts with Intramolecular Re–O Bond for Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 12187–12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.-T.; Zhu, N.; Au, V.K.-M.; Yam, V.W.-W. Synthesis, characterization, electrochemistry and photophysical studies of rhenium(I) tricarbonyl diimine complexes with carboxaldehyde alkynyl ligands. Polyhedron 2015, 86, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Gacitúa, M.; Fuentes, J.A.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Peñaloza, J.P.; Otero, C.; Preite, M.; Molins, E.; Swords, W.B.; Meyer, G.J.; et al. Fluorescence probes for prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells using Re(CO)3+ complexes with an electron withdrawing ancillary ligand. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 7687–7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Gacitúa, M.; Molins, E.; Arratia-Pérez, R. X-ray diffraction and relativistic DFT studies on the molecular biomarker fac-Re(CO)3(4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bpy)(E-2-((3-amino-pyridin-4-ylimino)-methyl)-4,6-di-tert-butylphenol)(PF6). Chem. Pap. 2017, 71, 2011–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwieniec, R.; Kapturkiewicz, A.; Lipkowski, J.; Nowacki, J. Re(I)(tricarbonyl)+ complexes with the 2-(2-pyridyl)-N-methyl-benzimidazole, 2-(2-pyridyl)benzoxazole and 2-(2-pyridyl)benzothiazole ligands—Syntheses, structures, electrochemical and spectroscopic studies. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2005, 358, 2701–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]