Abstract

In this study, titanium alloy-based composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene (Gr) were fabricated via spark plasma sintering (SPS). The effects of CNT and Gr reinforcements on the microstructure, density, hardness, and tribological properties of the composites were systematically investigated. The results revealed that CNTs and Gr were dispersed within the Ti alloy matrix. All composites exhibited high relative densities about 99%, confirming the strong densification capability of the SPS process. The incorporation of CNTs and Gr significantly enhanced the mechanical performance of the composites. The maximum hardness values of 445.8 HV and 430.5 HV were obtained for CNT/Ti and Gr/Ti composites containing 3 vol.% reinforcement, corresponding to improvements of 34% and 30%, respectively, compared with the unreinforced Ti alloy. Tribological tests further revealed notable reductions in the coefficient of friction and wear rate for both CNT/Ti and Gr/Ti composites. These enhancements are attributed to the formation of a lubricating tribo-film composed of carbonaceous species and oxide particles (TiO2, Al2O3) on the worn surfaces. Among the two reinforcements, the obtained results indicated that CNTs are more effective in enhancing hardness, whereas graphene provides superior improvement in wear resistance of Ti alloy-based composites. Overall, this work demonstrated that the combination of Ti alloys with nanocarbon reinforcements is an effective approach to simultaneously enhance their mechanical and tribological performance.

1. Introduction

Metal matrix composites (MMCs), consisting of a metallic matrix reinforced with ceramic particles or fibers, exhibit high strength-to-weight ratios and excellent wear resistance [1,2]. Ceramic matrix composites (CMCs), which are based on a ceramic matrix reinforced with fibers, are characterized by outstanding thermal stability and corrosion resistance [3,4]. Meanwhile, polymer matrix composites (PMCs), composed of a polymer matrix reinforced with materials such as glass or carbon fibers, are widely recognized for their lightweight nature and high versatility [5]. The selection of reinforcement and matrix materials significantly influences the mechanical and thermal properties of composites, allowing for the design of materials tailored to meet specific application requirements. Continuous research efforts have been devoted to further enhancing their performance and sustainability across a wide range of engineering fields. Among these three fundamental types of composites, MMCs have received particular attention from researchers due to their superior overall performance compared to other composite systems [6,7]. Among the metals commonly used as matrices, aluminum (Al), magnesium (Mg), copper (Cu), titanium (Ti), and iron (Fe) are the most frequently utilized. Titanium is one of the most abundant metals in the Earth’s crust; however, it is usually found in impure forms, making its extraction and purification both costly and challenging. With a density of 4.51 g/cm3, titanium is the heaviest among the light metals. Depending on temperature, titanium and its alloys can exist in two distinct crystalline structures: a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure known as α-titanium at low temperatures, and a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure known as β-titanium at higher temperatures. Due to these unique structural characteristics, titanium alloys have been extensively employed in various industrial applications [8]. Nevertheless, their relatively low hardness, wear resistance, and strength restrict their use in certain demanding environments. In titanium metal matrix composites (TMMCs), titanium serves as the primary matrix, while reinforcements such as silicon carbide (SiC), boron carbide (B4C), aluminum oxide (Al2O3), and others are incorporated, typically in the form of fibers, whiskers, or more commonly, particles [9,10,11]. The performance of composites depends on several factors, including the type of reinforcement (particles or whiskers), the uniformity of reinforcement distribution within the matrix, and the relative volume fractions of both components. To further enhance the performance of titanium alloys, researchers have explored the addition of suitable reinforcements to develop titanium matrix composites (TMCs) with improved overall properties.

In recent years, a number of studies have reported the fabrication of TMMCs reinforced with carbon-based nanomaterials such as graphene (Gr) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [10,12,13,14,15]. CNTs and graphene are typical carbon nanomaterials that possess exceptional mechanical characteristics, including high elastic modulus, superior strength, and low density, due to the sp2 hybridization between carbon atoms [16]. When incorporated as reinforcements in titanium matrix composites using appropriate fabrication techniques, CNTs and graphene can significantly enhance the elastic modulus, compressive strength, tribological behavior, and wear resistance of the alloys [17]. Consequently, these nanomaterials are considered ideal reinforcements for various metal matrices such as Mg, Al, and Ti. Previous studies have demonstrated that the incorporation of carbon nanomaterials into metal matrix composites can markedly improve their mechanical and electrochemical properties [17,18,19,20]. The full utilization of the reinforcing potential of these nanomaterials, however, depends critically on two key factors including the homogeneous dispersion of the reinforcements and the formation of strong interfacial bonding between the reinforcement and the metal matrix. Recent investigations on Ti and Ti-based composites have primarily focused on the dispersion behavior of CNTs and Gr within the metallic matrix and their influence on the resulting composite properties [21,22,23,24]. However, comparative studies that systematically evaluate the effects of CNTs and graphene reinforcements on the microstructure and properties of titanium matrix composites remain limited. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation comparing the influence of these two nanocarbon reinforcements on the microstructural and mechanical characteristics of Ti-based composites is of significant scientific and practical interest.

In this study, titanium alloy matrix composites reinforced with CNTs and graphene were fabricated using the spark plasma sintering (SPS) method. The roles and effects of both types of reinforcements on the microstructure, hardness, and wear behavior of the composites were systematically investigated and discussed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Microstructure

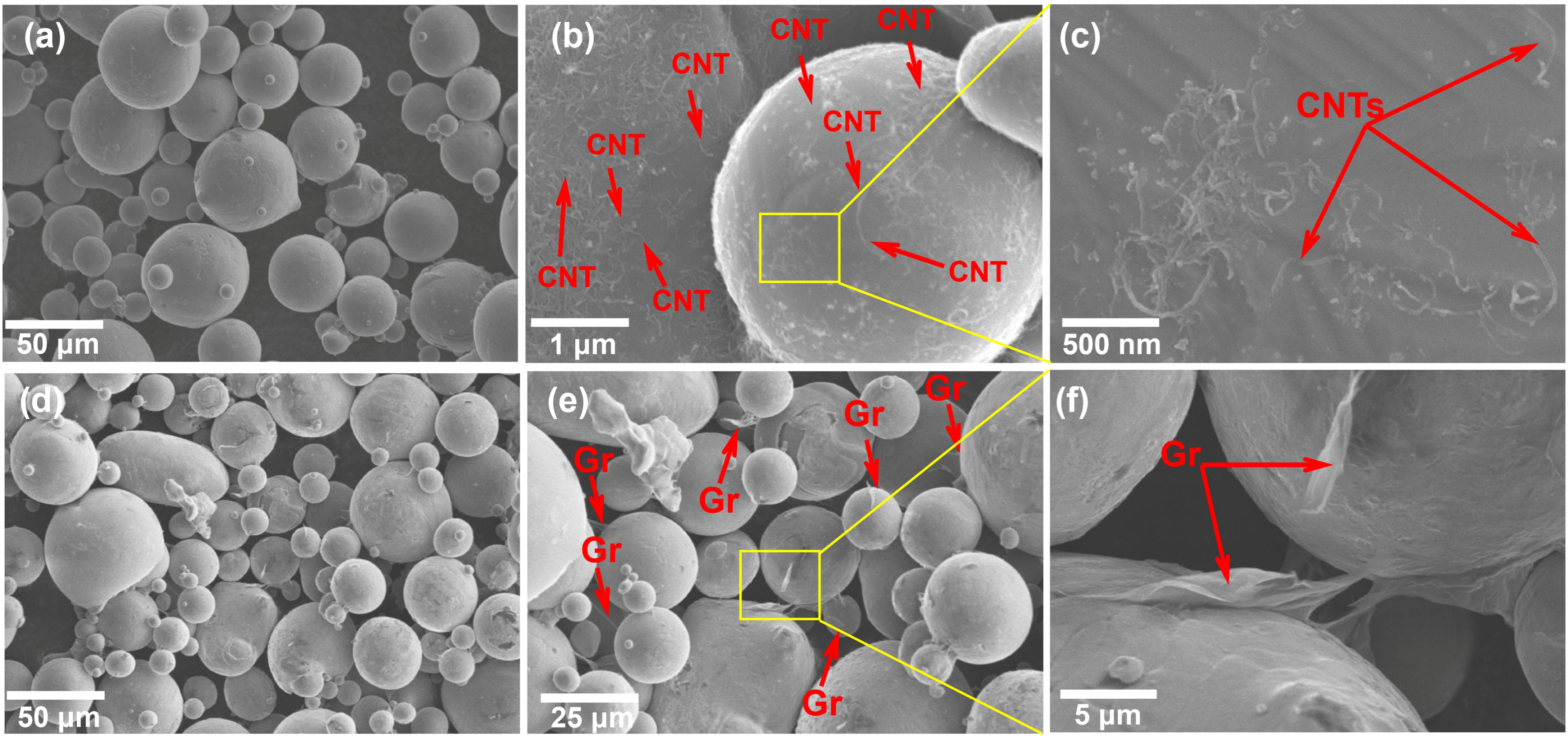

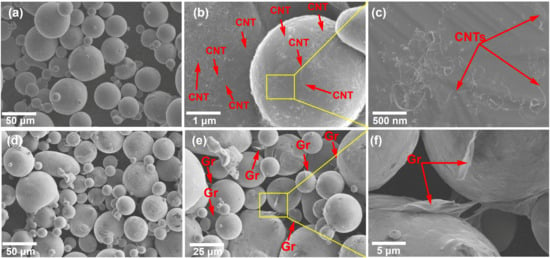

The dispersion of CNTs and Gr within the composite powders was investigated using SEM, and the results are presented in Figure 1. From the overall morphological perspective, it can be observed that the size and morphology of the Ti alloy particles did not show significant changes compared to the original Ti alloy powder. This indicates that the ultrasonic agitation process did not induce secondary deformation in the Ti alloy particles. The dispersion of CNTs is illustrated in Figure 1a–c at different magnifications. As observed, the surfaces of the Ti alloy particles are coated with CNTs, and no significant agglomeration of CNTs was observed, suggesting that ultrasonic agitation provides relatively uniform dispersion of CNTs. Similarly, the distribution of Gr within the composite powders is shown in Figure 1d–f. The obtained results reveal that Gr attached to the surfaces of Ti alloy particles. These observations demonstrate that the combination of ultrasonic agitation and vacuum filtration allows for uniform dispersion of both CNTs and Gr within the Ti alloy powder. This result is consistent with previous studies that employed ultrasonic agitation to disperse CNTs and Gr in metallic powders such as Al and Cu [25,26].

Figure 1.

SEM images with different magnification of (a–c) Ti alloy-CNT powder with 3 vol.% CNTs and (d–f) Ti alloy-Gr powder with 3 vol.% Gr.

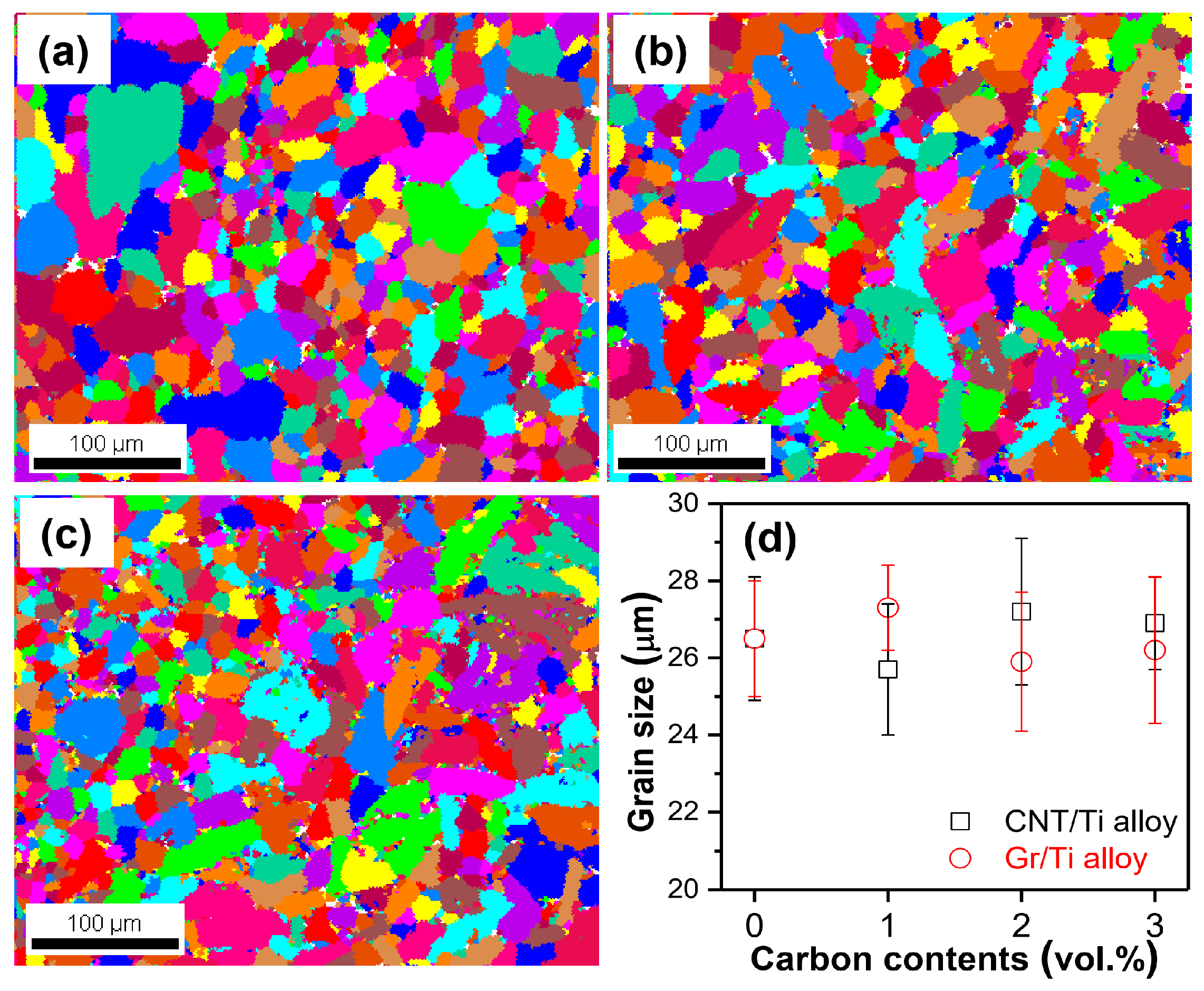

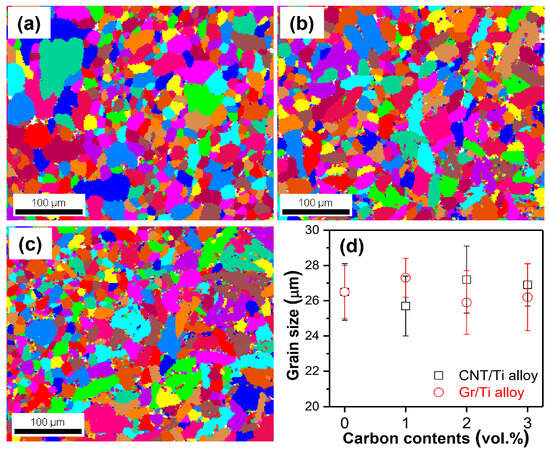

The microstructure of the composites after sintering was examined to evaluate changes in grain size and the presence of CNTs and Gr. Grain size was measured using EBSD technique, as shown in Figure 2. The results indicated that the average grain size of the Ti alloy sample was approximately 26.5 μm. For the CNT/Ti alloy composites, the average grain sizes were determined to be 25.1 μm, 27.1 μm, and 26.9 μm for samples containing 1%, 2%, and 3 vol.% CNTs, respectively. For the Gr/Ti alloy composites, the average grain sizes were 27.2 μm, 25.7 μm, and 26.3 μm for samples containing 1%, 2%, and 3 vol.% Gr, respectively. These observations suggested that the composites containing CNTs and Gr exhibit a non-linear variation in grain size with increasing reinforcement material content (Figure 2d). In other words, the addition of CNTs and Gr does not significantly influence the grain size of the composites after consolidated by using SPS technique. The role of CNTs and Gr in affecting grain growth in metal matrix composites has been previously investigated and discussed by several research groups [27,28,29]. The present results further confirm that CNTs and Gr inhibited the grain growth during the sintering process [30,31,32].

Figure 2.

Grain size distribution of (a) sintered Ti alloy (b) CNT/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% CNT, (c) Gr/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% Gr and (d) comparison the grain size of the prepared samples.

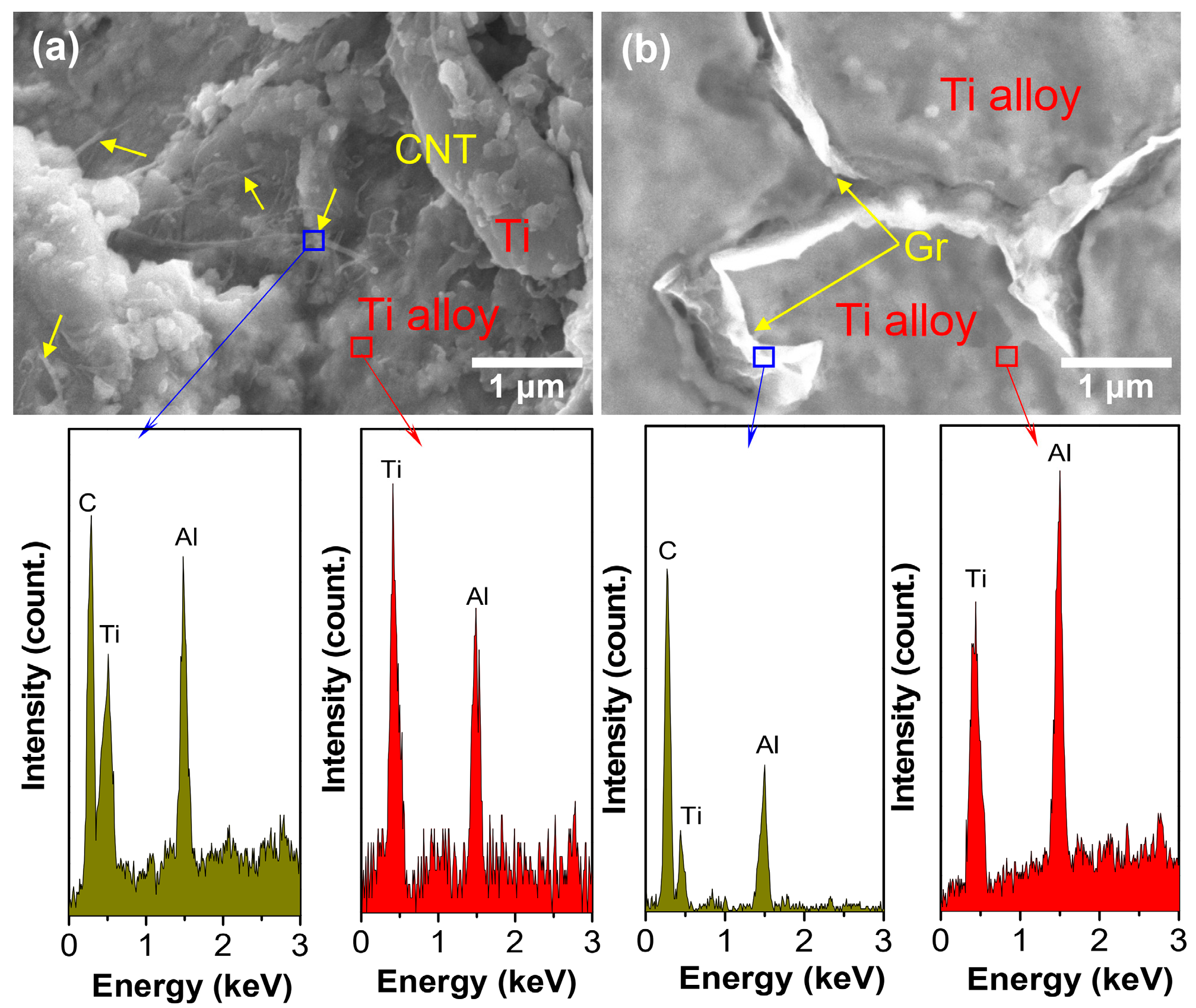

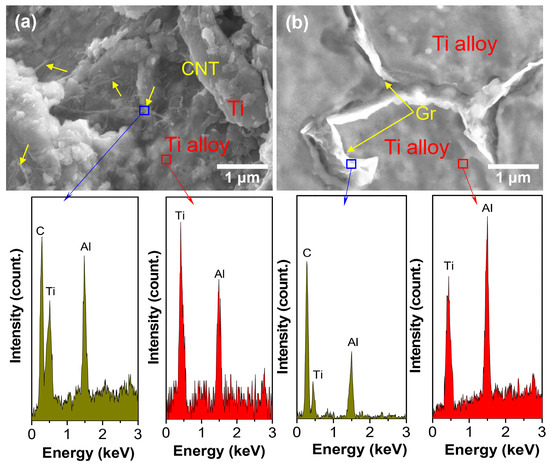

The presence of CNTs and Gr in the composites was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Prior to observation, the composites were polished and then etched in 48% H2SO4 solution for 30 min. Grain boundary regions were preferentially etched, revealing the presence of reinforcing materials such as CNTs and Gr at the boundaries. As shown in Figure 3a, individual CNTs can be observed at the grain boundaries, indicating that CNTs were not completely destroyed during sintering. EDS point spectra also confirm that presence of C element at the certain point Similarly, Gr/Ti alloy composites also exhibited graphene sheets at the etched regions (Figure 3b). EDS spectrum of composites at separate points was investigated. The results obtained also showed the existence of C element at the investigated positions. These results demonstrate that CNTs and Gr remain present after the sintering process.

Figure 3.

SEM images and EDS spectra of etched composites (a) CNT/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% CNTs and (b) Gr/Ti alloy composites containing 3 vol.% Gr.

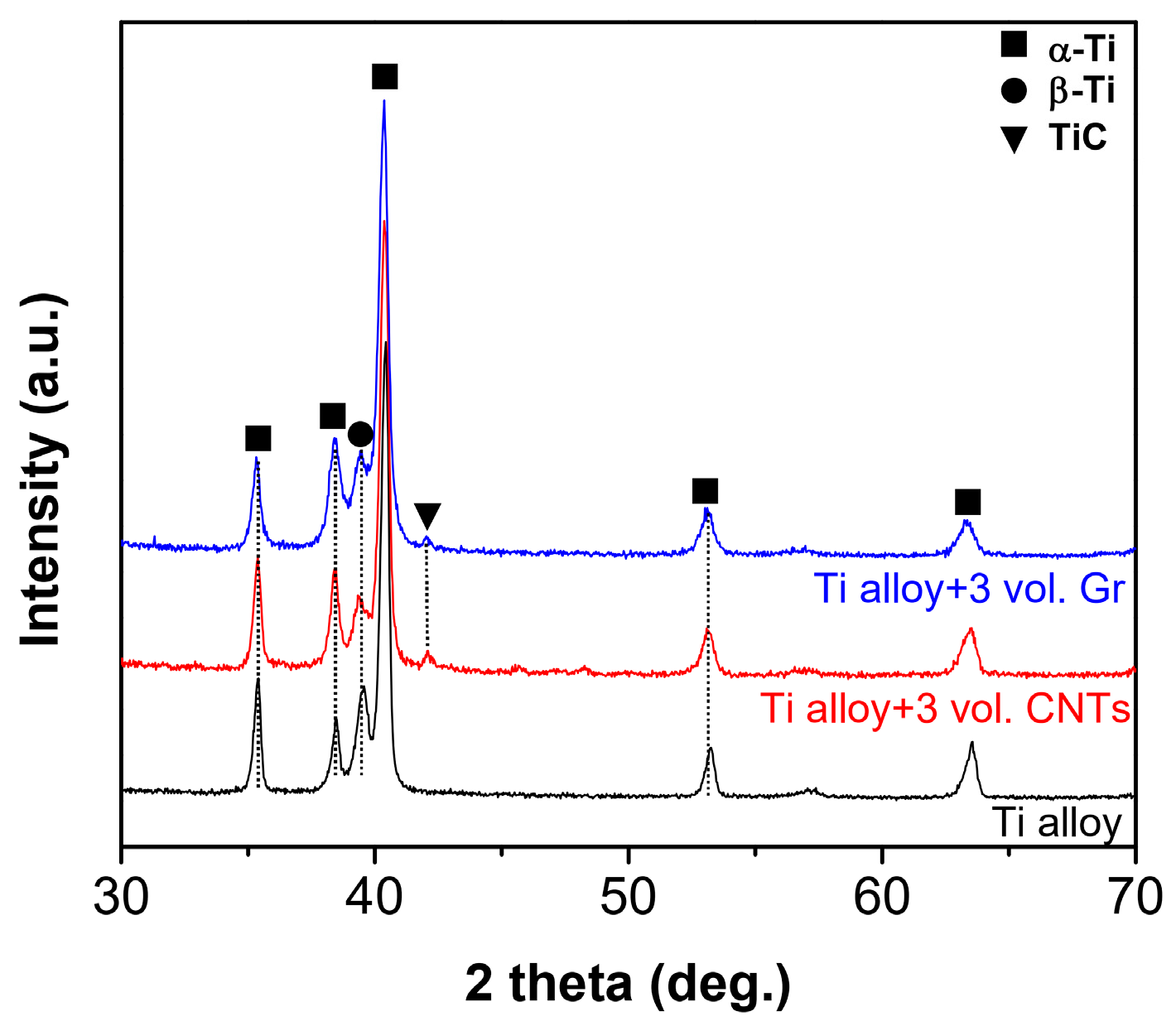

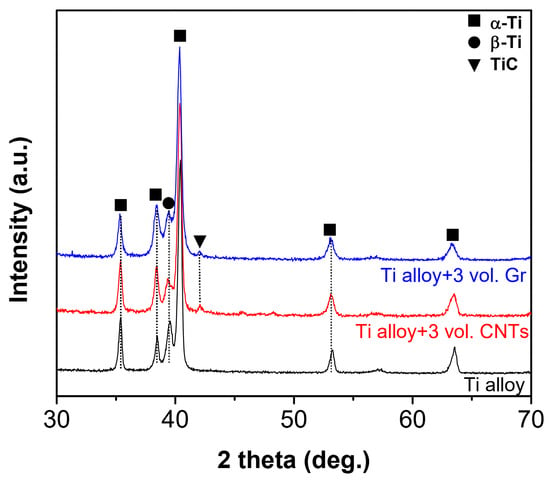

Figure 4 presents the XRD patterns of the prepared samples. All samples exhibit the characteristic diffraction peaks of the α-Ti and β-Ti phases. In the composite samples, besides these typical peaks, an additional peak appears at 2θ ≈ 42° corresponding to (200) reflection reflections of the TiC (JCPDS 65-7994). This observation provides clear evidence for the formation of TiC in the composite. The potential reaction at the interface between CNTs or Gr and the Ti matrix, leading to the formation of interphases such as TiC as reported in the previous studies [33,34,35].

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of Ti alloy, CNT/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% CNTs and Gr/Ti alloy composites containing 3 vol.% Gr.

2.2. Density and Hardness

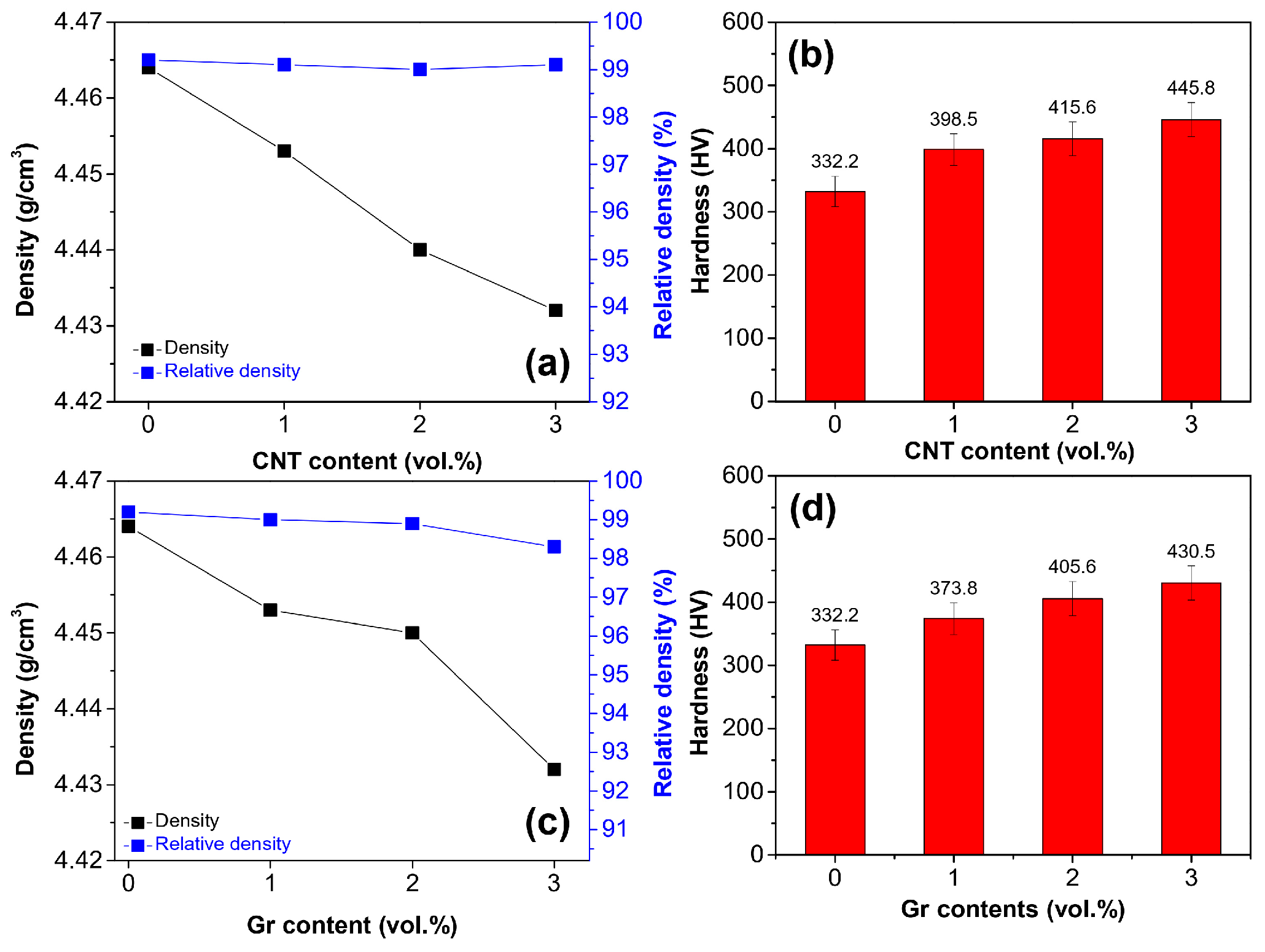

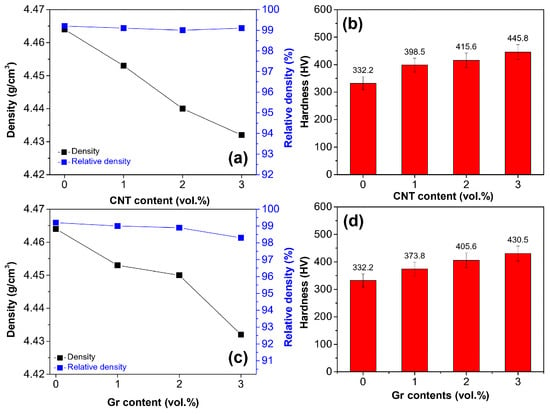

The density and relative density were measured to evaluate the influence of CNTs and Gr on the densification behavior of the composites. The effect of reinforcement content on the density and relative density of the materials is presented in Figure 5a–c. For the sintered Ti alloy sample, the measured density was approximately 4.463 g/cm3, corresponding to a relative density of about 99.2% compared to the theoretical density of the Ti alloy. For the CNT/Ti alloy composites, the measured density decreased with increasing CNT content. This trend is expected, as CNTs possess a much lower density (~1.8 g/cm3) compared to Ti alloy. Consequently, increasing the CNT content leads to a reduction in the overall composite density. However, it is noteworthy that the relative density of all CNT/Ti alloy composites remained above 99%, indicating that the SPS technique enabled near-theoretical densification of the composites with minimal residual porosity (Figure 5a). Similarly, in the case of the Gr/Ti alloy composites, the density also decreased with increasing Gr content due to the lower intrinsic density of Gr compared to Ti alloy. Interestingly, when comparing the CNT/Ti alloy and Gr/Ti alloy composites, the relative density of the Gr/Ti alloy composites was slightly lower than that of the CNT/Ti alloy composites at higher reinforcement levels (up to 3 vol.%) (Figure 5c). This slight reduction can be attributed to the tendency of graphene sheets to restack via π–π stacking interactions, which can lead to the formation of local Gr agglomerates within the composite [36,37]. Such agglomeration may impede the densification process during sintering. Nevertheless, overall results demonstrate that the SPS technique is highly effective for fabricating dense composites, as evidenced by the relatively high relative densities achieved in both CNT- and Gr-reinforced Ti alloy systems.

Figure 5.

Effect of carbon contents on the relative density and hardness of (a,b) CNT/Ti alloy composite and (c,d) Gr/Ti alloy composites.

The effect of reinforcement content on the hardness of the composites is presented in Figure 5b,d. The results indicate that the hardness of the composites increases with increasing amounts of reinforcing materials such as CNTs and Gr. For the CNT/Ti alloy composites, the highest hardness value of 445.8 HV was obtained for the sample containing 3 vol.% CNTs, representing an improvement of approximately 34% compared with the unreinforced Ti alloy (Figure 5b). Similarly, the Gr/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% Gr exhibited a maximum hardness of 430.5 HV, which is about 30% higher than that of the Ti alloy Figure 5d. These results demonstrate that both CNTs and Gr have a positive effect on enhancing the hardness of Ti-based composites. This observation is consistent with previous studies in which CNTs and Gr have been used as reinforcement phases in metal matrix composites. In addition to their inherently high mechanical strength and stiffness, the improvement in hardness may also be attributed to the formation of TiC phases as indicated in XRD patterns. The formation of these interfacial compounds can significantly strengthen the bonding between the reinforcement and the matrix, thereby improving the overall mechanical properties of the composites [38]. Notably, when comparing CNT and Gr reinforcements, the CNT-reinforced composites exhibited slightly higher hardness values than those reinforced with Gr. This difference may be associated with the more efficient densification of CNT-containing composites, as discussed in the previous section.

2.3. Wear Property

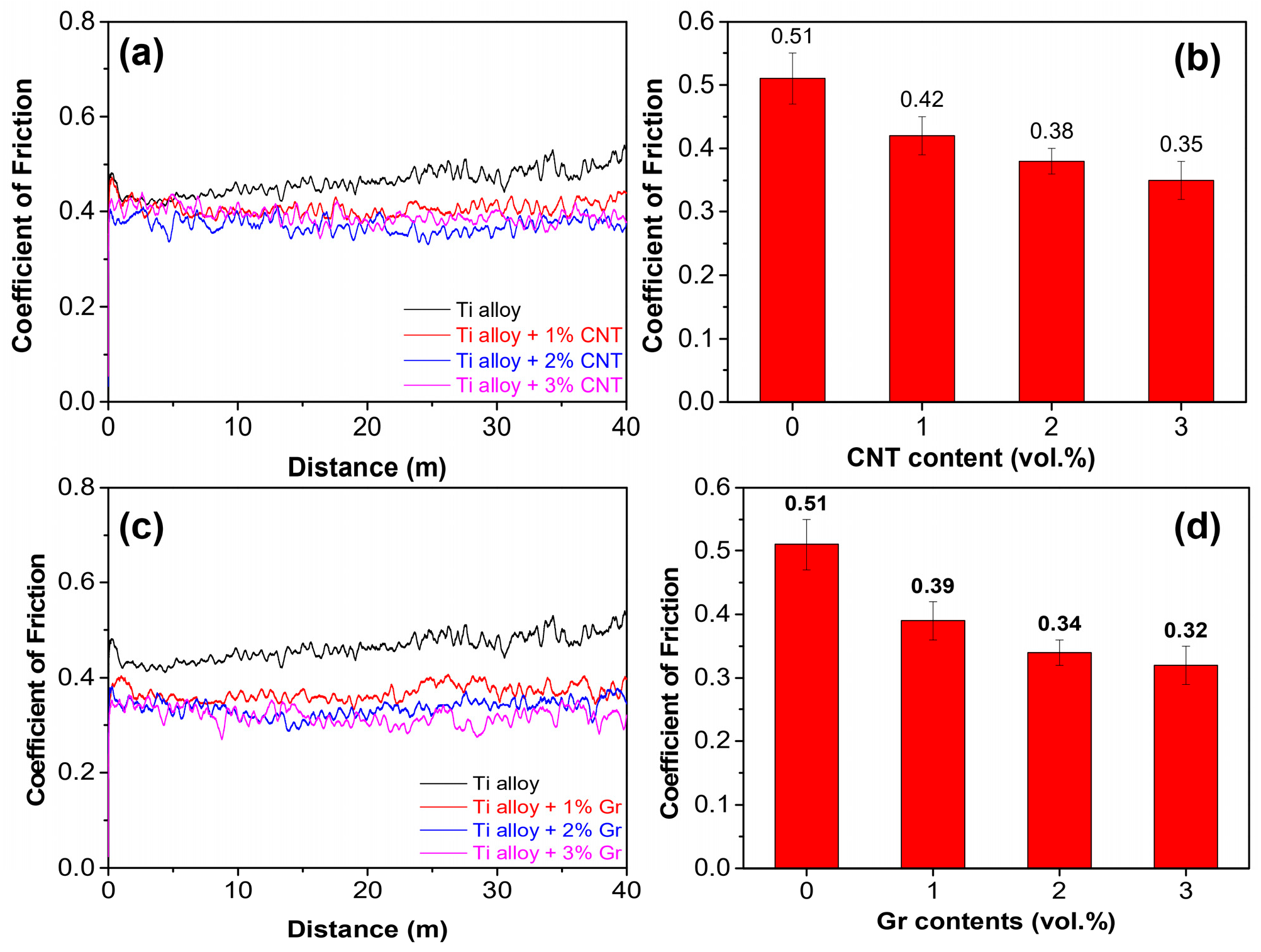

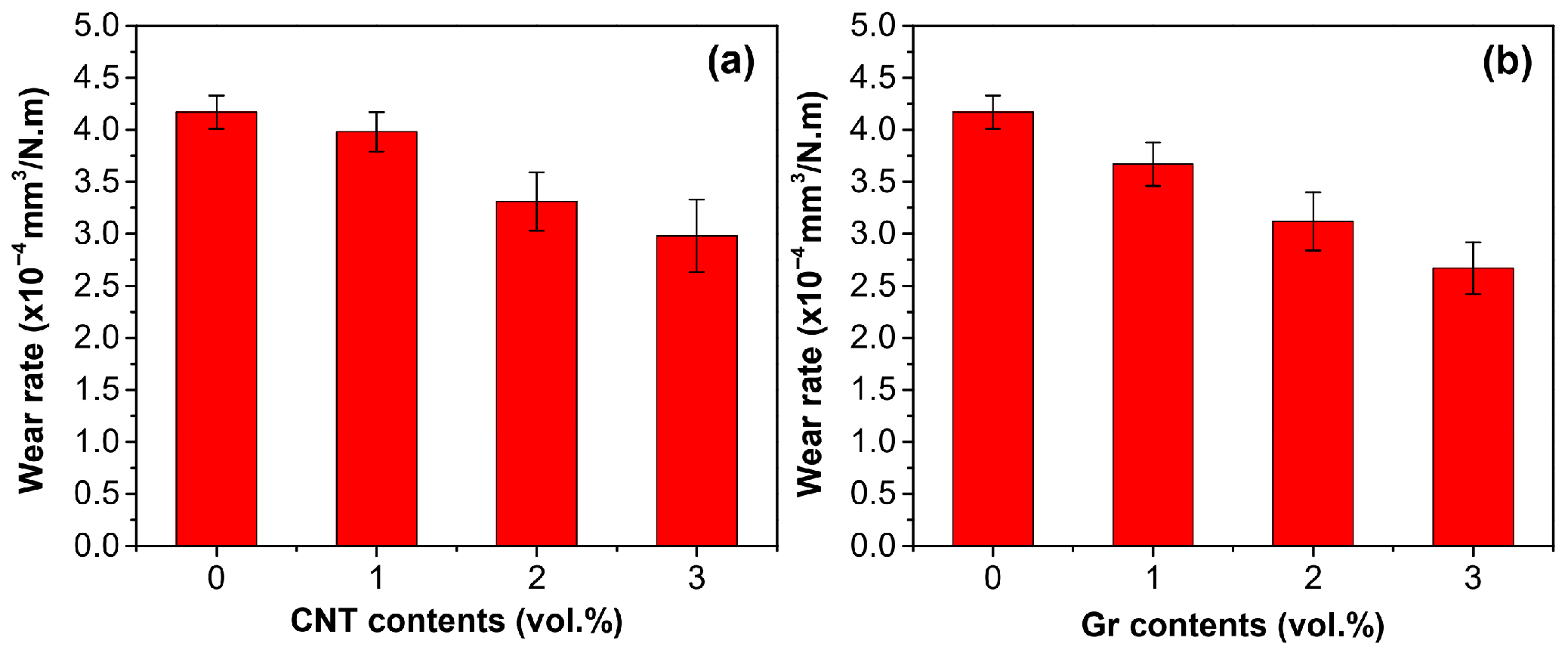

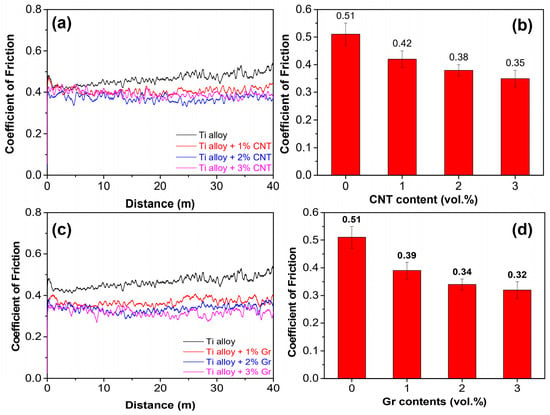

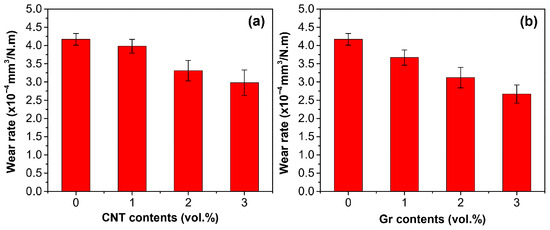

The effect of CNT and Gr reinforcement content on the coefficient of friction (COF) of the composites is illustrated in Figure 6. The results show that the COF of the composites decreases with increasing reinforcement content. For the unreinforced Ti alloy, the COF was determined to be approximately 0.51. This value decreased when the alloy was reinforced with CNTs or Gr. In the case of the CNT/Ti alloy composite, the lowest COF of 0.35 was obtained for the sample containing 3 vol.% CNTs, representing a 35% reduction compared with the Ti alloy. Similarly, the Gr/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% Gr exhibited a COF that was 37% lower than that of the Ti alloy and about 8% lower than that of the CNT/Ti alloy composite with the same reinforcement content. Figure 7 shows the wear rates of the prepared composites. The obtained results indicate that the wear rate decreases with increasing carbon content. It is interesting noted that the composites reinforced with Gr exhibit consistently lower wear rates compared with those reinforced with CNTs. This trend is fully consistent with the measured friction coefficient results. These findings indicate that both CNTs and Gr play a significant role in reducing the friction coefficient of Ti alloy composites. The improvement in tribological performance can be attributed to the inherent lubricating properties of CNTs and Gr, which facilitate the formation of a stable tribofilm at the contact surface during sliding, thereby minimizing direct metal-to-metal contact and reducing frictional resistance.

Figure 6.

Effect of carbon contents on the COF curves and the average COF of (a,b) CNT/Ti alloy composite and (c,d) Gr/Ti alloy composites.

Figure 7.

Effect of carbon contents on the wear rate of (a) CNT/Ti alloy composite and (b) Gr/Ti alloy composites.

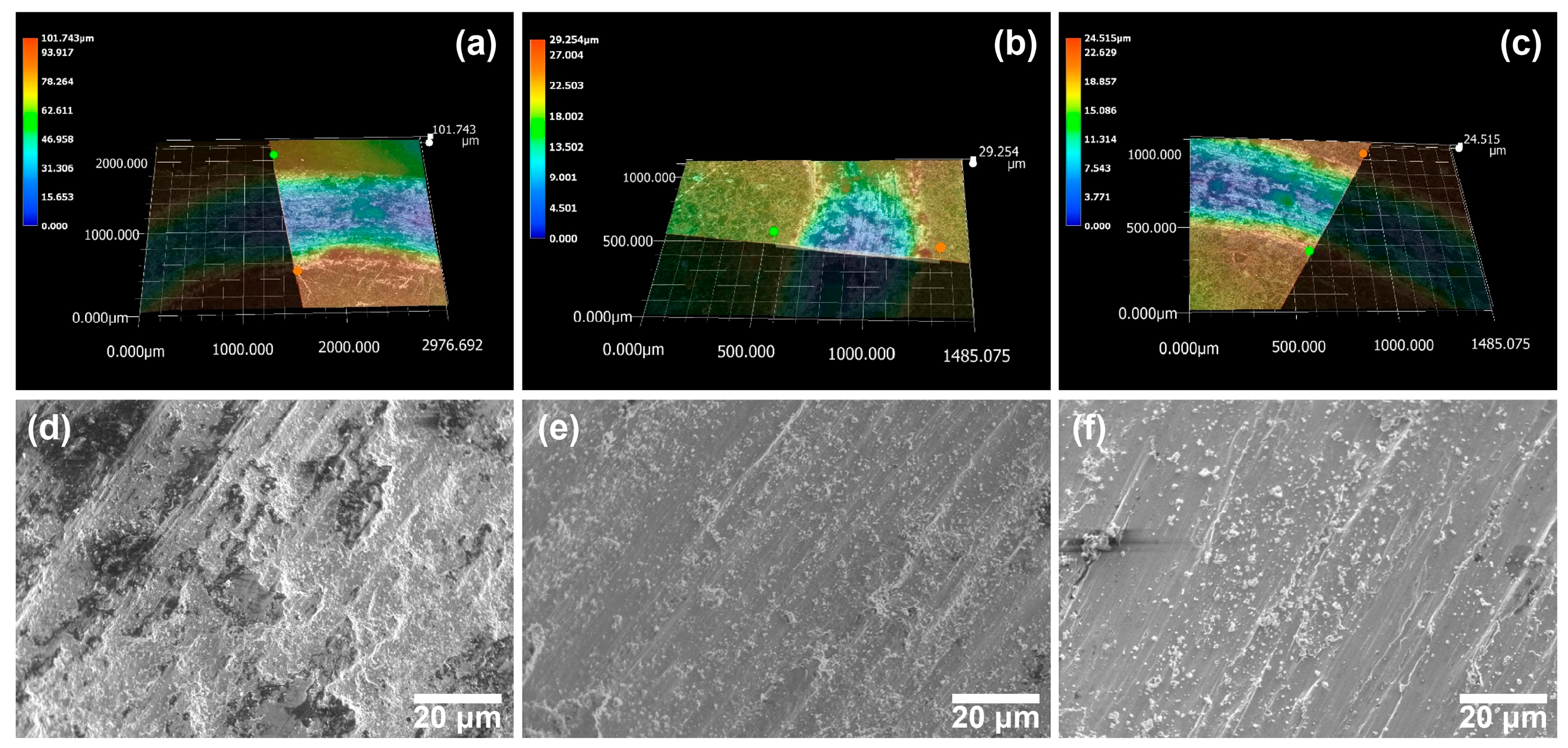

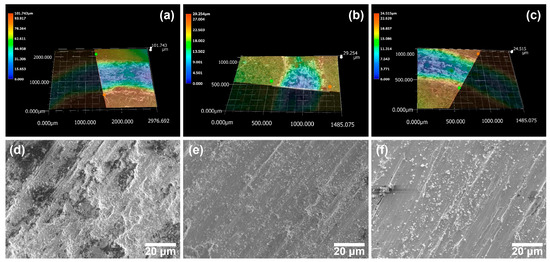

Figure 8a–c shows the surface morphology of the wear tracks for the Ti alloy, CNT/Ti alloy composite, and Gr/Ti alloy composite after the friction tests. As observed, the wear track of the Ti alloy exhibits a significantly greater width and depth compared to those of the composites. This observation indicates that the material loss during the wear test was substantially higher for the Ti alloy than for the composite samples. To further elucidate the wear mechanisms, the worn surfaces of the Ti alloy and composite samples were examined by SEM (Figure 8d–f). As shown in Figure 8d, the worn surface of the Ti alloy is relatively rough, characterized by numerous pits and small detached particles. This morphology is consistent with the high friction coefficient measured earlier. In contrast, the worn surfaces of the CNT/Ti alloy and Gr/Ti alloy composites appear much smoother, with finer debris distributed across the surface and without the presence of pits or delamination features observed in the Ti alloy (Figure 8e,f). These morphological observations are in good agreement with the COF results discussed above, confirming that the incorporation of CNTs and Gr effectively reduces friction in Ti alloy composites.

Figure 8.

Optical and SEM images of wear tracks of (a,d) sintered Ti alloy, (b,e) CNT/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% CNTs and (c,f) Gr/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% Gr.

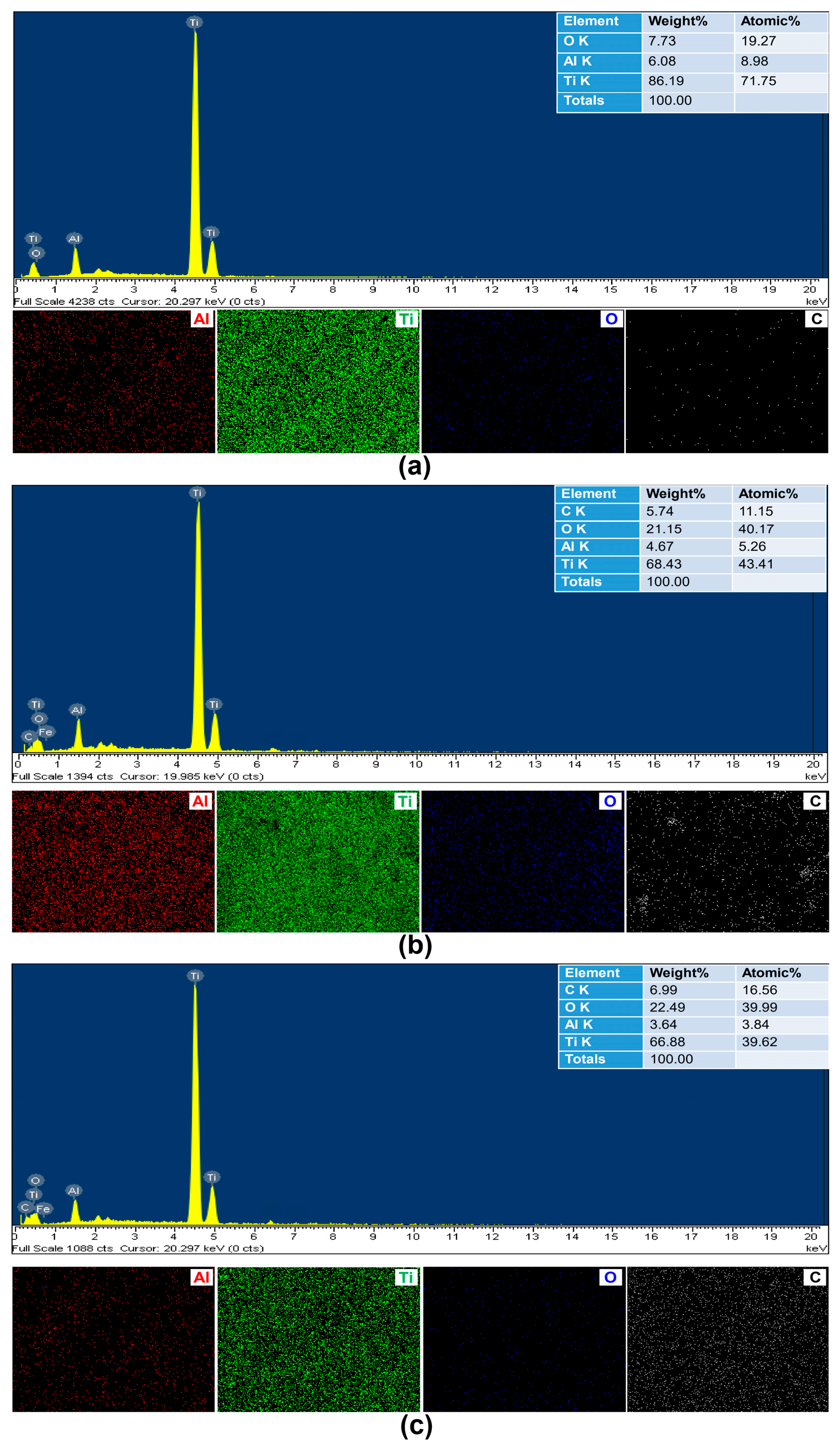

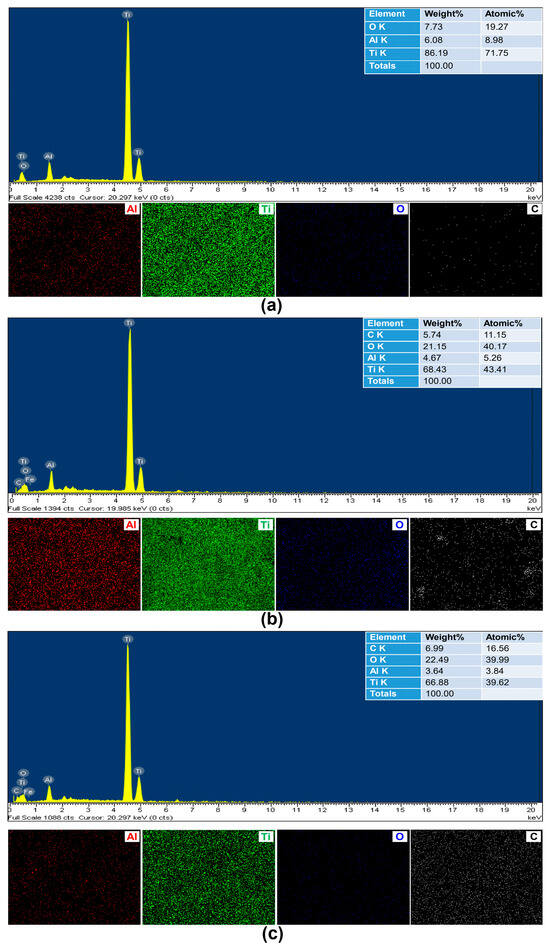

The EDS analysis results of the wear track for the Ti alloy sample are presented in Figure 9a. The results reveal that the main elements detected in the worn surface are Ti, Al, and O. Based on the combined EDS and SEM results, it can be concluded that the particles formed on the wear track surface of the Ti alloy after the friction test are primarily oxide particles, such as TiO2 and Al2O3. These oxide particles play an important role in reducing friction and preventing severe delamination during sliding by partially transforming sliding friction into rolling friction. Figure 9b and 9c show the EDS spectra of the CNT/Ti alloy and Gr/Ti alloy composites, respectively. In addition to the main elements Ti, Al, and O, the presence of C was also detected. Compared with the Ti alloy sample, the worn surfaces of the composites not only contain TiO2 and Al2O3 particles but also exhibit the presence of the reinforcing materials CNTs and Gr. The appearance of CNTs and Gr on the wear track surface significantly contributes to the reduction of both the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear rate of the composites. Furthermore, the substantial improvement in the mechanical properties, particularly hardness, also helps enhance the wear resistance of the composites. It is noteworthy that the carbon content on the wear track of the Gr/Ti alloy composite (6.99 wt.%) is higher than that of the CNT/Ti alloy composite (5.75 wt.%). This may be attributed to the easier fragmentation of Gr into smaller nanosheets compared to CNTs. These finer Gr sheets can form a more uniform lubricating layer over the wear surface, thereby providing a more effective reduction in friction compared to CNTs.

Figure 9.

EDS spectra and EDS mapping of worm surface of (a) sintered Ti alloy, (b) CNT/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% CNTs and (c) Gr/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% Gr.

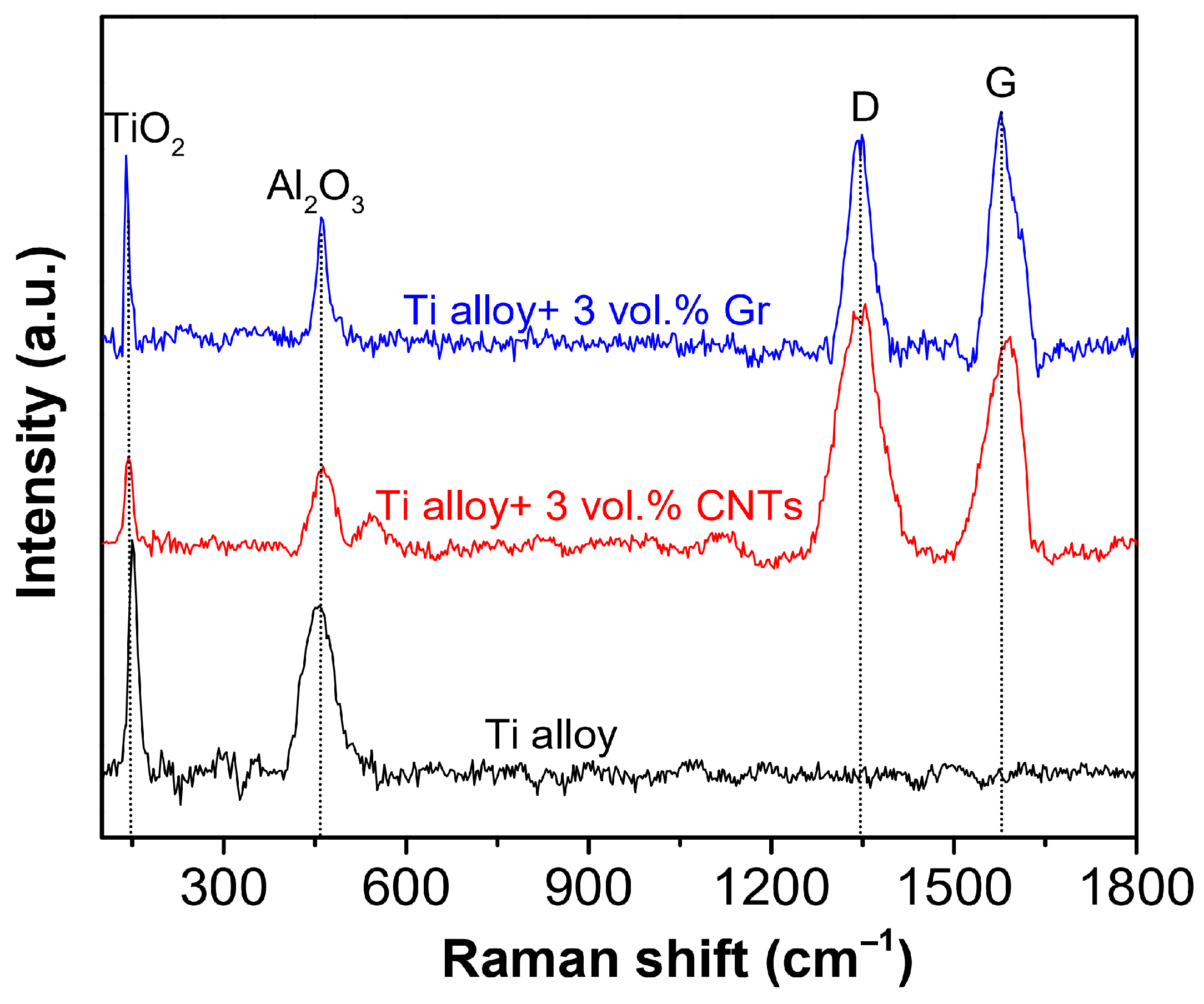

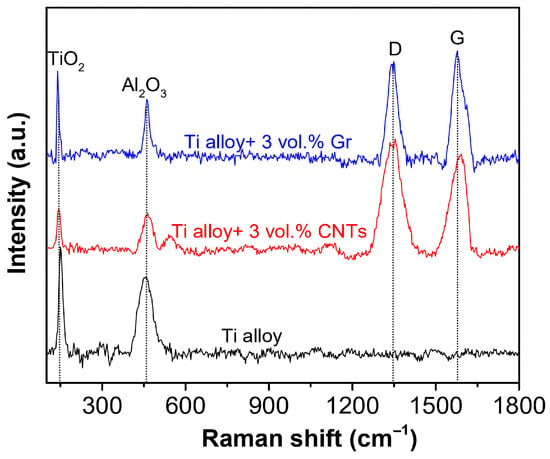

Figure 10 presents the Raman spectra of the worn surfaces of the samples. The results show that the worn surface of the Ti alloy exhibits two main peaks at 145 cm−1 and 467 cm−1, corresponding to the characteristic peaks of TiO2 and Al2O3, respectively [39,40]. In contrast, for the composite samples, in addition to the characteristic peaks of TiO2 and Al2O3, the D band (1356 cm−1) and G band (1596 cm−1), which are typical of the graphitic structure of CNTs and Gr, are also observed. These findings confirm that the worn surfaces of the composite samples contain metal oxide particles (TiO2, Al2O3) as well as CNTs in the CNT/Ti alloy composite or graphene in the Gr/Ti alloy composite.

Figure 10.

Raman spectra of worm surface of sintered Ti alloy, CNT/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% CNTs and Gr/Ti alloy composite containing 3 vol.% Gr.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

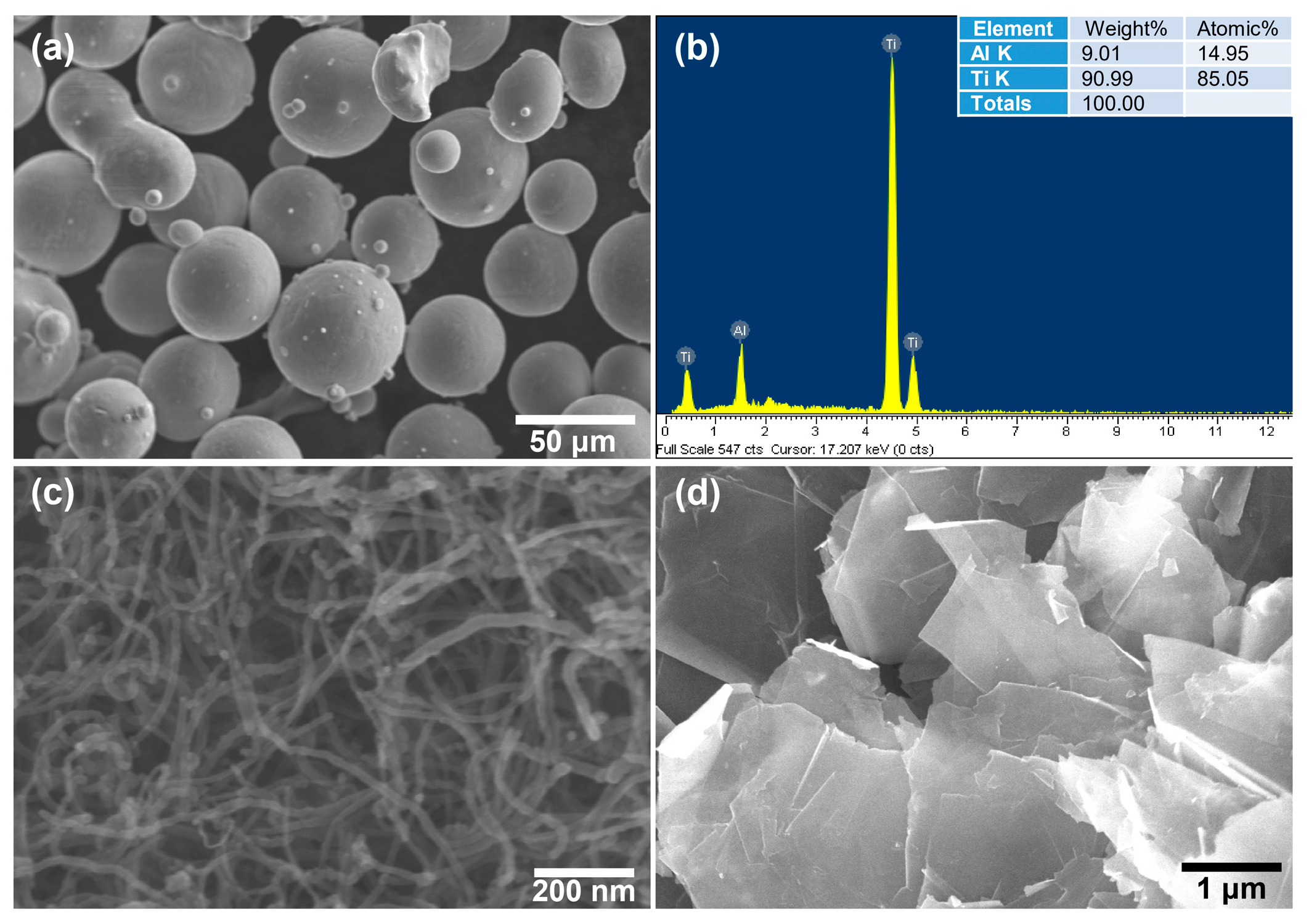

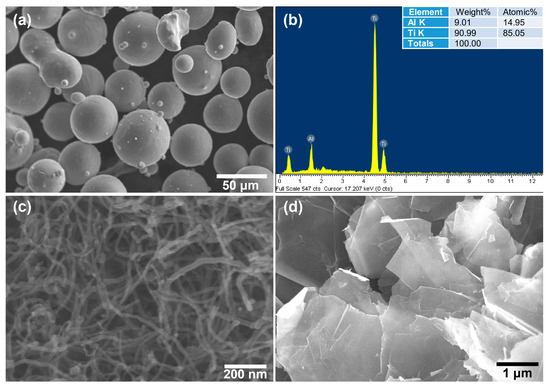

Commercial titanium alloy powder with an average particle size of approximately 30 μm (Figure 11a) and a composition of Ti (91%) and Al (9%), as confirmed by the EDS spectrum (Figure 11b), was supplied by SaiShu Technology (Guangzhou, China) Co., Ltd., China. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) with a purity of 95% and an average diameter of 20 nm, synthesized via the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method, were used as the reinforcing material (Figure 11c) [41]. Graphene (Gr), prepared by the liquid-phase plasma exfoliation method, possessed an average lateral size of approximately 2 μm and a thickness of about 5 nm (Figure 11d) [42].

Figure 11.

(a,b) SEM image and EDS spectra of Ti alloy powder, (c) SEM image of CNTs and (d) SEM image of Gr.

3.2. Fabrication of Ti Alloy Composites

- ❖

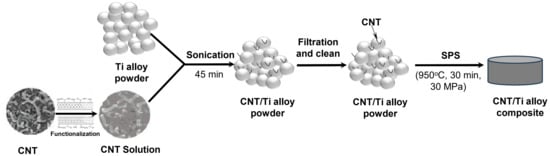

- Fabrication of CNT/Ti Alloy Composites

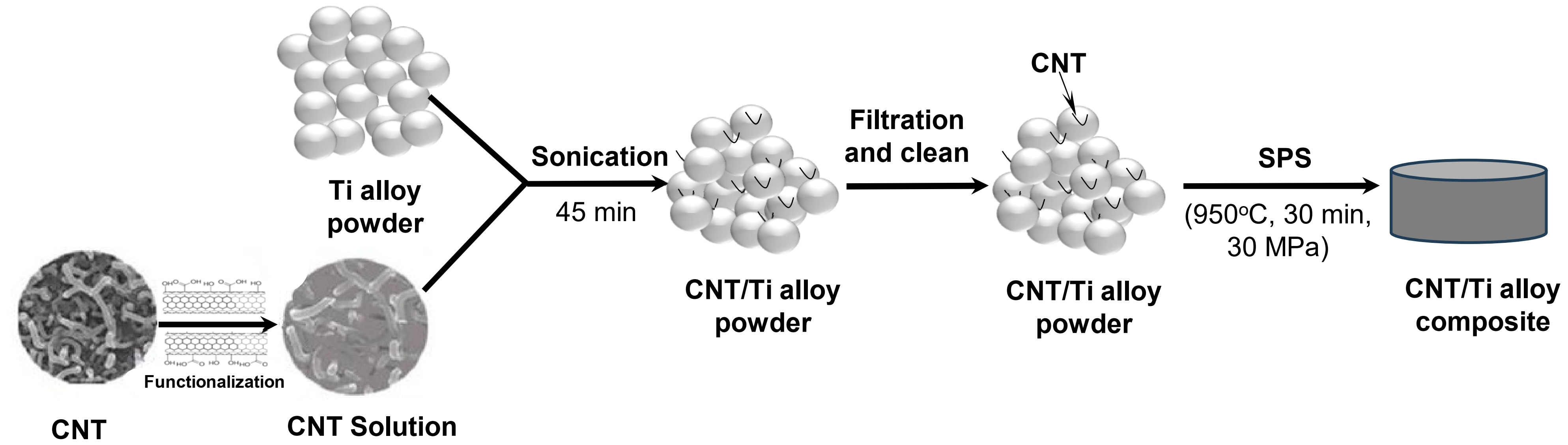

The fabrication process of the CNT/Ti alloy composites is illustrated in Figure 12. First, the CNTs were surface-functionalized using a mixed acid solution of HNO3:H2SO4 (1:3) at 70 °C for 2 h to obtain carboxyl-functionalized CNTs (CNT–COOH) [43]. The resulting CNT–COOH powder was then dispersed in ethanol to prepare a CNT–COOH suspension with a concentration of 1 g/L. Subsequently, Ti alloy powder was added to the CNT–COOH suspension and mixed using ultrasonic agitation to ensure uniform dispersion. The obtained mixture was then vacuum-filtered and dried to yield the Ti alloy–CNT composite powder. Finally, the composite powders were consolidated using a spark plasma sintering (SPS) system (LABOX 350, Sinter land Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The Ti alloy–CNT mixtures were sintered at 950 °C for 30 min under an applied pressure of 30 MPa in a vacuum environment to produce CNT/Ti alloy composites with CNT volume fractions of 1%, 2%, and 3 vol.%.

Figure 12.

Fabrication process of CNT/Ti alloy composite.

- ❖

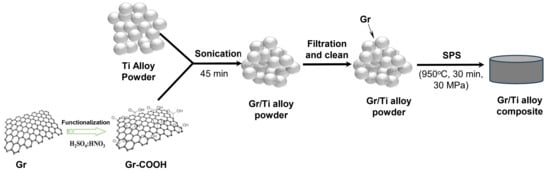

- Fabrication of Gr/Ti Alloy Composites

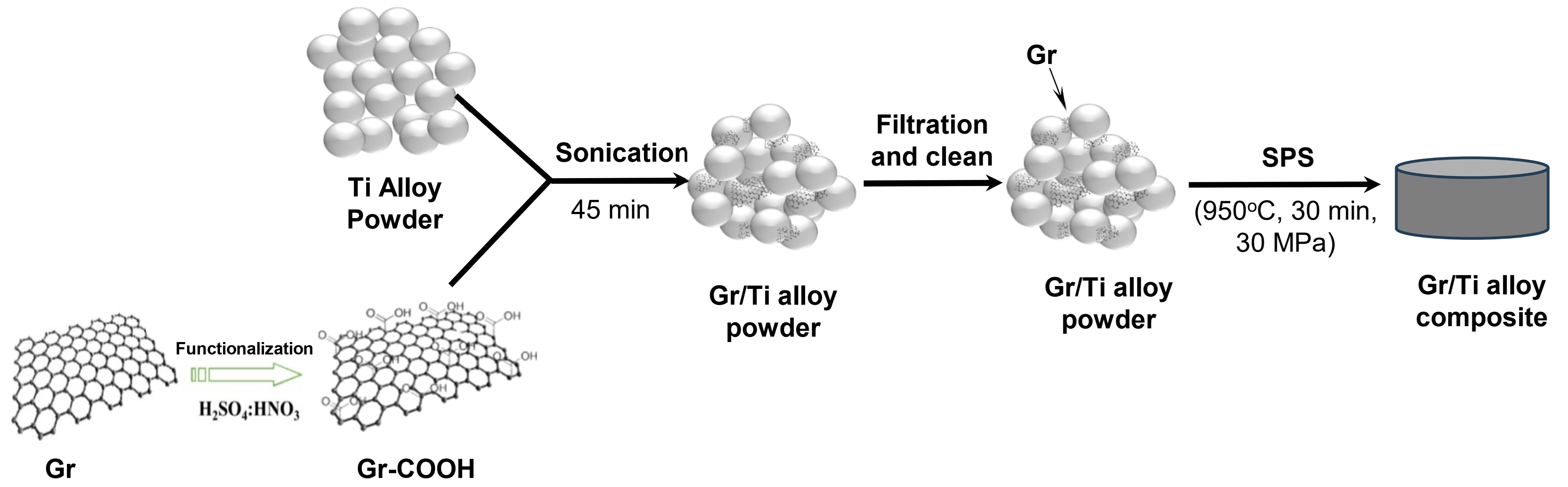

The fabrication process of the Gr/Ti alloy composites was similar to that used for the CNT/Ti alloy composites, as illustrated in Figure 13. Initially, Gr was surface-functionalized to obtain carboxyl-functionalized graphene (Gr–COOH), which was then dispersed in ethanol to prepare a Gr–COOH suspension with a concentration of 1 g/L. Subsequently, Ti alloy powder was added to the Gr–COOH suspension and mixed using ultrasonic agitation to ensure uniform dispersion of the Gr within the matrix. The resulting mixture was vacuum-filtered and dried to obtain the Ti alloy–Gr composite powders. Finally, the composite powders were consolidated using a SPS system (LABOX 350, Sinter Land Inc., Japan). The Ti alloy–Gr mixtures were sintered at 950 °C for 30 min under an applied pressure of 30 MPa in a vacuum environment to produce Gr/Ti alloy composites with graphene volume fractions of 1%, 2%, and 3 vol.%.

Figure 13.

Fabrication process of Gr/Ti alloy composite.

For comparison, a Ti alloy sample without reinforcement was also fabricated under identical conditions to evaluate and compare the effects of CNT and Gr reinforcements on the microstructure and properties of the composites.

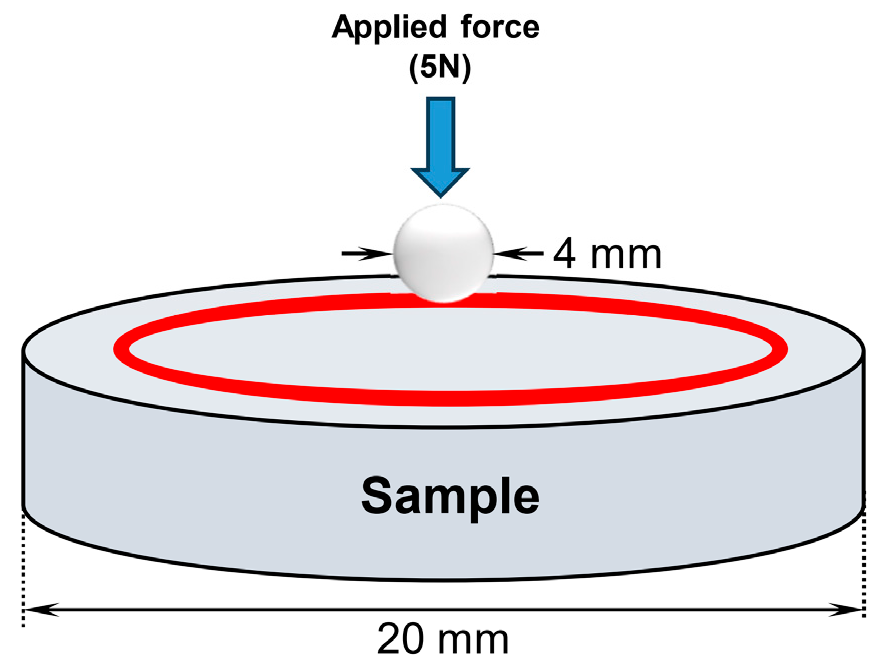

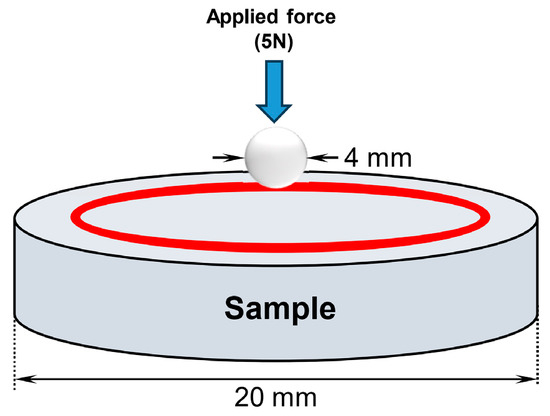

3.3. Characterizations

A scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Tokyo, Japan) was employed to examine the surface morphology of the materials. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Hitachi S-4800) and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD, TLS & ADAX SC200, AMETEK Inc., Berwyn, PA, USA) analyses were conducted to determine the grain size of the samples. The surface morphology of worn surface was determined by using the Keyence VHX-X1 digital microscope (Singapore). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA, D8 Advance diffractometer. Raman spectra were obtained with a Horiba XploRA ONE spectrometer (Singapore) equipped with a 532 nm excitation laser. The experimental density of the composites was determined using Archimedes’ principle with an analytical balance (AND GR-202, Tokyo, Japan). The relative density was calculated as the ratio of the experimental density to the theoretical density of the composite. The Vickers hardness of the samples was measured using a Vickers hardness tester (AVK-CO, Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan). The friction coefficient and wear rate of the sintered composites were evaluated using the ASTM G-99 standard [44] with a Pin-on-disk tribometer (TRB3, Anton Paar, Baden, Switzerland) under a normal load of 5 N and a sliding speed of 5 cm/s (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Schematic view of wear test basing on ASTM G-99 standard.

4. Conclusions

Ti-alloy matrix composites reinforced with CNTs and graphene were successfully fabricated via spark plasma sintering, demonstrating effective consolidation and retention of the carbon-based reinforcements. The addition of CNTs and Gr produced notable improvements in mechanical and tribological properties relative to the unreinforced Ti alloy. Hardness increased significantly with increasing carbon content, reaching maximum values of 445.8 HV for the composite containing 3 vol.% CNTs and 430.5 HV for the composite containing 3 vol.% Gr. The tribological behavior also improved markedly. Both CNTs and Gr lowered the friction coefficient and wear rate, with Gr yielding a slightly greater reduction due to the formation of a stable lubricating layer on the worn surface. Raman, SEM, and EDS analyses identified TiO2, Al2O3, and carbon-rich phases within the tribolayer, indicating that the synergistic interaction between oxide debris and carbonaceous films contributed to the enhanced wear resistance. The obtained results demonstrated that CNTs were more effective in improving hardness, whereas graphene offered greater benefits in enhancing wear resistance of Ti alloy-based composites. These findings confirm that both CNTs and graphene are promising reinforcements for Ti-based composites, providing simultaneous improvements in hardness, friction reduction, and wear resistance. These properties make the developed CNT/Ti and Gr/Ti composites promising candidates for demanding applications, including wear-resistant components and biomedical implants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.P. and P.V.T.; validation, P.V.T. and N.B.A.; formal analysis, N.B.A. and T.V.H.; investigation, P.V.T., T.V.H. and T.B.T.; data curation, N.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B.A. and P.V.T.; writing—review and editing, P.V.T. and D.D.P.; supervision, D.D.P.; project administration, D.D.P.; funding acquisition, D.D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) Vietnam under the grant number ĐTĐLCN.21/23.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- da Silva, L.R.R.; Pereira, A.C.; Monteiro, S.N.; Kuntoğlu, M.; Binali, R.; Khan, A.M.; Unune, D.R.; Pimenov, D.Y. Review of Advances and Challenges in Machining of Metal Matrix Composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 1061–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileiko, S. Carbon-Fibre/Metal-Matrix Composites: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Pang, A.; Luo, H.; Zhou, K.; Yang, H. Research Progress of Ceramic Matrix Composites for High Temperature Stealth Technology Based on Multi-Scale Collaborative Design. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 2770–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadimas, G.; Salonitis, K. Ceramic Matrix Composites for Aero Engine Applications—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaziem, W.; Khedr, M.; Abd-Elaziem, A.E.; Allah, M.M.A.; Mousa, A.A.; Yehia, H.M.; Daoush, W.M.; El-Baky, M.A.A. Particle-Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites (PMC) Fabricated by 3D Printing. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2023, 33, 3732–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhesana, M.; Sankhla, A.; Pawar, A.; Patel, K. A Comprehensive Review of Metal Matrix Composites: Manufacturing Techniques, Mechanical Properties, and Industrial Applications. In Advances in Sustainable Materials: Fundamentals, Modelling and Characterization; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, K.; Tarannum, N.; Chaudhary, P. Metal Matrix Composites: Revolutionary Materials for Shaping the Future. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafizadeh, M.; Yazdi, S.; Bozorg, M.; Ghasempour-Mouziraji, M.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Zarrabian, M.; Cavaliere, P. Classification and Applications of Titanium and Its Alloys: A Review. J. Alloys Compd. Commun. 2024, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Banerjee, R.; Huber, D.; Tiley, J.; Fraser, H.L. Formation of Equiaxed Alpha in TiB Reinforced Ti Alloy Composites. Scr. Mater. 2005, 52, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmefun, O.A.; Bayode, B.L.; Jamiru, T.; Olubambi, P.A. A Critical Review of Dispersion Strengthened Titanium Alloy Fabricated through Spark Plasma Sintering Techniques. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, F. Interface Configuration Effect on Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Three-Dimension Network Architectural Titanium Alloy Matrix Nanocomposites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 158, 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhuang, S.; Jia, D.; Pan, X.; Sun, Y.; Tu, F.; Lu, M. Facile Fabricating Titanium/Graphene Composite with Enhanced Conductivity. Mater. Lett. 2023, 333, 133680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, X.; Mu, X.; Fan, Q.; Ge, Y.; Guo, S. Simultaneously Enhancing Strength and Ductility in Graphene Nanoplatelets Reinforced Titanium (GNPs/Ti) Composites through a Novel Three-Dimensional Interface Design. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 216, 108851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Chen, B.; Li, J.S. Super-High-Strength Graphene/Titanium Composites Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Carbon 2021, 174, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.S.; Kingshott, P.; Wen, C. Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Titanium Metal Matrix Composites Prepared by Powder Metallurgy—A Review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2015, 40, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanda, O.S.; Mmuoegbulam, A.O.; Okezie, O.; Durumin Iya, N.I.; Mohammed, S.E.; James, P.H.; Muhammad, A.B.; Unimke, A.A.; Alim, S.A.; Yahaya, S.M.; et al. Recent Progress in Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: Critical Review. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2024, 26, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Kunjiappan, S.; Palanisamy, P. A Brief Review of Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites for Aerospace and Defense Applications. Int. Nano Lett. 2021, 11, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, O.; Bagci, N. A Short Review on Mechanical Properties of Graphene Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 6808–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Í.; Simões, S. Strengthening Mechanisms in Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites: A Review. Metals 2021, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.; Hassanzadeh, N.; Alizadeh, R.; Langdon, T.G. Graphene-Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites Produced by High-Pressure Torsion: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 20900–20928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Bao, R.; Yi, J.; Fang, D.; Tao, J.; Liu, Y. CNTs/Cu-Ti Composites Fabrication through the Synergistic Reinforcement of CNTs and in Situ Generated Nano-TiC Particles. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 770, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Chen, T.; Fu, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, C. Mechanical Response and Interface Properties of Graphene-Metal Composites: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.F.; Liang, T.; Zhang, D.; Choudhary, K.; Phillpot, S.R.; Sinnott, S.B. Titanium-Carbide Formation at Defective Curved Graphene-Titanium Interfaces. MRS Adv. 2018, 3, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, F.; Saba, F.; Shang, C. Graphene-TiC Hybrid Reinforced Titanium Matrix Composites with 3D Network Architecture: Fabrication, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 859, 157777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiderdoni, C.; Estournès, C.; Peigney, A.; Weibel, A.; Turq, V.; Laurent, C. The Preparation of Double-Walled Carbon Nanotube/Cu Composites by Spark Plasma Sintering, and Their Hardness and Friction Properties. Carbon 2011, 49, 4535–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trinh, P.; Lee, J.; Kang, B.; Minh, P.N.; Phuong, D.D.; Hong, S.H. Mechanical and Wear Properties of SiCp/CNT/Al6061 Hybrid Metal Matrix Composites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 124, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trinh, P.; Van Luan, N.; Minh, P.N.; Phuong, D.D. Effect of Sintering Temperature on Properties of CNT/Al Composite Prepared by Capsule-Free Hot Isostatic Pressing Technique. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2016, 70, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.M.A.K.; Chen, D.L. Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1901176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reihanian, M.; Bavi, M.A.; Ranjbar, K. CNT-Reinforced Al-XZr (x = 0.25, 0.5 and 1 Wt.%) Surface Composites Fabricated by Friction Stir Processing: Microstructural, Mechanical and Wear Characterisation. Philos. Mag. 2022, 102, 1011–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Mi, G.; Sun, Y.; Li, P. Unique Grain Refinement Mechanism of Graphene Oxide Reinforced High-Temperature Titanium Alloy Matrix Composite. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, F.; Liu, K. Understanding the Influencing Mechanism of CNTs on the Microstructures and Wear Characterization of Semi-Solid Stir Casting Al-Cu-Mg-Si Alloys. Metals 2022, 12, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami-Kermanshahi, M.; Hsiao, Y.C.; Lange, G.; Chang, S.H. Effects of Carbon Nanotube Addition on the Microstructures, Martensitic Transformation, and Internal Friction of Cu–Al–Ni Shape-Memory Alloys. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarniya, A.; Safavi, M.S.; Sovizi, S.; Azarniya, A.; Chen, B.; Hosseini, H.R.M.; Ramakrishna, S. Metallurgical Challenges in Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Metal Matrix Nanocomposites. Metals 2017, 7, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, P.; Du, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q. In-Situ Synthesis of TiC/Graphene/Ti6Al4V Composite Coating by Laser Cladding. Mater. Lett. 2020, 270, 127711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Choi, Y.; Oue, K.; Matsugi, K. Fabrication of In-Situ Rod-like TiC Particles Dispersed Ti Matrix Composite Using Graphite Power Sheet. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Sun, J.; Ding, F.; Gao, Y.; Gao, X.; Zheng, L. Molecular Insight into the Reversible Dispersion and Aggregation of Graphene Utilizing Photo-Responsive Surfactants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 567, 150840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Kong, H.; Chen, T.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sang, Y.; Hu, G. Effect of π–π Stacking Interfacial Interaction on the Properties of Graphene/Poly(Styrene-b-Isoprene-b-Styrene) Composites. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbenjo, A.O.; Olubambi, P.A.; Westraadt, J.E.; Lesufi, M.; Mphahlele, M.R. Interface Analysis of Spark Plasma Sintered Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Ti6Al4V. JOM 2019, 71, 2262–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, T.; Rout, T.K.; Palei, B.B.; Bajpai, S.; Kundu, S.; Bhagat, A.N.; Satpathy, B.K.; Biswal, S.K.; Rajput, A.; Sahu, A.K.; et al. Synthesis of α-Al2O3–Graphene Composite: A Novel Product to Provide Multi-Functionalities on Steel Strip Surface. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deen, S.S.; Hashem, A.M.; Abdel Ghany, A.E.; Indris, S.; Ehrenberg, H.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Anatase TiO2 Nanoparticles for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Ionics 2018, 24, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trinh, P.; Anh, N.N.; Hong, N.T.; Hong, P.N.; Minh, P.N.; Thang, B.H. Experimental Study on the Thermal Conductivity of Ethylene Glycol-Based Nanofluid Containing Gr-CNT Hybrid Material. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 269, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thanh, D.; Li, L.J.; Chu, C.W.; Yen, P.J.; Wei, K.H. Plasma-Assisted Electrochemical Exfoliation of Graphite for Rapid Production of Graphene Sheets. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 6946–6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trinh, P.; Anh, N.N.; Tam, N.T.; Hong, N.T.; Hong, P.N.; Minh, P.N.; Thang, B.H. Influence of Defects Induced by Chemical Treatment on the Electrical and Thermal Conductivity of Nanofluids Containing Carboxyl-Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 49937–49946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G-99; Standard Test Method for Wear and Friction Testing with a Pin-on-Disk or Ball-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).