Abstract

Silicon-based thermoelectric (TE) materials are demonstrating advanced capacity in environmental waste heat recovery. However, intrinsically high lattice thermal conductivity hinders the improvement of TE conversion efficiency. In the present work, a study of B4C composite for in situ nano-inclusions was carried out to enhance the TE properties of p-type Si80Ge20 materials. During sintering, B4C was demonstrated to form the SiC and B-rich ternary with a SiGe-based matrix, and the in situ formation of diverse nano-inclusions and the B dopant significantly reduced lattice thermal conductivity without deteriorating power factor (PF), weakening the coupling relationship between thermal and electrical transport properties to a certain extent. The carrier concentration of SiGe alloy samples was significantly increased, resulting in a 7.8% enhancement of PF for Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)0.3 at 873 K, while a low lattice thermal conductivity of 0.69 W m−1 K−1 is achieved. The optimal ZT is 1.08, which increased ~50% compared to the pristine sample, and an excellent average

of 0.62 is obtained among recent p-type SiGe-based TE materials’ works. Our research provides a new perspective for the optimization and practical application of p-type silicon germanium TE materials.

1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of electric vehicles (EVs) and renewed ambitions in deep-space exploration, the need for efficient energy recovery technologies is speedily increasing. In such terrestrial and extraterrestrial applications, a large fraction of the input energy is lost as heat—from power electronics, battery packs, and radioactive heat sources—so technologies that can directly convert this otherwise wasted thermal energy into electricity are increasingly attractive for improving system efficiency, autonomy, and endurance. Thermoelectric generators (TEGs), which directly convert a temperature gradient into electrical power with the advantages of being compact, scalable, having no moving parts, and being maintenance-free [1,2,3,4], are well suited to these demanding applications.

The figure of merit used to evaluate thermoelectric (TE) material properties is

, where S is the Seebeck coefficient,

is the electrical conductivity, T is the absolute temperature, and

and

represent the carrier thermal conductivity and lattice thermal conductivity, respectively [5]. Silicon–germanium (SiGe) alloys, which possess advantages of thermal stability, compatibility with established semiconductor processing, chemical stability and mechanical robustness, have a distinguished role among medium-high-temperature applications [6,7,8], typically the radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) for deep-space exploration [3,4,9].

Attributing to its excellent crystallinity of face-centered cubic structure, SiGe alloys have excellent electrical transport properties (i.e., power factor,

) but intrinsically high thermal conductivity (

), which is difficult to regulate individually due to the highly coupled relationship of

and

; thus, the ZT enhancement is limited [10]. So far, despite the continuous emergence of optimization strategies for TE materials [11], restraining the κ (especially the

) while remaining PF is the fundamental and effective direction for optimizing SiGe-based TE materials [12]. Additionally, Dresselhaus et al. indicate that the low-dimensionalized material system is a new direction for a high-performance TE material. They elucidated that nanocomposites exhibit significant scattering effects on mid-to-long-wavelength phonons [13]. Building upon this concept, a combined strategy of nanostructuring and grain boundary scattering was implemented through mechanical alloying and hot-pressing for fabricating nanostructured p-type SiGe alloys. The enhancement of ZT is due to a large reduction of

caused by the increased phonon scattering at the grain boundaries of the nanostructures [13,14].

In recent decades, the nanocomposite has provided a proven strategy for p-type bulk SiGe-based TE materials [15]. Previously, our group explored the TE performance of SiGe-based composite materials within various nano-inclusions. TaC was induced in the Si8Ge2B0.8 matrix, an electron modulation doping source was also introduced while scattering phonons, the valence band holes were recombined, the PF increased, and a ZT of 1.06 was achieved at 873 K [16]. B2O3 revealed similar behavior as nanocomposites in Si8Ge2B1.5 alloys [17]. During the sintering process, the decomposition of B2O3 generates B, forming an in situ doping effect, which suppresses the decrease in PF due to the existence of multi-scale nanostructures. ZT of 1.47 was obtained at 873 K. Also, dual oxides of SiO2 and Ga2O3 were co-composited for enhancing p-type Si8Ge2 alloys due to the in situ decomposition of Ga2O3 and high specific surface area of SiO2. The grain size was effectively controlled, and a hierarchically scattering structure was constructed, reducing the sound velocity and greatly suppressing the

. The ZT is better than most oxide-composited Si-based materials [18].

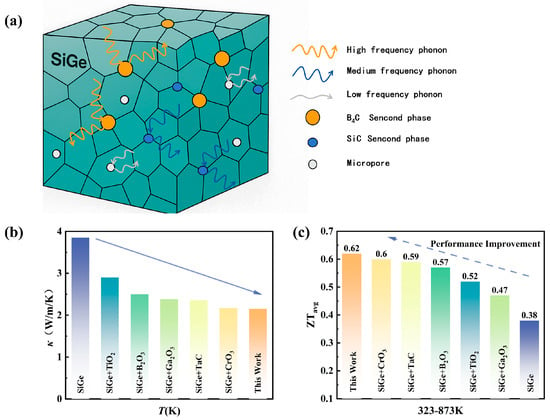

Based on the above considerations, it can be seen that the selection of composite materials is critical, especially since in situ reactions that occur during the bulk material forming process (ball milling and spark plasma sintering) often help to weaken the coupling relationship between TE parameters. B4C is an extremely hard, lightweight and high-temperature stable boron-based ceramic [19,20]. As a second phase in SiGe composites, it could bring significant mechanical enhancement, phonon scattering and lightweight advantages. In this study, SiGe composite TE alloys were synthesized by using B4C. During the synthesis process, two nano-second phases were in situ generated in the SiGe matrix, and the

was greatly suppressed without attenuation of PF. This process involves the reaction and atom rearrangement, promoting the formation of smaller nanoscale structures. As shown in Figure 1a, B4C reacts with the SiGe matrix, resulting in the precipitation of SiC

[21,22]. The extra B4C reserves as the other second phase, further enhancing phonon scattering. Meanwhile, the B-rich ternary (B12(C,Si,B)3) acts as a B dopant source, which increases the carrier concentration of the p-type SiGe matrix. The

was reduced to

at 873 K, representing a 28% reduction compared to the matrix. The optimized sample of Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)0.3 obtains a ZT of 1.08 at 873 K, and a higher level of

is achieved among similar works. Our work outperforms other comparable studies and provides a good suggestion for improving the TE performance of p-type SiGe materials.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of the B4C composite Si80Ge20B0.5 material, (b)

and (c)

in this work compared with the literature [10,16,17,18,23,24].

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Material Synthesis

All samples with a nominal composition of Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)x (x = 0~0.4 wt%) were fabricated by a planetary ball mill (WXQM-1A, TENCAN POWER, Changsha, China) and then processed by spark plasma sintering (SPS, LABOX-325, SINTER LAND INC, Tokyo, Japan). Specifically, the raw powders of Si, Ge, B, and B4C (all are 99.99%, Aladdin Corp., Nobuto, Japan) were weighed in a glove box under argon ambient and loaded into stainless steel jars along with stainless steel balls. The ratio of mass to material is 40:1. Then, the ball milling process was carried out for 25 h at 550 rpm under argon protection. At the end of ball milling, the prepared powder was placed into 15 mm diameter high-density graphite die and cold-pressed at 12 MPa for 1 min to eliminate gas and increase the density of the sample. After that, the graphite die was subjected to rapid SPS, the temperature was heated up to 1473 K at a rate of 100 K min−1 at 50 MPa and held for 3 min. Subsequently, the samples were cooled to room temperature (RT) under constant pressure in the furnace.

2.2. Characterizations

The crystal structure and phase composition of the sintered SiGe-based ingots were analyzed by using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advance, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany, Cu-Kα radiation,

) with the diffraction angle (2θ) of 10~70° with 0.02° step. The average grain size is calculated by using the Scherrer formula:

, where λ = 1.54056 Å is the wavelength of Cu Kα radiation [25], B is the corrected full-width at half-maximum (FWHM), θ is the satisfied angle of Bragg‘s principle, and K ≈ 0.9 is the Scherrer constant. The micromorphology and elemental distribution were analyzed by the scanning electron microscope (SEM, Gemini 300, ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) loaded with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Gemini 300, ZEISS, Germany) system. The TE measurement system (CTA-3, Beijing Corall Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to simultaneously evaluate the electrical conductivity σ and Seebeck coefficient S in the range of 323–873 K in a low-helium atmosphere, and the measurement error is about ±3%. The thermal diffusivity D was measured on a laser flash thermal analyzer (LFA 467 HT, NETZSCH, Selb, Germany) in the range of 323 K~873 K with the measurement error of ±6%. The specific heat

took the literature value [26], and the density

was measured by Archimedes’ drainage method [17,26]. The κ was obtained from:

[27]. The carrier concentration and mobility of the sample were evaluated by the Hall measurement system for vibration sample magnetometer (LakeShore, 7410, VSM, O’Fallon, MO, USA) at RT.

3. Results and Discussion

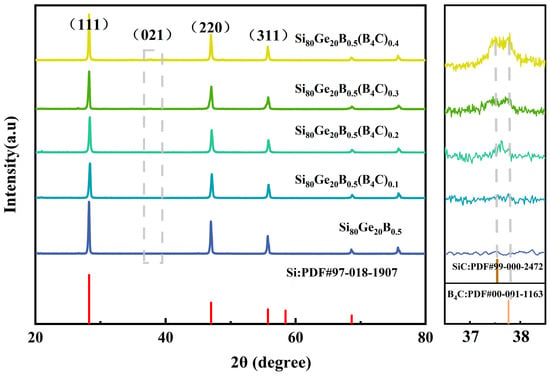

Figure 2 displays the XRD patterns of SiGe-based sintered samples with varying B4C contents (x = 0~0.4 wt%). The XRD results indicate that the diffraction peaks of all the samples present excellent agreement with the standard Si pattern (PDF#97-018-1907). The three main diffraction peaks located at 28.2°, 47°, and 55.7° indicate the formation of well-crystallized SiGe alloys corresponding to the (111), (220), and (311) crystal planes of Si, respectively. It was also observed that the augmented intensities of main peaks (111) with the increased B4C content were attributed to the increase in crystallinity of the SiGe matrix after the addition of B4C. Additionally, the average grain size increased from 44 nm to a maximum of 87 nm as calculated in the table. In recent decades. As the B4C content increases, a portion of the B4C reacts with the Si-containing matrix, forming SiC and B-rich phases near the grain boundaries. These B-rich intergranular phases significantly accelerate local material migration processes, effectively enhancing grain boundary mobility. Such enhanced grain growth behavior of sintered composites was observed in other SiGe-based alloys [28,29]. The partially enlarged details presented on the right of Figure 2 clearly show the presence of B4C and SiC peaks. Additionally, the peak intensities corresponding to B4C and SiC at angles of

and

becomes more pronounced as the content of B4C increases (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of Si80Ge20B0.5 composites with different B4C contents. The enlarged spectrum on the right shows the diffraction peaks of B4C and SiC in the diffraction angles of 36.5° and 38.5°, respectively.

At elevated temperature, B4C is known to react with Si to yield SiC and a B-rich ternary phase rim around the original B4C grains, which could be written in simplified form as follows [21]:

where molten Si reacts with B4C to form SiC and a B–Si–C ternary rim around original B4C grains. This dissolution–precipitation (core–rim) mechanism has been widely reported for reaction-bonded B4C–Si composites [30]. Although our SPS peak temperature (1473 K) is below the bulk melting point of Si, the combination of extensive process of mechanical alloying (which produces nanostructuring, high defect densities and intimate particle contact) and the pulsed current locally enhanced heating in SPS can promote localized solid-state reactions and/or transient local melting, enabling partial B4C consumption, SiC formation and redistribution of B that may diffuse into the SiGe matrix and act as a p-type dopant. The enhanced intensities of generated SiC and extra B4C peaks in XRD also confirmed this process. These in situ-formed phases markedly reduced

and modified carrier transport, thereby contributing to the composite’s superior TE performance relative to the SiGe matrix [23].

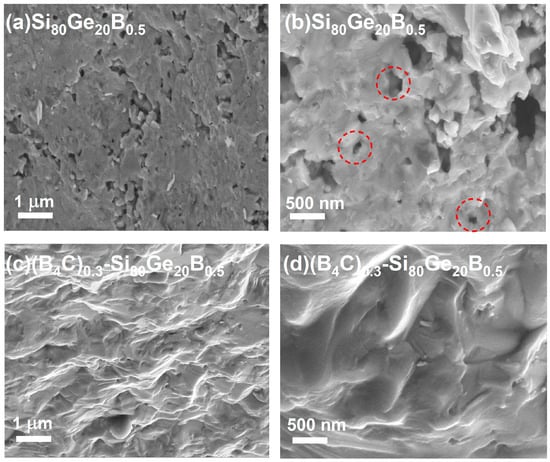

Figure 3 shows the cross-sectional view of different B4C contents. One can obviously see the enhanced densification with the increase in B4C. As shown in Table S1, the increased density of the SiGe composite can be attributed to the synergistic effect of improved powder packing and interfacial reaction bonding, which is induced by ball milling and SPS. The density of the typical sample (B4C)0.3-Si80Ge20B0.5 is approximately ~2.90 g cm−3, which is 96.3% of theoretical density calculated using the formula:

(x = 0.2 in our case) [31]. The density increases to a maximum of 2.91 g cm−3 with increasing B4C content in the composite, which is around 96.8% of the theoretical density.

Figure 3.

(a) The cross-sectional SEM view of the (B4C)0.1-Si80Ge20B0.5 sample, and (b) is a locally enlarged image of (a). (c) The cross-sectional view of the sample (B4C)0.3-Si80Ge20B0.5, and (d) is a locally enlarged image of (c).

Ball milling of the SiGe-B4C system refines grain and produces a more favorable particle size distribution that fills interstitial pores and raises the density [32], while the mechanically induced high defect density promotes subsequent mass transport during sintering. Under SPS, the pulsed-current-induced field-assisted heating and applied pressure accelerate interfacial diffusion. Concurrently, partial reaction between B4C and the Si-rich matrix (leading to SiC and B-rich ternary) can occur at the particle contacts, effectively “reaction-bonding” the microstructure and filling residual porosity [33]. The combined effect of these processes yields a more continuous, well-bonded microstructure and hence higher densification as B4C fraction increases [34], whose trend is consistent with the detection of SiC in our XRD data.

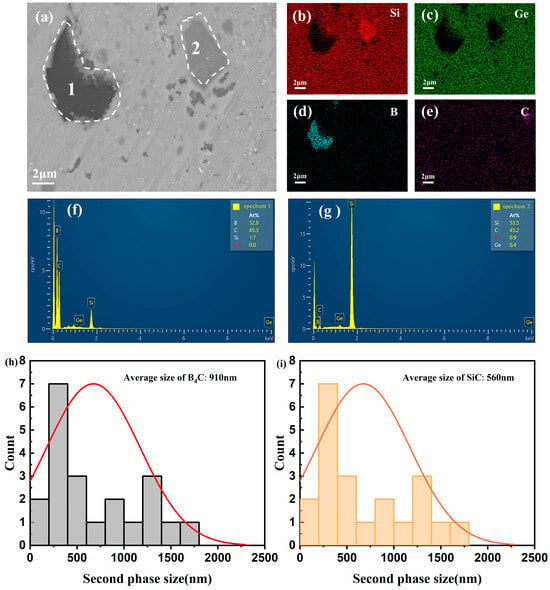

Figure 4a shows a cross-sectional SEM image of the Si80Ge20B0.5–(B4C)0.3 sample. A densely packed microstructure composed of obvious second phases is observed. Elemental maps of EDS mapping (Figure 4b–e) identify spatially separated B-rich and Si-rich regions, and point-scan analyses at positions 1 and 2 (Figure 4f,g) in Figure 4a confirm that the dispersed particles correspond to B4C and SiC, respectively. Such cases indicate partial reaction between B4C and the Si-rich matrix to form a SiC nanophase, while extra B4C remains unreacted. These observations are consistent with our previous analysis. As shown in Figure 4h,i, particle-size analysis indicates that the B4C particles are distributed from 100 to 1600 nm with an average diameter of ~910 nm, whereas the SiC particles range from 100 to 1600 nm with an average diameter of ~560 nm. The uniformly dispersed nanoparticles provide effective scattering centers for mid-to-long-wavelength phonons, while the larger, less uniformly distributed B4C particles can also influence charge-carrier transport in the nanostructured matrix [35,36,37,38]. EPMA data (Figure S2) further shows that the elemental distribution mapping indicates that increasing B4C content leads to a more homogeneous Si and Ge distribution, whereas B exhibits a tendency to cluster, consistent with the formation and growth of nanoscale secondary phases as B4C composition increases.

Figure 4.

(a) SEM image of the sample Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)0.3. (b–e) The EDS mapping of (a). (f,g) The point-scans at position 1 and position 2 of (a), respectively. (h,i) The grain diameter histograms of B4C and SiC, respectively.

Taken together, characterizations reveal a dense, well-bonded p-type SiGe matrix containing uniformly dispersed nano-to-submicron B4C and SiC secondary phases with localized B/C enrichment. These nanoscale heterogeneity microstructural features and modified elemental distribution are expected to enhance phonon scattering while simultaneously altering carrier behaviors [39,40,41].

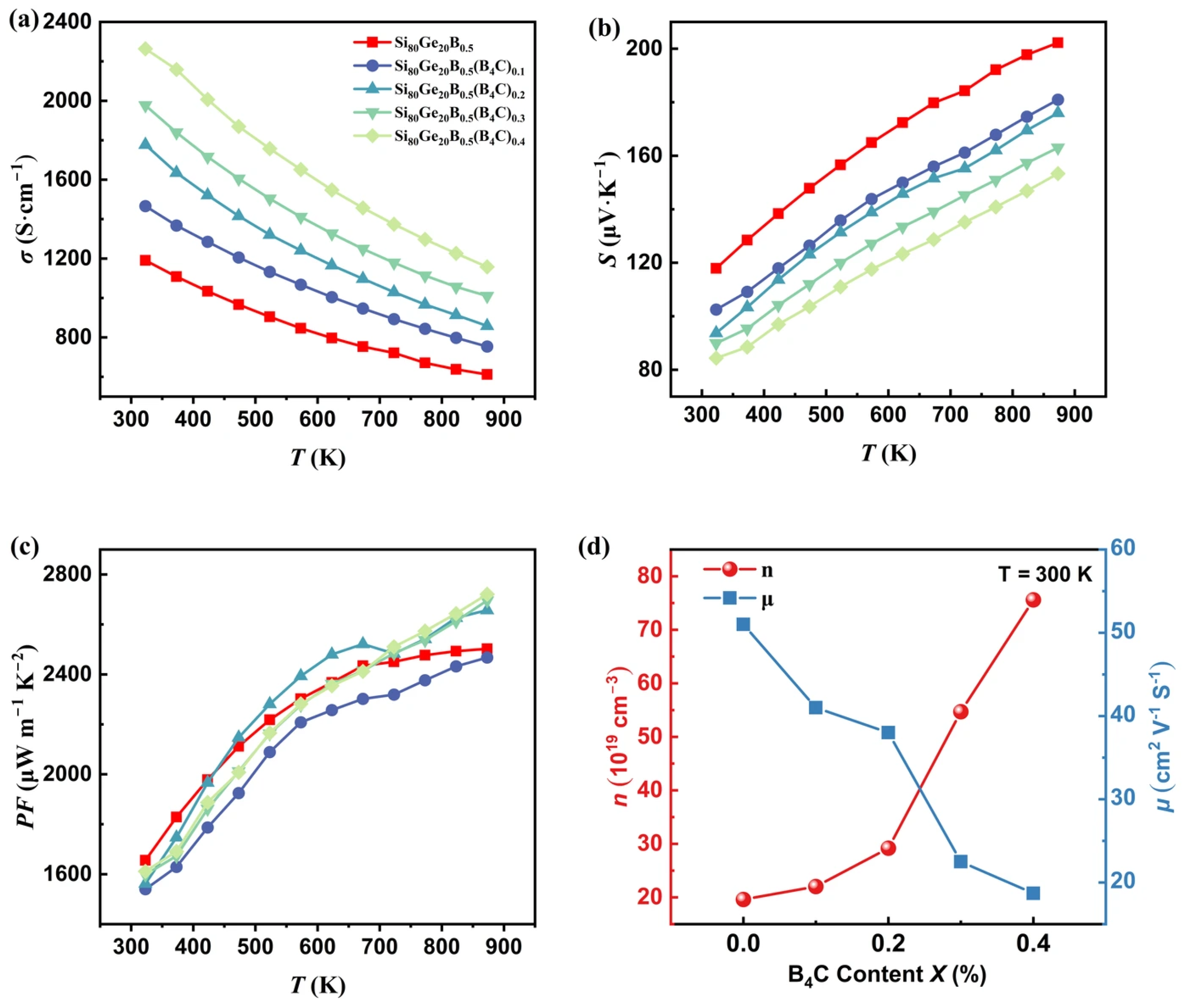

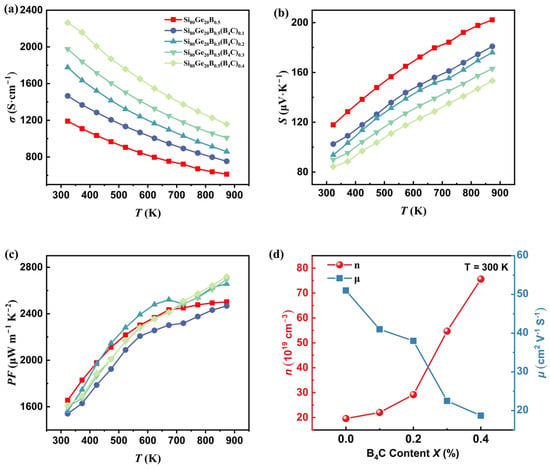

The electrical transport properties of the samples Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)x (x = 0~0.4 wt%) are shown in Figure 5. As shown in Figure 5a,b, S is positive for all samples, σ decreases and S increases for all samples with the increase in temperature. Those are consistent with the characteristics of p-type semiconductors. It was noted that the σ obviously increases with the B4C increasing, which is attributed to the increased carrier concentration (n), as revealed from the Hall measurement in Figure 5d.

Figure 5.

The variation trends of Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)x (x = 0~0.4 wt%) samples with respect to temperature for (a) electrical conductivity σ, (b) Seebeck coefficient S, (c) PF. (d) The carrier concentration n and carrier mobility µ depending on the change of B4C content.

As indicated before, reaction (1) describes the precipitation of a B-rich ternary phase. B is a well-established p-type (acceptor) dopant in Si/Ge and can diffuse into the SiGe matrix at high temperature. The released B that reaches substitutional lattice sites will generate holes and raise the measured n. Such a phenomenon of changes in n caused by the introduction of B-rich phase has also been observed in β-FeSi2 TE systems [42]. As a result, the PF of corresponding samples was enhanced. Figure 5c exhibits a PF trend of firstly decreasing and then increasing with the increase in B4C content in the temperature range, and a maximum 7.8% enhancement of PF is achieved at 873 K. Even though the change in PF is not significant, the introduction of B4C greatly restrains the

.

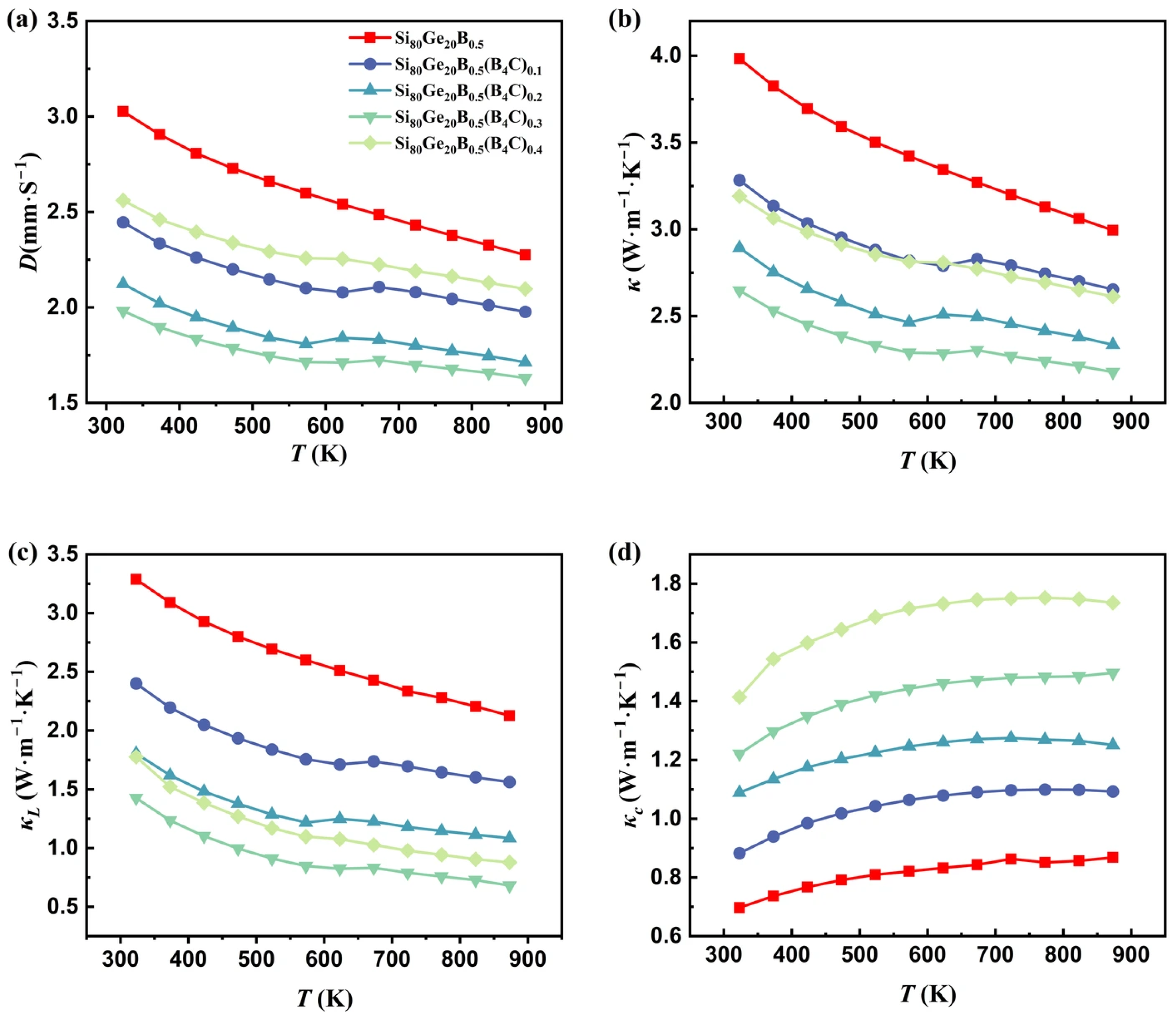

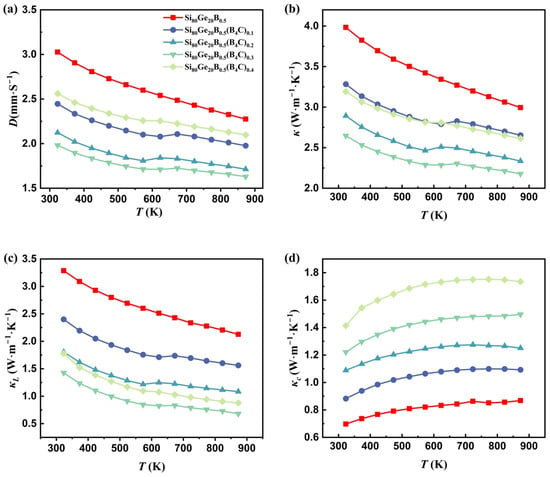

Figure 6a,b show the temperature-dependent D and

of the Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)x (x = 0~0.4 wt%) samples, respectively. At the range of 0~0.3 wt% of B4C, the digressive trend indicates the augmented phonon scattering with the increase in temperature. As B4C continues increasing to 0.4 wt%, D and

begin to increase. At low B4C loadings, well-dispersed B4C particles (and the minor SiC/B–rich ternary reaction products formed at particle contacts) provide abundant mass-contrast and interfacial scattering centers, while ball milling induced grain refinement and high defect densities further reducing phonon mean free paths; these effects collectively suppress

[31,43,44,45,46,47] (), as indicated in Figure 6c. The

is reduced by 0.68 W m−1K−1 of (B4C)0.3 at 873 K and 67.9% reduction compared to the pristine Si80Ge20B0.5. Thus, the carrier-contributed thermal transport remains relatively small.

Figure 6.

Temperature-dependent (a) thermal diffusion coefficients (D), (b) total thermal conductivity (), (c) lattice thermal conductivity () and (d) carrier thermal conductivity () for SiGe-B4C samples.

As B4C content increases continuously, however, particle agglomeration and growth reduce phonon scattering efficiency, the sample densities enhance thermal conduction, and the increased formation of reaction products and connected phases can also produce more continuous thermal pathways and enhance thermal conduction. Additionally, the rise in carrier concentration (n) with more B4C increases the

due to the Wiedemann–Franz law (, L is the Lorenz number:

[48]. As shown in Figure 6d,

displays the same trend as σ and further contributes to the increase in

. Finally, the

of the optimal sample Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)0.3 is ~2.17 W m−1K−1, which is 28% lower compared to pristine Si80Ge20B0.5 with a

of ~2.99 W m−1K−1 at 873 K. This indicates that our in situ reaction strategy can introduce multiple nano-phases and enhance phonon scattering while manipulating carrier doping. To some extent, the electrical and thermal transport performance are traded off.

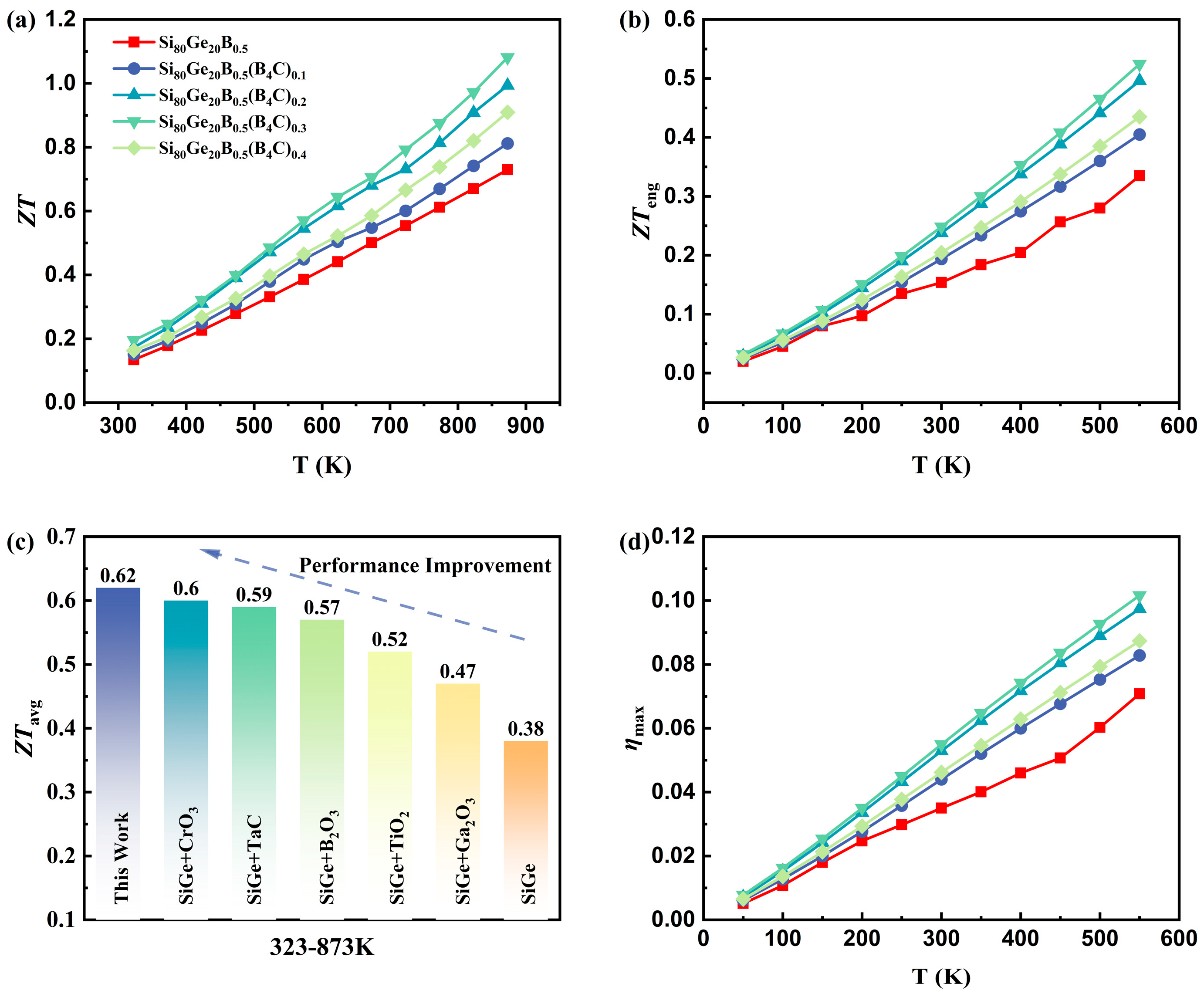

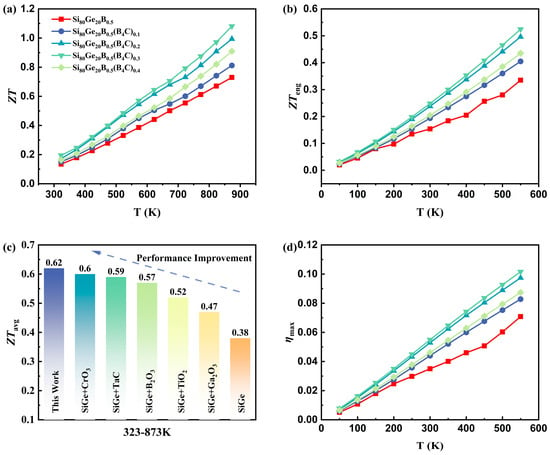

From the previous discussion, it can be seen that, by combining the composite B4C with ball milling and SPS sintering process, an in situ reaction occurs during the preparation process to generate several nano-inclusions in p-type SiGe matrix, which allow the thermal and electrical transport properties of the composite material to be simultaneously regulated. PF is slightly enhanced (7.8%), while

is strongly suppressed. The evaluation of ZT for Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)x (x = 0~0.4 wt%) is illustrated in Figure 7a. The ZT demonstrates a positive correlation with temperature, and an optimal value of 1.08 is achieved for Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)0.3 at 873 K, which is 52% higher than that of the pristine counterpart. A comparison of the

of 0.62 is obtained in the present work, as shown in Figure 7c, and a high level is achieved in comparison with the similar works of p-type SiGe-based TE materials [10,16,17,18,23,24], as presented in Figure 7c.

Figure 7.

Temperature-dependent (a) ZT of samples Si80Ge20B0.5-(B4C)x (x = 0~0.4 wt%), (b) engineering dimensionless

. (c) The average values of

in this work are compared with those reported studies [10,16,17,18,23,24] and (d) the maximum efficiency

.

To connect the material-level measurements to device-relevant performance, we introduce the engineering figure-of-merit

, which integrates the temperature-dependent transport properties over the operating window rather than relying on a single-point

. Practically,

is defined as follows:

where

and

denote the temperatures of the cold and hot sides. Unlike a simple average

,

separately accounts for the cumulative influence voltage generation, electrical resistance and thermal conductance across the temperature range, making it a more direct predictor under realistic operating conditions [23,49]. As shown in Figure 7b, the trend of

is consistent with ZT, and the maximum

of 0.52 is obtained at

, which is approximately 10% higher than that of the pristine sample. Additionally, a

is evaluated for the theoretical TE conversion efficiency of the prepared devices:

As illustrated in Figure 7d. The optimal sample

demonstrated the highest conversion efficiency of 10%. The present work exhibits a great potential for medium-high temperature power generation applications.

4. Conclusions

In the present research, B4C composited Si80Ge20B0.5 TE materials were prepared by ball melting and SPS. Microstructural analysis shows that, during SPS processing, B4C partially reacts with the SiGe matrix to form SiC and B-rich ternary phases, producing a dispersed population of nano-inclusions. The combined effect of these in situ inclusions yields a reduced

(~2.17

) without deteriorating PF (~2696 ), which are 28% restrained and 7.8% enhanced compared with the pristine counterpart, respectively. Consequently, the usual tight coupling between thermal and electrical transport is partially relaxed in the composite system. For the composition

the simultaneous carrier modulation and enhanced phonon scattering produce a peak ZT of 1.08, a 50% increase relative to the pristine Si80Ge20 sample, and the material attains an excellent

of 0.62 across the considered temperature range. The

and theoretical

are 0.52 and 10%, respectively, which exhibit a great potential for medium-high temperature power generation applications. These metrics place the optimized composite among the more competitive p-type SiGe-based TE alloys for medium-high temperature waste heat recovery applications. Overall, the B4C composite strategy provides a viable and scalable route to enhance p-type SiGe TE materials for automotive and aerospace waste-heat recovery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics13120402/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and H.C.; methodology, J.G. and H.C.; validation, H.L.; formal analysis, H.L., Y.G. and W.G.; investigation, H.L.; data curation, X.L., K.H. and J.-L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and Z.W.; supervision, L.M.; project administration, H.L. and L.M.; funding acquisition, H.L. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52402236, U21A2054 and 52273285), the Basic Research Fund of Guangxi Academy of Sciences (No. 2024YWF2117), and the Guangxi Young Talents Development Program (No. 2024QMJH-1908).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, J.; Yin, Z.; Hong, D.; Yuan, J. Densification Behavior and Sintering Kinetics of Al2O3-Based Ceramic Tool Materials via Spark Plasma Sintering. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 39129–39137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Singh, A. Dopant Dependent Microstructure of Hot-Pressed SiGe Alloys and Its Implications on Thermoelectric Properties. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2024, 674, 415534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D. Miniature Semiconductor Thermoelectric Devices. In CRC Handbook of Thermoelectrics; CRC Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, C.B.; Laskow, W.; Hanson, J.O.; Van Der Beck, R.R.; Gorsuch, P.D. Thermoelectric Properties of Pressure-Sintered Si0.8Ge0.2 Thermoelectric Alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 69, 4333–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Singh, A. High Temperature Si–Ge Alloy towards Thermoelectric Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Mater. Today Phys. 2021, 21, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, N. Sustainable Thermoelectric Materials for Solar Energy Applications: A Review. Solid State Sci. 2025, 160, 107784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, C.; Soulier, M.; Navone, C.; Roux, G.; Simon, J.; Volz, S.; Mingo, N. Thermoelectric Properties of Nanostructured Si1−xGex and Potential for Further Improvement. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 108, 124306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-L.; Li, N.-H.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.-G. Toward Efficient Thermoelectric Materials and Devices: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 7525–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G.; Lombardo, J.; Hemler, R.; Silverman, G.; Whitmore, C.; Amos, W.; Johnson, E.; Schock, A.; Zocher, R.; Keenan, T.; et al. Mission of Daring: The General-Purpose Heat Source Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.; Peng, Y.; Gao, J.; Kurosawa, M.; Nakatsuka, O.; Takeuchi, T.; Miao, L. Silicon-Based Low-Dimensional Materials for Thermal Conductivity Suppression: Recent Advances and New Strategies to High Thermoelectric Efficiency. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 60, SA0803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Jain, S.; Johari, K.K.; Candolfi, C.; Lenoir, B.; Dhakate, S.R.; Gahtori, B. Weak Electron-Phonon Coupling Contributing to Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance in n-Type TiCoSb Half-Heusler Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, G.A.; Hussain, M.A. The Maximum Possible Conversion Efficiency of Silicon-Germanium Thermoelectric Generators. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 70, 2694–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Chen, G.; Tang, M.Y.; Yang, R.G.; Lee, H.; Wang, D.Z.; Ren, Z.F.; Fleurial, J.-P.; Gogna, P. New Directions for Low-Dimensional Thermoelectric Materials. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Lee, H.; Lan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, G.; Wang, D.; Gould, R.W.; Cuff, D.C.; Tang, M.Y.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; et al. Enhanced Thermoelectric Figure-of-Merit in Nanostructured p-Type Silicon Germanium Bulk Alloys. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 4670–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadea, G.; Pacios, M.; Morata, Á.; Tarancón, A. Silicon-Based Nanostructures for Integrated Thermoelectric Generators. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 423001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liang, J.; Chen, J.-L.; Peng, Y.; Lai, H.; Nong, J.; Liu, C.; Ding, W.; Miao, L. Realizing High Thermoelectric Performance for P-Type SiGe in Medium Temperature Region via TaC Compositing. J. Mater. 2023, 9, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, J.; Peng, Y.; Liu, C.; Shen, J.B.; Liao, Q.; Chiew, Y.L.; Oshima, Y.; Li, F.C.; Zhang, Z.W.; Miao, L. Ultra-Low Thermal Conductivity in B2O3 Composited SiGe Bulk with Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance at Medium Temperature Region. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 4120–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M.; Shi, R.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Miao, L.; Wei, H. Thermoelectric Enhancement of P-Type Si80Ge20 Alloy via Co-Compositing of Dual Oxides: Respective Regulation for Power Factor and Thermal Conductivity by β-Ga2O3 and SiO2 Aerogel Powders. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, I.M. Investigation into the Structural, Chemical and High Mechanical Reforms in B4C with Graphene Composite Material Substitution for Potential Shielding Frame Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beder, M. The Effect of High B4C Ratio on the Improvement of Mechanical Properties and Wear Resistance of Al2024/B4C Composites Fabricated by Mechanical Milling-Assisted Hot Pressing. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 9528–9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Sun, S.; Ye, J.; Zhang, C.; Ru, H. Continuous SiC Skeleton-Reinforced Reaction-Bonded Boron Carbide Composites with High Flexural Strength. Materials 2023, 16, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z. Effect of Carbon Content on Mechanical Properties of Boron Carbide Ceramics Composites Prepared by Reaction Sintering. Materials 2022, 15, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, J.; Miao, L.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Lai, H. Phonon Relaxation Effect by Regeneration of Nano-Inclusions in SiGe for Ultralow Thermal Conductivity and Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance. Mater. Today Phys. 2024, 43, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Basu, R.; Sarkar, P.; Singh, A.; Bohra, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhatt, R.; Meshram, K.N.; Samanta, S.; Bhatt, P.; et al. Enhanced Thermoelectric Figure-of-Merit of p-Type SiGe through TiO2 Nanoinclusions and Modulation Doping of Boron. Materialia 2018, 4, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monshi, A.; Foroughi, M.R.; Monshi, M.R. Modified Scherrer Equation to Estimate More Accurately Nano-Crystallite Size Using XRD. World J. Nano Sci. Eng. 2012, 2, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ying, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, G. First-Principles Calculations of Structural Stability, Elastic, Dynamical and Thermodynamic Properties of SiGe, SiSn, GeSn. Superlattices Microstruct. 2012, 52, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, J.; Bonini, N.; Kozinsky, B.; Marzari, N. Role of Disorder and Anharmonicity in the Thermal Conductivity of Silicon-Germanium Alloys: A First-Principles Study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 45901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugasami, R.; Vivekanandhan, P.; Kumaran, S.; Suresh Kumar, R.; John Tharakan, T. Simultaneous Enhancement in Thermoelectric Performance and Mechanical Stability of P-Type SiGe Alloy Doped with Boron Prepared by Mechanical Alloying and Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 773, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favier, K.; Bernard-Granger, G.; Navone, C.; Soulier, M.; Boidot, M.; Leforestier, J.; Simon, J.; Tedenac, J.-C.; Ravot, D. Influence of in Situ Formed MoSi2 Inclusions on the Thermoelectrical Properties of an N-Type Silicon–Germanium Alloy. Acta Mater. 2014, 64, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.F.; Su, Y.C.; Cheng, Y.B. Formation and Sintering Mechanisms of Reaction Bonded Silicon Carbide-Boron Carbide Composites. Key Eng. Mater. 2007, 352, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Singh, A.; Bohra, A.; Basu, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhatt, R.; Meshram, K.N.; Roy, M.; Sarkar, S.K.; Hayakawa, Y.; et al. Boosting Thermoelectric Performance of P-Type SiGe Alloys through in-Situ Metallic YSi2 Nanoinclusions. Nano Energy 2016, 27, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.-W.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Wang, W.-M.; Fu, Z.-Y.; Wang, H. Effect of Particle Size on Densification and Mechanical Properties of Hot-Pressed Boron Carbide: Effect of Particle Size on Densification and Mechanical Properties of Hot-Pressed Boron Carbide. J. Inorg. Mater. 2013, 28, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuault, A.; Marinel, S.; Savary, E.; Heuguet, R.; Saunier, S.; Goeuriot, D.; Agrawal, D. Processing of Reaction-Bonded B4C–SiC Composites in a Single-Mode Microwave Cavity. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Zhang, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, W.; He, Q.; Ren, L.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Z. B4C-Based Hard and Tough Ceramics Densified via Spark Plasma Sintering Using a Novel Mg2Si Sintering Aid. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathula, S.; Jayasimhadri, M.; Gahtori, B.; Kumar, A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Dhar, A. Enhancement in Thermoelectric Performance of SiGe Nanoalloys Dispersed with SiC Nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 25180–25185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, B.; Hao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lan, Y.; Minnich, A.; Yu, B.; Yan, X.; Wang, D.; Muto, A.; Vashaee, D.; et al. High-Thermoelectric Performance of Nanostructured Bismuth Antimony Telluride Bulk Alloys. Science 2008, 320, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemens, P.G. The Scattering of Low-Frequency Lattice Waves by Static Imperfections. Proc. Phys. Society. Sect. A 1955, 68, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenko, A.; Moskovskikh, D.; Korotitskiy, A.; Gorshenkov, M.; Zakharova, E.; Fedorov, A.; Parkhomenko, Y.; Khovaylo, V. Thermoelectric Properties and Cost Optimization of Spark Plasma Sintered n-Type Si0.9Ge0.1-Mg2Si Nanocomposites. Scr. Mater. 2018, 146, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczech, J.R.; Higgins, J.M.; Jin, S. Enhancement of the Thermoelectric Properties in Nanoscale and Nanostructured Materials. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 4037–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Lee, H.; Lan, Y.C.; Zhu, G.H.; Joshi, G.; Wang, D.Z.; Yang, J.; Muto, A.J.; Tang, M.Y.; Klatsky, J.; et al. Enhanced Thermoelectric Figure of Merit in Nanostructured N-Type Silicon Germanium Bulk Alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 193121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-G.; Han, G.; Yang, L.; Cheng, L.; Zou, J. Nanostructured Thermoelectric Materials: Current Research and Future Challenge. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2012, 22, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Nagai, H.; Oda, E.; Katsuyama, S.; Majima, K. Thermoelectric Properties of β-FeSi2 with B4C and BN Dispersion by Mechanical Alloying. J. Mater. Sci. 2002, 37, 2609–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, O.; Singh, S.; Hirata, K.; Kuga, K.; Harish, S.K.; Shimomura, M.; Adachi, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Matsunami, M.; Takeuchi, T. Synergetic Enhancement of the Power Factor and Suppression of Lattice Thermal Conductivity via Electronic Structure Modification and Nanostructuring on a Ni- and B-Codoped p-Type Si–Ge Alloy for Thermoelectric Application. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 5621–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathula, S.; Jayasimhadri, M.; Gahtori, B.; Singh, N.K.; Tyagi, K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Dhar, A. The Role of Nanoscale Defect Features in Enhancing the Thermoelectric Performance of P-Type Nanostructured SiGe Alloys. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 12474–12483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhatt, R.; Roy, M.; Ahmad, S.; Singh, A.; Navaneethan, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Aswal, D.K.; Gupta, S.K. Improved Thermoelectric Performance of Hot Pressed Nanostructured N-Type SiGe Bulk Alloys. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 6922–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lukas, K.C.; Liu, W.; Opeil, C.P.; Chen, G.; Ren, Z. Effect of Hf Concentration on Thermoelectric Properties of Nanostructured N-type Half-heusler Materials HfxZr1–xNiSn0.99Sb0.01. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudeu, P.F.P.; D’Angelo, J.; Kong, H.; Downey, A.; Short, J.L.; Pcionek, R.; Hogan, T.P.; Uher, C.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Nanostructures versus Solid Solutions: Low Lattice Thermal Conductivity and Enhanced Thermoelectric Figure of Merit in Pb9.6Sb0.2Te10-xSex Bulk Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14347–14355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S.; Gibbs, Z.M.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; Snyder, G.J. Characterization of Lorenz Number with Seebeck Coefficient Measurement. APL Mater. 2015, 3, 41506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Gao, J.; Miao, L.; Liu, C.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.-L.; Lai, H.; Hu, K. Simultaneous Optimization of Power Factor and Thermal Conductivity via Charge Transfer Effect and Enhanced Scattering of Phonons in Si80Ge20P1/CoSi2 Composites. J. Mater. 2025, 11, 100874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).