Abstract

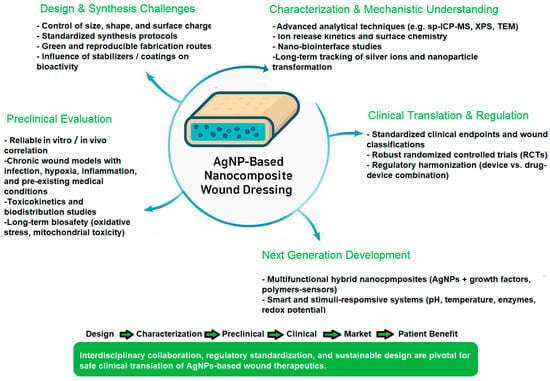

Wound healing is a complex biological process involving haemostasis, inflammation, cellular proliferation, and remodelling. The use of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in wound care has gained significant attention due to their potent antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and tissue-regenerating properties. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the role of AgNPs in wound healing, focusing on their mechanisms of action, efficacy, and clinical applications. The antimicrobial activity of AgNPs helps prevent infections in both acute and chronic wounds, while their ability to modulate inflammation and promote angiogenesis accelerates tissue repair. Various AgNP-based delivery systems, including hydrogels, nanofiber dressings, and composite biomaterials, are explored in the context of wound management, with special emphasis on smart, stimuli-responsive wound dressings. Additionally, clinical evidence supporting the effectiveness of AgNPs in treating chronic, burn, and surgical wounds is reviewed, along with considerations of their safety, cytotoxicity, and regulatory challenges. Although AgNPs present a promising alternative to conventional wound dressings and antibiotics, further research is needed to optimize their formulations and ensure their long-term safety. This review aims to provide insights into current advancements and future perspectives of AgNP-based wound-healing therapies.

Keywords:

wound healing; silver nanoparticles; AgNPs; antimicrobial activity; anti-inflammatory; tissue regeneration; angiogenesis; hydrogels; nanofiber dressings; composite biomaterials; smart wound dressings; chronic wounds; burns; surgical wounds; cytotoxicity; safety; clinical applications; regulatory challenges; tissue repair; nanotechnology in medicine 1. Introduction: Wounds and the Wound Healing Process

A wound is an injury that disrupts the integrity of the skin, mucous membranes, or deeper tissues, resulting from accidental trauma, surgical procedures, or certain underlying medical conditions. Wounds can be classified by aetiology and appearance. According to aetiology, wounds can be acute and chronic [1,2]. Acute wounds occur suddenly and heal normally, while chronic wounds are characterized by a delayed or impaired healing process, resulting in persistent inflammation and pain, infectious processes including biofilm development, and the presence of non-viable tissue. The appearance of wounds varies widely depending on aetiology, but roughly speaking, wounds can be open or closed. In open wounds (abrasions, lacerations, incisions, punctures, avulsions, burns), the integrity of the protective skin barrier or mucosal surface is disrupted, exposing the underlying tissue and increasing the risk of infection. On the other hand, in closed wounds (contusions, blisters, seromas, hematomas, crush injuries), the skin remains intact, but the underlying tissues and/or blood vessels are damaged [3,4,5].

Regardless of the wound type, the normal healing process consists of four sequential, overlapping stages involving a complex network of signalling molecules and cells, closely interconnected within the wound-healing cascade. The four phases of wound healing are: haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue remodelling [6,7].

Haemostasis is the body’s immediate response to injury, aiming to prevent excessive bleeding by forming a clot. Basically, adhesion and aggregation of platelets at the damaged site form an initial plug, which is further stabilized by a fibrin mesh, a protein produced during the clotting cascade.

The key aim of the inflammation phase of the wound healing process is to prevent infection. Besides their essential role in clotting, platelets also produce a plethora of growth factors and cytokines, which act as chemical signals regulating the healing cascade. For instance, the release of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) by platelets plays a dual role. On one hand, these proteins initiate chemotaxis of neutrophils and macrophages, which destroy debris and bacteria, and on the other hand, they stimulate the immune blood cells to secrete additional cytokines like the fibroblast growth factor (FGF), PDGF, TNF-α (tumour necrosis factor alpha), and IL-1 (interleukin-1) [6,7,8].

Once the inflammatory response is balanced and the debris is removed, the proliferation phase begins to repair the defect. The proliferative stage encompasses several simultaneously occurring processes, namely angiogenesis, fibroblast migration, epithelialization, and wound retraction [6,7].

The final remodelling phase of wound healing involves strengthening and refining the newly developed tissue. This stage is characterized by the replacement of the initial type III collagen by the stronger type I collagen, decreased vascularity, and scar formation. However, full restoration of the original tissue’s tensile strength is never achieved [7].

Classical wound care faces several critical challenges, particularly in the treatment of chronic wounds and burn wounds [9,10,11]. One major issue is the dynamic changes in the wound environment during healing [12,13,14]. Local factors such as hypoxia, ischemia, oxidative stress, enzymatic degradation of growth factors by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), infection, pathogenic biofilm formation, moisture imbalance, and the development of necrosis all pose serious threats to the patient’s health. In many cases, conventional treatments are unable to effectively address and overcome these risks. The clinical picture is even more complicated by systemic factors in diabetic, elderly, malnourished, or chronically ill patients. Achieving homeostasis (a stable, well-balanced internal environment) in each stage of wound healing is crucial for successful wound repair [7]. During the haemostasis stage, transient hypoxia resulting from vasoconstriction and increased oxygen demand during clotting triggers the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1). HIF-1, in turn, regulates the expression of vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), stimulating neovascularization. HIF-1 also induces expression of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) genes and the production of nitric oxide (NO) [15]. NO, a potent vasodilator, counterbalances vasoconstriction, restores blood flow and oxygen delivery, and helps prevent ischemia. It also inhibits platelet aggregation, helping prevent excessive blood clotting. Although acute hypoxia in the early phase of wound healing is beneficial, prolonged or unbalanced hypoxia is detrimental to later stages of the process. On the other hand, ROS such as the superoxide radical anion (O2−). increases fibrin deposition during the haemostasis stage, while H2O2 induces the recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils [16]. ROS play important roles not only during haemostasis but also along the whole wound repair process. During inflammation, ROS activate immune cells and help prevent infection by destroying pathogens. ROS modulate cellular signalling pathways involved in the proliferation stage, promoting angiogenesis and the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Eventually, ROS contributes to collagen remodelling in the final stage of wound repair [17,18]. However, excessive ROS levels lead to oxidative stress, which damages tissues and disrupts the healing process, resulting in chronic wounds. The remodelling stage requires a delicate, continuously regulated balance between the breakdown of damaged extracellular matrix (ECM)—including collagen and other proteins—by MMPs, and the synthesis of new collagen by fibroblasts to rebuild the ECM [19]. Strict control of proteolytic activity is therefore crucial for successful tissue repair, and this is achieved by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [13,20]. An imbalance between proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors underlies the abnormal healing seen in chronic ulcers.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are emerging as a valuable therapeutic option for wound care due to their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as their ability to support the normal progression of acute wound healing through all four stages and to prevent delayed or impaired tissue repair and chronic wound formation [21,22,23].

This paper aims to provide an up-to-date overview of the complex role of AgNPs in wound healing, including mechanistic insights based on current knowledge. It also reviews currently available AgNPs-based nanomaterials—such as AgNPs-coated wound dressings, nanofibers, hydrogels, and nanocomposite semipermeable film dressings—and their performance in preclinical studies and clinical trials. Safety concerns, risks, and limitations, as well as future challenges and perspectives in the development of AgNPs-based wound care strategies, are also addressed.

2. Effects of AgNPs on Wound Healing with Mechanistic Insights

2.1. Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Activities

The antimicrobial properties of silver and its compounds have been recognized for centuries. Even in ancient times, diluted silver salt solutions were used to treat eye infections in newborns and burn wounds [21,22,23,24,25]. As a result of the recent rapid and significant advances in metallic nanoparticle research, the effects and applications of AgNPs in wound care have received growing, widespread attention. Silver-based nanomaterials are used in wound dressings for their ability to effectively prevent and control bacterial colonization and pathogenic biofilm formation, as well as to manage infections, thereby facilitating and promoting wound healing. Although the precise mechanism underlying the antimicrobial effects of AgNPs has not yet been fully elucidated, several key molecular and cellular targets have been identified, and the effects of AgNPs on these targets have been partially clarified [21,22,23,26,27].

The first step in the complex antibacterial mechanism of AgNPs involves the attachment of nanoparticles to the negatively charged bacterial cell wall and membrane, primarily driven by electrostatic attraction to the positively charged silver ions [28,29,30]. Various mechanisms underlie the antimicrobial activity of AgNPs, including the release of silver ions, the generation of ROS in vivo, increased oxidative stress, alterations in important cellular and molecular structures such as the cell membrane and ribosomes, and impacts on protein synthesis, DNA, and intracellular metabolic pathways.

2.1.1. Oxidative Dissolution of AgNPs in Biological Media and the Effect of Some Important Physicochemical Characteristics of AgNPs on the Rate of Silver Ions Release and Antibacterial Activity

There is ongoing scientific debate about whether the antibacterial activity is primarily due to the intrinsic properties of the metallic particles (Ag0NPs) themselves, or to the Ag+ ions released through oxidative dissolution of AgNPs in biological aqueous environments, as described by the following chemical processes [31]:

4Ag + O2 → 2Ag2O

2Ag2O + 4H+ → 4 Ag+ + 2H2O

Several studies suggest that silver ions (Ag+) are responsible for the cytotoxic effects of AgNPs, as their bactericidal activity is significantly reduced under anaerobic conditions. Consequently, the role of AgNPs would be only that of a reservoir releasing Ag+ ions that exert the observed antibacterial effects [32,33,34,35]. In vivo, AgNPs might release Ag+ ions by interaction with H2O2 [36,37].

The kinetics of ion release—and the resulting antibacterial activity—strongly depend on physicochemical features of AgNPs, such as morphology (size, shape, and crystallinity), surface functionalization, and charge [35,38,39].

Smaller nanoparticles dissolve faster than larger ones, thereby releasing more Ag+, resulting in greater antibacterial activity [38]. Several methods are available today for producing AgNPs with controlled dimensions. Wu et al., synthesized AgNPs by reducing AgNO3 with NaBH4 in the presence of citric acid (CA) as a capping agent. By adjusting the pH of the reaction medium, they produced nanoparticles of different sizes: 2 nm at pH 11, 12 nm at pH 9, and 32 nm at pH 7 [40]. Green-synthesized AgNPs were obtained by Skandalis and co-workers [41] using a phenolic- and flavonoid–rich aqueous extract of the plant Arbutus unedo as both reducing and stabilizing agent. They obtained AgNPs of two different sizes (40 nm and 58 nm) by tuning the amount of the fresh leaf extract used in the synthesis. In a similar approach, Balu et al. [42] reported the synthesis of AgNPs using an extract from Rosa indica petals as a reducing and stabilizing agent. They investigated the influence of the extraction solvent on nanoparticle size and found that acetone and ethanol extracts produced AgNPs of approximately 12 nm and 18 nm, respectively, whereas water as the solvent resulted in significantly larger nanoparticles, around 700 nm.

Differently, Hileuskaya and co-workers [43] used three types of pectin polysaccharides—high-methoxyl (PectHM), low-methoxyl (PectLM), and amidated low-methoxyl (PectA)—to synthesize spherical AgNPs coated with a stabilizing pectin shell. The nanoparticle diameter varied depending on the degree of pectin esterification and the presence of specific functional groups. TEM micrographs of high- and low-methoxyl pectin-capped nanoparticles showed sizes in the 8–13 nm range, whereas the amidated low-methoxyl pectin–Ag nanocomposite exhibited a larger average diameter of 28 ± 7 nm. Ji et al. [44] synthesized AgNPs capped with a thermo-responsive copolymer of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) and 5-(2-methacryloylethoxymethyl)-8-hydroxyquinoline (MQ), denoted as p(NIPAM-co-MQ), by reducing silver nitrate with sodium borohydride in the presence of the copolymer. By varying the molar ratio of the copolymer to the Ag precursor, they were able to control the nanoparticle size, producing three samples with average diameters of approximately 3.91 nm, 2.29 nm, and 1.59 nm, respectively. The larger the above ratio, the smaller the size of the obtained AgNPs and the narrower the size distribution of AgNPs. The AgNPs with a higher content of thermo-responsive copolymer and smaller particle size exhibited the most potent antibacterial activity against kanamycin-resistant Escherichia coli at 28 °C—below the copolymer’s lower critical solution temperature (LCST), where the polymer shell remains in a hydrophilic, swollen state. At this temperature, 1.59 nm AgNPs stabilized by the copolymer completely inhibited E. coli growth within 72 h at a concentration of 16.2 μg/mL. However, when the temperature increased to 37 °C, the antibacterial activity pattern reversed: the largest nanoparticles with the lowest content of the thermo-responsive copolymer became the most effective. This shift was attributed to the temperature-induced hydrophobic collapse of the copolymer shell, which reduced bacterial contact and hindered silver ion release [44], nicely illustrating the impact of AgNPs’ surface properties on their antibacterial performance.

Surface charge also plays a critical role. Hadari et al. [45] synthesized ultrasmall AgNPs (<3 nm) functionalized with the polycationic polymer chitosan and compared their antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities to those of identically sized AgNPs with a negatively charged surface. The chitosan-coated AgNPs exhibited superior performance in both antibacterial and antibiofilm tests. To demonstrate the effect of surface functionalization on Ag+ ion release rate, Kittler et al. [46] investigated the oxidative dissolution of AgNPs capped with either citrate or polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in aqueous suspension at various temperatures. They found that the uncharged, PVP-functionalized AgNPs had a higher dissolution rate than the negatively charged citrate-coated AgNPs, because the latter’s surface charge acted as a barrier to silver cation release. Additionally, the release rate increased with temperature, consistent with the rise in kinetic energy.

In addition to size, the shape of nanoparticles can influence their antibacterial activity by affecting surface energy, surface area, and, thereby, the degree of contact with the bacterial cell membrane and surface charge distribution [38]. Currently, several synthetic methods for non-spherical AgNPs are available, including chemical and bio-based syntheses [38,47,48]. Hong and co-workers prepared AgNPs in the form of nanospheres, nanocubes, and nanowires by microwave-assisted reduction of AgNO3 with ethylene glycol in the presence of PVP and varying amounts of NaCl [49]. The antibacterial activity of the differently shaped AgNPs against E. coli was evaluated using optical density (OD) measurements, growth curve analysis, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays. Nanocubes exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity, followed by nanospheres and nanowires [49]. TEM analysis revealed that nanocubes and nanospheres had closer contact with the bacterial surface compared to nanowires. The enhanced antibacterial activity of nanocubes relative to nanospheres was attributed to differences in the surface energy of their crystal facets. Nanocubes have higher surface energy, leading to greater reactivity. Goyal et al. [50] synthesized anisotropic, plate-like AgNPs of identical size but with different edge morphologies—sharp versus rounded—and compared their antibacterial activity. They found that the sharper-edged nanoparticles exhibited higher antibacterial activity than those with round corners. This enhancement was attributed to the higher charge density at sharp corners. A higher charge density renders AgNPs more able to disrupt bacterial cell membrane permeability [50]. Another nice example of morphological influences on antibacterial activity was provided by Seyedpour and co-workers [51]. They synthesized, characterized, and studied the antibacterial activity of supramolecular self-assembled coordination polymers obtained by stirring at room temperature an aqueous solution of AgNO3 with a previously sonicated ethanolic solution of three different imidazole ligands, namely imidazole, 2-methylimidazole, and benzimidazole. The morphology of the resulting nanocrystalline coordination polymers, denoted as Ag-Imid, Ag-2-Imid, and Ag-Benz, respectively, was investigated by TEM analysis, which revealed an organic ligand-dependent morphology: octahedral and hexagonal sheets for Ag-2-Imid and Ag-Imid, respectively, and nanoribbons for Ag-Benz. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed that the silver content in the three hybrid nanostructures decreased in the following order: Ag-2Imid > Ag-Imid > Ag-Benz. This trend also matched the decreasing antibacterial activity observed against E. coli and Bacillus subtilis, as determined using a cell staining assay with the propidium iodide (PI)/SYTO9 fluorescent dye kit. The authors conclude that the above antibacterial efficiency order was determined by the silver concentration and specific nanocrystal structure [51].

The above-presented effects of the physicochemical characteristics of various types of AgNPs on their antimicrobial efficacy are summarized in the tables below. Specifically, Table 1 emphasizes the differences in antibacterial activity depending on AgNP size; Table 2 highlights the effects on NP shape; and Table 3 overviews the effects of surface functionalization and charge.

Table 1.

The effects of AgNPs’ size on their antibacterial activity.

Table 2.

The effects of AgNPs’ shape on their antibacterial activity.

Table 3.

The effects of AgNPs’ surface functionalization and charge on their antibacterial activity.

2.1.2. Disruption of Bacterial Cell Membrane

A well-documented cytotoxic effect of silver-based nanomaterials on pathogenic bacteria is their ability to disrupt the integrity of the cell membrane barrier, thereby altering its permeability. In addition to its protective function, the bacterial cell membrane also serves as the site of key metabolic pathways, including the electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation. The attachment of metal nanoparticles to bacterial cell membranes is driven by various intermolecular forces, such as electrostatic attractions, van der Waals forces, receptor–ligand interactions, and hydrophobic effects [29,52,53,54].

The denaturing action of metallic nanoparticles and metallic ions on the cell membrane begins as soon as they attach to the bacterial surface. Several microscopy techniques demonstrated that even brief contact with AgNPs can cause severe damage to the bacterial cell wall, leading to the formation of dense pits [55,56,57,58,59,60]. Comparative transmission and scanning electron microscopy (TEM and SEM) images of AgNPs-exposed and untreated bacterial cells revealed striking morphological differences in the cell wall. In AgNPs-treated cells, large disruptions, irregular pits, and apparent leakage of cytoplasmic content were observed. In sharp contrast, untreated cells displayed smooth, intact cell walls and a homogeneous distribution of cytoplasmic material [60]. Altered permeability of the bacterial cell wall and membrane disrupts the cell’s ability to regulate its internal environment, leading to lysis and eventual cell death.

Both positively charged AgNPs and their released Ag+ ions easily interact with the sulfhydryl groups of proteins in the bacterial cell wall and membrane [61,62,63] as well as with the phosphate groups in the phospholipid bilayer forming complexes that disrupt the structural integrity of the cell membrane leading to increased permeability, enhanced uptake of toxic substances like antibiotics, and leakage of vital ions like H+ and K+. Protons from the extracellular environment enter the cell through damaged or permeabilized membrane regions, and this uncontrolled influx of H+ dissipates the proton gradient across the membrane (the proton motive force, PMF). As a result, the exergonic electron transport chain (ETC) becomes uncoupled from oxidative phosphorylation, since protons leak across the membrane without passing through ATP synthase. This deprives the endergonic ATP synthesis process of its energy source, leading to rapid depletion of cellular ATP levels, which in turn impairs other bacterial defence mechanisms, such as efflux pumps [64].

By embedding into the cell membrane, AgNPs disrupt lipid packing and create pores, allowing the extracellular leakage of intracellular K+ and leading to the collapse of the electrochemical gradient across the membrane. As a result, the membrane potential drops, the membrane becomes depolarized, and the electric double layer surrounding the negatively charged bacterial surface shrinks. The zeta potential decreases [65], and all these changes are associated with increased membrane permeability and a diminished ability of the cell to regulate ion transport into and out of the cell. Consequently, the delicate and vital electrochemical balance that cells maintain across their membranes is disrupted. Moreover, AgNPs and silver ions interact with membrane-bound proteins of the ETC [66,67,68], forming disruptive complexes that denature and inhibit key enzymes such as cytochrome c oxidase and succinate dehydrogenase. These interactions also impair the function of coupled proton pumps, as do membrane ATPases. As a result, the bacterial cell loses its ability to restore membrane potential, and its energetic metabolism is disrupted as well. In addition, AgNPs’ interaction with the ETC promotes excess production of ROS, which, in turn, initiates lipid peroxidation, further damaging the cell membrane.

Antibacterial activity is also dependent on the bacterial cell wall and cell membrane characteristics. In general, Gram-negative bacteria are more susceptible to AgNPs than Gram-positive bacteria, a difference attributed to structural differences in their cell wall composition. The cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria consists of an inner phospholipid bilayer (the plasma membrane), a thin intermediate peptidoglycan layer approximately 8 nm thick, and an outer phospholipid membrane containing numerous porin channels. This outer membrane is further coated with a 1–3 μm thick layer of negatively charged lipopolysaccharides (LPS). In contrast, the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria lacks an outer membrane and, consequently, does not possess an LPS coating. Instead, it features a much thicker peptidoglycan layer (over 80 nm) enriched with covalently bound, negatively charged teichoic and teichuronic acids [69]. This thick, porin-free layer is thought to act as a barrier that sequesters positively charged AgNPs through strong electrostatic interactions. In Gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane contains a negatively charged LPS layer that attracts AgNPs, while the abundant, water-filled porin channels facilitate the entry of hydrophilic species such as Ag+ ions and ultrasmall AgNPs [70,71]. Although larger AgNPs cannot pass through the porins, their accumulation on the membrane surface can disrupt membrane integrity and generate larger pores, eventually allowing them to enter the cell, as previously discussed. The involvement of porins in Ag+ ion transport [72] was demonstrated by the finding that E. coli expressing mutated porin proteins is less susceptible to silver ions, as shown by Li [73] and Radzig [74]. E. coli mutant strains deficient in OmpF or OmpC porins were 4–8 times more resistant to AgNPs when compared to the wild strain [74].

2.1.3. Effects of AgNPs on Bacterial Proteins

AgNPs denature bacterial cell membrane proteins, including ETC enzymes, and intracellular proteins involved in key metabolic pathways, ultimately leading to cell damage and death. Electrophilic silver deactivates important transmembrane enzymes underlying cellular energy generation and ion transport by forming stable S-Ag bonds with the nucleophilic thiol groups of the cysteine residues in those proteins. Silver catalyses the formation of disulfide bridges in the reaction of cellular oxygen with thiol groups, thereby altering the native three-dimensional structure of cellular enzymes and disturbing their function. Denaturation of respiratory enzymes halts ATP production [75].

The expression of key proteins and enzymes—including the 30S ribosomal subunit protein S2, succinyl-CoA synthetase, the maltose transporter MalK, and fructose bisphosphate aldolase—was altered in cells treated with a 900 ppb Ag+ solution [76,77,78,79]. These findings can be explained as follows: silver ion–induced downregulation of ribosomal protein S2 destabilizes the ribosome, impairing translation and protein synthesis. This disruption ultimately leads to cell death by suppressing key biosynthetic steps catalysed by essential metabolic enzymes, such as fructose bisphosphate aldolase in glycolysis and succinyl-CoA synthetase in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Both pathways are critical for ATP production in E. coli [79].

AgNP-induced disruption of the proton gradient, membrane potential, and proton motive force (PMF) inhibits the activity of bacterial efflux pumps, which are responsible for expelling antibiotics from the cell. Efflux pumps, along with other adaptive defence mechanisms, contribute significantly to the widespread emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR) in bacteria. These pumps are transmembrane transport proteins, and at least six distinct types have been identified in bacteria. Among them is one ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, which is directly powered by ATP hydrolysis, and five secondary active transporters that utilize the electrochemical gradient across the membrane as their energy source [80]. Using an ethidium bromide (EtBr) accumulation assay, Behdad et al. measured the MIC of EtBr in MDR Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates treated with AgNPs synthesized via the reduction of AgNO3 using an ethanolic leaf extract of Acroptilon repens. Compared to untreated cultures, the MIC values of EtBr were two to four times lower in the AgNP-treated cultures, indicating that the synthesized AgNPs inhibited efflux pump activity [81]. Moreover, using quantitative real-time PCR, the authors showed that, in isolates carrying efflux pump genes, expression levels of these genes were significantly reduced following treatment with sub-MICs of AgNPs [81] AgNPs by reducing AgNO3 with NaBH4 in the presence of glutamic acid and subsequently functionalized them by grafting with thiosemicarbazide (TSC). The resulting Ag-TSC-conjugated nanoparticles were evaluated for their ability to downregulate the expression of the MexA and MexB efflux pump genes in ciprofloxacin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Using quantitative PCR, the authors found that strains exposed to both Ag-TSC NPs and ciprofloxacin showed 6.0-fold and 2.75-fold reductions in MexA and MexB expression, respectively, compared with control strains treated with ciprofloxacin alone [82]. Similar results were reported by Madhi et al., who showed that expression of the efflux pumps AdeB in A. baumannii and MexB in P. aeruginosa decreased after exposure to AgNPs loaded with antibiotics [83,84].

2.1.4. Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species

One proposed explanation for the strong bactericidal effect of Ag+ is that silver ions bind to low redox-potential enzymes in the bacterial respiratory chain, impeding efficient electron flow to the terminal oxidoreductase, thereby leading to overproduction of ROS and increased oxidative stress [66]. It should be noted that ROS are not inherently harmful; they are produced at physiological levels as a normal consequence of aerobic metabolism and play essential roles in redox signalling. However, when ROS production exceeds the cell’s antioxidant capacity, they become toxic. Cells possess defence mechanisms to maintain ROS within safe physiological limits. Two antioxidant enzymes act as ROS scavengers: superoxide dismutase (SOD) transforms the superoxide radical anion into hydrogen peroxide, while catalase (CAT) converts hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. Oxidative stress occurs when this balance is disrupted, with ROS levels overcoming the cell’s ability to neutralize them. For instance, elevated levels of hydrogen peroxide damage biomolecules and trigger an inflammatory response.

ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide radical anion, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and hypochlorous acid are highly reactive and attack and damage key biomolecules, including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, as well as critical cellular structures such as the cell membrane and ribosomes [75]. Chemical transformations of targeted biomolecules, such as lipid peroxidation, oxidative carbonylation of proteins, oxidative alteration of DNA bases, and strand excision, severely harm bacteria by disrupting membranes, inhibiting enzymes, and damaging DNA. These alterations can ultimately trigger mutations, metabolic failure, and cell death via apoptosis or necrosis.

In addition to its destructive effect on cell membranes, lipid peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) ultimately produces toxic metabolites that contribute to oxidative stress and genotoxicity. Notable examples include malondialdehyde (MDA), the end product of arachidonic acid peroxidation, and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which originates from linoleic acid. These aldehydic products further promote protein carbonylation and oxidative modifications of DNA bases, potentially leading to mutations. Hydroxyl radicals and other ROSs generated during normal metabolism and inflammation attack deoxyribose sugar and possibly nucleobases in DNA, generating several electrophilic products with genotoxic potential [85,86,87]. For instance, 4′-hydrogen atom abstraction on the deoxyribose moiety by hydroxyl radicals or other activated oxygen species leads to the formation of base propenals. On the other hand, malondialdehyde, a major product of lipid peroxidation, reacts with bases in DNA to form several adducts, the most prominent being M1dG (pyrimidopurinone adduct of deoxyguanosine), which is known to be mutagenic. Because base propenals are structural analogues of malondialdehyde, Dedon et al. [85] investigated whether base propenals could also form M1dG adducts. They confirmed this hypothesis, showing that 9-(3-oxoprop-1-enyl)adenine (adenine-propenal) reacts with DNA to form the M1dG adduct even more efficiently than malondialdehyde itself. Thus, oxidative DNA damage—whether directly caused by ROS or indirectly via lipid peroxidation products such as MDA and 4-HNE—contributes significantly to the mutagenic burden in bacterial cells. Similarly, elevated ROS levels can lead to protein carbonylation, either directly—through the oxidation of amino acid side chains such as proline, arginine, lysine, and threonine—or indirectly, via reactive lipid peroxidation end products [88].

AgNPs may increase ROS levels in bacteria by inactivating the detoxifying enzymes SOD and CAT [89].

2.1.5. Interaction with DNA

Studies on E. coli have shown that exposure to AgNPs can cause DNA strand breaks and potentially induce mutations in critical DNA repair genes. One of the most common oxidative DNA lesions is the formation of 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) [87]. Radzig et al., investigated how mutations in genes of the base excision repair (BER) system affect E. coli susceptibility to AgNPs. The MutM DNA glycosylase repairs 8-oxoG lesions by excising the oxidized purine base, while MutY and MutS remove adenine residues that were erroneously incorporated opposite to 8-oxoG. MutT, on the other hand, prevents incorporation of oxidized nucleotides by hydrolytically removing 8-oxodGTP from the nucleotide pool. The study found that E. coli strains deficient in these repair genes were 2- to 10-fold more susceptible to AgNO3 exposure, depending on the specific mutation. These findings indicate that the BER pathway plays a critical role in repairing oxidative DNA damage and suggest that the genotoxic effects of AgNPs may overwhelm or compromise this repair system in susceptible E. coli strains [74,75,90,91].

AgNPs can induce a transition of DNA from its relaxed state to a condensed state, thereby preventing replication or suppressing the transcription of some genes [74,75,92]. Ag+ ions released from AgNPs intercalate between base pairs, disrupting hydrogen bonding and forming coordination complexes with the nitrogen and oxygen atoms in nucleobases, rather than binding to phosphate groups. At the G≡C base pair, linear bidentate coordination complexes such as O-Ag+-N, N-Ag+-N, and N-Ag+-O can form. Similarly, N-Ag+-O, and N-Ag+-N complexes may appear at A=T pairs loci [93].

2.1.6. Antibiofilm Activity

Biofilms are complex and dynamic sessile bacterial communities composed of single or multiple strains embedded in a sheltering self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. The EPS consists primarily of water, polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, ions, and various inorganic substances. It plays multiple roles: facilitating intercellular signalling, promoting horizontal gene transfer—both of which are critical for the MDR development—and forming a physical barrier that protects bacteria within the biofilm from variations in osmotic potential and pH fluctuations, while also limiting the penetration of antibiotics and host immune cells, thereby helping the bacteria evade phagocytic clearance [94]. A striking feature of biofilms compared to planktonic bacteria is their remarkable resistance to antibiotic treatment, often leading to recurrent infections [94,95,96]. A biofilm’s life cycle progresses through four sequential stages: initial attachment to a biotic or abiotic surface, proliferation, maturation, and, eventually, dispersion and migration to new sites to be colonized, thereby restarting the cycle. A mature biofilm typically contains a heterogeneous population of bacterial cells, including sessile (attached) cells, free-floating (planktonic) cells, persister dormant (antibiotic-tolerant) cells, and dead cells. These coexist within the EPS matrix, along with signalling molecules and structured water channels [97].

AgNPs exert their antibiofilm activity by interacting with the protein, nucleic acid, polysaccharide, and lipid components of the EPS. Tian et al. provided evidence supporting the hypothesis that AgNPs suppress biofilm formation by interacting with small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) and altering RNA expression [98,99]. Small regulatory RNAs are short, noncoding RNAs that modulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. In bacteria, each sRNA typically contains two functional regions: a target-binding sequence, which hybridizes with a complementary region of the target messenger RNA (mRNA) in an antisense manner, and a scaffold sequence. The scaffold serves dual functions: it stabilizes the sRNA by recruiting the RNA chaperone protein Hfq, which in turn accelerates annealing to the targeted mRNA. Annealing can result in either positive or negative regulation of translation. Positive regulation may result from the remodelling of inhibitory RNA structures or from blocking the binding of negative regulatory elements. In contrast, negative regulation involves inhibition of translation initiation, recruitment of RNases for mRNA degradation, or both. One mechanism of negative regulation engages sRNA binding to the 5′ translation initiation region (TIR) of the target mRNA, typically near the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence. This interaction blocks the base pairing between the SD sequence and the anti-SD sequence of the 16S ribosomal RNA within the small ribosomal subunit, thereby impeding proper ribosome assembly and translation initiation. As a result, expression of the target genes is post-transcriptionally repressed [100,101]. AgNPs may exert their antibiofilm effects either by downregulating sRNAs that normally promote biofilm formation or by upregulating sRNAs that repress biofilm-related genes.

Biofilm formation is closely linked to quorum sensing (QS), a mechanism by which bacteria regulate gene expression in response to cell population density within the biofilm lifestyle. QS is a cell-to-cell communication mechanism. Bacteria produce, release, and sense chemical signalling molecules called autoinducers (AIs). When the concentration of AIs exceeds a specific threshold, it serves as a signal that triggers changes in bacterial gene expression. Reaching this threshold depends on the bacterial population density—hence the term quorum is used to describe the phenomenon. When AIs accumulate to sufficient concentrations, they are detected by specific receptors located in the bacterial cytoplasm or plasma membrane. The binding of these signalling molecules to their receptors activates intracellular signalling cascades, ultimately leading to changes in gene expression, including the synthesis of adherence molecules, EPS matrix, and virulence factors. Detection of AIs also promotes the expression of genes involved in cooperative bacterial behaviours associated with the biofilm lifestyle. In addition, it upregulates the synthesis of autoinducers themselves through a positive feedback loop. It is important to note that biofilms function as coordinated communities, responding collectively to environmental stimuli rather than behaving as isolated individual cells [94,102]. As a result, bacteria in biofilms gain a competitive advantage in survival and spread compared to their planktonic counterparts. AgNPs can interact with amino acid residues in the binding domains of receptor proteins—such as members of the LuxR family in the QS regulatory cascade—or inhibit AHL synthases responsible for producing acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) autoinducers in Gram-negative bacteria, thereby disrupting cell-to-cell communication and downstream signalling pathways.

Two main types of polysaccharides are associated with bacterial biofilms: structural polysaccharides that are part of the cell envelope, and EPS polysaccharides, each serving distinct roles in bacterial survival and biofilm development. Cell envelope–associated polysaccharides, such as those in the LPS layer and the capsular polysaccharide (CPS) shell, not only provide mechanical strength and structural stability but are also involved in osmoregulation, contribute to virulence, and protect bacteria from host immune responses and antimicrobial killing [103]. In contrast, EPS polysaccharides are secreted into the ECM and play key roles in maintaining biofilm integrity, protecting against environmental stress, preserving nutrient availability, and promoting intercellular interactions within the microbial community [102]. The interaction of AgNPs with both structural and extracellular polysaccharides, mainly driven by electrostatic forces, enhances their antibacterial activity and disrupts the protective function of the biofilm matrix [102].

In summary, AgNPs appear to act against pathogenic biofilms through mechanisms similar to those by which they affect free-floating (planktonic) bacteria. However, their specific effects on persister cells within the biofilm community remain to be elucidated.

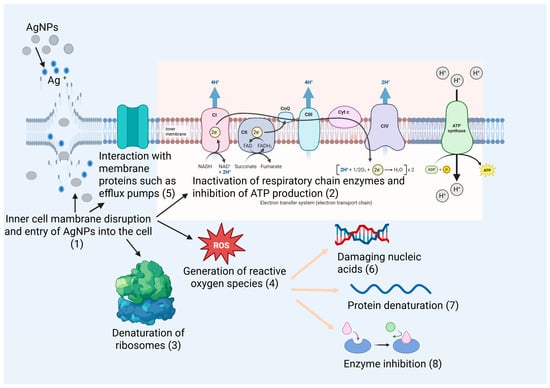

The main antibacterial mechanisms of AgNPs are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Antibacterial mechanisms of AgNPs. The main molecular targets of AgNPs and Ag+, along with the resulting cellular effects, are indicated in the figure by numbers (1–8).

2.1.7. Comparison of the Antibacterial Activity of Antibiotics and AgNPs

The non-specific antibacterial activity of AgNPs offers a significant advantage over conventional antibiotics in combating multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, which typically act through highly specific mechanisms targeting only one or, at most, a few key molecular or cellular structures (as summarized in Table 4). Although antibiotics may influence multiple biological pathways, their primary mode of action remains narrowly focused [104]. In contrast, AgNPs exert multiple simultaneous damaging effects on bacterial cells, making it more difficult for bacteria to develop effective resistance mechanisms. However, scientific evidence also shows that prolonged exposure to silver-based nanomaterials is detrimental, as it can promote the development of bacterial tolerance to AgNPs. This issue will be further discussed in the section addressing toxicity and safety concerns.

Table 4.

Antibiotic targets and mechanisms of action [104].

2.2. The Role of Silver Nanoparticles in Modulating Inflammation and Promoting Wound Healing

2.2.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Beyond their antibacterial effects, AgNPs’ potent anti-inflammatory properties are particularly important for mitigating excessive inflammation and supporting tissue repair. The oxidative dissolution of AgNPs leads to the release of Ag+ ions and the generation of ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). At moderate levels, these ROS can inhibit the NF-κB signalling pathway, thereby reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, including tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [105,106]. In addition, AgNPs interfere with intracellular signalling pathways involving key kinase proteins, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (ERK, JNK, p38) and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway. Through these interactions, AgNPs help regulate oxidative stress by reducing levels of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), thereby attenuating inflammatory responses.

The anti-inflammatory effects of AgNPs have been demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo studies. Jalil et al. [107] showed, using a murine carrageenan-induced hind paw edema model, that both AgNPs and Ag-amoxicillin nanoconjugates exhibited superior anti-inflammatory efficacy compared to conventional treatments such as diclofenac and high-dose amoxicillin. Five hours after administration at a dose of 10 mg/kg, the inflammation inhibition rates were 64% for AgNPs and 65% for Ag-amoxicillin, whereas diclofenac—administered at a twofold higher dose of 20 mg/kg—achieved only 56% inhibition. However, diclofenac exhibited stronger anti-inflammatory effects during the acute phase (1–3 h post-induction). In this early stage, AgNPs are thought to inhibit mast cell degranulation and reduce the release of vasoactive compounds, thereby decreasing capillary permeability. In the later phase, they are believed to target COX–2–catalyzed prostaglandin synthesis, thereby mitigating inflammation. Moldovan et al. [108] synthesized AgNPs using a green biosynthetic method, in which Viburnum opulus L. fruit extract—rich in polyphenols—served as the reducing agent for AgNO3. The anti-inflammatory properties of these AgNPs were evaluated both in vitro, using UVB-irradiated HaCaT keratinocyte cultures, and in vivo, via a carrageenan-induced paw edema model in Wistar rats. In the in vitro experiments, the authors measured the secretion levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-6 in cell culture supernatants. HaCaT cells were pretreated with AgNPs for 30 min and subsequently exposed to UVB irradiation at a dose corresponding to the IC50 (i.e., the dose reducing cell viability by 50%). Following UVB exposure, the cells received a fresh dose of AgNPs and were incubated for either 24 or 48 h. Supernatants collected at these time points were analysed for cytokine content and compared with non-treated controls. The results showed that phytosynthesized AgNPs induced a transient increase in IL-1α secretion in UVB-irradiated keratinocytes at 24 h, whereas at 48 h IL-1α levels decreased relative to UVB-only treated cells. In contrast, IL-6 secretion was consistently reduced at both time points in AgNP-treated, UVB-exposed keratinocytes. In the in vivo model, rats received a daily oral dose of 0.3 mg AgNPs/kg body weight for 4 consecutive days prior to inflammation induction. This pre-treatment produced an early anti-inflammatory effect, evidenced by reduced cytokine levels (including TNF-α) in hind paw tissue homogenates and decreased paw edema observed two hours after carrageenan injection. Overall, these findings suggest that phytosynthesized AgNPs exhibit rapid and effective anti-inflammatory activity in both in vitro and in vivo experimental systems. Singh et al. [109] demonstrated that green-synthesized AgNPs prepared from Prunus serrulata fruit extract reduced the expression of key inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), COX-2, iNOS, and NO. They also observed significant nanoparticle-mediated suppression of LPS-induced NF-κB signaling pathway activation via p38 MAPK in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Similarly, Crisan et al. [110] reported inhibition of NF-κB transcription factor activity by topical AgNPs complexed with a polyphenol-rich Cornus mas extract in human psoriasis plaques.

In addition, recent studies indicate that AgNP-containing biomaterials can directly influence macrophage polarization. AgNPs and AgNP-loaded hydrogels have been shown to suppress macrophages M1-associated markers while upregulating macrophages M2-associated markers, thereby promoting a phenotypic shift that aligns with the resolution of inflammation and initiation of tissue repair [111,112]. This immunoregulatory effect has emerged as an important mechanism contributing to the accelerated healing observed in AgNP-treated wounds.

2.2.2. Effects on Cell Proliferation and Migration

Robust wound closure relies on the proliferation and directed migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes. The effects of AgNPs on these processes depend on their concentration and surface functionalization.

Low concentrations of AgNPs release trace Ag+ levels that stimulate fibroblast proliferation and aid wound closure, while simultaneously providing antibacterial protection. In contrast, high AgNP concentrations lead to excessive ion release, causing cytotoxicity through damage to proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. In an in vitro study on mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Du et al. [113] reported that 16 µM AgNPs stimulated cell proliferation, corroborating the findings of Xu et al. [114], who observed that AgNPs significantly promoted fibroblast proliferation and enhanced wound healing.

Surface functionalization with bioactive molecules can markedly enhance wound healing performance. Long et al. [115] developed a composite sponge incorporating AgNPs decorated with recombinant humanized collagen type III (rhCol III), which exhibited superior haemostatic, wound-repairing, and antimicrobial properties. The porous three-dimensional (3D) shape-memory sponge was constructed from the naturally antibacterial polymer carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC), crosslinked via Schiff base linkages with oxidized starch (OS), and further reinforced by microfibrillated cellulose (MFC). AgNPs were generated in situ within the polymeric matrix by reducing AgNO3 with tannic acid (TA). In brief, TA was added under stirring to a CMC solution containing the silver precursor. The CMC/OS–MFC sponge was prepared via a two-step protocol consisting of a sol–gel process followed by freeze-drying. First, an MFC suspension was added to the AgNP-containing CMC solution, followed by sequential addition of OS to induce crosslinking, and finally rhCol III, which formed hydrogen bonds with the MFC. The resulting hydrogel was freeze-dried to produce a compressible, biodegradable sponge that could be delivered via syringe injection, enabling treatment of narrow and deep wounds. The sponges’ ability to promote cell proliferation and migration was assessed in vitro using a scratch assay. After 48 h of incubation, the wound closure rate in the rhCol III/AgNP sponge group reached 77.3%, compared with 43.4% for sponges containing AgNPs alone. Additionally, an in vivo diabetic rat full-thickness skin wound model infected with bacteria was used to evaluate wound repair efficacy. Rats treated with rhCol III/AgNP-decorated sponges achieved complete wound closure within 14 days, whereas control groups still exhibited a residual wound area of approximately 17% of the original size at the same time point [115].

Gaikwad et al. [116] formulated three nanogels by incorporating AgNPs mycosynthesized from Fusarium oxysporum into Carbopol at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mg g−1, and evaluated them in vivo in albino Wistar rats. All three silver nanogels demonstrated pronounced effects on cell proliferation and wound healing in incision, excision, and burn wound models. The 0.1 mg g−1 AgNP nanogel showed the most notable wound-healing activity in excision wounds, whereas the 1 mg g−1 formulation achieved superior outcomes in burn wound care. Histological examination of the healed tissues revealed no signs of toxicity or adverse effects. Lower-concentration nanogels also promoted wound healing and hair follicle regeneration.

Liu et al. [117] investigated the effects of AgNPs on keratinocytes and fibroblasts using a surgical wound model on murine dorsal skin. Wound healing involves two key processes: re-epithelialization and wound contraction. Re-epithelialization is a complex, multistep process driven by keratinocyte migration and proliferation in the epidermal layer. Wound contraction, which minimizes the open wound area, involves pulling the surrounding tissue toward the wound center and occurs primarily in the dermal layer, driven by α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) produced by myofibroblasts. In infection-free clean wounds, wound closure occurred significantly faster in animals treated with AgNPs compared to those receiving the standard 1% silver sulfadiazine (SSD) cream. To examine the effects of AgNPs on each cell type separately, keratinocytes and fibroblasts were isolated and cultured ex vivo. AgNP treatment produced a marked increase in keratinocyte proliferation relative to control, and this effect persisted for up to 7 days, thereby accelerating re-epithelialization. Conversely, fibroblast cultures exhibited a reduction in cell numbers. This decrease was not due to AgNP cytotoxicity, as the 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay showed that at concentrations below 100 μM, AgNPs were relatively non-toxic to fibroblasts. However, AgNP-treated fibroblasts showed significantly reduced collagen and hydroxyproline production in the culture supernatants, suggesting that AgNPs altered the normal fibroblast phenotype. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining confirmed that the apparent inhibition of fibroblast proliferation was due to AgNP-induced maturation and differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, as evidenced by significantly elevated α-SMA expression, which contributed to accelerated wound contraction.

2.2.3. Pro-Angiogenic Effects

The proliferative phase of wound healing involves not only fibroblast migration and wound closure but also angiogenesis and neovascularization. These processes can be influenced by the size, surface functionalization, and concentration of AgNPs. AgNPs have been shown to promote angiogenesis by upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), as well as activating the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway.

Zhang et al. [118] developed an innovative nanoplatform based on nano-hydroxyapatite (nHEA) to address the challenges posed by inadequate regulation of multiple stages in the wound-healing cascade. This multifunctional system, designed for the treatment of full-thickness infected skin injuries, enabled multi-level therapeutic regulation by covalently incorporating ε-poly-L-lysine–grafted gallic acid (EG) and in situ biosynthesized AgNPs into a multilayered nHEA structure. EG was synthesized from ε-poly-L-lysine (EPL) and gallic acid (GA) via 3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC)-mediated amide bond formation. The reaction mixture was then dialyzed and freeze-dried to yield an EG sponge. Sodium hyaluronate (HA) was oxidized with NaIO4 to obtain oxidized HA (OHA). Separately, nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) was surface-functionalized with amino groups by sequential treatment with acidic tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) solution and aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), and then covalently conjugated to OHA through Schiff base formation. To the resulting precipitate, EG and Ag+ solutions of varying concentrations were added. The mixture was shaken and centrifuged, producing the final nHEA nanoplatform. In infected rat wounds, the release of EG enhanced fibroblast migration and collagen secretion, while the release of Ag+ and Ca2+ provided synergistic antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and pro-angiogenic effects, the latter through VEGF upregulation. The in vivo efficacy of the nHEA platform was assessed in a full-thickness infected skin defect model in Sprague–Dawley rats. After 7 days of treatment, rats receiving the nHEA nanoplatform showed markedly improved wound healing compared with controls, as evidenced by smaller residual wound areas and lower infection levels.

Mensah et al. [119] incorporated both commercially produced and green-synthesized AgNPs into the network of eggshell membranes (ESM)—a biomaterial with unique physical and mechanical properties—by submerging the ESM in a suspension of ~10 nm AgNPs for 24 h under continuous stirring at 37 °C. ESM was extracted from fresh eggs on treatment with acetic acid at room temperature for 44 h. SEM analysis of AgNPs-incorporated ESM samples revealed a uniform surface deposition of AgNPs while preserving the structural integrity of the ESM. In vitro biocompatibility was evaluated using human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) and BJ human fibroblast cells. Relative metabolic activity (cell viability) was determined with the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, and cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. The results showed that ESM samples containing 5 µg/mL AgNPs were highly biocompatible with both fibroblast cell types. Furthermore, a chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay demonstrated strong pro-angiogenic activity, with a significant increase in vascular branching points. This neovascularization provides an essential framework for the subsequent ECM remodelling phase and tissue repair during wound healing.

2.2.4. Effects on ECM Remodelling Phase

Chronic wounds are often characterized by remodelling defects caused by an imbalance between the degradation of damaged ECM components and the synthesis of new ones. Ag+ ions can promote the synthesis of key ECM constituents involved in reconstruction and remodelling, such as type III collagen and elastin, by stimulating fibroblast proliferation and migration [120]. In addition, AgNPs have been shown to inhibit overactive MMPs and upregulate the expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) [121], thereby helping to restore the balance between ECM synthesis and degradation.

Seo et al. [122] reported enhanced wound healing and muscle regeneration in a zebrafish in vivo laser-induced skin wound model. The highest wound healing percentage (WHP) was observed in the group treated with AgNPs by immersion, reaching 36.6% at five days post-wounding. By comparison, the WHP was 23.7% in the group receiving AgNPs via direct skin application, and only 18.32% in the untreated control group at the same time point. In the AgNP immersion group, pronounced aggregation of immune cells near the wound edges was observed, along with epidermal cell differentiation into well-developed skin. Muscle tissue also showed near-complete regeneration. Transcriptional analysis during the healing process revealed that AgNP treatment led to downregulation of IL-1β, TNF-α, and MMP-9/MMP-13 expression and upregulation of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD. Collectively, these effects contributed to a balanced ECM reconstruction and a reduction in both inflammation and oxidative stress.

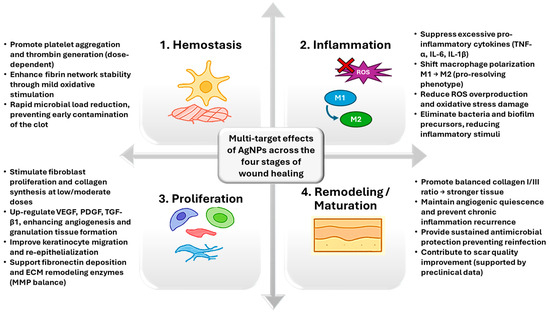

For better clarity, the most important effects of AgNPs throughout the wound healing process have been gathered in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of AgNP effects during the different wound healing stages.

3. AgNPs-Based Nanocomposite Materials for Wound Care

3.1. AgNPs-Loaded Hydrogels

Hydrogels are 3D cross-linked polymer networks that absorb large amounts of water, creating a moist and supportive environment [123]. Their ability to mimic the ECM, along with their biocompatibility, high permeability, and tunable mechanical properties, makes them ideal for wound care by providing a moist healing environment for dry, minimally exudative wounds, supporting cells, and delivering therapeutic agents. Natural polymer–based hydrogels, such as those derived from chitosan or hyaluronic acid, can be incorporated with in situ-generated AgNPs via reduction of silver salts, thereby enhancing their biocompatibility.

Raho and co-workers [124] developed a composite hydrogel composed of regenerated silk fibroin (RSF) stabilized with sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC-Na) and loaded with AgNPs. The AgNPs were generated in situ via the photoreduction of AgNO3, mediated by the redox-active tyrosine residues in Bombyx mori fibroin under UV irradiation [125,126]. Upon UV excitation, the phenolic side chains of tyrosine donate electrons to reduce Ag+ ions to metallic silver, while simultaneously stabilizing the resulting nanoparticles through coordination with protein functional groups. The composite hydrogels (CoHy) loaded with AgNPs in the 50–200 nm size range (mean size 92 nm) demonstrated a high fluid-absorption capacity, taking up 20–30 g of fluid per gram of dry material. CoHy prepared with 1 or 2 mg of crystalline AgNO3 per mL of RSF solution showed no in vitro cytotoxicity toward rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). Antimicrobial activity, assessed by agar diffusion tests, revealed clear inhibition zones against a large plethora of pathogenic microorganisms, including E. coli, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), P. aeruginosa, Candida albicans, and fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans (FRCA). Notably, CoHy without AgNPs supported high cell proliferation, underscoring the intrinsic regenerative potential of the RSF/CMC matrix. Among the tested formulations, CoHy loaded with 1 mg/mL of AgNO3 provided the optimal balance between tissue-regenerative properties, cytocompatibility, and antimicrobial activity. In a similar approach, Ruffo et al. [127] developed a biocompatible CMC-based hydrogel loaded with in situ–green-synthesized AgNPs, using an aqueous mixture of olive leaf and Camellia sinensis (green tea) dry extracts as reducing agents, for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). In diabetic patients, foot ulcers arise from neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and ischemia. When infected, these ulcers pose a serious clinical challenge, with an increased risk of progressing to gangrene and amputation due to the patient’s impaired immune response. Motivated by the need to control and treat DFUs, the authors prepared a CMC–AgNP hydrogel, which was freeze-dried to yield a flexible, porous structure. The wound-healing potential of the hydrogel was evaluated through in vitro and ex vivo assays. After 24 h of incubation, the hydrogel maintained high viability of 3T3 fibroblast cells (88%). It exhibited potent antibacterial activity against E. coli (MIC = 5.15 μg/mL), S. aureus (MIC = 30 μg/mL), and P. aeruginosa (MIC = 27 μg/mL). Safety and skin compatibility were assessed using the Human Cell Line Activation Test (h-CLAT) and the EpiDerm™ reconstructed human epidermis (RhE) assay, both of which confirmed the absence of skin sensitization or irritation. In a wound-healing scratch assay, treatment with 100 μg/mL of hydrogel resulted in 75 ± 0.3% wound closure after 24 h. Furthermore, ex vivo testing of enzyme inhibition demonstrated that the hydrogel downregulated the activity of myeloperoxidase (MPO)—an enzyme released by neutrophils that produces the potent bactericidal agent hypochlorous acid (HOCl), but which can also cause oxidative tissue damage. The hydrogel also inhibited collagenase activity, thereby supporting ECM preservation and promoting tissue regeneration [127].

Chen et al. [128] developed an injectable hydrogel derived from a decellularized dermal matrix of 6-month-old domestic swine, loaded with GA–capped silver AgNPs for the treatment of MRSA–infected wounds. The acellular dermal matrix was digested with pepsin and then acidified with hydrochloric acid to pH 2 to ensure complete digestion, yielding a homogenate. This homogenate was sequentially treated in an ice bath with pre-cooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and NaOH solutions to adjust the pH to 7.2. The resulting “pre-hydrogel” was combined under continuous stirring with a concentrated solution of GA-capped AgNPs, producing the final acellular dermal matrix hydrogel, designated Ag@ADMH. Ag@ADMH exhibited excellent biocompatibility and provided sustained release of antimicrobial AgNPs from the three-dimensional dermal scaffold. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed downregulation of iNOS expression, a marker of M1 macrophages, and increased expression of CD206, a marker of M2 macrophages. This indicated a polarization shift from the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage phenotype to the pro-healing M2 phenotype, which promotes fibroblast migration and proliferation. Such modulation supports the transition from the inflammatory to the proliferative phase of wound healing, thereby enhancing tissue repair and reducing inflammation [129].

Another type of composite hydrogel dressing based on AgNPs was developed by Zhou and co-workers [130]. First, they synthesized a water-soluble adenine-functionalized chitosan derivative (CS-A) via amidation of chitosan (CS) with 3-(9-adeninyl) propionic acid (A-COOH). The resulting CS-A sponge dressing exhibited broad-spectrum wound-healing properties, including suppression of inflammatory cell infiltration, stimulation of neovascularization—attributed to the incorporated adenine nucleotide, which can activate angiogenic factors and promote cell proliferation—enhancement of collagen deposition, and regeneration of epithelial tissue. To improve the mechanical strength and self-healing capacity of the hydrogel, the authors synthesized a star-shaped, eight-armed crosslinker through a two-step process: (i) thiol–ene click reaction between allyloxypolyethylene glycol (PEG) and thiol-functionalized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS-8SH), followed by (ii) Steglich esterification with 4-carboxybenzaldehyde [131]. The resulting eight-armed POSS-PEG-CHO crosslinker was then used to crosslink the AgNP-impregnated CS-A via Schiff base linkages formed between aldehyde (CHO) groups on the crosslinker and amino (NH2) groups on the CS-A chains. The AgNP-impregnated CS-A solution was first prepared by mixing the CS-A sponge with an aqueous AgNO3 solution at a 1:1 volume ratio, enabling in situ AgNPs formation. This AgNPs-loaded CS-A/POSS-PEG composite self-healing hydrogel demonstrated excellent cell proliferation support and significantly accelerated wound closure in infected wound models. Treated wounds displayed reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, increased collagen deposition, enhanced angiogenesis, and more rapid epithelial regeneration, as confirmed by immunofluorescence staining assays and histological analysis [130].

To address the heterogeneity among published studies and to quantitatively synthesize AgNP performance, we compiled a summary of representative AgNP-based systems tested in wound-healing–relevant models. Table 5 presents the nanoparticle size, silver concentration or dose, and the corresponding biological outcomes reported in the cited studies.

Table 5.

Overview of representative AgNP-based systems used in wound-healing–relevant models.

3.2. AgNPs-Loaded Fiber-Based Composites

Another valuable nanoplatform for wound dressings is represented by electrospun composite nanofibers. These materials offer several advantages that fulfil the main requirements of an efficient wound dressing. They can provide and maintain a moist wound environment while simultaneously absorbing excess wound exudates, which helps accelerate healing. Their intrinsic or functionalized antibacterial properties help reduce the risk of infection. Furthermore, electrospun composite nanofibers possess favourable mechanical properties that closely mimic the interwoven network of collagen and elastin fibers found in the natural ECM. This structural similarity not only reinforces the mechanical stability of the wound site but also guides the directional migration of fibroblasts along the fiber axis, thereby promoting cell adhesion, proliferation, and ultimately tissue regeneration [134,135,136,137,138,139,140]. Liu et al. [141] developed a biomimetic composite wound dressing based on electrospun nanofibrous chitosan (CS) incorporating AgNPs and curcumin (Cur), which demonstrated synergistic antibacterial and wound-healing activities. In their design, the hydroxyl groups of curcumin, encapsulated within the hydrophobic cavity of β-cyclodextrin (β-CD), served as a reducing agent for AgNO3, while β-CD simultaneously acted as a capping agent, leading to the formation of Cur@β-CD/AgNPs complexes. These complexes were then incorporated into a solution of CS dissolved in dilute acetic acid, with polyethylene glycol (PEG) added to improve spinnability and biocompatibility, yielding a 2 wt% homogeneous Cur@β-CD/AgNPs/CS/PEG solution that was subsequently electrospun. The resulting electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds exhibited a swelling ratio of 432%, highlighting their ability to maintain a moist wound environment while absorbing excess exudates. Biodegradation studies showed that the degradation rate of the scaffolds matched the pace of new tissue formation, indicating suitability for wound healing. Haemolysis and cytotoxicity assays further confirmed their excellent biocompatibility. Antibacterial activity, evaluated by zone-of-inhibition assays and optical density measurements, demonstrated that the Cur@β-CD/AgNPs/CS/PEG dressings were effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This enhanced effect was attributed to the synergistic antibacterial action of sustained curcumin release and exposed silver, surpassing the performance of conventional AgNP-based dressings. Moreover, histological analysis using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining revealed the most uniform collagen deposition in wounds treated with the Cur@β-CD/AgNPs/CS/PEG dressings compared to control groups [141]. Yang et al. [142] fabricated Janus nanofibers with two distinct “faces” using side-by-side electrospinning, a process in which two polymer solutions flow in parallel through a specially designed homemade acentric spinneret. One solution (A) consisted of PVP dissolved in a 9:1 (v/v) ethanol–acetic acid mixture and loaded with ciprofloxacin CIP) (10 wt% relative to PVP). The other solution (B) comprised ethyl cellulose (EC) dissolved in a 1:1 (v/v) ethanol–acetone mixture containing nanodispersed AgNPs. The novel PVP-CIP//EC-AgNPs Janus nanofibers exhibited markedly stronger antibacterial activity against both S. aureus and E. coli compared with conventional fiber-based wound dressings. The dual-face design enabled rapid release of >90% CIP antibiotic within 30 min, providing immediate antibacterial protection, while the EC–AgNPs side ensured sustained long-term activity [142]. Mobarakeh et al. [132] investigated the effect of co-delivering vitamins and AgNPs on wound healing. Using a co-spinning technique, they fabricated a bilayered electrospun polycaprolactone/polyvinyl alcohol (PCL/PVA) patch. To this end, they prepared two solutions (S1 and S2, respectively). S1 was obtained by dissolving PCL in a chloroform/ethanol mixture (7:3, v/v) at a final concentration of 12% w/v. The second solution, S2, was prepared by dissolving PVA in distilled water at 10% w/v, followed by the addition of specific amounts of the hydrophilic vitamins B12 and C, and mixing to ensure uniform distribution of the vitamins throughout the PVA solution. AgNPs were then dispersed into this mixture by thorough stirring. Further, the composite wound dressings were fabricated in a two-step process. First, PCL nanofibers were electrospun for 4 h. Then, a second layer was deposited by simultaneously electrospinning the PVA/vitamin/AgNP solution for 1 h. Afterward, the PCL feed was stopped, and electrospinning of the PVA solution continued for an additional 5 h. The wound-healing efficacy of the prepared dressings was evaluated in vivo using a murine model. Circular wounds were created on the dorsal skin of rats, which were divided into three groups according to the applied treatment: G0 (no wound dressing), G1 (wound dressing without vitamins and AgNPs), and G2 (wound dressing loaded with vitamins and AgNPs). The wound closure process was monitored for 14 days. Mechanical testing showed that incorporating AgNPs (G2) increased the elastic modulus compared with the control dressing (G1), indicating enhanced mechanical strength and stability under external forces. Antibacterial assays (disk diffusion method) showed significantly greater inhibition of S. aureus and E. coli by G2 than by G1. Cytotoxicity testing using the MTT assay confirmed high cell viability (>93%, p > 0.05), suggesting good biocompatibility. In vivo, G2-treated wounds showed accelerated closure, improved epithelialization, and enhanced collagen deposition, as confirmed by histological analysis [132]. Biogenic AgNPs, synthesized using curcumin as a reducing agent, were incorporated by Sarıipek [133] into a nanofibrous, biocompatible poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)/chitosan (PHB/CS) scaffold. The addition of curcumin-derived AgNPs to the PHB/CS matrix resulted in a reduction in the nanofiber diameter, enhanced hydrophilicity and wettability, and improved thermal stability. Furthermore, antibacterial activity—particularly against S. aureus—was synergistically enhanced by the combined effects of CS and AgNPs. These findings suggest that Cur-AgNP-loaded PHB/CS nanofibrous scaffolds hold promise for applications in antibacterial therapy, wound healing, and tissue engineering.

3.3. Sponge and Foam Composites Incorporating AgNPs

The porous three-dimensional architecture of sponge and foam composites enhances their ability to absorb and retain wound exudate. This property is particularly advantageous in wound healing, as effective exudate management helps maintain a moist wound environment, supporting tissue regeneration and preventing complications such as infection. These materials can absorb and hold large amounts of wound fluid within their interconnected pores, a feature especially beneficial for highly exuding wounds, where traditional dressings may fail. AgNPs can be incorporated into sponges either by blending or through in situ synthesis, performed before or during lyophilization. In the freeze-drying method used to fabricate wound sponges, a polymeric solution is first frozen to form ice crystals, which are then removed by sublimation. This process yields a porous, sponge-like structure suitable for advanced wound care. An important advantage of this technique is that it preserves the biological activity of sensitive agents such as antimicrobials or growth factors, which can subsequently be released from the porous matrix in a sustained manner [143,144]. For instance, Lu et al. [145] fabricated a sponge dressing by in situ reduction of AgNO3 within a chitosan (CS)/L-glutamic acid (L-GA) matrix containing hyaluronic acid (HA), using freeze-drying. The composite exhibited an interconnected porous structure with pore sizes of 50–200 μm and incorporated AgNPs measuring 5–20 nm, along with a rough surface morphology. The sponge displayed a liquid-absorption capacity exceeding 10 times its dry weight, underscoring its strong potential for exudate management, while its rough surface promoted fibroblast adhesion. In vitro, the dressing demonstrated effective antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus, with no cytotoxicity in L929 fibroblasts at low AgNP concentrations. In vivo studies in a rabbit model further confirmed accelerated wound healing, as evidenced by enhanced wound contraction, reduced healing time, and rapid re-epithelialization [145]. To overcome the limitation of AgNP toxicity at effective concentrations, Zhou et al. [146] developed a chitosan (CS) composite sponge dressing incorporating in situ iturin-synthesized AgNPs. Iturin is a lipopeptide with antifungal activity, composed of a cyclic heptapeptide linked to a β-amino fatty acid chain. The tyrosine residues within the cyclic peptide can reduce AgNO3 under irradiation, leading to the formation of iturin-stabilized AgNPs [147]. Using a previously reported method [148], Zhou et al. fabricated an iturin–AgNP–CS composite sponge by freeze-drying. The resulting dressing exhibited markedly enhanced antibacterial and wound-healing properties compared with commercially available AgNP-loaded dressings. In a murine full-thickness infected wound model, the composite sponge achieved effective bacterial control by day 4. Accelerated wound contraction was evident by day 7, followed by nearly complete tissue repair by day 16, with the re-epithelialization rate exceeding 90%. Histological analysis further confirmed increased formation of subcutaneous connective tissue and fibroblasts, along with pronounced neovascularization and collagen fiber deposition. Hydrogel no systemic organ toxicity was observed [146].

The primary objective in wound management is to control bleeding and achieve haemostasis, particularly in irregular, deep, non-compressible wounds, as subsequent infection can pose a serious risk to the patient’s life. Therefore, the development of new, more effective haemostatic materials is a priority. Among these, shape-memory haemostatic sponges offer important advantages: they can be easily delivered and secured in deep, small wounds through simple compression. Once in place, they absorb blood, expand to their original shape, and form a physical barrier that effectively stops further bleeding. Dong et al. developed a shape-memory composite haemostatic sponge incorporating AgNPs to provide antibacterial activity. However, a key challenge is preventing the rapid release of AgNPs, which can lead to toxic side effects. Thus, effective immobilization within the scaffold and controlled release at the wound site are essential. To address this, Dong et al. [149] constructed a hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC)/soy protein isolate (SPI) composite sponge (EHSS). The EHSS was prepared by cross-linking HEC and SPI using epichlorohydrin (ECH) [150,151]. Next, a mussel-inspired surface modification was applied to regulate the in situ–generated AgNP release. Specifically, dopamine (DA) was oxidatively polymerized under alkaline conditions, producing a polydopamine (PDA) coating on the EHSS that incorporated AgNPs (EHP@Ag). This antibacterial, shape-memory haemostatic sponge enabled the slow and sustained release of AgNPs. Compared with classical gauze and a commercial gelatine haemostatic sponge, the EHP@Ag sponge demonstrated markedly improved haemostatic performance in both a rat liver prick injury model and a rat liver non-compressible haemorrhage model, with a haemostasis time of 22.75 ± 3.86 s and blood loss of 285.25 ± 24.93 mg [149]. Furthermore, EHP@Ag was non-toxic to L929 fibroblasts and HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells), while exhibiting excellent antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, and MRSA [149].

3.4. Film and Membrane Composites Loaded with AgNPs