A Mild Iodide–Triiodide Redox Pathway for Alkali-Metal and Ammonium Ion Intercalation into Layered Tungsten Oxychloride (WO2Cl2)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. WO2Cl2 Synthesis and Characterization

2.2. Intercalation Experiment

2.3. XRD Analysis

2.4. Shannon Radii Analysis

2.5. Raman and Optical Analysis

2.6. SEM Morphology and EDS Analysis

2.7. XPS Analysis

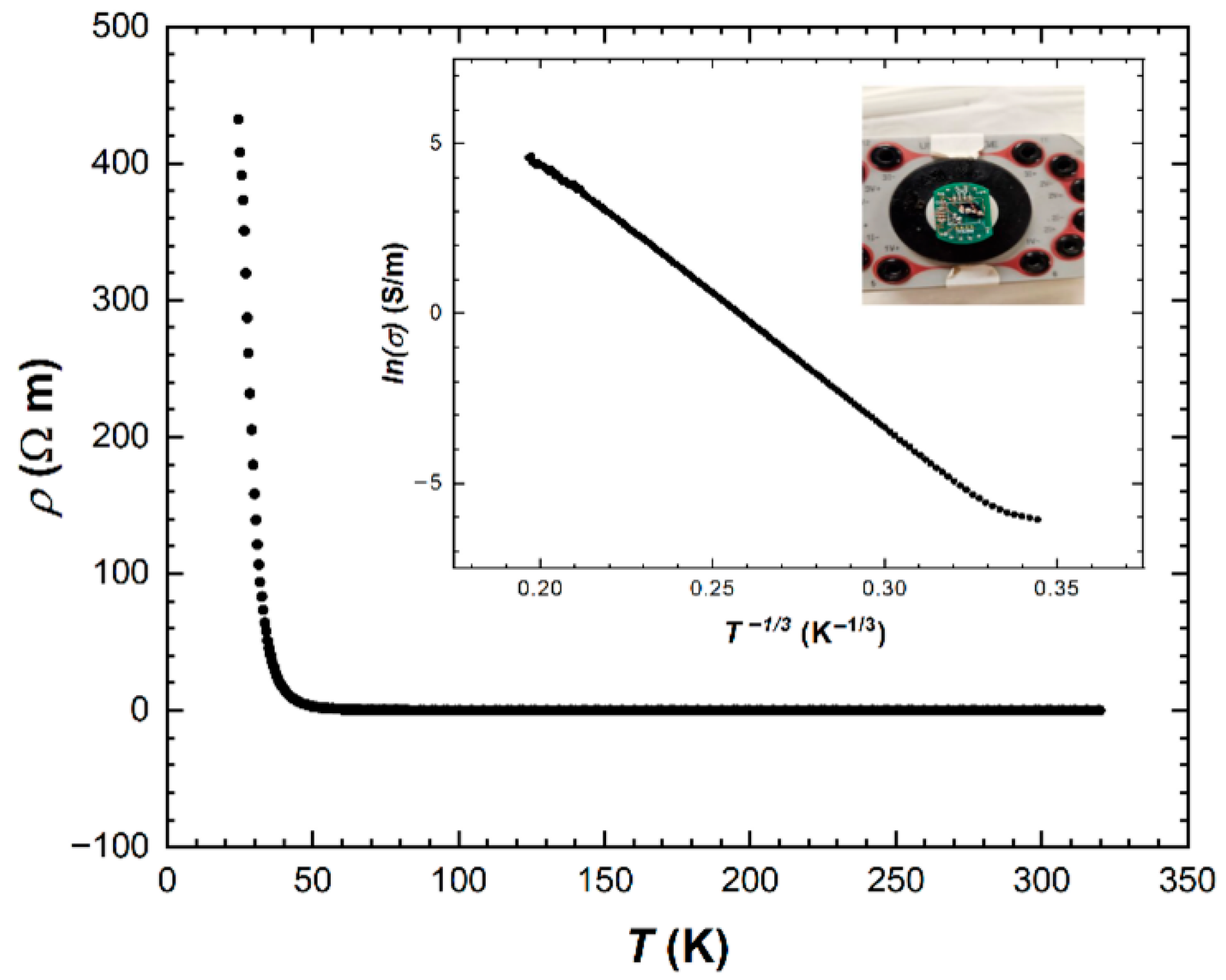

2.8. Resistivity Measurement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and WO2Cl2 Synthesis

3.2. Intercalation

3.3. Material Characterization

3.4. Resistivity Measurement

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geim, A.K.; Grigorieva, I.V. Van der Waals Heterostructures. Nature 2013, 499, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiry, D.; Mohite, A.; Chhowalla, M. Phase Engineering of Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2702–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and Optoelectronics of Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzeli, S.; Ovchinnikov, D.; Pasquier, D.; Yazyev, O.V.; Kis, A. 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, K.; Jones, P.C.; Wiseman, P.J.; Goodenough, J.B. LixCoO2 (0 < x ≤ 1): A New Cathode Material for Batteries of High Energy Density. Mater. Res. Bull. 1980, 15, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Sakurai, H.; Takayama-Muromachi, E.; Izumi, F.; Dilanian, R.A.; Sasaki, T. Superconductivity in Two-Dimensional CoO2 Layers. Nature 2003, 422, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, T.; Sugimoto, T.; Masubuchi, S.; Nohara, M.; Ueda, Y.; Takada, K.; Sasaki, T.; Watanabe, T.; Takagi, H. Electronic Phase Diagram of the Layered Cobalt Oxide System, LixCoO22 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1). Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 165114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, K.P.; Wen, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Chakarawet, K.; Gong, M.; Yang, X. Interlayer Structure Manipulation of Iron Oxychloride (FeOCl) by Potassium Cation Intercalation to Steer H2O2 Activation Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 4294–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Chen, J.; Ding, P.; Shen, B.; Yin, J.; Xu, F.; Xia, Y.D.; Liu, Z.G. Synthesis of Easily Transferred 2D Layered BiI3 Nanoplates for Flexible Visible-Light Photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 21527–21533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhowalla, M.; Shin, H.S.; Eda, G.; Li, L.-J.; Loh, K.P.; Zhang, H. The Chemistry of Two-Dimensional Layered Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Dresselhaus, G. Intercalation Compounds of Graphite. Adv. Phys. 2002, 51, 1–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan, E.; Zandbergen, H.W.; Dennis, B.S.; Bos, J.W.G.; Onose, Y.; Klimczuk, T.; Ramirez, A.P.; Ong, N.P.; Cava, R.J. Superconductivity in CuxTiSe2. Nat. Phys. 2006, 2, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zou, P.Y.; Tang, L.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; Dong, C.; Shan, L.; Wen, H.H. Fabrication and Superconductivity of NaxTaS2 Crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 014534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnemann, B.; Moses, P.G.; Bonde, J.; Jørgensen, K.P.; Nielsen, J.H.; Horch, S.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J.K. Biomimetic Hydrogen Evolution: MoS2 Nanoparticles as Catalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5308–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, B.; Lukatskaya, M.R.; Gogotsi, Y. 2D Metal Carbides and Nitrides (MXenes) for Energy Storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedin, F.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Hill, E.W.; Blake, P.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Novoselov, K.S. Detection of Individual Gas Molecules Adsorbed on Graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shao, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, T.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Wang, H. Flexible and High-Performance Electrochromic Devices Based on Self-Assembled 2D TiO2/Ti3C2Tx Heterostructures. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama, H.; Hayashi, K.; Maeda, K.; Attfield, J.P.; Hiroi, Z.; Rondinelli, J.M.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. Expanding Frontiers in Materials Chemistry and Physics with Multiple Anions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, J.K.; Charles, N.; Poeppelmeier, K.R.; Rondinelli, J.M. Heteroanionic Materials by Design: Progress Toward Targeted Properties. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1805295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, N.; Saballos, R.J.; Rondinelli, J.M. Structural Diversity from Anion Order in Heteroanionic Materials. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 3528–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I.; Nowinski, J.L.; Bruce, P.G.; Gibson, V.C. The Disordered Structure of WO2Cl2: A Powder Diffraction Study. J. Solid State Chem. 1993, 102, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Evangelisti, C.; Marchetti, F.; Pampaloni, G.; Piccinelli, F.; Zacchini, S. Synthesis of a Highly Reactive Form of WO2Cl2, Its Conversion into Nanocrystalline Mono-Hydrated WO3, and Coordination Compounds with Tetramethylurea. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 15342–15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, P.G.; Nowinski, J.; Gibson, V.C.; Hauptman, Z.V.; Shaw, A. Sodium Intercalation into WO2Cl2. J. Solid State Chem. 1990, 89, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, C.-L.; Hwang, H.Y.; Cui, Y. Electrostatic Gating and Intercalation in 2D Materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Clark, G.; Navarro-Moratalla, E.; Klein, D.R.; Cheng, R.; Seyler, K.L.; Zhong, D.; Schmidgall, E.; McGuire, M.A.; Cobden, D.H.; et al. Layer-Dependent Ferromagnetism in a van der Waals Crystal Down to the Monolayer Limit. Nature 2017, 546, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, K.S.; Mandrus, D.; Park, J. Magnetism in Two-Dimensional van der Waals Materials. Nature 2018, 563, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dines, M.B. n-Butyllithium in Hexane Solution Serves as an Excellent Reagent to Effect the Intercalation of Lithium into the Group IVb and Vb Layered Dichalcogenides. Mater. Res. Bull. 1975, 10, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, A.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Lithium Intercalation Compounds of MoS2: Influence of n-BuLi vs. t-BuLi on Material Properties. Small 2015, 11, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Nai, C.T.; Shin, H.S.; Jeong, H.Y.; Liu, B.; Loh, K.P. High-Yield Exfoliation of 2D Chalcogenides Using Lithium, Potassium, and Sodium Naphthalenide. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luxa, J.; Ondrej, J.; David, S.; Rostislav, M.; Miroslav, M.; Markin, P.; Zdenek, S. Origin of exotic ferromagnetic behavior in exfoliated layered transition metal dichalcogenides MoS2 and WS2. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 1960–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, D.D.; García, H.; Primo, A. Molten Salt Derived MXenes: Synthesis and Applications (Lewis-acid molten salts as powerful chemical media). Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Yunki, J.; Wonhwa, L.; Young-Pyo, J.; Jin-Yong, H.; Jea, U.L. Sustainable MXene Synthesis via Molten Salt Method and Nano-Silicon coating for enhanced lithium-ion Battery performance. Nanomaterials 2025, 30, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, J.; Chao, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Kuo, J.-L.; Yan, J.; Shen, Z.X. Phase Evolution of Lithium Intercalation Dynamics in 2H-MoS2 (Electrochemical Control of 2H→1T/dT Transitions). Nanoscale 2017, 9, 7533–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehenkel, D.J.; Bointon, T.H.; Booth, T.J.; Russo, S.; Craciun, M.F. Unforeseen High Temperature and Humidity Stability of FeCl3-Intercalated Few-Layer Graphene (vapor transport, two-zone furnace). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppuluri, R.; Sen Gupta, A.; Rosas, A.S.; Mallouk, T.E. Soft Chemistry of Ion-Exchangeable Layered Metal Oxides (low-temperature ion exchange/topochemical routes in layered hosts). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2401–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, A.A.; Nethravathi, C.; Rajamathi, M. Two-Dimensional Nanosheets and Layered Hybrids of MoS2 and WS2 through Exfoliation of Ammoniated MS2 (M = Mo, W) (ammonia/NH4+ intercalation leading to expanded layers and dispersible sheets). J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Ammonium-Ion Intercalation–Induced Expansion and Phase Regulation in MoSe2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7890–7898. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, K.; Wang, X.; Sun, J. Pre-Intercalation of Tetramethylammonium Ions Expands MoS2 Interlayer Spacing and Tunes Electronic Structure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2401174. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, N.; Athanassov, Y.; Armand, M.; Bonhôte, P.; Pettersson, H.; Azam, A.; Grätzel, M. The Redox Properties of the Iodide/Triiodide Couple in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143, 3099–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Kantor-Innazzone, S.; Unwin, P.R. Electrochemical Potential Control Using the I−/I3− Redox Couple in Scanning Electrochemical Cell Measurements. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 146, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bard, A.J.; Parsons, R.; Jordan, J. (Eds.) Standard Potentials in Aqueous Solution; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, W.M. (Ed.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grätzel, M. Photoelectrochemical Cells. Nature 2001, 414, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmrich, A.; Panman, M.R.; Berntsson, O.; Biasin, E.; Niebling, S.; Petersson, J.; Hoernke, M.; Bjorling, A.; Gustavsson, E.; van Driel, T.B.; et al. Solvent-Dependent Structural Dynamics in the Ultrafast Photodissociation Reaction of Triiodide Observed with Time-Resolved X-ray Solution Scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15754–15765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigenobu, K.; Nakanishi, A.; Ueno, K.; Dokko, K.; Watanabe, M. Glyme–Li salt equimolar molten solvates with iodide/triiodide redox anions. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 22668–22675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, J.F. Lithium Intercalation of WO2Cl2. Mater. Res. Bull. 1988, 23, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.I.; Wladkowski, H.V.; Hecht, Z.H.; She, Y.; Kattel, S.; Samarawickrama, P.I.; Rich, S.R.; Murphy, J.R.; Tian, J.; Ackerman, J.F.; et al. Alkali Metal Intercalation and Reduction of Layered WO2Cl2. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 10482–10488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coordination (Å) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ in 002 (Å) | IR (IV) | IR (VI) | IR (VIII) | IR (XII) | |

| LixWO2Cl2 | 2.72 * | 0.59 | 0.76 | NA | NA |

| NaxWO2Cl2 | 0.98 | 0.99 ■ | 1.02 | 1.18 | 1.39 |

| KxWO2Cl2 | 1.23 | 1.37 ■ | 1.38 | 1.51 | 1.64 |

| RbxWO2Cl2 | 1.51 | NA | 1.52 | 1.61 | 1.72 |

| (NH4)xWO2Cl2 | 1.25 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| % Composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W6+ | W5+ | W6+:W5+ | SEM/EDS (W:M) | |

| WO2Cl2 | 100 | |||

| NaxWO2Cl2 | 73.60 | 26.40 | 1:0.36 | 1:0.25 |

| KxWO2Cl2 | 85.00 | 15.00 | 1:0.18 | 1:0.5 |

| RbxWO2Cl2 | 85.19 | 14.81 | 1:0.17 | 1:0.4 |

| (NH4)xWO2Cl2 | 73.20 | 26.80 | 1:0.37 | 1:0.07 (XPS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samuel, J.; Carter, J.; Ackerman, J.; Tang, J.; Leonard, B. A Mild Iodide–Triiodide Redox Pathway for Alkali-Metal and Ammonium Ion Intercalation into Layered Tungsten Oxychloride (WO2Cl2). Inorganics 2025, 13, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120403

Samuel J, Carter J, Ackerman J, Tang J, Leonard B. A Mild Iodide–Triiodide Redox Pathway for Alkali-Metal and Ammonium Ion Intercalation into Layered Tungsten Oxychloride (WO2Cl2). Inorganics. 2025; 13(12):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120403

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamuel, John, Jefferson Carter, John Ackerman, Jinke Tang, and Brian Leonard. 2025. "A Mild Iodide–Triiodide Redox Pathway for Alkali-Metal and Ammonium Ion Intercalation into Layered Tungsten Oxychloride (WO2Cl2)" Inorganics 13, no. 12: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120403

APA StyleSamuel, J., Carter, J., Ackerman, J., Tang, J., & Leonard, B. (2025). A Mild Iodide–Triiodide Redox Pathway for Alkali-Metal and Ammonium Ion Intercalation into Layered Tungsten Oxychloride (WO2Cl2). Inorganics, 13(12), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120403