Abstract

Halide-dictated stereoselective formation of octahedral Δ-cis-α-[Zn(L)Cl2] or trigonal bipyramidal Λ-[Zn(L)I]I, where L is a chiral tetramine with a pyrrolidine or piperidine core, has been observed in both the solid state and in solution through a combination of SCXRD analysis, NMR spectroscopy, and theoretical calculations. Chameleonic behaviour is exhibited by the bromido compounds which form five- or six-coordinate complexes depending on the nature of the tetramine ligand. Only six-coordinate Δ-cis-α-[Cd(L)X2] complexes are observed for Cd(II), irrespective of L or X.

1. Introduction

Chiral-at-metal complexes are defined as those where the metal is the sole source of asymmetry whereas stereogenic-at-metal (SAM) complexes have at least one other chiral element associated with one or more of the ligands [1]. In either case, configurational integrity is critical and dependent on the nature of the metal ion. The recent renaissance in chiral- and stereogenic-at-metal complexes has mainly involved thermodynamically stable, kinetically inert metal ions where redistribution reactions are limited, enabling controlled complex formation [2]. Stereo-control in SAM complexes where the metal is inherently labile is more problematic and usually requires an asymmetric dictator ligand that enforces the exclusive adoption of a single isomer. A rare exception to this is the recent report from the group of Shionoya regarding an intriguing example of a configurationally robust, tetrahedral chiral-at-zinc complex constructed from achiral ligands [3]. Such cases remain exclusive, and it is more common for control to be exerted through a bi- or multidentate ligand with prescribed chirality.

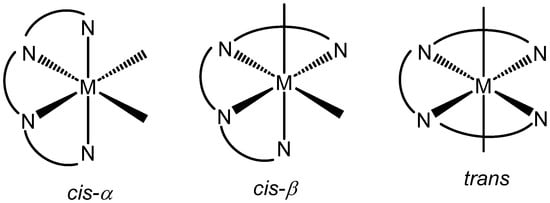

Five- and six-coordinate complexes containing two bidentate ligands or a tetradentate ligand can form, depending on the relative arrangement of the chelate rings, Λ and Δ isomers. For six-coordinate systems of the type [M(L)X2], where L is a tetradentate ligand, there are three geometric possibilities: trans, cis-α, and cis-β (Figure 1). The selective formation of one or other of these will depend, amongst other things, on the charge and size of the metal ion and the nature of the ligand(s) donors and chelate ring size/conformation [4,5,6]. When all three chelate rings are five-membered, cis forms appear to be preferred whereas the inclusion of one or more six-membered chelates, especially in the central ring, can lead to a preferential formation of trans isomers [7,8]. Tetramines with a -CH2CH(R)- central bridge tend not to lock out a single chelate conformation (δ or λ) and show lower configurational control than those ligands with conformationally rigid central chelates [9,10]. For metal ions that are kinetically inert, such as Ru(II) or Rh(III) [9,11], controlling factors can be kinetic in nature whereas for labile metals such as Zn(II), thermodynamic control dictates [12,13,14,15,16]. The cis forms exist as optical isomers (Δ and Λ) and, in the absence of any other discriminating agent such as a chiral anion (This only applies when the complex is a cation), selective formation of one or other of these requires a ligand with at least one pre-fixed chiral element. Identifying controlling factors can be complicated by the presence of not only configurational and conformational options but also, depending on the nature of the ligand, the establishment of further N-based chiral centres upon coordination. Determining the extent of any stereoselectvity in these systems usually relies on a combination of empirical techniques including SCXRD analysis, NMR spectroscopy (when possible), and chiroptical measurements, supplemented by theoretical calculations.

Figure 1.

Potential isomers for [M(L)X2] where L is a tetraamine ligand.

As noted above, configurational stability is a requisite for successful application of these systems as asymmetric catalysts and such control is only possible through appropriate ligand design to ensure absolute preference for a single isomer. Based upon previous observations of critical structural features, such as rigid central chelates, as noted above, we have designed novel tetramine ligands containing a 3-aminopyrrolidine or 3-aminopiperidine unit with the belief that these will enable the construction of configurationally rigid Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes for ultimate use in asymmetric catalysis. To this end, we report here our findings on the selective formation of Δ-cis-α-[M(L)Cl2] and Λ-[M(L)I]I complexes where L is an asymmetric tetramine ligand containing the azacyclic control units and M is Zn(II) or Cd(II).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Piperidine and Pyrrolidine-Based Triamines

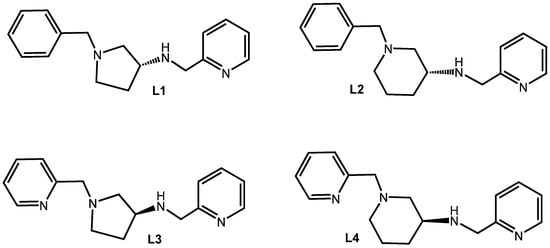

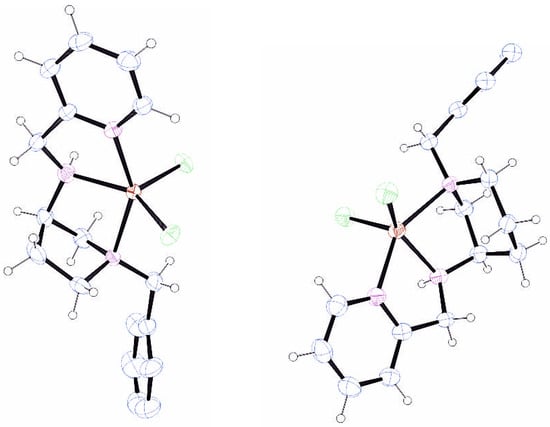

The employment of the asymmetric forms of the two diamines 3-aminopyrrolidine and 3-aminopiperidine in coordination chemistry has been somewhat limited, particularly when it is part of a higher-dentate ligand. A recent Scifinder search (20 October 2025) did not reveal any Zn(II) or Cd(II) complexes containing either diamine unit. This surprising lack of such compounds ignited our interest in developing tri-and tetradentate ligands containing 3(R)-aminopyrrolidine and 3(R)-aminopiperidine cores with an initial focus on the triamine ligands L1 and L2 (Figure 2). The role of this preliminary research was to investigate the influence of the azacycle on the geometry adopted by the triamine upon coordination to Zn(II), as this was anticipated to be maintained in the complexes of the tetramine ligands. Due to the rigidity of the 3-aminopyrrolidine azacycle, when the chiral carbon is fixed as R, the tertiary nitrogen must also be R for the diamine to form a chelate. Thus, it is established that the only unresolved stereochemical issue upon coordination of L1 is that of the secondary nitrogen, which can assume the R or S configuration. At this stage, we were not anticipating a halide effect, so the research focused solely on the ZnCl2 complexes which were readily prepared by mixing ligand and metal salt in alcoholic solvent at room temperature. Although broadened, the 1H NMR spectra of both [Zn(L1)Cl2] and [Zn(L2)Cl2] are consistent with a single isomer, indicating highly stereoselective coordination. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of both complexes was employed to determine the exact stereochemistry (Figure 3). The geometry at the metal is trigonal bipyramidal in both cases with the pyridine and azacyclic tertiary nitrogen occupying the axial positions. The secondary nitrogen has the R absolute configuration and all three nitrogen donors and the zinc are close to coplanar. Inspection of the bond angles for [Zn(L1)Cl2] reveals considerable distortion within the complex, most notably in the intra-metal angles in the trigonal plane which range from 103.28(12)° for the N2-Zn1-Cl2 angle to 142.45(12)° for N2-Zn1-Cl1, with this obtuse angle seemingly resulting from unfavourable steric contacts between Cl1 and the azacyclic backbone. These features are mirrored in the SCXRD molecular structure of [Zn(L2)Cl2] and the related [Zn{S-1-(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)pyrrolidin-3-amine}Cl2], as seen in Figure 2 and the Supplementary Materials. The consequences of this apparent steric compression are further considered in the chemistry of the tetramine ligands below.

Figure 2.

The ligand series.

Figure 3.

Ortep views of the molecular structure of [Zn(L1)Cl2] and [Zn(L2)Cl2] with lattice solvent molecules and selected hydrogens removed for clarity. Pertinent metrics and labelling are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2. Tetramine Ligzand Design and Synthesis

Our tetradentate ligands are based on numerous examples of diamino/dipyridyl systems prevalent in the literature [17,18,19,20,21]. As alluded above, the introduction of a rigid azacycle in the central chelate was a deliberate attempt to enable greater geometric and stereo-control upon coordination. Synthetic feasibility using relatively cheap, available starting materials was a further consideration which led us to the choice of ligands L3 and L4, where the phenyl ring in L1 and L2 has been replaced by a second pyridine group (Figure 2). It should be commented that, due to availability of chemicals, the carbon atom at the 3-position in the azacycle has the S configuration in L3 and L4 as opposed to R for L1 and L2. As noted above, the inclusion of the stereogenic carbon centre is implicit in the design as it dictates the stereochemistry of the ring nitrogen upon coordination; when this carbon has the S configuration, the azacyclic nitrogen is constrained to be R (it is noted that there is a change in CIP priority at the 1-amino nitrogen when the benzyl group is replaced by a pyridyl).

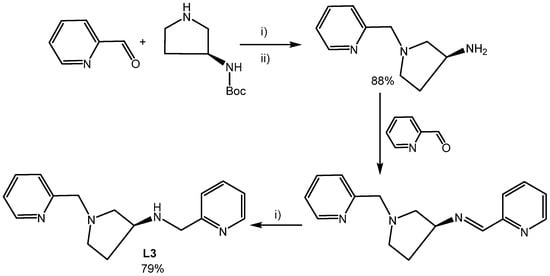

Access to the triamine precursors was easy through the chemoselective condensation of 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde with S-3-Boc-ampy or S-3-Boc-apip and subsequent reduction with NaBH4. Removal of the Boc group under acidic conditions gave the triamine, which underwent a second chemoselective condensation/reduction, to give the saturated tetramines in good yield (Scheme 1 shows the preparation of L3). The unsymmetrical nature of L3 and L4 results in all hydrogens being unique, as evident from the 1H NMR spectra where, except for some overlapping peaks, each resonance is separate and assignable (see Supplementary Materials). This extends to the 13C{1H} NMR spectra which show a total of 16 and 17 peaks, respectively, for L3 and L4.

Scheme 1.

(i) NaBH4, MeOH; (ii) 3M HCl in MeOH.

2.3. [Zn(L3/L4)Cl2] and [Cd(L3/L4)Cl2] Complexes

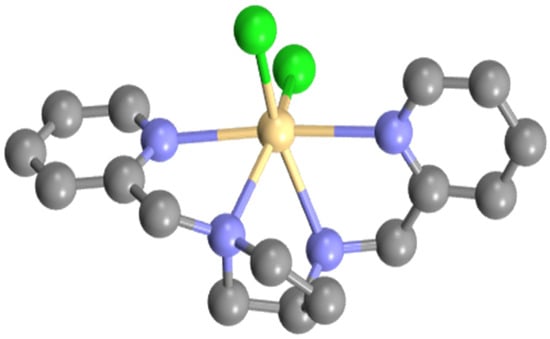

As d10 metal ions, both Zn(II) and Cd(II) show variable coordination modes with multidentate ligands and, for the current systems, five- and six-coordinate complexes can be anticipated. The chlorido complexes were prepared by combining the MCl2 salts and the appropriate ligand in a 1:1 ratio in EtOH at RT. Within minutes, the desired compounds precipitated from the reaction medium as white to cream-coloured solids that proved freely soluble in CDCl3 and CD2Cl2, supporting a neutral, six-coordinate assignment. To establish the absolute structure of these compounds, attempts were made to crystallise them for analysis by SCXRD techniques; however, only the cadmium complex of L3 proved amenable to such analysis, with the molecular structure obtained shown in Figure 4. The metal is six-coordinate, distorted octahedral with the cis-α geometry. This is a common structural motif found in related tetraamine complexes of cadmium(II) with ligands that form three five-membered chelate rings upon coordination [21,22,23]. The Cd-N bond lengths are typical for this type of complex varying from 2.416 to 2.452 Å, with the bonds to the amine donors being shorter than those to the pyridines [21,22,23]. This difference is less pronounced than in a related complex [21], which is explained in part by a more regular octahedron in [Cd(L3)Cl2] with a Npy-Cd-Npy angle of 171.4(3)0 compared to 161.01(10)° in [21]. The bite angles of all three chelate rings are acute, ranging from 67.5(4)° to 71.4(4)°, with other intra-metal angles being consequently expanded to a maximum of 114.13(18)° for Cl1-Cd1-Cl2. The complex adopts the Δ absolute configuration confirming the stereoselective coordination with the secondary nitrogen having the S stereochemistry and the tertiary nitrogen R, as dictated by the S configuration of the carbon. While the configurations of the three chiral centres are RCRNRN in [Zn(L1)Cl2] and [Zn(L2)Cl2], here, it is SCRNSN. The compressional steric impact noted in the former two complexes is not evident here and the N3M planarity observed above is lost in Δ-cis-α-[Cd(L3)Cl2].

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of Δ-cis-α-[Cd(L3)Cl2] with lattice solvent molecules and hydrogens removed for clarity. Pertinent metrics and labelling are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

The 1H NMR spectrum of Δ-cis-α-[Cd(L3)Cl2] shows the presence of the expected single isomer and, with some exceptions for the pyridine hydrogens, well-separated peaks for every unique proton environment. Some peaks are broadened, but this is not extensive and the geminal hydrogens of every CH2 group are obvious, enabling, in combination with other NMR experiments, the assignment of all hydrogen atoms. Retention of the solid-state structure in solution is confirmed on inspection of the NOESY NMR spectrum, which shows a through-space contact between the NH hydrogen and one hydrogen of the azacyclic C2 methylene group, with no observable cross-peak between the ortho hydrogens of the pyridine rings. The NMR spectra of the [Zn(L3)Cl2] complex do not show any peak broadening and are otherwise very similar to those of Δ-cis-α-[Cd(L3)Cl2], suggesting a common structure in both.

The structural analogy extends to the chlorido complexes of L4 with Zn and Cd, both of which are freely soluble in organic solvents and possess closely similar NMR spectra. With the obvious exception of the extra CH2 group in the azacycle, the spectra compare with those already discussed for the complexes with L3 and a common structure is assumed. The broadening that was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of [Cd(L3)Cl2] is again evident in [Cd(L4)Cl2], especially for the ortho hydrogens on the pyridine donors and those in the azacyclic ring, reflecting a degree of fluxionality in the complex and/or a six- to five-coordinate equilibrium in solution.

2.4. [Zn(L3/L4)I]I and [Cd(L3/L4)I2] Complexes

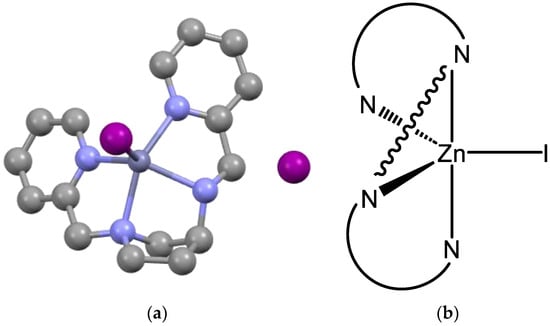

The iodido complexes of L3 and L4 with Zn(II) showed significantly different solubility behaviour to the chlorido derivatives by being poorly soluble in chlorohydrocarbons but freely soluble in dmso. These observations immediately suggested a change in composition, going from Zn(L)Cl2 to Zn(L)I2. The solubility of the iodido complexes suggested a formulation of [Zn(L3/L4)I]I with five-coordinate complex cations and unbound I− counterions. This was confirmed for [Zn(L3)I]I by SCXRD analysis with the molecular structure determined as a result, shown in Figure 5. Inspection of the structure reveals the complex to be five-coordinate with an approximate trigonal bipyramidal geometry defined by a trigonal plane comprised of one of the pyridine donors, the iodide, and the secondary nitrogen; this is distinct from the arrangement observed in the neutral [Zn(L1)Cl2] and [Zn(L2)Cl2] complexes. The remaining donors lie along the z axis, which shows considerable distortion, highlighted by an N-Zn-N bond angle of 143.7(3)°. The five-membered chelates have typical bite angles of slightly less than 80° but deviations from the ideal are evident in the trigonal plane, with L-M-L angles ranging from 110.9(2)° for N2-Zn1-I1 to 131.8(3)° for N2-Zn1-N4. The stereochemistry at both coordinated nitrogens is R and the configuration about the metal, as defined by consideration of chiral edges [24], is Λ (Figure 5). The Zn-N bond lengths vary from 2.094 to 2.185 Å and are consistent with those of 2.120(2), 2.218(2), 2.136(2), and 2.195(2) Å reported for a similar complex of the type [Zn(N4)Cl]ClO4 [21]. Other metrics are typical and are included in the Supplementary Materials. The adoption of a lower coordinate structure for the diiodido complexes compared to the dichlorido species is likely due to sterics with six-coordination being disfavoured for the larger I− ligands. The nature of the azacyclic backbone is a contributory factor, as the relatively fixed orientation of the (CH2)2 and (CH2)3 bridges in L3 and L4 do impact the coordination sphere, as noted in the solid-state structures.

Figure 5.

Molecular structure of [Zn(L3)I]I: (a) representation of [Zn(L3)I]I with lattice solvent molecules and hydrogens removed for clarity; (b) schematic representation of the Λ configuration.

As expected, given the different structure and solvent, the 1H NMR spectrum of [Zn(L3)I]I is appreciably different to that of [Zn(L3)Cl2], with clustering of some of the pyridine and CH2py resonances and a downfield-shifted NH signal. Full analysis of the 2D NMR spectra reveals retention of the solid-state structure in solution with several features being key to this conclusion. The first is the presence of a NOESY contact between both ortho hydrogens of the pyridine rings, indicating a through-space contact as anticipated if the tbp structure persists in solution. Other consolidatory NMR evidence includes the presence of the expected (from the solid-state structure) NOESY cross-peaks between the NH and the methine hydrogen, and one hydrogen of the CH2 group at the 4-position of the azacycle; both these contacts confirm the solution structure. Inspection of the NMR spectra of the product from the reaction of L4 with ZnI2 showed, apart from the extra peaks due to the additional CH2 group, a remarkable resemblance to those for [Zn(L3)I]I. This is emphasised by the downfield shift for the NH hydrogen that resonates around 5.3 ppm in both complexes, along with comparable shifts for the non-ring CH2 groups and the pyridine hydrogens. All this evidence suggests the adoption of the same structure for [Zn(L4)I]I as observed for [Zn(L3)I]I, and this was confirmed on the acquisition of the molecular structure by SCXRD (see Supplementary Materials). The gross structure and configuration mimics that of the L3 complex with comparable bond lengths and angles.

The NMR spectra of the iodo complexes with Cd(II) differed from the Zn(II) in being soluble in CD2Cl2, although the signals in the 1H NMR spectra were broadened significantly in this solvent. The complexes showed less broadening when dissolved in d6-DMSO. These observations suggest a formulation of [Cd(L3/L4)I2], with the solubility in DMSO possibly coinciding with the solvation of one iodide to give [Cd(L3/L4)(DMSO)I]I; this is supported by the fact that the compounds required gentle heating for dissolution.

2.5. Bromido Complexes

The strong preference for [Zn(L3/L4)Cl2] or [Zn(L3/L4)I]I did not translate to the bromido complexes, which showed a dependence on the nature of the tetramine. Based on solubility observations and comparison of NMR spectroscopic data with the established chlorido and iodido systems, the bromido complexes are characterised as [Zn(L3)Br]Br and [Zn(L4)Br2], respectively. Both cadmium complexes [Cd(L3)Br2] and [Cd(L4)Br2] were freely soluble in CD2Cl2, confirming their formulation as neutral species, although a degree of broadening was observed in the 1H NMR spectra of, in particular, the complex with L4. The 1H NMR spectra compare with those of the [Cd(L3)Cl2] complex and, hence, are determined to share the same structure.

2.6. DFT Calculations

DFT calculations were used to examine the preference for five- or six-coordinate geometry as a function of metal and halide. For Zn with L3, only the six-coordinate form is found to be stable with Cl, and we were unable to find a stable geometry for the hypothetical five-coordinate form. For Cd(II), only the six-coordinate complexes proved stable. The calculations show the Δ-cis-α configuration to be 13.9/15.8 kJ mol−1 more stable than cis-β and 8.7/14.0 kJ mol−1 more stable than the trans form for [Zn(L3)Cl2]/[Cd(L3)Cl2], respectively. In contrast to the chlorido derivatives, DFT calculations show a 13.8 kJ mol−1 preference for the five-coordinate form in the iodo complexes of Zn(II) and, although a stable geometry for six-coordination can be located, it has a very long Zn—I bond (3.04 Å compared to 2.83 Å in 5-coordinate form). We surmise that Zn(II) is too small to accommodate six ligands in its first coordination shell when two of those are iodo, but with the smaller Cl−, this is preferred. For the Zn(II) complexes with Br−, both five- and six-coordinate forms are stable with a slight (10.3 kJ mol−1) preference for six-coordination whereas only six-coordinate complexes were stable for Cd(II), irrespective of the halide. Analysis of the various configurational options for [Zn(L3)Cl2] revealed a preference for cis-α over cis-β as there is greater steric crowding in the latter (Table S7, Supplementary Materials). Although the calculations show little difference between cis-α and trans, the preponderance of extant cis forms for tetradentates with solely five-membered chelates [5,6,8,9,10,11,14,15,16] and the empirical NMR data strongly support the cis-α assignment.

2.7. Zn(L5)X2 Complexes

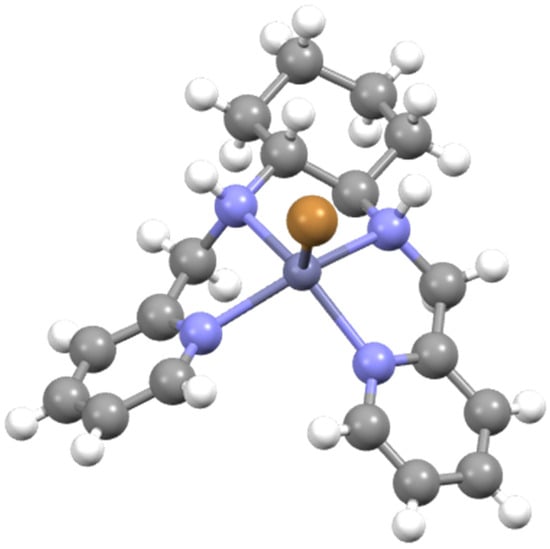

During our investigations, we were alerted to the fact that there were no reports in the literature on complexes of the type Zn(L5)X2 where L5 is (1R,2R)-N1,N2-bis(pyridine-2-ylmethyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamine, even though the related complexes of the N1,N2-dimethyl derivative are known [5]. Partly for comparison with our ligands and partly to account for the absence in the literature, we have prepared and characterised the Zn(L5)X2 series. [Zn(L5)Cl2] was isolated as a hygroscopic cream solid in modest yield and was soluble in CDCl3, suggesting a neutral six-coordinate complex as noted for L3 and L4. The solution NMR spectra revealed a single C2 symmetric species attributable to the highly stereoselective adoption of the cis-α form, as noted for the analogous Cd(II) complex [16]. Surprisingly, when the reaction was repeated and the mother liquor was left to stand on the bench after isolation of the main bulk of the product, a small amount of material crystallised in a form suitable for SCXRD, which revealed a complex of formulation [Zn(L5)(µ-Cl)(ZnCl3)]. This compound is clearly the result of a slight excess of ZnCl2 in the solution after isolation of the main product; no further analysis was performed on this small amount of material and the structure is included in the Supplementary Materials.

A [Zn(L5)Br]Br formulation was assigned to the bromide complex and was confirmed by SCXRD analysis of a sample isolated after slow evaporation of the reaction medium on the bench. The solid-state structure of the complex thus determined is shown in Figure 6. As is evident, the complex is a five-coordinate cation with a gross structure closely analogous to that already described for [Zn(L3)I]+. The NH hydrogens are mutually cis and point towards the coordinated iodide, with one having the R stereochemistry and the other S. The configuration about the metal is Λ as noted for the related complex above (Figure 5). The Zn-N bond lengths of 2.092(7) to 2.157(6) Å are within the expected range and the N-Zn-N bond angles are slightly above 80° for the central five-membered chelate and slightly below 80° for the terminal chelate rings. It is noted that this structure is contrary to that noted for the N,N′—dimethyl analogue [5].

Figure 6.

Molecular structure of one of the two independent molecules of Λ-[Zn(L4)Br]Br with lattice solvent molecules and counterions removed for clarity. Pertinent metrics and labelling are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

As expected from the solid-state structure/composition, the compound is insoluble in CDCl3 and the NMR spectra were therefore recorded in d6-DMSO. Inspection of the 1H NMR spectrum revealed a dominant species with C2 symmetry as determined in the solid-state. However, there is a second unidentified species present (~20%) that appears to also possess C2 symmetry that may be ascribed to cis-α-[Zn(L5)Br2], but could not be confirmed. The iodido complex is formulated as [Zn(L5)I]I based on its solubility and spectral comparison with the analogous bromido complex. Unlike the bromido complex, there is no evidence of a second species in the NMR spectra and the complex, as formulated, is the sole one present in d6-dmso.

3. Materials and Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Apollo Scientific (Manchester, UK) or Fluorochem (Hadfield, UK) commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. L5 was prepared by the literature method [25]. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Fourier 300, DPX 400, and Avance 500 or 600 MHz NMR spectrometers (Billerica, MA, USA). 1H and 13C{1H} NMR chemical shifts were referenced relative to the residual solvent resonances in the deuterated solvent. Mass spectra (Supplementary Materials) were recorded on a Waters LCT premier XE spectrometer (Temecula, CA, USA). UV/Vis spectra were obtained on a Cary 60 spectrophotometer and recorded over the range of 800 to 250 nm, with a 600 nm min−1 scan rate using a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. Emission spectra were collected using a Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer from 700 to 450 nm, with an excitation wavelength of 410 nm and a 600 nm min−1 scan rate.

An Agilent SuperNova Dual Atlas (Santa Clara, CA, USA) diffractometer was used to record the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data using either Cu or Mo radiation. Data were recorded at room temperature or at 200 K with an Oxford Cryosystems cooling apparatus used for temperature regulation. The data were processed using CrysAlisPro 1.171.43.90 [26] and the crystal structures were solved using SHELXT [27] and refined using SHELXL [28]. Non-hydrogen atoms were generally refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. In the final cycles of refinement, ideal hydrogen atom geometry was applied, and a riding model was used with displacement parameters set to either 1.2 or 1.5 times the Ueq values for the atoms to which the hydrogen atoms are bonded. CCDC 2500951-2500958 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free-of-charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/ (accessed on 1 June 2024) or from the CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44-1223-336033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk. A table of pertinent details of the data collection and refinement is included in the Supplementary Materials along with relevant spectroscopic and analytical data in Figures S1–S113 and Tables S1–S7.

DFT calculations were performed using the ORCA quantum chemistry software package (version 6.0.0) [29]. The relevant structures were subjected to geometry optimisation and confirmed as stationary points via vibrational frequency calculations. The conductor-like polarisable continuum model (CPCM) was used to model solvation [30]. The geometry optimisation and vibrational frequency calculations were performed at the PBE-D3BJ level of theory with def2-SVP basis, followed by singe-point energy calculations at the PBE0-D3BJ/def2-TZVP level of theory to obtain accurate electronic energies [31,32,33,34]. Calculations were performed using the facility operated by Advanced Research Computing at Cardiff (ARCCA) on behalf of Supercomputing Wales (SCW). The approach is common practice as detailed in a recent publication [35].

3.1. Synthesis of (R)-1-Benzyl-N-(Pyridin-2-Ylmethyl)Pyrrolidin-3-Amine, L1

A 1:1 mixture of (R)-1-benzyl-3-aminopyrrolidine (0.50 g, 2.84 mmol) and 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (0.3 g, 2.84 mmol) were heated at 50 °C for 4 h in MeOH (20 mL), allowed to cool to RT, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in MeOH (25 mL) and excess solid NaBH4 (0.4 g) added portion-wise over the course of 3 hrs. After removing the MeOH, the residue was treated with water and made basic with solid NaOH (care! Heat). The amine product was extracted into CH2Cl2 (2 × 40 mL), the organic phase was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and all volatiles were removed in vacuo to yield the product as a clear yellow oil. Yield = 508 mg (67%). 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δH 8.45 (d, J 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (td, J 7.6, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.13 (m, 6H), 7.06 (dd, J 7.6, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (d, J 14.2 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (d, J 13.2 Hz, 1H), 3.53 (s, 2H), 3.29 (m, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J 9.4, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.52 (m, 2H), 2.32 (dd, J 9.4, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (m, 1H), 1.58 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δC 159.6 (C), 149.2 (CH), 148.9 (CH), 139.0 (C), 136.5 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 122.4 (CH), 122.0 (CH) 60.8 (CH2), 60.6 (CH2), 58.0 (CH), 53.7 (CH2) 53.4 (CH2), 32.1 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 268.1814 (calc. 268.1814) [L]+, 100%.

3.2. Synthesis of (R)-1-Benzyl-N-(Pyridin-2-Ylmethyl)Piperidin-3-Amine, L2

Prepared as for L1 using (R)-1-benzyl-3-aminopiperidine. Yield = 498 mg (71%). 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δH 8.46 (d, J 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (td, J 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.14 (m, 6H), 7.06 (dd, J 6.9, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (d, J 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (d, J 13.2 Hz, 1H), 3.44 (s, 2H), 2.82 (d, J 10.0 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (m, 1H), 2.57 (m, 1H), 2.01 (t, J 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.92 (t, J 9.0 Hz, 1H), 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.63 (m, 1H), 1.49 (m, 1H), 1.17 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δC 159.9 (C), 149.2 (CH), 138.3 (C), 136.4 (CH), 129.2 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 122.3 (CH), 121.9 (CH) 63.3 (CH2), 59.4 (CH2), 54.1 (CH), 53.8 (CH2) 52.4 (CH2), 31.0 (CH2), 23.7 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 268.1814 (calc. 268.1814) [L]+, 100%.

3.3. Synthesis of (S)-N,1-Bis(Pyridin-2-Ylmethyl)Pyrrolidin-3-Amine, L3

A 1:1 mixture of 3S-Bocaminopyrrolidine (0.5 g, 2.7 mmol) and 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (0.29 g, 2.7 mmol) was heated at 50 °C for 4 h in MeOH (20 mL), allowed to cool to RT, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in MeOH (25 mL) and solid NaBH4 added portion-wise over the course of 3 hrs. After removing the MeOH, the residue was treated with water whereupon an oil separated out (the pH was around neutral). The protected amine was extracted into Et2O (2 × 50 mL) and the combined organic extracts were washed with water, dried over MgSO4, filtered and taken to dryness in vacuo to yield a colourless oil. The Boc-protected amine was dissolved in 3 M HCl in MeOH and the mixture was heated at 50 °C for 8 hrs. After stirring overnight at RT, the volatiles were removed and the residue was dissolved in water (30 mL) and basified to pH > 14. Extraction into CH2Cl2 (2 × 40 mL), drying over MgSO4, filtration and subsequent removal of volatiles gave (S)-1-(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)pyrrolidin-3-amine as a clear yellow oil. Yield = 0.45 g (88%). The oil was used directly for the preparation of (S)-N,1-bis(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)pyrrolidin-3-amine (L3) by adding to a solution of 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (1.1 equiv.) in MeOH (30 mL). After stirring for 2 hrs, the solvent was removed and fresh MeOH was added (30 mL) whereupon an excess of NaBH4 (0.5 g) was added portion-wise over a period of 2 hrs. After leaving to stir overnight, the volatiles were removed, the residue dissolved in water (40 mL), which was made strongly basic by the addition of solid NaOH (care heat!) with ice cooling. The mixture was extracted into CH2Cl2 (2 × 40 mL) and the organic phase was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and taken to dryness in vacuo to give a dark viscous oil, which was heated in vacuo using a short path distillation apparatus to remove a small amount of 2-pyridylmethanol. The undistilled brown oil was the (S)-N,1-bis(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)pyrrolidin-3-amine (L3) product. Yield = 0.57 g (79%). 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δH 8.47 (m, 2H), 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.32 (d, J 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (m, 2H), 3.81 (d, J 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (d, J 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (d, J 13.6 Hz, 1H), 3.68 (d, J 13.6 Hz, 1H), 3.33 (m, 1H), 2.80 (dd, J 9.3, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (m, 1H), 2.57 (m, 1H), 2.42 (dd, J 9.3, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (m, 1H), 1.62 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δC 159.6 (C), 159.1 (C), 149.3 (CH), 149.2 (CH), 136.5 (CH), 136.4 (CH), 123.0 (CH), 122.4 (CH), 122.0 (CH), 121.9 (CH), 62.1 (CH2), 60.9 (CH2), 57.1 (CH), 53.8 (CH2) 53.3 (CH2), 32.1 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 269.1776 (calc. 269.1766) [L]+, 100%.

3.4. Synthesis of (S)-N,1-Bis(Pyridin-2-Ylmethyl)Piperidin-3-Amine, L4

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L3 and obtained as a clear yellow oil without the need for short path distillation. Yield = 0.70 g (92%). 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δH 8.47 (m, 2H), 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.33 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 2H), 3.59 (s, 2H), 2.87 (d, J 10.1 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (m, 1H), 2.63 (m, 1H), 2.08 (t, J 10.5 Hz, 1H), 1.98 (t, J 9.6 Hz, 1H), 1.87 (m, 2H), 1.65 (m, 1H), 1.53 (m, 1H), 1.18 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δC 160.0 (C), 158.9 (C), 149.3 (CH), 149.2 (CH), 136.5 (CH), 136.3 (CH), 123.2 (CH), 122.3 (CH), 121.9 (CH), 121.9 (CH), 64.9 (CH2), 59.8 (CH2), 54.1 (CH2), 54.0 (CH), 52.5 (CH2) 31.0 (CH2), 23.8 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 269.1776 (calc. 269.1766) [L]+, 100%.

3.5. Synthesis of [Zn(L1)Cl2]

A solution of ligand L1 (100 mg, 3.75 × 10−4 mol) in EtOH (10 mL) was added to a solution of ZnCl2 (51 mg, 3.75 × 10−4 mol) in EtOH (10 mL) to give an immediate precipitate that was filtered and air-dried. Yield = 120 mg (79%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 8.50 (br, 1H), 7.95 (t, J 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (br, 1H), 7.43–7.24 (m, 5H), 3.97 (br, 3H), 3.74 (d, J 10.8 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (br, 1H), 2.92 (br, 2H), 2.29 (m br, 2H), 1.91 (br, 1H) 1.68 (br, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 156.7 (C), 147.7 (CH), 139.2 (C), 130.6 (CH), 128.5 (CH), 127.7 (CH), 124.0 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 60.8 (CH2), 58.7 (CH2), 57.4 (CH), 55.9 (CH2) 49.5 (CH2), 28.8 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 366.0719 (calc. 366.0715) [L]+, 95%.

3.6. Synthesis of [Zn(L2)Cl2]

As above. Yield = 120 mg (76%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 8.64 (d, J 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (t, J 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.32 (m, 5H), 4.70 (br, 1H), 4.08 (br, 2H), 3.91 (br, 2H), 3.19 (br, 1H), 2.83 (br, 2H), 2.44 (br, 1H), 2.16 (br, 1H), 1.82 (br, 2H), 1.52 (br, 1H), 1.44 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 155.4 (C), 146.4 (CH), 138.7 (C), 130.1 (CH), 127.5 (CH), 127.5 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 123.2 (CH), 122.3 (CH), 60.5 (CH2), 55.3 (CH2), 50.7 (CH), 50.2 (CH2) 47.3 (CH2), 25.2 (CH2), 19.4 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 380.0873 (calc. 380.0872) [L]+, 20%.

3.7. Synthesis of [Zn(L3)Cl2]

The tetramine L3 (300 mg, 1.12 mmol) was dissolved in EtOH (25 mL) and added to a solution of 1 equivalent of ZnCl2 in EtOH (15 mL). The homogeneous solution was stirred overnight before concentrating in vacuo and precipitation of a cream solid on addition of diethyl ether. Attempts to filter were frustrated by the hygroscopic nature of the solid, so it was extracted into CH2Cl2 and taken to dryness at the pump to give a pale yellow solid. Yield = 362 mg (80%). 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δH 8.84 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (td, J 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (td, J 7.9, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (m, 1H), 7.28 (d, J 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (dd, 7.5, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (d, J 15.3 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (dd, J 15.5, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 4.02 (dd, J 15.6, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.68 (d, J 15.3 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (m, 1H), 3.38 (d, J 9.5 Hz, 1H), 3.31 (dd, J 9.2, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (dd, J 9.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (m, 1H), 2.11 (m, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δC 159.6 (C), 159.1 (C), 149.3 (CH), 149.2 (CH), 139.2 (CH), 137.0 (CH), 124.4 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 122.6 (CH), 62.1 (CH2), 60.9 (CH2), 57.1 (CH), 53.8 (CH2) 53.3 (CH2), 32.1 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 367.0675 (calc. 367.0668) [M − Cl]+, 50%.

3.8. Synthesis of [Zn(L3)Br]Br]

Prepared as for the chlorido complex. The cream precipitate obtained on concentration of the reaction mixture was filtered and air-dried. Yield = 387 mg (70%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 8.78 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (td, J 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (td, J 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (m, 3H), 7.60 (t, J 6.2 Hz, 1H), 5.17 (dd, J 10.0, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 4.36–4.05 (m, 4H), 3.62 (d, J 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (m, 1H), 3.03 (d, J 10.3 Hz, 1H), 2.78 (m, 1H), 2.41 (d, J 10.6 Hz, 1H), 2.28 (m, 1H), 1.75 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 157.7 (C), 155.5 (C), 148.4 (CH), 148.2 (CH), 141.4 (CH), 125.3 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 125.0 (CH), 124.8 (CH), 56.0 (CH), 56.0 (CH2), 53.3 (CH2), 50.0 (CH2) 49.8 (CH2), 29.5 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 413.0128 (calc. 413.0142) [M − Br]+, 20%.

3.9. Synthesis of [Zn(L3)I]I]

Prepared as for the chlorido complex and isolated in several crops upon slow evaporation of the reaction mixture. Each crop was isolated by filtration and air-dried. Combined yield = 586 mg (89%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 8.65 (d, J 5.1 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (s br, 1H), 8.18 (q, J 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (t, J 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (t, J 6.6 Hz, 1H), 4.40–4.07 (m, 4H), 3.62 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (m, 2H), 2.92 (d, J 10.2 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (m, 1H), 2.44 (d, J 10.1 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (m br, 1H), 1.74 (m br, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 157.4 (C), 155.3 (C), 149.1 (CH), 148.7 (CH), 139.9 (CH), 139.6 (CH), 124.7 (CH), 124.1 (CH), 123.8 (CH), 58.0 (CH), 57.7 (CH2), 54.9 (CH2), 50.9 (CH2) 49.0 (CH2), 27.4 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 459.0029 (calc. 459.0024) [M − I]+, 40%.

3.10. Synthesis of [Cd(L3)Cl2]

Prepared as for [Zn(L3)Cl2]. Cream solid isolated in several crops and recrystallised from EtOH. Combined yield = 440 mg (87%). 1H (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): δH 9.12 (s br, 1H), 9.06 (d, J 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (m, 2H), 7.36 (t, J 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (t, J 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.55 (d, J 12.4 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (dd, J 17.2, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (m, 1H), 3.68 (m, 2H), 3.46 (m, 1H), 3.33 (td, J 9.1, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.12 (d, J 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (d, J 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.47 (m, 1H), 2.20 (m, 2H), 1.81 (m br, 1H), 1.43 (m br, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CD2Cl2, 100 MHz): δC 156.7 (C), 154.8 (C), 149.8 (CH), 149.7 (CH), 138.4 (CH), 138.3 (CH), 123.4 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 123.1 (CH), 122.3 (CH), 58.7 (CH2), 57.8 (CH), 55.6 (CH2), 50.7 (CH2) 48.8 (CH2), 26.5 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 417.0411 (calc. 417.0410) [M − Cl]+, 10%.

3.11. Synthesis of [Cd(L3)Br2]]

Prepared as for the chlorido complex. The cream precipitate obtained on concentration of the reaction mixture was filtered and air-dried. Yield = 587 mg (97%). 1H (d6-dmso, 300 MHz): δH 9.01 (d, J 4.6 Hz, 2H), 7.99 (dd, J 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (dd, J 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.44 (m, 4H), 4.52 (d, J 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (d, J 15.1 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (dd, J 17.5, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (d, J 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (d, J 15.1 Hz, 1H), 3.51 (m br, 1H), 3.15 (m, 1H), 2.72 (d, J 9.5 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (m, 1H), 2.18 (dd, J 9.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.77 (m, 1H), 1.23 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 157.7 (C), 155.5 (C), 149.2 (CH), 148.9 (CH), 139.3 (CH), 139.2 (CH), 124.3 (CH), 123.7 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 58.2 (CH2), 57.8 (CH), 54.9 (CH2), 50.6 (CH2) 48.6 (CH2), 26.6 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 460.9897 (calc. 460.9905) [M − Br]+, 3%.

3.12. Synthesis of [Cd(L3)I2]]

Prepared as above. White solid. Yield = 647 mg (91%). 1H (d6-dmso, 300 MHz): δH 8.92 (d, J 4.5 Hz, 1H), 8.81 (d, J 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (td, J 7.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (td, J 7.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (m, 1H), 7.53 (m, 2H), 4.58 (m br, 1H), 4.27 (d, J 15.4 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (dd, J 17.3, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (d, J 17.6 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (d, J 15.8 Hz, 1H), 3.55 (m, 1H), 3.08 (m, 1H), 2.76 (d, J 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (m, 1H), 2.25 (d, J 10.2 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (m br, 1H), 1.38 (m br, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 157.4 (C), 155.3 (C), 149.1 (CH), 148.7 (CH), 139.9 (CH), 139.6 (CH), 124.7 (CH), 124.1 (CH), 123.8 (CH), 58.0 (CH2), 57.7 (CH), 54.9 (CH2), 50.9 (CH2) 48.9 (CH2), 27.4 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 508.9771 (calc. 508.9766) [M − I]+, 2%.

3.13. Synthesis of [Zn(L4)Cl2]

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L3 and ZnCl2. The compound did not precipitate from EtOH, so all volatiles were removed in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (10 mL), filtered, and the solvent was removed under dynamic vacuum to give a pale yellow solid. Yield = 390 mg (83%). 1H (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): δH 8.55 (d, J 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (t, J 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (t, J 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (m, 2H), 4.54 (t, J 7.5 Hz, 1H),4.40 (dd, J 15.7, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (d, J 15.6 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (d, J 15.6 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (dd, J 15.2, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (m, 2H), 2.58 (m, 2H), 2.37 (m, 1H), 2.20 (d, J 14.1 Hz, 1H), 1.62 (m, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CD2Cl2, 100 MHz): δC 157.1 (C), 154.0 (C), 148.0 (CH), 147.8 (CH), 140.4 (CH), 139.0 (CH), 124.6 (CH), 124.6 (CH), 124.1 (CH), 123.7 (CH), 59.7 (CH2), 55.7 (CH2), 53.8 (CH2), 51.7 (CH), 51.5 (CH2) 27.3 (CH2), 20.2 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 381.0829 (calc. 381.0824) [L]+, 40%.

3.14. Synthesis of [Zn(L4)Br2]

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L4 and ZnCl2. Yield = 518 mg (91%). 1H (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): δH 8.55 (d, J 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (m, 2H), 7.77 (d, J 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (m, 3H), 7.34 (m, 1H), 5.17 (dd, J 10.1, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (dd, J 15.3, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 4.05 (d, J 15.8 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (d, J 15.7 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (dd, J 15.4, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (m, 1H), 3.15 (d, J 11.5 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (m, 2H), 2.46 (d, J 12.3 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (m, 2H), 1.61 (m, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CD2Cl2, 100 MHz): δC 156.7 (C), 154.3 (C), 147.3 (CH), 147.3 (CH), 141.2 (CH), 140.7 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 125.0 (CH), 124.8 (CH), 124.7 (CH), 59.2 (CH2), 54.7 (CH2), 54.4 (CH2), 52.0 (CH), 51.3 (CH2) 27.3 (CH2), 20.2 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 427.0302 (calc. 427.0299) [L]+, 45%.

3.15. Synthesis of [Zn(L4)I]I

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L4 and ZnCl2. Several crops were obtained upon slow evaporation of the EtOH. Combined yield = 573 mg (85%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 8.78 (d, J 4.9 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (td, J 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (td, J 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (m, 1H), 5.33 (dd, J 11.1, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (dd, J 15.4, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (m, 3H), 3.22 (m, 1H), 3.13 (d, J 10.9 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (d, J 11.9 Hz, 1H), 2.70 (td, J 12.2, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (m, 1H), 1.93 (d, J 13.3 Hz, 1H), 1.68 (m, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 157.0 (C), 154.7 (C), 147.9 (CH), 147.5 (CH), 141.7 (CH), 141.6 (CH), 125.5 (CH), 125.5 (CH), 125.4 (CH), 124.7 (CH), 58.5 (CH2), 54.1 (CH2), 53.9 (CH2), 51.5 (CH), 50.8 (CH2) 27.2 (CH2), 20.3 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 473.0187 (calc. 473.0181) [L]+, 15%.

3.16. Synthesis of [Cd(L4)Cl2]

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L4 and ZnCl2. The compound did not precipitate from EtOH, so all volatiles were removed in vacuo to give a white solid. Yield = 517 mg (99%). 1H (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): δH 9.26 (s br, 1H), 9.02 (s br, 1H), 7.77 (m, 2H), 7.33 (m, 1H), 7.27 (m, 3H), 4.34 (dd, J 16.4, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (s br, 1H), 3.88 (d, J 16.1 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (s br, 1H), 3.30 (s br, 1H), 3.15 (m br, 2H), 2.63 (s br, 1H), 2.29 (m br, 2H), 1.50 (m br, 2H), 1.16 (s br, 1H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CD2Cl2, 100 MHz): δC 155.8 (C), 154.5 (C), 150.3 (CH), 148.8 (CH), 138.7 (CH), 138.3 (CH), 124.0 (CH), 123.5 (CH), 123.4 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 60.4 (CH2), 57.0 (CH2), 54.1 (CH2), 51.7 (CH), 48.2 (CH2), 24.0 (CH2), 20.2 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 431.0569 (calc. 431.0567) [L]+, 10%.

3.17. Synthesis of [Cd(L4)Br2]

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L4 and CdCl2. The compound precipitated from EtOH as a cream solid which was filtered and air-dried. Yield = 274 mg (44%). 1H (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): δH 9.42 (s br, 1H), 9.13 (s br, 1H), 7.80 (m, 2H), 7.39 (m, 2H), 7.29 (m, 2H), 4.49 (br, 1H), 4.30 (d br, 1H), 3.893 (m br, 1H), 3.52 (br, 1H), 3.34 (br, 1H), 3.22 (br, 1H), 2.97 (br, 1H), 2.68 (br, 1H), 2.31 (m br, 2H), 1.74–1.28 (m br, 3H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CD2Cl2, 100 MHz): δC 155.3 (C), 154.2 (C), 150.3 (CH), 148.6 (CH), 138.8 (CH), 138.3 (CH), 124.2 (CH), 123.4 (CH), 123.4 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 60.1 (CH2), 57.0 (CH2), 54.0 (CH2), 51.7 (CH), 47.9 (CH2), 23.9 (CH2), 20.2 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 475.0061 (calc. 475.0061) [L]+, 5%.

3.18. Synthesis of [Cd(L4)I2]

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L4 and CdCl2. The compound precipitated from EtOH as a pale-yellow solid which was filtered and air-dried. Yield = 472 mg (65%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 9.17 (br, 1H), 9.02 (br, 1H), 8.00 (m, 2H), 7.54 (m, 4H), 4.65 (br, 1H), 4.07 (m, 3H), 3.62 (br, 1H), 3.16 (m, 1H), 3.02 (d, J 9.5 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (br, 1H), 2.35 (m br, 2H), 1.48 (br, 2H), 1.19 (br, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 156.4 (C), 154.6 (C), 149.6 (CH), 147.6 (CH), 139.9 (CH), 139.6 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 124.0 (CH), 124.0 (CH), 124.0 (CH), 59.0 (CH2), 55.8 (CH2), 53.6 (CH2), 52.0 (CH), 47.5 (CH2), 23.5 (CH2), 20.7 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 522.9928 (calc. 522.9923) [L]+, 3%.

3.19. Synthesis of [Zn(L5)Cl2]

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L3 and ZnCl2 using L5 (0.30 g, 1.01 mmol). The compound did not precipitate from EtOH, so all volatiles were removed in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (10 mL), filtered, and the solvent was removed under dynamic vacuum to give a hygroscopic cream solid. Yield = 411 mg (94%). 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δH 8.91 (br, 2H), 7.85 (td, J 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (t, J 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.66 (d, J 12.6 Hz, 2H),4.05 (dd, J 13.3, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 3.29 (br, 2H), 2.31 (m, 2H), 1.79 (m, 2H), 1.25 (m, 4H) ppm. 13C{1H} (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δC 155.5 (C), 148.5 (CH), 139.4 (CH), 124.1 (CH), 123.8 (CH), 60.3 (CH), 48.6 (CH2), 31.0 (CH2) 24.7 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 395.0981 (calc. 395.0983) [L]+, 90%.

3.20. Synthesis of [Zn(L5)Br]Br

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L3 and ZnCl2. The compound did not precipitate from EtOH immediately but formed lovely colourless crystals on standing. Filtered and air-dried. Yield = 417 mg (79%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz, major isomer): δH 8.90 (d, J 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.05 (td, J 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (m, 4H), 4.30 (dd, J 15.9, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 4.06 (d, J 16.6 Hz, 2H), 3.98 (m, 2H), 2.16 (d, J 9.6 Hz, 2H), 1.66 (m, 4H), 1.02 (m, 4H) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 441.0453 (calc. 441.0455) [L]+, 10%.

3.21. Synthesis of [Zn(L5)I]I

This was prepared in a similar manner to that described for L3 and ZnCl2. The compound did not precipitate from EtOH immediately but formed lovely pale-yellow crystals on standing. Filtered and air-dried. Yield = 361 mg (58%). 1H (d6-dmso, 400 MHz): δH 8.72 (dd, J 5.4, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 8.13 (td, J 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (m, 4H), 4.19 (m, 4H), 2.21 (br, 2H), 1.75 (br, 2H), 1.65 (br, 2H), 1.06 (m, 4H) ppm. 13C{1H} (d6-dmso, 100 MHz): δC 156.1 (C), 148.5 (CH), 140.5 (CH), 125.1 (CH), 124.6 (CH), 59.6 (CH), 47.7 (CH2), 29.6 (CH2) 24.8 (CH2) ppm. HRMS (ES): m/z 487.0350 (calc. 487.0337) [L]+, 50%.

4. Conclusions

The adoption of either the six-coordinate Δ-α-[Zn(L)X2] or five-coordinate Λ-[Zn(L)X]X complexes, where L is an asymmetric tetramine, is determined by the nature of the halide, with Cl− giving the former and I− the latter. Bromide co-ligands are less discriminatory with both five- and six-coordinate complexes forming, depending on the nature of the tetramine L. Six-coordinate complexes are preferred in all cases with Cd(II), irrespective of the tetramine or the halide co-ligand, with preferential formation of the Δ-α-[Cd(L)X2] isomer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics13120393/s1, Figures S1–S105: NMR and mass spectra of the compounds. Tables S1–S4: SCXRD collection and refinement data. Figures S106–S113: Molecular structures. Tables S5–S10: Calculated energies, bond lengths and atomic coordinates.

Author Contributions

P.D.N.: project conception, synthesis and data collection. J.A.P.: calculations. B.M.K. performed the SCXRD data collection, solution and refinement. G.L., H.A.A.A. and O.A.W.: synthesis and data collection. P.D.N., J.A.P. and B.M.K. contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was part-funded by Al Baha University, KSA (H.A.A.A.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Cardiff University for support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cruchter, T.; Larionov, V.A. Asymmetric catalysis with octahedral stereogenic-at-metal complexes featuring chiral ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 376, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinlandt, P.S.; Zhang, L.; Meggers, E. Metal Stereogenicity in Asymmetric Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4764–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Liu, Y.; Ube, H.; Nagata, K.; Shionoya, M. Asymmetric construction of tetrahedral chiral zinc with high configurational stability and catalytic activity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, M.; Que, L., Jr. Ligand Topology Tuning of Iron Catalyzed Hydrocarbon Oxidations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2179–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Lin, J.; Xia, C.; Sun, W. Multifunctional Zn-N4 Catalysts for the Coupling of CO2 with Epoxides into Cyclic Carbonates. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 10386–10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.; Sabat, M.; Fraser, C.L. Metal Complexes with Cis r Topology from Stereoselective Quadridentate Ligands with Amine, Pyridine, and Quinoline Donor Groups. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 5545–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnich, B.; Harrowfield, J.M. Conformational Dissymmetry. Circular Dichroism Spectra of a Series of Complexes Containing a Quadridentate Amine Ligand with Chair Six-Membered Chelate Rings. Inorg. Chem. 1975, 14, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnich, B.; Kneen, W.R.; Phillip, A.T. The Relationship Between Chelate Ring Size and the Stereochemistry of SomeCobalt(III) Complexes Containing Quadridentate Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 1969, 8, 2567–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, R.R.; Vagg, R.S.; Williams, P.A. Chiral Metal Complexes. 26*. Metal Complexes of the New Stereospecific Tetraamine Ligand 3R,4R- and 3S,4S-Diphenyl-l,6-di(2-pyridyl)-2,5&azahexane. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1988, 148, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, R.R.; Vagg, R.S.; Williams, P.A. Chiral Metal Complexes. 25*. Cobalt Complexes of Some Linear Mesomeric Tetraamine Ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1987, 128, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popowski, Y.; Goldberg, I.; Kol, M. The stereoselectivity of bipyrrolidine-based sequential polydentate ligands around Ru(II). Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7932–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; So, S.M.; Chagal, L.; Lough, A.J.; Kim, B.M.; Chin, J. Stereoselective Recognition of Vicinal Diamines with a Zn(II) Complex. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8966–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, I.; Ghosh, P. Zinc(II) and PPi Selective Fluorescence OFF ON OFF Functionalityof a Chemosensor in Physiological Conditions. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 4229–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, N.C.; Bera, P.K.; Ghosh, D.; Abdi, S.H.R.; Kureshy, R.I.; Khan, N.H.; Bajaj, H.C.; Suresh, E. Manganese complexes with non-porphyrin N4 ligands as recyclable catalyst for the asymmetric epoxidation of olefins. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cao, B.; To, W.-P.; Tse, C.-W.; Li, K.; Chang, X.-Y.; Zang, C.; Chan, S.L.-F.; Che, C.-M. The effects of chelating N4 ligand coordination on Co(ii)-catalysed photochemical conversion of CO2 to CO: Reaction mechanism and DFT calculations. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7408–7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Cao, Q.-N.; Zhang, L.-M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Gou, S.H.; Fang, L. Two chiral mononuclear and one-dimensional cadmium(II) complexes constructed by (1R,2R)-N1,N2-bis(pyridinylmethyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamine derivatives: Effect of positional isomerism. Solid. State Sci. 2013, 16, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claros, M.; Ungeheuer, F.; Franco, F.; Martin-Diaconescu, V.; Casitas, A.; Lloret-Fillol, J. Reductive Cyclization of Unactivated Alkyl Chlorides with Tethered Alkenes Under Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4869–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, T.M.; Hekking, K.F.W.; Knijnenburg, Q.; de Bruin, B.; Budzelaar, P.H.M.; de Gelder, R.; Smits, J.M.M.; Gal, A.W. Cobalt Chloride Complexes of N3 and N4 Donor Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 2003, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, R.R.; Stephens, F.S.; Vagg, R.S.; Williams, P.A. Chiral metal complexes 34. Stereospecific cis-α coordination to cobalt(III) by the new tetradentate ligand N,N′-dimethyl-N,N′-di(2-picolyl)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1991, 182, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, M.M.; Rechani, P.R.; Diaz, J.A. Complexes with Asymmetric Tetramine Ligands. Part I. Synthesis and Characterization of Cobalt (III) Complexes. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 1980, 11, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikata, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Yasuda, S.; Tsuruta, A.; Hagiwara, T.; Konno, H.; Matsuo, T. Effect of methoxy substituents on fluorescent Zn2+/Cd2+ selectivity of bisquinoline derivatives with a N,N′-dimethylalkanediamine skeleton. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 7411–7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikata, Y.; Yasuda, S.; Hagiwara, T.; Konno, H.; Shoji, S. Alkyl substituents control the Cd2+-selectivity of fluorescence enhancement in N,N′-bis(2-quinolylmethyl)ethylenediamine derivatives. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2024, 571, 122218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Gou, S.H.; Fang, L. Five chiral Cd(II) complexes with dual chiral components: Effect of positional isomerism, luminescence and SHG response. J. Solid. State Chem. 2015, 221, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamula, O.; von Zelewsky, A.; Bark, T.; Stoeckli-Evans, H.; Neels, A.; Bernardinelli, G. Predetermined Chirality at Metal Centers of Various Coordination Geometries: A Chiral Cleft Ligand for Tetrahedral (T-4), Square-Planar (SP-4), Trigonal-Bipyramidal (TB-5), Square-Pyramidal (SPY-5), and Octahedral (OC-6) Complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2000, 6, 3575–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, L.; Wang, Q.; Duan, X.-F.; Zi, G. Synthesis, structure, and catalytic activity of chiral Cu(II) and Ag(I) complexes with (S,S)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-based N4-donor ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro, Rigaku OD: Yarnton, UK, 2024.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 6.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becke, A.D.; Johnson, E.R. A density-functional model of the dispersion interaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 154101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward Reliable Density Functional Methods Without Adjustable Parameters: The PBE0 Model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, I.; Neese, F.; Bistoni, G. An induced-fit model for asymmetric organocatalytic reactions: A case study of the activation of olefins via chiral Brønsted acid catalysts. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8848–8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).