Abstract

This study investigates the formation, physicochemical properties, and applicability of surfactant-free microemulsions (SFMEs) as nanoreactors for the synthesis of silicon dioxide nanoparticles. Surfactant-free systems offer a promising and environmentally benign alternative to traditional microemulsions in which particle formation is governed by surfactants, yet their structural behavior and synthesis mechanisms remain insufficiently understood. A ternary system composed of water, ethanol, and n-pentanol was selected as a model, and its structural organization was analyzed through electrical conductivity, surface tension, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements. The results revealed a broad single-phase region, indicating high miscibility of the components and the formation of dynamically connected polar domains. Electrical conductivity data suggested gradual reorganization of the internal structure without a distinct percolation threshold, while surface tension analysis and the corresponding Gibbs free energies of aggregation (ΔG°) reflected a weaker thermodynamic driving force for aggregation compared to systems containing longer-chain alcohols. DLS measurements confirmed the presence of fluctuating aggregates with hydrodynamic radii between 30 and 85 nm, consistent with literature values for surfactant-free systems. Based on these findings, silica nanoparticles were synthesized within selected compositions of the single-phase region. The resulting particles exhibited predominantly spherical morphology and variable dispersity, reflecting the moderate structural stability of the underlying microemulsion. The synthesized silica nanoparticles typically ranged from approximately 0.9 to 1.2 μm in diameter, reflecting the structural characteristics of the selected SFME compositions. Overall, the results demonstrate that water/ethanol/n-pentanol SFMEs provide new insights into surfactant-free aggregation processes and offer a sustainable route for the synthesis of inorganic nanoparticles.

1. Introduction

Microemulsions are thermodynamically stable and isotropic mixtures of water, oil, and surfactants that have attracted significant research interest due to their distinctive physicochemical characteristics and wide range of industrial applications. Conventional microemulsions, or surfactant-based microemulsions (SBMEs), rely on surfactants to stabilize the interface between two normally immiscible liquids. These systems can form different structures such as oil-in-water (O/W) droplets, water-in-oil (W/O) droplets, and bicontinuous phases [1,2,3,4]. However, the reliance on surfactants introduces several challenges, including environmental concerns, high costs, and potential toxicity issues [5,6]. As a result, there has been increasing focus on the development of surfactant-free microemulsions (SFMEs), which can offer similar advantages without the drawbacks associated with surfactants.

Over the past decade, significant progress has been made in the field of SFMEs, with research ranging from the development of stable systems using ionic liquids to investigations on how simple electrolytes affect weakly associated microemulsions [7,8,9]. More recent studies have explored the impact of eutectic solvents on the stability of SFMEs, further advancing our understanding of their structural behavior [10,11,12,13]. Of particular relevance to the present work is the application of SFMEs in nanoparticle synthesis, which enables precise control over the size and morphology of nanoparticles [14,15,16,17].

A variety of advanced methods are employed to analyze the microstructure and stability of these systems, including electrical conductivity measurements, surface tension analysis, dynamic light scattering (DLS), and transmission electron microscopy [17,18]. Such techniques provide valuable insight into the internal organization of SFMEs and their physicochemical dynamics, contributing to the broader understanding of these sustainable and cost-efficient alternatives to conventional SBMEs.

Beyond their physicochemical significance, microemulsions also serve as nanoreactors in the controlled synthesis of nanoparticles. Microemulsion synthesis is considered one of the most precise bottom-up approaches for producing nanomaterials, as it uses stable, nanometer-sized droplets dispersed in a continuous phase as confined reaction domains. These droplets, which form the basis of water-in-oil type microemulsion structures, allow chemical reactions to take place within well-defined volumes, enabling controlled nucleation and growth of nanoparticles. Reactants are dissolved within each droplet, and mass transfer between them occurs through mechanisms such as collisions, transient fusion, content exchange, and separation [19,20].

The role of surfactants in microemulsion systems has been thoroughly described by Jurkin and Gotić, emphasizing that their function extends beyond mere stabilization of the dispersed phase. Surfactants adsorb onto the surface of growing nanoparticles, preventing aggregation while simultaneously directing their morphology. By selecting the type of surfactant, it is possible to influence the shape of the resulting nanoparticles; for example, certain systems have been shown to produce spherical, rod-like, or wire-like structures [21].

The size of the resulting nanoparticles can be largely linked to the size of the droplets, which depends on the water-to-surfactant ratio (R), system composition, and dynamic behavior. Increasing the R-value leads to an increase in the diameter of the aqueous cores, enabling the synthesis of larger particles. However, the final nanoparticle size is not determined solely by the droplet dimensions. It is also significantly influenced by coagulation processes between droplets, collision frequency, and the kinetics of reaction and core growth [19]. Additionally, the choice of reducing agent plays a major role in defining particle size and distribution. Lisiecki and Pileni demonstrated that the use of hydrazine as a reducing agent leads to smaller copper nanoparticles (2–10 nm) due to rapid nucleation, whereas sodium borohydride results in larger particles (20–28 nm), attributed to slower reaction rates and prolonged growth [22].

This method offers several advantages. It allows the synthesis of nanoparticles with a narrow size distribution and high specific surface area, making them suitable for applications in catalysis, drug delivery, and electronics. The flexibility of the system composition enables the preparation of various nanomaterials, including silicon dioxide, metal oxides, and magnetic nanoparticles. The process proceeds under mild conditions, without the need for high temperature, pressure, or inert atmospheres [20].

In conventional microemulsions, surfactants play a crucial role in stabilizing the oil–water interface. The droplet size, and thus the nanoparticle size, is controlled by the phase ratio and surfactant concentration [20,23]. Furthermore, surfactants adsorb on the particle surface during growth, preventing aggregation and selectively stabilizing certain crystal faces, which enables control over the final nanoparticle morphology [24].

In contrast, surfactant-free systems avoid the use of traditional surfactants and rely on specific intermolecular interactions between components such as water, alcohol, and oil. These systems are simpler to prepare, contain fewer components, and enable synthesis in ion-free environments without toxic stabilizers [17]. They are particularly suitable for applications that require the absence of ionic species, such as the synthesis of sensitive functional materials. However, the SFME approach still faces challenges regarding precise control over nanoparticle size and shape, and it remains sensitive to minor variations in composition and reaction conditions. In addition, its scalability for industrial applications has yet to be fully demonstrated.

In this study, we investigate the formation and physicochemical properties of a novel surfactant-free microemulsion within the ternary system composed of water, ethanol, and n-pentanol. The system is characterized using electrical conductivity, surface tension, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements to provide detailed insight into its internal structure and stability. Furthermore, the developed SFME is employed as a nanoreactor for the synthesis of silica nanoparticles using tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) as a precursor, enabling the examination of correlations between the microemulsion composition and the morphology of the resulting silica nanostructures.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phase Diagram

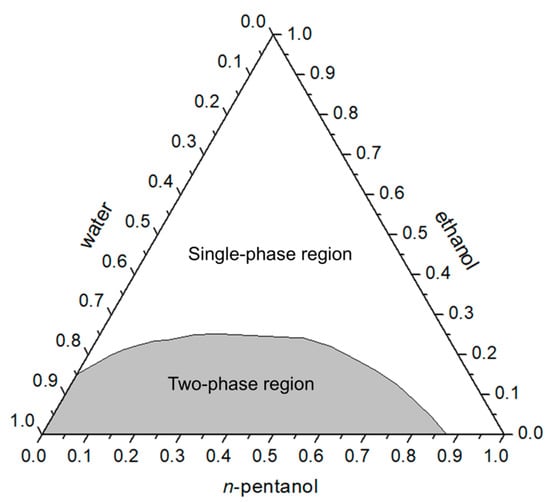

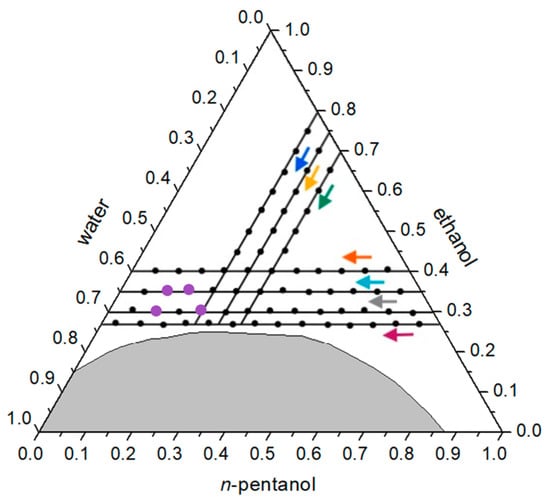

The phase diagram of the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system (Figure 1) shows the widest single-phase region among the systems investigated. This region occupies the upper-central area of the ternary diagram and extends further toward the apices corresponding to n-pentanol and water. Such an arrangement indicates pronounced miscibility of n-pentanol with the other components, even at reduced ethanol concentrations, suggesting that the shorter alkyl chain of this alcohol enhances mutual solubility and contributes to overall system stability.

Figure 1.

Phase diagram of the ternary system water/ethanol/n-pentanol (mass fractions) showing the single-phase and two-phase regions.

The broad extent of the single-phase region demonstrates that stable mixtures form across a wide composition range, including mixtures rich in both water and n-pentanol. This finding further confirms the role of ethanol as an amphiphilic mediator, while highlighting the decisive influence of the third component’s structure—the alkyl chain length—on overall miscibility.

The single-phase region was identified visually as the area corresponding to clear, homogeneous mixtures, whereas the two-phase region was characterized by turbidity and visible phase separation. Analysis of the single-phase area showed that it occupies approximately 66.4% of the total ternary diagram, which is significantly larger than in systems containing longer-chain alcohols. This value lies at the upper end of the range typically associated in the literature with potential microemulsion behavior in the absence of surfactants [5].

In the classical study by Othmer et al. (1941), which presented the phase diagram for the same ternary system at 25–26 °C, the single-phase region covered approximately 63.7% of the total area [25]. This value is very close to the results obtained in the present work (66.4%), and the shape of the region shows strong similarity, including the extension toward both the water and n-pentanol apices. Such correspondence confirms that the expanded miscibility region is an intrinsic feature of systems containing n-pentanol and can be explained by the greater compatibility of shorter alkyl chains with both phases.

Based on these results, selected points from the single-phase region were used for further experimental characterization (electrical conductivity, DLS, and surface tension measurements).

The system with n-pentanol exhibited a particularly wide single-phase region, confirming that shortening the alkyl chain increases the overall miscibility of the components, consistent with expectations based on the higher polarity of shorter alkanols. In this system, ethanol reaffirmed its essential role as an amphiphilic mediator, promoting the stability of mixtures between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic components. Notable differences were observed in the shape of the single-phase region: in the system with n-pentanol, it extends more deeply toward the apices of the ternary diagram, while in the n-heptanol system it narrows significantly, especially at low ethanol concentrations. Although systems with higher miscibility—such as the one with n-pentanol—provide a broader formulation space, they also require careful examination within the single-phase region. Transparency does not necessarily guarantee the presence of a microemulsion structure; thus, a wide single-phase area may also include compositions lacking defined nanostructures. In this respect, systems with narrower single-phase regions, such as those containing n-heptanol, offer clearer compositional boundaries and greater control when selecting points for synthesis and characterization [18].

2.2. Electrical Conductivity

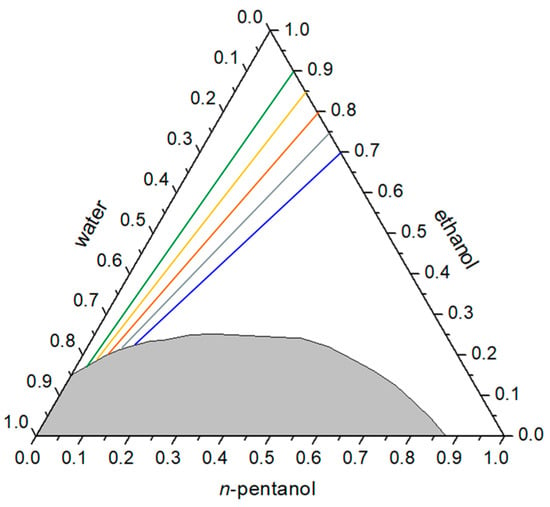

Electrical conductivity measurements provide insight into changes in the internal organization of surfactant-free microemulsion systems. In this study, all measurements were performed along paths in the ternary phase diagram at a constant ethanol-to-oil phase alcohol ratio, with n-pentanol serving as the oil phase. Variations in electrical conductivity were analyzed as a function of the water mass fraction (Figure 2 and Figure 3), with the aim of identifying possible structural transitions within the single-phase region.

Figure 2.

Selected paths for measuring electrical conductivity in the ternary system water/ethanol/n-pentanol at a constant ethanol/oil phase ratio. The ternary diagram is expressed in mass fractions. Multicolored solid lines represent different RE/P values (from 2.33 to 9) along which the conductivity measurements were performed.

Figure 3.

Electrical conductivity (κ) as a function of the mass fraction of water (ww) for the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system at a constant RE/P ratio.

Conductivity curves for the system with n-pentanol show a continuous and gradual increase across the entire investigated range of water mass fractions. In the low-water region (wp < 0.30), the conductivity increases only slightly, suggesting the presence of isolated polar domains, similar to the behavior observed in the system with n-heptanol. At higher water contents, the increase becomes more pronounced, but the κ(ww) dependence remains smooth, without the sharp rise or divergence typically associated with a well-defined percolation threshold. Instead, the conductivity evolution reflects a gradual microstructural rearrangement.

This smooth progression indicates a progressive interconnection of polar domains and increasing continuity of the polar environment, but without a distinct breakpoint that would allow quantitative extraction of percolation parameters. Although changes in slope signal enhanced ionic mobility at elevated water fractions, no clear compositional boundary separating different organizational regimes is observed.

Such behavior is consistent with observations in similar surfactant-free microemulsion systems, where microstructural connectivity develops gradually, particularly when a component with high solubility in both phases is present [26,27].

Ethanol likely plays a dual role by stabilizing transient polar aggregates and facilitating charge transfer through hydrogen-bond-mediated pathways. This resembles hydrotropic systems, where electrical conductivity does not display sharp transitions even when aggregation is confirmed by complementary techniques.

In summary, the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system displays gradual development of polar connectivity without a distinct percolation-type transition. Electrical conductivity is therefore suitable for tracking overall trends in polar domain growth, although its sensitivity is limited in systems that reorganize continuously rather than through discrete structural changes.

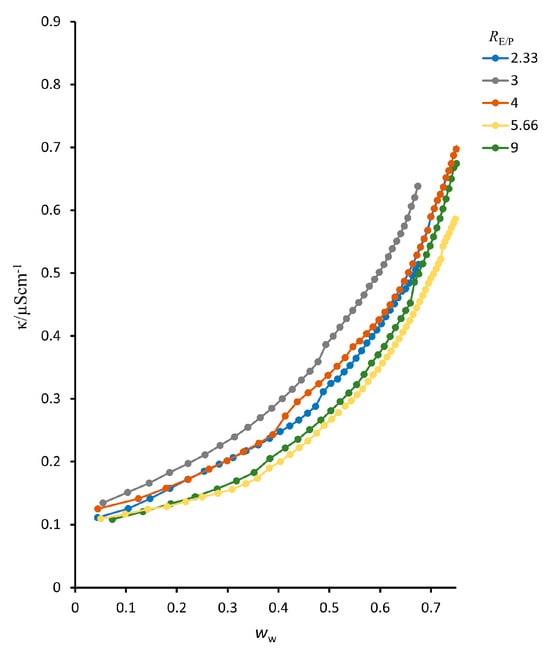

2.3. Surface Tension

Surface tension was investigated in the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system along three different experimental paths, corresponding to initial water-to-ethanol ratios of 55:45, 50:50, and 45:55. In all cases, the concentration of n-pentanol was gradually increased within the single-phase region until the measured tension values stabilized—over multiple measurements—at approximately 25 mN m−1. The results are presented in Figure 4, showing a characteristic decrease in surface tension, which—after reaching a certain threshold—transitions into either a slight increase or a plateau.

Figure 4.

Surface tension of the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system measured along three different paths within the single-phase region of the phase diagram, shown as a function of the natural logarithm of the molar concentration of n-pentanol (ln[c/(mol L−1)]). The paths correspond to the following initial compositions: (a) 55% water/45% ethanol, (b) 50% water/50% ethanol, and (c) 45% water/55% ethanol.

For the mixture with an initial water-to-ethanol ratio of 55:45 (Figure 4a), surface tension decreases up to ln[c/(mol L−1)] = 0.3, which corresponds to an n-pentanol concentration of approximately 1.35 mol L−1. Based on the known masses of the components, the molar fraction of n-pentanol at this point was calculated to be x = 0.0511, and the corresponding standard free energy of aggregation was ΔG° = −7.36 kJ mol−1.

For the initial 50:50 ratio (Figure 4b), aggregation also occurs at the same concentration (ln[c/(mol L−1)] = 0.3), but the molar fraction of n-pentanol at this point is slightly lower (x = 0.0454), and the standard free energy of aggregation is slightly more negative: ΔG° = −7.65 kJ mol−1.

In the system with a 45:55 water-to-ethanol ratio (Figure 4c), aggregation occurs at a higher concentration (ln[c/(mol L−1)] = 0.4; c ≈ 1.49 mol L−1), with a corresponding molar fraction of n-pentanol of x = 0.0596. The calculated standard free energy of aggregation in this case is ΔG° = −6.99 kJ mol−1, indicating a weaker tendency for aggregation. This is likely a consequence of increased stabilization of monomeric n-pentanol species in the presence of higher ethanol content, which shifts the equilibrium toward higher concentrations.

A comparative analysis with literature data for analogous systems reveals a clear trend of increasing standard free energy of aggregation (ΔG°) with decreasing alkyl chain length of the alcohol, corresponding to a progressively weaker tendency to aggregate. The system containing n-heptanol shows the lowest (most negative) ΔG° values, ranging from −10.20 to −9.37 kJ mol−1, indicating a pronounced thermodynamic preference for aggregate formation. These values are consistent with literature data for systems containing n-octanol, further supporting the notion that longer alkyl chains promote phase segregation and the formation of stable, compact aggregates [28].

In contrast, the system with n-pentanol exhibits higher (less negative) ΔG° values, showing a clear trend toward weaker aggregation (−7.95 to −6.99 kJ mol−1). These differences suggest that shorter-chain alcohols, owing to their greater compatibility with the aqueous phase and reduced hydration repulsion, favor the formation of larger, more flexible, and thermodynamically less stable aggregates.

This behavior is fully consistent with the model proposed by Zemb et al., according to which the size and stability of aggregates in surfactant-free microemulsions arise from a balance between mixing entropy and repulsive hydration forces [29]. Within this framework, the higher ΔG° values observed in systems with shorter-chain alcohols reflect the reduced contribution of hydration forces, allowing aggregates to form only at higher concentrations but with a smaller free energy change relative to the monomeric state—indicating lower thermodynamic stability of such aggregates.

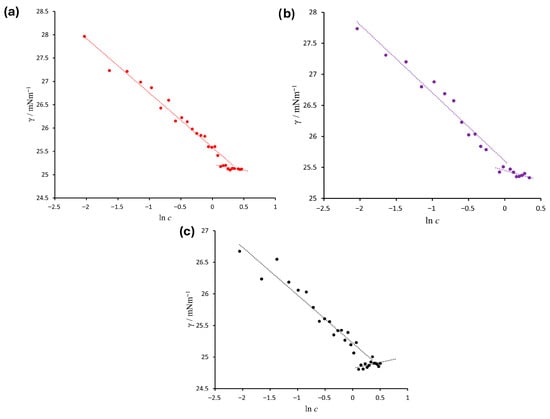

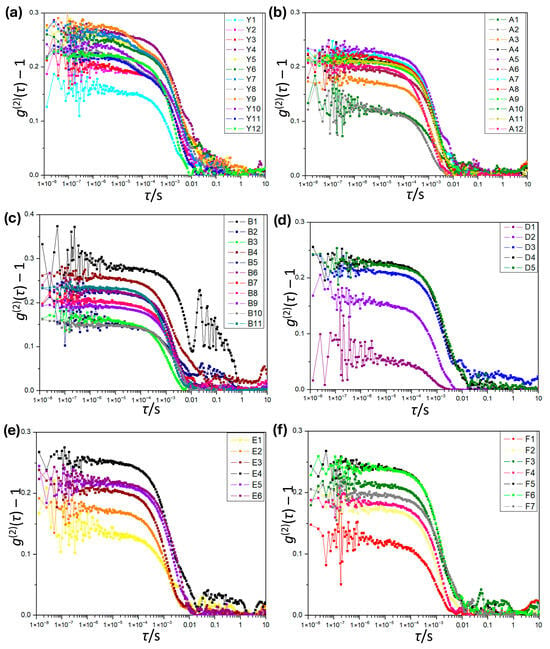

2.4. DLS Analysis and Interpretation

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was applied to investigate aggregation structures within the transparent, single-phase regions of the ternary system, corresponding to the so-called pre-Ouzo region. For this purpose, a series of samples with constant ethanol or higher-alcohol content were prepared, as illustrated in Figure 5. Stable mesostructured aggregates are expected to form in these compositions, while the system remains macroscopically homogeneous. Intensity correlation functions were analyzed as indicators of the degree of aggregation and fluctuation dynamics, and hydrodynamic radii were determined for compositions located closer to the phase-separation boundary.

For most of the measured compositions, the correlation functions exhibited strong noise, and fitting yielded low R2 values, preventing reliable calculation of hydrodynamic radii. Therefore, only the samples for which the fitting was consistent and produced reproducible results were included in the analysis. This observation aligns with the literature, which emphasizes that DLS in surfactant-free microemulsion (SFME) systems is often only qualitatively informative, since fluctuations and irregular aggregate morphology complicate interpretation [30].

Figure 5.

Ternary diagram with marked paths of composition series expressed in mass fractions, for dynamic light scattering measurements in the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system. Hydrodynamic radii for the four indicated compositions are presented in Table 1. Colored dots represent the compositions that yielded reproducible DLS results, while colored arrows indicate the direction of increasing water content along each path.

Table 1.

Hydrodynamic radii of selected samples in the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system.

Intensity correlation functions (Figure 6) exhibit more stable and pronounced profiles in samples located closer to the phase-separation boundary, particularly along lines E and F. In this system, aggregate formation is clearly evident in the left region of the ternary diagram, within the oil-in-water (O/W) microemulsion domain, corresponding to the pre-Ouzo region. Consistent with previously studied systems, a trend of increasing correlation intensity is observed in this area, with samples containing higher water content showing more distinct and stable functions.

Figure 6.

Dynamic light scattering correlation curves at 25 °C for the ternary water/ethanol/n-pentanol system. (a) series Y; (b) series A; (c) series B; (d) series D; (e) series E; (f) series F.

When comparing correlation curves along individual lines, lines A and Y display stronger signals compared to the others, confirming the formation of more stable aggregates near the binodal line. This trend agrees with observations from the previously investigated systems.

The calculated hydrodynamic radii for samples A10, A11, Y10, and Y12 are presented in Table 1, ranging from approximately 32 to 85 nm. The largest radius was recorded for sample A11. These values are consistent with literature data for surfactant-free microemulsions. For example, in the N,N-dimethylformamide/furfural/water system, radii ranging from 40 to 70 nm have been reported, while an ethanol/furfural/water system exhibited a radius of 78.2 nm [26,27]. Liu et al. described aggregates with sizes between 38.5 and 99 nm depending on composition [31]. In the dichloromethane/ethanol/water system, radii around 50 nm were measured, and in systems involving ionic liquids—such as 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate with propylammonium nitrate and water—values around 68 nm have been reported [17,32].

Besides being comparable with literature data, the obtained range of hydrodynamic radii follows the same trend observed in other aqueous surfactant-free microemulsion systems—namely, that increasing the mass fraction of the oil phase results in smaller aggregate sizes [30,33,34]. This dependence is clear from the radius values obtained for the analyzed compositions.

The observed trend can be interpreted within the model proposed by Zemb et al., which states that the stability and size of aggregates in surfactant-free microemulsions arise from a balance between the entropic contribution of mixing and repulsive hydration forces [29]. In systems with longer alkyl chains, such as n-heptanol, the oil domains exhibit a stronger tendency to segregate from the aqueous phase, promoting the formation of compact aggregates with well-defined interfaces. Under such conditions, repulsive hydration forces become significant due to the formation of structured water layers at the interface, which act as an energetic barrier to further aggregate fusion.

2.5. Silica Nanoparticle Synthesis

Although isolated examples of silica nanoparticle synthesis without conventional surfactants exist in the literature, these approaches do not fully meet the criteria of surfactant-free microemulsion (SFME) systems in the strict sense. In one case, the emulsion was stabilized by mechanical agitation, while in another, tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) served as the main oil phase, thereby blurring the distinction between solvent and reactant. In contrast, the work of Sun et al. (2018) remains the only study to date describing the synthesis of silica nanoparticles in a well-defined SFME system composed of water, ethanol, and dichloromethane, in which TEOS was dissolved in the oil phase and hydrolyzed within the droplets [17].

In the present study, silica nanoparticles were chosen as a model system to assess whether SFME systems can act as templates for the synthesis of inorganic nanoparticles. Using identical concentrations of TEOS precursor and ammonium hydroxide catalyst, synthesis was performed in the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system. All selected compositions originated from the oil-in-water (O/W) region of the phase diagram, previously confirmed as structurally stable by DLS measurements.

To interpret the observed particle morphologies and growth behavior, the theoretical basis follows the mechanism proposed by Sun et al. [17]. According to this model, nanoparticle growth in O/W SFME systems proceeds through three stages:

- (I)

- An induction phase, during which water diffuses into the oil droplets and initiates TEOS hydrolysis;

- (II)

- An accelerated growth phase, resulting from coalescence and diffusion of silicate species;

- (III)

- A deceleration phase, as precursor transport becomes limited and the formed particles stabilize.

Although time-resolved analysis was not carried out here, the pronounced difference between aggregate size and final nanoparticle size, along with the homogeneous spherical morphology, suggests a similar growth mechanism.

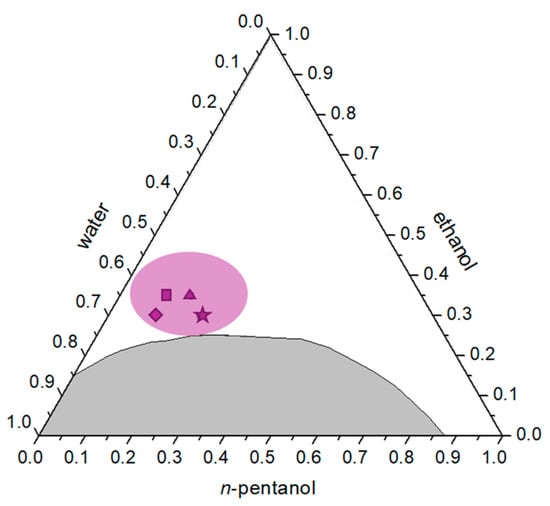

In the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system, synthesis was conducted at four compositions within the O/W region of the phase diagram. Compared with previously investigated systems, the aggregates in this case were slightly larger—ranging from 32 to 85 nm—indicating greater variability among the microemulsion droplets where synthesis occurred. The positions of the selected compositions are shown in the ternary diagram (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Ternary phase diagram of the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system with the region investigated during silica nanoparticle synthesis highlighted in purple. Individual points marked with symbols (★—S9, ◆—S10, ▲—S11, ■—S12) represent the mass fractions of the samples analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The gray area indicates the two-phase region of the system.

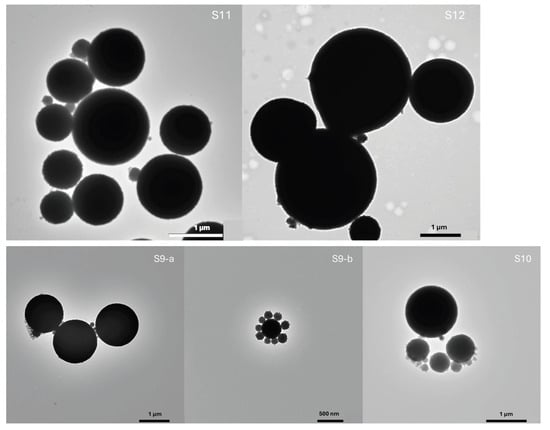

Samples S9–S12 correspond to compositions Y10, Y12, A10 and A11 previously analyzed by DLS. The resulting silica particles exhibited relatively uniform morphology, with a pronounced tendency toward dispersity (Figure 8). The average particle sizes were: S9—950 ± 100 nm; S10—1200 ± 120 nm; S11—1100 ± 100 nm; S12—1150 ± 110 nm. These averages were determined only for particles with clearly defined edges, whereas less-developed or irregular structures were analyzed qualitatively. Sample S9, synthesized in the composition with the highest n-pentanol content, showed both smaller compact particles with slightly irregular edges and well-defined spherical particles exceeding 1 μm in diameter. In sample S10, larger particles dominated, mostly above 1 μm, while smaller ones appeared to be in earlier growth stages. Similar morphologies were observed in samples S11 and S12.

Figure 8.

Transmission electron micrographs of silica particles synthesized in the SFME system water/ethanol/n-pentanol. Sample labels S9–S12 correspond to the compositions shown in Figure 7.

When compared with the n-heptanol system, where silica nanoparticles exhibited well-defined spherical shapes and smaller diameters (≈450–760 nm), the particles formed in the n-pentanol SFME were markedly larger and more polydisperse. This difference is attributed to the weaker phase segregation and higher miscibility of the components in systems containing shorter-chain alcohols, leading to a less rigid aggregate framework and enhanced inter-droplet communication during synthesis. The trend agrees with the behavior described by Zemb et al., in which aggregate stability results from a balance between entropic mixing and repulsive hydration forces [29]. In more hydrophobic systems such as those with n-heptanol, the oil domains segregate more strongly from the aqueous phase, favoring the formation of compact aggregates with well-defined interfaces and, consequently, smaller and more uniform nanoparticles.

A similar phenomenon—where the final particle size significantly exceeds the dimensions of the initial microemulsion aggregates—has also been reported for conventional microemulsion systems. Finnie et al. demonstrated that particle growth is not limited to the droplet interior and that inter-droplet interactions and diffusion of reactants play a decisive role [35]. In such systems, microemulsion droplets act as dynamic nanoreactors, enabling both initial nucleation and subsequent particle growth beyond individual aggregates. Comparable behavior has been observed in polymerization within surfactant-free microemulsions, where the final polymer structures retain morphological features of the original microemulsion template, though expanded to larger dimensions [36,37].

Although the present study focuses on inorganic silica nanoparticles rather than polymer systems, the observed relationship between final morphology and initial microemulsion aggregates can be interpreted analogously. Such behavior is particularly characteristic of SFME systems containing shorter-chain alcohols, where the aggregates are less stable and more sensitive to compositional changes. During synthesis, additional ethanol generated as a by-product of TEOS hydrolysis further destabilizes the microemulsion structure. As a result, the oil component is released from the aggregates, TEOS diffuses into the continuous phase, and a heterogeneous mixture forms, lacking well-defined droplet boundaries. Synthesis under such conditions yields irregularly shaped silica particles with poorly defined edges and increased dispersity.

These interpretations are consistent with the findings of Abarkan et al., who emphasized the crucial role of precursor (TEOS) distribution within the system prior to reaction in determining the final particle morphology. In SFME systems where the TEOS distribution is non-uniform and the aggregate structure is dynamic and sensitive, the synthesis may lead to locally condensed, morphologically undefined structures rather than uniformly developed particles [38].

Compared with the reference Stöber method, the SFME-based approach demonstrates greater flexibility in achieving a broad range of particle sizes—including particles exceeding 1 μm—but with an increased tendency toward dispersity and morphological heterogeneity [39,40]. Unlike the homogeneous reaction media employed in Stöber syntheses, particle growth in SFME systems depends strongly on the internal dynamics and stability of the microemulsion template. Although sol–gel methods offer good reproducibility and straightforward control over particle size, synthesis within SFME systems provides the potential to obtain more complex and structurally diverse particles, albeit requiring careful optimization of reaction conditions [41].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

The following chemicals were used for the preparation of microemulsions: n-pentanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany, ≥99%), ethanol (Honeywell, Seelze, Germany, ≥99.8%), and ultrapure water obtained using an Elga Purelab Flex water purification system. All chemicals employed in the preparation of the systems were pre-filtered through 0.20 μm pore-size membranes (Chromafil Xtra PTFE, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) using disposable syringes.

For the synthesis of silica nanoparticles in microemulsions, ammonium hydroxide (Thermo Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA, ω = 25%) and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, Sigma-Aldrich, ≥99%) were used. These reagents were used without prior filtration.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Construction of the Phase Diagram

The phase diagram for the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system was constructed using the visual titration method. Mixtures with varying ratios of n-pentanol and ethanol were prepared in glass vials, followed by the gradual addition of ultrapure water under continuous stirring until turbidity appeared. The onset of turbidity marked the transition from the single-phase to the two-phase region within the ternary system.

All measurements were conducted at 25 °C, with temperature maintained using a thermostated water bath. After a short equilibration period, the phase boundary was clearly observed as the samples became transparent again. The procedure was repeated three times at the same temperature to ensure reproducibility. Based on the average mass fractions of the components, a binodal curve was plotted using the Origin softwarePro 8 package.

3.2.2. Electrical Conductivity Measurements

Electrical conductivity measurements were carried out at (25 ± 0.02) °C using an Orion immersion cell (model 018001) equipped with two platinum electrodes. The cell was connected to a high-precision Wayne-Kerr electrical component analyzer (model 6430A). The sample resistance (R) was measured at four different frequencies: 500, 800, 1000, and 2000 Hz.

Mixtures with varying mass ratios of n-pentanol and ethanol were prepared directly in a glass reaction cell, which was sealed with a Teflon cap and immersed in a Thermo-Haake circulating thermostat. After temperature stabilization, initial resistance measurements were performed. Subsequently, a known mass of ultrapure water was added to the cell using a syringe, and the sample was briefly homogenized using a submerged magnetic stirrer. After homogenization, resistance values were recorded for all tested compositions. To correct for electrode polarization, the resistance values at different frequencies were analysed as a function of f−1. The polarization-free resistance R0 was obtained from the extrapolation to f−1 → 0, and conductivity was calculated as:

3.2.3. Surface Tension Measurements

Surface tension was determined using a digital tensiometer K10T (Krüss, Hamburg, Germany), equipped with a platinum plate PL21, following the Wilhelmy plate method. A series of samples with increasing mass fractions of n-pentanol were prepared while maintaining a constant ethanol-to-water ratio. Each sample was poured into the instrument’s measurement cell and thermostatted at 25 °C prior to measurement.

The standard Gibbs free energy of aggregation (ΔG°) was estimated from the composition-dependence of surface tension using the approach previously applied to structurally analogous surfactant-free microemulsion systems [28]. The onset of aggregation was identified from the inflection point of the γ(x) curve, which was treated as an associative equilibrium. Under these assumptions, ΔG° was obtained from the simplified thermodynamic expression:

where x denotes the mole fraction at the aggregation onset. The uncertainty in ΔG° arises from the instrumental resolution of surface tension (±0.001 mN m−1) and the compositional accuracy of sample preparation.

ΔG° = RT ln x

3.2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Particle size distribution was determined using a 3D-DLS spectrometer (LS Instruments, Fribourg, Switzerland) equipped with a 35 mW He–Ne laser (λ = 632.8 nm), precision beam splitters, and lenses for focusing and collimation. Samples were placed in light-scattering cuvettes and immersed in a thermostatted bath filled with a fluid of matching refractive index (decalin), maintaining a stable temperature of 25 °C.

Measurements were performed in 3D cross-correlation mode. For each sample, at least 15 measurements of 30 s each were collected, and the autocorrelation function was determined based on the averaged data. The 15 consecutive runs were used solely to obtain the averaged autocorrelation function for cumulant analysis, and individual hydrodynamic radii were not calculated for each run.

3.2.5. Synthesis of Silicon Dioxide Nanoparticles

Silicon dioxide nanoparticles were synthesized following the procedure described by Sun et al. [17]. A series of water and ethanol mixtures with varying ratios was prepared, followed by the precise addition of n-pentanol to the system. The resulting mixtures were magnetically stirred for one hour at 25 °C to achieve a homogeneous microemulsion structure.

Subsequently, a defined volume of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) was added dropwise to the system, and the reaction mixture was further stirred for one hour at the same temperature. Finally, 25% aqueous ammonia solution was gradually introduced to enable controlled hydrolysis and condensation of silicon dioxide. The reaction proceeded for 24 h at 25 °C, and the resulting nanoparticles were separated by centrifugation and washed with ethanol to remove residual impurities.

3.2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

The obtained nanoparticle powder was dispersed in ethanol and sonicated for 10–15 min to achieve a uniform suspension. The prepared suspensions were deposited onto copper grids for transmission electron microscopy analysis and allowed to dry and stabilize for several hours.

TEM analysis was performed using a JEOL JEM-1400 Flash transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operating at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. Transmission electron micrographs were used to determine the average particle size. Particle diameters were measured manually using the instrument software by drawing measurement lines across the largest dimension of each particle. For each sample, 30–50 particles were analyzed on at least three micrographs taken from different grid areas. The obtained values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the ternary system water/ethanol/n-pentanol to elucidate the formation, stability, and potential application of surfactant-free microemulsions (SFMEs). Through systematic experimental characterization, the key factors governing the microstructural organization and functionality of these systems as potential nanoreactors for silicon dioxide synthesis were identified. The constructed phase diagram revealed a clear influence of the alkyl chain length on the width and shape of the single-phase region. The shorter-chain n-pentanol enhanced miscibility and expanded the single-phase region. This indicates that higher polarity of shorter alkanols reduces phase segregation tendencies but may also decrease structural definition. Electrical conductivity measurements provided insight into transitions within the internal organization—from isolated polar domains to progressively connected aggregated structures. The n-pentanol system exhibited gradual, diffuse reorganization, lacking the pronounced percolation transition observed in systems containing longer-chain alcohols. These findings highlight the role of chain length in establishing stable structures with well-defined pathways for ionic transport. Surface tension measurements and the calculated standard Gibbs free energies of aggregation (ΔG°) further supported these observations: systems containing longer-chain alcohols displayed lower (more negative) ΔG° values, reflecting a thermodynamically stronger tendency for aggregation. The observed decrease in ΔG° with increasing alkyl chain length is consistent with the model proposed by Zemb et al., which explains aggregation in SFME systems as a balance between mixing entropy and repulsive hydration forces. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis showed an increase in hydrodynamic radius with decreasing alkyl chain length, corresponding to weaker hydration repulsion and the formation of larger, more flexible aggregates. Ethanol plays a multifaceted role as an interfacial mediator, dynamically participating in both polar and nonpolar domains. Finally, exploratory syntheses of silicon dioxide nanoparticles confirmed that SFME systems can function as dynamic nanoreactors. The stability of aggregates during reaction critically affected product morphology: systems with longer-chain alcohols produced well-defined, compact particles, whereas the n-pentanol system yielded more heterogeneous and polydisperse structures, attributed to lower aggregate stability and enhanced component miscibility during synthesis.

Overall, these results provide deeper insight into the self-organization mechanisms of surfactant-free systems and demonstrate their potential as adaptable media for functional material synthesis. The choice of the third component—the alkanol—proves to be a decisive factor in controlling the structure, stability, and reactivity of such systems.

Although the present study offers a detailed characterization of the water/ethanol/n-pentanol system, certain aspects warrant further exploration. The structural interpretation remains based on ensemble-level observables, which cannot directly visualize the transient spatial organization of aggregates or the early stages of particle formation. Future work employing cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) or molecular dynamics simulations could provide molecular-scale images of both aggregate morphology and the temporal evolution of structures during silica nanoparticle synthesis, helping to clarify the key factors governing particle nucleation and growth. Such approaches would extend, rather than alter, the conclusions presented here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., A.P. and P.B.; Methodology, J.C., A.P. and P.B.; Software, M.T. and J.C.; Formal analysis, M.G., I.H. and M.T.; Investigation, M.G., M.K., I.H. and M.T.; Resources, P.B.; Data curation, M.G. and J.C.; Writing—original draft, M.G., M.K. and P.B.; Writing—review & editing, A.P.; Supervision, P.B.; Funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.T. and J.C. acknowledge the support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding no. P1-0201 and project no. N1-0308 “Nanoplastics in aqueous environments: structure, migration, transport and remediation”). M. Gudelj thanks CEEPUS for the grants CIII-SI 1312-2122-152741 in the frame of the network Water—a common but anomalous substance that has to be taught and studied.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Prince, L.M. Microemulsions versus Micelles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1975, 52, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K.; Moulik, S.P. Microemulsions: An Overview. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 1997, 18, 301–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masahiko, A. Macro- and Microemulsions. J. Jpn. Oil Chem. Soc. 1998, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solans, C.; García-Celma, M.J. Surfactants for Microemulsions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 2, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Pan, N.; Li, D.; Liu, S.; Sun, B.; Chai, J.; Li, D. Formation Mechanism of Surfactant-Free Microemulsion and a Judgment on Whether It Can Be Formed in One Ternary System. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 437, 135385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkowska, E.; Polkowska, Z.; Namieśnik, J. Analytics of Surfactants in the Environment: Problems and Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5667–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Dai, S.; Lu, H. Surfactant-Free Microemulsion Based on CO2-Induced Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 9024–9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cui, Y.; Wang, R.; Shi, Z.; Wu, C.; Li, D. Mesoporous La-Based Nanorods Synthesized from a Novel IL-SFME for Phosphate Removal in Aquatic Systems. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 624, 126689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, J.; Touraud, D.; Prévost, S.; Diat, O.; Zemb, T.; Kunz, W. Influence of Additives on the Structure of Surfactant-Free Microemulsions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 32528–32538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jing, J.; Li, X.; Yue, W.; Qi, J.; Wang, N.; Lu, H. CO2-Responsive Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent Based on Surfactant-Free Microemulsion-Mediated Synthesis of BaF2 Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2023, 39, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Meng, S.; Wang, X.; Peng, C.; Yin, T. Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Natural Product Matrine and Caprylic Acid: Physical Properties, Cytotoxicity and Formation of Surfactant Free Microemulsion. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 90, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjali; Pandey, S. Formation of Ethanolamine-Mediated Surfactant-Free Microemulsions Using Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents. Langmuir 2024, 40, 2254–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, V.; Muller, L.; Degot, P.; Touraud, D.; Kunz, W. NADES-Based Surfactant-Free Microemulsions for Solubilization and Extraction of Curcumin from Curcuma Longa. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkas, H.; Rokade, A.; Upasani, D.; Pardhi, N.; Rokade, A.; Sali, J.; Patole, S.P.; Jadkar, S. Pioneering Method for the Synthesis of Lead Sulfide (PbS) Nanoparticles Using a Surfactant-Free Microemulsion Scheme. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 4352–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkas, H.S.; Marathe, D.M.; Mahajan, M.S.; Muntaser, F.; Patil, M.B.; Tak, S.R.; Sali, J.V. Synthesis of Tin Monosulfide (SnS) Nanoparticles Using Surfactant Free Microemulsion (SFME) with the Single Microemulsion Scheme. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Song, M.; Chai, J. Preparation of Nano-TiO2 by a Surfactant-Free Microemulsion-Hydrothermal Method and Its Photocatalytic Activity. Langmuir 2019, 35, 9255–9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Chai, J.; Chai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cui, X.; Lu, J. A Surfactant-Free Microemulsion Consisting of Water, Ethanol, and Dichloromethane and Its Template Effect for Silica Synthesis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 526, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudelj, M.; Kranjac, M.; Jurko, L.; Tomšič, M.; Cerar, J.; Prkić, A.; Bošković, P. Structure and Potential Application of Surfactant-Free Microemulsion Consisting of Heptanol, Ethanol and Water. Colloids Interfaces 2024, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Wani, M.Y.; Hashim, M.A. Microemulsion Method: A Novel Route to Synthesize Organic and Inorganic Nanomaterials. Arab. J. Chem. 2012, 5, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tojo, C. The Interplay between Nucleation and the Rates of Chemical Reduction in the Synthesis of Bimetallic Nanoparticles in Microemulsions: A Computer Study. Metals 2024, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkin, T.; Gotić, M. Mikroemulzijska Sinteza Nanočestica. Kem. Ind. 2013, 62, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Lisiecki, I.; Pileni, M.P. Synthesis of Copper Metallic Clusters Using Reverse Micelles as Microreactors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3887–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, M.S.Z.; Henderson, W.; Mucalo, M.R. A Review of The Lesser-Studied Microemulsion-Based Synthesis Methodologies Used for Preparing Nanoparticle Systems of The Noble Metals, Os, Re, Ir and Rh. Materials 2019, 12, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Gao, F.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; You, H.; Du, Y. A Review of the Role and Mechanism of Surfactants in the Morphology Control of Metal Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 3895–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othmer, D.F.; White, R.E.; Trueger, E. Liquid-Liquid Extraction Data. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1941, 33, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Hou, W.-G. A Novel Surfactant-Free Microemulsion System: N,N-Dimethylformamide/Furaldehyde/H2O. Chin. J. Chem. 2008, 26, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Hou, W.-G. A Novel Surfactant-Free Microemulsion System: Ethanol/Furaldehyde/H2O. Chin. J. Chem. 2008, 26, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, P.; Sokol, V.; Zemb, T.; Touraud, D.; Kunz, W. Weak Micelle-Like Aggregation in Ternary Liquid Mixtures as Revealed by Conductivity, Surface Tension, and Light Scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 9933–9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemb, T.N.; Klossek, M.; Lopian, T.; Marcus, J.; Schöettl, S.; Horinek, D.; Prevost, S.F.; Touraud, D.; Diat, O.; Marčelja, S.; et al. How to Explain Microemulsions Formed by Solvent Mixtures without Conventional Surfactants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4260–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klossek, M.L.; Touraud, D.; Zemb, T.; Kunz, W. Structure and Solubility in Surfactant-Free Microemulsions. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13, 4116–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Deng, H.; Song, J.; Hou, W. A Surfactant-Free Microemulsion Composed of Isopentyl Acetate, N-Propanol, and Water. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Deng, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, W. Surfactant-Free Microemulsions of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate, Propylamine Nitrate, and Water. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 2067–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krickl, S.; Touraud, D.; Bauduin, P.; Zinn, T.; Kunz, W. Enzyme Activity of Horseradish Peroxidase in Surfactant-Free Microemulsions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 516, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, M.; Chai, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, J. Preparation, Characterization and Application of a Surfactant-Free Microemulsion Containing 1-Octen-3-Ol, Ethanol, and Water. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 300, 112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnie, K.S.; Bartlett, J.R.; Barbé, C.J.A.; Kong, L. Formation of Silica Nanoparticles in Microemulsions. Langmuir 2007, 23, 3017–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blahnik, J.; Krickl, S.; Schmid, K.; Müller, E.; Lupton, J.; Kunz, W. Microemulsion and Microsuspension Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate in Surfactant-Free Microemulsions (SFME). J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 648, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blahnik, J.; Schuster, J.; Müller, R.; Müller, E.; Kunz, W. Surfactant-Free Microemulsions (SFMEs) as a Template for Porous Polymer Synthesis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 655, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarkan, I.; Doussineau, T.; Smaïhi, M. Tailored Macro/Microstructural Properties of Colloidal Silica Nanoparticles via Microemulsion Preparation. Polyhedron 2006, 25, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogush, G.H.; Tracy, M.A.; Zukoski, C.F. Preparation of Monodisperse Silica Particles: Control of Size and Mass Fraction. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 1988, 104, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourebrab, M.A.; Oben, D.T.; Durand, G.G.; Taylor, P.G.; Bruce, J.I.; Bassindale, A.R.; Taylor, A. Influence of the Initial Chemical Conditions on the Rational Design of Silica Particles. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2018, 88, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.A.; Padavettan, V. Synthesis of Silica Nanoparticles by Sol-Gel: Size-Dependent Properties, Surface Modification, and Applications in Silica-Polymer Nanocomposites A Review. J. Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 132424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).