Abstract

The global reliance on coal-fired power generation continues to produce vast quantities of fly ash, exceeding 500 million tons annually, with limited recycling rates. Given its high silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3) contents, fly ash represents a promising alternative raw material for sustainable refractory production. In this study, four aluminosilicate refractory castables were formulated using bauxite, calcined flint clay, kyanite, calcium aluminate cement, and microsilica, in which the fine fraction of flint clay was partially replaced by 0, 5, 10, and 15 wt.% fly ash. The specimens were dried at 120 °C and sintered at 850, 1050, and 1400 °C for 4 h. Their physical and mechanical properties were systematically evaluated, while phase evolution and microstructural development were analyzed through X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The results revealed that the incorporation of 10 wt.% fly ash (10FAC) provided the optimal balance between densification and strength, achieving compressive strengths of 45.0 MPa and 65.3 MPa after sintering at 1050 °C and 1400 °C, respectively. This improvement is attributed to the formation of a SiO2-rich liquid phase derived from fly ash impurities, which promoted the in-situ crystallization of acicular secondary mullite and enhanced interparticle bonding among corundum grains. The 10FAC castable also exhibited only a slight increase in apparent porosity (26.39%) compared with the reference (25.74%), indicating effective sintering without excessive vitrification. Overall, the study demonstrates the technical viability of using fly ash as a sustainable substitute for flint clay in refractory castables. The findings contribute to advancing circular economy principles by promoting industrial waste valorization and resource conservation, offering a low-carbon pathway for the development of high-performance refractory materials for structural and thermal applications in energy-intensive industries.

1. Introduction

Urbanization, industrialization, and modernization—driven by the global demand for improved living standards—have led to a substantial increase in resource consumption and waste generation [1,2,3,4]. One major consequence is the exponential growth in global electricity demand, which, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), continues to rely predominantly on coal-fired thermal power plants [5,6]. A by-product of coal combustion in these facilities is fly ash (FA), a fine particulate residue that poses significant environmental challenges due to its high production volume and complex chemical composition.

The physicochemical characteristics of fly ash—such as particle morphology, size distribution, and density—depend primarily on factors including the type of coal burned, combustion temperature, and cooling conditions [7,8]. Typically consisting of hollow or solid microspheres ranging from 1 to 200 µm, with densities between 1.1 and 1.78 g/cm3, fly ash is rich in silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3), making it a valuable secondary raw material for construction and ceramic applications [9,10].

According to ASTM C618 (2003) [11], fly ash is classified as either Class C or Class F. Class C ash, derived from sub-bituminous or lignite coal, contains 50–70 wt.% of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 combined, along with significant CaO and MgO contents. In contrast, Class F ash—produced from bituminous or anthracite coal—contains more than 70 wt.% of these oxides but less than 10 wt.% CaO, with only trace amounts of alkali oxides [7,9].

Although global fly ash recycling rates have improved in recent years—reaching 30–50% in certain regions—these values remain low relative to the more than 500 million tons generated annually. The majority of unrecycled fly ash is still disposed of in landfills, posing risks to soil, air, and groundwater quality [8,10]. Some developed nations have adopted progressive waste valorization policies to mitigate this issue. For example, China has implemented green industrial strategies emphasizing low emissions and high efficiency [12]; Russia aims to recycle at least 50% of fly ash by 2035; and Germany enforces strict landfill bans, achieving near-100% recycling rates, particularly within the construction sector [7,13].

Historically, fly ash was primarily employed as an inert microfiller in construction materials, helping to improve packing density and reduce environmental impact through partial raw-material substitution [14]. However, since the 1980s, recognition of its pozzolanic reactivity and favorable mineralogical composition has broadened its utilization as a secondary raw material, particularly in the production of Portland cement substitutes, geopolymers, glazed ceramic tiles, ceramic fibers, and insulating refractories [3,15,16]. Nonetheless, certain high-value applications—such as catalysts and zeolites—require extensive pretreatment, limiting their economic feasibility [2,5].

Consequently, there remains a strong need to identify cost-effective, technologically viable, and sustainable uses for fly ash. Among the most promising approaches is its incorporation into refractory castables, offering opportunities for both resource efficiency and enhanced performance. Notably, Škamat et al. (2024) reported that replacing calcined clay with fly-ash cenospheres (3–7 wt.%) in medium-cement refractory castables improved thermal-shock resistance, alkali resistance, and optimized porosity and phase development (mullite, cristobalite, and glassy phases) [6]. Despite these promising findings, the use of fly ash as a full or partial replacement for fine aggregates in dense refractory castables remains largely unexplored.

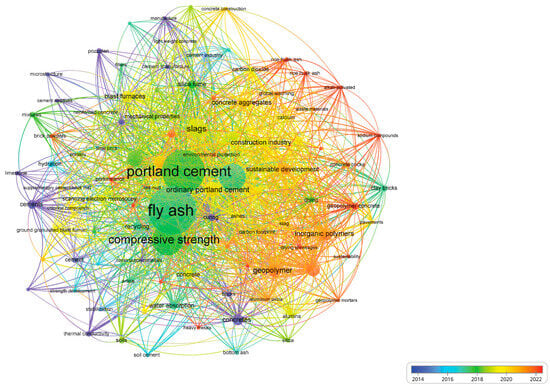

Figure 1 presents a bibliometric analysis conducted using VOSviewer (v1.6.20) based on 120 relevant publications, revealing the limited research attention given to sustainable refractory castables. Given their critical role in the production of metals, glass, cement, and ceramics, the optimization of refractory castables is essential—not only to enhance durability and energy efficiency but also to minimize environmental impact [17,18,19,20,21].

Figure 1.

Co-occurrence network obtained from the literature’s bibliometric analysis on the main applications for fly ash recycling.

Table 1 summarizes how fly ash has been used in refractory materials according to recent literature. We selected representative studies that cover different refractory chemistries (mullite, anorthite–mullite, forsterite–spinel, fireclay/firebrick and others) and summarized them according to role/amount of fly ash, sintering temperature, effects on physical/mechanical/thermal/chemical properties, microstructural/phase evolution after heat treatment.

Table 1.

Comparative applications of fly ash in refractory materials. “FA” = fly ash.

Fly ash is chemically versatile: high-Al2O3 fly ashes are excellent precursors for mullite ceramics, whereas FA with significant SiO2 can act as silica source for forsterite/spinel systems when combined with Mg sources. The FA class (F vs. C) and impurity profile (CaO, alkalis, Fe2O3) strongly determine whether FA will promote mullite formation, liquid-phase sintering, or undesirable low-melting phases [22].

Typical sintering for mullite-rich materials ranges 1400–1600 °C (needle growth, mullite percolation) while forsterite/spinel systems require 1400–1550 °C with added Mg sources. Liquid-phase sintering from FA glass can lower required firing temperatures but may reduce refractoriness and chemical resistance if excessive [23].

Percolated mullite networks (needle-like crystals) provide excellent high-temperature dimensional stability and creep resistance. Preservation of cenospheres can reduce density and thermal conductivity (useful for insulating refractories), whereas the formation of excessive residual glass or low-melting phases can degrade high-temperature load-bearing performance [22].

Fly ash enables cost-effective manufacture of insulating bricks, mullite components, forsterite/spinel refractories and lightweight kiln furniture, but variability of FA composition and the need for beneficiation or additives (Al2O3, MgO, coating) are recurring limitations that must be addressed for reproducibility and industrial scale-up [24].

In recent years, several studies have focused on reducing the high CaO content in conventional and medium-cement castables—often associated with the formation of low-melting-point phases within the Al2O3–SiO2–CaO system—by incorporating nano-additives or geopolymer-based binders [29,30,31,32,33]. However, these alternatives are frequently limited by low green strength, insufficient mechanical performance at intermediate temperatures, and high sensitivity to water-to-cement ratios and curing parameters [34,35,36].

Given that the construction industry consumes nearly 50% of the world’s natural raw materials and generates approximately half of global industrial waste, the integration of secondary raw materials into refractory formulations is not only desirable but also essential for sustainable development [37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Conventional and medium-cement refractory castables—typically regarded as less advanced than ultra-low or no-cement systems—represent an accessible and cost-effective option, particularly when designed for low-to-moderate-temperature applications such as biomass-fueled boilers. Biomass boilers operating below 1100 °C can effectively utilize lower-cost castables composed of fired clay, mullite, and quartz, where the presence of quartz promotes the formation of a protective glassy phase that enhances resistance to alkali corrosion [6,44].

Building upon these considerations, this work investigates the role of fly ash as a sus-tainable alternative to flint clay in aluminosilicate refractory castables. The crystallographic, microstructural, and physicomechanical study of the impact of flint clay substitution with fly ash in a silicoaluminous refractory castable will contribute to establishing the mechanisms and phenomena associated with the development of new properties in these innovative and sustainable refractories. It is hypothesized that the incorporation of fly ash as a partial replacement for flint clay promotes the formation of a SiO2-rich liquid phase during sintering, enhancing mullite crystallization and improving interparticle bonding. These effects are expected to result in refined microstructures, reduced defect density, and mechanical and thermal performances comparable to or superior to those of conventional commercial refractory castables.

In pursuit of a more sustainable approach to refractory design, this study seeks to evaluate the physicomechanical, crystallographic, and microstructural characteristics that contribute to the correlation and understanding of the new properties developed in a silicoaluminate refractory castable incorporating fly ash as a partial substitute for flint clay.

To fulfill this goal and ensure a systematic evaluation of the proposed formulation, the study focused on the following specific objectives:

- (i)

- To investigate the microstructural development and morphology of fly-ash-containing castables through scanning electron microscopy (SEM/EDS), establishing correlations between the morphology of secondary mullite crystals, phase distribution, and the mechanical response of the material.

- (ii)

- To determine the influence of fly ash addition on the physical and mechanical properties—including bulk density, apparent porosity, cold crushing strength, and modulus of rupture—across different sintering temperatures, identifying the optimal substitution ratio for improved performance.

- (iii)

- To assess the potential of fly ash as a sustainable raw material for the production of high-performance refractory castables, evaluating its effects on sintering behavior, densification, and compatibility with traditional refractory formulations.

- (iv)

- To establish correlations between the microstructural features and property development of fly-ash-modified refractories, contributing to the understanding of the mechanisms governing their enhanced mechanical integrity and thermal stability.

In this context, this research supports the advancement of circular economy strategies by demonstrating the technical feasibility of incorporating industrial by-products such as fly ash into refractory castable formulations. By partially substituting natural flint clay with this waste-derived material, the study not only reduces the consumption of virgin raw materials but also provides an environmentally responsible pathway for managing industrial residues. The approach aligns with green manufacturing practices aimed at minimizing embodied energy and carbon emissions in refractory production. Ultimately, the outcomes of this investigation contribute to the broader goal of developing next-generation sustainable refractories that integrate waste valorization with high-temperature performance requirements for industrial applications such as biomass combustion systems (e.g., wood-burning boilers).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

A silicoaluminous conventional refractory castable was formulated using widely employed raw materials supplied by AP Green (Salinas Victoria, Nuevo León, Mexico), including calcined flint clay, calcined Guayanese bauxite, kyanite (48% Al2O3), calcium aluminate cement (Secar 80), and microsilica. Flint clay is a dense aluminosilicate refractory primarily composed of silica (~50 wt.% SiO2) and alumina (~45 wt.% Al2O3), with minor Fe2O3 and trace amounts of alkali oxides. Its compact microstructure, conchoidal fracture, and high hardness provide excellent resistance to abrasion, corrosion, and thermal shock. In refractory castables, flint clay serves as a high-performance aggregate, contributing to mechanical integrity and long-term stability under harsh thermal and chemical exposure. Guyanese bauxite, renowned for its high purity and consistency, typically contains ≥88 wt.% Al2O3, ≤6 wt.% SiO2, and around 1 wt.% Fe2O3, though composition may vary by deposit. Owing to its low impurity content, this material provides an exceptionally reactive alumina source, ensuring high refractoriness and favorable mullite crystallization during firing. Kyanite (−48 mesh), an aluminosilicate mineral (Al2SiO5), is valued for its elongated crystal morphology, which enhances mechanical strength and thermal shock resistance in refractory systems. Upon heating, kyanite transforms into mullite, accompanied by a volume expansion of approximately 15–18%, which helps offset clay shrinkage and maintain dimensional stability. Secar 80, a high-purity calcium aluminate cement (~80 wt.% Al2O3), exhibits a controlled phase composition with minimal free lime and crystalline silica. It provides rapid strength development, excellent chemical resistance, and superior refractoriness, making it a preferred binder for advanced refractory formulations. Finally, microsilica—a by-product rich in amorphous SiO2 consisting of submicron spherical particles—improves particle packing and reduces water demand in castables. Its high pozzolanic reactivity facilitates in-situ mullite formation and the development of secondary bonding phases, which together lead to a denser microstructure, lower porosity, and enhanced mechanical and thermal performance. Moreover, the reuse of microsilica from industrial processes supports circular economy and sustainable manufacturing practices.

To enhance the sustainability of the refractory formulation, finely ground fly ash particle size ≤ 75 µm, obtained by mechanical sieving) was incorporated as a secondary raw material. The fly ash, sourced from coal-fired thermal power plants, represents a calcined aluminosilicate by-product primarily composed of silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3), with minor contents of Fe2O3, CaO, and alkaline oxides. Its glassy matrix and spherical particle morphology promote dense packing, improved particle dispersion, and optimized rheology in castable systems. Mineralogically, fly ash contains crystalline phases such as mullite, quartz, and hematite, embedded in an amorphous aluminosilicate network, which contributes to the development of reactive bonding phases during sintering. The partial substitution of fine aggregates with fly ash enhances microstructural densification, thermal shock resistance, and dimensional stability at elevated temperatures, owing to its ability to form mullite and glassy sealing phases under heat treatment. Beyond its technical benefits, the valorization of fly ash significantly reduces the dependence on virgin raw materials, diverts industrial waste from landfills, and lowers the carbon footprint associated with refractory production. Consequently, fly ash serves not only as a technically viable raw material but also as a sustainable substitute that aligns with circular economy principles and advances cleaner production strategies for high-temperature ceramic applications. The fly ash used in this study was supplied by the José López Portillo Thermoelectric Plant (Nava, Coahuila, Mexico), selected for its chemical purity and consistent particle size distribution, making it suitable for high-performance refractory formulations.

The chemical composition of all raw materials, including fly ash, was determined via X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using a Panalytical MagiX PW2424 X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectrometer (Philips, Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK). Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Raw materials and by-product’s chemical composition (wt.%).

The phase composition of the fly ash was further analyzed by Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a PIXcel 1D detector (Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) and Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) was used, operating at 40 kV and 45 mA. The scan was conducted over a 2θ range of 10–90° with a step size of 0.05° and a dwell time of 1.5 s per step in continuous mode. Phase identification was carried out using Crystallographic Open Database (COD) reference cards. The resulting diffraction pattern—discussed in a subsequent section—provides insight into the relative proportions of crystalline and amorphous constituents. This characterization was essential for understanding their reactivity and contribution to the microstructural evolution of the refractory castable.

2.2. Refractory Formulation and Specimen Preparation

A reference formulation was adopted from the work of López-Perales et al. (2021) [45], consisting of calcined flint clay, bauxite, kyanite (48% Al2O3), Secar 80 cement, and microsilica. Three modified formulations were developed by partially replacing the fine fraction of flint clay with 5, 10, and 15 wt.% fly ash, respectively, to evaluate the potential of fly ash as a sustainable alternative raw material in conventional castable compositions.

Table 3 summarizes the detailed composition of each refractory mixture, including aggregate and additive contents, particle size distributions, binder ratios, and the corresponding water demand to ensure adequate workability.

Table 3.

Conventional and green refractory castable designed batch compositions (wt. %).

The formulations are designated as follows:

- CC: Conventional Castable (reference),

- 5FAC, 10FAC, and 15FAC: Castables containing 5, 10, and 15 wt.% fly ash, respectively.

The substitution levels of 5, 10, and 15 wt.% fly ash were selected based on both prior optimization studies and preliminary experimental trials. Earlier reports on medium-cement aluminosilicate castables incorporating fly ash cenospheres or fine ash fractions indicated beneficial effects at low to moderate additions (3–7 wt.%), mainly in terms of improved sinterability and thermal shock resistance. Building upon these findings, the present work extended the substitution range to higher levels (up to 15 wt.%) to systematically evaluate the transition from beneficial to potentially detrimental effects on densification and mechanical behavior. Preliminary screening tests performed on laboratory batches confirmed that mixtures containing more than 15 wt.% fly ash exhibited excessive water demand and reduced plasticity, compromising workability and green strength. Therefore, the 5–15 wt.% range was selected as an optimal window to capture the compositional threshold where fly ash contributes to phase formation and microstructural enhancement without impairing processing performance.

For specimen preparation, each batch was dry-mixed in a conventional mortar mixer for 3 min. Water was then added in accordance with ASTM C860 (2000) [46] to ensure appropriate dispersion, homogeneity, and workability.

The water-to-cement ratio plays a decisive role in the rheological behavior, workability, and overall performance of refractory castables. In general, conventional dense castables require between 8 and 15 wt.% of water relative to the dry material to achieve suitable consistency and flowability, ensuring homogeneous dispersion and good casting behavior (ASTM C860, 2000). Maintaining water content within this range promotes appropriate particle packing and minimizes segregation during mixing and vibration.

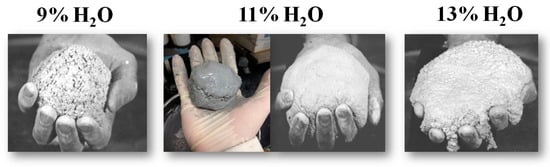

In this study, three different water addition levels—9%, 11%, and 13% by weight—were investigated to determine the optimal ratio that provides adequate fluidity and mechanical stability. The consistency of each mixture was evaluated following the ASTM C860 “Ball-in-Hand” test, which is widely used in industrial refractory installations due to its simplicity and effectiveness in assessing the plasticity and cohesiveness of fresh castables.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the mixture containing 9% water showed a rough surface and poor cohesion, indicating low workability and inadequate dispersion. Conversely, the mixture with 11% water exhibited a uniform texture, excellent consistency, and sufficient flow under vibration, enabling proper mold filling and minimal air entrapment. The mixture with 13% water demonstrated excessive fluidity and poor shape retention, leading to reduced green strength and partial segregation of the finer components.

Figure 2.

The ASTM C860 “Ball-in-Hand” test.

The results confirmed that a 11 wt.% water-to-cement ratio is optimal for this formulation, ensuring both good castability and mechanical integrity in the green state. This balance is essential to produce defect-free specimens with the precise geometry required for subsequent thermal and mechanical testing.

It is well established that inappropriate water content can critically affect refractory performance. Excessive water reduces mechanical strength, increases drying shrinkage, and promotes microcracking, while insufficient water limits fluidity, hinders compaction, and may result in incomplete hydration reactions or trapped air voids. Therefore, careful control of the water-to-cement ratio is fundamental to optimizing the fluidity, density, and mechanical performance of refractory castables, directly influencing their service life under high-temperature conditions.

The optimal water addition of 11 wt.% provides a suitable balance between workability and mechanical performance, enabling proper compaction under vibration without segregation or cracking during drying. This ratio ensures a dense microstructure after sintering, resulting in enhanced mechanical strength, thermal shock resistance, and durability. Therefore, it represents a technically viable and industrially applicable formulation for vibratable refractory castables used in steelmaking, cement, and ceramic industries.

Wet mixing was carried out for 4 min before casting the mixtures into pre-lubricated acrylic molds. A thin layer of petroleum-based mineral oil (commercially known as Vaseline), composed mainly of saturated hydrocarbons, was applied to facilitate demolding. The molds had dimensions of 50 × 50 × 50 mm for compressive strength testing and 25 × 25 × 150 mm for flexural strength testing. The cast specimens were vibrated for 3 min using a CONTROLS 55-C0160/Hz vibrating table (CONTROLS S.p.A., Milan, Italy) to eliminate entrapped air. The molds were then sealed with plastic film and stored under laboratory conditions for 24 h to prevent moisture loss during curing. After demolding, the specimens were dried at 120 °C for 24 h, followed by heat treatments at 850, 1050, and 1400 °C, using a Thermo Scientific Heratherm drying oven (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and a Thermo Scientific Lindberg Blue M/1700 electric furnace (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. The heating rate was maintained at 170 °C/h, and specimens were soaked for 4 h at each target temperature. Subsequently, the samples were cooled inside the furnace to room temperature in accordance with ASTM C865 (2002) [47].

2.3. Characterization Techniques

The physical properties—bulk density, apparent porosity, and water absorption—were determined at each firing temperature using the boiling water method and Archimedes’ principle in accordance with ASTM C20 (2000) [48]. Six specimens per formulation and temperature were tested, and average values with standard deviations were reported.

Mechanical performance was evaluated by measuring the cold crushing strength (CCS) and flexural strength using an ELE-International hydraulic universal testing machine (ELE International, Leighton Buzzard, UK), with a maximum capacity of 250 kN. CCS was determined using cubic specimens at a loading rate of 31.2 kN/min, while the flexural strength was assessed via three-point bending on rectangular prism specimens at a loading rate of 0.774 kN/min, following ASTM C133 (1997) [49]. Results were reported as mean values ± standard deviation, based on six replicates.

Phase identification was conducted by X-ray diffraction (XRD) on samples fired at each target temperature. A Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a PIXcel 1D detector (Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) and Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) was used, operating at 40 kV and 45 mA. Scans were performed over a 2θ range of 10–90°, with a step size of 0.05° and a dwell time of 1.5 s per step in continuous mode. Phase identification was achieved using Crystallographic Open Database (COD) reference patterns.

Microstructural analysis of specimens fired at 1400 °C was carried out using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on a JEOL JSM-6510LV microscope (JEOL, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) coupled with an EDAX Apollo X EDS system (EDAX, Inc., Mahwah, NJ, USA). Prior to SEM observation, samples were cold-mounted in epoxy resin and progressively polished using silicon carbide abrasive papers (grits: 80 to 4000) and diamond suspensions (9, 3, and 1 µm). Finally, specimens were gold-coated using a Quorum Q150R ES sputter coater (Quorum Technologies Ltd., located in East Sussex, UK) to ensure surface conductivity.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characterization of Raw Materials and Fly Ash

As was observed, Table 2 presents the chemical composition of the raw materials and the fly ash by-product incorporated into the sustainable refractory formulations. The fly ash is primarily composed of SiO2 and Al2O3, with minor amounts of Fe2O3, CaO, TiO2, and K2O. Given its combined content of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 (~90 wt.%), and a CaO content below 10 wt.%, the material is classified as Class F fly ash, typically derived from the combustion of anthracite or bituminous coal [7,10].

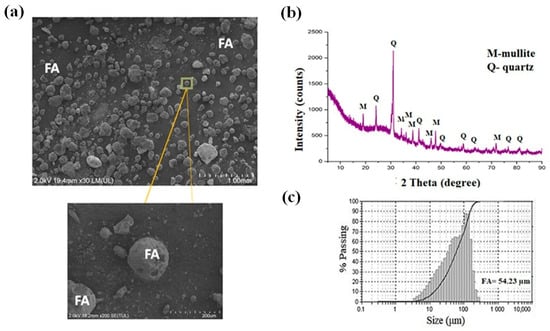

Figure 3 displays the morphology using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern, and particle size distribution of the fly ash (FA). The morphology of the fly ash analyzed by SEM, and its micrographs obtained at 2000× magnification are presented in Figure 3a. As observed, this material exhibits predominantly spherical particles, which result from its formation process during combustion. The presence of cenospheres, a characteristic feature of fly ash, can be clearly seen with particle sizes ranging from approximately 2 µm to 90 µm.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM micrograph of fly ash (FA) particles at 2000× magnification, showing predominantly spherical morphology and the presence of cenospheres with particle sizes ranging from 2 µm to 90 µm. (b) XRD pattern of fly ash, evidencing a high amorphous fraction (halo between 2θ = 10–35°) and the presence of crystalline phases of m = mullite and q = quartz. (c) Particle size distribution curve of fly ash, showing a median particle diameter (D50) of approximately 54.23 µm.

Figure 3b displays the mineralogical composition of the fly ash determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The diffractogram reveals a high amorphous content, evidenced by the broad diffuse halo observed in the approximate 2θ range of 10–35°. This confirms the existence of a glassy silicoaluminous phase. The main crystalline phases identified in the diffraction pattern correspond to quartz (SiO2; 2θ = 20.83°, 26.61°, and 50.10°; PDF 01-078-1252) and mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2; 2θ = 16.41°, 25.97°, 33.21°, 35.27°, 40.86°, and 60.70°; PDF 00-015-0776). The significant content of refractory oxides (SiO2 and Al2O3) in crystalline (mullite, quartz) and amorphous forms suggests that fly ash is a suitable candidate to partially replace conventional refractory raw materials such as flint clay.

Figure 3c presents the particle size distribution of the fly ash, which exhibits an average particle sizes (D50) of approximately 54.23 µm, confirming its fine particulate nature and typical granulometric profile of coal combustion residues. The d50 of the fly ash (FA) was evaluated by a laser diffraction granulometry method (HORIBA laser model LA-950, Irvine, CA, USA).

3.2. Crystalline Phase Analysis of Refractory Specimens

3.2.1. Reference Composition (CC)

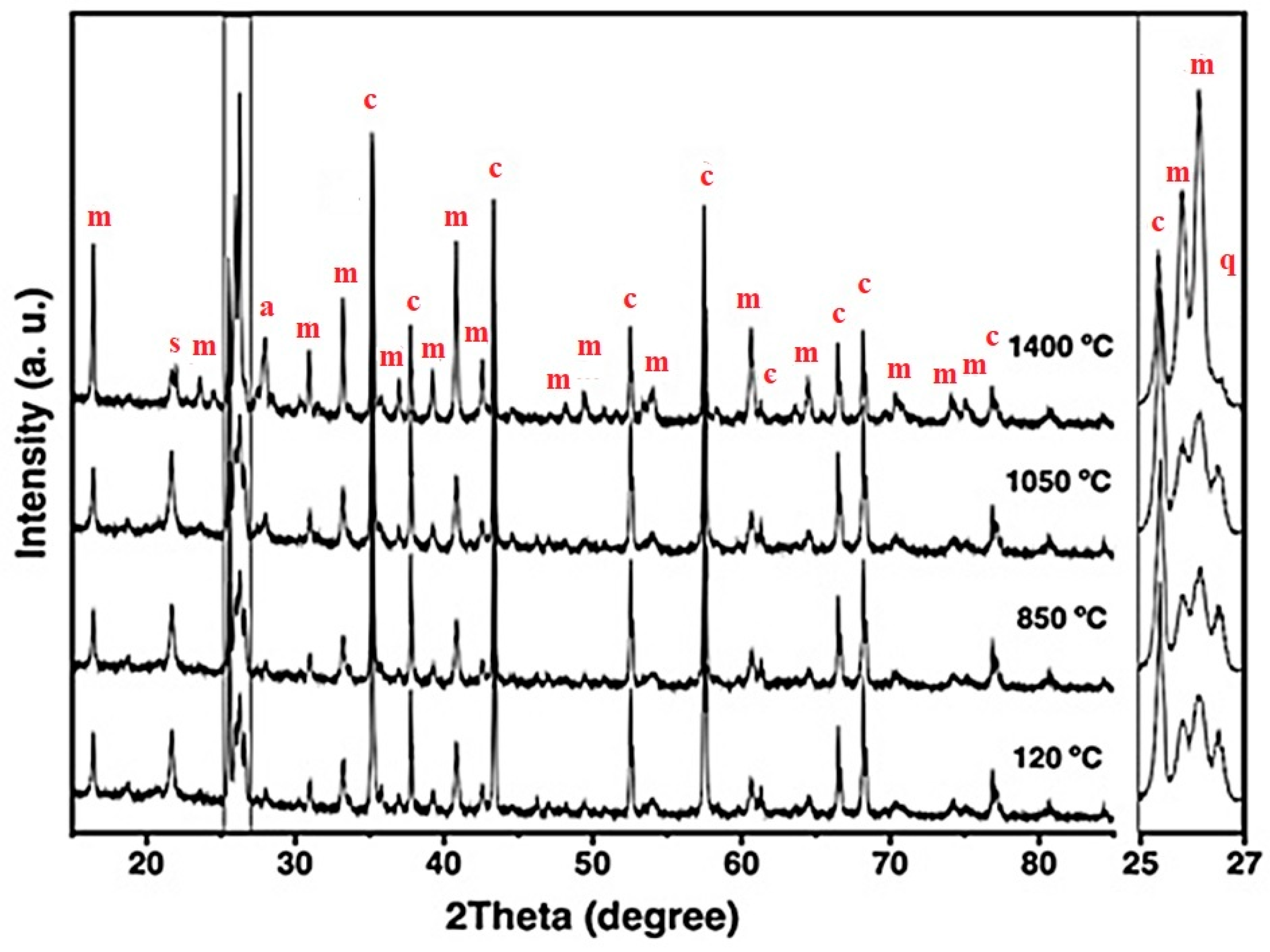

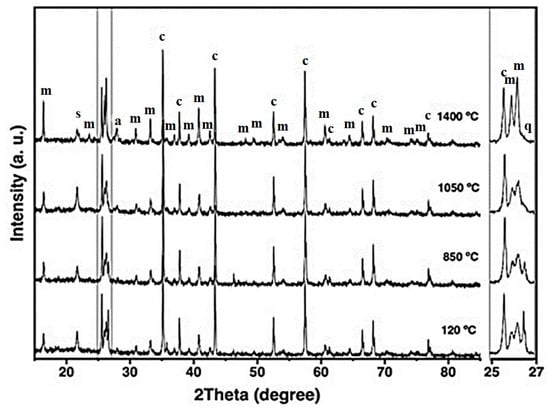

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of the CC refractory specimen across increasing firing temperatures. At 120 °C, the detected crystalline phases include mullite, corundum, cristobalite, and quartz—corresponding to the mineral constituents of the starting raw materials [6,21]. As the firing temperature increases to 850 °C, the intensities of cristobalite and quartz reflections decrease, and at 1050 °C, quartz peaks disappear completely (notably between 25–27° 2θ). This behavior indicates the progressive transformation of quartz into cristobalite and, to some extent, mullite, involving both structural and volumetric modifications [30,50,51].

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the CC refractory specimen obtained at different temperatures, where m = mullite, c = corundum, s = cristobalite, q = quartz, and a = anorthite.

At 1400 °C, a marked increase in the intensity of mullite reflections is observed, accompanied by a reduction in corundum and cristobalite peaks and the appearance of anorthite. The formation of primary mullite is attributed to the decomposition of kaolinitic clay, whereas secondary mullite likely formed through solid-state reactions and partial dissolution of Al2O3 within a metastable eutectic liquid phase [4,30,51,52].

According to Liu et al. (1994) [52], in the kaolinite–alumina system at temperatures up to 1700 °C, secondary mullite can develop through three principal mechanisms: (i) solid-state interdiffusion between alumina and silica particles, leading to direct mullite crystallization; (ii) dissolution of alumina into a metastable eutectic liquid that forms at temperatures ≥ 1260 °C, followed by mullite precipitation from this transient melt; or (iii) dissolution of alumina into a silica-rich liquid phase containing alkali impurities, particularly K2O, which can reduce the eutectic temperature to approximately 980 °C, thereby promoting mullite crystallization from the liquid phase [52].

These mechanisms underscore the influence of temperature, phase composition, and alkali oxide content on mullite formation—factors that critically determine the thermal stability and high-temperature performance of alumina–silica-based refractory castables.

Given the low K2O concentration in the CC refractory formulation (~0.30 wt.%), the development of secondary mullite is most plausibly attributed to a combination of solid-state diffusion between Al2O3 and SiO2 particles and partial dissolution of alumina in a metastable, silica-rich eutectic liquid. This liquid likely originated from CaO released during the decomposition of hydrated calcium aluminate cement phases. The coexistence of CaO and SiO2 under high-temperature conditions also favored the crystallization of anorthite, consistent with previous reports [6,18,45,53,54].

Table 4 summarizes the quantitative phase analysis of the refractory specimens based on the relative intensities of diffraction peaks obtained after firing at 1400 °C. The results indicate that the reference refractory primarily consists of corundum and mullite, with minor amounts of cristobalite and anorthite detected.

Table 4.

Crystalline phase content in refractory formulations at the temperature of 1400 °C.

3.2.2. Fly Ash-Modified Compositions

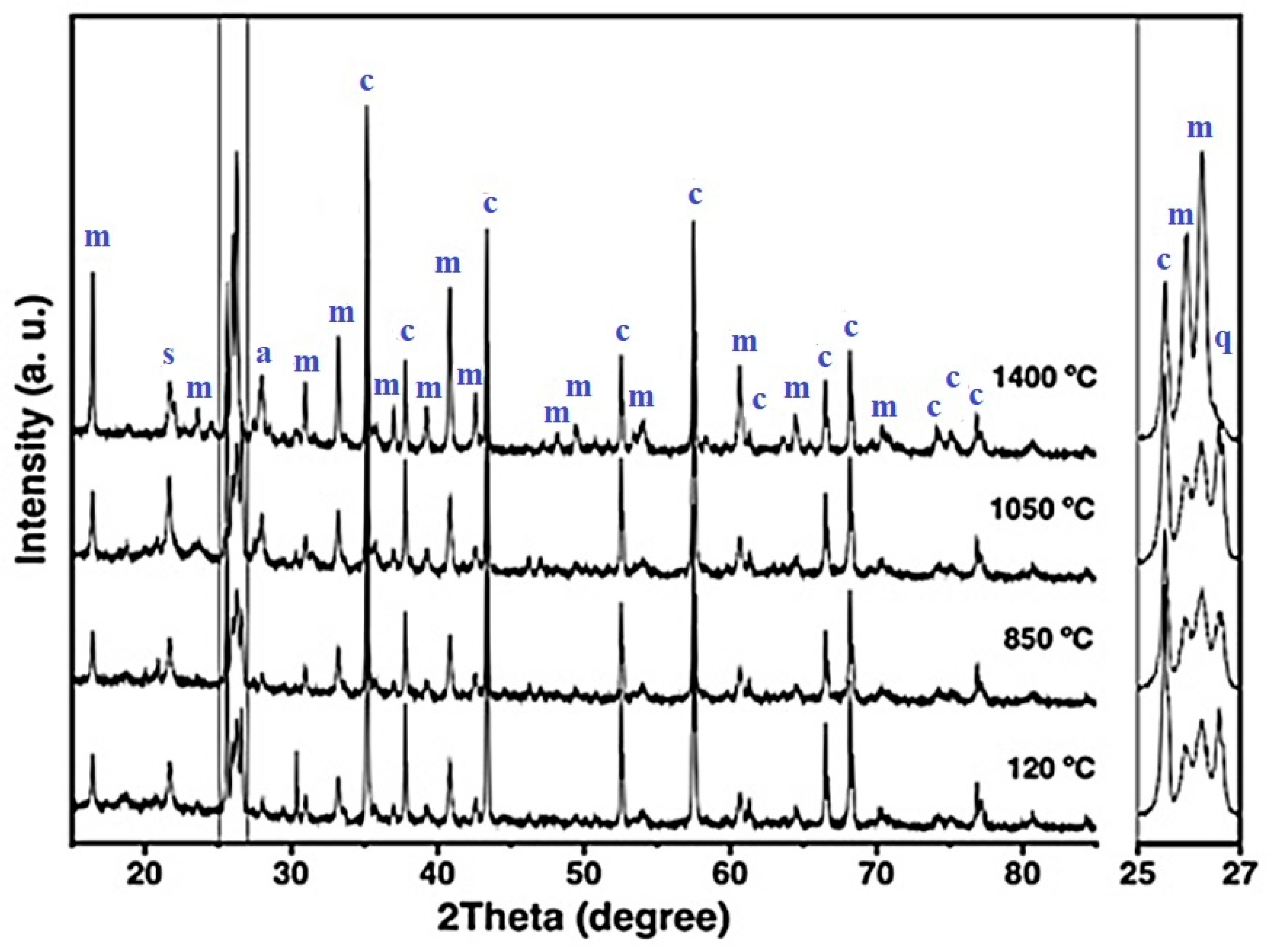

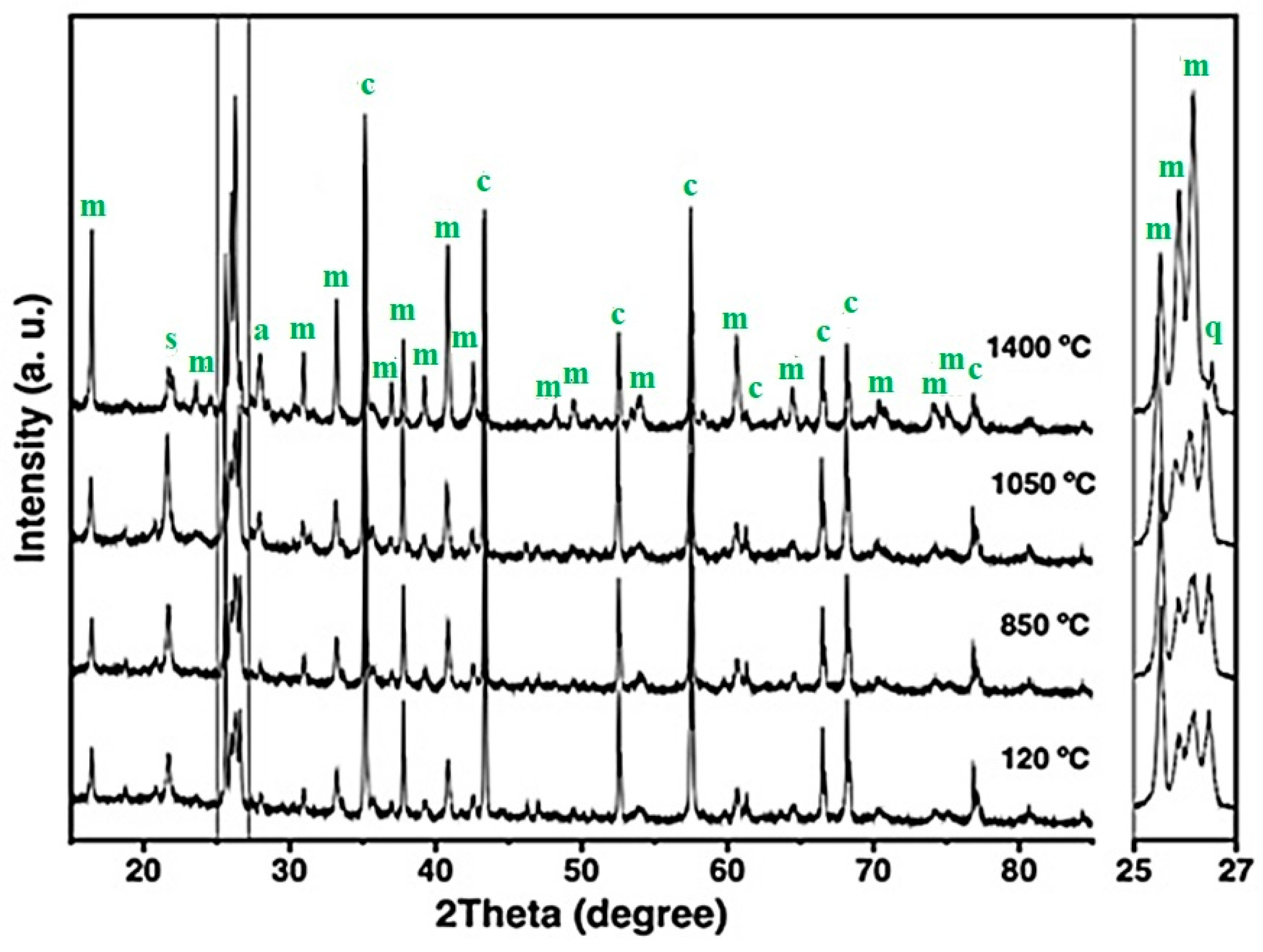

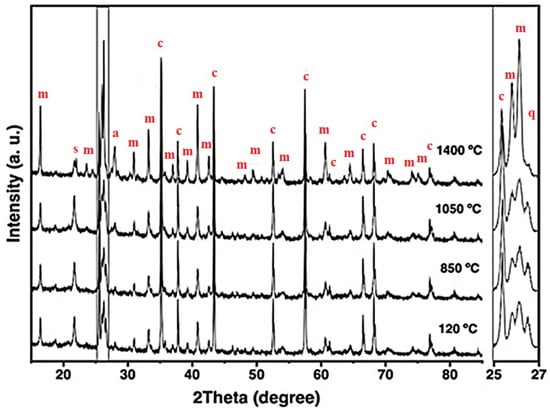

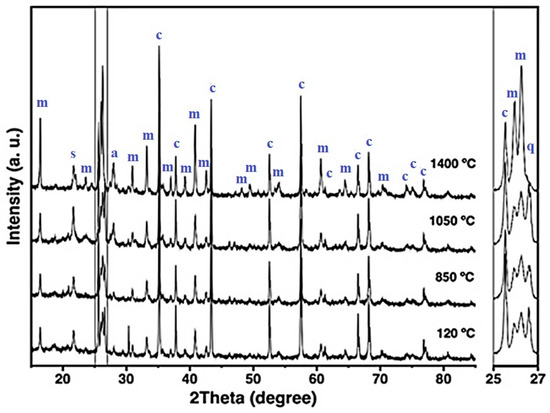

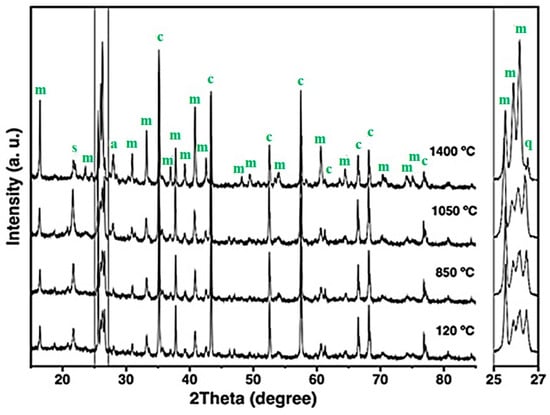

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the XRD patterns of the fly ash–containing refractory specimens—5FAC, 10FAC, and 15FAC—across increasing firing temperatures. At 120 °C, the diffractograms of all three formulations exhibit a broad halo within the 2θ range of 10–30°, characteristic of the amorphous phase associated with the incorporated fly ash (as also observed in Figure 3b). This amorphous region corresponds to a silica-rich or silicoaluminous glassy phase commonly reported in thermoelectric fly ash residues [6,9]. In addition to this amorphous contribution, crystalline phases such as mullite, corundum, cristobalite, and quartz were identified in all fly ash–modified formulations at this low firing temperature, indicating minimal mineralogical transformation prior to sintering.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the 5FAC refractory specimen obtained at different temperatures, where m = mullite, c = corundum, s = cristobalite, q = quartz, and a = anorthite.

Figure 6.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the 10FAC refractory specimen at different temperatures, where m = mullite, c = corundum, s = cristobalite, q = quartz, and a = anorthite.

Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the 15FAC refractory specimen at different temperatures, where m = mullite, c = corundum, s = cristobalite, q = quartz, and a = anorthite.

The XRD patterns of the 5FAC and 10FAC specimens fired at 850 °C closely resemble that of the CC reference composition. However, a distinct reduction in the intensity of cristobalite and quartz reflections is observed, suggesting partial transformation or dilution of these silica phases. In contrast, the 15FAC specimen exhibits a different behavior: the intensity of the quartz reflection remains nearly unchanged (see magnification in the 2θ range of 25–27°), while a slight increase in the cristobalite peak is detected. This phenomenon can be attributed to an excess of SiO2 in the system, both in its crystalline forms (quartz and cristobalite) and amorphous content derived from microsilica and fly ash additions [10,50]. Furthermore, both the 10FAC and 15FAC compositions show a slight decrease in the intensity of corundum reflections, particularly in the 2θ region between 37–40°, which may indicate partial interaction between Al2O3 and the silica-rich phase.

At 1050 °C, the XRD patterns of the fly ash–containing refractory specimens display a notable increase in the intensity of mullite reflections, accompanied by the emergence of low-intensity anorthite peaks. The formation of in-situ secondary mullite and anorthite at this intermediate temperature is attributed to the presence of a silica-rich liquid phase containing CaO and minor impurities such as K2O, TiO2, and Fe2O3, originating from both the raw materials and the incorporated fly ash [29,34,54,55]. These impurities likely facilitated partial alumina dissolution and subsequent nucleation of these crystalline phases.

In the 5FAC specimen, the quartz reflection remains relatively stable at this temperature, whereas an increase is observed in the 10FAC and 15FAC compositions. This trend, together with the general rise in cristobalite intensity across all fly ash–modified specimens, suggests progressive crystallization of the amorphous silica fraction. Such transformation likely arises from contributions of both microsilica and fly ash, confirming the siliceous character of the latter [6,30,31].

At 1400 °C, the intensity of mullite reflections increases significantly in the fly ash–containing specimens, surpassing that of the reference composition without fly ash. This enhanced mullite formation is accompanied by a pronounced reduction in corundum, cristobalite, and quartz peaks, indicating that Al2O3 reacted with SiO2 and CaO—derived from both raw materials and cement hydrates—in the presence of a silica-rich liquid phase. This liquid, enriched with impurities such as K2O, TiO2, and Fe2O3 (see Table 2), promoted in-situ crystallization of secondary mullite and the concurrent formation of anorthite.

The mechanism of secondary mullite formation at elevated temperatures (~980 °C) is consistent with the dissolution–precipitation process proposed by Liu et al. (1994) [52], in which alumina dissolves into a transient silica-rich liquid phase and subsequently recrystallizes as mullite. The incorporation of fly ash increases the impurity content and overall reactivity of the system, thereby facilitating this phase transformation [18,34,52,56].

According to Table 4, the phase composition of the 5FAC specimen sintered at 1400 °C closely resembles that of the reference (CC) composition, except for its higher mullite content. In contrast, the 10FAC and 15FAC specimens exhibit not only greater amounts of mullite but also increased cristobalite content, reflecting enhanced silica crystallization. Moreover, the 15FAC composition retains residual quartz, as evident in the magnified region between 25° and 27° 2θ. The persistence of quartz, particularly at high firing temperatures, may adversely affect the physical and mechanical properties of the refractory by promoting thermal instability and microstructural heterogeneity [35].

3.3. Physical Properties

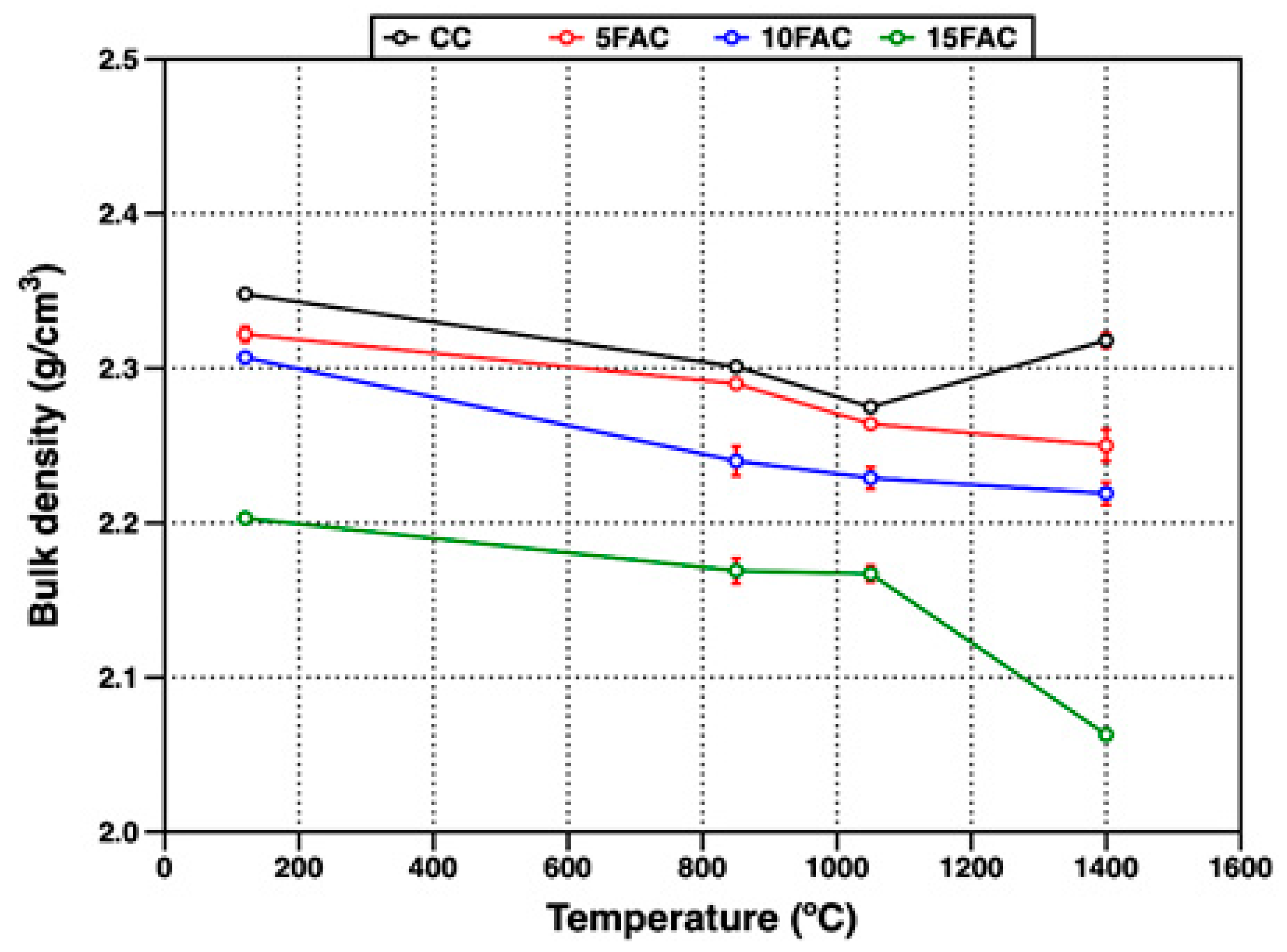

3.3.1. Bulk Density

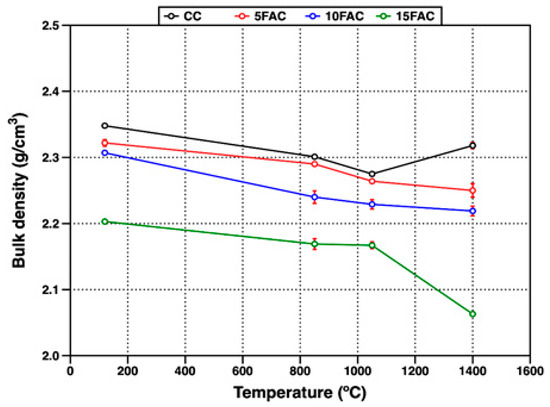

Figure 8 shows the evolution of bulk density in the refractory specimens as a function of firing temperature. At 120 °C, the reference composition (CC) exhibited the highest bulk density (2.34 g/cm3). In contrast, all fly ash–containing formulations displayed lower bulk density values, which progressively decreased with increasing fly ash content [6]. This reduction can be attributed to the partial replacement of denser raw materials, such as flint clay (density 1.99–2.70 g/cm3), with fly ash—a by-product characterized by substantially lower bulk densities (typically 1.01–1.78 g/cm3, depending on origin and processing) [10,57,58]. The incorporation of this lighter material decreases overall packing efficiency and mass per unit volume of the castable matrix.

Figure 8.

Bulk density of refractory specimens at different temperatures.

In refractory castables, initial particle bonding is achieved through the hydraulic setting of calcium aluminate cement upon contact with water, producing metastable hydration products such as CAH10, C2AH8, and amorphous AH3 at ambient temperature [59]. As temperature increases, physically adsorbed and capillary-retained water is gradually released, while the metastable hydrates transform into thermodynamically stable phases—primarily C3AH6 and crystalline AH3 (gibbsite). This dehydration and phase transformation process induces volumetric changes, which are reflected in reduced bulk density, particularly around 850 °C. Additionally, in the 10FAC and 15FAC specimens, this effect is intensified due to the higher quartz content in their formulations. The polymorphic transformation of quartz from α- to β-phase at approximately 573 °C introduces additional volumetric instability, contributing to further microstructural rearrangement and loss of densification [17,19].

As firing temperature increases to 1050 °C, the bulk density of all refractory specimens continues to decrease. However, this reduction is more pronounced in the CC and 5FAC compositions. In contrast, the 10FAC and 15FAC specimens exhibit a more gradual decline, attributed to enhanced crystallization and sintering phenomena occurring at intermediate temperatures. This behavior is promoted by the higher amorphous silica content introduced through fly ash (see Figure 3), which facilitates the formation of a SiO2-rich liquid phase. This liquid phase enhances mass transport, accelerating the dissolution of fine Al2O3 particles and their subsequent reaction to form secondary mullite (see Figure 6 and Figure 7) [60]. The in-situ formation of secondary mullite—characterized by an interlocking, needle-like morphology—contributes to pore closure and improved packing, resulting in a more stable bulk density profile for the 10FAC and 15FAC compositions [54,61,62].

At 1400 °C, only the CC reference specimen exhibited an increase in bulk density, reaching 2.31 g/cm3, although this value remained slightly lower than that measured at 120 °C. The rise in temperature enhanced sintering, promoting stronger ceramic bonding and partial densification of the matrix [60]. In contrast, the fly ash–containing specimens exhibited more complex behavior due to the simultaneous influence of sintering and volumetric changes associated with SiO2 polymorphic transformations. In these formulations, ceramic bonding resulted from both the crystallization of secondary mullite and the formation of anorthite. However, volumetric expansion—especially from the quartz-to-cristobalite transformation—counteracted densification. For the 5FAC and 10FAC specimens, bulk densities of 2.25 g/cm3 and 2.21 g/cm3 were obtained, respectively. Based on their XRD patterns, these results suggest that extended residence time at 1400 °C may be required to promote further mullite growth and microstructural densification through complete mullitization [4,30,31]. In contrast, the 15FAC specimen exhibited a significantly lower bulk density (2.06 g/cm3), indicating that volumetric expansion associated with the transformation of quartz and amorphous silica into cristobalite—reported to cause up to ~17% volume increase—was more dominant than sintering. This observation highlights the critical balance between silica-rich phase transformations and densification during high-temperature treatment of fly ash–containing refractory castables [44,63].

3.3.2. Apparent Porosity and Water Absorption at Low Temperatures

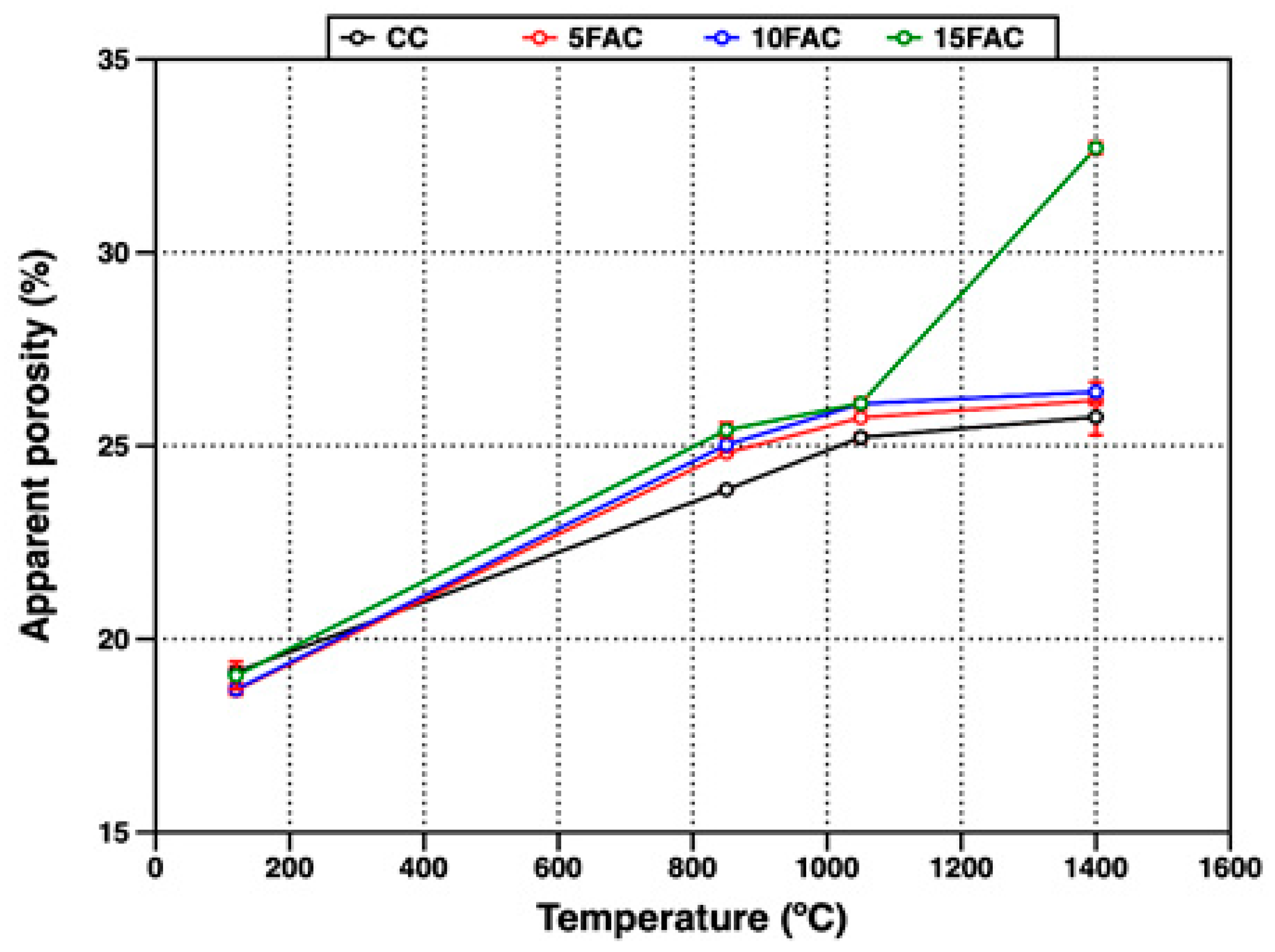

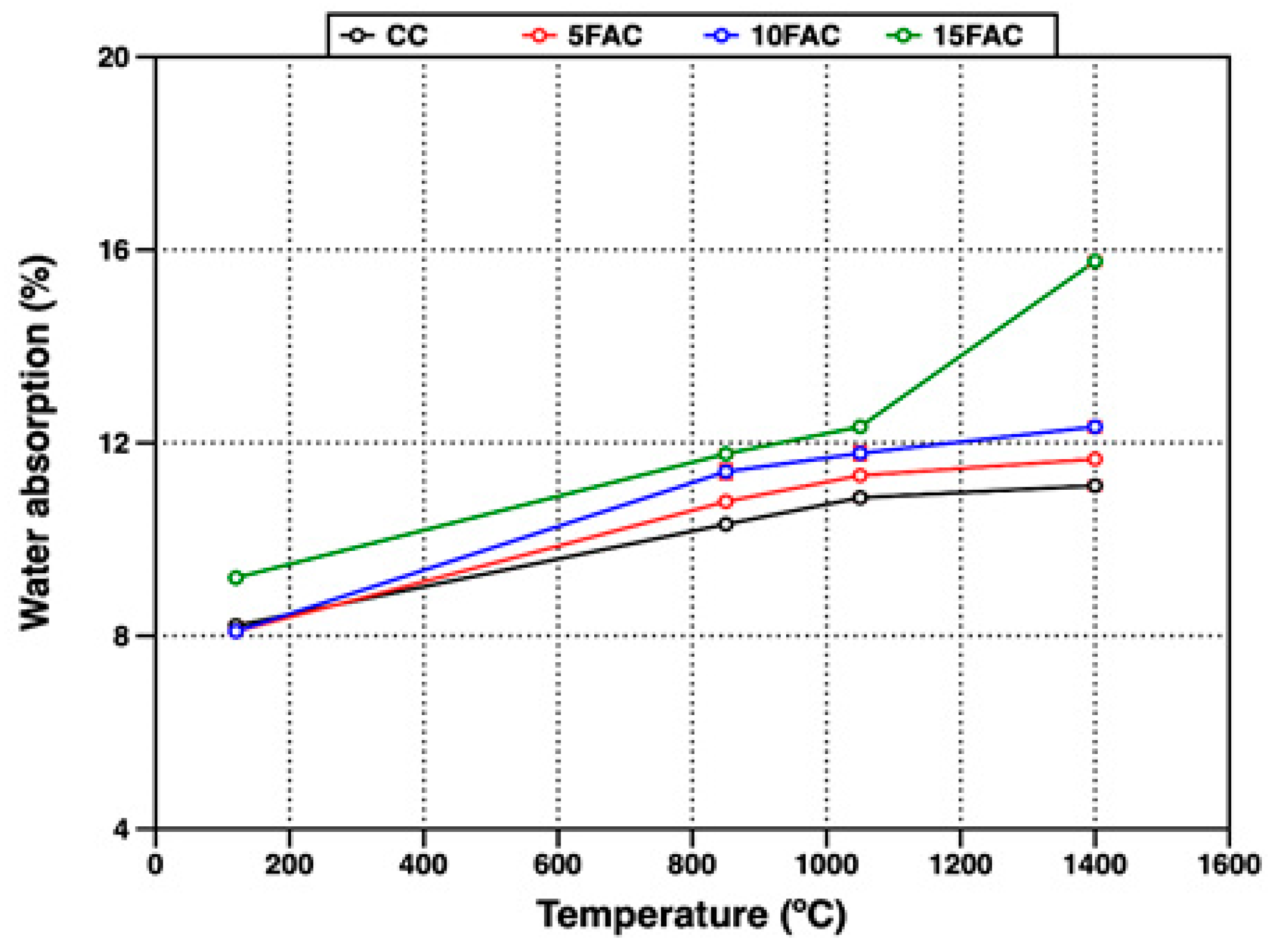

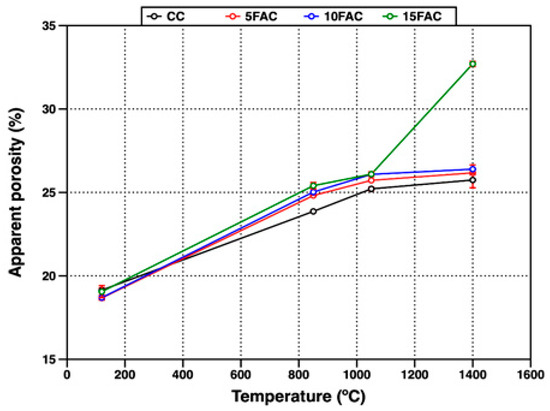

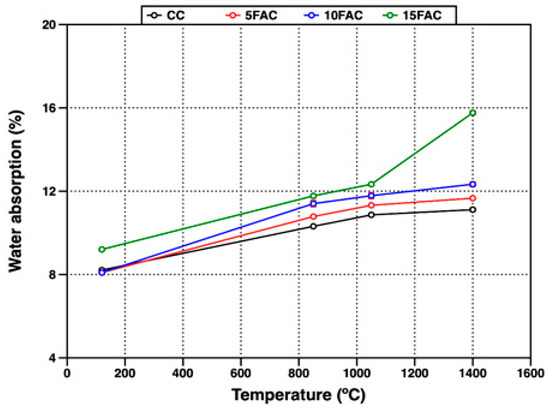

The open porosity of the refractory specimens fired at different temperatures was evaluated through their apparent porosity (AP) and water absorption (WA), as presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively.

Figure 9.

Apparent porosity of refractory specimens at different temperatures.

Figure 10.

Water absorption of refractory specimens at different temperatures.

At 120 °C, the 5FAC specimen exhibited the lowest values, with AP and WA of 18.67% and 8.09%, respectively. In contrast, the 15FAC specimen showed the highest open porosity, with AP of 19.35% and WA of 9.20%. These results are consistent with the higher water content required during the mixing stage for the 15FAC composition, which contained 15 wt.% fly ash (Table 3). The increased water demand is attributed to the finer particle size and higher surface area of fly ash, which promote greater water retention during casting and result in residual porosity after drying and heating [34,64].

3.3.3. Mid-Temperature Phase Transformations (850–1050 °C)

A general increase in both apparent porosity and water absorption was observed in all specimens when the firing temperature reached 850 °C. At this stage, the reference specimen (CC) exhibited the lowest open porosity, as expected, since fly ash–containing mixtures undergo more complex thermal transformations. In the temperature range up to 850 °C, fly ash–based specimens experience dehydration and multiple phase transitions. Between 110 °C and 300 °C, the removal of free and bound water from the AHx gel occurs, accompanied by the decomposition of metastable hydration products such as CAH10 and C2AH8. As the temperature rises to around 370 °C, further decomposition of stable phases including C3AH6 and crystalline AH3 takes place. In parallel, the polymorphic transformation of quartz becomes significant, particularly in specimens with higher fly ash content. Around 573 °C, the allotropic transition from quartz-α to quartz-β produces volumetric expansion, the extent of which is proportional to the quartz content introduced by the fly ash. The combined effects of dehydration and quartz transformation increase internal stresses and pore formation, leading to higher apparent porosity and water absorption [44,50,65,66,67].

At 1050 °C, all refractory specimens exhibited a further increase in open porosity, reflected in both AP and WA. This behavior is mainly attributed to the complete breakdown of the hydraulic bond due to the decomposition of hydration products such as CAH10, C2AH8, and C3AH6. Specifically, the dehydration of C3AH6 yields C12A7, free CaO, and water vapor (Equation (1)), while the decomposition of crystalline AH3 produces boehmite (AlO(OH)) and subsequently amorphous Al2O3 and H2O (Equations (2) and (3)). These transformations, occurring between 850 °C and 1050 °C, disrupt the matrix integrity and contribute to increased porosity.

Despite the increased porosity, beneficial microstructural changes also occur in this temperature range. Notably, the in-situ formation of secondary mullite crystals becomes more evident near 1000 °C. These newly formed needle-like mullite structures strengthen the ceramic bond and partially counteract the porosity increase, thereby improving the long-term thermal performance of the refractory material [17,30,31,53,62].

3.3.4. High-Temperature Behavior and Densification (1400 °C)

At 1400 °C, a slight increase in open porosity was observed in the CC, 5FAC, and 10FAC specimens, with AP values of 25.74%, 26.17%, and 26.39%, and corresponding WA values of 11.11%, 11.66%, and 12.33%, respectively. These results indicate that incorporating up to 10 wt.% fly ash into conventional refractory castables is feasible, as the physical properties remain comparable to those of the reference composition (CC). Moreover, fly ash contributes to the formation of highly refractory phases such as mullite and corundum (Table 4), which can enhance high-temperature performance. However, further optimization may be required to improve densification. Specifically, firing at temperatures above 1400 °C or extending the dwell time at peak temperature could promote matrix densification, thereby reducing porosity and enhancing mechanical strength [6,51]. In contrast, the 15FAC specimen exhibited markedly different behavior, with significantly higher AP (32.70%) and WA (15.76%). This is likely due to the excessive SiO2 content from the higher fly ash loading, which induces undesirable volumetric changes during sintering and compromises the structural integrity of the refractory body [34,50,63].

3.4. Mechanical Properties

3.4.1. Compressive Strength at 120 °C

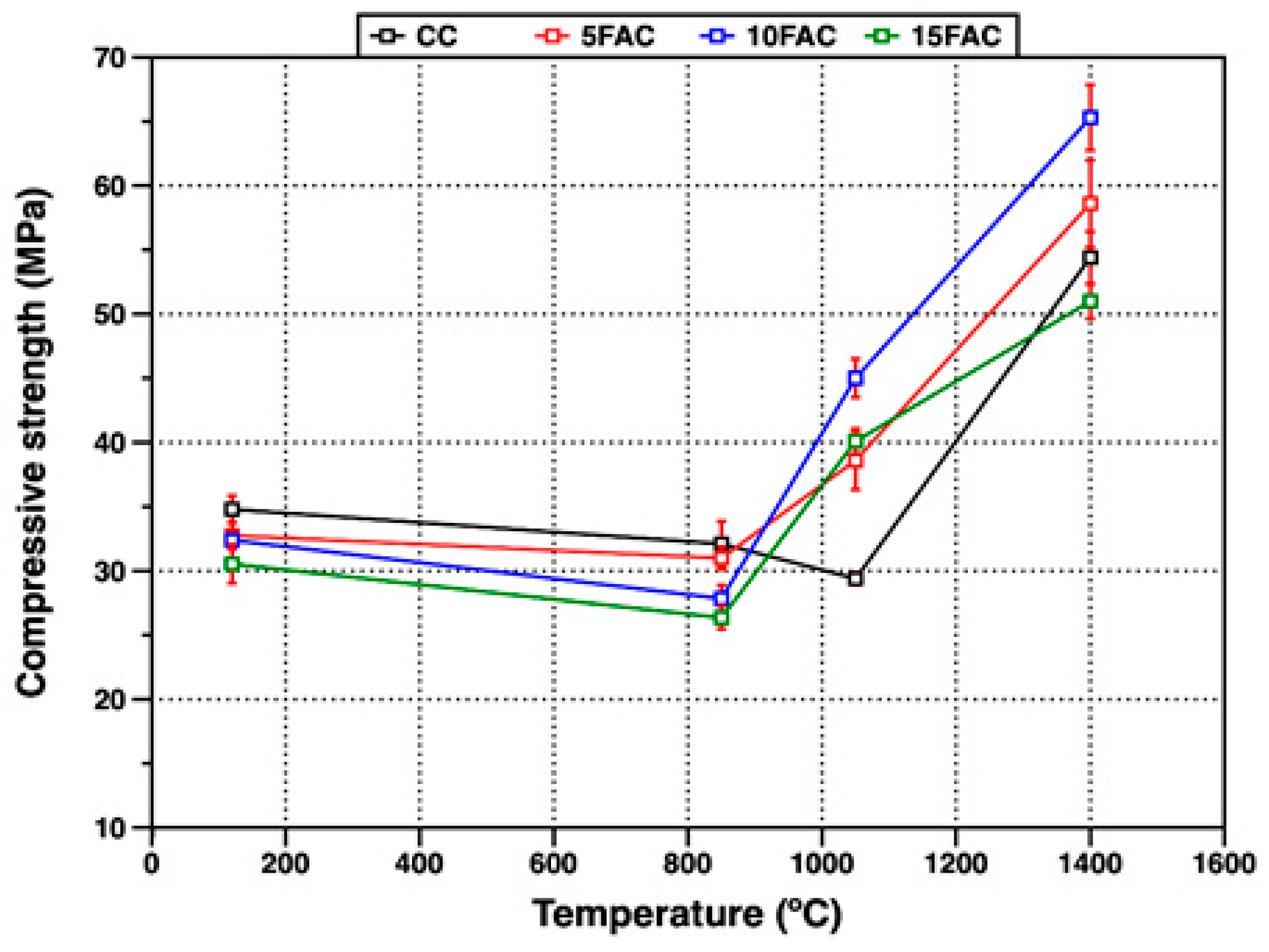

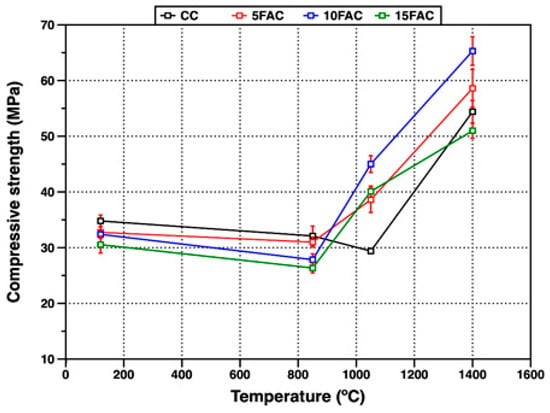

Figure 11 presents the compressive strength values of the refractory specimens at various firing temperatures. At 120 °C, the reference specimen (CC) exhibited the highest compressive strength (34.8 MPa), outperforming all fly ash–containing formulations. This enhanced strength arises from the formation of hydraulic bonds and the precipitation of adhesive hydration gels such as CAH10 and C3AH6, resulting from the reaction between calcium aluminate cement and water. These hydration products bind the solid particles, imparting early mechanical integrity to the structure [33,64]. In contrast, the specimens incorporating fly ash showed lower compressive strength at the same temperature. This reduction can be attributed to the higher water demand of these compositions, likely caused by the finer particle size and higher surface area of the fly ash (Blaine = 3127 cm2/g), as well as its lower intrinsic density compared with the other raw materials [6]. The lowest strength observed for the 15FAC sample (30.5 MPa) confirms the detrimental influence of excessive fly ash content on early-age mechanical performance.

Figure 11.

Compressive strength of refractory specimens at different temperatures.

Mechanical Degradation at 850 °C

At 850 °C, a general decrease in compressive strength was recorded for all refractory specimens. This reduction is primarily due to the breakdown of hydraulic bonds and the decomposition of early-formed hydration products, which increase porosity within the matrix. Furthermore, the partial restructuring and phase transformation of these hydration products contribute to microstructural instability [29,54]. In the fly ash–containing specimens, this deterioration was more pronounced—particularly in the 10FAC and 15FAC formulations. The effect is associated with the higher quartz content in these mixtures (see Figure 6 and Figure 7). During heating, the α → β quartz polymorphic transition near 573 °C causes volumetric expansion, generating internal stresses and microcracks that compromise the structural integrity of the refractory body, leading to reduced compressive strength [50].

Strength Recovery at 1050 °C

At 1050 °C, the reference specimen (CC) exhibited a further decrease in strength, indicating that ceramic bonding was still in its early stages. At this temperature, the thermal energy is insufficient to promote significant particle rearrangement and sintering, resulting in weak neck formation between grains and limited densification [17,64,65]. Conversely, the fly ash–containing compositions (5FAC, 10FAC, and 15FAC) showed a substantial increase in compressive strength, reaching 38.6, 45.0, and 40.1 MPa, respectively. This improvement is attributed to the evolution of mineralogical phases and the onset of ceramic bonding. The enhanced strength results primarily from the in-situ formation of secondary mullite generated through reactions between alumina and a reactive silica-rich melt. The interlocking needle-like morphology of these secondary mullite crystals reinforces the matrix, improving its load-bearing capacity and mechanical integrity [18,54]. However, the presence of free SiO2 must also be considered, since its polymorphic transitions—particularly the α → β quartz transformation—may still induce localized volumetric instability. The superior performance of the 10FAC specimen suggests that this composition achieves an optimal balance between phase evolution and microstructural stability. The formation of secondary mullite likely mitigates the adverse effects of silica expansion by stabilizing the matrix and restricting crack propagation. The mechanical behavior of the fly ash–based formulations at this intermediate temperature aligns with recent approaches aimed at enhancing refractory performance through nano-additives or reactive fillers that promote early sintering and densification. This performance is particularly advantageous for industries operating at moderate service temperatures, such as aluminum, cement, and petrochemical sectors, where improved mechanical strength at intermediate firing temperatures can reduce energy consumption during the manufacture of pre-formed refractory components [29,30,31].

High-Temperature Behavior at 1400 °C

At 1400 °C, the 10FAC specimen exhibited the highest compressive strength (65.3 MPa), followed by the 5FAC (58.6 MPa), CC (54.4 MPa), and 15FAC (51.0 MPa) specimens. The strength of the 10FAC sample represents an improvement of approximately 20% compared with the reference composition, confirming the beneficial effect of incorporating 10 wt.% fly ash in enhancing high-temperature mechanical performance. At this stage, the elevated firing temperature promotes extensive dissolution of alumina into a silica-rich liquid phase containing minor oxides such as CaO, TiO2, and Fe2O3. This reactive environment facilitates the in-situ formation of secondary mullite and anorthite within the refractory matrix [4,6]. The development of interlocking, needle-like mullite crystals together with anorthite formation contributes to a dense, robust ceramic network that strengthens the bonding among corundum grains, significantly improving the mechanical integrity of the refractory body [18,34]. In contrast, the 15FAC specimen—with the highest fly ash content—displayed lower compressive strength. This reduction is mainly attributed to its excessive silica content, which intensifies volumetric changes associated with SiO2 polymorphic transitions, particularly the α → β quartz transformation. These transitions induce internal stresses and microcracking, increasing porosity within the matrix and at the aggregate–matrix interface. Consequently, the structural cohesion of the refractory body is compromised, leading to the observed loss of mechanical strength.

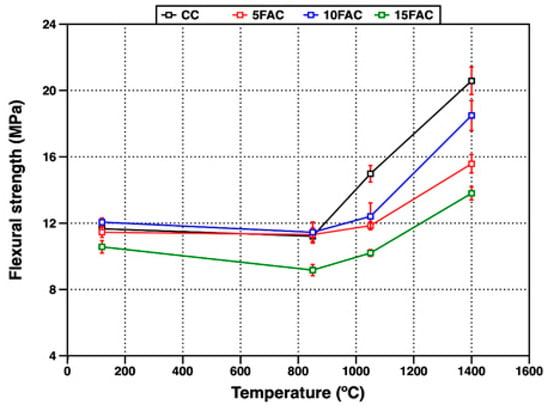

3.4.2. Flexural Strength

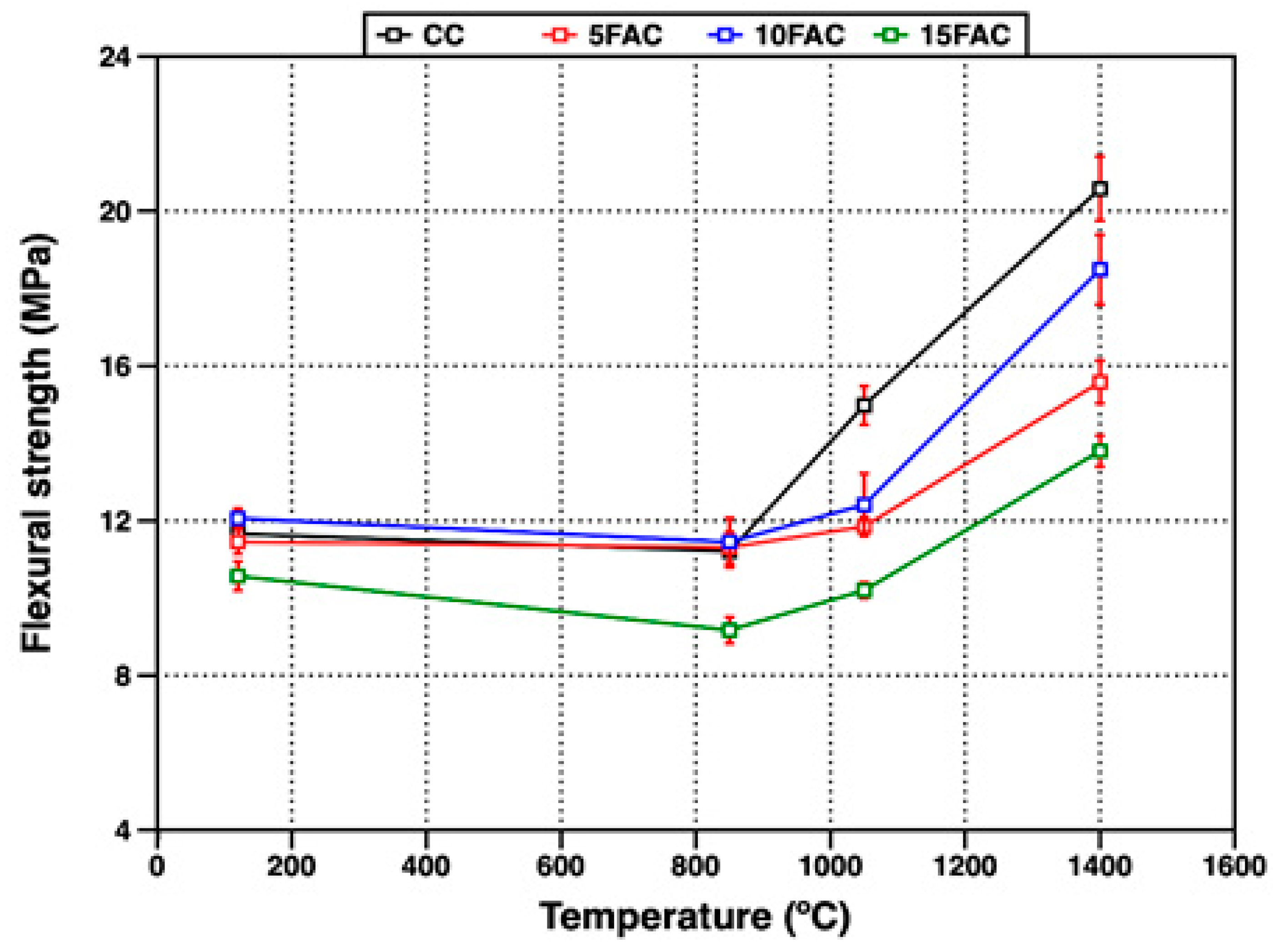

Figure 12 presents the flexural strength of the refractory specimens as a function of firing temperature. At 120 °C, the CC, 5FAC, and 10FAC samples exhibited comparable flexural strength values ranging from 11.4 to 12.1 MPa. This early-age mechanical strength primarily arises from the formation of hydraulic bonds and the development of cohesive gels during hydration, which enhance structural integrity through initial binder cohesion. In contrast, the 15FAC specimen recorded the lowest flexural strength at this temperature (10.6 MPa). This reduction is attributed to the higher water demand induced by the increased fly ash content, resulting in a more porous microstructure and lower bulk density—both factors known to deteriorate mechanical performance [34].

Figure 12.

Flexural strength of refractory specimens at different temperatures.

Upon heating to 850 °C, a slight decline in flexural strength was observed for the CC, 5FAC, and 10FAC specimens, with values ranging from 11.2 to 11.5 MPa. This decrease is ascribed to the decomposition of hydraulic bonds and the partial dehydration of hydrated phases, which temporarily weaken the structure before the establishment of a strong ceramic bond. However, the 15FAC specimen exhibited a more pronounced reduction in flexural strength, reaching only 9.7 MPa.

This marked decrease reflects the adverse influence of excessive SiO2 and porosity, as well as possible microcrack formation associated with the polymorphic transformation of quartz, which becomes increasingly significant at elevated temperatures. The contrasting behavior between 15FAC and the other compositions underscores the detrimental effect of excessive fly ash addition on the thermo-mechanical stability of refractory bodies in the intermediate temperature range.

At 1050 °C, the reference specimen (CC) exhibited a noticeable increase in flexural strength to 14.9 MPa, while the fly ash–containing specimens showed only marginal improvements. This trend is consistent with previous findings indicating that flexural strength is more sensitive to the continuity and maturity of the ceramic bond formed within the refractory matrix than to parameters such as particle size distribution or aggregate packing [30,31].

In fly ash–modified specimens, two competing processes likely govern the observed mechanical behavior. On one hand, the in-situ formation of crystalline phases such as mullite and anorthite begins to establish a ceramic bond.

On the other hand, thermal expansion-induced stresses arise from the polymorphic transition of SiO2 (α → β-quartz at ~573 °C), which may induce microcracking or weaken the matrix. The interplay of these phenomena results in a moderated flexural strength response relative to the reference specimen, emphasizing the complex interaction between phase evolution and thermal stresses in fly ash–based refractories.

At 1400 °C, the reference specimen achieved the highest flexural strength (20.6 MPa), followed by the 10FAC, 5FAC, and 15FAC specimens with values of 18.5, 15.6, and 13.8 MPa, respectively. Overall, flexural strength increased across all compositions at this peak firing temperature, consistent with the progressive development of ceramic bonding at elevated temperatures.

Among the fly ash–containing formulations, the 10FAC specimen exhibited a flexural strength approaching that of the reference material. This improvement is attributed to the synergistic effect of stable refractory phases—primarily mullite and corundum—and the densified ceramic matrix generated by the in-situ formation of secondary mullite and anorthite during sintering [60].

The interlocking morphology of secondary mullite needles, coupled with the densification promoted by anorthite formation, contributes to a more coherent and mechanically resilient microstructure that enhances resistance to flexural loading.

3.5. Microstructure

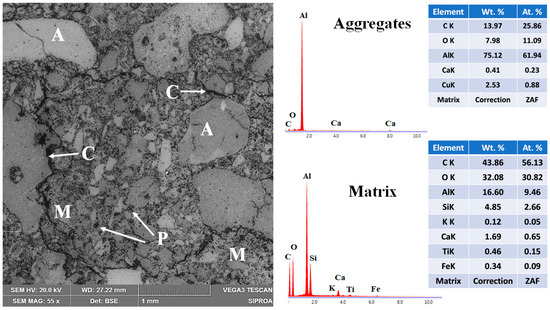

3.5.1. Reference Specimen (CC)

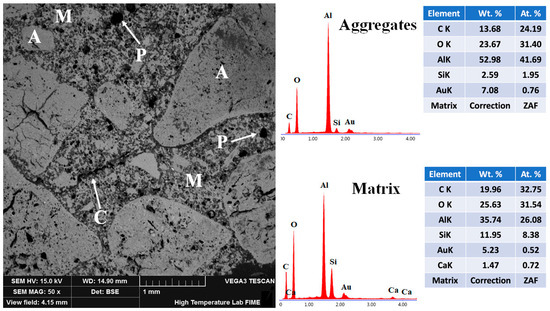

The microstructural features of the reference refractory specimen fired at 1400 °C are presented in Figure 13. The backscattered electron (BSE) micrograph reveals a heterogeneous structure composed of coarse and moderately sized aggregates (~1 mm to 50 μm) uniformly distributed throughout the refractory body. Most aggregates exhibit a subangular morphology and are partially embedded within a fine-grained matrix consisting of particles ≤50 μm [68,69]. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirms the chemical identity of the aggregates as predominantly corundum, which functions as the skeletal framework of the refractory body. The matrix phase is composed mainly of mullite, with minor amounts of anorthite. This phase composition supports the mechanical properties observed at high temperatures.

Figure 13.

Micrograph and EDS analysis of the CC refractory specimen obtained at 1400 °C, where M = matrix, A = aggregates, C = microcracks, and P = porosity.

However, notable microstructural deficiencies are also evident. The presence of porosity within both aggregates and matrix, along with transgranular and interfacial microcracks—some traversing the aggregates and others following the matrix–aggregate interfaces—indicates incomplete densification, as evidenced by residual porosity and interfacial microcracking. These features are primarily attributed to the dehydration of hydrated phases above 200 °C. The limited sintering activity and insufficient ceramic bonding at this temperature hinder the densification process, thereby adversely affecting the physical and mechanical performance of the reference formulation [6,30,31].

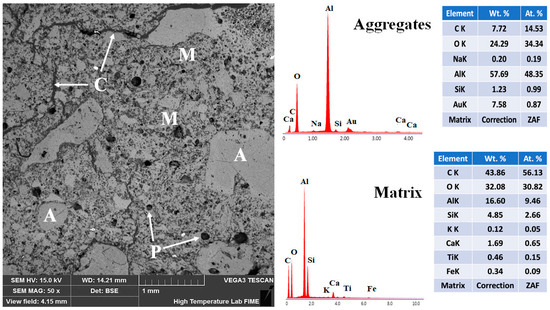

3.5.2. 5FAC

The microstructural characteristics of the 5FAC refractory specimen fired at 1400 °C are shown in Figure 14. The BSE micrograph displays a well-developed microstructure composed of uniformly distributed aggregates spanning a wide particle size range, effectively bonded by a continuous refractory matrix. EDS elemental analysis confirms the presence of corundum within the aggregates and mullite and anorthite within the matrix, in agreement with the XRD results for this specimen (see Figure 5). The incorporation of fly ash significantly modified the microstructure of the refractory body. Compared with the reference formulation, the 5FAC specimen exhibits a higher degree of aggregate compaction, attributed to the in-situ formation of secondary mullite crystals within the matrix. These interlocked, needle-like crystals enhance particle packing by bridging interparticle gaps, strengthening the ceramic bond, and improving overall mechanical performance [34].

Figure 14.

Micrograph and EDS analysis of the 5FAC refractory specimen obtained at 1400 °C, where M = matrix, A = aggregates, C = microcracks, and P = porosity.

The addition of fly ash also influenced the porosity characteristics of the microstructure. In addition to pores observed within the aggregates and matrix microcracks, rounded and isolated (closed-type) pores were detected within the matrix. This feature is typically associated with the formation of a transient liquid phase during high-temperature firing. Such small, spherical pores can play a beneficial role by reducing local stress concentrations and acting as crack-arresting sites, thereby improving the refractory’s resistance to thermal and mechanical stresses [6].

3.5.3. 10FAC

The microstructural features of the 10FAC refractory specimen sintered at 1400 °C are shown in Figure 15. EDS analysis confirmed the presence of corundum in the aggregates—serving as the high-strength backbone phase—along with mullite and anorthite distributed throughout the matrix. The BSE micrograph reveals a well-sintered and homogeneous structure characterized by a wide aggregate size distribution and strong matrix bonding. Enhanced densification and interparticle cohesion are evident, indicating superior sinterability. This improvement is attributed to the synergistic effect of fly ash addition and the in-situ formation of secondary mullite and anorthite, which promote a continuous and mechanically robust ceramic matrix [34,70,71].

Figure 15.

Micrograph and EDS analysis of the 10FAC refractory specimen obtained at 1400 °C, where M = matrix, A = aggregates, C = microcracks, and P = porosity.

The needle-like secondary mullite crystals act as structural bridges between adjacent particles, effectively closing microstructural voids. This bridging action reduces pore size—particularly of closed-type pores—and limits microcrack propagation, thereby enhancing fracture resistance [21,60]. These microstructural features—including homogeneous phase distribution, enhanced sintering of the aggregate phase, and refined pore structure—play a decisive role in enabling the 10FAC specimen to achieve the highest mechanical strength among all tested formulations (see Figure 11) [31,32,72].

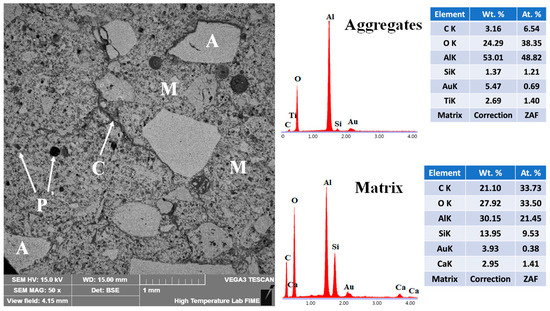

3.5.4. 15FAC

Figure 16 shows the microstructural characteristics of the 15FAC refractory specimen sintered at 1400 °C, along with the corresponding EDS elemental analysis of the aggregate and matrix phases. The BSE micrograph reveals that the coarse and medium-sized aggregates are poorly bonded to the fine-grained matrix. Based on grayscale contrast, these aggregates appear largely isolated, indicating weak phase interaction and limited ceramic bonding. Moreover, the pore structure is significantly coarser than that observed in the 10FAC specimen. Several previously closed pores exhibit increased size and partial interconnection, forming a network of open porosity. This observation is consistent with the elevated apparent porosity reported for the 15FAC composition (see Figure 9), which likely contributes to its reduced mechanical performance.

Figure 16.

Micrograph and EDS analysis of the 15FAC refractory specimen obtained at 1400 °C, where M = matrix, A = aggregates, C = microcracks, and P = porosity.

Because this formulation contained the highest fly ash content, it incorporated greater amounts of both crystalline and amorphous SiO2. These silica phases underwent substantial volumetric changes during firing due to polymorphic transformations, offsetting the beneficial effects of in-situ mullite formation. Consequently, the overall physical and mechanical performance of the refractory was adversely affected. This interpretation is supported by the observation of internal cracking within coarse aggregates, attributed first to contraction stresses during initial heating and subsequently to expansion stresses caused by silica phase transformations and secondary mullitization [4,6,21,50,71].

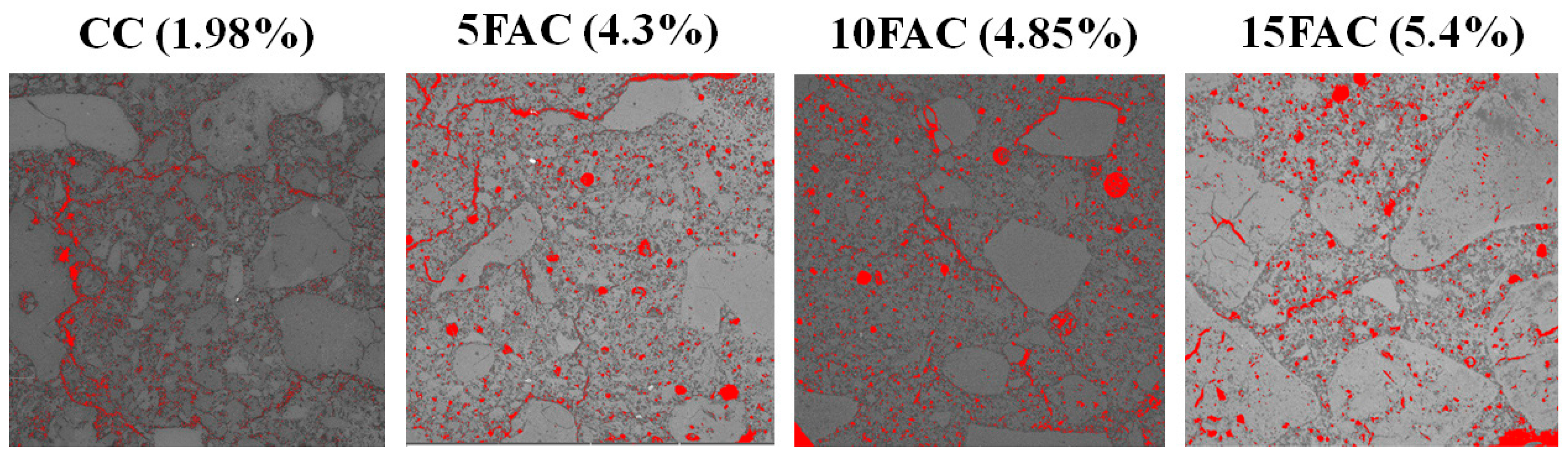

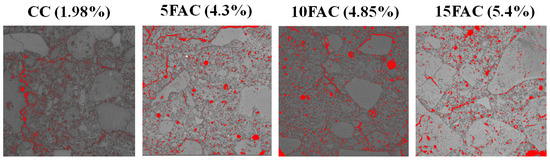

Figure 17 presents the total porosity of the refractory specimens, determined through quantitative image analysis using the ImageJ software (version 1.54p). For the reference castable (CC), the total porosity—including open and closed pores as well as microcracks—was estimated at 1.98%, consistent with the apparent porosity measured by conventional experimental methods. The 5FAC formulation exhibited a total porosity of 4.3%, accounting for interconnected pores, isolated voids, and microcracks, showing excellent agreement with its apparent porosity determined through standard tests. Similarly, the 10FAC specimen displayed a total porosity of 4.85%, while the 15FAC formulation reached 5.4%, both reflecting a close correspondence between image-based and experimentally derived data.

Figure 17.

The total porosity of the refractory specimens, determined through quantitative image analysis using the ImageJ software. Porosity corresponds to the red regions.

These findings confirm the reliability and accuracy of the ImageJ-assisted digital image analysis technique in quantifying porosity within dense aluminosilicate refractory castables. Furthermore, the progressive increase in total porosity with higher fly ash content suggests that excessive substitution promotes the formation of additional microvoids and microcracks, likely related to gas release and liquid-phase evolution during sintering. This porosity evolution correlates inversely with the mechanical strength trends observed, where moderate fly ash addition (10 wt.%) optimizes densification and strength, whereas higher contents (15 wt.%) lead to structural weakening due to increased pore connectivity and reduced matrix cohesion.

3.6. Environmental and Sustainability Implications of Fly Ash-Modified Refractory Castables

Recent research has increasingly focused on the development of refractory materials that not only meet demanding performance requirements but also advance sustainability objectives through the incorporation of industrial by-products. This strategy supports the conservation of non-renewable mineral resources while reducing the environmental impacts associated with conventional mining and raw material processing [16,29,30,31,36]. Considering the global abundance of fly ash—arising from the imbalance between its high generation rate and the relatively low percentage currently reused or recycled—this study represents a meaningful step toward expanding its valorization pathways. It aligns with ongoing scientific efforts to improve fly ash management and promote its use in producing value-added materials [3,5,6,7,10]. Incorporating fly ash into refractory formulations not only diverts this by-product from landfills but also reduces the carbon footprint associated with refractory castable production. Traditional refractories typically depend on high-temperature processing and the extraction of aluminosilicate-rich raw materials, both of which are energy- and emission-intensive.

In this context, the 10FAC formulation—incorporating 10 wt.% fly ash—demonstrated superior physical and mechanical performance. These enhancements are attributed to favorable microstructural evolution characterized by a uniform phase distribution and the in-situ formation of interlocked, needle-like mullite crystals. Such features promote densification, reduce open porosity, and limit microcracking [27,65]. These microstructural improvements could be further optimized through controlled adjustments of sintering temperature and dwell time, thereby reducing the energy intensity per unit of mechanical performance—an important eco-efficiency indicator in life cycle assessment (LCA).

From a life-cycle perspective, partially replacing virgin raw materials with fly ash can significantly lower cumulative energy demand and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Estimates from related LCA studies indicate that each tonne of fly ash reused in ceramic or cementitious systems can avoid approximately 0.3–0.5 tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions, primarily by offsetting clinker or synthetic alumina production [3,10]. When applied at an industrial scale, such substitutions could yield substantial environmental and economic benefits.

Regarding the cost–performance balance, fly ash acts not only as a reactive contributor to mullite formation and matrix densification but also as a cost-effective filler. Its incorporation into the 10FAC formulation decreases reliance on high-cost processed raw materials while maintaining—or even enhancing—key functional properties such as strength and thermal stability. This makes the material particularly suitable for refractory linings in biomass-fired boilers, where cost efficiency, thermal cycling resistance, and alkali durability are critical design factors. Moreover, the use of renewable biomass (e.g., wood) as fuel further strengthens the sustainability credentials of the system, establishing a closed-loop synergy between waste valorization and clean energy generation.

Nevertheless, further investigation is required to validate the long-term performance of the 10FAC formulation under service conditions. Future studies should evaluate its thermal shock resistance, alkali–slag corrosion behavior, and cyclic fatigue performance to confirm its suitability for biomass energy applications. These assessments should be complemented by a cradle-to-gate LCA to quantify environmental impact reductions compared with conventional refractory castables.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a conventional refractory castable with enhanced sustainability attributes can be successfully developed by incorporating up to 10 wt.% fly ash. This substitution yields tangible environmental benefits (reduced GHG emissions and improved material circularity), economic advantages (lower raw material cost), and technical improvements (enhanced strength and microstructure). The integration of industrial by-products such as fly ash into high-temperature materials provides a viable pathway toward cleaner production, consistent with circular economy principles and the broader goals of decarbonization in energy-intensive industries. This approach offers a balanced combination of technological, environmental, and economic advantages, positioning fly ash as a promising and valuable resource for next-generation refractory materials [12].

3.7. Future Perspectives

To build upon the promising results obtained in this study, future research will focus on evaluating the long-term durability and service performance of the developed fly ash-based refractory castables, particularly under conditions involving thermal shock cycles. Given the thermal fluctuations characteristic of biomass boilers, assessing thermal shock resistance is critical to confirm the material’s suitability for prolonged operation. Moreover, future investigations will address the material’s resistance to alkali vapor exposure, a common challenge in biomass combustion environments.

Also, understanding the reaction pathways, phase equilibria, and diffusion-controlled processes governing mullite crystallization and interfacial bonding would provide a deeper explanation of the enhanced mechanical and microstructural behavior observed in this study. A comprehensive thermodynamic–kinetic analysis, including the modeling of phase transformations, liquid-phase evolution, and chemical–thermal stability, is currently being developed as the second phase of this investigation. These ongoing studies will include high-temperature reaction modeling, differential thermal analysis (DTA/TG), and in-situ XRD to elucidate the transformation mechanisms and validate the proposed sintering behavior of the 10FAC formulation.

In parallel, a comprehensive life cycle assessment (LCA) will be conducted to quantify the environmental benefits of raw material substitution, including reductions in embodied energy, greenhouse gas emissions, and resource depletion. Techno-economic analyses will also be performed to evaluate cost–performance trade-offs and identify potential advantages relative to conventional refractory systems. Collectively, these forthcoming studies will be essential to validate the proposed formulation as a scalable, low-impact solution aligned with circular economy principles and decarbonization objectives for high-temperature industrial applications.

3.8. Novelty Statement

The novelty of this study lies in both the compositional design and the mechanistic understanding of fly ash utilization in aluminosilicate refractory castables. While previous studies—such as that by Škamat et al. (2024)—have explored low-level substitutions of calcined clay with fly ash cenospheres (3–7 wt.%) primarily to improve thermal shock and alkali resistance, the present work extends this approach by investigating higher replacement levels (up to 15 wt.%) of the fine fraction of flint clay with bulk fly ash in dense castable formulations [6].

Furthermore, this study systematically correlates the effect of fly ash content with sintering behavior, phase evolution, and microstructural development across a wide temperature range (850–1400 °C). The findings reveal that the 10 wt.% substitution ratio provides the optimal balance between densification and strength, driven by the formation of a SiO2-rich transient liquid phase that promotes in-situ secondary mullite crystallization and enhanced interparticle bonding.

Unlike previous works that focused mainly on thermal performance, this study provides new insights into the thermally induced reaction mechanisms responsible for mechanical enhancement and microstructural refinement. It also demonstrates the feasibility of valorizing industrial by-products to produce sustainable refractory materials compatible with commercial processing routes, thus contributing to circular economy and low-carbon manufacturing pathways.

4. Conclusions

Given the urgent need to enhance fly ash recycling, green manufacturing strategies that incorporate high volumes of industrial by-products into value-added materials present a promising pathway. Such approaches simultaneously address waste management challenges, conserve finite natural resources, and contribute to sustainable development goals. In this context, the present study investigated the partial replacement of the fine fraction of flint clay with fly ash at substitution levels of 0, 5, 10, and 15 wt.% in the formulation of conventional refractory castables with improved sustainability. The results revealed that the composition containing 10 wt.% fly ash (10FAC) provided the optimal balance of physical and mechanical properties among all tested formulations. Specifically, the 10FAC castable exhibited a slightly reduced bulk density (2.21 g/cm3), attributed to the lower specific gravity of fly ash relative to the replaced flint clay. Despite this, the apparent porosity of the 10FAC specimen (26.39%) was only 2.5% higher than that of the reference castable (25.74%), indicating a negligible effect on densification.

Notably, the compressive strength of the 10FAC specimens surpassed that of the other compositions at both intermediate (1050 °C: 45.0 MPa) and high firing temperatures (1400 °C: 65.3 MPa), confirming the mechanical robustness of this formulation. Microstructural analysis revealed enhanced sintering behavior, characterized by extensive mullite formation and a well-distributed network of interlocked secondary mullite crystals with needle-like morphology. These crystals were generated through the formation of a SiO2-rich liquid phase derived from fly ash impurities at intermediate temperatures, which promoted pore closure, reduced microcracking, and strengthened interparticle bonding among corundum grains.

The optimal composition containing 10 wt.% fly ash (10FAC) demonstrates a practical and industrially relevant balance between workability, densification behavior, and mechanical integrity, making it suitable for a wide range of monolithic refractory applications. Owing to its improved compressive strength after firing at both 1050 °C (45.0 MPa) and 1400 °C (65.3 MPa), along with a relatively low apparent porosity (26.39%) and well-developed mullite–corundum microstructure, the 10FAC castable is particularly applicable in environments demanding high thermal stability and corrosion resistance.

In industrial practice, this composition can be effectively employed in steelmaking ladles, tundish linings, burner blocks, kiln furniture, rotary kiln linings, and cement and non-ferrous furnaces, where vibratable or self-flowing castables are required to combine mechanical reliability with ease of installation. The 10 wt.% substitution level also ensures sufficient fluidity for proper casting and compaction, minimizing segregation and internal defects during installation.

From a sustainability perspective, the 10FAC formulation aligns with circular economy principles by integrating fly ash as a secondary raw material, thereby reducing dependence on natural flint clay and lowering the embodied energy and CO2 emissions associated with refractory production. Its demonstrated performance indicates strong potential for scalable industrial adoption, particularly in facilities seeking to implement low-carbon and resource-efficient refractory technologies without compromising high-temperature performance.

Overall, the findings of this study confirm the technical feasibility of incorporating fly ash as a sustainable raw material in refractory formulations without compromising essential functional properties. The proposed castable composition aligns with circular economy principles, promotes the valorization of industrial by-products, and delivers environmental benefits through resource conservation and potential reductions in embodied energy and carbon emissions. This strategy contributes to the ongoing transition toward cleaner production pathways in high-temperature material systems and establishes a foundation for future life cycle assessment (LCA) studies aimed at quantifying its environmental footprint.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.L.-P. and E.A.R.-C.; methodology, L.D.-T., J.F.L.-P., Y.G.-C., S.U.C.-A. and E.A.R.-C.; validation, E.A.R.-C. and J.E.C.d.L.; formal analysis, L.D.-T., J.F.L.-P., Y.G.-C. and E.A.R.-C.; investigation, J.F.L.-P. and E.A.R.-C.; resources, E.A.R.-C. and J.E.C.d.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.L.-P. and E.A.R.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.F.L.-P., L.D.-T., Y.G.-C., J.E.C.d.L., S.U.C.-A. and E.A.R.-C.; visualization, J.F.L.-P., L.D.-T. and E.A.R.-C.; supervision, E.A.R.-C.; project administration, E.A.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments