Abstract

A photoelectric tracking system is a typical bearing-only target tracking system that faces significant challenges arising from measurement origin uncertainty due to clutter and the discrepancy between continuous-time target dynamics and discrete-time optical sampling, as well as the inherent nonlinearity of bearing-only tracking. This paper addresses these issues by proposing a novel distributed probabilistic data association feedback particle filter (DPDA-FPF) framework. To resolve the tracking ambiguity at the local level, we extend the feedback particle filter to a continuous-discrete setting integrated with probabilistic data association. Subsequently, the local state estimates and covariances from spatially separated tracking systems are transmitted to a fusion center and integrated using an optimal linear covariance-weighted fusion rule to improve global observability and mitigate biases of individual systems. Numerical simulations in a 3D scenario with moderate clutter density demonstrate that while individual sensor tracks suffer from fluctuations, the proposed fused estimate achieves substantially lower root mean square errors in both position and velocity. The results validate the efficiency of the proposed architecture as a robust solution for photoelectric tracking applications.

1. Introduction

Photoelectric tracking systems are systems that utilize optical sensors to detect and track targets. The task of target tracking is to estimate the position and velocity of a moving target using noisy data collected by a single sensor or multiple spatially distributed sensor nodes [1]. Due to their ability to provide high-precision angular measurements, these systems play a critical role in precise tracking and identification tasks across broad civilian domains, including unmanned aerial vehicle monitoring for environmental inspection, aircraft monitoring and space object tracking [2]. However, unlike active radar, photoelectric tracking systems rely on passive detection and provide only bearing information without direct range measurements [2], which makes bearing-only target tracking with passive sensors a fundamental and challenging problem in statistical signal processing [3]. In addition, optical measurements are typically sampled discretely, whereas target motion is generally modeled by continuous-time dynamics, resulting in a natural continuous–discrete system. Furthermore, factors such as ambient illumination changes, atmospheric attenuation, occlusion, and sensor noise can significantly degrade the measurement accuracy, increasing the uncertainty in target tracking. Consequently, achieving accurate target state estimation using photoelectric tracking systems remains a challenging task, motivating further research in bearing-only target tracking.

For a single photoelectric tracking system, the absence of direct range information makes estimation performance highly sensitive to the sensor–target geometry. For example, the target may become unobservable under certain motion patterns, leading to large estimation bias and poor convergence behavior [4,5]. Classic results show that the single-observer tracking process can be unobservable when the observer velocity is constant, and estimating the complete target state may require changes in observer velocity or course [6,7]. However, when multiple spatially separated passive photoelectric tracking systems are available, the situation improves substantially: combining angle measurements from different viewpoints provides implicit triangulation information and can restore practical observability of target position and velocity without requiring aggressive maneuvers [8,9]. From an implementation standpoint, the centralized fusion of all raw optical measurements may be impractical due to bandwidth, latency, and robustness constraints [10,11]. This is why multi-sensor bearing-only tracking has attracted sustained attention in modern distributed photoelectric tracking systems. A widely adopted alternative is track-level fusion, where each photoelectric tracking system runs a local filter and transmits compact summaries such as state estimates and associated covariances to a fusion node, offering significant advantages in bandwidth efficiency and robustness [12].

A fundamental challenge in bearing-only photoelectric tracking system arises from the highly nonlinear relationship between bearing measurements and the target state, including position and velocity. To address this nonlinearity, various state estimation methods have been developed. The extended Kalman filter (EKF) [13] linearizes the measurement model around the current estimate. However, for bearing-only tracking, the EKF has been shown to suffer from instability due to the coupling between the bearing and range errors, potentially leading to covariance collapse and divergence [13]. To overcome these limitations, the unscented Kalman filter (UKF) [14] propagates the mean and covariance through the true nonlinear functions using deterministic sigma points, capturing higher-order effects and generally providing improved stability and performance. Nevertheless, both EKF and UKF rely on Gaussian assumptions and may perform poorly in the presence of strong nonlinearities or non-Gaussian posteriors. From a Bayesian perspective, bearing-only tracking is inherently nonlinear and often non-Gaussian, making particle filters (PFs) [15] a natural choice. PFs approximate the posterior distribution using weighted particles and can be applied to general state-space models. However, standard PFs may suffer from particle degeneracy, and this issue becomes increasingly severe as the state dimension grows, leading to the curse of dimensionality. As a result, PFs often require a large number of particles, frequent resampling, or carefully designed proposal distributions to maintain stable performance [16,17]. More recently, the feedback particle filter (FPF) [17] has been proposed as an alternative that avoids importance sampling. In FPF, particles evolve under a feedback control law derived from an innovation error, with the filter gain obtained by solving a Poisson equation. By eliminating importance weights and resampling, FPF mitigates particle degeneracy and exhibits improved scalability with respect to state dimension, making it particularly attractive for nonlinear bearing-only tracking problems.

In realistic surveillance environments, the measurement stream is rarely clean. Each scan may include spurious detections generated by background returns and non-target phenomena, such as receiver thermal noise, reflections from terrain or structures, meteorological effects, and even birds [18]. Consequently, the observations available at a given time are often a mixture of target-originated and non-target-originated measurements, making it unclear which measurement should be attributed to the target. These effects introduce measurement-origin uncertainty and create a data association problem [18]. The probabilistic data association (PDA) framework [19] is a classical and computationally efficient approach to this challenge. The PDA aggregates validated measurements through association probabilities rather than enumerating combinatorial hypotheses, and it has been extensively studied for tracking in cluttered environments [20,21]. Integrating PDA principles with nonlinear filtering methods is therefore a natural direction for robust bearing-only tracking under clutter. More recently, probabilistic data association feedback particle filter (PDA-FPF) algorithms have been proposed for single-sensor tracking scenarios [22,23]. However, for distributed sensor networks, research on FPF algorithms applicable to cluttered environments remains very limited, particularly for continuous–discrete systems with bearing-only measurements. As a result, this problem remains an open and pressing research topic.

Motivated by the above, this paper investigates 3D bearing-only target tracking in cluttered environments using a distributed photoelectric tracking system with multiple passive sensors. We propose a DPDA-FPF framework in which each sensor runs a local PDA-FPF using an efficient gain approximation, and local state estimates with uncertainty information are then fused at the track-level through covariance-weighted fusion. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- 1.

- Continuous–discrete PDA-FPF derivation: We extend the FPF framework to accommodate both PDA and continuous–discrete system dynamics. Specifically, we derive the association-weighted particle flow equation (Equation (11)) by incorporating PDA likelihoods into the logarithmic homotopy transformation of [24]. This formulation yields an explicit innovation structure (Equation (12)) that naturally handles multiple validated measurements while preserving the computational advantages of the constant-gain approximation.

- 2.

- Design of a distributed multi-sensor FPF architecture for cluttered environments: This architecture achieves high bandwidth efficiency by having each sensor independently perform data association and local filtering. Subsequently, only compact track summary information is transmitted for centralized fusion processing. The proposed design fully accounts for practical constraints commonly encountered in real-world sensor networks, such as limited communication bandwidth and decentralized processing requirements.

- 3.

- Numerical validation in a 3D multi-sensor setting with clutter: This shows that the fused DPDA-FPF estimate significantly improves the tracking accuracy relative to single-sensor local estimates, consistent with the observability advantages of multi-view angle information.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 formulates the problem. Section 3 extends the PDA-FPF originally derived for continuous-time systems to the continuous–discrete setting. Section 4 presents the proposed DPDA-FPF algorithm and discusses its computational complexity and real-time implementation considerations. Section 5 reports the simulation settings and performance results. Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

2. Problem Statement

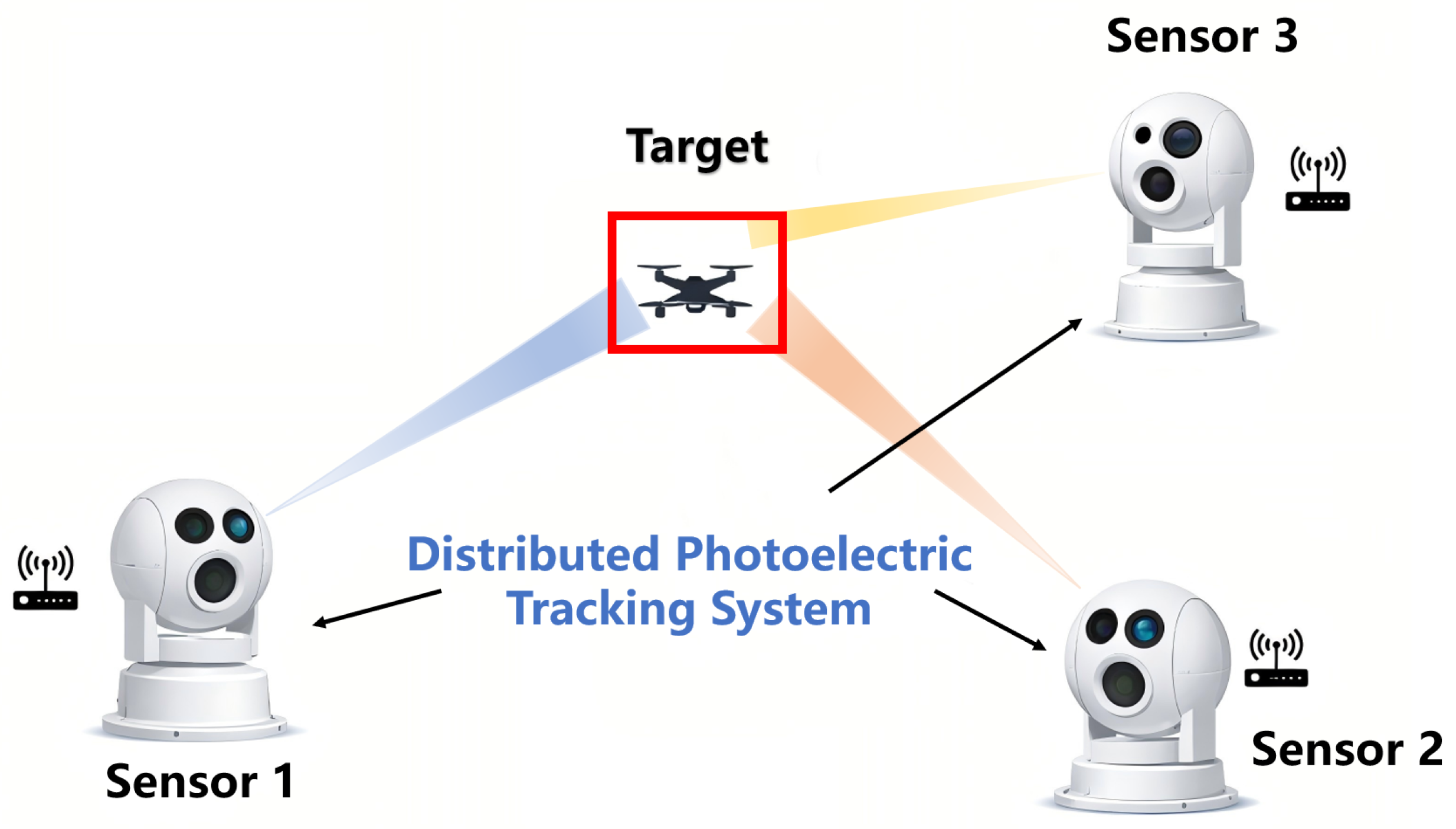

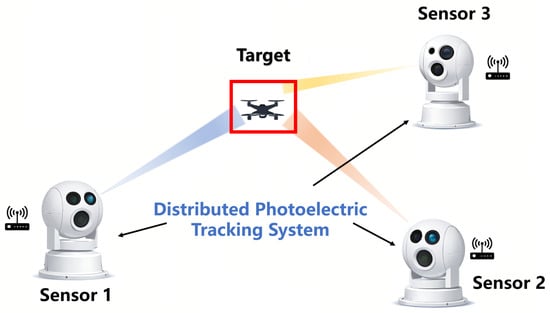

This paper investigates the problem of target tracking in a 3D cluttered environment, considering a distributed photoelectric tracking system network composed of multiple spatially separated bearing-only photoelectric tracking systems, as illustrated in Figure 1. Each photoelectric tracking system integrates a passive optical sensing unit that provides bearing-only measurements and a local processing module and is, therefore, regarded as a single sensing node in the distributed network. The target is modeled as a point target. Furthermore, each photoelectric tracking system is assumed to possess sufficient resolution to discriminate between objects, ensuring that each measurement originates from a single source, either the target or clutter. Based on these assumptions, this section establishes the system model for the considered scenario and then formulates the distributed tracking problem.

Figure 1.

Distributed photoelectric tracking system.

2.1. Continuous-Time Target Model

Since continuous-time models more accurately represent target motion than their discrete-time counterparts, we assume the target state evolves according to the stochastic differential equation

where ∈ denotes the target state at time t, including its position and velocity in the X, Y, and Z directions, i.e., . The function is continuously differentiable, i.e., a function, is a standard Wiener process, and is a constant.

2.2. Discrete-Time Sensor Model

At time , the sensor s receives a set of measurements where denotes the i-th measurement. In this paper, we assume the number of measurements is fixed at . However, the sources of the measurements are unknown. It is assumed that each sensor receives one measurement from the true target, and the rest are clutter. The set of measurements received up to time t is denoted as . The measurement model is defined as follows.

2.2.1. Target Measurement

At time , the measurement set of each sensor contains one target-originated measurement . Since a bearing-only sensor can only obtain the azimuth and elevation angle information of the target within the three-dimensional surveillance region, the target measurement is expressed as . The position of the s-th sensor is defined as . Therefore, the target measurement model can be described by the following discrete nonlinear equation:

where the nonlinear function is given by

and the measurement noise is assumed to follow a zero-mean Gaussian distribution with known covariance, i.e.,

2.2.2. Clutter Measurement

At each time instant , each sensor generates a fixed number of clutter measurements, denoted by , which remains constant over time. The clutter is generated by independently sampling the slant range and bearing angles from uniform distributions within the sensor field-of-view. Specifically, the azimuth and elevation angles are uniformly distributed over the predefined angular ranges, and the slant range is uniformly distributed within . Note that this sampling results in a distribution that is uniform in the spherical-coordinate parameters , but not necessarily uniform in Cartesian 3D volume.

The clutter samples are generated in spherical coordinates according to

then, the Cartesian position of each clutter point relative to the sensor is obtained by

and the corresponding bearing-only clutter measurement is given by

Under the sampling scheme used in this work, let denote the spherical coordinates associated with , and define the clutter support region

Since the Jacobian determinant of the transformation is

the induced 3D clutter density (w.r.t. volume) is

2.3. Distributed Tracking Problem

Distributed state estimation techniques are employed for target tracking under bearing-only measurements in order to enhance the robustness and flexibility of sensor network–based tracking systems. By fusing the local state estimates, more accurate global estimates can be obtained, thereby improving the overall tracking performance. In a cluttered environment, the single-target tracking problem can be decomposed into three main components. First, measurement-to-target association needs to be performed. Subsequently, a local filter capable of processing bearing-only measurements is constructed. Finally, the tracks generated by the local filters are fused to obtain the final tracking result.

3. Continuous–Discrete Probabilistic Data Association Feedback Particle Filter

In this section, the PDA-FPF method, originally developed for single-target filtering in the presence of multiple measurements, is extended to continuous–discrete systems. Its direct extension to distributed filtering with multiple independent sensors will be presented in Section 4.

For each local filter, the objective of PDA-FPF is to obtain the posterior distribution of the state given the observation history up to time t. It specifically includes the following two steps:

- 1.

- Estimate the association probabilities;

- 2.

- Incorporate the association probabilities into the FPF formulated for the continuous–discrete system.

3.1. Assumptions and Scope

The following are the key assumptions underlying the continuous–discrete PDA-FPF algorithm described in this section.

- (A1)

- Only one point target is present in the surveillance region.

- (A2)

- The target process noise is modeled by a Wiener process independent of the initial state . This standard assumption ensures the target state evolves as a Markov process, which is a requisite for the derivation of the recursive Bayesian filtering equations.

- (A3)

- is a known function, ensuring that Equation (1) admits a pathwise unique solution for every initial state.

- (A4)

- Each scan contains exactly one target-originated measurement, i.e., the probability of detection is , and the remaining measurements are clutter. While real-world sensors have , assuming unit detection probability allows the derivation to focus specifically on the feedback control law for clutter rejection without the added variance of missed detections.

- (A5)

- Clutter measurements are independent and identically distributed, independent of the target state, and approximately uniform in the bearing measurement space. The clutter cardinality is fixed per scan. The independence between clutter and target is fundamental to the PDA likelihood factorization.

- (A6)

- Measurement noises are zero-mean Gaussian with known covariance and are independent across time and across sensors. Furthermore, are mutually independent of the state process . This ensures that the innovation process contains new information solely from the current observation, allowing the particle flow to be driven by the gradient of the log-likelihood without cross-correlation terms.

- (A7)

- Sensors are time-synchronized, their positions are known, and fusion is performed at common sampling instants.

These assumptions strike a balance between capturing the essential physics of photoelectric tracking and ensuring mathematical tractability. From an engineering perspective, assumptions (A1) and (A6) are well-justified for long-range surveillance scenarios, where targets appear as point sources, and sensor noise is dominated by thermal effects. Similarly, (A7) is readily satisfied using modern timing and positioning services. From a theoretical standpoint, assumptions (A2), (A5), and (A6) are critical for decoupling the target dynamics from the measurement process. This independence facilitates the rigorous derivation of the feedback control law in the subsequent sections, ensuring that the particle flow is driven by the innovation error without the interference of intractable cross-correlation terms.

3.2. Association Probability

At time , an association random variable is defined to represent the association relationship between the measurements of sensor s and the target. means that the m-th measurement originates from the target. The association probability is defined as

which satisfies the normalization condition

According to the nonlinear association probability formulation in the classical Probabilistic Data Association Filter (PDAF) and Bayes’ rule [23,25], we have

where

and the weighted norm is as follows:

3.3. Continuous–Discrete Probabilistic Data Association Feedback Particle Filter Algorithm

FPF approximates the posterior distribution by evolving an ensemble of particles . In particular, over the continuous-time interval , the dynamics of the i-th particle in the s-th local filter are described as follows:

where represents the state of the i-th particle at time t, and are independent standard Wiener processes. In addition, the state is known, and the initial particles are sampled, independent and identically distributed, from the true prior distribution .

At the discrete-time instant , upon receiving a new set of observations , pseudo-time particle flow updates are introduced to continuize the discrete observations. Therefore, the particles are updated according to the following equation:

where the initial state satisfies

and the parameter denotes a pseudo-time variable. The objective of the filtering problem is to design the control term such that the distribution of , denoted by , approximates the true posterior distribution . In addition, the particle state is updated as

The pseudo-time variable converts the discrete-time Bayesian measurement update at into a continuous flow from prior to posterior. Starting from the predicted particles at , we design the control term so that the particle density evolves toward the posterior at . The transport is achieved via an innovation-based feedback law, where each particle is adjusted by a gain-weighted innovation, i.e., the difference between a candidate measurement and the corresponding predicted measurement. Under measurement-origin uncertainty, the association probabilities assign a probability weight to each validated measurement, so the total feedback becomes a weighted combination of innovations from all measurements. In addition, a Wong–Zakai correction is required when expressing the controlled diffusion in Itô form. Motivated by the above transport interpretation, we adopt the following innovation-based feedback control structure:

Then, the dynamics of the i-th particle are given by

where the innovation process is

and is the Wong–Zakai correction term, where each element is given by

where is element of

By applying a logarithmic homotopy transformation, the true discrete-time Bayesian measurement update is reformulated as a continuous-time evolution process, which is defined as and satisfies [24]

The distribution of is defined as . Our objective is to choose such that . Accordingly, the gain function is defined as

where is the solution to the following Euler–Lagrange boundary value problem

for , where denotes the entry of , , and denotes the j-th entries of and , respectively.

4. Distributed Data Association Feedback Particle Filter

This section extends the PDA-FPF designed for continuous–discrete systems to a distributed multi-sensor framework. In this framework, each local sensor independently executes the PDA-FPF to produce a local estimate, which is subsequently fused at a central fusion center using a designated fusion criterion to yield the final estimate. The fusion method used in this paper and the overall procedure of the proposed DPDA-FPF algorithm are presented below.

4.1. Covariance-Weighted Fusion

At time , the s-th sensor independently runs a PDA-FPF and obtains a local state estimate as follows:

The local posterior covariance is estimated from the particle cloud using the sample covariance

To integrate these local estimates, when the estimation errors from different sensors are mutually independent and unbiased, an optimal linear fusion rule in the minimum mean square error (MMSE) sense can be employed. Consider a linear fused estimate of the form

where the coefficients are required to satisfy . The covariance of the fused estimation error is

By minimizing using the method of Lagrange multipliers, the weight matrices are obtained as

where the fused covariance is

Therefore, at time , the fused state estimate is given by

and it is straightforward to verify that . At each time , the fusion algorithm is as shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Covariance-weighted fusion |

|

The MMSE optimality of the covariance-weighted fusion in Equation (18) is derived under the standard assumption that the local estimation errors are mutually independent or, more precisely, mutually uncorrelated. This assumption is attractive in track-level fusion, because it enables the fusion center to compute the weights using only the marginal covariances , thereby avoiding the propagation and communication of cross-covariance terms. In practical distributed tracking, however, exact independence is rarely satisfied: even if measurement noises are independent across sensors, the local posteriors become coupled through the common target state and shared modeling information. The dominant sources of correlation include the common process uncertainty induced by the stochastic maneuver term in Equation (1), which affects all sensors simultaneously, and common prior information at initialization such as identical . Nevertheless, the independence approximation may still be reasonable in regimes where measurements are sufficiently informative and geometrically diverse, such that sensor-specific information dominates, and the induced cross-covariances remain small relative to the marginal covariances.

When these correlations are neglected by enforcing , the fusion center effectively double-counts shared information, giving rise to the well-known data incest phenomenon. Although the fused mean in Equation (18) remains unbiased as long as the local estimates are unbiased and , the resulting weights are no longer MMSE-optimal, and Equation (17) typically underestimates the true fused error covariance. This overconfidence can lead to filter inconsistency and may amplify occasional local misassociations or weak-observability episodes, potentially causing divergence in long-term tracking. Correlation-robust methods such as covariance intersection avoid overconfidence without requiring cross-covariances, but they are usually conservative and can sacrifice precision when sensors provide complementary information. In the considered photoelectric tracking scenario, spatially separated sensors offer strong geometric diversity, which approximate orthogonal bearing constraints, and the fusion architecture is feed-forward, i.e., no fused-feedback to local filters, both of which mitigate the practical impact of unknown correlations. Therefore, consistent with common approximations in bandwidth-constrained distributed tracking [10], we adopt the standard covariance-weighted fusion in Equation (17) to maximize the exploitation of multi-view observability, while interpreting the obtained as an approximate uncertainty description; correlation-aware fusion or adaptive covariance inflation is left for future work.

4.2. Distributed Data Association Feedback Particle Filter Algorithm

This section presents an overview of the DPDA-FPF algorithm for continuous–discrete systems. In order to implement the algorithm, several approximation procedures are required.

First, the association probability can be approximated using the following particle-based method in numerical experiments:

where

Therefore, at each time , the association probability of each sensor s is calculated as shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Association probability |

|

In practice, to reduce computational complexity, the correction term is neglected. Accordingly, the particle dynamics are approximated by

Numerous studies have investigated gain approximations [26]. In this paper, the following constant-gain approximation is employed in the numerical experiments:

where

Exact computation of the gain function requires solving a Poisson equation at each step, which is computationally intractable for real-time applications. Therefore, we adopt the constant-gain approximation, which assumes a quasi-Gaussian structure for the gain computation while retaining the nonlinear transport of particles.

The complete DPDA-FPF algorithm under the constant-gain approximation and without the correction term is presented in Algorithm 3. The prediction step is discretized via the Euler–Maruyama method with step size , while the update step is discretized in pseudo-time with step size .

| Algorithm 3 DPDA-FPF for continuous–discrete systems |

|

4.3. Computational Complexity and Real-Time Considerations

Let denote the state dimension, the measurement dimension, N the number of particles, S the number of sensors, and the number of validated measurements at scan k for sensor s. The pseudo-time discretization uses step size with sub-steps. Denote by and the operation counts of evaluating and , respectively; for typical kinematic models and bearing-only measurement functions, both are up to small constant factors such as a few trigonometric evaluations. The per-scan per-sensor computational complexity of the main DPDA-FPF modules is summarized in Table 1. In fact, the covariance-weighted fusion in Algorithm 1 requires one inversion per sensor and a few matrix multiplications, i.e., per scan, which is negligible for small compared with the particle operations. From Table 1, the overall per-scan complexity across all sensors is dominated by the pseudo-time particle update, because it contains the innermost triple loop, i.e., pseudo-time, particles and measurements, and repeatedly evaluates the innovation terms and measurement functions. Therefore, improving the real-time performance of DPDA-FPF mainly reduces to controlling , N, and and to accelerating this pseudo-time update kernel.

Table 1.

Per-scan per sensor computational complexity of DPDA-FPF modules.

Let denote the sensor sampling period. A necessary condition for real-time operation is that the processing time per scan remains below , accounting for communication and fusion latency. The real-time feasibility of the proposed DPDA-FPF therefore relies on several practical strategies. First, validation gating reduces the number of validated measurements by rejecting observations that are statistically inconsistent with the predicted bearing, yielding an immediate reduction in the dominant association-probability and pseudo-time update costs while also improving numerical stability in the presence of clutter. Second, the constant-gain approximation replaces the intractable Poisson equation for the feedback gain with sample-moment computations of complexity , making real-time implementation feasible. Third, adopting a single-step pseudo-time update avoids the pseudo-time integration loop by evaluating the gain and innovation once and transporting particles to the posterior in a single Euler step, thereby significantly reducing latency. Finally, the DPDA-FPF architecture is naturally parallel: local filtering across sensors can be executed concurrently, while particle propagation and updates within each sensor are parallel and well-suited for SIMD or GPU acceleration. Since only low-dimensional summary statistics are transmitted to the fusion center, the communication overhead is minimal. Together, these strategies enable real-time deployment of DPDA-FPF in photoelectric tracking systems without altering the underlying Bayesian structure of the filter.

5. Numerical Experiments

In this section, the performance of the proposed DPDA-FPF algorithm is evaluated through numerical simulations. A scenario involving a single target moving in a 3D clutter environment monitored by a distributed sensor network is considered.

5.1. Simulation Setup

The target moves in a 3D space following a continuous-time constant velocity (CV) model. The state vector at time t is defined as , and the state evolution is described by the stochastic differential equation

where is a standard Wiener process representing the process noise with diffusion intensity . The system matrices are defined as

In the simulation, the continuous model is discretized using the Euler–Maruyama method with a time step of .

The tracking system consists of passive sensors located at fixed coordinates for . The sensors provide 3D bearing-only measurements, i.e., azimuth and elevation, at discrete-time , where is the sampling interval. The measurement equation for the s-th sensor at is given by

where with covariance . The nonlinear observation function is defined as

In addition, at each sampling instant, each sensor generates bearing-only clutter measurements by sampling the azimuth and elevation independently and uniformly over and with .

5.2. Validation Gating Strategy

In cluttered environments, a validation gate is essential to reduce the computational load and eliminate measurements that are statistically unlikely to originate from the target. A validation region is constructed around the predicted measurement for each sensor. A measurement is considered a valid candidate only if its Mahalanobis distance squared falls within a threshold

where measurements with are assigned an association probability of zero. The threshold is determined based on the Chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom. In this work, to ensure a high probability of retaining the true target measurement while rejecting distant clutter, we set for all sensors.

5.3. Implementation Details

Initialization: To evaluate the convergence capability and robustness of the proposed algorithm, the initial particles are not sampled directly from the true state. Instead, they are initialized with a deterministic bias. Specifically, the particles for each sensor are drawn from a Gaussian distribution centered at , where the bias vector is set to .

Fusion Regularization: In the distributed covariance-weighted fusion step, inverting local covariance matrices may lead to numerical instability, particularly during filter initialization or when particle diversity is depleted. To mitigate this, a regularization term is applied

where is a small regularization constant and is the identity matrix.

Single-Step Update Approximation: While the theoretical derivation of the FPF involves a continuous flow of particles over the pseudo-time interval , implementing a numerical integration with a small step size requires re-evaluating the gain function at each sub-step, which increases the computational complexity. To ensure computational efficiency, we adopt a single-step Euler approximation in the numerical experiments, corresponding to a pseudo-time step size . Consequently, the gain function and innovation terms are evaluated once based on the particle distribution at , and the particles are updated directly to the posterior in a single step. This approximation has been shown to be effective in scenarios with moderate measurement noise levels [26].

Performance Metric: To evaluate the tracking accuracy, Monte Carlo experiments are conducted. For the r-th Monte Carlo run () at time step , let and denote the true position and velocity vectors, respectively. Similarly, let and denote the estimated vectors. Define the per-run Euclidean errors as

The Monte Carlo RMSEs are computed as

The specific parameters used in the numerical simulation are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters’ configuration.

5.4. Results and Discussion

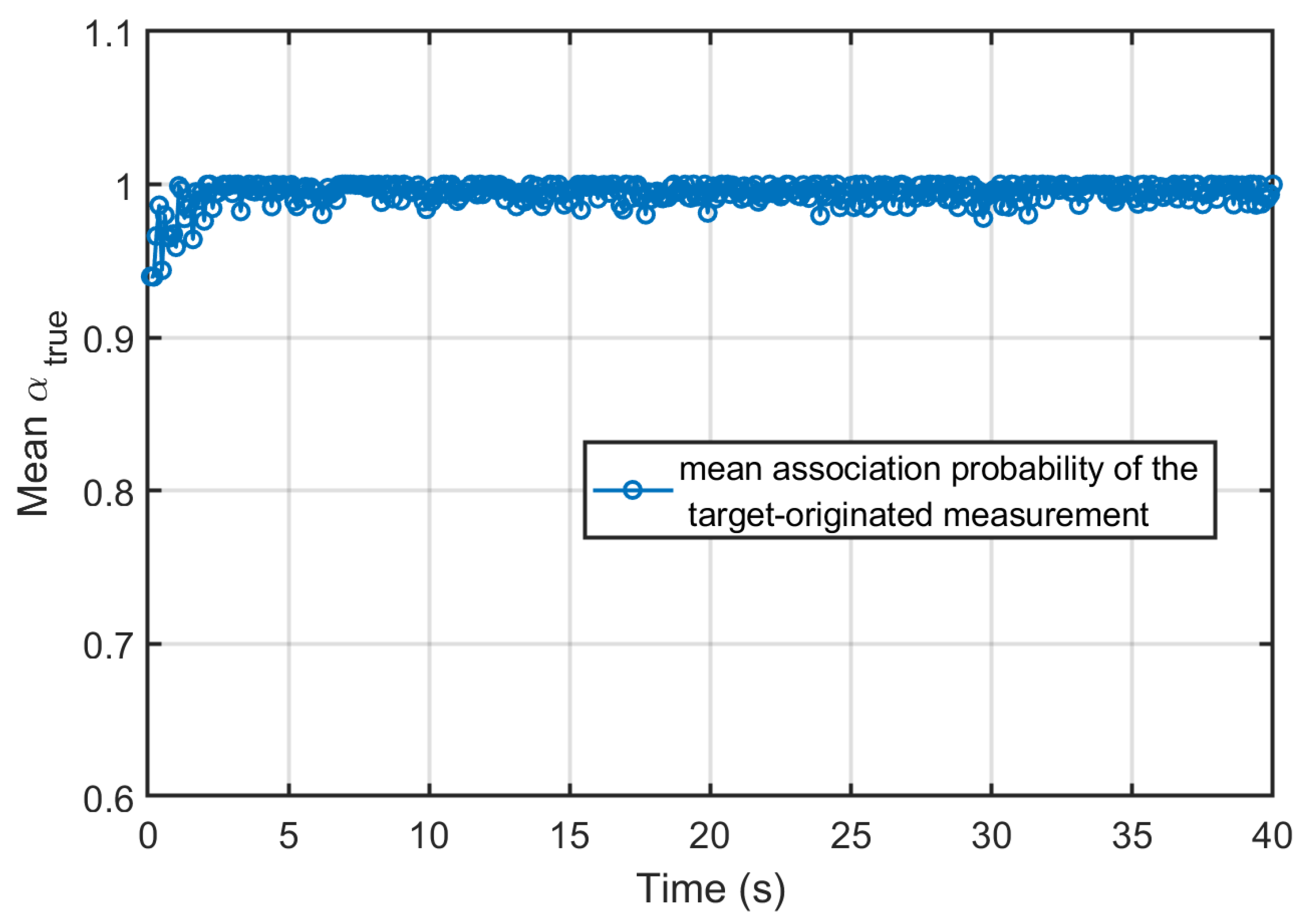

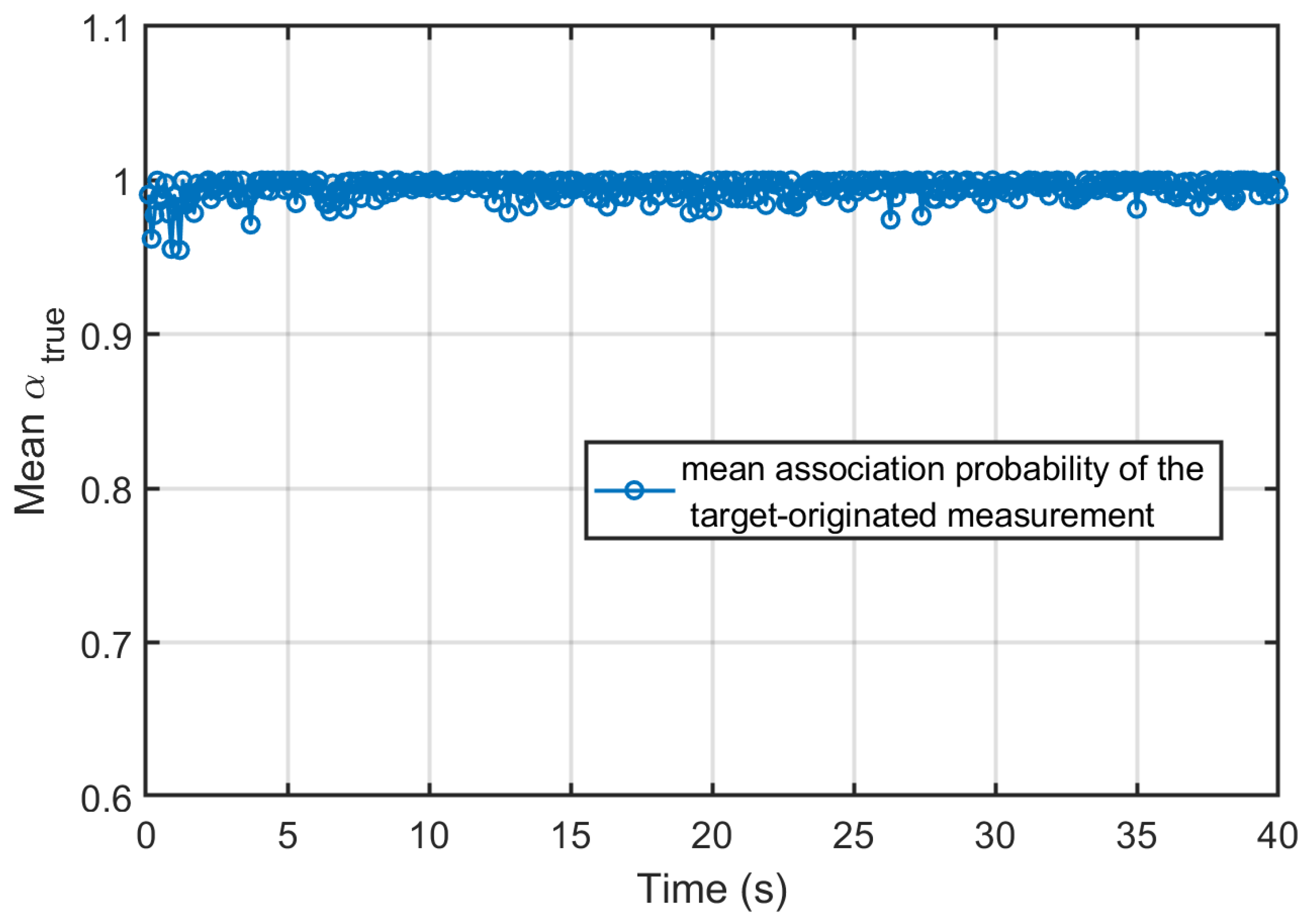

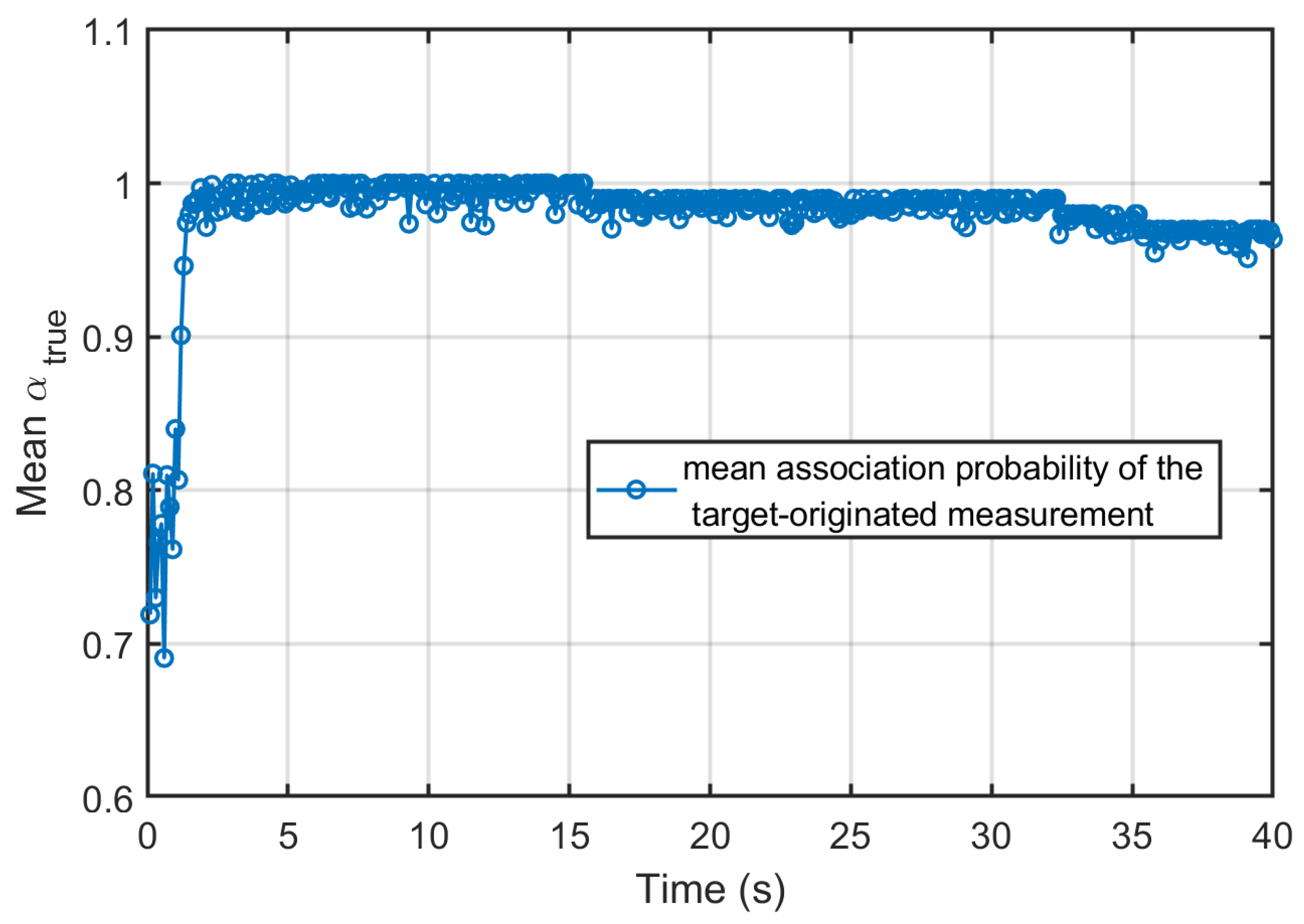

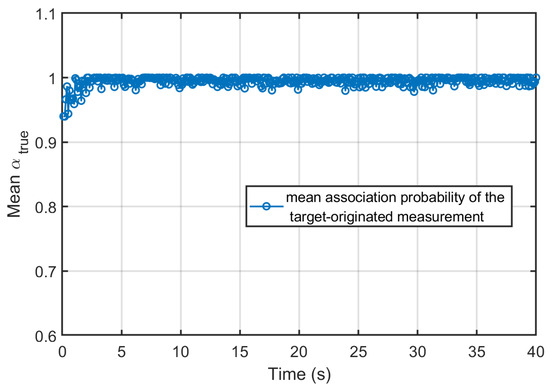

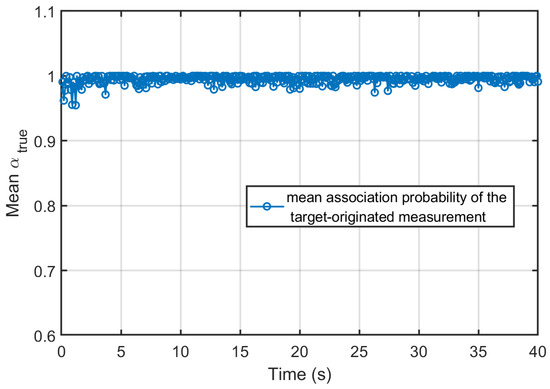

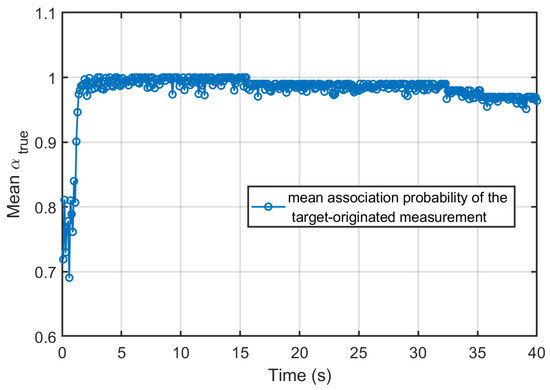

The Monte Carlo averaged association probabilities assigned to the true target-originated measurements by each local sensor are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. For most of the simulation duration, all three sensors maintain high association probabilities toward the true measurement, even in the presence of clutter points per scan. Importantly, these dips are narrow, and the probability rapidly recovers, indicating that no persistent misassociation or track loss occurs. Overall, the consistently high association probabilities and their rapid recovery demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the employed data association strategy under moderate-to-dense clutter conditions.

Figure 2.

Association probability of Sensor 1’s true measurement.

Figure 3.

Association probability of Sensor 2’s true measurement.

Figure 4.

Association probability of Sensor 3’s true measurement.

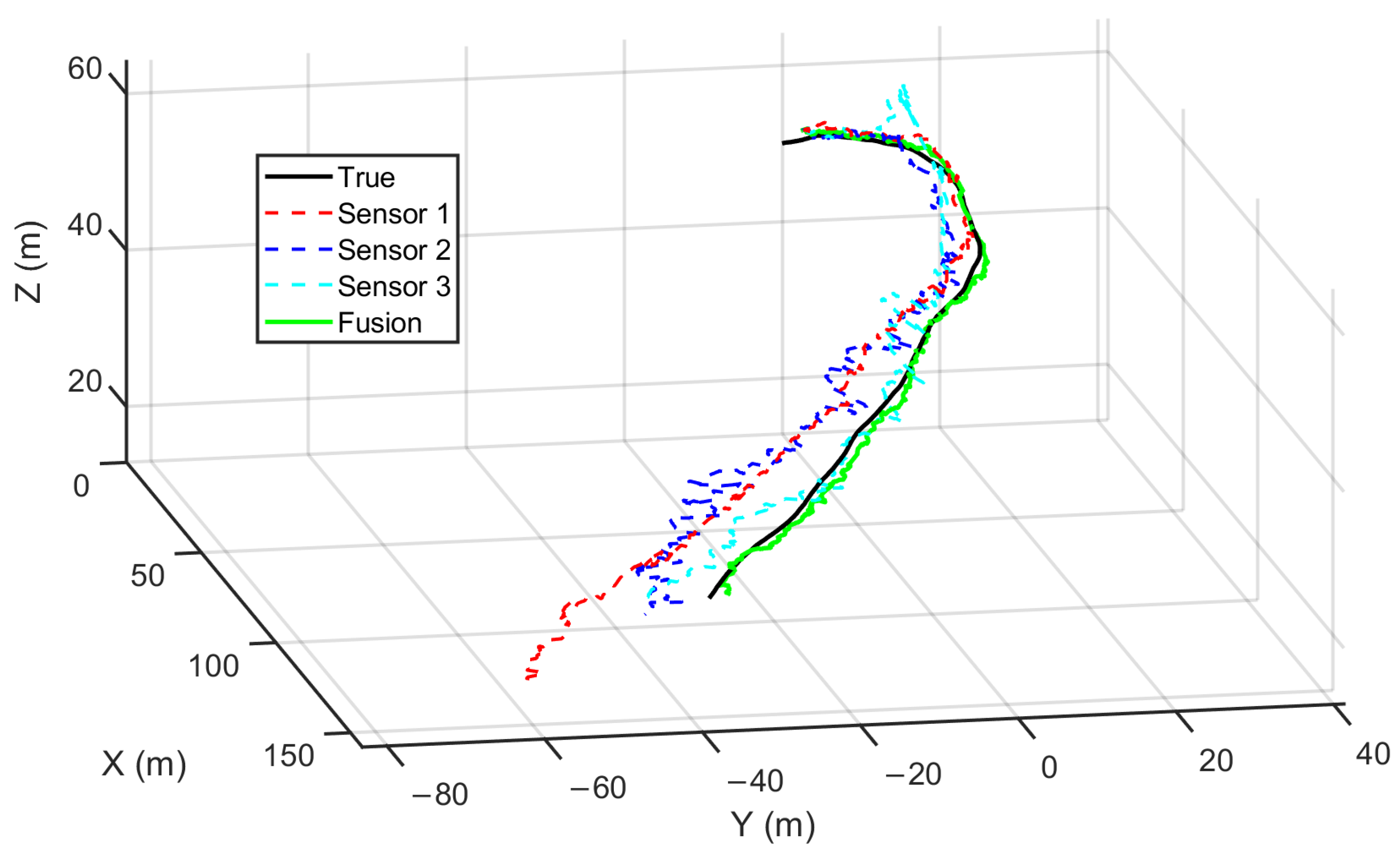

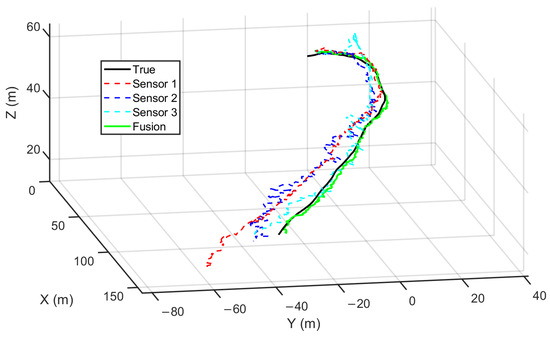

The overall tracking performance in the 3D Cartesian space from one of the Monte Carlo simulations is visualized in Figure 5. It is evident that the estimates from individual local sensors suffer from significant fluctuations and deviations from the true state. These inaccuracies are primarily attributed to two factors: the inherent partial observability of passive bearing-only measurements and the interference from the dense clutter environment. In contrast, the proposed fused estimate demonstrates superior robustness. By effectively aggregating the weighted information from distributed nodes, the fusion center compensates for the local deficiencies. The resulting global trajectory is smoother and adheres more closely to the true path, verifying the algorithm’s capability to maintain stable tracking even when individual sensor performance degrades.

Figure 5.

3D trajectory comparison from one representative Monte Carlo trial: the true target trajectory, local state estimates from each sensor, and the covariance-weighted fused estimate.

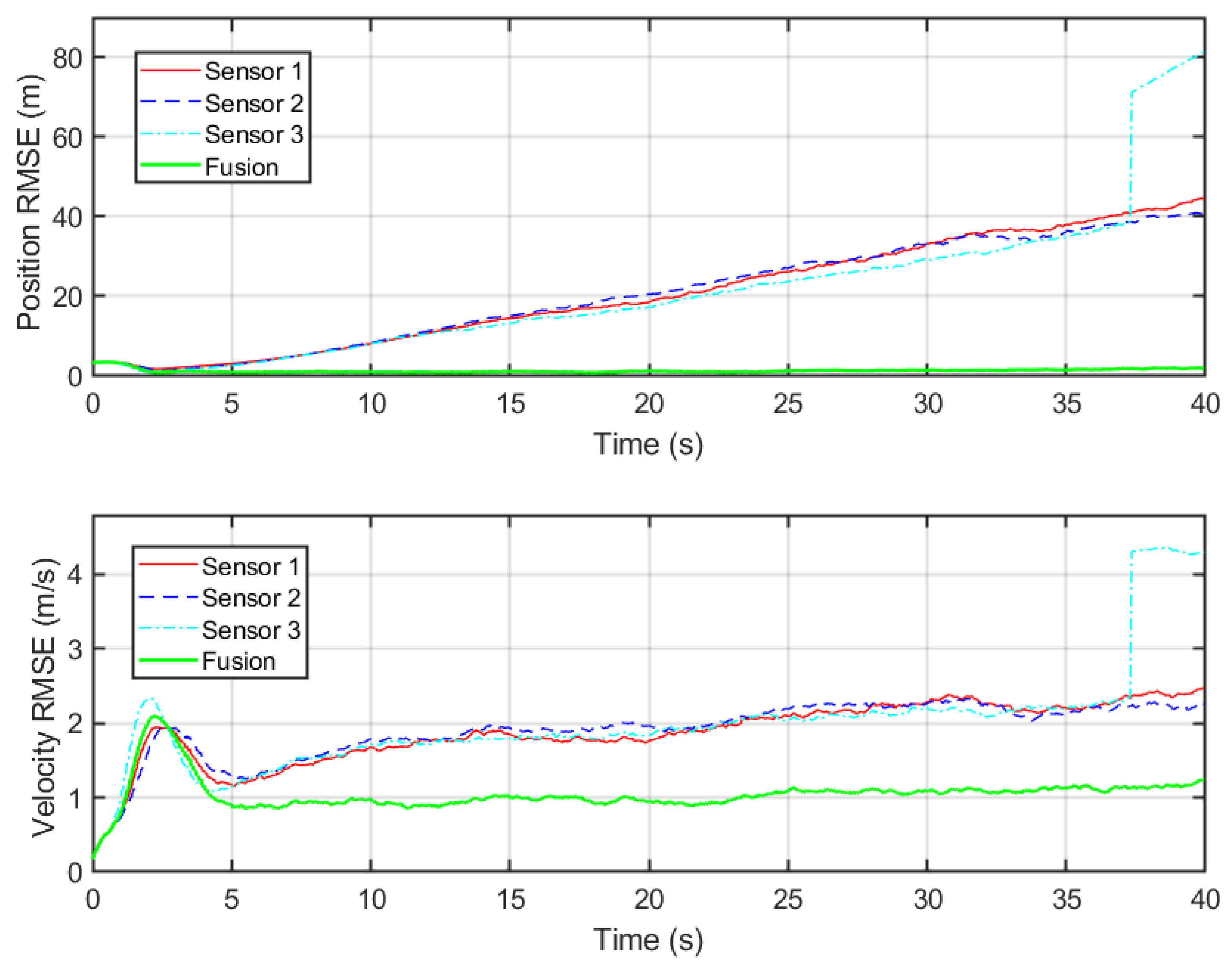

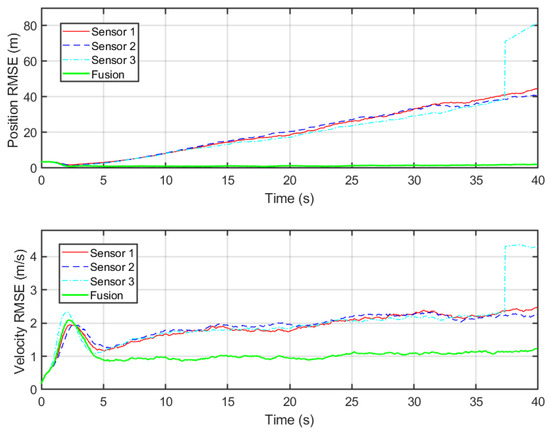

Figure 6 illustrates the statistical tracking performance, quantitatively evaluated using the RMSE. The top subplot illustrates the position RMSE, and the bottom subplot displays the velocity RMSE. It is shown that the position RMSE of the proposed fused estimate is consistently lower than that of any individual local sensor. A similar performance advantage is evident in the velocity domain. The fused velocity RMSE converges rapidly and stabilizes around 1 m/s. In contrast, local sensors exhibit higher fluctuations around 1.5 m/s to 2.5 m/s. This demonstrates the robustness of the distributed fusion architecture: the fusion rule adaptively down weights sensors with larger estimated uncertainty, preventing the global estimate from being contaminated by the local estimation degradation. Importantly, after a short initialization phase, both the position and velocity RMSEs settle and remain bounded over the entire time horizon. This bounded steady-state RMSE indicates that the distributed fusion filter converges to a stable tracking regime despite clutter and local sensor degradation.

Figure 6.

Monte Carlo averaged RMSE: position RMSE (top) and velocity RMSE (bottom) for each sensor and the fused estimate.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a DPDA-FPF algorithm for photoelectric tracking systems in three-dimensional bearing-only target tracking with clutter. By extending the PDA-FPF to a continuous–discrete formulation, the method explicitly accommodates the mismatch between continuous-time target dynamics and discrete-time optical measurements. A track-level distributed architecture was further developed, in which each photoelectric sensor performs local PDA-FPF processing and transmits compact state estimates and covariance information to a fusion center. Numerical simulations demonstrate that, although individual bearing-only trackers may suffer from observability degradation and clutter-induced fluctuations, the proposed covariance-weighted fusion effectively exploits multi-view geometry and yields substantially improved global tracking accuracy.

The proposed DPDA-FPF framework is able to deal with single-target tracking in moderate-clutter environments, but its performance may deteriorate in complex scenarios involving multiple closely spaced targets, missed detections, or significant sensor correlations. This is because of the inherent modeling assumptions, specifically the single-target constraint, idealized detection probabilities, and statistical independence, as well as the numerical approximations adopted for real-time feasibility, which restrict the accuracy of the particle flow in highly nonlinear or low signal-to-noise regimes. Extending the proposed methods to deal with multi-target tracking and realistic sensor imperfections is non-trivial. A possible direction can be combining the feedback particle filter with joint probabilistic data association or embedding it into random finite set frameworks to naturally account for target number variability and clutter density. Another future work will be developing correlation-aware distributed fusion strategies to address the potential inconsistency caused by neglected dependencies in large-scale sensor networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Q.; methodology, C.Q.; software, C.Q. and Y.L.; validation, C.Q., Y.L. and J.K.; formal analysis, C.Q., Y.L. and J.K.; investigation, C.Q.; visualization, C.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Q.; writing—review and editing, C.Q., Y.L., J.K., X.Z., Y.M. and D.H.; supervision, Y.M. and D.H.; project administration, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CV | Constant Velocity |

| DPDA-FPF | Distributed Probabilistic Data Association Feedback Particle Filter |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| FPF | Feedback Particle Filter |

| MMSE | Minimum Mean Square Error |

| PDA | Probabilistic Data Association |

| PDAF | Probabilistic Data Association Filter |

| PDA-FPF | Probabilistic Data Association Feedback Particle Filter |

| PF | Particle Filter |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| UKF | Unscented Kalman Filter |

References

- Nguyen, N.H.; Doğançay, K. Improved Pseudolinear Kalman Filter Algorithms for Bearings-Only Target Tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2017, 65, 6119–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.F.; Thangavel, K.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R. Passive Electro-Optical Tracking of Resident Space Objects for Distributed Satellite Systems Autonomous Navigation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, H.; Klein, I. BOTNet: Deep Learning-Based Bearings-Only Tracking Using Multiple Passive Sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, S.C.; Aidala, V.J. Observability Criteria for Bearings-Only Target Motion Analysis. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1981, AES-17, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, S.; Lindgren, A.; Gong, K. Fundamental Properties and Performance of Conventional Bearings-Only Target Motion Analysis. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1984, 29, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helferty, J.P.; Mudgett, D.R. Optimal Observer Trajectories for Bearings Only Tracking by Minimizing the Trace of the Cramer-Rao Lower Bound. In Proceedings of 32nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Antonio, TX, USA, 15–17 December 1993; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidala, V.J.; Nardone, S.C. Biased Estimation Properties of the Pseudolinear Tracking Filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1982, AES-18, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mušicki, D. Bearings Only Multi-Sensor Maneuvering Target Tracking. Syst. Control Lett. 2008, 57, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, E.; Tharmarasa, R.; Kirubarajan, T.; McDonald, M. Multisensor-Multitarget Bearing-Only Sensor Registration. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2016, 52, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, S.; Li, K.; Noack, B.; Hanebeck, U.D. Comparative Study of Track-to-Track Fusion Methods for Cooperative Tracking with Bearings-Only Measurements. In IEEE International Conference on Industrial Cyber Physical Systems (ICPS), Taipei, Taiwan, 6–9 May 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Chang, K.C.; Zhou, R. The Exact Algorithm for Multi-Sensor Asynchronous Track-to-Track Fusion. In 18th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 July 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 886–892. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Choi, J.W.; Xu, L.; Kim, H.J.; Ullah, I.; Khan, U. Distributed Target Tracking in Challenging Environments Using Multiple Asynchronous Bearing-Only Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aidala, V.J. Kalman Filter Behavior in Bearings-Only Tracking Applications. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1979, AES-15, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liao, S.; Xing, T. The Unscented Kalman Filter for State Estimation of 3-Dimension Bearing-Only Tracking. In International Conference on Information Engineering and Computer Science (ICIECS), Wuhan, China, 19–20 December 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, N.J.; Salmond, D.J.; Smith, A.F.M. Novel Approach to Nonlinear/Non-Gaussian Bayesian State Estimation. IEEE Proc. F Radar Signal Process. 1993, 140, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kang, J.; Yau, S.S.T. Time-Varying Feedback Particle Filter. Automatica 2024, 167, 111740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Mehta, P.G.; Meyn, S.P. Feedback Particle Filter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 58, 2465–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, S.; Morelande, M.R.; Mušicki, D.; Evans, R.J. Fundamentals of Object Tracking; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Shalom, Y.; Tse, E. Tracking in a Cluttered Environment with Probabilistic Data Association. Automatica 1975, 11, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, A.; Kandeepan, S.; Evans, R.J. Passive Radar Tracking in Clutter Using Range and Range-Rate Measurements. Sensors 2023, 23, 5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Pappas, G.J.; Atanasov, N. PKF: Probabilistic Data Association Kalman Filter for Multi-Object Tracking. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 11506–11513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilton, A.K.; Yang, T.; Yin, H.; Mehta, P.G. Feedback Particle Filter-Based Multiple Target Tracking Using Bearing-Only Measurements. In 15th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Singapore, 9–12 July 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 2058–2064. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Huang, G.; Mehta, P.G. Joint Probabilistic Data Association-Feedback Particle Filter for Multiple Target Tracking Applications. In American Control Conference (ACC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 27–29 June 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, T.; Blom, H.A.P.; Mehta, P.G. The Continuous-Discrete Time Feedback Particle Filter. In American Control Conference (ACC), Portland, OR, USA, 4–6 June 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Shalom, Y.; Fortmann, T.E. Tracking and Data Association; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Berntorp, K.; Grover, P. Feedback Particle Filter with Data-Driven Gain-Function Approximation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2018, 54, 2118–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.