Abstract

The rapidly increasing demand for compact, high-performance beam-steering solutions in LiDAR systems has driven substantial advances in vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser (VCSEL) technologies. In this paper, we present a high-power, ultra-low-divergence VCSEL-based beam scanner array that integrates multi-wavelength seed lasers with extended-length optical amplifiers, thereby simultaneously achieving wide-angle beam steering, near-diffraction-limited beam quality, and watt-class output power. The proposed architecture exploits slow-light modes supported by laterally extended VCSEL waveguides incorporating precisely engineered surface gratings. This design enables fully electronic beam steering over an angular range exceeding 30°, with an angular resolution surpassing 1600 resolvable points. Systematic characterization of seed lasers with distinct grating periods confirms robust single-mode operation and yields a cumulative wavelength tuning range exceeding 22 nm. When integrated with optical amplifiers up to 6 mm in length, the system achieves a record-low beam divergence of 0.018°, approaching the theoretical diffraction limit. Under continuous-wave operation and without active thermal management, the device delivers output powers exceeding 1.6 W. By overcoming the long-standing trade-offs among steering range, beam quality, and output power, this work establishes a transformative paradigm for compact VCSEL-based beam-steering systems and represents a significant step toward next-generation solid-state LiDAR technologies.

1. Introduction

The emergence of modern artificial life—characterized by the seamless integration of advanced technologies into daily human activities—has profoundly transformed the interaction between humans and their environment. From smart cities to autonomous transportation systems, intelligent technologies have redefined paradigms of convenience, safety, and operational efficiency [1,2,3]. Central to this transformation is the capability of machines to accurately perceive, interpret, and navigate the physical world—functions that are largely enabled by advanced sensing technologies, among which Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) plays a pivotal role [4].

LiDAR has become a key enabling technology for autonomous systems, particularly in autonomous vehicles, where it provides robust environmental perception and navigation functions [5]. By emitting laser pulses and measuring their Time of Flight (ToF), LiDAR systems generate high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) point clouds of the surrounding environment. These 3D representations enable autonomous platforms to detect obstacles, plan trajectories, and operate safely in complex and dynamic environments, representing a significant advancement toward fully autonomous mobility [6]. LiDAR technologies are broadly classified into two principal categories according to their operational mechanisms: Flash LiDAR and Scanning LiDAR [7]. Flash LiDAR illuminates the entire target scene with a single, broad laser pulse, while a two-dimensional (2D) detector array—typically based on CMOS or CCD technology—simultaneously captures the backscattered light to reconstruct a 3D image in a single acquisition. This architecture eliminates the requirement for mechanical beam steering and offers inherently fast imaging. However, its spatial resolution is fundamentally limited by the pixel density of the detector array, and achieving a wide field of view (FOV) remains challenging due to constraints on optical power distribution and detector sensitivity [4,5,7].

In contrast, Scanning LiDAR employs a narrow, tightly focused laser beam that is sequentially steered across the scene using mechanical scanners, micro-electromechanical systems (MEMSs), or solid-state beam-steering technologies such as optical phased arrays (OPAs) [5,7]. The reflected signal from each angular position is collected by a photodetector, and a high-resolution 3D point cloud is reconstructed through spatial aggregation. Scanning LiDAR systems offer superior angular resolution, extended detection range, and flexible scan pattern control, making them particularly attractive for applications requiring high precision. Nevertheless, conventional beam-steering mechanisms introduce challenges related to system complexity, mechanical reliability, scalability, and manufacturing cost [4,5,7].

Recent advances in semiconductor laser sources, photodetectors, and beam-steering technologies have significantly enhanced the performance, reliability, and scalability of both Flash and Scanning LiDAR systems [8,9]. These developments are accelerating the integration of LiDAR across a wide range of applications, including autonomous vehicles, robotics, industrial automation, and smart urban infrastructure [8]. The performance of LiDAR systems is fundamentally contingent upon the characteristics of their optical sources, which must simultaneously deliver high output power, excellent beam quality, and long-term operational stability [9].

Vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) have emerged as a disruptive enabling technology for LiDAR applications [10,11,12]. VCSELs offer circular beam profiles, low threshold currents, high wall-plug efficiency, and excellent manufacturability, making them ideally suited for dense two-dimensional array integration [13]. Their compact footprint, wafer-level fabrication, and cost-effective production facilitate large-scale deployment in next-generation photonic systems [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Consequently, VCSELs have become a primary focus of research in solid-state beam-steering technologies.

MEMS-actuated polymer microlenses have demonstrated substantial angular deflection performance. By laterally displacing the microlens relative to the VCSEL emission axis, beam steering angles of up to 14° have been reported [15,16]. While effective, mechanically actuated systems pose challenges in reliability, speed, and fabrication complexity. Non-mechanical beam-steering techniques based on coupled VCSEL arrays have also been explored. In these systems, beam steering is realized through dynamic control of mutual coherence among adjacent emitters via current-induced refractive index modulation, which enables precise phase tuning across the array [17,18]. Although this approach eliminates moving parts, the achievable steering range remains limited by the array geometry and phase control accuracy. Liquid-crystal-based electro-optic phase modulation represents another solid-state alternative, enabling beam steering over angular ranges of approximately 6° without mechanical motion [19]. Recent advances integrate metasurfaces with VCSELs for beam steering via nano-antenna wavefront control, enabling ultrafast, compact devices [20,21,22]. However, fabrication complexity, limited efficiency, and power scalability remain key challenges.

Despite significant advancements, VCSEL-based beam-steering technologies face fundamental limitations. These include fabrication complexity, limited optical output power, constrained beam quality and narrow FOV, which collectively restrict detection range and overall system-level performance [5,8,9,10,11,12,13].

A slow-light mode confined by Bragg reflectors offers a solution to these challenges, serving as a new compact beam scanner [23,24]. The VCSEL structure introduces an active waveguide amplifier for slow-light modes, enabling wide beam steering exceeding 60°, an angular resolution of more than 1000 points, and watt-level optical power [25,26,27,28]. In early slow-light beam scanners, an external tunable laser was used to excite single slow-light mode in a VCSEL amplifier, which is incompatible with compact, monolithic LiDAR systems. To address this limitation, various integration strategies have been explored, including thermally tunable VCSELs, MEMS-actuated air-gap-mirror VCSELs, and, more recently, surface-grating VCSELs (SG-VCSELs) have been reported in Refs. [25,26,27,28,29] and related references therein.

The slow-light VCSEL amplifier demonstrates high beam-steering stability over varying temperatures, with an angular dispersion of 0.0075°/K, indicative of stable CW operation [29]. In our laboratory measurements, high output power was achieved using single-probe current injection; however, beam divergence increases at elevated currents due to non-uniform current distribution and self-heating effects [27]. In contrast, Fuji Xerox [28] employed stacked probes with more than ten contacts and active cooling, substantially improving current uniformity and enabling higher CW output power (>2 W for a 6 mm amplifier) with reduced beam divergence. The thermal robustness of the slow-light amplifier primarily arises from its millimeter-scale long aperture, which significantly lowers differential resistance compared to conventional small-aperture VCSELs [30,31] for example, a 6 mm device exhibits a differential resistance of ~1 Ω. Furthermore, distributing the optical output along the amplifier length mitigates self-heating, enhances thermal stability, and helps prevent catastrophic optical mirror damage [27,28].

The beam scanner consists of a long aperture of 0.5 mm SG-VCSEL that operates as a seed laser, integrated with a 4 mm long VCSEL waveguide without a surface grating that functions as an optical amplifier. The single-mode seed laser excites the slow-light mode in the amplifier. A fan-shaped output beam with an optical power exceeding 3 W is obtained [29]. However, the current-induced tuning range is limited to 4 nm, which restricts the steering range to approximately 9°.

In our previous work, two cascaded seed lasers with different grating periods were demonstrated to further expand the FOV of the beam scanner. Subsequent improvements utilizing a counter-propagating configuration extended the FOV to 22° [32,33]. Additionally, the incorporation of diffractive optical elements (DOEs) within the amplifier has been proposed to achieve steering angles exceeding 64° [33]. Although diffractive optical elements (DOEs) effectively expand the angular field of view, they inherently impose an optical power penalty due to multi-order beam splitting. This trade-off is detrimental for long-range LiDAR systems that require high output power.

In this paper, we present a monolithic VCSEL beam scanner array designed to expand the FOV while maintaining the high output power required for LiDAR applications. The system comprises a 5 × 1 integrated SG-VCSEL-amplifier array. Within the array, each SG-VCSEL incorporates a distinct grating period to select a specific emission wavelength, thereby expanding the overall steering range. While the amplifier length is fixed within a given array, it is systematically varied from 2 mm to 6 mm across different fabricated arrays to evaluate performance scaling. The experimental results show that the proposed beam-steering system achieves a maximum angular steering range of 30.25° and a minimum beam divergence of 0.018°, corresponding to an angular resolution exceeding 1600 resolvable points with an output beam power of 1.6 W.

2. Principle of Work and Device Fabrication

The vertical structure is identical to that of a conventional VCSEL, comprising top and bottom distributed Bragg reflectors (DBRs). A one-wavelength (λ) cavity formed between the DBRs incorporates an active region containing three quantum wells (QWs). The oxide aperture is engineered to be sufficiently narrow along the x-axis to ensure single transverse-mode operation, while being laterally extended along the y-axis to support propagation of slow-light modes.

These modes exhibit low group velocity and are therefore characterized by a high group index, an effective refractive index lower than unity (equivalent index [34]), and strong optical confinement with enhanced modal gain [25,29,35]. This results in a pronounced angular dispersion of 2° nm−1 [29]. The aperture length along the y-direction can be extended to a millimeter or even centimeter scale to reduce beam divergence [28]. Surface emission distributed along the entire aperture length enables high optical output power without the limitation of catastrophic optical mirror damage [36]. Furthermore, the millimeter-scale aperture length substantially reduces the electrical resistance (from >50 Ω to ~1 Ω for a 6 mm device), thereby mitigating self-heating [28,36,37].

The gratings etched on the device surface provide sufficient coupling to select a single slow-light mode, while the first-order grating period can be in the order of micrometers due to the low effective refractive index [29,36]. This structure operates as a laser architecture that combines key advantages of edge-emitting distributed feedback (DFB) lasers and conventional single-mode VCSELs [36]. The far-field pattern (FFP) of the slow-light surface-grating VCSEL is fixed at a specific angle and remains stable under variations in injection current, while exhibiting a wavelength tuning range of approximately 4 nm [29,36]. When the output is coupled into the amplifier section, the beam is forced into single-mode operation and steered via current-induced wavelength tuning in the laser section [29]. Therefore, the integration of an SG-VCSEL with an amplifier is well suited for high-resolution beam-scanning applications [29,32,33].

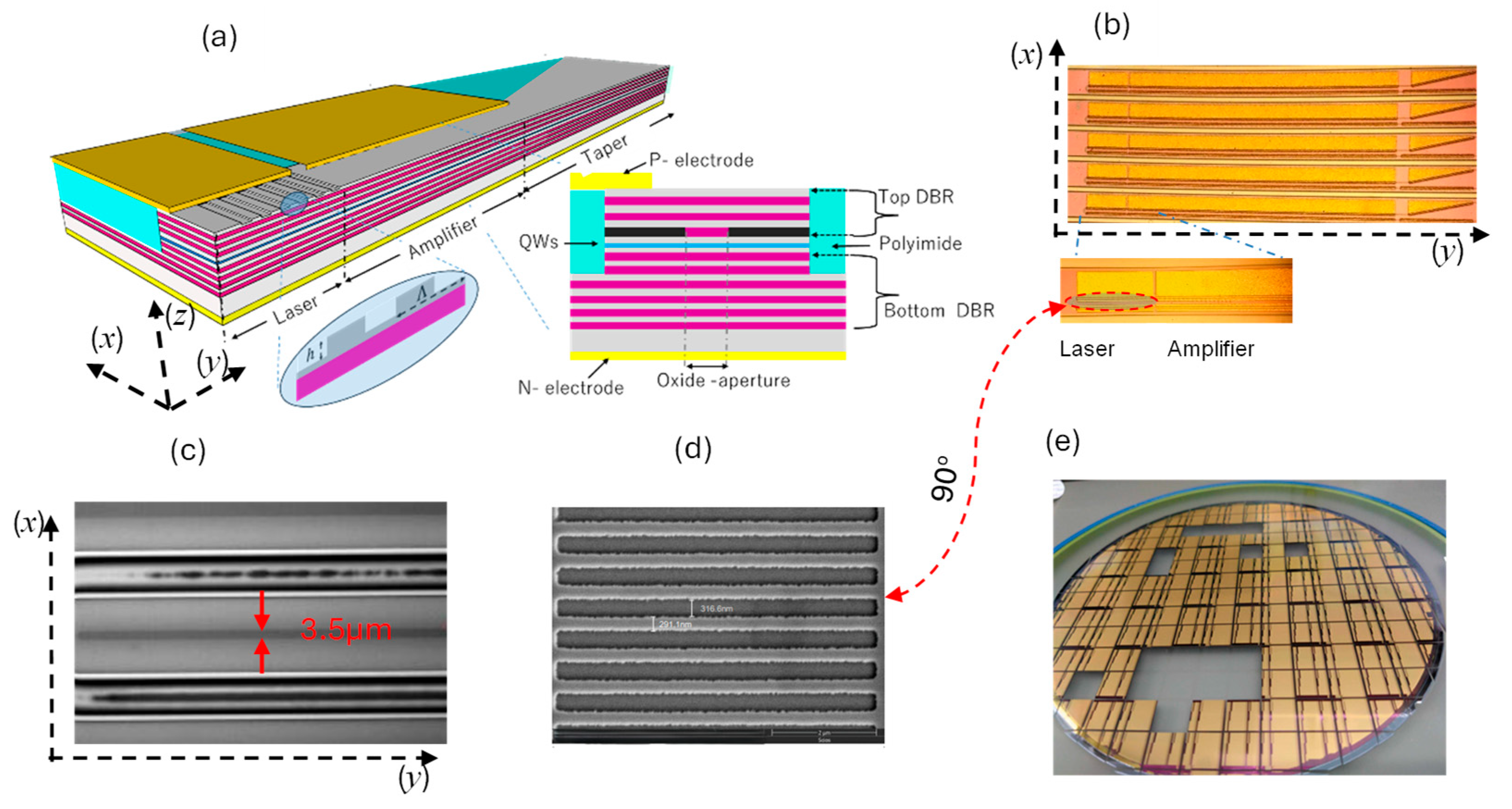

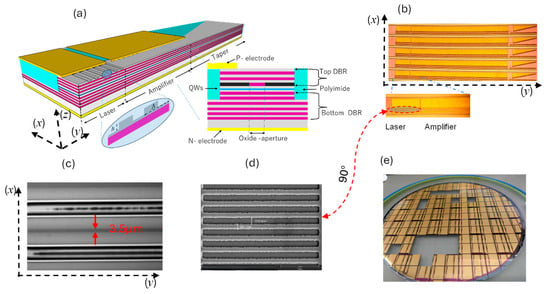

Each beam-scanner unit consists of three sections, as shown in Figure 1a. The first section is a 0.3 mm surface-grating seed laser that enforces single-mode operation. The second section is a grating-free optical amplifier that amplifies the slow-light mode excited by the seed laser, enabling beam steering. Independent p-type electrodes allow separate biasing of the laser and amplifier sections. Injection-current-induced tuning shifts the seed laser wavelength, enabling continuous electronic control of the FFP deflection angle [29,32,33]. The third section, located at the end of amplifier, is 0.5 mm long and features a tapered geometry with a 10° taper angle, which promotes unidirectional propagation and suppresses parasitic feedback, thereby preventing unwanted lasing in the amplifier section.

Figure 1.

VCSEL beam-steering device. (a) Schematic diagram of integrated device sections in lateral and transverse structures. (b) A microscope photo shows the top view of fabricated devices. (c) A photo of device after oxidation shows the oxide aperture. (d) Surface gratings of 25 nm depth. (e) A photo of a 6-inch fabricated wafer.

Device fabrication followed standard VCSEL processing [14,36]. A 6-inch, 940 nm VCSEL wafer (Figure 1e) was fabricated at a commercial foundry based on our design. The epitaxial structure comprises p-type top and n-type bottom AlGaAs DBRs, with an active region of three InGaAs QWs. The material gain peak was detuned by ~15 nm from the cavity resonance [29,36], and the top DBR mirror pairs were reduced to 19 to improve optical extraction efficiency. Arrays with amplifier lengths of 2, 4, and 6 mm were fabricated, all maintaining a uniform oxide aperture width of 3.5 μm across the laser and amplifier sections (Figure 1b,c).

A wet-etched 30 nm surface grating provides optimized coupling for selective slow-light mode excitation [29,36]. Five distinct surface-grating periods were designed and fabricated: SR1 = 0.5 μm, SR2 = 0.6 μm, SR3 = 0.7 μm, SR4 = 0.8 μm, and SR5 = 1.0 μm, with SR1–SR4 spaced by 100 nm. All devices operate in the first-order diffraction regime [37]. The investigated VCSEL array comprises five grating configurations arranged in a 5-unit linear array.

As in DFB lasers, the emission wavelength λ for each grating configuration is governed by the Bragg condition [38]:

where Λ denotes the grating pitch period and Neff represents the effective refractive index of the slow-light mode confined the VCSEL waveguide. The corresponding deflection angle θ of the emitted beam is determined by the phase-matching condition between the slow-light mode and the radiated free-space mode, expressed as [25]:

where λc denotes the wavelength of the vertical cavity resonance and Nw is the refractive index of the VCSEL waveguide core.

3. Results

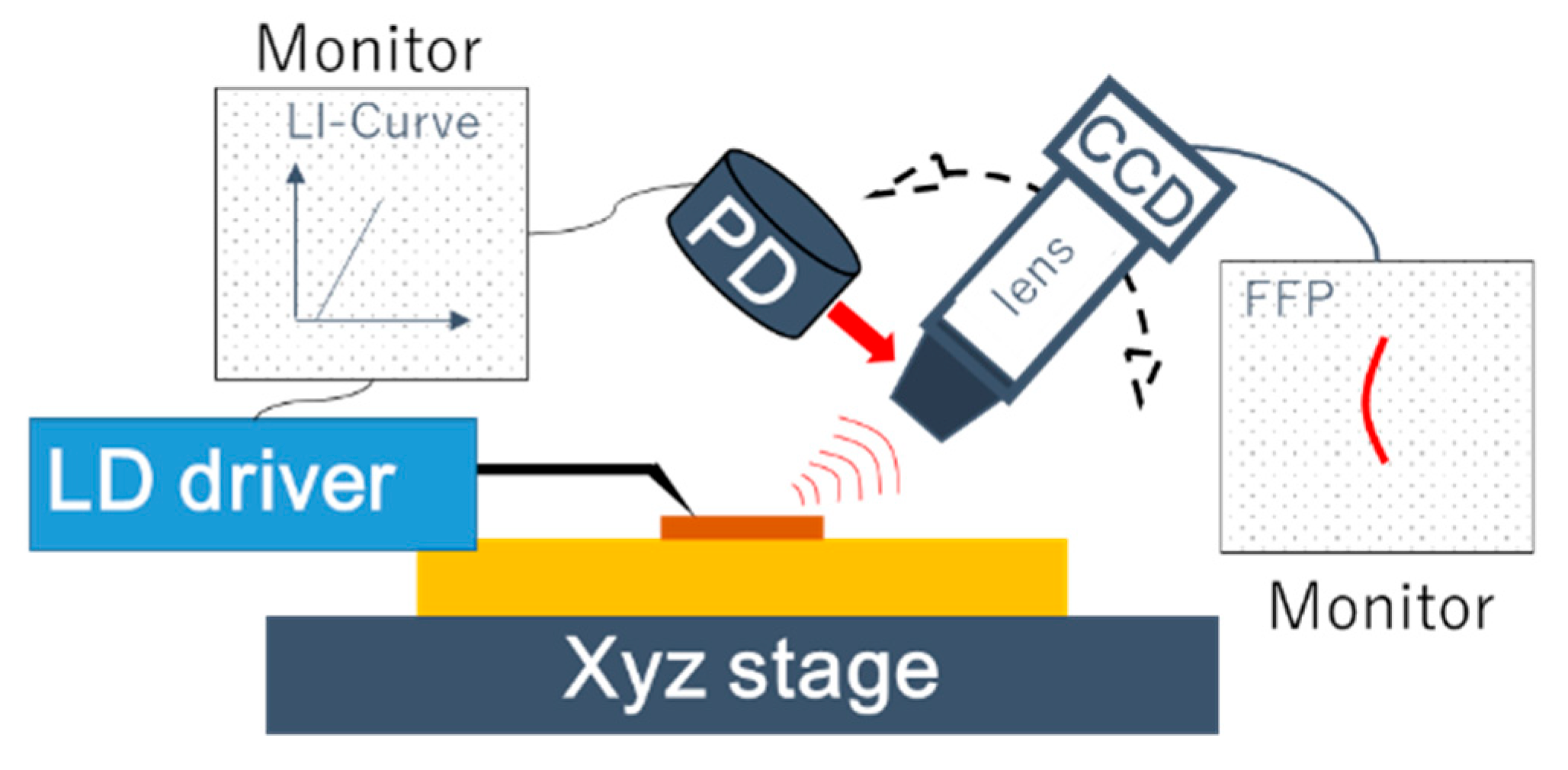

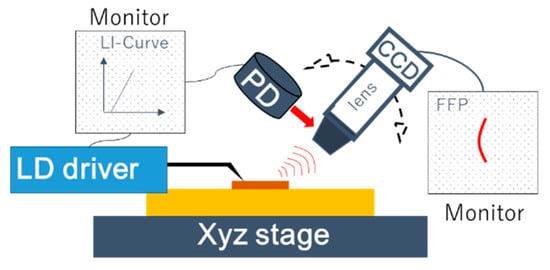

The experimental setup used for device characterization is schematically illustrated in Figure 2. The FFP of the fabricated beam scanner was analyzed using a high-resolution optical measurement system (Synos M-Scope, Synergy Optosystems Co., Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan). To accurately capture the emitted beam profile, the CCD camera was mounted on a precision rotational stage, enabling precise alignment with the oblique emission angle (θ) of the amplified slow-light mode. Spectral measurements were performed using a multimode optical fiber (MMF) tilted at the emission angle θ to match the propagation direction of the slow-light mode. The MMF was connected into an optical spectrum analyzer (AQ6317, Ando Electric Co., Tokyo, Japan; now Yokogawa Electric Corp.) with a spectral resolution of 0.02 nm.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrates experimental setup used in measurements of beam steering.

Light–current (L–I) characteristics were measured under continuous-wave (CW) operation using a calibrated silicon photodiode with a 10 mm aperture diameter. Two independent current probes were employed to separately bias the seed laser and amplifier sections, enabling precise control and independent optimization of each region. Each device in the 5 × 1 array was systematically characterized across its full operating current range. All measurements were performed at room temperature without thermal control, reflecting practical LiDAR conditions.

3.1. Seed Laser Characterization

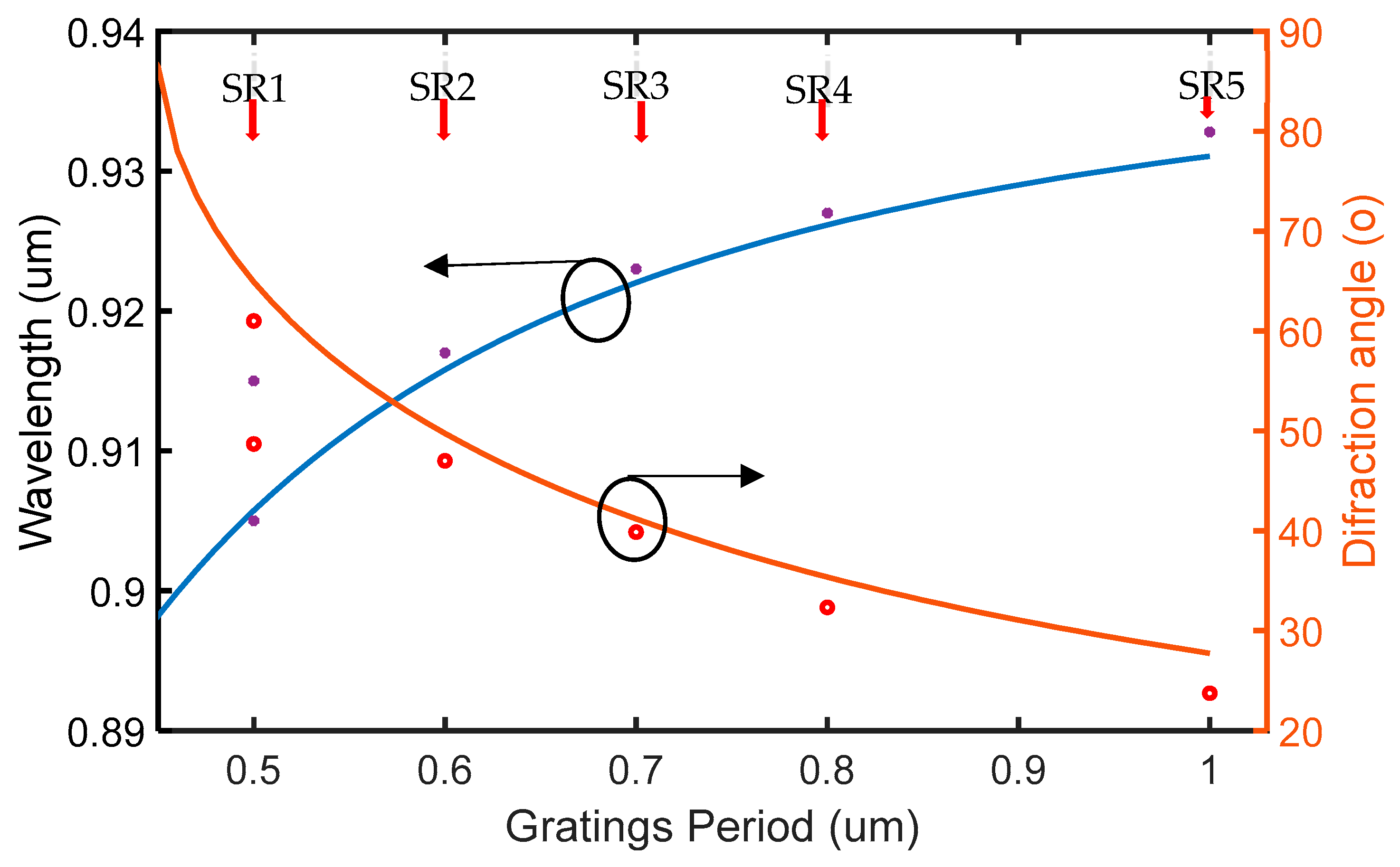

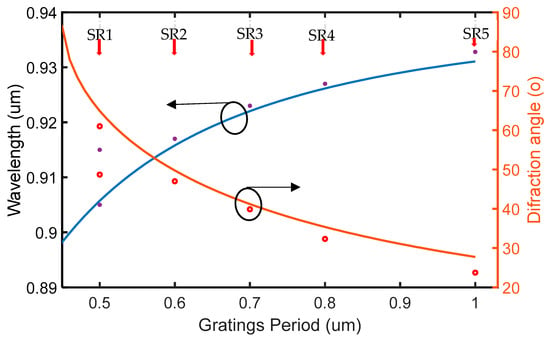

Initial characterization focused on the lasing performance of each device in the 5 × 1 seed-laser array. The emission wavelength and corresponding far-field deflection angle (θ) were measured at a near-threshold injection current of 50 mA, as summarized in Figure 3. The experimentally measured wavelengths and diffraction angles exhibit excellent agreement with theoretical predictions derived from Equations (1) and (2). The observed fixed emission angles across devices are consistent with those previously reported in [29,36,37].

Figure 3.

Theoretically calculated (solid line) and experimentally obtained (discrete points) wavelengths and far-field diffraction angles for all surface grating lasers in the array as a function of grating period length.

The SR1 device shows dual-wavelength emission at 905.7 nm and 915.2 nm. The 905.7 nm mode is weakly amplified due to detuning from the material gain peak, while the 915.2 nm mode, better aligned with the gain peak, exhibits higher SMSR and stronger coupling to the slow-light mode, dominating the output spectrum. The 905.7 nm emission, radiating at ~60° from vertical, suffers reduced modal gain and amplification efficiency.

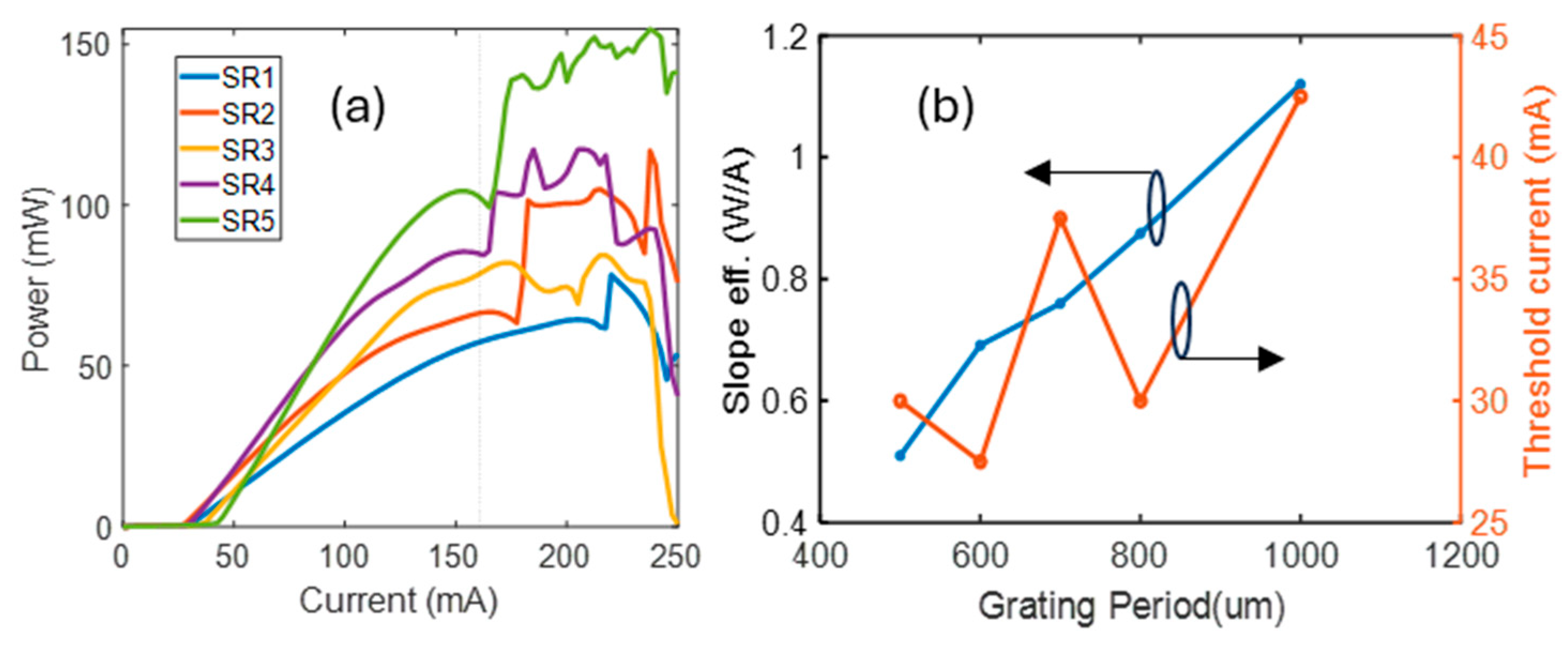

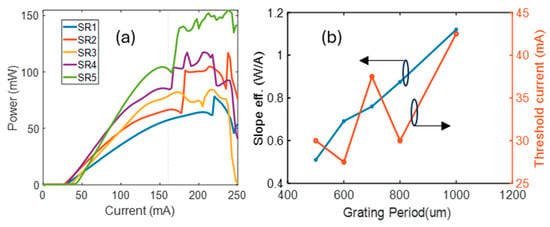

Figure 4a presents the L–I characteristics of all five seed lasers in the array. Above an injection current of approximately 160 mA (doted line), oscillatory behavior appears in the L–I curves. This behavior is attributed to increasing thermal effects, optical coupling between the seed laser and amplifier sections, and interactions with the oxide-confined region located on the opposite side of the device. As shown in Figure 4b, the slope efficiencies exhibit an approximately linear dependence on the grating period, reflecting variations in optical gain across the wavelength regions selected by the different grating pitches. With increasing injection current, thermal effects induce a red shift in the gain spectrum, leading to enhanced slope efficiency for devices with longer grating periods. Among the array, the SR5 device achieves the highest slope efficiency of 1.12 W/A. The maximum injection current applied to the seed lasers was 250 mA. Variations in roll-over behavior and threshold current among devices are primarily attributed to small fluctuations in oxide aperture geometry, as also reflected in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

(a) L–I curves for all five seed lasers from SR1 to SR5. A dotted line shows that 160 mA is approximately the boundary before output fluctuation occurs due to heat effects. (b) Slope efficiencies and threshold currents for all five lasers, plotted against the grating period length on the x-axis.

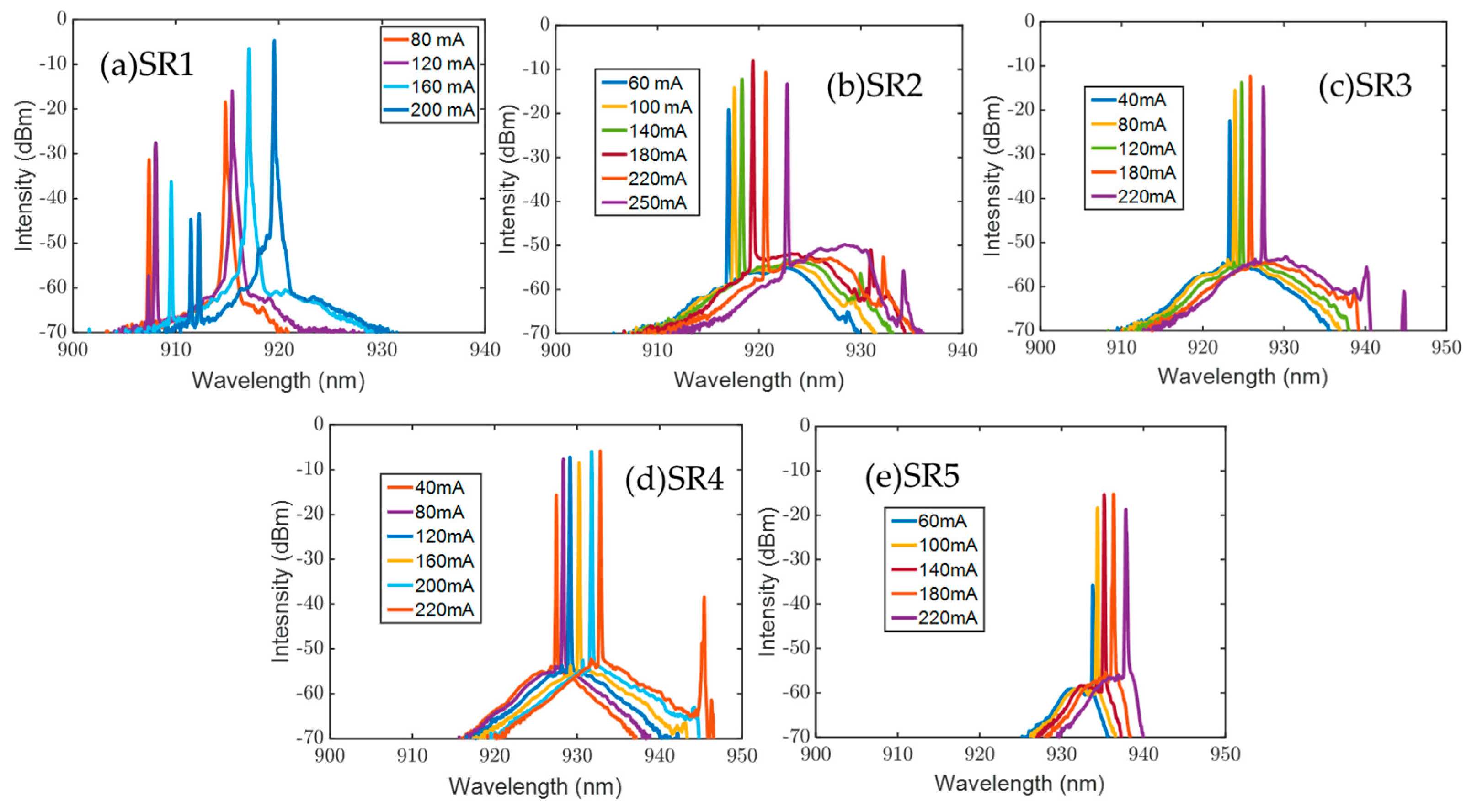

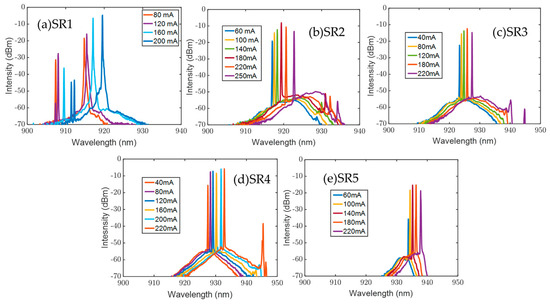

The wavelength spectra of all seed lasers were recorded over a 50 nm spectral span in order to capture both slow-light modes and any residual vertical-cavity emission modes. Figure 5 shows representative spectra, confirming stable single-mode operation; except for SR1, all seed lasers exhibit single slow-light mode lasing with SMSRs > 40 dB.

Figure 5.

(a–e) Spectra of seed lasers at different injection currents. The measurement span is 50 nm to display all possible modes.

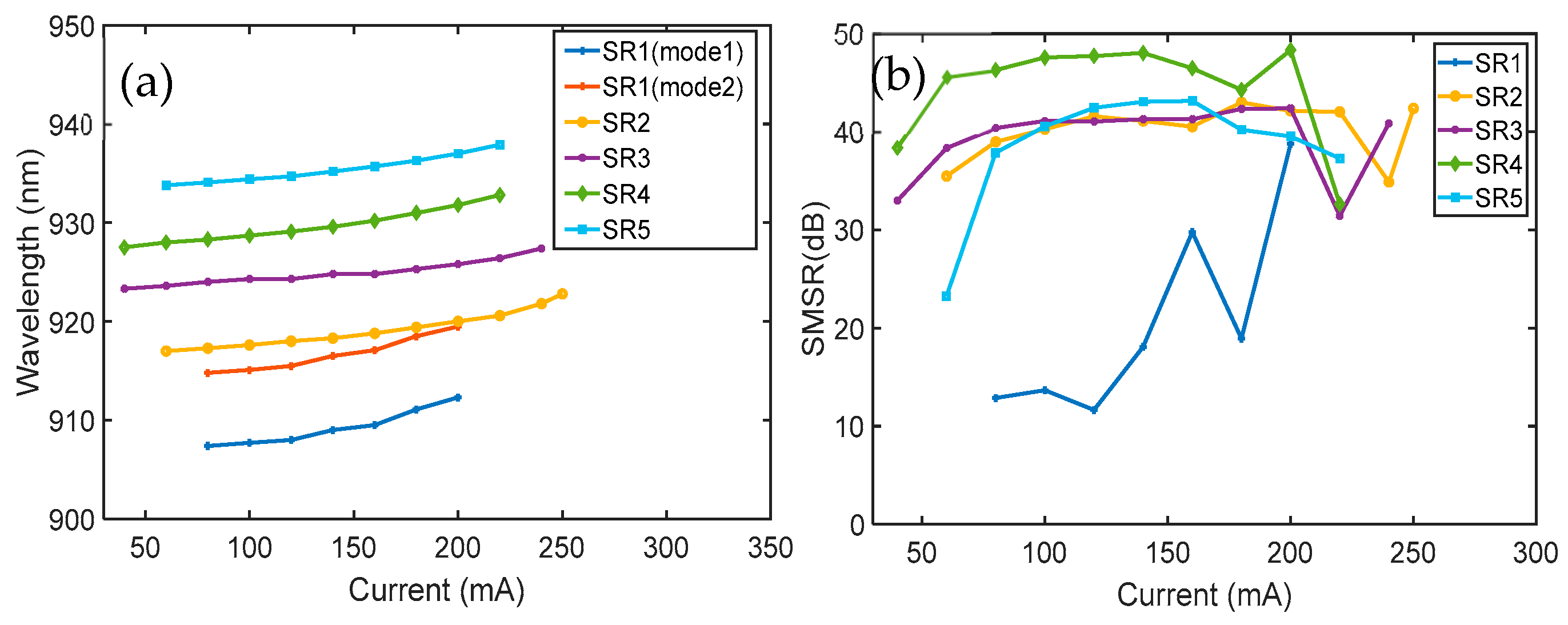

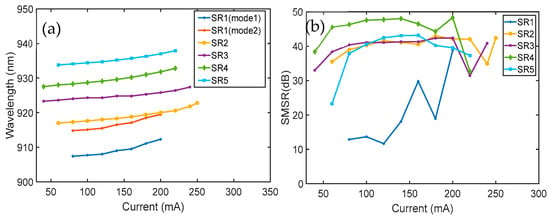

For SR1, dual-mode operation is observed, consisting of a weak mode at approximately 905 nm and a dominant mode near 915 nm, which is closer to the material gain peak. At high injection currents, SR2–SR4 show weak spectral features corresponding to vertical-cavity-like modes. Nevertheless, slow-light-mode lasing remains dominant, and SMSRs remain above 30 dB throughout the operating current range, indicating that parasitic vertical modes do not significantly degrade beam quality or spectral purity. Figure 6a,b show the wavelength tuning characteristics and corresponding SMSR values of all seed lasers as functions of injection current. The SR1 device exhibits a tuning range of 4.7 nm for its dominant mode, while SR2 demonstrates the largest tuning range of 5.8 nm. Devices SR3, SR4, and SR5 exhibit tuning ranges of 4.1 nm, 5.3 nm, and 4.1 nm, respectively. These variations mainly result from differences in the maximum usable current before roll-over, influenced by slight oxide aperture variations.

Figure 6.

(a) Tuning wavelengths of the seed lasers and (b) SMSR of each laser as a function of injection current.

Spectral overlap between adjacent seed lasers was also analyzed to evaluate the continuity of wavelength coverage across the array. An overlap of 2.5 nm is observed between SR1 and SR2, while SR2 and SR3 exhibit an overlap of 0.5 nm. The overlap between SR3 and SR4 is reduced to 0.1 nm, whereas SR4 and SR5 exhibit an overlap of approximately 1 nm. In future iterations of this design, increasing the spectral overlap between adjacent seed lasers will be a key objective to ensure operation within the linear region of the L–I characteristics for all devices. The corresponding SMSR values over the full operating current range are shown in Figure 6b. Among the array, SR4 achieves the highest SMSR of 48.32 dB at an injection current of 200 mA. Devices SR2 through SR5 consistently maintain SMSR values exceeding 40 dB across their operating ranges. In contrast, SR1 exhibits the lowest SMSR, reflecting its inherent dual-mode lasing behavior.

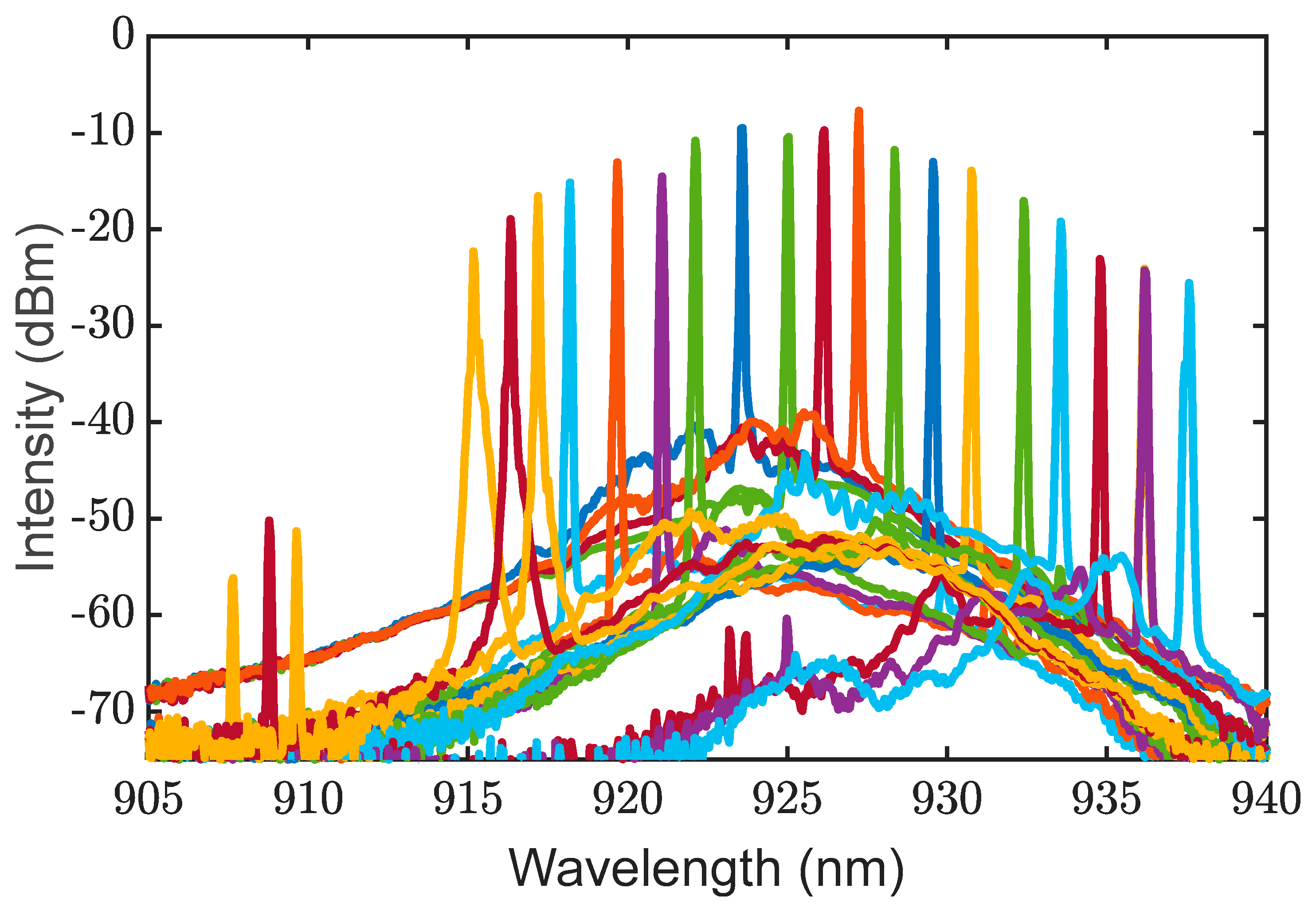

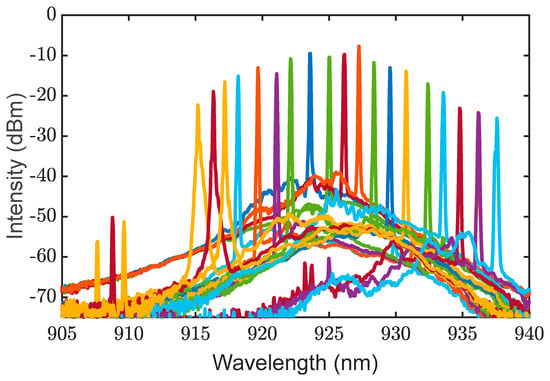

3.2. Integrated Beam Scanner Characterization

Following the characterization of the seed lasers, the performance of the monolithically integrated beam scanner was evaluated. Independent electrodes enable separate control of the laser and amplifier sections. The spectra of all 2 mm amplifier sections, biased at 250 mA, were measured while the seed-laser current was varied from 60 mA to 220 mA as shown in Figure 7. All amplifier spectra span 22.4 nm, closely matching the seed-laser spectral range, using the same measurement method as for the seed lasers. For the SR1 device, only the mode located near the material gain peak is efficiently amplified, resulting in an SMSR exceeding 30 dB at the amplifier output. This selective amplification behavior is consistently observed across all devices in the array and confirms that the amplifier preferentially enhances the slow-light mode with the highest net modal gain.

Figure 7.

Spectra of amplified light through the amplifier for the 5 × 1 laser array.

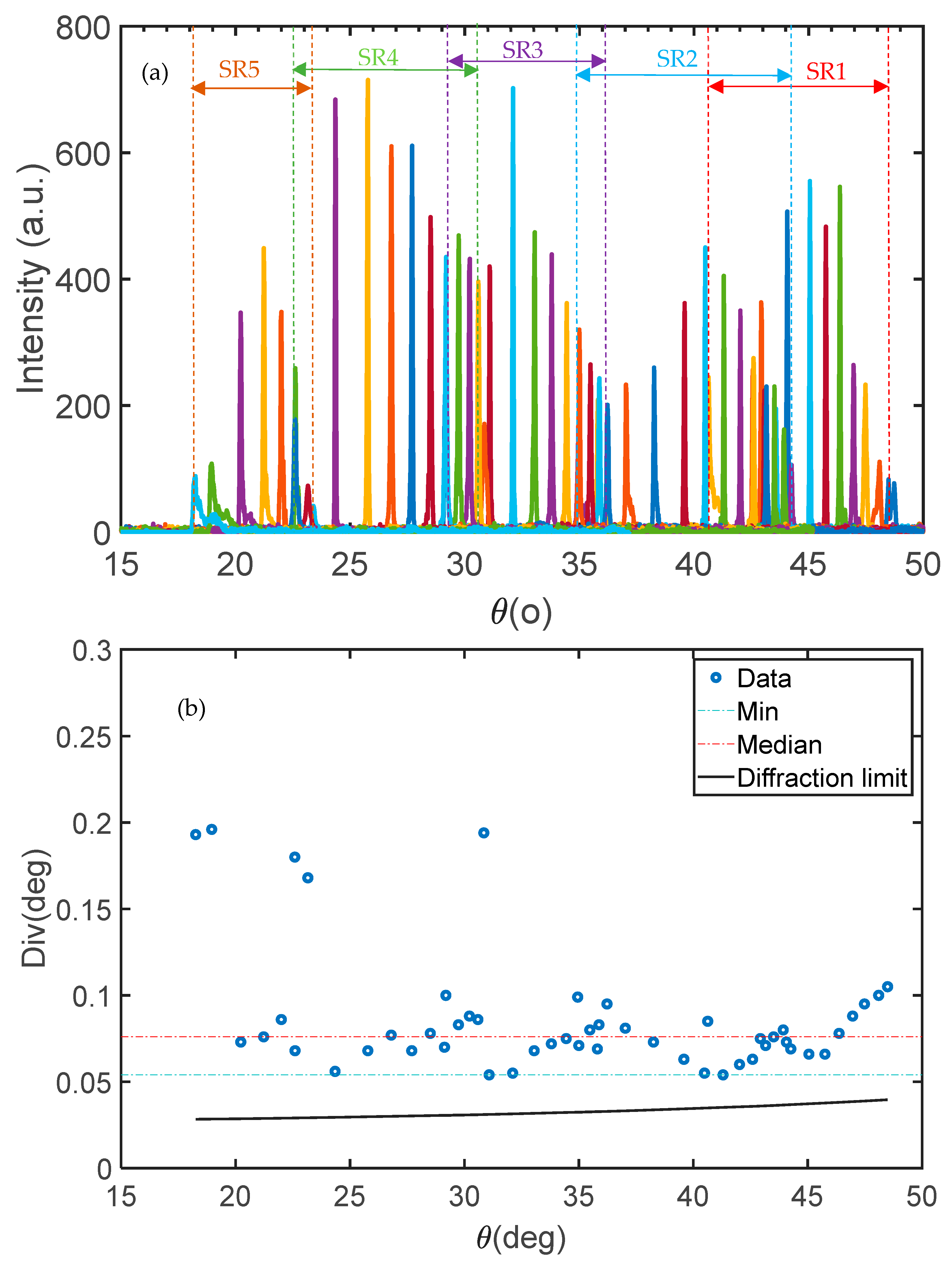

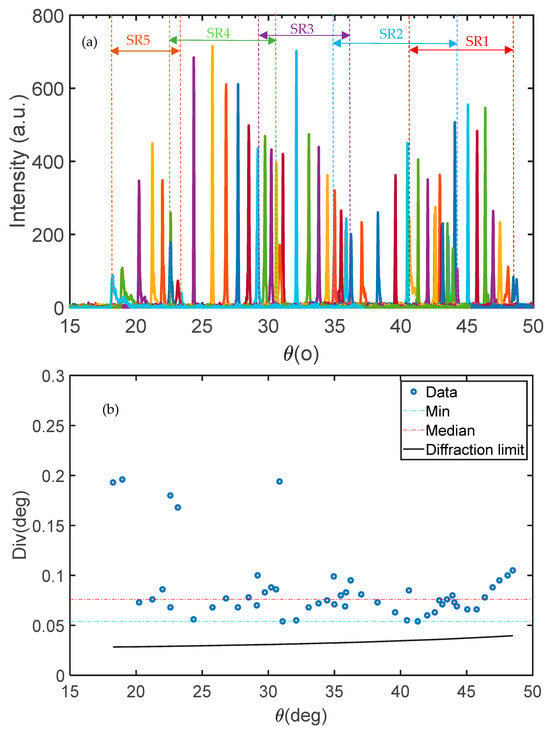

The far-field beam-steering behavior of the 5 × 1 array was subsequently evaluated, as illustrated in Figure 8a. Beam steering is achieved electronically by varying the injection current applied to the laser section while maintaining a constant bias current of 250 mA on the 2 mm amplifier section. For the SR1 device, the diffraction angle initially appears at 48.49° from the surface normal (defined as 0°) when the laser bias current is 80 mA. Although this current exceeds the lasing threshold, the first grating mode is not amplified due to blue-shifting of the amplifier gain under bias conditions. As the laser current increases, the emission angle progressively shifts toward the surface normal, reaching 40.63° at an injection current of 200 mA. For the SR2 device, the output beam emerges at a deflection angle of 44.26° at a laser current of 60 mA and shifts toward 34.95° at 250 mA. Device SR3 exhibits beam steering from 36.23° to 29.13° over a current range of 50 mA to 240 mA. Similarly, SR4 demonstrates a steering range from 30.85° to 22.6° as the laser current is increased from 50 mA to 220 mA. Finally, SR5 achieves beam steering from 23.4° to 18.24° over a current range of 60 mA to 220 mA. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the monolithically integrated VCSEL beam scanner achieves a total electronic beam-steering range of 30.25°, which represents the widest angular coverage reported to date for a monolithic VCSEL-based beam-steering system without the use of external optical components [29,32,33].

Figure 8.

(a) Measured FFP of beam scanner devices in array form (SR1 to SR5). Beam steering is controlled by current tuning of the seed lasers. (b) Beam divergence fluctuations plotted for each deflection angle.

Figure 8b summarizes the full width at half maximum (FWHM) beam divergence as a function of deflection angle (θ) for the 2 mm amplifier devices. The measured divergence values predominantly fluctuate around 0.076°, with the minimum divergence recorded at approximately 0.054°. For comparison, the theoretical diffraction-limited divergence for the 2 mm amplifier (~0.033°) is also shown in Figure 8b.

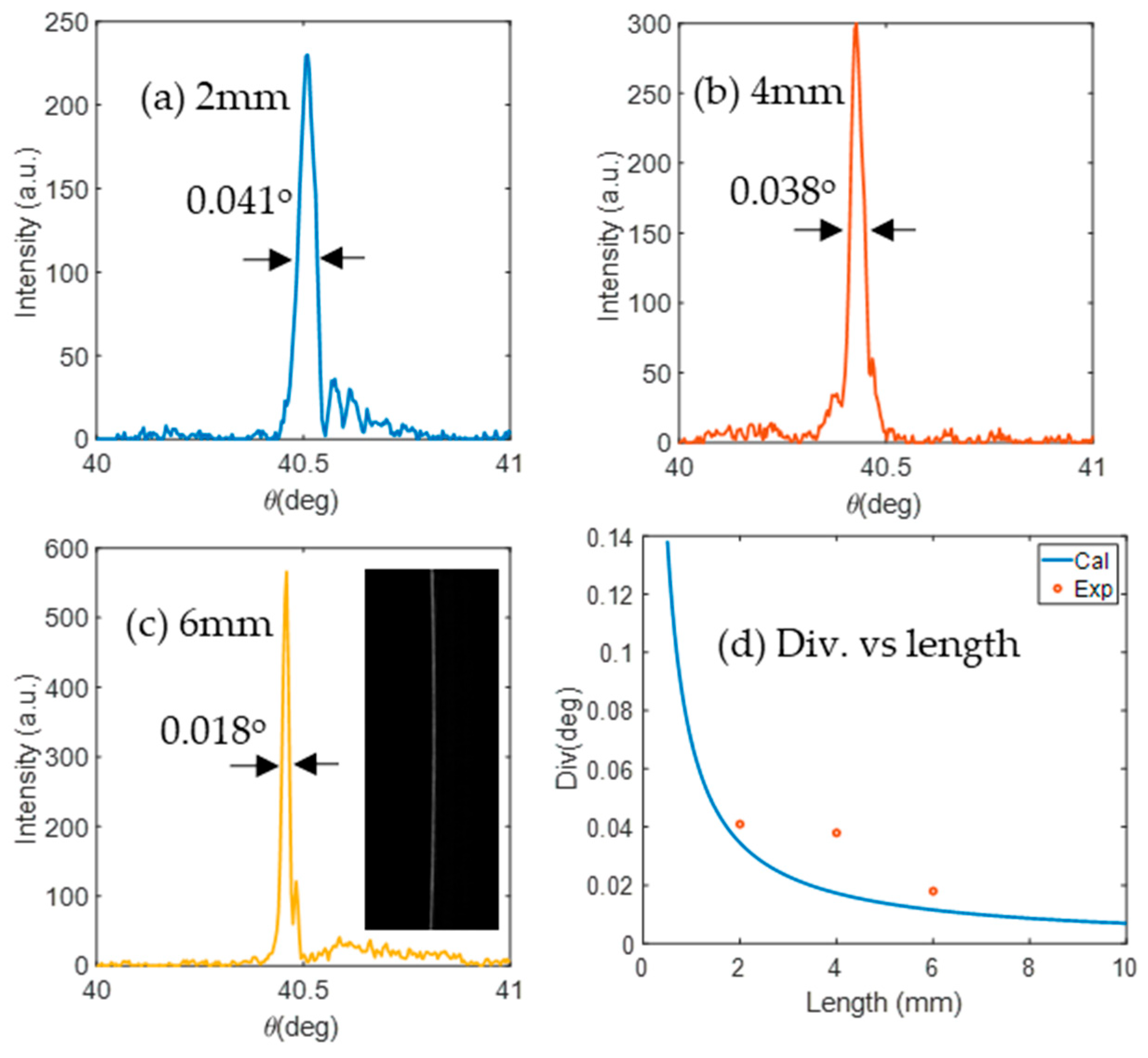

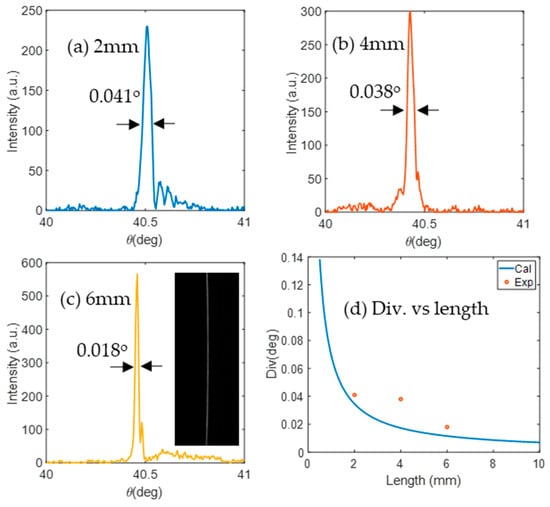

To further refine the divergence analysis, high-resolution beam profile measurements were conducted at a deflection angle of 40.49°, where the smallest divergence was initially observed. The far-field characteristics were characterized using a high-resolution measurement system, revealing a FWHM divergence of 0.041°, as depicted in Figure 9a for 2 mm amplifier. This result represents a significant advancement in the beam quality of VCSEL-based scanners, closely approaching the theoretical diffraction limit [25]. To investigate the impact of amplifier length on beam divergence, identical measurements were performed for devices incorporating amplifier lengths of 4 mm and 6 mm. As expected, the FFP deflection angle remained unchanged since it is governed by the current-induced wavelength tuning range of the seed laser. In contrast, the beam divergence exhibited a pronounced reduction with increasing amplifier length.

Figure 9.

(a–c) Beam profiles of devices with amplifier lengths of 2 mm, 4 mm, and 6 mm, respectively, measured using high-resolution camera. (d) Experimental beam divergence compared to the calculated divergence at the diffraction limit.

Figure 9b,c present the minimum beam divergence values measured for the 4 mm and 6 mm amplifier devices, respectively. The 4 mm amplifier exhibits a minimum divergence of 0.038°, while the 6 mm amplifier achieves an exceptionally low divergence of 0.018°. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the narrowest beam divergence ever reported for a VCSEL-based beam scanner and marks a significant improvement over our previously reported value of 0.024° for a 6 mm slow-light VCSEL amplifier operating at 850 nm [27]. The beam quality factor (M2) for the 6 mm amplifier device was calculated to be 1.57, indicating near-diffraction-limited performance. For reference, the theoretical diffraction-limited divergence at this wavelength and amplifier length is approximately 0.011°. Figure 9d compares the experimentally measured divergence values with the calculated diffraction limit as in [27]:

Here, is the measured beam divergence, and theoretical diffraction limit depends on the the amplifier length L and FFP deflection angle at wavelength and is approximately given as .

For the 2 mm amplifier device, the measured beam divergence is approximately 1.19 times the diffraction limit, while the beam divergence for 6 mm amplifier is 1.57 times, indicating improved current uniformity compared to devices with short amplifier lengths [27,28]. The residual divergence broadening is primarily attributed to non-uniform current injection and thermally induced refractive index variations resulting from high current densities [27,28]. Further reductions in beam divergence are anticipated through improved thermal management strategies and the implementation of multiple wire bonds to achieve more homogeneous current distribution across the amplifier section.

With a 30.25° range and minimum beam divergence, the angular resolution can be ~730 points for the 2 mm and ~1680 points for the 6 mm amplifier, without external optics. These results highlight the potential of the monolithic VCSEL–amplifier platform for compact, high-resolution, electronically steerable beam scanning.

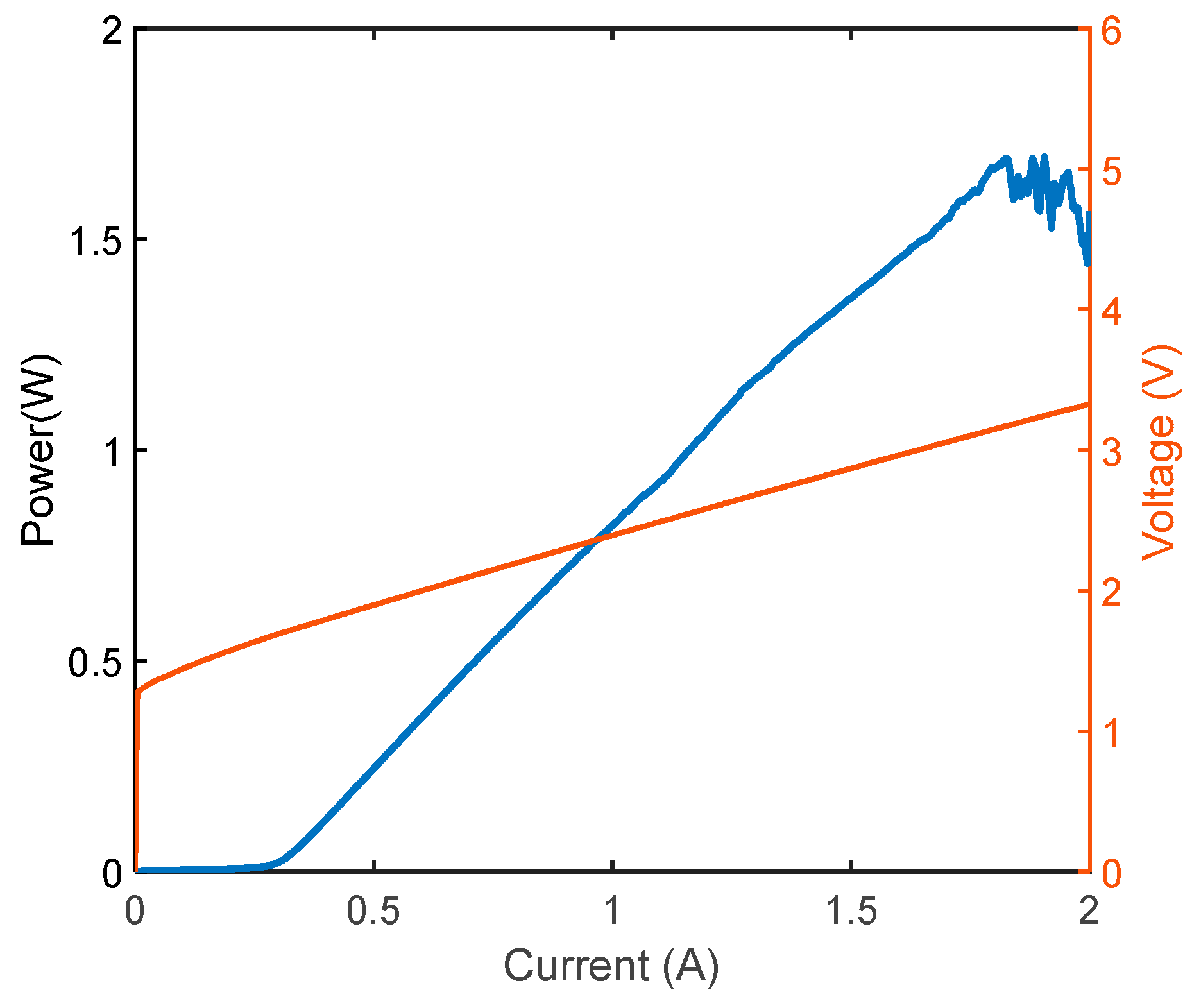

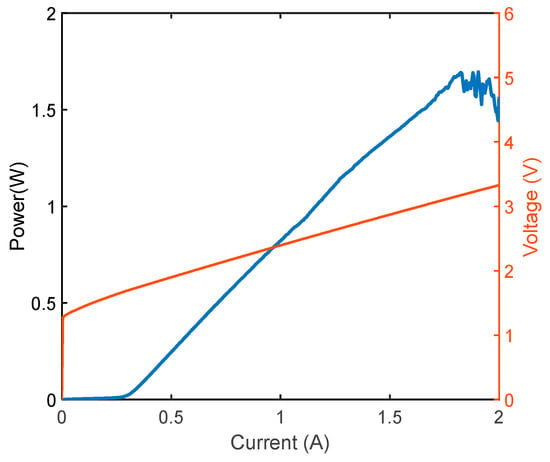

In addition to ultra-low beam divergence, high optical output power is critical for LiDAR, especially in long-range applications. Figure 10 shows the L–I–V characteristics of the 6 mm amplifier, measured in continuous-wave operation at room temperature without external cooling. The 0.3 mm seed laser was biased at 160 mA, while the amplifier current increased up to 2 A. The device exhibits a threshold current of ~300 mA and a high slope efficiency of 1.2 W/A, attributed to unidirectional slow-light propagation in the grating-free amplifier. A maximum output power of 1.69 W was achieved at an injection current of 1.82 A, beyond which power roll-off is observed, likely arising from thermal effects and the onset of in-plane optical modes. As shown in the L–I–V curves of Figure 10, the wall-plug efficiency of the devices remains around 30%, even for extended 6 mm devices.

Figure 10.

LI-curve of amplifier with a 6 mm length, the laser side is biased at 160 mA.

The wafer design has not yet been optimized for effective suppression of in-plane modes [36,37]. Consequently, further increases in output power are expected through improved lateral-mode suppression and optimized device design. Pulsed operation is anticipated to enable higher peak power while alleviating thermal limitations [36] (see Supplementary Materials).

4. Discussion

The demonstrated VCSEL-based beam scanner highlights the advantages of combining wavelength-tunable surface-grating seed lasers with extended-length slow-light-mode optical amplifiers in a monolithically integrated platform. Compared with conventional VCSEL beam-steering approaches relying on mechanical scanning or limited-wavelength tuning, the proposed architecture offers a markedly larger steering range together with superior angular resolution and output power. In particular, the use of surface-grating-coupled slow-light modes enables strong angular dispersion without sacrificing beam quality, as evidenced by the low divergence and near-diffraction-limited M2 values achieved at watt-class power levels.

The large number of resolvable angular points demonstrates the scalability of this approach toward high-resolution beam steering, which is critical for emerging solid-state LiDAR and free-space sensing applications. Moreover, the ability to achieve continuous-wave operation at high output power without active thermal management underscores the intrinsic thermal robustness of the slow-light amplifier design. Nevertheless, several challenges remain. Further improvement in current uniformity across the amplifier section will be essential to suppress residual in-plane modes and to maintain beam quality at higher power levels. In addition, thermal effects may become more pronounced as device length and output power are scaled further, necessitating optimized heat-spreading structures. Overall, this work clarifies both the strengths and remaining limitations of slow-light-assisted VCSEL beam scanners and provides clear guidelines for future optimization toward wider fields of view and higher power scalability.

5. Conclusions

We have demonstrated a monolithically integrated VCSEL-based beam scanner array that combines wavelength-tunable surface-grating seed lasers with extended-length slow-light-mode optical amplifiers to enable high-performance electronic beam steering. The array achieves a total steering range of 30.25° while maintaining high beam quality, with a minimum beam divergence of 0.018° and M2 = 1.57 for the 6 mm amplifier devices. A CW output power exceeding 1.6 W is achieved without active thermal management. Future efforts may extend the FOV via additional seed wavelengths, while improved current uniformity, thermal management, and in-plane mode suppression will enhance beam quality and power scalability. This work demonstrates a compact, scalable VCSEL beam-scanning platform with superior steering range, resolution, and output power, well suited for next-generation LiDAR and high-performance photonic integration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/photonics13020172/s1, Figure S1. (a) Optical micrograph of the packaged 1-mm slow-light VCSEL beam scanner with six wire bonds. (b) L–I characteristics under pulsed operation at 10 ns and 50 ns, showing enhanced output power (>1.6 W) and reduced thermal saturation at 10 ns compared to saturation at 50 ns due to self-heating. (c) Temporal output waveform under 10-ns pulsed operation, confirming stable pulse generation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.H. and F.K.; validation: A.H. and X.G.; methodology: A.H. and X.G.; formal analysis: A.H., X.G. and F.K.; visualization: A.H.; writing—review and editing: A.H. and F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), grant number JPMJTR211A.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article as shown in the figures and associated descriptions.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are employees of the Institute of Science Tokyo. Xiaodong Gu is also the CEO of Ambition Photonics Inc., Tokyo, Japan. The authors declare that these affiliations did not influence the work reported in this paper and that no other financial or personal relationships exist that could have appeared to influence the work.

References

- Stähler, J.; Markgraf, C.; Pechinger, M.; Gao, D.W. High-Performance Perception: A camera-based approach for smart autonomous electric vehicles in smart cities. IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2023, 11, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jarroudi, M.; Kouadio, L.; Delfosse, P.; Bock, C.H.; Mahlein, A.K.; Fettweis, X.; Mercatoris, B.; Adams, F.; Lenné, J.M.; Hamdioui, S. Leveraging edge artificial intelligence for sustainable agriculture. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, E.; Lambert, J.; Carballo, A.; Takeda, K. A Survey of Autonomous Driving: Common Practices and Emerging Technologies. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 58443–58469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roriz, R.; Cabral, J.; Gomes, T. Automotive LiDAR Technology: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 6282–6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ho, C.P.; Xue, J.; Lim, L.W.; Chen, G.; Fu, Y.H.; Lee, L.Y. A progress review on solid-state LiDAR and nanophotonics-based LiDAR sensors. Laser Photonics Rev. 2022, 16, 2100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhu, F.; Lu, G.; Cai, Y.; Yin, L.; Kong, F.; Lin, J.; Chen, N.; Zhang, F. Safety-assured high-speed navigation for MAVs. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eado6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzhüter, H.; Bödewadt, J.; Bayesteh, S.; Aschinger, A.; Blume, H. Technical concepts of automotive LiDAR sensors: A review. Opt. Eng. 2023, 62, 031213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, P.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Niu, S.; Rao, R.Z.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; et al. Evolution of laser technology for automotive LiDAR, an industrial viewpoint. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, G.; Xun, M.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wu, D. Harnessing the capabilities of VCSELs: Unlocking the potential for advanced integrated photonic devices and systems. Light. Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, F. High-power VCSEL beam scanners for 3D sensing. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Europe & European Quantum Electronics Conference (CLEO/Europe-EQEC), Munich, Germany, 21–25 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Liang, D. Antireflective vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser for LiDAR. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimberg, D.; Koyama, F.; Iga, K. Highly-efficient VCSEL breaking the limit. Light. Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, F. Recent Advances of VCSEL Photonics. J. Light. Technol. 2006, 24, 4502–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalzik, R. VCSELs Fundamentals, Technology and Applications of Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Lasers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Quack, N.; Chou, J.B.; Wu, M.C. Self-aligned VCSEL-microlens scanner with large scan range. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 25th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Paris, France, 29 January–2 February 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 656–659. [Google Scholar]

- Bardinal, V.; Camps, T.; Reig, B.; Abada, S.; Daran, E.; Doucet, J.-B. Advances in Polymer-Based Optical MEMS Fabrication for VCSEL Beam Shaping. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2015, 21, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundeberg, L.; Kapon, E. Mode switching and beam steering in photonic crystal heterostructures implemented with vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 241115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson MTSiriani, D.F.; Peun Tan, M.; Choquette, K.D. Beam steering via resonance detuning in coherently coupled vertical cavity laser arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 201115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Xu, C.; Xie, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Deng, J.; Sun, J.; Chen, H. Ultra-compact electrically controlled beam steering chip based on coherently coupled VCSEL array directly integrated with optical phased array. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 13910–13922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.Y.; Ni, P.N.; Wang, Q.H.; Kan, Q.; Briere, G.; Chen, P.P.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Delga, A.; Ren, H.R.; Chen, H.D.; et al. Metasurface-integrated vertical cavity surface-emitting lasers for programmable directional lasing emissions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; Ni, P.N.; Wu, B.; Pei, X.Z.; Wang, Q.H.; Chen, P.P.; Xu, C.; Kan, Q.; Chu, W.G.; Xie, Y.Y. Metasurface Enabled On-Chip Generation and Manipulation of Vector Beams from Vertical Cavity Surface-Emitting Lasers. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2204286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitrit, N. Surface-emitting lasers meet metasurfaces. Light. Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, Y.; Koyama, F. Control of Group Delay and Chromatic Dispersion in Tunable Hollow Waveguide with Highly Reflective Mirrors. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 43, 5828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Kusunoki, Y.; Maeda, J.; Akiyama, D.; Kodama, N.; Abe, H.; Tetsuya, R.; Baba, T. Wide beam steering by slow-light waveguide gratings and a prism lens. Optica 2020, 7, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Shimada, T.; Koyama, F. Giant and high-resolution beam steering using slow-light waveguide amplifier. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 22675–22683. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Shimada, T.; Matsutani, A.; Koyama, F. Miniature Nonmechanical Beam Deflector Based on Bragg Reflector Waveguide With a Number of Resolution Points Larger Than 1000. IEEE Photonics J. 2012, 4, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Z.; Hayakawa, J.; Shimura, K.; Kondo, K.; Gu, X.; Matsutani, A.; Murakami, A.; Koyama, F. High Power and High Beam Quality VCSEL Amplifier. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Semiconductor Laser Conference (ISLC), Santa Fe, NM, USA, 16–19 September 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, J.; Murakami, A.; Tominaga, D.; Suzuki, Y.; Ho, Z.; Gu, X.; Koyama, F. Watt-class high-power and high-beam-quality VCSEL amplifiers. In Proceedings of the SPIE 10938, Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Lasers XXIII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; p. 1093809. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Gu, X.; Hassan, A.; Li, R.; Nakahama, M.; Shinada, S.; Koyama, F. Ultra-compact VCSEL scanner for high power solid-state beam steering. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 8742–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.-Y.; Tsao, K.; Cheng, H.-T.; Feng, M.; Wu, C.-H. Investigation of the current influence on near-field and far-field beam patterns for an oxide-confined vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 30748–30759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukin, V.A.; Ledentsov, N.N.; Kalosha, V.P.; Ledentsov, N., Jr.; Agustin, M.; Kropp, J.R.; Maximov, M.V.; Zubov, F.I.; Shernyakov, Y.M.; Payusov, A.S.; et al. Thermally stable surface-emitting tilted wave laser. In Proceedings of the SPIE 10552, Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Lasers XXII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 1055207. [Google Scholar]

- Kanja, S.; Hu, S.; Gu, X.; Koyama, F. Expanding Field of View of Solid-state VCSEL Beam Scanner with Multi-wavelength Seed VCSELs. In Proceedings of the 2022 28th International Semiconductor Laser Conference (ISLC), Matsue, Japan, 16–19 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Gu, X.; Shinada, S.; Koyama, F. Beam-curvature compensated Solid-state Beam Scanner Integrated with Multi-grating Pitch Tunable Slow-light VCSELs for Enhanced Field of View. In Proceedings of the ECOC 2022, Basel, Switzerland, 18–22 September 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Iga, K. On the Use of Effective Refractive Index in DFB Laser Mode Separation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1983, 22, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aellen, M.; Norris, D.J. Understanding optical gain: Which confinement factor is correct? ACS Photonics 2022, 9, 3498–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Gu, X.; Nakahama, M.; Shinada, S.; Ahmed, M.; Koyama, F. High-power operations of single-mode surface grating long oxide aperture VCSELs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 191103. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.; Gu, X.; Koyama, F. Monolithically Integrated 4×1 Surface-Grating VCSEL Array Scanner for Compact Solid-state LiDAR Applications. In Proceedings of the 30th Microoptics Conference (MOC), Utsunomiya, Japan, 12–15 October 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kogelnik, H. Coupled wave theory for thick hologram gratings. Bell Sys. Tech. J. 1969, 48, 2909–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.