Abstract

With the rapid advancement of biology and life sciences, there is an increasing demand for observing sub-cellular structures and molecular interactions at submicroscopic or even single-molecule levels, providing critical insights into life activities and disease diagnostics. Raman spectroscopy, which relies on molecular vibrational energy transitions, enables non-label and non-invasive cellular visualization, holding significant potential for modern medical technology. The microscopy method based on the coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering effect, a novel visualization modality with superior signal intensity, chemical specificity, and label-free capability, demonstrates great promise in biomedical applications. Recently, dual-comb technology, consisting of two frequency combs with slightly different repetition rates, as a powerful light source has been successfully applied in CARS applications with the excellent performance characteristics of rapid acquisition, high resolution, and high signal-to-noise ratio. The dual-comb technique allows to clearly resolve sharp molecular lines and could suppress the non-resonant background in CARS. Through recent research progress, this work reviews the generation of dual-comb lasers based on a single cavity, the development of dual-comb CARS systems, and their biomedical applications. This review could provide further insights into high-resolution dual-comb CARS and potential ways to design such technology for potential biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

The development of microscopic imaging technology continuously drives advancements in biomedical imaging, while the evolving demands of biomedical imaging further necessitate continuous progress in microscopic imaging techniques [1,2,3]. Conventional microscopic imaging modalities include optical microscopy bright-field observation, phase contrast microscopy, and fluorescence microscopy. Bright-field and phase-contrast microscopy enable non-destructive cellular observation but suffer from poor contrast and molecular specificity. Fluorescence microscopy [4,5,6] relies on exogenous chemically specific substances that induce phototoxicity, such as light damage, photobleaching, and disrupted cellular metabolism, rendering it unsuitable for long-term live-cell imaging. Raman spectroscopy [7,8,9,10], leveraging molecular vibrational transitions, offers label-free and non-invasive imaging, providing a great contribution to modern medical development. However, the primary limitations of traditional Raman microscopy, like insufficient signal strength and fluorescence background and crosstalk, limit its clinical utility.

To address these limitations, advanced Raman techniques have emerged, including surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) for dramatic signal amplification [11], coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS) for high-speed, label-free imaging [12], stimulated Raman spectroscopy (SRS) for high-sensitivity chemical mapping [13], resonance Raman spectroscopy (RRS) for selective molecular detection [14], and spatially offset Raman spectroscopy (SORS) for subsurface analysis [15]. These techniques have great potential in specific biomedical applications due to their unique advantages. Compared with other techniques, CARS offers exceptional detection capability, low noise, excellent spatial precision, high data acquisition rate, and non-invasive and non-destructive detection. Thus, CARS has great potential in clinical applications. Moreover, the femtosecond optical frequency comb provides an accurate basis for rapid scanning, which has been used in CARS imaging.

Optical frequency combs [16], consisting of equally spaced spectral lines and periodic pulse trains, were initially developed for precision frequency metrology but now find applications in astronomical spectrometer calibration [17,18] and precision spectroscopy [19]. Dual-comb spectroscopy [20,21,22,23,24], derived from this technology, converts optical frequencies to radio frequencies through the use of two optical frequency combs with a fixed repetition frequency detuning, thus attaining ultrahigh resolution, sensitivity, and sampling rates. This approach has been applied to gas absorption spectroscopy [25] and nonlinear spectral imaging [26,27]. The most efficient dual-comb generation method employs a single-cavity configuration, producing two mutually coherent mode-locked pulse trains while minimizing system complexity. Ideguchi et al. [28] validated the capability of dual combs in nonlinear spectroscopy and demonstrated its potential for CARS, enabling rapid hyper-spectral imaging and suppressing the incoherent background underlying the resonant signal.

CARS, first reported in [29,30], functions via a coherent four-wave mixing (FWM) mechanism to resonantly enhance anti-Stokes scattering when the energy difference between the pump and Stokes beams coincides with a molecular vibration. CARS holds an architectural advantage in signal scale, dwarfing the output of spontaneous Raman scattering by multiple orders of magnitude [12], enabling faster spectral acquisition. Described by the χ(3) nonlinear susceptibility tensor, CARS exhibits high sensitivity and a blue-shifted signal that avoids fluorescence interference, making it ideal for label-free bioimaging [31,32,33,34,35].

This paper reviews dual-comb CARS for biomedical imaging. Section 2 introduces its fundamental principles, Section 3 discusses four single-cavity dual-comb generation methods, Section 4 summarizes dual-comb CARS microscopy systems, and Section 5 outlines biomedical applications, followed by conclusions and future perspectives.

2. Overview of the Fundamental Principles

2.1. Basic Principles of Optical Frequency Combs

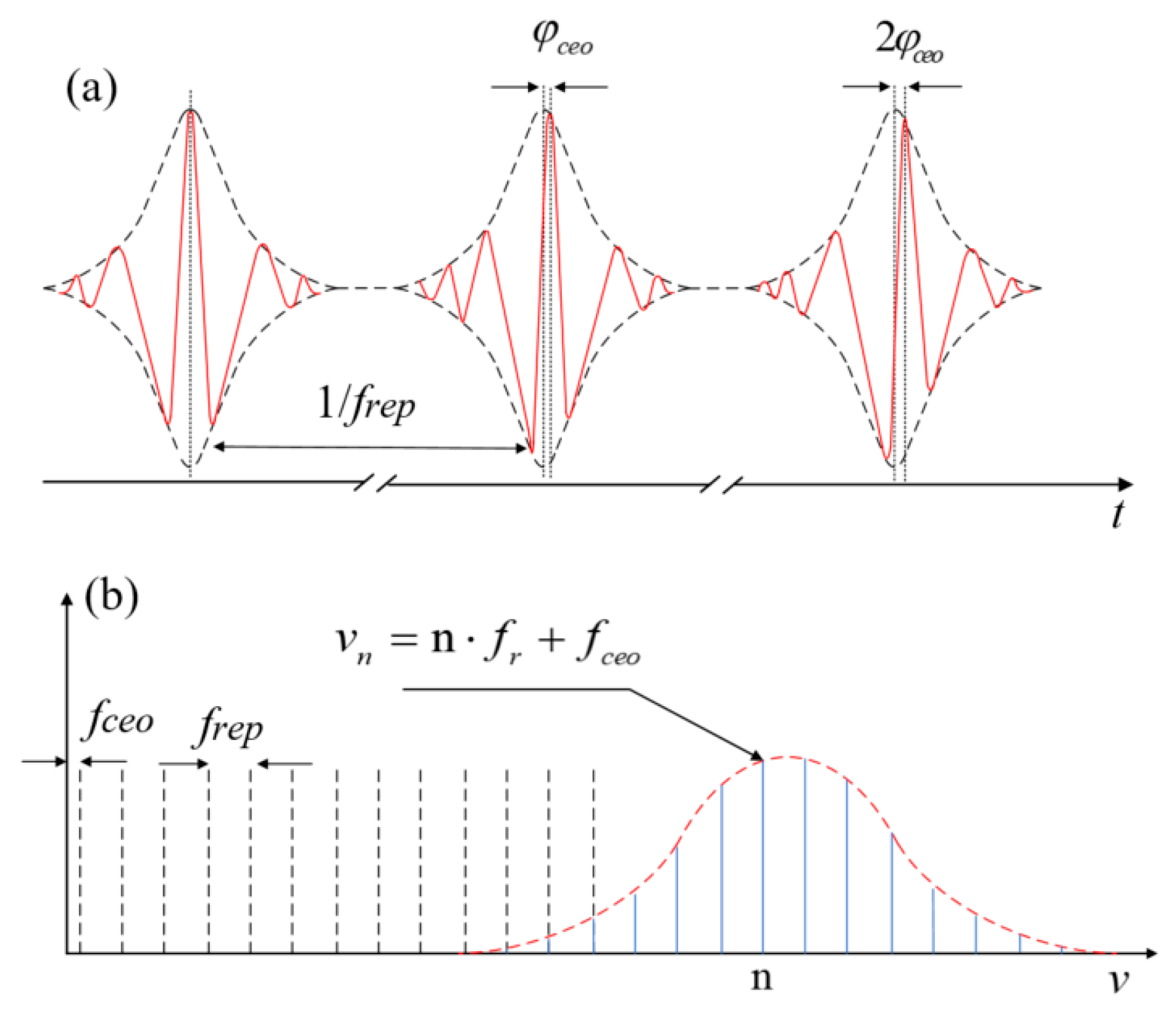

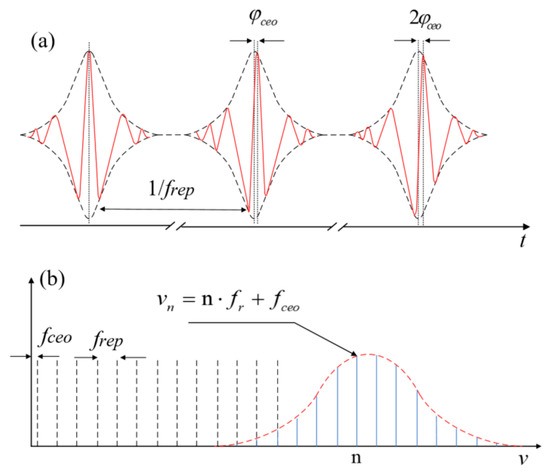

A mode-locked laser generates an optical frequency comb, which produces a novel ultrafast pulsed light source. In the time domain, it exhibits femtosecond-scale electromagnetic field oscillations, where the bandwidth of the spectrum of the optical frequency comb is governed by the pulse duration of the slowly varying field envelope via a Fourier transform. Considering the frequency spectrum, it is characterized by a series of spectral lines with uniform spacing as illustrated in Figure 1a,b [17]. The time–frequency distribution of these ultrashort pulses resembles the teeth of a comb, hence the term “optical frequency comb.” The spacing between adjacent comb lines equals the pulse repetition frequency (frep). Due to dispersion in the laser cavity, phase slippage is inevitable, causing the entire comb to shift relative to the integer harmonics of frep by an offset frequency fceo. Thus, the frequency of the m-th (order) comb mode is provided by the following:

fm = mfrep + fceo

Figure 1.

The concept of optical frequency comb. (a) Pulses in time domain. (b) Comb lines in frequency domain.

Here, frep represents the repetition rate and fceo denotes the carrier-envelope offset (CEO) rate.

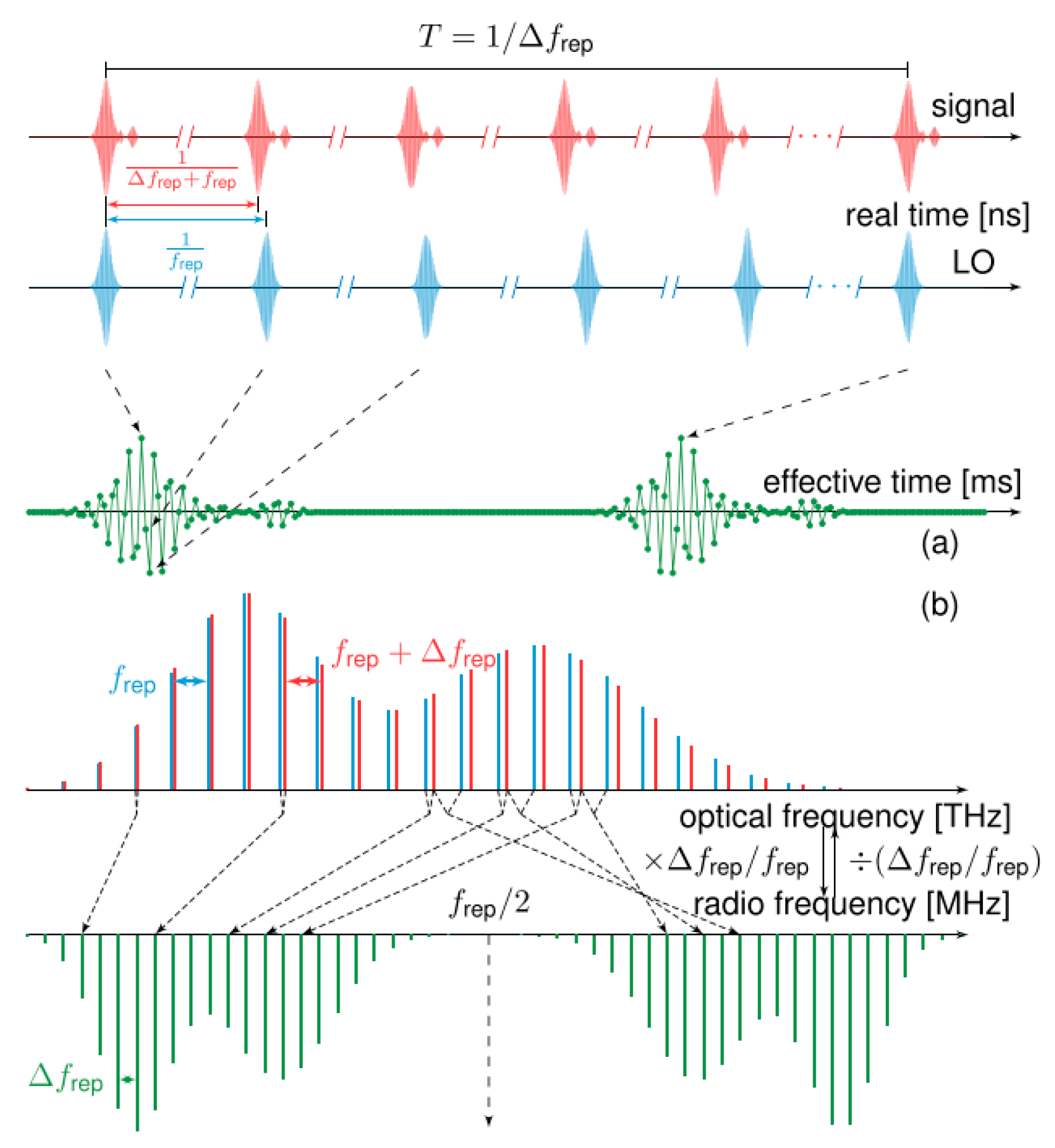

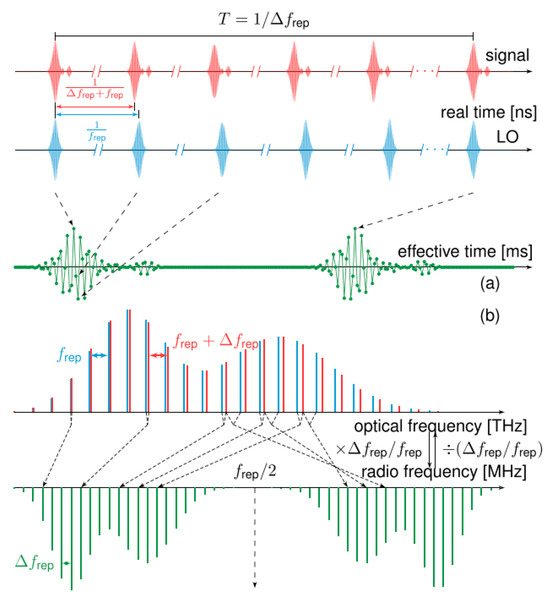

2.2. Basic Principles of Dual Optical Combs

Dual-comb spectroscopy (DCS) [20] has generated substantial heat in academic circles attributable to its uncommon advantages of simultaneously achieving excellent resolving power, exceptional responsivity, expansive spectral reach, and rapid measurement. The essence of DCS lies in utilizing a pair of optical frequency combs whose repetition rates differ slightly to perform asynchronous optical sampling, where the acquired interferogram is subsequently processed to reconstruct the spectrum of the sample. Owing to the difference in repetition rates between the two pulse trains, the relative timing between successive pulse pairs evolves linearly with a period of 1/Δfrep. Asynchronous optical sampling is achieved through the interaction of two pulse trains with a slight difference in their repetition rates. In the frequency domain, the beating between the two optical frequencies results in a down-conversion of the signal, generating a frequency comb with teeth spaced by the repetition rate difference, as illustrated in Figure 2a. In the time domain, this process enables optical temporal sampling, yielding a periodic interferogram shown in Figure 2b. Remarkably, the dual-comb approach reduces acquisition time by more than 1000 times compared to conventional methods. Furthermore, the spectral resolution and span are fundamentally determined by the measurement time of the femtosecond laser light source and its spectral band width, respectively. Due to dual-comb technology involving two sets of pulses sharing the same physical propagation path, differential-mode noise can cancel each other, which can help eliminate non-resonant background noise in subsequent coherent Raman signals.

Figure 2.

The asynchronous optical sampling between two pulse trains. (a) Dual combs are mixed to generate (b) the RF comb. Reproduced with permission [17]. Copyright 2020 the authors, published by IOP Publishing Ltd.

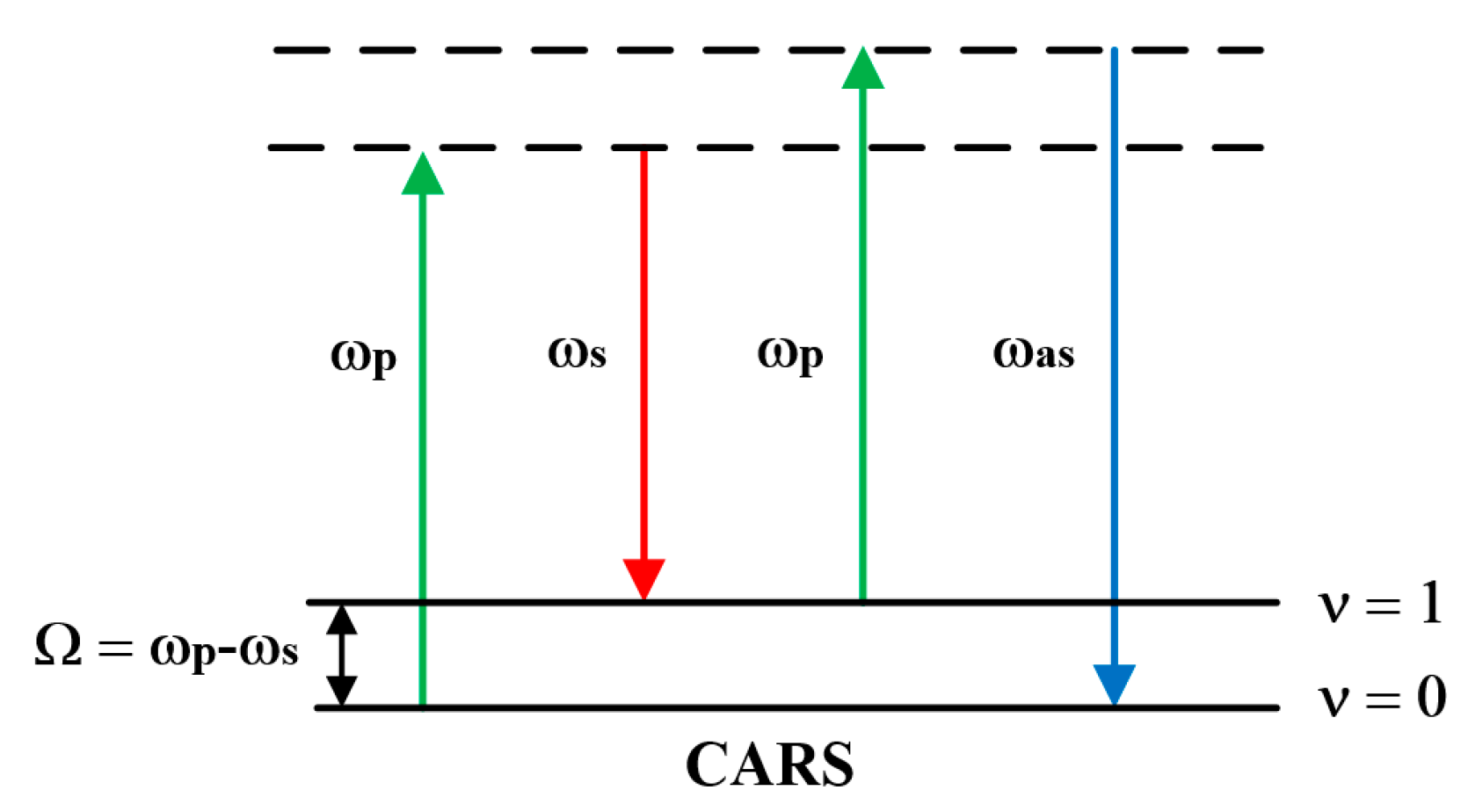

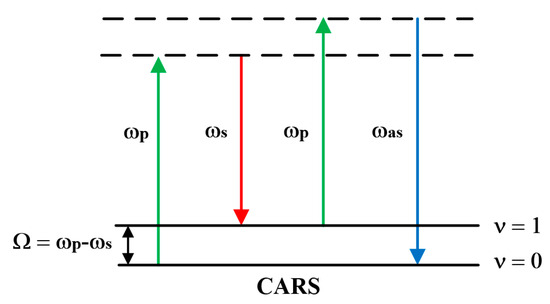

2.3. Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy

CARS was first observed in 1965, with related reports coming from a research team at Ford Motor Company [29]. Over the following decades, various microscopic techniques based on CARS emerged, leading to increasingly widespread applications in biomedical fields. The core of the CARS process lies in the interaction between the pump light ωp and the Stokes light ωs by a wave-mixing interaction with the sample. When two beams of light achieve spatial collinear focusing at the sample, and the beat frequency ωp-ωs resonates with the molecular vibrational frequency, the excitation field drives the resonator in a coherent manner. This generates a strong anti-Stokes signal at an absolute frequency ωas = 2ωp-ωs, as illustrated in the energy level diagram shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Energy level change in CARS.

Under excitation by phase-locked ωp-ωs fields, the pump field and the Stokes field jointly act on all resonators to achieve coherent driving. At the anti-Stokes frequency, microscopic induced dipoles undergo coherent superposition, resulting in collective third-order polarization p(3). The anti-Stokes field is generated through nonlinear interaction between the pump fields and Stokes fields, provided by p(3)(ωas)∝χ(3)E2pE∗s. Among them, the complex ratio constant χ(3) characterizes the third-order nonlinear susceptibility. Under the premise that the pump light and the Stokes light satisfy the plane wave approximation, the intensity expression of the anti-Stokes signal can be derived by analytically solving the wave equation [29,30,31]:

where z representing the sample thickness, the wave vector is defined as ki = 2π/λi, and as − (2kp − ks) represents the wavevector mismatch accounting for phase velocity differences among the three frequencies. The phase matching condition corresponds to kz ≈ 0, at which the sinc function reaches its peak and the signal is at its strongest.

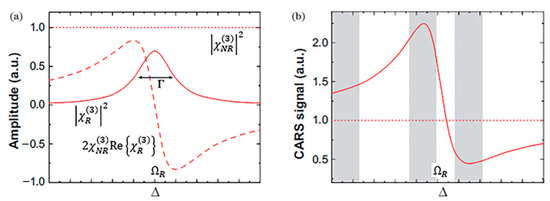

Even if ωp-ωs does not resonate with the vibration, the pump and Stokes fields can still drive macroscopic polarization response in the anti-Stokes spectral region through the non-resonant electron nonlinearity of the material. When both the ωp and ωs are significantly detuned from the electronic resonance energy levels of the material, they still contribute to the observable background of the coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) signal through non-resonant nonlinear processes. The anti-Stokes signal becomes enhanced when the frequency difference between ωp and ωs precisely matches a certain intrinsic vibration frequency, consisting of both resonant () and non-resonant () components [30]:

In the formula, the detuning Δ is provided by Δ = ωp − ωs − ΩR, reflecting the offset between the pump–Stokes beat frequency and the Raman center frequency ΩR; here, ΩR represents the center frequency of a uniformly broadened (linewidth Γ) Raman spectral line.

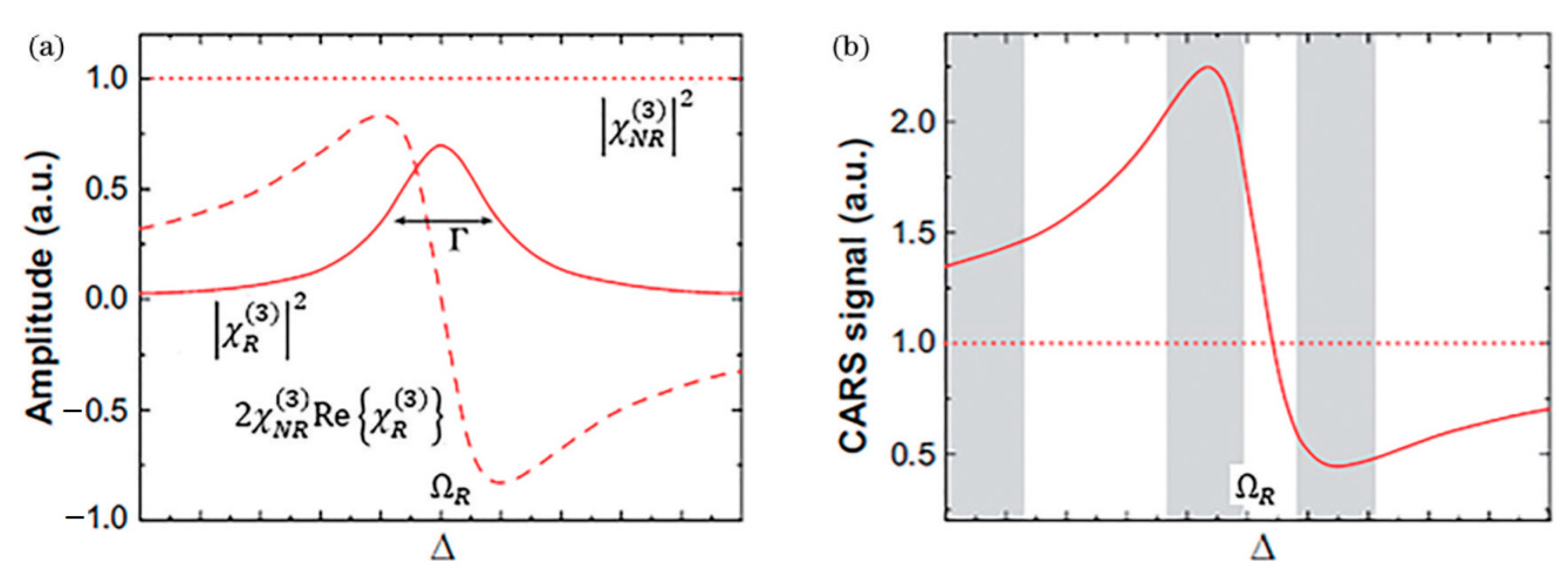

Starting from the proportional relationship between the CARS signal intensity and , the mathematical form of the anti-Stokes intensity can be derived [30]:

where the resonant component of χ(3) contributes a real part denoted as . The first part constitutes the non-resonant background (Raman-independent), the middle term represents the resonant signal, and the last part describes their interaction term. This coupling complicates CARS signals and causes spectral distortion compared to spontaneous Raman spectra, significantly impacting wavelength selection and result interpretation. The traditional scalar interpretation of Δk in CARS neglects the material anisotropy and polarization dependence implied by the tensorial nature of χ(3), while the wide wavevector spectrum can be provided by high-NA microscopy. Furthermore, the non-resonant background may lead to misinterpretation of weak signals, particularly in the fingerprint region, as clearly illustrated in Figure 4. This distortion, characterized by spectral asymmetry, peak shifts, and even lineshape inversions, is a key factor complicating the direct interpretation of CARS spectra compared to the symmetric, purely absorptive lineshapes of spontaneous Raman scattering. Dual-comb technology is essentially a Fourier transform spectroscopy technique with extremely high spectral resolution (up to the MHz level, determined by the linewidth of the comb teeth). This allows it to clearly resolve sharp rovibrational molecular lines and distinguish them from flat non-resonant background regions. It had been shown that the non-resonant background, which strongly lowers the sensitivity of CARS, could be suppressed by using dual-comb technology [28].

Figure 4.

The analysis of anti-stokes signal strength of (a) amplitude and (b) CARS signal. Reproduced with permission [30]. Copyright 1967 AIP Publishing.

3. Generation Methods of Single-Cavity Dual-Comb Sources

A typical traditional dual-comb scheme consists of two mode-locked lasers, which share the same reference laser to achieve frequency stabilization, requiring complex servo systems that limit practical applications [20,21,22,23,24]. Inspired by multiplexing techniques in fiber-optic communications, single-cavity dual-comb generation enables the production of two pulse trains with slightly different repetition rates within a single laser cavity through polarization, wavelength, or transmission channel multiplexing. Four principal multiplexing techniques are utilized: direction-based, wavelength-based, space-based, and polarization-based approaches. Each method is discussed in detail below. To our knowledge, there is currently no commercial single-cavity dual-comb source applied to CARS instrumentation. Different multiplexing schemes for generating single-cavity dual-comb lasers offer distinct advantages. For instance, the direction-multiplexing method utilizes clockwise and counterclockwise propagation to create two pulse sets, typically yielding a small repetition rate offset. The wavelength-multiplexing method produces two pulse trains that share nearly identical propagation paths, resulting in lower common-mode noise. The spatial-multiplexing method facilitates the generation of dual-color dual-comb output within a single cavity. The polarization-multiplexing method, on the other hand, generates two orthogonally polarized pulse trains, allowing straightforward adjustment of the repetition rate difference.

3.1. Direction Multiplexing

Direction multiplexing employs a laser cavity without optical isolators, allowing bidirectional lasing. The optical fields traveling in clockwise and counterclockwise directions experience different sequences of optical components, this will causes subtle changes in the repetition rate of the two counter-propagating pulse sequences, thereby forming a dual-comb source.

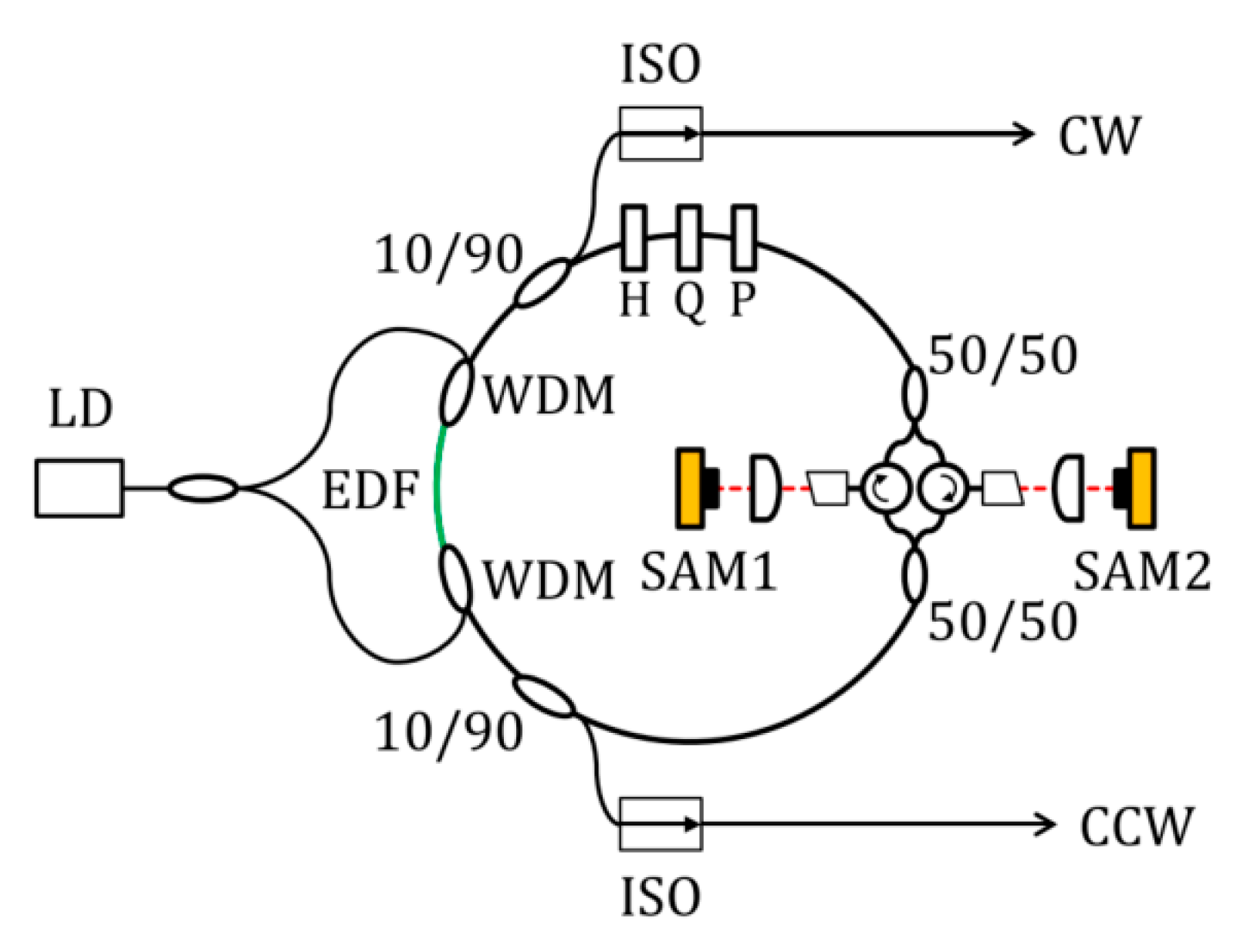

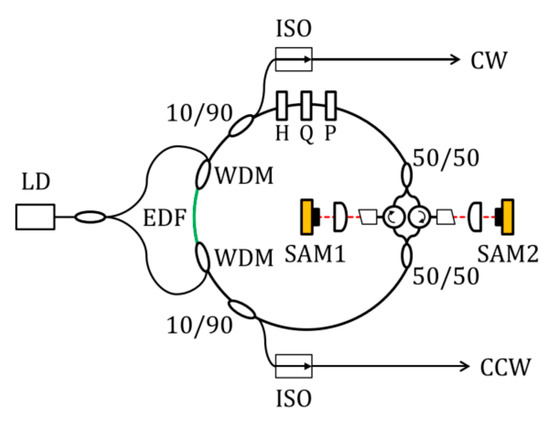

By inserting an intensity modulator into a helium–neon ring laser, Buholz et al. at Stanford University first achieved a directionally multiplexed mode-locked laser in 1967 [36], successfully demonstrating bidirectional active mode-locked operation. The performance of bidirectional mode-locked lasers has been constrained by intracavity dispersion, limiting achievable bandwidth and pulse energy. Recent efforts have focused on overcoming these limitations. Nakajima et al. [37] successfully fabricated a novel bidirectional erbium-doped mode-locked fiber laser (shown in Figure 5) in which Δfrep could be widely tuned by adjusting optical path differences in non-common components. Through dispersion management that achieved near-zero net dispersion, a spectral width exceeding 50 nm was realized, enabling a highly coherent ultra-broadband-frequency comb. The pioneering work presented by Li et al. [38] introduced an artificial saturable absorber (ASA) approach to enable bidirectional mode-locking in an all-normal-dispersion fiber laser configuration, achieving output pulse energy >1 nJ and breaking previous energy limitations. Chen et al. [20] achieved bidirectional pulse output with central wavelengths of 1556 nm and 1559 nm by designing a sub-cavity structure containing both CW and CCW paths.

Figure 5.

Bidirectionally multiplexed mode-locked fiber lasers. LD: laser diode; EDF: Er-doped fiber; WDM: wavelength division multiplexing coupler; H and Q: half- and quarter-wave plate; P: polarizer; SAM: saturable absorber mirrors. Reproduced with permission [37]. Copyright 2019 Optical Society of America.

3.2. Wavelength Multiplexing

The wavelength multiplexing scheme utilizes a single femtosecond laser cavity to simultaneously excite two pulse sequences with slight differences in central wavelength, thereby achieving the construction of a single-cavity dual-optical frequency comb. The difference in repetition frequencies between the two pulse sequences stems from the disparity in group velocity dispersion characteristics caused by the different wavelengths.

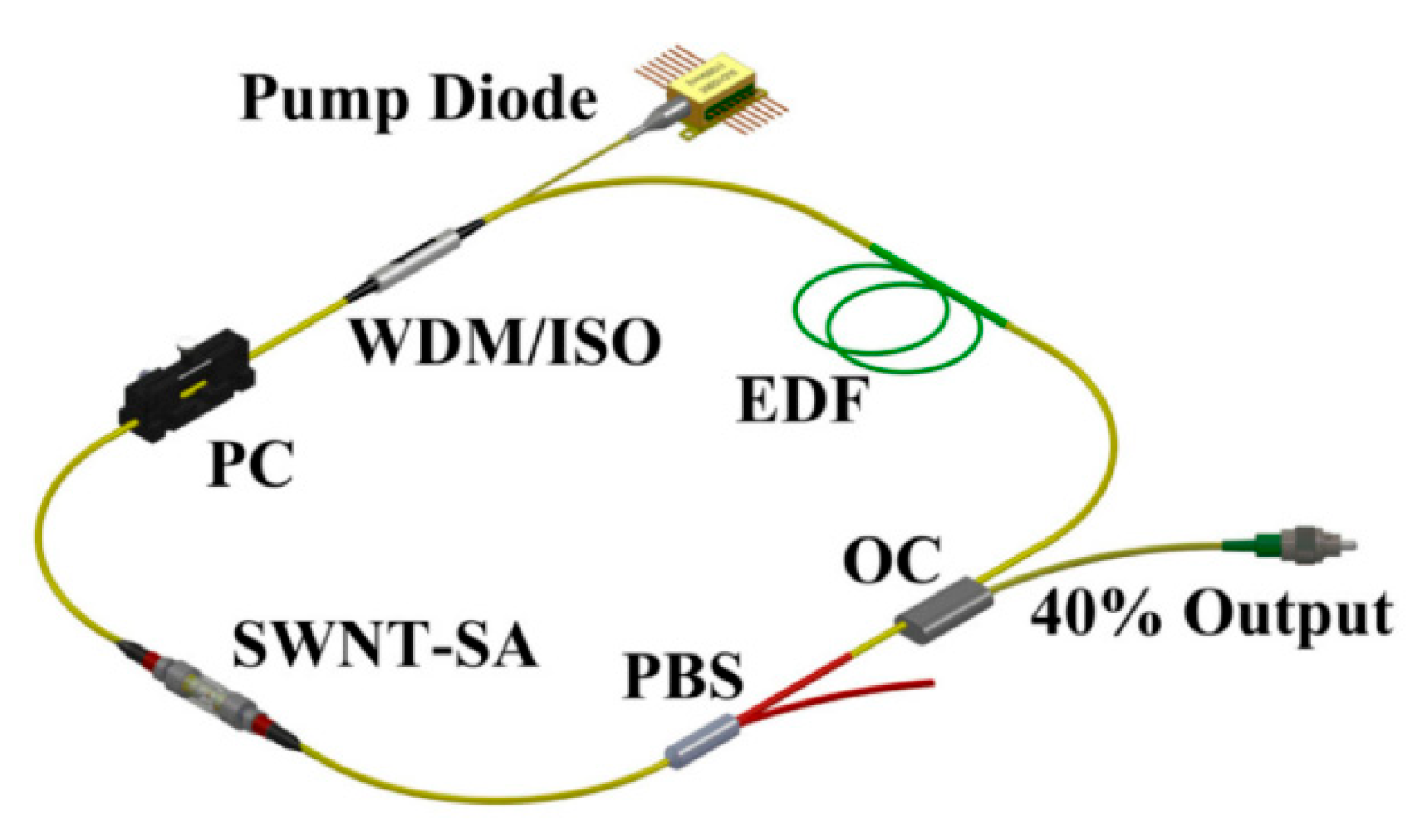

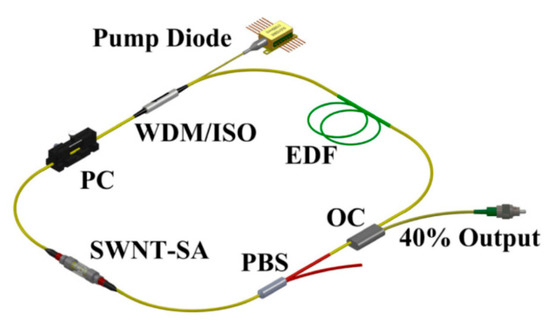

Inserting a periodic sinusoidal spectral filter into a mode-locked fiber-based laser allows dual- or multi-wavelength mode-locking through cavity parameter adjustment. The Lyot filter [39,40], a widely used sinusoidal spectral filter, has attracted significant attention due to its tunable filtering depth. The feasibility of a dual-comb spectroscopy approach employing a free-running dual-wavelength fiber ring laser was validated by Zhao et al. [41] (shown in Figure 6). By utilizing the intracavity integration technology of all-fiber polarization beam splitter (PBS) and a segment of polarization-maintaining (PM) fiber segments, the functional construction of a Lyot filter has been achieved in an erbium-doped mode-locked fiber laser; dual-wavelength mode-locking was achieved through spectral filtering and intracavity loss modulation. Besides this, the Sagnac filter represents another sinusoidal spectral filter suitable for wavelength multiplexing. Li and colleagues [42] introduced a scheme for a dual-wavelength mode-locked laser, featuring an all-polarization-maintaining-fiber architecture. By utilizing a nonlinear amplifying loop mirror (NALM) with an integrated nonreciprocal phase shifter, self-starting operation of the mode-locked laser was successfully enabled. Acting as a polarization-maintaining Sagnac loop filter, a specifically angled splice of a short PM fiber to the NALM facilitated switchable dual-wavelength mode-locking. This configuration allowed the laser to stably alternate its emission between the spectral bands centered at 1570/1581 nm and 1581/1594 nm. Additionally, researchers have utilized notch filters to achieve dual-wavelength mode-locking [43], with repetition rate differences tunable from 100 to 1000 Hz. Zhang et al. [23] demonstrated the single-cavity dual-comb generation around 1060 nm by introducing a Lyot filter into the laser cavity combined with SEASM mode-locking.

Figure 6.

Dual-wavelength MLFLs. WDM: wavelength division multiplexing coupler; ISO: isolator; EDF: erbium-doped fiber; OC: optical coupler; PBS: polarization beam splitter; PC: polarization controller; SWNT: single-wall carbon nanotube; SA: saturable absorber. Reproduced with permission [41]. Copyright 2016 Optical Society of America.

3.3. Spatial Multiplexing

Spatial multiplexing achieves dual-comb generation by adjusting the cavity lengths of two resonators to control their respective repetition rates and repetition rate differences. Alternatively, researchers have implemented non-common-path cavity configurations to generate dual-comb outputs, which also falls under spatial multiplexing.

Zhao et al. [44] successfully developed a dual-color soliton fiber laser using nonlinear multimodal interference technology. The two resonant cavities share a saturable absorber with a “SMS” structure, where the multimode length is freely adjustable while maintaining dual-color soliton operation under appropriate length modifications. Li et al. [45] demonstrated a dual-wavelength fiber laser with passive synchronization capability operating at the spectral lines of 1.03 and 1.53 μm using a shared-cavity architecture. This scheme utilizes a common branch of approximately 1.2 micrometers in length, combined with a saturable absorber based on single-walled carbon nanotubes, to provide unified mode-locking, thereby achieving synchronous output of dual-wavelength pulses. Yang et al. [46] constructed a dual-ring laser employing a shared gain fiber, and achieved mode-locking by incorporating both a semiconductor saturable absorber mirror and nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR) technique within the two resonators. This enabled the generation of a single-pulse output and a dual-wavelength asynchronous pulse output, with repetition rate differences of approximately 2.74 kHz and 2.6 MHz, respectively.

3.4. Polarization Multiplexing

Polarization multiplexing exploits the differential index of refraction between the two principal polarization axes of optical components to generate pulse repetition frequency difference for two perpendicularly polarized trains of pulses within the same cavity. When using non-polarization-maintaining fiber as the gain medium, weak birefringence induces refractive index variations between polarization states. Dual-comb operation occurs when nonlinear interactions between polarization states are insufficient to overcome group-velocity walk-off induced by the birefringence in the fiber. For polarization-maintaining fiber gain media, orthogonal polarization states experience differential group delays due to birefringence, naturally producing two pulse trains with distinct repetition rates.

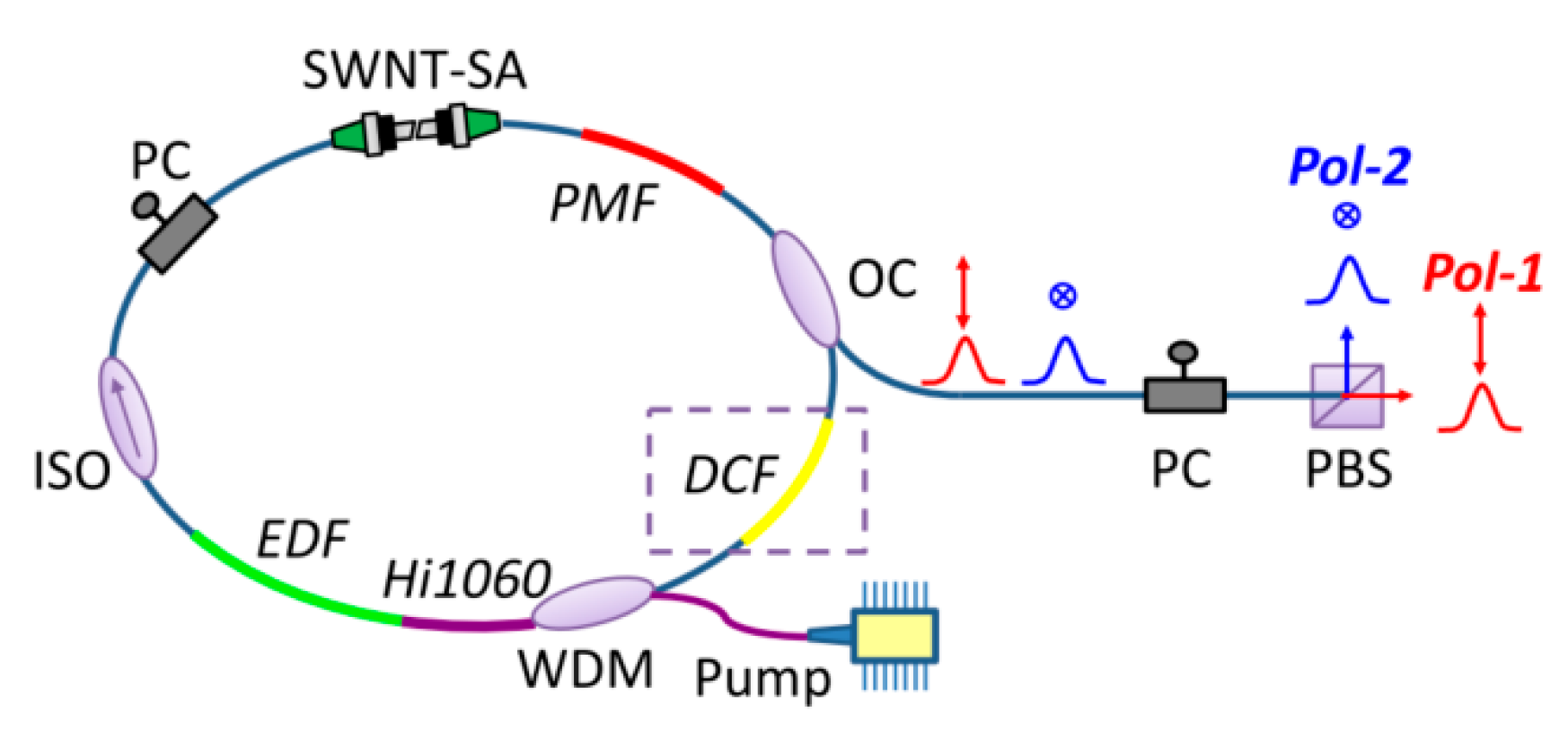

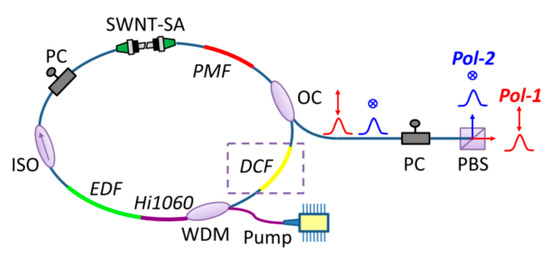

Zhao et al. [47] incorporated a 0.3-meter polarization-maintaining fiber segment into an erbium-doped mode-locked laser to produce two asynchronously operating orthogonally polarized pulse trains, as shown in Figure 7. Sterczewski et al. [48] demonstrated an exceptionally straightforward autonomous DCS setup. Using highly integrated fiber components to effectively shorten the cavity, they achieved dual-comb operation at 142 MHz exhibiting a 3.2 kHz repetition-rate offset. Tuning with poor repetition rate can be achieved by altering the polarization state within the cavity and adjusting the length of the polarization-maintaining fiber (PMF). The tuning range can easily cover the order of magnitude from hundreds of Hertz to thousands of Hertz.

Figure 7.

Polarization-multiplexed MLFLs. WDM: wavelength division multiplexing coupler; EDF: erbium-doped fiber; ISO: isolator; PC: polarization controller; SWNT: single-wall carbon nanotube; SA: saturable absorber; PMF: polarization maintaining fiber; OC: optical coupler; DCF: dispersion compensating fiber. Reproduced with permission [47]. Copyright 2018 Optical Society of America.

4. Advances in Dual-Comb Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Technology

Recently, CARS has gained increasing application in modern biomedical imaging as a non-invasive, non-destructive detection method offering high sensitivity, high spatial resolution, and rapid data acquisition rates. A number of technical approaches have been investigated, including, but not limited to, time-resolved CARS [49] and Fourier transform CARS [50,51].

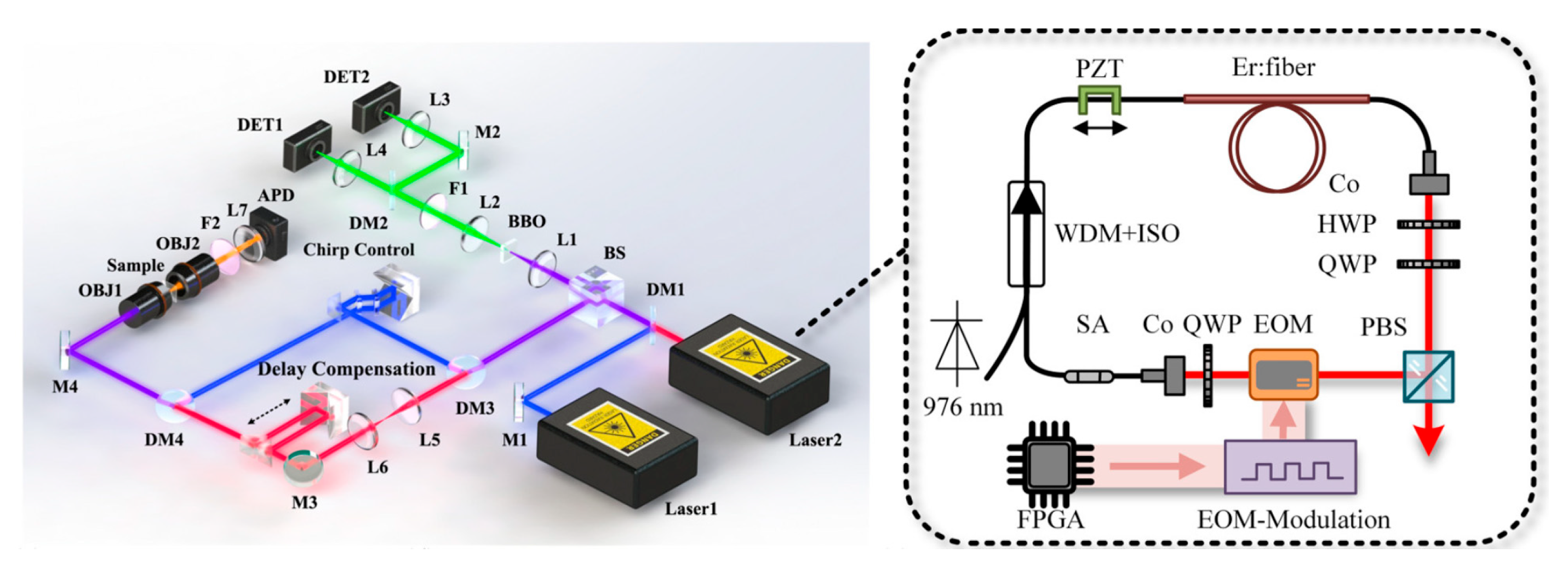

4.1. Proposal of Dual-Comb CARS

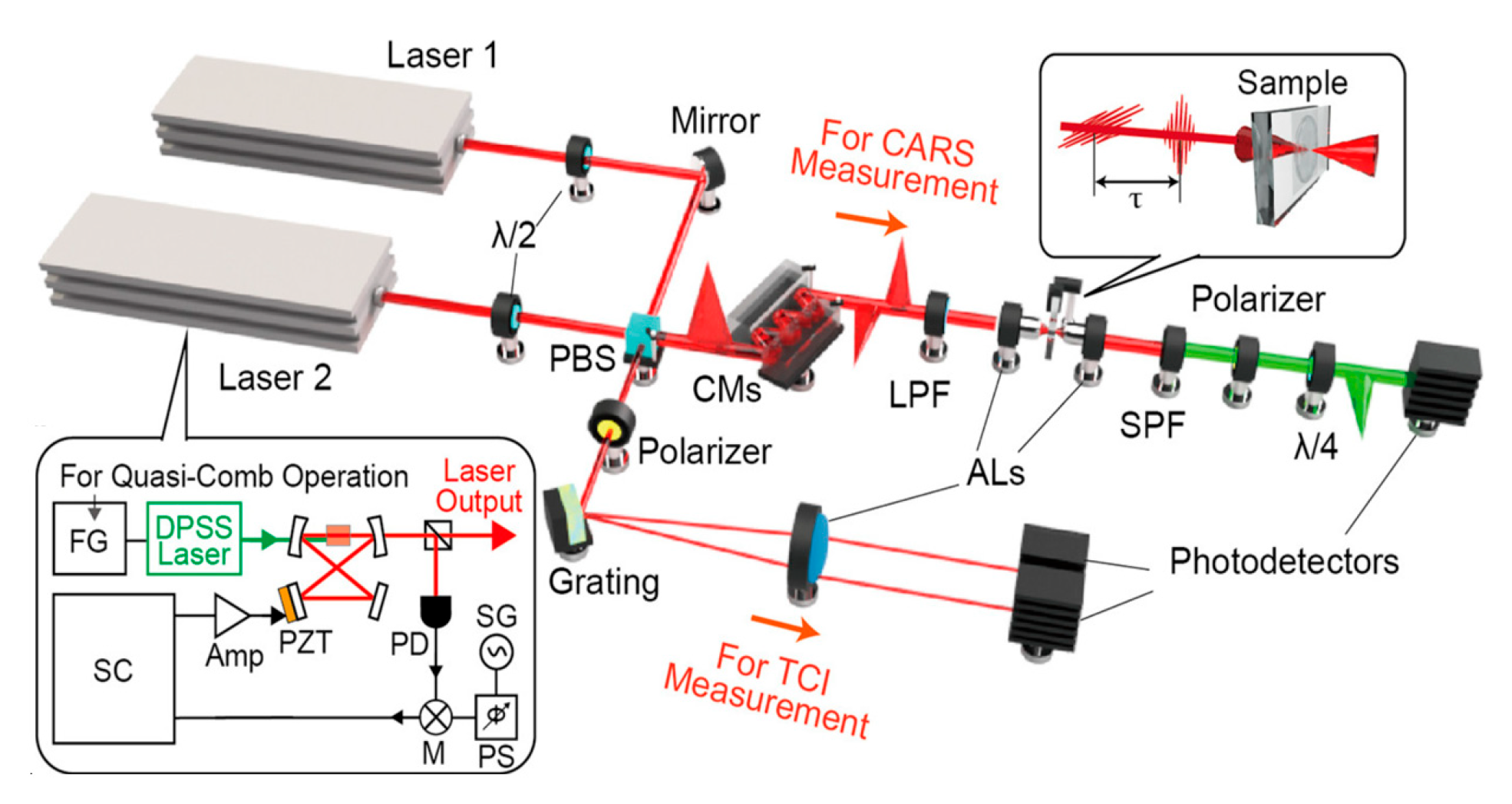

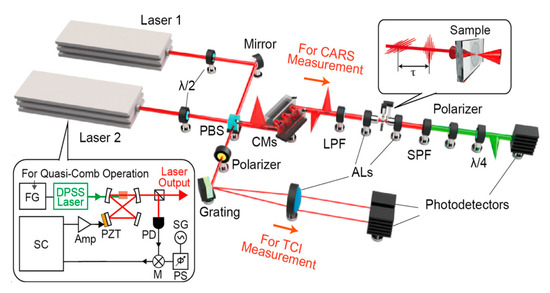

Early CARS spectroscopy relied on narrowband and tunable lasers [52]. Mechanical wavelength scanning was typically employed to probe multiple Raman resonances, resulting in complex, bulky systems sensitive to environmental conditions. Subsequently, supercontinuum (SC) laser sources enabled broadband multiplex CARS spectroscopy without tunable lasers [53]. According the reference [54], a Raman source with a broad spectral range of 0–4000 cm−1 was demonstrated by utilizing an erbium-doped fiber laser-pumped supercontinuum. However, integrating spectrometers or monochromators remained necessary to detect broadband Raman signals, increasing system complexity and cost. Additionally, a delay-spectral focusing dual-comb (DC) CARS scheme was proposed for rapid HW Raman detection based on two fiber combs [55], which compromises the robustness of the fiber laser system and is not conducive to maintaining its compact structure, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Experimental setup for dual-comb CARS. Reproduced with permission [56]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

To address these limitations, the dual-comb Fourier transform (FT) CARS spectroscopy technology has been developed as an alternative solution [28], with its experimental setup shown in Figure 8. This technical solution introduces two sets of optical frequency combs and sets them at slightly different repetition frequencies to excite and probe molecular samples via femtosecond pulse pairs when implementing a canonical two-photon Raman scheme. It enables rapid acquisition of high-resolution Raman spectra in the fingerprint region using a single-pixel photodetector. Moreover, the dual-comb approach allows static detection of time-resolved signals due to the inherent repetition rate difference. Luo et al. [56] conducted the initial proof-of-concept for dual-comb CARS, employing laser pulses on the order of 20 femtoseconds, achieving Raman shift coverage exceeding 3000 cm−1. Shchekin et al. [57] investigated the efficiency of CARS under frequency comb excitation, demonstrating higher excitation efficiency compared to continuous-wave excitation.

4.2. Fiber-Based Mode-Locked Laser Dual-Comb CARS Systems

Initial dual-comb CARS systems utilized Ti:sapphire lasers, achieving superior Raman spectra spanning from 200 to 1400 cm−1 with signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) up to 103 and resolution of 4 cm−1. However, the bulkiness and maintenance requirements of solid-state lasers limited practicality. Fiber lasers emerged as an alternative due to their compactness, excellent beam quality, and cost-effectiveness. Coluccelli et al. [58] have developed a dual-comb CARS system with an all-fiber architecture, which integrates ytterbium-doped fiber and photonic crystal fiber technologies at its core. With 10 averages, this system recorded the Raman spectra of acetonitrile and ethyl acetate over 100–1300 cm−1 at a resolution of 8 cm−1 and with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of approximately 100. To meet the requirements of the CARS microscope, Li et al. [45] developed a dual-color fiber laser capable of achieving passive synchronized output at wavelengths of 1.03 μm and 1.53 μm. Qin et al. [59] implemented a fully fiber-based free-running bidirectional dual-comb CARS system incorporating spectral focusing (SF) technology using chirped pulses instead of ultrashort pulses. These advancements significantly enhanced the performance of fiber-based dual-comb CARS systems.

4.3. Performance Improvements in Dual-Comb CARS Systems

4.3.1. Enhanced Spectral Refresh Rate

FT dual-comb CARS systems reduce acquisition time by more than 1000 times compared to conventional methods. However, practical refresh rates remained limited to tens or hundreds of milliseconds, constraining continuous spectral acquisition and imaging. Chen et al. [60] reported an imaging system based on two linearly chirped 100 MHz comb waves, which can achieve ultra-high-speed broadband CARS imaging, completing a 700 ns measurement time and 1.2 kHz refresh rate. Spectral focusing excitation eliminates the dilemma of choosing between signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and imaging speed, but the system’s low duty cycle hindered applications. Zhang et al. [61] utilized a dual comb with significantly different repetition rates (10 GHz Ti:Sa oscillator vs. 100 MHz ± 20 Hz oscillator) to achieve a two-order-of-magnitude refresh rate improvement. Lv et al. [62] proposed a hybrid dual-comb CARS system seeded from a broadband fiber laser and a frequency-modulated electro-optic comb. In this work, CARS spectra (2800–3200 cm−1) with a resolution (30 cm−1) at a maximum refresh rate of 1 MHz can be achieved.

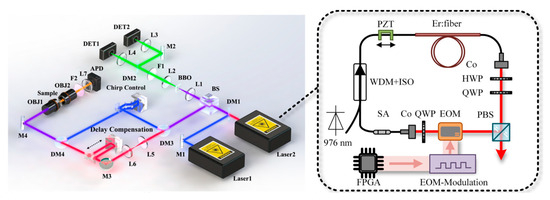

4.3.2. Increased Duty Cycle

Conventional dual-comb CARS exhibits low efficiency (<1% duty cycle) due to mismatch between laser pulse intervals and molecular vibrational coherence lifetimes, resulting in more than 99% wasted laser energy, reduced spectral acquisition rates, and low SNR. Increasing repetition rate by shortening cavity length is a direct approach, but Kathrin’s 1 GHz system [63] sacrificed pulse energy, limiting nonlinear interactions. Fourier-transform CARS (FT-CARS) using mechanical scanners for rapid group delay scanning faced speed limitations due to scanner inertia. By utilizing a quasi-dual-comb light source, Kameyama et al. [64] developed a dual-comb coherent Raman spectroscopy technique, as shown in Figure 9, with a duty cycle of approximately 100%, achieving a record-high 100,000 spectra per second acquisition rate and 100 times sensitivity improvement. A dual-comb fiber laser system with fast repetition rate tunability was realized by Wu et al. [65], improving duty cycle by hundreds of times through asymmetric sum-frequency mixing and precise repetition rate difference reversal.

Figure 9.

The experimental setup for a near 100% duty cycle dual-comb CARS. Reproduced with permission [64]. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

Beyond refresh rate and duty cycle, researchers have enhanced spectral bandwidth, resolution, and sensitivity. Yan et al. [66] generated broadband high-resolution Raman spectroscopy data covering a wavenumber range from 200 to 1400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 using two broadband frequency combs with ~140 μs measurement time, leveraging short-wavelength edges for enhanced heterodyne detection. Yan and his collaborators [67] developed a nonlinear DCS device based on an ultrathin (10 nanometers) nanoporous gold film. This device significantly enhances the sensitivity of coherent Raman spectroscopy (CRS) through plasma enhancement effects, achieving sensitivity enhancement of 106–108. Table 1 summarizes typical dual-comb CARS characteristics and functionality.

Table 1.

Dual-comb CARS characteristics and functionality.

5. Biomedical Applications of CARS

Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) is a nonlinear vibrational spectroscopic technique based on a third-order nonlinear optical process. It enables label-free, chemically specific imaging by probing the intrinsic vibrational signatures of molecular bonds, which correspond to Raman-active modes. Distinguished by high sensitivity and excellent spatial resolution, CARS microscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for non-invasive investigation in biomedicine. Its applications span diverse areas including single-cell analysis, tissue imaging, tumor diagnosis, in vivo metabolic tracking, lipid dynamics observation, myelin imaging in neuroscience, and real-time monitoring of drug delivery. This section reviews the traditional CARS for biomedical applications.

5.1. Detection of Cellular Components

As the fundamental structural and functional unit of organisms, cells are frequently imaged using CARS microscopy to observe cellular structures, distinguish intracellular components, and analyze metabolic processes. Although CARS signals are detectable from amino acids and nucleic acids, lipids are primarily studied in biomedical research due to stronger C-H bond vibrations. Lipids play crucial physiological roles, such as forming lipid bilayers in cellular membranes essential for signaling and regulation, and serving as energy storage media. Lipid abnormalities are associated with obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancers. Nan et al. [68] validated CARS imaging accuracy by comparing Oil Red O-stained neutral lipid droplets in live fibroblasts with unstained counterparts. CARS microscopy also enabled monitoring of 3T3-L1 cell differentiation, revealing that Oil Red O staining altered lipid droplet morphology, whereas CARS provided dynamic, nonperturbative observation. Okuno et al. [69] systematically investigated the uptake and degradation of surfactants in mammalian cells using CARS microscopy. In general, although CARS signals are detectable from amino acids and nucleic acids, lipids are primarily studied in biomedical research due to stronger C-H bond vibrations.

5.2. High-Resolution Imaging of Tumor and Cancer Cells

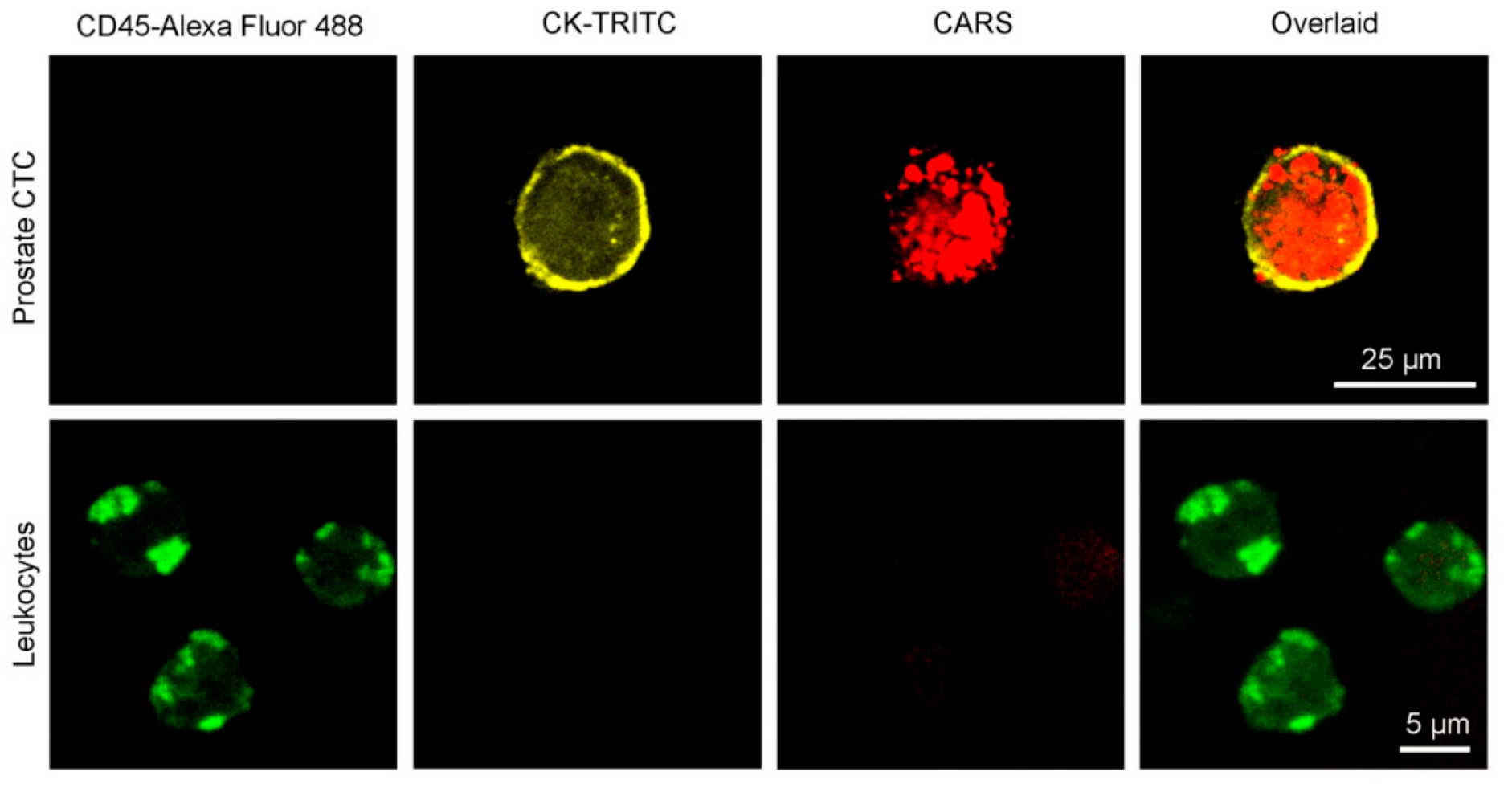

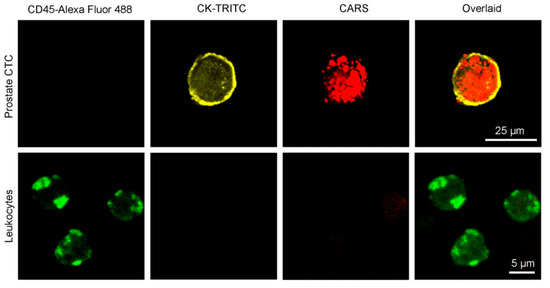

Tumor malignancy is often linked to cancer cell proliferation and metastasis, making early diagnosis critical. CARS microscopy supports tumor diagnosis by quantitatively detecting saturated and unsaturated lipid contents spectroscopically. Elevated unsaturated lipids are known to promote tumor cell growth [70,71]. Mitra et al. [72] used CARS to conduct in vitro and in vivo transplantation experiments, which demonstrate high-fat diets enhance lipid accumulation and migration in lung cancer cells (shown in Figure 10). Francisco [71] reviewed CARS as a non-linear optical imaging technique for cancer detection, which provides the ability to suppress non-resonant fluorescence background signals and is suitable for applications in the detection of tumor cells (CTCs). Among them, CARS technology quantitatively discriminates cancer cells from adjacent normal cells based on their unique spectral fingerprints, such as variations in tissue lipid composition.

Figure 10.

High-fat diets enhance lipid accumulation and migration in lung cancer detected by CARS microscope. Reproduced with permission [72]. Copyright 2012 Mitra et al., licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

5.3. Tissue Imaging and Other Applications

CARS imaging is now recognized as a valuable means of examining myelination in the central and peripheral nervous systems, providing insights into spinal cord injuries and demyelinating diseases. Wang et al. [73] employed laser-scanning CARS microscopy for 3D imaging of myelin sheaths, analyzing molecular orientation and vibrational spectra. 3D hyperspectral broadband CARS tissue imaging [74] covering 500–3500 cm−1 enabling rapid chemical imaging of mouse tissues in both C-H stretching and fingerprint regions. Vernuccio et al. [75] used deep-learning models on experimental CARS spectra and images obtained with a homemade BCARS microscope operating in different configurations.

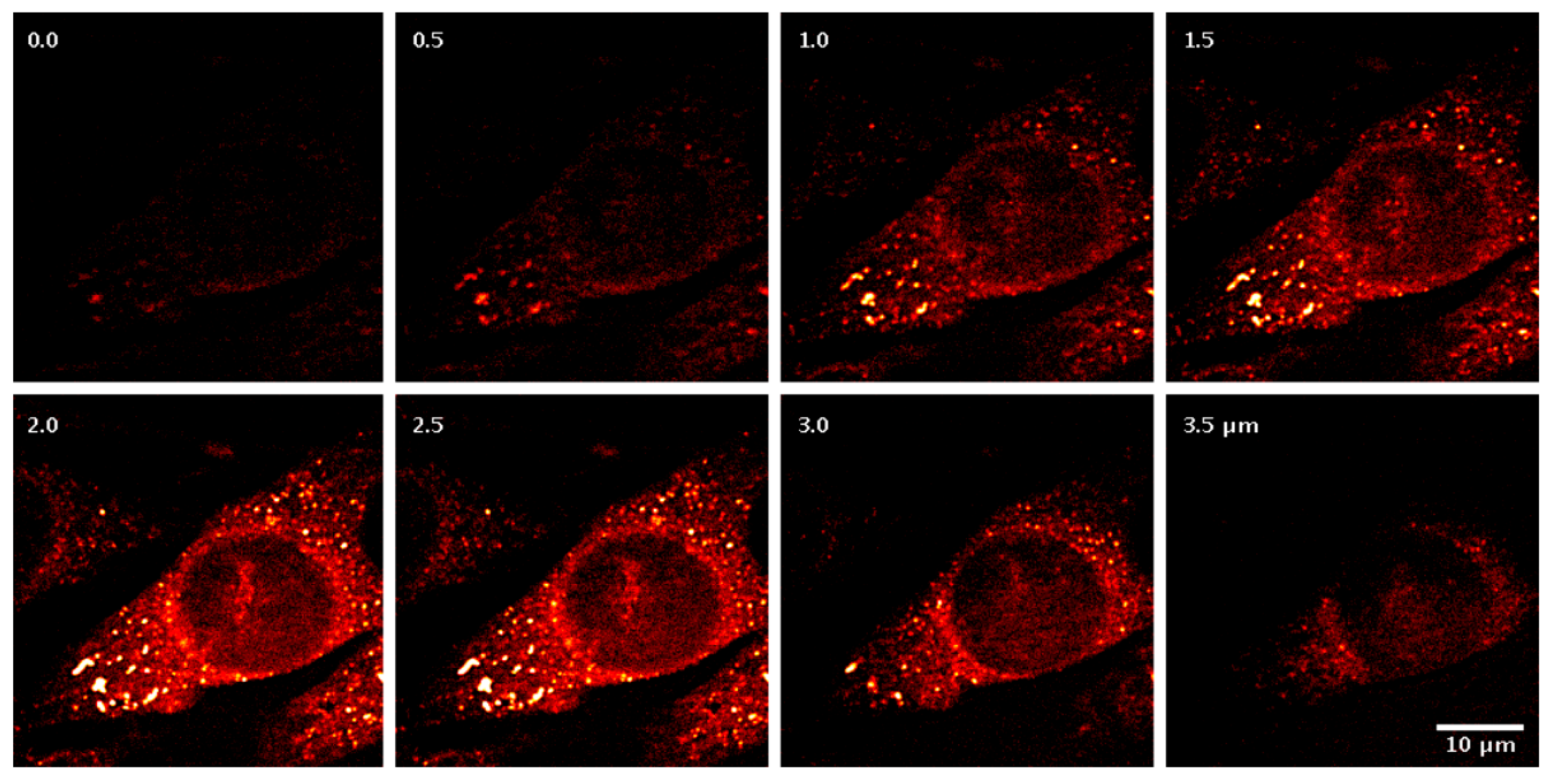

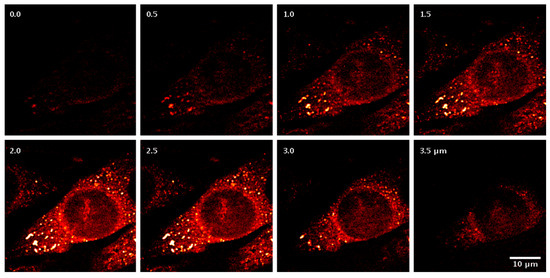

Beyond these applications, CARS microscopy has been utilized for studying cell differentiation, host–pathogen interactions, and drug effects. The Konorov research team [76] has completed in situ analysis experiments on embryonic stem cells in vivo, revealing spectral differences between differentiated and undifferentiated cells without labeling. Robinson et al. [77] combined two-photon fluorescence and CARS microscopy to visualization cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts, showing nuclear expansion and perinuclear lipid droplet accumulation during infection. Liu et al. [78] utilized artificial intelligence for coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy, which can be applied to distinguish different cervical tissues with the naked eye alone, as shown in Figure 11. Kameyama et al. [64] demonstrated a high CARS spectral acquisition rate of 100,000 spectra/s with near 100% duty cycle dual-comb CARS for toluene detection, offering significant potential for a variety of applications in both biomedical and materials research. In the future, CARS technology will play an increasingly important role in areas such as life sciences and biomedical research [79,80,81].

Figure 11.

The CARS images of a fibroblast cell with increasing depth [77]. Reproduced with permission [77]. Copyright 2010 WILE-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Welnhelm.

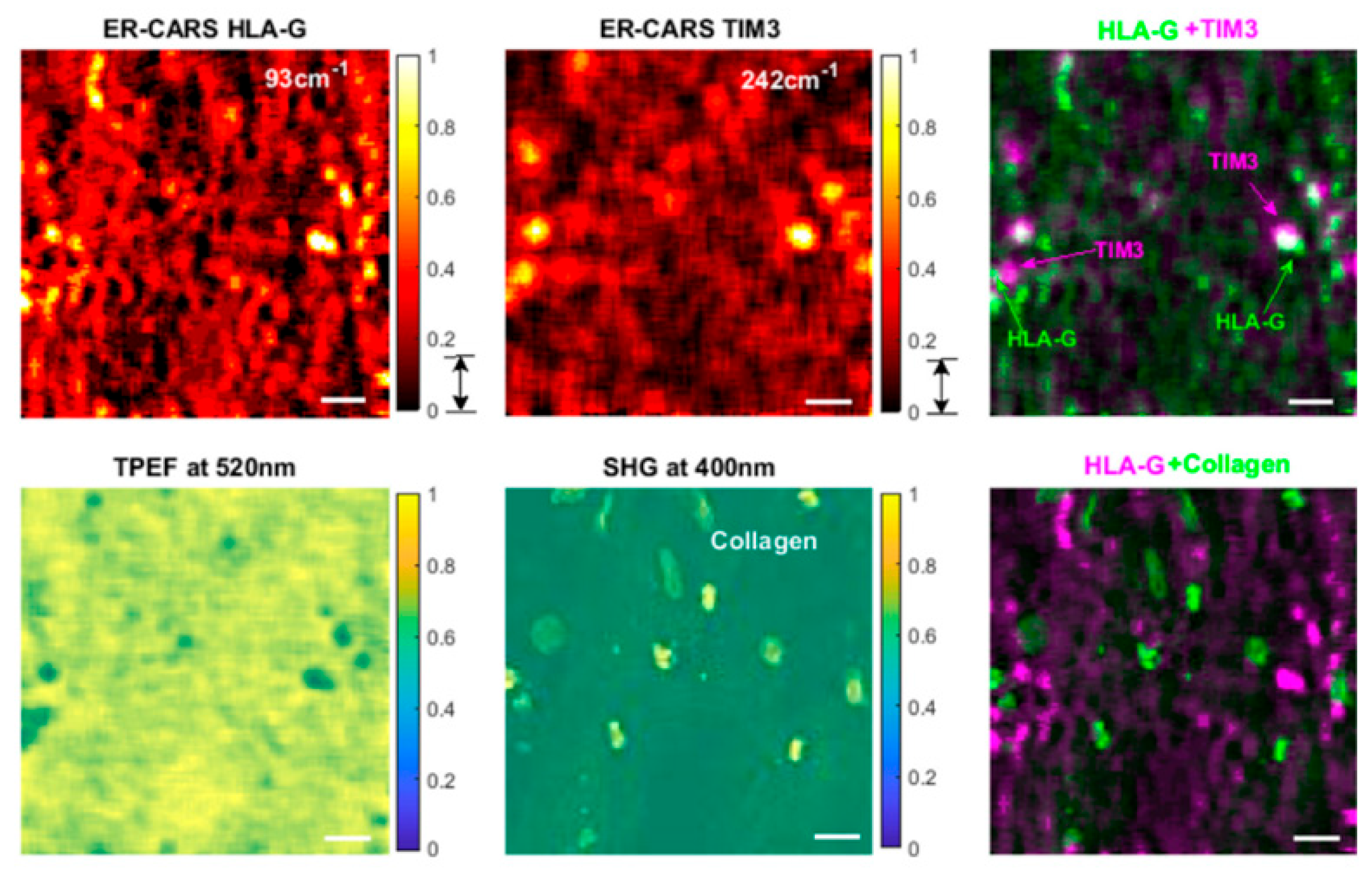

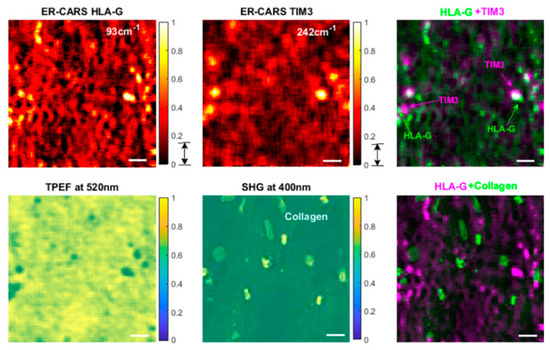

More recently, Fantuzzi et al. [82] developed a robust wide-field nonlinear microscope that integrates coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) and sum-frequency generation (SFG) contrasts with random illumination microscopy (RIM). They demonstrate the potential of CARS-RIM and SFG-RIM for label-free, high-contrast chemical imaging in both two and three dimensions, using diverse samples including polymer beads, unstained human breast tissue, and mixtures of chemical compounds. Qi et al. [83] realized highly sensitive and selective electronic-resonance coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (ER-CARS) spectroscopy and microscopy, employing lock-in detection. They further showcased its chemical selectivity by imaging tissue specimens stained with two infrared dyes. These advances facilitate ultrasensitive Raman imaging and present a promising strategy for achieving highly multiplexed, selective visualization in biological research, as shown in Figure 12. Li et al. [84] introduce a higher-order coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (HO-CARS) microscopy technique that overcomes the diffraction barrier to enable label-free, super-resolution vibrational imaging. The enhanced resolution is validated through analysis and demonstration in biological samples, exemplified by live HeLa and buccal cells. These findings establish HO-CARS microscopy as a promising approach for achieving high-contrast, label-free super-resolution imaging in diverse biological and biomedical contexts. Anna et al. [85] present a super-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy technique that employs phase-resolved image scanning to achieve up to a twofold improvement in spatial resolution compared to conventional CARS. Distinguished from other super-resolution schemes in nonlinear microscopy, this approach is simple, operates under low excitation intensities, and is directly compatible with standard forward-detected CARS configurations. Burde et al. [86] achieve a marked increase in the sensitivity of CARS microscopy, pushing detection capabilities to low micromolar concentrations through the deliberate use of excitation wavelengths near electronic resonances. This advance not only deepens the mechanistic understanding of electronic preresonance effects in CARS but also translates into a practical methodology for sensitivity enhancement, which unlocks new possibilities for coherent Raman imaging at physiologically and analytically relevant low concentrations.

Figure 12.

The ER-CARS images of dye-stained tissues [83]. Reproduced with permission [83]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society.

6. Summary and Outlook

The dual-comb coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) technique holds significant value in the fields of medicine, biology, and chemistry due to its high sensitivity, high spatial resolution, and non-invasive, non-destructive detection capabilities. However, as a relatively nascent technology, several challenges remain in the generation of dual-comb sources, including limited flexibility in repetition rate tuning, low resolution, and suboptimal coordination among system components. These limitations hinder its adaptability to practical applications, particularly in clinical diagnostics. The challenges facing future dual-comb CARS mainly include how to maintain the stability of the dual-comb spectrum and their mutual coherence, which is a tremendous challenge. This requires miniaturization and fiber integration of the dual-comb light source while ensuring long-term operational reliability and resistance to mechanical and thermal fluctuations. In addition, achieving video-rate imaging for bioimaging applications also demands unprecedented speeds in data acquisition and processing, among other things. A key future research direction involves achieving flexible and precise control of repetition rates to enhance system versatility. Furthermore, given the critical role of cellular structures, functions, and dynamics in human physiology, the study of these aspects is of paramount importance. Previous research indicates that dual-comb CARS exhibits strong potential for real-time and dynamic detection in biochemical applications, especially in live-cell imaging and in vivo clinical studies. Thus, expanding its capabilities for in vivo imaging represents another promising research avenue. In summary, advancements in dual-comb CARS spectroscopy are expected to substantially accelerate progress in biomedical imaging, enabling new opportunities for non-invasive diagnostics and fundamental biological exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L., J.W., and X.L.; methodology, B.L. and J.W.; software, X.H.; validation, B.L., J.W., X.L., X.H., and H.G.; formal analysis, B.L., J.W., X.L., X.H., and H.G.; investigation, H.G.; resources, X.L.; data curation, B.L. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L., J.W., X.L., X.H., and H.G.; writing—review and editing, B.L. and H.G.; visualization, B.L. and H.G.; supervision, B.L. and H.G.; project administration, B.L. and H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Taiyuan’s Key Technology Breakthroughs, High-Precision Die Bonding Technology and Equipment for Advanced Packaging of Integrated Circuits, grant number 2025TYJB02.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- DeMello, A.J. Control and detection of chemical reactions in microfluidic systems. Nature 2006, 442, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Ideguchi, T.; Yonamine, Y.; Lee, S.; Luo, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Ito, T.; Hase, M.; Park, J.; Kasai, Y.; et al. High-throughput label-free molecular fingerprinting flow cytometry. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau0241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, D.; Pilger, C.; Hachmeister, H.; Oberländer, E.; Wördenweber, R.; Wichmann, J.; Mussgnug, J.H.; Huser, T.; Kruse, O. Label-free in vivo analysis of intracellular lipid droplets in the oleaginous microalga Monoraphidium neglectum by coherent Raman scattering microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, M. Fluorescence microscopy-a historical and technical perspective. Cytom. Part A 2013, 83, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DʼEste, E.; Lukinavičius, G.; Lincoln, R.; Opazo, F.; Fornasiero, E.F. Advancing cell biology with nanoscale fluorescence imaging: Essential practical considerations. Trends Cell Biol. 2024, 34, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoq, J.; Orlova, N.; Grewe, B.F. Wide. Fast. Deep: Recent advances in multiphoton microscopy of in vivo neuronal activity. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9042–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, E.; Latka, I.; Matthäus, C.; Schie, I.; Popp, J. In-vivo Raman spectroscopy: From basics to applications. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 071210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mondol, A.S.; Stiebing, C.; Marcu, L.; Popp, J.; Schie, I.W. Raman ChemLighter: Fiber optic Raman probe imaging in combination with augmented chemical reality. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Knorr, F.; Popp, J.; Schie, I.W. Development and evaluation of a hand-held fiber-optic Raman probe with an integrated autofocus unit. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 30760–30770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; Short, M.; Zeng, H. Real-time in vivo cancer diagnosis using Raman spectroscopy. J. Biophotonics 2015, 8, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, C.; Xu, M.; Xu, L.-J.; Wei, T.; Ma, X.; Zheng, X.-S.; Hu, R.; Ren, B. Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy for bioanalysis: Reliability and challenges. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4946–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Gord, J.R.; Patnaik, A.K. Recent advances in coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering spectroscopy: Fundamental developments and applications in reacting flows. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudiger, C.W.; Min, W.; Saar, B.G.; Lu, S.; Holtom, G.R.; He, C.; Tsai, J.C.; Kang, J.X.; Xie, X.S. Label-free biomedical imaging with high sensitivity by stimulated raman scattering microscopy. Science 2008, 322, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolenko, A.; Strelchuk, V.; Tsykaniuk, B.; Kysylychyn, D.; Capuzzo, G.; Bonanni, A. Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Mn-Mgk Cation Complexes in GaN. Crystals 2019, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, F.; Kircher, M.F.; Stone, N.; Matousek, P. Spatially offset Raman spectroscopy for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänsch, T.W. Nobel lecture: Passion for precision. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2006, 78, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Tian, H.; Liu, W.; Li, R.; Song, Y.; Hu, M. Dual-comb generation from a single laser source: Principles and spectroscopic applications towards mid-IR-A review. J. Phys. Photonics 2020, 2, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picqué, N.; Hnsch, T.W. Frequency comb spectroscopy. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coddington, I.; Newbury, N.; Swann, W. Dual-comb spectroscopy. Optica 2016, 3, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, X. Multi-dimensional multiplexed, tri-comb and quad-comb generation from a bidirectional mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 27787–27796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Yao, Z.; Li, T.; Li, Q.; Xie, S.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z. Dual-comb spectroscopy of methane based on a free-running Erbium-doped fiber laser. Adv. Photonics 2019, 27, 11406–11412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nitta, K.; Zhao, X.; Mizuno, T.; Minamikawa, T.; Hindle, F.; Zheng, Z.; Yasui, T. Adaptive-sampling near-Doppler-limited terahertz dual-comb spectroscopy with a free-running single-cavity fiber laser. Adv. Photon. 2020, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, R.; Ren, H.; Yan, J.; Han, X.; Chen, J. Variable wavelength-multiplexed dual-comb generation and spectroscopic measurement by a free-running all-normal-dispersion Yb-doped fiber laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 111101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, T.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z. Generation and observation of ultrafast spectro-temporal dynamics of different pulsating solitons from a fiber laser. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 14127–14133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomsadze, B.; Cundiff, S.T. Frequency combs enable rapid and high-resolution multidimensional coherent spectroscopy. Science 2017, 357, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, J.; Xue, P.; Wang, X.; Xiang, W. Real-time transition dynamics of harmonic mode-locking states with spectral filtering effect in a hybrid mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Comm. 2023, 545, 129477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Ideguchi, T.; Holzner, S.; Bernhardt, B.; Guelachvili, G.; Hänsch, T.W.; Picqué, N. Coherent Raman Spectroscopy with Femtosecond Laser Frequency Combs. In Proceedings of the Laser Applications to Chemical, Security and Environmental Analysis, San Francisco, CA, USA, 1–5 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ideguchi, T.; Holzner, S.; Bernhardt, B.; Guelachvili, G.; Picqué, N.; Hänsch, T.W. Coherent Raman spectro-imaging with laser frequency combs. Nature 2013, 502, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maker, P.D.; Terhune, R.W. Study of optical effects due to an induced polarization third order in the electric field strength. Phys. Rev. 1965, 137, A801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloembergen, N. The stimulated Raman effect. Am. J. Phys. 1967, 35, 989–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, G.I.; Arora, R.; Yakovlev, V.V. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging of microcalcifications associated with breast cancer. Analyst 2021, 146, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, J.X. Coherent Raman scattering microscopy in biology and medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 17, 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiang, W.; Ren, H.; Yan, J. Transient multi-soliton dynamics between adjacent-order harmonic mode-locking states in a hybrid mode-locked fiber laser. Results Phys. 2023, 51, 106712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, A.; Hudert, F.; Janke, C.; Dekorsy, T.; Köhler, K. Femtosecond time-resolved optical pump-probe spectroscopy at kilohertz-scan-rates over nanosecond-time-delays without mechanical delay line. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 30110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebs, R.; Klatt, G.; Janke, C.; Dekorsy, T.; Bartels, A. High-speed asynchronous optical sampling with sub-50fs time resolution. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 5974–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buholz, N.; Chodorow, M. Acoustic wave amplitude modulation of a multimore ring laser. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1967, 3, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.; Hata, Y.; Minoshima, K. High-coherence ultra-broadband bidirectional dual-comb fiber laser. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 5931–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xing, J.; Kwon, D.; Xie, Y.; Prakash, N.; Kim, J.; Huang, S.W. Bidirectional mode-locked all-normal dispersion fiber laser. Optica 2020, 7, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Qu, F.; Ou, P.; Sun, H.; He, S.; Fu, B. Recent Advances and Outlook in Single-Cavity Dual Comb Lasers. Photonics 2023, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgören, K.; Ilday, F.Ö. All-fiber all-normal dispersion laser with a fiber-based Lyot filter. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 1296–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, G.; Zhao, B.; Li, C.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yasui, T.; Zheng, Z. Picometer-resolution dual-comb spectroscopy with a free-running fiber laser. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 21833–21845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, H.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Song, Y.; Hu, M. All-polarization-maintaining dual-wavelength mode-locked fiber laser based on Sagnac loop filter. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 28302–28311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellinger, J.; Mayer, A.S.; Winkler, G.; Grosinger, W.; Truong, G.-W.; Droste, S.; Li, C.; Heyl, C.M.; Hartl, I.; Heckl, O.H. Tunable dual-comb from an all-polarization-maintaining single-cavity dual-color Yb: Fiber laser. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 28062–28074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yang, C. Nonlinear multimode interference-based dual-color mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 1655–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, K.; Cao, B.; Xiao, X.; Yang, C. Carbon nanotube-synchronized dual-color fiber laser for coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 3329–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Sun, H.; Lv, H.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Hu, P.; Fu, H.; Yang, H.; Tan, J. A multidimensional multiplexing mode-locked laser based on a dual-ring integrative structure for tri-comb generation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Z. Polarization-multiplexed, dual-comb all-fiber mode-locked laser. Photonics Res. 2018, 6, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterczewski, Ł.A.; Przewłoka, A.; Kaszub, W.; Sotor, J. Computational Doppler-limited dual-comb spectroscopy with a free-running all-fiber laser. APL Photonics 2019, 4, 116102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selm, R.; Winterhalder, M.; Zumbusch, A.; Krauss, G.; Hanke, T.; Sell, A.; Leitenstorfer, A. Ultrabroadband background-free coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy based on a compact Er: Fiber laser system. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 3282–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Joffre, M.; Skodack, J.; Ogilvie, J.P. Interferometric Fourier transform coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Opt. Express 2006, 14, 8448–8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamitsu, M.; Sakaki, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Podagatlapalli, G.K.; Ideguchi, T.; Goda, K. Ultrafast broadband Fourier-transform CARS spectroscopy at 50,000 spectra/s enabled by a scanning Fourier-domain delay line. Vib. Spectrosc. 2017, 91, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Takahashi, M.; Ideguchi, T.; Goda, K. Broadband coherent Raman spectroscopy running at 24,000 spectra per second. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohler, K.J.; Bohn, B.J.; Yan, M.; Mélen, G.; Hänsch, T.W.; Picqué, N. Dual-comb coherent Raman spectroscopy with lasers of 1-GHz pulse repetition frequency. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.L.; Potma, E.O.; Puoris’hag, M.; Côté, D.; Lin, C.P.; Xie, X.S. Chemical imaging of tissue in vivo with video-rate coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16807–16812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Wu, T.; Chen, K.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Wei, H. Delay-Spectral Focusing Dual-Comb Coherent Raman Spectroscopy for Rapid Detection in the High-Wavenumber Region. ACS Photon. 2022, 9, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.L.; Yan, M.; Hänsch, T.W.; Picqué, N. Ultra-broadband Dual-Comb Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the Fourier Transform Spectroscopy Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 10–15 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shchekin, A.; Koptyaev, S.; Ryabko, M.; Medvedev, A.; Lantsov, A.; Lee, H.S.; Roh, Y.G. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering under frequency comb excitation. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluccelli, N.; Howle, C.R.; McEwan, K.; Wang, Y.; Fernandez, T.T.; Gambetta, A.; Laporta, P.; Galzerano, G. Fiber-format dual-comb coherent Raman spectrometer. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 4683–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Cromey, B.; Batjargal, O.; Kieu, K. All-fiber single-cavity dual-comb for coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering spectroscopy based on spectral focusing. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wu, T.; Chen, T.; Wei, H.; Yang, H.; Zhou, T.; Li, Y. Spectral focusing dual-comb coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopic imaging. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 3634–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Shum, P.P.; Chen, J.; Wei, H. Rapid coherent Raman hyperspectral imaging based on delay-spectral focusing dual-comb method and deep learning algorithm. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Han, B.; Yang, M.; Wen, Z.; Huang, K.; Yang, K.W.; Zeng, H. Ultrahigh-Speed Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy with a Hybrid Dual-Comb Source. ACS Photon. 2023, 10, 2964–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.R.; Hickstein, D.D.; Papp, S.B. Broadband, electro-optic, dual-comb spectrometer for linear and nonlinear measurements. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 29148–29154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameyama, R.; Takizawa, S.; Hiramatsu, K.; Goda, K. Dual-comb coherent Raman spectroscopy with near 100% duty cycle. ACS Photonics 2020, 8, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Chen, K.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. Repetition frequency modulated fiber laser for coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Holzner, S.; Hänsch, T.W.; Picqué, N. Broadband Dual-Comb Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy at High Signal-to-Noise Ratio. In Proceedings of the CLEO: Applications and Technology, San Jose, CA, USA, 10–15 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Zhang, L.; Hao, Q.; Shen, X.; Qian, X.; Chen, H.; Ren, X.; Zeng, H. Surface-Enhanced Dual-Comb Coherent Raman Spectroscopy with Nanoporous Gold Films. Laser Photonics Rev. 2018, 12, 1800096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Cheng, J.X.; Xie, X.S. Vibrational imaging of lipid droplets in live fibroblast cells with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. J. Lipid Res. 2003, 44, 2202–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, M.; Kano, H.; Fujii, K.; Bito, K.; Naito, S.; Leproux, P.; Couderc, V.; Hamaguchi, H.-O. Surfactant uptake dynamics in mammalian cells elucidated with quantitative coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microspectroscopy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.M.; Ackerman, D.; Quinn, Z.L.; Mancuso, A.; Gruber, M.; Liu, L.; Giannoukos, D.N.; Bobrovnikova-Marjon, E.; Diehl, J.A.; Keith, B.; et al. Dysregulated mTORC1 renders cells critically dependent on desaturated lipids for survival under tumor-like stress. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, J.A. A Review of Non-Linear Optical Imaging Techniques for Cancer Detection. Optics 2024, 5, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Chao, O.; Urasaki, Y.; Goodman, O.B.; Le, T.T. Detection of lipid-rich prostate circulating tumour cells with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fu, Y.; Zickmund, P.; Shi, R.; Cheng, J.X. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging of axonal myelin in live spinal tissues. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, C.H., Jr.; Lee, Y.J.; Heddleston, J.M.; Hartshorn, C.M.; Walker, A.R.H.; Rich, J.N.; Lathia, J.D.; Cicerone, M.T. High-speed coherent Raman fingerprint imaging of biological tissues. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernuccio, F.; Broggio, E.; Sorrentino, S.; Bresci, A.; Junjuri, R.; Ventura, M.; Vanna, R.; Bocklitz, T.; Bregonzio, M.; Cerullo, G.; et al. Non-resonant background removal in broadband CARS microscopy using deep-learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konorov, S.O.; Glover, C.H.; Piret, J.M.; Bryan, J.; Schulze, H.G.; Blades, M.W.; Turner, R.F. In situ analysis of living embryonic stem cells by coherent anti-Stokes Raman microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 7221–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.; Ochsenkühn, M.A.; Campbell, C.J.; Giraud, G.; Hossack, W.J.; Arlt, J.; Crain, J. Intracellular imaging of host-pathogen interactions using combined CARS and two-photon fluorescence microscopies. J. Biophotonics 2010, 3, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiu, C.; Zou, Y.; Wu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wan, L.; Xu, S.; Han, B.; Zhang, H. Cervical cancer diagnosis model using spontaneous Raman and Coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy with artificial intelligence. Spectrochim. Acta A 2025, 327, 125353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, K.; Korona, W.; Nowakowska, A.; Borek-Dorosz, A.; Pieczara, A.; Orzechowska, B.; Wislocka-Orlowska, A.; Schmitt, M.; Popp, J.; Baranska, M. Coherent Raman spectroscopy: Quo vadis? Vib. Spectrosc. 2024, 132, 103684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C.; Schie, I.W.; Meyer, T.; Schmitt, M.; Popp, J. Developments in spontaneous and coherent Raman scattering microscopic imaging for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 7, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, P.; Ogunnaike, E.A.; Ahn, S.; Froehlich, K.A.; Jansson, A.; Ligler, F.S.; Dotti, G.; Brudno, Y. Bioinstructive implantable scaffolds for rapid in vivo manufacture and release of CAR-T cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzi, E.M.; Heuke, S.; Labouesse, S.; Gudavičius, D.; Bartels, R.; Sentenac, A.; Rigneault, H. Wide-field coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy using random illuminations. Nat. Photonics 2023, 17, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Pinkas, I.; Rigneault, H.; Oron, D.; Ren, L. Electronic-Resonance Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Spectroscopy and Microscopy. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Z. Higher-order coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy realizes label-free super-resolution vibrational imaging. Nat. Photonics 2019, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhitnitsky, A.; Benjamin, E.; Bitton, O.; Oron, D. Super-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy by coherent image scanning. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burde, R.; Reuter, N.; Pruccoli, A.; Birech, Z.; Winterhalder, M.; Zumbusch, A. Electronically Preresonant Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2025, 9, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.